Abstract

Changes in the microbiome in response to environmental influences can affect the overall health. Critical illness is considered one of the major environmental factors that can potentially influence the normal gut homeostasis. It is associated with pathophysiological effects causing damage to the intestinal microbiome. Alteration of intestinal microbial composition during critical illness may subsequently compromise the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier and intestinal mucosa absorptive function. Many factors can impact the microbiome of critically ill patients including ischemia, hypoxia and hypotension along with the iatrogenic effects of therapeutic agents and the lack of enteral feeds. Factors related to disease state and medication are inevitable and they are part of the intensive care unit (ICU) exposure. However, a nutritional intervention targeting gut microbiota might have the potential to improve clinical outcomes in the critically ill population given the extensive vascular and lymphatic links between the intestines and other organs. Although nutrition is considered an integral part of the treatment plan of critically ill patients, still the role of nutritional intervention is restricted to improve nitrogen balance. What is dismissed is whether the nutrients we provide are adequate and how they are processed and utilised by the host and the microbiota. Therefore, the goal of nutrition therapy during critical illness should be extended to provide good quality feeds with balanced macronutrient content to feed up the entire body including the microbiota and host cells. The main aim of this review is to examine the current literature on the effect of critical illness on the gut microbiome and to highlight the role of nutrition as a factor affecting the intestinal microbiome-host relationship during critical illness.

Keywords: Critical illness, gut microbiome, nutrition, paediatrics

INTRODUCTION

Changes in the gut microbiome in response to environmental influences can affect the overall health.[1,2,3] Critical illness is considered one of the major environmental influences that can impact the gut environment.[4] It is associated with pathophysiological effects causing damage to the intestinal microbiome. These include ischemia, hypoxia and hypotension along with the iatrogenic effects of therapeutic agents and the lack of enteral feeds.[5,6,7] As a result of alterations to the intestinal microbial composition, the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier and intestinal mucosa absorptive function is compromised.[8,9,10,11,12]

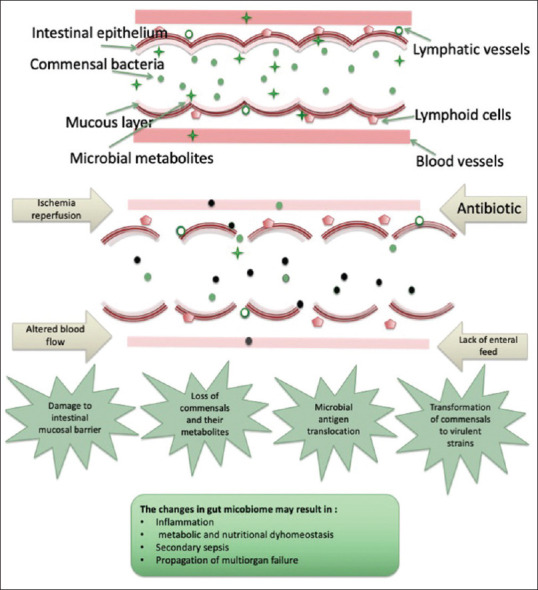

Generally, the intestinal microbiome of critically ill children and adults is characterised by low diversity.[13,14] Critically ill children and adults appear to be rapidly colonised with opportunistic pathogens.[14,15] Besides, a loss of intestinal anaerobic bacteria has been frequently detected during critical illness, and accordingly the colonic degradation capacity of undigested carbohydrates into lactic acid and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) may be affected.[16,17,18,19] The interaction between the host and intestinal microbiome is highly relevant to pathophysiology and outcomes in severe and critical illness. Damage to the intestinal mucosal lining in severe disease may lead to the translocation of bacteria or their fragments into the bloodstream and this may contribute to inflammation, sepsis, multi organ failure Multi-organ failure (MOF) and death.[20,21,22] The depletion of the normal gut microbial population and metabolites and alterations to the intraluminal gut environment is associated with adverse outcomes in critically ill adults.[23] Indeed the gut is seen as an important driver of organ failure in critical illness[24] [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

A summary of the changes that occur in the gut microbiome during critical illness. In response to acute insult, factors such as reperfusion, antibiotic therapy and the lack of enteral feed result in damage to the intestinal barrier and changes in microbial composition. Alterations to the gut microbiome are strongly related to the exacerbation of the inflammatory response, metabolic dysregulation sepsis and the propagation of multiorgan failure

FACTORS AFFECTING INTESTINAL MICROBIOME DURING CRITICAL ILLNESS

Disease state

The intestinal microbiome is altered in response to the pathophysiological effects of critical illness. The pro-inflammatory stimulation appears to influence the tight junctions between enterocytes and results in increased epithelial permeability, the infiltration of luminal antigens and the induction of intestinal inflammation.[20] Intestinal inflammation and hypoxia have a significant impact on modulating the gut microbiome and microbiota composition during critical illness.[8,9] Both promote a shift from commensal anaerobes to opportunistic pathogens.[8,9] Furthermore, intestinal inflammation alters the responses of gut hormones and neurotransmitters and accordingly impacts gut motility.[12,25] It was speculated that inflammation suppresses the expression of certain hormones such as peptide YY (PYY) by mature endocrine cells, resulting in impaired gut motility.[26] The activation of inflammatory cytokines and increased levels of luminal catecholamine has also been shown to promote the growth of pathogenic species.[27,28] Impaired mucosal immunity and decreased immunoglobulin A (IgA) production are other features of acute illness and are associated with decreased ability to eliminate intestinal pathogens.[27]

Medication

The pharmaceutical agents commonly used in intensive care unit (ICU) such as antibiotics, inotropic drugs and vasopressors are known to impact human microbiota.[7,8,9,29,30]

