Abstract

Centromere proteins (CENPs) are involved in mitosis, and CENP gene expression levels are associated with chemotherapy responses in patients with breast cancer. The present study aimed to examine the roles and underlying mechanisms of the effects of CENP genes on chemotherapy responses and breast cancer prognosis. Using data obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, correlation and Cox multivariate regression analyses were used to determine the CENP genes associated with chemotherapy responses and survival in patients with breast cancer. Weighted gene co-expression network and correlation analyses were used to determine the gene modules co-expressed with the identified genes and the differential expression of gene modules associated with the pathological complete response (PCR) and residual disease (RD) subgroups. CENPA, CENPE, CENPF, CENPI, CENPJ and CENPN were associated with a high nuclear grade and low estrogen and progesterone receptor expression levels. In addition, CENPA, CENPB, CENPC and CENPO were independent factors affecting the distant relapse-free survival (DRFS) rates in patients with breast cancer. Patients with high expression levels of CENPA or CENPO exhibited poor prognoses, whereas those with high expression levels of CENPB or CENPC presented with favorable prognoses. For validation between databases, the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database analysis also revealed that CENPA, CENPB and CENPO exerted similar effects on overall survival. However, according to the multivariate analyses, only CENPA was an independent risk factor associated with DRFS in GEO database. In addition, in the RD subgroup, patients with higher CENPA expression levels had a worse prognosis compared with those with lower CENPA expression levels. Among patients with high expression levels of CENPA, the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway was more likely to be activated in the RD compared with the PCR subgroup. The same trend was observed in TCGA data. These results suggested that high CENPA expression levels plus upregulation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway may affect DRFS in patients with breast cancer.

Keywords: breast cancer, centromere protein A, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway, residual disease

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women worldwide, with 2.1 million newly diagnosed cases in 2018 according to the World Health Organization (1). In the United States of America, 249,260 patients were diagnosed with breast cancer in 2016 (2). According to data released by the Cancer Center of China in 2014, the total incidence of breast cancer in China was 42.55 per 100,000 individuals, making breast cancer the most common malignant tumor in women (3).

The aim of chemotherapy is to interfere with the process of cell proliferation; therefore, most chemotherapeutic drugs exert major effects on proliferating cells, including cancer cells, which are characterized by abnormal and uncontrolled proliferation (4). Chemotherapy is currently the most effective method for systemic treatment of patients with breast cancer and prevents the division and proliferation of cancer cells by destroying cancer cell DNA and disrupting the intracellular components involved in mitosis (5). In addition, certain chemotherapeutic drugs kill cancer cells by inducing apoptosis (6).

Centromere proteins (CENPs) serve important roles in centromere function and mitosis; for example, CENPA encodes centromere protein A, which contains a variant of histone H3 that is specifically expressed on the centromere and kinetochore of the chromosome and is targeted by microfilaments during mitosis, resulting in the separation of centromeres during mitosis (7). CENPB supports kinetochore formation and contributes to the maintenance of chromosome segregation fidelity (8). CENPC serves as a scaffold for the specific recruitment of essential kinetochore proteins and links centromeres and kinetochores in mitosis (9). Thus, CENPs are important components of chromosomes during mitosis and can regulate the proliferation of tumor cells. Therefore, we hypothesized that the expression of CENP genes may be associated with the responses of breast tumor cells to chemotherapy and may affect patient survival.

The aim of the present study was to systematically explore the associations between 13 CENP genes and chemotherapy responses in patients with breast cancer and to identify genes that were most relevant to the patient prognosis.

Materials and methods

Gene datasets

Five breast cancer mRNA expression profiles, namely GSE20194 (10,11), GSE20271 (12), GSE22093 (13), GSE23988 (13) and GSE25066 (14,15), were extracted from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) database using the key words ‘breast cancer’, ‘neoadjuvant chemotherapy’ and ‘pre-operative chemotherapy’. Studies in which gene expression levels were analyzed in genome profiling data using pretreatment biopsies from patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy were included. The first four datasets (GSE20194, GSE20271, GSE22093 and GSE23988) were used as the training dataset (n=620 patients), and the fifth dataset (GSE25066) was used as the validation dataset (n=508 patients). The mRNA expression profiles of breast cancer from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; http://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) database were used for validation. In the GEO database, the result of pathological response was classified into pathological complete response (PCR) and residual disease (RD). In TCGA database used for validation, the result of pathological response was classified into clinical complete response (CCR) and RD.

Immunohistochemistry and molecular classification

Immunohistochemistry and molecular classification results were extracted from the GEO database. The hormone receptor status of a tumor was defined as positive when the immunohistochemistry results were positive for either estrogen receptor (ER) or progesterone receptor (PR) in ≥1% of cells and as negative when both ER and PR were negative. According to global consensus (16), HER2 expression status was defined as negative when the immunohistochemistry results were negative or 1+, and as positive when the results were 3+. HER2 positivity was evaluated according to the results of fluorescent in situ hybridization if the immunohistochemistry results were 2+. Tumor stage was re-evaluated in accordance with the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer system (17). Tumors were classified according to histological grade as well differentiated (G1), moderately differentiated (G2), poorly differentiated and undifferentiated (G3) or unknown.

PAM50 subtype classification by ‘genefu’

Data were extracted from the GEO database and, according to the PAM50 algorithm (18) using the ‘genefu’ package (19) of R software (version 3.5) (20), tumors were classified into basal-like, HER2-enriched, luminal A, luminal B, or normal breast-like molecular subtypes.

Weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA)

Data of this part were extracted from the GEO database publicly mentioned above. The ‘WGCNA’ package in the R software (21) was used to perform scale-free network topology analysis of microarray expression data of breast cancer samples. Standard WGCNA parameters were used for analysis. Using WGCNA, a co-expression module of genes associated with patient clinicopathological characteristics was extracted from the breast cancer data for subsequent analysis.

