Abstract

AXIN1 mutations are observed in 8–10% of hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs) and originally were considered to support tumor growth by aberrantly enhancing β-catenin signaling. This view has however been challenged by reports showing neither a clear nuclear β-catenin accumulation nor clearly enhanced expression of β-catenin target genes. Here, using nine HCC lines, we show that AXIN1 mutation or siRNA mediated knockdown contributes to enhanced β-catenin signaling in all AXIN1-mutant and non-mutant lines, also confirmed by reduced signaling in AXIN1-repaired SNU449 cells. Both AXIN1 and AXIN2 work synergistically to control β-catenin signaling. While in the AXIN1-mutant lines, AXIN2 is solely responsible for keeping signaling in check, in the non-mutant lines both AXIN proteins contribute to β-catenin regulation to varying levels. The AXIN proteins have gained substantial interest in cancer research for a second reason. Their activity in the β-catenin destruction complex can be increased by tankyrase inhibitors, which thus may serve as a therapeutic option to reduce the growth of β-catenin-dependent cancers. At concentrations that inhibit tankyrase activity, some lines (e.g. HepG2, SNU398) were clearly affected in colony formation, but in most cases apparently independent from effects on β-catenin signaling. Overall, our analyses show that AXIN1 inactivation leads to enhanced β-catenin signaling in HCC cell lines, questioning the strong statements that have been made in this regard. Enhancing AXIN activity by tankyrase monotherapy provides however no effective treatment to affect their growth exclusively through reducing β-catenin signaling.

Subject terms: Liver cancer, Cell signalling, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Targeted therapies

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a prevalent cancer with worldwide around 700,000 new cases diagnosed yearly, and a leading cause of cancer related deaths1,2. Aberrant activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is often observed in HCC3. Intracellular β-catenin levels are regulated by a multiprotein complex composed of the APC tumor suppressor, scaffold proteins AXIN1, AXIN2 and the kinases GSK3 and CK1α3,4. When cells are not exposed to extracellular Wnt ligands, β-catenin is constitutively phosphorylated and degraded to maintain cytoplasmic levels at a minimum. Following Wnt stimulation, the multiprotein complex dissociates resulting in the accumulation of cytosolic and nuclear β-catenin, which in turn triggers the transcription of specific target genes. Aberrant activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in HCC has been mainly attributed to activating somatic mutations in the CTNNB1 gene coding for β-catenin (20–25%)3,5–8, for which it is well-accepted that they support tumor growth by enhancing β-catenin signaling in a dominant fashion.

Another component of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway regularly inactivated in HCC is AXIN1 (8–10%)3,5,6,9. Originally, given its role in the β-catenin destruction complex, mutational inactivation of AXIN1 was considered to support HCC development by aberrantly enhancing β-catenin signaling. This view has however been challenged by several reports showing neither a clear nuclear β-catenin accumulation nor clearly enhanced expression of β-catenin target genes in AXIN1-mutant HCCs10–12. Others have provided some evidence of increased β-catenin signaling in AXIN1 mutant HCC cells, albeit modest11,13,14. Qiao and coworkers showed that HCC induction following AXIN1 deletion in mouse livers was strongly dependent on functional β-catenin, but as argued by others only in the context of simultaneous MET activation15–17. Hence, whether β-catenin signaling is activated following AXIN1 mutation and its relevance for supporting human HCC growth is still heavily debated.

The AXIN proteins have gained substantial interest in cancer research for a second reason. Their activity in the β-catenin destruction complex can be increased by tankyrase inhibitors, which thus may serve as a therapeutic option to treat β-catenin-dependent cancers. The AXIN proteins, like β-catenin itself, are under tight proteolytic control. Poly-ADP-ribosyltransferases tankyrase-1 and -2 (encoded by TNKS/TNKS2) associate with AXIN, resulting in their PARsylation and subsequent ubiquitylation and degradation, thereby limiting the activity of the destruction complex18–21. Blocking tankyrases results in the formation of so-called degradasomes in which all components of the β-catenin destruction complex aggregate, leading to an efficient β-catenin turnover. Application of these tankyrase inhibitors has been investigated for the treatment of various cancer types, with some successful initial results for a subset of tumors22–30.

Here, we employed CTNNB1-, AXIN1- and non-mutant HCC cell lines to investigate the impact of tankyrase inhibition on Wnt/β-catenin signaling as well as growth, and to further explore the function of AXIN1/AXIN2 in regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling in HCC cells.

Results

Baseline levels of AXIN1 and AXIN2 in HCC cell lines

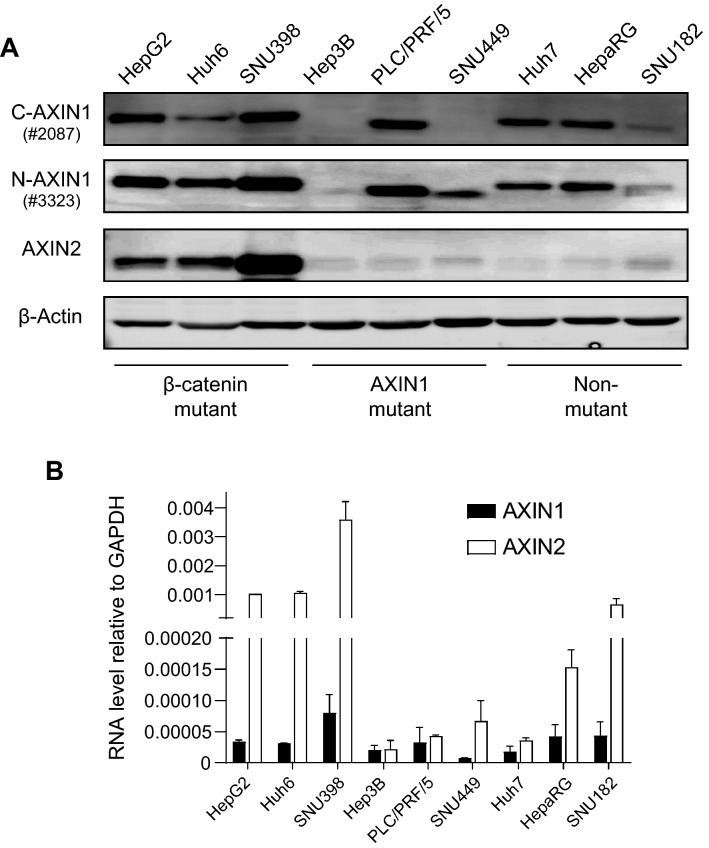

To explore the function of AXIN1 and AXIN2 in regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling in HCC cells, we employed 9 HCC cell lines listed in Supplemental Table S1, in which gene mutations related to Wnt/β-catenin signaling are depicted. By western blotting, AXIN1 was detectable in all lines except Hep3B carrying a homozygous p.R146* mutation (Fig. 1A). AXIN2 was clearly detectable in the β-catenin mutant lines, and weakly visible in the others. Next, we compared AXIN1 and AXIN2 RNA expression levels by TaqMan qRT-PCR (Fig. 1B). AXIN2 was expressed at higher levels than AXIN1 in most HCC cell lines, independent of their β-catenin related mutation status. In accordance with AXIN2 being a β-catenin target gene, the expression differences were largest in the CTNNB1 mutant lines.

