Abstract

In the United States, despite significant investment and the efforts of multiple maternal health stakeholders, maternal mortality (MM) has reemerged since 1987 and MM disparity has persisted since 1935. This article provides a review of the U.S. MM trajectory throughout its history up to its current state. From this longitudinal perspective, MM trends and themes are evaluated within a global context in an effort to understand the problems and contributing factors. This article describes domestic and worldwide strategies recommended by maternal health stakeholders to reduce MM.

Keywords: maternal mortality, United States, global context, disparity, strategies

Introduction

“Maternal mortality (MM) is widely acknowledged as a general indicator of the overall health of a population, of the status of women in society, and of the functioning of the health system.”1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) use different terms and measures to characterize MM (Box 1),2–6 but the maternal mortality ratio (MMR), calculated as the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, is a widely utilized measure worldwide.2 Henceforth in this article, MMR will be displayed by its numerator only. Although the estimated global MMR has declined by 45%, decreasing from 385 in 1990 to 211 in 2017, the estimated MMR in the United States has increased by 58%, from 12 in 1990 to 19 in 2017 (Table 1).2,7 This article analyzes worldwide practices, data, and literature to establish future objectives to reduce MM in the United States.

Box 1.

Terms and Definitions

| World Health Organization |

| Maternal death: the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from unintentional or incidental causes. |

| Late maternal death: the death of a woman from direct or indirect obstetric causes, more than 42 days but <1 year after termination of pregnancy. |

| Pregnancy-related death: the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the cause of death (obstetric and nonobstetric) and includes unintentional/accidental and incidental causes. |

| Direct obstetric death: the death of a woman resulting from obstetric complications of the pregnant state (pregnancy, labor, and puerperium) from interventions, omissions, incorrect treatment, or from a chain of events resulting from any of the above. |

| Indirect obstetric death: the death of a woman resulting from previous existing disease or disease that developed during pregnancy and that was not due to direct obstetric causes, but that was aggravated by physiologic effects of pregnancy. |

| Maternal mortality ratio: the number of maternal deaths during a given time period per 100,000 live births during the same time period. |

| MMRate: the number of maternal deaths during a given time period divided by person-years lived by women of reproductive age (age 15–49 years) in a population during the same time period. |

| Adult lifetime risk of maternal death: the probability that a 15-year-old girl will eventually die from a maternal cause. |

| Proportion maternal: the proportion of deaths among women of reproductive age (age 15–49 years) that are due to maternal causes. |

| Live birth: the complete expulsion or extraction from its mother of a product of conception, irrespective of the duration of the pregnancy, which, after such separation, breathes or shows any other evidence of life (e.g., beating of the heart, pulsation of the umbilical cord, or definite movement of voluntary muscles) whether or not the umbilical cord has been cut or the placenta is attached. Each product of such a birth is considered live born. |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (DRH and DVS). DRS and DVS are part of CDC. The way it is written it seems to be 3 separate entities CDC, DRH and DVS. |

| Pregnancy-associated death: the death of a woman during pregnancy or within 1 year of the end of pregnancy from a cause that is not related to pregnancy. All deaths that have a temporal relationship to pregnancy are included. |

| Pregnancy-related death: the death of a woman during pregnancy or within 1 year of the end of pregnancy from a pregnancy complication, a chain of events initiated by pregnancy, or the aggravation of an unrelated condition by the physiological effects of pregnancy. In addition to having a temporal relationship to pregnancy, these deaths are causally related to pregnancy or its management. |

| PRMR: pregnancy-related deaths per 100,000 live births. |

| Preventability: a death is considered preventable if the committee determines that there was at least some chance of the death being averted by one or more reasonable changes to patient, community, provider, facility, and/or system factors. |

| MMRate: maternal deaths as defined by the World Health Organization per 100,000 live births. |

| Late MMRate: late maternal deaths as defined by World Health Organization per 100,000 live births. |

DRH, Division of Reproductive Health; DVS, Division of Vital Statistics; MMRate, maternal mortality rate; PRMR, Pregnancy-Related Mortality Ratio.

DVS uses the term MMRate (equivalent measure of WHO's maternal mortality ratio), and DRH uses the term PRMR. DVS's MMRate term is referred as MMR in the text.

Table 1.

Trends in Estimates of Maternal Mortality Ratio, Lifetime Risk, by Selected Countries, World Health Organization Region, and World Bank Income Group, 1990–2017

| Year | Maternal mortality ratio |

Lifetime risk of maternal death 1 in …2017 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2017 | ||

| World | 385 | 369 | 342 | 296 | 248 | 219 | 211 | 190 |

| Australia | 8 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 8200 |

| Canada | 7 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 6100 |

| Netherlands | 12 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 11,900 |

| United Kingdom | 10 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 8400 |

| United States | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 15 | 18 | 19 | 3000 |

| WHO Region | ||||||||

| Africa | 965 | 914 | 857 | 735 | 615 | 548 | 525 | 39 |

| America | 102 | 89 | 73 | 68 | 64 | 60 | 59 | 850 |

| South East Asia | 525 | 438 | 355 | 280 | 214 | 165 | 152 | 280 |

| Europe | 44 | 42 | 27 | 22 | 17 | 14 | 13 | 4300 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 362 | 340 | 330 | 275 | 220 | 175 | 164 | 170 |

| Western Pacific | 114 | 89 | 75 | 61 | 51 | 43 | 41 | 1400 |

| World Bank Income Group | ||||||||

| Low income | 1020 | 944 | 833 | 696 | 573 | 491 | 462 | 45 |

| Lower middle income | 532 | 470 | 428 | 363 | 302 | 265 | 254 | 140 |

| Upper middle income | 117 | 101 | 69 | 61 | 51 | 44 | 43 | 1200 |

| High income | 27 | 26 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 5400 |

Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom were selected because these countries were comparable to the United States as high-income countries with relatively robust data on birth settings and outcomes from their vital statistics systems.13

WHO, World Health Organization.