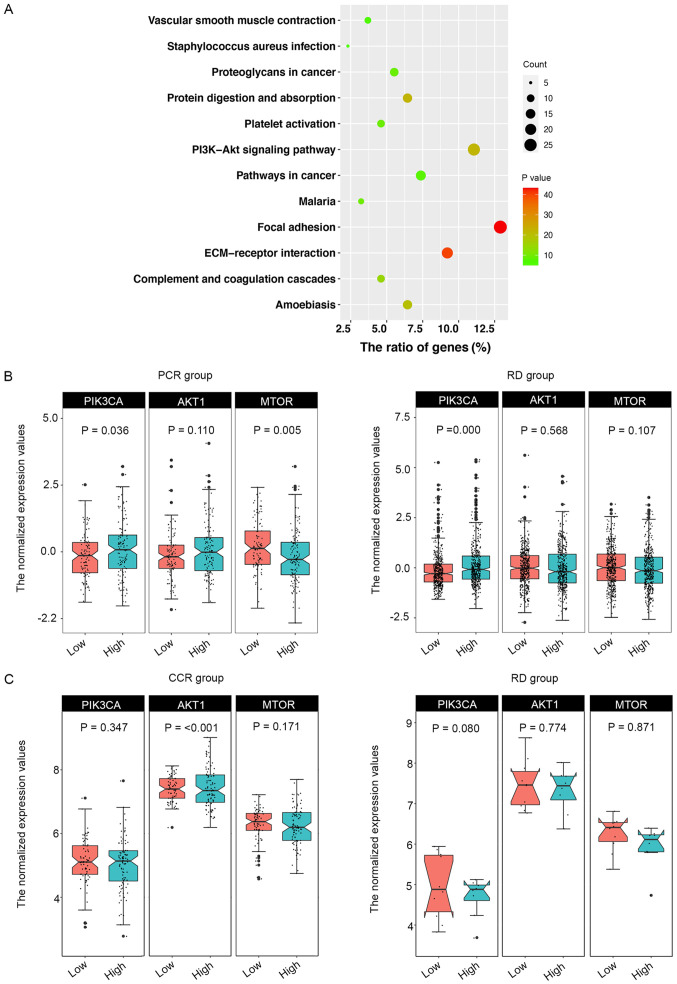

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis of co-expression modules

KEGG pathway analyses were performed to determine the biological functions of the genes in the green module identified by WGCNA to be highly correlated with CENPA using the DAVID Bioinformatics Tool (version 6.8; http://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant result. A total of 12 records were extracted. Graphs were generated using the ‘ggplot2’ R package (22).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean, range, standard deviation or proportion. Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 3.5). Univariate and multivariate survival analyses were performed using Cox regression models. The χ2 test was used to analyze the associations between CENP expression levels and patient clinicopathological characteristics. Kaplan-Meier curves were used for survival analysis, and the Cramér-von Mises and log-rank tests were used for the curves with and without crossovers, respectively. Comparisons of correlations were performed using the ‘correlation coefficients’ module in MedCalc software (Version 19.6.4; MedCalc Software, Ltd.). For comparisons of means, continuous variables between groups were analyzed using the independent-samples Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA. Comparisons of rates were performed using the χ2 test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Basic characteristics of the study population

In the present study, five datasets including a total of 1,128 patients were evaluated. The specific characteristics of each study are presented in Table I. The cancer grades were primarily II and III, and the nuclear grades were mainly G2 and G3. All patients in the present study received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and the PCR rate was ~22.4% for all datasets combined. Data of 1,025 patients were extracted from TCGA; all of these patients were evaluated for overall survival rate, and 175 patients in this cohort with chemotherapeutic response were evaluated for the gene expression levels of PI3K, AKT and MTOR.

Table I.

Basic characteristics of the study population.

| Characteristic | GSE20194 | GSE20271 | GSE22093 | GSE23988 | GSE25066 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n | 278 | 178 | 103 | 61 | 508 |

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 52.0±10.8 | 51.0±10.7 | 49.0±11.1 | 48.7±9.1 | 49.8±10.5 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 176 | 81 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Black | 29 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 18 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hispanic | 42 | 83 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 10 | 0 | 103 | 61 | 508 |

| T stage, n | |||||

| T0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| T1 | 23 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 30 |

| T2 | 147 | 76 | 51 | 20 | 255 |

| T3 | 50 | 37 | 26 | 40 | 145 |

| T4 | 53 | 51 | 18 | 0 | 75 |

| Unknown | 2 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| N stage, n | |||||

| N0 | 79 | 59 | 21 | 21 | 157 |

| N1 | 125 | 71 | 16 | 32 | 244 |

| N2 | 31 | 38 | 10 | 5 | 66 |

| N3 | 42 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 41 |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | 52 | 0 | 0 |

| Clinical AJCC stage, n | |||||

| I | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| II | 145 | 82 | 26 | 34 | 272 |

| III | 126 | 92 | 28 | 27 | 228 |

| Unknown | 1 | 2 | 49 | 0 | 0 |

| ER IMH, n | |||||

| Negative | 114 | 80 | 56 | 29 | 205 |

| Positive | 164 | 98 | 42 | 32 | 297 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 |

| PR IMH, n | |||||

| Negative | 157 | 95 | 0 | 0 | 258 |

| Positive | 121 | 83 | 0 | 0 | 243 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 103 | 61 | 7 |

| HER2, n | |||||

| Negative | 219 | 152 | 0 | 0 | 489 |

| Positive | 59 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 103 | 61 | 13 |

| Nuclear grade, n | |||||

| G1 | 13 | 15 | 3 | 1 | 32 |

| G2 | 104 | 61 | 29 | 19 | 180 |

| G3 | 150 | 72 | 47 | 37 | 259 |

| Unknown | 11 | 30 | 24 | 4 | 37 |

| PAM50 subtype, n | |||||

| LumA | 73 | 41 | 25 | 10 | 143 |

| LumB | 89 | 61 | 28 | 17 | 147 |

| HER2-enriched | 35 | 21 | 3 | 2 | 41 |

| Basal | 69 | 42 | 44 | 30 | 160 |

| Normal | 12 | 13 | 3 | 2 | 17 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pathologic response, n | |||||

| RD | 222 | 152 | 69 | 41 | 389 |

| PCR | 56 | 26 | 28 | 20 | 99 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 20 |

T, tumor; N, node; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; IMH, immunohistochemistry; LumA, luminal subtype A; LumB, luminal subtype B; Basal, basal-like subtype; Normal, normal breast-like subtype; RD, residual disease; PCR, pathological complete response.