Figure 1.

Baseline levels of AXIN1 and AXIN2 in HCC cell lines. (A) Western blotting assay showing the basal protein levels of AXIN1 and AXIN2. For AXIN1 both N-terminal and C-terminal antibodies were used, respectively, #3323 and #2087 from Cell Signaling Technology. (B) RNA levels tested by TaqMan qRT-PCR (mean ± SD, n = 2, twice). All expression levels are depicted relative to the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Note the interrupted Y-axis scale.

Both AXIN1 and AXIN2 contribute to β-catenin signaling regulation in HCC cell lines

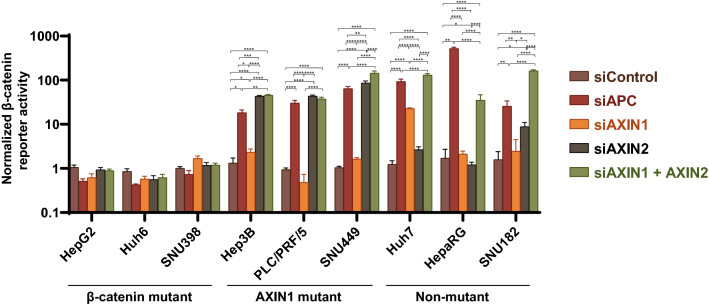

To evaluate the functionality of either AXIN1 or AXIN2 to the regulation of β-catenin signaling in each cell line, we silenced expression of each gene separately or in combination, using SMARTpool siRNA mediated knockdown (Supplemental Fig. S1). APC knockdown was used as a positive control for activation of β-catenin signaling.

In line with the supposed dominant activity of mutant β-catenin, no significant changes in β-catenin reporter activity were observed in the CTNNB1-mutant lines (Fig. 2, Supplemental Fig. S2). As expected, APC knockdown resulted in a strong increase of β-catenin reporter activity in all other lines. Importantly, in all three AXIN1-mutant lines a comparable increase in reporter activity was observed as a consequence of solely AXIN2 knockdown. AXIN1 knockdown in these lines showed however no significant effect on reporter activity. These results show that AXIN2 is expressed at biologically functional levels in the AXIN1-mutant lines and confirm that the AXIN1 mutation impairs its role in β-catenin regulation.

Figure 2.

Both AXIN1 and AXIN2 contribute to β-catenin signaling regulation in HCC cell lines. All cell lines were subjected to a β-catenin reporter assay after siRNA-mediated knockdown of AXIN1, AXIN2, a combination thereof or APC. No significant changes in β-catenin reporter activity were observed in the CTNNB1-mutant lines. Among the AXIN1-mutant cells (Hep3B, PLC/PRF/5 and SNU449) both APC and AXIN2 knockdown are equally effective in enhancing signaling. AXIN1 or AXIN2 knockdown in the non-mutant lines (Huh7, HepaRG, SNU182) results in an incomplete increase in reporter activity when compared with APC knockdown, while combined AXIN1/AXIN2 knockdown is similarly effective. For this experiment the WRE/CMV-Renilla ratio for the control siRNA sample-1 was arbitrarily set to 1 for each cell line, after which all β-catenin reporter WRE/CMV-Renilla ratios for the samples were normalized to this control. Only significant differences are shown using an unpaired t-test (mean ± SD, n = 3, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). Note the logarithmic Y-axis scale. The result shown here is one representative result, but comparable results were observed in two independent experiments performed on relevant lines (Supplemental Fig. S2).

Among the non-mutant cell lines a variable response was noted upon AXIN1 or AXIN2 knockdown. In Huh7 cells knockdown of only AXIN1 led to a strong increase in reporter activity, while this was the case for AXIN2 in SNU182. HepaRG cells were barely affected in β-catenin reporter activity with knockdown of either gene separately. However, simultaneous knockdown of AXIN1 and AXIN2 led to a robust induction of β-catenin reporter activity in all non-mutant lines.

We also performed qRT-PCR analyses for the β-catenin target gene AXIN2. APC knockdown increased AXIN2 expression in all AXIN1- and non-mutant lines, while no change was observed in the CTNNB1-mutant line SNU398 used as control (Supplemental Fig. S3). AXIN1 knockdown led to a 2–4-fold increase in AXIN2 levels in all non-mutant lines, while as expected no clear change was observed in the AXIN1-mutant lines. A meaningful interpretation of AXIN2 knockdown is strongly complicated by the fact that total AXIN2 RNA levels are simultaneously downregulated by siRNA as well as upregulated by enhanced β-catenin signaling (a more detailed explanation is provided accompanying Supplemental Fig. S1). Hence, for the interpretation of the AXIN2 knockdown experiments we restricted ourselves to the reporter assays.

Taken together, these analyses show that (i) in HCC cell lines both AXIN1 and AXIN2 work synergistically to control β-catenin signaling; (ii) in the AXIN1-mutant lines, AXIN2 is solely responsible for keeping signaling in check, whereas in the non-mutant lines both AXIN proteins contribute to β-catenin regulation to varying levels depending on the cell line under investigation; (iii) in the non-mutant lines AXIN1 knockdown leads to an increase in β-catenin reporter activity and/or AXIN2 expression.

