Abstract

In this paper, a study is conducted to explore the ability of deep learning in recognizing pulmonary diseases from electronically recorded lung sounds. The selected data-set included a total of 103 patients obtained from locally recorded stethoscope lung sounds acquired at King Abdullah University Hospital, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Jordan. In addition, 110 patients data were added to the data-set from the Int. Conf. on Biomedical Health Informatics publicly available challenge database. Initially, all signals were checked to have a sampling frequency of 4 kHz and segmented into 5 s segments. Then, several preprocessing steps were undertaken to ensure smoother and less noisy signals. These steps included wavelet smoothing, displacement artifact removal, and z-score normalization. The deep learning network architecture consisted of two stages; convolutional neural networks and bidirectional long short-term memory units. The training of the model was evaluated based on a k-fold cross-validation scheme of tenfolds using several performance evaluation metrics including Cohen’s kappa, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F1-score. The developed algorithm achieved the highest average accuracy of 99.62% with a precision of 98.85% in classifying patients based on the pulmonary disease types using CNN + BDLSTM. Furthermore, a total agreement of 98.26% was obtained between the predictions and original classes within the training scheme. This study paves the way towards implementing deep learning models in clinical settings to assist clinicians in decision making related to the recognition of pulmonary diseases.

Supplementary Information

The online version supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12652-021-03184-y.

Keywords: Lung sounds, Pulmonary diseases, Deep learning, Stethoscope, Convolutional neural network, Long short-term memory

Introduction

Pulmonary auscultation is one of the oldest techniques used in the diagnosis of the respiratory system. It is considered as a safe, non-invasive, and cost-effective clinical method to monitor the overall condition of the lungs and surrounding respiratory organs (Bardou et al. 2018; Andrès et al. 2018). Through a stethoscope, the sound of air moving inside and outside the lungs during breathing can be auscultated through chest walls allowing a physiotherapist to identify any pulmonary diseases such as asthma, pneumonia, or bronchiectasis (BRON) (Andrès et al. 2018; Pramono et al. 2019). According to the world health organization (WHO) report in 2017 (World Health Organization 2017a), more than 235 million people are suffering from asthma worldwide. In addition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is expected to be the third leading cause of death by 2030 (World Health Organization 2017b).

Lung sounds are either normal or abnormal. An abnormality in the auscultated sound usually indicates an inflammation, infection, obstruction, or fluid in the lungs. There are several types of abnormal (adventitious) lung sounds that superimpose normal sounds including wheezes, stridor, rhonchi, and crackles (Sarkar et al. 2015; Andrès et al. 2018). Wheezes are considered as high-pitch continuous waves of more than 400 Hz lasting for more than 80 ms and sounding like a breathing whistle. These sounds are due to an inflammation/narrowing of the bronchial tubes (Pramono et al. 2019). Similarly, stridor sounds are high-pitched waves of more than 500 Hz lasting for over 250 ms. They usually originate due to laryngeal or tracheal stenosis (Pasterkamp et al. 1997). Rhonchi are low-pitch continuous waves of sounds similar to snoring with frequencies less than 200 Hz. They usually arise from fluid or mucus filling up the bronchial tubes (Sovijarvi et al. 2000). Crackles are discontinuous clicking or rattling sounds of either fine (short duration) or coarse (long duration). These sounds are an indication of pneumonia or heart failure (Reichert et al. 2008). Other respiratory sounds include coughing, snoring, and squawking.

In general, lung sounds are acoustic signals with frequencies ranging between 100 Hz and 2 kHz (Gross et al. 2000). However, the human ear is sensitive to waves of 20 Hz to 20 kHz (Rosen and Howell 2011). Using the traditional manual stethoscope, many diseases could be misdiagnosed or go undetected due to inability of hearing its corresponding respiratory sounds. Thus, the auscultation process loses important information, carried by lower frequency waves, about the condition of respiratory organs. In addition, the diagnosis of pulmonary diseases is usually affected by the quality of the tool, physician experience, and surrounding environment (Shi et al. 2019). Therefore, electronic stethoscope has been gradually arising as a replacement to traditional diagnosis tools. It has the ability to store lung sounds as signals within a computer; allowing medical doctors to investigate these signals in time-frequency analysis with a better interpretation (Shi et al. 2019; Gurung et al. 2011). Furthermore, recent advances in signal processing and artificial intelligence assist clinicians in decision making when diagnosing respiratory diseases through lung sounds.

Numerous studies have covered the use of machine/deep learning algorithms in automatic respiratory diseases identification and lung sounds classification. In machine learning, many models have been utilized including support vector machines (SVMs) (Jin et al. 2014), k-nearest neighbors (KNNs) (Serbes et al. 2013), naive Bayes classifier (Naves et al. 2016), and artificial neural networks (ANNs) (Orjuela-Cañón et al. 2014). However, despite achieving high levels of performance, these methods require additional feature extraction step for features such as time domain, time-frequency domain (Chen et al. 2019), hilbert-huang transform (HHT) (Serbes et al. 2013), melFrequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) (Bahoura 2009), wavelet transform coefficients (Kahya et al. 2006; Orjuela-Cañón et al. 2014), and higher order statistics (HOS) (Naves et al. 2016). Recently, deep learning algorithms have arisen without the need of any prior feature extraction procedures. These methods reduced the human error caused by conventional algorithms, which may be due to patient-specific details and other data variations from patient to patient. In addition, deep learning outperformed these methods in disease identification and lung sounds classification (Jayalakshmy and Sudha 2020; Demir et al. 2020). In Aykanat et al. (2017) and Bardou et al. (2018), researchers utilized convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to classify respiratory sounds, where it has been shown that the highest accuracy was achieved using the CNN model versus typical machine learning models (i.e., SVM and KNN). Furthermore, in Messner et al. (2020), authors designed a convolutional recurrent neural network (RNN) utilizing long short-term memory (LSTM) cells for multi-channel lung sounds classification achieving high levels of accuracy. Additionally, the combination of CNN and RNN into one model have been investigated in several studies and for various applications (Xuan et al. 2019; Passricha and Aggarwal 2019; Dubey et al. 2019).

