Highlights

-

•

Brain abscess in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome is extremely rare.

-

•

It’s is important to understand and prevent this potentially fatal syndrome.

-

•

Perioperative management is an important steps.

-

•

Long-term targeted antibiotic therapy can minimize the risk of abscess recurrence.

-

•

During surgery, we recommend ensuring that intraoperative blood loss is minimized.

Abbreviations: VSD, ventricular septal defect; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography; ICU, intensive care unit; CRKP, carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumonia

Keywords: Brain abscess, Ventricular septal defect, Eisenmenger syndrome, Pulmonary hypertension

Abstract

Introduction and importance

Brain abscess is a potentially fatal neurological infection, despite the development of new antimicrobial agents and modern neurosurgical techniques.

Case presentation

We present an uncommon case where a large brain abscess was treated successfully in a patient with Eisenmenger syndrome. He was underwent neurosurgical treatment and eventually recovered.

Clinnical discussion

The etiology of a brain abscess in patients with congenital cyanotic heart disease has multiple aspects. In this patient population was high risk for developing perioperative complications.The preoperative evaluation, intraoperative management and postoperative care are important steps in the treatment of cardiac patients undergoing noncardiac surgery, and essential for patient’s safe and fast recovery.

Conclusions

We highlight the importance of the diagnosis and management of Eisenmenger syndrome to help us further understand this rare and fatal disease.

1. Introduction

Brain abscess is considered as a collection of pus within the brain parenchyma. The pus is formed from a localized area of cerebritis in the capsule, which is well vascularized [1]. Majority of patients, the common causes of the brain abscess are numerous and include a disease of immunocompromised, a history of immunosuppressive medication, destruction of the blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier, or systemic infection. Bacteria enter the brain through contiguous spread and hematogenous dissemination, or some unknown mechanisms [2]. Congenital cyanotic heart disease have been an important risk factor for brain abscess. The most common form was tetralogy of Fallot, followed by ventricular septal defect and transposition of great vessels [3]. However, a brain abscess which occurs in a patient with severe Eisenmenger syndrome is extremely rare. Herein, we report a case of preoperative diagnosed with ventricular septal defects and pulmonary hypertension. In the case of secondary exacerbation of Eisenmenger’s syndrome during the perioperative period, acute cardiopulmonary impairment occurs. This case report has been reported in line with the SCARE 2020 Criteria [4].

2. Case report

A 47-year-old male was referred to our neurosurgery department with a 4-day history of headache and memory decline. Past drug and family histories were not significant. He were seizure-free. Clubbing of fingers and toes were found during physical examination. Past medical history included underwent stereotactic drainage and recovered from a left frontal lobe brain abscess at the age of 36 years.

