Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD), also known as eczema, is a common chronic pruritic inflammatory skin disease. The condition is estimated to affect up to 20% of children and 10% of adults, and it can have significant detrimental effects on sleep and overall quality of life.1-4 Topical corticosteroids (TCSs) are commonly used in the management of AD and serve as the mainstay of anti-inflammatory therapy. Despite their effectiveness and good safety profile, many patients and caregivers experience a phenomenon that has been dubbed in the literature as “TCS phobia.”5,6 TCS phobia refers to negative feelings and beliefs of patients and caregivers regarding TCSs, and has primarily been described in the context of AD. This phenomenon can manifest as underdosing and early treatment discontinuation, leading to uncontrolled AD and potentially inappropriate escalation to second- and third-line therapies. As described in the “Guidelines for the Management of Atopic Dermatitis for Pharmacists” published by Wong et al.7, clinicians can inadvertently contribute to TCS phobia by advising patients to arbitrarily limit the amount or duration of product use. This commentary will review TCS phobia and the risks and benefits of TCSs in the treatment of AD, allowing pharmacists to provide accurate and targeted counselling.

TCS phobia

TCS phobia is a pervasive global phenomenon that has been identified and studied in more than 15 countries.5 The prevalence of TCS phobia in studies has varied from 21% to 83.7%.5 TCS phobia has also been associated with decreased treatment adherence. In patients with TCS phobia, rates of partial adherence and nonadherence are higher than rates of partial adherence and nonadherence in patients without this phobia.8,9 The most common concerns that patients and caregivers have identified with use of TCSs are skin thinning and suppression of growth and development.5

Adverse effects of TCS

Potential cutaneous adverse effects from long-term use of TCSs include skin atrophy, purpura, striae, telangiectasia, hypertrichosis, and acneiform or rosacea-like eruptions.10 Areas of skin being treated with a TCS should be monitored periodically to assess for efficacy and adverse events. Although skin thinning has been identified as a common concern for patients and caregivers, a randomized controlled trial of 112 patients with AD treated with fluticasone propionate 0.005% ointment daily for 2 weeks, followed by daily 4 times per week for 2 weeks and then twice weekly for an additional 12 weeks, found no evidence of skin atrophy on serial skin biopsies.11

Corticosteroids applied topically can also be absorbed in quantities significant enough to cause systemic adverse effects, particularly when mid- or high-potency TCSs are used for long durations. The risk of systemic side effects with TCSs is also increased when patients are concurrently using corticosteroids in other dosage forms, such as oral or inhaled.12 Potential systemic adverse effects of TCSs include hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis suppression, and rarely, hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, and linear growth suppression when used in children.10 A review of 16 trials that assessed for HPA-axis suppression with TCS use found that 15 of the reviewed trials did not report any pathologic HPA-axis suppression. One trial reported pathologic HPA-axis suppression as defined by features of Cushing’s syndrome and symptoms of adrenocortical insufficiency. Affected patients in this study were using more than 100 g of clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream or ointment weekly for up to 18 months to treat adult psoriasis, far beyond what would typically be used for AD.13

Burden of AD

The risk of adverse events with TCS use must be balanced with the detrimental effects of uncontrolled AD. Uncontrolled AD is associated with increased itch, secondary skin infections, sleep disturbance, and social isolation.14 It can also have a significant impact on overall quality of life. The self-reported burden of AD in families of children with AD has been found to be comparable with that of diabetes and cystic fibrosis.15 Another study comparing various childhood chronic diseases found that AD had the second-largest impact on quality of life behind cerebral palsy.16 In adults, AD can affect social functioning, daily activities, clothing selection, shaving and use of makeup.14

