Abstract

Background

HIV self-tests increase HIV status awareness by providing convenience and privacy, although cost and access may limit use. Since 2015, the New York City (NYC) Health Department has conducted five waves of an online Home Test Giveaway.

Methods

We recruited adult cisgender men who had sex with men (MSM) and transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) individuals who had sex with men, living in NYC, who were not previously HIV-diagnosed, using paid digital advertisements (4–8 weeks per wave). Eligible respondents were emailed a code to redeem on the manufacturer’s website for a free HIV self-test and an online follow-up survey ~2 months later. For key process and outcome measures, we present means across five waves.

Results

Over five waves of Home Test Giveaway, there were 28,921 responses to the eligibility questionnaire; 17,383 were eligible; 12,182 redeemed a code for a free HIV self-test; and 7,935 responded to the follow-up survey (46% of eligible responses). Among eligible responses, approximately half were Latino/a (mean: 32%) or non-Latino/a Black (mean: 17%). Mean report of never-testing before was 16%. Among 5,903 follow-up survey responses that reported test use, 32 reported reactive results with no known previous diagnosis (0.54%), of whom, 78% reported receiving confirmatory testing. Report of likelihood of recommending the Home Test Giveaway to friends was high (mean: 96%).

Conclusions

We recruited diverse NYC MSM and TGNC and distributed a large number of HIV self-tests to them. Among respondents who reported newly reactive tests, the majority reported confirmatory testing. This appears to be one acceptable way to reach MSM and TGNC for HIV testing, including those who have never tested before.

Keywords: HIV, HIV testing, HIV self-test (HIVST)

Summary

Through the Home Test Giveaway, the NYC Health Department successfully distributed 12,182 HIV self-tests to a diverse group of men and transgender individuals who have sex with men.

Introduction

HIV self-tests, available over-the-counter at pharmacies in the United States since 2012,1 offer a convenient and private way to test for HIV and have been shown to increase frequency of HIV testing among men who have sex with men (MSM) in clinical trials.2–4 However, cost and access may limit use outside of research settings.5–8 To address these barriers, the New York City (NYC) Health Department has conducted the online Home Test Giveaway, in which HIV self-test are purchased in bulk at a reduced cost by the NYC Health Department and are mailed at no cost to cisgender MSM and transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) individuals who have sex with men. These groups are among those with the highest burden of HIV in NYC, where there are approximately 2000 new HIV diagnoses annually.9 We describe the Home Test Giveaway 2015–2018, including the intervention’s process and outcome measures.

Materials and Methods

Recruitment

The Home Test Giveway intervention and its recruitment was informed by focus groups with community stakeholders. Recruitment of MSM and TGNC individuals occurred through paid digital advertisements displayed on social media and mobile dating applications, and websites over 5 “waves” (Appendix, Figure 1). Each wave consisted of limited-time advertising campaigns [Wave 1 (“pilot”): November 2015- December 2015; Wave 2: June 2016-August 2016; Wave 3: November 2016-January 2017; Wave 4: May 2017-July 2017; Wave 5: December 2017-Febuary 2018]. Advertisements hyperlinked to an eligibility questionnaire.

Following Wave 1 (the “pilot”), subsequent waves incorporated innovations in response to findings and discussions with stakeholders. This included broadened marketing across web platforms (Waves 2–5); images of TGNC individuals in advertisements (Waves 4–5); and Spanish-language materials (Waves 3–5). Recruitment was expanded in collaboration with New York State (NYS) Department of Health to NYC-adjacent counties (Wave 3), and statewide (Wave 4–5) (data not shown here).10

Eligibility

Eligibility was limited to MSM or TGNC living in NYC who reported sex with men in the past 12 months, ≥ 18 years of age, and no prior HIV diagnosis. The eligibility questionnaire also captured information on race/ethnicity and prior HIV testing history (ever/never tested, time since last test). Eligible respondents were emailed a “discount code” to be redeemed on the manufacturer’s website for a free HIV self-test (Orasure Technologies, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania USA). Efforts were made to provide only one discount code per person per wave (e.g., through deduplication by email address), with no such restriction across waves. Eligible respondents could redeem their discount code for up to two weeks following the close of advertising.

Receipt of HIV Self-Test

HIV self-tests were mailed in nondescript packaging directly from the manufacturer, accompanied by informational inserts developed by NYC Health Department with on HIV testing and pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP and PEP) (Appendix, Figure 2); specifically, these inserts addressed the window period of the test, symptoms of acute HIV and how to pursue testing in that context, basic information about PrEP and PEP, and how to access them.