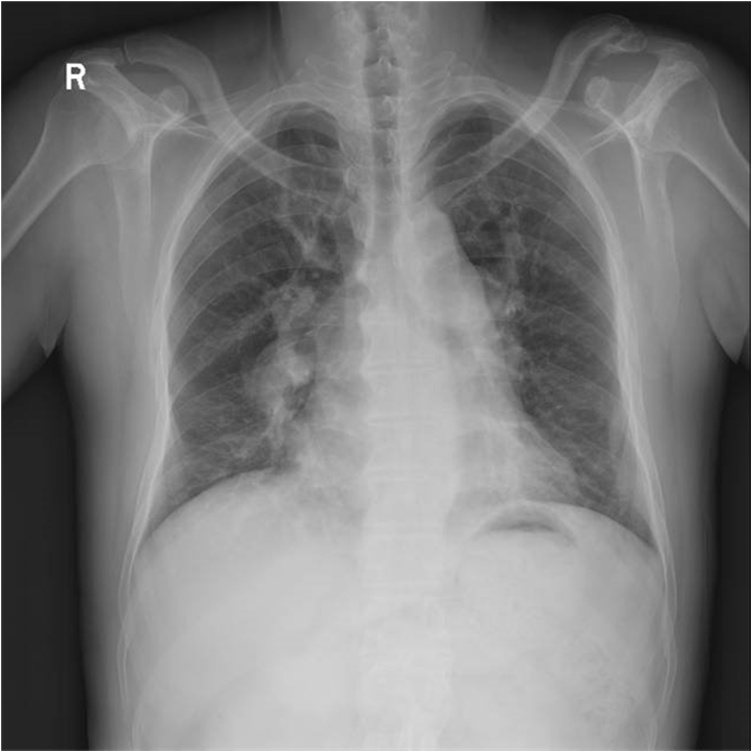

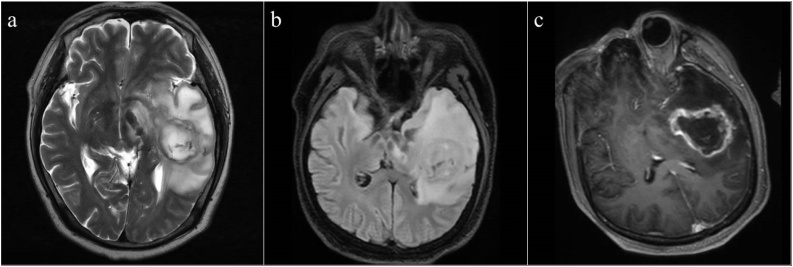

Laboratory studies have shown that neutrophils increased, monocytes increased, mean corpuscular volume and mean corpuscular hemoglobin increased. His other laboratory tests including coagulation profiles, liver and renal function tests, and blood levels of electrolytes were normal. The electrocardiogram showed the normal sinus rhythm, severe right axis deviation and right ventricular hypertrophy. Pre-operative Chest X-ray showed an enlargement of the cardiac silhouette and marked pulmonary vascular congestion (Fig. 1). An echocardiogram was performed, which showed continuous interruption of 21 mm in the direction of 9–12 o'clock in the ventricular septum with bidirectional shunt. Color Doppler imaging showed mild tricuspid regurgitant. This ventricular septal defect with bidirectional shunt and obvious pulmonary hypertension, which consistent with Eisenmenger syndrome. He was diagnosed as a case of ventricular septal defect (VSD) with severe pulmonary hypertension. Subsequent, magnetic resonance images (MRI) of the brain showed heterogeneous high signal intensity in T2and T2 Flair image, and peripherally enhancing lesion in the left temporal lobe which has irregular surrounding edema and a mass effect was found in the postcontrast T1-weight MRI [Fig. 2a–c], and showed a no enhancement lesion in the right frontal lobe [Fig. 2d]. The patient’s headache improved after use of mannitol.

Fig. 1.

Pre-operative Chest X-ray showed an enlargement of the cardiac silhouette and marked pulmonary vascular congestion.

Fig. 2.

Preoperative brain MRI. (a) T2 axial view, (b) T2 flair axial view, (c) T1 enhanced axial view of brain demonstrating a peripherally enhancing lesion (45.5 × 30 mm) in the left temporal lobe with a large range of surrounding edema.

