Abstract

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder which, despite recent therapeutic developments, leads to significant burden and morbidity, impacting on daily functioning, physical and mental health, and health-related quality of life. The objective of this study was to investigate the impact of new therapeutic approaches in the treatment of moderate to severe AD and quantify subsequent differences in disease and symptom control.

Methods

Data were drawn from the 2018 Adelphi US AD Disease Specific Programme™ (DSP™), a cross-sectional survey of physicians (n = 150) and their patients with a history of moderate to severe AD (n = 749, 52.7% female, 72.1% white, mean age 40.1 ± 16.3 years). Inadequately controlled AD as rated by the physician was defined as currently flaring, and/or deteriorating/changeable AD and/or physician dissatisfaction with disease control on current treatment.

Results

The overall inadequate control rate was 42.3%, an improvement from 58.7% as identified in the 2014 DSP survey. The proportion of inadequately controlled patients increased as physician subjective severity (ranked from mild through to severe) increased; 15.4% of patients classified as having mild disease were inadequately controlled, compared to 94.5% of patients classified with severe disease. Relative to patients with controlled disease, patients with inadequately controlled disease were more likely to be unemployed, reported more frequent flares, and had a greater burden of symptoms and worse quality of life measures including itch, stress, anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance (all p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Despite the introduction of new therapies, the burden and impact of AD and lack of symptom control, although reduced compared with previous studies, still remains high.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, Burden, Disease control, Patient-reported outcomes, Quality of life

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with a significant disease burden and impacts on daily functioning, physical and mental health, and health-related quality of life. |

| This study investigated key drivers of unmet need associated with inadequate disease control, identifying and focusing on symptoms that are most bothersome to patients. |

| What was learned from this study? |

| The burden and impact of AD and lack of symptom control, although reduced compared with previous studies, remains high despite the introduction of new therapies. |

| There remains a need for new approaches for the treatment and control of AD. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.13560500.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder characterized by eczematous skin lesions, itch, skin pain, and sleep disturbances, all of which can lead to significant burden [1–9]. AD usually first presents in early childhood and, whilst often outgrown, it can persist into or originate in adulthood, with fluctuations between periods of relative flares and quiescence. The prevalence of AD among adults in the USA has been reported at 7.2–9% [1–9]. Among patients whose AD persists into adulthood, a large proportion present with more severe or inadequately controlled disease, with one US study reporting that 38.8% had moderate disease and 8.1% had severe disease [9].

The clinical presentation of AD includes pruritus, xerosis, and eczematous lesions, and its pathology is characterized by interactions between skin barrier defects and immune dysregulation. AD is associated with a significant morbidity and impacts daily functioning, physical and mental health, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients, caregivers, and family [3, 4, 9].

Previous research conducted in the USA in 2015 examined the extent and consequences of inadequate disease control among adults with a history of moderate to severe AD [10]. However, this research was undertaken prior to the launch of new biologic and non-steroidal topical treatment options: the interleukin-4 receptor-blocking monoclonal antibody dupilumab, indicated for use in moderate to severe AD and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017, and the phosphodiesterase inhibitor crisaborole, a topical ointment for use in mild to moderate disease, approved in 2016 [11, 12].

The aim of the present study was to demonstrate the extent to which the level and burden of inadequate AD control remains following the introduction of these new treatment options. In addition, we examined the key drivers of remaining unmet need associated with inadequate disease control, identifying and focusing on symptoms that are most bothersome to patients.

Methods

Data Source and Model

Data were drawn from the Adelphi AD Disease Specific Programme™ (DSP™), a point-in-time real-world survey of physicians and their presenting adult patients with AD conducted in the USA from January to April 2018. DSPs are large, multinational studies collecting retrospective data using a non-interventional approach, designed to identify current disease management, and patient- and physician-reported disease impact. They are point-in-time surveys conducted in real-world clinical practice, and the methodology has been previously published and validated [13–15].

