Abstract

Background:

Having a penicillin allergy label associates with a higher risk for antibiotic resistance and increased health care use.

Objective:

We sought to assess the accuracy of skin tests and specific IgE quantification in the diagnostic evaluation of patients reporting a penicillin/β-lactam allergy.

Methods:

We performed a systematic review and diagnostic accuracy meta-analysis, searching on MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science. We included studies conducted in patients reporting a penicillin allergy and in whom skin tests and/or specific IgE quantification were performed and compared with drug challenge results. We quantitatively assessed the accuracy of diagnostic tests with bivariate random-effects meta-analyses. Meta-regression and subgroup analyses were performed to explore causes of heterogeneity. Studies’ quality was evaluated using QUADAS-2 criteria.

Results:

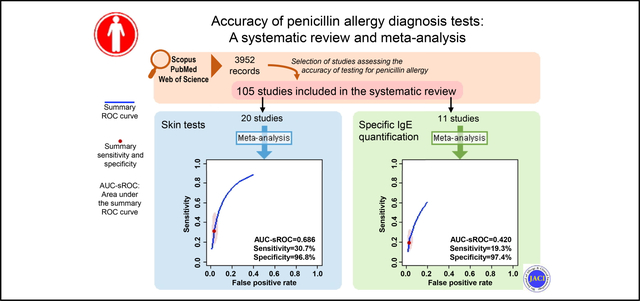

We included 105 primary studies, assessing 31,761 participants. Twenty-seven studies were assessed by bivariate meta-analysis. Skin tests had a summary sensitivity of 30.7% (95% CI, 18.9%−45.9%) and a specificity of 96.8% (95% CI, 94.2%−98.3%), with a partial area under the summary receiver-operating characteristic curve of 0.686 (I2 = 38.2%). Similar results were observed for subanalyses restricted to patients reporting nonimmediate maculopapular exanthema or urticaria/angioedema. Specific IgE had a summary sensitivity of 19.3% (95% CI, 12.0%−29.4%) and a specificity of 97.4% (95% CI, 95.2%−98.6%), with a partial area under the summary receiver-operating characteristic curve of 0.420 (I2 = 8.5%). Projected predictive values mainly reflect the low frequency of true penicillin allergy.

Conclusions:

Skin tests and specific IgE quantification appear to have low sensitivity and high specificity. Because current evidence is insufficient for assessing the role of these tests in stratifying patients for delabeling, we identified key requirements needed for future studies.

Keywords: Diagnostic accuracy, drug provocation test, IgE quantification, penicillin allergy, skin tests

Graphical Abstract

Beta-lactams are a class of broad-spectrum antibiotics that include penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, and monobactams. Because of their high effectiveness, safety, and low costs, β-lactams are the most frequently prescribed antibiotics in the world, and those for which hypersensitivity reactions are most often reported.1,2 Penicillin allergy reporting is particularly frequent—in Europe and North America, allergy to penicillins is reported by up to 10% of the general population and 15% of hospitalized patients.1,3–5 However, several studies have shown that there is an overdiagnosis of penicillin allergy, because only 2% to 10% of individuals who report penicillin allergy are truly allergic.3,6

Without a proper diagnostic approach, many patients with a penicillin allergy label may unnecessarily receive second-line, broad-spectrum antibiotics, leading to an increased risk of drug failure, hospital-acquired infections, and higher length of stay.7–10 These consequences, along with the use of more expensive antibiotics, explain the higher costs of treating patients with a penicillin allergy label,7,8 and why penicillin allergy testing programs have been identified as a vital tool to improve antimicrobial stewardship and curb antibiotic resistance.3,10

Patients reporting a penicillin allergy should have their diagnosis confirmed. The International Consensus on Drug Allergy recommends an approach based on skin tests and, in case of negative results, a confirmatory drug provocation test (DPT; “drug challenge”).11 Two types of skin tests are usually done—(1) skin prick tests, which are the first to be performed, consisting in pricking the skin with small amounts of penicillin reagents, and (2) intradermal tests, which are performed when skin prick test results are negative, involving placing penicillin reagents just underneath the skin.12 In patients reporting immediate reactions, a blood test for quantification of penicillins specific IgE (sIgE) is indicated by European recommendations.13 If negative results are obtained, the patient undergoes a DPT, receiving a penicillin drug under clinical observation.

The DPT is the reference standard for testing patients reporting a penicillin allergy. However, because it is typically performed after negative results with skin tests and/or sIgE quantification, there is still scarce information on the accuracy of these recommended diagnostic tests. In fact, although skin tests appear to have a high negative predictive value (NPV), there are conflicting reports on their sensitivity and positive predictive value (PPV), with wide ranges of values reported. Therefore, this systematic review aimed to evaluate the accuracy of the diagnostic tests—skin tests and sIgE quantification—used in the evaluation of patients reporting a penicillin/β-lactam allergy, and to identify factors that may explain differences in diagnostic parameter estimates.

METHODS

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

This study is a systematic review with meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy, complying with the Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies (PRISMA-DTA) Statement.14

We included original studies conducted in patients in whom penicillin/β-lactam allergy was reported, and in whom the results of DPT had been compared with those of skin tests (skin prick and/or intradermal tests) and/or sIgE quantification (“index tests”). We excluded studies conducted only in patients with nonpenicillin β-lactam allergy, and studies evaluating only patients with specific diseases (eg, patients with rheumatic fever) or occupations (eg, nurses).

Three electronic bibliographic databases (MEDLINE/PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus) were searched in July 2018. The queries (presented in Table E1 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org) included a database adaptation of the strategy presented by Astin et al15 to search for diagnostic performance studies. No restrictions based on primary studies’ language or publication date were applied.

After eliminating duplicates, the titles and abstracts of the obtained studies were independently evaluated by 2 researchers. Subsequently, the full texts of selected studies were independently read by 2 investigators, who extracted information regarding the year of publication, country, sampling method, study setting (outpatients, inpatients, or emergency department), tested drugs/determinants, participants’ number, sex, and age distributions, and inclusion criteria regarding initial reactions—initial reactions were assessed on the basis of involved drug classes (whether studies included participants reporting an allergy to any β-lactam or specifically to penicillins), clinical manifestations, and timing. Immediate reactions were defined as initial reactions occurring within the first hour after contact with the suspected drug, whereas non-immediate reactions were defined as those occurring after the first hour of drug contact. In addition, we collected information related to each diagnostic index test, including the performed tests, number of participants with positive and negative results, and number of participants submitted to DPT. For primary studies assessing patients with any reported β-lactam allergy but presenting discriminated results for those who specifically reported a penicillin allergy, we retrieved data concerning only the latter.

Data were extracted by means of a purposely-built form—we developed a pilot version, which was modified after assessment of the first 10 studies. For publications whose full texts were not available, we contacted corresponding authors. Authors were also contacted to provide relevant missing information. Disagreements in study selection or data extraction were solved by consensus.

Study quality was independently assessed by 2 researchers according to QUADAS-2 judgments on primary studies’ risk of bias and applicability.16

Quantitative synthesis

For each study, we retrieved the frequency of positive results to each index test. On the basis of that and on DPT results, we were able to calculate, for each index test, the number of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and/or false negatives.

For tests for which we had more than 4 primary studies simultaneously presenting results for true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, we performed meta-analyses of diagnostic test accuracy using a bivariate random-effects approach.17 Bivariate random-effects meta-analyses allow for the calculation of summary properties of diagnostic tests (namely, sensitivity, specificity, and area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve), by pooling the results of different diagnostic accuracy studies, accommodating between-study heterogeneity. This method (which is equivalent to the hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic [sROC] model) has the advantage of jointly estimating sensitivity and specificity, accounting for correlation between them.18 Performing bivariate meta-analysis, we calculated areas under the sROC curve (AUC-sROC), and summary sensitivities, specificities, likelihood ratios, and diagnostic odds ratios. A correlation coefficient (r) of more than 0.6 between sensitivity and false-positive rate was considered to represent considerable threshold effect (ie, negative correlation between sensitivity and specificity possibility accounted by variability in positivity criteria).19 Heterogeneity (ie, between-studies variability beyond expected because of chance or random sampling errors alone) was assessed using an I2 statistic estimate for bivariate meta-analysis.20 An I2 value of more than 50% was considered to represent substantial heterogeneity.

On the basis of obtained estimates of pooled sensitivity and specificity, and considering a prevalence of true penicillin allergy ranging from 0% to 10%, we estimated the PPV and NPV of index tests. We performed univariate sensitivity analyses, to obtain PPV and NPV estimates for different prevalence values. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses based on Monte-Carlo simulations were additionally performed to account for uncertainty in pooled sensitivity and specificity estimates.

