Abstract

Patient: Female, 74-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Leclercia adecarboxylata bacteremia

Symptoms: Cough • fever • shock • shortness of breath

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Infectious Diseases • Microbiology and Virology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Leclercia adecarboxylata is a gram-negative rod, which is normally found in water and food. It is an emerging pathogen that affects immunocompromised patients, including patients with hematological malignancies or those receiving chemotherapy. Generally, L. adecarboxylata is considered a low-virulence pathogen with an excellent susceptibility profile, but some strains may be resistant to multiple antibiotics, such as β-lactams. Moreover, L. adecarboxylata is usually isolated as a part of polymicrobial cultures in immunocompetent individuals, but there have been cases where it was the only isolate.

Case Report:

A 74-year-old woman who was non-immunosuppressed and had multiple comorbidities was admitted with acute decompensated heart failure due to pneumonia. She was treated with multiple courses of antibiotics including amoxicillin-clavulanate and ciprofloxacin for pneumonia, but her infection worsened, and she had cardiopulmonary arrest. After resuscitation, she was stable for several days but suddenly became confused and hypotensive. The septic screen showed L. adecarboxylata bacteremia without a clear source, which was treated successfully with meropenem for 14 days. After the meropenem course, the patient developed diarrhea and was found to have severe Clostridium difficile infection. She did not respond to oral vancomycin and intravenous metronidazole and died.

Conclusions:

This case illustrated an infection in a non-immunosuppressed individual by an organism that is considered an opportunistic pathogen, mainly affecting immunocompromised patients. The patient’s blood culture grew L. adecarboxylata, which was sensitive to all antibiotics but resolved with meropenem treatment. Owing to increasing L. adecarboxylata infections, we recommend further studies to understand the organism’s pathogenesis, risk factors, and resistance pattern.

Keywords: Bacteremia, Bacterial Infections, Carbapenems, Clostridium difficile, Immunocompetence

Background

Leclercia adecarboxylata is a motile, gram-negative rod, which was formerly known as Escherichia adecarboxylata [1]. However, deoxyribonucleic acid homology studies led to reclassifying the organism in a new group, and it was named L. adecarboxylata [2]. Most commonly, L. adecarboxylata is found in water and soil [3]. Generally, L. adecarboxylata is sensitive to most antibiotics; however, antibiotic resistance has been reported [4,5].

L. adecarboxylata infections are most often nonfatal owing to its low virulence and good antibiotic susceptibility [6]. The most identifiable risk factor for infection is immunosuppression; however, it was found that L. adecarboxylata could be part of polymicrobial infections in immunocompetent patients [7], particularly when the culture is taken from a wound [8]. Conversely, L. adecarboxylata has been reported as a sole isolate from blood, sputum, urine, and peritoneal fluid [9–12]. L. adecarboxylata might be disregarded in the context of poly-microbial infection because of its low virulence and ubiquity.

There are a wide variety of treatment options for L. adecarboxylata. However, its resistance to fosfomycin is commonly reported [4]. Resistance to other antibiotics such as trim-ethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, aminoglycosides, penicillin, and cephalosporins have also been reported [7]. Almost all cases of L. adecarboxylata infection are sensitive to carbapenems, amikacin, tetracycline, and tigecycline [7].

Here, we are reporting a case of isolated L. adecarboxylata bacteremia in a non-immunosuppressed patient. The aim of this study is to narrate the course, management, and outcome of such cases.

Case Report

A 74-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with progressive shortness of breath and productive cough for 1 week, along with increasing abdominal distention. She had a history of diabetes mellitus (with latest A1C 7.1%), hyper-tension, chronic kidney disease, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, coronary artery bypass graft, peripheral vascular disease, and right above-knee amputation.

The patient had progressive dyspnea, associated with orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and lower-extremity swelling. Her cough was productive with yellowish sputum, but she had no fever. The patient had recurrent abdominal as-cites secondary to heart failure (serum ascites albumin gradient of 1.5 g/L and ascitic protein of 26 g/L) for 6 months prior to presentation, which required weekly abdominal paracentesis. She was conscious and oriented, and her vital signs were stable. The examination did not show any stigmata of chronic liver disease. A cardiac examination revealed a pansystolic murmur in the left lower sternal border, while the lung examination showed fine bilateral lung crepitations. She had generalized abdominal tenderness, with tense ascites and bilateral lower-extremity pitting edema. The patient also had a stage 2 sacral ulcer, which was not infected.

