Abstract

Gene transfers from mitochondria and plastids to the nucleus are an important process in the evolution of the eukaryotic cell. Plastid (pt) gene losses have been documented in multiple angiosperm lineages and are often associated with functional transfers to the nucleus or substitutions by duplicated nuclear genes targeted to both the plastid and mitochondrion. The plastid genome sequence of Euphorbia schimperi was assembled and three major genomic changes were detected, the complete loss of rpl32 and pseudogenization of rps16 and infA. The nuclear transcriptome of E. schimperi was sequenced to investigate the transfer/substitution of the rpl32 and rps16 genes to the nucleus. Transfer of plastid-encoded rpl32 to the nucleus was identified previously in three families of Malpighiales, Rhizophoraceae, Salicaceae and Passifloraceae. An E. schimperi transcript of pt SOD-1-RPL32 confirmed that the transfer in Euphorbiaceae is similar to other Malpighiales indicating that it occurred early in the divergence of the order. Ribosomal protein S16 (rps16) is encoded in the plastome in most angiosperms but not in Salicaceae and Passifloraceae. Substitution of the E. schimperi pt rps16 was likely due to a duplication of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial-targeted rps16 resulting in copies dually targeted to the mitochondrion and plastid. Sequences of RPS16-1 and RPS16-2 in the three families of Malpighiales (Salicaceae, Passifloraceae and Euphorbiaceae) have high sequence identity suggesting that the substitution event dates to the early divergence within Malpighiales.

Subject terms: Plant sciences, Plant evolution

Introduction

Plastids evolved from endosymbiosis of a cyanobacterium1. Since the primary and secondary endosymbiotic events a tremendous number of genes have transferred to the nucleus of the host cell or have been lost entirely from the plastid genome (plastome)2.

Most angiosperm plastomes have a highly conserved gene content ranging between 120 and 130 genes out of the approximately 1000–8000 genes that were present in the cyanobacterial ancestor3. There are some exceptions in various lineages including losses/transfers of infA in most rosids4, 5, rpl33 in some legume lineages6, 7, rpl32 in Salicaceae8–11, Rhizophoraceae10, Ranunculaceae12, Passifloraceae13, 14 and Euphorbiaceae15–17, rps16 in various legumes6, 18–21, Salicaceae8, 9, 22, Passifloraceae14 and Euphorbiaceae15–17, 23–25, rpl22 in Fabaceae, Fagaceae, Passifloraceae, and Salicaceae13, 14, 26, 27 and rpl20 in Passifloraceae14.

Gene loss from the plastome in angiosperms is an ongoing process2, 28. The missing plastid genes carry out important roles and their fate has been explained by two possible mechanisms that have been verified by experimental and/or bioinformatic approaches. They have been either transferred to the nuclear genome such as rpl32, rpl22, rps7, rpoA and infA4, 10–12, 14, 26, 27, 29, substituted by a dual targeted nuclear-encoded mitochondrial gene such as rps16 in Medicago truncatula (Fabaceae), Populus alba (Salicaceae) and Passifloraceae14, 22, or substituted by a nuclear-encoded mitochondrial gene such as accD in grasses30, rpl23 in spinach and Geranium (Geraniaceae)31, 32 and rpl20 in Passifloraceae14.

Numerous nuclear-encoded gene products are required to return to the plastid to maintain the same level of metabolic complexity of the ancestral cyanobacteria33. A considerable number of proteins are targeted back to the plastid as pro-proteins, which are inactive proteins that can be converted into an active form that requires a N-terminal extension called a transit peptide34. In order for plastid gene transfers to be successful, the gene must gain elements of nuclear expression and acquire a N-terminal transit peptide2, 35. Transit peptide acquisition by exon shuffling of an existing nuclear-encoded plastid targeted gene has been identified; for example, in Populus, the transit peptide of rpl32 was acquired by exon shuffling of a duplicated copy of the Cu–Zn superoxide dismutase gene (SOD1)11. A novel transit peptide that was acquired by exon shuffling of unknown nuclear-encoded plastid gene has been identified in Ranunculaceae (Thalictrum and Aquilegia)12.

In order for a plastid gene to be successfully substituted by a nuclear-encoded organelle targeted gene, the upstream (N-terminal) portion of mature protein has to be dually targeted to organelles by one of the following mechanisms: alternative transcriptional initiation36, alternative translational initiation37, 38 or ambiguous targeting information within N-terminal extension sequences39. Comparison of the nuclear copy of RPS16 in angiosperms to RPS16 in E.coli showed that dual targeting to the organelles occurred without acquiring a N-terminal extension sequence upstream of the mature protein. For instance, in Populus alba and Medicago truncatula, the RPS16 nuclear copy has gained targeting information within its mature protein without having a N-terminal extension sequence22.

Two genes, rpl32 and rps16, have been characterized as being lost in plastomes and either transferred to the nucleus or substituted by a nuclear-encoded mitochondrially-targeted gene in three families of Malpighiales, Rhizophoraceae, Salicaceae and Passifloraceae10, 11, 14, 22. The fate of these two missing genes in other families of Malpighiales (Bonnetiaceae, Hypericaceae, Clusiaceae, Podostemaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Malpighiaceae, Chrysobalanaceae, Irvingiaceae, Pyllanthaceae, Erythoxylaceae, Linaceae and Violaceae) has not been characterized15–17, 23–25, 40–46. Thus, little is known about the extent of the transfer/substitution of these genes in other families of Malpighiales.

Euphorbiaceae include approximately 6745 species organized into 218 genera and four subfamilies47. It is one of the largest families of angiosperms and contains at least ten species that exhibit promising anticancer activity48, 49. Euphorbia contains over 2000 species, making it one of the largest genera of flowering plants50. The genus has unique floral features with a specialized inflorescence, the cyathium, and contains latex in its vegetative parts51. The primary purpose of this sap is to protect plants from herbivores and it has been used as anti-inflammation, antiangiogenic, antibacterial and to treat cancer52. Euphorbia is an important component of arid ecosystems because its succulent stems use CAM photosynthesis, which plays an important role in adapting to arid conditions. The diversification of Euphorbia is due, at least in part, to the presence of CAM in the succulent stems53.

Previous estimates place the origin and time of divergence of Euphorbia in Africa roughly 48 million years ago and it subsequently expanded to the Americas through two long distance dispersal events approximately 30 and 25 million years ago53. Euphorbia schimperi C. Presl belongs to subgenus Esula and it grows mainly as a succulent shrub in rocky environments of open savannahs. Euphorbia schimperi is a perennial plant reaching heights of 1.2–1.8 m with tiny ephemeral leaves and pencil-like succulent photosynthetic stems (https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/taxa/343121-Euphorbia-schimperi/browse_photos)54. The species is distributed in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula in Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, Socotra as well as east Africa (Ethiopia, Eritrea)53, 55. Among the more than 2000 species of Euphorbia E. schimperi is especially important because it is known to have anti-breast and brain cancer properties56.