Follow-up Survey

Approximately two months after each wave of HIV self-test distribution concluded, eligible respondents were emailed a link to an online follow-up survey and asked to complete it within four weeks. Survey completion was incentivized with a $25 gift card and reminder emails were sent with the survey link. The follow-up survey included questions about socio-demographics (education, annual income, health insurance), information on the Home Test Giveaway study flow (received self-test; used self-test), HIV self-test result and, if appropriate, confirmatory testing and HIV care; and to self-test users, feedback on the Home Test Giveaway experience (how soon used self-test, tested sooner because of Giveaway, likelihood of recommending Giveaway to friends) and feedback on self-test use (what respondent liked about it, how much they are willing to pay for HIV self-test).

Analysis

Analyses presented here include measures of process (study flow and respondents’ characteristics) and outcomes (respondents’ HIV self-test results and experience with HTG). For most key measures, we present simple means across the five waves HTG (“mean”) of frequencies (∑(N)/5) and percents (∑[(n/N)*100)]/5), as well as ranges across the five waves (“range”). For the outcomes measure of self-test results, data are presented as proportion of total tests reported through the follow-up surveys. Data analyses were conducted using SAS Analytics Software 9.4.

The Home Test Giveaway project was reviewed and approved by the NYC Health Department Institutional Review Board.

