Abstract

Complex brain disorders are highly heritable and arise from a complex polygenic risk architecture. Many disease-associated loci are found in non-coding regions that house regulatory elements. These elements influence the transcription of target genes — many of which demonstrate cell-type specific expression patterns — and thereby affect phenotypically relevant molecular pathways. Thus, cell-type specificity must be considered when prioritizing candidate risk loci, variants, and target genes. This Review discusses the use of high-throughput assays in human-induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSCs)-based neurodevelopmental models to probe genetic risk in a cell-type and patient-specific manner. The application of massively parallel reporter assays (MPRAs) in hiPSCs can characterize the human regulome and test the transcriptional responses of putative regulatory elements. Parallel CRISPR-based screens can further functionally dissect this genetic regulatory architecture. The integration of these emerging technologies could decode genetic risk into medically actionable information, thereby improving genetic diagnosis and identifying novel points of therapeutic intervention.

Introduction

Risk for the development of neuropsychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders is largely polygenic; highly penetrant rare variants underlie disease in only a minority of cases 1-3. With roughly 500 loci identified from PGC Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS; For a glossary of terms used in the Review, see Box 1) across psychiatric disorders already 4-15, making an inference about the biological impact from the growing lists of GWAS variants remains difficult (Table 1)16. The overwhelming majority of identified genetic variants lie within non-coding or unannotated regions of the genome17. Candidate risk loci in non-coding regions are often regulatory elements, such as enhancers and promoters, that influence phenotype through transcriptional modulation18. Enhancers are known to underlie the patterning of gene expression that is important for cell identity, development, aging, and cell-type specific response to the environment. They are putative drivers of disease-related symptoms and represent largely unexplored avenues for therapeutic intervention, but the functional characterization of regulatory elements on a meaningful scale remained inaccessible 18.

Box 1: Glossary.

Epigenome:

The changes in a cell or organism caused by modification of gene expression rather than alteration of DNA sequences directly.

Regulome:

The whole set of regulatory components in a cell, including regulatory elements, genes, mRNAs, proteins, and metabolites

Transcriptome:

the whole set of all RNA molecules in a cell or a population of cells. Depending on the experiment or method, is may refer to only as subset of RNAs, such as mRNAs.

Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS):

Association studies that identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with allele frequencies that systematically vary as a function of phenotypic trait values (i.e. schizophrenia, alcohol use, depression).

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNPs):

DNA variations, or polymorphisms, in a single nucleotide at a specific position in the genome that a present in more than 1% of the population.

Linkage Disequilibrium (LD):

When genetic variants are in linkage disequilibrium, the haplotypes occur at unexpected frequencies indicating there is a non-random association between the alleles.

Haplotype:

a set of polymorphisms or alleles that that are either inherited together at a level greater than what is expected by chance, or that reside on the same chromosome.

Expression Quantitative Trait Locus (eQTL):

SNPs that explain variation in the mRNA expression levels.

Transcriptomic imputation (TI) studies:

Studies that predict trait-associated gene expression by integrating eQTL and GWAS statistics.

Massively Parallel Reporting Assay (MPRA):

A platform allowing for tens of thousands of short DNA sequences to be assayed simultaneously by first synthesizing DNA oligos on an array, integrating them into plasmids and inserting into cells.

Human-Derived Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (hiPSC):

Cells derived from Human skin or blood cells that are reprogrammed back into a pluripotent state, providing an unlimited source of stems cells that may differentiated into any type of human cell needed for therapeutic purposes.

Embryonic Stem Cell (ESC):

Stem cells derived from embryonic tissue. They are pluripotent, meaning they maintain the ability to differentiate into any derivative of the three primary germ layers: endoderm, ectoderm, mesoderm.

RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (RNA-FISH):

An assay to visualize single RNA molecules per individual cells in fresh, frozen, or embedded tissue samples through the application of modified situ hybridization (ISH) methods.

Activity-by-Contact (ABC) Model:

A model based on enhancer activity by enhancer-promoter 3D contacts that can predict enhancer-gene interactions in a given cell type based on the respective chromatin state maps.

Table 1:

Current PGC sample sizes and genetic discoveries across complex brain disorders.

| Disorder | Cases | Loci | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major depressive disorder | 246,363 | 102 | Howard et al. 201912 |

| Alzheimer's disease | 71,880 | 29 | Jansen et al. 20195 |

| Schizophrenia | 67,000 | 270 | Consortium et al. 20206 |

| Anxiety disorders | 51,000 | 3 | Hettema et al. 202011 |

| Bipolar disorder | 29,764 | 64 | Mullins et al 202010 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 32,428 | 3 | Huckins et al. 202015 |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 18,381 | 5 | Grove et al. 20198 |

| Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder | 20,183 | 12 | Demontis et al. 20194 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 2,688 | 0 | Arnold et al. 20187 |

| Eating disorders | 16,992 | 8 | Watson et al. 20199 |

| Tourette syndrome | 4,819 | 1 | Yu et al. 201913 |

| Cross-disorder | 232,964 | 109 | Lee et al. 201916 |

A total of 497 risk loci have been identified by the PGC across these 11 brain disorders.

In this Review, we discuss novel functional genomic strategies that can be applied to conduct large-scale validation and unbiased identification of disease-associated risk loci in a cell-type-specific and genotype-dependent manner. We first introduce human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs; Box 1) — a method already used to model the cell-type specific risk for neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia (SCZ), bipolar disorder (BIP) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) 19,20 — as a unique platform for studying psychiatric disease risk. We then outline advancements in high-throughput techniques that evaluate gene regulatory architecture (mainly Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRAs; Box 1) and multiplexed CRISPR-Cas9-based screens) and consider the novel cell-type-specific applications that are made possible by using hiPSCs. Together, these technologies provide an opportunity for en masse identification and characterization of cell-type and donor-specific regulatory contributions to complex brain disorders (FIG. 1).

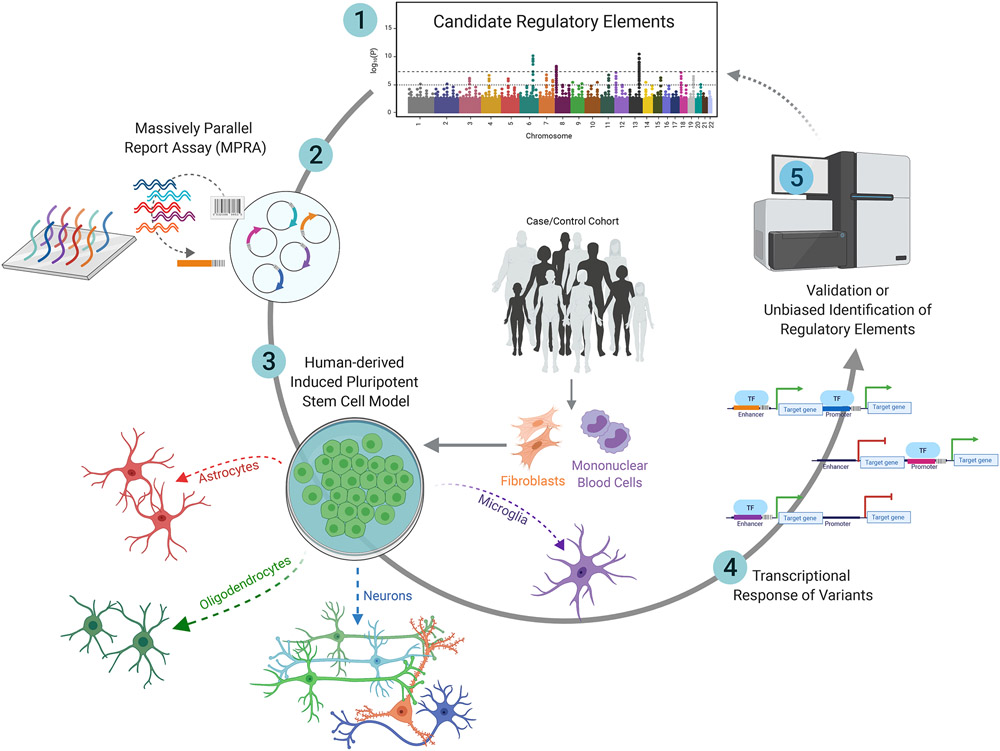

Figure 1: Framework for using massively parallel reporter Assays (MPRAs) to characterize putative regulatory elements with cell-type specificity.

An MPRA library can be designed to include disorder-associated SNPs within putative regulatory elements that have been prioritized through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and Transcriptomic Imputation (TI) analyses. Patient fibroblasts or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) can be induced into a pluripotent state (hiPSCs). With further adaptation, lenti-MPRA libraries could be integrated into hiPSC-derived mature brain cells. By comparing DNA and RNA sequencing of these cells, MPRAs provide a readout of transcriptional differences between the alleles present in patient versus control populations. If transcriptional shifts exist between variants at a specific region, the transcriptional influence of that SNP can be characterized in the context of genetic risk for a disorder.

