The last decade has shown significant progress in the fight against lung cancer, including advances in effective tobacco control, screening, targeted treatments, immunotherapies, and supportive care.1,2 At the same time, increased attention has highlighted the challenges faced by patients with lung cancer and their families, most notably the stigma associated with risk, diagnosis, and treatment.3 How have these changes been perceived by the larger public, oncologists, and individuals diagnosed with lung cancer? This is a question addressed by Rigney et al.4 in their cross-sectional surveys of lung cancer perceptions, administered 10 years apart. The researchers used the same questions and methodology to assess attitudes of separate samples of patients with lung cancer, oncologists, and members of the general public in 2008 (N = 1481) and 2018 (N = 1414). The surveys suggest that, despite higher lung cancer awareness and treatment optimism in 2018 versus 2008, stigma continues to be a formidable issue. In fact, public attributions of lung cancer blame remained steady over the decade, with higher acknowledgment and reports of stigma among patients with lung cancer. Overall, this study emphasizes significant progress in visibility and treatment, but also a critical need to focus on multilevel interventions to prevent stigma and mitigate its consequences.

Rigney et al.4 describe significant progress in the general public awareness of lung cancer; 94% of the 2018 sample reported familiarity with the disease (increased from 82.5% 10 y earlier). This finding can likely be attributed to the dedicated efforts of lung cancer advocates and advocacy organizations who have allocated significant time, energy, and resources to increase the visibility of individuals at-risk and those diagnosed with lung cancer.5 Increased media attention dedicated to lung cancer6 has also likely contributed to the heightened public awareness. Another promising finding is exhibited by the large shift in the number of oncologists (36% in 2008, 67% in 2018) who noted adequate treatment options for metastatic lung cancer. This finding reflects significant advances in treatment accompanied by focused education efforts aimed at medical providers. Perhaps this trajectory reflects “the end of nihilism” in relation to oncologists’ perceptions of lung cancer treatment and may help to curtail fatalistic beliefs associated with lung cancer among the general public and those at risk or diagnosed with the disease.7,8 However, despite the increasing optimism of oncology providers, the actual treatment rates of patients with metastatic lung cancer have shown limited improvement9,10 in recent years, with continued treatment inequities by socioeconomic status.11 Coordinated efforts are needed to continue the dissemination and implementation of U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments in the real world of lung cancer care.