Whenever there were sufficient primary studies, sensitivity analyses were performed to address the possibility of selection bias and/or to account for possible clinically relevant sources of heterogeneity. Such sensitivity analyses were restricted to (1) studies in which at least 50% of both patients with positive and negative results on index tests received a DPT, (2) studies assessing a mix of participants with immediate and nonimmediate reactions (excluding only those with very severe index reactions), and testing all with index tests and DPT, (3) studies assessing consecutive samples of patients specifically reporting a history of penicillin allergy and—in the case of skin tests—testing for the determinants recommended by the European Network of Drug Allergy (penicillin polylysine, minor determinant mixture, benzylpenicillin, and an aminopenicillin), and (4) studies assessing particular clinical presentations or age groups. In addition, we performed bivariate meta-regression and applied the likelihood-ratio test to identify moderator variables (ie, variables explaining heterogeneity21). Meta-regression tested the following covariates: year of publication, proportion of female subjects, participants’ age group (children, adults, or adults and children), study region (Europe, North America, Middle East, or Australia and Far East), setting, sampling method (consecutive sample including all participants with reported allergy, consecutive sample including all tested participants, or convenience sample), number of tested drugs/determinants (and whether the index test assessed at least an aminopenicillin, a cephalosporin, and/or the suspected drug), reported allergy (to overall β-lactams, penicillins, or aminopenicillins only), and timing of the initial reaction.

Not all studies allowed for obtaining, for each index test, the number of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and/or false negatives. Therefore, in addition to bivariate random-effects meta-analysis, we performed random-effects meta-analysis of individual diagnostic parameter estimates (methods fully described in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). The latter corresponds to a less robust approach in the context of meta-analysis of diagnostic studies, because it does not account for sensitivity-specificity correlation.17

Meta-analyses were performed using software R (version 3.5.0), using mada, meta for, and glmulti packages. Simulations of predictive value estimates were obtained using TreeAge Pro software (TreeAge Software, Inc, Williamstown, Mass). Significance level was defined at P <.05.

RESULTS

Our search yielded 3952 publications, of which 1387 were duplicates; 2419 studies were excluded on the basis of application of eligibility criteria (Fig 1). We could not obtain the full text of 24 publications despite contacting corresponding authors—12 of these studies had been written in languages other than English and 16 had been published before 2000. Of the 122 articles meeting the eligibility criteria, 17 were excluded because some participants had also been assessed (receiving the same tests) by studies assessing larger samples. Therefore, a total of 105 studies were included in this systematic review.13,22–125 For studies in which some degree of participant overlap with other study(ies) occurred (see Table E2 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org),36,37,40–42,59,62,69,72,83,106,109 we presented only unique information from each study (eg, results from diagnostic tests performed in 1 study that had not been performed in the other study assessing the same participants), so that no participant has been included more than once.

FIG 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram illustrating study selection process.

Of the 105 included primary studies, 27 were included in bivariate random-effects meta-analyses22–48 (summary of information in Table I and Table E3 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). The remainder were only quantitatively assessed by means of individual diagnostic parameter estimates meta-analysis, whose description and results can be consulted in this article’s Online Repository (see Tables E2–E4 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). We developed an interactive app (https://penaccuracy.med.up.pt; see this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org), which also presents results from all analyses, as well as results for other tests whose studies were retrieved by our query.

TABLE I.

Description of studies included in the systematic review and assessed by means of bivariate random-effects meta-analyses

| Reference | Country | No. of participants (% females) | Participants’ age group | Setting | Sampling method | Performed tests* | Drugs participants reported to be allergic | Timing of reactions | Index reactions of included participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levine and Zolov,22 1969 | USA | 218† | Children and adults | Patients (not specified) | Consecutive sample ‡ | Skin tests (SPT; IDT§) | Penicillins | Immediate and nonimmediate | MPE; U/A; others unspecified |

| Warrington et al,23 1978 | Canada | 253† | Children and adults | Inpatients and outpatients | Convenience sample | Skin tests (SPT; IDT§) | Penicillins | Immediate and nonimmediate | MPE; U/A; others (including anaphylaxis and arthralgias/ arthritis) |

| Blanca et al,24 1990 | Spain | 288† | Children and adults | Outpatients | Convenience sample | Skin tests (IDT); sIgE | Penicillins | Immediate and nonimmediate | || |

| Sogn et al,251992 | USA | 825† | Adults | Inpatients | Consecutive sample ‡ | Skin tests (SPT; IDT§) | Penicillins | Immediate and nonimmediate | || |

| Romano et al,26 1995 | Italy | 60† | Children and adults | Patients (not specified) | Consecutive sample ¶ | Skin tests (SPT; IDT); sIgE | Aminopenicillins | Nonimmediate | MPE |

| Sastre et al,27 1996 | Spain | 576† | Children and adults | Outpatients | Consecutive sample ¶ | Skin tests (SPT; IDT§) | Penicillins | Immediate | || |

| Cederbrant et al,28 1998 | Sweden | 17 (82) | Adults | Outpatients | Convenience sample | Skin tests (SPT; IDT); sIgE | Penicillins | Immediate and nonimmediate | MPE; U/A; others (including GI reactions and pruritus) |

| Loza Cortina,29 1998 | Spain | 76† | Children | Outpatients | Convenience sample | Skin tests (SPT; IDT§); sIgE | β-Lactams | # | Exclusion only of anaphylactic shock (most cases with MPE or U/A) |

| Blanca et al,30 2001 | Spain | 81 (67) | Children and adults | Patients (not specified) | Convenience sample | sIgE | Penicillins | Immediate and nonimmediate | Anaphylaxis; U/A; MPE |

| Forrest et al,31 2001 | Canada | 72† | Adults | Inpatients | Convenience sample | Skin tests | Penicillins | Immediate | || |

| Romano et al,32 2002 | Italy | 259 (72.6) | Children and adults | Patients (not specified) | Consecutive sample ¶ | Skin tests (IDT) | Penicillins | Nonimmediate | MPE; U/A |

| Brusca et al,33 2007 | Italy | 122 (57.4) | Children and adults | Outpatients | Consecutive sample ¶ | sIgE | Penicillins** | Immediate | U/A |

| Goldberg and Confino-Cohen,34 2008 | Israel | 169 (62.7) | Children and adults | Outpatients | Consecutive sample ¶ | Skin tests (IDT) | Penicillins | Immediate and nonimmediate | Exclusion only of life-threatening reactions |

| Tantikul et al,35 2008 | Thailand | 4† | Children | Inpatients | Consecutive sample ¶ | Skin tests (SPT) | Amoxicillin** | Immediate and nonimmediate | MPE; U/A |

| Caubet et al,36 2010 | Switzerland | 88 (50) | Children | ED | Consecutive sample ¶ | sIgE | β-Lactams | Nonimmediate | MPE; U/A |

| Macy et al,37 2010 | USA | 150 (69.3) | Adults | Outpatients | Convenience sample | Skin tests (SPT; IDT§); sIgE | Penicillins | Immediate and nonimmediate | Exclusion only of severe mucocutaneous reactions, hemolytic anemia, or nephritis |

| Richter et al,38 2011 | UK | 47† | Adults | Outpatients | Consecutive sample†† | Skin tests (SPT; IDT); sIgE | Penicillins** | Immediate and nonimmediate | U/A; rash; pruritus; other isolated reactions; anaphylaxis |

| Kopac et al,39 2012 | Slovenia | 606 (75.9) | Children and adults | Outpatients | Consecutive sample ¶ | Skin tests (SPT; IDT); sIgE | Penicillins | Immediate and nonimmediate | || |

| Caubet et al,40 2014 | Switzerland | 96† | Children | Outpatients and ED | Convenience sample | Skin tests (IDT) | β-Lactams | Nonimmediate | MPE; U/A |

| Barni et al,41 2015 | Italy | 352 (50.3) | Children | Outpatients | Convenience sample | Skin tests (SPT; IDT§) | Amoxicillin | Nonimmediate | MPE; U/A |

| Mori et al,42 2015 | Italy | 190 (47.9) | Children | Outpatients | Consecutive sample ¶ | Skin tests (SPT; IDT); sIgE | Amoxicillin** | Immediate and nonimmediate | MPE; U/A; others (including anaphylaxis and undefined reactions) |