Advances in computational genetics

Genomic approaches focus on deciphering the biological relevance of genetic variants and predicting their influence on phenotype. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identify genetic variants (single nucleotide polymorphisms; SNPs; Box 1) with allele frequencies that differ between cases and controls or with the presence of a phenotype. However, it remains challenging to resolve the direct biological consequence(s) of disease-associated variants. Computationally derived hypotheses require rigorous validation to confirm the precise targets and predicted biological relevance of potential risk variants. To date, the discovery of putative risk variants and candidate genes far outpaces the capacity for biological validation.

Prioritization of candidate variants

Large-scale GWAS take advantage of linkage disequilibrium (the nonrandom coinheritance of genetic variants; LD; Box 1) to identify the thousands of genetically associated SNPs implicated in polygenic psychiatric disorders 21. Although such studies are able to produce lists of candidate genes, the majority of significant SNPs identified by GWAS for neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric diseases are located in non-coding regions that may act as cis- or trans-acting expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs; Box 1) 22. The list of associated variants identified by GWAS remains long, and thus requires further computational prioritization and development of techniques that are able to functionally validate SNPs en masse.

Two classes of methods exist to infer the impact of GWAS SNPs on higher-order biology. First, single-variant approaches, which largely rely on colocalization of GWAS signals with expression enrichment for cis-eQTLs (e.g. SMR 23, COLOC 24,25, ENLOC 26, pw-gwas 27, PAINTOR 28, FINEMAP 29, MOLOC 30), are robust and statistically rigorous methods. However, single-variant based models do not necessarily recapitulate what we know about eQTL architecture, namely, that a large proportion of genes are under multi-variant regulation 31. A second set of methods, which use joint models to calculate genetically regulated gene expression, takes into account this multi-variant regulation of potential target genes (TWAS 32,33, prediXcan 34,35, FUSION 32, CAMMEL 36, etc, jointly described as transcriptomic imputation (TI; Box 1)). TI studies predict trait-associated gene expression by integrating GWAS summary statistics with eQTLs. This integration of genotypic, transcriptomic, and phenotypic information can help prioritize genes that were indicated in the initial GWAS results for functional follow-up.

Improving the prediction of target genes

Together, such ‘fine-mapping’ studies have significantly advanced the understanding of the relationship between SNPs and transcriptomic responses associated with various traits and diseases, including psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders such as SCZ 23,31,37. Fine-mapping studies have also revealed that SNPs within a non-coding region that are significantly associated with a disorder are not always predictive of expression changes of the most proximal gene. Indeed, SNPs may regulate expression of a more distal gene, and non-coding SNPs may regulate gene expression more than variants within the gene itself 22. For example, the post-mortem transcriptomic analysis of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (Common Mind Consortium, CMC) demonstrated that only ~20% of the identified SCZ risk loci had common variants that could actually explain expression regulation 37. Further fine-mapping identified five loci whose variants modulated the expression of a single gene, effectively funneling a list of hundreds of candidate genes to prioritize those most closely associated with brain-region specific eQTLs 37. Thus, it is critical to consider these points when selecting candidate genes for functional validation.

Identifying risk loci with more-moderate effect sizes requires high-powered GWAS; and linking significant loci with tissue-specific gene expression requires these databases to be widely available. Gene-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project 38 is one such comprehensive transcriptome dataset; it includes DNA and RNA sequencing results from multiple tissues in ~1000 individuals. The GTEx Consortium has characterized gene-expression variability across a thousand individuals, diverse tissues and specific cell types, demonstrating the genetic effect on gene expression throughout the human body 38-40. Integration of transcript-level information from GTEx with gene-level information from large-scale sequencing studies provides insights into the molecular mechanisms through which associated SNPs affect phenotype. PrediXcan is a gene-level prediction method that effectively estimates the underlying genetic determinants of gene expression based on the existing GTEx database 34,41. These predictive models enable gene-based testing for phenotypic associations, so as to explore the role of gene regulation in disease risk in a tissue-specific manner. The utility of these predictive models in providing insight into psychiatric disorders has been validated for autism and schizophrenia 35,41,42. Overall, advances in large-scale genomic and transcriptomic analyses have elucidated novel candidate genes that had initially been missed by traditional GWAS studies, and have revealed tissue-specific elements of disease risk that were previously left unexplored32.

Mapping risk loci to specific brain cell types

Despite these advances, the mechanisms that drive tissue and cell-type specific contributions to complex brain disorders remains an ongoing area of research 43, with much yet to be discovered. Developments in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) provide the opportunity to probe previously unexplored cell-type specific elements of susceptibility to psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders 44,45. Gene-expression profiles from scRNAseq can help to ‘map’ transcriptomic profiles (specific gene-expression patterns) of individual cell types to eQTL analyses of the genetic risk for different disorders 39,46-48. For example, genetic susceptibly for Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) 47,49 and Multiple Sclerosis (MS) 49 is enriched in genes expressed by microglia, genetic risk for SCZ and ASD is shared mainly between interneurons and pyramidal neurons 43,49, and intellectual ability is distributed among a range of cell types 1,49. Genetic risk appears to be uniquely associated with each cell type, which indicates cell-type specific biological roles with respect to the etiology of, for example, SCZ 43. This preponderance of risk in specific cell types hints at a cell-type-of-origin for each disease, but need not reflect the cell types(s) in which aberrant function ultimately leads to clinical pathology, particularly given that late-stage AD, SCZ, and ASD lead to pathological changes in all major brain cell types, albeit to varying degrees 49.

Modeling cell-type specific risk in vitro

With the ever-expanding list of disease-associated candidate loci, variants, and genes, there is a critical need for scalable platforms that can more rapidly map predicted associations while still maintaining biological relevance. Post-mortem analyses can be highly confounded by clinical and biological variables, such as increased inflammatory signaling, medication-induced changes and other pathological changes stemming from long-term disease, and do not allow for experimental manipulation. Avoiding these confounds, donor-specific hiPSC cohorts are an accessible platform for mapping cell-type specific risk, and when combined with genome engineering, they can empirically demonstrate the causal impact of genetic risk variants on a cellular phenotype 50,51 (FIG. 2, 4).

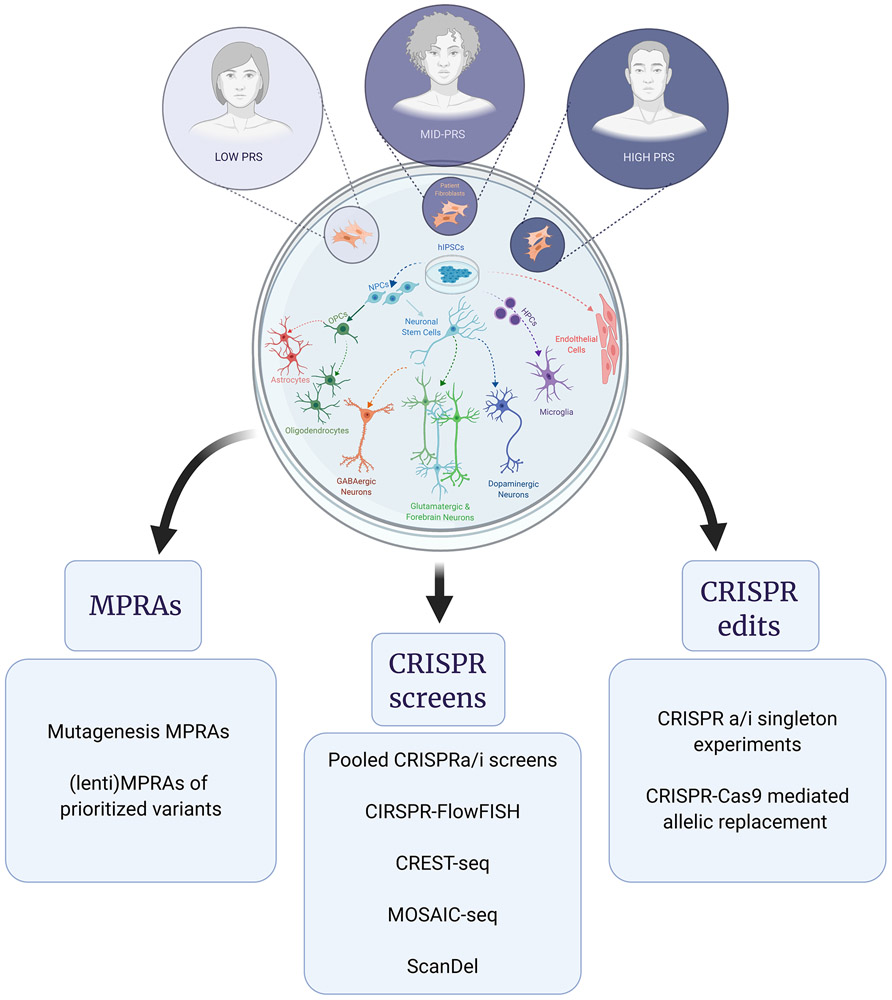

Figure 2: Human-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) provide a cell-type specific and donor-dependent platform for the study of neurogenomics.