Critically ill patients are frequently treated with antibiotics. It has been estimated that the total antibiotic consumption in ICU settings is nearly ten times greater than in general hospital wards.[31] Several studies have recorded profound changes in gut microbial communities following the administration of antibiotic treatment, which can subsequently result in important functional alterations of the gut microbiome and increase susceptibility to gastrointestinal infections.[32,33] The effect of antibiotic exposure on gut microbiota has been widely investigated. The main phyla influenced by antibiotic treatment appear to be Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria.[34,35,36] In a study conducted on antibiotic-treated infants, a massive reduction in total bacterial densities was observed after antibiotic treatment, accompanied by delayed colonisation by beneficial species such as Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli, and induced colonisation by antibiotic-resistant strains.[37] The findings from these studies could explain the high prevalence of nosocomial infections with increased antibiotic consumption in critically ill patients.[38]

The alteration in the balance of gut microbiota following antibiotic treatment could be short-term or may last for a longer period. An example of the long-lasting effect of antibiotic use is reduced colonisation resistance against some pathogens such as Clostridium difficile.[34] As this population often receives extensive antibiotic treatment, it may, in addition to the functional loss of commensal species, affect the prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant genes within the intestinal microbiome.

Other therapeutic agents used in ICU settings are also known to impact the intestinal microbiome, including inotropic drugs that promote the growth of pathogens.[29,30] Vasopressors like calcium-channel blockers have recently been shown to inhibit the growth of commensal bacteria, however, the exact mechanism has not been established yet.[7]

Nutrition

Nutrition has an indirect effect on the gastrointestinal function of the host and thereby on health, mainly by influencing the composition and activity of the human gut microbiota. It is considered one of the major determinants of the intestinal microbial composition. The route of feeding greatly affects the gut microbial population.[39,40] Enteral nutrition (EN) helps to maintain the immunological function of the gastrointestinal tract; it decreases bacterial translocation and accordingly blunts the systemic inflammatory response.[41,42] Besides, early compared to delayed enteral feeding is associated with less bacterial translocation and better mucosal integrity.[43,44] In contrast, bowel rest, as associated with total parenteral nutrition (PN) or delayed EN, results in gastrointestinal mucosal atrophy, which compromises the integrity of the mucosal barrier and enhances exposure to bacteria and endotoxins.[41,45,46] The composition of EN is also known to greatly influence the colonisation, maturation and stability of the intestinal microbiota.[47] The effect of the dietary component on intestinal microbiota varies; it may promote the growth of opportunistic microbes while other dietary factors could endorse beneficial microbes.[48]

Dietary fibre is the primary energy source for most commensal species and, therefore, can directly impact their growth.[49] It is also the main substrate for the microbial production of important bacterial metabolites known to influence the host's health.[50] The effect of fibre supplementation on gut microbiota has been widely investigated in healthy subjects, and data showed that the main species influenced were Bifidobacteria, Lactobacilli, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Roseburia.[51,52,53,54,55] Nutrition status is also an important factor determining the diversity of the intestinal microbiome.[56] Therefore, the state of energy deficit, particularly during the acute phase of illness, might have a profound effect on the gut microbiota and environment.

CONTRIBUTION OF INTESTINAL MICROBIOTA TO THE HOST HEALTH

The gut microbiota use ingested dietary components (carbohydrates − mainly resistance starch, proteins and lipids) to generate energy for cellular processes and growth.[57] During the process of utilising these substrates, the microbiota produces several metabolites that influence host health and metabolism.[56,57]

Macronutrient metabolism

Preclinical data and animal studies have suggested possible mechanisms of the contribution of intestinal microbiota to the regulation of macronutrient metabolism.

Carbohydrates

The fermentation of polysaccharides (fibre) by anaerobic bacteria leads to the production of SCFAs, which are utilised by the host. Colonic epithelial cells derive up to 70% of their energy from the oxidation of butyrate.[58] The microbial gluconeogenesis from propionate reduces hepatic gluconeogenesis and promotes energy homeostasis.[59,60] Gut microbiota is also known to regulate glucose metabolism through the stimulation of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and PYY hormone secretions from intestinal L-cells.[61,62]

Protein

Gut microbiota contributes to host nitrogen balance through de novo synthesis of amino acids and intestinal urea recycling. Studies with radiolabelled tracers suggest that gut microbes synthesise nearly 20% of circulating threonine and lysine in healthy adult humans.[63] The intestinal microbiota also contributes to host nitrogen balance by participating in urea nitrogen salvaging.[10] Elevated urease expression in gut microbes results in the metabolism of urea in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract into ammonia and carbon dioxide. Some of the ammonia can be utilised for the microbial synthesis of amino acids. More importantly, the nitrogen generated during this process can re-enter the host circulation and serve as a substrate for synthetic processes.[10] Reduced urea recycling has been reported in germ-free animals and humans receiving antibiotic therapy.[64,65] Therefore, the state of negative nitrogen balance frequently observed during critical illness could be partially attributed to disturbances in the gut microbiome, which impacts the intestinal urea recycling process.

Lipids

The impact of dietary lipids on the microbiota in critically ill patients has not yet been established. However, preclinical studies in animal models indicate that the intestinal microbiota regulates fat metabolism by suppressing the activity of a circulating inhibitor of lipoprotein lipase (LPL).[66] This results in increased levels of circulating LPL, which stimulate hepatic triglyceride production and promote the storage of triglycerides in the adipocyte.[66,67,68] Suppression of LPL inhibitors is promoted by intestinal microbiota through transcriptional suppression of the intestinal epithelial gene encoding for LPL inhibitors.[66] Abnormalities in lipid metabolism commonly observed during critical illness could be also related to the disturbance in the functional capacity of the gut microbiota.

Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs)

SCFAs arising from the anaerobic bacterial metabolism of indigestible dietary fibre in the colon are beneficial to the host health. SCFAs support the integrity of the gut barrier by regulating the release of mucus by colonic cells and acting as a fuel source to colon cells. They also have immune-modulating activity and are involved in the release of gut hormones.[69,70] The principal SCFAs seen in the colon are acetate, propionate and butyrate. SCFAs are depleted in adults with a critical illness, often due to the effect of the acute insult and other environmental factors on SCFAs-forming species.[16,17,18,19,71,72]

SCFAs as a source of energy

The bacterial formation of SCFAs enables the host to salvage some of the energy contained in dietary fibre that would otherwise be lost, while various tissues in the body can oxidise SCFAs for energy generation.[58] SCFAs are absorbed by passive diffusion across the colonic epithelium and utilised by different organs. Colonic epithelial cells derive up to 70% of their energy from the oxidation of butyrate.[50] Propionate serves as a substrate for microbial gluconeogenesis.[59,60] Acetate is used by skeletal and cardiac muscle and can also be utilised by adipocytes for lipogenesis.[73] Butyrate is metabolised primarily in the gut epithelium to yield ketone bodies or CO2 and propionate is transported to the liver for gluconeogenesis.[10]

Physiological functions of SCFAs

Besides being used as fuel by different organs, SCFAs have other physiological functions.[74,75] For instance, butyrate appears to affect cell differentiation and protects cells from carcinogens, either by slowing growth and activating apoptosis in colon cancer cells,[76] or by upregulating the detoxifying enzymes, such as glutathione-S-transferases.[77] SCFAs also impact water absorption, local blood flow and epithelial proliferation in the large intestines.[10] SCFAs have a direct protective effect on strengthening the gut barrier in the normal colon by increasing the production of mucus by colonocytes.[78] Most importantly, SCFAs are involved in the regulation of inflammation. Generally, SCFAs exert their physiological functions by acting as signal molecules that activate target receptors in various cells and organs.

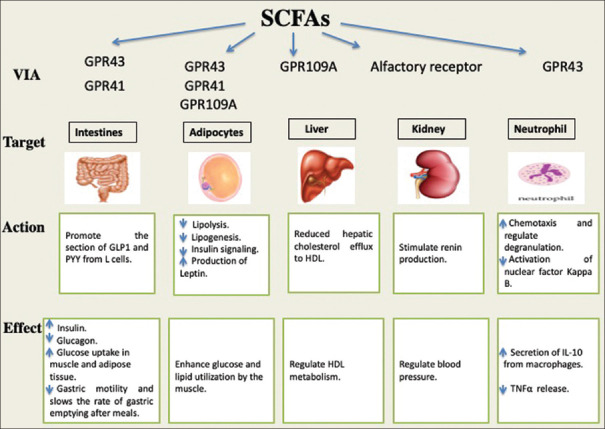

SCFAs as signalling molecules

The physiological effects of SCFAs depend on the activation of G protein-coupled receptors (GPRs).[69,79] In adipocytes, the activation of GPR43 by SCFAs results in the suppression of insulin signalling and accordingly inhibits lipogenesis and enhances glucose and lipid utilisation by the muscles. On the other hand, activated GPR41 enhances the production of leptin and activated GPR109A suppresses lipolysis.[79,80] Besides, it has been suggested that the SCFAs activation of GPR41 in adipocytes increases fatty acid oxidation and energy expenditure.[50] The expression of GPR41 and GPR43 by SCFA in the intestines promotes gut hormone secretion, which regulates energy homeostasis[61,62] [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

SCFAs as signalling molecules activating G-protein-coupled receptors. A summary of the physiological function that SCFAs exert by activating G-protein-coupled receptors in different target organs and cells. *GPR (G protein-coupled receptors)

SCFAs and inflammation

An important driver of MOF in critical illness is the dysregulation of innate immune pathways and the loss of balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mechanisms.[81] SCFAs appear to play a role in modulating inflammatory and immune responses, since they modify the migration of leukocytes to the site of inflammation, as well as modifying the release and production of chemokine.[69] The activation of GPR43 by SCFAs induces chemotaxis and regulates the degranulation of neutrophils.[79] The anti-inflammatory properties of SCFAs have been investigated in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). In a previous study in patients with IBD, impaired butyrate metabolism was reported.[82] SCFAs, in particular butyrate, reduce inflammatory cytokine production and inflammation in the intestine through mechanisms including nuclear factor kappa B signalling.[57,83] SCFAs exert an inhibitory effect on both tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)-mediated activation of the nuclear factor kappa B pathway and lipopolysaccharide-induced TNF-α release.[83] On the other hand, they increase the secretion of anti-inflammatory interleukin-10 (IL-10) from macrophages.[79]