Associations between CENP gene expression levels and the clinicopathological characteristics of patients with breast cancer

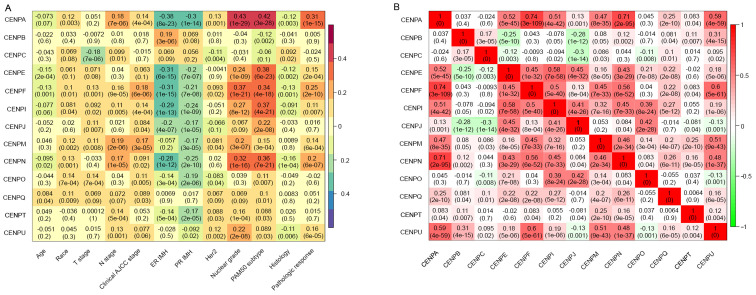

In the training dataset, the associations between 13 CENP genes and patient clinicopathological characteristics related to breast cancer were analyzed (Fig. 1A). The results demonstrated that CENPA was significantly associated with pathological response, nuclear grade and PAM50 subtype. In addition, high CENPA expression levels were associated with low levels of ER and PR expression. Similar results were observed for CENPE, CENPF, CENPI, CENPJ and CENPN. Therefore, we hypothesized that CENPA, CENPE, CENPF, CENPI, CENPJ and CENPN were likely to be co-expressed. By contrast, the associations between CENPB, CENPC, CENPM, CENPO, CENPQ, CENPT and CENPU and patient clinicopathological characteristics were less notable.

Figure 1.

CENP gene expression and co-expression levels. (A) Association between CENP gene expression levels and clinicopathological characteristics of patients in the training dataset. (B) Co-expression analysis of CENP genes. CENP, centromere protein; T, tumor; N, node; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; IMH, immunohistochemistry.

Co-expression analysis of CENPs

To assess the potential co-expression relationships among the 13 CENP genes, the co-expression of 13 CENP genes was analyzed (Fig. 1B). The results demonstrated that CENPA expression levels were positively correlated with those of CENPE, CENPF, CENPI, CENPN and CENPU. Additionally, a rectangular positive correlation cluster was observed from CENPE to CENPQ. Significant positive correlations were also identified among the expression levels of CENPU, CENPF and CENPM.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of CENP gene expression levels

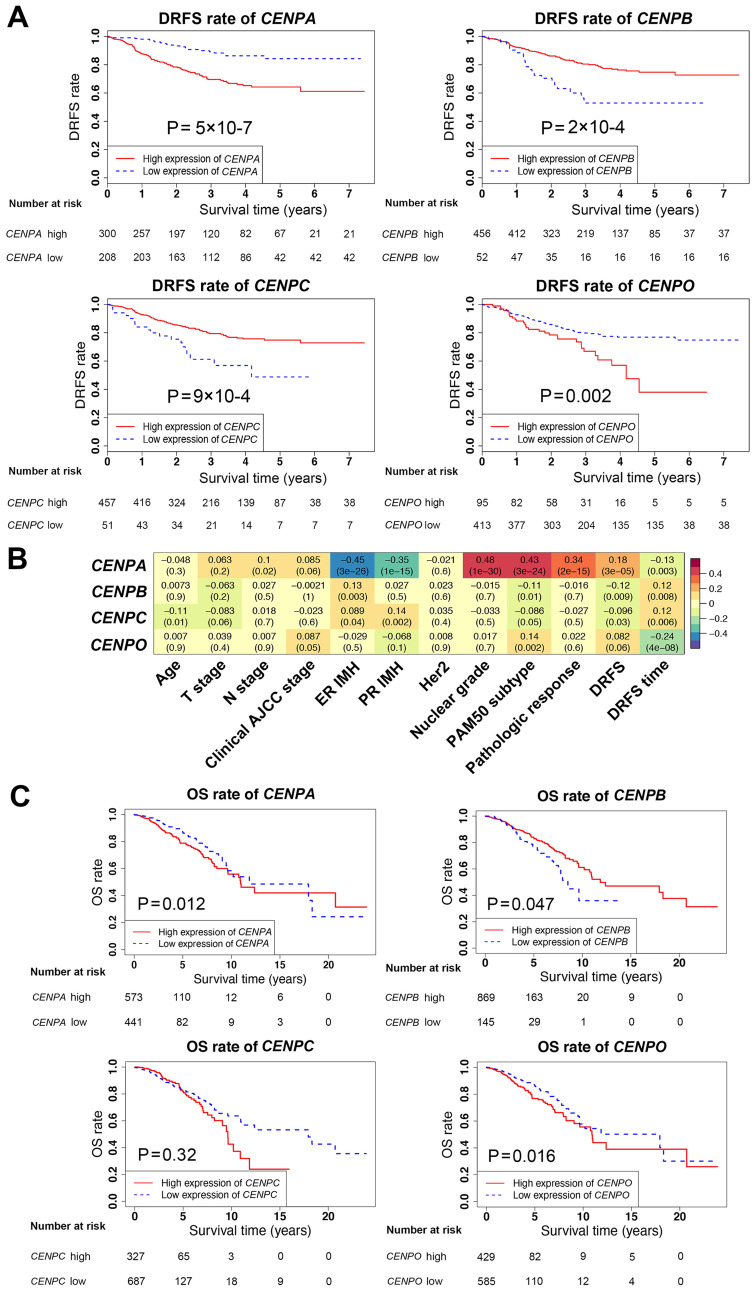

Univariate and multivariate analyses of all CENP genes associated with survival were next performed in the validation dataset (Table II). In the univariate analysis, with the exception of CENPM, CENPQ, CENPT and CENPU, the expression levels of CENP genes significantly affected patient survival. However, in the multivariate analysis, only CENPA, CENPB, CENPC and CENPO were independent prognostic factors for survival. In addition, compared with the low CENP gene expression groups, the DRFS rates were decreased when the expression levels of CENPA and CENPO were high, and increased when the levels of CENPB and CENPC were high (Fig. 2A and C), suggesting that CENPB and CENPC may serve protective roles in breast cancer.