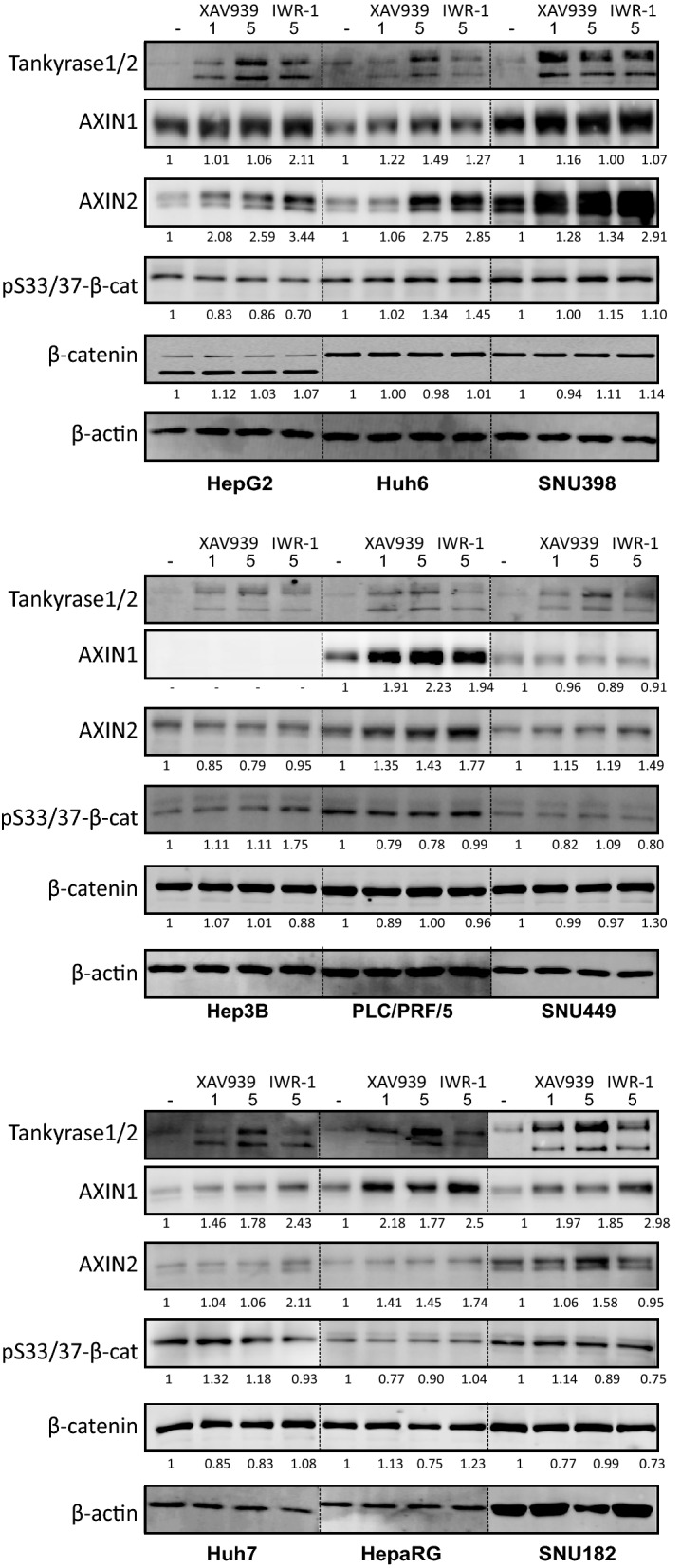

Effects on β-catenin signaling following tankyrase inhibition

The tankyrase enzymes have been shown to antagonize the activity of the β-catenin destruction complex by PARsylation and subsequent breakdown of AXINs18–21. Their inhibition can lead to an enhanced β-catenin turnover and growth suppression of a subset of β-catenin-dependent cancers22–30. All HCC cell lines showed readily detectable expression of TNKS/TNKS2 (Supplemental Fig. S4). We treated HCC cell lines with tankyrase inhibitors XAV939 or IWR-1, using the CRC cell line SW480 as positive control. In accordance with previous studies on SW480 cells, XAV939 and IWR-1 stabilized tankyrase-1/2, AXIN1 and AXIN2, increased pS33/37-β-catenin and diminished total β-catenin levels (Supplemental Fig. S5). Among the HCC cell lines, at least one of the AXIN proteins showed a clear accumulation, with the exception of Hep3B (Fig. 3, Supplemental Fig. S6). In the CTNNB1 mutant lines, AXIN2 was most prominently stabilized, while this was the case for AXIN1 in the non-mutant lines. With respect to β-catenin, a slight increase in pS33/37 phosphorylation was observed only in Huh6 and Hep3B, the latter restricted to IWR-1. Total β-catenin levels were not clearly altered in any of the lines.

Figure 3.

Effect of tankyrase inhibition on indicated proteins. Western blotting assay showing levels of tankyrase-1/2, AXIN1/2, p33/37-β-catenin (pS33/37-β-cat) and total β-catenin after 1-5 μM XAV939 or 5 μM IWR-1 for 24 h. Tankyrase-1/2 efficiently accumulate in all cell lines, while variable responses are observed for AXIN1 and AXIN2. No clear change is observed in pS33/37-β-catenin except for Huh6 and Hep3B, in which a modest increase is seen. Total β-catenin levels are not clearly altered.

In various cell lines tankyrase inhibition has been shown to lead to the formation of so-called β-catenin degradasomes, consisting of higher-order structures in which all components required for β-catenin degradation are present31. These degradasomes can be visualized as AXIN- and tankyrase-positive cytoplasmic puncta32, which were readily visible in XAV939 treated SW480 cells (Supplemental Fig. S7). This was also the case in Huh6 cells, although not as prominent as in SW480. By western blotting PLC/PRF/5 cells express clear levels of a mutant AXIN1 protein retaining the DIX domain required for multimerization. Accordingly, accumulation of tankyrase- and AXIN1-positive puncta was detectable, but no obvious change in abundance and subcellular localization of AXIN2 was visible. Lastly, in Hep3B cells exclusively tankyrase-positive puncta were observed, in line with the absent/low AXIN1/2 levels observed by western blot.

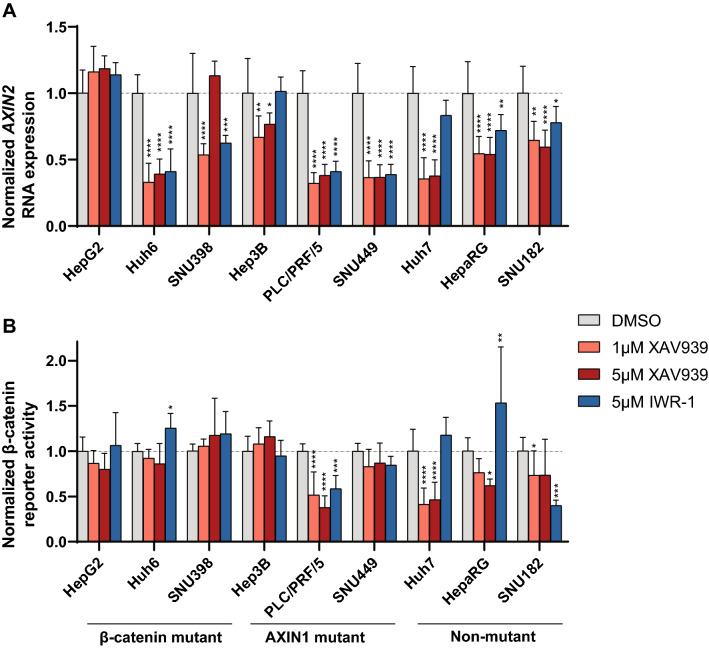

Combined these data suggest that tankyrase inhibition leads to the stabilization of AXIN1 and/or AXIN2 in most HCC cell lines, while total β-catenin levels are barely affected. To determine the direct consequences on β-catenin signaling following XAV939/IWR-1 treatment, we measured AXIN2 RNA expression and β-catenin reporter activity (Fig. 4, Supplemental Figs. S8/S9). We observed a 1.2–3-fold reduction in AXIN2 RNA levels in all lines after treatment with XAV939 or IWR-1, with the exception of HepG2 (XAV939 and IWR-1), and Hep3B and Huh7 (IWR-1). Using the reporter assay, significant reductions with XAV939 were only observed in PLC/PRF/5 and Huh7, whereas this was the case for PLC/PRF/5 and SNU182 using the IWR-1 inhibitor. Importantly, despite the 1.2–3-fold reduction in AXIN2 and/or β-catenin reporter levels observed in some of the lines, the absolute level of nuclear β-catenin signaling remains high in especially the CTNNB1- and AXIN1-mutant lines (Supplemental Fig. S8).