Only 21 species of Euphorbiaceae have complete plastome sequences available in NCBI (accessed on Feb 13, 2021) with ten Euphorbia species published and most of these are economically important and have some medicinal activities due to the presence of isoprenoids15–17, 23–25, 46, 57–64. Using next generation sequencing technologies and de novo assembly, the plastome and nuclear transcriptome of Euphorbia schimperi was sequenced. The primary objectives are to examine the fate of the two plastid genes, rpl32 and rps16, that have been lost and plot the phylogenetic distribution of these plastid gene losses/transfers/substitutions across the Malpighiales.

Results

General features of Euphorbia schimperi plastome

The Euphorbia schimperi plastome had a length of 159,462 base pairs (bp) with a pair of inverted repeats (IR) of 26,629 bp, which separate the large single copy (LSC, 88,904 bp) and small single copy (SSC, 17,300 bp) regions (Fig. S1, accession number MT900567). Mapping raw reads to the plastome indicated that the average coverage was 1157×. The genome included a total of 128 genes (17 in IR) including 4 rRNAs (all in IR), 30 tRNAs (7 in IR) and 77 protein-coding genes (6 in IR). The plastome of Euphorbia schimperi had three putative gene losses, translation initiation factor 1 (infA), ribosomal protein L32 (rpl32) and ribosomal protein S16 (rps16).

Alignment of the pseudogene of rps16 of E. schimperi with intact rps16 of Manihot esculenta revealed a 5-bp deletion, 10 bp insertion and 27 nucleotide substitutions within exon 2 causing a frameshift (Fig. S2A). A 250 bp deletion, 11 bp insertion and 338 nucleotide substitutions in the intron of E. schimperi caused nearly complete loss of the intron and entire loss of exon 1 (Fig. S2B). In rosid plastomes, infA is usually located between rpl36 and rps8 with length of about 234 bp. The alignment of the infA pseudogene of E. schimperi with intact infA of Brexia madagascariensis revealed a 3-bp deletion, 10 bp insertion and 69 nucleotide substitutions causing a frameshift (Fig. S3). Plastid rpl32, which is usually located between ndhF and trnL-UAG and ranges between 150 and 171 bp, was completely missing from the plastome of E. schimperi.

Assembly of Euphorbia schimperi transcriptome and quality assessment

The sequenced Illumina libraries yielded 80,916,952 reads. The total reads used, number of assembled contigs and N50 statistics are in Table 1. Mapped read coverage to the assembly using Bowtie265 was 90.26% (73,033,718 reads). BUSCO indicated that the transcriptome assembly covered 87% and 72.3% of conserved single-orthologs of 100 species of eukaryotes (BUSCOs: 303) and 30 species of embryophytes (BUSCOs: 1440), respectively. Amino acid sequences of the candidate ORFs from the E. schimperi transcriptome were used to identify pt rpl32 and rps16 genes in the nucleus. Statistics of Trinity translated transcriptome assembly are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1.

Statistics of Trinity transcriptome assembly.

| Total length of sequence | 231,194,199 bp |

| Total number of contigs | 311,629 |

| N25 | 22,235 sequences ≥ 1870 bp |

| N50 | 62,276 sequences ≥ 1127 bp |

| N75 | 134,642 sequences ≥ 560 bp |

| Max contig length | 14,119 bp |

| Mean contig length | 742 bp |

| Total GC count | 94,624,984 bp |

| GC% | 40.93% |

Identification of gene transfers and substitution to the nucleus

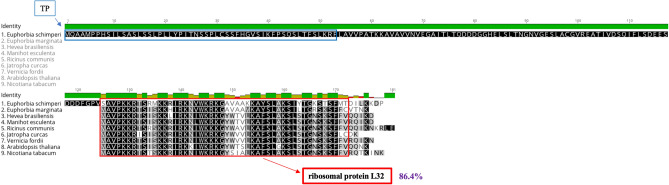

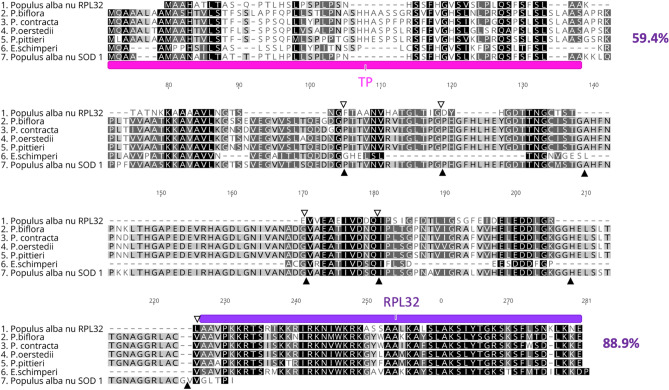

Nuclear-encoded RPL32 with high amino acid (aa) sequence identity (82.6%) was detected in the E. schimperi transcriptome with upstream sequences of 124 bp from the conserved ribosomal protein L32. Pairwise amino acid sequence identity of the conserved domain of nuclear-encoded RPL32 of E. schimperi and pt-encoded copies in Euphorbiaceae species was 86.4% (Fig. 1). The length of nuclear-encoded RPL32 in E. schimperi was ~ 179 aa, 55 aa of which represented the conserved domain. This length was similar to the plastid-encoded RPL32 in Manihot esculenta (53 aa), Ricinus communis (57 aa), Hevea brasiliensis (53 aa), Vernicia fordii (53 aa), Jatropha curcas (50 aa), Euphorbia marginata (52 aa), Arabidopsis thaliana (52 aa) and Nicotiana tabacum (55 aa). TargetP and LOCALIZER analyses of upstream sequences of the ribosomal protein L32 domain strongly predicted a plastid targeted transit peptide (TP) (0.92–1.0). BLAST search (BLASTp) of the TP against NCBI revealed 49–63% aa sequence identity to the cp superoxide dismutase [Cu–Zn] gene (SOD1) of multiple Malpighiales including Euphorbiaceae [J. curcas (63%), M. esculenta (61%), H. brasiliensis (56%) and R. communis (49%)], Rhizophoraceae [Kandelia candel (52%)] and Salicaceae [Populus alba (57%) and Populus trichocarpa (55%)]. Pairwise aa sequence identity of nuclear-encoded RPL32 from E. schimperi, Populus alba, Passiflora (P. biflora, P. contracta, P. oerstedii and P. pittieri) and nuclear-encoded SOD-1 of Populus alba was 59.4% and 88.9% for transit peptide and the ribosomal protein L32 conserved domain, respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Multiple alignments of nuclear RPL32 of Euphorbia schimperi and plastid RPL32 of other Euphorbiaceae (E. marginata, Jatropha curcas, Hevea brasiliensis, Manihot esculenta, Ricinus communis, Vernicia fordii), Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum. Blue box indicates plastid transit peptide (TP) predicted using LOCALIZER (~ 53 aa). Red box indicates a conserved domain of RPL32. Pairwise amino acid sequence identity of the conserved domain of nuclear-encoded RPL32 of E. schimperi and pt-encoded copies in Euphorbiaceae species and Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum was 86.4%.Green histogram indicates amino acid sequence identity.