Table II.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of the association between patient survival and CENP gene expression in the validation dataset.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| CENPA | 1.926 (1.426–2.600) | <0.001 | 2.041 (1.494–2.788) | <0.001 |

| CENPB | 0.470 (0.277–0.796) | 0.005 | 0.459 (0.272–0.773) | 0.003 |

| CENPC | 0.317 (0.131–0.762) | 0.010 | 0.347 (0.143–0.842) | 0.019 |

| CENPE | 1.975 (1.373–2.839) | <0.001 | ||

| CENPF | 2.094 (1.396–3.140) | <0.001 | ||

| CENPI | 3.917 (1.943–7.896) | <0.001 | ||

| CENPJ | 3.694 (1.851–7.373) | <0.001 | ||

| CENPM | 1.432 (0.942–2.175) | 0.093 | ||

| CENPN | 2.031 (1.327–3.111) | 0.001 | ||

| CENPO | 3.321 (1.343–8.212) | 0.009 | 3.363 (1.307–8.653) | 0.012 |

| CENPQ | 1.118 (0.377–3.322) | 0.840 | ||

| CENPT | 0.902 (0.560–1.453) | 0.671 | ||

| CENPU | 1.099 (0.925–1.307) | 0.284 | ||

CENP, centromere protein; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Survival analysis and associations between CENPA, CENPB, CENPC and CENPO expression levels and patient clinicopathological characteristics. (A) DRFS rates in patients with high or low expression of CENPA, CENPB, CENPC and CENPO using Kaplan-Meier analysis in the validation dataset. (B) Associations between CENPA, CENPB, CENPC and CENPO expression levels and clinicopathological characteristics in the validation dataset. (C) OS rates in patients with high or low expression levels of CENPA, CENPB, CENPC and CENPO using Kaplan-Meier analysis in The Cancer Genome Atlas database. DRFS, distant relapse-free survival; CENP, centromere protein; OS, overall survival.

To further determine the associations between the CENPA, CENPB, CENPC and CENPO gene expression levels and the clinicopathological characteristics of patients in the training and validation datasets, correlation analysis was performed (Fig. 2B). The results demonstrated that the associations between the CENPA, CENPB, CENPC and CENPO gene expression levels and patient clinicopathological characteristics were similar in the training and validation datasets. Although survival data in the training dataset were lacking, based on these findings, the effects of CENPA, CENPB, CENPC and CENPO on survival were estimated to be similar between the training and validation datasets, since the survival data in the validation dataset were clear. The survival analysis was further validated using TCGA database, which revealed that CENPA, CENPB and CENPO exerted the same effects on patient survival rates as those observed in the GEO validation dataset (Fig. 2C). Notably, in TCGA database, the results for CENPC did not match those in the GEO data; however, this difference was not statistically significant.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of CENP gene expression levels and patient clinicopathological characteristics

As a number of CENP genes were significantly associated with patient clinicopathological characteristics, these characteristics were included in the univariate and multivariate analyses in order to elucidate whether they may replace the indicative function of CENP genes and affect patient survival, and to confirm whether the identified CENP genes were independent predictors of survival. First, patient clinicopathological characteristics were analyzed (Table III), and multivariate analysis these characteristics and CENP gene expression levels was subsequently performed (Table IV). The results demonstrated that only the node (N) stage, PAM50 subtype, pathological response and CENPA expression levels were independent factors affecting the survival of patients with breast cancer.

Table III.

Univariate analysis of the association between patient clinicopathological characteristics and survival in the validation dataset.

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.998 (0.981–1.016) | 0.860 |

| T stage | ||

| T0 | 1 (ref) | <0.001 |

| T1 | 0.139 (0.027–0.723) | 0.019 |

| T2 | 0.149 (0.036–0.617) | 0.009 |

| T3 | 0.204 (0.049–0.856) | 0.030 |

| T4 | 0.440 (0.105–1.850) | 0.263 |

| N stage | ||

| N0 | 1 (ref) | <0.001 |

| N1 | 2.378 (1.381–4.095) | 0.002 |

| N2 | 4.432 (2.364–8.311) | <0.001 |

| N3 | 4.548 (2.265–9.133) | <0.001 |

| Clinical AJCC stage | ||

| I | 1 (ref) | <0.001 |

| II | 0.643 (0.155–2.669) | 0.544 |

| III | 1.562 (0.381–6.405) | 0.536 |

| ER IMH | 0.344 (0.234–0.507) | <0.001 |

| PR IMH | 0.380 (0.252–0.571) | <0.001 |

| HER2 | 1.752 (0.432–7.107) | 0.433 |

| Nuclear grade | ||

| G1 | 1 (ref) | 0.038 |

| G2 | 7.018 (0.961–51.232) | 0.055 |

| G3 | 9.466 (1.313–68.249) | 0.026 |

| PAM50 subtype | ||

| LumA | 1 (ref) | <0.001 |

| LumB | 1.434 (0.691–2.977) | 0.333 |

| HER2-enriched | 3.280 (1.579–6.812) | 0.001 |

| Basal | 3.975 (2.356–6.706) | <0.001 |

| Normal | 0.828 (0.280–2.449) | 0.734 |

| Pathologic response | 0.257 (0.120–0.554) | 0.001 |

T, tumor; N, node; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; IMH, immunohistochemistry; LumA, luminal subtype A; LumB, luminal subtype B; Basal, basal-like subtype; Normal, normal breast-like subtype; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table IV.

Multivariate analysis of patient clinicopathological characteristics and CENPA expression levels in the validation dataset.

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| N stage | ||

| N0 | 1 (ref) | <0.001 |

| N1 | 2.848 (1.550–5.236) | 0.001 |

| N2 | 4.995 (2.508–9.948) | <0.001 |

| N3 | 4.016 (1.868–8.636) | <0.001 |

| PAM50 subtype | ||

| LumA | 1 (ref) | <0.001 |

| LumB | 1.169 (0.525–2.603) | 0.703 |

| HER2-enriched | 2.105 (0.880–5.038) | 0.095 |

| Basal | 3.665 (1.884–7.128) | <0.001 |

| Normal | 0.968 (0.322–2.907) | 0.094 |

| Pathologic response | 0.094 (0.037–0.237) | <0.001 |

| CENPA | 1.605 (1.000–2.576) | 0.050 |

N, node; LumA, luminal subtype A; LumB, luminal subtype B; Basal, basal-like subtype; Normal, normal breast-like subtype; CENPA, centromere protein A; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