Our contribution

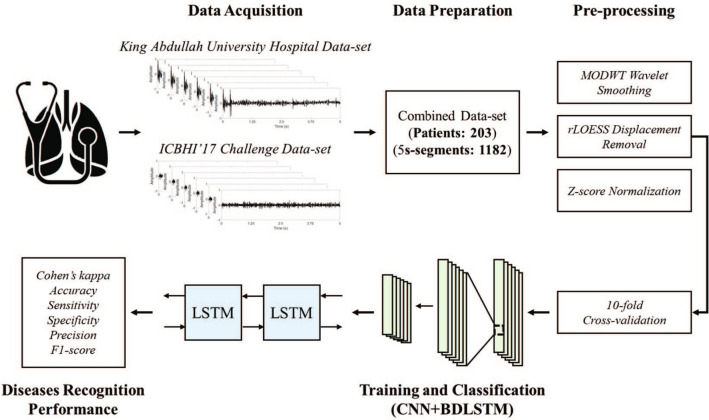

In this paper, a study is conducted to investigate the ability of deep learning, illustrated by deep convolutional neural networks and long short-term memory units, in recognizing multiple pulmonary diseases from lung sounds signals (Fig. 1). The signals were obtained from recordings of electronic stethoscopes at a local hospital in Irbid, Jordan, in combination with a publicly available data-set. The recordings represent signals from patients suffering from asthma, pneumonia, BRON, COPD, and heart failure (HF) along with control (normal) patients. Each signal goes initially into a preprocessing procedure to ensure the best possible input to the deep learning network. The preprocessing steps include wavelet smoothing, displacement removal, and normalization. A CNN and bidirectional LSTM network (CNN + BDLSTM) was designed for the training and classification processes to extract information from both spatial and temporal domains of the signals. The training followed a tenfold cross-validation scheme to allow the maximum possible amount of data within the training model and to cover the whole data-set in the prediction process. Several evaluation metrics were used to evaluate the recognition of diseases using CNN and LSTM networks individually as well as a combination of both networks.

Fig. 1.

The complete procedure followed in the proposed study

The main contribution of this work is the implementation of a BDLSTM network in addition to the normal CNN feature extraction approach. This adds to the learning efficiency of the network by extracting time-domain features from signals. To the best of our knowledge, deep learning models for the purpose of lung sounds classification have been designed usually using a single neural network approach. Therefore, along with the proposed combined model (CNN + BDLSTM), the disease recognition ability was tested for the network when operating individually as either CNN or BDLSTM. Furthermore, the majority of studies in the literature have implemented the use of signals spectrograms as 2-dimensional (2D) images, which increases the load on the system during the training and classification processes of the model. In contrast, the proposed study utilizes 1-dimensional (1D) signals with only a small portion (5 s) of the lung sounds recordings. Furthermore, a novel stethoscope-based lung sound data-set was collected locally. This allowed for the inclusion of more types of pulmonary diseases including asthma and HF and provided a better analysis of the performance of the deep learning models over a wider range of lung sound characteristics. It is worth noting that this work does not implement any data augmentation techniques that are considered less preferable in clinical studies. In contrast, the locally recorded data-set was used to balance the classes along with a weight-modified classification layer at the end of the trained model. Unlike the majority of previous studies, where features are manually extracted or the model are built with large neural networks, the proposed study was developed to ensure high levels of performance while at the same time be as simple as possible for the use in clinical settings. The developed model accepts data as small lung sounds signals (5 s), which does not require considerable memory or computational overhead.

Material and methods

Subjects

The selected signals were acquired from locally recorded lung sounds in addition to a publicly available data-set. The decision to combine two data-sets was to incorporate more patients with lung sounds corresponding to a wider range of respiratory diseases. The detailed demographic information of patients included in both data-sets is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information of the subjects

| Data-set | Category | Normal | Asthma | Pneumonia | BRON | COPD | HF | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local recordings | Number of subjects | 35 (24 M, 11 F) | 32 (15 M, 17 F) | 5 (3 M, 2 F) | 3 (2 M, 1 F) | 9 (8 M, 1 F) | 19 (10 M, 9 F) | 103 (62 M, 41 F) |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 43 ± 20 | 46 ± 16 | 56 ± 10 | 37 ± 27 | 57 ± 10 | 59 ± 19 | 50 ± 17 | |

| Number of recordings | 110 | 88 | 18 | 6 | 23 | 56 | 301 | |

| ICBHI’17 | Number of subjects | 26 (13 M, 13 F) | 1 (1 F) | 6 (3 M, 2 F) | 13 (6 M, 7 F) | 64 (48 M, 16 F) | N/A | 110 (70 M, 39 F) |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 12 ± 20 | 70 | 62 ± 29 | 25 ± 21 | 69 ± 8 | N/A | 48 ± 20 | |

| Number of recordings | 135 | 4 | 148 | 116 | 779 | N/A | 1182 |

SD standard deviation

The first group of signals were acquired locally at King Abdullah University Hospital, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan. The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB: 35/117/218) at King Abdullah University Hospital. In addition, all participants reviewed the procedure of the study and provided a written consent prior to any clinical examinations. The data-set included 103 participants (62 M, 41 F) of all age groups, out of which 35 participants had no respiratory abnormalities (normal), while 68 had pulmonary diseases including asthma, pneumonia, BRON, COPD, and HF. The acquisition protocol of lung sounds was performed by two professional thoracic clinicians. Each participant was asked to maintain a relax in a supine position prior to the recording of their breathing cycle sounds. The sounds were recorded using a single-channel electronic stethoscope (3M Littmann model 3200) placed on either upper, middle, or lower left/right chest wall locations. The electronic device provides a built-in ambient and fractional reduction technology, however, few recordings had slight movement artifacts. All signals were sampled with a sampling frequency of 4 kHz and band-limited to a frequency range of 20 Hz to 2 kHz.