Figure 2.

Alignment of the amino acids of nuclear RPL32 of Euphorbia schimperi, Populus alba (BAF80584.1), Passiflora biflora; (QKY65178.1), P. contracta; (QKY65180.1), P. oerstedii; (QKY65177.1) and P. pittieri; (QKY65179.1) and Populus alba nuclear SOD-1(BAF80585.1). Pink annotation indicates plastid transit peptide of SOD-1 in Populus. Purple annotation indicates a conserved domain of RPL32 in Populus. Open and filled triangles indicate the position of introns in the cp rpl32 and cp sod-1 genes in Populus (Ueda et al. 2007). Pairwise aa sequence identity of nuclear-encoded RPL32 from E. schimperi, Populus alba, Passiflora (P. biflora, P. contracta, P. oerstedii and P. pittieri) and nuclear-encoded SOD-1 of Populus alba was 59.4% and 88.9% for transit peptide and the ribosomal protein L32 conserved domain, respectively. Gaps are indicated by dashes.

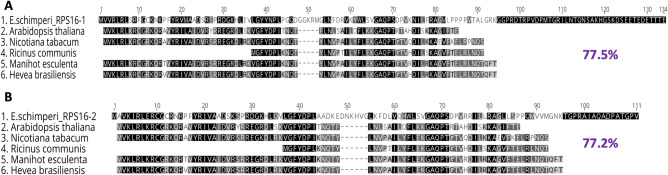

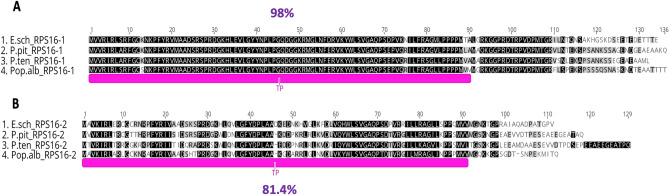

Two transcripts of nuclear-encoded RPS16 were detected in the E. schimperi transcriptome. Pairwise aa sequence identity of the two E. schimperi transcripts (RPS16-1 and RPS16-2) with other Euphorbiaceae, Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum was 77.2% and 77.5% (Fig. 3A,B). The lengths of nuclear-encoded RPS16-1 and RPS16-2 in E. schimperi were 134 aa and 111 aa, respectively, and both were longer than the plastid-encoded RPS16 in M. esculenta (88 aa), R. communis (50 aa), H. brasiliensis (88 aa), Arabidopsis thaliana (79 aa) and Nicotiana tabacum (85 aa) (Fig. 3A,B). Alignment of the upstream sequences of RPS16-1 and RPS16-2 of E. schimperi to the transit peptides of RPS16-1 and RPS16-2 of Passiflora pittieri, P. tenuiloba and Populus alba resulted in aa identities of 98% and 81.4%, respectively (Fig. 4A,B). A BLAST search (BLASTp) of RPS16-1 against NCBI resulted in sequence identity matches with chloroplastic/mitochondrial 30S ribosomal protein S16-1 for multiple species of Malpighiales including Euphorbiaceae [Manihot esculenta (80%), Hevea brasiliensis (79%), Jatropha curcas (63%)], Passifloraceae [Passiflora tenuiloba (78.12%), P. oerstedii (78%), P. pittieri (77.44%)] and other angiosperm lineages, whereas RPS16-2 matched with chloroplastic/mitochondrial 30S ribosomal protein S16-2 of multiple species of Malpighiales including Euphorbiaceae [Manihot esculenta (81%), Hevea brasiliensis (80%), Jatropha curcas (85%)], Passifloraceae [Passiflora oerstedii (62%)] and Salicaceae [Populus trichocarpa (76%), P. alba (76%) and P. euphratica (62%)].

Figure 3.

(A) Alignments of nuclear RPS16-1 of Euphorbia schimperi and plastid RPS16 of other Euphorbiaceae (Manihot esculenta, Hevea brasiliensis, Ricinus communis), Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum. (B) Alignments of nuclear RPS16-2 of Euphorbia schimperi and plastid RPS16 of other Euphorbiaceae (Manihot esculenta, Hevea brasiliensis, Ricinus communis), Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum. Pairwise aa sequence identity of the two E. schimperi transcripts (RPS16-1 and RPS16-2) with other Euphorbiaceae, Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum was 77.5% and 77.2%, respectively. Gaps are indicated by dashes.

Figure 4.

(A) Alignment of the amino acid sequences of nuclear RPS16-1 of Euphorbia schimperi, Populus alba (RPS16-1: BAG49074.1), Passiflora pittieri; (RPS16-1: QKY65183.1), and P. tenuiloba; (RPS16-1: QKY65187.1). (B) Alignment of the amino acid sequences of nuclear RPS16-2 of Euphorbia schimperi, Populus alba (RPS16-2: BAG49075.1), Passiflora pittieri; (RPS16-2: QKY65185.1), and P. tenuiloba; (RPS16-2: QKY65184.1). Pink annotation indicates plastid transit peptide (TP) predicted in Populus alba (Ueda et al.11). Alignment of the upstream sequences of RPS16-1 and RPS16-2 of E. schimperi to the transit peptides of RPS16-1 and RPS16-2 of Passiflora (P. pittieri and P. tenuiloba) and Populus alba resulted in aa identities of 98 and 81.4%, respectively. Gaps are indicated by dashes.

A nuclear-encoded copy of infA was not found in the transcriptome of E. schimperi.

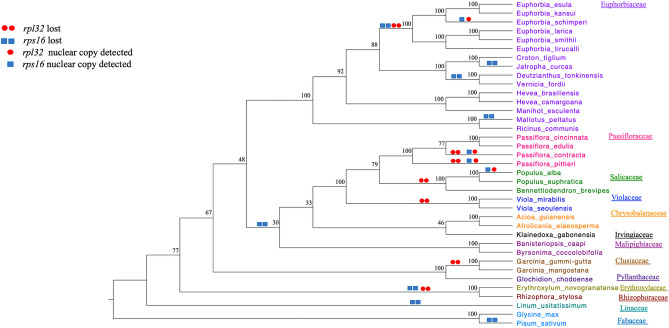

Phylogenetic distribution of rpl32 and rps16 gene losses/transfers/substitutions in Malpighiales

The phylogenetic analysis that included 45 protein-coding plastid genes was performed to generate a tree for plotting the distribution of rpl32 and rps16 gene losses/transfers or substitutions across Malpighiales (Fig. 5). These changes were plotted based on the results of this study and previously published studies, including examination of the plastome sequences on GenBank (Supplementary Table S2). The results indicated that five genera of Euphorbiaceae have representative species that lost rps16, Deutzianthus, Euphorbia, Jatropha, Mallotus and Vernicia, and one genus (Euphorbia) also lost rpl32 (Fig. 5). Since all Euphorbia plastomes do not have intact rpl32 or rps16 these losses likely occurred during the early divergence of the genus. However, the presence of these genes in the nucleus by either a transfer or substitution event has only been documented in E. schimperi. Some members of other Malpighiales families have experienced the loss of rpl32 and/or rps16 from their plastomes, including Passifloraceae, Salicaceae, Violaceae, Erythoxylaceae and Rhizophoraceae, whereas Chrysobalanaceae, Irvingiaceae, Malpighiaceae and Linaceae are missing only rps16 and Clusiaceae is missing only rpl32. The fate of these gene losses has only been determined in Passiflora and Populus with rpl32 transferred to the nucleus and rps16 substituted in selected species in both genera (Fig. 5)11, 14, 22.