Physician Recruitment

Screening and recruitment of physicians reflected nationally representative samples subject to meeting the DSP inclusion criteria: primary care physicians (PCPs, including internal medicine specialists), dermatologists or allergists; with 3–36 years’ experience; practicing in the USA with active involvement in the pharmaceutical management of patients with AD; and who saw a minimum number of patients with moderate to severe (as assessed by the physician) AD per month (≥ 5 for PCP, ≥ 6 for dermatologists, and ≥ 15 for allergists/immunologists). Physicians were instructed to recruit the next five adult patients (18 years or older) with AD and a history of moderate to severe disease (physician’s subjective overall rating of severity) and complete a detailed patient record form/chart review (hereafter referred to as PRF) on each patient.

Patient Recruitment

For inclusion, patients were required to be aged 18 years or over, with a physician-confirmed diagnosis of AD, visited a participating physician during the survey collection period, and were not currently involved in a clinical trial for AD. All patients had a history of moderate to severe AD but could be mild, moderate, or severe as determined by the physician at the time of data collection. Physicians rated AD severity in response to the following question: “What is your overall assessment of the severity of atopic dermatitis (AD) symptoms in this patient currently, based on your own definitions of mild, moderate, and severe?” There was no restriction with regards to treatment received.

Physician-Reported Outcomes

Participating physicians completed information on patient demographics and clinical characteristics such as subjective assessment of current AD severity (mild, moderate, severe), day-to-day symptoms, presence and number of acute episodes (flares), symptoms experienced during a flare, body regions affected, body surface area affected (BSA), and all components of the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), which measures both the extent (area) and severity of AD (range 0–72, higher scores indicating greater severity) [16]. Physicians also provided details of currently prescribed AD therapies. Physicians reported on the presence of anxiety, depression, and stress based on the following statement: “Provide your assessment of this patient’s current status as a result of their AD against the below criteria, on a scale of 0–6 where 0 = none and 6 = severe” (cutoff > 0 indicating presence). Itch interference with daily living and sleep disturbance were evaluated by the physician according to the following question: “Based on your discussions with the patient or perceptions during the last week, how much interference has each of the following aspects of the patient’s condition caused to their activities of daily living (excluding work)?” with responses on a scale of 0 (“none at all”) to 4 (“extreme interference”).

Patient-Reported Outcomes

At the time of consultation, patients were invited to complete a voluntary patient self-completion (PSC) form, independently of the physician, and provided informed consent to participate. In order to assess real-world outcomes, PSCs collected data about patients’ condition including details on the number, severity, and degree of bother of symptoms both on a day-to-day basis and during a flare. Patients self-rated their current AD severity based on the following question: “How bad was your atopic dermatitis today?” with response options of mild, moderate, and severe. QoL was evaluated using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI; range 0–30, with higher scores indicating greater impact on QoL) [17]. The Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) evaluated the presence of AD signs and symptoms in the past week and their impact on sleep (range 0–28, higher scores indicating greater severity) [18]. The Work Productivity and Activity Index (WPAI) evaluated the effect of AD on productivity during the past 7 days (range 0–100, higher scores indicating greater severity) [19].

Ethics and Approval

The AD DSP™ was submitted for and received approval from the Freiburg International Ethics Committee in November 2017 (protocol AG8382). In addition, the study was conducted in accordance with all the relevant legislation at the time of data collection, including the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act 1996 [20] and Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act legislation [21]. Neither patient nor physician was asked to provide any identifiable personal identification when filling out the physician record form and the voluntary PSC questionnaire, completion of which provided informed consent to participate. Prior to receipt for analysis, all data were fully deidentified.

Analysis Groups

On the basis of physician assessment, patients were classified as having inadequately controlled or controlled AD, with inadequately controlled AD defined as either currently flaring AD; deteriorating or changeable AD; or physician dissatisfaction with current control, the last of these evaluated on a 1–7 scale (1 = extremely dissatisfied, 7 = extremely satisfied) with 1–3 classified as dissatisfied.

Statistical Analysis

Bivariate analysis compared inadequately controlled versus controlled patients, for demographic and clinical characteristics. Tests used were t test, chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test or Mann–Whitney test. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Multivariate analysis (stepwise logistic regression) was used to identify factors predictive of control. A logistic regression on control was run that initially included the demographic and clinical characteristics. The variable with the highest p value was removed and the regression re-run. This process was repeated until only variables with p < 0.05 remained. Only the final model is reported, which shows odds ratios (OR) and p values for each retained variable. An OR > 1 indicates that as the value of that variable increases, the odds of being controlled increase. Conversely, an OR < 1 indicates that as control decreases the variable increases. All analyses were performed using Stata 16.0.