The initial laboratory test results showed a normal white blood cell (WBC) count of 5.9×109 g/L. The chest X-ray at admission showed bilateral perihilar and right basilar airspace opacities, with right pleural effusion. She was admitted for acute decompensated heart failure secondary to pneumonia.

The patient was admitted to the cardiac care unit and was administered furosemide 40 mg IV twice per day and amoxicillinclavulanate. Six days after admission, the patient had a temperature of 38.9°C, with diffuse abdominal pain. Blood laboratory results showed an elevated WBC count of 13.7×109 g/L (reference range, 4.0–11.0×109), neutrophil count of 11.0×109 (reference range, 2.0–7.5×109), lymph count of 0.96×109 (reference range, 1.5–4.0×109), C-reactive protein level of 31.3 mg/L (reference range, 0.0–5.0 mg/L), and procalcitonin level of 0.42 ug/L (reference range, <0.25 ug/L). The patient was still febrile and not responding to amoxicillin-clavulanate, and was therefore switched to IV ciprofloxacin to treat the sepsis. A few hours later, the patient went into cardiac arrest. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was performed for 3 minutes, a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) was inserted, and the patient was intubated.

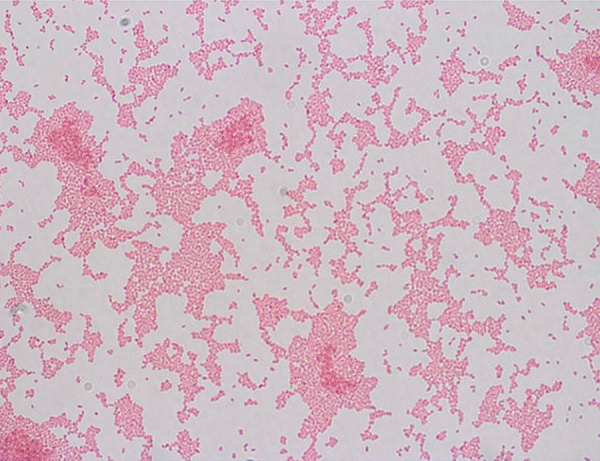

After 3 days, the patient was extubated and paracentesis was performed. Ascitic fluid culture results were negative but had a cell count of 196 leukocytes/µL. Two days later, the patient became confused and hypotensive and a laboratory examination showed that the inflammatory markers were elevated. A full septic screen was done and exhibited no organisms in the urine, sputum, or cerebrospinal fluid; however, a superficial swab from the sacral ulcer, which did not show signs of infection (Figure 1), grew Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, which were considered contaminants. A blood culture was taken using aerobic and anaerobic BACT/ALERT blood culture bottles (BioMérieux, Marcy l’Étoile, France) and was incubated in the BACT/ALERT3D blood culture machine. The culture was detected as positive after 18 h of incubation. A Gram stain from blood culture demonstrated gram-negative rods (Figure 2). The blood was subcultured on blood, MacConkey, and chocolate agar, and incubated at 37°C overnight. The agar plate showed grey, large mucoid colonies with weak lactulose fermentation (Figure 3). The organism was identified as L. adecarboxylata using the Vitek-MS microbial identification system (BioMérieux, France), and sensitivity was performed on the Vitek-2 sensitivity machine (BioMérieux, France) following the manufacturer’s instructions (Table 1). The abdominal pigtail catheter and PICC line were removed after the blood culture results were obtained, and ciprofloxacin was changed to meropenem, as the patient was not improving.

Figure 1.

Stage 2 sacral ulcer without signs of an infection.

Figure 2.

Gram stain: Gram-negative rods.

Figure 3.

(A) Chocolate and (B) blood agar: mucoid, grey large colonies. (C) MacConkey agar: weak lactose fermentation.

Table 1.