Figure 4.

Effect of tankyrase inhibition on Wnt/β-catenin signaling. HCC cell lines were incubated with 1-5 μM XAV939 or 5 μM IWR-1, followed by an AXIN2 qRT-PCR or a β-catenin reporter assay. (A) Fold changes in AXIN2 expression levels depicted relative to the DMSO control-treated samples, which are arbitrarily set to 1. Only significant changes (unpaired t-test) are shown (mean ± SD, n = 3, twice, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; 24 h treatment). (B) WRE/CMV-Renilla β-catenin reporter ratios were obtained for each cell line. Fold changes relative to the DMSO control-treated samples are shown, which are arbitrarily set to 1. Only significant changes (unpaired t-test) are shown (mean ± SD, n = 3, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; 48 h treatment). See also Supplemental Fig. S8 showing absolute AXIN2 and β-catenin reporter levels and Supplemental Fig. S9.

Taken together, these results show that tankyrase inhibition results in some AXIN accumulation in basically all HCC lines tested, while effects on β-catenin accumulation and signaling are non-apparent or modest, respectively.

Colony formation capability of HCC lines following tankyrase inhibition

Following three days of XAV939 treatment, HCC cell growth was unaltered in a MTT assay, even at higher 5 μM concentration (Fig. 5A). To test the effect of long-term treatment on lower cell numbers, we performed a colony formation assay treating HCC cells with XAV939 or IWR-1 for 2 weeks (Figs. 5B and Fig. S10). Among the β-catenin mutant lines, HepG2 and SNU398 were strongly inhibited in colony formation. As both these lines retained high levels of β-catenin signaling following tankyrase inhibition, this growth reduction is most likely the consequence of other cellular processes regulated by tankyrases, such as telomere maintenance, Hippo signaling, mitosis or DNA strand break repair30,33–35, or off-target effects of especially XAV939 on other cellular proteins, such as poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases PARP1 and PARP224,36. Among the AXIN1-mutant cell lines a modest but significant reduction in colony numbers was observed, especially using 5 μM XAV939 and IWR-1. For PLC/PRF/5 this may be attributed to reduced β-catenin signaling, while this is less obvious for Hep3B and SNU449. Lastly, among the non-mutant lines SNU182 was unaffected by tankyrase inhibition. Huh7 was clearly inhibited in colony formation with XAV939, but not using IWR-1, which is in line with the observed effects on β-catenin signaling for both compounds. HepaRG showed reduced numbers, which may be partially explained by reduced β-catenin signaling.

Figure 5.

Effect of tankyrase inhibitor XAV939 on the viability and colony formation capacity of HCC lines. (A) HCC cell lines were treated with XAV939 at 1 μM or 5 μM for three days followed by a MTT-assay (n = 4). No statistical significant growth reduction was observed (unpaired t-test). (B) Fold changes observed in a colony formation assay following XAV939/IWR-1 treatment. Only significant changes are shown (mean ± SD, n = 6, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; unpaired t-test).

Collectively, these findings suggest that tankyrase inhibition can inhibit the growth of several HCC cell lines when plated at low density. Not in all cases can the growth suppressing effects be linked to β-catenin signaling (e.g. HepG2 and SNU398). Tankyrase inhibition is however less effective when initiated with higher cell concentrations, as shown in the MTT-assay.

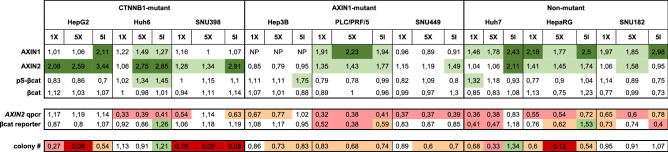

Table 1 summarizes all the fold changes that were observed following tankyrase inhibition in western blot, β-catenin signaling and colony formation analyses.

Table 1.

Summary of western blot, β-catenin signaling and colony formation analyses.

Fold changes relative to controls for each analysis are depicted and color-coded. Significant increases are shown in green colors, while decreases are shown in orange/red colors. 1X is 1 μM XAV939; 5X is 5 μM XAV939; 5I is 5 μM IWR-1.

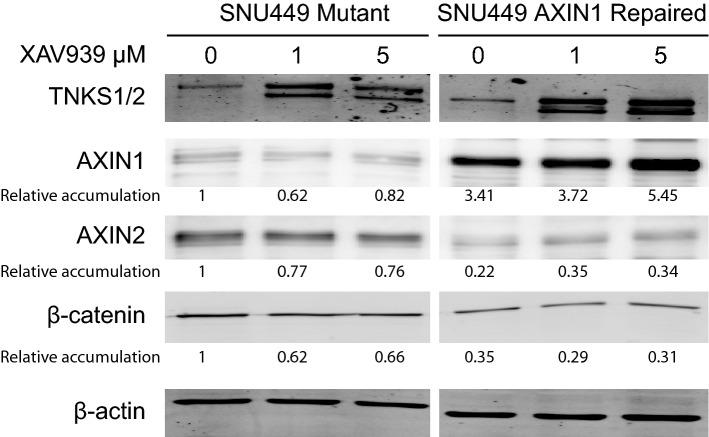

Restoring full-length AXIN1 expression in SNU449 cells reduces AXIN2 expression, but has overall minimal effects on cell behavior

To more directly investigate the consequences of AXIN1 mutation for supporting β-catenin signaling and liver cancer growth, we used CRISPR-Cas9 technology to repair the homozygous p.R712* mutation present in SNU449 cells. This truncating mutation removes the C-terminal DIX domain that is essential for AXIN1 to form higher order structures through multimerization and fulfil its function in β-catenin regulation37,38. We successfully obtained several independent clones with complete repair of AXIN1 (Supplemental Fig. S11A). Protein expression levels are 2–threefold higher compared to unrepaired clones, which can be attributed to higher expression levels of AXIN1 RNA (Figs. 6 and Fig. S11B). The latter is most likely resulting from nonsense-mediated decay of the mutant transcript in the parental line. Importantly, all repaired clones show a significant reduction in AXIN2 expression, in line with an improved β-catenin turnover (Fig. 6 and Supplemental Fig. S11C). When AXIN1-repaired cells are treated with XAV939, they show a clear accumulation of AXIN1, in contrast to unchanged levels of the mutant protein (Fig. 6). Thus, we successfully resulted in restoring AXIN1 expression in SNU449 cells, which was accompanied by reduced expression of the β-catenin target gene AXIN2.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of AXIN1-repaired SNU449 cells. At baseline (0 μM XAV939) the AXIN1-repaired SNU449 cells show increased levels of AXIN1, while AXIN2 and total β-catenin levels are decreased, indicating that AXIN1 contributes to increased β-catenin turnover. Following XAV939 treatment at indicated dosages, only a clear accumulation is observed for the AXIN1-repaired protein. For this experiment the AXIN1-repaired SNU449 clone-20 was compared with control clone-2. All relative band intensities are compared to this latter clone, which were arbitrarily set to 1.