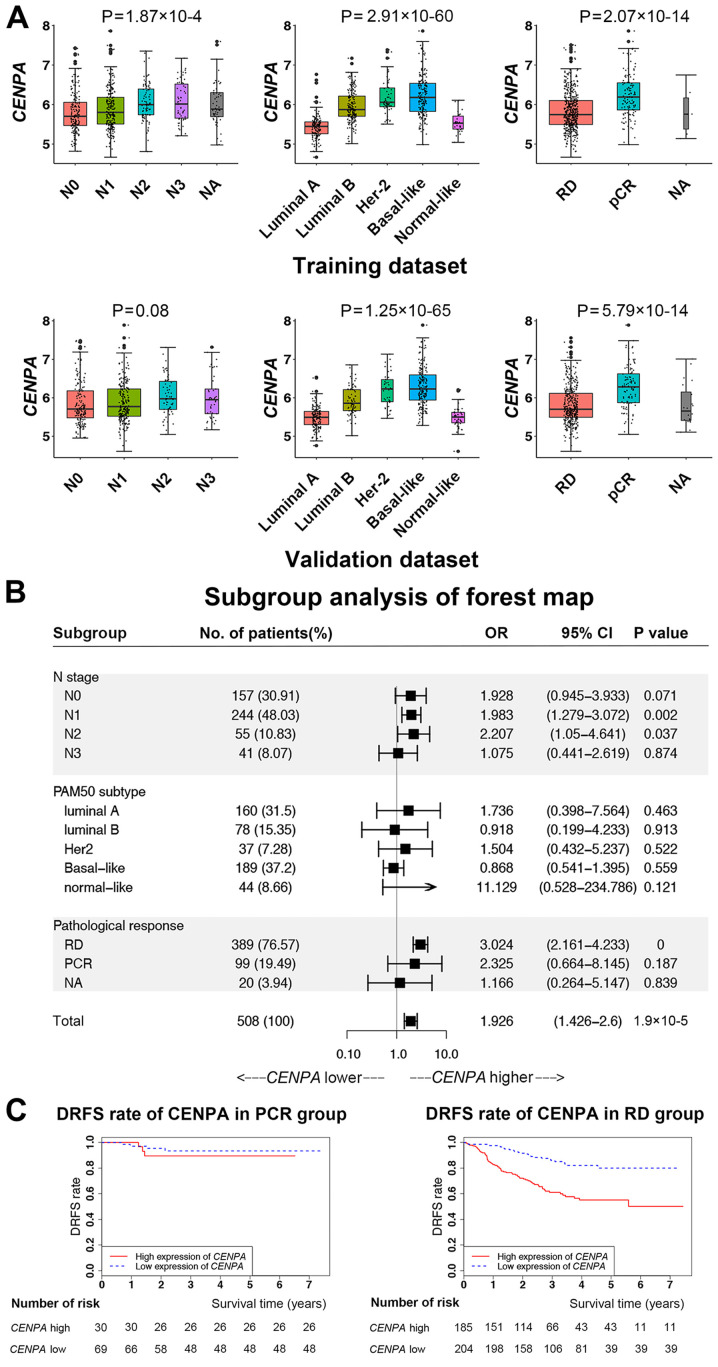

Subgroup analysis

Since CENPA was identified as an independent factor for patient survival, further analysis of its expression levels was performed in patient subgroups categorized by the other three independent factors (Fig. 3A). Similar results were obtained in the training and validation datasets. As the N stage increased, CENPA expression levels significantly increased. Among the PAM50 subtypes, the CENPA expression levels in luminal B, HER2-enriched and basal-like subtypes were significantly higher compared with those in luminal A and normal breast-like subtypes. In the pathological response subgroups, the expression levels of CENPA in the PCR group were higher compared with those in the RD group.

Figure 3.

CENPA expression in patient subgroups and survival analysis. (A) CENPA expression in patient subgroups according to N stage, PAM50 subtype and pathological response in the training and validation datasets. (B) Subgroup analysis of survival by forest plot. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis according to CENPA expression levels in the RD and PCR subgroups. CENPA, centromere protein A; PCR, pathological complete response; RD, residual disease; N, node; DRFS, distant relapse-free survival; NA, not available.

The specific subgroups that affected the survival of patients with breast cancer according to CENPA expression levels were determined by performing additional subgroup analysis (Fig. 3B). The results demonstrated that CENPA expression levels significantly affected the survival of patients with chemotherapy responses in the RD group, but not in the PCR group (Fig. 3C).

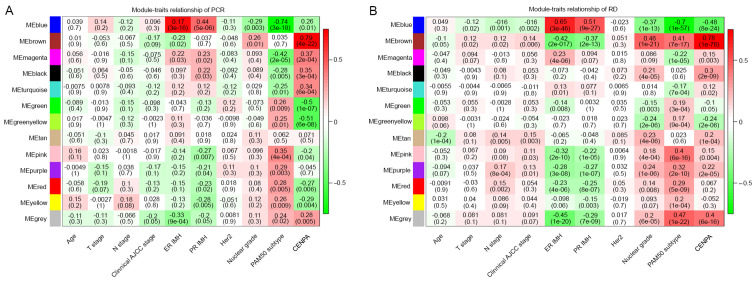

Co-expression analysis of CENPA

To determine how CENPA affected the survival of patients with RD after chemotherapy, co-expression analysis of CENPA was performed using WGCNA (Fig. 4). The results demonstrated that the brown module in the PCR and RD groups was positively correlated with CENPA expression levels. However, no significant differences were observed in the correlations between the brown module and CENPA expression levels in the two groups (Table V). By contrast, the green module (Supplementary data) was significantly negatively correlated with CENPA levels in the PCR group and slightly negatively correlated with those in the RD group; the correlation between the two groups was significant (P=0.0001; Table V). In addition, the green-yellow, pink and red modules also exhibited significant differences between the two groups (P<0.01; Table V).

Figure 4.

Weighted correlation network analysis plot. (A) Associations between gene modules and clinicopathological characteristics of patients in the PCR group. (B) Associations between gene modules and clinicopathological characteristics of patients in the RD group. CENP, centromere protein; RD, PCR, pathological complete response; RD, residual disease; T, tumor; N, node; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; IMH, immunohistochemistry.

Table V.

Comparative analysis of the correlation between each module and expression of centromere protein A in the pathological complete response and residual disease groups in the training and validation datasets.

| Module | Z statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Blue | −2.2523 | 0.0243 |

| Brown | −0.2285 | 0.8193 |

| Magenta | −2.0805 | 0.0375 |

| Black | −0.4904 | 0.6239 |

| Turquoise | −2.0475 | 0.0406 |

| Green | 3.9366 | 0.0001 |

| Green-yellow | 2.7879 | 0.0053 |

| Tan | 1.1540 | 0.2485 |

| Pink | 3.1028 | 0.0019 |

| Purple | 2.3559 | 0.0185 |

| Red | 3.0159 | 0.0026 |

| Yellow | 2.1615 | 0.0307 |

| Gray | 1.1922 | 0.2332 |

Enrichment analysis

To further explain how CENPA affected the survival of patients who underwent chemotherapy, enrichment analysis of signaling pathways was performed using the green module (Fig. 5A). The results revealed that the green module was mainly enriched in three pathways: ‘ECM-receptor interaction’, ‘focal adhesion’ and ‘PI3K-Akt signaling pathway’. Therefore, the present study focused on three key genes in this pathway: PI3K catalytic subunit α (PIK3CA), AKT1 and MTOR (23) (Fig. 5B). In the PCR and RD groups, the median CENPA expression levels were used to define whether CENPA was highly or lowly expressed. The results demonstrated that when CENPA was highly expressed, the expression levels of PIK3CA were also high in the PCR and RD groups. However, compared with the low CENPA expression group, MTOR expression levels were significantly decreased in the PCR group but not altered in the RD group when CENPA was highly expressed; this result was also validated using TCGA data (Fig. 5C). Since the CCR group in TCGA validation dataset included not only patients with PCR but also with RD, the difference was not statistically significant. In the RD group in TCGA data, due to the limited number of patient samples (n=18), the results did not exhibit accordance with those in the GEO datasets; however, a similar trend was observed.