| Rosenfield et al,43 2015 | Canada | 240 (72.9) | Children and adults | Outpatients | Convenience sample | Skin tests (SPT; IDT§) | β-Lactams | Immediate and nonimmediate | Rash; pruritus; U/A; cardiovascular reactions; others (including anaphylaxis and unknown reactions) |

| Mawhirt et al,44 2016 | USA | 49† | Adults | Inpatients and outpatients | Convenience sample | Skin tests (SPT; IDT§) | Penicillins** | Immediate | Cutaneous or other isolated reactions; mucocutaneous reactions; anaphylaxis |

| Meng et al,45 2016 | UK | 84 (66) | # | Outpatients | Consecutive sample ¶ | Skin tests (SPT; IDT); sIgE | Penicillins | Immediate and nonimmediate | Rash; U/A; anaphylaxis; other/unknown |

| Confino-Cohen et al,46 2017 | Israel | 642 (51.4) | Children and adults | Outpatients | Consecutive sample ¶ | Skin tests (IDT) | Penicillins | Nonimmediate | MPE (90%); U/A; other nonsevere delayed reactions |

| Tannert et al,47 2017 | Denmark | 21 (71) | Adults | Outpatients | Convenience sample | Skin tests (IDT); sIgE | Penicillins | Immediate and nonimmediate | Anaphylaxis; U/A; rash |

| Ibáñez et al,48 2018 | Spain | 732 (48.8) | Children | Outpatients and ED | Consecutive sample ¶ | Skin tests (SPT; IDT); sIgE | Penicillin; amoxicillin-clavulanate; cloxacillin | Immediate and nonimmediate | Exclusion only of severe cutaneous reactions or severe anaphylaxis |

ED, Emergency department; GI, gastrointestinal; IDT, intradermal test; MPE, maculopapular exanthema; SPT, skin prick test; U/A, urticaria/angioedema.

For each primary study, only those diagnostic tests whose accuracy could be calculated are listed.

Sex discrimination not available.

Consecutive sample consisting of all patients with a history of penicillin allergy and in whom penicillin is indicated.

Skin prick tests and intradermal test results were not presented separately.

Not clearly specified for all patients.

Consecutive sample consisting of all participants with history/events compatible with penicillin allergy.

Information not available.

Participants with reported cephalosporin allergy are not being counted.

Consecutive sample consisting of all participants tested for penicillin allergy.

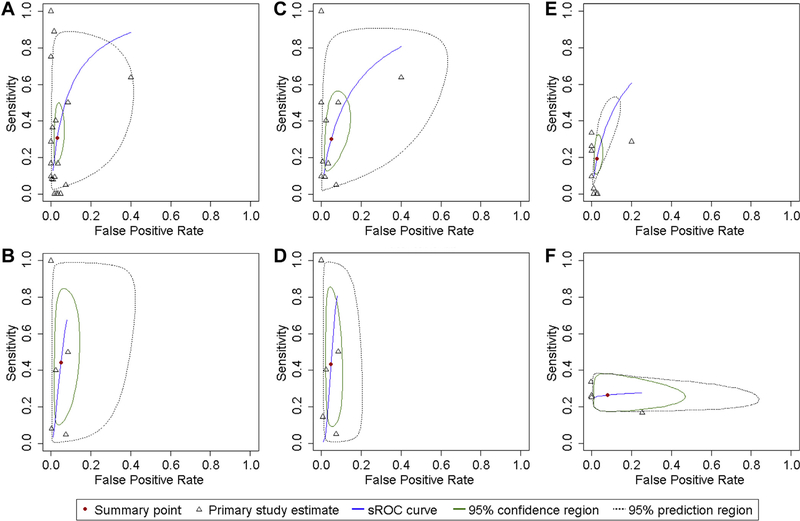

The meta-analysis assessing the diagnostic accuracy of skin tests comprised 20 studies22–29,31,32,34,35,38,40,41,43–46,48 (Fig 2, A; Table II). These studies had been mostly performed in Europe24,26–29,32,38,40,41,45,48 (n = 11) and North America22,23,25,31,43,44 (n = 6), and mostly assessed outpatients23,24,27–29,34,38,40,41,43–46,48 (n = 14). Adults and children were exclusively assessed by 5 studies each,25,28,29,31,35,38,40,41,44,48 whereas 9 studies assessed patients of all age groups.22–24,26,27,32,34,43,46 In 9 studies,26,27,32,34,35,38,45,46,48 aconsecutive sample was assessed, whereas other 9 reported a convenience sample.23,24,28,29,31,40,41,43,44 We obtained a partial AUC-sROC of 0.686, with a summary sensitivity of 30.7% (95% CI, 18.9%−45.8%) and a specificity of 96.8% (95% CI, 94.2%−98.3%). No considerable threshold effect was observed (r = 0.363). Similar results were obtained in sensitivity analyses addressing selection bias or possible sources of confounding, albeit with less precise estimates (Table II). Heterogeneity was found to be moderate (I2 = 38.2%), with the year of publication and performance in Middle East found to be moderators of heterogeneity (Table III). Predictive values estimates are depicted in Fig 3.

FIG 2.

sROC curves for the diagnostic performance of penicillin skin tests (all reactions—A; nonimmediate reactions—B), intradermal tests (all reactions—C; nonimmediate reactions—D), and sIgE quantification (all reactions—E; immediate reactions—F): For each test, the sROC curve plots the respective predicted sensitivity against the false-positive rate. Within it, the summary point indicates the summary (“pooled”) sensitivity and specificity of the respective test (its precision is indicated by a 95% confidence region). Both the summary point and the sROC curve were calculated on the basis of diagnostic measures presented in the included primary studies. Between-studies variability is plotted through 95% prediction regions, which indicate the region where we are most confident the test diagnostic performance lies. For immediate reactions, we were not able to plot sROC curves, as we did not have a sufficient number of studies presenting values for true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives.

TABLE II.

Results of the bivariate diagnostic random-effects meta-analyses for penicillin allergy diagnostic tests

| Diagnostic test | No. of studies | AUC-sROC | Partial AUC-sROC | Summary measures (95% CI) |

Correlation coefficient* | I2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | LR+ | LR− | DOR | ||||||

| Skin tests | 20 | 0.841 | 0.686 | 30.7% (18.9%–45.8%) | 96.8% (94.2%–98.3%) | 10.1 (4.9–18.6) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 14.7 (6.2–29.7) | 0.363 | 38.2% |

| More than 50% participants† | 8 | 0.842 | 0.667 | 39.2% (14.6%–70.0%) | 93.5% (83.0%–97.8%) | 6.6 (2.1–16.0) | 0.6 (0.3–0.9) | 11.6 (2.5–34.5) | 0.545 | 45.5% |

| Generalized provocation tests‡ | 4 | 0.694 | 0.480 | 41.2% (14.2%–75.0%) | 87.4% (54.0%–97.6%) | 3.6 (1.4–8.5) | 0.7 (0.4–0.9) | 5.5 (1.9–12.6) | 1.000 | 36.4% |

| Consecutive sample§ | 6 | 0.655 | 0.449 | 23.3% (9.3%–47.3%) | 95.6% (83.8%–98.9%) | 6.5 (1.4–19.8) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 8.7 (1.5–28.7) | 0.416 | 65.5% |

| Adult participants | 5 | 0.677 | 0.228 | 24.2% (11.7%–43.5%) | 97.6% (94.1%–99.0%) | 12.2 (2.7–34.6) | 0.8 (0.6–0.9) | 17.2 (3.0–55.9) | −1.000 | 0% |

| Pediatric participants | 5 | 0.857 | 0.338 | 31.5% (10.6%–64.1%) | 96.0% (87.8%–98.7%) | 7.9 (3.9–14.5) | 0.7 (0.4–0.9) | 11.8 (5.0–23.8) | 1.000 | 20.2% |

| Skin tests (nonimmediate reactions)||,¶ | 7 | 0.926 | 0.396 | 44.2% (14.2%–79.1%) | 95.1% (88.3%–98.0%) | 9.7 (2.6–23.5) | 0.6 (0.2–0.9) | 21.4 (3.0–76.7) | 0.335 | 22.2% |

| Intradermal tests|| | 10 | 0.778 | 0.582 | 29.9% (15.0%–50.8%) | 95.1% (88.1%–98.0%) | 6.5 (2.6–13.6) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 9.2 (3.2–21.1) | 0.607 | 54.8% |

| Intradermal tests (nonimmediate reactions)||,¶ | 6 | 0.939 | 0.404 | 43.1% (12.8%–79.5%) | 95.1% (90.9%–97.5%) | 9.7 (2.1–23.5) | 0.6 (0.2–0.9) | 23.0 (2.3–94.1) | −0.194 | 35.3% |

| Specific IgE | 11 | 0.760 | 0.420 | 19.3% (12.0%–29.4%) | 97.4% (95.2%–98.6%) | 7.7 (3.8–13.8) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 8.8 (4.3–17.9) | 1.000 | 8.5% |

| More than 50% participants† | 6 | 0.910 | 0.132 | 17.4% (8.7%–31.0%) | 97.6% (96.0%–98.7%) | 7.9 (3.4–15.6) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 9.7 (3.7–21.0) | 1.000 | 0%# |

| Specific IgE (immediate reactions)|| | 4 | 0.279 | 0.262 | 26.2% (18.7%–35.3%) | 92.1% (64.7%–98.7%) | 5.2 (0.7–21.0) | 0.8 (0.7–1.2) | 6.8 (0.6–29.2) | −1.000 | 0%# |

DOR, Diagnostic odds ratio; LR, likelihood ratio; z, z score.