Results

Home Test Giveaway Study Flow

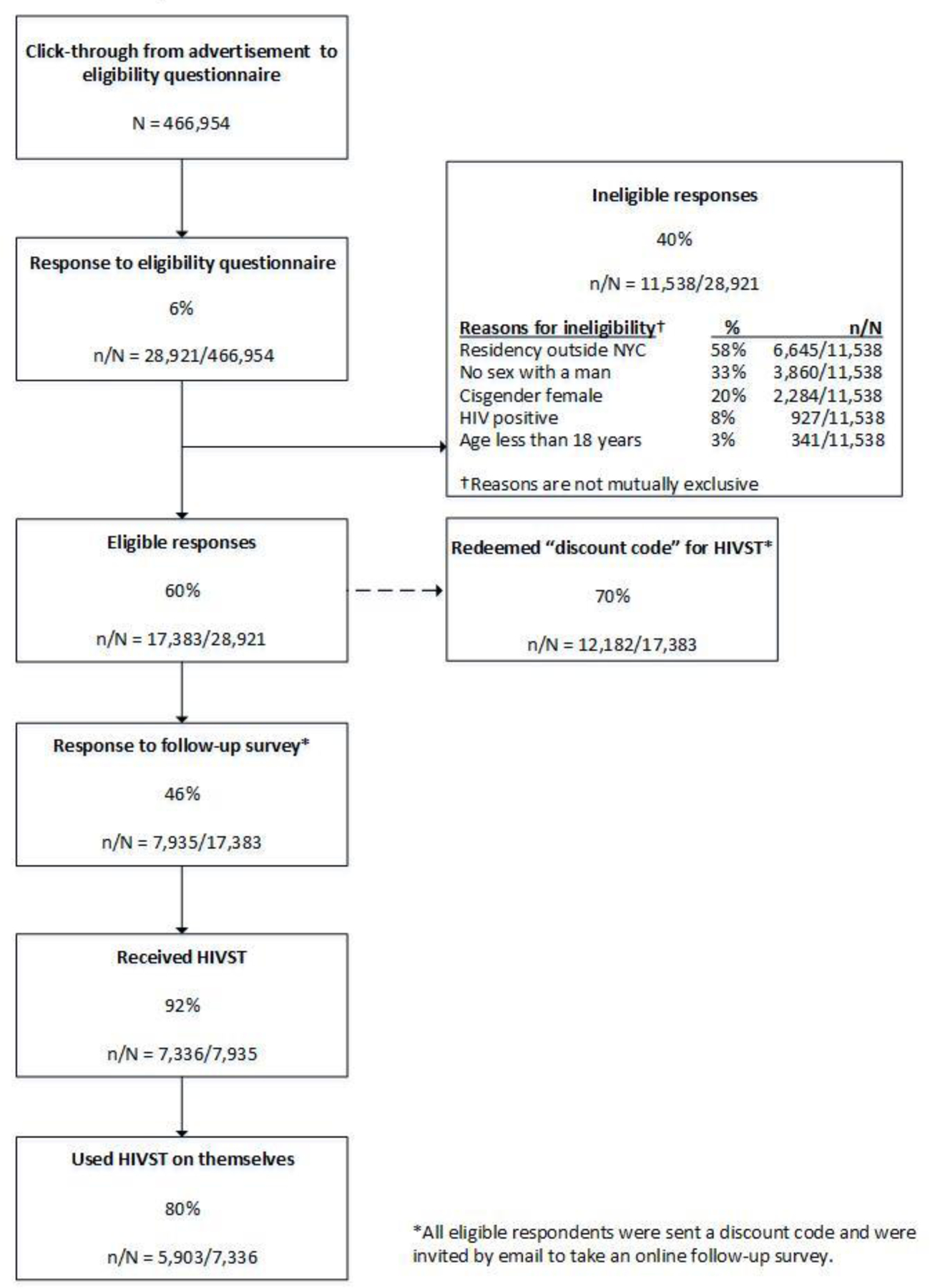

Over five waves, there were 466,954 click-throughs from online advertisements to the eligibility questionnaire (mean: 93,391; range: 39,605–115,337) resulting in 28,921 responses to the eligibility questionnaire (6% of clicks) and 17,383 eligible responses (60% of all responses) (Figure 1; Appendix, Table 1). The most common reason for ineligibility was residency (outside of NYC for Waves 1–2, outside NYC and NYS for Waves 3–5). Among eligible responses, there were 12,182 discount code redemptions for a free HIV self-test (70% of eligible responses) and 7,935 responses to the follow-up survey (46% of eligible responses). Among follow-up survey responses, 7,336 reported receiving a self-test (92% of follow-survey responses) and among them, 5,903 reported using the self-test to test themselves (80% of those who reported receiving an self-test). Among those who did not use the self-test, 5% reporting using the test for someone else and 14% reported not using the test. Among the latter, 90% reported that they planned to use it in the future.

Figure 1.

Study Flow throughout NYC Health Department Online Home Test Giveaway Program across Five Waves, 2015–2018

Characteristics throughout Home Test Giveaway Study Flow

Table 1 displays the distribution of demographic characteristics of respondents across the Home Test Giveaway study flow. Among eligible respondents, most were either 18–24 years old (mean: 23%) or 25–35 years-old (mean: 49%) and cisgender-men (mean: 97%); approximately half were Latino/a (mean: 32%) or non-Latino/a Black (mean: 17%). Mean report of never-testing before the Home Test Giveaway was 16% (range: 14–21%) and last test >1 year ago was 21% (range: 17–28%). Among eligible respondents who also responded to the follow-up survey, a majority had college education or more (mean: 62%), approximately half had an annual income of <$40,000 (mean: 49%) and one quarter were uninsured (mean: 23%). Respondent demographic characteristics were relatively comparable to the eligible respondents across the study flow (redeemed a code for an HIV self-test; responded to the following-up survey; reported using the test).

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics across Five Waves of NYC Health Department Online Home Giveaway Program Respondents, 2015–2018

| Eligible respondents N=17,383 | Eligible respondents who redeemed “discount code” N=12,182 | Follow-up survey respondents N=7,935 | Follow-up survey respondents who used HIV self-test N=5,903 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean percent* across five waves (range) | Mean percent* across five waves (range) | Mean percent* across five waves (range) | Mean percent* across five waves (range) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–24 | 23 (20–24) | 23 (21–24) | 22 (19–24) | 24 (21–26) |

| 25–34 | 49 (47–52) | 51 (49–54) | 51 (49–55) | 52 (50–57) |

| 35–44 | 18 (15–19) | 17 (15–19) | 17 (14–20) | 16 (13–19) |

| 45 or older | 10 (9–12) | 9 (8–10) | 9 (8–11) | 8 (7–9) |

| Race/ethnicity† | ||||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 17 (14–18) | 15 (12–17) | 15 (11–17) | 16 (11–19) |

| Hispanic/Latino/a | 32 (29–−35) | 31 (29–34) | 30 (25–33) | 31 (28–35) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 11 (10–14) | 11 (10–12) | 12 (11–12) | 11 (11–13) |

| Multiple and/or other races | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 36 (32–40) | 38 (33–43) | 39 (32–43) | 38 (30–43) |