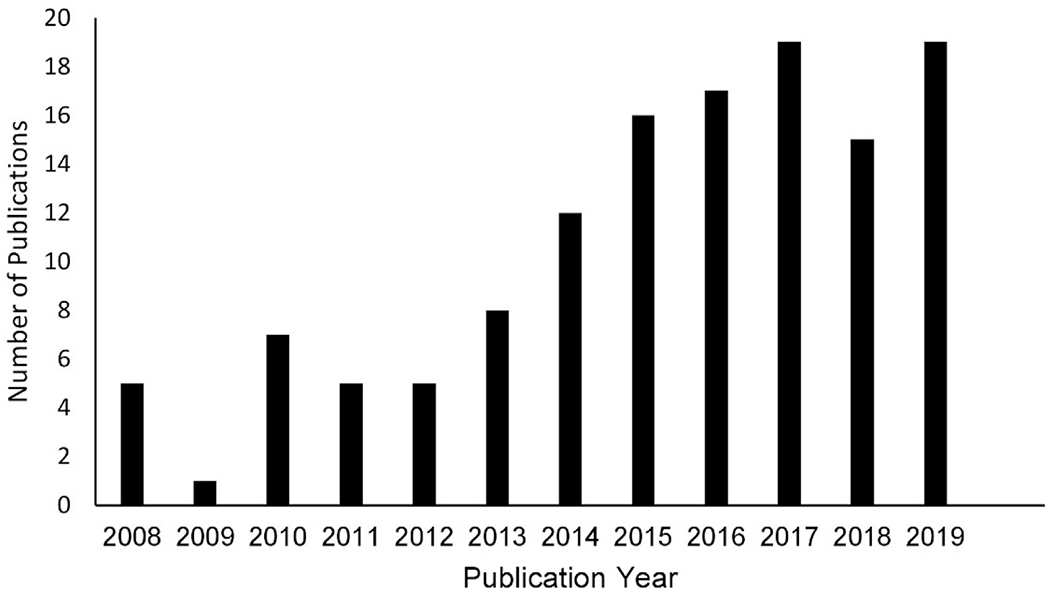

Rigney et al.4 show that, unfortunately, the substantially higher levels of lung cancer awareness and treatment have not been accompanied by correspondingly lower levels of lung cancer stigma. In 2018, 60.3% of the general public respondents agreed (somewhat or completely) with the statement, “Lung cancer patients are at least partially to blame for their illness,” representing a consistent perception of 2008 respondents (55.7% agreed). Furthermore, in the contemporary survey, 67.8% of oncologists agreed with the statement, “There is a stigma associated with lung cancer,” compared with 60.2% a decade earlier. Reports from the 2018 cohort of patients with lung cancer are particularly impactful, with a statistically significant higher percentage recognizing lung cancer stigma (72.1%, up from 54.5%), personally experiencing blame from strangers and acquaintances (52.4%, up from 31.4%), and feeling less supported by family and friends (25.5%, up from 10.5%). The study authors acknowledge the unintended consequences of aggressive tobacco control messaging in potentially increasing blame and reducing empathy for patients with lung cancer. There has also been increased focus on addressing stigma in both patient-focused12 and professional forums. For example, Figure 1 illustrates a steady uptick in professional publications addressing lung cancer stigma. Perhaps greater recognition of lung cancer stigma is a step in the right direction toward acknowledging its presence as the “elephant in the room”13 of lung cancer care and preparing to tackle this issue and its consequences more directly.

Figure 1.

The number of publications in PubMed containing the terms “lung cancer” and “stigma” (all fields) from 2008 to 2019.

Studies reporting the deleterious health impacts of lung cancer stigma have steadily accumulated over the past decade, underscoring the urgent need for effective stigma-reduction interventions.3 Lung cancer stigma is a complex phenomenon with multiple levels of influence, including the patient, clinician, and society. Encouraging data from our group and others demonstrate initial feasibility of patient-focused interventions in reducing stigma (H. A. Hamann, University of Arizona, unpublished data).14 Targeting health care providers is also a promising strategy for reducing stigma, particularly since most oncologists agreed that stigma is associated with lung cancer, and our previous work has found that 48% of patients with lung cancer report stigmatizing interactions with their health care providers.15 Banerjee et al.16 have developed an empathic communication skills module targeting physicians and other clinicians who treat patients with lung cancer. Preliminary findings demonstrate that the training was well-received and generally builds clinicians’ confidence in discussing smoking behavior with greater empathy in patient consultations. These findings should catalyze the development and testing of multilevel stigma-reduction interventions—coordinated efforts to target multiple levels of influence simultaneously—that are likely to produce a more profound and comprehensive impact on stigma than single-level interventions.3,17

Although studies focused on patient- and provider-level interventions are promising, considerable effort and resources are needed to continue investigating and enacting society-focused interventions. Stigma is increasingly seen as an unintended consequence of effective tobacco control policies and programs; efforts are underway to change the discourse around smoking and media campaigns away from fear, shame, and blame toward greater engagement of vulnerable populations, recognition of nicotine addiction, and the benefits of quitting smoking.18–20 Advocacy organizations also play a central role in developing and implementing large-scale societal interventions to mitigate lung cancer stigma. While treatment-related discoveries have brought greater attention to the value of lung cancer research for the broader cancer community, dedicated advocates and advocacy organizations have been tackling some of the most complex challenges. These include efforts to raise awareness and facilitate the implementation of lung cancer screening, support education and training to improve treatment decision-making, and confront the brick wall of lung cancer stigma that impedes achieving the best potential outcomes. Previous investigations have found that disease-related stigma can be reduced when advocates present patient narratives that illustrate a “human face” of the disease, broaden the public’s understanding of causal factors, and demonstrate shared emotions and aspirations between patient and nonpatient groups.21 These techniques may also encourage more patients to participate in advocacy by showing that others share their experiences, concerns, and humanity. Societal stigma noted in the Rigney study might plausibly be reduced by using personal contact (e.g., highlighting patients’ stories on television or social media platforms) as part of the comprehensive, multilevel stigma-reducing interventions that move beyond education or awareness alone.22 Future work is needed to establish the impact of such media campaigns on societal attitudes and behaviors. Interventionists could also learn from stigma-reduction efforts for other diseases, such as breast cancer and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which focused on highlighting treatability, along with emphasizing education, community engagement, and presenting patient narratives.21,23

The authors acknowledge limitations of their study, including important differences in the demographics of the two samples. The 2018 cohorts of the general public and patients with lung cancer included more people who never smoked than the 2008 respondents, and the 2018 general public cohort was also younger than in 2008. The relatively small proportions of patients with lung cancer and oncologists within the overall sample may also limit the generalizability of findings. Despite the strength of multiple administrations 10 years apart, survey questions did not have the benefit of rigorous psychometric testing to establish validity parameters, and longitudinal analyses are needed to determine changes in stigma over time. Recent work has provided more rigor to the patient-reported measurement of lung cancer stigma,24,25 and future efforts should focus on standardizing the metrics for provider- and population-level assessments of lung cancer stigma.

