Abstract

BK calcium-activated potassium channels have complex kinetics because they are activated by both voltage and cytoplasmic calcium. The timing of BK activation and deactivation during action potentials determines their functional role in regulating firing patterns but is difficult to predict a priori. We used action potential clamp to characterize the kinetics of voltage-dependent calcium current and BK current during action potentials in Purkinje neurons from mice of both sexes, using acutely dissociated neurons that enabled rapid voltage clamp at 37°C. With both depolarizing voltage steps and action potential waveforms, BK current was entirely dependent on calcium entry through voltage-dependent calcium channels. With voltage steps, BK current greatly outweighed the triggering calcium current, with only a brief, small net inward calcium current before Ca-activated BK current dominated the total Ca-dependent current. During action potential waveforms, although BK current activated with only a short (∼100 μs) delay after calcium current, the two currents were largely separated, with calcium current flowing during the falling phase of the action potential and most BK current flowing over several milliseconds after repolarization. Step depolarizations activated both an iberiotoxin-sensitive BK component with rapid activation and deactivation kinetics and a slower-gating iberiotoxin-resistant component. During action potential firing, however, almost all BK current came from the faster-gating iberiotoxin-sensitive channels, even during bursts of action potentials. Inhibiting BK current had little effect on action potential width or a fast afterhyperpolarization but converted a medium afterhyperpolarization to an afterdepolarization and could convert tonic firing of single action potentials to burst firing.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT BK calcium-activated potassium channels are widely expressed in central neurons. Altered function of BK channels is associated with epilepsy and other neuronal disorders, including cerebellar ataxia. The functional role of BK in regulating neuronal firing patterns is highly dependent on the context of other channels and varies widely among different types of neurons. Most commonly, BK channels are activated during action potentials and help produce a fast afterhyperpolarization. We find that in Purkinje neurons BK current flows primarily after the fast afterhyperpolarization and helps to prevent a later afterdepolarization from producing rapid burst firing, enabling typical regular tonic firing.

Keywords: action potential clamp, calcium channel, cerebellum, iberiotoxin, KCa1.1, paxilline

Introduction

Large-conductance (BK) calcium-activated potassium channels are widely expressed in neurons (Sausbier et al., 2006) and are important regulators of neuronal electrical activity (N'Gouemo, 2014; Contet et al., 2016; Dopico et al., 2016; Kshatri et al., 2018). Because BK channels are gated by both voltage and cytoplasmic calcium, their kinetics are inherently complex, especially during action potentials, where both voltage and the submembrane calcium concentration change rapidly on a submillisecond time scale. The exact timing of BK channel activation and deactivation is critical to their functional role, which can either slow or speed firing rates depending on timing during the firing cycle and on what other channels are present (Smith et al., 2002; Faber and Sah, 2003; Brenner et al., 2005; Meredith et al., 2006; Gu et al., 2007; Pedroarena, 2011; Montgomery and Meredith, 2012; for review, see Contet et al., 2016). Numerous channelopathies involving both gain of function and loss of function of BK channels have been described, but it is often difficult to understand exactly how the altered behavior of BK channels results in brain dysfunction because BK current can both promote and inhibit neuronal excitability (Bailey et al., 2019). Cerebellar Purkinje neurons express BK channels (Womack and Khodakhah, 2002; Edgerton and Reinhart, 2003; McKay and Turner, 2004; Womack et al., 2009); composed of at least two populations of channels with different kinetics and sensitivity to the peptide inhibitor iberiotoxin (IbTx; Benton et al., 2013). Genetic ablation of BK channels results in cerebellar ataxia associated with complex changes in overall cerebellar circuit behavior, with critical involvement of altered Purkinje neuron function (Sausbier et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2010; Cheron et al., 2018).

BK channels are tetrameric complexes of the primary KCa1.1 α-subunit, generally combined with a variety of auxiliary subunits that modify channel voltage dependence and kinetics (Nimigean and Magleby, 1999; Berkefeld et al., 2010; Jaffe et al., 2011; Li and Yan, 2016; Latorre et al., 2017; Gonzalez-Perez and Lingle, 2019), with the exact molecular makeup of native channels in neurons usually unknown. In addition, BK channels often exist in microdomains or nanodomains with calcium channels (Marrion and Tavalin, 1998; Berkefeld et al., 2006; Loane et al., 2007; Berkefeld and Fakler, 2008; Berkefeld et al., 2010; Indriati et al., 2013; Irie and Trussell, 2017); so that activation kinetics of BK channels depend on the kinetics and magnitude of calcium entry through voltage-dependent calcium channels, the exact arrangement and stoichiometry of the two types of channels, and calcium buffering properties. This complexity makes it impossible to define a priori how the size and speed of BK channel activation and deactivation will depend on calcium entry through calcium channels, which itself has complex kinetics during action potentials.

Here we characterized the kinetics of voltage-dependent calcium current and BK current on the submillisecond time scale during action potential firing of Purkinje neurons. Using acutely dissociated neurons, we defined the kinetics of calcium current and two components of BK current during action potential firing at 37°C. We find that although BK activation follows calcium entry through voltage-dependent calcium channels within ∼100 μs, during the action potential the two currents are largely separated, with almost all calcium current flowing during the falling phase of the action potential and most BK channel current flowing over a few milliseconds after repolarization. Step depolarizations showed two components of BK current, an iberiotoxin-sensitive component that activated and deactivated rapidly, along with a sizeable iberiotoxin-resistant component that activated and deactivated much more slowly. Surprisingly, during action potential firing at 37°C, almost all BK current came from iberiotoxin-sensitive channels, even during rapid firing of action potentials where submembrane calcium might be expected to accumulate. The iberiotoxin-sensitive BK conductance following the action potential promotes rhythmic firing of single spikes, with inhibition of BK channels by iberiotoxin often converting tonic firing of single spikes into firing of bursts of doublets or triplets.

Materials and Methods

Cell preparation.

Experiments were performed with cerebellar Purkinje neurons acutely dissociated from Swiss Webster mice of either sex [postnatal day 12 (P12) to P15]. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated. The brain was rinsed with ice-cold solution containing the following (in mm): 110 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 7.5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 25 glucose, and 75 sucrose, with pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. Cerebella were then excised and minced to ∼1 mm pieces in 10 ml of dissociation solution containing the following (in mm): 82 Na2SO4, 30 K2SO4, 5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose, with pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH, with addition of 3 mg/ml protease XXIII enzyme (Sigma-Aldrich) together with 1 μl of 0.1 m NaOH per 1 mg of protease to offset acidification from the enzyme. Tissue was incubated in the enzyme-containing solution for 10 min at 37°C and then transferred to a solution containing 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 mg/ml trypsin inhibitor (chicken egg white, Sigma-Aldrich). From this point, tissue was kept on ice, and pieces of tissue were withdrawn as needed. Each piece was incubated at 37°C for 10 min to loosen up the tissue and then triturated with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette to release cells. A drop of the suspension was placed in the recording chamber and diluted with a large volume of Tyrode's solution, consisting of the following (in mm): 155 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 1.5 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose, with pH adjusted to 7.4 with ∼5 mm NaOH. Purkinje neurons were identified by their large size, tear-drop shape, and a single large dendritic stump.

Use of acutely dissociated neurons enables rapid voltage clamp on the time scale of the action potential in the same preparation in which action potential firing is recorded and facilitates rapid solution changes to define individual ionic currents (Raman and Bean, 1999). Action potential firing in dissociated Purkinje neurons is similar to that from somata of intact Purkinje neurons, including firing spontaneously at typical frequencies of ∼30 Hz (Häusser and Clark, 1997; Raman and Bean, 1997, 1999; Edgerton and Reinhart, 2003) and the ability to fire bursts of action potentials (Raman and Bean, 1997; Swensen and Bean, 2003; Davie et al., 2008). The width of action potentials in dissociated Purkinje neurons (median of 0.24 ms in our experiments at 37°C) is very similar to that of action potentials recorded from intact Purkinje neurons in slices [0.15 ms at 35°C (Hurlock et al., 2008); 0.23 ms at 35°C (McKay and Turner, 2004); 0.26 ms at 35°C (Zagha et al., 2008); 0.28 ms at 33°C (Chopra et al., 2018); 0.33 ms at 35°C (Womack et al., 2009)], suggesting that the timing of BK channel activation during the action potentials in dissociated neurons is similar to that for action potentials in intact cells.

To test the possibility that the magnitude or functional properties of BK current might change with age, we attempted experiments in cells from older mice (P25–P35). However, the yield and health of the dissociated neurons dropped precipitously in older animals, and we were unsuccessful. While we cannot rule out changes in BK properties with development, we note that Edgerton and Reinhart (2003) saw no difference in the effect of iberiotoxin on the firing of Purkinje neurons when comparing recordings in P13–P15 versus P24–P31 rats.

Electrodes and solutions.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made using electrodes pulled from borosilicate capillaries (catalog #53432–921, VWR International) using a Sutter Instrument P-97 puller. Electrodes had resistances of 2–4 MΩ when filled with the internal solution consisting of the following (in mm): 140 K-methanesulfonate, 10 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, 0.2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 4 MgATP, and 0.3 GTP (Tris salt), and 14 phosphocreatine (Tris salt), with pH adjusted to 7.4 with KOH. Although calcium buffering by artificial solutions containing EGTA cannot perfectly replicate endogenous calcium buffering, previous results showed that intracellular solutions with ∼1 mm EGTA preserved bursting activity seen before and after whole-cell dialysis in cells where endogenous bursting was seen in cell-attached patches (Swensen and Bean, 2003), suggesting a lack of dramatic effect on the activity of calcium-activated potassium channels with this recording solution. Previous recordings in mouse Purkinje neurons found that the kinetics of BK current were no different when studied with 0.5 or 5 mm EGTA (Benton et al., 2013), consistent with the tight coupling of calcium channels and BK channels reflecting colocalization as seen with double immunogold labeling (Indriati et al., 2013).

Electrode tips were wrapped with thin strips of Parafilm to reduce pipette capacitance. Recordings were corrected for the liquid junction potential of −8 mV between the intracellular solution and the extracellular Tyrode's solution in which current was zeroed before patch formation.

Solution exchange and temperature control.

After forming a GΩ seal and achieving the whole-cell configuration, cells were lifted and positioned in front of a series of quartz flow pipes (inner diameter, 250 µm; outer diameter, 350 µm; PolyMicro Technologies) attached with polyurethane glue to an aluminum square rod (cross section, 1.5 × 0.5 cm) whose temperature is controlled using resistive heating elements and a feedback-controlled temperature controller (catalog #TC-344B, Warner Instruments). Cells were moved between pipes for rapid solution changes. Experiments were performed at 37°C.

In voltage-clamp experiments, BK and calcium channel currents were isolated pharmacologically. Experiments were performed on a background of 1 μm TTX (Abcam) to inhibit sodium current and 100 μm 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) to inhibit the dominant voltage-activated potassium current. BK current was defined by the application of 3 μm paxilline (Pax) or by sequential cumulative application of 200 nm iberiotoxin (Alomone Labs) and 3 μm paxilline to define separate components of iberiotoxin-sensitive and iberiotoxin-resistant BK current. All solutions contained 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin to minimize adhesion of iberiotoxin or paxilline to the perfusion reservoirs and tubing.

Voltage-dependent calcium current was defined by removal of calcium on a background in which BK current was inhibited [by paxilline or by 10 mm tetraethylammonium (TEA) chloride], replacing 1.5 mm CaCl2 by 4 mm MgCl2 (thus switching from a solution with 1.5 mm CaCl2 and 1 mm MgCl2 to one with 0 CaCl2 and 5 mm MgCl2). Calcium was replaced by a higher concentration of magnesium because calcium more effectively screens the surface charge, which helps to determine the voltage dependence of channels (Hille et al., 1975); we empirically found that replacing 1.5 mm calcium by 4 mm magnesium best preserved the normal voltage dependence of sodium channels as assayed by the midpoint of the inactivation curve (B. Carter, unpublished observations). In initial experiments, calcium current was defined by magnesium replacement for calcium using solutions containing paxilline to inhibit BK current; however, with these solutions, the current defined by calcium removal included a small outward current following repolarization to −40 mV after a test pulse to −20 mV activated calcium entry (Fig. 1B). This outward current likely reflects calcium-activated SK current (Swensen and Bean, 2003). In subsequent experiments to quantify calcium current, we therefore performed calcium replacement by magnesium on a background of 10 mm TEA, which inhibited this presumptive SK current (Lang and Ritchie, 1990).