Source: years 1990 and 19957; years 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2017.2

Global Context

In 2000, the United Nations formed a global partnership to reduce world poverty and set eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), including a goal to improve maternal health (target: reduce MMR by three quarters between 1990 and 2015).8 Building on the momentum of these MDGs, the United Nations established 17 Sustainable Development Goals, including a goal to ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all, with a target of reducing the global MMR to <70 by 2030.9

Despite the decline of the estimated global MMR, disparity among countries is high, with 99% of preventable MM occurring in low- and middle-income countries. MM disparity is also high within countries, with a higher risk of MM among the most vulnerable segments of society (Table 1).10 In the United Kingdom, where overall MMR has been steadily low, MM disparity occurs along racial and ethnic lines. Compared with White women, Black women, women of mixed ethnicity, and Asian women have a higher risk of dying during pregnancy or up to 6 weeks post partum.11

Several reports have described the international efforts addressing MM. In 2015, WHO established a strategic framework toward Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality using guiding principles, crosscutting actions, and strategic objectives (Box 2).10 In 2018, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) held the HRSA Maternal Mortality Summit. At this international summit, a group of subject-matter experts from Brazil, Canada, Finland, India, Rwanda, the United Kingdom, and the United States discussed promising global practices and identified areas, where actions could decrease MM (Box 2).12 A 2020 report examining U.S. birth settings, a crucial component of maternity care, described important common practices in Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. These countries were all committed to integrating care across birth providers, ranging from well-trained midwives attending uncomplicated deliveries to highly specialized obstetricians. They also supported seamless transfer across, out of, and into hospital maternity care systems; universal access to primary and maternity care before, during, and after pregnancy; and adoption of respectful care and respect for maternal autonomy.13 It is important to note that the MMR in these other high-income countries is significantly lower than in the United States (Table 1).2 Thus, the United States has an opportunity to adapt to its context those strategies that have proven successful in improving MM in other countries.

Box 2.

Global and Domestic Strategies to Reduce Maternal Mortality in the United States

| World Health Organization: Strategic Framework Toward EPMM | ||

| Guiding principles for EPMM | ||

| Empower women, girls, and communities. | ||

| Protect and support the mother–baby dyad. | ||

| Ensure country ownership; leadership; and supportive legal, technical, and financial frameworks. | ||

| Apply a human rights framework to ensure that high-quality reproductive, maternal, and newborn health care is available, accessible, and acceptable to all who need it. | ||

| Crosscutting actions for EPMM | ||

| Improve metrics, measurement systems, and data quality to ensure that all maternal and newborn deaths are counted. | ||

| Allocate adequate resources and effective health care financing. | ||

| Five strategic objectives for EPMM | ||

| Address inequities in access to and quality of sexual, reproductive, maternal, and newborn health care. | ||

| Ensure universal health coverage for comprehensive sexual, reproductive, maternal, and newborn health care. | ||

| Address all causes of maternal mortality, reproductive and maternal morbidities, and related disabilities. | ||

| Strengthen health systems to respond to the needs and priorities of women and girls. | ||

| Ensure accountability to improve quality of care and equity. | ||

| Health Resources and Services Administration International Summit: Key Findings in Areas Where Action Could Contribute to Decreased Maternal Mortality | ||

| Access: Improve access to patient-centered, comprehensive care for women before, during, and after pregnancy, especially in rural and underserved areas. | ||

| Safety: Improve quality of maternity services through efforts, such as the utilization of safety protocols in all birthing facilities. | ||

| Workforce: Provide continuity of care before, during, and after pregnancies by increasing the types and distribution of health care providers. | ||

| Life Course Model: Provide continuous team-based support and use a life course model of care for women before, during, and after pregnancies. | ||

| Data: Improve the quality and availability of national surveillance and survey data, research, and common terminology and definitions. | ||

| Review Committees: Improve quality and consistency of Maternal Mortality Review Committees through collaborations and technical assistance with U.S. states. | ||

| Partnerships: Engage in opportunities for productive collaborations with multiple summit participants. | ||