By reprogramming patient and control fibroblasts or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), hiPSCs can be stored and accessed as an almost unlimited source for experimental manipulations. Numerous protocols exist for inducing hiPSCs to differentiate into multiple brain cell types, including astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia, GABAergic neurons, glutamatergic neurons, excitatory forebrain neurons, and dopaminergic neurons, as well as brain endothelium. MPRAs, CRISPR-based screens, and CRISPR-based single edits applied in hiPSC models enable cell-type and donor-specific exploration and perturbation of candidate variants and target genes. [CREST-seq: Cis-regulatory element scan by tiling-deletion and sequencing, CRISPR: , FISH: Fluorescent in-situ Hybridization, MPRAs: Massively Parallel Reporter Assays, MOSAIC-seq: MOsaic Single-cell Analysis by Indexed CRISPR Sequencing, ScanDel: A CRISPR-based system that programs thousands of deletions that scan across a targeted region in a tiling fashion.]

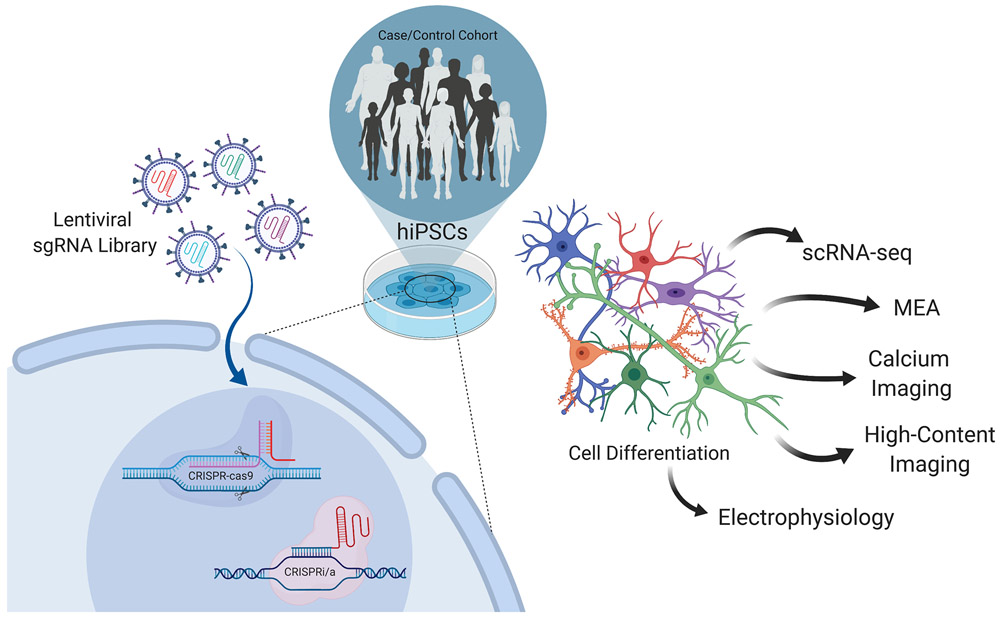

Figure 4: CRISPR-Cas9-based forward genetic screens.

Tens of thousands of sgRNAs activating thousands of DNA-binding factors can be inserted into a lentiviral sgRNA library through viral packaging, each containing a unique barcode signaling its perturbation identity. Populations of donor hiPSC cells are then transfected with the lentiviral sgRNA library and induced to differentiate into the cell type of interest. Once the cells are mature, they can be phenotypically characterized in terms of, for example, electrophysiology evaluated using Micro-electrode Arrays (MEAs) or traditional electrophysiology, neuronal signaling activity through calcium imaging, morphology evaluated by high-content imaging, and gene expression by single-cell RNA seq (scRNA-seq).

Population-scale cell-type specific profiling in hiPSC-derived neurons and glia is now possible 52,53, by applying scRNAseq to pooled populations of hiPSC-derived cells from genotyped donors. A clever example of this, Census-seq, provides a method for simultaneously measuring cell-type specific phenotypes from dozens of donors by quantifying the presence of each donor’s DNA in cell ‘villages’ 54. Such pooled hiPSC approaches will greatly expand the scale to which cell-type and donor-specific transcriptomic profiles can be generated.

Challenges of validating non-coding regions

The continuing discovery of the layered influences on genomic risk, including tissue and cell-type specificity, has motivated the development of more-complex multivariate prediction analyses 45,55. Despite the rapid evolution of computational techniques to predict genomic and environmental contributions to disease, it remains difficult to precisely link loci, SNP variants, and gene expression to phenotypic variability. Many factors hinder the functional validation of promising targets. The function of non-coding regions is difficult to screen, not just because of the exhaustive number of potential variants, but also because single-nucleotide mutations may not lead to a detectable phenotype. SNP location alone is insufficient to identify potential gene targets, as enhancers/promoters can regulate both distal and proximal genes or may ‘skip’ the nearest gene to regulate the next one. Regulatory elements also modulate gene expression in a tissue and cell-type specific manner that may vary based on an individual’s genetic architecture; this requires candidate genes to be both computationally identified and validated in the appropriate context. These barriers make the functional translation from associated SNPs to the cell-type and patient-specific etiology of disease difficult to address 22. Yet with improvements in integrated and parallel screening techniques, and their adaptation for use in hiPSC-based models, researchers will be able to functionally characterize human regulatory sequences en masse (FIG. 1).

Functional validation of regulatory elements

CRISPR-based systems for the independent validation of top eQTLs

The application of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9-based systems in hiPSC-based models provides a platform for the functional validation of candidate GWAS and eQTL loci and the excavation of the genetic and transcriptomic architecture underlying the development of neuropsychiatric disorders 50,56,57. The use of human-derived cell populations enables researchers to sample from rich, heterogenous genetic backgrounds and provides the unique opportunity to model susceptibility for the development of neuropsychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders in a donor-dependent and cell-type specific fashion 19,58. hiPSC methodology can generate diverse brain-cell types with relevant phenotypic measures while accurately capturing a patient’s genetic background and providing a platform for experimental manipulation (FIG. 2, BOX 2). CRISPR-Cas9-based systems provide a toolbox of techniques for exploring function at the level of the genome, epigenome, and regulome. Many of these systems have successfully been applied in hiPSCs to probe the functional effects of common and rare variants in human-derived neurons 57,59. The repertoire and applicability of CRISPR-Cas9-based systems for genomic and epigenomic evaluation is expanding rapidly.

Box 2: Overview of brain-cell types accessible through hiPSC-based methods.

Patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC)103, skin or dura fibroblasts 104,105 can be used to derive hiPSCs, providing an accessible and inexhaustible source of stem cells to model risk predisposition in a donor-dependent and cell-type specific manner (FIG. 1)19. In the context of the brain, current protocols are capable of differentiating hiPSCs into multiple neuronal subtypes (neural progenitor cells (NPCs), forebrain interneurons 88, and glutamatergic 106, midbrain dopaminergic 107, GABAergic neurons 108,109, and serotonergic neurons 110), as well as neuro-endothelial (glial) cells (astrocytes 111, oligodendrocytes 112), brain microvascular endothelial cells (encompassing the blood-brain barrier 113), and hematopoietic cells (microglia 103). CRISPR-based methods can also be used to induce differentiation. A lenti-virus CRISPRa technique has been used to induce expression of transcription factors to drive the differentiation of GABAergic neurons from hiPSCs 108. Three-dimensional co-culturing techniques 114,115 and development of brain organoids 89 can model complex interactions among cell types. Importantly, patient-derived hiPSC neurons can produce cellular phenotypes 69 and transcriptomic signatures that are concordant with post-mortem data 116. While high-throughput sequencing methods can probe the molecular effects of risk variants and candidate gene interactions, methods that assess cellular phenotypes in vitro provide an understanding of how these molecular disruptions influence brain development and function. For example, electrophysiology can assess the electrical properties of single cells, and micro-electrode arrays (MEA) measurements assess firing events, burst patterns, and the activity development of iPSC-derived networks 69,117. Advances in high-content imaging enable the assessment of other phenotypic aspects such as neurite outgrowth, synaptic development, and apoptosis, and calcium imaging provides measurement of cellular differentiation and activity 68. A remaining challenge for iPSC-based models is to establish how cell-type specific phenotypes in vitro relate to disorder-associated phenotypes in the adult patient brain.

CRISPR-Cas9-mediated point mutations by base editing or prime editing makes it feasible to induce allelic conversion at specific (rare or common) loci in hiPSCs derived from case/control cohorts 60,61. CRISPR-dCas9 enables one to fuse transcriptional repressors such as KRAB (CRISPRi) 62,63 or activators such as p300 64, VP1665 and VPR 66 (CRISPRa) to a catalytically inactive (dead-Cas9, dCas9), resulting in down-regulation or up-regulation of transcriptional activity at candidate risk eQTLs, respectively 67. CRISPRa/i facilitates high-throughput functional assays in hiPSC-derived brain-cell types manipulate gene expression without completely knocking in or out a gene, thereby better recapitulating the influence a disease-associated SNP may have on transcription 68. CRISPRa/i has been successfully used to endogenously perturb the expression of candidate genes for complex brain disorders in populations of hiPSC-derived NPCs, neurons, and astrocytes 50. Both perturbation techniques have also been employed for functional validation of candidate genes prioritized by expression–-trait association studies.

For example, we recently applied CRISPR-mediated engineering to probe the biological function of top-ranked SCZ SNPs and genes in isogenic hiPSC-derived neurons, resolving pre- and post-synaptic neuronal deficits, recapitulating genotype-dependent gene expression profiles and identifying convergence and additive relationships between SCZ genes 69. Altogether, work by ourselves and others 50,59,68-73 has established that the integration of CRISPR-based genome engineering with patient-specific hiPSCs provides an experimental platform for determining the phenotypic consequences of the cell-type-specific perturbation of computationally prioritized risk variants and genes.

