Summary

Stressful life events are a major contributor to the development of major depressive disorder. Environmental perturbations like stress change gene expression in the brain, leading to altered behavior. Gene expression is ultimately regulated by chromatin structure and the epigenetic modifications of DNA and the histone proteins that make up chromatin. Studies over the past two decades have demonstrated that stress alters the epigenetic landscape in several brain regions relevant for depressive-like behavior in rodents. This chapter will discuss epigenetic mechanisms of brain histone acetylation, histone methylation, and DNA methylation that contribute to adult stress-induced depressive-like behavior in rodents. Several biological themes have emerged from the examination of the brain transcriptome after stress such as alterations in the neuroimmune response, neurotrophic factors, and synaptic structure. The epigenetic mechanisms regulating these processes will be highlighted. Finally, pharmacological and genetic manipulations of epigenetic enzymes in rodent models of depression will be discussed as these approaches have demonstrated the ability to reverse stress-induced depressive-like behaviors and provide proof-of-concept as novel avenues for the treatment of clinical depression.

Keywords: Stress, depression, epigenetic, histone acetylation, histone methylation, DNA methylation, HDAC, sirtuin, DNMT, TET

1. Introduction

Depression, or major depressive disorder (MDD), is a psychiatric condition in which individuals suffer from sadness, hopelessness, and loss of interest in activities. MDD is an extremely debilitating disorder that results in an inability to engage in everyday life. Over 300 million individuals suffer from depression, and it is the leading cause of disability worldwide (WHO, 2017). The etiology of MDD is multifactorial, with genetic and environmental factors playing an important role in its development and progression (Geschwind & Flint, 2015; Pemberton & Fuller Tyszkiewicz, 2016). Twin studies estimate that the heritability of MDD is approximately 40% (Geschwind & Flint, 2015). Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified genes associated with MDD (Howard et al., 2019; Ormel et al., 2019; Wray et al., 2018). A meta-analysis of three independent GWAS studies, comprising 807,553 individuals, identified 102 variants associated with depression (Howard et al., 2019).

However, given that approximately 40% of the risk for MDD is genetic, the other 60% of liability is due to environmental factors. Environmental factors that can increase the risk of developing MDD include stressful life events such as death of a loved one, workplace stressors, financial problems, domestic violence and certain serious medical conditions like cancer (Park et al., 2019; Pemberton & Fuller Tyszkiewicz, 2016). Acute severely traumatic events and chronic stress can have profound and long-lasting effects on gene expression in the brain, leading to changes in behavior (Scarpa et al., 2020). Epigenetic processes are responsible for regulating gene expression and provide a bridge between the environment and the genome. Gene expression is tightly controlled by the accessibility of DNA to transcription factors, which is regulated by chemical modifications on DNA itself and chromatin structure (Luger et al., 2012). The fundamental unit of chromatin is the nucleosome. Each nucleosome is composed of a histone protein octamer core (formed by two each of the histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) that is wrapped with ∼146 bp of DNA (Luger et al., 2012). Histone proteins are modified post-translationally by several different chemical moieties through the action of specific enzymes, colloquially known as “writers”. Histone modifications include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, crotonylation, citrullination, ADP-ribosylation, serotonylation, and dopaminylation (Allis & Jenuwein, 2016; Farrelly & Maze, 2019; Lepack et al., 2020). In addition to histone modifications, DNA is altered by the addition of methyl groups on cytosine nucleotides by DNA methyltransferases (Lyko, 2018). Posttranslational modifications on histone proteins and DNA methylation, once thought to be stable modifications, are actually labile in response to environmental perturbations (Allis & Jenuwein, 2016). Removal of these modifications is performed by another group of enzymes, known as “erasers”.

In this chapter, we will discuss the role of histone acetylation, histone methylation, and DNA methylation in stress-induced depressive-like behaviors in rodents, including the use of genetic or pharmacological manipulation of epigenetic processes to alter behavior, summarized in Table 1. The focus will be on adult stress-induced epigenetic alterations, although there are many studies on the epigenetics of early life stress. For a review of this topic, please refer to Torres-Berrio and colleagues (Torres-Berrio et al., 2019).

Table 1:

Effects of pharmacological and genetic manipulations of epigenetic enzymes on depressive-like behaviors in animals

| Manipulation | Species | Route | Behavioral effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hdac5 knockout | Mouse | Global knockout | Decreased social interaction and sucrose preference | (Renthal et al., 2007) |

| SAHA (HDAC inhibitor) | Mouse | Intracranial (NAc) | Increased social interaction and sucrose preference, decreased immobility (FST) | (Covington et al., 2009) |

| SAHA | Mouse | Intraperitoneal (I.P.) | Increased social interaction and sucrose preference, decreased latency to feed (NIH) and immobility (FST) | (Uchida et al., 2011) |

| SAHA | Mouse | I.P. | Decreased immobility (FST) | (Meylan et al., 2016) |

| SAHA | Mouse | I.P. | Increased sucrose preference and grooming time, decreased latency to feed (NSF) and immobility (TST, FST) | (Kv et al., 2018) |

| SAHA | Rat | I.P. | Increased sucrose preference and grooming time | (Chen et al., 2019) |

| MS-275 (HDAC1/3 inhibitor) | Mouse | Intracranial (NAc) | Increased social interaction and sucrose preference, decreased immobility (FST) | (Covington et al., 2009; Dudek et al., 2020) |

| MS-275 | Mouse | Intracranial (hippocampus) | Increased sucrose preference | (Covington, Vialou, et al., 2011) |

| MS-275 | Mouse | Intracranial (amygdala) | Increased social interaction, decreased immobility (FST) | (Covington, Vialou, et al., 2011) |

| Hdac2 cDNA (dominant negative) | Mouse | Intracranial (NAc) | Increased social interaction, sucrose preference | (Uchida et al., 2011) |

| Hdac2 cDNA (active) | Mouse | Intracranial (NAc) | Decreased social interaction | (Uchida et al., 2011) |

| Sodium butyrate (HDAC inhibitor) | Mouse | I.P. | Increased sucrose preference decreased immobility (TST, FST) |

(Han et al., 2014; Yamawaki et al., 2018) |

| Hdac4 cDNA (active) | Rat | Intracranial (hippocampus) | Increased immobility time and reduced latency to immobility (FST) | (Sarkar et al., 2014) |

| Compound 60 (HDAC1/2 inhibitor) | Mouse | I.P. | Decreased immobility time (FST) | (Schroeder et al., 2013) |

| Sodium valproate (HDAC inhibitor) | Rat | intragastric gavage |

Decreased immobility time (FST) | (Liu et al., 2014) |

| Sirtinol (SIRT1/2 inhibitor) | Mouse | Intracranial (hippocampus) | Decreased social interaction, increased immobility (FST) and latency to feed (NSF) | (Abe-Higuchi et al., 2016) |

| EX-527, (SIRT1 inhibitor) |

Mouse | Intracranial (hippocampus) | Reduced social interaction time, increased latency to feed (NSF) |

(Abe-Higuchi et al., 2016) |

| RSV (SIRT activator) | Mouse | Intracranial (hippocampus) | Increased social interaction and sucrose preference | (Abe-Higuchi et al., 2016) |

| SIRT2104 (SIRT1 activator) | Mouse | Intracranial (hippocampus | Increased social interaction and sucrose preference | (Abe-Higuchi et al., 2016) |

| Sirt1 cDNA (active) | Mouse | Intracranial (hippocampus) | Increased social interaction and decreased immobility time (FST) and latency to feed (NSF) | (Abe-Higuchi et al., 2016) |

| Sirt1 cDNA (dominant negative) | Mouse | Intracranial (hippocampus) | Decreased social interaction, increased immobility (FST) and latency to feed (NSF) | (Abe-Higuchi et al., 2016) |

| 33i, (SIRT2 inhibitor) |

Mouse | I.P. | Increased social interaction and sucrose intake | (Erburu et al., 2017; Munoz-Cobo et al., 2017) |

| G9a knockout | Mouse | Intracranial (NAc) | Decreased social interaction and sucrose preference | (Covington, Maze, et al., 2011) |

| G9a cDNA (active) | Mouse | Intracranial (NAc) | Increased social interaction | (Covington, Maze, et al., 2011) |

| G9a or GLP knockout | Mouse | Forebrain neurons | Decreased sucrose preference | (Schaefer et al., 2009) |

| Dnmt3a cDNA (active) | Mouse | Intracranial (NAc) | Decreased social interaction, grooming time, and sucrose preference, and increased latency to eat (NSF) and immobility (FST) | (Hodes et al., 2015; LaPlant et al., 2010) |

| Dnmt3a cDNA (active) | Rat | Intracranial (NAc) | Decreased latency to immobility (FST) | (LaPlant et al., 2010) |

| Dnmt3a knockout | Mouse (female) | Intracranial (NAc) | Increased sucrose preference and grooming time, decreased latency to feed (NSF) and immobility (FST) | (Hodes et al., 2015) |

| RG108 (DMNT inhibitor) | Mouse | Intracranial (NAc) | Increased social interaction and sucrose preference | (LaPlant et al., 2010; Uchida et al., 2011) |

| Zebularine (DNMT inhibitor) | Mouse | Intracranial (Nac) | Increased social interaction and sucrose preference, decreased immobility (FST) and latency to feed (NSF) | (Uchida et al., 2011) |

| 5-azaD (DNMT inhibitor) | Rat | I.P. | Decreased immobility time (FST) | (Sales et al., 2011) |

| 5-azaC (DNMT inhibitor) | Rat | I.P. | Decreased immobility time (FST) | (Sales et al., 2011) |

| RG108 | Rat | Intracranial (hippocampus) | Decreased immobility time (FST) | (Sales et al., 2011) |

| 5-azaD | Rat | Intracranial (hippocampus) | Decreased immobility time (FST) | (Sales et al., 2011) |

| 5-azaD | Mouse | I.P. | Decreased immobility time (FST, TST) | (Sales et al., 2011; Sales & Joca, 2016) |

| RG108 | Mouse | I.P. | Decreased immobility time (FST) | (Sales & Joca, 2016) |

| Tet1 knockout | Mouse | Intracranial (NAc) | Increased social interaction and sucrose preference | (Feng et al., 2017) |

| Gadd45b miRNA | Mouse | Intracranial (NAc) | Increased social interaction | (Labonte et al., 2019) |