The second group of signals were obtained from the publicly available 2017 Int. Conf. on Biomedical Health Informatics (ICBHI’17) challenge online database Rocha et al. (2017). The data-set includes lung sounds recorded by the School of Health Sciences, University of Aveiro (ESSUA) research team at the Respiratory Research and Rehabilitation Laboratory (Lab3R), ESSUA and at Hospital Infante D. Pedro, Aveiro, Portugal. In addition, another team from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTH) and the University of Coimbra (UC) acquired respiratory sounds at the Papanikolaou General Hospital, Thessaloniki, the General Hospital of Imathia (Health Unit of Naousa), Greece, and the General Hospital of Imathia (Health Unit of Naousa), Greece. The data-set covered 126 subject with various types of respiratory diseases including pneumonia, BRON, and COPD. Each patient recorded lung sounds for duration varying between 10 and 90 s, and all signals were re-sampled at a sampling frequency of 4 kHz.

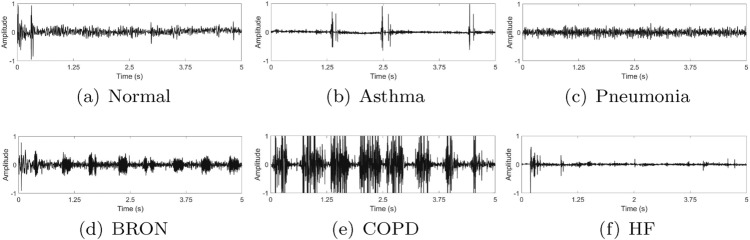

In this study, only 110 patients were selected from the ICBHI’17 data-set. The selection of these patients was to compliment the locally recorded data-set described earlier. In addition, it is worth noting that each recording from both data-sets included only 5 s to maintain a complete respiratory cycle. No further data segmentation was applied on the recordings of both data-sets. The normal breathing range in adults is 12–18 breaths per minute (Barrett et al. 2016), therefore, a single respiratory cycle (inspiration and expiration) for the slower breathing scenario takes 5 s, while the faster breathing scenario lasts up to 2 s (Lapi et al. 2014; Nuckowska et al. 2019). Thus, a segment of 5 s ensures coverage of both breathing rates without adding additional signal data per patient that may cause extra complexity for the model. This approach has been widely applied in literature (Zhang et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2016). Figure 2 shows examples of the 5 s segmented recordings corresponding to normal subjects and patients with respiratory diseases.

Fig. 2.

Examples of lung sound signals coming from normal and five types of respiratory diseases patients: a normal, b asthma, c pneumonia, d BRON, e COPD, f HF

Preprocessing

As in any other electronically recorded biological signal, lung sound recordings are disturbed by acoustic noise caused by ambient noise, background talking, electronic interference, or any displacement of the stethoscope (Emmanouilidou and Elhilal 2013). Therefore, it is of a high importance to ensure that the signals are smoothed and pre-processed prior to any feature extraction procedure. Several preprocessing steps were followed in the current study including:

1D wavelet smoothing

Displacement artifact removal

z-score normalization

The following subsections provide a brief description of each preprocessing step.

1D wavelet smoothing

Wavelet transform (WT) has been widely used for the analysis of non-stationary signals. In comparison to Fourier transform (FT), the signal is decomposed into a group of wavelets instead of complex sinusoids. The basic idea behind WT is the use of a mother wavelet () to translate and dilate a signal into different functions (Martínez et al. 2004). Mathematically, the mother wavelet is described as:

| 1 |

where t corresponds to the time instance, a is the dilation function, and b is the translation function.

WT is either continuous or discrete. In continuous wavelet transform (CWT), the dilation and translation functions operate on the signal continuously, which increases the computational complexity. On the other hand, the discrete wavelet transform (DWT) operates with wavelets discretely sampled preserving both the frequency and the location information in time (Saxena et al. 2002). Therefore, it is more efficient to analyze signals using DWT as opposed to the CWT.

In DWT, the most commonly used orthonormal wavelets are wavelets from the family of Daubechies (db). Beside the selection of a mother wavelet to decompose a signal, the thresholding function as well as the level of decomposition have to be known. A famous 1-dimensional (1D) DWT function is the maximal overlap discrete wavelet transform (MODWT) (Chandra et al. 2018; Cornish et al. 2006). This function is superior to basic DWT in implementing a highly redundant DWTs that keeps down-sampling values at each decomposition level. The basic definition of MODWT is the use of a pair of high-pass and low-pass filters to decompose an infinite sequence as:

| 2 |

| 3 |

where is the wavelet coefficient, is the scaling coefficient, and are the high-pass and low-pass filters, respectively, is the infinite sequence, and k is the level of decomposition. A detailed explanation of the MODWT implementation is given in Cornish et al. (2006).

In this work, the DWT was selected to follow a soft MODWT of level 4 with a db5 mother wavelet. The smoothing was followed using MATLAB R2020a signal processing toolbox and function (wden()).

Displacement artifact removal

Any displacement of the electronic stethoscope causes a wave-shaped low-frequency signal on top of the useful signal. Therefore, it is essential to ensure that the signals are not contaminating any of these shapes within its structure (Zheng et al. 2020a). To achieve this, a local polynomial regression smoother (LOESS) function was utilized for its fast and high performance in removing such effects. In LOESS, the signal is fitted with a weighted least-squares function, where the closer the points to the fitted line the higher the weights and visa-versa. The function is given as:

| 4 |

where d is the distance of each point to the fitted curve scaled to be between 0 and 1. Furthermore, a robust version of the algorithm (rLOESS) allows to set a zero weight to the points outside the sixth mean of absolute deviation. A complete mathematical explanation of these two methods can be found in Cleveland (1979).

Z-score normalization

After the aforementioned signal preprocessing steps, it is essential to ensure that each signal is z-score normalized. In z-score normalization, the signal in time domain will no longer have a wide dynamic ranges between its corresponding values. In other word, no larger trends in the signal that dominate the smaller ones (Zhang et al. 2017; Yannick et al. 2019). Therefore, the signal exhibit a mean value () of 0 and a standard deviation () of 1 as follows:

| 5 |

Having a clear signal with no trend variations across time maintains a better performance in deep learning algorithms (Yannick et al. 2019).

