Abstract

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a heterogeneous population of immature myeloid cells, which have been characterized for their immunosuppressive capacity through multiple mechanisms. These cells have been extensively studied in the field of tumor immunity. Emerging evidence has highlighted its essential role in maintaining immune tolerance in transplantation and autoimmunity. Because of their robust immune inhibitory activities, there has been growing interest in MDSC-based cellular therapy. Various pre-clinical studies have demonstrated that the adoptive transfer of MDCS represented a promising therapeutic strategy for immune-related disorders. In this review, we summarize relevant studies of MDSC-based cell therapy in transplantation and autoimmune diseases and discuss the challenges and future directions for clinical application of MDSC-based cell therapy.

Keywords: Myeloid-derived suppressor cell, Cellular therapy, Transplantation, Autoimmune disease

1. Introduction of MDSCs and MDSC-based Cell Therapy

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a heterogeneous population of immature myeloid cells with an immuno-inhibitory function that negatively regulates the immune response [1]. Common myeloid precursors give rise to immature myeloid cells (IMCs) that migrate to lymphoid organs where they can differentiate into dendritic cells, macrophages, and neutrophils. By contrast, in pathological conditions, such as cancer, infection, stress, or autoimmune disorders, IMCs become activated and differentiate into MDSCs with an immunosuppressive phenotype[2]. Recent studies also suggested that myeloid suppressor cells can be generated from human peripheral monocytes, but there are debates whether these suppressor cells are MDSCs or monocytes-derived suppressor cells [3–6]. Moreover, modulations of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) differentiation have become an attractive strategies for producing myeloid cells/MDSCs in vitro[7–11].

In mice, MDSCs are defined as CD11b+Gr1+ cells. Based on surface markers and their morphology, MDSCs are further divided into two major groups: monocytic MDSCs (M-MDSCs) and Granulocytic MDSCs (G-MDSCs) [12, 13]. CD11b+Ly6ChiLy6G-MDSCs have a monocytic-like morphology, express nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2), and arginase type 1 (Arg1), have increased T cell suppressive activity, and are identified as M-MDSCs. While, CD11b+Ly6ClowLy6G+ MDSCs have a granulocyte-like morphology, express high levels of ROS, and are identified as G-MDSCs [13, 14]. Human MDSCs are characterized as CD33+/CD11b+/HLA-DR−/low cells that suppress immune response [13]. Similar to the mouse MDSCs, human MDSCs are also divided into two distinct subsets. The use of HLA-DR and CD14 expression is accepted for human M-MDSCs, although it is still controversial for G-MDSCs since granulocytes express low levels of CD14. M-MDSCs are defined as CD33+CD11b+HLA-DR-CD14+CD15− cells while G-MDSCs are defined as CD33+CD11b+CD15+CD66b+ cells [13]. In addition to two major populations of human MDSCs, a third minor population of MDSCs has been discovered, early-stage MDSCs (e-MDSCs), which contain immature progenitor and precursor cells and are characterized as CD33+CD11b+HLA-DR-CD14-CD15− cells [13, 15]. In recent years, several novel markers of MDSCs have been identified. S100A9 has been recognized as new marker for human M-MDSCs[16].The frequency of S100A9-expressing MDSC is correlated with the frequency of M-MDSC, and CD14+ S100A9high MDSC, which express high levels of nitric oxide synthase (NOS2), and are increased in the peripheral blood of patients with colon cancer as compared to healthy donors[16]. Indeed, previous studies have reported that S100A9 inhibits the dendritic cell (DC) differentiation and enhances MDSC production in tumor-bearing mice [17]. S100A8/9 has been shown to activate mouse MDSCs through the NF-kappaB signaling pathway, promoting MDSC migration and accumulation in tumor-bearing mice[18]. Lectin-type oxidized LDL receptor-1(LOX-1), a receptor involved in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and lipid metabolism, is a specific marker of human G-MDSC. It is undetectable in neutrophils in the peripheral blood of healthy donors, but overexpressed in G-MDSCs from cancer patients[19]. Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC), a extracellular matrix (ECM)-associated protein involved in ECM stiffness and composition, has been proposed as a new potential marker of both human and mouse MDSCs. SPARC regulates MDSCs suppressive activity while preventing an excessive inflammatory state via NF-kB signaling pathway[20]. Inhibitor of differentiation 1 (ID1) has been studied as a transcription factor promoting the switching from DCs differentiation to MDSCs expansion during tumor progression in mice[21], further clinical investigation in melanoma patients demonstrated that ID1 expression positively correlated with established other MDSC markers, suggesting that ID1 may be an phenotypic marker for human M-MDSC[22]. The finding of these relatively new makers provides a deeper understanding of MDSC characterization and MDSC-mediated immunosuppression.

The myeloid origin natural-suppressor cells were initially observed in cancer patients in the early 1900s and tumor-bearing mice in the middle of the 1960s. The concept of MDSCs was later introduced to reflect the abnormal nature of those suppressor cells [23]. Its strong suppressive capabilities make them therapeutic targets in cancer. In recent years, there is accumulative evidence that MDSCs are associated with transplantation tolerance and autoimmunity. Enhancing the function of MDSCs or increasing their numbers could be beneficial for treating allogeneic rejection and autoimmune disorders. Ex vivo or in vivo generation of MDSCs for adoptive transfers has been considered as a promising cellular therapy for allograft rejection and autoimmune diseases. In this review, we will summarize recent advances in MDSCs-based cellular therapy in transplantation and autoimmune disease and discuss the potential of MDSCs as a cellular therapy for the prevention of allogeneic graft rejection and autoimmune disorders.

2. MDSCs-based Cellular Therapy in Transplantation

MDSCs participate in the induction of tolerance in the context of transplantation[24–27]. In human allo-HSCT studies, MDSCs have been observed in grafts of G-CSF-mobilized peripheral blood hematopoietic stem cell (PBSCs) and BM cells [28, 29]. The presence of both M-MDSCs and G-MDSCs subsets in grafts has been correlated with a lower incidence of acute GVHD[15, 30, 31]. However, the MDSCs repopulation post allo-HSCT and its clinical relevance has not been fully investigated. Besides allo-HSCT, the tolerogenic role of naturally occurring MDSCs in solid organ transplantation also has been studied. MDSCs can suppress allograft rejection in various transplantation settings thought interaction with other immune cells[24]. For example,, in a murine cardiac transplantation model with TLI/ATS (total lymphoid irradiation/anti-thymocyte globulin/serum) conditioning, depletion of MDSCs using anti-Gr1 Abs abrogated tolerance to combined BM and heart transplants. Mechanistically, MDSC-mediated suppression of alloreactivity is dependent on interaction with NKT cells and IL-4[32]. In kidney transplantation, both clinical and pre-clinal studies have reported that increased number of MDSCs in tolerant kidney graft recipients, and cross-talk between MDSCs and Tregs might be crucial to the MDSCs-mediated immune suppression in the context of kidney transplantation[33–35]. Taken together, manipulation of MDSCs represent a promising approach for the promotion of allograft tolerance in transplantation. Although therapeutic strategies that utilize the induction of native MDSCs have been described, we will mainly focus on the discussion of the current knowledge of MDSCs as cellular therapies in different transplant settings.

2.1. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT)

Allogeneic Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is a potentially curative therapy for a variety of hematologic malignancies and nonmalignant diseases [36]. However, the successful applications of allo-HSCT are hampered by the development of life-threatening graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) [37]. GVHD is characterized by the activation and proliferation of allogeneic antigen reactive (alloreactive) donor T cells that subsequently damage host tissues, such as gastrointestinal (GI)-tract, liver, skin, and lungs [38]. Immunosuppressive regimens for controlling GVHD are associated with an increased incidence of malignancy relapse since they impair the graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) activities [39]. Systemic Immunosuppression is also associated with an increased incidence of infections [40]. Therefore, there are emerging studies on whether immune suppressor cells might be good candidates for preventing GVHD and persevering GVL activities.

In 2005, MacDonald et al. reported a granulocyte-monocyte precursor population that was induced by progenipoietin-1 (a synthetic G-CSF/Flt-3 ligand molecule). Adoptive transfer of those CD11c− Gr1+CD11b+ cells abrogated GVHD while preserved GVL effects. Their study further suggested that those immature cells can promote transplant tolerance by inducing MHC class II-restricted, IL-10-secreting, antigen-specific Tregs [41]. This study showed that the adoptive transfer of myeloid suppressor cells alleviates GVHD. Later, Meorecki et al. [42] demonstrated CpG or CpG combined with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant treatment on donor mice caused an accumulation of double-positive CD11b+Gr-1+ cells in their peripheral blood and spleen. Additionally, those CD11b+ Gr-1+ cells isolated from spleen suppressed alloreactivity in mixed lymphocyte reactions in vitro and effectively prevented GVHD in a murine MHC-haploidentical GVHD model. Using the same GVHD model, Joo et al. described that the administration of G-CSF to B6 mice induced the expansion of immature Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells in peripheral blood and spleen. These cells suppressed alloreactive donor T cells proliferation in vitro and ameliorated acute GVHD through an indoleamine 2.3-dioxygenase (IDO)-independent mechanism. The strong IDO production from those cells was mediated by IFN-γ[43]. D’Avent et al. reported G-CSF–mobilized human CD34+ monocytes repress allogeneic T cell activation by inducing their apoptosis via inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and triggering the generation of Tregs. Those CD34+ monocytes are considered a subtype of M-MDSCs [44].