The fact that we successfully obtained SNU449 cells with normalized AXIN1 expression also highlights that its mutation is not essential to sustain growth in culture, which was confirmed by comparable cell doubling times in the AXIN1-repaired clones with the parental line (Supplemental Fig. S12). AXIN1 has also been functionally linked to other proteins relevant for tumorigenesis, such as MYC, SMAD3 and TP5339–42. To determine in an unbiased manner the consequences of restoring AXIN1 expression in SNU449 cells, we subjected 3 repaired clones and 3 controls to RNA sequencing. Surprisingly, only 5 genes were significantly altered in expression including AXIN2 (Supplemental Table S2).

In conclusion, the analyses of the AXIN1-repaired SNU449 cells show that in this cell line the AXIN1 mutation has minimal effects on cell behavior and gene expression. Importantly, reduced expression of the well-established β-catenin target gene AXIN2 is consistently seen.

Discussion

Inappropriate activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling has been reported frequently in HCC. This has been mainly attributed to somatic mutations in the CTNNB1 gene (20–25%)3,5–7,9. A second common mechanism originally considered to lead to enhanced β-catenin signaling, is mutational inactivation of AXIN1 observed in about 10% of HCCs, putting it among the most frequently mutated genes in HCC3,5–7,9. Given its activity in the β-catenin destruction complex this was a logic assumption, however several reports have suggested that AXIN1 mutation leads to liver cancer in the absence of increased β-catenin signaling10–12. Recently, HCC formation in mice following mutation of AXIN1 was however shown to strongly dependent on functional β-catenin15, but as argued by others only in the context of simultaneous MET activation16. Hence, the issue whether AXIN1 mutation leads to activation of β-catenin signaling is still under debate16,17. In addition, the AXIN proteins have gained substantial interest in cancer research because their activity in the β-catenin destruction complex can be increased by tankyrase inhibitors, which thus may serve as a therapeutic option to reduce the growth of β-catenin-dependent cancers. Here, using a panel of 9 HCC cell lines with specific mutations in components of the β-catenin signaling pathway, we have investigated both aspects of AXIN biology.

The conclusion that AXIN1-mutant HCCs develop without β-catenin activation is largely based on expression profiling using a 23-β-catenin target gene signature12. Most AXIN1-mutated HCCs clustered in a group with no evident β-catenin activation program, and only about 20% in a group with weak activation. Interestingly, these same groups also show an enrichment in CTNNB1 mutations within armadillo repeats 5 and 6 (i.e. K335, W383, N387), for which we have recently unequivocally shown that they are efficient inducers of HCC development in mice, associated with a weak but significant activation of β-catenin signaling8. Expression profiling of tumor tissues has the inherent shortcoming that average expression is determined of a heterogeneous group of cells, including contaminating normal cells. Small but biologically relevant increases of β-catenin signaling, like the ones imposed by armadillo repeat mutant β-catenin, in a subset of cells can easily be missed. Likewise we feel that it is difficult to use expression profiling to fully exclude increased β-catenin signaling in AXIN1-mutated cancers.

The same holds true for immunohistochemical demonstration of nuclear β-catenin. AXIN1-mutant HCCs predominantly show an exclusive membranous β-catenin staining10–12,15, indeed suggesting that there is no nuclear signaling. However, this is also observed in tumors carrying oncogenic CTNNB1 mutations within the armadillo repeats and a subset of S45-mutant cancers8,43, while these clearly lead to enhanced signaling. Thus, although nuclear accumulation of β-catenin is a reliable predictor of active signaling, its absence does not exclude that a low level of biologically relevant signaling is active44. It shows that both genetic profiling and IHC have their shortcomings to unambiguously determine the absence of nuclear β-catenin signaling.

Our analyses show that all three AXIN1-mutant HCC cell lines have increased β-catenin reporter activity (Supplemental Fig. S8)14. Furthermore, we show that AXIN1 knockdown in three non-mutant lines leads to enhanced signaling, in accordance with other reports12,15. In the reverse experiment in which we restore AXIN1 expression in SNU449 cells, we consistently observe reduced expression of the β-catenin target gene AXIN2. Taken together, this shows that AXIN1 mutation leads to a modest increase of β-catenin signaling that may be relevant for hepatocellular tumorigenesis.

In this respect, several examples have been presented in the literature showing that minor alterations in the level of β-catenin signaling can have profound biological effects4,45–47. In case of hepatocellular cancer, Buchert et al. have shown that late-onset hepatocellular tumors were present in all mice carrying a hypomorphic APC mutation associated with just a modest increase in β-catenin signaling, while tumor formation was absent or largely prevented with slightly increased or decreased signaling45. This narrow window of signaling effective in mouse liver cancer formation highlights the importance of low level signaling for some cancer types and shows that it is difficult to fully exclude a role for β-catenin signaling.

AXIN1-mutant tumors depend to a large extent on AXIN2 to counterbalance signals that induce β-catenin signaling, as shown by the strong increase in β-catenin reporter activity that we observe after AXIN2 knockdown, comparable to levels seen with APC siRNA. Hence, they are expected to be more prone to signal in conditions that normally activate the β-catenin signaling pathway. Most liver cancers emerge in patients with chronic liver injury, inflammation and cirrhosis. Under such harsh circumstances, the modest increase in β-catenin signaling present in AXIN1-mutant cells may impose a selective advantage, for example by more readily inducing proliferation, survival or maintenance of stem cell characteristics. Nevertheless, it is clear that AXIN1 mutation by itself is not a strong driver of liver tumorigenesis. Deletion of AXIN1 in the mouse liver only leads to few tumors with late onset11,12, implying that other oncogenic hits are required to successfully initiate tumor formation. This notion is also supported by the minimal changes we observe in the AXIN1-repaired SNU449 cells. Apparently, this cell line does not depend anymore on the AXIN1 mutation to grow efficiently, at least using the culture conditions that we tested thus far. RNA sequencing analysis also shows that besides β-catenin signaling no routes previously linked to AXIN1 are clearly affected, e.g. MYC, SMAD3 and TP5339–42. As reported by others, it is also clear that AXIN1-mutant HCCs follow a different route to tumorigenesis than the ones carrying oncogenic β-catenin mutations, and may more heavily depend on the activation of other signaling pathways12.