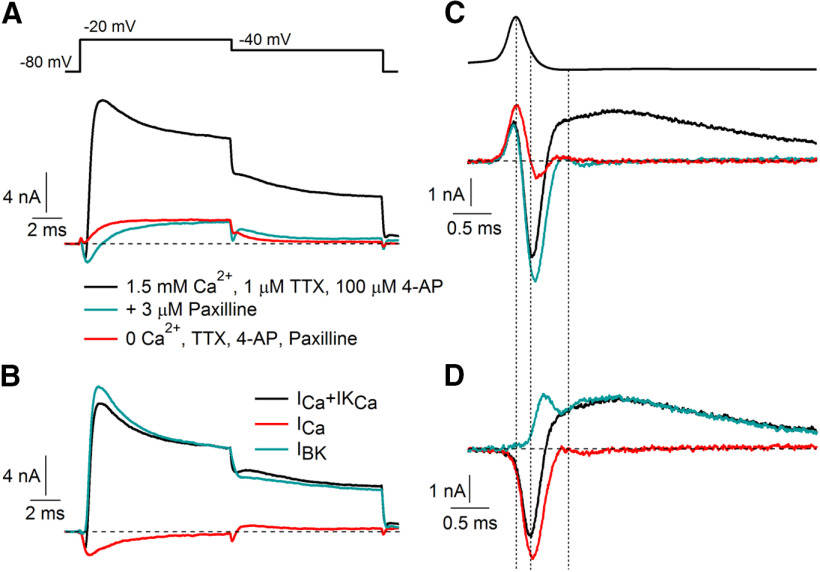

Figure 1.

BK and calcium currents evoked by step depolarizations and action potential waveforms. A, Current evoked by a step depolarization from −80 to −20 mV before (black) and after (green) application of 3 μm paxilline, with sodium current blocked by 1 μm TTX and Kv3 potassium current inhibited by 100 μm 4-AP. Replacing extracellular CaCl2 by MgCl2 (red trace) eliminated the inward current carried by calcium, as well as a small outward current (seen during the step to −40 mV following that to −20 mV) likely carried by calcium-activated SK channels. B, BK current defined by paxilline inhibition (green), calcium current defined by calcium removal in the presence of paxilline, 4-AP, and TTX (red), and the sum of BK and calcium current (black). C, D, Same as A and B with currents evoked by an action potential waveform.

The possible role of calcium-induced calcium release in BK channel activation was tested by performing measurements of BK current in the presence of either 5 μm ryanodine (to inhibit ryanodine receptors) or 1 μm thapsigargin (to inhibit sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pumps). To ensure that the inhibitors had sufficient time to exert their effects, ryanodine or thapsigargin was added to the dissociation inhibitor storage solution, in which cells were held for at least 30 min (usually 1–2 h), as well as being present subsequently in all solutions based on Tyrode's solution in the experimental chamber and in the perfusion pipes during the actual recording.

Experiments examining iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current with high intracellular calcium and no calcium entry were performed using a modified K-methanesulfonate intracellular solution with 100 μm CaCl2 added and no EGTA. To minimize the time between starting the cell dialysis and recording current, cells were bathed in a Ca-free Tyrode's solution containing 1 μm TTX, 100 μm 4-AP, 5 mm MgCl2, and no CaCl2 as soon as the rupture appeared stable. After 15 s in this solution, the sequence of step protocols was run, 200 nm IbTx was applied for ∼30 s, and the step protocols were run again.

Action potential-clamp experiments used three different command waveforms taken from previous recordings of typical action potential firing at 37°C. One was a section of typical spontaneous action potential firing (42 Hz) with no injection of current. The second was a section of higher-frequency firing (134 Hz) evoked by a 150 pA, 500 ms current injection, using firing during the latter part of the step to capture steady-state firing. The third was high-frequency burst firing evoked by injection of a large EPSC-like current (500 pA amplitude with an exponential rising phase with a time constant of 0.22 ms and an exponential decay phase with a time constant of 3 ms). The resulting burst fired four action potentials at ∼900 Hz on an underlying depolarization that lasted ∼15 ms until returning to baseline.

In previous experiments with the same preparation, we did control experiments to test the fidelity with which the action potential commands are imposed on the cell by using a second pipette to record voltage while the cell was voltage clamped with the first pipette. These experiments showed that the peak of the action potential was imposed faithfully with an average deviation of ∼2 mV and that the action potential width was faithful within ∼5% (Carter and Bean, 2009).

Current-clamp experiments were performed without holding current. Cells were considered healthy if they fired spontaneously and stably with overshoot potentials of at least +20 mV or greater in control conditions without requiring any holding current.

Data acquisition and analysis.

Recordings were made using a Multiclamp 700B Amplifier (Molecular Devices) and a Digidata 1322A analog-to-digital converter (Molecular Devices), controlled by Clampex version 10.3.1.5 software (Molecular Devices). Currents and voltages were low-pass filtered at 10 kHz using the amplifier circuitry and sampled at 100–200 kHz. In voltage clamp, capacitive current was minimized using the capacitive compensation circuitry of the MultiClamp 700B amplifier, and series resistance was compensated by 70% with a bandwidth of 1.02 kHz. For step depolarizations, remaining capacitive currents were corrected offline during analysis using small (5–10 mV) steps in a hyperpolarized range (negative to −70 mV) to define linear capacitance and leak currents and then subtracting appropriately scaled currents. In action potential-clamp experiments, remaining capacity transients and leak currents were defined by a waveform consisting of the action potential waveform relative to holding potential scaled down fourfold and inverted.

Even with optimal tuning of series resistance compensation, there is a lag in the voltage seen at the cell membrane relative to the command voltage delivered to the wire in the electrode, which can be significant on the time scale of the narrow action potentials of Purkinje neurons at 37°C (Carter and Bean, 2009, 2011). To properly align the measured currents with the command voltage in analyzing the action potential-clamp data, we accounted for the combined effect of this lag together with the lag resulting from the low-pass filtering of the current signal (at 10 kHz, using the amplifier circuitry). In calibration experiments, we measured the overall lag in the system as previously described (Carter and Bean, 2011) by performing action potential-clamp experiments with a reduced external sodium concentration (32 mm) so that the driving force for sodium changes from inward to outward during the action potential waveform; the times of the reversal of current from inward to outward and back again can be compared with the command action potential waveform to determine the overall delay. Delays of 100–180 µs were measured in different cells, with variation most likely depending on the exact shape of the electrode shank and efficacy of reduction of electrode capacitance by Parafilm wrapping. In aligning the current records with action potential command voltages for analysis, we used a value of 136 µs for the total lag, near the median of the calibration measurements.

In current-clamp experiments, series resistance was compensated using the amplifier bridge–balance circuitry, and pipette capacitance was partially compensated to improve frequency response.

Data were analyzed in Igor Pro version 6.37 (WaveMetrics) using DataAccess (Bruxton) to import pClamp files. Action potential waveforms during spontaneous firing were quantified by signal-averaging spikes over ∼1 s of recording time. Analysis of the effect of iberiotoxin on the medium afterhyperpolarization were confined to cells in which there was a well defined medium afterhyperpolarization in control conditions, with a transient depolarizing phase separating the fast afterhyperpolarization and the medium afterhyperpolarization. In some cases, after inhibition of BK channels with iberiotoxin there was no longer a clear separation between the fast afterhyperpolarization and the medium afterhyperpolarization; in these cases, the medium afterhyperpolarization in iberiotoxin (or iberiotoxin plus paxilline) was measured at the time of the medium afterhyperpolarization in control. Cells that switched from tonic single-spike firing to burst firing in iberiotoxin were not included in analysis of the effect of iberiotoxin on action potential waveforms because burst firing fundamentally changed the interspike voltage trajectories: instead of the nearly identical interspike intervals seen with regular spontaneous firing, with burst firing there was a longer interspike interval between bursts and very short interspike intervals within bursts, so that action potentials were highly nonuniform. Calculations of the effect of iberiotoxin and paxilline on “resting potential” were made using segments of spontaneous firing ∼1 s long, with voltage segments during spikes removed (with spikes defined as the time from spike threshold, calculated as 4% of the maximum upstroke velocity during the spike, to the time on the falling phase of the spike when this same absolute value of voltage was crossed, just before the fast afterhyperpolarization).

Experimental design and statistical analysis.

Animals of both sexes were used because preliminary experiments showed that cells from both sexes had BK currents with no obvious difference in magnitude or kinetics and previous experience has shown no obvious differences in the overall electrophysiology of Purkinje neurons from male and female animals in this age range (P12–P15). The number of animals (n = 6) and cells (n = 13–15 for various measurements, one to four cells per animal) used for characterization of BK channel kinetics (Figs. 1–11) were based on previous experience showing no systematic animal-to-animal variability in magnitude and kinetics of ionic currents, with substantial cell-to-cell variability in magnitude but not kinetics of individual ionic currents, including calcium-activated potassium currents (Raman and Bean, 1999; Swensen and Bean, 2003; Benton et al., 2013). The number of animals (n = 8) and cells (n = 13, one to three cells from each animal) used for characterizing the effects of BK inhibition on action potential characteristics followed the same reasoning.

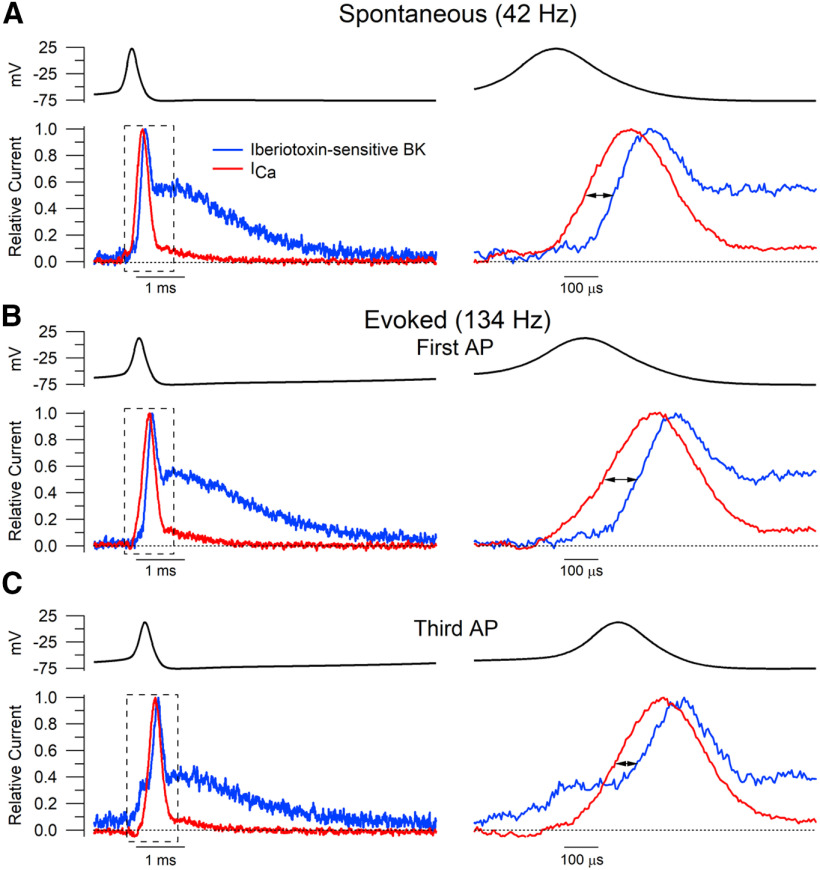

Figure 11.