Massively Parallel Reporter Assays to evaluate regulatory elements en masse

CRISPR-editing can link GWAS-associated variants to genes to phenotypes, but only for a handful of top predicted SNPs. To evaluate how accurate our computational strategies truly are, the association between many variants and target gene(s) needs to be empirically tested in an unbiased manner. Regulatory elements, potentially the major driver of psychiatric disease risk, are an untapped source for novel therapeutic development; this again highlights the need for functional assays that can both validate associations between risk variants and candidate genes and characterize their regulation of both proximal and distal target genes that may be missed by predictive models.

Specifically, non-coding or exonic variants, which are highly enriched in genome-wide and expression–trait association studies, are frequently located within predicted regulatory elements. Causal eQTL variants are frequently enriched in DNase-I hypersensitive sites and in regulatory regions such as active promoters, enhancers, and TF binding sites 22,45,74. Enhancers temporally and spatially regulate the level of expression of their target genes in a tissue and cell-type specific manner 47. However, the precise gene targets of enhancers and other regulatory elements remains an open area of investigation, as does their functional contribution to psychiatric phenotypes.

While there are genomic technologies that can rapidly detect random nucleotide variation within presumed regulatory regions, assays that provide large-scale characterization of the transcriptional shifts produced by these variations have only recently been developed. One such development, ‘Gigantic’ Parallel Reporter Assay (GPRA) expanded on past experiments using random DNA — such as the systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) — to test regulatory sequences at a large scale 75. GPRAs can measure expression levels associated with each of hundreds of millions of random DNA sequences per experiment. In a study performed in yeast, this method was able to generate large-scale expression profiles that were subsequently applied to develop genome-wide models of cis-regulatory logic76-78. Similar high-throughput reporter assays, generally called Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRAs, FIG. 3, Table 2), enable the en masse screening of millions of nucleotide variants within thousands of sequences for enhancer or promoter activity 75,79,80. In addition to identifying non-coding regulatory regions, MPRAs have been employed to identify exonic enhancers 76 and enhancer/promoter interactions 81,82. First developed in vitro with synthetic promoters, such high-throughput screens for regulatory-element activity have only recently been applied in mammalian brain cells 83,84.

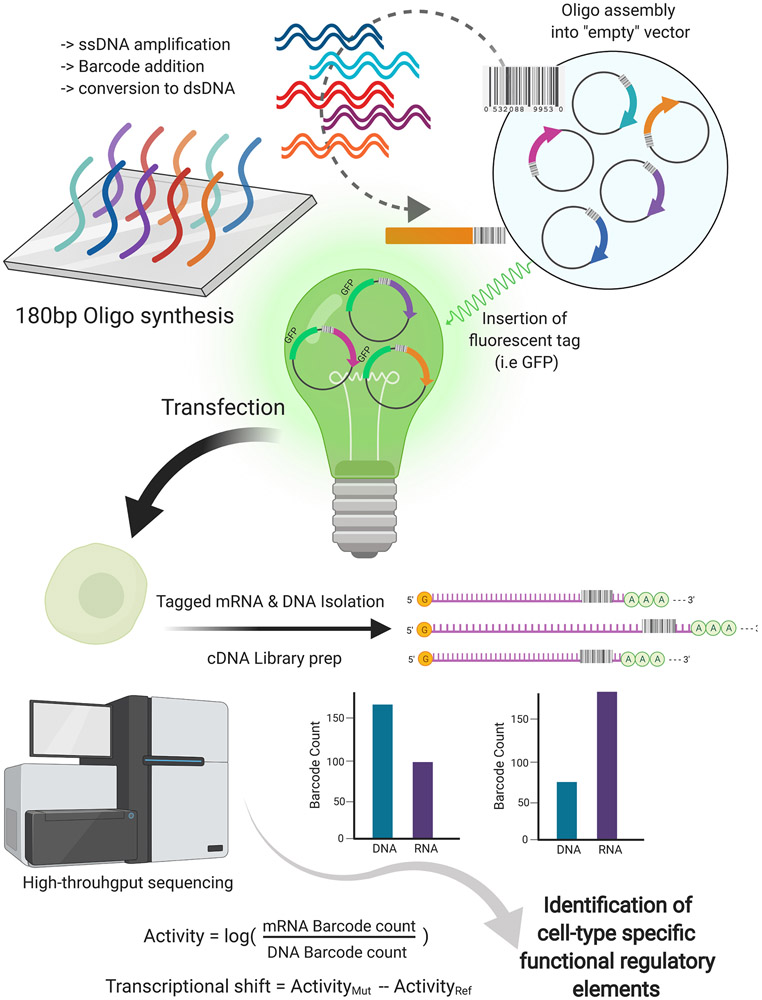

Figure 3: Outline of the Massively Parallel Reporter Assay (MPRA) workflow.

Short 180bp oligos are synthesized by cleavage of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) from the array. Through emulsion PCR, the 180bp ssDNA oligomers are amplified, barcoded, and converted to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). dsDNA oligomers are assembled into an empty report vector, creating an MPRA library. The plasmids are fluorescently tagged by the insertion of a GFP open reading frame and minimal promoter for transfection into the desired cell type. RNA is isolated from transfected cells and the barcoded mRNAs are captured and sequenced. Barcode counts are compared to the count estimates from the sequencing of the plasmid library or sequencing of DNA captured simultaneously with RNA to measure relative expression. Sequencing results from MPRAs can be integrated into sequencing information from other techniques, such as ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq, and Capture Hi-C. Application of massively parallel and combinatorial methods in hiPSC models enables the cell-type specific identification of novel regulatory elements as well as the validation of unconfirmed candidates. [ATAC-seq: Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing Capture Hi-C: A chromatin conformation capture technique that is target to specific loci; and ChIP-seq: Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing]

Table 2:

A detailed overview of select MPRA and CRISPR-based studies discussed in this review.

| Method- Family |

Method | Parallel Methods |

Variant Selection Criteria |

Targets | Context | Cell Lines |

Cell Type | Application | Limitations | Secondary Validation |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPRAs | Mutagenesis | NA | Random nucleotide substitutions in enhancers at a rate of 10% per position. | 27000 | Episomal | HEK293T | human kidney | Direct comparison of hundreds of thousands of putative regulatory sequences in a single cell culture. | Depends on (1) careful design of the sequence library, (2) minimization of artifacts during amplification and cloning, (3) high transfection efficiency, (4) and necessary power to detect transcriptional shifts. | NA | Melnikov et al 2012 |

| Mutagenesis | NA | Tested 2104 WT sequences & 3314 engineered variants with motif disruptions. | >5,000 | Episomal | HepG2, K562 | Carcinoma LL | (1) Manipulations of a large number of enhancers and disruptions for individual cis-regulatory motifs. (2) Well-suited to systematic testing of pairs or sets of elements, and de novo enhancer design. | (1) Unable to determine relative contribution of chromatin vs. primary sequence information (2) focused on distal enhancers at least 2 kb from any annotated TSS for the SV40 promoter region only | Luciferase validation | Kheradpour et al 2013, | |

| Mutagenesis | NA | 20 promoter/enhancers (600bp loci) | 30,000 SNPs/ | Episomal | HepG2 | Liver | (1) Scaled saturation mutagenesis to measure regulatory consequences of tens-of-thousands of regulatory elements (2) Longer sequences than are typical for MPRAs, up to 600 bp to provide more context. | (1) Limited with respect to context, both cis and trans, (2) reproducibility of measurements for elements with lower basal activity | RNAi | Kircher et al 2019, | |

| GWAS-based MPRA | NA | Selection of variants in high LD with 75 GWAS hits from red blood cell (RBC) traits | 2,756 SNPs | Episomal | K562 | Erythriod | Identified 32 functional variants representing 23 of the original 75 GWAS hits | (1) Not configured to detect functional variants in haplotypes that may be jointly causal and fall within more than one regulatory element. (2) Primarily as a screen to reduce set of leads. | Cas9 genome editing | Ulirsch et al 2016, | |

| GWAS-based MPRA | NA | 1,049 SZ and 30 AD variants in high LD with lead SNPs from 64 and 9 GWSIG loci respectively | 1228 SNPs | Episomal | K562, SK-SY5Y | LCLs | Identified 148 variants showing allelic differences in K562 and 53 in SK-SY5Y cells | (1) High potential for false negatives due to lack of native context. (2) False positives possible if regulatory effect on the reporter gene comes from other parts of the construct or if variant resides in closed chromatin. | NA | Myint, et al., 2020, | |

| eQTL-based MPRA | NA | Candidate eQTLs from RNAseq dataset of lymphoblastoid LCLs | 3,642 cis-eQTLs | Episomal | HepG2, NA12878NA19239 | Liver, LCLs | (1) Identified 842 eQTLs with a significant transcriptional shift between alleles. (2) Provides a discovery tool for linking a genetic locus to a phenotype. | (1) Cannot test for causality. (2) Endogenously silenced sequences explain a proportion of reported active sequences. (3) Positive predictive value of 34%–68%. | CRISPR-mediaterd allelic rep-placement | Tewhey et al 2016, | |

