Abstract

Close to 6 million Americans have Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia (AD/ADRD). These high-need, high-cost patients are vulnerable to receiving poor quality uncoordinated care, ultimately leading to adverse health outcomes, poor quality of life, and misuse of resources. Improving the care of persons living with dementia (PLWD) and their caregivers is an urgent public health challenge that must be informed by high-quality evidence. Although prior research has elucidated opportunities to improve AD/ADRD care, the adoption of promising interventions has been stymied by the lack of research evaluating their effectiveness when implemented under real-world conditions. Embedded pragmatic clinical trials (ePCTs) in healthcare systems have the potential to accelerate the translation of evidence-based interventions into clinical practice. Building from the foundation of the National Institutes of Healthcare Systems Collaboratory, in September 2019 the National Institute on Aging Imbedded Pragmatic AD/ADRD Clinical Trials (IMPACT) Collaboratory was launched. Its mission is to build the nation’s capacity to conduct ePCTs within healthcare systems for PLWD and their caregivers by (1) developing and disseminating best practice research methods, (2) supporting the design and conduct of ePCTs including pilot studies, (3) building investigator capacity through training and knowledge generation, (4) catalyzing collaboration among stakeholders, and (5) ensuring the research includes culturally tailored interventions for people from diverse backgrounds. This report presents the rationale, structure, key activities, and markers of success for the overall NIA IMPACT Collaboratory. The articles that follow in this special Issue describe the specific work of its 10 core working groups and teams.

Keywords: dementia, pragmatic, clinical trial, healthcare systems

INTRODUCTION

Close to 6 million Americans currently live with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (AD/ADRD). The estimated lifetime cost of caring for people living with dementia (PLWD) is $321,780, and on a population level annual costs exceed $290 billion.1–3 Observational research has shown that these high-need, high-cost patients are particularly vulnerable to receiving poor quality uncoordinated care, ultimately leading to adverse health outcomes, poor quality of life, and misuse of resources.2,4–7

Congress has charged the National Institute on Aging (NIA) with identifying effective and comprehensive programs to meet the complex needs of the growing population of PLWD and their caregivers (CGs). The scope of response needed to meet this public health challenge is akin to the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Disease’s galvanizing effort to address the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) crisis through its establishment of the AIDS Treatment Centers in the 1990s. As concluded by the National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for PLWD and their CGs, improving care for this population is an urgent public health challenge that must be met and informed by high-quality evidence.8

Prior research has elucidated opportunities to improve the care of PLWD and their CGs, and some small-scale traditional clinical trials of nonpharmacologic interventions targeting these opportunities have demonstrated efficacy in improving outcomes.9 However, the adoption of promising interventions into practice has been stymied by the lack of research evaluating their effectiveness when implemented under real-world conditions. Embedded pragmatic clinical trials (ePCTs) in healthcare systems (HCS) that serve PLWD have the potential to accelerate the translation of evidence-based interventions into clinical practice.9–14

In 2012, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) invested in infrastructure via the NIH HCS Research Collaboratory to strengthen the national capacity to conduct ePCTs in partnership with HCS.13,15 The NIH HCS Collaboratory has made pivotal contributions toward advancing the conduct of all aspects of ePCTs through its knowledge, development, and dissemination, establishment of the Distributed Research Network,16 and real-time support of an array of full-scale ePCTs in a variety of settings and medical disciplines. With this foundation, in 2017 NIA sponsored the “State of the Science for Pragmatic Trials of Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Persons with Dementia” conference, which concluded that conducting ePCTs with PLWD and their CGs had special considerations that merited a focused and coordinated initiative.9 Thus in June 2018, the NIA announced a request for applications for a dementia-focused collaboratory, culminating in the funding through a cooperative agreement (U54) of the NIA Imbedded Pragmatic AD/ADRD Clinical Trials (IMPACT) Collaboratory in September 2019. This report presents the rationale, structure, and objectives for the overall NIA IMPACT Collaboratory, and the articles that follow in this special Issue describe the specific work of its 10 core working groups and teams.