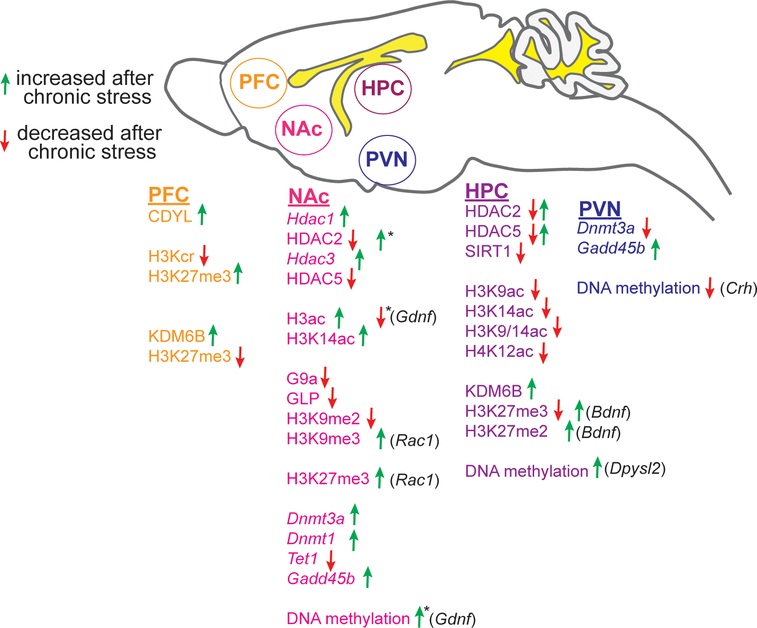

Neuroimaging studies in humans have demonstrated that psychological symptoms and behavioral deficits in patients with depression are closely related to structural and functional abnormalities in specific areas of the brain (Maletic et al., 2007) In particular, cortical and limbic regions involved in regulation of mood and stress response, such as amygdala, hippocampus and nucleus accumbens (NAc), and in learning and memory processes, such as the prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate, exhibit disrupted activity, connectivity, and structural changes in subjects diagnosed with MDD (Maletic et al., 2007). Epigenetic alterations in rodent models of stress-induced depression have been studied in the NAc, PFC, hippocampus, and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) (Figure 1), a key component of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis involved in the physiological response to stress. Findings from these four neuroanatomical regions will be discussed. Before delving into the details of epigenetic changes associated with depression, we will introduce the commonly used rodent models to examine stress-induced depressive-like behavior.

Figure 1. Changes in epigenetic enzymes, histone modifications, and DNA methylation in various brain regions of rats and mice after chronic stress.

A drawing of a sagittal view of the rodent brain showing the main brain regions that have been studied for epigenetic alterations after chronic stress protocols (i.e. chronic mild stress, social defeat stress) that result in depressive-like behavior in susceptible animals. Ventricles are shown as yellow areas. Proteins are in all capital letters and mRNA or gene names are italicized. Green and red arrows indicate an increase or decrease, respectively, in the associated epigenetic enzyme or modification after chronic stress. Two arrows in the opposite direction indicate that an increase and a decrease have been observed in studies employing different chronic stress protocols and/or different species. If changes have been observed at a specific gene, the gene name is indicated in parenthesis after the arrow. *Indicates modifications at the Gdnf gene in the same study (Uchida et al, 2011). Abbreviations: PFC, prefrontal cortex; NAc, nucleus accumbens; HPC, hippocampus, PVN, paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus; H3Kcr, histone H3 lysine crotonylation; H3K27me3, histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation; H3ac, histone H3 acetylation; H3K14ac, histone H3 lysine 14 acetylation; H3K9ac, histone H3 lysine 9 acetylation; H4K12ac, histone H4 lysine 12 acetylation; H3K27me2, histone H3 lysine 27 dimethylation.

2. Methods to Induce Depressive-Like Behavior in Rodents

Modeling psychiatric conditions in animals is a challenging task. Some symptoms of MDD, like guilt, suicidality and sadness, can only be examined in humans, while other symptoms like anhedonia (the inability to feel pleasure), apathy, decreased social behavior, cognitive deficits, and alterations in sleep and appetite, can be studied in animals (Czeh et al., 2016; Nestler & Hyman, 2010). The importance of modeling psychiatric conditions such as depression in animals is not just to gain a better understanding of the neurobiological aspects of the disease, but also to aid in screening promising new drugs with clinical potential (Bale et al., 2019).

An animal model of depression should fulfill one or more of these criteria : (i) face validity, which is the similarity between the behavioral phenotype seen in animals and the clinical symptom observed in humans, (ii) construct/etiological validity, which is the similarity in the neurobiological underpinnings that trigger the condition in both animals and humans, and (iii) pharmacological validity, which is the effective application of a clinically-used antidepressant to ameliorate or attenuate symptoms in the animal model (Nestler & Hyman, 2010). Using these criteria, it is possible to compare models and choose the best model(s) to answer the question being asked about the disorder.

Stress exposure is a commonly used method to induce depressive-like behaviors in animals (Wang et al., 2017). Stress exposure is etiologically relevant, because a well-established risk factor for depression in humans is a history of life adversity or experiencing stress or trauma in early and/or adult life (Pemberton & Fuller Tyszkiewicz, 2016). Two commonly used procedures for chronically stressing adult rodents are chronic mild stress (CMS) and social defeat stress (SDS) (Wang et al., 2017). In addition, withdrawal from chronic drug use, especially alcohol, induces depressive-like behaviors in rodents (Anton et al., 2017; Getachew et al., 2017; Kang et al., 2018; Li et al., 2017; Pang et al., 2013; Renoir et al., 2012; Roni & Rahman, 2017; Walker et al., 2010; Yawalkar et al., 2018). Alcohol withdrawal fulfills criteria for both face and construct validity, because depression is often comorbid with alcohol use disorder (Boden & Fergusson, 2011) and presents a stress component, as the withdrawal phase is characterized by dysregulation of the HPA axis and activation of the extrahypothalamic stress-response system (Stephens & Wand, 2012). The next sections will briefly describe these animal models of stress-induced depression, followed by a more detailed description of the behavioral tests used to assess depressive-like behavior in rodents, in order to understand the context of brain epigenetic changes induced by stress.

2.1. Chronic Mild Stress (CMS)

The CMS model had its origin in the early 1980s by Katz and colleagues (Katz & Hersh, 1981). Today the CMS protocol does not include the severe stressors that were used in the initial studies. Instead, this paradigm has been modified to use milder stressors over a longer time period, thus achieving more realistic conditions for inducing depressive-like behaviors (Willner, 2017). In the current versions of the CMS protocol, rats or mice are exposed daily to different types of stressors, such as isolation or crowded housing, tilted home cages, dampened bedding, forced swimming, restraint and disrupted dark-light cycle (Antoniuk et al., 2019). The time of each stressor exposure can vary from 1–4 hours per day, and the protocol can last several weeks (2–8 weeks). Note that there are several different names or variations of CMS, including chronic unpredictable stress, chronic variable stress, and sub-chronic versions of these procedures that involve shorter periods of time for stressor exposure (Willner, 2017). Anhedonia is measured using the sucrose preference test (described in detail in Section 3) and is the primary readout for depressive-like behavior in the CMS model, but other tests are often performed in addition to the sucrose preference test (Burstein & Doron, 2018). Some studies also use the sucrose preference test before starting the CMS protocol to accesses the initial preference for each animal and match the control and CMS group accordingly (Wiborg, 2013). At end of the CMS protocol, the sucrose preference test often reveals two different phenotypes with respect to sucrose preference. Some animals exhibit reduced sucrose preference and are described as vulnerable, or susceptible, to chronic stress, while other animals do not reduce their sucrose preference and are labeled resilient (Willner, 2005, 2017). The CMS paradigm has also been shown to decrease performance in other motivated behaviors such as sexual and aggressive behaviors, trigger weight loss, disrupt sleep patterns, and decrease locomotor activity (Willner, 2017). Individual variability, especially in genetically identical animals (such as inbred strains of mice), suggest that epigenetic mechanisms contribute to the response to chronic stress.