Delay between calcium current and IbTx-sensitive BK current activation during action potential waveforms. IbTx-sensitive BK and calcium currents were normalized to their individual peak amplitudes. A–C, The time for each current to reach half its peak amplitude was determined for both spontaneous (A) and evoked (B, C) action potential waveforms. A, IbTx-sensitive BK current activated slightly later than calcium current during spontaneous action potentials (108 ± 22 μs, n = 12). B, A similar delay was found for the first action potential of the evoked train (105 ± 20 μs, n = 12). C, IbTx-sensitive BK current began to activate earlier in action potentials occurring later in the evoked train (56 ± 34 μs, n = 12).

Group data were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Most datasets met the condition for normality (using p > 0.05 from the Shapiro–Wilk test); for these datasets, averages are given as the mean ± SEM and comparisons were made using Student's two-tailed t test. For the cases in which the Shapiro–Wilk test indicated significant non-normality, data are additionally given as median and range and the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used for comparisons between groups. In current-clamp experiments examining the effects of iberiotoxin followed by iberiotoxin plus paxilline, some cells were lost before the effects of paxilline could be measured; in these cases, statistics comparing measurements in iberiotoxin alone and iberiotoxin plus paxilline were determined with pairwise comparisons using the cells in which values in both solutions were measured.

Results

Calcium current and BK current during steps and action potentials

We quantified the BK current flowing during step depolarizations and action potential waveforms and compared it to the voltage-dependent calcium current. These experiments used solutions in which voltage-dependent sodium currents were inhibited by 1 μm TTX and Kv3-mediated current was inhibited by 100 μm 4-aminopyridine. Under these conditions, net ionic current evoked by a voltage step from −80 to −20 mV consisted of an initial inward current [reaching a peak of −1.58 ± 0.11 nA at 0.48 ± 0.02 ms (median, 0.46 ms; range, 0.39–0.89 ms), n = 20] followed by a much larger outward current [reaching a peak of 10.28 ± 0.90 nA at 2.27 ± 0.53 ms (median, 1.49 ms; range, 1.28–9.41 ms), n = 20; Fig. 1A]. The BK inhibitor paxilline (Sanchez and McManus, 1996; Zhou and Lingle, 2014; Zhou et al., 2020) inhibited almost 90% of the outward current (reduction to 1.23 ± 0.18 nA; 12 ± 2% of control; n = 20) and revealed an inward current larger than in the control. Consistent with being calcium current, the inward current was eliminated by replacing calcium by magnesium. Figure 1B shows the time course of BK current defined by paxilline inhibition along with calcium current, defined by the removal of calcium with BK current blocked. BK current was strikingly larger than the triggering calcium current whether quantified by peak current (BK, 10.89 ± 0.93 nA; vs Ca, −2.48 ± 0.17 nA) or by integrated current during the 10 ms step to −20 mV (BK, 64.56 ± 6.04 pC; vs Ca −10.08 ± 1.65 pC; n = 20; including experiments in which BK current was defined by combined application of iberiotoxin and paxilline, and calcium current was measured by removal of calcium on a background of 10 mm TEA as in Fig. 3)

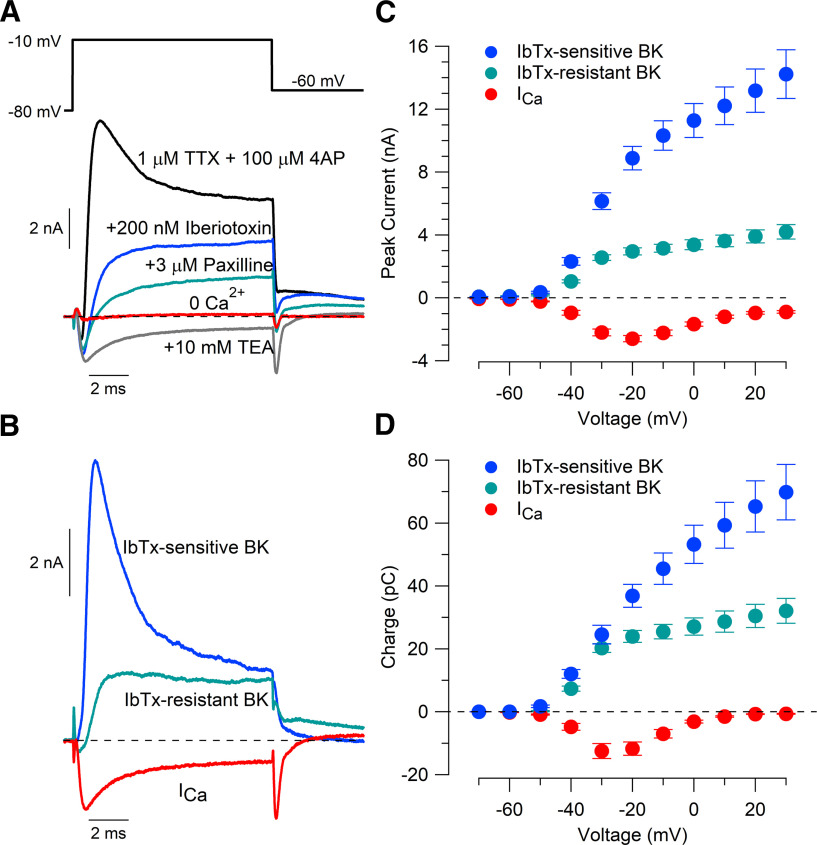

Figure 3.

Two components of BK current evoked by depolarizing steps. A, Currents evoked by a 10 ms depolarizing step from −80 to −10 mV with 1 μm TTX and 100 μm 4-AP (black), after the application of 200 nm iberiotoxin (blue), after the addition of 3 μm paxilline (green) in the continuing presence of iberiotoxin, after the addition of 10 mm TEA (gray; in the continuing presence of TTX and 4-AP but omitting iberiotoxin and paxilline), and after the removal of calcium (red; replacement of 1.5 mm CaCl2 by 4 mm MgCl2, in presence of TTX, 4-AP, and TEA). B, Iberiotoxin-sensitive BK, iberiotoxin-resistant BK, and calcium current defined by subtraction of records in A. C, Peak iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current, iberiotoxin-resistant BK current, and calcium current for 10 ms steps to voltages −70 to +30 mV. D, Integrated current (nA * ms or pC) during the 10 ms steps. Mean ± SEM: n = 15, IbTx-sensitive BK current; n = 14, IbTx-resistant BK current; n = 13, calcium current.

Figure 1, C and D, shows the currents evoked by an action potential waveform (previously recorded in a different cell, also at 37°C and with the same internal solution) during the same sequence of solution changes, in the same cell as Figure 1A. Peak calcium current evoked by the action potential waveform (−4.08 ± 0.33 nA) was larger than that evoked by the step to −20 mV (−2.48 ± 0.17 nA; n = 20), which was near the maximum of the peak current versus voltage for step depolarizations. The larger peak calcium current evoked by the action potential waveform suggests that although the action potential is brief (width, 0.28 ms at half-maximum amplitude), calcium channels are activated effectively, with the largest calcium current flowing during the falling phase of the action potential when the driving force for calcium is high. Interestingly, at 37°C, activation of calcium current is sufficiently rapid that there is substantial current flowing even at the peak of the action potential (+22 mV), although the driving force is small. Despite the larger calcium current during the action potential waveform compared with the step depolarization, BK current evoked during the action potential (peak, 1.36 ± 0.17 nA) was much smaller than that evoked by the step to −20 mV (10.89 ± 0.93 nA; n = 20), reaching a peak near the afterhyperpolarization (−77 mV) where driving force for potassium is low. Although action potential-evoked calcium current flowed at voltages where there was a large driving force for calcium, while action potential-evoked BK current flowed at voltages with a small driving force for potassium, total integrated BK current was larger [1.85 ± 0.30 pC (median, 1.54 pC; range, 0.32–5.41 pC)] than integrated calcium current (−1.16 ± 0.11 pC; n = 19) during the action potential waveform current. Thus, the net current produced by calcium entry during action potentials in Purkinje neurons at 37°C is outward, as previously seen for action potentials at room temperature (Raman and Bean, 1999).

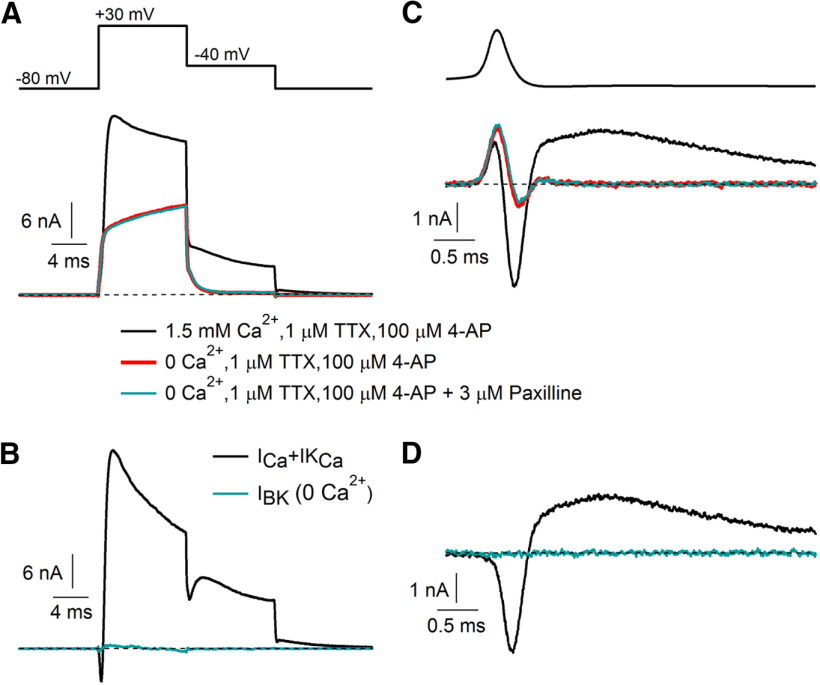

BK current during action potentials is entirely dependent on calcium entry

With large enough depolarizations, BK channels can be activated even at low concentrations of intracellular calcium, with the voltage dependence depending strongly on the effects of accessory subunits (Gonzalez-Perez and Lingle, 2019). In adrenal chromaffin cells, BK channels are able to be opened by action potential waveforms even in the absence of calcium entry (Scott et al., 2011).

Figure 2 shows recordings to test whether BK currents in Purkinje neurons can flow in the absence of calcium entry, testing for paxilline-sensitive current with Ca-free Tyrode's solution. There was no BK current without calcium entry, either during the action potential waveform or with a 10 ms step to +30 mV. The difference from chromaffin cells suggests a difference in the voltage dependence of BK channels, perhaps resulting from different combinations of accessory subunits (Li and Yan, 2016; Gonzalez-Perez and Lingle, 2019).

Figure 2.

BK current requires calcium entry. A, Current evoked by a step depolarization from −80 to +30 mV before (black) and after (red) removal of extracellular calcium (replacement of 1.5 mm CaCl2 by 4 mm MgCl2) on a background of 1 μm TTX and 100 μm 4-AP. Application of 3 μm paxilline (green) had no effect with a calcium-free external solution. B, Total calcium-sensitive current (calcium current plus calcium-activated potassium current) defined by removal of calcium (black) and BK current in calcium-free solution (green) defined by the application of paxilline in calcium-free solution. C, D, Same as A and B for currents evoked by an action potential waveform.