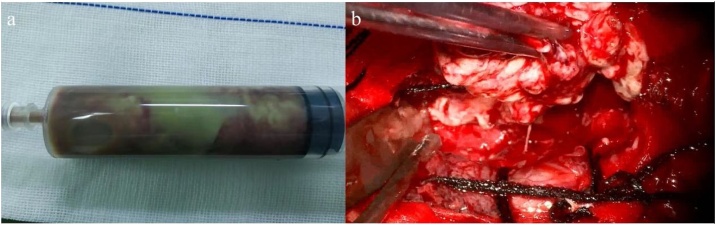

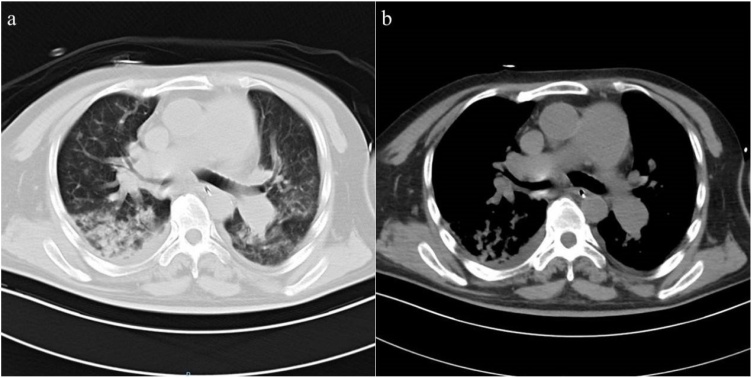

On hospital day six, the patient underwent a left temporal craniotomy and surgical excision of the brain abscess under general anaesthesia. The operation was done by the corresponding author and the first author. Intraoperative support was provided by a multidisciplinary team that includes cardiac and neuroanaesthesia specialists, and closely monitors the patient's hemodynamic parameters through invasive and non-invasive techniques. During the operation, we extracted a sample of 20 ml of purulent material from the capsule was sent for culture [Fig. 3a]. The abscess was completely excised along with its capsule with preservation of the surrounding brain tissue [Fig. 3b]. The purulent material was sent for microbiology analysis. The lesions were completed surgical resection after aspiration decompression and sent for pathological. Aspirated pus cultures were negative for bacteria. However, on the third day after the operation, his neurologic and respiratory functions deteriorated rapidly, and sommolence developed into stupor, accompanied by a decline in oxygen saturation. Repeated head computed tomography (CT) imaging confirmed severe edema at the surgical site, and the midline structure shifted to the right (Fig. 4). At this point, despite the gradual increase in supplemental oxygenation, he began to fever and his hypoxia progressed rapidly. Repeated breast CT imaging showed a bilateral pulmonary and small bilateral pleural effusion (Fig. 5). Meanwhile, the patient also had pulmonary hypertension demonstrated by breast CT. So he underwent tracheotomy for worsening hypoxia and shifted to the ICU for further treatment and observation. Sputum culture showed carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumonia (CRKP) subspecies. The blood culture also showed CRKP subspecies. The patient received combination therapy directed at CRKP-infections, including vancomycin, meropenem and polymyxin B. The neurologic gradually stabilized after abscess continuous drainage and medication therapy. Furthermore, with this information we assessed the repair of ventricular septal defect with cardiovascular surgical, but the lack of appropriate timing did not allow us to determine the best treatment strategy. And the patient developed multidrug-resistant pneumonia and bloodstream infection, so we focused management on drugs that optimize pulmonary hypertension treatment and anti-infection treatment.

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative view. (a) Purulent material (b) Brain abscess after completely excised along with its capsule with preservation of the surrounding brain tissue.

Fig. 4.

Postoperative head CT imaging confirmed severe edema at the surgical site, and the midline structure shifted to the right.

Fig. 5.

Repeated breast CT imaging. (a) Bilateral pulmonary and small bilateral pleural effusion, (b) Pulmonary artery enlargement (inner diameter = 46 mm).

3. Follow-up

On 19 days after the operation, he was transferred to the local hospital to continue treatment, finally complete neurologic recovered following pulmonary rehabilitation and a total antibiotic treatment of 8 weeks.

4. Discussion

The etiology of brain abscess in patients with congenital cyanotic heart disease has the following aspects. In cyanotic heart disease with shunts from right to left bypass, by which blood in the heart not filtered through pulmonary circulation. Therefore, bacteria in the bloodstream cannot filtered through the pulmonary circulation, where they would be removed by phagocytosis under normal circumstances. So this may allow bacteria direct entry to cerebral circulation. Moreover, in these patients, because of severe hypoxemia and metabolic acidosis and increased blood viscosity resulting from compensatory polycythemia, and the brain may also have predisposing conditions such as minute low-perfusion areas, blood flow velocity and a consequent low-perfusion area, lead to this area more prone to infection [5]. The abnormal shunted blood containing of microorganisms may be seeded in such area, forming one or more brain abscess. Meanwhile, this hypothesis implies that we should pay more attention to the other infarction besides the site of the abscess or multiple abscess and metastatic abscesses. In patients with ventricular septal defects, the presence of relevant long-lasting pulmonary hypertension could eventually lead to cardiac dysfunction (right ventricular hypertrophy and dilation). These features will dominate when patients enter the terminal stages of severe Eisenmenger’s syndrome, which is characterized typically by pending or actual right heart failure [6]. In this patient, electrocardiogram showed severe right axis deviation and right ventricular hypertrophy, which is compensatory changes in response to long-lasting pulmonary hypertension and explains the bidirectional shunt.

In this patient population was high risk for developing perioperative complications due to the process of persistent infections. Therefore, strengthen the surgical management on perioperative was advocated to minimize perioperative complications. The patient sports activity with mild limitation. Although laboratory findings and physical examination demonstrated chronic hypoxemia, such as mean corpuscular hemoglobin increased, clubbing and cyanosis. Other clinical symptoms associated with increased intracranial pressure caused by brain abscesses prompted further examination. Subsequently, the diagnosis of VSD and secondary pulmonary hypertension were obtained.