Counselling patients

Patients and caregivers should be counselled about the relative risks and benefits of treatment with TCSs. Pharmacists can work with individual patients to define how AD affects their quality of life and develop corresponding goals of therapy. Patients can then be counselled on the specific benefits they should expect to see when TCSs are used as directed. Pharmacists can monitor to ensure goals of therapy are being met and can identify and resolve any concerns patients or caregivers may have during the treatment course. As AD is a chronic disease, placing arbitrary time limits on treatment duration can result in undertreatment and contribute to TCS phobia. However, patients should generally expect to see improvement in their AD within 2 to 4 weeks of regular treatment with TCS. If no improvement is seen within this time period, the diagnosis or treatment plan may need to be reconsidered.7

With regard to safety, patients and caregivers should be advised that when TCSs are used and monitored appropriately, the risk of adverse effects is minimal. Because skin thinning and growth suppression have been noted as common concerns, pharmacists should proactively address these concerns upon treatment initiation. Patients and caregivers can be reassured that skin thinning is rare when the appropriate strength of TCS for a given site is used as directed for the treatment of AD and that with appropriate monitoring, it can be caught early. Patients and caregivers can be counselled that growth suppression is rare and occurs only when high levels of TCSs are absorbed through the skin, and should it occur, it is usually insignificant, and children experience catch-up growth upon discontinuation of TCS treatment.17 Finally, it should be emphasized that the harm associated with undertreated AD generally outweighs the risk of adverse events.10

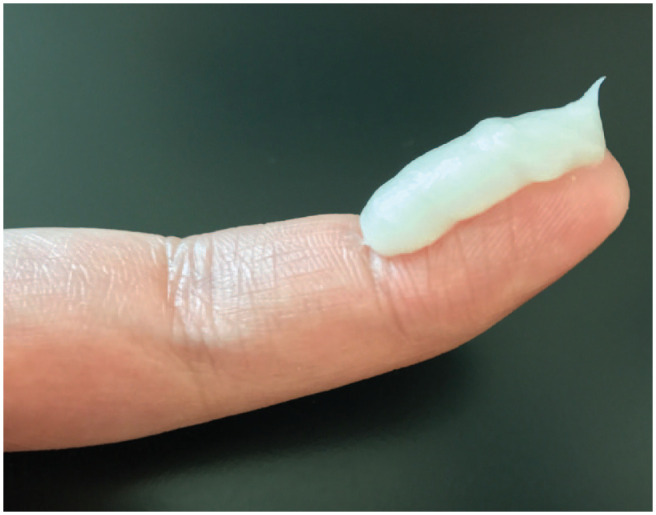

Many patients and caregivers are also unsure of how much TCS to apply, and phrases such as “apply sparingly” and “apply a thin layer” are vague and contribute to underdosing and TCS phobia. To ensure patients and caregivers apply appropriate quantities of TCS to adequately treat AD, pharmacists can counsel patients to use the fingertip unit when dosing topical medications. A fingertip unit is defined as the amount of cream or ointment squeezed from a tube with a 5-mm nozzle, applied from the distal skin crease to the tip of the index finger.18 The average weight of an adult fingertip unit is 0.5 g for males and 0.4 g for females.18 Modified guidelines have been developed for the use of fingertip unit counselling in pediatric populations.19 By using the fingertip system, pharmacists can clearly communicate dosing of topical medications to patients in a standardized fashion. The number of fingertip units to be used and approximate quantity of topical required to treat various anatomical areas in an adult are described in Table 1 and shown in Figure 1. Pharmacists can also use knowledge of the amount of topical required to treat different anatomical areas to identify patients who are filling prescriptions for their TCS significantly earlier or later than expected, potentially indicating inappropriate dosing.

Table 1.

Fingertip units required to treat various areas and the amount of topical product required to treat these areas twice daily for 1 week*

| Site | Fingertip units required per application | Quantity required for twice daily treatment for one week in an adult male |

|---|---|---|

| Face and neck | 2.5 | 17.5 g |

| Trunk (one side) | 7 | 49 g |

| One arm | 3 | 21 g |

| One hand | 1 | 7 g |

| One leg | 6 | 42 g |

| One foot | 2 | 14 g |

The average weight of a fingertip unit in an adult male is 0.5 g and 0.4 g in an adult female.