Results

Population

In total, 60 PCPs, 70 dermatologists, and 20 allergists participated, who recruited 749 patients with AD for this study. Overall, 52.7% were female and 72.1% were white, mean age was 40.1 ± 16.3 years. Of these, 443 (59.1%) patients completed a PSC.

Number of Inadequately Controlled Patients

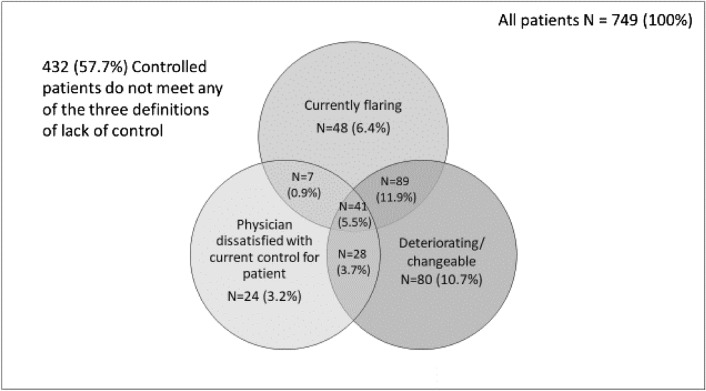

Three hundred and seventeen patients (42.3%) were identified as being inadequately controlled. These were classified as either deteriorating or changeable (n = 238; 31.8% of the total sample), currently flaring (n = 185; 24.7%), or physician dissatisfaction with current control (n = 100; 13.4%). These definitions were not mutually exclusive with some patients satisfying multiple criteria, the greatest overlap being between those reporting flares alongside deteriorating/changeable symptoms (n = 89; 11.9%). In total, 41 patients (5.5%) met all three criteria (Fig. 1). Of the 317 inadequately controlled patients, 75.1% were deteriorating or changeable, 58.4% were flaring, and physicians indicated dissatisfaction with current control in 31.6% of patients. All three criteria were met by 12.9% of all inadequately controlled patients.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of patients with inadequately controlled disease

Demographics

Demographic differences were observed between inadequately controlled and controlled patients. Patients with inadequately controlled disease were less likely to be in employment (64.9% vs 73.4%; p = 0.04) and had more flares in the past 12 months (2.1 ± 3.1 vs 1.2 ± 2.1; p < 0.0001) than those with controlled disease (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with AD

| Inadequately controlled | Controlled | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients, n (%) | 317 (42.3%) | 432 (57.7%) | – |

| % Male (%) | 46.7 | 47.7 | 0.8242 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 40.1 (17.1) | 40.0 (15.8) | 0.9530 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 25.7 (4.1) | 26.3 (4.7) | 0.0553 |

| % Employed | 64.9 | 73.4 | 0.0408 |

| % White/Caucasian (%) | 69.7 | 73.8 | 0.3076 |

| Physician subjective severity, n (%) | |||

| Mild | 40 (15.4%) | 220 (84.6%) | < 0.0001 (CH) |

| Moderate | 225 (51.8%) | 209 (48.2%) | |

| Severe | 52 (94.5%) | 3 (5.5%) | |

| IGA score, mean (SD) | 2.8 (0.7) | 2.1 (0.9) | < 0.0001 (TT) |

| Current BSA (SD) | 12.9 (14.3) | 10.1 (11.5) | 0.0035 |

| Current EASI score—all patients (SD) | 8.8 (8.5) | 5.7 (5.9) | < 0.0001 |

| EASI score—moderate to severe only, mean (SD) | 9.6 (8.8) | 8.0 (6.7) | 0.0329 (TT) |

| Number of flares in last 12 months, mean (SD) | 2.1 (3.1) | 1.2 (2.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.0 (0.3) | 0.0245 |

All data physician-reported

CH chi-squared, TT t test

Patients with inadequately controlled disease had higher BSA scores (12.9 ± 14.3 vs 10.1 ± 11.5; p = 0.0035) and EASI scores (8.8 ± 8.5 vs 5.7 ± 5.9; p < 0.0001) than those with controlled disease. Including currently moderate to severe patients only, EASI scores were 9.6 ± 8.8 for inadequately controlled patients (n = 275) compared to 8.0 ± 6.7 for adequately controlled patients (n = 208, p = 0.033).