According to the previous research, the incidence of brain abscesses in patients with congenital heart disease was 18% [7]. Although adult patients with congenital heart disease can also develop brain abscesses, but a previous study observed that the peak age of onset is between 4 and 7 years old [8]. A retrospective study described 142 cases of brain abscess, of which 122 (85.9%) patients received surgical treatment and all of patients were treated with parenteral antibiotics for at least 4 weeks, the mortality rate was 26.1%. And no difference in the outcome is found among various treatment strategies and choices of surgical procedures [9]. Similarly, a study was retrospective analysis of 26 children who were diagnosed with congenital cyanotic heart disease and brain abscess, reported 70% persistent bacteremia 38% abscess recurrence [10].

Stereotactic aspiration is the preferred surgical treatment for brain abscess, especially for small, deep-seated lesions, some studies have found that aspiration stereotactic drainage of brain abscess may carries a lower overall mortality rate compared with excision [11]. Also, the introduction of CT scanning and other imaging techniques have leaded to a significant reduction in mortality rates associated with surgical aspiration of abscess. Correspondingly, some study suggested that the preferred surgical treatment modality for brain abscess should vary from person to person. Careful observation through CT or MR imaging should be important to the patient. If the abscess fails to resolve or enlarges after a course of 2–4 weeks antibiotic use, further surgical removal or aspiration should be performed [12]. However, surgical excision is also recommended for multiple abscessed and larger lesions, especially when there is evidence that the intracranial pressure is increased due to severe perilesional edema severe perilesional edema or significantly mass effect of the brain abscess, such as the present case [13].

And other studied recommend excision as the best treatment of choice because it is usually accompanied by a lower incidence of post-operative epilepsy and recurrence [14]. Eisenmenger’s syndrome describes pulmonary vascular disease and cyanosis resulting from increased pulmonary vascular resistance with complete shunt reversal or bidirectional shunting through a large intracardiac (such as atrial septal defect or ventricular septal defect) or extracardiac congenital heart defect (such as ductus arterious or aortopulmonary window) [15,16]. Perioperative cardiac morbidity in the perioperative period is one of the major causes of perioperative death in cardiac patients who were undergoing noncardiac surgery, with mortality rate reaching 30% [17]. The perioperative risk may be related to the severity of the patient's cyanosis, tricuspid regurgitation and right ventricular dysfunction. Other surgery related risk factors also affects the perioperative risk, such as duration of operation, anesthesia used and hemodynamic variables [18]. We should maintain both cardic output and systemic vascular resistance when we use anesthetics, because Eisenmenger’s syndrome patients have lost the ability to response to sudden changes in hemodynamics because of fixed pulmonary vascular disease. Therefore, a minor decreases in systemic blood pressure and vascular resistance can increase the magnitude of right to left shunting and worsening hypoxia [19]. Surgical blood loss and general anesthesia are independent causes of intraoperative hypotension. The intraoperative blood loss should be minimized and blood products should be used to treat excessive bleeding in time. If the patient is hypovolemic, α-adrenergic agonists should be used to actively treat systemic arterial hypotension. In addition to selecting the appropriate anesthesia technique, measures to prevent systemic thromboembolic need to be taken. All intravenous lines should be equipped with a device to filter air bubbles to prevent air embolism. Furthermore, periodic arterial blood gas and plus oximetry allows monitoring the oxygen saturation, which may increase the likelihood of early detection of acidosis, hypercarbia and hypoxia. Irrespective of the selected intraoperative monitoring, sudden changes in hemodynamics should be detected early in the course of operative in order to begin the initiate appropriate treatment and to prevent further complications that could become fatal [20]. The preoperative evaluation, intraoperative management and postoperative care are important steps in the treatment of cardiac patients undergoing noncardiac surgery, and essential for patient’s safe and fast recovery. Eisenmenger patients shifted to the ICU for further treatment and observation are recommended. Measures must be taken to prevent venous thrombosis, such as get out of bed early or regular pneumatic compression. In addition, particular attention should be paid to fluid balance to prevent hypovolemia. Furthermore, adequate pain management paly an essential role in prevent postoperative adverse hemodynamics and possibly hypercoagulable state [21,22]. When noncardiac surgery is necessary in patients with the Eisenmenger syndrome, the surgery procedures should be performed at centers with expertise in the management of the syndrome and with cardiac-specialized anesthesiologists, and the patient should be observed and management closely and carefully during perioperative.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we reported a rare clinical case report of brain abscess combined with Eisenmenger syndrome, which has been successfully treated with intravenous antibiotics and timely surgical intervention. In order to better understand and ultimately prevent occurrence of this potentially fatal syndrome. The preoperative evaluation, intraoperative management and postoperative care are important steps in the treatment of cardiac patients undergoing noncardiac surgery, and essential for patient’s safe surgery and fast recovery. The risk of failure of empirical initial antibiotic therapy and associated death is high, especially for negative pus cultures. Solving hypoxemia and hypercogulable state of blood are important to reduce the risk of thrombosis are valuable interventions. During surgery, we recommend ensuring that intraoperative blood loss is minimized, and postoperative care should be long-term targeted subsequent antibiotic therapy to minimize the risk of abscess recurrence, especially in the initial examination of blood culture negative patients.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors claims no conflicts of interests.