BACKGROUND

Embedded Pragmatic Clinical Trials

Traditional explanatory randomized clinical trials (RCTs) are designed to evaluate whether an intervention can improve health outcomes under ideal highly controlled conditions. Although efficacy trials contribute a critical evidence base for a given intervention, they are expensive, often underpowered, and even when positive, the findings may not be applicable to normal practice. In contrast, ePCTs aim to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions implemented under real-world conditions. The Pragmatic Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary (PRECIS)-2 framework describes how pragmatic and efficacy trials differ along nine domains, illustrating that most trial design features fall somewhere along the continuum between pragmatic and explanatory.11

The ePCTs commonly randomize and deliver the intervention at the level of the unit of care (eg, nursing home, physician practice), rather than the individual level. In addition, the intervention is implemented by providers during the course of clinical care, rather than by researchers under artificial circumstances. Instead of enrolling highly selective participants, ePCTs minimize restrictive eligibility criteria and attempt to expand recruitment to all individuals receiving care in a particular setting. The ePCTs also aim to leverage existing administrative or electronic health records to identify participants and ascertain outcomes, avoiding the need for a special research infrastructure to collect data. Intervention delivery, participant follow-up, and adherence are typically more flexible and closely align with usual care.

The NIH Stage Model for Behavioral Development provides additional context for ePCTs by describing six stages of interventional research17: basic science (stage 0); pilot testing (1); efficacy testing, first traditionally (2) and then with HCS (3); effectiveness research (4), such as ePCTs; and, finally, dissemination and implementation research (5). The model presents an ideal sequential progression for “the scientific development of potent and implementable interventions,” beginning with maximizing internal validity and ending with maximizing generalizability. However, in reality, the process is often iterative and quite lengthy. It is estimated that, on average, it takes 17 years to prove an intervention effective and translate it into practice,17–19 underscoring the pressing need to accelerate the pace of research to ensure that patients benefit as quickly as possible.

Readiness of Interventions for ePCTs in Dementia

At the 2017 NIA-sponsored state-of-the-science conference,9 the evidence supporting the efficacy of nonpharmacologic interventions for PLWD and their CGs across care settings was reviewed, recognizing that ideally a “minimal level” of stage II and III efficacy data should be present before proceeding to an effectiveness trial (ie, ePCT). Although several promising interventions were identified, most efficacy studies, whether positive or negative, were noted to have various limitations (eg, underpowered, restricted cohort eligibility). It was further recognized that other key parameters needed to be considered in assessing whether an intervention is ready for an ePCT, such as the maturity of the implementation protocol and alignment with stakeholder priorities. The work emanating from this conference motivated the development of the Readiness for Assessment for Pragmatic Trials (RAPT) tool that now serves as a framework to assess whether an intervention is ready to progress to an ePCT.9 The IMPACT Collaboratory uses the RAPT framework to assess the interventions proposed in the pilot award program applications.

Unique Considerations for Conducting ePCTs in AD/ADRD Populations

As concluded in the 2017 NIA-sponsored state-of-the-science conference,9 and as evidenced by the establishment of the IMPACT Collaboratory, ePCTs conducted among PLWD and their CGs have special considerations that merit a focused initiative. With only a small number of ePCTs in PLWD conducted or underway,20–24 many outside the United States,21–24 the IMPACT Collaboratory was established to address these specific considerations including unique settings that serve PLWD and their CGs (eg, nursing homes, assisted living communities), specific electronic health records systems and administrative data sets (eg, Minimum Data Set, Medicare claims), the need for standard approaches to identify PLWD and their outcomes using these data sources, distinct ethical and regulatory considerations for this vulnerable population, strategies to reduce known disparities in dementia care, and an array of particular stakeholders who must be engaged.

THE IMPACT COLLABORATORY MISSION AND VISION

The NIA IMPACT Collaboratory’s mission is to build the nation’s capacity to conduct ePCTs within HCS for PLWD and their CGs (Figure 1). This mission will be accomplished by (1) developing and disseminating best practice research methods, (2) supporting the design and conduct of ePCTs including pilot studies, (3) building investigator capacity through training and knowledge generation, (4) catalyzing collaboration among key stakeholders, and (5) ensuring the research includes culturally tailored interventions for people from diverse and underrepresented backgrounds. Accomplishing this mission will transform the delivery, quality, and outcomes of AD/ADRD care by accelerating the testing and adoption of evidence-based interventions within healthcare systems.

Figure 1.