2.2. Social Defeat Stress (SDS)

Despite the advantages of CMS paradigm, it has been criticized because the stressors used are purely physical, fairly artificial, and unlikely to be encountered by rats or mice in the wild. The SDS model of psychosocial stress (also referred to as the resident-intruder test), relies on innate social behavior of rodents and may be more ethologically relevant than CMS (Hollis & Kabbaj, 2014). SDS consists of introducing a male (referred as the intruder or subordinate) into the home cage of an older, aggressive, dominant male (referred as resident or dominant). The intruder is quickly attacked and forced into subordination by the resident. The intruder is generally kept in the resident cage 5–10 minutes after the first attack. During this time, the interaction can be scored to determine dominance, subordination and aggression levels. After the defeat, the intruder can be returned to his home cage, or in some protocols, a “sensory contact” phase is added, in which the intruder is housed in the same cage as its dominant separated by a polystyrene partition that prevents the physical but not the sensory interaction, allowing for psychogenic exposure to the resident without physical harm (Calvo et al., 2011; Kudryavtseva et al., 1991). The length of the SDS protocol differs between studies. While some researchers have adopted an acute model (1–3 days of defeat), others have chosen a chronic procedure (10–35 consecutive days of defeat) (Bondar et al., 2018; Jacobson-Pick et al., 2013; Krishnan et al., 2007; Razzoli et al., 2011).

The primary readout for the SDS model is the social interaction test, in which intruder mice are tested for interaction with a novel dominant mouse (Bondar et al., 2018). Other behaviors related to depression or anxiety such as sucrose preference, spontaneous locomotor activity, elevated plus maze (EPM) and forced swim test (FST) are also used (Hollis & Kabbaj, 2014). Physiological impairments (thermoregulation, cardiac, circadian, immune) and altered corticosterone levels are observed in rodents after chronic SDS (Bondar et al., 2018; Hollis & Kabbaj, 2014). The disadvantage of the standard SDS model is that it cannot be used with females because males generally do not attack females, and females typically do not exhibit aggressive behavior towards each other. However, some SDS protocols for females have been developed. For example, an intruder female mouse can be placed into the cage of a lactating dam (Jacobson-Pick et al., 2013), male urine can be applied to the intruder female, provoking attack by the resident male (Harris et al., 2018), or chemogenetic activation of the ventromedial hypothalamus in males can be used to induce aggression towards females (Takahashi et al., 2017). The SDS model is similar to the CMS model in that individual differences are found in stress responsiveness and animals can be categorized as stress-susceptible or -resilient.

2.3. Alcohol Withdrawal

The symptomatology and pathophysiology that follows termination of exposure to many drugs of abuse leads to a cluster of symptoms that resemble closely those associated with MDD (Gururajan et al., 2019). For this reason, a growing number of animal models of depression have been developed based on the effects of withdrawal from chronic exposure to drugs such as cocaine, amphetamine, opioids, nicotine and alcohol (Barr & Markou, 2005; Che et al., 2013; Getachew et al., 2017; Paterson & Markou, 2007). Studies that use alcohol withdrawal to induce depressive-like behaviors have adopted different routes and intervals of alcohol exposure and withdrawal. For example, Antón et al administered intragastric ethanol to rats for 4 days, followed by 1 or 12 days of withdrawal (Anton et al., 2017), while Kang et al gave intraperitoneal injections of ethanol twice daily to rats for 10 days followed by 24 hour withdrawal (Kang et al., 2018). Others have used ethanol vapor exposure for 3 hours per day over 10 days followed by 16 hours withdrawal (Getachew et al., 2017), or an ethanol liquid diet (Lieber-DeCarli) for 15 days followed by a 24 hour withdrawal (Chen et al., 2019). While the aforementioned studies used an acute withdrawal period, other studies have evaluated behaviors and molecular changes after a protracted abstinence of 10–12 days, 3 weeks and even 1 month (Jarman et al., 2018; Walker et al., 2010).

Alcohol withdrawal generates a range of physical and emotional behaviors, such as tail stiffness, abnormal gait/posture, tremor, decreased locomotor activity and grooming behavior; as well as depressive- and anxiety-like behavior, hyperalgesia, increased ultrasonic vocalizations, and elevated brain reward thresholds (anhedonia) (Barr & Markou, 2005). Many different tests have been performed to evaluate depressive-like behaviors after alcohol withdrawal such as the open field test, EPM, FST, sucrose splash test, and sucrose preference test (Chen et al., 2019; Getachew et al., 2017; Kang et al., 2018). An important confounding factor to consider is that the molecular changes induced by alcohol itself and withdrawal from alcohol may not be related to depressive-like behavior. It is therefore important to establish a causal role for specific epigenetic mechanisms and gene expression changes induced by alcohol specifically in depressive-like behavior. In summary, the methods described here (CMS, SDS and alcohol withdrawal) involve environmental stressors to trigger both depressive-like behaviors and epigenetic changes in the brain, providing evidence for a link between epigenetics and MDD.

3. Tests of Depressive-Like Behavior in Rodents

As mentioned above, it is possible to assess some depression-like symptoms in rodents such as anhedonia, apathy, and decreased social interaction. A well-designed study assessing depressive-like behavior will employ multiple tests in different symptomatic domains. Anhedonia is assessed by measuring sensitivity to a rewarding stimulus. Sucrose is a naturally sweet substance that rodents like to consume, and the sucrose preference test, an easily utilized test of anhedonia, takes advantage of this inclination. In this test, animals have the choice to drink either water or a sucrose solution, with sucrose concentrations ranging from 1–2% (Burstein & Doron, 2018). Reduced preference for the sucrose solution is indicative of anhedonia.

Apathy, which is defined as a decrease in motivation, or a quantitative reduction in goal-directed behavior, is measured in the sucrose splash and the social interaction tests (Planchez et al., 2019). The sucrose splash test takes advantage of the natural propensity of rodents to engage in grooming and is a behavioral measure of self-care (Hu et al., 2017; Marrocco et al., 2014; Masrour et al., 2018; Santarelli et al., 2003). This test is performed by spraying (i.e. “splashing”) a sucrose solution over the coat of the animal and measuring grooming over a short period of time. Additionally, the social interaction test can also be applied to evaluate apathy-like behavior and social aversion. This test consists of putting an unfamiliar mouse in a wire cage inside an open field arena and placing the test mouse in the open-field arena. This test is most often performed after the test mouse has been subjected to multiple rounds of “bullying”, or social defeat, by an aggressor mouse (SDS, described above). Non-defeated mice typically exhibit interest in an unfamiliar mouse and spend a lot of time interacting with it, but after SDS, mice show decreased social interaction (Avgustinovich et al., 2005). Decreased social interaction can either be interpreted as increased apathy or social aversion.

The forced swim (FST) and tail suspension tests (TST) have often been described as measures of behavioral despair or depression-like behavior, but a more accurate interpretation of these tests is that they measure passive coping (Nestler & Hyman, 2010). These tests were originally developed to screen antidepressant compounds. The FST is performed with both mice and rats, but the TST is only done with mice because the higher body weight of the rat precludes use of this test. In the FST, an animal placed in a cylindrical tank filled with water. The animal initially swims and struggle to escape, but eventually gives up and becomes immobile. Increased immobility time, or decreased latency to become immobile, is indicative that the animals have switched from an active to passive coping mechanism. The TST is similar, but in this case, the mouse is suspended by its tail and latency to immobility and time immobile are measured (Castagne et al., 2010).

Anxiety-like behavior is commonly measured along with behavioral tests of depression using with the elevated plus maze (EPM), light-dark box, and open-field tests, although the validity of these tests in measuring anxiety is disputed (Ennaceur & Chazot, 2016; Nestler & Hyman, 2010). These tests take advantage of the natural propensity of rodents to prefer enclosed and dark spaces compared with exposed and brightly lit spaces where they would be easy targets of a predator (Lezak et al., 2017). In the EPM, the animal is placed on a “plus”-shaped apparatus elevated above the floor with two closed arms with walls and two open arms. The light-dark box consists of a box containing a brightly lit chamber and a dark, enclosed chamber. Decreased time spent exploring the open arms in the EPM or the light side of the light-dark box is interpreted as increased anxiety-like behavior. In the open field test, the animal is placed in a large arena and the time spent in the center versus perimeter of the area is measured. Increased anxiety-like behavior is associated with decreased time in the center. Additionally, there are two tests of anxiety-like behavior that are based on animal feeding behavior, novelty-suppressed feeding (NSF) and novelty-induced hypophagia (NIH) (Lezak et al., 2017). These tests involve placing food pellet (NSF) or sweetened condensed milk (NIH) into an unfamiliar space. This presents a motivational conflict for the animal between the drive to eat (or consume a highly palatable substance) and avoidance of open spaces. Increased latency to consume the food is indicative of increased anxiety-like behavior. Finally, the marble-burying test is regularly applied as a measure of anxiety- and compulsive-like behavior, despite the scientific debate about its validity (de Brouwer & Wolmarans, 2018). This test is based on the natural tendency of mice to bury objects and can be performed in different configurations. Basically, glass marbles are placed over sawdust in a polystyrene cage and mice are allowed to explore for 30 minutes. The more marbles buried is proposed to reflect increased anxiety- and compulsive-like behavior (de Brouwer et al., 2019).