Sources of funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Ethical approval

The study is exempted from ethical approval.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

The study was planned and designed by KC and PJ. KC and PJ participated in the diagnostics and treatment of the disease. Manuscript was prepared by KC and PJ. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Dr. Pucha Jiang.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Contributor Information

Keyu Chen, Email: chenkeyuwh@163.com.

Pucha Jiang, Email: 1042589714@qq.com.

References

- 1.Moorthy R.K., Rajshekhar V. Management of brain abscess: an overview. Neurosurg. Focus. 2008;24(6):E3. doi: 10.3171/FOC/2008/24/6/E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brouwer M.C. Brain abscess. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371(5):447–456. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1301635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodilsen J. Risk factors for brain abscess: a nationwide, population-based, nested case-control study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71(4):1040–1046. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agha R.A. The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeshita M. Current treatment of brain abscess in patients with congenital cyanotic heart disease. Neurosurgery. 1997;41(6):1270–1278. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199712000-00006. discussion 1278-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penny D.J., Vick G.W. Ventricular septal defect. Lancet. 2011;377(9771):1103–1112. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lumbiganon P., Chaikitpinyo A. Antibiotics for brain abscesses in people with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013;2013(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004469.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kagawa M. Brain abscess in congenital cyanotic heart disease. J. Neurosurg. 1983;58(6):913–917. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.58.6.0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tseng J.-H., Tseng M.-Y. Brain abscess in 142 patients: factors influencing outcome and mortality. Surg. Neurol. 2006;65(6):557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Udayakumaran S., Onyia C.U., Kumar R.K. Forgotten? Not yet. Cardiogenic brain abscess in children: a case series-based review. World Neurosurg. 2017;107:124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.07.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ratnaike T.E. A review of brain abscess surgical treatment--78 years: aspiration versus excision. World Neurosurg. 2011;76(5):431–436. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavusoglu H. Brain abscess: analysis of results in a series of 51 patients with a combined surgical and medical approach during an 11-year period. Neurosurg. Focus. 2008;24(6):E9. doi: 10.3171/FOC/2008/24/6/E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muzumdar D., Jhawar S., Goel A. Brain abscess: an overview. Int. J. Surg. 2011;9(2):136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Auvichayapat N., Auvichayapat P., Aungwarawong S. Brain abscess in infants and children: a retrospective study of 107 patients in northeast Thailand. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2007;90(8):1601–1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vongpatanasin W. The Eisenmenger syndrome in adults. Ann. Intern. Med. 1998;128(9):745–755. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-9-199805010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berman E.B., Barst R.J. Eisenmenger’s syndrome: current management. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2002;45(2):129–138. doi: 10.1053/pcad.2002.127492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ammash N.M. Noncardiac surgery in Eisenmenger syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1999;33(1):222–227. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00554-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daliento L. Eisenmenger syndrome. Factors relating to deterioration and death. Eur. Heart J. 1998;19(12):1845–1855. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerardin J.F., Earing M.G. Preoperative evaluation of adult congenital heart disease patients for non-cardiac surgery. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2018;20(9):76. doi: 10.1007/s11886-018-1016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaix M.A. Eisenmenger syndrome: a multisystem disorder-do not destabilize the balanced but fragile physiology. Can. J. Cardiol. 2019;35(12):1664–1674. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2019.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett J.M. Anesthetic management and outcomes for patients with pulmonary hypertension and intracardiac shunts and Eisenmenger syndrome: a review of institutional experience. J. Clin. Anesth. 2014;26(4):286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2013.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Alto M., Diller G.P. Pulmonary hypertension in adults with congenital heart disease and Eisenmenger syndrome: current advanced management strategies. Heart. 2014;100(17):1322–1328. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]