Correlation coefficient between sensitivity and false-positive rate.

Sensitivity analysis restricted to studies in which at least 50% of both patients with positive and negative results on index tests received a DPT.

Studies assessing a mix of participants with immediate and nonimmediate reactions (excluding only those with very severe index reactions), and testing all with index tests and DPT.

Sensitivity analysis restricted to consecutive samples of patients specifically reporting a history of penicillin allergy and testing for penicillin polylysine, minor determinant mixture, benzylpenicillin, and an aminopenicillin.

Insufficient number of studies to perform sensitivity analyses as prespecified.

All participants had maculopapular exanthema or urticaria/angioedema as their index reaction.

Obtained with the Higgins estimator.

TABLE III.

Variables identified as associated with heterogeneity in the bivariate diagnostic random-effects meta-analyses for penicillin allergy diagnostic tests

| Diagnostic test | Variables associated with heterogeneity* | Variables associated with heterogeneity in summary sensitivity estimation† | Variables associated with heterogeneity in summary specificity estimation† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin tests | Year (P = .002); Middle East (P = .002) | Year (z = −2.8; P = .005) | Middle East (z = −3.4; P = .001) |

| Skin tests (nonimmediate reactions) | Year (P = .02); Europe (P = .05); Middle East (P = .02); suspected drug testing (P = .02) | Year (z = −2.9; P = .004) | — |

| Intradermal tests | Europe (P = .001); Middle East (P = .001); suspected drug testing (P = .02) | — | Europe (z = 2.4; P = .02); Middle East (z = −2.4; P = .02) |

| Intradermal tests (nonimmediate reactions) | Year (P = .010); Europe (P = .05); Middle East (P = .05); suspected drug testing (P = .05) | Year (z = −2.7; P = .006) | Reported allergy to aminopenicillins (z = −2.2; P = .03) |

| Specific IgE‡ | Adults (P = .04) | Emergency department (z = −2.0; P = .05) | Adults (z = −2.6; P = .009) |

Adults, Assessment of adult patients; Year, publication year; z, z score.

As assessed by the likelihood-ratio test.

As assessed by meta-regression.

Insufficient number of studies assessing only participants reporting immediate reactions to perform meta-regression.

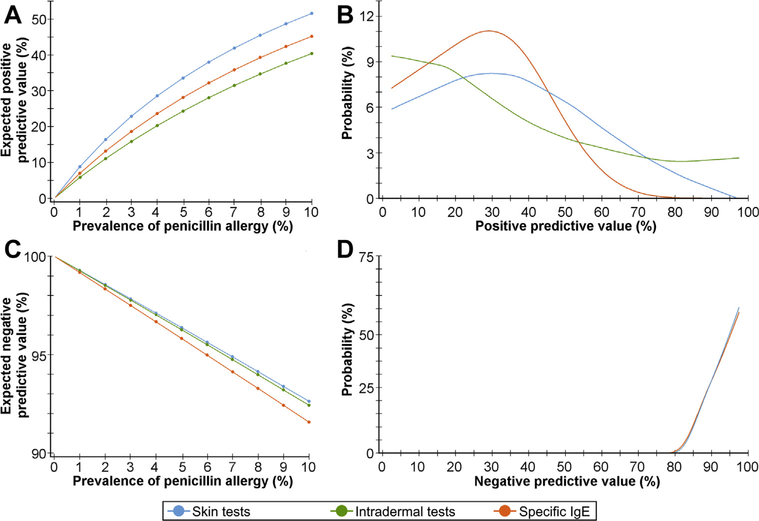

FIG 3.

Estimates of the positive and negative predictive values based on the pooled sensitivity and specificity obtained by bivariate meta-analysis. A, Estimates of the PPVs across a range of penicillin allergy prevalences (univariate sensitivity analysis). B, Probability distributions (“Probability (%)”) of the PPVs obtained by means of probabilistic sensitivity analyses. C, Estimates of the negative predictive value across a range of penicillin allergy prevalences (univariate sensitivity analysis). D, Probability distributions (“Probability (%)”) of the negative predictive values obtained by means of probabilistic sensitivity analyses.

For nonimmediate reactions (and contrary to immediate reactions), we were able to perform a bivariate random-effects meta-analysis on the diagnostic accuracy of skin tests. This analysis was based on 7 studies26,28,32,35,40,41,46 (Fig 2, B; Table II), with almost all participants reporting either maculopapular exanthema or urticaria/angioedema. The partial AUC-sROC was of 0.396 (r = 0.335), the summary sensitivity was of 44.2% (95% CI, 14.2%−79.1%), the specificity was of 95.1% (95% CI, 88.3%−98.0%), and an I2 of 22.2% was obtained.

For skin prick tests, we were able to estimate only pooled single diagnostic measures (Table E4). Regarding intradermal tests, we performed a bivariate diagnostic random-effects meta-analysis (Fig 2, C; Table II) based on 10 studies24,26,28,32,34,38,40,42,46,48—we observed a partial AUC-sROC of 0.582, a summary sensitivity of 29.9% (95% CI, 15.0%−50.8%), and a specificity of 95.1% (95% CI, 88.1%−98.0%). A borderline threshold effect was observed (r = 0.607) along with severe heterogeneity (I2 = 54.8%). Performance in Europe and testing the suspected culprit drug were identified as moderators of heterogeneity (Table III). Among patients reporting nonimmediate reactions (largely maculopapular exanthema or urticaria/angioedema),26,28,32,40,42,46 a partial AUC-sROC of 0.404 was obtained (Fig 2, D; Table II), with a summary sensitivity of 43.1% (95% CI, 12.8%−79.5%) and a specificity of 95.1% (95% CI, 90.9%−97.5%). No relevant threshold effect was observed (r = −0.194), and moderate heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 35.3%).

Eleven studies were included in the meta-analysis assessing the accuracy of specific IgE.24,28,30,33,36–39,42,47,48 The studies had been mostly performed in Europe (n = 10),24,28,30,33,36,38,39,42,47,48 and among outpatients (n = 9).24,28,33,36–39,42,47,48 Four studies assessed adults,28,37,38,47 whereas 3 assessed children36,42,48 and other 4 studies patients of all age groups.24,30,33,39 The sampling method was consecutive for 6 studies33,36,38,39,42,48 and of convenience for 5 studies.24,28,30,37,47 We obtained a partial AUC-sROC of 0.420, but considerable threshold effect was observed (r = 1.000) (Fig 2, E; Table II). This model resulted in a summary sensitivity of 19.3% (95% CI, 12.0%−29.4%) and a specificity of 97.4% (95% CI, 95.2%−98.6%). Similar results were obtained in a sensitivity analysis (Table II). Heterogeneity was found to be low (I2 = 8.5%), with participants’ age identified as a moderator of heterogeneity (Table III). Predictive value estimates are depicted in Fig 3. Among patients reporting immediate reactions,28,33,42,47 we obtained a partial AUC-sROC of 0.262, with a summary sensitivity of 26.2% (95% CI, 18.7%−35.3%) and a summary specificity of 92.1% (95% CI, 64.7%−98.7%).

Studies’ quality was assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool16—Fig E1 depicts the risk-of-bias graph, whereas Table E5 presents the risk-of-bias summary. The main quality concerns of the assessed studies are related to patients’ flow (in most studies, not all tested patients received a DPT) and to “patient selection domain” (reflecting concerns on sample representativity). Of all included primary studies, only 2 (1.9%) were judged as “low risk” on all bias-related domains,42,46 while 12 (11.4%) were judged as “low concern” on all applicability domains.24,27,32,34,39,69,77,102,111,114,120,123

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, we assessed the diagnostic accuracy of skin tests and sIgE quantification for patients reporting a penicillin allergy. In all performed analyses, both skin tests and sIgE assessment were found to have a high specificity but a sensitivity to predict hypersensitivity reactions of less than 50%. Based on these obtained values, and on a plausible range of penicillin allergy prevalences, these tests were projected to have a high NPV, but a poor PPV.