Iberiotoxin-sensitive and iberiotoxin-insensitive components of BK current

Previous recordings from rat and mouse Purkinje neurons showed the presence of both BK channels sensitive to inhibition by iberiotoxin (Womack and Khodakhah, 2002; Edgerton and Reinhart, 2003; Benton et al., 2013) and BK channels resistant to iberiotoxin (Benton et al., 2013), likely corresponding to channels containing the β4 subunit (Wang et al., 2014). To compare the voltage dependence and kinetics of these two components of BK current, we examined the effect of applying iberiotoxin followed by paxilline (applied in the continuing presence of iberiotoxin; Fig. 3A).

We found a large current inhibited by iberiotoxin with a smaller iberiotoxin-resistant current inhibited by paxilline (Fig. 3B). For currents evoked by steps to −20 mV, the peak iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current was 8.88 ± 0.75 nA (n = 15) compared with 2.95 ± 0.22 nA iberiotoxin-resistant BK current (n = 14), with an inward calcium current of −2.59 ± 0.20 nA (n = 13). The difference in magnitude between the two components of BK current was especially pronounced at more depolarized potentials; iberiotoxin-sensitive current increased with depolarizing steps up to +30 mV (Fig. 3C,D), while iberiotoxin-resistant current reached a plateau near −20 mV.

Figure 3D compares total charge (integrated current) for calcium current and the two components of BK current. The total outward charge transferred through BK channels was larger than the inward charge transferred through calcium channels at all voltages. The difference was biggest for depolarizations positive to −20 mV, where integrated calcium current was reduced as a consequence of reduced driving force and faster inactivation (Fig. 3D). The total charge transferred by iberiotoxin-sensitive BK channels accounted for the majority of total BK-mediated charge.

Calcium-induced calcium release

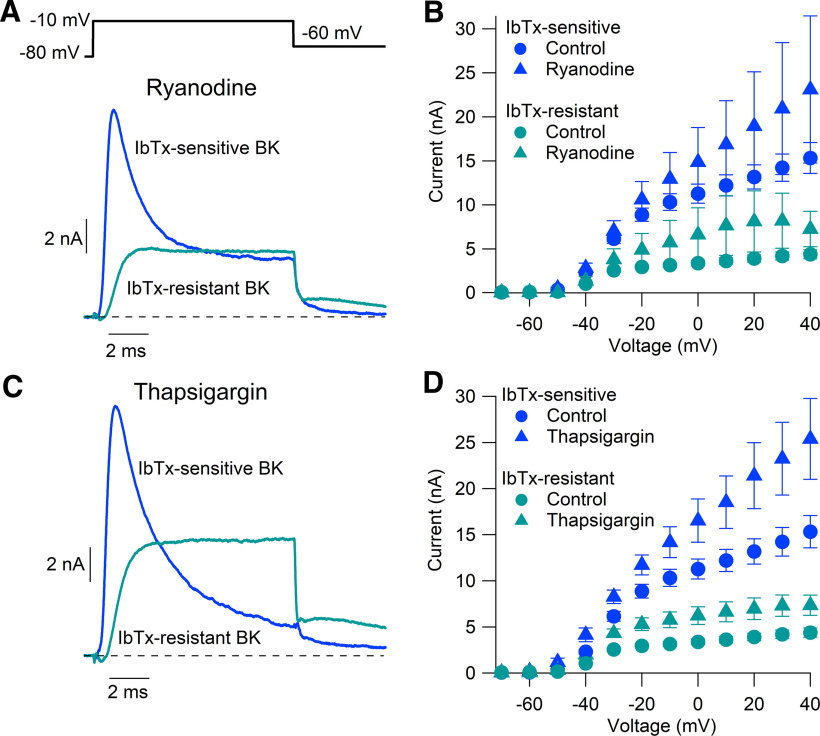

Calcium-induced calcium release plays a critical role in BK channel activation in some types of neurons, including cartwheel cells in the dorsal cochlear nucleus (Irie and Trussell, 2017), neurons in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (Whitt et al., 2018), and sympathetic neurons from stellate ganglia (Locknar et al., 2004). Although we found that BK current depends completely on extracellular calcium, it is possible that the entry of calcium could act in part through calcium-induced calcium release from intracellular stores. To test this, we recorded BK current in neurons exposed to either 5 μm ryanodine to inhibit ryanodine receptors or 1 μm thapsigargin to inhibit SERCA (sarcolemma/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase) pumps and deplete intracellular calcium stores.

BK currents elicited by 10 ms voltage steps in cells exposed to ryanodine or thapsigargin were not reduced compared with neurons under control conditions [at −20 mV, with ryanodine: iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current, 11.10 ± 1.80 nA (median, 10.29 nA; range, 6.89–20.05 nA), n = 7; iberiotoxin-resistant BK current, 4.50 ± 1.56 nA (median, 3.17 nA; range, 2.25–12.24 nA), n = 6; at −20 mV, with thapsigargin: iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current, 11.72 ± 1.09 nA (median, 12.79 nA; range, 8.01–14.65 nA), n = 6; iberiotoxin-resistant BK current, 5.70 ± 0.95 nA (median, 5.92 nA; range, 2.43–9.38 nA), n = 6; Fig. 4]. Thus, with both ryanodine and thapsigargin, both iberiotoxin-sensitive and iberiotoxin-resistant components were, if anything, somewhat larger than in control conditions [iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current, 8.88 ± 0.75 nA (n = 15); iberiotoxin-resistant BK current 2.95 ± 0.22 nA (n = 14)]. These results suggest that calcium-induced calcium release is not necessary for BK channel activation in Purkinje neurons. The results fit well with previous studies showing that while Purkinje neurons possess intracellular calcium stores (Llano et al., 1994; Kano et al., 1995; Khodakhah and Armstrong, 1997; Ryu et al., 2017), there is no obvious contribution of calcium-induced calcium release to the rise of intracellular calcium in the soma during depolarizing voltage steps <40 ms (Llano et al., 1994), even when measured in a submembrane somatic shell (Eilers et al., 1995; Kano et al., 1995). Interestingly, previous results showed that ryanodine incubation resulted in an increase in resting intracellular calcium (Llano et al., 1994), presumably reflecting a reduced ability to maintain uptake into intracellular stores as a result of the activation of ryanodine of low-conductance ryanodine receptor open states (Bezprozvanny et al., 1991; Hernández-Cruz et al., 1995). It seems possible that the slight increase of BK current in the experiments with ryanodine and thapsigargin could reflect such an increase in resting calcium.

Figure 4.

BK channel activation in Purkinje neurons is not dependent on calcium-induced calcium release. A, IbTx-sensitive (blue) and IbTx-resistant (green) BK current evoked by a 10 ms step from −80 to −10 mV, measured in the presence of 5 μm ryanodine. B, Peak current evoked by 10 ms steps from −70 to +40 mV in the presence of 5 μm ryanodine (triangles; n = 7) compared with control measurements [circles (replotted from Fig. 3C)]. C, D, Peak currents evoked in the presence of 1 μm thapsigargin (triangles; n = 6) compared with control measurements [circles (replotted from Fig. 3C)]. Mean ± SEM.

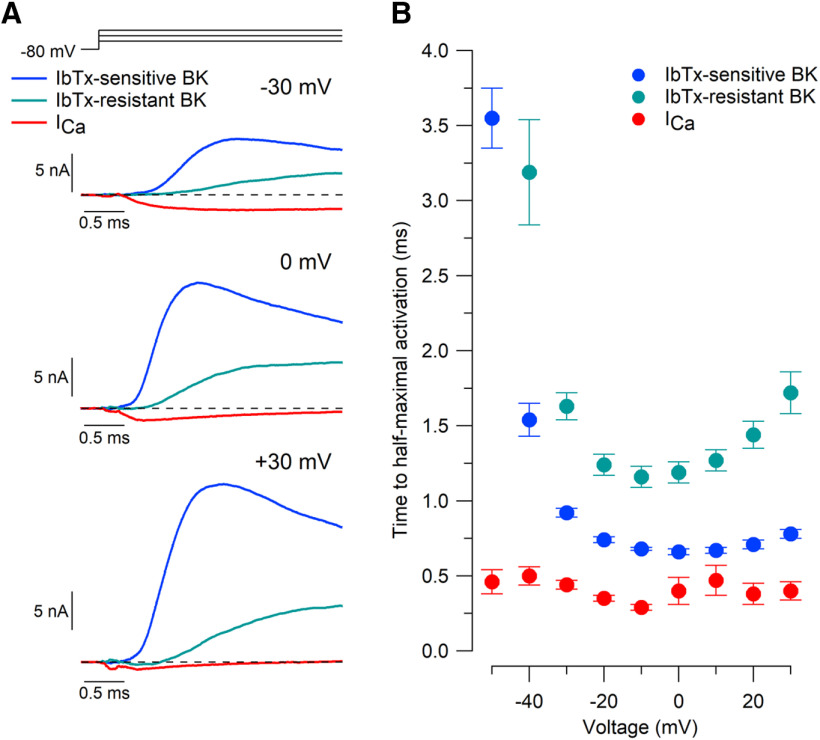

Activation kinetics

The kinetics of the two components of BK current were very different. Iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current activated quickly and displayed rapid and prominent inactivation (Fig. 5A). In contrast, iberiotoxin-resistant BK current was slower to activate and did not inactivate. These results are consistent with previous results in mouse Purkinje neurons (Benton et al., 2013) and with the expectation that iberiotoxin-resistant BK current represents channels containing the β4 subunit, which in studies of cloned channels results in slow kinetics of activation and resistance to iberiotoxin (Wang et al., 2014). The kinetics of both components of BK current were strongly voltage dependent, with fastest activation at 0 mV for IbTx-sensitive BK current (0.66 ± 0.02 ms to half-maximal current, n = 14; Fig. 5B) and at −10 mV for IbTx-resistant BK current (1.16 ± 0.05 ms to half-maximal current, n = 14). The activation kinetics of both components were unchanged in experiments performed in the presence of 5 μm ryanodine (IbTx sensitive: 0.62 ± 0.03 ms to half-maximal current, n = 6, p = 0.27 relative to control values; IbTx-resistant: 1.22 ± 0.04 ms to half-maximal current, n = 6, p = 0.49 relative to control) or 1 μm thapsigargin (IbTx-sensitive: 0.66 ± 0.02 ms to half-maximal current, n = 6, p = 0.85 relative to control; IbTx-resistant: 1.21 ± 0.07 ms to half-maximal current, n = 6, p = 0.62 relative to control).

Figure 5.

Activation kinetics of iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current, iberiotoxin-resistant BK current, and calcium currents. A, Initial time course of iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current, iberiotoxin-resistant BK current, and calcium current for steps to −30, 0, and +30 mV. Currents are defined as in Figure 3. B, Collected results for activation kinetics measured by time to half-maximal activation. Mean ± SEM: n = 14, IbTx-sensitive BK current and IbTx-resistant BK current; n = 12, calcium current.

Activation of both components of BK current slowed with depolarizations beyond 0 mV, especially for the iberiotoxin-resistant component, likely reflecting the smaller calcium current positive to 0 mV (Fig. 3D). Calcium current activated substantially faster than BK current at all voltages.