In the above-mentioned studies, MDSCs were generated in vivo, which limits their large-scale production for adoptive transfer. So, ex vivo cell culture methods have been established to generate a relatively large amount of functional MDSCs from a variety of tissue sources. Zhou et al. [45] from our group developed a three-step in vitro differentiation protocol for MDSCs generated from embryonic stem cells. The mouse embryonic stem cells cultured with a combination of cytokines including IL-3, IL6, stem cell factor (SCF), VEGF, Flt3L, M-CSF, thrombopoietin, and M-CSF induced differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells, gave rise to MDSCs which encompass two homogenous subpopulations: CD115+Ly6C+ or CD115+Ly6C− subtype, and expressed high mRNA levels of iNOS, IL-10, TGF-β, and Arg1 after IFN-γ or IL-13 stimulation. CD115+ MDSCs displayed potent suppressive activity against T-cell proliferation when stimulated either by polyclonal anti-CD3/CD28 or by allogeneic antigens (MLR). Adoptive transfer MDSCs prevented GVHD in a fully MHC-mismatched murine GVHD model. In addition, our group also demonstrated that murine Lin-Sca1+ bone marrow (BM) cells can be differentiated into MDSCs; in fact, 40% to 60% CD115+Ly-6C+ cells were observed after 8-days of culture with the same cytokine cocktails. Those murine BM-derived MDSCs also exhibited strong suppressive capacity in vitro and induced CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells expansion. In another related study, Highfill et al. [46] described a different method for BM-derived MDSC generation. By using naïve C57B/6 mouse donor derived BM cells, CD11b+Ly6GlowLy6C+ MDSCs were generated in 4 days in presence of GM-CSF and G-CSF. These cells also expressed other markers associated with MDSCs, such as IL4Ra (64%), F4/80 (63%), and CD115(43%). Intriguingly, the addition of Th2 cytokine IL-13 at day 3 of culture, generated a subset of MDSCs (MDSC-IL-13) with even stronger immunosuppressive activities. Although the IL-13 did not alter the expression of cell-surface antigens, ARG1 expression was significantly upregulated in MDSC-IL-13 which resulted in a significant increase in suppressor cell function in vitro. MDSC-IL-13 inhibited alloreactive donor T cell proliferation, activation, and pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion. These cells also had potent immune-suppressive activity. Adoptive transfer of MDSCs-IL13 resulted in the inhibition of acute GVHD through the expression of arginase-1 but maintained the GVL activities [46]. Furthermore, the investigators demonstrated MDSCs’ inflammasome activation hampered its suppressive potential, and MDSC-based cellular therapy for preventing GVHD will be more effective when combined with approaches to inhibit MDSC inflammasome activation [47, 48]. In another independent study, Messmann et al. [49] used a similar protocol (G-CSF and GM-CSF) to generate murine BM-derived MDSCs which prevented GVHD by skewing T cells toward type 2 T cells and impaired allogeneic T-cell homing and maintained the GVL activities. Although MDSCs treatment persevered beneficial GVL activities, the underlying mechanism is not well documented. A recent study may provide a potential mechanism, where Zhang et al. from our group reported MDSCs can selectively expand CD8+ memory T cells that play an important role in the retention of GVL activities [50]. Furthermore, the induction of memory T cell populations was associated with MDSCs and CD8 memory T cells was essential for maintaining GVL activities [51].

Murine MDSCs have been successfully applied to GVHD prevention. There are also several studies focused on investigating human MDSCs generation and its therapeutic potential in GVHD. D’Aveni et al. [44] reported that in both humans and mice, G-CSF mobilizes a CD34+ regulatory monocytes population which have potent immunosuppressive activity. In a human to mouse xenogeneic GVHD model, adoptive transfer of those regulatory monocytes (CD34+HLA-DR-CD11b+CD14+CD33+) reduced GVHD symptoms and improved the overall survival as compared to mice grafted without human CD34+ monocytes or with human CD34-DR-monocytes. Furthermore, the investigators validated that CD34+ regulatory monocytes cells negatively correlate with the incidence of acute GVHD in patients. The investigators did not claim that G-CSF-mobilized CD34+ monocytes were human M-MDSCs, but those regulatory monocytes were endowed with immunosuppressive properties and had a similar expression pattern of surface makers to M-MDSCs. Besides CD34+ regulatory monocytes, Wang et al. reported a human MDSC population was expanded by G-CSF mobilization. These e-MDSCs (HLA-HLADR−/lowCD33+CD16−) inhibited the proliferation of autologous donor T cells in a TGF-β-dependent manner, promoted regulatory T cell expansion, and induced Th2 differentiation in vitro. In vivo transplant of those e-MDSCs alleviated acute GVHD in a humanized murine model [15]. These studies demonstrate that MDSCs derived from G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood are potently immunosuppressive and show promise as cell-based treatment for GVHD.

Park et al. [52] explored the ex vivo methods for generating MDSCs from the human cord blood unit (CBU). They examined different cytokine combinations and determined that GM-CSF/SCF could efficiently differentiate and proliferate human MDSCs from a culture of CBU-derived CD34+ cells. They demonstrated that human MDSCs could be expanded on a large scale; up to 100 million MDSCs (HLA-DRlow CD11b+ CD33+) could be produced from 1 unit of CB following 6 weeks of continuous culture. GM-CSF/SCF differentiated MDSCs showed the strongest inhibition of T cell proliferation and the highest expression of iNOS, arginase-1, and IDO compared to the other cytokine combination. The infusion of these MDSCs decreased pro-inflammatory cytokine production while increased the anti-inflammatory cytokine productions, induced Treg cell population which led to ameliorated GVHD symptoms and significantly prolonged the survival in a xenogeneic GVHD model using NSG mice. The limitation of the protocol for CBU-derived MDSCs is the culture period because 6 weeks might be too long to use as a treatment for severe acute GVHD. In 2010, Lechner et al. [5] first established an approach to generate MDSCs from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. GM-CSF+IL-6 induced the differentiation of CD33+ suppressor cells from PBMC culture. Casacuberta-Serra et al. [4] also used a cytokine cocktail to generate MDSCs from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors sorted from apheresis products and monocytes. In 20 days, GM-CSF+IL-6 gave rise to both M-MDSCs and G-MDSCs in hematopoietic progenitor cells. M-MDSCs were obtained with GM-CSF+IL-6 or GM-CSF+TGF-β1 in monocytes culture for 6 days. In both studies, MDSCs from progenitor cells or monocytes exhibited immunosuppressive activity in vitro, but in vivo function of those cells had not been tested. In a related study, Janikashvili et al. [3] used a similar protocol to generate monocyte-derived suppressor cells ex vivo. Those suppressor cells were differentiated from peripheral monocyte after 7 days of culture with a low dose of GM-CSF and IL-6. Interestingly, using the same cytokines combination (GM-CSF and IL6), Janikashvili et al. named those cells monocyte-derived suppressor cells (HuMoSCs), instead of MDSCs. Those HuMoSCs suppressed T cells proliferation and activation in vitro, and its suppressive function depended on STAT3. In vivo, adoptive transferred HuMoSCs promoted CD8+ FoxP3+ Treg cells, which induced immune tolerance, leading to the alleviation of xenogeneic GVHD in NSG mice. Application of Human MDSCs/regulatory monocytes adoptive transfer in humanized mouse Xeno-GVHD models and potential mechanisms were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Application of Human MDSCs/regulatory monocytes adoptive transfer in humanized mouse Xeno-GVHD models and potential mechanisms.

| Source | Inducer | Phenotype | Xeno-GVHD prevention | Induction of Tregs | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood | G-CSF | CD34+HLA-DR− CD33+ CD14+ regulatory monocytes | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | D’Aveni et al., 2015[44] |

| Monocytes | GM-CSF, IL-6 | CD33+CD11b+CD14+CD163+CD206+HLA-DR+ M-MDSCs | Yes | Yes | STAT3, Induction of CD8+ Tregs | Janikashvili et al., 2015[3] |

| CD34+ cells from CBU | GM-CSF, SCF | HLA-DRlow CD11b+ CD33+ M-MDSCs/G-MDSCs | Yes | Yes | Tregs induction, Inhibition of pro-inflammatory Th1/Th17 response | Park et al., 2019[52] |

| G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood | G-CSF | HLA-DR−/lowCD33+CD16−e-MDSCs | Yes | Yes | Tregs induction, Inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine production | Wang et al., 2019[15] |

CBU, cord blood unit; Xen- GVHD, Xenogeneic-GVHD.

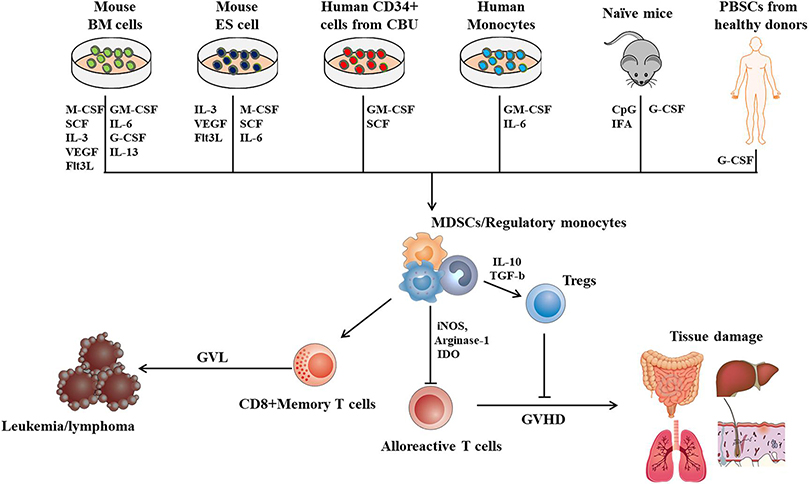

In summary, approaches to generate MDSCs ex vivo or in vivo have been established, (Figure 1). Promising results from pre-clinical studies have suggested that MDSCs are versatile cells that can alleviate the GVHD while maintaining GVL activities. Cellular immunotherapy using MDCSs might have great potential to be a game-changer in the field of allo-HSCT. Meanwhile, a deeper understanding of the mechanism in which MDSCs mitigate GVHD and preserve GVL activities is required before clinical practice, and standardized protocols for the generation of MDSCs must be proposed for further clinical evaluation.