The mission, vision, and values of the National Institute on Aging Imbedded Pragmatic Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or an AD-related dementia (AD/ADRD) Clinical Trials (IMPACT) Collaboratory.

REALIZING IMPACT’S MISSION

IMPACT Collaboratory Structure

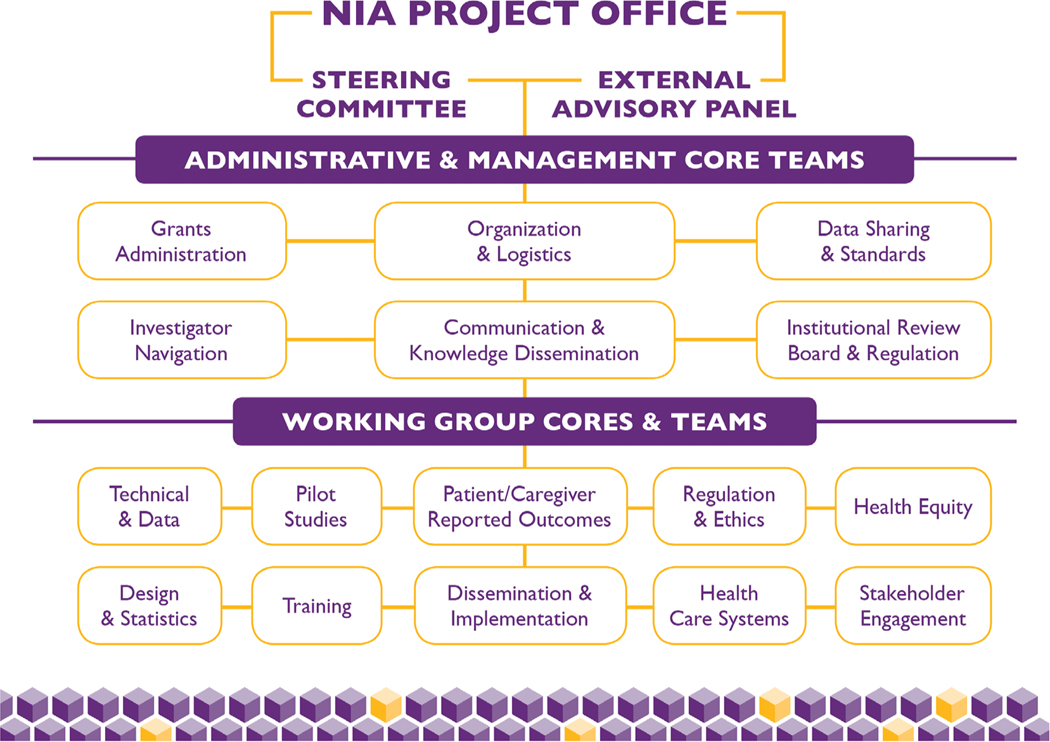

Figure 2 displays the organizational structure of the NIA IMPACT Collaboratory, and Table 1 presents the functions of each element. The NIA Project Office oversees all activities in cooperation with the two principal investigators. The external advisory panel is a six-member panel composed of national leaders in various disciplines integral to the conduct of ePCTs who are not otherwise connected with the collaboratory. The external advisory panel reviews the collaboratory’s progress every 6 months and advises its leadership on strategies to ensure key milestones and markers of success are being achieved. The steering committee is composed of the collaboratory’s principal investigators, three annually rotating core leaders, the leader of the pilot studies core, two NIA project scientists, and one external expert. The steering committee meets monthly to review the day-to-day activities of the collaboratory, and it deliberates on whether current approaches are working well or whether alternative strategies should be considered. The external advisory panel and steering committee meet together twice yearly.

Figure 2.

The organizational structure of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) Imbedded Pragmatic Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or an AD-related dementia (AD/ADRD) Clinical Trials (IMPACT) Collaboratory.

Table 1.