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Prevention Measures to Reduce Maternal and Infant Mortalitya | ||

| Before conception | ||

| Screen women for health risks and pre-existing chronic conditions, such as diabetes and hypertension. | ||

| Advise women to avoid alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs. | ||

| During pregnancy | ||

| Provide women with early access to high-quality care throughout pregnancy, labor, and delivery. | ||

| Educate women about the early signs of pregnancy-related problems. | ||

| During postpartum period | ||

| Provide information about well-baby care and benefits of breastfeeding. | ||

| Educate parents about how to protect their infants from exposure to infectious diseases and harmful substances. | ||

| Maternal Mortality Review Committee: Identified Contributing Factors and Strategies to Prevent Future Pregnancy-Related Deatha | ||

| Level | Contributing factor | Strategies to address contributing factor |

| Community | Unstable housing | Prioritize pregnant and postpartum women for temporary housing programs |

| Health facility | Limited experience with obstetric emergencies | Implement obstetric emergency simulation training for emergency department and obstetric staff members |

| Patient/family | Nonadherence to medical regimens or advice | Strengthen and expand access to patient navigators, case managers, and peer support |

| Provider | Missed or delayed diagnosis | Offer provider education on cardiac conditions in pregnant and postpartum women |

| System | Case coordination or management | Implement a postpartum care transition bundle for better integration of services for women at high risk |

Some examples of prevention measures and contributing factors and strategies are provided, but these do not represent the complete list.

EPMM, Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality.

Historical Trends

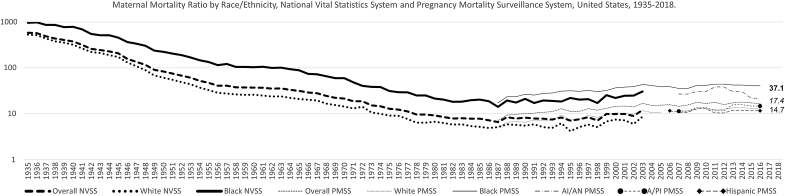

In 1990, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) developed a national agenda for a healthier nation. Reducing the nation's MMR was a key maternal, infant, and child health indicator in the Healthy People 2000 objectives (target: 3.3; baseline 1987: 6.6) and Healthy People 2010 (target: 4.3; baseline 1999: 9.9). This objective has been updated in Healthy People 2020 (target 11.4; baseline 2007: 12.7).14–16 The CDC monitors MM through the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) administered by the Division of Vital Statistics (DVS) and Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System (PMSS), managed by the Division of Reproductive Health (DRH) (Fig. 1).3–5,17–25 DVS uses the term MMR, whereas DRH uses the term Pregnancy-Related Mortality Ratio (PRMR).3,4,6 In addition to DVS and DRH, state and local Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs), composed of multidisciplinary members, play a pivotal role in providing systematic review and determining the risk factors, causes, and preventable drivers of maternal deaths.5,6,24 Two MMRCs were formed in the early 1930s; by 2018 that number had increased to include MMRCs in 45 states and the District of Columbia.26

FIG. 1.

MMR and PRMR by Race and Ethnicity, NVSS, and PMSS, United States, 1935–20183–5,17–25 NVSS 2018 Black = 37.1, overall = 17.4, White = 14.7. NVSS is administered by the DVS at the National Center for Health Statistics, and PMSS is managed by the DRH at the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. NVSS is the official source for mortality statistics in the United States, and DVS has been reporting MM since 1900. In 2007, however, reporting was interrupted with 2003 data due to implementation by the states of the Pregnancy Checkbox added in the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death in 2003. In 1986, recognizing the gaps in collecting more comprehensive MM data, DRH, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists established PMSS to collect additional clinical information for pregnancy-related deaths and has reported PRMR since 1987. In 2020, DVS resumes reporting of MM with 2018 data. A/PI, Asian/Pacific Islander; AI/AN, American Indian/Alaska Native; Black, non-Hispanic Black; DRH, Division of Reproductive Health; DVS, Division of Vital Statistics; MM, maternal mortality; MMR, maternal mortality ratio; NVSS, National Vital Statistics System; PMSS, Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System; PRMR, Pregnancy-Related Mortality Ratio; White, non-Hispanic White. Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NVSS 1935–2003, 2018; PMSS 1987–2016.

One of the greatest public health achievements of the 20th century in the United States was the decline of MMR from >800 in 1900 to its lowest point of 6.6 in 1987 (Fig. 1).17 The steady decline of MMR over these 8.5 decades might be attributed to several factors: environmental interventions; improvements in nutrition, surveillance and monitoring of diseases, access to health care, and standard of living; advances in clinical medicine; increases in education; and technical and political changes implemented over time (e.g., MM reviews in the 1930s, shift from home to hospital births in the1940s, use of antibiotics and transfusions in the 1950s, and implementation of Medicaid in the 1960s).13,27,28 However, MMR gradually reversed course and doubled from 6.6 in 1987 to 12.1 in 2003.17 Similarly, an ascending trend for PRMR from 7.2 in 1987 to 16.9 in 2016 was observed (Fig. 1).25 Contributing factors to the increasing trend of U.S. MMR may include poor data quality due to the lack of interoperability of MM measures and harmonization of reporting artifacts over time (e.g., the evolution of cause-of-death codes for maternal death from ICD-1 to ICD-10 and use of the pregnancy checkbox on the death certificate); disparities in health care access and quality; increasing maternal age, coupled with high prevalence of comorbid conditions surrounding pregnancies and pregnancy-associated conditions (e.g., gestational diabetes, preeclampsia); and other social determinants of health (SDOH).3,29–34