The proportion of inadequately controlled patients increased as physician subjective severity (ranked from mild through to severe) increased (p < 0.0001). Of those classified as having mild disease, just 15.4% of patients were inadequately controlled compared with 84.6% of patients with controlled disease; whereas 94.5% of patients who were inadequately controlled were classified as having severe disease compared with only 5.5% of patients with controlled disease (Table 1).

Burden of AD in Inadequately Controlled Versus Controlled Patients

Bivariate analysis suggested that inadequately controlled patients had a higher burden of illness and a greater unmet need than those considered controlled (Table 2). A range of physician- and patient-reported parameters were worse in inadequately controlled patients compared with controlled patients, including depression, anxiety, stress, itch, sleep disturbance, POEM, DLQI, and WPAI scores (all p < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Bivariate analysis of outcomes

| All patients | Inadequately controlled | Controlled | p value (FE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression (n = 719) | 53.7% | 64.5% | 46.0% | < 0.0001 |

| Anxiety (n = 715) | 68.1% | 76.6% | 62.1% | < 0.0001 |

| Stress (n = 718) | 70.3% | 79.1% | 64.1% | < 0.0001 |

| Itch* (n = 743) | 63.4% | 81.3% | 50.2% | < 0.0001 |

| Sleep disturbance* (n = 738) | 39.3% | 58.3% | 25.4% | < 0.0001 |

| Mean POEMa (n = 438) | 10.4 | 14.3 | 7.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Mean DLQIb (n = 422) | 7.4 | 9.7 | 5.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Mean WPAIc (n = 252) | 19.9 | 26.5 | 16.1 | < 0.0001 |

*Interference with daily living

aPatient-Orientated Eczema Measure

bDermatology Life Quality Index

c% overall work impairment

Factors Associated with Inadequate Control

Regression analysis was undertaken to investigate the association between physician-perceived lack of control and physician-reported assessment of interference of aspects of AD on patients’ ability to work or study. Compared with controlled patients, inadequately controlled patients were more likely to be unemployed (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.39–0.87, p = 0.008), reported a higher number of flares (OR 1.11, 95% CI 1.02–1.20, p = 0.019), and reported interference due to itch (OR 2.72, 95% CI 1.67–4.42, p > 0.000) and sleep disturbance (OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.36–3.48, p = 0.001).

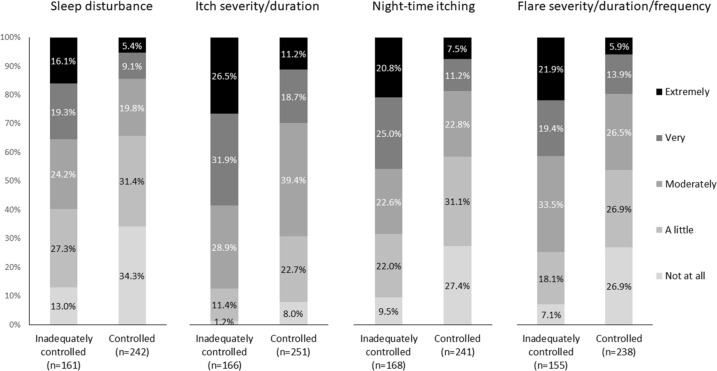

Comparing differences in physician-reported severity of symptoms and effect of AD between inadequately controlled and controlled patients, the former included a higher proportion reporting that their patients were very/extremely bothered by the effect of their AD on sleep disturbance (35.4% vs 14.5%, p < 0.0001), itch severity/duration (58.4% vs 29.9%, p < 0.0001), nighttime itching (45.8% vs 18.7%, p < 0.0001), and flare severity/duration/frequency (41.3% vs 19.7%, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Distribution in physician-reported symptom severity between inadequately controlled vs controlled patients

Specific issues associated with patient-reported symptomatic burden and effect of AD were investigated further (Table 3). It should be noted that although general itch severity/duration was the most common patient-reported symptom with 94.6% of patients bothered by itch severity/duration to some extent (either a little, moderately, very, or extremely bothered), the presence of itch in itself was not a significant factor driving the differences between inadequately controlled and controlled patients.