In our HCC panel, tankyrase inhibition led to some AXIN1 and/or AXIN2 accumulation in all lines tested, except Hep3B. In accordance with previous reports investigating β-catenin mutant CRC lines24–26, the β-catenin mutant HCC cell lines retain a high level of nuclear β-catenin signaling. Significant reductions in β-catenin signaling are observed in several of the AXIN1/non-mutant lines tested. This reduction is however not sufficient to significantly affect their growth in a short-term MTT-assay. This seems to contradict our previous study where all HCC cell lines were inhibited after siRNA-mediated β-catenin knockdown14. However, in this latter study we reached more than 80% reduction in total β-catenin protein levels, which is in strong contrast to basically unaltered levels in our current study.

Using a colony formation assay we observe significant reductions in colony numbers in 7 out of 9 lines, albeit modest in some (Hep3B, PLC/PRF/5, and SNU449). Not in all cases can this be easily linked to effects on β-catenin signaling, like the strong inhibitory effect on colony formation we observe for HepG2 and SNU398, despite retaining high levels of signaling. For other lines like Huh7, reduced β-catenin signaling clearly associates with reduced colony formation, while this may be somewhat the case for PLC/PRF/5 and HepaRG. Tankyrases have however also been linked to several other cellular processes such as telomere maintenance, Hippo signaling, mitosis and DNA strand break repair30,33–35, all processes that may affect colony formation when altered by tankyrase inhibition. Therefore, the reduced colony numbers that we observe for some lines, are likely explained by a combination of factors, in which the correct explanation will be different for each cell line or tumor under investigation. Another factor to take into account when evaluating the mechanism of tankyrase inhibition, are the off-target effects of various inhibitors, e.g. on other PARP enzymes24,36. These will become more apparent at higher concentrations, and ideally studies should be performed at inhibitor concentrations that just lead to a (sub)maximum accumulation of the tankyrase enzymes. Overall our study suggests that tankyrase inhibition at such concentrations is unlikely to contribute to HCC treatment as monotherapy exclusively through reduction of β-catenin signaling. A potential exception could be the rare subset of HCCs carrying APC mutations leading to high level signaling of wild-type β-catenin9,48,49.

In conclusion, using a panel of nine HCC cell lines we observe that all three AXIN1-mutant lines display a clearly increased activity in a β-catenin reporter assay. Repair of the AXIN1 mutation in SNU449 confirms this observation as it results in reduced activation of the β-catenin target gene AXIN2. In the three non-mutant lines reducing AXIN1 levels also in all cases leads to enhanced signaling. Overall, these analyses show that AXIN1 mutation or inactivation leads to enhanced β-catenin signaling in HCC, questioning the strong statements that have been made in this regard. We also show that AXIN1 and AXIN2 work synergistically to control β-catenin signaling. While in the AXIN1-mutant lines, AXIN2 is solely responsible for keeping signaling in check, in the non-mutant lines both AXIN proteins contribute to β-catenin regulation to varying levels. Lastly, at concentrations that inhibit tankyrase activity some HCC lines were clearly affected in colony formation, but in most cases apparently independent from effects on β-catenin signaling.

Methods

Cell lines

CTNNB1-mutant HepG2, Huh6, SNU398, AXIN1-mutant Hep3B, PLC/PRF/5, SNU449 and non-mutant HepaRG, Huh7, SNU182 HCC and CRC cell line SW480 were cultured as reported previously14. The term “non-mutant” is used throughout the paper to indicate that these lines do not contain mutations in genes known to be linked to β-catenin signaling. Identity of all cell lines and clones thereof, was confirmed by the Erasmus Molecular Diagnostics Department, using Promega Powerplex-16 STR genotyping in October 2018. All cell lines tested negative for mycoplasma. Supplemental Table S1 provides official cell line names, RRID-numbers and gene mutations related to β-catenin signaling.

Reagents

XAV939 and IWR-1 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Antibodies used: β-catenin (610154, BD Transduction Laboratories), phospho-β-catenin (Ser33/37) (#2009, Cell Signaling Technology), AXIN1 (#2087 and #3323 Cell Signaling Technology; AF3287 R&D systems), AXIN2 (#2151, Cell Signaling Technology), Tankyrase-1/2 (sc-365897, Santa Cruz), β-actin (sc-47778, Santa Cruz). Anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IRDye-conjugated secondary antibodies (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, USA) and anti-rabbit-HRP (P044801-2, Dako) were used for western blot analysis.

β-catenin reporter assays

The β-catenin reporter assays were performed basically as previously described46. In short, we plated 5 × 104 cells per well on 24-well plates, which were transfected with 250 ng Wnt Responsive Element (WRE) vector and 10 ng CMV-Renilla using FuGENE HD or Lipofectamin 2000 Transfection Reagent. We measured luciferase activities and normalized the data for the transfection efficiency by using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay system. Following normalization, WRE/CMV-Renilla ratios are obtained. For the data presented in Supplemental Figs. S2, S8B and S9 also a Mutant Responsive Element (MRE) control vector was transfected in independent wells to obtain WRE/MRE ratios.

MTT assay

After incubation with XAV939 for 72 h, cells were analyzed by MTT assay as previously reported14. The mean and standard error were calculated for each condition.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed and run for fluorescent western blotting analysis as previously reported14. Results were visualized with Odyssey 3.0 software. For AXIN1, AXIN2 and pS33/37-β-catenin western blot analysis we used Immobilon ECL Ultra HRP substrate (MerckMillipore). Membranes for ECL detection were blocked and incubated using Immobilon Block-FL reagent (MerckMillipore). Original western blot images are presented in Supplemental Fig. S13.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were seeded on Nunc Lab-TekII CC2 Chamber Slides (Thermo-Fisher Scientific). After 16 h treatment with 1 µM XAV939 or DMSO, cells were washed with PBS, fixed in PBS-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized with PBS-0.2% Triton X-100 solution for 5 min and blocked with PBS containing 3% BSA for 30 min. Samples were incubated with primary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h, followed by PBS-Tween 20 0.05% washes and incubation with appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 h. Primary antibodies were diluted as follows: AXIN1 (AF3287, 1:100); AXIN2 (#2151, 1:200); Tankyrase-1/2 (sc-365897, 1:200). The following secondary reagents were used: Donkey anti-Goat-Alexa 647 (#A-21447), Donkey anti-Rabbit-Alexa 488 (#A-21206), Donkey anti-Mouse-Alexa 594 (#A-21203); all from Invitrogen, at 1:500 dilution. Slides were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (H-1200, Vector Laboratories). Images were generated using a Zeiss LSM510META confocal electroscope.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis were performed as described previously8,14,50. In short, RNA was isolated with a Machery-NucleoSpin RNA II kit (Bioké, Leiden, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and quantified using a Nanodrop ND-1000 (Wilmington, DE, USA). CDNA was prepared from total RNA using a cDNA Synthesis Kit (TAKARA BIO INC). Quantitative PCR was performed using Sensimix SYBRGreen (Applied Biosystems) or TaqMan (AXIN1; Hs00394718_m1, AXIN2; Hs00610344_m1, GAPDH; Hs02786624-g1) Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems). Analyses were performed using the StepOne Real-Time PCR System and the StepOnev2.0 software (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). All expression levels are depicted relative to the expression of GAPDH. Primer sequences are provided in Supplemental Table S3.