Functions of the NIA IMPACT Collaboratory’sa Key Organizational Elements

| Element | Function (s) |

|---|---|

| Leadership | |

| NIA project office | Oversees all activities in cooperation with the two principal investigators. |

| External advisory panel | Reviews key milestones every 6 months and advises on strategies to ensure markers of success are being achieved. |

| Steering committee | Reviews the day-to-day activities every month and deliberates on current approaches and need for alternative strategies. |

| Administration and management core teams | |

| Grants administration | Coordinates overall budget including about 40 subcontracts. |

| Organization and logistics | Coordinates all meetings/communication within the collaboratory. |

| Data sharing and standards | Implements a data-sharing plan for all collaboratory projects and centralized data capture system for pilot projects. |

| Investigator navigation | Coordinates assistance from collaboratory experts for IMPACT pilot project and Career Development Award recipients, as well as other NIA-funded investigators conducting ePCTs in dementia care. |

| Communication/Knowledge dissemination | Manages public website, knowledge repository, collaboratory intranet, social and news media, grand rounds and podcasts, and dissemination of all products created by the collaboratory community. |

| IRB and regulation | Oversees single IRB submissions, adherence to data use agreement standards, and serves as a liaison to the Data Safety Monitoring Board. |

| Working group cores and teams | |

| Technical and data | Leverages electronic health records and administrative data sources to conduct ePCTs. |

| Pilot studies | Leads a nationwide competitive pilot award program for pilot studies for ePCTs (about 40 awards over 5 years). |

| Patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes | Develops and supports use of patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes relevant to PLWD in the design and conduct of ePCT. |

| Regulation and ethics | Clarifies the balance among the competing priorities of conducting ePCTs to protect the interests of participants and assure healthcare systems that regulatory issues are addressed. |

| Health equity | Develops and implements strategies to address health equity in the conduct of ePCTs. |

| Design and statistics | Focuses on the statistical methods needed to design, conduct, and analyze ePCTs. |

| Training | Trains investigators to become experts in conducting of ePCTs through workshops, career development awards (about eight over 5 years). |

| Dissemination and implementation | Focuses on implementing and disseminating dementia care interventions in ePCTs and optimizing the potential for integration into healthcare systems. |

| Healthcare systems | Focuses on engaging the varied healthcare systems providing dementia care in the conduct of ePCTs. |

| Stakeholder engagement | Focuses on engaging key stakeholders in the conduct of ePCTs. |

National Institute on Aging Imbedded Pragmatic Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or an AD-related dementia (AD/ADRD) Clinical Trials (IMPACT) Collaboratory.

Abbreviations: ePCT, embedded pragmatic clinical trial; IRB, institutional review board; NIA, National Institute on Aging.

The administrative and management core operationalizes all of the collaboratory’s functions and enables and coordinates the work of its cores and teams. Divided between the home institutions of the two principal investigators, Brown University and Hebrew SeniorLife, the six teams of this ore include grants administration, organization and logistics, data sharing and standards, investigator navigation, communication and knowledge dissemination, and institutional review board and regulations. Two executive directors, one at each of the two administrative sites, oversees an administrative team that includes approximately 10 project directors and staff.

The IMPACT Collaboratory’s eight working group cores and two teams will be described in detail in separate articles in this special Issue. Briefly, in addition to the pilot studies core that oversees the collaboratory’s pilot grant program and the training core that leads all training activities, the disciplines of the cores and teams reflect the key elements that must be attended to when designing and conducting ePCTs such as technical and data, regulation and ethics, healthcare systems, patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes, dissemination and implementation, and the design and statistics, health equity team, and stakeholder engagement team. Each core group and team has a leader and up to six executive committee members who are nationally recognized experts in their fields. In total, these groups include approximately 60 experts from more than 30 academic institutions.

Knowledge Development and Dissemination

The NIA IMPACT Collaboratory develops and disseminates knowledge and best practices to enable the rigorous conduct of ePCTs among PLWD within HCS and promote methodological advances in this field. This knowledge base emanates from the working group cores and teams in the form of various products: (1) peer-reviewed journal articles, (2) technical reports, (3) abstract and symposia presentations at scientific meetings, (4) grand rounds and podcasts, (5) literature syntheses, (6) training curricula, (7) AD/ADRD-focused contributions to the HCS Collaboratory’s Living Textbook,15 and (8) media and other communications for lay audiences. All knowledge generated by the collaboratory is intended for public access and will be collated in a knowledge repository hosted on the IMPACT Collaboratory’s main public website. On an annual basis, each core and team identifies three to six products as deliverables for that year, which the collaboratory’s products committee reviews for areas of synergy and overlap, as well as gaps. Collaborative projects between cores and teams are encouraged.