4. Histone Acetylation and Deacetylation in Depressive-Like Behavior

4.1. Histone Acetyltransferases (HATs) and Histone Deacetylases (HDACs)

Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) acetylate histone proteins by transferring the acetyl group from acetyl-CoA to N-terminal lysine residues on histones (Allis & Jenuwein, 2016). HATs are classified based on their subcellular localization as nuclear HATs (type A) and cytoplasmic HATs (type B). Type A HATs are responsible for acetylating histones in chromatin and the type B HATS acetylate newly translated histones to facilitate their assembly into nucleosomes (Barnes et al., 2019). Nuclear HATs are classified into five families: (1) GCN5-related N-acetyltransferases (GNATs), represented by GCN5 and p300/CBP associated factor (PCAF); (2) the MYST family, which includes TAT interacting protein 60 (TIP60) and monocytic leukemia zinc finger protein; (3) the p300/CBP family, including p300 and CREB binding protein (CBP); (4) the general transcription factor HATs, including TAF1 and TIFIIIC90; and (5) the steroid receptor co-activators (SRC)/nuclear receptor co-activators (NCoA) (Sun et al., 2015). Histone acetylation is associated with transcriptional activation, and acetylated lysines on histone proteins are recognized by bromodomain-containing proteins (so called “readers” of modified histones), which are scaffolding proteins for the formation of multiprotein transcriptional complexes (Fujisawa & Filippakopoulos, 2017).

Removal of acetyl groups is performed by a class of enzymes called histone deacetylases (HDACs) (Elvir et al., 2017; Haberland et al., 2009). The HDACs are classified into the zinc-dependent HDACs (class I, IIa, IIb, and IV) or nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent deacetylases, called sirtuins (or class III HDACs). Class I HDACs comprise HDAC1, 2, 3 and 8, while HDAC4, 5, 7 and 9 are in class IIa, HDAC6 and 10 are in in class IIb, and HDAC11 is in class IV. Some HDACs, such as HDAC6, do not deacetylate histones, but instead deacetylate non-histone proteins such as tubulin (Ganai, 2018). The separate family of sirtuins has 7 members (SIRT1–7) (Sacconnay et al. 2016).

4.2. Histone Acetylation and Deacetylation in the Nucleus Accumbens

The nucleus accumbens (NAc) is a brain region involved in motivated and emotional behaviors, and alterations in the transcriptome in this region have been linked with MDD in humans (Labonte et al., 2017). Specific HDACs (HDAC2, HDAC3 and HDAC5) in the NAc have been implicated in stress-induced depressive-like behaviors (Goudarzi et al., 2020; Renthal et al., 2007; Uchida et al., 2011). C57BL/6 mice chronically exposed to SDS had lower protein levels of HDAC5 in the NAc, and Hdac5 knockout mice exhibited an hypersensitive response to SDS, as indicated by decreased social interaction and sucrose preference (Renthal et al., 2007). Chronic SDS also decreased levels of HDAC2 mRNA and protein in the NAc of C57BL/6 mice, which were associated with increased histone H3 lysine 14 acetylation (H3K14ac) (Covington et al., 2009). Notably, H3K14ac was elevated, and HDAC2 was decreased, in postmortem NAc from human subjects with MDD (Covington et al., 2009), providing evidence that histone acetylation is dysregulated in MDD.

Infusion of non-selective HDAC inhibitors, such as suberanilohydroxamic acid (SAHA) or MS-275 (an HDAC1/3 inhibitor), directly into the NAc of mice reversed SDS-induced depressive-like behaviors (Covington et al., 2009; Dudek et al., 2020). The behavioral effects of these inhibitors could be through actions at either HDAC3 or HDAC1. HDAC3 has been implicated in stress-induced depressive-like behavior in rats (Goudarzi et al., 2020). Rats that had undergone 6 weeks of CMS exhibited decreased sucrose preference and higher expression of Hdac3 mRNA in the NAc, and treatment with the class I HDAC inhibitor valproic acid either during or after CMS nearly normalized sucrose preference and Hdac3 mRNA in the NAc (Goudarzi et al., 2020). Another study in mice (discussed in this chapter in section 7: Histone Modifications, DNA Methylation, Inflammation, and MDD) found increased Hdac1 mRNA in NAc endothelial cells of SDS-susceptible mice (Dudek et al., 2020).

Different inbred strains of mice exhibit different responses to stress and alterations in histone acetylation and deacetylation, as demonstrated by Uchida et al. (Uchida et al., 2011). BALB/c mice (in contrast to C57BL6/J mice) exposed to CMS exhibited depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors and that the mechanism behind the depression-susceptible phenotype observed in this strain of mice was likely due to increased HDAC2 and decreased mRNA of the glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (Gdnf) gene in the NAc after CMS (Uchida et al., 2011). They also found that increased HDAC2 after CMS was associated with decreased histone H3 acetylation at the Gdnf promoter and decreased Gdnf expression. Depressive-like behaviors triggered by CMS were reversed by systemic sub-chronic treatment with the pan-HDAC inhibitor, SAHA (Uchida et al., 2011). Similarly, overexpression of a dominant negative form of HDAC2, which reduces deacetylase activity, in the NAc of stressed BALB mice, increased social interaction and sucrose preference in these mice (Uchida et al., 2011). These results suggest that the epigenetic regulation of Gdnf transcription by HDAC2 confers susceptibility chronic stress. Overall, the results described here highlight the importance of HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3 and HDAC5 in the NAc in stress-induced depressive-like behaviors, as well as the potential therapeutic use of HDAC inhibitors to attenuate depressive-like behaviors triggered by chronic stress.

4.3. Histone Acetylation and Deacetylation in the Hippocampus

Another brain region involved in depression is the hippocampus (Fanselow & Dong, 2010). Several studies in mice and rats have demonstrated a role for histone acetylation and deacetylation in the hippocampus in stress-induced depressive-like behaviors (Abe-Higuchi et al., 2016; Covington, Vialou, et al., 2011; Han et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2014). Chronic SDS in C57BL/6J male mice decreased social interaction and sucrose preference, and also triggered a transient increase, followed by a persistent decrease, in the levels of H3K14ac in the hippocampus (Covington, Vialou, et al., 2011). In the same work, systemic continuous administration of MS-275 to mice undergoing SDS increased both H3K14ac in the hippocampus and sucrose preference but did not affect social interaction. However, if mice were group-housed after chronic stress instead of individually housed (i.e., socially isolated), then MS-275 was able to increase social interaction (Covington, Vialou, et al., 2011). Based on these results, it seems likely that environmental enrichment such as group housing can alter histone acetylation (probably at other sites than H3K14) after chronic stress and thus modulate behavioral responses to an HDAC inhibitor.

In a different stress model in mice consisting of 14 days of chronic restraint stress, levels of H3K9/14ac, phosphorylated cAMP responsive element binding protein (pCREB), and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) were decreased simultaneously with decreased HDAC2 and HDAC5 in the hippocampus, especially in the dentate gyrus (Han et al., 2014). Interestingly, systemic treatment with the class I and II HDAC inhibitor, sodium butyrate, increased H3K9/14ac, HDAC2, pCREB and BDNF in the hippocampus of stressed mice (Han et al., 2014). Sodium butyrate also reversed the stress-induced decrease in sucrose preference, decreased immobility in the TST and FST, and decreased the time spent on the dark side of the light-dark box (Han et al., 2014). The simultaneous reduction in HDAC2, HDAC5, and H4K9/14ac levels after chronic restraint stress suggest that HDAC2 and HDAC5 are not responsible for stress-induced H3K9/14 deacetylation and implicate another class I or class II HDAC in decreased H3K9/14 acetylation and increased depressive-like behaviors after chronic restraint stress.

Another HDAC inhibitor, sodium valproate, normalized the stress-induced reduction in hippocampal levels of H3K9ac and H4K12ac and alleviated both depression- and anxiety-like behaviors in in rats after CMS (Liu et al., 2014). This was likely through an HDAC5-dependent mechanism, because HDAC5 levels were elevated after CMS in rats and returned to normal after sodium valproate treatment (Liu et al., 2014). In an alcohol withdrawal procedure that induces depressive-like behavior, H3K9ac was decreased in the rat hippocampus, along with increased HDAC2 and HDAC6 protein (Chen et al., 2019). Systemic treatment with SAHA during withdrawal decreased HDAC2 and increased H3K9ac, and ameliorated depression-like behavior as measured by increased sucrose preference and grooming time in the sucrose splash test (Chen et al., 2019). These results suggest that either HDAC2 or HDAC6 could be involved in the decrease in hippocampal H3K9ac and depression-like behavior during alcohol withdrawal.

