Introduction

The approbation of vaccines against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) raises the hope of a pandemic control. Vaccination of intensive care unit (ICU) healthcare workers (HCWs) is of first importance since this personnel is at risk of exposure, can endanger fragile patients, is essential for maintaining healthcare system capacity and their vaccination may set an example for the general population. However, vaccine hesitancy (VH), one of the 2019 top ten global health threats according to the World Health Organization, defined as delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services, does not spare HCWs [1]. We hypothesised that in the context of new generation platforms vaccines approbation and of misinformation sharing related to COVID-19 pandemic, with a previously identified risk of VH [2], non-medical HCWs (NM-HCWs) would show the same low vaccine acceptance rate that the general population (i.e., around 60% [3]) and that an information session would improve the willingness to be vaccinated. Our objectives were to evaluate ICU NM-HCWs willingness to be vaccinated with already approved COVID-19 vaccines and the impact of an information session on this attitude.

Methods

According to the French law [4], ethical approval for this study was obtained from the French Ethics Committee for Research in Anaesthesia and Critical Care (IRB 00010254-2021-015) and every participant gave his informed consent. In February 2021, after European marketing authorisation of two mRNA and one viral vector-based vaccine and before vaccination extension to less than 50-year-old French HCWs without comorbidities, an information session was proposed to NM-HCWs of four ICUs. It was a 45-minute lasting session delivered by intensivists based on literature reviews and guidelines issued from learned societies and health authorities. The meeting was divided into three parts: 1st part exposing in a succinct manner basics in cellular and molecular biology, virology and vaccinology including data related to available COVID-19 vaccines; 2nd part introducing the phenomenon of VH along with its main determinants; 3rd part was a question and answer session. Sessions were delivered directly in the units in order to increase the participation rate and were not pre-recorded videos in order to favour interactions with participants. Before and after the session, the participants were asked to answer a questionnaire. Categorical variables were reported as count and proportions, and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation. Non-parametric tests were performed for categorical (Fisher exact test) and continuous variables (Mann–Whitney). McNemar's test was used to compare acceptance rate before and after the session. Statistical significance was considered as p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using Statistica 9.0 (Statsoft®).

Results

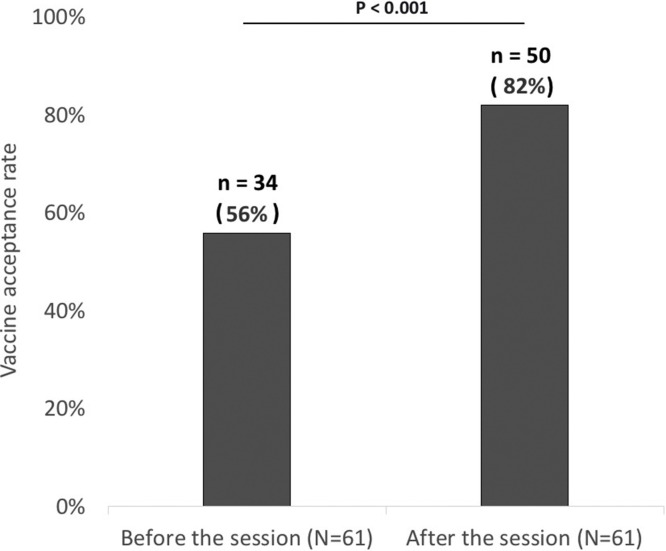

Out of 84 NM-HCWs working during the study period, 61 filled out the questionnaire (participation rate of 73%) (Table 1 ). Main sources of information about COVID-19 vaccines were other healthcare workers (n = 46, 75%) and televisual media (n = 41, 67%). Health authorities approved COVID-19 vaccines were seen as effective by 36 (59%) participants, ineffective by 6 (10%) and 19 (31%) did not know if the vaccines were effective or not. The estimated rate for serious adverse events associated with COVID-19 vaccines was 22 ± 21%. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate was 56% (n = 34) before the session and significantly increased to 82% (n = 50) after the session (P < 0.001, Fig. 1 ). Information delivered during the session was perceived as understandable and relevant for respectively 61 (100%) and 59 (98%) participants and all of them recommended the session to other NM-HCWs.

Table 1.

Characteristics of ICU non-medical healthcare workers and impact of the vaccine information session (values are count and proportion for categorical variables and mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables).