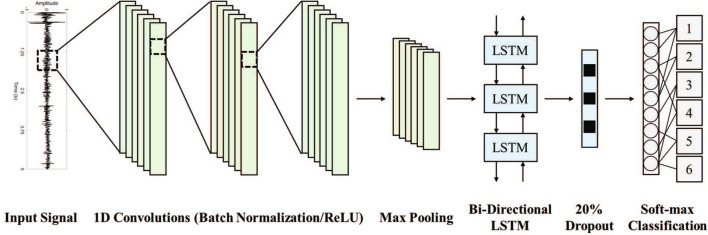

Training and classification

The selected model for training and classification is a combination of 1D convolutional neural network and bidirectional long short-term memory (CNN + BDLSTM). CNN allows to extract features regarding the overall spatial dimensionality of the signal. On the other hand, LSTM captures the features according to the variations in time-domain. By combining both networks, a better performance is usually achieved in training a model to predict signals based on their spatial and time-domain characteristics (Zheng et al. 2020b). Furthermore, the performance of the model was evaluated for the combined network as well as when operating individually as CNN or BDLSTM. The following subsections describe each network layers prior to the training process (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Convolutional neural network and bidirectional long short-term memory (CNN + BDLSTM) model architecture

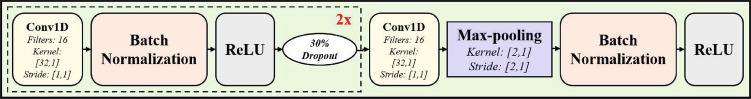

1D CNN architecture

CNN is one of the most commonly used artificial neural networks for the process of feature extraction and classification. It is considered as a feed-forward network with transnational and rotational invariance to analyze visual imagery (Radzi and Khalil-Hani 2011; Schmidhuber 2015). In a CNN, multiple number of dot products (convolutions) is applied to a signal , where N is the total number of points, as per the following equation:

| 6 |

where u is the layer index, is the activation function, is the bias of the jth feature map, M is the kernel size, is the weight of the feature map and filter index mth.

The architecture of the CNN developed herein (Fig. 4) included a set of 1D convolutional, batch normalization (BN), rectified linear unit (ReLU), and max pooling layers. Initially, a 1D input layer was used to accept input data of dimensionality of [20,000,1] to the network. Then, a set of three 1D convolutional layers (Conv1D) were used each with a kernel size of [32,1], total filters of 16, and stride of [1,1]. Each Conv1D layer was followed by a BN layer and a ReLU except for the last Conv1D layer where it was followed first by a max-pooling layer. The BN layer guarantees normalized inputs across the filters on each mini-batch during training, whereas the ReLU set a threshold to replace negative values with zero. Furthermore, 30 dropout was added after the first two ReLU layers to prevent over-fitting of the model. The max-pooling layer was designed with a kernel size [2,1] and stride of [2,1] to reduce the dimensionality of the extract features and as well as the computational complexity. The network was implemented using MATLAB R2020a deep learning toolbox.

Fig. 4.

The structure of the convolutional neural network (CNN) designed in the proposed study

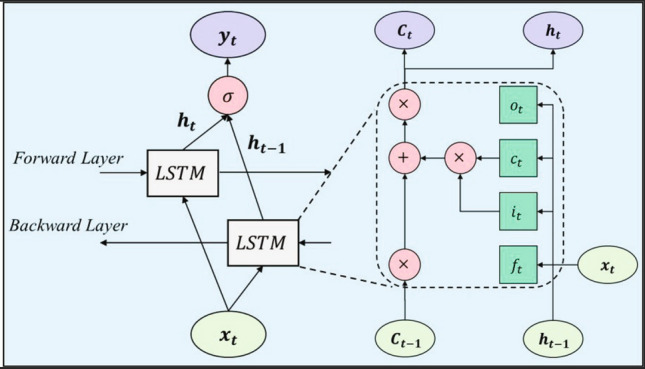

LSTM units

LSTM is a kind of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) that is structured around a main functioning cell. The cell is connected by three units, namely input (i), output o, and forget f gates. The cell is responsible of managing temporal information flow within the network, while the gates control the flow of information inside and outside the whole unit (Hochreiter and Schmidhuber 1997; Fernandez et al. 2014). An LSTM network could process information in the forward direction (unidirectional) or in both the forward and backward directions (bidirectional) as shown in Fig. 5. The latter is most commonly used for signal analysis where time is considered a critical factor in the learning process.

Fig. 5.

The structure of the bidirectional long short-term memory (BDLSTM) designed in the proposed study

Mathematically, the output of the main functioning cell C at any point of time t is given as:

| 7 |

where is the forget gate activation, is the input gate activation, and is the input to the main cell. Usually, the hidden-units activations are selected to be performed across the network based on a sigmoid function given by:

| 8 |

where is the output gate activation. Each gate is defined based on the following equations:

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

| 12 |

where are the input-to-gate weights, are the hidden-to-hidden weights, and are the peephole weights.

To process the information in the forward and backward directions, the bidirectional LSTM output is defined as:

| 13 |

where and are the hidden layers output in the forward and backward directions, respectively, for all N levels of stack.

In this work, a total of 100 hidden-units were utilized within a bidirectional LSTM model. Therefore, a total of 200 units in both directions were utilized during training. At the end of the LSTM network, an additional dropout layer of 20 was added to reduce over-fitting of the model. The network was designed using MATLAB R2020a deep learning toolbox.

Training parameters

The training followed a tenfold cross-validation scheme to ensure coverage of all possible combinations within the data-set. A mini-batch size of 64 was selected with a total number of epochs of 5. The solver was chosen to be based on stochastic gradient descent with momentum (SGDM) optimization (Qian 1999). The initial learning rate was set by default to 0.01 with an L2-regularization of 0.0001.