The class III HDAC, SIRT1, has also been shown to influence stress-induced depressive-like behavior. SIRT1 was reduced in the dentate gyrus region of the hippocampus of stress-susceptible BALB mice after CMS or repeated restraint stress (Abe-Higuchi et al., 2016). Infusion of sirtinol, a SIRT1/2 inhibitor, or EX-527, a selective SIRT1 inhibitor, into the hippocampus of non-stressed BALB mice decreased social interaction and increased the latency to feed in the NIH test, indicating that SIRT1 inhibition increased depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors (Abe-Higuchi et al., 2016). In contrast, systemic injection of a non-selective SIRT activator, RSV, or intra-hippocampal infusion of a selective SIRT1 activator, SRT2104, prevented depressive-like behaviors induced by repeated restraint stress in BALB mice, suggesting that activating SIRT1 promotes stress resilience (Abe-Higuchi et al., 2016). This bi-directional regulation of depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors was also apparent with overexpression of wild-type and a dominant negative SIRT1 in the dentate gyrus, with wild-type SIRT1 overexpression increasing stress resilience and dominant negative SIRT1 causing stress susceptibility (Abe-Higuchi et al., 2016).

Finally, overexpression of HDAC4 in the hippocampus increased immobility time and decreased latency to immobility in the FST of non-stressed rats, indicating that higher levels of HDAC4 in the hippocampus increase vulnerability to depression (Sarkar et al., 2014). Increased HDAC4 was also associated with decreased hippocampal expression of the HDAC4 target genes guanine nucleotide-binding protein alpha inhibiting 1 (Gnai1) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (Sarkar et al., 2014).

Physical exercise has been proposed as an effective adjunct to antidepressants in the treatment of MDD (Craft & Perna, 2004; Knapen et al., 2015; Kvam et al., 2016). Exercise is known to improve mood and induce BDNF expression in the hippocampus of animals (Neeper et al., 1996; Russo-Neustadt et al., 1999; Zheng et al., 2006). One intriguing study examined the epigenetic mechanism by which exercise might increase BDNF expression and discovered that wheel-running reduced expression of Hdac2 and Hdac3, and reduced binding of HDAC3 at the Bdnf promoter in the mouse hippocampus (Sleiman et al., 2016). Exercise also increased levels of the ketone body, D-β-hydroxybutyrate (DBHB), a natural HDAC inhibitor, in the hippocampus, and intracerebroventricular infusion of DBHB increased levels of BDNF in the hippocampus (Sleiman et al., 2016). These results indicate that the anti-depressant effects of exercise may be through elevations of a natural HDAC inhibitor in the hippocampus.

4.4. Histone Acetylation and Deacetylation in the Prefrontal Cortex

The prefrontal cortex is another anatomical site that mediates both depression and cognition. Two studies examined a potential role for SIRT2 in the prefrontal cortex in depressive-like behavior. Inhibition of SIRT2 with 33i increased serotonin levels and glutamate receptor subunits in the prefrontal cortex and alleviated CMS-induced depressive-like behavior in mice (Erburu et al., 2017). In another study, chronic SIRT2 inhibition with 33i also reversed anhedonia in a depression model involving heterozygous VGLUT1 knockout mice (Munoz-Cobo et al., 2017). These studies suggest that SIRT2 could be a potential therapeutic target in the treatment of MDD and should be further investigated.

Another potential therapeutic strategy is the use of the acetyl donor, acetyl-L-carnitine (LAC). Treatment of rats that naturally exhibit depressive-like behavior (Flinders Sensitive line) with LAC reduced immobility time in the FST and increased sucrose preference by increasing the expression and acetylation (H3K27ac) at the metabotropic glutamate receptor 2 (mGlu2, encoded by Grm2) and Bdnf genes in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Nasca et al., 2013). Similarly, treatment of mice that had undergone CMS with LAC reduced depressive-like behavior (Nasca et al., 2013), suggesting that LAC could potentially be used to treat patients with MDD. The protein encoded by the Crtc1 gene is a CREB co-activator that binds to CREB and helps recruit the HAT, CBP, and RNA polymerase II to activate CREB-mediated transcription. Homozygous Crtc1 knockout mice exhibit depressive-like behavior as measured in the FST, sucrose preference test, and social interaction test, with an associated decreased expression of the CREB target genes such Bdnf in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Breuillaud et al., 2012). Systemic administration of SAHA to Crtc1 knockout mice decreased immobility time in the FST, and increased histone H3 and H4 acetylation in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, and Bdnf expression in the prefrontal cortex (Meylan et al., 2016). These findings support the possibility that inhibiting HDACs or increasing histone acetylation may be a useful therapeutic strategy for MDD.

5. Histone Methylation and Demethylation in MDD

5.1. Histone Methyltransferases and Demethylases

Histones are methylated on lysine and arginine residues in their N-terminal tails by the enzymatic activity of lysine methyltransferases (KMTs) and protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs). In mammals, there are 9 PRMTs (Yang & Bedford, 2013) and 24 KMTs (Husmann & Gozani, 2019), with 23 of the KMTs containing a SET domain (SET is an acronym based on the first letter of three Drosophila proteins containing this domain: suvar3–9, enhancer of zeste, and trithorax). The remaining KMT, hDOT1l, does not have a SET domain, but instead contains a seven-β-strand domain (Husmann & Gozani, 2019). Lysine residues on histone proteins can be modified by one (me1), two (me2), or three (me3) methyl groups, referred to as mono-, di-, or trimethylation, respectively, and arginine residues can be mono- or dimethylated. Methylation of histones is associated with either transcriptional activation or repression, depending on the methylated lysine and the degree of methylation (Greer & Shi, 2012; Jarome et al., 2014). The removal of methylation groups from lysine and arginine residues is catalyzed by the histone demethylases (KDMs) and protein arginine demethylases (PRDMs) (Greer & Shi, 2012). There are two types of histone lysine demethylases, those that contain a Jumonji C (JmJC) domain, which are iron-dependent dioxygenases, and the amine oxidases. Less is known about the arginine demethylases (Greer & Shi, 2012). In the next few sections, we will discuss findings regarding the KMTs, KDMs, and methylation marks implicated in MDD.

5.2. G9a/GLP and H3K9 Methylation in Depressive-Like Behavior

G9a and GLP are two related KMTs that can exert their activities independently, or more commonly, as a G9a/GLP heteromeric complex (Shinkai & Tachibana, 2011). This complex methylates histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me and H3K9me2), and also cooperates with DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) to add repressive methyl groups to cytosine residues in DNA (Tachibana et al., 2008). Methylation of H3K9 at promoters is associated with repressed gene transcription. Postnatal knockout of G9a or GLP in mouse forebrain neurons led to several behavioral abnormalities, including decreased sucrose preference (Schaefer et al., 2009). Chronic SDS in mice caused a reduction in both G9a and GLP expression, and H3K9me2 levels, in the NAc of stress-susceptible mice (Covington, Maze, et al., 2011). Depressed human subjects also exhibited reduced G9a, GLP, and H3K9me2 in the NAc (Covington, Maze, et al., 2011). Knocking out G9a in the NAc increased the susceptibility of mice to develop depressive-like behavior (decreased social interaction and sucrose preference) after SDS, while overexpression of G9a in the NAc after SDS ameliorated depressive-like behavior (Covington, Maze, et al., 2011). In addition, repeated cocaine exposure prior to SDS increased the severity of depressive-like behavior in mice, and overexpression of G9a in the NAc after cocaine administration prevent the stress-induced development of depressive-like behavior (Covington, Maze, et al., 2011). A genome-wide analysis of H3K9/K27me2 levels at gene promoters found changes at the promoters of many genes in the NAc of stress-susceptible mice after SDS and after social isolation, another model of depression. The changes in histone methylation induced by SDS were not observed in stress-resilient mice, and were reversed by chronic antidepressant treatment in the stress-susceptible mice (Wilkinson et al., 2009). Similar decreases in G9a and H3K9me2 have been observed in the amygdala of mice subjected to chronic restraint stress, which caused increased immobility time in the FST and TST (Kim et al., 2016). Chronic restraint stress increased expression of genes encoding the neuropeptides oxytocin (Oxt) and arginine vasopression (Avp) in the basolateral amygdala, with a corresponding reduction of G9a binding and H3K9me2 at their promoters (Kim et al., 2016). Interestingly, the molecular and behavioral changes induced by chronic restraint stress were reversed by exercise, and knockdown of either Oxt or Avp in the basolateral amygdala also reversed chronic restraint stress-induced depressive-like behavior (Kim et al., 2016). In the hippocampus, acute restraint stress in mice increased H3K9me3 and reduced H3K9me in the CA1 and dentate gyrus (Hunter et al., 2009). Together, these studies suggest that methylation of H3K9 at specific gene loci by G9a/GLP in several brain regions promotes resilience to stress.