Several analyses of national, state, and local data demonstrate disparities in MM by sociodemographic factors (e.g., race, ethnicity, age, education level, marital status, health insurance), geographic areas (e.g., rural vs. urban), and states.4,23,32,34–40 Regardless of the direction of the overall U.S. MMR trajectory over time, however, racial disparities in MM have persisted for more than 80 years (Fig. 1). Analyses of PMSS data from 2007 to 2016 showed that non-Hispanic Black (Black) women 40 years and older and American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) women 35–39 years of age had the highest PRMR at 189.7 and 104.2, respectively. Conversely, Hispanic women and Asian and Pacific Islander women age 20–24 had the lowest PRMRs at 7.0 and 7.2, respectively. Notably, the PRMR for Black women increased, and the Black-to-White Disparity Ratio (B:WDR) widened with increasing age, but PRMR did not decrease with higher education levels.23 Black women at all levels of income and education have a higher maternal death risk than non-Hispanic White (White) women. These disparities may be related to the “weathering” hypothesis, which proposes that Black women experience earlier deterioration of health because of the cumulative impact of exposure to the racial construct's psychosocial, economic, and environmental stressors.35 Additionally, PMSS data from 1998 to 2005 indicate that MMR for unmarried women was 1.7 times that of married women, and MMR for women with no prenatal care was 5 times that of women with any prenatal care.21 Studies have inversely associated increasing MM with family planning.32

Closure of gynecological and obstetrical care services and shortage of obstetricians and gynecologists in rural and underserved communities have become more acute lately.13,41,42 Women living in rural areas and low-income women continue to be at increased risk for pregnancy-related deaths.42 In 2015, an analysis of national data found that the MMR in rural areas was 29.4, 1.6 times higher than the MMR of 18.2 in large, central metropolitan areas.38 From 2014 to 2016, Washington state data showed that the MMR for rural residents was 1.5 times that of urban residents, and MMRs for women for whom no health insurance records could be located and women with Medicaid were, respectively, 12 and 3.5 times higher than those of women with private insurance.43 Analyses of NVSS and PMSS data have revealed both a wide range of MMRs among states and the District of Columbia and a consistently high B:WDR in every state and the district during 1987–2016, indicating that racial disparity remained a public health issue even in states with lower MMR.23,32,39 The differences in state MMRs involved many factors, including the structure and funding of maternal health services in each state and the composition of populations at high risk for MM.31

Current State

In 2020, DVS reported that 2018 data showed a total of 658 maternal deaths, MMR of 17.4, 277 late maternal deaths, and late MMR of 7.3. Nationwide MM disparities continued across subpopulations, states, and geographic areas. The MMR for Black women (37.1) was 2.5 times that of White women (14.7) and 3.1 times that of Hispanic women (11.8). The MMR for women age 40 and older (81.9) was 7.7 times that of women age 25 and younger (10.6).3 The District of Columbia and states with 10 or more reported maternal deaths had state-specific MMRs ranging from 9.7 to 45.9.40 Based on analyses of recent PMSS data, maternal deaths occurred during pregnancy (31%), at delivery (17%), 1–42 days postpartum (40%), and 43–365 days postpartum (12%). About 60% of the maternal deaths were deemed preventable. The most common causes of maternal death included cardiovascular conditions (e.g., cardiomyopathy, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, cerebrovascular accidents), infection, and hemorrhage. However, the cause-of-death proportions varied by timing of death and race/ethnicity of the women.4 Cardiomyopathy, thrombotic pulmonary embolism, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy contributed more to pregnancy-related deaths among Black women than among White women. Hemorrhage and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy contributed more to pregnancy-related deaths among AI/AN women than among White women.23

Recently, stories about deaths of mothers and the dilemma the United States is facing with the steady rise and disparity of MM have gained attention in the news media. Many sectors—including the public; lawmakers and policymakers; federal, state, and local governments; academia; professional and women's health advocacy groups; and private and nonprofit entities—have undertaken new initiatives or enhanced ongoing efforts to reduce MM through collaboration and partnership (Table 2).24,25,44–57 Legislators in both the U.S. Senate and U.S. House of Representatives have introduced bills that focus on issues ranging from expanding awareness of MM disparity to extending current Medicaid coverage from 60 days to 1 year postpartum.44 The HHS Office on Women's Health is leading a trans-HHS workgroup to develop an action plan to improve health outcomes for America's mothers and babies and coordinate activities supported by the federal government.

Table 2.

Examples of Maternal Health Stakeholder Efforts to Reduce Maternal Mortality

| Stakeholders24,25,44–57 | Description |

|---|---|

| Legislators | |

| The Preventing Maternal Deaths Acta | Reauthorizes through FY2023 for CDC to provide support to tribal, state, and local MMRCs. |

| The Improving Access to Maternity Care Acta | Requires HRSA to identify maternity care health professional target areas. |

| The Affordable Care Act | Provides support for the HRSA's Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Visitation Program. |

| The 21st Century Cures Act | Establishes Task Force on Research Specific to PRGLAC on safe and effective therapies. |

| The Senate Finance Committee Leaders | Call to submit data and findings on factors contributing to poor maternal health outcomes in the United States. |

| Public and private entities | |

| CDC, CDC Foundation, AMCHP | Building U.S. capacity to review and prevent MM to remove barriers to fully functional MMRCs. |

| Merck for Mothers and Community Organizations | Safer Childbirth Cities Initiative to foster solutions led by local communities in helping cities to become safer and more equitable places to give birth. |