Figure 1.

A fingertip unit

As trusted medication experts and easily accessible health care providers, pharmacists are ideally positioned to counsel patients about TCSs and dispel misconceptions. Community pharmacists often see patients with chronic diseases such as AD more frequently than other health care providers, and as such, can monitor use and provide reminders and advice about the correct use of TCSs at each encounter. ■

Footnotes

Author Contributions:M. Ladda and P. Doiron initiated the project. M. Ladda wrote the manuscript drafts. M. Ladda and P. Doiron contributed to research and reviewed the final draft.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding:The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD:Matthew Ladda  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5128-2488.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5128-2488.

Contributor Information

Matthew Ladda, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto.

Philip Doiron, Division of Dermatology, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto; Division of Dermatology, Department of Medicine, Women’s College Hospital, Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto, Ontario; Division of Dermatology, Department of Medicine, Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto, Ontario.

References

- 1. Odhiambo JA, Williams HC, Clayton TO, Robertson CF, Asher MI, ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;124(6):1251-8.e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Silverberg JI, Hanifin JM. Adult eczema prevalence and associations with asthma and other health and demographic factors: a US population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;132(5):1132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee JH, Son SW, Cho SH. A comprehensive review of the treatment of atopic eczema. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2016;8(3):181-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bridgman AC, Eshtiaghi P, Cresswell-Melville A, Ramien M, Drucker AM. The burden of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in Canadian children: a cross-sectional survey. J Cutan Med Surg 2018;22(4):443-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li AW, Yin ES, Antaya RJ. Topical corticosteroid phobia in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol 2017;153(10):1036-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Callen J, Chamlin S, Eichenfield LF, et al. A systematic review of the safety of topical therapies for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 2007;156(2):203-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wong ITY, Tsuyuki RT, Cresswell-Melville A, Doiron P, Drucker AM. Guidelines for the management of atopic dermatitis (eczema) for pharmacists. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2017;150(5):285-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee JY, Her Y, Kim CW, Kim SS. Topical corticosteroid phobia among parents of children with atopic eczema in Korea. Ann Dermatol 2015;27(5):499-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kojima R, Fujiwara T, Matsuda A, et al. Factors associated with steroid phobia in caregivers of children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol 2013;30(1):29-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;71(1): 116-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Van Der Meer JB, Glazenburg EJ, Mulder PG, Eggink HF, Coenraads PJ. The management of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults with topical fluticasone propionate. The Netherlands Adult Atopic Dermatitis Study Group. Br J Dermatol 1999;140(6):1114-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ellison JA, Patel L, Ray DW, David TJ, Clayton PE. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function and glucocorticoid sensitivity in atopic dermatitis. Pediatrics 2000;105(4 pt 1):794-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levin E, Gupta R, Butler D, Chiang C, Koo JYM. Topical steroid risk analysis: differentiating between physiologic and pathologic adrenal suppression.J Dermatol Treat 2014;25(6):501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drucker AM, Wang AR, Li W-Q, Sevetson E, Block JK, Qureshi AA. The burden of atopic dermatitis: summary of a report for the National Eczema Association. J Invest Dermatol 2017;137(1):26-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chamlin SL, Chren M-M. Quality-of-life outcomes and measurement in childhood atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2010;30(3):281-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beattie PE, Lewis-Jones MS. A comparative study of impairment of quality of life in children with skin disease and children with other chronic childhood diseases. Br J Dermatol 2006;155(1):145-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eichenfield LF, Totri C. Optimizing outcomes for paediatric atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 2014;170(suppl 1):31-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Long CC, Finlay AY. The finger-tip unit—a new practical measure. Clin Exp Dermatol 1991;16(6):444-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Long CC, Mills CM, Finlay AY. A practical guide to topical therapy in children. Br J Dermatol 1998;138(2):293-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]