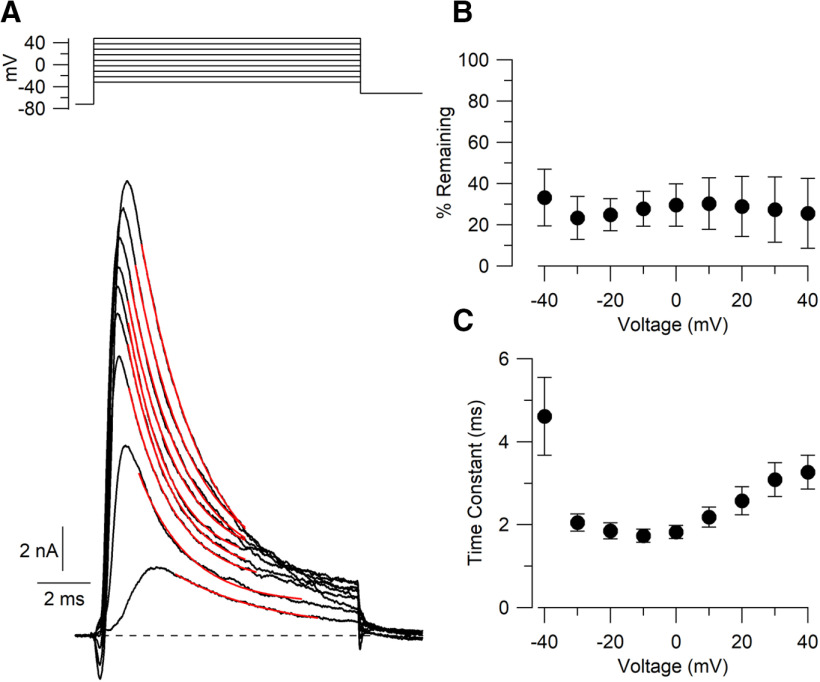

Inactivation

The iberiotoxin-sensitive component of BK current showed rapid, incomplete inactivation during voltage steps, as previously reported for iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current in mouse Purkinje neurons (Benton et al., 2013). Iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current inactivated to 23 ± 3% (n = 14) of the peak current during 10 ms steps to −30 mV and slightly less (to ∼25–30% of peak) for steps to more positive voltages up to +40 mV (Fig. 6). The main phase of inactivation was reasonably well fit by a single exponential function (Fig. 6A, red traces) with an additional much smaller phase of slower inactivation evident, especially for larger depolarizations. The time constant for the main phase of inactivation was fastest for steps to −10 mV (1.72 ± 0.16 ms, n = 14) and somewhat slower at more depolarized voltages (3.25 ± 0.41 ms at +40 mV, n = 14; Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Inactivation kinetics of iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current. A, BK current during 10 ms depolarizations from −40 to +40 mV. Red traces, Fits to single exponential functions over the period of the fitted trace. B, Collected results for percent of peak current remaining at 10 ms. Mean ± SEM, n = 14. C, Time constant of inactivation as a function of voltage. Mean ± SEM, n = 14.

The extent and kinetics of inactivation of the iberiotoxin-sensitive current were little different in experiments performed in the presence of 5 μm ryanodine or 1 μm thapsigargin [for 10 ms steps to −10 mV; control: time constant, 1.72 ± 0.16 ms to 28 ± 2% (n = 14) of the peak current; ryanodine: time constant, 1.99 ± 0.31 ms (p = 0.38 compared with control) to 30 ± 2% (p = 0.47 compared with control; n = 7); thapsigargin: time constant, 2.20 ± 0.22 ms (p = 0.10 compared with control) to 27 ± 7% (p = 0.94 compared with control; n = 6)].

The inactivation of the iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current during step depolarizations could represent intrinsic inactivation of BK channels. However, it could also be caused in part by the partial inactivation of calcium currents during the depolarization (Fig. 3B). To test whether there is intrinsic inactivation of BK channels, we did a series of experiments in which cells were dialyzed with an internal solution with high calcium (100 μm calcium added with no EGTA) and recorded with no external calcium so that there should be no change in the intracellular calcium during step depolarizations. Interestingly, BK current was completely eliminated under these conditions. A possible interpretation is that BK channels undergo complete inactivation with these levels of intracellular calcium. We attempted to reduce the delay from breakthrough to whole-cell mode to the recording of the currents by step depolarizations, but, even with the shortest delays after breakthrough (∼60 s), there was never any iberiotoxin-sensitive current under these conditions. The apparent inactivation of iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current with increases in intracellular calcium fits well with previous results in which buffering intracellular calcium at 30 μm reduced the magnitude of iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current in Purkinje neurons (Benton et al., 2013) and results in which buffering intracellular calcium at 60 μm resulted in complete inactivation of BK current at voltages depolarized to −100 mV for channels formed by heterologous expression of α + β2 subunits and for native inactivating BK channels in rat adrenal chromaffin cells (Ding and Lingle, 2002). Together, the results leave open the question of how much of the decay of BK current seen under normal conditions might reflect changes in calcium current but suggest that the iberiotoxin-sensitive BK channels in Purkinje neurons can be very effectively inactivated by maintained increases in intracellular calcium. Further studies with low micromolar levels of intracellular calcium might reveal whether the loss of current with 100 μm calcium represents a large shift in the voltage dependence of inactivation such as occurs with β2-containing channels (Ding and Lingle, 2002) or a complete loss of current such as apparently occurs with channels associated with the LINGO1 protein (Dudem et al., 2020).

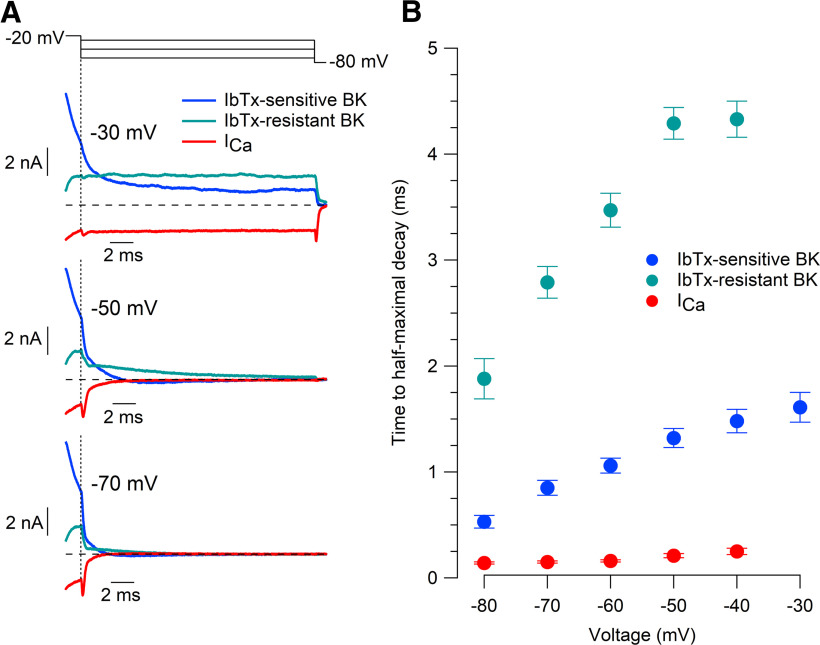

Deactivation kinetics

We also tested the speed with which BK and calcium currents decayed on hyperpolarization. Both components of BK current decayed at faster rates with increasing hyperpolarization, with iberiotoxin-resistant BK current decaying much more slowly than iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current (Fig. 7). Both components of BK current deactivated much more slowly than calcium current. At −70 mV, iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current decayed by half in 0.85 ± 0.07 ms (n = 14), iberiotoxin-resistant BK in 2.79 ± 0.15 ms (n = 15), and calcium current in 0.15 ± 0.01 ms (n = 12).

Figure 7.

Deactivation kinetics of iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current, iberiotoxin-resistant BK current, and calcium current. A, Deactivation of iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current, iberiotoxin-resistant BK current, and calcium current at −30, −50, and −70 mV following activation by a 2.5 ms step to −20 mV. Currents defined as in Figure 3. B, Collected results for deactivation kinetics defined by the time to half-maximal decay. Mean ± SEM: n = 14, IbTx-sensitive BK current; n = 15, IbTx-resistant BK current; n = 12, calcium current.

Deactivation kinetics of both components of BK current were little different in experiments performed in the presence of 5 μm ryanodine (at −70 mV: IbTx-sensitive, 0.86 ± 0.10 ms to half-maximal current, n = 7, p = 0.95 relative to control values; IbTx-resistant, 3.27 ± 0.22 ms to half-maximal current, n = 7, p = 0.08 relative to control) or 1 μm thapsigargin [IbTx-sensitive: 1.00 ± 0.08 ms to half-maximal current (median, 0.94 ms; range, 0.84-1.38 ms), n = 6, p = 0.083 relative to control (Mann–Whitney U test); IbTx-resistant: 3.25 ± 0.29 ms to half-maximal current, n = 6, p = 0.13 relative to control].

BK currents during action potentials

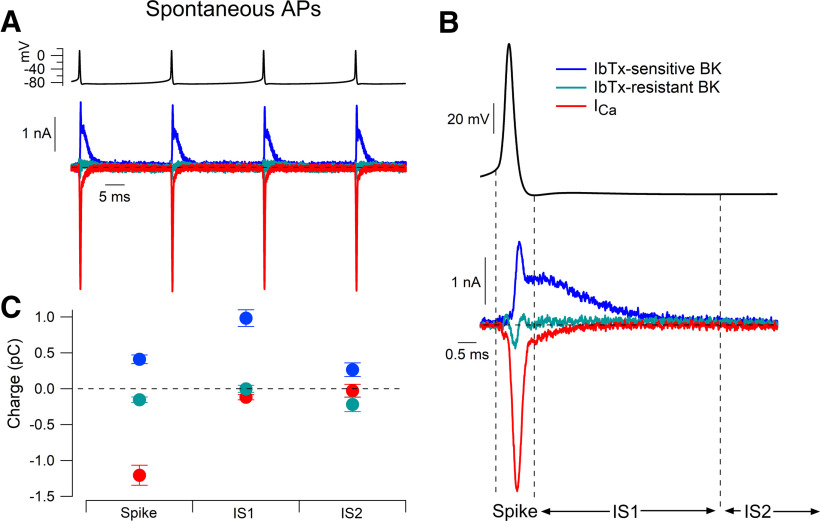

The results so far show that both components of BK current are absolutely dependent on calcium entry through voltage-activated calcium channels but activate (and deactivate) more slowly than calcium channels. We next explored the magnitude and kinetics of the two components of BK current during action potentials, using as voltage-clamp commands records of action potential firing, recorded under the same ionic conditions and at 37°C. We first examined currents evoked by action potentials recorded during spontaneous firing, using the same sequence of solution changes as for voltage step experiments to define iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current, iberiotoxin-resistant BK current, and calcium current (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

BK and calcium currents during action potential waveforms from spontaneous firing. A, Action potentials recorded during spontaneous firing of a Purkinje neuron were used as the command waveform in a voltage-clamp recording. Iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current (blue), iberiotoxin-resistant BK current (green), and calcium current (red) were defined by the application of 200 nm iberiotoxin, 3 μm paxilline, and removal of extracellular calcium as in Figure 3. B, Expanded view of currents during the action potential. C, Collected results for integrated current during the action potential (from the threshold to the fast afterhyperpolarization), in the initial portion of the interspike interval (from the fast afterhyperpolarization to 5 ms later), and the remainder of the interspike interval (from 5 ms after the spike to the threshold of the next spike). Mean ± SEM: n = 15, IbTx-sensitive and IbTx-resistant BK current; n = 12, calcium current.

Calcium current reached a peak during the falling phase of the action potential, with a very small component continuing to flow during the fast afterhyperpolarization (Fig. 8B). No calcium current was detectable for the remaining interspike period leading up to the next action potential in the train. Both during and between action potentials, BK current was entirely from the iberiotoxin-sensitive component. Iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current reached a peak during the late falling phase of the action potential and then remained substantial during the fast afterhyperpolarization and for several milliseconds after the action potential. During the falling phase of the action potential, inward calcium current was always larger than the BK current, but, by the time of the fast afterhyperpolarization, BK current was much larger than calcium current.

Figure 8C shows collected results quantifying current carried by calcium channels and the two components of BK current during the spontaneous firing cycle, dividing the firing cycle into three components: the spike itself (from the threshold to the fast afterhyperpolarization), shortly after the spike (from the fast afterhyperpolarization to 5 ms later) and the remainder of the interspike interval (from 5 ms after the spike to the threshold of the next spike). During the spike, integrated calcium current (−1.21 ± 0.14 pC, n = 12) was much larger than iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current (0.41 ± 0.06 pC, n = 15), with both currents flowing during the falling phase. During the 5 ms period after the spike, iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current was substantial (0.98 ± 0.12 pC, n = 15) and calcium current was much smaller (−0.12 ± 0.04 pC, n = 12). During the remainder of the interspike interval, there was a small amount of iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current (0.16 ± 0.10 pC, n = 15) but almost no calcium current (−0.03 ± 0.09 pC, n = 12). There was no measurable iberiotoxin-resistant current in any of the time intervals. The lack of measurable iberiotoxin-resistant BK current over the entire course of the spontaneous firing cycle was somewhat unexpected given the substantial iberiotoxin-resistant BK current evoked by depolarizing voltage steps. Apparently, activation of the iberiotoxin-resistant channels is too slow, even at 37°C, to produce any activation during the narrow action potentials typical of Purkinje neurons.