Importantly, predictive values are influenced by the prevalence of the studied condition, in this case corresponding to the pretest probability of having a true penicillin allergy. For most primary studies we do not have individual participant-level information on the presentation/severity of the index reaction (nor were defined homogeneous inclusion criteria regarding the latter). However, we have information that most participants reported a mild index reaction, reflecting the fact that most included studies consist of a description of a mostly low-risk cohort of patients undergoing a diagnostic workup for penicillin allergy. This may explain why the PPVs projected by our models were lower than those estimated by a recent review, which identified a PPV of 81%.126 However, that latter review included only studies with detailed characterizations of each participant’s index reaction (and tested with the culprit drug), who, as such, had a higher pretest probability of having a true/severe allergic reaction. Although we were not able to estimate the diagnostic accuracy of skin tests and specific IgE for each clinical presentation or risk group,127 we were able to estimate the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values for penicillin skin tests in patients reporting a delayed maculopapular exanthema or urticaria/angioedema. Therefore, our results apply largely to the most common patients encountered, particularly in North America, namely low-risk patients with rashes and/or swelling.

This study has some limitations, particularly associated with the included primary studies (Table IV lists the limitations of current evidence and key requirements needed for future studies). First, only a minority of them performed DPT in participants with positive index results. As a result, our bivariate diagnostic meta-analysis included fewer primary studies than the corresponding individual diagnostic measures meta-analyses. Nevertheless, we obtained comparable results for the analyses in which the 2 meta-analytic methods were used. Another limitation concerns the possibility of selection bias—in several studies, not all participants who were subject to an index test underwent a DPT. This is particularly true for patients with positive index test results, with possible implications for sensitivity estimation. In fact, there were studies that only challenged patients with mild or borderline positive skin test results.23,43 To account for this possible bias, we performed sensitivity analyses restricted to (1) studies with at least 50% patients with positive results on the index test performing a DPT and (2) studies assessing a mix of participants with immediate and nonimmediate reactions (excluding only those with very severe index reactions), and testing all with index tests and DPTs. Those sensitivity analyses yielded similar results, although with less precision due to the lower number of primary studies. Nevertheless, even in those studies, most participants reported a clinical history compatible with a mild index reaction.

TABLE IV.

Limitations of current evidence and key aspects for future studies

| Limitations of current evidence | Key requirements needed for future studies |

|---|---|

| - Inconsistent eligibility criteria often creating heterogeneous patient mixes; | - Definition of more homogeneous inclusion criteria to have less patient variation; |

| - Inconsistent reporting of demographic and clinical details (eg, timing or clinical manifestations of index reactions); | - Standardization of testing protocols; |

| - Limited ability to assess accuracy of skin tests and specific IgE for different clinical phenotypes or risk groups (except nonimmediate maculopapular exanthema or urticaria/angioedema); | - Limitation of selection bias through reporting of consecutive samples; |

| - Potential selection bias related to using DPTs; | - Inclusion of comprehensive details of index reactions (eg, clinical manifestations and timing); |

| - Limited data from Latin America, Asia, and Africa. | - Presentation of results stratified by different reaction phenotypes and risk groups OR publication of anonymized patient-level data. |

In addition, in several studies, more than 1 index test was performed, with DPT being done only in those patients who had negative results in all index tests—one particularly common example is the sequential execution of skin prick and intradermal tests before DPT. Therefore, our pooled estimates do not strictly measure the “pure” accuracy of each index test. Nevertheless, for individual diagnostic measures meta-analyses, similar results are obtained when analyzing only studies performing DPT in all patients with negative and/or positive results in the corresponding index tests. We were not able to assess the accuracy of skin prick tests by bivariate random-effects meta-analysis. Nevertheless, results of individual diagnostic measures meta-analyses point to a lower sensitivity of skin prick tests (14.6%) when compared with intradermal tests (29.9%) or with the performance of both skin prick and intradermal tests (30.7%)—the performance of skin prick tests without intradermal tests can result in nonidentifying a larger proportion of patients with allergy.

Other important limitations concern the low quality of most included primary studies and—for some studies— lack of discriminated information regarding the timing of initial reactions (on the other hand, patient-reported initial reaction timing may be subject to recall bias). Finally, although DPT was defined as the reference standard, its accuracy is not 100%, and protocol variability might affect the primary studies results.

This study also has several strengths. In particular, we combined 2 different methods—bivariate diagnostic and individual measure meta-analyses—to estimate summary measures, obtaining comparable results. To minimize the impact of publication bias, we searched 3 different electronic bibliographic databases without applying exclusion criteria based on the date or language of publication. In addition, we performed meta-regression and sensitivity and subgroup analyses to explore sources of heterogeneity and hint at variables possibly associated with differences in penicillin allergy tests’ diagnostic accuracy. Heterogeneity was low/moderate in most bivariate random-effects meta-analyses, with substantial heterogeneity observed in only 2 analyses (in the remaining 10, heterogeneity was found to be low or moderate). The year of publication, the region, and whether the suspected culprit drug was tested were identified as the main variables explaining heterogeneity. A more recent year was associated with a decreased summary sensitivity of skin tests—this may indicate an improvement in DPT procedures, with more recent studies following/contacting patients for a longer period of time after performing a DPT, and not simply a worsening accuracy of skin tests.128 Regarding the region, recent surveys found important regional differences in the diagnostic workup of penicillin allergy.129,130 The included primary studies presented several other differences in their diagnostic approaches (eg, regarding testing for minor determinant mixture, whose individual role we were not able to adequately assess). However, these differences were frequently not identified as moderators of heterogeneity, and similar results were obtained with the sensitivity analysis restricted to studies with a “more homogeneous approach” (which included testing for penicillin polylysine, minor determinant mixture, benzylpenicillin, and an aminopenicillin).

The topic of this systematic review is particularly relevant and timely because penicillin allergy delabeling is now encouraged as a tool of antibiotic stewardship and quality improvement by several organizations—including the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Overall, our results suggest that, at least in patients reporting a delayed mild index reaction, skin tests may have a high specificity and NPV, but a low PPV and sensitivity in identifying patients who will develop a hypersensitivity reaction when exposed to penicillins. If that trend is confirmed by subsequent studies, direct performance of DPT may be a feasible and safe option at least in some of those patients—in fact, recent studies have shown that patients whose clinical history is nonsevere and imprecise or not compatible with a true reaction may possibly safely undergo DPT without prior skin tests, particularly if the reaction did not occur within 1 hour of penicillin ingestion.131,132 In addition, our systematic review points to the need for further studies minimizing the risk of selection bias and providing, if not individual-level participant data, at least results by type of index reaction clinical presentation. Such evidence would help in patient stratification, so that penicillin allergy delabeling could be safely performed in the most accurate way for each patient.

Supplementary Material

Clinical implications:

In patients reporting a penicillin allergy, skin tests (at least in nonimmediate mild reactions) and sIgE quantification appear to have high specificity and negative predictive value, but low sensitivity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Portuguese Ministry for Science, Technology and Higher Education (Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior), through the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia; grant no. PD/BD/129836/2017). K.G.B. receives career development support from the National Institutes of Health (grant no. NIH K01AI125631), the American Academy of Audiology, Asthma & Immunology Foundation, and the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Claflin Distinguished Scholar Award.