| Merck for Mothers and ACOG | Safe Motherhood Initiative to decrease MM by engaging health care providers and birthing facilities to develop and implement standard approaches for handling obstetric emergencies. |

| SMFM and ACOG | Joint consensus document that introduced a classification system for levels of maternal care. |

| IHS, ACOG, and AAP | Program to conduct-site visits and improve rural obstetrics care in the Indian health system. |

| CDC | |

| ERASE MM | Supports agencies and organizations that coordinate and manage MMRCs. |

| Perinatal Quality Collaboratives | State or multistate networks of teams working to improve the quality of care for mothers and babies. |

| LOCATe | Helps states/jurisdictions create standardized assessments of levels of maternal and neonatal care. |

| HRSA SPRANS Program | |

| AIM | Promotes the adoption and implementation of hospital-focused maternal safety bundles (evidence-based practices) for health care providers in birthing facilities and hospitals. |

| AIM–Community Care Initiative | Supports the development, adoption, and implementation of nonhospital maternal safety bundles for health care providers in community-based organizations and outpatient settings. |

| RMOMS | Develops, tests, and implements service models, with the goal of improving access to, and continuity of, maternal and obstetrics care in rural communities. |

| State MHI | Funds state-focused demonstration projects with three core functions: (1) establishing a state-focused Maternal Health Task Force, (2) improving state-level maternal health data and surveillance, and (3) promoting and implementing innovations in the health care delivery of maternal health care services. |

| Supporting MHI | Supports states, key stakeholders, and recipients of HRSA-administered awards. |

| NIH | |

| Trans-NIH funding FY2018 ($302.6 million dollars)/FY2017 ($250 million dollars) | Funded maternal health projects addressing scientific gaps such as risk prediction, severe morbidity, optimal timing for delivery, maternal long-term outcomes, and data collection. |

| CCRWH | Provides valuable guidance, collaboration, and support to ORWH program goals. |

| ORWH/NICHD | Launched MMM web portal and MMM booklet; sponsored MMM workshops and meetings. |

| CMS | |

| Rethinking Rural Health Initiative | Rural Health Strategy to have new health policies and initiatives positively impact rural communities. |

| Medicaid and CHIP | Scorecard to evaluate state progress on maternal health outcomes. |

| FDA | |

| OMPT, CDER, and CBER | Issued Postapproval Pregnancy Safety Studies Guidance for Industry in 2019. |

| Office of Women's Health | Provides resources for consumers about food safety and medication use during pregnancy. |

| State/city | |

| CMQCC (State of California and Stanford University School of Medicine) | Expanded Maternal Quality Improvement Toolkits in areas of substance exposure, sepsis, venous thromboembolism, and cardiovascular disease. |

| NYCDHMH | Five-year plan to improve MM disparity through city-wide hospital quality improvement network, comprehensive maternity care in NYC health system, enhancement of data quality, and timeliness and public awareness campaign. |

AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; ACOG, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; AIM, Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health; AMCHP, Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs; CBER, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research; CCRWH, Coordinating Committee on Research on Women's Health; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CDER, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; CHIP, Children's Health Insurance Program; CMQCC, California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative; CMS, Centers for Medicaid and Medicare; ERASE MM, Enhancing Reviews and Surveillance to Eliminate Maternal Mortality; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; FY, fiscal year; HRSA, Health Resources and Services Administration; IHS, Indian Health Service; LOCATe, Levels of Care Assessment Tool; MHI, Maternal Health Innovation; MM, maternal mortality; MMM, Maternal Morbidity and Mortality; MMRCs, Maternal Mortality Review Committees; NICHD, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; NIH, National Institutes of Health; NYCDHMH, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; OMPT, Office of Medical Products and Tobacco; ORWH, Office of Research on Women's Health; PRGLAC, Research Specific to Pregnant Women and Lactating Women; RMOMS, Rural Maternity and Obstetrics Management Strategies; SMFM, Society for Maternal/Fetal Medicine; SPRANS, Special Projects for Regional and National Significance.

Amended the Public Health Service Act.

The availability of services and type of health insurance a woman has, greatly influence her choice of health care provider.13 Medicaid is the nation's largest payor of perinatal care and is especially important in rural and underserved communities. Nevertheless, Medicaid provides coverage only up to 60 days postpartum.53 In 2018, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued an Opinion endorsed by other maternal health care professional organizations to reinforce the importance of the “fourth trimester” and propose a new paradigm for postpartum care.58 One study showed that Medicaid expansion up to 1 year postpartum has been associated with 1.6 fewer maternal deaths per 100,000 women than states that did not expand Medicaid.59 In addition to expanding health care coverage for community-based maternity care by all payors, improving the quality of available health care is crucial for the reduction of MM.13 Several states and institutions have implemented both the State Perinatal Quality Collaboratives program and the HRSA-funded Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM) program in their health care systems.50,60,61 The California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative, a public–private partnership, has implemented maternal quality improvement programs with a focus on hemorrhage and preeclampsia that have reduced the state MMR, but not the B:WDR, from 2006 to 2016.36 Another system-based improvement in maternal safety that has been adopted by one-third of states is the incorporation of levels of maternal care criteria in the state perinatal guideline. This approach provided an effective strategy by specifying required resources and capabilities within an integrated system of risk-appropriate care in a region.62

Future Directions

The following recommendations to reduce MM are based on trends and common themes identified through the review and assessment of the historical data and current literature.