Antibiotics sensitivity to Leclercia adecarboxylata in the blood culture.

| Antibiotics | Sensitivity | MIC |

|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | Sensitive | ≤2 |

| Ciprofloxacin | Sensitive | ≤0.25 |

| Gentamicin | Sensitive | ≤1 |

| Meropenem | Sensitive | ≤0.25 |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | Sensitive | ≤20 |

MIC – minimum inhibitory concentration.

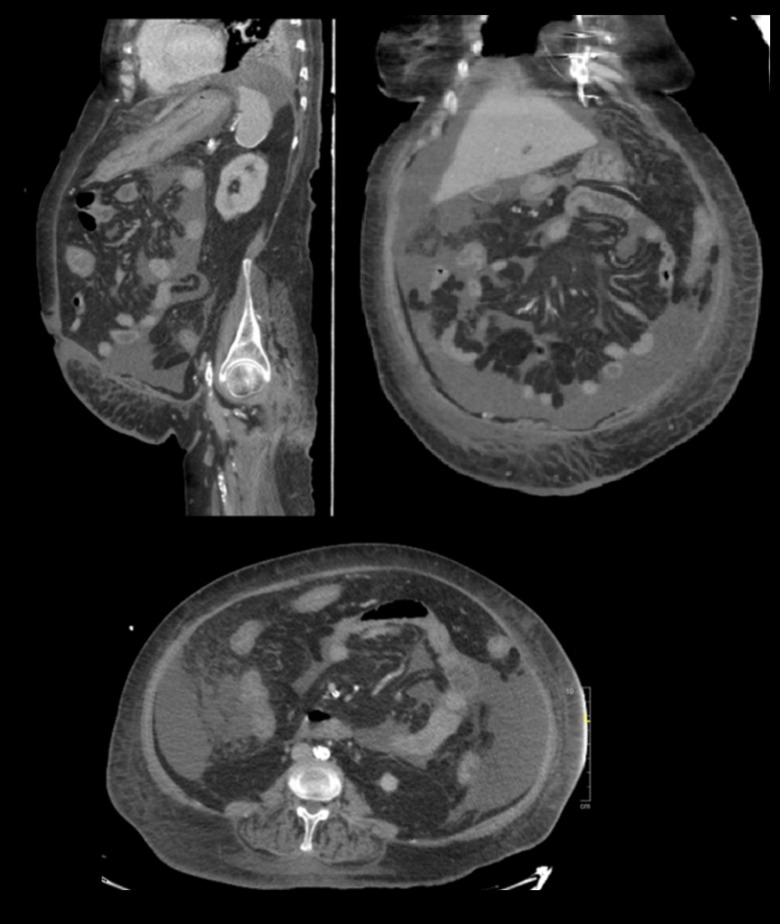

After 48 h of meropenem, her fever abated, inflammatory markers improved, and L. adecarboxylata bacteremia cleared. The patient completed 14 days of meropenem, and blood cultures were negative for organisms at the end of treatment. Five days before finishing the course of meropenem, the patient developed watery diarrhea, and Clostridium difficile was detected. The patient was administered oral vancomycin, and later IV metronidazole was added. Her diarrhea did not improve, her WBC count reached 49.7×109 g/L, and she required inotropic support to maintain her blood pressure. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed a circumferential thickening involving the distal transverse colon to the rectum, indicating colitis (Figure 4). The patient’s condition worsened over the following days (22 days after detecting C. difficile) until she died due to severe colitis.

Figure 4.

Abdominal and pelvis computed tomography scans showing circumferential wall thickening of the colon and rectum, prominent in the left transverse colon, and abdominopelvic free fluid with no free air.

Discussion

L. adecarboxylata is a flora of the gastrointestinal tract [13]. Initial isolates by Leclerc were from water, but later, L. adecarboxylata was commonly reported in the environment, especially in food and water [14–16].

In case reports and series, L. adecarboxylata was isolated from a large variety of specimens, including wounds, feces, urine, gallbladder, peritonsillar and periovarian abscesses, synovial fluid, peritoneal fluid in peritoneal dialysis, nosocomial pneumonia, and bacteremia [17–19]. L. adecarboxylata is an uncommon pathogen and is usually isolated as a part of poly-microbial wound cultures; it is postulated that it needs other bacteria to facilitate infection [13,17,20]. It might be the only isolate in immunocompromised patients, as Hess et al reported in patients with cirrhosis and hematological malignancies, and in those receiving chemotherapy [13].