Figure 5.

ML cladogram of 37 taxa (Supplemental Table S2) based on 45 plastid gene sequences (Supplemental table S3). Numbers at node are bootstrap values.

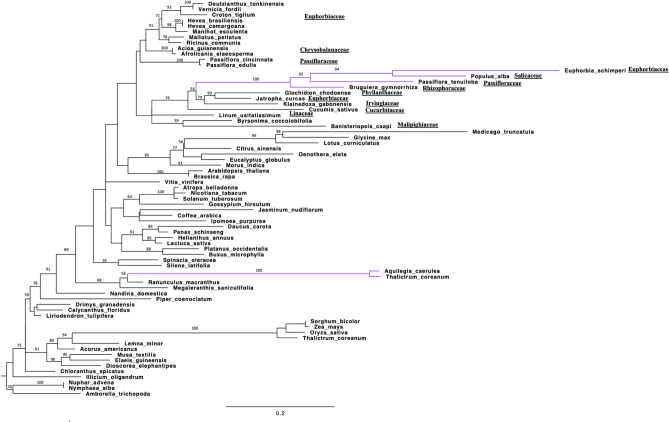

Phylogenetic analysis of the second data set included sequences of the rpl32 gene for 71 species, 65 encoded in the plastid and six in the nucleus. In the resulting phylogram (Fig. 6) the nuclear copy of E. schimperi grouped with nuclear copies from the three families Salicaceae (Populus alba), Passifloraceae (Passiflora tenuiloba) and Rhizophoraceae (Bruguiera gymnorhiza). The four species with genes encoded in the nucleus were in a clade of plastid copies from three species in different families of Malpighiales (Euphorbiaceae, Irvingiaceae, Phyllanthaceae) and Cucurbita in the Cucurbitales. All other plastid encoded rpl32 sequences of Malpighiales occurred in a separate clade that was sister to the clade the included the nuclear-encoded copies. Branch lengths of the nuclear-encoded rpl32 genes from E. schimperi, Populus, Passiflora and Bruguiera were much longer than in the plastid-encoded copies.

Figure 6.

ML phylogram of 71 taxa based on rpl32 gene sequences. Nuclear copies of rpl32 are indicated bold purple color. Bootstrap support values > 50% are shown at nodes. Scale bar indicates a phylogenetic distance of 0.2 nucleotide substitutions per site.

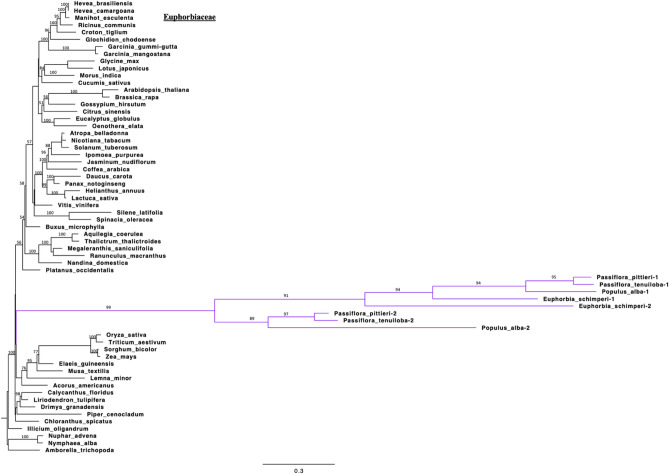

Phylogenetic analysis of the third data set included sequences of the rps16 gene for 63 species, 55 encoded in the plastid and 8 copies of 4 nuclear genes. In the resulting phylogram (Fig. 7) the nuclear copies of E. schimperi grouped with nuclear copies from the two families Salicaceae (Populus alba), Passifloraceae (P. tenuiloba and P. pittieri) in a distant position from plastid encoded copies of Euphorbiaceae. The nuclear-encoded copies resolved as a clade at the base of the eudicots, far removed from plastid-encoded copies of Malpighiales. The long branches of the nuclear-encoded copies of rpl32 and rps16 are indicative of the faster substitution rates observed in the nuclear than the plastid genomes66. There is some uncertainty in the resolution of the clades due to poor support (bootstrap percentages mostly < 60) among deeper nodes and the artifacts due to long branch attraction.

Figure 7.

ML phylogram of 60 taxa based on rps16 gene sequences. Nuclear copies of rps16 are indicated in bold purple. Bootstrap support values > 50% are shown at nodes. Scale bar indicates a phylogenetic distance of 0.3 nucleotide substitutions per site.

Discussion

Pseudogenization or loss of plastid genes is often accompanied by the transfer of the gene to the nuclear genome or substitution by a nuclear gene that is already targeted to the plastid27, 67. Plastid gene loss and transfer to the nucleus or substitution by a dual targeted nuclear gene targeted to organelles has been recorded for several genes across multiple angiosperm lineages4–17. The focus of this study was to use transcriptome data to bioinformatically identify the fate of two plastid genes, rpl32 and rps16, in Euphorbia schimperi that have either been lost or pseudogenized. Plastome sequences of Malpighiales have documented the loss of rpl32 and rps16 but the fate of these two genes in most families has not been examined. In this study, the phylogenetic distribution of the loss/transfer/substitution of these genes across the Malpighiales was examined.