To handle data imbalance, a weight-modified classification layer was added to the end of the CNN-BDLSTM network. This layer is able of handling the sum of squares error (SSE) loss (Xu et al. 2014; Ali et al. 2015) when data labels are not uniformly distributed or equally split. The weight of each class was determined by the following:

| 14 |

where and are the number of samples per class and in total, respectively.

Performance evaluation

To evaluate the performance of the developed model, several metrics were included in this study to analyze the classification confusion matrix. The confusion matrix was generated sequentially after every fold, and all evaluation metrics were calculated from the overall confusion matrix after the tenfold cross-validation of the training/classification scheme. The first parameter is Cohen’s kappa (Cohen 1960), which is a strong indicator of the degree of agreement between the original labels and predicted ones given as:

| 15 |

where is the observed agreements and is the agreements expected by chance.

Furthermore, the standard evaluation metrics were obtained from the true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN) including the accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F1-score. These metrics are given by:

| 16 |

| 17 |

| 18 |

| 19 |

| 20 |

Results

The preprocessing results are shown in Fig. 6 for only 2.5 s segment for visual purposes. The developed algorithm successfully removes any disturbances attached to the signal due to surrounding noise sources. In addition, the very low frequency, preserving any displacement or movement artifacts, are extracted in part (b). The final signal prior to the training and classification process is shown in part (d) after the z-score normalization of the signal.

Fig. 6.

The preprocessing of a selected lung sound signal (2.5 s segment) showing: a original signal, b MODWT wavelet smoothing, c rLOESS displacement removal, d z-score normalization

Performance of the proposed model

The proposed method was entirely implemented using MATLAB software R2020a (Mathworks, Inc.). The experiments were conducted on an Intel processor (i7-9700) with 32 GBs of RAM. The training process was performed on NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1070 graphics processing unit (GPU) of 8 GBs display memory (VRAM). Each fold was trained for 2 minutes, yielding a total of around 20 minutes to complete the whole training/classification scheme. The prediction of per-patient class took less than a second under the aforementioned machine specifications.

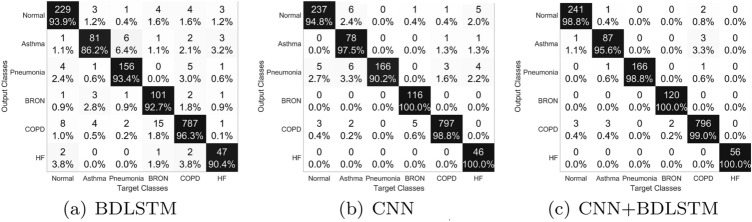

To evaluate the performance of the algorithm, tenfold confusion matrix of the original versus predicted diseases is shown in Fig. 7 for the CNN, BDLSTM, and CNN + BDLSTM neural networks. The highest average precision of the classification process was for the CNN + BDLSTM model with 98.85 split among the classes as 98.80, 95.60, 98.80, 100, 99.00, and 100 for normal, asthma, pneumonia, BRON, COPD, and HF, respectively. The performance of the BDLSTM and CNN when operating separately had an average precision values of 92.15 and 96.88, respectively, which is much less than the performance the combined network.

Fig. 7.

The confusion matrix and per-class precision percentage in respiratory diseases recognition using: a BDLSTM, b CNN, c CNN + BDLSTM

Furthermore, using these confusion matrices, the performance metrics described in Sect. 2.4 were extracted and evaluated. The complete evaluation metrics per class are shown in Table 2. In addition, the table shows the average value of each metric for the three deep learning models. The agreement between the predicted diseases and the original ones reached an average value of 98.26 with an accuracy of 99.62 using the CNN + BDLSTM model. The highest sensitivity values were obtained for the recognition of pneumonia with 93.98 (BDLSTM), 100, and 100 for the three models. In addition, this disease prediction process had specificity values of 99.16, 98.63, and 99.85. It is worth noting that HF had the highest classification performance due to predicting all signals correctly. The classification performance had sensitivity values of 90.06, 93.02, and 98.43 for the BDLSTM, CNN, and CNN + BDLSTM networks, respectively.

Table 2.

Performance comparison, expressed in , of different neural networks (in the order BDLSTM/CNN/CNN + BDLSTM) based on tenfold cross validation

| Condition | Cohen’s kappa () | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | Precision | F1-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 92.41/94.91/98.29 | 97.91/98.58/99.53 | 93.47/96.73/98.37 | 98.79/98.95/99.76 | 93.85/94.80/98.77 | 93.66/95.76/98.57 |

| Asthma | 86.23/90.13/94.76 | 98.38/98.92/99.39 | 88.04/84.78/94.57 | 99.07/99.86/99.71 | 86.17/97.50/95.60 | 87.10/90.70/95.08 |

| Pneumonia | 92.90/94.17/99.33 | 98.58/98.79/99.87 | 93.98/100.00/100.00 | 99.16/98.63/99.85 | 93.41/90.22/98.81 | 93.69/94.86/99.40 |

| BRON | 86.39/97.26/99.10 | 98.04/99.60/99.87 | 82.79/95.08/98.36 | 99.41/100.00/100.00 | 92.66/100.00/100.00 | 87.45/97.48/99.17 |

| COPD | 93.88/97.96/98.10 | 96.97/98.99/99.06 | 98.13/99.38/99.25 | 95.59/98.53/98.83 | 96.33/98.76/99.00 | 97.22/99.07/99.13 |

| HF | 86.55/89.85/100.00 | 99.06/99.33/100.00 | 83.93/82.14/100.00 | 99.65/100.00/100.00 | 90.38/100.00/100.00 | 87.04/90.20/100.00 |

| Overall (average) | 89.73/94.05/98.26 | 98.16/99.04/99.62 | 90.06/93.02/98.43 | 98.61/99.33/99.69 | 92.13/96.88/98.70 | 91.03/94.68/98.56 |

The performance of the proposed CNN + BDLSTM model is reported relative to other state-of-art studies in the literature (Table 3). The summary table covers five most recent studies that implemented deep learning for lung sounds classifications between 2017 and 2020. These studies have used stethoscope recordings from the ICBHI’17 database. Each study has utilized different approaches for processing the recordings, such as signal segmentation and data augmentation. Most of these studies required a preprocessing step of converting the signals into their corresponding spectrogram images as an input to the deep learning model. Models such as SVM, CNN, and VGG and bidirectional gated recurrent unit (VGG-BDGRU) were used in these studies and their performance metrics including the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity are reported accordingly. The proposed approach had the highest levels of accuracy relative to other models. However, it is worth noting that each study implemented different number of recordings for the classification of different number of classes (diseases or lung sounds).