5.3. H3K27 Methylation in Depressive-Like Behavior

Similar to methylation of H3K9, methylation of H3K27 is also a transcriptionally repressive epigenetic mark that is implicated in the development of depression-like behavior in mice (Pan et al., 2018). Chronic SDS in mice increased H3K27me2 at specific Bdnf promoter sites (III and IV) in the hippocampus, which was associated with decreased Bdnf transcript (Tsankova et al., 2006). This modification was extremely long-lasting, being present at the Bdnf promoter for a month after SDS. In postmortem prefrontal cortex of patients diagnosed with MDD, BDNF mRNA expression was decreased and H3K27me3 was increased at BDNF promoter IV compared with control subjects and subjects with MDD with a history of antidepressant use (Chen et al., 2011). These pre-clinical and clinical results implicate lower BDNF expression and associated increased repressive H3K27me3 at the BDNF promoter in the pathogenesis of MDD. Another gene that is regulated by H3K27me3 is the RAS-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1) gene, which plays an important role in the regulation of synaptic structure. Chronic SDS and social isolation stress reduced the expression of Rac1, with a corresponding increase in H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 at the Rac1 promoter, in the NAc of stress-susceptible mice (Golden et al., 2013; Wilkinson et al., 2009). Similarly, increased H3K27me3 at the RAC1 promoter was also observed in the NAc of subjects with depression, suggesting an epigenetic regulation of RAC1 in the NAc as a potential mechanism involved in MDD (Golden et al., 2013). Finally, a recent study demonstrated that the gene encoding the neuropeptide VGF (Vgf) was decreased in the prefrontal cortex (specifically, prelimbic region) of stress-susceptible mice after chronic SDS and that this decrease contributed to susceptibility to SDS (Liu et al., 2019). The decrease in Vgf expression was due to the upregulation of the chromodomain-Y-like (CDYL) protein, which is a crotonyl-CoA hydratase that decreases histone crotonylation and cooperates with the histone methyltransferase EZH2 to increase levels of repressive H3K27me3 at the Vgf promoter in response to SDS (Liu et al., 2019).

6. DNA Methylation and Demethylation in MDD

6.1. DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs) and DNA Demethylating Enzymes

Eukaryotic DNA is modified by the addition of a methyl group to the 5th carbon position of a cytosine nucleotide (5mC), mainly in sequences with adjacent guanine nucleotides (CpG dinucleotides). CpG dinucleotides are enriched in regions of the genome known as CpG “islands” which have been found in proximal gene promoter regions and play an important role in the regulation of gene transcription (Ehrlich, 2019). Although DNA methylation occurs mainly at CpG dinucleotides, methylation at cytosines followed by adenine, thymine, or another cytosine are also found throughout the genome, including in repetitive sequences, enhancers, promoters, and within genes (Jang et al., 2017). DNA methylation at gene promoter regions is generally associated with transcriptional repression, although there is evidence that DNA methylation at active enhancers or in the gene body are associated with transcriptional activation (Baubec et al., 2015; Maunakea et al., 2010; Yin et al., 2017). DNA methylation is catalyzed by the DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) DNMT1, DNMT2, DNMT3A, DNMT3B, and DNMT3L (Lyko, 2018). DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B are the canonical DNMTs that add methyl groups to cytosines, whereas DNMT2 and DNMT3L, although having sequence conservation with the other DNMTs, do not possess DNMT catalytic activity (Lyko, 2018).

DNA methylation was once thought to be a permanent genomic modification; however, methyl groups can be actively removed in a multistep process by the activity of the ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes and components of the base excision repair pathway (Melamed et al., 2018; Wu & Zhang, 2017). TETs (TET1, TET2, and TET3) are dioxygenases that catalyze the oxidation of 5mC to 5-hydroxylated mC (5hmC). 5hmC is further oxidized by TETs to 5-formylcytosine, followed by 5-carboxycytosine. Final removal of the modified cytosine is accomplished by base excision repair processes. In the adult central nervous system, 5hmC is highly abundant and enriched in the gene bodies of actively transcribed genes and at exon/intron boundaries, suggesting potential roles for 5hmC in gene transcription and splicing, respectively (Wu & Zhang, 2017). Therefore DNA methylation, similarly to the histone modifications described above, can be actively added, or removed after exposure to environmental stimuli such as stress, leading to changes in gene expression and subsequently, behavior (Elliott et al., 2010; Uchida et al., 2011; Xiang et al., 2020).

6.2. DNA Methylation and Demethylation in the Nucleus Accumbens

As mentioned above in the section on histone acetylation and deacetylation, changes in histone acetylation in the NAc are associated with stress-induced depressive-like behavior, and DNA methylation in the NAc has also been implicated in depressive-like behaviors. Expression of the Dnmt3a transcript increased in the NAc at 1 and 10 days after the SDS procedure (LaPlant et al., 2010). To test the influence of Dnmt3a on susceptibility to SDS, a viral vector overexpressing Dnmt3a was injected into the NAc of mice, and then the mice were submitted to a submaximal defeat stress in which animals undergo just 1 day of defeat, which is not sufficient to induce social avoidance (LaPlant et al., 2010). Dnmt3a overexpression in the NAc attenuated social interaction, compared with control animals injected with a control virus. These results suggest that higher levels of Dnmt3a in the NAc (and presumably DNA methylation) increases depression susceptibility (LaPlant et al., 2010). To further test this hypothesis, authors infused RG108, a DNMT inhibitor, into the NAc between 1 and 10 days after defeat stress and observed increased social interaction in defeated mice, showing that a DNMT inhibitor in the NAc had an anti-depressant-like effect (LaPlant et al., 2010).

A gene whose expression decreased in the NAc after CMS is Gdnf. Overexpression of Gdnf in the NAc of BALB mice subjected to CMS increased social interaction and sucrose preference, indicating that higher levels of Gdnf in the NAc can act as an anti-depressant (Uchida et al., 2011). After the CMS procedure, hypermethylation and increased binding of the methyl CpG binding protein 2, MECP2, were found at the Gdnf promoter in the NAc, consistent with decreased Gdnf expression (Uchida et al., 2011). Infusion of the DNMT inhibitor, zebularine, into the NAc of stressed BALB mice increased Gdnf mRNA levels (DNA methylation at the promoter was not determined after zebularine infusion), social interaction time, and sucrose preference, and decreased immobility time in the forced swim test and latency to feed in the novelty-suppressed feeding test, all anti-depressant phenotypes (Uchida et al., 2011). Similar results were found with infusion of another DNMT inhibitor, RG-108, in the NAc of BALB mice on social interaction and sucrose preference (Uchida et al., 2011). Notably, Dnmt1 and Dnmt3a transcripts were induced in the NAc of BALB mice after CMS, providing a likely explanation for the effectiveness of the DNMT inhibitors in this depression model (Uchida et al., 2011).

TET1, one of the DNA dioxygenases involved in DNA demethylation, also appears to be involved in depression-like behaviors through its action in the NAc. Tet1 mRNA expression was decreased in the NAc of stress-susceptible (but not stress-resilient) mice after SDS. Surprisingly, knockout of Tet1 in NAc neurons resulted in anti-depressant and anti-anxiety phenotypes, as measured by increased sucrose preference, social interaction time after SDS, time in the open arms of the EPM, and time in the center in the OFT (Feng et al., 2017). These results suggest that the downregulation of Tet1 mRNA after SDS in stress-susceptible mice is a homeostatic response to chronic stress, but that it is not enough to overcome the adverse behavioral effects of chronic stress. RNA-Seq was performed in the NAc of Tet1 knockout mice to identify potential genes regulated by Tet1. Many of the changes in gene expression between control and Tet1 knockout mice were in immune-response pathways (Feng et al., 2017). A more detailed discussion of the implications of epigenetic regulation of immune-response genes is provided in section 7.

Another protein involved in DNA demethylation is growth arrest and DNA damage inducible β (GADD45B), which functions in the base excision repair pathway (Sultan & Sweatt, 2013). In contrast to the Tet1 results described above, Gadd45b mRNA levels were increased in the NAc of stress-susceptible mice after chronic SDS (Labonte et al., 2019). However, knockdown of Gadd45b in the NAc of stress-susceptible mice after chronic SDS had a similar effect as knockout of Tet1, in that it increased social interaction time (Labonte et al., 2019). Several candidate genes associated with stress were examined for DNA methylation changes with Gadd45b knockdown in the NAc. Reduction of Gadd45b resulted in differential methylation at several genes (Gad1, Dlx5, Nrtn, and Ntrk2) in the NAc with corresponding alterations in the expression of some of these genes (Labonte et al., 2019). These results indicate that DNA demethylation in the NAc is involved in vulnerability to chronic stress.

6.3. DNA Methylation in the Hippocampus and Prefrontal Cortex

Several groups have examined the role of DNMTs in depressive-like behavior using pharmacological approaches. Systemic administration of the DNMT inhibitors, 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine (5-azaD) or 5-azacytidine (5-azaC), to acutely stressed rats reduced depression-like behavior as measured in the FST, and total DNA methylation and protein levels of BDNF were increased and decreased, respectively, in the hippocampus of rats that had received 5-azaD (Sales et al., 2011). When 5-azaD or RG-108 was infused directly into the rat hippocampus, rats had decreased immobility time in the FST, indicating that DNMTs in the hippocampus may be involved in depressive-like behavior (Sales et al., 2011). Systemic administration of DNMT inhibitors to mice also reduced immobility time in the FST, with an associated decrease in total DNA methylation in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Sales & Joca, 2016).