The transfer of plastid-encoded rpl32 to the nucleus has been identified previously in three families of Malpighiales, namely Rhizophoraceae, Salicaceae and Passifloraceae10, 11, 14. Cusack and Wolfe10 identified the duplication of a nuclear chimeric gene (pt SOD-1-RPL32 fusion protein and pt SOD-1 protein) that is associated with the transfer of rpl32 in Populus. Ueda et al.11 experimentally confirmed the functional transfer of the rpl32 gene from the plastid to the nucleus and showed that the pt SOD-1-RPL32 fusion protein is targeted to the plastid of Populus by using green fluorescent protein (GFP). Shrestha et al.14 identified high sequence identity of the pt SOD-1-RPL32 fusion protein to pt SOD-1-RPL32 transcript of Populus by mapping to the transcriptome of Passiflora. In the current study, Euphorbia schimperi and other Euphorbia species available at NCBI have experienced loss of the rpl32 gene but no previous studies have been performed to determine the fate of this gene. An E. schimperi transcript that represents pt SOD-1-RPL32 has been identified confirming that the transfer in Euphorbiaceae is similar to three other families (Rhizophoraceae, Salicaceae and Passifloraceae) of Malpighiales. Since these four families share a high sequence similarity of the transit peptide derived from pt sod-1 and the loss from the plastome is widespread in order, the timing of the transfer event may date to the early divergence of this clade (Fig. 5). The other families of Malpighiales have not been examined but they may also have nuclear encoded copies of rpl32. If this is the case, the plastid-encoded copies in some Malpighiales may not have been pseudogenized or lost yet in these families. Additional sampling of transcriptomes of other families of Malpighiales is needed to more accurately determine the timing of the rpl32 transfer to the nucleus. Ranunculaceae (Thalictrum coreanum and Aquilegia caerulea) experienced an independent transfer of plastid-encoded rpl32 to the nucleus because its transit peptide sequence is substantially different from the distantly related families of Malpighiales (Fig. 6)12.

The substitution of the plastid-encoded rps16 by a dual targeted nuclear-encoded mitochondrial gene was identified previously in two families of Malpighiales, Salicaceae and Passifloraceae14, 22. In Populus alba (Salicaceae), Ueda et al.22 experimentally localized the two nuclear-encoded rps16 genes that are dually targeted to the plastid and mitochondrion using GFP. A similar substitution occurs in the monocot Oryza sativa and eudicot Arabidopsis thaliana22. In addition, bioinformatic comparisons in Passifloraceae identified RPS16-1 and RPS16-2 in the transcriptome, with one targeted to the plastid and the other to the mitochondrion. Euphorbia schimperi plastome sequences and other Euphorbia species available at NCBI have experienced pseudogenization of rps16 gene and no previous studies have elucidated the fate of plastid-encoded rps16 loss in the genus. In Euphorbiaceae three species of subfamily Crotonoideae, Jatropha carcus23, Deutzianthus tonkinensis25 and Vernicia fordii24, are missing plastid-encoded rps16. In most cases the loss of rps16 is associated with a deletion in the intergenic spacer between trnK-UUU and trnQ-UUG or an inversion in the same region23. The loss of rps16 in the gymnosperm Keteleeria davidiana, the monocot Dioscorea elephantipes and eudicots (Aethionema cordifolium, Aethionema grandiflorum, Arabis hirsuta, Draba nemorosa, Lobularia maritima, Populus alba, Populus trichocarpa, Cuscuta gronovii, Cuscuta exaltata and Epifagus virginana) is also the result of deletion in the same region23. In Jatropha curcas the loss of rps16 gene is associated with a 1.3 kb deletion in the trnK-trnQ intergenic region23. Likewise, Euphorbia schimperi has a deletion of 0.5 kb in the same intergenic region (Fig. S2A,B).

The situation in Euphorbia schimperi is similar to Salicaceae and Passifloraceae with two copies, RPS16-1 and RPS16-2, in the nucleus (Fig. 7). Since the three families (Salicaceae, Passifloraceae and Euphorbiaceae) of Malpighiales share a high sequence identity of the RPS16-1 and RPS16-2, the gene substitution likely occurred early in the divergence of Malpighiales (Fig. 5), although comparisons of plastomes and transcriptomes of other families in the order are needed to confirm the timing. Some taxa in these families still retain an intact copy of rps16 in the plastome but it is not known if these are functional or if they simply have not been lost or pseudogenized yet.

Conclusion

The sequence of Euphorbia schimperi expands the understanding of the evolution of plastomes within Malpighiales. Gene order of E. schimperi is highly conserved with the typical structure of the angiosperm plastomes. The only unusual feature of the E. schimperi are gene-content changes with the loss of rpl32, rps16 and infA. Screening the nuclear transcriptome of E. schimperi shows that two of these genes have been either transferred to the nucleus or substituted by a duplicated nuclear-encoded mitochondrially-targeted gene. The fate of infA was not determined because a nuclear-encoded copy was not found in the transcriptome. Comparisons of the nuclear copies of rpl32 and rps16 genes of E. schimperi to members of other families of Malpighiales (Salicaceae and Passifloraceae) suggest that the transfer or substitution events in Euphorbiaceae may have occurred early in the divergence of this order.

Materials and methods

Plant material and DNA and RNA isolation

Euphorbia schimperi plants were obtained from the Arid Land Greenhouses (https://aridlandswholesale.com/) in Tucson, Arizona and grown in the greenhouse at the University of Texas at Austin. A voucher specimen was deposited in the TEX/LL herbarium as Alqahtani s.n. (TEX 00501952). Leaves were harvested from a single plant, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 Co until isolations were performed. Whole genomic DNA was extracted from 0.2 g of the leaves using the Doyle and Doyle68 protocol with the following modifications: 2% PVP and 2% β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) were added to the cetyl trimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) extraction buffer. The clear aqueous fraction was obtained after repeated separations with chloroform: isoamyl alcohol, followed by precipitation with isopropanol and 3 M sodium acetate. The pellet was washed with 70% ethanol and then resuspended in ~ 200 μl DNase-free water. The sample was subjected to RNase treatment followed by another phase separation with chloroform: isoamyl alcohol and recovered by precipitation with isopropanol and 3 M sodium acetate. The DNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol, resuspended in ~ 50 μL H2O and stored at − 20 °C.

RNA was extracted from 0.25 g of leaves from a single plant that was from the same clone used for the DNA extraction using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). Using DNase digestion, RNA was treated to eliminate any remaining DNA based on the enzyme protocol (Fermentas #EN0521, 1 unit/μL, Waltham, MA, USA). The 50 μL RNA sample was combined with 30 μL of 10× buffer and 20 μL DNase enzyme for a total volume of 100 μL. After incubation for 1 h at 37 °C DNase was removed using microcolumns and then cleaned with RNA Clean & Concentrator-25 following the manufacturer’s instructions (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). The quality and quantity of the RNA sample was evaluated with the targeted optimal values of > 200 ng/µL, 260/280 ratio from 1.9 to 2.1, 260/230 ratio between 2.0 to 2.5 and RNA integrity number (RIN) > 8.0.

Genome sequencing, assembly and annotation

DNA with a concentration of 100 ng/µL and volume of 42 µL was submitted for paired end sequencing (2 × 150 bp) on the Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform at the Genome Sequencing Analysis Facility (GSAF) at the University of Texas at Austin. Velvet v.1.2.0769 with multiple K-mer values between 81 to 109 and coverage cutoffs of 200X, 500X and 1000X was used for de novo assembly of the Illumina reads at the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC, http://www.tacc.utexas.edu). The resulting contigs from 15 different k-mer parameters assembled with 500X and 1000X coverage were imported into Geneious (v.10.0.6; http://www.geneious.com)70. De novo assembly with default settings was run to generate long contigs that represented the entire plastome. Putative plastid contigs were identified using the Euphorbia esula plastome as a reference in Geneious. A gap between ycf1 and ndhF was filled by overlapping contigs. The second gap between atpH and atpF and ambiguous nucleotides were filled by mapping contigs against the raw reads using Bowtie 2 version 2.3.465.