Table 3.

Summary table of recent studies found in literature for the use of machine/deep learning approaches in lung sounds classification

| Study | No. patients | No. recordings | No. classes | Extracted features | Models | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aykanat et al. (2017) | 1630 | 15,328 | 3: Normal. rale, rhonchus | MFCC/spectrograms | SVM/CNN |

Accuracy: 80.00/80.00 Sensitivity: 89.00/79.00 Specificity: N/A |

| Bardou et al. (2018) | 15 | 2141 |

7: Normal, monophonic wheeze polyphonic wheeze, stridor squawk, fine crackle, coarse crackle |

Spectrograms | CNN |

Accuracy: 95.56 Sensitivity: N/A Specificity: N/A |

| Shi et al. (2019) | 384 | 1152 | 3: Normal, asthma, pneumonia | Spectrograms | VGG-BDGRU |

Accuracy: 87.41 Sensitivity: N/A Specificity: N/A |

| Demir et al. (2020) | 126 | 6898 |

4: Normal, crackles, wheezes crackles+wheezes |

Spectrograms | CNN |

Accuracy: 71.15 Sensitivity: 61.00 Specificity: 86.00 |

| García-Ordás et al. (2020) | 126 | 920 |

6: Normal, asthma, pneumonia BRON, COPD, respiratory tract infection |

Spectrograms | CNN |

Accuracy: N/A Sensitivity: 98.81 Specificity: 98.61 |

| This study | 213 | 1,483 |

6: Normal, asthma, pneumonia BRON, COPD. heart failure |

Spatial and temporal (CNN + BDLSTM) |

CNN + BDLSTM |

Accuracy: 99.62 Sensitivity: 98.43 Specificity: 99.69 |

Discussion

In this study, an investigation was carried out on the use of deep learning models, as illustrated by the combination of CNN and BDLSTM neural networks, in identifying pulmonary diseases. The developed model achieved high levels of performance (sensitivity/specificity of 98.43/99.69), which paves the way towards implementing deep learning in clinical settings.

Preparation of lung sounds

As shown in Fig. 6, preprocessing steps ensured the use of an improved version of the lung sound signals within the layers of the training network. In practice, the recorded raw acoustic signal includes several type of unwanted acoustic components such as acoustic noise, displacement noise, cardiac sounds, and background sounds. Thus, the training of deep learning models may be negatively affected by such disturbances of the useful signal. Furthermore, most of studies found in literature implement data augmentation techniques within their proposed approaches as an important preprocessing step. However, this may lead to an unstable model due to the creation of unrealistic signal recordings. In this study, no data augmentation techniques were followed, however, the data-set was balanced by the use of the locally recorded data-set. In addition to balancing the classes within the model, it allowed for the inclusion of a larger set of subjects and disease types.

Analysis of the CNN + BDLSTM network

Instead of only using a single CNN or RNN model as commonly used in the literature, the proposed network architecture guarantees the inclusion of both models into a single structure. Therefore, the spatial representation of the signals, as well as the temporal dynamics, were extracted as feature vectors by the network itself. The CNN filters provided spatial features using convolutional filters, whereas the BDLSTM further extracted temporal features by its memory cells. This has a huge impact when compared to conventional machine learning approaches that require external feature extraction from signals for both spatial and temporal dynamics. The CNN model included three convolutional layers followed by a max pooling layer. The features embedded within each filter were used as inputs to the bidirectional LSTM to learn temporal features in both the forward and backward directions. It has been shown previously that a bidirectional LSTM performs better for time-domain signal classification problems (Graves et al. 2005; Fraiwan and Alkhodari 2020).

The high performance of diseases recognition using the developed deep learning model suggest it as an important tool in clinical settings. As shown in Fig. 7, the detection of BRON as well as HF lung sounds signals was achieved perfectly. This suggest both diseases to have their own signal characteristics in both spatial and temporal representations. Furthermore, it is worth noting that several signals from the COPD patients were misclassified as either normal or asthma. However, the detection error for every disease is low (i.e., ±0.36) as calculated from the standard deviation of the averaged accuracy in Table 2.

To elucidate more on the performance of best performing network (i.e., CNN + BDLSTM), Fig. 8 shows examples from three correctly classified signals and three misclassified signals from the normal, asthma, and pneumonia patients. It can be seen that for the correctly identified signals (a, c, and e), the model was confident in making the decision with probabilities of more than 89. However, for the wrongly classified signals (b, d, and f), the model had probabilities of less than 60 when making the decisions.

Fig. 8.

Examples of three correctly classified signals and three miss-classified signals along with the prediction probabilities using the best performing deep learning model (CNN + BDLSTM)

Furthermore, the type-1/type-2 errors show that COPD was the most misclassified class during the classification process under the best performing network; the CNN + BDLSTM (Fig. 7c). For type-1 errors, it had misclassifications with the normal, asthma, and pneumonia diseases. On the other hand, type-2 error shows that it had misclassifications with the normal, asthma, and BRON diseases. It is worth noting that HF lung sounds had no errors for both types in the classification process.

In addition, previous research works in the literature implemented several data augmentation techniques to ensure a balance in the training process for the model. In contrast, the work presented herein does not follow the same approach, as it is generally not recommended for clinical research to augment signals . Therefore, the addition of a locally recorded data-set along with the weight-modified classification layers ensured a more balanced training process. This led to high levels of accuracy relative to recent state-of-art studies (Table 3), with training data much more reliable for clinical investigation.