Supporting the Design and Conduct of ePCTs

A cornerstone of the IMPACT Collaboratory’s activities is its pilot award program. Over 5 years, the collaboratory intends to fund approximately 40 one-year pilot studies for ePCTs through a nationwide competitive process. The pilot award program is coordinated by the pilot studies core with significant infrastructure support from the administration and management core.

The goal of the pilot award program is to fund and guide pilot studies to maximize the likelihood they will lead to full-scale ePCTs evaluating the effectiveness of non-pharmacologic interventions to improve the care of PLWD and their CGs. The IMPACT Collaboratory will not fund full-scale ePCTs but aims to make its pilot studies competitive for grants mechanisms for such large trials in dementia care issued by NIA. The collaboratory expertise will be available as a resource for NIA-funded investigators conducting full-scale ePCTs in this field.

In its first 4 months, the IMPACT Collaboratory created and operationalized all the infrastructure needed to launch this nationwide competition. The solicitation, external review, and selection of pilot awards for the first cycle were completed in January 2020. Several unique features of this infrastructure are worth noting. The administration core’s investigator navigator team coordinated extensive consultations with collaboratory experts drawn from the working group cores and team with all the applicants submitting proposals to help promote rigorous, pragmatic trial designs. In addition, the collaboratory contracted with a single external institutional review board and established an omnibus Data Safety Monitoring Board to streamline and centralize regulatory oversight for all pilot projects selected for funding.

Cycle 1 of our pilot program revealed several challenges that must be addressed in future cycles. Among the most notable concerns was whether the proposed intervention was ready for a pilot ePCT. The pilot studies are intended to serve as launch pads to stage IV effectiveness trials, so ideally they should have RCT evidence of the efficacy of the intervention. However, the pipeline of non-pharmacologic interventions in AD/ADRD meeting that hurdle are limited. In future cycles, greater consideration will be given to applying the RAPT tool to assess the pilot award applications, noting domains that should be present before embarking on a pilot ePCT (eg, alignment with stakeholder priorities) and those that are justifiably modifiable in the pilot phase (eg, implementation protocol, measurement). Cycle 1 also underscored the critical need for investigator training in ePCTs and prompted the collaboratory to accelerate the pace of its training activities. Finally, a wide net was cast in terms of soliciting pilot awards. Future cycles will set aside awards for specific areas that intersect with stakeholders’ (ie, healthcare systems, PLWD, and CGs) priority areas in AD/ADRD care and for which there is a reasonable evidence base of promising interventions.

Building Investigator Capacity

Conducting ePCTs in AD/ADRD within HCS requires unique research skills, yet the field is relatively nascent. Despite the NIH HCS Collaboratory’s remarkable progress, the number of investigators capable of rigorously designing and executing ePCTs in partnership with HCS remains limited, and those that have intersecting expertise in AD/ADRD populations are even fewer. Thus a critical objective of the IMPACT Collaboratory is to build the nation’s capacity to conduct impactful ePCTs in AD/ADRD by training a workforce of investigators prepared to carry on this work well into the future.

The training core will promote the career development and training of researchers through various mechanisms. Drawing on the expertise of all the collaboratory members, key activities of the training core will include (1) a 2-year Career Development Award program that will support up to six junior investigators, (2) annual in-person training workshop and retreat that will be open to trainees internal and external to the collaboratory, (3) training symposia at national scientific meetings, (4) online training modules, and (5) integrating junior investigators into the academic activities of working group cores and teams (eg, authorship of methodological papers) to promote their expertise and individual productivity.

Catalyzing Collaboration among Stakeholders

The ePCTs conducted in real-world settings mandate collaboration and buy-in from a variety of stakeholders. Thus the IMPACT Collaboratory has embedded stakeholder engagement activities into all its components under the guidance of its stakeholder engagement team. Unique stakeholder issues pertaining to conducting ePCTs in AD/ADRD populations include matching the capacity of PLWD with their abilities to participate as stakeholders, advocating for the voice of PLWD in early-stage disease, clarifying the role of proxy respondents when PLWD can no longer participate as stakeholders (eg, substituted representation), and addressing the priorities of HCS and frontline providers caring for this vulnerable population.