Establish a national taskforce on maternal morbidity and mortality

Drivers of the upward trend of MM and its continuing disparities in the United States are not well understood and have challenged maternal health stakeholders. Although ongoing efforts to reduce MM led by public and private sectors are targeting multiple contributing factors, it is crucial that the United States establish a national task force on maternal morbidity and mortality to better coordinate and integrate the limited human and capital resources under a national call-to-action plan. This task force can set short-, medium-, and long-term goals using the strategies and innovative solutions that have proven effective in the United States and worldwide.4,10,12,27,35,60,63,64

Minimize health disparities through innovations and cultural competency

In communities of color, discriminatory policies and practices that affect the quality of their health care and standard of living should be examined and modified by designing appropriate and culturally tailored action plans to eliminate or minimize the influence of racism on such service systems as education, health care, housing, labor, and other SDOH.35 Innovative strategies that effectively reduce disparities in MM are needed. For example, the reduction of hypertensive disorder, a major cause of MM among minority women, can be accomplished by adapting novel, culturally tailored, and evidence-based approaches. In one instance, a clinical trial effectively lowered high blood pressure among Black men who were patrons of barbershops. Barbers, trained as health educators, screened and referred patrons with uncontrolled hypertension to medical professionals, including pharmacists trained in the management of hypertension.65

Disparity in accessing maternal health care in underserved communities can be alleviated by expanding the capacity of telehealth technologies and their utilization across the country. The Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) project has used telehealth technology to successfully expand specialized treatment to communities with shortages of specialty care through best practices protocols and primary care physician and specialist team efforts.66 This model can be adapted to enable maternal health providers in rural and underserved communities to provide obstetric specialty care to women at high risk of MM. Engaging communities in prevention efforts and supporting community-based programs that build social support and resiliency would likely improve patient–provider interaction, health communication, and health outcomes.35,67

Invest in a diverse maternal health workforce

To address the growing shortage of obstetricians and gynecologists in the United States, investments are needed to expand the maternity care workforce pipeline, including nurse midwives, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, family physicians, doulas, and community health workers.13 Doing so may increase the diversity, distribution, and size of maternal care in the United States. Although midwives constitute an important, safe, and cost-effective segment of maternity care, especially in rural areas, barriers to the practice of midwifery exist across the country. It is important to address the wide variation in regulation, certification, and licensing of maternity care professionals across the United States. In addition to clinicians, increasing the number of community health workers, public health practitioners, and researchers in the maternal morbidity and mortality arena is essential for the expansion of functional MMRC, community-based maternity care, and execution of the national research agenda.24,51,64

Expand health care coverage using a life course model

It is essential that Medicaid coverage be extended up to 1 year postpartum nationwide; this has been advocated by professional organizations.58 Pregnant women living in high-income countries with universal insurance coverage are not deprived of health care before, during, or after pregnancy. This access to universal coverage contributes to the low MMR observed in these countries.13

Improve health care quality through respectful maternal and child care

Because the majority of maternal deaths occur during pregnancy and at delivery—when most women have health care coverage—it is critical to improve the quality of health care by empowering women and communities and applying a human rights framework to protect and support mothers and babies.10 Health care systems can implement standardized protocols to address obstetric emergencies and quality improvement initiatives, such as provider education to reduce missed or delayed diagnoses and a maternal early warning system.68 Another approach is to engage nonphysician clinicians for continuity and coordination of care. Patient navigation and other health system–barrier interventions have worked well to dismantle obstacles to health care access and utilization.69–71 As part of maternal and infant care integration, the AIM program has developed sets of standardized, bundled guidance supported by perinatal quality collaboratives, which are state-based initiatives that aim to improve the quality of care for mothers and infants.72 These quality care initiatives can be enhanced to address all causes of MM.

Integrate health service, biomedical, behavioral, and social sciences research

Research is pivotal in advancing the understanding of the complex public health issues contributing to MM, and continued research is needed to address scientific gaps and identify effective and innovative evidence-based solutions.51,64 A coordinated research agenda can be developed by a multidisciplinary team of experts from public, private, community, and advocacy organizations using a common research platform. More research is needed to elucidate biological disease processes; identify social and behavioral influences; design clinical interventions; and generate innovative solutions to address demographic and socioeconomic risk factors, racial and ethnic disparities, and other health system factors that increase maternal morbidity and mortality. Specific and innovative health services research applying rigorous data science will be key to making empirically grounded advances in maternal health outcomes in the United States. “Big Data” analytics that encourage interoperability and harmonization of women's health and maternal morbidity and mortality metrics, without disenfranchising minority and underserved populations, will be key to advancing our understanding of the issues contributing to the larger problem of MM.

Conclusion

The disparities in MM continue to be a public health challenge, even in those U.S. states, where the overall MMR has been reduced. A national task force is needed to coordinate and integrate diverse efforts led by maternal health stakeholders to decrease health disparities and reduce the U.S. MMR to a level similar to those reported in other high-income countries.