| LentiMPRA | RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, H3K27ac ChIP-seq | Identified by RNA-seq/ATAC/H3K27Ac/ChIP-seq bease on genes involved in neural differentiation | ~ 2300 | Chromosomally Integrated | HepG2, hESC | liver, hNPCs | Functional characterization of >1,500 temporal enhancers (1) lentiMPRA used in an episomal or integrated context (2) can be used in a wide variety of cell types (3) numerous barcodes per variant; and (4) extensive predictive modeling. | (1) Even as an integrated reporter assays, each tested element is removed from its native sequence location and epigenetic context | CRISPRi | Inoue et al 2017, 2019 | |

| SuRE MPRA | Dnase-seq, ATAC-seq, H3K27ac | Randomly generated two SuRE libraries of ~300 million random fragment-barcode pairs | 5.9 million SNPs | Episomal | K563, HepG2 | Eryhriod, Liver | (1) Increased traditional MPRA scale by >100 folde. (2) Provides a resource to help identify causal SNPs among candidates generated by GWAS and eQTL studies | (1) Random SNPs assayed outside of endogenous context (3) Power to detect transcriptional shift may be limited by number of barcodes per fragment | CRIPSR/ Cas9 SNP editing |

van Arensbergen et al. 2019 | |

| two-Stage MPRA screen | NA | Random genome-wide DNA fragments | 32,776 substitutions | Episomal | hESC | hNSCs | (1) MPRA in human neural stem cells. (2) Identified 532 HARs and HGEs with human-specific changes in enhancer activity in human neural stem cells. | (1) Effects were modest and lacked genomic context. | CRISPRi enhancer validation | Uebbing et al. 2020 | |

| CRISPR | Multiplexed CRISPRi, eQTL-inspired framework | scRNA-seq | Top 5,000 intergenic open chromatin regions in K562s | 5,920 | Endogenous | K562 | LCLs | Identified 664 cis enhancer-gene pairs enriched for specific transcription factors, non- housekeeping status, and genomic and 3D conformational proximity to their target genes | (1) Not all enhancers susceptible to perturbation; (2) variable degree of gRNAs targeting ability; (3) enhancers may be required for initial establishment rather than maintenance. (4) not a comprehensive survey of noncoding landscape | CRISPRi singleton experiments | Gasperini et al. 2019 |

| Genome-Wide CRISPRa screen | NA | Library targeting all computationally predicted TFs a& other DNA-binding factors (TRANSFAC) | 2,428 | Endogenous | CamES | Neuron | (1) Systematically identify transcription factors that efficiently promote neuronal fate from ESCs. (2) Generated a quantitative GI map for the neuronal fate decision by pairwise activation of core neuronal-inducing factors. | (1) Scalability of the CRIPRa screens | Flow cytometry and cDNA expression. | Liu et al 2019 | |

| CRISPRi-FlowFISH | ChIP-seq, Hi-C | Selected all DNase I hypersensitive (DHS) elements in K562 cells within 450 kb of 30 genes in five genomic regions | 4,662 | Hi-C and ChIP-seq | K562 | LCLs | (1) Tests noncoding regulatory elements by mapping and modeling promoter–promoter regulation, functions of CTCF sites, and combinatorial effects. (2) Potential application to any gene. (3) Method uses endogenous genes allowing candidate target genes to be identified. | (1) Does not profile effects of intronic enhancers; (2) performance may decrease by weakly expressed genes | ABC prediction model | Fulco et al. 2019 | |

| Pooled CRISPR screens | Parallel screens of enhancers, genes, & genomic background | Identified from H3K27sc datasets from human cortex, developing cortex, limb, embryonic stem cells, and adult tissues | 10674 genes & 2,227 enhancers | Endogenous | H9 hESCs | hNSCs | (1) Probed gene disruptions affecting proliferation in model of human corticogenisis and their associations with neurodevelopmental disease | (1) sgRNA-Cas9 screening using Cas9 original method resulting in insertions, deletions, and substitutions. influencing the DNA directly versus inhibiting or activating expression or enhancer activity. | Confirm enhancer-gene interaction using Hi-C data | Geller et al. 2019 | |

| Pooled genome- wide & CRISPRi screens | CROP-seq, longitudinal imagining | CRISPRi v2 H1 library with top 5 sgRNAs per gene (Horlbeck et al., 2016) | 18,905 genes | Endogenous | hiPSCs | Neuron | (1) Identified distinct neuronal roles for ubiquitous genes; (2) an inducible and reversible method enabling the time-resolved dissection of human gene function; (3) perturbs gene function via partial knockdown; (4) longitudinal imaging provides timeline of toxicity and reveals gene-specific temporal patterns. | (1) Scalability limited by us of lentivirus, synthetic sgRNAs in arrayed CRISPRi screens would increase scalability; (2) False-positive phenotypes possible due to interference with the differentiation process. | Secondary CRISPR screens, CROP-seq | Tian et al 2019 | |

| Pooled CRISPRa/i screen | CROP-seq | (1) Genome-wide survival-based screen. (2) Secondary CRISPR screens. (3) Crop-seq | Genome-wide and targeted screens > 1000 genes | Endogenous | hiPSCs | Neuron | (1) The first genome-wide CRISPRa/i screens in human neurons (2) Uncovered neuron-response pathways to chronic oxidative stress implicated in neurodegenerative disease (3) Established CRISPRbrain resource to compare gene function across human cell types | (1) CRISPR a/i screening protocol may confound results related to oxidative stress as gRNA integration could affect cellular stress | Lipomics in KO neurons | Tian et al. 2020 |

CC = cervical cancer cells, hESCs = Human Embryonic Stem Cells, HiPSCs = Human-induced Pluripotent Stem Cells, LCL = Lymphoblastoid cell lines, ML = myelogenous leukemia cells, hNSCs – Neural Stem cells, NPCs = Neuronal Progenitor Cells, CREST-seq= “cis-regulatory element scan by tiling-deletion and sequencing”

Interrogating prioritized regulatory regions with cell-type specificity

MPRA strategies can evaluate putative causal eQTLs that overlap with significant GWAS loci for complex brain disorders85,86. A study that tested 342,373 sequences (including multiple barcodes per variant), encompassing 3,642 SCZ and AD associated cis-eQTLs and controls regions, identified 843 variants with transcriptional shifts notable between mutant alleles, 53 of which were well-annotated risk variants for multiple traits 85. In a follow-up for a single eQTL, the MPRA findings were validated by CRISPR/Cas9-guided allelic replacement. This demonstrates the potential for MPRAs as tools to evaluate the contributions of regulatory regions to developmental risk for complex disorders like SCZ and AD. However, it should be noted that these experiments were performed in two cancer cell lines; adapting MPRAs for use in brain cells, especially those derived from cases and controls, will be critical towards understanding cell-type-specific models of regulatory logic in contexts of greater clinical relevance.

A study aiming to decipher the changes in the regulome that occur during neuronal maturation used lenti-MPRA to test the activity of 2,464 candidate regulatory sequences across seven time points during the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) to neural cells 83, indicating the potential for MPRAs to be adapted for use in neuronal cells. The successful use of MPRAs and parallel high-throughput sequencing techniques in hESCs-derived neural cells and neural precursor cells 84,87 is a promising step towards their wider application in hESC- and hiPSC- derived cell populations. Particularly exciting is the potential for development of massively parallel sequencing protocols in patient-derived hiPSC-based models that would enable cell-type specific and donor-dependent identification of regulatory elements in complex brain disorders. Similarly, since hiPSC-derived neurons are already used to model human cortical development 84,87-89, applying these techniques in temporal analyses of hiPSC-derived cells may elucidate early developmental factors involved in the etiology of psychiatric disorders 90.

Integrated approaches to account for endogenous context

While MPRAs provide a momentous expansion in our ability to evaluate regulatory activity, the context of endogenous location — such as 3D chromatin structure, transcription associated domains (TADs) and other regulatory sites — is lost in this approach. By integrating MPRA, ChIP-seq, RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and HI-C data, regulatory elements can be identified in their endogenous context. A recent study illustrated the power of integrating approaches when it identified substantial (26-29%) overlap between allele-specific open chromatin (ASoC) variants and the non-neuronal MPRA SCZ and AD SNP dataset discussed above [see85]73. Using hiPSCs of 20 individuals with heterozygous GWAS SNPs at between 70 to 108 SCZ risk loci, ATAC-seq and RNA-seq was performed in NPCs, glutamatergic neurons, γ-aminobutyric acid–releasing (GABAergic) neurons, and dopaminergic neurons to map cell-type specific ASoC variants87. Future MPRA studies probing SCZ candidate SNPs in hiPSC derived brain cell-types could leverage this extensive dataset, and other existing datasets, to provide vital endogenous context.