An immediate focus of the IMPACT Collaboratory’s stakeholder engagement team is to help devise practical, yet meaningful strategies to integrate stakeholder alignment into the selection of pilot studies. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) has set the bar with regard to integrating stakeholders as research partners. The IMPACT Collaboratory will leverage PCORI’s experience but will need to adapt stakeholder engagement strategies to meet its specific needs. For example, stakeholder input will be sought to ensure that proposed pilot interventions address overlapping priorities for HCS, PLWD, and CGs in the delivery of AD/ADRD. Moreover, pilot award applicants will be required to assess the anticipated financial costs and frontline provider burden needed to fully implement their proposed interventions, so that funding pilot studies testing interventions with little chance of real-world adoption is avoided.

Ensuring Research Addresses the Needs of PLWD from All Backgrounds

AD/ADRD does not have race, ethnic, cultural, or socioeconomic boundaries. In fact, black Americans are twice as likely to have dementia compared with white Americans.25 Moreover, there are marked and persistent racial and regional differences in the quality of care provided to PLWD. For example, blacks (vs whites) with advanced dementia, and those living in the southeastern United States (vs other regions) are far more likely to receive burdensome costly interventions of questionable clinical benefit at the end of life, such as tube feeding or hospitalizations.26–33 These differences persisted from 2000 to 2014.5 No guidance materials are available on strategies to address issues related to health equity in ePCTs. Although by design, all PLWD served by a given HCS should be included in ePCTs regardless of background, the selection of regions in which HCS or clusters (eg, nursing homes) are located and tailoring interventions to different backgrounds have important implications. Moreover, prior research suggests that inequities that permeate healthcare delivery in the United States translate into differential implementation in pragmatic trials, with interventions less likely to be delivered to black compared with white participants.34

Taken together and as aligned with recommendations of the National Research Summit on Dementia Care,35 the IMPACT Collaboratory includes a health equity team that will work with pilot projects and NIA-funded ePCT investigators in the early planning stages to ensure adequate consideration is given to diversity and inclusion in all aspects of study design.

MEASURES OF SUCCESS

As the NIA IMPACT Collaboratory moves forward, it will be critical for the internal leadership, external advisory panel, NIA, key stakeholders, and the public to be able to gauge its success. This success will be driven not only by the collaboratory’s purposeful activities but also less tangible interactions and networking emerging from its robust community. Short-term milestones will be relatively easy to assess including building the collaboratory infrastructure, launching a nationwide pilot award program, disseminating knowledge through grand rounds, publications, and other modalities, and hosting training symposia and workshops. Mid-range markers of success will also be relatively straight-forward to measure and will focus on the successful transition of pilot studies into funded full-scale ePCTs and the transformation of new investigators into experts in the field through the Career Development Award program. More long-term, sustainable success will be captured by the actual adoption and dissemination of interventions fostered by the IMPACT Collaboratory into HCS across the country. However, the ultimate, albeit elusive, marker of success will be realization of the IMPACT Collaboratory’s vision to transform the delivery, quality, and outcomes of care provided to PLWD and their CGs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial Disclosure: This work was supported by the National Institute of Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number U54AG063546 that funds NIA Imbedded Pragmatic Alzheimer’s Disease and AD-Related Dementias Clinical Trials Collaboratory (NIA IMPACT Collaboratory). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Susan L. Mitchell is supported by NIH-NIA K24AG033640.

Sponsor’s Role: The funding sources for this study played no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Vincent Mor chairs the Scientific Advisory Committee for naviHealth, a post-acute care convener serving hospitals and Medicare Advantage plans, a role for which he is compensated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. https://www.alz.org/media/documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures-2019-r.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2020

- 2.Jutkowitz E, Kane RL, Gaugler JE, MacLehose RF, Dowd B, Kuntz KM. Societal and family lifetime cost of dementia: implications for policy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:2169–2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80:1778–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell SL, Black BS, Ersek M, et al. Advanced dementia: state of the art and priorities for the next decade. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell SL, Mor V, Gozalo PL, Servadio JL, Teno JM. Tube feeding in US nursing home residents with advanced dementia, 2000–2014. JAMA. 2016; 316:769–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1529–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teno JM, Gozalo P, Khandelwal N, et al. Association of increasing use of mechanical ventilation among nursing home residents with advanced dementia and intensive care unit beds. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1809–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons with Dementia and Their Caregivers: Report to the National Advisory Council on Alzheimer’s Research, Care, and Services. 2018. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/national-research-summit-care-services-and-supports-persons-dementia-and-their-caregivers-final-summit-report. Accessed February 11, 2020.