Figure.1,

Approaches to generate MDCS for cellular therapy in GVHD and potential mechanism in which MDSCs prevent GVHD while persevere GVL activities. BM cells, Bone marrow cells; ES cells, Embryonic stem cell; CBU, cord blood unit; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cells; CpG, cytosine-phosphate-guanine; IFA, incomplete Freund’s adjuvant; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; IDO, Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; Tregs, Regulatory T cells.

2.2. MDSCs-based Cellular Therapy in Solid Organ Transplantation

In the field of solid organ transplantation, there is accumulated evidence to suggest that MDSCs play an essential role in tolerance induction after transplantation. Pre-clinical studies have indicated that ex vivo generated MDSCs might be a potential cellular therapy for maintaining allograft tolerance after solid organ transplantation. In Table 2, we summarized the current studies of MDSCs transfers in solid organ transplantation and potential mechanisms.

Table 2.

Application of adoptive transfer of MDSCs in solid organ transplantation models and potential mechanisms.

| Organ | Species | source of MDSC | Inducer | MDSC phenotype | Prolonged allograft survival | Induction of Treg | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart | Mouse | BM of naïve mice | anti-CD40L mAb | C11b + CD115 + Gr1hi M-IDSCs | Yes | Yes | IFN-γ, iNOS, CCR2 | Garcia et al., 2010 [53] |

| Mouse | Spleen of rapamycin-treated mice | Rapamycin | CD11b + Ls6G-Ly6Chi M-MDSCs | Yes | Yes | iNOS, mTOR and Raf/ MEK/ (ERK) | Nakamura et al. 2015 [54] | |

| Mouse | BM of naïve mice | Dex A GM-CSF | CD11b + Gr+1int/low | Yes | Yes | iNOS, GR signaling | Zhao et al., 2018 [55] | |

| Skin | Mouse | Spleen of ILT2 transgenic mice | HLA-C | CD11b + Gr-1 + M-MDSCs/G-MDSCs | Yes | Unknown | Arginase-1 | Zhaeg et al., 2008 [56] |

| Mouse | Spleen of LPS-treated mice | LPS | CD11b + Gr-1 + M-MDSCs/G-MDSCs | Yes | Unknown | IL 10, oxygenase-1 | De Wilde et al., 2009 [57] | |

| Mouse | BM of naïve mice | GM-CSF, IL-6, LPS | CD11b + Gr1hi/lo M-MDSCs/ G-SCDSO | Yes | Unknown | Over-activation of T tells aad antigen presenting cell | Drujont et al., 2014 [58] | |

| Mouse | BM of naïve mice | M-CSF, TNF-a or IFN-γ | CD11b + F4/80 + Ly6C + CD274 + M-SOSCs | Yes | Unknown | iNOS | Yang et al. 2016 2019 [59,60] | |

| Mouse | BM of naïve mice | GM-CSF, IL-6 | CD11b + Gr-1 + Ly6C + Ly6ChiCD16hiCD80hi M-MDSCs/G-MDSCs | Yes | Yes | Induction of T cell death | Carretero et al. 2016 [61] | |

| Mouse | BM of sepsis mice | CLP | CD11b + Gr1 + M-MDSCs/G-MDSCs | Yes | Unknown | Reduced td histopathological change | He et al., 2016 [70] | |

| Islet | Mouse | BM of naïve mice | GM-CSF, IL-6 | CD11b + Gr-1 + IL4Ra M-MDSCs/G-MDSCs | Yes | Unknown | C/EBPβ | Marigo et al., 2010 [62] |

| Mouse | BM of naïve mice | HSCs, GM-CSF | CD11b + Gr-1 + CD11c- B7-H1 + M-MDSCs/G-MDSCs | Yes | Yes | iNOS, CCR2 | Qin et al. 2017 [65], Arakawa et al., 2014 [66]; Chou et al., 2012 [67] | |

| Corneal | Mouse | BM of sepsis rake | CLP | CD11b + Gr1 + M-MDSCs/G-MDSCs | Yes | Unknown | Inhibited inflammatory cell infiltration, Reduced Neovascularization | He et al. 2015 [69], He et al. 2015 [70]; Han et al., [71] |

| Mouse | BM of tumer bearing mice | tumor | CD11b + Gr1 + M-MDSCs/G-MDSCs | Yes | Unknown | Inhibited inflammatory cell infiltration, Reduced Neovascularization | He et al., 2015 [69] | |

| Mouse | BM of naïve mice | GM-CSF, IFN-γ | Gr-1intCD11b + M-MDSCs/G-MDSSCs | Yes | Unknown | Inhibited inflammatory cytokies | Choi et at., 2016 [72] | |

| Mosse | BM of naïve mice | GM-CSF, IL-6 | CD11b + Gr1 + M-MDSCs/G-MDSCs | Yes | Unknown | iNOS, suppressed neovascularization | Ren et al., 2020 [73] | |

| Mouse | BM of naïve mice | Dex | CD11b + Ly6C + MHC-II M-MDSCs | Yes | No | iNOS, inhibited inflamatory cell infiltration | Lee et al., 2018 [74] | |

| Kidney | Rat | Blood and BM of tolerant recipients | anti-CD28 mAb | CD11b + CD80/86(+) CD172a + MHC-U-M-MDSCs/G-MDSCs | No | Yes (in vitro) | iNOS (in vitro) | Dugast et al., [33] |

| NHP | Leukapheresis product | Human GM-CSF and G-CSF | CD14 + HLADR-CD33 + M-MDSCs | No | Unknown | Unknown | Ezzelara et al., 2019 [80] |

BM, Bone marrow: Gr, glucocorticoid receptor, iNOS, inducible nitric aside synthase; Dex, Dexamethasone; HSCs, hepatic stellate cells; NHP, con-human primate, ERK, extracellular signal regulated kinase; CLP, cecal ligation puncture.

2.2.1. Cardiac Transplantation

An early study by Garcia et al. [53] has shown that bone marrow-derived tolerogenic monocytes are required for tolerance induction in a murine vascularized heart transplantation model. In this study, costimulatory blockade (anti-CD40L) induced differentiation of CD11b+CD115+Gr1+ monocytes (MDSCs) from marrow common myeloid precursor which are necessary for allograft tolerance. These suppressive monocytes are required for Treg cell development and their suppressive activities are dependent on IFN-γR and iNOS signaling. Adoptive transfer of bone marrow common myeloid precursor in combination with costimulatory blockade established long-term indefinite graft survival [53]. Nakamura et al. [54] reported that in a murine cardiac transplantation model, rapamycin treatment led to the recruitment of MDSCs and increased their expression of iNOS. Adoptive transcoronary arterial transfer of MDSCs from rapamycin-treated recipients prolonged allograft survival. Co-administration of rapamycin and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) inhibitor trametinib reversed rapamycin-mediated MDSC recruitment. Thus, they claimed that the mTOR and Raf/MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathways appeared to play a pivotal role in MDSC expansion. Zhao et al. [55] demonstrated that glucocorticoid (dexamethasone) with GM-CSF can stimulate the induction of CD11b+Gr-1int/low MDSCs and strengthen their suppressive activities. Adoptive transfer of ex vivo generated dexamethasone-induced MDSCs prolonged heart allograft survival which might be through the expansion of Treg cells. Mechanistically, iNOS signaling was involved in inhibiting T-cell response by MDSCs. Glucocorticoid receptor signaling seems to play a crucial role in the recruitment of MDSCs into allograft via up-regulating CXCR2 expression on MDSCs. Their study indicated dexamethasone and GM-CSF may be a new and important strategy for the induction of potent MDSCs to achieve immune tolerance in organ transplantation [55].