Annotation of the plastome was conducted using multiple software platforms. Geneious was used to check for start and stop codons for every gene compared to Nicotiana tabacum (NC_001879.2) and species of Euphorbiaceae available publicly, including Jatropha curcas (NC_012224.1), Euphorbia esula (NC_033910.1), Manihot esculenta (NC_010433.1), Ricinus communis (NC_016736.1) and Hevea brasiliensis (NC_015308.1). Dual Organellar Genome Annotator (DOGMA) was utilized to identify coding sequences with default settings71. The tRNAscan-SE online search server was used to confirm tRNA genes72, 73. Based on the loss of portions of the sequence or presence of internal stop codons, pseudogenes were identified. A genome map was drawn using OGDRAW74.

Transcriptome de novo assembly

Standard RNA-Seq with ribosomal RNA removal library preparation and sequencing via Illumina HiSeq 4000 were carried out at GSAF. The quality of raw FastQC reads was examined using the FastQC tool v.0.11.5 (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/)75. Raw RNA-seq data was not subjected to quality trimming. A de novo assembly of RNA-seq reads into transcripts was performed using Trinity76 with 25 k-mer size77. Trinity sequentially integrates Inchworm, Chrysalis and Butterfly modules to process a large number of RNA-Seq reads. This has been used to partition the sequence data into different individual de Bruijn graphs, which represent the transcriptional complexity at a given gene or locus77.

Transcriptome quality assessment and annotation

To validate the de novo assembly, read remapping was conducted using two software packages, Bowtie2 v.2.3.265 and Benchmarking Universal Single-copy Orthologs (BUSCO) v.3.0.278. Bowtie2 index was created for the data and the number of reads that mapped to the transcriptome was counted. BUSCO was carried out using the Embryophyta and Eukaryota databases. BUSCO assessment provided quantitative measures to identify the completeness of the transcriptome based on evolutionarily informed expectations of the gene content from near-universal single-copy orthologs selected from OrthoDB v.978. In addition, N25, N50 and N75 contigs of transcriptome and translated transcriptome were identified. De novo assemblies contain no information about what genes the contigs may correspond to, so the final transcriptome assembly for E. schimperi was annotated to identify genes and functional terms the contigs likely correspond to using the BLASTx searches against the protein database (SwissProt) (http://www.uniprot.org) and the predicted Arabidopsis thaliana proteome (Tair v.10, http://arabidopsis.org) using the BLAST settings (BLASTx, report 1 hit, e-value of 1e−5). TACC was used to conduct the analyses of transcriptome assembly and quality assessments.

Identification of gene transfer and substitution

The final assembly set of transcripts of E. schimperi was subjected to TransDecoder v3.0.1 (https://transdecoder.github.io/) to determine potential coding regions. LongOrfs was used to select the best single open reading frame (ORF) per transcript longer than 100 amino acids. Plastid gene transfer/substitution in E. schimperi to the nucleus was examined by performing BLASTp searches of plastid-encoded RPL32 sequences of M. esculenta (ABV66201.1), R. communis (AEJ82604.1), H. brasiliensis (YP_004327709.1), V. fordii (YP_009371112.1), J. curcas (ACN72738.1), E. marginata (AMC32178.1), Arabidopsis thaliana (NP_051107.1) and Nicotiana tabacum (CAA77431.1) and plastid-encoded RPS16 sequences of A. thaliana (NP_051041.1), N. tabacum (NP_054479.1), M. esculenta (ABV66136.1), R. communis (AEJ82537.1) and H. brasiliensis (ADO33539.1) against the peptide sequences for the final candidate ORFs of the E. schimperi transcriptome.

BLASTp searches of the query sequences [nuclear- encoded RPL32 of Passiflora (P. pittieri (QKY65179.1), P. contracta (QKY65180.1), P. oerstedii (QKY65177.1) and P. biflora (QKY65178.1)], Populus alba (BAF80584.1), Populus alba SOD-1 (BAF80585.1) and nuclear- encoded RPS16-1& RPS16-2 copies sequences of Passiflora [P. pittieri (RPS16-1: QKY65183.1, RPS16-2: QKY65185.1), P. tenuiloba (RPS16-1: QKY65187.1, RPS16-2: QKY65184.1)] and Populus alba (RPS16-1: BAG49074.1, RPS16-2: BAG49075.1) against the peptide sequences for the final candidate ORFs of E. schimperi transcriptome were conducted. BLASTp commands utilized were e-value 1e-2 -outfmt 6 -num_threads 4. The query sequences were downloaded from GenBank (https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Nuclear and plastid copies of RPL32 and RPS16 sequences were aligned with MAFFT v7.38879 in Geneious.

Putative transit peptides and a mitochondrial targeting peptide of nuclear transferred genes were identified using TargetP-1.180(http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP-1.1/index.php) and LOCALIZER81 (http://localizer.csiro.au/). To detect the source of the transit peptide for the nuclear-encoded RPL32 and RPS16, BLAST searches (BLASTp) were conducted against the NCBI database.

Phylogenetic analyses

Phylogenetic analyses were performed on three data sets. The first included 45 plastid-encoded gene sequences extracted from 35 taxa of Malpighiales and two outgroups in Fabales, Pisum sativum and Glycine max (Tables S2, S3). The second included both nuclear- (6) and plastid-encoded (65) rpl32 genes (Table S4). This data set was constructed by adding nine Euphorbiaceae species and ten species of Malpighiales to data (52 species) from Park et al. (2015), which is available in Dryad Digital Repository (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.g84g5/Align_52rpl32only_tree). The third included both nuclear-(8) and plastid-encoded (52) rps16 genes (Table S5). All alignments were performed using MAFFT v.7.38879 with default settings in Geneious. Phylogenetic analyses of first data set was conducted using maximum likelihood (ML) in RAxML-NG v.0.9 with the GAMMA GTR model under rapid bootstrapping algorithm with 100 bootstrap replicates (https://raxml-ng.vital-it.ch/#/)82. The single gene trees were generated using maximum likelihood (ML) in IQ-TREE v.1.6.12 with the TVM + F + G4 best fit model in rpl32 gene and GTR + F + I + G4 in rps16 under rapid bootstrapping algorithm with 1000 bootstrap replicates83. FigTree v.1.4.484 was used to visualize phylogenetic trees.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Sidney F. and Doris Blake Professorship in Systematic Botany to R.K.J. A.A.A would like to acknowledge her academic sponsors at Prince Sattam bin Abdul-Aziz and Dr. In-Su Choi for his critical reading and valuable suggestions on an earlier version of the manuscript. Furthermore, a great deal of appreciation goes to Dr. Tracey A. Ruhlman for assistance with the DNA extraction. Many thanks go to Benjamin Goetz and Dhivya Arasappan from the Center for Computational Biology and Bioinformatics (CCBB) at the University of Texas at Austin for their help in transcriptome analysis. A.A.A. also appreciates her fellow graduate students, Bikash Shrestha and Chaehee Lee, who provided expertise in the lab.