Figure 5.

KEGG enrichment analysis and expression levels of PIK3CA, AKT1 and MTOR. (A) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the green module. (B) Gene expression levels of PIK3CA, AKT1 and MTOR based on CENPA expression in the PCR and RD groups in the Gene Expression Omnibus data. (C) Gene expression levels of PIK3CA, AKT1 and MTOR based on CENPA expression in the CCR and RD groups in data from The Cancer Genome Atlas. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; PIK3CA, PI3K catalytic subunit α; CENPA, centromere protein A; PCR, pathological complete response; RD, residual disease; CCR, clinical complete response.

Discussion

The crucial factor affecting the success of breast cancer treatment is systemic therapy, particularly chemotherapy. CENPs are proteins that facilitate centromere formation during mitosis; the majority of chemotherapeutic drugs kill cancer cells by affecting or disrupting mitosis (24). Therefore, the expression of specific CENP genes may affect the chemotherapy responses and patient prognosis. Among patients with ER-positive breast cancer who received no systemic therapy or tamoxifen, high levels of CENPA were associated with low 5-year survival rates and were positively correlated with Ki-67 expression levels (25). In addition, CENPO is required for bipolar mitotic spindle assembly and segregation of chromosome during mitosis; CENPO expression regulates gastric cancer cell proliferation and is associated with poor patient prognosis (26,27). By contrast, certain genes in the CENP family encode proteins associated with mitosis stabilization and may therefore improve patient prognosis. CENPB supports kinetochore formation and contributes to the maintenance of chromosome segregation fidelity (8). In mitosis, CENPC serves as a scaffold for the specific recruitment of essential kinetochore proteins and links centromeres and kinetochores (9). The results of the present study demonstrated that high expression levels of CENPB and CENPC were associated with a favorable prognosis in patients with breast cancer.

In the present study, high PCR rates of patients with breast cancer were observed when the majority of CENP genes were highly expressed. In addition, CENPA was identified as an independent factor affecting survival, particularly in patients presenting with RD following chemotherapy. Notably, genes co-expressed with CENPA were mainly associated with cell division. However, in the PCR and RD groups, no significant differences were observed in the correlation between CENPA expression levels and the cell division pathway, suggesting that CENPA affected survival through a different pathway. Furthermore, the correlations between the green module and CENPA expression levels in the PCR and RD groups were significantly different. Additionally, since the ‘PI3K-Akt signaling pathway’ was among the main enriched pathways in the green module, we hypothesized that the chemotherapy response and prognosis may be associated with the combination of CENPA expression and the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway.

Enhanced centromere function and mitosis are associated with high expression levels of CENPA, which is particularly notable in human cancer cells (7). Studies using RNA sequence data from the Oncomine database have revealed a significant positive correlation between high CENPA expression and chemotherapy response (using taxane as the main drug) (28). In addition, a previous study has demonstrated a strong correlation between high levels of CENPA expression and a positive oncolytic response to chemotherapy using Oncomine, which indicates that high CENPA expression levels may be used as a predictive biomarker for a positive outcome of taxane-based chemotherapy for breast cancer (29). The results of the present study also demonstrated that when CENPA was highly expressed, the PCR rates increased, suggesting that the response to chemotherapy may have been enhanced. Thus, we hypothesized that high levels of mitotic activity in response to high CENPA expression levels may lead to active cell proliferation, which may enhance the chemotherapy response of tumors.

Since chemotherapy functions by inhibiting mitosis (3), in which CENPA serves a crucial role, we hypothesized that tumors may be highly sensitive to chemotherapy when CENPA is expressed at high levels, and the survival rate of patients with high CENPA expression levels may also be higher compared with that of patients with low CENPA levels. A previous study has demonstrated that high CENPA expression levels in colon cancer is associated with a favorable relapse-free survival rate (29). By contrast, the results of the present study demonstrated that the survival rates were lower in patients with high CENPA expression levels compared with those in patients with low CENPA levels. Similar results have been observed in other types of cancers, including osteosarcoma (30,31), lung adenocarcinoma (32) and ovarian cancer (33). Specifically, the survival times of patients in the high CENPA expression group were significantly lower compared with those in patients in the low CENPA expression group in patients with osteosarcoma. Additionally, the survival time of patients with lung adenocarcinoma in the high CENPA expression group was <120 months (32). Another study demonstrated that CENPA was highly expressed in ovarian epithelial cancer and was associated with poor survival (33). In addition, in a study of breast cancer, high expression levels of CENPA were also associated with poor survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer (34). To further validate these results, the present study divided the patients into groups based on RD or PCR following chemotherapy. The results of this analysis demonstrated that in the RD group, the DRFS rate was low when CENPA was highly expressed; by contrast, CENPA expression levels exerted no significant effects on the survival of patients in the PCR group. Therefore, other mechanisms may mediate the decreased survival when CENPA is highly expressed in patients whose tumors present with PCR following chemotherapy.

In the present study, WGCNA was performed to analyze the genes associated with CENPA expression in the PCR and RD groups. The KEGG results demonstrated that genes co-expressed with CENPA were mainly enriched in cell cycle-associated pathways, including cell division cycle, nuclear division cycle, and cell cycle phase transition (35). These results suggested that the mitosis pathway may be the key to determining the effects of CENPA on survival. There were no significant differences in the correlations between the mitosis pathways and the RD group, which indicated that CENPA did not affect survival by synergizing with the hub genes in this module. The green module and CENPA were significantly negatively correlated in the PCR group, and there was a statistically significant difference between the PCR and RD groups, suggesting that genes in the green module may be associated with tumor progression.