Table 3.

Distribution of reported symptoms and effect of AD in inadequately controlled vs controlled patients

| At all bothered by | Moderate/very/extremely bothered by | Most bothersome | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n (%) | Inadequately controlled, n (%) | Controlled, n (%) | p value (FE) | Total, n (%) | |

| n | 259 | 107 | 152 | 259 | |

| Itch severity/duration | 245 (94.6%) | 96 (89.7%) | 106 (69.7%) | 0.0001 | 104 (40.2%) |

| Size/severity of lesions (redness, thickness, raised areas, damage to skin from scratching) | 231 (89.2%) | 80 (74.8%) | 87 (57.2%) | 0.0038 | 28 (10.8%) |

| Location of lesions | 225 (86.9%) | 81 (75.7%) | 87 (57.2%) | 0.0024 | 22 (8.5%) |

| Number of different areas of the body affected | 217 (83.8%) | 71 (66.4%) | 78 (51.3%) | 0.0214 | 15 (5.8%) |

| Nighttime itching | 207 (79.9%) | 79 (73.8%) | 57 (37.5%) | < 0.0001 | 24 (9.3%) |

| Skin pain/soreness | 198 (76.4%) | 72 (67.3%) | 58 (38.2%) | < 0.0001 | 13 (5.0%) |

| Flare severity/duration/frequency | 195 (75.3%) | 81 (75.7%) | 66 (43.4%) | < 0.0001 | 18 (6.9%) |

| Sleep disturbance | 192 (74.1%) | 70 (65.4%) | 51 (33.6%) | < 0.0001 | 8 (3.1%) |

| Impact on your psychological wellbeing (stress, anxiety, low mood/depression) | 176 (68.0%) | 55 (51.4%) | 40 (26.3%) | < 0.0001 | 10 (3.9%) |

| Impact on your social interactions | 175 (67.6%) | 56 (52.3%) | 48 (31.6%) | 0.0012 | 6 (2.3%) |

| Impact on your ability to do your normal daily activities | 173 (66.8%) | 50 (46.7%) | 43 (28.3%) | 0.0026 | 3 (1.2%) |

| Impact on your personal/sexual relationships | 145 (56.0%) | 45 (42.1%) | 30 (19.7%) | 0.0002 | 6 (2.3%) |

| Impact on your ability to go to work/education | 145 (56.0%) | 37 (34.6%) | 31 (20.4%) | 0.0145 | 2 (0.8%) |

| Skin infections | 117 (45.2%) | 32 (29.9%) | 13 (8.6%) | < 0.0001 | |

The inadequately controlled group reported being bothered at least moderately by more aspects of their disease than the controlled patients (mean ± SD 8.5 ± 4.0 vs 5.2 ± 4.1, p < 0.0001) (Table 3). Significant differences in the proportion of patients were observed between inadequately controlled and controlled patients across all aspects of disease assessed (all p < 0.05). The most significant differences were observed in itch severity/duration (89.7% vs 69.7%, p < 0.0001), flare severity/duration/frequency (75.7% vs 43.4%, p = 0.0001), skin pain/soreness (67.3% vs 38.2%, p < 0.0001), nighttime itching (73.8% vs 37.5%, p < 0.0001), sleep disturbance (65.4% vs 33.6%, p < 0.0001), skin infections (29.9% vs 8.6%, p < 0.0001), and impact on psychological wellbeing (51.4% vs 26.3%, p < 0.0001), respectively.

In terms of the most bothersome symptom reported by patients, itch severity/duration was the most frequently mentioned (40.2%), regardless of whether the patient’s AD was considered to be controlled (46.1%) or inadequately controlled (31.8%). Size/severity of lesions (10.8%), nighttime itching (9.3%), and location of lesions (8.5%) were the next most bothersome symptoms reported by patients.