Gene knockdown by small interfering RNA (siRNA)

SiRNA-mediated gene knockdown was performed as reported previously14,50. Smartpool ON-TARGETplus siRNAs targeting AXIN1, AXIN2 or APC were purchased from Dharmacon (Supplemental Table S4). The ON-TARGETplus Non-targeting siRNA #2 was used as negative control. Cells were reverse-transfected in a 24-well plate using a total of 0.8 µl DharmaFECT formulation 4 (Thermo-Fisher Scientific) and 25 nM of each siRNA per well. Following 72 h incubation, the effect of knock-down was tested by qRT-PCR. Alternatively, for combined siRNA/β-catenin reporter assays, the siRNAs were co-transfected with WRE or MRE vectors and CMV-Renilla using lipofectamin 2000, and measured after 48 h.

Colony formation assay

After trypsinization, 500–2500 cells for each cell line were seeded in 6-well plates and were cultured in complete DMEM medium containing 1 µM or 5 µM XAV939, 5 µM IWR-1 or DMSO as control. For each treatment and cell line 6 wells were used. Medium was changed every three days. Two weeks later, the cells were washed with PBS, fixed in 4% PBS-buffered paraformaldehyde for 10 min and stained with crystal violet solution and counted (Gelcount, Oxford Optronix Ltd.)51.

CRISPR/Cas9 mediated repair of AXIN1 mutation in SNU449 cells

CRISPR/Cas9 repair of the AXIN1 mutations was performed as reported previously8. A single guide RNA (sgRNA) encompassing the homozygous c.2134C>T AXIN1 mutation present in SNU449 cells was designed and cloned into pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (PX458), a gift from Feng Zhang (Addgene plasmid # 48138) using standard procedures. To repair this mutation a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) was ordered as Ultramer (Integrated DNA Technologies). Both the sgRNA and ssODN are described in Supplemental Table S5. Transfections were performed with the Amaxa Cell Line Nucleofector-Kit-V (Lonza) and Nucleofector-IIb device according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, 5 × 106 SNU449 cells were cotransfected with 2 µg PX458 and 2 µg ssODN. After nucleofection, complete DMEM medium with 7.5 µM RAD51-stimulatory compound-1 (RS-1, Sigma-Aldrich) was used for cell culture. After 48 h, GFP positive cells were sorted by FACS and seeded as single cells in 96-well plates. DNA from clones grown successfully from single cells was isolated using the QuickExtract DNA Extraction Solution (Epicentre). For each clone, a PCR product encompassing the mutation was subjected to sequencing.

RNA extraction, Ilumina library preparation and sequencing

The RNA sequencing procedure was performed as previously described52.Total RNA was isolated with the Machery-NucleoSpin RNA II kit (Bioké, Leiden, The Netherlands) and quantified using a Nanodrop ND-1000 (Wilmington, DE, USA). RNA quality was checked using a RNA Pico chip on the Agilent Bioanalyzer. Library was constructed and sequenced with an Illumina HiSeqTM2000 (GATC Biotech, Konstanz, Germany). Briefly, the mRNA was enriched using oligo-dT magnetic beads, followed by fragmentation (about 200 bp). Then first strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer-primers and the second strand was further synthesized in a reaction buffer including dNTPs, RNase H and DNA polymerase I. Double stranded cDNA was purified with magnetic beads. Then, the 3′-end single nucleotide A (adenine) was added and adapters were ligated to the fragments which were enriched by PCR amplification.

RNA-sequencing analysis

RNA-seq data of control and AXIN1-repaired SNU449 samples (n = 3 each) was analyzed using UCSC human genome build hg38 and GENCODE annotation release 26 (GRCh38). FASTQC (v0.11.5)53 was applied on the single-end FASTQ files for quality control, both before and after running trimmomatic (v0.36)54, which removed TrueSeq adapter sequences. STAR (v2.5.3a) was used as aligner, with 2-pass mapping for each sample separately55. Mapping quality plot was generated and checked based on sambamba Flagstat (v0.6.7) statistics56. Count files, with the number of reads for each gene were created with subread FeatureCounts (1.5.2)57. Settings of different tools can be seen in Supplemental Table S6. R (version 3.4.3) was used for further statistics calculation and data visualizations. Differential expression analysis were performed with condition ‘Repaired’ (n = 3) versus ‘Mutated’ (n = 3) using the DESeq2 package (v1.18.1)58 and the Wald-test. A significance cut-off of 0.05 on the adjusted P-value was utilized, using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. The RNA-sequencing data from this study have been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)-database under the accession number GSE119001.

Statistical analysis

All results are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were carried out using software GraphPad Prism version 8.4.1 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, California, USA). Differences were considered significant at a P value less than 0.05 (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by a China Scholarship Council PhD fellowship to Wenhui Wang (File No. 201306190123), Pengyu Liu (File No. 201408220029), Shan Li (File No. 201408060053), Ruyi Zhang (File No. 201808530490) and Shanshan Li (File No. 201909370083), and to Wenhui Wang a Fundamental Research Fund for the Central Universities (2632019PY04) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81902480).

Author contributions

W.W. and P.L. performed the majority of experimental work as well as data analysis and authored the manuscript. M.L., S.L., R.Z. and S.L. assisted with the experiments. W.S.v.d.G. and H.J.v.d.W. analyzed the raw data generated by RNA sequencing. M.P.P. supervised the project and improved the manuscript. R.S. coordinated the project and participated in authoring of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. The RNA-sequencing data from this study have been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)-database under the Accession Number GSE119001.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Wenhui Wang and Pengyu Liu.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-87091-4.