Regulation of bile acid metabolism

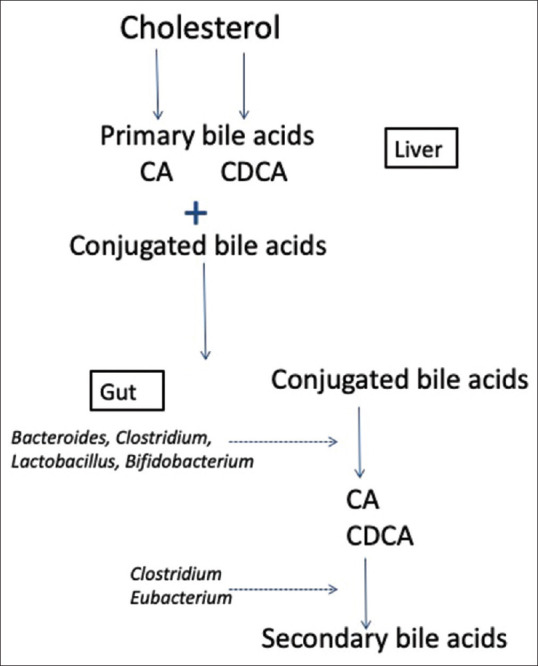

Bile acids (BAs) are synthesised in the liver from cholesterol and stored in the gall bladder. They are released into the small intestines following food ingestion to aid the digestion process by facilitating the emulsification of dietary fats. The physiological functions of BAs in the human body are not only restricted to facilitating lipid digestion and absorption, they appear to be also involved in the overall regulation of host metabolism.[84] Recently, preclinical studies in murine and in vitro models indicated that BAs contribute to the activation of the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and the GPR5 receptor. These receptors activate the expression of genes involved in BAs, lipids and carbohydrates metabolism as well as energy expenditure regulation.[85,86,87]

The human BA pool is made up of primary, secondary and tertiary BAs. The primary BAs (cholic acid [CA] and chenodeoxycholic acid [CDCA]) are synthesised in the liver, while secondary BAs are produced in the gut via the modification of primary BAs through dehydroxylation, epimerisation and oxidation. The tertiary BAs are formed in both the liver and gut microbiota via modification of secondary BAs through sulfation, glucuronidation, glucosidation and N-acetylglucosaminidation.[88,89,90]

Primary BAs synthesised by the liver are conjugated with taurine or glycine and during enterohepatic circulation they are then deconjugated through gut microbial action.[89] The resulting free amino acids are then metabolised by intestinal microbiota (e.g., Bifidobacterium) for energy supply.[91]

The intestinal microbiota possesses enzymes involved in the regulation of the BA pool such as bacterial bile salt hydrolases, bacterial hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases and 7α/β-dehydroxylase.[89] The majority of intestinal microbial species facilitate deconjugation and dehydrogenation of bile salts through the expression of bacterial bile salt hydrolases and bacterial hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases. Limited intestinal species (e.g., Clostridium clusters XI and XVIa, such as C. sordellii, C. sordelliifell and C. scindens) express 7α/β-dehydroxylase enzymes that catalyse the dehydrogenation reaction of primary BAs[89,92] [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Regulation of bile acid metabolism by intestinal microbiota illustrating the contribution of Bacteriodes, Clostridium, Lactobacillus, Bifidobacteria and Eubacterium to the regulation of bile acid metabolism. *CA (Cholic Acid). *CDCA (Chenodeoxycholic Acid)

TARGETED MODULATION OF INTESTINAL MICROBIOME TO IMPROVE CLINICAL OUTCOMES IN CRITICALLY ILL PATIENTS

Given the substantial clinical and experimental evidence supporting the gut-lymph hypothesis,[22,93] the targeted modulation of the intestinal microbiome has been proposed as a therapy to support gut health in critically ill patients.

The suppression of pathogenic gut bacteria was the first therapeutic line of microbiome modulation tried on critically ill patients. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD) was first introduced in the 1980s,[94] aimed at keeping the overgrowth of potential pathogens in the gut to the minimum through the administration of tailored antibiotic treatment.[27,94] Ever since, SDD intervention has been tested in many clinical trials in critically ill patients.[95,96,97] Although proven effective and shown to significantly reduce the rate of infections, the number of patients with MOF and mortality,[95,96,98] there remains concern about the potential risk of antimicrobial resistance.[99,100] All these data are derived from studies on critically ill adults, and paediatric-specific clinical trials are absent. In a recent survey by Murthy et al. (2017) to determine the baseline knowledge of healthcare providers about SDD, they indicated that there is still uncertainty about implementing SDD protocols in paediatric ICUs, mainly due to concerns about antimicrobial resistance.[101]

Given the extensive vascular and lymphatic links between the intestine and other organs, it is possible that enhancing the growth of commensal bacteria and their metabolites by EN could be of systemic clinical benefit. Certain nutrients have been verified for their capacity to modulate the gut bacterial profile, such as glutamine and prebiotics (the dietary fibre that promotes the growth of beneficial bacteria). In a previous study to evaluate the effect of glutamine supplementation on gut microbial content, they reported significant changes in the composition of the gut microbiota in obese subjects.[102] As regards to prebiotics, lactulose added to infant formulas were used long enough to increase the numbers of lactobacilli in infant's intestines.[103] However, this practice has evolved with extensive research on the role of prebiotics in enteral feeds. The most common prebiotics are fructooligosaccharides and galactooligosaccharides; they have been added to several infant formulas and they demonstrated modulation of the gut bacterial population.[104,105] The use of probiotics containing Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria species has a beneficial effect on modulating the balance of the intestinal microbiota.[103] Furthermore, using probiotics in combination with antibiotic therapy has proven to have a beneficial effect, as probiotics not only suppress gastrointestinal pathogens but may potentiate the efficacy of antibiotics by producing antibacterial factors.[33] Generally, using probiotics in clinical settings has been proven to be safe, however, they must be used with caution in certain patient groups.[106] A theoretical concern with the safety of using probiotics is that some of them may adhere to the intestinal mucosa and facilitate bacterial translocation and virulence.[107] However, Srinivasan et al. (2006) showed that the supplementation of probiotics in enterally fed critically ill children is safe and is not associated with any clinical complications.[106] In a recent study of critically ill adult patients, the administration of synbiotics, a combination of probiotics and prebiotics, was associated with a reduction in the rate of infections and an increase in the count of commensal bacteria, as well as SCFAs.[108] This suggests that nutritional intervention targeting the gut microbiota in critically ill patients has the potential to improve clinical outcomes.