Clinical relevance

Clinically, the proposed study ensures accurate recognition of respiratory diseases from lung sounds. Unlike the traditional stethoscope where diseases are diagnosed manually, electronic lung sounds combined with a deep learning predictive model reduce the errors in diseases detection. Therefore, many clinical decisions can be positively affected to prevent any further development of the diseases. Furthermore, although manual diagnosis may lead to correct diagnosis in some circumstances, it is highly recommended clinically to build a model that is able of detecting small variations in signals across patients. Many basic approaches, including threshold levels or feature extraction, have been implemented. However, they may be highly affected by the patient-specific information within the same disease. Thus, a deep learning model that is able of learning from huge number of features automatically could enrich the diagnosis process and act like a supportive decision maker in clinical settings.

Conclusion and future work

In this paper, a deep learning model based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and bidirectional long short-term memory (LSTM) was utilized for the purpose of lung sounds classification. The classification of lung sounds into multiple respiratory diseases using this model had an overall average accuracy of 99.62 with a Cohen’s kappa value of 98.26. This study paves the way towards implementing deep learning trained models in clinical settings to assist clinician in decision making.

Future works will focus on increasing the size of the data-set to include more subjects and a wider range of diseases such as COVID-19. This will improve the credibility of the proposed model. Although, the current proposed classification model achieves high performance metrics, it may be further improved by adjusting both the preprocessing techniques and the training structure.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Jordan University of Science and Technology, Jordan, grant No. 20210047, and the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs (ORSP) Abu Dhabi University’s, UAE.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: MF and LF; Methodology: MF, LF and MA; Dataset preparation and processing: MF and OH; Deep learning model development: MA; Formal analysis and investigation: MF, LF and MA; Writing - original draft preparation: MA; Writing - review and editing: MF and MA; Funding acquisition: MF and LF; Resources: MF and LF; Supervision: MF and LF.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The current study (Ref. 35/117/2018) was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at King Abdullah University Hospital, Deanship of Scientific Research at Jordan University of Science and Technology in Jordan.

Informed consent

Written and signed informed consent was sought and provided prior to the study commencement.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

M. Fraiwan, Email: mafraiwan@just.edu.jo

L. Fraiwan, Email: fraiwan@just.edu.jo

M. Alkhodari, Email: 1045804@students.adu.ac.ae

O. Hassanin, Email: 1052958@students.adu.ac.ae

References

- Ali A, Shamsuddin SM, Ralescu AL, et al. Classification with class imbalance problem: a review. Int J Adv Soft Compu Appl. 2015;7(3):176–204. [Google Scholar]

- Andrès E, Gass R, Charloux A, Brandt C, Hentzler A. Respiratory sound analysis in the era of evidence-based medicine and the world of medicine 2.0. J Med Life. 2018;11(2):89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aykanat M, Kılıç Ö, Kurt B, Saryal S. Classification of lung sounds using convolutional neural networks. EURASIP J Image Video Process. 2017;1:65. doi: 10.1186/s13640-017-0213-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bahoura M. Pattern recognition methods applied to respiratory sounds classification into normal and wheeze classes. Comput Biol Med. 2009;39(9):824–843. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardou D, Zhang K, Ahmad SM. Lung sounds classification using convolutional neural networks. Artif Intell Med. 2018;88:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett KE, Barman SM, Boitano S, Brooks HL et al (2016) Ganong’s review of medical physiology

- Chandra S, Sharma A, Singh GK. Feature extraction of ECG signal. J Med Eng Technol. 2018;42(4):306–316. doi: 10.1080/03091902.2018.1492039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Zhang W, Tian X, Zhang X, Chen S, Lei W (2016) Automatic heart and lung sounds classification using convolutional neural networks. In: 2016 Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA), IEEE, pp 1–4

- Chen H, Yuan X, Pei Z, Li M, Li J. Triple-classification of respiratory sounds using optimized s-transform and deep residual networks. IEEE Access. 2019;7:32845–32852. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2903859. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland WS. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. J Am Stat Assoc. 1979;74(368):829–836. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1979.10481038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Measur. 1960;20(1):37–46. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish CR, Bretherton CS, Percival DB. Maximal overlap wavelet statistical analysis with application to atmospheric turbulence. Bound-Layer Meteorol. 2006;119(2):339–374. doi: 10.1007/s10546-005-9011-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demir F, Ismael AM, Sengur A (2020) Classification of lung sounds with cnn model using parallel pooling structure. IEEE Access

- Dubey K, Agarwal A, Lathe AS, Kumar R, Srivastava V (2019) Self-attention based bilstm-cnn classifier for the prediction of ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. arXiv preprint arXiv:190710370

- Emmanouilidou D, Elhilal M (2013) Characterization of noise contaminations in lung sound recordings. In: 2013 35th annual international conference of the IEEE engineering in medicine and biology society (EMBC), IEEE, pp 2551–2554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fernandez R, Rendel A, Ramabhadran B, Hoory R (2014) Prosody contour prediction with long short-term memory, bi-directional, deep recurrent neural networks. In: INTERSPEECH

- Fraiwan L, Alkhodari M (2020) Investigating the use of uni-directional and bi-directional long short-term memory models for automatic sleep stage scoring. In: Informatics in medicine unlocked, p 100370

- García-Ordás M, Benítez-Andrades J, García-Rodríguez I, Benavides C, Alaiz-Moretón H. Detecting respiratory pathologies using convolutional neural networks and variational autoencoders for unbalancing data. Sensors. 2020;20(4):1214. doi: 10.3390/s20041214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves A, Fernández S, Schmidhuber J (2005) Bidirectional lstm networks for improved phoneme classification and recognition. In: International conference on artificial neural networks, Springer, pp 799–804