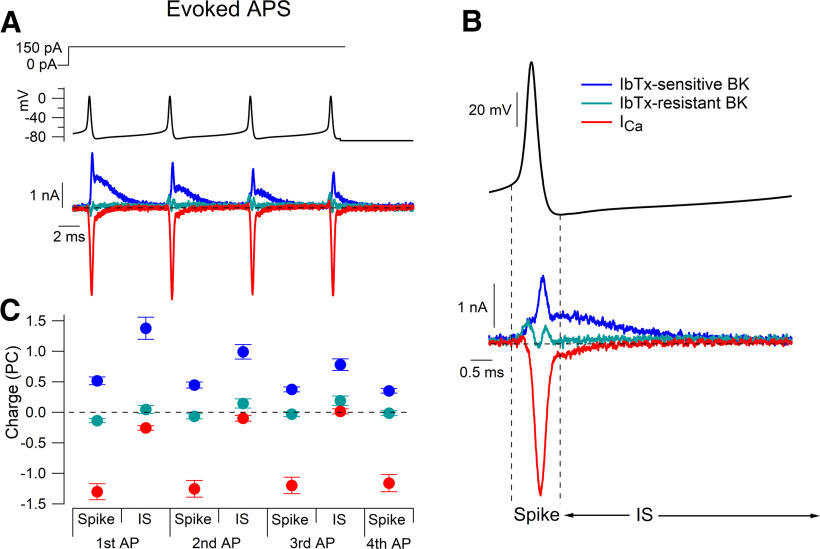

Evoked action potentials

Purkinje neurons can fire simple spikes at frequencies up to 200 Hz both in vivo (Latham and Paul, 1971; Cheron et al., 2018) and with the injection of current in cerebellar slice preparations (Kim et al., 2012) or with acutely dissociated neurons (Khaliq et al., 2003; Carter and Bean, 2011). Figure 9 shows the pattern of BK current and calcium current during the first four action potentials evoked in a Purkinje neuron by current injection that resulted in firing at 134 Hz. With high-frequency evoked firing, the flow of iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current continued for most of the interspike interval. The iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current showed dramatic attenuation in successive action potentials after the onset of firing, consistent with inactivation. From the first spike to the third spike, integrated iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current was reduced on average by 23.2 ± 4.2% (median, 30.3%; range, 11.4–39.5%) during the spike and by 39.5 ± 4.8% (median, 44.7%; range, 2.7–59.6%) during the interspike interval (n = 14). The attenuation of iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current clearly reflects mainly BK channel inactivation because calcium influx changed very little during successive action potentials (integrated current during the spike was reduced by 9.2 ± 1.9% from the first spike to the third spike, n = 12). There was no clear iberiotoxin-resistant current during evoked firing.

Figure 9.

BK and calcium currents during 134 Hz firing evoked by injection of current. A, Action potentials evoked by a 150 pA current injection were used as the command waveform in a voltage-clamp recording. Iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current (blue), iberiotoxin-resistant BK current (green), and calcium current (red) were defined by the application of 200 nm iberiotoxin and 3 μm paxilline, and by the removal of extracellular calcium as in Figure 3. B, Expanded view of currents during the third action potential. C, Collected results for integrated current during the action potential (from the threshold to the fast afterhyperpolarization) and in the interspike interval (from the fast afterhyperpolarization to threshold of the next spike) for each action potential. Mean ± SEM: n = 15, IbTx-sensitive and IbTx-resistant BK current; n = 12, calcium current.

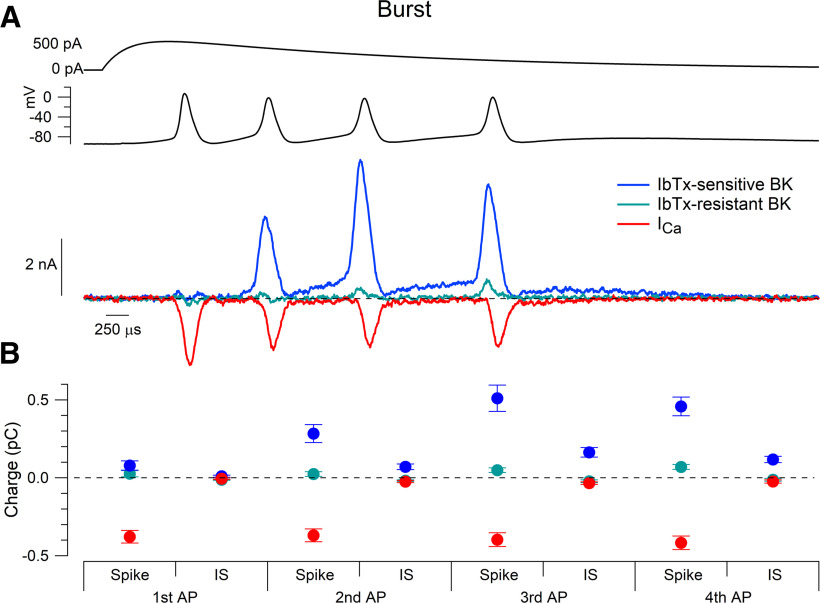

Burst firing

With activation of climbing fibers from the inferior olive, Purkinje neurons fire complex spikes, which are bursts of spikes, and spikelets evoked by a large excitatory postsynaptic potential. Similar burst firing can also be evoked by the injection of current into the cell body (Davie et al., 2008). Figure 10 shows the flow of BK current and calcium current during burst firing evoked by the injection of current designed to mimic a large EPSP. Iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current during burst firing was complex. Iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current was minimal during the first spike but increased as the burst continued. Starting with the third spike, BK current was largest during the spike itself, as if cytoplasmic calcium remained large enough during the interspike intervals that BK channel activation responded almost instantly to voltage, and substantial iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current continued to flow during the interspike intervals. With this waveform, there was a small but detectable component of iberiotoxin-resistant BK current, which flowed during the later spikes but was negligible during the interspike intervals. The iberiotoxin-resistant component of BK current was largest during the fourth spike in the burst, presumably reflecting the buildup of calcium near the channels, but was still very small (0.07 ± 0.02 pC, n = 15) compared with iberiotoxin-sensitive current (0.46 ± 0.06 pC, n = 15).

Figure 10.

BK and calcium currents produced by burst firing. A, Top, A burst of four action potentials elicited by an EPSC-like current injection (see Materials and Methods) was recorded in current clamp and used as the command waveform in voltage-clamp experiments. Bottom, IbTx-sensitive BK, IbTx-resistant BK, and calcium current evoked by burst command waveform. IbTx-sensitive BK current reached its peak value during the third burst spike, whereas calcium current was prominently driven during each action potential. B, Charge measured as current integrated during each spike and interspike interval, including the afterdepolarization following the fourth and last burst spike. Mean ± SEM: n = 15, IbTx-sensitive and IbTx-resistant BK current; n = 12, calcium current.

Delay between calcium influx and BK channel activation

The activation of BK channels during Purkinje neuron action potentials required calcium entry through calcium channels (Fig. 2). In Purkinje neurons, double-immunogold labeling has shown clustered colocalization of Cav2.1 calcium channels with BK channels with a nearest-neighbor distance of ∼40 nm (Indriati et al., 2013), suggesting rapid coupling of BK activation by calcium entry. Our experiments allowed us to directly measure the latency between calcium entry and BK activation at 37°C.

During spontaneous action potentials, calcium current preceded iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current by 108 ± 21 μs (n = 12; Fig. 11A), measured from the times at half of the peak current. With high-frequency evoked firing, there was a similar delay during the first action potential of 105 ± 20 μs (n = 12; Fig. 11B), but the delay became briefer as the evoked train progressed (third evoked AP, 56 ± 34 μs; n = 12; Fig. 11C). The faster onset was accompanied by partial BK activation preceding calcium influx, likely driven by residual calcium from the preceding spike. During burst firing, after the first spike, peak BK current during spikes actually preceded peak calcium current, consistent with residual calcium being sufficient to enable immediate activation of BK channels by the spike depolarization. In the later action potentials during burst firing, large BK currents flowed during the rising phase and peak of the action potential as well as during the falling phase.

The time course of iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current during action potentials seems consistent with activation by calcium entering through voltage-dependent calcium channels, with the delay relative to the calcium current reflecting some combination of the noninstantaneous increase in local intracellular calcium at the BK channels together with the intrinsic kinetics of the BK channels (Cox, 2014). The peak of BK current during the falling phase of the action potential was followed by a plateau of BK current during and immediately after the fast afterhyperpolarization. This plateau of BK current was typically ∼60–70% of the peak BK current and lasted for 0.5–0.7 ms. The plateau of BK current corresponds to a time when local calcium under the plasma membrane is expected to be high and BK channels have not yet deactivated in response to the repolarization of the membrane potential. The subsequent deactivation of BK current after the plateau occurred with a time for half-decay of 1.07 ± 0.06 ms (n = 14). The deactivation of BK current after the spike, when the membrane voltage is near −75 mV, is somewhat slower than the half-decay times for BK current measured during step protocols at similar voltages (0.53 ms at −70 mV, and 0.85 ms at −80 mV) following depolarizing steps to −20 mV (Fig. 7). This may be because peak calcium current during the spike is larger than with the step protocols (Fig. 1), so that more BK channels are in calcium-bound states, which deactivate more slowly (Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002; Zeng et al., 2005).