2.2.2. Skin Transplantation

Adoptive transfer of MDSCs has been proven to be an effective therapy for allograft rejection in the murine skin transplantation model. Using human inhibitory receptor ILT2 transgenic mice and a bm12 → C57BL/6, MHC-II minor mismatched skin graft model, Zhang et al. [56] demonstrated HLA-G- ILT2 amplifies CD11b+Gr1+ MDSCs that promote long-term survival of allografts. The investigators further demonstrated that ILT2-expressing-MDSCs presents an augmented suppressive function and was able to prolong skin graft survival following adoptive transfer into C57BL/6 recipients. Their study suggested that induction of MDSCs by using the ILT2 inhibitory receptor may be an attractive strategy for preventing rejection in clinical transplantation [56]. De Wilde and colleagues demonstrated that repetitive administration of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in vivo induces the development of CD11b+Gr-1+ MDSCs [57]. In a male-to-female skin transplantation model, the authors reported that the adoptive transfer of LPS-treated MDSCs significantly prolonged skin allograft survival. The investigator also demonstrated that LPS induced MDSCs suppressed Th1 and Th2 cytokine production while producing large amounts of anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 as a suppressive mechanism. Consistent with De Wilde’s study, Drujont et al. [58] reported that a single injection of LPS-activated MDSCs from in vitro culture resulted in a significant prolongation of skin allograft survival. Although those MDSCs failed to prevent the development of type 1 diabetes. Zhao’s group described that the combination of M-CSF and TNFα or IFN-γ efficiently induces functional M-MDSCs from murine BM cell culture [59, 60]. Those M-MDSCs were characterized by the expression of F4/80, CD80, and PD-L1. Upon adoptive transfer, those in vitro cultured MDSCs promoted immune tolerance in male-to-female skin transplanted mice. The mechanism behind this was suggested that M-CSF + TNFα or IFN-γ induced M-MDSCs upregulated the expression of iNOS, which was necessary for the suppression of T cell proliferation [59, 60]. To examine the effect of in vitro generated myeloid suppresser cells in allograft tolerance inductions, Carretero-Iglesia et al. [61] compared the function of three types of regulatory myeloid cell (autologous tolerogenic dendritic cells, suppressor macrophages, and MDSCs) in a skin transplant model. They found that these three types of suppresser cells exerted their suppressive function in different ways. MDSCs appeared to perform their immunosuppressive activities through induction of T cell apoptosis and the expansion of Treg cells. In addition to BM-derived myeloid suppresser cells, Sasaki, Hajime et al.[9] explored the potential of the iPSCs-derived immunosuppressive cell therapy in allograft transplant models. In their study, mouse iPSCs were generated from fibroblasts isolated from the ear tip of adult mice and differentiated into immunosuppressive macrophage-like cells (iPS-SCs) via culture with OP9 cells and cytokine cocktail containing GM-CSF. M-CSF IL-4 and LPS. Those iPS-SCs efficiently suppressed allogeneic T- and B-cell proliferation in a nitric oxide–dependent manner in vitro, and prolonged iPSC-Derived allograft (embryoid body) survival in vivo. In an allogeneic skin graft transplantation murine model, although iPS-SCs were insufficient in prolongation of skin allograft survival, it significantly reduced the alloantibody production[9]. These results suggest that iPSCs-derived suppressor cells might represent a potential immunotherapeutic strategy for allograft rejection after transplantation.

2.2.3. Pancreatic Islet Transplantation

Islet transplantation is a promising therapeutic strategy for the treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Considering the significate role of MDSCs in organ transplantation, Marigo et al. [62] reported murine MDSCs can be in vitro generated from mouse BM cells in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-6. When those BM-MDSCs were adoptively transferred into islet-allografted syngeneic mice, those BM-MDSCs induced long-term acceptance of islet allografts, significantly increased survival in mice transplanted with allogeneic islets. They noted that BM-MDSCs impaired the priming of CD8+IFN-γ+T cells which respond to the islet alloantigen. Moreover, C/EBPβ is necessary for the immunosuppressive program in BM-Derived MDSCs, and the immunoregulatory activity of BM-derived MDSCs was dependent on the C/EBPβ transcription factor. Using a different approach for in vitro MDSC generation, Lu’s group described that the addition of hepatic stellate cells (HSC) allowed the generation of MDSCs from BM cells. IFN-γ signaling pathway and complement component 3 (C3) in HSC is required for MDSC generation [63, 64]. The investigators demonstrated a single systemic administration of HSC-induced MDSCs markedly prolonged survival of islet allografts without the requirement of immunosuppression [65]. CCR2 expression was essential to allow the migration of HSC-induced MDSCs into islet allografts [65]. As expected, these HSC-induced MDSCs exert their immunosuppressive capacity through iNOS,[66] induction of T effector cells hyporesponsiveness, and B7-H1-mediated Treg cells expansion [67]. Taken together, the adoptive transfer of in vitro HSC-induced MDSCs prolongs islet graft survival by the expansion of Treg cells and suppression of alloreactive T cells, and chemokine receptor CCR2 seems to play a crucial role in the MDSC migration to allografts.

2.2.4. Corneal Transplantation

Inflammation and neovascularization can induce corneal graft rejection and failure [68]. Given the anti-Inflammation property of MDSCs, the investigators used corneal allograft murine models to test MDSCs as a therapeutic strategy in corneal transplantation. Pan’s group [69, 70] reported that sepsis-induced infectious-MDSCs (iMDSCs) purified from the bone marrow of cecal ligated and punctured (CLP) Balb/c mice could effectively mediate the suppression of CD4 T cell proliferation in vitro and significantly prolonged corneal allograft survival in vivo. Importantly, the group of the mice that received iMDSCs showed decreased neovascularization compared to the group that received tumor-induced MDSCs (tMDSCs) or no MDSCs. However, an additional dose of iMDSCs transfer did not further ameliorate corneal survival in their model [69]. In their follow-up study, these iMDSCs were proven to significantly prolong allograft survival in the corneal-skin combined transplant model (donor C57BL/6 to recipient Balb/c mice) [70]. Their finding was partly consistent with another study in which CD11b+ suppresser cells were induced by LPS [71]. Using cytokine-induced MDSCs from murine BM cell culture, Choi et al. reported that GM-CSF and IFN γ induced Gr-1intCD11b+ BM-MDSCs, adoptive transfer of those MDSCs reduced T cell infiltration in the allograft, which improved graft survival [72]. Meanwhile, Ren et al. [73] used GM-CSF +IL6 to generate murine BM-MDSCs in vitro, which suppressed neovascularization and prolonged corneal allograft survival in an iNOS-dependent manner.

Glucocorticoids (GCs) have been widely used to prevent allograft rejection in transplants. In a mouse corneal transplant model, Lee et al. [74] reported GCs to induce tolerance to corneal allografts through the expansion of MHC-II−CD11b+Ly6C+ monocytes (M-MDSCs) in the bone marrow and mobilization of the cells to peripheral lymphoid organs and graft site. Sorted CD11b+Ly6C+ MDSCs from the bone marrow of GC-treated mice inhibited CD4 T cells proliferation in vitro and prolonged the survival of corneal allografts when adoptively transferred into GC-untreated recipient mice [74].

2.2.5. Kidney Transplantation

The role of MDSCs in kidney transplant was first documented in a rat study by Dugast et al. [33]. Indeed, this was the first study in which MDSCs were identified in organ transplantation. In subsequent pre-clinical [75] and clinical studies [34, 76–78], the significant role of MDSCs have been studied and intensively reviewed by the experts in the field of organ transplant [24, 25, 79]. In the context of MDSCs adoptive transfer, a few studies have been reported. Dugast et al. [33] showed that multiple adoptive transfers of 2 × 106 MDSCs isolated from the blood or the bone marrow of tolerant rat recipients did not significantly prolong kidney allograft survival in other rat recipients. In a non-human primate (NHP) kidney transplant model, Ezzelarab et al. [80] reported that graft survival and histology were not affected by adoptive transfer of autologous, leukapheresis (after GM-CSF and G-CSF mobilization) product-derived M-MDSCs (CD14+HLADR-CD33+) on days 7 and 14 post-transplant compared to control monkeys that did not receive MDSCs [80]. The negative results from these two studies suggest that we are still lacking a better understanding of the role of MDSCs in kidney transplants setting with large animals. Further investigation on exploring the appropriate MDSC source and transfer doses, timing, and immunosuppressive agent support is required to maximize the therapeutic potential of MDSCs in kidney transplantation.

3. MDSC-based Cellular Therapy in Autoimmune Diseases

Adoptive transfer of MDSCs has been explored in murine models of many autoimmune diseases. Additionally, some results in ex vivo human models have been demonstrated as listed in Table 3; however, at the time of this review, no clinical trials of adoptive MDSC therapy for autoimmune diseases have been registered with clinicaltrials.gov or the EU clinical trials register.

Table 3.

Application of MDSCs adoptive transfer in Autoimmune disease and potential mechanisms.

| Disease | species | Source of MDSC | MDSC phenotype | Improved clinical or histologic indicators of disease | Treg population | Th17 population | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS | Mouse | Spleens of EAE mice | CD11b + Ly6g+ | Yes | Unchanged | Decreased | Ioannou 2012 [61] |

| Mouse | Spleens oi EAE mice | CD11b + GR-1+ | No | Unchanged | Increased | Yi 2012 [62] | |

| Posterior Uveitis | Mouse | Antigen stimulated ESI cells from naïve mice | CD11b + GR-1+ | Yes | Undetermined | Decreased | Tu 2012 [64] |

| Mouse | Spleens of EAU mice | CD11B + Ly6C+ | Yes | Undetermined | Decreased | Jeong 2018 [65] | |

| Myasthenia Crasis | Mouse | HSC induced BM cells | CD11b + GR-1+ | Yes | Undetermined | Decreased | Li 2014 [66] |

| Autoimmune arthritis | Mouse | Spleens of CIA mice | CD11b + GR-1+ | No | Undetermined | Increased | Zhang 2015 [67] |

| Mouse | Spleens of CIA mice | CD11C-CD11B + GR-1+ | Yes | Increased | Decreased | Park 2018 [70] | |

| Mouse | Spleens of CIA/AIA mice | CD11b + GR-1+ | Yes | Undetermined | Decreased | Zhang 2014 [72] | |

| Mouse | BM of CIA mice | CD11b + GR-1+ | No | Undetermined | Undetermined | Zhang 2015 [71] | |

| Mouse | Naïve mouse BM cells cultured with GM-CSF, IL-6, G-CSF | CD11b + GR-1+ | Yes | Undetermined | Undetermined | Kurko 2018 [73] | |