Discussion

Following the introduction of new therapeutic approaches, this study set out to investigate the remaining unmet need in respect of the degree of disease and symptom control in moderate to severe AD and to quantify changes in control compared with the situation prior to their introduction. This was achieved through comparing the data from the most recent cohort (2018) with the data obtained in the previous AD DSP™ survey dataset from 2015 [10], which followed the same methodology.

While the underlying demographic characteristics of this new patient cohort were similar to those observed in 2015, the proportion of inadequately controlled patients was lower (42% in 2018 vs 57% in 2015). One possible reason for this apparent reduction could be the availability of new therapies, including dupilumab in 2017 and crisaborole in 2016 [11, 12].

When we compare the control parameters in the new dataset with those in the previous study, there has been a clear change in the distribution of patients. While physician-reported dissatisfaction with control was similar in 2018 (13.4%) compared with the 2015 survey (13.9%), fewer patients were inadequately controlled as a result of flares in 2018 compared with 2015 (24.7% vs 44.9%), which could potentially be a result of improved symptomatic control. However, slightly more patients were stated as having deteriorating/changeable AD (31.8% in 2018 vs 26.9% in 2015), which could be a result of a shift away from patients being defined as currently flaring towards having more changeable symptoms.

The concept of disease control in inflammatory/chronic conditions like AD is a subjective and temporal measure. The terms “deteriorating/changeable disease” and “currently flaring” could be considered to be arbitrary, so distinctions between the two might be an artifact of how an individual physician defines flaring compared with deteriorating/changeable disease. By including different options in the survey, this allowed physicians to best describe the patient’s health status, allowing the authors to assess whether each patient could be considered uncontrolled. By combining these options into a single state of “uncontrolled disease” we resolve the issue of subjective description and definition highlighted above.

This point-in time survey was conducted 12–18 months after the introduction of new therapies; therefore their impact in clinical practice may have been restricted by issues such as reimbursement status, physician/patient awareness, and acceptance. As physicians have become more aware of and comfortable with the use of new therapies in the context of AD, and dosing strategies have evolved, uptake of these is likely to have increased. Further studies will be required to assess these trends over time. Therefore, although almost half of patients with AD (42%) in the current study were classified as having inadequately controlled disease, this proportion may have decreased at least somewhat over time as experience with new therapeutics grows and patients have the opportunity to be on new therapies for longer. Nevertheless, it is likely there remains an unmet need for more effective therapies for AD.

While the recruitment methodology, requiring physicians to include consecutively consulting patients, results in a pragmatic and representative sample of their patient population, this process may be biased towards patients who visit their treating physician more frequently. It should also be noted that the patient population included only patients who had a history of moderate to severe disease in the opinion of the recruiting physician. Patients who had only ever experienced mild disease were not included; therefore these data are not applicable to patients whose AD condition has only ever been mild. The completion of PSCs was voluntary; therefore patient-reported outcome measures were based only on patients who agreed to participate. Recall bias is a common limitation of surveys; however, this is not an issue for this research since patients responded according to how they felt on the day and wherever historical information was required of physicians they could refer to their records as necessary. As this was a non-interventional study, test scores were only collected if physicians knew the results prior to the consultation; they were not required to undertake any tests as part of the research. Therefore, some data points across different variables were unavailable.

Conclusion

Despite the introduction of novel therapies, the burden and impact of AD, the degree of patient- and physician-reported disease severity, and the lack of symptom control is still substantial. Although an apparent reduction in the overall proportion of patients reporting disease flares and classified with inadequately controlled moderate or severe disease was observed, there still remains a need for new approaches for the treatment and control of AD.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study, as well as the Rapid Service Fee for publication, was funded by LEO Pharma A/S.

Medical Writing, Editorial and Other Assistance

The authors would like to thank Gary Sidgwick PhD, an employee of Adelphi Real World, for medical writing support in preparation of this manuscript. He has no conflict of interest to report.