An additional limitation of MPRA strategies is that most MPRAs contain DNA fragments between 145-170 bp in length, which may not encompass the boundaries of putative regulatory elements, i.e. the length of the sequence flanking the SNP. This technical constraint in MPRA design has been somewhat addressed in recent methodological improvements 79,91,92. For example, a novel tiling-based MPRA approach called Systematic High-resolution Activation and Repression Profiling with Reporter-tiling using MPRA (Sharpr-MPRA) interrogated 4.6 million nucleotides across 15,000 regulatory regions prioritized from genome-wide epigenomic maps 92 and demonstrated that endogenous chromatin states and DNA accessibility predict regulatory function. By designing hundreds of oligos, each differing by shifting a 5-30 bp window, to ‘tile’ around each regulatory element the researchers were able to resolve a longer portion of the sequences flanking these regions.

To summarize, MPRAs provide the opportunity to validate the influence of variants in regulatory elements on gene regulation, but they fail to recapitulate structural context or the full size of regulatory elements — two aspects that demand thoughtful consideration given the importance of the epigenetic landscape and appropriate boundaries to the activity of regulatory regions. From a reverse-genetics perspective, the application of massively parallel, combinatorial techniques that integrate MPRA data with other sequencing techniques [as in 73,83,92] are crucial to validating the contributions of regulatory sequences in the context of cell-specific genetic architecture. The generation of detailed cell-type specific datasets in neuronal sub-populations, will be vital to contextualizing MPRA outputs.

Due to the overwhelming number of currently unannotated non-coding regions of the genome, there is an equal need for unbiased discovery and characterization of regulatory elements. Forward-genetic MPRA screens for enhancer activity of millions of sequences have the potential to provide insight into cell-type specific genetic architecture underlying disease. When integrated with other high-throughput sequencing datasets, MPRA data can identify novel genetic interactions and give an indication of their biological relevance. However, MPRAs are unable to align regulatory elements in the context of endogenous loci and, similar to putative loci identified by computational methods outlined previously, MPRA-derived hypotheses and models of cis-regulatory logic require rigorous functional validation.

CRISPR perturbation screens for further interrogation of enhancer-gene interactions

Regulation of gene expression is complex; it is orchestrated by an interplay of elements such as promoter/enhancer sequences, transcription factors, epigenetic markers, and chromatin accessibility. Interactions between regulatory elements and targets depend not only on the length of the linear sequence separating the variant from the gene and on the regulatory activity of a genetic variant, but also on the epigenetic context in which the risk variant and target genes are found. For example, histone modifications, chromatic looping, and heterochromatin status all influence the extent to which regulatory variants impact their target genes. The activity of regulatory elements identified by MPRA datasets, which are performed in artificial reporter vectors, must therefore be further validated at endogenous loci. CRISPR-based screens are increasingly applied to query variant–gene interactions in the context of the broader genomic architecture and can help validate a subset of interactions identified by MPRAs.

While CRISPR/Cas9-based studies have successfully validated candidate eQTLs in a genome-specific context 50,61,69,93-95, their scalability is limited. Until recently, such studies focused on perturbing only the top few candidate genes. However, the scalability of reverse genetic screens using CRIPSR perturbation is rapidly increasing. Multiplex eQTL-inspired frameworks leverage CRISPR systems to map enhancer–gene pairs 46,48,96-98. This multiplex enhancer–gene pair screening technique introduces random combinations of CRISPRa/i perturbations to each of many isogenic cells, thus noticeably increasing the screening power. When this screening is followed by single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), an association framework analogous to that used to identify conventional eQTLs can then map both cis and trans effects on gene expression 68,81,93,95,99. This approach was validated in a human chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line (K562) using CRISPRi, and was scaled to target 5,779 candidate enhancers with roughly 28 CRISPR-mediated perturbations per single-cell transcriptome; it identified 664 cis-human enhancer–gene pairs, including 24 candidate enhancers paired with multiple known target genes48. Aiming to specifically predict enhancer–gene interactions in a cell-type specific manner, another study combined CRISPRi, RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (RNA-FISH; Box 1), and flow cytometry to test more than 3,500 potential enhancer–gene connection for 30 genes of interest in K562 cells 81. Here, an activity-by-contact (ABC; Box 1) model coined CRISPRi-FlowFISH predicted complex enhancer–gene connections across thousands of non-coding candidate variants.

CRISPR interference and activation platforms have also been adapted for the use of genome-wide application68,99. For example, pooled CRISPRa screens identified novel and established transcription factors involved in driving mouse epiblast and embryonic stem cell reprogramming and neuronal fate 100,101. CRISPR perturbation platforms have additionally been applied in human cancer cell lines 46,81, human ESC-derived neuronal progenitor cells (NPCs) 83, and hiPSC-derived neurons 68,99. These approaches further advance the scalability of CRISPR-based screens for the functional validation of regulatory elements in disease (FIG. 4).

To summarize, the development of multiplexed enhancer–gene pair screens make it feasible to functionally characterize the daunting number of candidate regulatory elements, since such screens have been reported to target roughly 6,000 candidate enhancers and evaluate their interaction with more than 10,000 expressed genes 46. Continued advancements in massively parallel high-throughput enhancer–gene mapping will increase our screening power further, providing the ability to catalogue novel enhancer–gene interactions with cell-type specificity. The translation of MPRAs and multiplexed CRISPR-based screening techniques to hiPSC-based models provides a platform for both a priori identification and characterization of previously unknown regulatory sequences en masse. New reverse-genetic applications achieve validation of thousands of candidate regulatory elements contributing to disease susceptibility in a donor-dependent and cell-type specific manner.

Implications, impediments, and improvements

While massively parallel high-throughput screens represent a notable advancement in mapping and validating enhancer-gene interactions, these approaches are not without their weaknesses. A full appreciation for the genotype- and cell-type-dependent contributions of the regulome to disease requires the acknowledgment of limitations in the approaches attempting to characterize them.

A major caveat of MPRA data is the loss of information regarding endogenous location. As discussed above, one way to address this is to merge parallel high-throughput techniques (such as described above for MPRAs, CRISPR screens, ATAC-seq, scRNA-seq, etc.). However, in the general context of large-scale parallel approaches, challenges are likely to arise from disagreement among heterogenous classes of data 96. But while contradicting findings may muddy our functional understanding of some variants, convergence of results from heterogenous datasets will bolster confidence for others. Additionally, the relatively short DNA fragments flanking prioritized variants for GWAS and eQTL-based MPRAs may omit crucial portions of larger regulatory regions. Adaptations to MPRA designs have begun to address this limitation 79,91,92.

When considering the challenges of characterizing the disease-related influences of regulatory elements, it is important to acknowledge that these approaches largely associate enhancer activity with the modulation of net gene transcription. Regulatory elements may in fact have a more nuanced biological function that is overlooked by current screening techniques 96, which may also vary in a tissue or cell-type dependent manner, with further implications for disease risk. Although briefly touched upon here, the limitations of these approaches and the impediments facing their progression are more comprehensively addressed in recent reviews 17,96,102.

Conclusion

While computational genomics and high-throughput sequencing of the transcriptome and epigenome has rapidly expanded our capability to identify regulatory elements, the sheer number of these regions in the human genome makes it difficult to functionally characterize and validate all predicted enhancer–gene connections. Recently, the successful application of massively parallel techniques (through harnessing the power of MPRAs, multiplexed CRISPR-based screens, and high-throughput sequencing 46,75,81,83,95) has expanded the realm of possibility for both mapping and predicting the human ‘regulome’.

Already applied in human cancer cell lines 46,81, human ESC-derived neural cells 83, and human neural stem and progenitor cells 84,87 the application of massively parallel techniques in patient-specific hiPSC-derived populations of neurons, glia, and brain endothelium will enable cell-type specific and donor-dependent identification of enhancer/promoter interactions and gene connections implicated in complex brain disorders. Combining computational genomics with high-throughput sequencing, MPRAs, and CRISPR-based screens could, when applied to hiPSC-based neuronal models and brain organoids, provide a cell-type specific catalogue of human regulatory architecture underlying neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partially supported by National Institute of Health (NIH) grants R56 MH101454 (K.J.B), R01 MH106056 (K.J.B.), R01 MH109897 (K.J.B.) and R01 MH118278 (LMH).