| Mouse | Spleens of CIA mice | CD11b + GR-1+ | Yes | Unchanged | Decreased | Fujii 2013 [74] | |

| Autoimmune Hepatitis | Mouse | Users of ConA + CBD mice | CD11b + GR-1+ | Yes | Undetermined | Undetermined | Hedge 2011 [76] |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | Mouse | Spleens of colitis mice /HSC induced BM cells | CD11b + GR-1+ | Yes | Undetermined | Undetermined | Guan 2013 [78] |

| Mouse | Spleens of VILLIM-HA mice | CD11b + GR-1+ | Yes | Increased | Undetermined | Haile 2008 [79] | |

| Mouse | Spleens of DSS mice | CD11b + GR-1+ | Yes | Undetermined | Undetermined | Zhang 2011 [80] | |

| Mouse | Tumor bearing mice | Percoll separate, CD115+ | Yes | Increased | Decreased | van der Touw [83] | |

| Psoriasis | Mouse | Naïve mouse BM cells cultured with GM-CSF, G-CSF | CD11b+(<>95% of population GR1+) | Yes | Increased | Decreased | Kim 2019 [84] |

| Alopecia Areata | Mouse | Spleens from AA, DTH, and AA/DTH mice | CD11b + GR-1+ | Yes | Minimal | Undetermined | Marhaba 2007 [85] |

| Increase | |||||||

| Type 1 Diibctes | Mouse | Tumor bearing mice | Gr-1 + CD115+ | Yes | Increased | Undetermined | Yin 2010 [88] |

| Mouse | Naïve mouse BM cells cultured with GM-CSF, IL-6 | CD11b + GR-1+ | No | Undetermined | Undetermined | Drujont 2014 [33] | |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | Mouse | PBMCs from SLE patients/MDSC depleted PBMCs | N/A | No | Undetermined | Increased | Wu 2016 [89] |

| Mouse | Peritoneal cells of pristane treated mice | CD11b + Ly6Chi | Yes | Increased | Undetermined | Ma 2016 [94] | |

| Mouse | Naïve mouse BM cells culrured with GM-CSF, G-CSF | CD11b + GR-1+ | Yes | Unchanged | Decreased | Park 2016 [95] | |

| Sjogren’s Syndrome | Mouse | Spleens of ASX NOD mire | CD11b + GR-1+ | No | Undetermined | Undetermined | Qi 2018 [97] |

| Anti-Fartor VIII | Ski utr | HSC induced BM cells | Bulk HSC induced BM cells | Yes | Unchanged | Undetermined | Bhatt 2015 [98] |

ASX, asymptomatic; BM, Bone marrow; HSC, Hepatic stellate cell

3.1. Diseases of the Nervous System

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease hallmarked by the autoinflammatory destruction of myelin. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis is a well-characterized mouse model for multiple sclerosis (MS) produced by the immunization of mice with encephalitogenic myelin antigen. Pathogenesis in this model is largely driven by Th17 and IL-17 signaling[81]. Contradictory evidence of the effects of MDSCs in this model has been reported. Ionnou et al. demonstrated that the adoptive transfer of allogenic Ly6G+CD11b+ (G-MDSC) myeloid cells derived from myelin antigen treated mice decreased paralysis and inflammatory lesions of the spinal cord compared to untreated and Ly6G-CD11b+ (M-MDSC) controls[82]. In contrast to Ionnou et al., Yi et al. demonstrated that adoptively transferred MDSCs purified from EAE mice increased Th17 differentiation of naïve CD4 T cells and increased IL-17 in vitro. Adoptive transfer of these MDSCs in EAE models reestablished active disease which was previously in remission secondary to gemcitabine treatment [83]. Furthermore, Mildner et al. demonstrated that adoptively transferred CD11b+Ly-6Chi cells are recruited to sites of inflammation in the brain and contributed to an inflammatory phenotype[84]. Discordance between these studies may be secondary to a difference in timing of MDSC administration (4 days after myelin antigen challenge vs. after the onset of disease), or due to the population of MDSCs (Ly6G+CD11b+ vs total GR-1+ CD11b+), or a result of the inflammation conditions used in each study. Data in human models are limited; however, MDSCs isolated from MS patients have been shown to decrease T cell proliferation ex vivo[82].

Experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU) is a murine model of autoimmune posterior uveitis, a condition in which retina-specific T cells cause local inflammation and destruction of retinal tissues. EAU is provoked by the immunization of mice against the interphotoreceptor retinal binding protein (IRBP). CD11b+Gr-1+ cells derived from stimulation of murine BM cells with retinal pigment epithelial cells inhibited T-cell proliferation and IFN-γ production in coculture assays. The adoptive transfer of these MDSCs significantly reduced the severity of EAU as determined by retinal histopathology. Furthermore, IFN-γ and IL-17 production was diminished in splenocytes derived from MDSC treated mice vs. untreated controls [85]. Subsequently, the difference between M-MDSCs and G-MDSCs was explored in this model. CD11b+Ly6C+ cells inhibited IRBP stimulated CD4 T cell proliferation in vitro, as opposed to increased proliferation when cocultured with CD11b+Ly6C− MDSCs. Adoptive transfer of allogenic CD11b+ Ly6C+ derived from EAU mice attenuated histological pathology features of the retina and decreased infiltration of T cells on day 21. Additionally, the frequencies of Th1 and Th17 cells in draining lymph nodes were decreased in mice receiving CD11b+Ly6C+ cell therapy. These effects were not observed with the adoptive transfer of CD11b+Ly6C− cells [86].

Myasthenia gravis, another autoimmune disease of the nervous system, characterized by impaired signal transduction in the neuromuscular junction. This impairment is largely due to autoantibodies against acetylcholine receptors (AchR). AchR is a T cell-dependent antigen and therefore myasthenia gravis pathology is mediated by both B and T cells. Adoptive transfer of hepatic stellate cell-induced MDSCs reduced sera AChR-specific IgG, complement activation in the neuromuscular junction, and improved muscle strength in the EAMG murine model of myasthenia gravis [87]. Furthermore, adoptive transfer of MDSCs reduced IFN-γ and IL-17 production in T cell recall assays, suggesting inhibition of Th1 and Th17 response, respectively.

3.2. Diseases of the Musculoskeletal System

The autoimmune arthritides are a group of disorders characterized by the autoimmune destruction of the joints through a variety of mechanisms. The most common and widely studied autoimmune arthritis is rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The role of MDSCs in autoimmune arthritis is controversial. MDSCs have been demonstrated to increase in mouse models of RA and increase proinflammatory markers such as IL-17 and Il-1ß [88, 89]. Others have suggested an anti-inflammatory role of MDSCs in RA through induction of FOXP3 and inhibition of IL-17 [90, 91]. Similarly, there are conflicting data on the effect of adoptive transfer of MDSCs for the treatment of arthritis. Adoptively transferred MDSCs have been shown to differentiate into osteoclasts and contribute to bone resorption [92]. Conversely, in multiple murine models of RA, the adoptive transfer of MDSCs has been shown to decrease the clinical and histologic manifestations of RA through the modulation of T cell populations and inflammatory cytokines [91, 93–95]. MDSC treatment reduced the relative proportion of Th1 and Th17 cells with an increase in the Treg population [91, 93, 95] and decreased serum inflammatory mediators including TNFα, IFN, IL-2, IL-6, and IL-17 [91, 93, 95]. This T cell skewing to an immunoregulatory phenotype was shown to be mediated by IL-10 as neither clinical improvement nor change in T cell populations was observed in IL-10 KO mice [91]. Additionally, the arginase 1 pathway has been demonstrated as an important mediator of RA amelioration via MDSC treatment. MDSC treatment increased the expression of Arg1in splenocytes, and the use of arginase pathway inhibitors attenuated the T cell modulating effects of MDSCs [91, 94].

In addition to the use of entire cell MDSCs, the adoptive transfer of MDSC derived exosomes has been demonstrated to ameliorate RA in mice [96]. Endosomes derived from G-MDSCs, but not M-MDSCs or circulating neutrophils, attenuated clinical and histologic manifestations of RA. G-MDSC endosome treatment decreased populations of Th1 and Th17 in vivo and in vitro. Furthermore, miRNAs isolated from G-MDSC exosomes were shown to influence T cell populations through the downregulation of the expression of Tbet and STAT3, the hallmark transcription factors in Th1 and Th17 cells, respectively.

3.3. Diseases of the Gastrointestinal System

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is chronic hepatitis of uncertain etiology characterized by immunopathologic liver inflammation. A widely used murine model of AIH is derived from the injection of mice with the T-cell stimulating concanavalin A (ConA). Treatment of mice with cannabidiol (CBD) was shown to expand hepatic populations of CD11b+Gr-1+ MDSCs in a murine model of AIH [97]. Populations of both M-MDSCs and G-MDSCs were enriched compared to non-CBD treated mice and purified cells from both subpopulations inhibited T cell proliferation in vitro. Adoptive transfer of bulk MDSCs derived from CBD treated mice prior to ConA administration significantly reduced AST, a marker of liver inflammation, as compared to mice without MDSC pretreatment [97, 98]. Knockout of TRPV1 attenuated MDSC expansion in CBD treated mice suggesting a possible mechanism for CBD signaling in MDSCs. Furthermore, the adoptive transfer of MDSCs derived from murine induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) was effective at ameliorating AIH in the HEP-OVA mouse model. Adoptive transfer of IPS-MDSCs reduced histologic inflammatory infiltrate and serum ALT compared to bone marrow derived DC adoptively transferred controls [7].