Disclaimer

The findings and perspectives in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institutes of Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration, or the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). Reproductive health indicators: Guidelines for their generation, interpretation and analysis for global monitoring. Geneva: WHO Press, 2006:16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO). Trends in maternal mortality, 2000 to 2017: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva: WHO Press, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoyert DL, Miniño AM. Maternal mortality in the United States: Changes in coding, publication, and data release, 2018. National Vital Statistics Reports 2020;69. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2020 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, et al. . Vital signs: Pregnancy-related deaths, United States, 2011–2015, and strategies for prevention, 13 states, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:423–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. St. Pierre A, Zaharatos J, Goodman D, Callaghan WM. Challenges and opportunities in identifying, reviewing, and preventing maternal deaths. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:138–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davis NL, Smoots AN, Goodman DA. Pregnancy-related deaths: Data from 14 U.S. Maternal Mortality Review Committees, 2008–2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/erase-mm/MMR-Data-Brief_2019-h.pdf Accessed July6, 2020

- 7. World Health Organization (WHO). Trends in maternal mortality, 1990 to 2015: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva: WHO Press, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 8. United Nations. The millennium development goals report. New York, 2015. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/publications/mdg-report-2015.html Accessed July6, 2020

- 9. United Nations. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York, 2015. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication Accessed July6, 2020

- 10. World Health Organization. Strategies towards ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM). Geneva: WHO Press, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Knight M, Bunch K, Tuffnell D, et al. , eds. on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving lives, improving mothers' care: Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland confidential enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity, 2015–17. Oxford: University of Oxford, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). HRSA maternal mortality summit, June 19–21, 2018: Promising global practices to improve maternal health outcomes technical report. February 15, 2019. Available at: https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/maternal-mortality/Maternal-Mortality-Technical-Report.pdf Accessed July6, 2020

- 13. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Birth settings in America: Outcomes, quality, access, and choice. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2020 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Center for Health Statistics. Healthy People 2000 final review. Hyattsville, MD: Public Health Service, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Center for Health Statistics. Healthy People 2010 final review. Hyattsville, MD: Public Health Service, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Center for Health Statistics. Chapter 26 Maternal, Infant, and Child Health (MICH). In Healthy People 2020: Midcourse review. Hyattsville, MD: Public Health Service, 2017:1–37 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hoyert DL. Maternal mortality and related concepts. Vital Health Stat 2007;3:1–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chang J, Elam-Evans LD, Berg CJ, et al. . Pregnancy-related mortality surveillance—United States, 1991–1999. MMWR Surveill Summ 2003;52:1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berg CJ, Atrash HK, Koonin LM, Tucker M. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1987–1990. Obstet Gynecol 1996;88:161–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berg CJ, Chang J, Callaghan WM, Whitehead SJ. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1991–1997. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101:289–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Syverson C, Henderson Z. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1998 to 2005. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:1302–1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006–2010. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:5–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, et al. . Racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths, United States, 2007–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:762–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zaharatos J, St Pierre A, Cornell A, Pasalic E, Goodman D. Building U.S. capacity to review and prevent maternal deaths. J Womens Health 2018;27:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Maternal mortality. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm Accessed July6, 2020

- 26. Kozhimannil KB, Interrante JD, Corbett A, Heppner S, Burges J, Henning-Smith C. Rural focus and representation in state Maternal Mortality Review Committees: Review of policy and legislation. Womens Health Issues 2019;29:357–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthier mothers and babies. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1999;48:849–858 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Callaghan WM. Overview of maternal mortality in the United States. Semin Perinatol 2012;36:2–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Neggers YH. Trends in maternal mortality in the United States. Reprod Toxicol 2016;64:72–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rossen LM, Womack LS, Hoyert DL, Anderson RN, Uddin SFG. The impact of the pregnancy checkbox and misclassification on maternal mortality trends in the United States, 1999–2017. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2020;3:1–49 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moaddab A, Dildy GA, Brown HL, et al. . Health care disparity and pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2005–2014. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:707–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hawkins SS, Ghiani M, Harper S, Baum CF, Kaufman JS. Impact of state-level changes on maternal mortality: A population-based, quasi-experimental study. Am J Prev Med 2020;58:165–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sullivan SA, Hill EG, Newman RB, Menard MK. Maternal-fetal medicine specialist density is inversely associated with maternal mortality ratios. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;193(Pt 2):1083–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nelson DB, Moniz MH, Davis MM. Population-level factors associated with maternal mortality in the United States, 1997–2012. BMC Public Health 2018;18:1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Howell EA. Reducing disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2018;61:387–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Main EK, Markow C, Gould J. Addressing maternal mortality and morbidity in California through public-private partnerships. Health Aff 2018;37:1484–1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Bureau of Maternal, Infant and Reproductive Health. Pregnancy-associated mortality, New York City: 2006–2010. Available at: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/ms/pregnancy-associated-mortality-report.pdf Accessed July6, 2020

- 38. Maron D. Maternal health care is disappearing in rural America. Scientific American, 2017. Available at: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/maternal-health-care-is-disappearing-in-rural-america Accessed July6, 2020

- 39. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State-specific maternal mortality among black and white women—United States, 1987–1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1999;48:492–496 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Maternal mortality by state, 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/maternal-mortality/MMR-2018-State-Data-508.pdf Accessed July6, 2020