Further analysis in the present study revealed that the main pathways enriched in the green module genes were ‘focal adhesion’, ‘ECM-receptor interaction’ and ‘PI3K-Akt signaling pathway’. The focal adhesion pathway is primarily associated with cancer cell migration (36). Focal adhesion kinase is a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase and a key regulator of the focal adhesion complex, which mediates various intracellular processes, such as cell motility, invasiveness, proliferation and viability (36,37). Signals of the extracellular matrix (ECM) modulate cell behavior, cell interactions in forming tissues and homeostasis (38). Various components of the ECM provide cells with a scaffold that controls and determines cell shape, mobility, proliferation, viability and differentiation (38). Previous studies have demonstrated that dysregulation of the ECM components causes cancer cell invasion and progression (39–41).

The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway serves important roles in the development and treatment of breast cancer (42). It is associated with the cell cycle and affects cell proliferation, viability, differentiation and proliferation (43). Upregulation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway promotes cell proliferation, migration, survival and angiogenesis (44). In addition, in response to a variety of intracellular and extracellular stimuli, such as metabolic molecules, growth factors and hypoxia, the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway regulates intracellular metabolism, cell cycle progression, angiogenesis and tumor aggressiveness (45). Therefore, a large number of breast cancer cases are associated with the activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, which promotes stable survival and invasion of breast cancer cells, leading to metastasis (46). Currently, inhibitors of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, such as sirolimus, temsirolimus and everolimus, demonstrate promising preclinical activity for the treatment of breast cancer (47,48). Therefore, we hypothesize that in patients presenting with RD, tumor cell mitosis may be activated when CENPA is expressed at high levels, and upregulation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway may promote stable survival in activated tumor cells without being affected by chemotherapy drugs, leading to poor survival. Additionally, the results of the present study demonstrated that in the PCR group, despite the high expression levels of CENPA, the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway was not significantly activated, resulting in sufficient sensitivity to chemotherapy.

One limitation of the present study was that the chemotherapy response or resistance were not evaluated in cultured cells in order to verify that the effects of CENPA synergized with the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. However, the present study used multiple databases for validation and demonstrated that the CENPA levels and chemotherapy responses may be promising indicators to predict the survival of patients with breast cancer.

In summary, the results of the present study demonstrated that CENPA affected the chemotherapy responses and prognosis of patients with breast cancer. In patients whose tumors presented with RD following chemotherapy, the DRFS rate was significantly decreased when CENPA was expressed at high levels. These effects may be associated with the upregulation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in these patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by The Science and Technology Department (Sichuan, China; grant nos. 2019YFH0146 and 2020YFS0199) and The Health Commission of Sichuan Province (Grant Research Project on Healthcare in Sichuan Province, grant no. 2019-107).

Funding

This study was supported by The Science and Technology Department (Sichuan, China; grant nos. 2019YFH0146 and 2020YFS0199) and The Health Commission of Sichuan Province (Grant Research Project on Healthcare in Sichuan Province, grant no. 2019-107).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