- 9.Baier RR, Mitchell SL, Jutkowitz E, Mor V. Identifying and supporting non-pharmacological dementia interventions ready for pragmatic trials: results from an expert workshop. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19:560–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M, Oxman AD, et al. A pragmatic-explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS): a tool to help trial designers. CMAJ. 2009;180:E47–E57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, Donnan P, Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M. ThePRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ. 2015;350:h2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ware JH, Hamel MB. Pragmatic trials—guides to better patient care? N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1685–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinfurt KP, Hernandez AF, Coronado GD, et al. Pragmatic clinical trials embedded in healthcare systems: generalizable lessons from the NIH collaboratory. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17:144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tunis SR, Stryer DB, Clancy CM. Practical clinical trials: increasing the value of clinical research for decision making in clinical and health policy. JAMA. 2003;290:1624–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NIH Health Care Systems Collaboratory. 2018. http://rethinkingclinicaltrials.org/. Accessed February 11, 2020.

- 16.NIH Collaboratory Distributed Research Network (DRN). 2018. http://www.rethinkingclinicaltrials.org/nih-collaboratory-distributed-research-network-1/#references. Accessed February 11, 2020.

- 17.Onken LS, Carroll KM, Shoham V, Cuthbert BN, Riddle M. Reenvisioning clinical science: unifying the discipline to improve the public health. Clin Psychol Sci. 2014;2:22–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westfall JM, Mold J, Fagnan L. Practice-based research—“Blue Highways” on the NIH roadmap. JAMA. 2007;297:403–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green LW, Ottoson JM, Garcia C, Hiatt RA. Diffusion theory and knowledge dissemination, utilization, and integration in public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:151–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mor V, Volandes AE, Gutman R, Gatsonis C, Mitchell SL. PRagmatic trial of video education in nursing homes: the design and rationale for a pragmatic cluster randomized trial in the nursing home setting. Clin Trials. 2017; 14:140–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van de Ven G, Draskovic I, Adang EM, et al. Effects of dementia-care mapping on residents and staff of care homes: a pragmatic cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLOS One. 2013;8:e67325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thyrian JR, Hertel J, Wucherer D, et al. Effectiveness and safety of dementia care management in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:996–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Resnick B, Kolanowski A, Van Haitsma K, et al. Testing the evidence integration triangle for implementation of interventions to manage behavioral and psychological symptoms associated with dementia: protocol for a pragmatic trial. Res Nurs Health. 2018;41:228–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell NL, Perkins AJ, Gao S, et al. Adherence and tolerability of Alzheimer’s disease medications: a pragmatic randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1497–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lines JM, Weiner JM. Racial and ethnic disparities in Alzheimer’s disease a literature review. Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connolly A, Sampson EL, Purandare N. End-of-life care for people with dementia from ethnic minority groups: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gessert CE, Curry NM, Robinson A. Ethnicity and end-of-life care: the use of feeding tubes. Ethn Dis. 2001;11:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, et al. End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med. 2011;365: 1212–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meier DE, Ahronheim JC, Morris J, Baskin-Lyons S, Morrison RS. High short-term mortality in hospitalized patients with advanced dementia: lack of benefit of tube feeding. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:594–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fulton AT, Gozalo P, Mitchell SL, Mor V, Teno JM. Intensive care utilization among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive and severe functional impairment. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:313–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCormick WC, Hardy J, Kukull WA, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs in managed care patients with Alzheimer’s disease during the last few years of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1156–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Lipsitz LA. The risk factors and impact on survival of feeding tube placement in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:327–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Kuo SK, et al. Decision-making and outcomes of feeding tube insertion: a five-state study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59: 881–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Research Summit on Dementia Care. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/259151/DiversityRecom.pdf. Accessed February 13, 2020.

- 35.Loomer L, Volandes AE, Mitchell SL, et al. Black nursing home residents more likely to watch advance care planning video. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020; 68(3):603–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]