CONCLUSION

It is crucial to understand the pathophysiological basis of the acute insult to develop new novel therapies that improve clinical outcomes of critically ill patients. It became clear that gut failure might play a role in the progression of systemic inflammation during critical illness. Therefore, the microbiome should be considered as an organ that can fail in critically ill patients and can impact other organs. Critically ill patients may be stuck in a vicious cycle of systemic inflammation and dysbiosis of the gut microbiome. Nutritional intervention could be a potential therapy to alleviate the disease state and improve clinical outcomes in this population by breaking this cycle and restoring the homeostatic state of the intestinal microbiome.

Although, nutrition is considered an integral part of the treatment plan of critically ill patients, what is missed is whether the nutrients provided are adequate and how they are processed and utilised by the host and the microbiota. The goal of nutrition therapy in critical illness should not only be limited to improve nitrogen balance, it should also be about providing good quality feeds with balance macronutrient content to feed up the entire body including the microbiota and host cells. Nutritional interventions may help to maintain the commensal population and restore normal gut host relationships. Yet no clinical trials in critically ill patients have tried targeted gut modulation by nutritional intervention. Future work should aim at personalising the care of the critically ill population and suggest ways to manipulate the body's response to severe illness to restore the homeostatic state.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Nazima Pathan, a university lecturer and PICU consultant at the University of Cambridge, for her valuable input and continueous guidance throughout the process of writing this review.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parekh PJ, Arusi E, Vinik AI, Johnson DA. The role and influence of gut microbiota in pathogenesis and management of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014;5:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly TN, Bazzano LA, Ajami NJ, He H, Zhao J, Petrosino JF, et al. Gut microbiome associates with lifetime cardiovascular disease risk profile among Bogalusa heart study participants. Circ Res. 2016;119:956–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noval Rivas M, Crother TR, Arditi M. The microbiome in Asthma. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28:764–71. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wijeyesekera A, Wagner J, De Goffau M, Thurston S, Sabino AR, Zaher S, et al. Multi-compartment profiling of bacterial and host metabolites identifies intestinal dysbiosis and its functional consequences in the critically ill child. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:e727–e734. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krezalek MA, Yeh A, Alverdy JC, Morowitz M. Influence of nutrition therapy on the intestinal microbiome. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2017;20:131–7. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrer M, Méndez-García C, Rojo D, Barbas C, Moya A. Antibiotic use and microbiome function. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017;134:114–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maier L, Pruteanu M, Kuhn M, Zeller G, Telzerow A, Anderson EE, et al. Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature. 2018;555:623–8. doi: 10.1038/nature25979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lupp C, Robertson ML, Wickham ME, Sekirov I, Champion OL, Gaynor EC, et al. Host-mediated inflammation disrupts the intestinal microbiota and promotes the overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:119–29. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kohler JE, Zaborina O, Wu L, Wang Y, Bethel C, Chen Y, et al. Components of intestinal epithelial hypoxia activate the virulence circuitry of Pseudomonas. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G1048–54. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00241.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morowitz MJ, Carlisle EM, Alverdy JC. Contributions of intestinal bacteria to nutrition and metabolism in the critically ill. Surg Clin North Am. 2011;91:771–85. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lara TM, Jacobs DO. Effect of critical illness and nutritional support on mucosalmass and function. Clin Nutr. 2016;17:99–105. doi: 10.1016/s0261-5614(98)80002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Btaiche IF, Chan L-N, Pleva M, Kraft MD. Critical illness, gastrointestinal complications, and medication therapy during enteral feeding in critically ill adult patients. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010;25:32–49. doi: 10.1177/0884533609357565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs MC, Haak BW, Hugenholtz F, Wiersinga WJ. Gut microbiota and host defense in critical illness. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2017;23:257–63. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers MB, Firek B, Shi M, Yeh A, Brower-Sinning R, Aveson V, et al. Disruption of the microbiota across multiple body sites in critically ill children. Microbiome. 2016;4:66. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0211-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ojima M, Motooka D, Shimizu K, Gotoh K, Shintani A, Yoshiya K, et al. Metagenomic analysis reveals dynamic changes of whole gut microbiota in the acute phase of intensive care unit patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:1628–34. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-4011-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimizu K, Ogura H, Goto M, Asahara T, Nomoto K, Morotomi M, et al. Altered gut flora and environment in patients with severe SIRS. J Trauma. 2006;60:126–33. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000197374.99755.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iapichino G, Callegari ML, Marzorati S, Cigada M, Corbella D, Ferrari S, et al. Impact of antibiotics on the gut microbiota of critically ill patients. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:1007–14. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47387-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayakawa M, Asahara T, Henzan N, Murakami H, Yamamoto H, Mukai N, et al. Dramatic changes of the gut flora immediately after severe and sudden insults. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2361–5. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1649-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada T, Shimizu K, Ogura H, Asahara T, Nomoto K, Yamakawa K, et al. Rapid and sustained long-term decrease of fecal short-chain fatty acids in critically ill patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2015;39:569–7. doi: 10.1177/0148607114529596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark JA, Coopersmith CM. Intestinal crosstalk: A new paradigm for understanding the gut as the “motor” of critical illness. Shock. 2007;28:384–93. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e31805569df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pathan N, Burmester M, Adamovic T, Berk M, Ng KW, Betts H, et al. Intestinal injury and endotoxemia in children undergoing surgery for congenital heart disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1261–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0715OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deitch EA. Gut-origin sepsis: Evolution of a concept. Surgeon. 2012;10:350–6. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reintam A, Parm P, Kitus R, Kern H, Starkopf J. Gastrointestinal symptoms in intensive care patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:318–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mittal R, Coopersmith CM. Redefining the gut as the motor of critical illness. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20:214–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaher S, Branco R, Meyer R, White D, Ridout J, Pathan N. Relationship between inflammation and metabolic regulation of energy expenditure by GLP-1 in critically ill children. Clin Nutr. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.06.013. S0261-5614(20)30324-1. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.06.013. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Salhy M, Solomon T, Hausken T, Gilja OH, Hatlebakk JG. Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine peptides/amines in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:5068–85. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i28.5068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dickson RP. The microbiome and critical illness. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:59–72. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00427-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alverdy J, Holbrook C, Rocha F, Seiden L, Wu RL, Musch M, et al. Gut-derived sepsis occurs when the right pathogen with the right virulence genes meets the right host: Evidence for in vivo virulence expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Ann Surg. 2000;232:480–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200010000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandrini S, Aldriwesh M, Alruways M, Freestone P. Microbial endocrinology: Host-bacteria communication within the gut microbiome. J Endocrinol. 2015;225:R21–34. doi: 10.1530/JOE-14-0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freestone PPE, Haigh RD, Lyte M. Catecholamine inotrope resuscitation of antibiotic-damaged staphylococci and its blockade by specific receptor antagonists. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1044–52. doi: 10.1086/529202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malacarne P, Rossi C, Bertolini G. Antibiotic usage in intensive care units: A pharmaco-epidemiological multicentre study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:221–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmer C, Bik EM, DiGiulio DB, Relman DA, Brown PO. Development of the human infant intestinal microbiota. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Preidis GA, Versalovic J. Targeting the human microbiome with antibiotics, probiotics, and prebiotics: Gastroenterology enters the metagenomics era. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2015–31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Theriot CM, Koenigsknecht MJ, Carlson PE, Jr, Hatton GE, Nelson AM, Li B, et al. Antibiotic-induced shifts in the mouse gut microbiome and metabolome increase susceptibility to Clostridium difficile infection. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3114. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Panda S, El khader I, Casellas F, Vivancos JL, Cors MG, Santiago A, et al. Short-term effect of antibiotics on human gut microbiota. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Theriot, Casey M, Alison A, Bowman, Vincent B. Alison A Bowman, and Vincent B Young “Antibiotic-induced alterations of the gut microbiota alter secondary bile acid production and allow for Clostridium difficile spore germination and outgrowth in the large intestine”. MSphere 1.1. 2016:e00045–15. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00045-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schumann A, Nutten S, Donnicola D, Comelli EM, Mansourian R, Cherbut C, et al. Neonatal antibiotic treatment alters gastrointestinal tract developmental gene expression and intestinal barrier transcriptome. Physiol Genomics. 2005;23:235–45. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00057.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weber DJ, Raasch R, Rutala WA. Nosocomial infections in the ICU: The growing importance of antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Chest. 1999;115(3 Suppl):34S–41S. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.suppl_1.34s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hodin CM, Visschers RGJ, Rensen SS, Boonen B, Olde Damink SWM, Lenaerts K, et al. Total parenteral nutrition induces a shift in the Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio in association with Paneth cell activation in rats. J Nutr. 2012;142:2141–7. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.162388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiga H, Kajiura T, Shinozaki J, Takagi S, Kinouchi Y, Takahashi S, et al. Changes of faecal microbiota in patients with Crohn's disease treated with an elemental diet and total parenteral nutrition. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:736–42. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH. Enteral nutrition in the critically ill patient: A critical review of the evidence. Intensive Care Med. 1993;19:435–42. doi: 10.1007/BF01711083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang H, Feng Y, Sun X, Teitelbaum DH. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition: Effect on intestinal barrier function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1165:338–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feng P, He C, Liao G, Chen Y. Early enteral nutrition versus delayed enteral nutrition in acute pancreatitis: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e8648. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kotani J, Usami M, Nomura H, Iso A, Kasahara H, Kuroda Y, et al. Enteral nutrition prevents bacterial translocation but does not improve survival during acute pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 1999;134:287–92. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deplancke B, Vidal O, Ganessunker D, Donovan SM, Mackie RI, Gaskins HR. Selective growth of mucolytic bacteria including Clostridium perfringens in a neonatal piglet model of total parenteral nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:1117–25. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.5.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bjornvad CR, Thymann T, Deutz NE, Burrin DG, Jensen SK, Jensen BB, et al. Enteral feeding induces diet-dependent mucosal dysfunction, bacterial proliferation, and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm pigs on parenteral nutrition. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G1092–103. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00414.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang M, Yang X-J. Effects of a high fat diet on intestinal microbiota and gastrointestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8905–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i40.8905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown K, DeCoffe D, Molcan E, Gibson DL. Diet-induced dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota and the effects on immunity and disease. Nutrients. 2012;4:1095–119. doi: 10.3390/nu4081095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Graf D, Cagno R Di, Fåk F, Flint HJ, Nyman M, Saarela M, et al. Contribution of diet to the composition of the human gut microbiota. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015;26:26164. doi: 10.3402/mehd.v26.26164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud DJ, Bakker BM. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:2325–40. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R036012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bouhnik Y, Flourié B, Riottot M, Bisetti N, Gailing MF, Guibert A, et al. Effects of fructo-oligosaccharides ingestion on fecal bifidobacteria and selected metabolic indexes of colon carcinogenesis in healthy humans. Nutr Cancer. 