One gene that was decreased in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex by chronic stress in rats is Dpysl2, which encodes a member of the collapsin response mediator protein (CRMP2) that regulates cytoskeletal dynamics and synaptic transmission (Xiang et al., 2020). DNA methylation at the Dpysl2 promoter increased after chronic stress in the rat hippocampus, but not the prefrontal cortex (Xiang et al., 2020), indicating neuroanatomical differences in epigenetic regulation of this specific gene in response to chronic stress.

The paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) is an important anatomical node in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis that regulates the stress response by producing corticotropin releasing factor (CRF, also known as CRH). Chronic SDS increased the expression of the gene encoding CRF (Crh) in mice that were stress-susceptible but not in mice that were stress-resilient (Elliott et al., 2010). This was associated with decreased DNA methylation at the Crh promoter and decreased expression of Dnmt3a in the PVN of stress-susceptible vs. stress-resilient mice (Elliott et al., 2010). Interestingly a second study showed that the expression of Gadd45b, an enzyme involved DNA demethylation via the base excision repair pathway (Niehrs & Schafer, 2012), was also increased in the PVN after chronic SDS, suggesting that DNA demethylation might be responsible for the induction of Crh after chronic SDS (Niehrs & Schafer, 2012).

7. Histone Modifications, DNA Methylation, Inflammation, and MDD

MDD is associated with elevated systemic and central nervous system inflammation (Enache et al., 2019; Miller et al., 2009), and interestingly, HDAC inhibitors have been shown to reduce both the systemic inflammatory response and neuroimmune activation (Faraco et al., 2009). One hypothesis is that HDAC inhibitors might reduce stress-induced depressive-like behavior in animals by suppressing the expression of pro-inflammatory genes. In a model of depression in which mice were treated chronically with corticosterone, SAHA treatment ameliorated CORT-induced depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors, with a corresponding suppression of CORT-induced expression of the Nfkb1 gene, which encodes a subunit of the NF-κB transcription factor complex, and a reduction in hippocampal levels of tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukin 1β (IL-1β) (Kv et al., 2018). Injections of the bacterial endotoxin and innate immune activator, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), into mice increased immobility in the FST, and systemic administration of the HDAC inhibitor sodium butyrate decreased immobility and LPS-induced activation of microglia in the hippocampus (Yamawaki et al., 2018). Studies with cultured microglia have demonstrated that HDAC inhibitors can reduce microglia activation and cytokine gene expression (Faraco et al., 2009; Kannan et al., 2013), indicating that HDAC inhibitors act in microglia to suppress inflammation.

Chronic stress also alters the integrity of the blood brain barrier (BBB), allowing for entry of circulating cytokines and immune effector cells such as monocytes (Menard et al., 2017). One mechanism by which chronic stress interferes with BBB function and promotes depressive-like behavior is through decreased expression of the gene encoding the endothelial tight junction protein, claudin 5 (Cldn5) in blood vessels in the NAc of stress-susceptible mice after SDS (Menard et al., 2017). Chronic SDS increased acetylation of histone H3 and decreased repressive histone methylation (H3K27me3), in the NAc of stress-resilient mice (Dudek et al., 2020). In contrast, stress-susceptible mice had increased Hdac1 in NAc endothelial cells compared to stress-resilient mice (Dudek et al., 2020). Intra-NAc infusion of MS-275 after SDS rescued Cldn5 expression and increased social interaction of stress-susceptible mice (Dudek et al., 2020). Of note, HDAC1 expression was also elevated and correlated with decreased CLDN5 expression in human subjects with MDD that were not on antidepressants (Dudek et al., 2020). These results suggest that inhibition of HDACs might suppress inflammation, restore BBB function, and potentially ameliorate depression symptoms in patients with MDD.

Removal of repressive methyl groups from H3K27 is performed by the histone demethylase KDM6B, also known as JMJD3 (Hong et al., 2007). KDM6B regulates microglial activation and has been proposed as a crucial element in the induction of inflammatory cytokines (De Santa et al., 2007). KDM6B participates in the inflammation process by interacting with transcription factors and activating gene transcription through the release of repressive polycomb complexes via H3K27me2 and H3K27me3 demethylation (Salminen et al., 2014). Increased expression of inflammatory cytokines has been reported to be involved in the pathogenesis and susceptibility to depression (Dowlati et al., 2010; Wohleb et al., 2016). A study done by Wang and colleagues linked inflammation, epigenetic regulation, and depression susceptibility (R. Wang et al., 2018). They demonstrated that adolescent rats exposed to CMS exhibited depressive- and anxiety-like behavior, microglia activation, higher levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-1β, increased KDM6B expression, and decreased H3K27me3 levels in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus (R. Wang et al., 2018). These results suggest a potential role of histone demethylase KDM6B in stress-induced inflammation and susceptibility to depression through microglial activation and pro-inflammatory cytokine induction.

As mentioned above, MDD is highly comorbid with chronic inflammatory illnesses (Dowlati et al., 2010; Wohleb et al., 2016), and chronic stress exposure leads to increases in circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Wohleb et al., 2016). Levels of both IL-6 and TNFα are significantly increased in patients with MDD versus healthy controls (Dowlati et al., 2010; Howren et al., 2009). It is intriguing to speculate that reducing peripheral inflammation could be a novel approach to treating MDD. In a screen for phytochemicals with the potential to improve neurological and psychiatric disorders, Wang and colleagues identified a bioactive dietary polyphenol preparation derived from grape juice, grape seed extract, and trans-resveratrol that was able to increase the proportion of mice resilient to chronic SDS (J. Wang et al., 2018). They further isolated two phenolic metabolites of this polyphenol preparation, DHCA and Mal-gluc. DHCA blocked the increase in IL-6 induced by the bacterial endotoxin, lipopolysaccharide, in mouse peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), and reduced the expression of Dnmt1. DHCA also reduced the transcriptional activity of CpG-rich sequences in the Il6 gene introns 1 and 3 similarly to a DNA methylation inhibitor, suggesting that DHCA alters DNA methylation at these CpG-rich intronic sequences. Mal-gluc, in contrast to DHCA, had no effect on IL-6 levels, but instead increased the expression of Rac1, a gene that regulates synaptic plasticity in the NAc, and increased histone acetylation at the Rac1 promoter, in mouse primary neuronal cultures (J. Wang et al., 2018). Importantly, treatment of mice with both DHCA and Mal-gluc during or after chronic SDS increased social interaction time and sucrose preference. In addition, the combination of DHCA and Mal-gluc reduced plasma IL-6 levels induced by chronic SDS and increased Rac1 expression in the NAc. DHCA and Mal-gluc treatment during a CMS procedure also improved behaviors related to anxiety and depression in both male and female mice (J. Wang et al., 2018). Interestingly, administration of either DHCA or Mal-gluc alone had no behavioral effects, demonstrating that the combined treatment was necessary to ameliorate stress-induced depressive-like behaviors. These findings suggest that treatment with DHCA and Mal-gluc has the potential to be therapeutically effective in people suffering from MDD.

8. Sex Differences in Epigenetic Mechanisms Underlying Depression

Women are twice as likely as men to suffer from MDD (Seedat et al., 2009). Studies in humans and rodents have found strikingly different brain transcriptional changes between sexes in MDD and after chronic stress in rodents (Hodes et al., 2015; Labonte et al., 2017; Pfau et al., 2016; Seney et al., 2018), suggesting that in addition to transcriptome differences, epigenetic mechanisms may also be sexually dimorphic and contribute to depression. Depressive-like behaviors can be induced by sub-chronic variable stress (SCVS), a method that is similar to CMS (Willner, 2017), in female, but not male, mice (Hodes et al., 2015). Dnmt3a transcription was induced more strongly in the NAc of female mice after SCVS, and knockout of Dnmt3a in the NAc of female mice increased resilience to SCVS and shifted the NAc transcriptional profile to more closely resemble stress-resilient male mice (Hodes et al., 2015). Signaling pathways that shifted in females with NAc Dnmt3a knockout towards males included immune response and CRF. Interestingly, overexpression of Dnmt3a in the NAc of male and female mice increased susceptibility to SCVS, providing evidence that stress-induced induction of DNMT3A is responsible for increased stress susceptibility (Hodes et al., 2015). DNA methylation at the Crh promoter in the PVN was also shown to be different in male and female rats subjected to a chronic variable stress protocol, with females exhibiting higher levels of DNA methylation at Crh after stress (Sterrenburg et al., 2011). Investigation of sex differences in transcriptional and epigenetic responses to chronic stress and the causal role of these changes is still nascent and requires further investigation. In addition, the contributions of hormonal and. genetic (X or Y chromosome-derived genes) factors in epigenetic alterations induced by stress have yet to be determined.