References

- 1.Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2012;379:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sherman M. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Epidemiology, surveillance, and diagnosis. Semin. Liver Dis. 2010;30:3–16. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahmani R, Just PA, Perret C. The Wnt/beta-catenin pathway as a therapeutic target in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2011;35:709–713. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albuquerque C, Bakker ER, van Veelen W, Smits R. Colorectal cancers choosing sides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer. 2011;1816:219–231. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zucman-Rossi J, Villanueva A, Nault JC, Llovet JM. Genetic landscape and biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1226–1239. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang W, Pan Q, Fuhler GM, Smits R, Peppelenbosch MP. Action and function of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in the progression from chronic hepatitis C to hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. 2017;52:419–431. doi: 10.1007/s00535-016-1299-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Network CGAR. Comprehensive and integrative genomic characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. 2017;169:1327–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu P, et al. Oncogenic mutations in armadillo repeats 5 and 6 of beta-catenin reduce binding to APC, increasing signaling and transcription of target genes. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1029–1043. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.11.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulze K, et al. Exome sequencing of hepatocellular carcinomas identifies new mutational signatures and potential therapeutic targets. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:505–511. doi: 10.1038/ng.3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zucman-Rossi J, et al. Differential effects of inactivated Axin1 and activated beta-catenin mutations in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Oncogene. 2007;26:774–780. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng GJ, et al. Conditional disruption of Axin1 leads to development of liver tumors in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1650–1659. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abitbol S, et al. AXIN deficiency in human and mouse hepatocytes induces hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of beta-catenin activation. J. Hepatol. 2018;68:1203–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satoh S, et al. AXIN1 mutations in hepatocellular carcinomas, and growth suppression in cancer cells by virus-mediated transfer of AXIN1. Nat. Genet. 2000;24:245–250. doi: 10.1038/73448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang W, et al. Blocking Wnt secretion reduces growth of hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines mostly independent of beta-catenin signaling. Neoplasia. 2016;18:711–723. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qiao Y, et al. Axis inhibition protein 1 (Axin1) deletion-induced hepatocarcinogenesis requires intact beta-catenin but not notch cascade in mice. Hepatology. 2019;70:2003–2017. doi: 10.1002/hep.30556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilgenkrantz H, Perret C. Letter to the editor: Comment on Qiao et al. Hepatology. 2019;70:763–764. doi: 10.1016/S0618-8278(19)31520-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X, Monga SP, Calvisi DF. Reply. Hepatology. 2019;70:764–765. doi: 10.1016/S0618-8278(19)31521-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, et al. RNF146 is a poly(ADP-ribose)-directed E3 ligase that regulates axin degradation and Wnt signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:623–629. doi: 10.1038/ncb2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callow MG, et al. Ubiquitin ligase RNF146 regulates tankyrase and Axin to promote Wnt signaling. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e22595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thorvaldsen TE, Pedersen NM, Wenzel EM, Stenmark H. Differential roles of AXIN1 and AXIN2 in Tankyrase inhibitor-induced formation of degradasomes and beta-catenin degradation. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0170508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mariotti L, Pollock K, Guettler S. Regulation of Wnt/beta-catenin signalling by tankyrase-dependent poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and scaffolding. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017;174:4611–4636. doi: 10.1111/bph.14038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bao R, et al. Inhibition of tankyrases induces Axin stabilization and blocks Wnt signalling in breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e48670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Busch AM, et al. Evidence for tankyrases as antineoplastic targets in lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:211. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang SM, et al. Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature. 2009;461:614–620. doi: 10.1038/nature08356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka N, et al. APC mutations as a potential biomarker for sensitivity to tankyrase inhibitors in colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017;16:752–762. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lau T, et al. A novel tankyrase small-molecule inhibitor suppresses APC mutation-driven colorectal tumor growth. Can. Res. 2013;73:3132–3144. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waaler J, et al. A novel tankyrase inhibitor decreases canonical Wnt signaling in colon carcinoma cells and reduces tumor growth in conditional APC mutant mice. Can. Res. 2012;72:2822–2832. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schatoff EM, et al. Distinct colorectal cancer-associated APC mutations dictate response to tankyrase inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:1358–1371. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma L, et al. Tankyrase inhibitors attenuate WNT/beta-catenin signaling and inhibit growth of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:25390–25401. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia J, et al. Tankyrase inhibitors suppress hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth via modulating the Hippo cascade. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0184068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorvaldsen TE. Targeting tankyrase to fight WNT-dependent tumours. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017;121:81–88. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martino-Echarri E, Brocardo MG, Mills KM, Henderson BR. Tankyrase inhibitors stimulate the ability of tankyrases to bind axin and drive assembly of beta-catenin degradation-competent axin puncta. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0150484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagy Z, et al. Tankyrases promote homologous recombination and check point activation in response to DSBs. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1005791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang P, Coughlin M, Mitchison TJ. Tankyrase-1 polymerization of poly(ADP-ribose) is required for spindle structure and function. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:1133–1139. doi: 10.1038/ncb1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith S, Giriat I, Schmitt A, de Lange T. Tankyrase, a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase at human telomeres. Science. 1998;282:1484–1487. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lum L, Chen C. chemical disruption of wnt-dependent cell fate decision-making mechanisms in cancer and regenerative medicine. Curr. Med. Chem. 2015;22:4091–4103. doi: 10.2174/0929867322666150827094015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bienz M. Signalosome assembly by domains undergoing dynamic head-to-tail polymerization. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014;39:487–495. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gammons M, Bienz M. Multiprotein complexes governing Wnt signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2018;51:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arnold HK, et al. The Axin1 scaffold protein promotes formation of a degradation complex for c-Myc. EMBO J. 2009;28:500–512. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rui Y, et al. Axin stimulates p53 functions by activation of HIPK2 kinase through multimeric complex formation. EMBO J. 2004;23:4583–4594. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Q, et al. Axin determines cell fate by controlling the p53 activation threshold after DNA damage. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:1128–1134. doi: 10.1038/ncb1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo X, et al. Axin and GSK3-control Smad3 protein stability and modulate TGF-signaling. Genes Dev. 2008;22:106–120. doi: 10.1101/gad.1590908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rebouissou S, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation of CTNNB1 mutations reveals different β-catenin activity associated with liver tumor progression. Hepatology. 2016;64:2047–2061. doi: 10.1002/hep.28638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fodde R, Tomlinson I. Nuclear beta-catenin expression and Wnt signalling: In defence of the dogma. J. Pathol. 2010;221:239–241. doi: 10.1002/path.2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buchert M, et al. Genetic dissection of differential signaling threshold requirements for the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in vivo. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Veelen W, et al. beta-catenin tyrosine 654 phosphorylation increases Wnt signalling and intestinal tumorigenesis. Gut. 2011;60:1204–1212. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.233460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bakker ER, et al. beta-Catenin signaling dosage dictates tissue-specific tumor predisposition in Apc-driven cancer. Oncogene. 2013;32:4579–4585. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guichard C, et al. Integrated analysis of somatic mutations and focal copy-number changes identifies key genes and pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:694–698. doi: 10.1038/ng.2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kan Z, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in hepatocellular carcinoma. Genome Res. 2013;23:1422–1433. doi: 10.1101/gr.154492.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li S, et al. Commonly observed RNF43 mutations retain functionality in attenuating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and unlikely confer Wnt-dependency onto colorectal cancers. Oncogene. 2020;39:3458–3472. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-1232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Theil AF, et al. Trichothiodystrophy causative TFIIEbeta mutation affects transcription in highly differentiated tissue. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017;26:4689–4698. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang W, et al. Oncogenic STRAP Supports Hepatocellular Carcinoma Growth by Enhancing Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling. Mol Cancer Res. 2019;17:521–531. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-18-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmieder R, Edwards R. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:863–864. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dobin A, et al. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tarasov A, Vilella AJ, Cuppen E, Nijman IJ, Prins P. Sambamba: Fast processing of NGS alignment formats. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2032–2034. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:923–930. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. The RNA-sequencing data from this study have been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)-database under the Accession Number GSE119001.