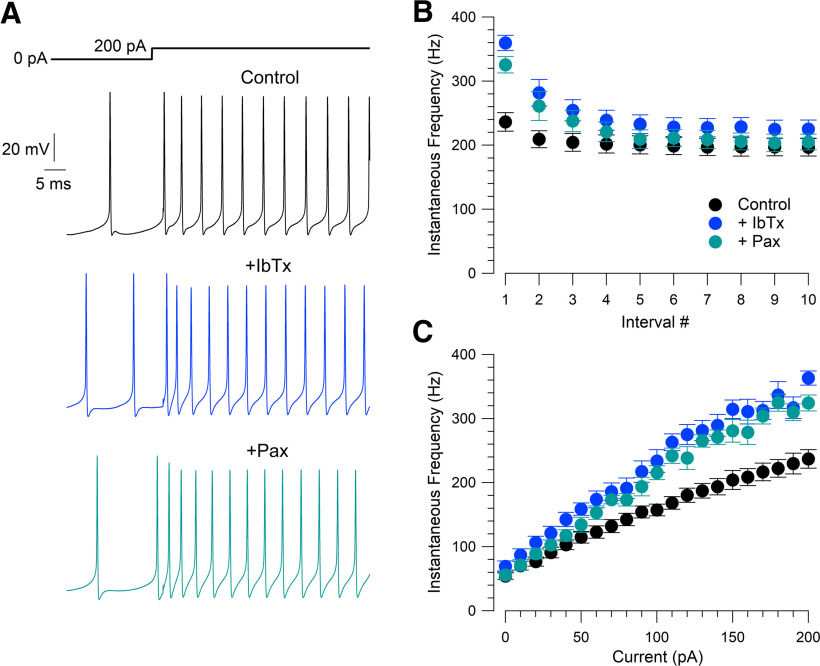

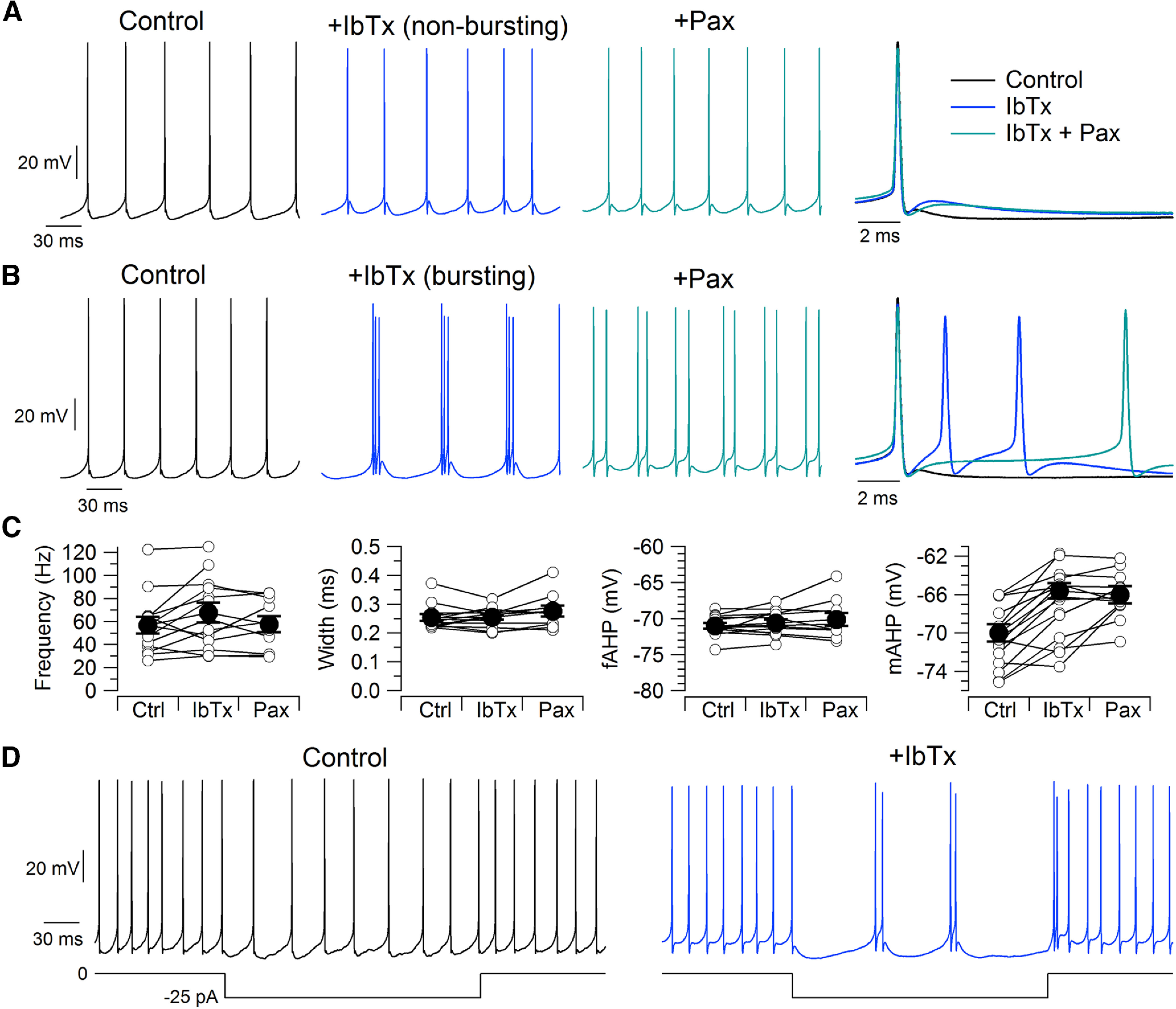

Current clamp

We next tested the effect of inhibiting iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current and iberiotoxin-resistant BK current on action potential shape and firing patterns. We first examined the effect of iberiotoxin and paxilline on action potentials during spontaneous firing (Fig. 12A–C). There was little effect of either iberiotoxin or paxilline on action potential width measured at half-spike amplitude [control: 0.25 ± 0.01 ms (median, 0.24 ms; range, 0.22–0.37 ms), n = 13; IbTx: 0.26 ± 0.01 ms (median, 0.26 ms; range, 0.20–0.32 ms), n = 13; IbTx+Pax: 0.28 ± 0.02 ms (median, 0.27 ms; range, 0.21–0.41 ms), n = 10; control to IbTx, p = 0.960, Wilcoxon signed-rank test; IbTx to IbTx+Pax, p = 0.0313, Wilcoxon signed-rank test)]. There was also little effect on the fast afterhyperpolarization immediately following the spike (control: −72.0 ± 0.4 mV, n = 13; IbTx: −70.6 ± 0.5 mV, n = 13; IbTx+Pax: −70.1 ± 0.9 mV, n = 10; control to IbTx, p = 0.167, paired t test; IbTx to IbTx+Pax, p = 0.682, paired t test), despite the activation of BK channels during the action potential falling phase seen in voltage clamp. The most obvious effect of iberiotoxin was to produce a depolarization of the membrane potential starting shortly after the fast afterhyperpolarization. In control, there was often a second afterhyperpolarization a few milliseconds after the fast afterhyperpolarization. This second afterhyperpolarization often reached slightly more negative voltages than the initial fast afterhyperpolarization, from which it was separated by a depolarizing phase of several millivolts. Iberiotoxin inhibited this second afterhyperpolarization (“medium afterhyperpolarization”), often converting it into an afterdepolarization (control: −70.0 ± 0.9 mV, n = 12; IbTx: −65.8 ± 0.9 mV, n = 12; p = 7.5e-6, paired t test). There was no further effect of the subsequent addition of paxilline (IbTx+Pax: −66.0 ± 0.9 mV, n = 9; IbTx to IbTx+Pax, p = 0.742, paired t test). Similarly, iberiotoxin led to a depolarization of the average membrane potential measured with spikes removed [control: −66.2 ± 0.8 mV (median, −65.6 ms; range, −71.6 to −63.1 ms), n = 13; IbTx: −63.5 ± 0.7 mV, n = 13; IbTx+Pax: −62.9 ± 1.0 mV, n = 10; control to IbTx, p = 0.0005, Wilcoxon signed-rank test; IbTx to IbTx+Pax, p = 0.137, paired t test].

Figure 12.

Iberiotoxin reduces the medium afterhyperpolarization of spontaneous action potentials and can induce bursting. A, Spontaneous firing in control, with 200 nm iberiotoxin, and with 200 nm iberiotoxin plus 3 μm paxilline. Right, Superimposed action potentials in the three conditions. B, In a subset of neurons (6 of 19), iberiotoxin induced spontaneous burst firing. C, Effects of BK inhibition on spontaneous firing rate (n = 13, excluding bursting neurons), spike width (n = 13), the fast afterhyperpolarization (n = 13), and the medium afterhyperpolarization (n = 12). D, Iberiotoxin induction of bursting during injection of −25 pA to hyperpolarize a neuron in which iberiotoxin did not induce bursting during spontaneous firing.

In 6 of 19 neurons tested, iberiotoxin converted the usual spontaneous regular firing of single spikes to firing of bursts of two or three spikes (Fig. 12B). The frequency of firing within a burst was far higher (on average: 251 ± 38 Hz, n = 6) than the frequency of control tonic firing in the same cells before iberiotoxin (on average, 41 ± 10 Hz), while the frequency of the bursts was lower (on average, 22 ± 5 Hz). These bursts are apparently driven by conversion of the medium afterhyperpolarization to an afterdepolarization large enough to reach action potential threshold. In cells in which bursting was not induced, the spontaneous firing frequency was changed only slightly by inhibiting BK channels (control: 57 ± 7 Hz, n = 13; IbTx: 68 ± 9 Hz, n = 13; Pax: 58 ± 7 Hz, n = 10; control to IbTx, p = 0.0610, paired t test; IbTx to IbTx+Pax, p = 0.790, paired t test).

In control, the injection of small negative currents slowed spontaneous firing, with firing continuing to be regular and nonbursting. However, after inhibiting BK channels with iberiotoxin, the firing of many neurons during injection of small negative currents converted to a bursting pattern. This was true of all 6 of the 19 neurons in which iberiotoxin-induced spontaneous bursting without current injection and also of 3 of the 13 neurons in which spontaneous firing in the presence of iberiotoxin continued to be tonic (Fig. 12D). In these three neurons, the intraburst frequency was 167 ± 29 Hz. Thus, inhibiting BK channels induced a propensity for bursting in about half of the neurons.

We next examined Purkinje neuron firing at higher frequencies, evoked by current injections (Fig. 13), confining the analysis to cells in which iberiotoxin did not induce spontaneous bursting. The biggest effect of iberiotoxin was to increase the instantaneous firing frequency at the beginning of the current injection (Fig. 13A,B). The instantaneous firing frequency measured from the first two action potentials evoked by an injection of 200 pA increased from 237 ± 14 Hz in control to 363 ± 11 Hz with 200 nm iberiotoxin (n = 13; p = 4.4e-6, paired t test). The effect decreased with successive action potentials after the beginning of the current injection; measured during the 10th interspike interval, the instantaneous frequency of firing evoked by 200 pA increased from 197 ± 14 Hz in control to 225 ± 14 Hz with iberiotoxin (n = 13; p = 9.6e-5, paired t test). The greater effect of iberiotoxin in the first interspike interval compared with later interspike intervals seems consistent with the partial inactivation of iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current during successive interspike intervals, as seen in the action potential-clamp experiments using evoked spikes as the command waveform (Fig. 9). Because the effect of iberiotoxin on instantaneous frequency reached a steady state within ∼10 spikes, there was only a modest effect of iberiotoxin on average firing frequency during a 200 ms current injection, increasing by ∼16% with the largest current injection tested (200 pA; control: 192 ± 12 Hz, n = 13; IbTx: 222 ± 14 Hz, n = 13; IbTx+Pax: 195 ± 13 Hz, n = 10; control to IbTx, p = 3.0e-5, paired t test; IbTx to IbTx+Pax, p = 0.0981, paired t test).

Figure 13.

Iberiotoxin speeds firing evoked by current injection. A, Firing driven by a 200 pA current injection in control, after 200 nm iberiotoxin, and in 200 nm iberiotoxin plus 3 μm paxilline. B, Instantaneous firing frequency for first 11 action potentials during 200 pA current injections in the three conditions. Mean ± SEM: n = 13, control; n = 13, iberiotoxin; n = 10, paxilline. C, Instantaneous firing frequency for first two action potentials during injection of current from 0 to 200 pA. Mean ± SEM: n = 13, control; n = 13, iberiotoxin; n = 10, paxilline.

Discussion

Our results show that native calcium channels and BK channels in Purkinje neurons activate rapidly at 37°C, both currents activating effectively during the short (∼0.25 ms) action potentials typical of Purkinje neurons. During action potential waveforms, BK current activated with a delay of ∼100 μs after calcium current. Because of this delay—and the narrow action potentials typical of Purkinje neurons—there is a functional separation of BK current from its activating calcium current, with calcium current flowing mostly during the falling phase of the action potential and BK current flowing mostly after full repolarization of the action potential, when calcium channels have deactivated. As a result, the functional role of the BK current is to regulate membrane voltage for several milliseconds after spike repolarization, contributing to a delayed afterhyperpolarization that was often converted to an afterdepolarization when BK channels were inhibited, frequently leading to bursting.

Action potentials in dissociated Purkinje neurons (width, ∼0.25 ms at 37°C) are very similar to those recorded in cerebellar slices (0.15–0.33 ms at 35°C; McKay and Turner, 2004; Hurlock et al., 2008; Womack et al., 2009; Chopra et al., 2018), suggesting that the timing of BK channel activation is similar in both. The flow of BK current late in the repolarization and after the action potential is consistent with the effects of BK inhibitors on spike waveforms of intact Purkinje neurons, with no change in spike width measured at 50% spike amplitude but substantial effects on the afterhyperpolarization (Edgerton and Reinhart, 2003; Sausbier et al., 2004; Womack et al., 2009). The increased propensity for burst firing after BK inhibition also fits well with previous results with Purkinje neurons in cerebellar slice recordings (Sausbier et al., 2004; Haghdoost-Yazdi et al., 2008; Womack et al., 2009).