ZD and QL proposed the study concept and design. SZ and YX performed the experiments and acquired the data. SZ and NW analyzed and interpreted the data. SZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript and critically revised it for important intellectual content. YZ, JQ, QY, TT and LX analyzed the data and produced the figures. SZ supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owrang M, Copeland RL, Jr, Ricks-Santi LJ, Gaskins M, Beyene D, Dewitty RL, Jr, Kanaan YM. Breast cancer prognosis for young patients. In Vivo. 2017;31:661–668. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan L, Strasser-Weippl K, Li JJ, St Louis J, Finkelstein DM, Yu KD, Chen WQ, Shao ZM, Goss PE. Breast cancer in China. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e279–e289. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson MK, Matey L. Overview of cancer and cancer treatment. In: Olsen MM, LeFebvre KB, Brassil KJ, editors. Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy Guidelines and Recommendations for Practice. Oncology Nursing Society; Pittsburgh, PA: 2019. pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu LY, Wang F, Yu LX, Ma ZB, Zhang Q, Gao DZ, Li YY, Li L, Zhao ZT, Yu ZG. Breast cancer awareness among women in Eastern China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1004. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaufmann SH, Earnshaw WC. Induction of apoptosis by cancer chemotherapy. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256:42–49. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoda K, Ando S, Morishita S, Houmura K, Hashimoto K, Takeyasu K, Okazaki T. Human centromere protein A (CENP-A) can replace histone H3 in nucleosome reconstitution in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7266–7271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130189697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fachinetti D, Han JS, McMahon MA, Ly P, Abdullah A, Wong AJ, Cleveland DW. DNA Sequence-specific binding of CENP-B enhances the fidelity of human centromere function. Dev Cell. 2015;33:314–327. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka K, Chang HL, Kagami A, Watanabe Y. CENP-C functions as a scaffold for effectors with essential kinetochore functions in mitosis and meiosis. Dev Cell. 2009;17:334–343. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Popovici V, Chen W, Gallas BG, Hatzis C, Shi W, Samuelson FW, Nikolsky Y, Tsyganova M, Ishkin A, Nikolskaya T, et al. Effect of training-sample size and classification difficulty on the accuracy of genomic predictors. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R5. doi: 10.1186/bcr2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi L, Campbell G, Jones WD, Campagne F, Wen Z, Walker SJ, Su Z, Chu TM, Goodsaid FM, Pusztai L, et al. The MicroArray quality control (MAQC)-II study of common practices for the development and validation of microarray-based predictive models. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:827–838. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tabchy A, Valero V, Vidaurre T, Lluch A, Gomez H, Martin M, Qi Y, Barajas-Figueroa LJ, Souchon E, Coutant C, et al. Evaluation of a 30-gene paclitaxel, fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy response predictor in a multicenter randomized trial in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5351–5361. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwamoto T, Bianchini G, Booser D, Qi Y, Coutant C, Shiang CY, Santarpia L, Matsuoka J, Hortobagyi GN, Symmans WF, et al. Gene pathways associated with prognosis and chemotherapy sensitivity in molecular subtypes of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:264–272. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Itoh M, Iwamoto T, Matsuoka J, Nogami T, Motoki T, Shien T, Taira N, Niikura N, Hayashi N, Ohtani S, et al. Estrogen receptor (ER) mRNA expression and molecular subtype distribution in ER-negative/progesterone receptor-positive breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;143:403–409. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2763-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatzis C, Pusztai L, Valero V, Booser DJ, Esserman L, Lluch A, Vidaurre T, Holmes F, Souchon E, Wang H, et al. A genomic predictor of response and survival following taxane-anthracycline chemotherapy for invasive breast cancer. JAMA. 2011;305:1873–1881. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colomer R, Aranda-Lopez I, Albanell J, García-Caballero T, Ciruelos E, López-García MÁ, Cortés J, Rojo F, Martín M, Palacios-Calvo J. Biomarkers in breast cancer: A consensus statement by the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology and the Spanish Society of Pathology. Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20:815–826. doi: 10.1007/s12094-018-1909-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JY, Lim JE, Jung HH, Cho SY, Cho EY, Lee SK, Yu JH, Lee JE, Kim SW, Nam SJ, et al. Validation of the new AJCC eighth edition of the TNM classification for breast cancer with a single-center breast cancer cohort. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;171:737–745. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4858-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker JS, Mullins M, Cheang MC, Leung S, Voduc D, Vickery T, Davies S, Fauron C, He X, Hu Z, et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1160–1167. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gendoo DM, Ratanasirigulchai N, Schroder MS, Paré L, Parker JS, Prat A, Haibe-Kains B. Genefu: An R/Bioconductor package for computation of gene expression-based signatures in breast cancer. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:1097–1099. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.R Core Team (2014), corp-author R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna: R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maag JL. gganatogram: An R package for modular visualisation of anatograms and tissues based on ggplot2. F1000Res. 2018;7:1576. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.16409.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Godone RL, Leitao GM, Araujo NB, Castelletti CH, Lima-Filho JL, Martins DB. Clinical and molecular aspects of breast cancer: Targets and therapies. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;106:14–34. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bloom K, Costanzo V. Centromere Structure and Function. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2017;56:515–539. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-58592-5_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGovern SL, Qi Y, Pusztai L, Symmans WF, Buchholz TA. Centromere protein-A, an essential centromere protein, is a prognostic marker for relapse in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R72. doi: 10.1186/bcr3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao Y, Xiong J, Li Z, Zhang G, Tu Y, Wang L, Jie Z. CENPO expression regulates gastric cancer cell proliferation and is associated with poor patient prognosis. Mol Med Rep. 2019;20:3661–3670. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2019.10624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu C, Guo Z, Zhao C, Zhang X, Wang Z. Potential mechanism and drug candidates for sepsis-induced acute lung injury. Exp Ther Med. 2018;15:4689–4696. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Athwal RK, Walkiewicz MP, Baek S, Fu S, Bui M, Camps J, Ried T, Sung MH, Dalal Y. CENP-A nucleosomes localize to transcription factor hotspots and subtelomeric sites in human cancer cells. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2015;8:2. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun X, Clermont PL, Jiao W, Helgason CD, Gout PW, Wang Y, Qu S. Elevated expression of the centromere protein-A(CENP-A)-encoding gene as a prognostic and predictive biomarker in human cancers. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:899–907. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu R, Zhang W, Liu ZQ, Zhou HH. Associating transcriptional modules with colon cancer survival through weighted gene co-expression network analysis. BMC Genomics. 2017;18:361. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3761-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gu XM, Fu J, Feng XJ, Huang X, Wang SM, Chen XF, Zhu MH, Zhang SH. Expression and prognostic relevance of centromere protein A in primary osteosarcoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2014;210:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang XR, Xiong Y, Duan H, Gong RR. Identification of genes associated with methotrexate resistance in methotrexate-resistant osteosarcoma cell lines. J Orthop Surg Res. 2015;10:136. doi: 10.1186/s13018-015-0275-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu WT, Wang Y, Zhang J, Ye F, Huang XH, Li B, He QY. A novel strategy of integrated microarray analysis identifies CENPA, CDK1 and CDC20 as a cluster of diagnostic biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2018;425:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiu JJ, Guo JJ, Lv TJ, Jin HY, Ding JX, Feng WW, Zhang Y, Hua KQ. Prognostic value of centromere protein-A expression in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:2971–2975. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0860-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang C, Han Y, Huang H, Min L, Qu L, Shou C. Integrated analysis of expression profiling data identifies three genes in correlation with poor prognosis of triple-negative breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 2014;44:2025–2033. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao X, Guan JL. Focal adhesion kinase and its signaling pathways in cell migration and angiogenesis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63:610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alfieri R, Giovannetti E, Bonelli M, Cavazzoni A. New treatment opportunities in phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)-deficient tumors: Focus on PTEN/Focal adhesion kinase pathway. Front Oncol. 2017;7:170. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lukashev ME, Werb Z. ECM signalling: Orchestrating cell behaviour and misbehaviour. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:437–441. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(98)01362-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huan JL, Gao X, Xing L, Qin XJ, Qian HX, Zhou Q, Zhu L. Screening for key genes associated with invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast via microarray data analysis. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13:7919–7925. doi: 10.4238/2014.September.29.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwertfeger KL, Cowman MK, Telmer PG, Turley EA, McCarthy JB. Hyaluronan, inflammation, and breast cancer progression. Front Immunol. 2015;6:236. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tolg C, McCarthy JB, Yazdani A, Turley EA. Hyaluronan and RHAMM in wound repair and the ‘cancerization’ of stromal tissues. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:103923. doi: 10.1155/2014/103923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paplomata E, O'Regan R. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in breast cancer: Targets, trials and biomarkers. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2014;6:154–166. doi: 10.1177/1758834014530023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ersahin T, Tuncbag N, Cetin-Atalay R. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR interactive pathway. Mol Biosyst. 2015;11:1946–1954. doi: 10.1039/C5MB00101C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKenna M, McGarrigle S, Pidgeon GP. The next generation of PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway inhibitors in breast cancer cohorts. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2018;1870:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Corti F, Nichetti F, Raimondi A, Niger M, Prinzi N, Torchio M, Tamborini E, Perrone F, Pruneri G, Di Bartolomeo M, et al. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in biliary tract cancers: A review of current evidences and future perspectives. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;72:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McAuliffe PF, Meric-Bernstam F, Mills GB, Gonzalez-Angulo AM. Deciphering the role of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in breast cancer biology and pathogenesis. Clin Breast Cancer. 2010;10(Suppl 3):S59–S65. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2010.s.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.LoRusso PM. Inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway in Solid Tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3803–3815. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee JJ, Loh K, Yap YS. PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibitors in breast cancer. Cancer Biol Med. 2015;12:342–354. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2015.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.