Abbreviations used

- AUC-sROC

Area under the summary receiver-operating characteristic curve

- DPT

Drug provocation test

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- sIgE

Specific IgE

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: K. G. Blumenthal has a clinical decision support tool for inpatient beta-lactam allergy evaluation used at Partners HealthCare Systems and licensed to Persistent Systems, and receives career development support from the National Institutes of Health (grant no. NIH K01AI125631), the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology (AAAAI) Foundation, and the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Claflin Distinguished Scholar Award. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the AAAAI Foundation, or the MGH. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Macy E, Poon KYT. Self-reported antibiotic allergy incidence and prevalence: age and sex effects. Am J Med 2009;122:778.e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sousa-Pinto B, Fonseca JA, Gomes ER. Frequency of self-reported drug allergy: a systematic review and meta-analysis with meta-regression. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2017;119:362–73.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, Phillips EJ. Antibiotic allergy. Lancet 2019;393:183–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee CE, Zembower TR, Fotis MA, Postelnick MJ, Greenberger PA, Peterson LR, et al. The incidence of antimicrobial allergies in hospitalized patients: implications regarding prescribing patterns and emerging bacterial resistance. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2819–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomes E, Cardoso MF, Praca F, Gomes L, Marino E, Demoly P. Self-reported drug allergy in a general adult Portuguese population. Clin Exp Allergy 2004; 34:1597–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harandian F, Pham D, Ben-Shoshan M. Positive penicillin allergy testing results: a systematic review and meta-analysis of papers published from 2010 through 2015. Postgrad Med 2016;128:557–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattingly TJ II, Fulton A, Lumish RA, Williams AMC, Yoon S, Yuen M, et al. The cost of self-reported penicillin allergy: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;6:1649–54.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sousa-Pinto B, Cardoso-Fernandes A, Araujo L, Fonseca JA, Freitas A, Delgado L. Clinical and economic burden of hospitalizations with registration of penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018;120:190–4.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blumenthal KG, Lu N, Zhang Y, Li Y, Walensky RP, Choi HK. Risk of meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile in patients with a documented penicillin allergy: population based matched cohort study. BMJ 2018; 361:k2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: a review. JAMA 2019;321:188–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demoly P, Adkinson NF, Brockow K, Castells M, Chiriac AM, Greenberger PA, et al. International Consensus on drug allergy. Allergy 2014;69:420–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES. Am I allergic to penicillin? JAMA 2019;321:216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fontaine C, Mayorga C, Bousquet J, Arnoux B, Torres MJ, Blanca M, et al. Relevance of the determination of serum-specific IgE antibodies in the diagnosis of immediate β-lactam allergy. Allergy 2006;62:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McInnes MDF, Moher D, Thombs BD, McGrath TA, Bossuyt PM. PRISMA-DTA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies: the PRISMA-DTA statement. JAMA 2018; 319:388–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Astin MP, Brazzelli MG, Fraser CM, Counsell CE, Needham G, Grimshaw JM. Developing a sensitive search strategy in MEDLINE to retrieve studies on assessment of the diagnostic performance of imaging techniques. Radiology 2008;247: 365–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:529–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reitsma JB, Glas AS, Rutjes AW, Scholten RJ, Bossuyt PM, Zwinderman AH. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:982–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harbord RM, Deeks JJ, Egger M, Whiting P, Sterne JA. A unification of models for meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Biostatistics 2007;8:239–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deville WL, Buntinx F, Bouter LM, Montori VM, de Vet HC, van der Windt DA, et al. Conducting systematic reviews of diagnostic studies: didactic guidelines. BMC Med Res Methodol 2002;2:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou Y, Dendukuri N. Statistics for quantifying heterogeneity in univariate and bivariate meta-analyses of binary data: the case of meta-analyses of diagnostic accuracy. Stat Med 2014;33:2701–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipsey MW. Those confounded moderators in meta-analysis: good, bad, and ugly. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 2003;587:69–81. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levine BB, Zolov DM. Prediction of penicillin allergy by immunological tests. J Allergy 1969;43:231–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warrington RJ, Simons FER, Ho HW, Gorski BA. Diagnosis of penicillin allergy by skin testing: the Manitoba experience. CMAJ 1978;118:787–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanca M, Vega JM, Garcia J, Carmona MJ, Terados S, Avila MJ, et al. Allergy to penicillin with good tolerance to other penicillins: study of the incidence in subjects allergic to betalactams. Clin Exp Allergy 1990;20:475–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sogn DD, Evans R III, Shepherd GM, Casale TB, Condemi J, Greenberger PA, et al. Results of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases collaborative clinical trial to test the predictive value of skin testing with major and minor penicillin derivatives in hospitalized adults. Arch Intern Med 1992; 152:1025–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romano A, Di Fonso M, Papa G, Pietrantonio F, Federico F, Fabrizi G, et al. Evaluation of adverse cutaneous reactions to aminopenicillins with emphasis on those manifested by maculopapular rashes. Allergy 1995;50:113–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sastre J, Quijano LD, Novalbos A, Hernandez G, Cuesta J, de las Heras M, et al. Clinical cross-reactivity between amoxicillin and cephadroxil in patients allergic to amoxicillin and with good tolerance of penicillin. Allergy 1996;51:383–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cederbrant K, Stejskal V, Broman P, Lindkvist L, Sundell K. In vitro lymphocyte proliferation in the diagnosis of allergy to phenoxymethylpenicillin. Allergy 1998;53:1155–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loza Cortina C Adverse drug reactions in area I of Asturias. An Esp Pediatr 1998;49:359–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blanca M, Mayorga C, Torres MJ, Reche M, Moya MC, Rodriguez JL, et al. Clinical evaluation of Pharmacia CAP System (TM) RAST FEIA amoxicilloyl and benzylpenicilloyl in patients with penicillin allergy. Allergy 2001;56:862–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forrest DM, Schellenberg RR, Thien VVS, King S, Anis AH, Dodek PM. Introduction of a practice guideline for penicillin skin testing improves the appropriateness of antibiotic therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:1685–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romano A, Viola M, Mondino C, Pettinato R, Di Fonso M, Papa G, et al. Diagnosing nonimmediate reactions to penicillins by in vivo tests. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2002;129:169–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brusca I, Corrao S, Sceusa G, Barrale M, Dragotto G, Gristina T, et al. Flow cytometric basophil activation test in patients with allergic or pseudoallergic reactions to betalactamic antibiotics and non steroidal and inflammatory drugs. Rivista Italiana della Medicina di Laboratorio 2007;3:196–202. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldberg A, Confino-Cohen R. Skin testing and oral penicillin challenge in patients with a history of remote penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008;100:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tantikul C, Dhana N, Jongjarearnprasert K, Visitsunthorn N, Vichyanond P, Jirapongsananuruk O. The utility of the World Health Organization-The Uppsala Monitoring Centre (WHO-UMC) system for the assessment of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized children. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 2008;26: 77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caubet JC, Kaiser L, Lemaitre B, Fellay B, Gervaix A, Eigenmann PA. The role of penicillin in benign skin rashes in childhood: a prospective study based on drug rechallenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;127:218–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macy E, Goldberg B, Poon KY. Use of commercial anti-penicillin IgE fluorometric enzyme immunoassays to diagnose penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2010;105:136–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richter AG, Wong G, Goddard S, Heslegrave J, Derbridge C, Srivastava S, et al. Retrospective case series analysis of penicillin allergy testing in a UK specialist regional allergy clinic. J Clin Pathol 2011;64:1014–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kopac P, Zidarn M, Kosnik M. Epidemiology of hypersensitivity reactions to penicillin in Slovenia. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat 2012;21: 5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caubet JC, Frossard C, Fellay B, Eigenmann PA. Skin tests and in vitro allergy tests have a poor diagnostic value for benign skin rashes due to β-lactams in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2014;26:80–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barni S, Mori F, Sarti L, Pucci N, Rossi EM, de Martino M, et al. Utility of skin testing in children with a history of non-immediate reactions to amoxicillin. Clin Exp Allergy 2015;45:1472–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mori F, Cianferoni A, Barni S, Pucci N, Rossi ME, Novembre E. Amoxicillin allergy in children: five-day drug provocation test in the diagnosis of nonimmediate reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015;3:375–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenfield L, Kalicinsky C, Warrington R. A retrospective comparison of false negative skin test rates in penicillin allergy, using pencilloyl-poly-lysine and minor determinants or Penicillin G, followed by open challenge. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2015;11:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mawhirt SL, Fonacier LS, Calixte R, Davis-Lorton M, Aquino MR. Skin testing and drug challenge outcomes in antibiotic-allergic patients with immediate-type hypersensitivity. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2016;118:73–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meng J, Thursfield D, Lukawska JJ. Allergy test outcomes in patients self-reported as having penicillin allergy: two-year experience. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2016;117:273–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Confino-Cohen R, Rosman Y, Meir-Shafrir K, Stauber T, Lachover-Roth I, Hershko A, et al. Oral challenge without skin testing safely excludes clinically significant delayed-onset penicillin hypersensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017;5:669–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tannert LK, Falkencrone S, Mortz CG, Bindslev-Jensen C, Skov PS. Is a positive intracutaneous test induced by penicillin mediated by histamine? A cutaneous microdialysis study in penicillin-allergic patients. Clin Transl Allergy 2017;7:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ibanez MD, Del Rio PR, Lasa EM, Joral A, Ruiz-Hornillos J, Munoz C, et al. Prospective assessment of diagnostic tests for pediatric penicillin allergy, from clinical history to challenge tests. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018;121: 235–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown BC, Price EV, Moore MB Jr. Penicilloyl-polylysine as an intradermal test of penicillin sensitivity. JAMA 1964;189:599–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Resnik SS, Shelley WB. Penicillin hypersensitivity: detection by basophil response to challenge. J Investig Dermatol 1965;45:269–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wide L, Juhlin L. Detection of penicillin allergy of the immediate type by radioimmunoassay of reagins (IgE) to penicilloyl conjugates. Clin Exp Allergy 1971;1: 171–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Basomba A, Villalmanzo IG, Campos A, Pelaez A, Berglund A. IgE antibodies against penicillin as determined by Phadebas RAST. Clin Allergy 1979;9:515–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sullivan TJ, Wedner HJ, Shatz GS, Yecies LD, Parker CW. Skin testing to detect penicillin allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1981;68:171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.VanArsdel PP Jr, Martonick GJ, Johnson LE, Sprenger JD, Altman LC, Henderson WR Jr. The value of skin testing for penicillin allergy diagnosis. West J Med 1986;144:311–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Graff-Lonnevig V, Hedlin G, Lindfors A. Penicillin allergy—a rare paediatric condition? Arch Dis Child 1988;63:1342–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Surtees SJ, Stockton MG, Gietzen TW. Allergy to penicillin: fable or fact? BMJ 1991;302:1051–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gadde J, Spence M, Wheeler B, Adkinson NF. Clinical-experience with penicillin skin testing in a large inner-city STD clinic. JAMA 1993;270:2456–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Juchet A, Rancé F, Brémont F, Dutau G. Investigation of beta-lactam allergy in 45 children. Revue Francaise d’allergologie et d’immunologie Clinique 1994;34: 369–75. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Macy E, Richter PK, Falkoff R, Zeiger R. Skin testing with penicilloate and penilloate prepared by an improved method: amoxicillin oral challenge in patients with negative skin test responses to penicillin reagents. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997;100:586–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hervé M, De la Rocque F, Bouhanna A, Albengres E, Reinert P. Exploration of 112 children suspected of amoxicillin allergy: indications and efficacy of oral provocation test. Arch Pediatr 1998;5:503–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pichichero ME, Pichichero DM. Diagnosis of penicillin, amoxicillin, and cephalosporin allergy: reliability of examination assessed by skin testing and oral challenge. J Pediatr 1998;132:137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lebel B, Messaad D, Kvedariene V, Rongier M, Bousquet J, Demoly P. Cysteinylleukotriene release test (CAST) in the diagnosis of immediate drug reactions. Allergy 2001;56:688–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.López Tiro JJ, Orea Solano M, Flores Sandoval G, Gómez Vera J. Skin tests with high and minor determinants in patients with doubtful allergy to penicillin. Rev Alerg Mex 2001;48:80–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Novalbos A, Sastre J, Cuesta J, De Las Heras M, Lluch-Bernal M, Bombın C, et al. Lack of allergic cross-reactivity to cephalosporins among patients allergic to penicillins. Clin Exp Allergy 2001;31:438–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Solensky R, Earl HS, Gruchalla RS. Lack of penicillin resensitization in patients with a history of penicillin allergy after receiving repeated penicillin courses. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:822–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Torres MJ, Mayorga C, Leyva L, Guzman AE, Cornejo-García JA, Juarez C, et al. Controlled administration of penicillin to patients with a positive history but negative skin and specific serum IgE tests. Clin Exp Allergy 2002;32:270–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Borch JE, Andersen KE, Bindslev-Jensen C. The prevalence of suspected and challenge-verified penicillin allergy in a university hospital population. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2006;98:357–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wong BBL, Keith PK, Waserman S. Clinical history as a predictor of penicillin skin test outcome. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006;97:169–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bousquet PJ, Kvedariene V, Co-Minh HB, Martins P, Rongier M, Arnoux B, et al. Clinical presentation and time course in hypersensitivity reactions to β-lactams. Allergy 2007;62:872–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.del Real GA, Rose ME, Hammel J, Gordon SM, Arroliga ME. The penicillin skin test has a high negative predictive value and helps to modify the use of antibiotics in patients with history of beta-lactam allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;117: S224. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rebelo Gomes E, Fonseca J, Araujo L, Demoly P. Drug allergy claims in children: from self-reporting to confirmed diagnosis. Clin Exp Allergy 2007;38: 191–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bousquet PJ, Pipet A, Bousquet-Rouanet L, Demoly P. Oral challenges are needed in the diagnosis of β-lactam hypersensitivity. Clin Exp Allergy 2008; 38:185–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nolan RC, Puy R, Deckert K, O’Hehir RE, Douglass JA. Experience with a new commercial skin testing kit to identify IgE-mediated penicillin allergy. Intern Med J 2008;38:357–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Padial A, Antunez C, Blanca-Lopez N, Fernandez TD, Cornejo-Garcia JA, Mayorga C, et al. Non-immediate reactions to beta-lactams: diagnostic value of skin testing and drug provocation test. Clin Exp Allergy 2008;38:822–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rodriguez-Alvarez M, Santos-Magadan S, Rodriguez-Jimenez B, de Arellano IRR, Vazquez-Cortes S, Martinez-Cocera C. Reproducibility of delayed-type reactions to betalactams. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2008;36:201–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hershkovich J, Broides A, Kirjner L, Smith H, Gorodischer R. Beta lactam allergy and resensitization in children with suspected beta lactam allergy. Clin Exp Allergy 2009;39:726–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Silva R, Cruz L, Botelho C, Cadinha S, Castro E, Rodrigues J, et al. Work up of patients with history of beta-lactam hypersensitivity. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2009;37:193–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chambel M, Martins P, Silva I, Palma-Carlos S, Romeira AM, Pinto PL. Drug provocation tests to betalactam antibiotics: experience in a paediatric setting. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2010;38:300–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Holm A, Mosbech H. Challenge test results in patients with suspected penicillin allergy, but no specific IgE. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2011;3:118–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kamboj S, Yousef E, McGeady S, Hossain J. The prevalence of antibiotic skin test reactivity in a pediatric population. Allergy Asthma Proc 2011;32:99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moral L, Garde J, Toral T, Fuentes MJ, Marco N. Short protocol for the study of paediatric patients with suspected betalactam antibiotic hypersensitivity and low risk criteria. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2011;39:337–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Na HR, Lee JM, Jung JW, Lee SY. Usefulness of drug provocation tests in children with a history of adverse drug reaction. Korean J Pediatr 2011;54:304–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ponvert C, Perrin Y, Bados-Albiero A, Le Bourgeois M, Karila C, Delacourt C, et al. Allergy to betalactam antibiotics in children: results of a 20-year study based on clinical history, skin and challenge tests. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2011;22:411–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Seitz CS, Brocker EB, Trautmann A. Diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity in children and adolescents: discrepancy between physician-based assessment and results of testing. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2011;22:405–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Celik GE, Aydin O, Dogu F, Cipe F, Boyvat A, Ikinciogullari A, et al. Diagnosis of immediate hypersensitivity to b -lactam antibiotics can be made safely with current approaches. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2012;157:311–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Garcia Nunez I, Barasona Villarejo MJ, Algaba Marmol MA, Moreno Aguilar C, Guerra Pasadas F. Diagnosis of patients with immediate hypersensitivity to beta-lactams using retest. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2012;22:41–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hjortlund J, Mortz CG, Skov PS, Eller E, Poulsen JM, Borch JE, et al. One-week oral challenge with penicillin in diagnosis of penicillin allergy. Acta Derm Venereol 2012;92:307–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Iglesias-Souto J, Gonzalez R, Poza P, Sanchez-Machin I, Matheu V. Evaluating the usefulness of retesting for beta-lactam allergy in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2012;31:1091–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Soto L, Guilarte M, Luengo O, Labrador M, Sala A. Drug hypersensitivity to beta-lactams: a retrospective study to assess a diagnostic challenge. Allergy 2012;67: 429. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Erkocoglu M, Kaya A, Civelek E, Ozcan C, Cakır B, Akan A, et al. Prevalence of confirmed immediate type drug hypersensitivity reactions among school children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2013;24:160–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hjortlund J, Mortz CG, Skov PS, Bindslev-Jensen C. Diagnosis of penicillin allergy revisited: the value of case history, skin testing, specific IgE and prolonged challenge. Allergy 2013;68:1057–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Macy E, Ngor EW. Safely diagnosing clinically significant penicillin allergy using only penicilloyl-poly-lysine, penicillin, and oral amoxicillin. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2013;1:258–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rimawi RH, Cook PP, Gooch M, Kabchi B, Ashraf MS, Rimawi BH, et al. The impact of penicillin skin testing on clinical practice and antimicrobial stewardship. J Hosp Med 2013;8:341–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Al-Ahmad M, Rodriguez Bouza T, Arifhodzic N. Penicillin allergy evaluation: experience from a drug allergy clinic in an Arabian Gulf Country, Kuwait. Asia Pac Allergy 2014;4:106–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bourke J, Pavlos R, James I, Phillips E. Improving the effectiveness of penicillin allergy de-labeling. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2014;3:365–74.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Colas H, David V, Molle I, Bernier C, Magnan A, Pipet A. Drug provocation tests for children: in-hospital or in an outpatient consultation? A protocol comparing the two possibilities. Revue Francaise D Allergologie 2014;54:300–6. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fox SJ, Park MA. Penicillin skin testing is a safe and effective tool for evaluating penicillin allergy in the pediatric population. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2014; 2:439–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Picard M, Paradis L, Bégin P, Paradis J, Des Roches A. Skin testing only with penicillin G in children with a history of penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2014;113:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Trautmann A, Seitz CS, Stoevesandt J, Kerstan A. Aminopenicillin-associated exanthem: lymphocyte transformation testing revisited. Clin Exp Allergy 2014;44: 1531–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zambonino MA, Corzo JL, Munoz C, Requena G, Ariza A, Mayorga C, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of hypersensitivity reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics in a large population of children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2014;25:80–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Blanca-Lopez N, Perez-Alzate D, Ruano F, Garcimartin M, de la Torre V, Mayorga C, et al. Selective immediate responders to amoxicillin and clavulanic acid tolerate penicillin derivative administration after confirming the diagnosis. Allergy 2015;70:1013–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ferré-Ybarz L, Salinas Argente R, Gómez Galán C, Duocastella Selvas P, Nevot Falcó S. Analysis of profitability in the diagnosis of allergy to beta-lactam antibiotics. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2015;43:369–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Abrams EM, Wakeman A, Gerstner TV, Warrington RJ, Singer AG. Prevalence of beta-lactam allergy: a retrospective chart review of drug allergy assessment in a predominantly pediatric population. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2016;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Atanaskovic-Markovic M, Gaeta F, Medjo B, Gavrovic-Jankulovic M, Cirkovic Velickovic T, Tmusic V, et al. Non-immediate hypersensitivity reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics in children—our 10-year experience in allergy work-up. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2016;27:533–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chen JR, Tarver SA, Alvarez KS, Tran T, Khan DA. A proactive approach to penicillin allergy testing in hospitalized patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2016;5:686–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chiriac AM, Rerkpattanapipat T, Bousquet PJ, Molinari N, Demoly P. Optimal step doses for drug provocation tests to prove beta-lactam hypersensitivity. Allergy 2016;72:552–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.King EA, Challa S, Curtin P, Bielory L. Penicillin skin testing in hospitalized patients with beta-lactam allergies: effect on antibiotic selection and cost. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2016;117:67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mill C, Primeau MN, Medoff E, Lejtenyi C, O’Keefe A, Netchiporouk E, et al. Assessing the diagnostic properties of a graded oral provocation challenge for the diagnosis of immediate and nonimmediate reactions to amoxicillin in children. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:e160033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Manuyakorn W, Singvijarn P, Benjaponpitak S, Kamchaisatian W, Rerkpattanapipat T, Sasisakulporn C, et al. Skin testing with β-lactam antibiotics for diagnosis of b-lactam hypersensitivity in children. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 2016;34: 242–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Moreno E, Laffond E, Munoz-Bellido F, Gracia MT, Macias E, Moreno A, et al. Performance in real life of the European Network on Drug Allergy algorithm in immediate reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics. Allergy 2016;71:1787–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mota I, Gaspar A, Chambel M, Piedade S, Morais-Almeida M. Hypersensitivity to beta-lactam antibiotics: a three-year study. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;48:212–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ratzon R, Reshef A, Efrati O, Deutch M, Forschmidt R, Cukierman-Yaffe T, et al. Impact of an extended challenge on the effectiveness of β-lactam hypersensitivity investigation. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2016;116:329–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Faitelson Y, Boaz M, Dalal I. Asthma, family history of drug allergy, and age predict amoxicillin allergy in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017;6: 1363–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Fazlollahi MR, Bidad K, Shokouhi R, Dashti R, Nabavi M, Movahedi M, et al. Frequency and risk factors of penicillin and amoxicillin allergy in suspected patients with drug allergy. Arch Iran Med 2017;20:34–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Juri MC, Romero DSF, Larrauri B, Malbran E, Torre G, Malbran A. Allergy to drugs: experience in 771 procedures. Medicina-Buenos Aires 2017; 77:180–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Marwood J, Aguirrebarrena G, Kerr S, Welch SA, Rimmer J. De-labelling self-reported penicillin allergy within the emergency department through the use of skin tests and oral drug provocation testing. Emerg Med Australas 2017;29: 509–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.McDanel DL, Azar AE, Dowden AM, Murray-Bainer S, Noiseux NO, Willenborg M, et al. Screening for beta-lactam allergy in joint arthroplasty patients to improve surgical prophylaxis practice. J Arthroplast 2017;32:S101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Misirlioglu ED, Guvenir H, Toyran M, Vezir E, Capanoglu M, Civelek E, et al. Frequency of selective immediate responders to aminopenicillins and cephalosporins in Turkish children. Allergy Asthma Proc 2017;38:376–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ramsey A, Staicu ML. Use of a penicillin allergy screening algorithm and penicillin skin testing for transitioning hospitalized patients to first-line antibiotic therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017;6:1349–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Soria A, Autegarden E, Amsler E, Gaouar H, Vial A, Francès C, et al. A clinical decision-making algorithm for penicillin allergy. Ann Med 2017;49: 710–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sundquist BK, Bowen BJ, Otabor U, Celestin J, Sorum PC. Proactive penicillin allergy testing in primary care patients labeled as allergic: outcomes and barriers. Postgrad Med 2017;129:915–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Vyles D, Adams J, Chiu A, Simpson P, Nimmer M, Brousseau DC. Allergy testing in children with low-risk penicillin allergy symptoms. Pediatr 2017;140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Marraccini P, Pignatti P, Alcamo ADA, Salimbeni R, Consonni D. Basophil activation test application in drug hypersensitivity diagnosis: an empirical approach. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2018;177:160–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Moussa Y, Shuster J, Matte G, Sullivan A, Goldstein RH, Cunningham D, et al.De-labeling of beta-lactam allergy reduces intraoperative time and optimizes choice in antibiotic prophylaxis [published online ahead of print May 8, 2018]. Surgery. 10.1016/j.surg.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sedlackova L, Prucha M, Polakova I, Mikova B. Evaluation of IFN-gamma Enzyme-linked Immunospot Assay (ELISPOT) as a first-line test in the diagnosis of non-immediate hypersensitivity to amoxicillin and penicillin. Prague Med Rep 2018;119:30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Chiriac AM, Vasconcelos MJ, Izquierdo L, Ferrando L, Nahas O, Demoly P. To challenge or not to challenge: literature data on the positive predictive value of skin tests to beta-lactams. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:2404–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Chiriac AM, Banerji A, Gruchalla RS, Thong BYH, Wickner P, Mertes PM, et al. Controversies in drug allergy: drug allergy pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:46–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Blanca M, Romano A, Torres MJ, Fernandez J, Mayorga C, Rodriguez J, et al. Update on the evaluation of hypersensitivity reactions to betalactams. Allergy 2009;64:183–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Torres MJ, Celik GE, Whitaker P, Atanaskovic-Markovic M, Barbaud A, Bircher A, et al. A EAACI drug allergy interest group survey on how European allergy specialists deal with beta-lactam allergy. Allergy 2019;74:1052–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sousa-Pinto B, Blumenthal KG, Macy E, Bavbek S, Benic MS, Alves-Correia M, et al. Diagnostic testing for penicillin allergy: a survey of practices and cost perceptions. Allergy 2020;75:436–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Iammatteo M, Alvarez Arango S, Ferastraoaru D, Akbar N, Lee AY, Cohen HW, et al. Safety and outcomes of oral graded challenges to amoxicillin without prior skin testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:236–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Macy E, Vyles D. Who needs penicillin allergy testing? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018;121:523–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.