Bacteremia caused by L. adecarboxylata is usually associated with immunosuppression and the presence of central lines. Monomicrobial bacteremia in the case of our patient was puzzling because her controlled diabetes and other comorbid conditions were not consistent with the pattern of immunosuppression found in the literature. Although diabetes may affect the body’s immunity, that usually occurs in the context of poor glycemic control [21]. In the literature, patients with L. adecarboxylata infection usually also have severe immunosuppression, for example, through the use of immunomodulators or chemotherapy [7,22,23]. On the other hand, few cases with diabetes as the only risk factor had skin and soft tissue infection [24,25]. Our patient had a PICC line for a few days, which could have been the source; however, only a peripheral blood culture was positive, contradicting this theory. Another possible source could have been iatrogenic peritonitis; however, all patients reported to have L. adecarboxylata peritonitis had peritoneal dialysis catheters, which our patient did not have. Although, skin commensals are much more likely to present in this setting. The third possibility is translocation from the gut, secondary to the patient’s C. difficile infection, which became symptomatic after the positive culture. The source of bacteremia in a 51-year-old woman who presented with nausea and vomiting and had small bowel thickening on an abdominal CT was presumed to be the gastrointestinal tract. That patient, however, had end-stage renal disease and was on hemodialysis [26]. Nonetheless, a lack of focus has been described in cases of L. adecarboxylata bacteremia [27] L. adecarboxylata isolates are reported to have a good sensitivity profile, and, in general, its resistance pattern is similar to that of other Enterobacteriaceae. However, fosfomycin resistance is more common with L. adecarboxylata. There are reports of resistant isolates exhibiting SHV-12 β-lactamase production; thus, they are behaving like an extended-spectrum β-lactamase organism [5]. Another study looked at hospital staff hand hygiene compliance and isolated VIM-1 Metallo-β-Lactamase producers [28]. The isolates were resistant to β-lactams, including carbapenems, and were susceptible to aztreonam. However, these were not clinical samples from patients.

There are no guidelines discussing treatment, but good response to β-lactams and fluoroquinolones was observed in multiple reports [7,12]. Our patient cleared her bacteremia with a brief course of meropenem, suggesting this antibiotic might be a good option to treat L. adecarboxylata infection. Nonetheless, the lack of identifiable source of the bacteremia can be considered as a limitation of the presented case.

Conclusions

L. adecarboxylata infection is not exclusive to immunocompromised patients. We reported a case of L. adecarboxylata bacteremia in a non-immunosuppressed patient. The organism was detected in the blood despite the patient being on multiple antibiotics, to which the organism was sensitive. Meropenem showed good activity against L. adecarboxylata. Further studies to understand the pathogenesis, risk factors, and resistance pattern of L. adecarboxylata are recommended, as it has become an emerging pathogen in the last decade.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References:

- 1.Armentrout R, Brown R. Molecular cloning of genes for cellobiose utilization and their expression in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;41:1355–62. doi: 10.1128/aem.41.6.1355-1362.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamura K, Sakazaki R, Kosako Y, Yoshizaki E. Leclercia adecarboxylata Gen. Nov., Comb. Nov., formerly known as Escherichia adecarboxylata. Curr Microbiol. 1986;13:179–98. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarma P, Bhattacharya D, Krishnan S, Lal B. Degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by a newly discovered Enteric bacterium, Leclercia adecarboxylata. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:3163–66. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.5.3163-3166.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stock I, Burak S, Wiedemann B. Natural antimicrobial susceptibility patterns and biochemical profiles of Leclercia adecarboxylata strains. Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;10:724–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazzariol A, Zuliani J, Fontana R, Cornaglia G. Isolation from blood culture of a Leclercia adecarboxylata strain producing an SHV-12 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1738–39. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1738-1739.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alosaimi R, Muhmmed Kaaki M. Catheter-related ESBL-producing Leclercia adecarboxylata septicemia in hemodialysis patient: An emerging pathogen? Case Rep Infect Dis. 2020;2020:7403152. doi: 10.1155/2020/7403152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spiegelhauer M, Andersen P, Frandsen T, et al. Leclercia adecarboxylata: A case report and literature review of 74 cases demonstrating its pathogenicity in immunocompromised patients. Infect Dis. 2018;51:179–88. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2018.1536830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Temesgen Z, Toal D, Cockerill F., III Leclercia adecarboxylata infections: Case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:79–81. doi: 10.1086/514514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forrester J, Adams J, Sawyer R. Leclercia adecarboxylata bacteremia in a trauma patient: Case report and review of the literature. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2012;13:63–66. doi: 10.1089/sur.2010.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez J, Sanchez F, Gutierrez N, Garcia J, Garcia-Rodriguez J. Bacterial peritonitis due to Leclercia adecarboxylata in a patient under-going peritoneal dialysis. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2001;19:237–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawamura H, Kawamura Y, Yasuda M, et al. [A clinical isolate of Leclercia adecarboxylata from a patient of pyelonephritis.] Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 2005;79:831–35. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.79.831. [in Japanese] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim H, Chon C, Ahn S, et al. Fatal spontaneous bacterial peritonitis by Leclercia adecarboxylata in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;68:1294–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hess B, Burchett A, Huntington M. Leclercia adecarboxylata in an immuno-competent patient. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57(7):896–98. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47673-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yehia H. Antimicrobial resistance patterns of Enterobacteriaceae and non-Enterobacteriaceae isolated from poultry intestinal. Life Sci J. 2013;10:3438–46. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Holy M, Osaili T, El-Sayed S, et al. Microbiological quality of leafy green vegetables sold in the local market of Saudi Arabia. Ital J Food Sci. 2013;25:446–52. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osaili T, Alaboudi A, Al-Quran H, Al-Nabulsi A. Decontamination and survival of Enterobacteriaceae on shredded iceberg lettuce during storage. Food Microbiol. 2018;73:129–36. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anuradha M. Leclercia adecarboxylata isolation: Case reports and review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(12):DD03–4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/9763.5260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fattal O, Deville J. Leclercia adecarboxylata peritonitis in a child receiving chronic peritoneal dialysis. PediatrNephrol. 2014;15(3–4):186–87. doi: 10.1007/s004670000436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghosh R, Misra R, Prasad K, Prasad N. Peritonitis by Leclercia adecarboxylata in a patient with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: The first case report from India. Int J Res Med Sci. 2016;4(4):1254–56. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adapa S, Konala V, Nawaz F, et al. Peritonitis from Leclercia adecarboxylata: An emerging pathogen. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7:829–31. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rayfield E, Ault M, Keusch G, et al. Infection and diabetes: The case for glucose control. Am J Med. 1982;72(3):439–50. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90511-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee N, Ki C, Kang W, et al. Hickman catheter-associated bacteremia by Leclercia adecarboxylata and Escherichia hermannii: A case report. Korean J Infect Dis. 1999;31:167–70. [Google Scholar]

- 23.De La Obra P, Domingo D, Casaseca R, et al. Bacteremia due to Leclercia adecarboxylata in a patient with multiple myeloma. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 1999;21:142–43. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Botero-Garcia C, Gomez C, Bravo J, et al. Leclercia adecarboxylata, a rare cause of soft tissue infections in immunocompromised patients, case report and review of the literature. Infect. 2018;22:223–26. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beltran A, Vicente A, Capilla S, et al. [Isolation of Leclercia adecarboxylata from wound exudate of a diabetic patient.] Med Clin (Barc) 2004;122:159. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(04)74180-9. [in Spanish] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ando A, Majewski L, Kajioka E. Leclercia adecarboxylata bacteremia: A case report and literature review of cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(Suppl.1):1096. [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Baere T, Wauters G, Huylenbroeck A, et al. Isolations of Leclercia adecarboxylata from a patient with a chronically inflamed gallbladder and from a patient with sepsis without focus. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(4):1674–75. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.4.1674-1675.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papagiannitsis C, Studentová V, Hrabák J, et al. Isolation from a nonclinical sample of Leclercia adecarboxylata producing a VIM-1 metallo-β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(6):2896–97. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00052-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]