| Characteristics | Total (N = 61) | Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine before the session (N = 34) | Refusal of COVID-19 vaccine before the session (N = 27) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Age (years), m ± s | 37 ± 7 | 37 ± 7 | 38 ± 7 | 0.37 |

| Female, n (%) | 52 (85%) | 28 (82%) | 24 (89%) | 0.73 | |

| Professional characteristics | Nurses, n (%) | 38 (62%) | 23 (68%) | 15 (56%) | 0.33 |

| Nursing Assistants, n (%) | 23 (38%) | 11 (32%) | 12 (44%) | 0.33 | |

| Surgical Intensive Care Unit non-medical healthcare workers, n (%) | 19 (31%) | 13 (38%) | 6 (22%) | 0.18 | |

| Medical Intensive Care Unit non-medical healthcare workers, n (%) | 17 (28%) | 5 (19%) | 12 (35%) | 0.15 | |

| Cardiac Intensive Care Unit non-medical healthcare workers, n (%) | 13 (21%) | 3 (9%) | 10 (37%) | 0.01 | |

| Neurosurgical Intensive Care Unit non-medical healthcare workers, n (%) | 12 (19%) | 6 (18%) | 6 (22%) | 0.66 | |

| Information sources about COVID-19 vaccines | Other healthcare workers, n (%) | 46 (75%) | 25 (74%) | 21 (78%) | 0.93 |

| Televisual Media, n (%) | 41 (67%) | 23 (68%) | 18 (67%) | 0.94 | |

| Friends, n (%) | 21 (34%) | 10 (29%) | 11 (41%) | 0.35 | |

| Relatives, n (%) | 14 (23%) | 7 (20%) | 7 (26%) | 0.62 | |

| Institutional communication, n (%) | 12 (20%) | 8 (24%) | 4 (15%) | 0.52 | |

| Personal research on the internet, n (%) | 9 (15%) | 3 (9%) | 6 (22%) | 0.27 | |

| Attending physician, n (%) | 9 (14%) | 5 (15%) | 4 (15%) | 1 | |

| Social Networks, n (%) | 8 (13%) | 4 (12%) | 4 (15%) | 1 | |

| Radio Media, n (%) | 6 (10%) | 3 (9%) | 3 (11%) | 1 | |

| Health authorities, n (%) | 5 (8%) | 1 (3%) | 4 (15%) | 0.22 | |

| Occupational physician, n (%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (4%) | 1 | |

| Learned societies, n (%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 1 | |

| Biomedical search engine, n (%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 | |

| Benefit/risk balance | COVID-19 vaccines perceived as effective, n (%) | 36 (59%) | 23 (68%) | 13 (48%) | 0.19 |

| Estimated risk of serious adverse event associated with COVID-19 vaccines, m ± s | 22% ± 21% | 16% ± 16% | 29% ± 24% | 0.07 | |

| Evaluation of the information session | Information delivered during the session perceived as understandable, n (%) | 61 (100%) | 34 (100%) | 27 (100%) | 1 |

| Information delivered during the session perceived as relevant, n (%) | 59 (98%) | 33 (97%) | 26 (100%) | 1 | |

| Recommend the information session to other healthcare workers, n (%) | 60 (100%) | 34 (100%) | 26 (100%) | 1 | |

| Impact of the information session | Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine before the information session | 34 (56%) | 34 (100%) | 0 (0%) | < 0.01 |

| Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine after the information session | 50 (82%) | 34 (100%) | 16 (59%) | < 0.01 | |

Fig. 1.

Impact of the vaccine information session on the vaccine acceptance rate among ICU non-medical healthcare workers.

Discussion

While a worldwide race is launched in order to extend vaccination, the low vaccine acceptance rate among ICU NM-HCWs before any intervention emphasises the fact that vaccines availability is not the only issue. NM-HCWs’ perception of the benefit-risk balance seems to be biased with an underestimation of vaccines efficacy and an overestimation of their risks by at least a factor of 100. By delivering objective data issued from reliable sources and enabling exchanges about COVID-19 vaccines concerns, an information session delivered by intensivists seems to be effective in increasing the ICU NM-HCWs’ vaccine acceptance rate. Our observation calls for an urgent implementation of public health strategies addressing VH combined to the provision of vaccines. It is still time to avoid the repetition of previous vaccination campaigns failures [5].

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

CG : conceived and designed the analysis, wrote the manuscript. AS: collected the data and performed analysis. IG : collected the data and performed analysis. JLH : wrote the manuscript. PV: wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the medical and non-medical staffs from CHU de Caen Normandie who made it possible to set up the vaccine information sessions.

References

- 1.Verger P., Scronias D., Dauby N., Awoenam Adedzi K., Gobert C., Bergeat M. Attitudes of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 vaccination: a survey in France and French-speaking parts of Belgium and Canada, 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2021;26(3):1–8. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.3.2002047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peretti-Watel P., Seror V., Cortaredona S., Launay O., Raude J., Verger P. A future vaccination campaign against COVID-19 at risk of vaccine hesitancy and politicisation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):769–770. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30426-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazarus J.V., Ratzan S.C., Palayew A., Gostin L.O., Larson H.J., Rabin K. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toulouse E., Lafont B., Granier S., Mcgurk G., Bazin J.-E. French legal approach to patient consent in clinical research. Anaesthesia Crit care pain Med [Internet] 2020;39(6):883–885. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2020.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blasi F., Aliberti S., Mantero M., Centanni S. Compliance with anti-H1N1 vaccine among healthcare workers and general population. Clin Microbiol Infect [Internet] 2012;18(Suppl. 5):37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.