- Gross V, Dittmar A, Penzel T, Schuttler F, Von Wichert P. The relationship between normal lung sounds, age, and gender. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(3):905–909. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9905104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung A, Scrafford CG, Tielsch JM, Levine OS, Checkley W. Computerized lung sound analysis as diagnostic aid for the detection of abnormal lung sounds: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Med. 2011;105(9):1396–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter S, Schmidhuber J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997;9(8):1735–1780. doi: 10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayalakshmy S, Sudha GF. Scalogram based prediction model for respiratory disorders using optimized convolutional neural networks. Artif Intell Med. 2020;103:101809. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2020.101809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin F, Sattar F, Goh DY. New approaches for spectro-temporal feature extraction with applications to respiratory sound classification. Neurocomputing. 2014;123:362–371. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2013.07.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahya YP, Yeginer M, Bilgic B (2006) Classifying respiratory sounds with different feature sets. In: 2006 international conference of the IEEE engineering in medicine and biology society, IEEE, pp 2856–2859 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lapi S, Lavorini F, Borgioli G, Calzolai M, Masotti L, Pistolesi M, Fontana GA. Respiratory rate assessments using a dual-accelerometer device. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology. 2014;191:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez JP, Almeida R, Olmos S, Rocha AP, Laguna P. A wavelet-based ecg delineator: evaluation on standard databases. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2004;51(4):570–581. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2003.821031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messner E, Fediuk M, Swatek P, Scheidl S, Smolle-Jüttner FM, Olschewski H, Pernkopf F (2020) Multi-channel lung sound classification with convolutional recurrent neural networks. Comput Biol Med:103831 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Naves R, Barbosa BH, Ferreira DD. Classification of lung sounds using higher-order statistics: a divide-and-conquer approach. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2016;129:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuckowska MK, Gruszecki M, Kot J, Wolf J, Guminski W, Frydrychowski AF, Wtorek J, Narkiewicz K, Winklewski PJ. Impact of slow breathing on the blood pressure and subarachnoid space width oscillations in humans. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42552-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orjuela-Cañón AD, Gómez-Cajas DF, Jiménez-Moreno R (2014) Artificial neural networks for acoustic lung signals classification. In: Iberoamerican congress on pattern recognition, Springer, pp 214–221

- Passricha V, Aggarwal RK (2019) A hybrid of deep cnn and bidirectional lstm for automatic speech recognition. J Intell Syst 1(ahead-of-print)

- Pasterkamp H, Kraman SS, Wodicka GR. Respiratory sounds: advances beyond the stethoscope. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(3):974–987. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.3.9701115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramono RXA, Imtiaz SA, Rodriguez-Villegas E. Evaluation of features for classification of wheezes and normal respiratory sounds. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):0213659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian N. On the momentum term in gradient descent learning algorithms. Neural Netw. 1999;12(1):145–151. doi: 10.1016/S0893-6080(98)00116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radzi SA, Khalil-Hani M (2011) Character recognition of license plate number using convolutional neural network. In: International visual informatics conference, Springer, pp 45–55

- Reichert S, Gass R, Brandt C, Andrès E (2008) Analysis of respiratory sounds: state of the art. Clin Med Circul Respir Pulmon Med 2:CCRPM–S530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rocha B, Filos D, Mendes L, Vogiatzis I, Perantoni E, Kaimakamis E, Natsiavas P, Oliveira A, Jácome C, Marques A, et al. (2017) A respiratory sound database for the development of automated classification. In: International conference on biomedical and health informatics, Springer, pp 33–37

- Rosen S, Howell P. Signals and systems for speech and hearing. Leiden: Brill; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar M, Madabhavi I, Niranjan N, Dogra M. Auscultation of the respiratory system. Ann Thorac Med. 2015;10(3):158. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.160831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Kumar V, Hamde S. Feature extraction from ecg signals using wavelet transforms for disease diagnostics. Int J Syst Sci. 2002;33(13):1073–1085. doi: 10.1080/00207720210167159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidhuber Jürgen. Deep learning in neural networks: an overview. Neural Netw. 2015;61:85–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbes G, Sakar CO, Kahya YP, Aydin N. Pulmonary crackle detection using time-frequency and time-scale analysis. Digital Signal Process. 2013;23(3):1012–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.dsp.2012.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Du K, Zhang C, Ma H, Yan W. Lung sound recognition algorithm based on vggish-bigru. IEEE Access. 2019;7:139438–139449. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2943492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sovijarvi A, Dalmasso F, Vanderschoot J, Malmberg L, Righini G, Stoneman S. Definition of terms for applications of respiratory sounds. Eur Respir Rev. 2000;10(77):597–610. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2017a) Asthma fact sheet. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs307/en/

- World Health Organization (2017b) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (copd) fact sheet. http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd)

- Xu G, Hu BG, Principe JC (2014) An asymmetric stagewise least square loss function for imbalanced classification. In: 2014 International joint conference on neural networks (IJCNN), IEEE, pp 1107–1114

- Xuan P, Ye Y, Zhang T, Zhao L, Sun C. Convolutional neural network and bidirectional long short-term memory-based method for predicting drug-disease associations. Cells. 2019;8(7):705. doi: 10.3390/cells8070705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yannick R, Banville H, Albuquerque I, Gramfort A, Falk T, Faubert J (2019) Deep learning-based electroencephalography analysis: a systematic review. arXiv preprint arXiv:190105498 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang W, Lei W, Xu X, Xing X (2016) Improved music genre classification with convolutional neural networks. In: Interspeech, pp 3304–3308

- Zhang X, Yao L, Zhang D, Wang X, Sheng Q, Gu T (2017) Multi-person brain activity recognition via comprehensive EEG signal analysis. In: Proceedings of the 14th EAI international conference on mobile and ubiquitous systems: computing, networking and services, ACM, pp 28–37

- Zheng J, Zhang J, Danioko S, Yao H, Guo H, Rakovski C. A 12-lead electrocardiogram database for arrhythmia research covering more than 10,000 patients. Sci Data. 2020;7(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41597-020-0386-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Chen Z, Hu F, Zhu J, Tang Q, Liang Y. An automatic diagnosis of arrhythmias using a combination of cnn and lstm technology. Electronics. 2020;9(1):121. doi: 10.3390/electronics9010121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.