Despite limitations, the Rigney et al.4 study offers valuable insight into the trajectory of lung cancer perceptions from patients, oncologists, and the general public. The article highlights improvements in lung cancer awareness and care, while also illustrating the need to address the continuing burden of stigma. Lung cancer stigma is a regrettable, yet unfortunately common, challenge across the cancer care continuum. However, the rising tide of data and improved outcomes generate hope that creates a unique opportunity to make fundamental changes in how society views lung cancer. By banding together in recognizing and addressing lung cancer stigma, we can confront this challenge, share support and empathy for all individuals at increased risk or diagnosed with lung cancer, and leverage the surge of optimism throughout the lung cancer community to end stigma and further reduce the burden of lung cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially funded by the following National Institutes of Health awards: T32CA009461, P30CA008748, P30CA046934, and P30CA023074.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Herbst RS, Morgensztern D, Boshoff C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2018;553:446–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vachani A, Sequist LV, Spira A. AJRCCM: 100-year anniversary. The shifting landscape for lung cancer: past, present, and future. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1150–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamann HA, Ver Hoeve ES, Carter-Harris L, Studts JL, Ostroff JS. Multilevel opportunities to address lung cancer stigma across the cancer control continuum. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:1062–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rigney M, Rapsomaniki E, Carter-Harris L, King JC. Brief report: ten year cross-sectional analysis of public, oncologist, and patient attitudes about lung cancer and associated stigma. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16:151–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cure. Lending a hand: lung cancer advocacy groups help those in need. https://www.curetoday.com/publications/cure/2016/lung-2016-2/lending-a-hand-lung-cancer-advocacy-groups-help-those-in-need. Accessed November 20, 2020.

- 6.Grady D Lung cancer patients live longer with immune therapy. The New York Times. April 16, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers SK, Dunn J, Occhipinti S, et al. A systematic review of the impact of stigma and nihilism on lung cancer outcomes. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ernani V, Steuer CE, Jahanzeb M. The end of nihilism: systematic therapy of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2017;68:153–168, 102442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kehl KL, Hassett MJ, Schrag D. Patterns of care for older patients with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer in the immunotherapy era. Cancer Med. 2020;9:2019–2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.David EA, Daly ME, Li CS, et al. Increasing rates of no treatment in advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer patients: a propensity-matched analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:437–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maguire FB, Morris CR, Parikh-Patel A, et al. First-line systemic treatments for stage IV non-small cell lung cancer in California: patterns of care and outcomes in a real-world setting. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019;3:pkz020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lung Cancer Alliance. Lung cancer stigma: how to cope. https://lungcanceralliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Lung_Cancer_Stigma_How_to_Cope_web.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2018.

- 13.Holland JC, Kelly B, Weinberger MI. Why psychosocial care is difficult to integrate into routine cancer care: stigma is the elephant in the room. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:362–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chambers SK, Morris BA, Clutton S, et al. Psychological wellness and health-related stigma: a pilot study of an acceptance-focused cognitive behavioural intervention for people with lung cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2015;24:60–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamann HA, Ostroff JS, Marks EG, Gerber DE, Schiller JH, Lee SJ. Stigma among patients with lung cancer: a patient-reported measurement model. Psychooncology. 2014;23:81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banerjee SC, Haque N, Bylund CL, et al. Responding empathically to patients: a communication skills training module to reduce lung cancer stigma [e-pub ahead of print]. Transl Behav Med. 10.1093/tbm/ibaa011, accessed November 20, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richman LS, Hatzenbuehler ML. A multilevel analysis of stigma and health: implications for research and policy. Policy Insights Behav Brain Sci. 2014;1:213–221. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riley KE, Ulrich MR, Hamann HA, Ostroff JS. Decreasing smoking but increasing stigma? Anti-tobacco campaigns, public health, and cancer care. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19:475–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williamson TJ, Riley KE, Carter-Harris L, Ostroff JS. Changing the language of how we measure and report smoking status: implications for reducing stigma, restoring dignity, and improving the precision of scientific communication. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22: 2280–2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans-Polce RJ, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Schomerus G, Evans-Lacko SE. The downside of tobacco control? Smoking and self-stigma: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;145:26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Best RK. Common Enemies: Disease Campaigns in America. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rao D, Elshafei A, Nguyen M, Hatzenbuehler ML, Frey S, Go VF. A systematic review of multi-level stigma interventions: state of the science and future directions. BMC Med. 2019;17:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pulerwitz J, Michaelis A, Weiss E, Brown L, Mahendra V. Reducing HIV-related stigma: lessons learned from Horizons research and programs. Public Health Rep. 2010;125:272–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cataldo JK, Slaughter R, Jahan TM, Pongquan VL, Hwang WJ. Measuring stigma in people with lung cancer: psychometric testing of the Cataldo lung cancer stigma scale. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38:E46–E54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamann HA, Shen MJ, Thomas AJ, Lee SJC, Ostroff JS. Development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of a patient-reported outcome measure for lung cancer stigma: the Lung Cancer Stigma Inventory (LCSI). Stigma Health. 2018;3:195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]