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a spectrum of diseases including Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and microscopic colitis. These diseases are characterized by intestinal inflammation. MDSCs have demonstrated effective amelioration of inflammatory bowel disease in a variety of murine disease models. In a trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS) model of IBD, adoptive transfer of CD11b+Gr-1+ MDSCs derived from both splenocytes of colitis mice and hepatic stellate cell conditioning, decreased intestinal immune infiltration, TNF, IFN-γ, and IL-17 concentration in colon tissue [99]. Additionally, the adoptive transfer of MDSCs decreased inflammation and mucosal destruction in the small and large bowel in a T cell-mediated model of IBD [100]. Similar reductions in intestinal inflammation were observed in a dextran sulfate sodium model (DSS) [101]. Interestingly, whereas the T cell-mediated model and the TNBS model are largely T cell-mediated [102] the DSS model can cause colitis in B and T cell-deficient mice[103]. Improvement in disease severity across these models suggests multiple mechanisms of inflammation attenuation in the setting of adoptive MDSC transfer.

Furthermore, Van der Touw W. et al, from our group, has demonstrated enhancement of the immunoinhibitory phenotype of adoptively transferred MDSCs through agonism of the pair Ig like receptor B (PIRB) in the setting of IBD [104]. Glatiramer acetate (GA, FDA approved drug) can bind to PIRB and enhance MDSC-dependent CD4+ regulatory T cell generation, while reducing proinflammatory cytokine secretion. Moreover, GA bound to the human ortholog of PIRB, Ig-like receptors B (LILRBs), and promoted an anti-inflammatory phenotype by reducing TNF-α production, increasing TGFß, and promoting CD163 expression typical of alternative maturation despite the presence of GM-CSF in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Taken together, GA can limit proinflammatory activation of myeloid cells, and therapeutics that target LILRBs represent novel treatment modalities for autoimmune indications [104]. Additionally, the successful induction of a more anti-inflammatory MDSC through PIRB signaling, supports the need to be further explore other methods to modulate MDSCs in the setting of autoinflammatory diseases to improve MDSC therapeutic efficacy.

3.4. Diseases of the Integumentary System

Adoptive transfer of MDSCs has shown disease attenuation in inflammatory conditions of the skin including psoriasis [105] and alopecia areata [106]. Psoriasis is a skin disease characterized by inflammatory plaques. Pathogenesis is driven by both innate and adaptive immunity overactivation resulting in inflammation and hyperkeratosis [107]. Adoptive transfer of MDSCs derived from the bone marrow of naïve mice significantly reduced skin erythema and scaling compared to untreated controls mice in an imiquimod induced psoriasis mouse model [105]. Furthermore, MDSC treatment reduced histologic immune infiltration of the skin and decreased serum TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-17A, and IL-23. Finally, spleens of MDSC treated mice were enriched for Tregs with a decrease in Th1 and Th17 cell populations.

Alopecia areata (AA) is an immunopathologic disease where immune destruction of hair follicles causes discrete areas of baldness. Topical immunotherapy with a potent contact allergen such as squaric acid dibutyl ester (SADBE) is an effective treatment for AA [108]. Gr-1+CD11b+ MDSCs were expanded in the spleens of mice treated with (SADBE) and these MDSCs inhibited T cell proliferation in vitro [106]. Subcutaneous implantation of MDSCs derived from AA mice induced significantly greater hair regrowth compared to the PBS injection control.

3.5. Diseases of the Endocrine System

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is a glucose regulation disorder caused by autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing ß cells in the pancreatic islets. In a murine T1D model where hemagglutinin (HA) specific T cells are adoptively transferred into mice with HA expressing pancreatic ß cells, Yin et al. demonstrated the adoptive transfer of tumor derived MDSCs with exogenous HA (MDSC +HA) administration decreased incidence of diabetes in the mice compared to MDSC or HA treatment alone [109]. Additionally, the MDSC +HA treatment decreased histologic inflammatory infiltrate in the pancreatic islets compared to PBS treated controls. T cells isolated from the spleens of MDSC + HA mice were less proliferative and skewed towards a Treg phenotype compared to controls with increased TGF-ß, IL-10, and FOXP3 expression. Therefore, demonstrating the protective effects of MDSCs by inducing anergy in autoreactive T cells and the development of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs in diabetic NOD mice model. This study demonstrates a remarkable capacity of transferred MDSCs to downregulate Ag-specific autoimmune responses and prevent diabetes onset, suggesting that MDSCs may possess great potential as a novel cell-based tolerogenic therapy in the control of T1D. In contrast to Yin, murine BM derived MDSCs were not effective at decreasing incidence of T1D in an OVA antigen model (RIP-OVA) and the addition of the antigenic peptide to the MDSC treatment did not suppress the CD8 T cell proliferation in vivo and exacerbated the incidence of T1D, although the BM derived MDSCs did prolong the skin alloengraftment (as discussed in section 2.2.2) [58]. This contrast may suggest the purity, source and suppressive function of cultured MDSCs needs to be well controlled as MDSCs after maturation can be as antigen presenting cells under inflammatory conditions. Additionally, the potency, the specific population of MDSCs used, the effects of dendritic cells, the antigen specific autoimmune T cell proliferation, the kinetics, and the timing of MDSC injections may need to be compared to further refine the use of therapeutic MDSCs.

3.6. Systemic Diseases/Other Disease Sites

3.6.1. Systemic Diseases

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is a systemic autoimmune disease with a wide variety of clinical presentations and proposed pathogenic mechanisms. The role of MDSCs in SLE remains controversial. Some evidence suggests a detrimental effect of MDSCs through the induction of Th17, IFN, and a decrease in Tregs [110–112] whereas other studies suggest a protective effect against autoreactive B and T cells and an induction of IL-10 [113, 114]. Similarly, the effects of the adoptive transfer of MDSCs in SLE have been mixed. In a humanized mouse model of SLE, the adoptive transfer of PBMCs from human SLE patients increased IL-17 production in mice, and the mice developed clinical manifestations including nephritis and anti-dsDNA antibodies [110]. Mice receiving MDSC depleted PBMCs had significantly reduced nephritis and anti-dsDNA titers compared to the bulk PBMC treated group. Conversely, some studies have shown attenuation of SLE via the adoptive transfer of MDSCs [115, 116]. In a pristane-induced lupus model, the adoptive transfer of M-MDSCs (CD11b+Ly6Chi) reduced antibody formation to an antigen challenge and inhibited T cells in an iNOS and PGE mediated manner. Additionally, T cell population skewing was observed with a decrease in Th1 cells and an increase in Tregs. In a sanroque mutation-driven model, the adoptive transfer of MDSCs derived from healthy C57BL/6 mice decreased liver and spleen inflammatory cell infiltration, decreased anti-dsDNA antibodies, and reduced proteinuria. Lymphocytes isolated from this model showed increased IL-10+ B cells and a decrease in Th1, Th17, and Tfh cells in mice treated with MDSCs.

Sjogren’s syndrome (SJS) is a disease characterized by diminished lacrimal and salivary gland function due to the autoimmune destruction of glandular tissue. However, the disease may present with a variety of systemic manifestations. NOD mice spontaneously develop an SJS like syndrome [117]. Adoptive transfer of MDSCs derived from 4 week NOD mice without SJS symptoms into 10 week old NOD mice was associated with worsening SJS symptoms and inflammation in the glandular tissue [118]. Additionally, the use of anti Gr1 antibodies to deplete MDSCs ameliorated the clinical symptoms of SJS disease further implicating a detrimental effect of MDSCs in SJS.

3.6.2. Other Disease Sites

A complication of repeated factor VIII administration for the treatment of hemophilia A is the development of anti-factor VIII antibodies. Adoptive transfer of hepatic stellate cell conditioned MDSCs reduced the anti-factor VIII antibodies in hemophilia A mice treated with recombinant factor VIII compared to dendritic cell (DC) adoptive transfer controls. Additionally, B and T cells harvested from the spleens of MDSC treated mice were less proliferative in response to factor VIII stimulation than DC treated controls [119].

4. Problems and Perspectives

Despite the positive outcomes of preclinical studies in MDSCs-based therapy, critical questions remain to be answered ahead of the clinical use of MDSCs. There are multiple approaches for MDSCs generation, the first challenge is to determine the optimal sources of MDSCs for adoptive transfer and the genetic background of MDSCs. This determination is critical and needs to be addressed prior to production. In pre-clinical studies, the adoptively transferred MDSCs can be syngeneic/autologous or allogeneic cells to the recipients, “Third-party” MDSCs (allogeneic/xenogeneic cells to donor and recipients) also been reported in the context of transplantation. In the murine allo-HSCT models, most of studies reported that adoptive transferred MDSCs for GVHD prevention are from BM cells culture of naïve mice, these MDSCs are donor-derived cells. The in vivo function of third-party mouse MDSCs has not been tested. Of note, in a xenogeneic GVHD (human to mouse) models, Park et al.[52] describe that the human cord blood derived MDSCs prevent GVHD mediated by human PBMCs from unrelated donors. These MDSC can be considered as “third-party” MDSCs, as they are not only xenogeneic cells to the mice but also allogeneic cells to PBMCs that induce GVHD. Since MDSCs can be generated from donor or even third-party cells, it will be less challenging to produce enough cells for transfer after allo-HSCT. However, in the field of organ transplant and autoimmune disease, current pre-clinical studies suggested that MDSCs for adoptive transfer need to the be syngeneic cells to the recipients, which is make it difficult to translate into clinic, as it will be challenging to harvest enough autologous cells for MDSC production from sick patients. So, the investigation on donor-derived or “third-party” MDSC therapy is required in further studies.