Authorship

All authors were involved in 1) conception or design, or analysis and interpretation of data; 2) drafting and revising the article; 3) providing intellectual content of critical importance to the work described; and 4) final approval of the version to be published, and therefore meet the criteria for authorship in accordance with the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) guidelines. In addition, all named authors take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Peter Anderson, James Piercy and Gary Milligan are employees of Adelphi Real World, a company that received research funding from LEO Pharma A/S. Andreas Westh Vilsbøll and Nana Kragh are employees by LEO Pharma A/S, who funded this study.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The AD DSP™ was submitted for and received approval from the Freiburg International Ethics Committee in November 2017 (protocol AG8382). In addition, the study was conducted in accordance with all the relevant legislation at the time of data collection, including the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act 1996 [18] and Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act legislation [19]. Neither patients nor physicians were asked to provide any identifiable personal identification when filling out the physician record form and the voluntary patient self-completion forms, completion of which provided informed consent to participate. Prior to receipt for analysis, all data were fully deidentified.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available. Data collection was undertaken by Adelphi Real World as part of an independent survey, entitled the Adelphi Atopic Dermatitis Disease Specific Programme (DSP™). All data that support the findings of this study are the intellectual property of Adelphi Real World. The analysis of the data presented in this study was funded by LEO Pharma A/S, who did not influence the original survey through either contribution to the design of questionnaires or data collection.

References

- 1.Silverberg JI, Garg NK, Paller AS, et al. Sleep disturbances in adults with eczema are associated with impaired overall health: a US population-based study. J Investig Dermatol. 2015;135:56–66. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic Dermatitis in America study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Investig Dermatol. 2019;139:583–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverberg JI, Wollenberg A, Egeberg A, et al. Worldwide prevalence and severity of atopic dermatitis: results from a global epidemiology survey. 2018. Presented at the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) 2018 Annual Meeting; September 12–16, 2018; Paris, France.

- 4.Simpson EL, Bieber T, Eckert L, et al. Patient burden of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD): insights from a phase 2b clinical trial of dupilumab in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunner PM, Silverberg JI, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Increasing comorbidities suggest that atopic dermatitis is a systemic disorder. J Investig Dermatol. 2017;137:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silverberg J, Garg N, Silverberg NB. New developments in comorbidities of atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2014;93:222–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbarot S, Auziere S, Gadkari A, et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in adults: results from an international survey. Allergy. 2018;73:1284–1293. doi: 10.1111/all.13401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckert L, Gupta S, Amand C, et al. Impact of atopic dermatitis on health-related quality of life and productivity in adults in the United States: an analysis using the National Health and Wellness Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121:340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei W, Anderson P, Gadkari A, et al. Extent and consequences of inadequate disease control among adults with a history of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2018;45(2):150–157. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ariëns LFM, Bakker DS, van der Schaft J, et al. Dupilumab in atopic dermatitis: rationale, latest evidence and place in therapy. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2018;9(9):159–170. doi: 10.1177/2040622318773686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deleanu D, Nedelea I. Biological therapies for atopic dermatitis: an update. Exp Ther Med. 2019;17:1061–1067. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, et al. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: Disease-Specific Programmes - a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(11):3063–3072. doi: 10.1185/03007990802457040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babineaux SM, Curtis B, Holbrook T, Milligan G, Piercy J. Evidence for validity of a national physician and patient-reported, cross-sectional survey in China and UK: the Disease Specific Programme. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8):e010352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Higgins V, Piercy J, Roughley A, et al. Trends in medication use in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a long-term view of real-world treatment between 2000 and 2015. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2016;9:371–380. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S120101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, et al. The eczema area and severity index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. EASI Evaluator Group. Exp Dermatol. 2001;10(1):11–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.100102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC. The Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure: development and initial validation of a new tool for measuring atopic eczema severity from the patients’ perspective. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(12):1513–1519. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.12.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reilly Associates. WPAI scoring. http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_Scoring.html. Accessed 9 June 2020.

- 20.Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Public law 104–191—AUG. 21, 1996. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-104publ191/pdf/PLAW-104publ191.pdf. Accessed 9 June 2020.

- 21.Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, enacted under title XIII of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Public Law 111–5—FEB. 17, 2009. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-111publ5/pdf/PLAW-111publ5.pd. Accessed 9 June 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available. Data collection was undertaken by Adelphi Real World as part of an independent survey, entitled the Adelphi Atopic Dermatitis Disease Specific Programme (DSP™). All data that support the findings of this study are the intellectual property of Adelphi Real World. The analysis of the data presented in this study was funded by LEO Pharma A/S, who did not influence the original survey through either contribution to the design of questionnaires or data collection.