Timing of calcium current–BK current coupling

In many neurons and heterologous expression systems, the response to intracellular calcium buffers suggests that BK channels and calcium channels must be colocalized (Marrion and Tavalin, 1998; Berkefeld et al., 2006; Loane et al., 2007; Müller et al., 2007; Marcantoni et al., 2010; Berkefeld and Fakler, 2013; Vivas et al., 2017), with estimates that BK channels are within 10–20 nm of calcium channels in cortical neurons (Müller et al., 2007). In Purkinje neurons, BK channel activation is coupled to calcium entry through P-type (Cav2.1) calcium channels (Edgerton and Reinhart, 2003; Womack et al., 2004) and immunoelectron microscopy shows coclusters of BK channels and Cav2.1 channels in the soma and proximal dendrite, with median distances of ∼40 nm between the two channels (Indriati et al., 2013).

Interestingly, native iberiotoxin-sensitive BK channels in Purkinje neurons activate substantially faster (for a step to 0 mV, time to half-peak of 0.6 ms, with a delay of 0.25 ms relative to calcium current) than in a sophisticated model of Cav2.1/BK channel gating (Cox, 2014) based on kinetics of heterologously expressed Cav2.1 and BK channels (formed by α-subunits alone), predicting a time to half-peak BK current of 1.8 ms, with a delay of 1.2 ms relative to the calcium current. The faster kinetics of native Purkinje neuron channels, which could reflect altered gating conferred by alternative splicing, β-subunits, or post-translational modification (Shipston and Tian, 2016; Latorre et al., 2017; Kshatri et al., 2018; Gonzalez-Perez and Lingle, 2019), seem critical for their functional role, because in the model there would be almost no activation of the heterologously expressed α-subunit-only channels by the narrow (width, ∼ 0.25 ms) action potentials in Purkinje neurons.

Like Purkinje neurons, hippocampal mossy fiber boutons (MFBs) have narrow action potentials repolarized primarily by fast-activating Kv3 channels, with BK channels activating too slowly to contribute to repolarization (Alle et al., 2011). In contrast to Purkinje neurons, however, action potential-clamp recordings in MFBs showed no activation of BK current even during the afterhyperpolarization, although BK current could be activated by 4-AP-broadened action potentials or when resting intracellular calcium was increased (Alle et al., 2011). The lack of any BK activation by normal MFB action potentials may reflect slower activation of BK current compared with Purkinje neurons resulting from increased distance from calcium channels, as suggested by the ability of EGTA to prevent BK channel activation in MFBs (Alle et al., 2011). It would be interesting to compare the speed and timing of BK current relative to calcium current in other kinds of neurons with broader action potentials or where BK current is coupled to different types of calcium channels (Marrion and Tavalin, 1998; Prakriya and Lingle, 1999, 2000; Shao et al., 1999; Berkefeld and Fakler, 2008; Marcantoni et al., 2010; Vandael et al., 2010; Vivas et al., 2017; Whitt et al., 2018; Gutzmann et al., 2019).

Iberiotoxin-resistant BK channels

Total BK current induced by step depolarizations included a sizeable component of iberiotoxin-resistant BK current (on average ∼25% of total BK current at −20 mV) with the slow kinetics of activation and deactivation expected from β4-containing channels (Wang et al., 2014), fitting with a previous demonstration of iberiotoxin-resistant BK current (Benton et al., 2013) and the expression of β4 subunits (Petrik and Brenner, 2007; Pratt et al., 2017) in Purkinje neurons. Remarkably, however, these channels produced only tiny currents during somatic action potential firing, even during high-frequency and burst firing, apparently because their slow activation kinetics preclude activation by action potentials. Accordingly, paxilline had no further effect on firing patterns in current clamp when added on top of iberiotoxin. Thus, the functional role of iberiotoxin-resistant channels is puzzling. They might be important in regulating dendritic depolarizations involving larger and more sustained calcium entry (Cavelier et al., 2002; Canepari and Ogden, 2006; Ait Ouares et al., 2019), although β4-containing clusters of BK channels appear to be enriched in the somatic membrane (Kaufmann et al., 2009). Possibly the somatic β4-containing clusters of BK channels could have a nonelectrical role related to their localization in plasma membrane near endoplasmic reticulum (Pratt et al., 2017), analogous to Kv2.1 channels in other neuronal types (Vierra et al., 2019). The iberiotoxin-resistant BK current might also serve as a safety mechanism to help control membrane potential with pathophysiologically large and sustained entry of calcium beyond that during normal firing.

Inactivation of iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current

Our results add to previous results (Benton et al., 2013) showing that iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current in Purkinje neurons inactivates rapidly during depolarizing steps, inactivating by ∼70% at 0 mV with strongly temperature-dependent kinetics (τ: 5.3 ms at ∼23°C, 2.5 ms at ∼32°C, and 1.8 ms at 37°C; Benton et al., 2013; Fig. 6). The rapid inactivation at 37°C results in substantial inactivation during high-frequency firing (reduction by ∼35% in three action potential waveforms at 134 Hz; Fig. 9), despite the brief duration of action potentials.

Functionally, the partial inactivation of BK current has the effect of shortening successive interspike intervals during high-frequency action potentials evoked by current injection. This appears to counteract other influences that result in a lengthening of successive interspike intervals, seen when BK current is inhibited, so that with BK present there is less spike-frequency adaptation. It is also possible that BK channel inactivation per se is less significant than changes in calcium dependence, voltage dependence, and kinetics produced by the accessory subunits conferring inactivation, as in chromaffin cells (Sun et al., 2009; Lingle et al., 2018). For example, the β2 subunit confers both rapid inactivation and enhanced calcium sensitivity (Wallner et al., 1999; Xia et al., 2000; Gonzalez-Perez and Lingle, 2019).

The molecular basis of the inactivation of iberiotoxin-sensitive BK current in Purkinje neurons remains to be determined. The very rapid inactivation kinetics are reminiscent of those conferred by β3b subunits (Xia et al., 2000) and by LINGO1 proteins, which are present in Purkinje cell somata (Kuo et al., 2013) and coimmunoprecipitate with BKα proteins in human cerebellar lysates (Dudem et al., 2020). Interestingly, the complete loss of iberiotoxin-sensitive current we saw in Purkinje neurons dialyzed with high (100 μm) calcium parallels the abolition of current from heterologously expressed BKα–LINGO1 channels by high intracellular calcium (Dudem et al., 2020).

Relation to in vivo firing

BK channels in Purkinje neurons are critical for normal function, as Purkinje neuron-specific ablation produces ataxia (Chen et al., 2010). Our results showing control of burst firing by activation of BK current in the first few milliseconds after a spike fits well with those of a recent study of in vivo changes in Purkinje neuron firing resulting from selective deletion of BK channels in Purkinje neurons (Cheron et al., 2018), showing episodes of rapid bursting distinct from complex spikes. In fact, the intraburst firing frequency of ∼200 Hz is similar to the typical intraburst frequency we saw in the presence of iberiotoxin either spontaneously or during the injection of small hyperpolarizing currents. Purkinje neurons have an inherent propensity for firing action potentials in rapid bursts, partly because of resurgent sodium current, which flows immediately after an action potential (Raman and Bean, 1997; Khaliq et al., 2003), along with a large persistent sodium current that is significantly activated at postspike voltages near −70 mV (Carter et al., 2012), and partly because the dominant potassium current mediating spike repolarization is mediated by Kv3 channels (McKay and Turner, 2004; Akemann and Knöpfel, 2006; Martina et al., 2007: Zagha et al., 2008), which deactivate very rapidly, enabling rapid generation of a subsequent action potential. Thus, the BK current immediately following a spike is apparently important for controlling the propensity for burst firing, so that under normal circumstances Purkinje neurons fire tonic single spikes.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants NS-036855 and NS-110860. We thank Brett Carter for preliminary results that guided the experiments.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Ait Ouares K, Filipis L, Tzilivaki A, Poirazi P, Canepari M (2019) Two distinct sets of Ca2+ and K+ channels are activated at different membrane potentials by the climbing fiber synaptic potential in Purkinje neuron dendrites. J Neurosci 39:1969–1981. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2155-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akemann W, Knöpfel T (2006) Interaction of Kv3 potassium channels and resurgent sodium current influences the rate of spontaneous firing of Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci 26:4602–4612. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5204-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alle H, Kubota H, Geiger JR (2011) Sparse but highly efficient Kv3 outpace BKCa channels in action potential repolarization at hippocampal mossy fiber boutons. J Neurosci 31:8001–8012. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0972-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey CS, Moldenhauer HJ, Park SM, Keros S, Meredith AL (2019) KCNMA1-linked channelopathy. J Gen Physiol 151:1173–1189. 10.1085/jgp.201912457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton MD, Lewis AH, Bant JS, Raman IM (2013) Iberiotoxin-sensitive and -insensitive BK currents in Purkinje neuron somata. J Neurophysiol 109:2528–2541. 10.1152/jn.00127.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkefeld H, Fakler B (2008) Repolarizing responses of BKCa-Cav complexes are distinctly shaped by their cav subunits. J Neurosci 28:8238–8245. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2274-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkefeld H, Fakler B (2013) Ligand-gating by Ca2+ is rate limiting for physiological operation of BK(ca) channels. J Neurosci 33:7358–7367. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5443-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkefeld H, Sailer CA, Bildl W, Rohde V, Thumfart JO, Eble S, Klugbauer N, Reisinger E, Bischofberger J, Oliver D, Knaus HG, Schulte U, Fakler B (2006) BKCa-Cav channel complexes mediate rapid and localized Ca2+-activated K+ signaling. Science 314:615–620. 10.1126/science.1132915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkefeld H, Fakler B, Schulte U (2010) Ca2+-activated K+ channels: from protein complexes to function. Physiol Rev 90:1437–1459. 10.1152/physrev.00049.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny I, Watras J, Ehrlich BE (1991) Bell-shaped calcium-response curves of Ins(1,4,5)P3- and calcium-gated channels from endoplasmic reticulum of cerebellum. Nature 351:751–754. 10.1038/351751a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner R, Chen QH, Vilaythong A, Toney GM, Noebels JL, Aldrich RW (2005) BK channel beta4 subunit reduces dentate gyrus excitability and protects against temporal lobe seizures. Nat Neurosci 8:1752–1759. 10.1038/nn1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canepari M, Ogden D (2006) Kinetic, pharmacological and activity-dependent separation of two Ca2+ signalling pathways mediated by type 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors in rat Purkinje neurones. J Physiol 573:65–82. 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BC, Bean BP (2009) Sodium entry during action potentials of mammalian neurons: incomplete inactivation and reduced metabolic efficiency in fast-spiking neurons. Neuron 64:898–909. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BC, Bean BP (2011) Incomplete inactivation and rapid recovery of voltage-dependent sodium channels during high-frequency firing in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurophysiol 105:860–871. 10.1152/jn.01056.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BC, Giessel AJ, Sabatini BL, Bean BP (2012) Transient sodium current at subthreshold voltages: activation by EPSP waveforms. Neuron 75:1081–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavelier P, Pouille F, Desplantez T, Beekenkamp H, Bossu JL (2002) Control of the propagation of dendritic low-threshold Ca2+ spikes in Purkinje cells from rat cerebellar slice cultures. J Physiol 540:57–72. 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Kovalchuk Y, Adelsberger H, Henning HA, Sausbier M, Wietzorrek G, Ruth P, Yarom Y, Konnerth A (2010) Disruption of the olivo-cerebellar circuit by Purkinje neuron-specific ablation of BK channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:12323–12328. 10.1073/pnas.1001745107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]