In the process of MDSCs-based cell therapy, induction of functional MDSCs is one of the most critical steps. There are many MDSCs inducers which have been reported to generate MDSC ex vivo and in vivo. These inducers comprise growth factors, such as GM-CSF, G-CSF, SCF et al, which induce the mobilization and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells or stem cells-like cells; pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-1β et al, which mediates STAT3 upregulation; other pro-inflammatory stimuli, such as LPS, Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), S100 family members, which actives NF-kB signal pathways; and immunosuppressive agents, such as Rapamycin. These inducers work either alone or in combination with others to promote the differentiation of MDSCs. It is worth noting that although there are many candidate induction methods for MDSCs production, the immunosuppressive activities of MDSCs induced by some of the promising candidates are untested in vivo. For instance, PGE2, a major cyclooxygenase (COX) product, has been shown to redirect the differentiation of DCs toward MDSCs remains largely untested in vivo [120]. Activation of COX2/PGE2 pathway promotes tumor progression by inducing MDSCs[121], potentiating the suppressive functions of MDSCs and increasing their capacity to expand Tregs[6]. By using PGE2, Obermajer et al.[122] generated human monocytes derived MDSCs ex vivo, and further investigation of the function of these MDSCs, especially in vivo functional evaluation is warranted.

In addition, the investigators need to take immunosuppressive agents into the consideration, as they are commonly used in the clinical practice for the treatment of allograft rejection, autoimmune diseases [123, 124]. Although many studies have reported that immunosuppressive drugs can positively or negatively regulate MDCS functions [24, 79, 125], the mechanism is still elusive. Before the clinical utilization of MDSCs, the influence of those medications on MDSCs must be further investigated. How the MDSCs influence Treg development and the suppressive adaptive immunity for antigen specific tolerance need be further evaluated. Additionally, the combination of MDSCs and immune suppressive costimulatory molecules needs to be further explored.

Overall, MDSC based cellular therapy shows great promise in preclinical models; however, the mixed results between models, subtypes, and investigators highlight the nuances of this therapy. Definitions of MDSC subtype and conditions from which they are derived will be important considerations as these therapies progress throughout preclinical and clinical models. Moreover, the fate and lifespan of MDSCs and how to maintain the immunosuppressive phenotype of MDSCs in vivo, especially in larger animal models is not well studied. A deeper understanding of adoptively transferred MDSCs in animal models will be required before establishing clinical MDSC protocols.

5. Conclusion

Adoptive transfer of immunosuppressive cells has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy for immune-related disorders. MDSCs are of myeloid origin but with strong immunosuppressive activities, therefore immunologists and clinicians have been attracted by their potential diagnostic and therapeutic value in transplantation and autoimmunity. Preclinical studies have already indicated that the adoptive transfer of MDSCs is a potential cellular therapy for maintaining transplantation tolerance and preventing autoimmune disease. The present review summarizes the current advancements in MDSC-based cell therapy in the context of transplantation and autoimmune diseases and discussed the limitations and future directions of this cellular therapy. Although there are still numerous technical and scientific challenges on MDSCs-based cellular therapy, we believe these challenges eventually will be overcome and clinical application of MDSCs-based cellular therapy in transplantation and autoimmune diseases will be significantly advanced in the future.

Highlights.

MDSC cell therapy represents a new paradigm in the treatment of immunopathology.

Preclinical success in treatment of transplant rejection, GVHD and autoimmune disease.

Heterogenous results highlight need to tightly control parameters of MDSC therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Zannatual Ferdous for the manuscript editing. This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health Grants and Cancer center innovative research awards to Shu-Hsia Chen and Ping-Ying Pan. Emily Herman endowed chair fund to Shu-Hsia Chen.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Kumar V, Patel S, Tcyganov E, Gabrilovich DI, The Nature of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment, Trends Immunol, 37 (2016) 208–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S, Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system, Nature reviews. Immunology, 9 (2009) 162–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Janikashvili N, Trad M, Gautheron A, Samson M, Lamarthee B, Bonnefoy F, Lemaire-Ewing S, Ciudad M, Rekhviashvili K, Seaphanh F, Gaugler B, Perruche S, Bateman A, Martin L, Audia S, Saas P, Larmonier N, Bonnotte B, Human monocyte-derived suppressor cells control graft-versus-host disease by inducing regulatory forkhead box protein 3-positive CD8+ T lymphocytes, J Allergy Clin Immunol, 135 (2015) 1614–1624 e1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Casacuberta-Serra S, Pares M, Golbano A, Coves E, Espejo C, Barquinero J, Myeloid-derived suppressor cells can be efficiently generated from human hematopoietic progenitors and peripheral blood monocytes, Immunol Cell Biol, 95 (2017) 538–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lechner MG, Liebertz DJ, Epstein AL, Characterization of cytokine-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells from normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, Journal of immunology, 185 (2010) 2273–2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tomic S, Joksimovic B, Bekic M, Vasiljevic M, Milanovic M, Colic M, Vucevic D, Prostaglanin-E2 Potentiates the Suppressive Functions of Human Mononuclear Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Increases Their Capacity to Expand IL-10-Producing Regulatory T Cell Subsets, Front Immunol, 10 (2019) 475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Joyce D, Fujino M, Morita M, Araki R, Fung J, Qian S, Lu L, Li XK, Induced pluripotent stem cells-derived myeloid-derived suppressor cells regulate the CD8(+) T cell response, Stem Cell Res, 29 (2018) 32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cao X, Yakala GK, van den Hil FE, Cochrane A, Mummery CL, Orlova VV, Differentiation and Functional Comparison of Monocytes and Macrophages from hiPSCs with Peripheral Blood Derivatives, Stem Cell Reports, 12 (2019) 1282–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sasaki H, Wada H, Baghdadi M, Tsuji H, Otsuka R, Morita K, Shinohara N, Seino K, New Immunosuppressive Cell Therapy to Prolong Survival of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Allografts, Transplantation, 99 (2015) 2301–2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cao X, van den Hil FE, Mummery CL, Orlova VV, Generation and Functional Characterization of Monocytes and Macrophages Derived from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells, Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol, 52 (2020) e108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Senju S, Haruta M, Matsumura K, Matsunaga Y, Fukushima S, Ikeda T, Takamatsu K, Irie A, Nishimura Y, Generation of dendritic cells and macrophages from human induced pluripotent stem cells aiming at cell therapy, Gene Ther, 18 (2011) 874–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gabrilovich DI, Bronte V, Chen SH, Colombo MP, Ochoa A, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Schreiber H, The terminology issue for myeloid-derived suppressor cells, Cancer research, 67 (2007) 425; author reply 426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bronte V, Brandau S, Chen SH, Colombo MP, Frey AB, Greten TF, Mandruzzato S, Murray PJ, Ochoa A, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Rodriguez PC, Sica A, Umansky V, Vonderheide RH, Gabrilovich DI, Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards, Nat Commun, 7 (2016) 12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Youn JI, Nagaraj S, Collazo M, Gabrilovich DI, Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice, Journal of immunology, 181 (2008) 5791–5802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wang K, Lv M, Chang YJ, Zhao XY, Zhao XS, Zhang YY, Sun YQ, Wang ZD, Suo P, Zhou Y, Liu D, Zhai SZ, Hong Y, Wang Y, Zhang XH, Xu LP, Liu KY, Huang XJ, Early myeloid-derived suppressor cells (HLA-DR(−)/(low)CD33(+)CD16(−)) expanded by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor prevent acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in humanized mouse and might contribute to lower GVHD in patients post allo-HSCT, J Hematol Oncol, 12 (2019) 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhao F, Hoechst B, Duffy A, Gamrekelashvili J, Fioravanti S, Manns MP, Greten TF, Korangy F, S100A9 a new marker for monocytic human myeloid-derived suppressor cells, Immunology, 136 (2012) 176–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cheng P, Corzo CA, Luetteke N, Yu B, Nagaraj S, Bui MM, Ortiz M, Nacken W, Sorg C, Vogl T, Roth J, Gabrilovich DI, Inhibition of dendritic cell differentiation and accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer is regulated by S100A9 protein, The Journal of experimental medicine, 205 (2008) 2235–2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sinha P, Okoro C, Foell D, Freeze HH, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Srikrishna G, Proinflammatory S100 proteins regulate the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells, Journal of immunology, 181 (2008) 4666–4675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Condamine T, Dominguez GA, Youn JI, Kossenkov AV, Mony S, Alicea-Torres K, Tcyganov E, Hashimoto A, Nefedova Y, Lin C, Partlova S, Garfall A, Vogl DT, Xu X, Knight SC, Malietzis G, Lee GH, Eruslanov E, Albelda SM, Wang X, Mehta JL, Bewtra M, Rustgi A, Hockstein N, Witt R, Masters G, Nam B, Smirnov D, Sepulveda MA, Gabrilovich DI, Lectin-type oxidized LDL receptor-1 distinguishes population of human polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer patients, Sci Immunol, 1 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sangaletti S, Talarico G, Chiodoni C, Cappetti B, Botti L, Portararo P, Gulino A, Consonni FM, Sica A, Randon G, Di Nicola M, Tripodo C, Colombo MP, SPARC Is a New Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell Marker Licensing Suppressive Activities, Front Immunol, 10 (2019) 1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Papaspyridonos M, Matei I, Huang Y, do Rosario Andre M, Brazier-Mitouart H, Waite JC, Chan AS, Kalter J, Ramos I, Wu Q, Williams C, Wolchok JD, Chapman PB, Peinado H, Anandasabapathy N, Ocean AJ, Kaplan RN, Greenfield JP, Bromberg J, Skokos D, Lyden D, Id1 suppresses anti-tumour immune responses and promotes tumour progression by impairing myeloid cell maturation, Nat Commun, 6 (2015) 6840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Melief J, Pico de Coana Y, Maas R, Fennemann FL, Wolodarski M, Hansson J, Kiessling R, High expression of ID1 in monocytes is strongly associated with phenotypic and functional MDSC markers in advanced melanoma, Cancer Immunol Immunother, 69 (2020) 513–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Talmadge JE, Gabrilovich DI, History of myeloid-derived suppressor cells, Nature reviews. Cancer, 13 (2013) 739–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Shao L, Pan S, Zhang QP, Jamal M, Rushworth GM, Xiong J, Xiao RJ, Sun JX, Yin Q, Wu YJ, Lie AKW, Emerging Role of Myeloid-derived Suppressor Cells in the Biology of Transplantation Tolerance, Transplantation, 104 (2020) 467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ochando J, Conde P, Utrero-Rico A, Paz-Artal E, Tolerogenic Role of Myeloid Suppressor Cells in Organ Transplantation, Front Immunol, 10 (2019) 374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].D’Aveni M, Notarantonio AB, Bertrand A, Boulange L, Pochon C, Rubio MT, Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in the Context of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation, Front Immunol, 11 (2020) 989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Koehn BH, Blazar BR, Role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, J Leukoc Biol, 102 (2017) 335–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Luyckx A, Schouppe E, Rutgeerts O, Lenaerts C, Fevery S, Devos T, Dierickx D, Waer M, Van Ginderachter JA, Billiau AD, G-CSF stem cell mobilization in human donors induces polymorphonuclear and mononuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells, Clin Immunol, 143 (2012) 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Fan Q, Liu H, Liang X, Yang T, Fan Z, Huang F, Ling Y, Liao X, Xuan L, Xu N, Xu X, Ye J, Liu Q, Superior GVHD-free, relapse-free survival for G-BM to G-PBSC grafts is associated with higher MDSCs content in allografting for patients with acute leukemia, J Hematol Oncol, 10 (2017) 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lv M, Zhao XS, Hu Y, Chang YJ, Zhao XY, Kong Y, Zhang XH, Xu LP, Liu KY, Huang XJ, Monocytic and promyelocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells may contribute to G-CSF-induced immune tolerance in haplo-identical allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Am J Hematol, 90 (2015) E9–E16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Vendramin A, Gimondi S, Bermema A, Longoni P, Rizzitano S, Corradini P, Carniti C, Graft monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell content predicts the risk of acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic transplantation of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-mobilized peripheral blood stem cells, Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 20 (2014) 2049–2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hongo D, Tang X, Baker J, Engleman EG, Strober S, Requirement for interactions of natural killer T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells for transplantation tolerance, Am J Transplant, 14 (2014) 2467–2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Dugast AS, Haudebourg T, Coulon F, Heslan M, Haspot F, Poirier N, Vuillefroy de Silly R, Usal C, Smit H, Martinet B, Thebault P, Renaudin K, Vanhove B, Myeloid-derived suppressor cells accumulate in kidney allograft tolerance and specifically suppress effector T cell expansion, Journal of immunology, 180 (2008) 7898–7906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Luan Y, Mosheir E, Menon MC, Wilson D, Woytovich C, Ochando J, Murphy B, Monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells accumulate in renal transplant patients and mediate CD4(+) Foxp3(+) Treg expansion, Am J Transplant, 13 (2013) 3123–3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hock BD, Mackenzie KA, Cross NB, Taylor KG, Currie MJ, Robinson BA, Simcock JW, McKenzie JL, Renal transplant recipients have elevated frequencies of circulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells, Nephrol Dial Transplant, 27 (2012) 402–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Jenq RR, van den Brink MR, Allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: individualized stem cell and immune therapy of cancer, Nature reviews. Cancer, 10 (2010) 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ferrara JLM, Levine JE, Reddy P, Holler E, Graft-versus-host disease, The Lancet, 373 (2009) 1550–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Blazar BR, Murphy WJ, Abedi M, Advances in graft-versus-host disease biology and therapy, Nature reviews. Immunology, 12 (2012) 443–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Inamoto Y, Flowers ME, Lee SJ, Carpenter PA, Warren EH, Deeg HJ, Storb RF, Appelbaum FR, Storer BE, Martin PJ, Influence of immunosuppressive treatment on risk of recurrent malignancy after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, Blood, 118 (2011) 456–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Michallet M, Sobh M, Barraco F, Thomas X, Balsat M, Lejeune C, Ducastelle S, Renault M, Tedone N, Labussiere H, Nicolini F-E, Addition of More Immunosuppressive Drugs As Graft-Versus-Host Disease (GVHD) Prophylaxis Does Not Improve Gvhd Outcomes in Reduced Intensity Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation from Unrelated Donors, Blood, 128 (2016) 5786–5786. [Google Scholar]