- 41. Hung P, Henning-Smith CE, Casey MM, Kozhimannil KB. Access to obstetric services in rural counties still declining, with 9 percent losing services, 2004–2014. Health Aff 2017;36:1663–1671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kozhimannil KB, Interrante JD, Henning-Smith C, Admon LK. Rural-urban differences in severe maternal morbidity and mortality in the US, 2007–2015. Health Aff. 2019;38:2077–2085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Washington State Department of Health. Washington state maternal mortality review panel: Maternal deaths 2014–2016. 2019. Available at: https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/Pubs/141-010-MMRPMaternalDeathReport2014-2016.pdf Accessed July6, 2020

- 44. Library of Congress. Current legislative activities. Available at: https://www.congress.gov Accessed July6, 2020

- 45. U.S. Senate Committee on Finance. Grassley, Wyden seek information, solutions to improve maternal health. 2020. Available at: https://www.finance.senate.gov/chairmans-news/grassley-wyden-seek-information-solutions-to-improve-maternal-health Accessed July6, 2020

- 46. Merck. Merck for mothers: Safer childbirth cities initiative, call to action to reverse the rise in U.S. maternal deaths. October 1, 2018. Available at: https://www.merckformothers.com/SaferChildbirthCities Accessed July6, 2020

- 47. American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists. 2013–16 safe motherhood initiative report. Available at: https://www.acog.org/community/districts-and-sections/district-ii/programs-and-resources/safe-motherhood-initiative Accessed July6, 2020

- 48. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstetric Care Consensus No. 9: Levels of maternal care. Obstet Gynecol 2019;134:883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Indian Health Service (IHS). IHS fact sheet: Maternal mortality and morbidity in Indian country. Available at: https://www.ihs.gov/dccs/mch Accessed July6, 2020

- 50. Congressional Research Service. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA): Maternal health programs. March 20, 2020. R46256. Available at: https://crsreports.congress.gov Accessed July6, 2020

- 51. Chakhtoura N, Chinn JJ, Grantz KL, et al. . Importance of research in reducing maternal morbidity and mortality rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221:179–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. National Institutes of Health, Office of Research on Women's Health. Maternal morbidity and mortality. Available at: https://orwh.od.nih.gov/research/maternal-morbidity-and-mortality Accessed July6, 2020

- 53. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Improving access to maternal health care in rural communities. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/equity-initiatives/rural-health/09032019-Maternal-Health-Care-in-Rural-Communities.pdf Accessed July6, 2020

- 54. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Postapproval pregnancy safety studies guidance for industry. 2019. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/postapproval-pregnancy-safety-studies-guidance-industry Accessed July6, 2020

- 55. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Office of Women's Health. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/office-commissioner/office-womens-health Accessed July6, 2020

- 56. California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative. QI initiatives. Available at: https://www.cmqcc.org/qi-initiatives Accessed July6, 2020

- 57. NYC Health + Hospitals. Press Release: De Blasio administration launches comprehensive plan to reduce maternal deaths and life-threatening complications from childbirth among women of color. 2018. Available at: https://www.nychealthandhospitals.org/pressrelease/comprehensive-plan-takes-maternal-safety-to-the-next-level Accessed July6, 2020

- 58. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736 Summary: Optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:949–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Searing A, Ross DC. Medicaid expansion fills gaps in maternal health coverage leading to healthier mothers and babies. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Health Policy Institute Center for Children and Families, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 60. Main EK, Menard MK. Maternal mortality: Time for national action. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:735–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Henderson ZT, Ernst K, Simpson KR, et al. . The national network of state perinatal quality collaboratives: A growing movement to improve maternal and infant health. J Womens Health 2018;27:221–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Vladutiu CJ, Minnaert JJ, Sosa S, Menard MK. Levels of maternal care in the United States: An assessment of publicly available state guidelines. J Womens Health 2020;29:353–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mann S, Hollier LM, McKay K, Brown H. What we can do about maternal mortality—And how to do it quickly. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1689–1691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Jain JA, Temming LA, D'Alton ME, et al. . SMFM Special Report: Putting the “M” back in MFM: Reducing racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality: A call to action. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218:B9–B17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Victor RG, Lynch K, Li N, et al. . A cluster-randomized trial of blood-pressure reduction in black barbershops. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1291–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G, et al. . Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2199–2207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hagiwara N, Elston Lafata J, Mezuk B, Vrana SR, Fetters MD. Detecting implicit racial bias in provider communication behaviors to reduce disparities in healthcare: Challenges, solutions, and future directions for provider communication training. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102:1738–1743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mhyre JM, D'Oria R, Hameed AB, et al. . The maternal early warning criteria: A proposal from the national partnership for maternal safety. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:782–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Krok-Schoen JL, Oliveri JM, Paskett ED. Cancer care delivery and women's health: The role of patient navigation. Front Oncol 2016;6:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Corbett CM, Somers TJ, Nunez CM, et al. . Evolution of a longitudinal, multidisciplinary, and scalable patient navigation matrix model. Cancer Med 2020;9:3202–3210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Fouad MN, Acemgil A, Bae S, et al. . Patient navigation as a model to increase participation of African Americans in cancer clinical trials. J Oncol Pract 2016;12:556–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Council on Patient Safety in Women's Health Care. Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health. Safety health care for every women. 2015. Available at: https://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org Accessed July6, 2020