Author contributions

A.A.A. designed the project, carried out all analyses including the preparation of the figures, tables, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. R.K.J. helped to design the project, interpreted results, read/edited the manuscript and supported the research.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-86820-z.

References

- 1.McFadden GI. Primary and secondary endosymbiosis and the origin of plastids. J. Phycol. 2001;37:951–959. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2001.01126.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeremy N, Timmis MAA, Huang CY, Martin W. Endosymbiotic gene transfer: organelle genomes forge eukaryotic chromosomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:123–135. doi: 10.1038/nrg1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruhlman TA, Jansen RK. The plastid genomes of flowering plants. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014;1132:3–38. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-995-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millen RS, et al. Many parallel losses of infA from chloroplast DNA during angiosperm evolution with multiple independent transfers to the nucleus. Plant Cell. 2001;13:645–658. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.3.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansen RK, et al. Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:19369–19374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709121104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo X, et al. Rapid evolutionary change of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L) plastome, and the genomic diversification of legume chloroplasts. BMC Genom. 2007;8:228. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tangphatsornruang S, et al. The chloroplast genome sequence of mungbean (Vigna radiata) determined by high-throughput pyrosequencing: structural organization and phylogenetic relationships. DNA Res. 2010;17:11–22. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsp025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steane DA. Complete nucleotide sequence of the chloroplast genome from the Tasmanian blue gum, Eucalyptus globulus (Myrtaceae) DNA Res. 2005;12:215–220. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsi006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okumura S, et al. Transformation of poplar (Populus alba) plastids and expression of foreign proteins in tree chloroplasts. Transgenic Res. 2006;15:637–646. doi: 10.1007/s11248-006-9009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cusack BP, Wolfe KH. When gene marriages don't work out: divorce by subfunctionalization. Trends Genet. 2007;23:270–272. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ueda M, et al. Loss of the rpl32 gene from the chloroplast genome and subsequent acquisition of a preexisting transit peptide within the nuclear gene in Populus. Gene. 2007;402:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park S, Jansen RK, Park S. Complete plastome sequence of Thalictrum coreanum (Ranunculaceae) and transfer of the rpl32 gene to the nucleus in the ancestor of the subfamily Thalictroideae. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:40. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0432-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabah SO, et al. Passiflora plastome sequencing reveals widespread genomic rearrangements. J. Syst. Evol. 2018;57:1–14. doi: 10.1111/jse.12425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shrestha B, Gilbert LE, Ruhlman TA, Jansen RK. Rampant nuclear transfer and substitutions of plastid genes in Passiflora. Genome Biol. Evol. 2020;12:1313–1329. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evaa123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu M-L, Fan W-B, Wu Y, Wang Y-J, Zhong-Hu L. The complete nucleotide sequence of chloroplast genome of Euphorbia kansui(Euphorbiaceae), an endemic herb in China. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2018;3:831–832. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2018.1495122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J-F, et al. Complete chloroplast genome of Euphorbia hainanensis (Euphorbiaceae), a rare cliff top boskage endemic to China. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2019;4:1325–1326. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1596761. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan A, et al. Comparative chloroplast genomics of endangered Euphorbia species: Insights into hotspot divergence, repetitive sequence variation, and phylogeny. Plants. 2020;9:199. doi: 10.3390/plants9020199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keller J, et al. The evolutionary fate of the chloroplast and nuclear rps16 genes as revealed through the sequencing and comparative analyses of four novel legume chloroplast genomes from Lupinus. DNA Res. 2017;24:343–358. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsx006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saski C, et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Glycine max and comparative analyses with other legume genomes. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005;59:309–322. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-8882-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jansen RK, Wojciechowski MF, Sanniyasi E, Lee SB, Daniell H. Complete plastid genome sequence of the chickpea (Cicer arietinum) and the phylogenetic distribution of rps12 and clpP intron losses among legumes (Leguminosae) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2008;48:1204–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarz EN, et al. Plastid genome sequences of legumes reveal parallel inversions and multiple losses of rps16 in papilionoids. J. Syst. Evol. 2015;53:458–468. doi: 10.1111/jse.12179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ueda M, et al. Substitution of the gene for chloroplast RPS16 was assisted by generation of a dual targeting signal. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008;25:1566–1575. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asif MH, et al. Complete sequence and organisation of the Jatropha curcas (Euphorbiaceae) chloroplast genome. Tree Genet Genomes. 2010;6:941–952. doi: 10.1007/s11295-010-0303-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Z, et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of tung tree (Vernicia fordii): organization and phylogenetic relationships with other angiosperms. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1869. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02076-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang QY, Qu ZZ, Tian XM. Complete chloroplast genome of an endangered oil tree, Deutzianthus tonkinensis (Euphorbiaceae) Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2019;4:299–300. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2018.1542991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gantt JS, Baldauf SL, Calie PJ, Weeden NF, Palmer JD. Transfer of rpl22 to the nucleus greatly preceded its loss from the chloroplast and involved the gain of an intron. Embo J. 1991;10:3073–3078. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jansen RK, Saski C, Lee SB, Hansen AK, Daniell H. Complete plastid genome sequences of three rosids (Castanea, Prunus, Theobroma): Evidence for at least two independent transfers of rpl22 to the nucleus. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28:835–847. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stegemann S, Hartmann S, Ruf S, Bock R. High-frequency gene transfer from the chloroplast genome to the nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:8828–8833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1430924100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sugiura C, Kobayashi Y, Aoki S, Sugita C, Sugita M. Complete chloroplast DNA sequence of the moss Physcomitrella patens: evidence for the loss and relocation of rpoA from the chloroplast to the nucleus. Nucl. Acids Res. 2003;31:5324–5331. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Konishi T, Shinohara K, Yamada KA, Sasaki Y. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase in higher plants: most plants other than Gramineae have both the prokaryotic and the eukaryotic forms of this enzyme. Plant Cell Physiol. 1996;37:117–122. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a028920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bubunenko MG, Schmidt J, Subramanian AR. Protein substitution in chloroplast ribosome evolution—a eukaryotic cytosolic protein has replaced its organelle homolog (L23) in spinach. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;240:28–41. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weng ML, Ruhlman TA, Jansen RK. Plastid-nuclear interaction and accelerated coevolution in plastid ribosomal genes in Geraniaceae. Genome Biol. Evol. 2016;8:1824–1838. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruce BD. Chloroplast transit peptides: structure, function and evolution. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:440–447. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(00)01833-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson LGL, Singhal R, Schnell DJ. The integration of chloroplast protein targeting with plant developmental and stress responses. BMC Biol. 2017;15:118. doi: 10.1186/s12915-017-0458-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McFadden GI. Endosymbiosis and evolution of the plant cell. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 1999;2:513–519. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(99)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Obara K, Sumi K, Fukuda H. The use of multiple transcription starts causes the dual targeting of Arabidopsis putative monodehydroascorbate reductase to both mitochondria and chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43:697–705. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe N, et al. Dual targeting of spinach protoporphyrinogen oxidase II to mitochondria and chloroplasts by alternative use of two in-frame initiation codons. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:20474–20481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christensen AC, et al. Dual-domain, dual-targeting organellar protein presequences in Arabidopsis can use non-AUG start codons. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2805–2816. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rudhe C, Clifton R, Whelan J, Glaser E. N-terminal domain of the dual-targeted pea glutathione reductase signal peptide controls organellar targeting efficiency. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;324:577–585. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bardon L, et al. Unraveling the biogeographical history of Chrysobalanaceae from plastid genomes. Am. J. Bot. 2016;103:1089–1102. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1500463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheon KS, Yang JC, Kim KA, Jang SK, Yoo KO. The first complete chloroplast genome sequence from Violaceae (Viola seoulensis) Mitochondrial DNAPart B. 2017;28:67–68. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2015.1110801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jo S, et al. The complete plastome of tropical fruit Garcinia mangostana (Clusiaceae) Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2017;2:722–724. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2017.1390406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramachandran P, et al. Sequencing the vine of the soul: full chloroplast genome sequence of Banisteriopsis caapi. Genome Announc. 2018 doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00203-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang J, Wang Y, Xu S, He J, Zhang Z. The complete chloroplast genome of Cratoxylum cochinchinense (Hypericaceae) Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2019;4:3452–3453. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1674216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jin DM, Jin JJ, Yi TS. Plastome structural conservation and evolution in the clusioid clade of Malpighiales. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:9091. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66024-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ke X-R, et al. Complete plastome sequence of Mallotus peltatus(Geiseler) Müll. Arg. (Euphorbiaceae): A beverage and medicinal plant in Hainan. China. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2020;5:953–954. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2020.1719935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.A. P. Angiosperm Phylogeny Website https://www.mobot.org/mobot/research/apweb/.