9. Conclusions

It has become clear that chronic stress alters the expression of epigenetic enzymes and associated histone post-translational modifications and DNA methylation in several brain regions associated with depression such as the NAc, hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and PVN. In addition to anatomical specificity, stress also has locus-specific effects on epigenetic modifications and gene expression. At the risk of oversimplification, pan-HDAC and DNMT inhibitors, and knockout of DNA demethylating enzymes, have anti-depressant effects, while SIRT1 inhibition and knockout of the histone methyltransferases G9a/GLP are pro-depressive. HDAC and DNMT inhibitors have pleiotropic effects that include suppression of inflammation-related genes and induction of neurotrophic factors such as Bdnf and Gdnf, and genes involved in synaptic structural plasticity such as Rac1. Novel MDD therapeutics based on manipulating the activity of epigenetic enzymes have the potential to suppress an overactive inflammatory response, increase the expression of neurotrophic factors, and increase synaptic plasticity. However, therapeutic strategies that target epigenetic enzymes in the treatment of MDD will need to be rigorously evaluated for toxicity and side effects. These enzymes are present in most tissues and small molecules targeting them will likely have significant side effects. Future studies should also identify the combinatorial epigenetic modifications, and include novel histone modifications, that occur on specific genes after chronic stress, and their interactions, in order to provide a more complete picture of the complex effects of chronic stress on the brain. Finally, more studies in females are clearly needed to understand sex differences in epigenetic mechanisms underlying depression, given that women are more likely than men to suffer from MDD.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (P50 AA022538, U01 AA020912, and R01 AA027231 to AWL).

References

- Abe-Higuchi N, Uchida S, Yamagata H, Higuchi F, Hobara T, Hara K, Kobayashi A, & Watanabe Y (2016, December 1). Hippocampal Sirtuin 1 Signaling Mediates Depression-like Behavior. Biol Psychiatry, 80(11), 815–826. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allis CD, & Jenuwein T (2016, August). The molecular hallmarks of epigenetic control. Nat Rev Genet, 17(8), 487–500. 10.1038/nrg.2016.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton M, Alen F, Gomez de Heras R, Serrano A, Pavon FJ, Leza JC, Garcia-Bueno B, Rodriguez de Fonseca F, & Orio L (2017, May). Oleoylethanolamide prevents neuroimmune HMGB1/TLR4/NF-kB danger signaling in rat frontal cortex and depressive-like behavior induced by ethanol binge administration. Addict Biol, 22(3), 724–741. 10.1111/adb.12365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniuk S, Bijata M, Ponimaskin E, & Wlodarczyk J (2019, April). Chronic unpredictable mild stress for modeling depression in rodents: Meta-analysis of model reliability. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 99, 101–116. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avgustinovich DF, Kovalenko IL, & Kudryavtseva NN (2005, November). A model of anxious depression: persistence of behavioral pathology. Neurosci Behav Physiol, 35(9), 917–924. 10.1007/s11055-005-0146-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale TL, Abel T, Akil H, Carlezon WA Jr., Moghaddam B, Nestler EJ, Ressler KJ, & Thompson SM (2019, July). The critical importance of basic animal research for neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology, 44(8), 1349–1353. 10.1038/s41386-019-0405-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CE, English DM, & Cowley SM (2019, April 23). Acetylation & Co: an expanding repertoire of histone acylations regulates chromatin and transcription. Essays Biochem, 63(1), 97–107. 10.1042/EBC20180061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr AM, & Markou A (2005). Psychostimulant withdrawal as an inducing condition in animal models of depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 29(4–5), 675–706. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baubec T, Colombo DF, Wirbelauer C, Schmidt J, Burger L, Krebs AR, Akalin A, & Schubeler D (2015, April 9). Genomic profiling of DNA methyltransferases reveals a role for DNMT3B in genic methylation. Nature, 520(7546), 243–247. 10.1038/nature14176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden JM, & Fergusson DM (2011, May). Alcohol and depression. Addiction, 106(5), 906–914. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03351.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondar N, Bryzgalov L, Ershov N, Gusev F, Reshetnikov V, Avgustinovich D, Tenditnik M, Rogaev E, & Merkulova T (2018, April). Molecular Adaptations to Social Defeat Stress and Induced Depression in Mice. Mol Neurobiol, 55(4), 3394–3407. 10.1007/s12035-017-0586-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuillaud L, Rossetti C, Meylan EM, Merinat C, Halfon O, Magistretti PJ, & Cardinaux JR (2012, October 1). Deletion of CREB-regulated transcription coactivator 1 induces pathological aggression, depression-related behaviors, and neuroplasticity genes dysregulation in mice. Biol Psychiatry, 72(7), 528–536. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein O, & Doron R (2018, October 24). The Unpredictable Chronic Mild Stress Protocol for Inducing Anhedonia in Mice. J Vis Exp(140). 10.3791/58184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo N, Cecchi M, Kabbaj M, Watson SJ, & Akil H (2011, June 2). Differential effects of social defeat in rats with high and low locomotor response to novelty. Neuroscience, 183, 81–89. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.03.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagne V, Moser P, Roux S, & Porsolt RD (2010, June). Rodent models of depression: forced swim and tail suspension behavioral despair tests in rats and mice. Curr Protoc Pharmacol, Chapter 5, Unit 5 8. 10.1002/0471141755.ph0508s49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che Y, Cui YH, Tan H, Andreazza AC, Young LT, & Wang JF (2013, June). Abstinence from repeated amphetamine treatment induces depressive-like behaviors and oxidative damage in rat brain. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 227(4), 605–614. 10.1007/s00213-013-2993-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ES, Ernst C, & Turecki G (2011, April). The epigenetic effects of antidepressant treatment on human prefrontal cortex BDNF expression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol, 14(3), 427–429. 10.1017/S1461145710001422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WY, Zhang H, Gatta E, Glover EJ, Pandey SC, & Lasek AW (2019, August). The histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) alleviates depression-like behavior and normalizes epigenetic changes in the hippocampus during ethanol withdrawal. Alcohol, 78, 79–87. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2019.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington HE 3rd, Maze I, LaPlant QC, Vialou VF, Ohnishi YN, Berton O, Fass DM, Renthal W, Rush AJ 3rd, Wu EY, Ghose S, Krishnan V, Russo SJ, Tamminga C, Haggarty SJ, & Nestler EJ (2009, September 16). Antidepressant actions of histone deacetylase inhibitors. J Neurosci, 29(37), 11451–11460. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1758-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington HE 3rd, Maze I, Sun H, Bomze HM, DeMaio KD, Wu EY, Dietz DM, Lobo MK, Ghose S, Mouzon E, Neve RL, Tamminga CA, & Nestler EJ (2011, August 25). A role for repressive histone methylation in cocaine-induced vulnerability to stress. Neuron, 71(4), 656–670. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington HE 3rd, Vialou VF, LaPlant Q, Ohnishi YN, & Nestler EJ (2011, April 15). Hippocampal-dependent antidepressant-like activity of histone deacetylase inhibition. Neurosci Lett, 493(3), 122–126. 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft LL, & Perna FM (2004). The Benefits of Exercise for the Clinically Depressed. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry, 6(3), 104–111. 10.4088/pcc.v06n0301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeh B, Fuchs E, Wiborg O, & Simon M (2016, January 4). Animal models of major depression and their clinical implications. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 64, 293–310. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Brouwer G, Fick A, Harvey BH, & Wolmarans W (2019, February). A critical inquiry into marble-burying as a preclinical screening paradigm of relevance for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder: Mapping the way forward. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci, 19(1), 1–39. 10.3758/s13415-018-00653-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Brouwer G, & Wolmarans W (2018, December). Back to basics: A methodological perspective on marble-burying behavior as a screening test for psychiatric illness. Behav Processes, 157, 590–600. 10.1016/j.beproc.2018.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santa F, Totaro MG, Prosperini E, Notarbartolo S, Testa G, & Natoli G (2007, September 21). The histone H3 lysine-27 demethylase Jmjd3 links inflammation to inhibition of polycomb-mediated gene silencing. Cell, 130(6), 1083–1094. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, & Lanctot KL (2010, March 1). A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry, 67(5), 446–457. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek KA, Dion-Albert L, Lebel M, LeClair K, Labrecque S, Tuck E, Ferrer Perez C, Golden SA, Tamminga C, Turecki G, Mechawar N, Russo SJ, & Menard C (2020, February 11). Molecular adaptations of the blood-brain barrier promote stress resilience vs. depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 117(6), 3326–3336. 10.1073/pnas.1914655117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich M (2019, December). DNA hypermethylation in disease: mechanisms and clinical relevance. Epigenetics, 14(12), 1141–1163. 10.1080/15592294.2019.1638701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott E, Ezra-Nevo G, Regev L, Neufeld-Cohen A, & Chen A (2010, November). Resilience to social stress coincides with functional DNA methylation of the Crf gene in adult mice. Nat Neurosci, 13(11), 1351–1353. 10.1038/nn.2642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvir L, Duclot F, Wang Z, & Kabbaj M (2017, October 08). Epigenetic Regulation of Motivated Behaviors by Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.09.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enache D, Pariante CM, & Mondelli V (2019, October). Markers of central inflammation in major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining cerebrospinal fluid, positron emission tomography and post-mortem brain tissue. Brain Behav Immun, 81, 24–40. 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]