1996;26:21–9. doi: 10.1080/01635589609514459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vulevic J, Drakoularakou A, Yaqoob P, Tzortzis G, Gibson GR. Modulation of the fecal microflora profile and immune function by a novel trans-galactooligosaccharide mixture (B-GOS) in healthy elderly volunteers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1438–46. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramirez-Farias C, Slezak K, Fuller Z, Duncan A, Holtrop G, Louis P. Effect of inulin on the human gut microbiota: Stimulation of Bifidobacterium adolescentis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. Br J Nutr. 2009;101:533. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508019880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benus RFJ, van der Werf TS, Welling GW, Judd PA, Taylor MA, Harmsen HJM, et al. Association between Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and dietary fibre in colonic fermentation in healthy human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:693–700. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510001030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sawicki CM, Livingston KA, Obin M, Roberts SB, Chung M, McKeown NM. Dietary fiber and the human gut microbiota: Application of evidence mapping methodology. Nutrients. 2017;9:125. doi: 10.3390/nu9020125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krajmalnik-Brown R, Ilhan Z-E, Kang D-W, DiBaise JK. Effects of gut microbes on nutrient absorption and energy regulation. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012;27:201–14. doi: 10.1177/0884533611436116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramakrishna BS. Role of the gut microbiota in human nutrition and metabolism. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(Suppl 4):9–17. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blaut M, Clavel T. Metabolic diversity of the intestinal microbiota: Implications for health and disease. J Nutr. 2007;137(3 Suppl 2):751S–5S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.3.751S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Goncalves D, Vinera J, Zitoun C, Duchampt A, et al. Microbiota-generated metabolites promote metabolic benefits via gut-brain neural circuits. Cell. 2014;156:84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rowland I, Gibson G, Heinken A, Scott K, Swann J, Thiele I, et al. Gut microbiota functions: Metabolism of nutrients and other food components. Eur J Nutr. 2018;57:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s00394-017-1445-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Psichas A, Sleeth ML, Murphy KG, Brooks L, Bewick GA, Hanyaloglu AC, et al. The short chain fatty acid propionate stimulates GLP-1 and PYY secretion via free fatty acid receptor 2 in rodents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015;39:424–9. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tolhurst G, Heffron H, Lam YS, Parker HE, Habib AM, Diakogiannaki E, et al. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion via the G-protein-coupled receptor FFAR2. Diabetes. 2012;61:364–71. doi: 10.2337/db11-1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Metges CC. Contribution of microbial amino acids to amino acid homeostasis of the host. J Nutr. 2000;130:1857S–64S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.7.1857S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levenson S, Crowley L. The metabolism of carbon-labeled urea in the germfree rat. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:2061–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Walser M, Bodenlos LJ. Urea metabolism in man. J Clin Invest. 1959;38:1617–26. doi: 10.1172/JCI103940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bäckhed F, Ding H, Wang T, Hooper LV, Koh GY, Nagy A, et al. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15718–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407076101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Janssen AWF, Kersten S. Potential mediators linking gut bacteria to metabolic health: A critical view. J Physiol. 2017;595:477–87. doi: 10.1113/JP272476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goldberg IJ, Eckel RH, Abumrad NA. Regulation of fatty acid uptake into tissues: Lipoprotein lipase- and CD36-mediated pathways. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S86–90. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800085-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vinolo MAR, Rodrigues HG, Nachbar RT, Curi R. Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients. 2011;3:858–76. doi: 10.3390/nu3100858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Byrne CS, Chambers ES, Morrison DJ, Frost G. The role of short chain fatty acids in appetite regulation and energy homeostasis. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015;39:1331–8. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Osuka A, Shimizu K, Ogura H, Tasaki O, Hamasaki T, Asahara T, et al. Prognostic impact of fecal pH in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2012;16:R119. doi: 10.1186/cc11413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vermeiren J, Van den Abbeele P, Laukens D, Vigsnaes LK, De Vos M, Boon N, et al. Decreased colonization of fecal clostridium coccoides/eubacterium rectale species from ulcerative colitis patients in an in vitro dynamic gut model with mucin environment. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012;79:685–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hooper LV, Midtvedt T, Gordon JI. How host-microbial interactions shape the nutrient environment of the mammalian intestine. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002;22:283–307. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.011602.092259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Topping DL, Clifton PM. Short-chain fatty acids and human colonic function: Roles of resistant starch and nonstarch polysaccharides. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1031–64. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kasubuchi M, Hasegawa S, Hiramatsu T, Ichimura A, Kimura I. Dietary gut microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, and host metabolic regulation. Nutrients. 2015;7:2839–49. doi: 10.3390/nu7042839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Scharlau D, Borowicki A, Habermann N, Hofmann T, Klenow S, Miene C, et al. Mechanisms of primary cancer prevention by butyrate and other products formed during gut flora-mediated fermentation of dietary fibre. Mutat Res. 2009;682:39–53. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pool-Zobel B, Veeriah S, Böhmer F-D. Modulation of xenobiotic metabolising enzymes by anticarcinogens -- focus on glutathione S-transferases and their role as targets of dietary chemoprevention in colorectal carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 2005;591:74–92. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lewis K, Lutgendorff F, Phan V, Söderholm JD, Sherman PM, McKay DM. Enhanced translocation of bacteria across metabolically stressed epithelia is reduced by butyrate. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1138–48. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kim CH, Park J, Kim M. Gut microbiota-derived short-chain Fatty acids, T cells, and inflammation. Immune Netw. 2014;14:277–88. doi: 10.4110/in.2014.14.6.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kimura I, Inoue D, Hirano K, Tsujimoto G. The SCFA receptor GPR43 and energy metabolism. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014;5:85. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cox CE. Persistent systemic inflammation in chronic critical illness. Respir Care. 2012;57:859–66. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Canani RB, Costanzo MD, Leone L, Pedata M, Meli R, Calignano A. Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1519–28. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tedelind S, Westberg F, Kjerrulf M, Vidal A. Anti-inflammatory properties of the short-chain fatty acids acetate and propionate: A study with relevance to inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2826–32. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i20.2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ramírez-Pérez O, Cruz-Ramón V, Chinchilla-López P, Méndez-Sánchez N. The role of the gut microbiota in bile acid metabolism. Medica Sur Clin Found. 2017;16:2017. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.5494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cariou B, van Harmelen K, Duran-Sandoval D, van Dijk TH, Grefhorst A, Abdelkarim M, et al. The farnesoid X receptor modulates adiposity and peripheral insulin sensitivity in mice. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11039–49. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510258200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Abdelkarim M, Caron S, Duhem C, Prawitt J, Dumont J, Lucas A, et al. The farnesoid X receptor regulates adipocyte differentiation and function by promoting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma and interfering with the Wnt/beta-catenin pathways. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:36759–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.166231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Watanabe M, Houten SM, Mataki C, Christoffolete MA, Kim BW, Sato H, et al. Bile acids induce energy expenditure by promoting intracellular thyroid hormone activation. Nature. 2006;439:484–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Marschall HU, Matern H, Wietholtz H, Egestad B, Matern S, Sjövall J. Bile acid N-acetylglucosaminidation. In vivo and in vitro evidence for a selective conjugation reaction of 7 beta-hydroxylated bile acids in humans. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1981–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI115806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ridlon JM, Kang D-J, Hylemon PB. Bile salt biotransformations by human intestinal bacteria. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:241–59. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R500013-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wahlströ A, Sayin SI, Marschall H-U, Bä Ckhed F. Cell metabolism review intestinal crosstalk between bile acids and microbiota and its impact on host metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016;24:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tanaka H, Hashiba H, Kok J, Mierau I. Bile salt hydrolase of bifidobacterium longum-biochemical and genetic characterization. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2502–12. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.6.2502-2512.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nie Y, Hu J, Yan X. Cross-talk between bile acids and intestinal microbiota in host metabolism and health. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2015;16:436–46. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1400327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Deitch EA, Xu D-Z, Lu Q. Gut lymph hypothesis of early shock and trauma-induced multiple organ dysfunction syndrome: A new look at gut origin sepsis. J Organ Dysfunct. 2006;2:70–9. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Unertl K, Ruckdeschel G, Selbmann HK, Jensen U, Forst H, Lenhart FP, et al. Prevention of colonization and respiratory infections in long-term ventilated patients by local antimicrobial prophylaxis. Intensive Care Med. 1987;13:106–13. doi: 10.1007/BF00254795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.de Jonge E, Schultz MJ, Spanjaard L, Bossuyt PMM, Vroom MB, Dankert J, et al. Effects of selective decontamination of digestive tract on mortality and acquisition of resistant bacteria in intensive care: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362:1011–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14409-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.de Smet AMGA, Kluytmans JAJW, Cooper BS, Mascini EM, Benus RFJ, van der Werf TS, et al. Decontamination of the digestive tract and oropharynx in ICU patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:20–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Daneman N, Sarwar S, Fowler RA, Cuthbertson BH, SuDDICU Canadian Study Group. Effect of selective decontamination on antimicrobial resistance in intensive care units: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:328–41. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Silvestri L, de la Cal MA, van Saene HKF. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract: The mechanism of action is control of gut overgrowth. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1738–50. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2690-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Francis JJ, Duncan EM, Prior ME, Maclennan GS, Dombrowski S, Bellingan GU, et al. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract in critically ill patients treated in intensive care units: A mixed-methods feasibility study (the SuDDICU study) Health Technol Assess. 2014;18:1–170. doi: 10.3310/hta18250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cavalcanti AB, Lisboa T, Gales AC. Is selective digestive decontamination useful for critically ill patients? SHOCK. 2017;47(1S Suppl 1):52–7. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Murthy S, Pathan N, Cuthbertson BH. Selective digestive decontamination in critically ill children: A survey of Canadian providers. J Crit Care. 2017;39:169–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.de Souza AZZ, Zambom AZ, Abboud KY, Reis SK, Tannihão F, Guadagnini D, et al. Oral supplementation with L-glutamine alters gut microbiota of obese and overweight adults: A pilot study. Nutrition. 2015;31:884–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Collins MD, Gibson GR. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics: Approaches for modulating the microbial ecology of the gut. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:1052S–7S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.5.1052s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vandenplas Y, De Greef E, Veereman G. Prebiotics in infant formula. Gut Microbes. 2014;5:681–7. doi: 10.4161/19490976.2014.972237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fanaro S, Boehm G, Garssen J, Knol J, Mosca F, Stahl B, et al. Galacto-oligosaccharides and long-chain fructo-oligosaccharides as prebiotics in infant formulas: A review. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:22–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb02150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Srinivasan R, Meyer R, Padmanabhan R, Britto J. Clinical safety of lactobacillus casei shirota as a probiotic in critically ill children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:171–3. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000189335.62397.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Boyle RJ, Robins-Browne RM, Tang ML. Probiotic use in clinical practice: What are the risks? Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1256–64. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shimizu K, Yamada T, Ogura H, Mohri T, Kiguchi T, Fujimi S, et al. Synbiotics modulate gut microbiota and reduce enteritis and ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients with sepsis: A randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2018;22:239. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2167-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]