- 48.Duarte N, Gyémánt N, Abreu PM, Molnár J, Ferreira MJU. New macrocyclic lathyrane diterpenes, from Euphorbia lagascae, as inhibitors of multidrug resistance of tumour cells. Planta Med. 2006;72:162–168. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-873196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhanot A, Sharma R, Noolvi MN. Natural sources as potential anti-cancer agents: A review. Int. J. Phytomed. 2011;3:9. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horn JW, et al. Phylogenetics and the evolution of major structural characters in the giant genus Euphorbia L. (Euphorbiaceae) Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 2012;63:305–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jassbi AR. Chemistry and biological activity of secondary metabolites in Euphorbia from Iran. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:1977–1984. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chinmayi, U., Ajay, K. & Sathish. S. A study on anti-cancer activity of Euphorbia neriifolia (Milk Hedge) latex. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Technol.5 (2017).

- 53.Bruyns PV, Klak C, Hanacek P. Age and diversity in old world succulent species of Euphorbia (Euphorbiaceae) Taxon. 2011;60:1717–1733. doi: 10.1002/tax.606016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.INaturalist. Photos of Euphorbia schimperi. https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/343121-Euphorbia-schimperi/browse_photos.

- 55.World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; http://wcsp.science.kew.org/ Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- 56.Azza, R. A., Essam, A., Fathalla, M. H. and Petereit, F. Chemical investigation of Euphorbia schimperi C. Presl. Acad. Chem. Glob. Publ. (2008).

- 57.Ernst M, et al. Assessing Specialized metabolite diversity in the cosmopolitan plant genus Euphorbia L. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:846. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ahmed S, Yousaf M, Mothana RA, Alrehaily AAJ. Studies wound on wound healing activity of some Euphorbia species on experimental rats. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2016;13:145–152. doi: 10.21010/ajtcam.v13i5.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hu X-D, Pan B-Z, Fu Q, Chen M-S, Xu Z-F. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of the biofuel plant Sacha Inchi Plukenetia volubilis. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2018;3:328–329. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2018.1437816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Niu Y-F, Hu Y-S, Zheng C, Liu Z-Y, Liu J. The complete chloroplast genome of Hevea camargoana. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2020;5:607–608. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1710605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li P, Liang X, Zhang X. Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of Euphorbia helioscopia Linn. (Euphorbiaceae), a traditional Chinese medicine. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2019;4:3770–3771. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1682480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou X, et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Chinese tallow Triadica sebifera (Linnaeus) Small (Euphorbiaceae) Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2019;4:1105–1106. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1586493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jiang Y-L, Wang H-X, Zhu Z-X, Wang H-F. Complete plastome sequence of Euphorbia milii Des Moul. (Euphorbiaceae) Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2020;5:426–427. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1703598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liao X, Wang H-X, Zhu Z-X, Wang H-F. Complete plastome sequence of Croton laevigatus Vahl (Euphorbiaceae): an endemic species in Hainan, China. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2020;5:457–458. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1704659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wolfe KH, Sharp PM, Li W-H. Rates of synonymous substitution in plant nuclear genes. J. Mol. Evol. 1989;29:208–211. doi: 10.1007/BF02100204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cauz-Santos LA, et al. The chloroplast genome of Passiflora edulis (Passifloraceae) assembled from long sequence reads: structural organization and phylogenomic studies in Malpighiales. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:334. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small amounts of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 1987;19(1):11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008;18:821–829. doi: 10.1101/gr.074492.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kearse M, et al. Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wyman SK, Jansen RK, Boore JL. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3252–3255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lowe TM, Chan PP. tRNAscan-SE on-line: integrating search and context for analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucl. Acids Res. 2016;44:W54–57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucl. Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lohse M, Drechsel O, Kahlau S, Bock R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW–a suite of tools for generating physical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes and visualizing expression data sets. Nucl. Acids Res. 2013;41:W575–581. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Andrews, S. FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data [Online]. Available online at: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (2010).

- 76.Grabherr MG, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Haas BJ, et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:1494–1512. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Waterhouse RM, et al. BUSCO Applications from quality assessments to gene prediction and phylogenomics. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:543–548. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Emanuelsson O, Nielsen H, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins based on their N-terminal amino acid sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;300:1005–1016. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sperschneider J, et al. LOCALIZER: Subcellular localization prediction of both plant and effector proteins in the plant cell. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:44598. doi: 10.1038/srep44598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alexey MK, Diego D, Tomáš F, Benoit M, Alexandros S. RAxML-NG: A fast, scalable, and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics. 2019 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jana T, Lam-Tung N, von Arndt H, Bui QM. W-IQ-TREE: A fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucl. Acids Res. 2016;44:W232–W235. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rambaut, A. FigTree v1.4.4 (2012).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.