- [41].MacDonald KP, Rowe V, Clouston AD, Welply JK, Kuns RD, Ferrara JL, Thomas R, Hill GR, Cytokine expanded myeloid precursors function as regulatory antigen-presenting cells and promote tolerance through IL-10-producing regulatory T cells, Journal of immunology, 174 (2005) 1841–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Morecki S, Gelfand Y, Yacovlev E, Eizik O, Shabat Y, Slavin S, CpG-induced myeloid CD11b+Gr-1+ cells efficiently suppress T cell-mediated immunoreactivity and graft-versus-host disease in a murine model of allogeneic cell therapy, Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 14 (2008) 973–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Joo YD, Lee SM, Lee SW, Lee WS, Lee SM, Park JK, Choi IW, Park SG, Choi I, Seo SK, Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-induced immature myeloid cells inhibit acute graft-versus-host disease lethality through an indoleamine dioxygenase-independent mechanism, Immunology, 128 (2009) e632–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].D’Aveni M, Rossignol J, Coman T, Sivakumaran S, Henderson S, Manzo T, Santos e Sousa P, Bruneau J, Fouquet G, Zavala F, Alegria-Prevot O, Garfa-Traore M, Suarez F, Trebeden-Negre H, Mohty M, Bennett CL, Chakraverty R, Hermine O, Rubio MT, G-CSF mobilizes CD34+ regulatory monocytes that inhibit graft-versus-host disease, Sci Transl Med, 7 (2015) 281ra242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zhou Z, French DL, Ma G, Eisenstein S, Chen Y, Divino CM, Keller G, Chen SH, Pan PY, Development and function of myeloid-derived suppressor cells generated from mouse embryonic and hematopoietic stem cells, Stem cells, 28 (2010) 620–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Highfill SL, Rodriguez PC, Zhou Q, Goetz CA, Koehn BH, Veenstra R, Taylor PA, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Serody JS, Munn DH, Tolar J, Ochoa AC, Blazar BR, Bone marrow myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) inhibit graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) via an arginase-1-dependent mechanism that is up-regulated by interleukin-13, Blood, 116 (2010) 5738–5747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Koehn BH, Apostolova P, Haverkamp JM, Miller JS, McCullar V, Tolar J, Munn DH, Murphy WJ, Brickey WJ, Serody JS, Gabrilovich DI, Bronte V, Murray PJ, Ting JP, Zeiser R, Blazar BR, GVHD-associated, inflammasome-mediated loss of function in adoptively transferred myeloid-derived suppressor cells, Blood, 126 (2015) 1621–1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Koehn BH, Saha A, McDonald-Hyman C, Loschi M, Thangavelu G, Ma L, Zaiken M, Dysthe J, Krepps W, Panthera J, Hippen K, Jameson SC, Miller JS, Cooper MA, Farady CJ, Iwawaki T, Ting JP, Serody JS, Murphy WJ, Hill GR, Murray PJ, Bronte V, Munn DH, Zeiser R, Blazar BR, Danger-associated extracellular ATP counters MDSC therapeutic efficacy in acute GVHD, Blood, 134 (2019) 1670–1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Messmann JJ, Reisser T, Leithauser F, Lutz MB, Debatin KM, Strauss G, In vitro-generated MDSCs prevent murine GVHD by inducing type 2 T cells without disabling antitumor cytotoxicity, Blood, 126 (2015) 1138–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Karimi MA, Bryson JL, Richman LP, Fesnak AD, Leichner TM, Satake A, Vonderheide RH, Raulet DH, Reshef R, Kambayashi T, NKG2D expression by CD8+ T cells contributes to GVHD and GVT effects in a murine model of allogeneic HSCT, Blood, 125 (2015) 3655–3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Zhang J, Chen HM, Ma G, Zhou Z, Raulet D, Rivera AL, Chen SH, Pan PY, The mechanistic study behind suppression of GVHD while retaining GVL activities by myeloid-derived suppressor cells, Leukemia, 33 (2019) 2078–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Park MY, Lim BG, Kim SY, Sohn HJ, Kim S, Kim TG, GM-CSF Promotes the Expansion and Differentiation of Cord Blood Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells, Which Attenuate Xenogeneic Graft-vs.-Host Disease, Front Immunol, 10 (2019) 183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]