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sims R et al. Rare coding variants in PLCG2, ABI3, and TREM2 implicate microglial-mediated innate immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet 49, 1373–1384 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curran S, Ahn JW, Grayton H, Collier DA & Ogilvie CM NRXN1 deletions identified by array comparative genome hybridisation in a clinical case series – further understanding of the relevance of NRXN1 to neurodevelopmental disorders. J. Mol. Psychiatry 1, 4 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betancur C & Buxbaum JD SHANK3 haploinsufficiency: A ‘common’ but underdiagnosed highly penetrant monogenic cause of autism spectrum disorders. Mol. Autism 4, 17 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demontis D et al. Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat. Genet 51, 63–75 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansen IE et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer’s disease risk. Nat. Genet 51, 404–413 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Consortium, S. W. G. of the P. G., Ripke S, Walters JT & O’Donovan MC Mapping genomic loci prioritises genes and implicates synaptic biology in schizophrenia. medRxiv 2020.09.12.20192922 (2020) doi: 10.1101/2020.09.12.20192922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnold PD et al. Revealing the complex genetic architecture of obsessive-compulsive disorder using meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 1181–1188 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grove J et al. Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Genet 51, 431–444 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson HJ et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight risk loci and implicates metabo-psychiatric origins for anorexia nervosa. Nat. Genet 51, 1207–1214 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullins N et al. Genome-wide association study of over 40,000 bipolar disorder cases provides novel biological insights. Nathalie Brunkhorst-Kanaan 17, 202 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hettema JM et al. Genome-wide association study of shared liability to anxiety disorders in Army STARRS. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet 183, 197–207 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howard DM et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat. Neurosci 22, 343–352 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu D et al. Interrogating the genetic determinants of Tourette’s syndrome and other tiC disorders through genome-wide association studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 176, 217–227 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duncan LE et al. Largest GWAS of PTSD (N=20 070) yields genetic overlap with schizophrenia and sex differences in heritability. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 666–673 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huckins LM et al. Analysis of Genetically Regulated Gene Expression Identifies a Prefrontal PTSD Gene, SNRNP35, Specific to Military Cohorts. (2020) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee PH et al. Genomic Relationships, Novel Loci, and Pleiotropic Mechanisms across Eight Psychiatric Disorders. Cell 179, 1469–1482.e11 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montalbano A, Canver MC & Sanjana NE High-Throughput Approaches to Pinpoint Function within the Noncoding Genome. Molecular Cell vol. 68 44–59 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards SL, Beesley J, French JD & Dunning M Beyond GWASs: Illuminating the dark road from association to function. American Journal of Human Genetics vol. 93 779–797 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernando MB, Ahfeldt T, Brennand KJ, Sinai M & York N Modeling the complex genetic architectures of brain disease. Nat. Genet 1–7 (2020) doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0596-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Hugte E & Nadif Kasri N Modeling Psychiatric Diseases with Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. in Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology vol. 1192 297–312 (Springer New York LLC, 2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Visscher PM, Brown MA, McCarthy MI & Yang J Five years of GWAS discovery. American Journal of Human Genetics vol. 90 7–24 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albert FW & Kruglyak L The role of regulatory variation in complex traits and disease. Nature Reviews Genetics vol. 16 197–212 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu Z et al. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat. Genet 48, 481–487 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallace C Statistical Testing of Shared Genetic Control for Potentially Related Traits. Genet. Epidemiol 37, 802–813 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plagnol V, Smyth DJ, Todd JA & Clayton DG Statistical independence of the colocalized association signals for type 1 diabetes and RPS26 gene expression on chromosome 12q13. Biostatistics 10, 327–334 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen X, Pique-Regi R & Luca F Integrating molecular QTL data into genome-wide genetic association analysis: Probabilistic assessment of enrichment and colocalization. PLOS Genet. 13, e1006646 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pickrell JK et al. Detection and interpretation of shared genetic influences on 42 human traits. Nat. Genet 48, 709–717 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kichaev G et al. Integrating Functional Data to Prioritize Causal Variants in Statistical Fine-Mapping Studies. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004722 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benner C et al. FINEMAP: Efficient variable selection using summary data from genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 32, 1493–1501 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giambartolomei C et al. A Bayesian Framework for Multiple Trait Colocalization from Summary Association Statistics. A Bayesian Framew. Mult. Trait Coloca. from Summ. Assoc. Stat 155481 (2017) doi: 10.1101/155481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dobbyn A et al. Landscape of Conditional eQTL in Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex and Co-localization with Schizophrenia GWAS. Am. J. Hum. Genet 102, 1169–1184 (2018).Demonstrates the ability of colocalization analyses to identify candidate SNPs that are predictive of disease-associated gene expression in a tissue-specific manner. Identification of the FURIN SNP by this method was functionally validated in REF. 69.

- 32.Gusev A et al. Integrative approaches for large-scale transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet 48, 245–252 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wainberg M et al. Opportunities and challenges for transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet 51, 592–599 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gamazon ER et al. A gene-based association method for mapping traits using reference transcriptome data. Nat. Genet 47, 1091–1098 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barbeira A et al. MetaXcan: Summary Statistics Based Gene-Level Association Method Infers Accurate PrediXcan Results. bioRxiv 045260 (2016) doi: 10.1101/045260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park Y et al. A Bayesian approach to mediation analysis predicts 206 causal target genes in Alzheimer’s disease. bioRxiv 219428 (2017) doi: 10.1101/219428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fromer M et al. Gene Expression Elucidates Functional Impact of Polygenic Risk for Schizophrenia. bioRxiv 052209 (2016) doi: 10.1101/052209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Consortium Gte. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Supplementary materials. Science (80-. ). 61–73 (2020) doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-1842-9_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim-Hellmuth S et al. Cell type–specific genetic regulation of gene expression across human tissues. Science (80-. ). 369, eaaz8528 (2020).One of the most recent publications from the GTEx consortium, describes their efforts to map QTLs to human tissues. More importantly, it reports the use of 43 pairs of tissues and cell types to identify cell-type specific genetic regulation of gene expression.

- 40.Donovan MKR, D’Antonio-Chronowska A, D’Antonio M & Frazer KA Cellular deconvolution of GTEx tissues powers discovery of disease and cell-type associated regulatory variants. Nat. Commun 11, 955 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barbeira AN et al. Exploring the phenotypic consequences of tissue specific gene expression variation inferred from GWAS summary statistics. Nat. Commun 9, 1–20 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huckins LM et al. Gene expression imputation across multiple brain regions provides insights into schizophrenia risk. Nat. Genet 51, 659–674 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skene NG et al. Genetic identification of brain cell types underlying schizophrenia. Nat. Genet 50, 825–833 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sey NYA, Fauni H, Ma W & Won H Connecting gene regulatory relationships to neurobiological mechanisms of brain disorders. bioRxiv 681353 (2019) doi: 10.1101/681353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gusev A et al. Partitioning heritability of regulatory and cell-type-specific variants across 11 common diseases. Am. J. Hum. Genet 95, 535–552 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gasperini M et al. A Genome-wide Framework for Mapping Gene Regulation via Cellular Genetic Screens. Cell 176, 377–390.e19 (2019).A prime example of a CRISPR perturbation screen design based on eQTLs overlaping with GWAS loci. A framework was later described in depth as crispQTL by the same group.

- 47.Nott A et al. Brain cell type–specific enhancer–promoter interactome maps and disease-risk association. Science (80-. ). 366, 1134–1139 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie S, Duan J, Li B, Zhou P & Hon GC Multiplexed Engineering and Analysis of Combinatorial Enhancer Activity in Single Cells. Mol. Cell 66, 285–299.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skene NG & Grant SGN Identification of Vulnerable Cell Types in Major Brain Disorders Using Single Cell Transcriptomes and Expression Weighted Cell Type Enrichment. Front. Neurosci 10, 16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ho SM et al. Evaluating Synthetic Activation and Repression of Neuropsychiatric-Related Genes in hiPSC-Derived NPCs, Neurons, and Astrocytes. Stem Cell Reports 9, 615–628 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duan J, Penzes P & Gejman P From Genetic Association To Disease Biology: 2d And 3d Human Ipsc Models of Neuropsychiatric Disorders and Crispr/Cas9 Genome Editing. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol 29, S763–S764 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 52.J, J. et al. Population-scale single-cell RNA-seq profiling across dopaminergic neuron differentiation. [] 9 (2020) doi: 10.1101/2020.05.21.103820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Powell J Single cell eQTL analysis identifies cell type-specific genetic control of gene expression in fibroblasts and reprogrammed induced pluripotent stem cells. bioRxiv 2020.06.21.163766 (2020) doi: 10.1101/2020.06.21.163766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mitchell JM et al. Mapping genetic effects on cellular phenotypes with ‘cell villages’. bioRxiv 2020.06.29.174383 (2020) doi: 10.1101/2020.06.29.174383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Finucane HK et al. Heritability enrichment of specifically expressed genes identifies disease-relevant tissues and cell types. Nat. Genet 50, 621–629 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rajarajan P et al. Spatial genome exploration in the context of cognitive and neurological disease. Current Opinion in Neurobiology vol. 59 112–119 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rehbach K, Fernando MB & Brennand KJ Integrating CRISPR Engineering and hiPSC-Derived 2D Disease Modeling Systems. J. Neurosci 40, 1176–1185 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nehme R & Barrett LE Using human pluripotent stem cell models to study autism in the era of big data. Mol. Autism 11, 21 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deneault E et al. Stem Cell Reports Article Complete Disruption of Autism-Susceptibility Genes by Gene Editing Predominantly Reduces Functional Connectivity of Isogenic Human Neurons. Stem Cell Reports 11, 1211–1225 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anzalone AV et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 576, 149–157 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA & Liu DR Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 533, 420–424 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gilbert LA et al. XCRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell 154, 442 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Larson MH et al. CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Nat. Protoc 8, 2180–2196 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hilton IB et al. Epigenome editing by a CRISPR-Cas9-based acetyltransferase activates genes from promoters and enhancers. Nat. Biotechnol 33, 510–517 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Balboa D et al. Conditionally Stabilized dCas9 Activator for Controlling Gene Expression in Human Cell Reprogramming and Differentiation. Stem Cell Reports 5, 448–459 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Savell KE et al. A neuron-optimized CRISPR/dCas9 activation system for robust and specific gene regulation. eNeuro 6, 1–17 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hilton IB et al. Activates Genes From Promoters and Enhancers. Nat. Biotechnol 33, 510–517 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tian R et al. CRISPR Interference-Based Platform for Multimodal Genetic Screens in Human iPSC-Derived Neurons. Neuron 104, 239–255.e12 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schrode N et al. Synergistic effects of common schizophrenia risk variants. Nat. Genet 51, 1475–1485 (2019).This paper nicely shows how the colocalization of GWAS and eQTL data, used to identify a putative causal variant (FURIN) in REF. 31, can be functionally validated in vitro. Specifically, this study used CRISPR editing and allelic conversion of a causal allele in hiPSC-derived neurons to measure phenotypic effects.

- 70.Nickolls AR et al. Transcriptional Programming of Human Mechanosensory Neuron Subtypes from Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell Rep. 30, 932–946.e7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lalli MA, Avey D, Dougherty JD, Milbrandt J & Mitra RD High-throughput single-cell functional elucidation of neurodevelopmental disease-associated genes reveals convergent mechanisms altering neuronal differentiation. 1–53 doi: 10.1101/862680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zaslavsky K et al. SHANK2 mutations associated with autism spectrum disorder cause hyperconnectivity of human neurons. Nat. Neurosci 22, 556–564 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang S et al. Allele-specific open chromatin in human iPSC neurons elucidates functional disease variants. Science (80-. ). 369, 561–565 (2020).Identifies allele-specific and disorder-associated open chromatin regions in hiPSC neurons. This study also identified 26-29% overlap between allele-specific open chromatin regions and non-neuronal MPRA SNPs from REF. 85. The ATAC-seq datasets from this study could be integrated with information from future or existing MPRA datasets to provide endogenous context and match regulatory enhancer activity to specific brain cell types.

- 74.Breen MS et al. Transcriptional signatures of participant-derived neural progenitor cells and neurons implicate altered Wnt signaling in Phelan McDermid syndrome and autism. bioRxiv 855163 (2019) doi: 10.1101/855163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.de Boer CG et al. Deciphering eukaryotic gene-regulatory logic with 100 million random promoters. Nat. Biotechnol 38, 56–65 (2020).Reports one of the largest MPRA libraries, asessing the regulatory logic of 100 million promoters in vivo. Althoug performed in yeast, this study hints at the possibility of increasing the scale of MPRAs in other cell types.

- 76.Birnbaum RY et al. Systematic Dissection of Coding Exons at Single Nucleotide Resolution Supports an Additional Role in Cell-Specific Transcriptional Regulation. PLoS Genet. 10, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Patwardhan RP et al. High-resolution analysis of DNA regulatory elements by synthetic saturation mutagenesis. Nat. Biotechnol 27, 1173–1175 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kheradpour P et al. Systematic dissection of regulatory motifs in 2000 predicted human enhancers using a massively parallel reporter assay. Genome Res. 23, 800–811 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gordon MG et al. lentiMPRA and MPRAflow for high-throughput functional characterization of gene regulatory elements. Nat. Protoc 15, 2387–2412 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Van Arensbergen J et al. High-throughput identification of human SNPs affecting regulatory element activity Europe PMC Funders Group. Nat Genet 51, 1160–1169 (2019).Describes a novel MPRA technique, the SuRE MPRA, that allows for substantial expansion of library size. By creating two random genome-expanding libraries containing ~300 million variants, this study identifies transcriptional shifts for 5.9 millions SNPs in human cells and provides a dataset that can assist in the identification of casual allelse from the list of eQTL and GWAS hits.

- 81.Fulco CP et al. Activity-by-contact model of enhancer–promoter regulation from thousands of CRISPR perturbations. Nat. Genet 51, 1664–1669 (2019).Describes the CRISPRi-FlowFISH method, a CRISPR screening appraoch using scRNA-seq. Although it has limited scalability, FACs sorting and scRNA-seq can expand the application and resolution of this technique. By developing an Activity-by-Contact model of regualtory logic, this study integrates CRISPR screens, scRNA-seq, and ATAC-seq data.

- 82.Kircher M et al. Saturation mutagenesis of twenty disease-associated regulatory elements at single base-pair resolution. Nat. Commun 10, 1–15 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Inoue F, Kreimer A, Ashuach T, Ahituv N & Yosef N Identification and Massively Parallel Characterization of Regulatory Elements Driving Neural Induction. Cell Stem Cell 25, 713–727.e10 (2019).Expands the application of past MPRAs by using a lenti-viral technique for chromosomal integration. To our knowledge, this study is the first instance of MPRAs in hiPSC neural progenitor cells, thereby showing the potential for massively parallel assays to be adapted for use in hiPSC models to provide cell-specific and donor-specific context.

- 84.Uebbing S et al. Massively parallel discovery of human-specific substitutions that alter neurodevelopmental enhancer activity. bioRxiv 865519 (2019) doi: 10.1101/865519.To our knowledge, is the first report of MPRAs in human-derived neurons. While previous studies succesfully adapted MPRAs for use in human-derived neural stem cells, this study succesfully probed thousands of enhancers associated with human corticogenesis and neurodevelopment.

- 85.Tewhey R et al. Direct identification of hundreds of expression-modulating variants using a multiplexed reporter assay. Cell 165, 1519–1529 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Myint L et al. A screen of 1,049 schizophrenia and 30 Alzheimer’s-associated variants for regulatory potential. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet 183, 61–73 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Geller E et al. Massively parallel disruption of enhancers active during human corticogenesis. bioRxiv 852673 (2019) doi: 10.1101/852673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nicholas CR et al. Functional maturation of hPSC-derived forebrain interneurons requires an extended timeline and mimics human neural development. Cell Stem Cell 12, 573–586 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tian A, Muffat J & Li Y Studying Human Neurodevelopment and Diseases Using 3D Brain Organoids. J. Neurosci 40, 1186–1193 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Burke EE et al. Dissecting transcriptomic signatures of neuronal differentiation and maturation using iPSCs. Nat. Commun 11, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Klein J et al. A systematic evaluation of the design, orientation, and sequence context dependencies of massively parallel reporter assays. bioRxiv 576405 (2019) doi: 10.1101/576405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ernst J et al. Genome-scale high-resolution mapping of activating and repressive nucleotides in regulatory regions. Nat. Biotechnol 34, 1180–1190 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dixit A et al. Perturb-Seq: Dissecting Molecular Circuits with Scalable Single-Cell RNA Profiling of Pooled Genetic Screens. Cell 167, 1853–1866.e17 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Diao Y et al. A tiling-deletion-based genetic screen for cis-regulatory element identification in mammalian cells. Nat. Methods 14, 629–635 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jin X et al. In vivo Perturb-Seq reveals neuronal and glial abnormalities associated with Autism risk genes. bioRxiv 791525 (2019) doi: 10.1101/791525.Applies the Perturb-seq technique first reported in REF. 93 to interogate the influence of risk genes for a neurodevelopmental disorder in an hiPSC model. Phenotypic abberations in neuronal and glial cells support the use of CRISPR-based screens with scRNA-seq to determine cell-type specific mechanisms underlying risk for complex brain disorders.

- 96.Gasperini M, Tome JM & Shendure J Towards a comprehensive catalogue of validated and target-linked human enhancers. Nat. Rev. Genet 40, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mimitou EP et al. Multiplexed detection of proteins, transcriptomes, clonotypes and CRISPR perturbations in single cells. Nat. Methods 16, 409–412 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cederquist GY et al. A Multiplex Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Platform Defines Molecular and Functional Subclasses of Autism-Related Genes. Cell Stem Cell 27, 35–49.e6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tian R et al. Genome-wide CRISPRi/a screens in human neurons link lysosomal failure to ferroptosis. bioRxiv 2020.06.27.175679 (2020) doi: 10.1101/2020.06.27.175679.This study used three screening techniques (genome-wide random screens, CRISPRa/i target screen, and CROP-seq screen) for the identification and further exploration of oxidative-stress related enhancers in human neurons. This study provides evidence for the application of complex and large-scale CRISPRa/i screens in mature human brain cells.

- 100.Liu Y et al. CRISPR Activation Screens Systematically Identify Factors that Drive Neuronal Fate and Reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 23, 758–771.e8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yang J et al. Genome-Scale CRISPRa Screen Identifies Novel Factors for Cellular Reprogramming. Stem Cell Reports 12, 757–771 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gaffney DJ Mapping and predicting gene–enhancer interactions. Nature Genetics vol. 51 1662–1663 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Abud EM et al. iPSC-Derived Human Microglia-like Cells to Study Neurological Diseases. Neuron 94, 278–293.e9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Takahashi K & Yamanaka S Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors. Cell 126, 663–676 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bliss LA et al. Use of Postmortem Human Dura Mater and Scalp for Deriving Human Fibroblast Cultures. PLoS One 7, 1–7 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhang Y et al. Rapid single-step induction of functional neurons from human pluripotent stem cells. Neuron 78, 785–798 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Theka I et al. Rapid Generation of Functional Dopaminergic Neurons From Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Through a Single-Step Procedure Using Cell Lineage Transcription Factors. Stem Cells Transl. Med 2, 473–479 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Barretto N et al. ASCL1- and DLX2-induced GABAergic neurons from hiPSC-derived NPCs. J. Neurosci. Methods 334, 108548 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]