| Gender | ||||

| Cisgender men | 97 (95–99) | 97 (95–99) | 97 (95–99) | 98 (95–99) |

| TGNC‡ or another gender | 3 (1–3) | 3 (1–5) | 3 (1–5) | 2 (1–5) |

| Time Since Last HIV Test | ||||

| Never | 16 (14–21) | 15 (13–21) | 15 (12–22) | 17 (13–26) |

| 0–3 months | 15 (12–18) | 14 (11–17) | 15 (12–19) | 12 (9–16) |

| 4 – 6 months | 24 (22–26) | 25 (22–28) | 26 (24–29) | 27 (26–30) |

| 7–12 months | 21 (20–23) | 22 (21–24) | 22 (21–24) | 22 (21–24) |

| >1 year | 21 (17–28) | 21 (17–28) | 19 (16–27) | 19 (15–28) |

| Do not know | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) |

| Highest Level of Education§ | ||||

| Did not graduate high school | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–5) |

| High school or GED | 10 (7–16) | 10 (7–16) | 10 (7–16) | 11 (8–18) |

| Some college or technical school | 24 (21–26) | 23 (21–24) | 24 (21–26) | 25 (21–26) |

| College or graduate degree | 62 (55–70) | 63 (56–71) | 62 (55–70) | 61 (52–70) |

| Annual Income§ | ||||

| Less than $40,000 | 49 (41–56) | 48 (41–57) | 49 (41–56) | 51 (42–59) |

| $40,000 or greater | 51 (44–59) | 52 (43–59) | 51 (44–59) | 49 (41–58) |

| Insurance Status§ | ||||

| Insured | 77 (68–82) | 77 (67–82) | 77 (68–82) | 74 (64–80) |

| Uninsured | 23 (18–27) | 23 (18–33) | 23 (18–32) | 26 (20–36) |

Mean percent was calculated as the average proportion across the five waves of Home Test Giveaway Program (∑[(n/N)*100)]/5). Responses of “Do not know” or “Decline to answer” were excluded from calculations and are not listed in the table.

Race/ethnicity was asked as a multi-select question. Responses are reported as mutually exclusive categories. Respondents selecting “Hispanic/Latino/a“ and additional race/ethnicity categories are reported as “Hispanic/Latino/a;” respondents selecting multiple race/ethnicity categories which do not include “Hispanic/Latino/a” are reported as “Multiple and/or other races.”

TGNC=Transgender and gender nonconforming individuals

Data only available among respondents who completed the follow-up survey within the wave of eligibility questionnaire completion. Response to follow-up surveys ranged from 34–54% across the five waves.

HIV Self-Test Results and Care from Follow-up Survey

Among all follow-up responses, 43 reported reactive results (0.73% of HIV self-tests used), of whom 32 reported no known previous HIV diagnosis (0.54%; approximately 1 in 185 self-tests) (Appendix, Table 2). Among those with no known previous diagnosis, 25 (78%) reported receiving confirmatory testing; of whom, 84% reported receiving a confirmatory positive; of whom, 95% had their first HIV care appointment; and of whom, 85% had started treatment at the time of the follow-up survey.

Home Test Giveaway and HIV Self-Test Feedback from Follow-up Survey

Most follow-up survey respondents who used the HIV self-test, reported use within 1 week of receipt (mean: 71%, range: 68–73%) and testing sooner or for the first time because of the Home Test Giveaway (mean: 70%, range: 64–76%). Likelihood of recommending the Home Test Giveaway to friends was high (mean: 96%, range: 92–98%). Respondents reported liking the privacy (mean: 71%, range: 62–83%) and convenience (mean: 68%, range: 59–91%) of home testing, though fewer would be willing to pay the estimated retail cost of $40 for an HIV self-test (mean: 30%, range: 22–39%).

Discussion

Between 2015 and 2018, we consistently recruited and distributed a large number of HIV self-tests to individuals in groups who disproportionately affected by HIV in NYC9: MSM and TGNC who have sex with men. Additionally, almost half of eligible respondents were either Black or Latino, most were under age 35 and over a third of whom had not tested in the last year. Follow-up survey respondents reported self-test results and high levels of follow-up among those with reactive results. Positive feedback from respondents suggests that this is one acceptable to way to reach MSM and TGNC persons for HIV testing.

This Home Test Giveaway intervention demonstrated consistent distribution of a large number of HIV self-tests over a relatively short period of time through online recruitment, with substantial follow-up participation. Other methods for free HIV self-test distribution to MSM in the literature include vouchers,11 vending machines,12 bathhouses13 and social networks.14,15 All of these methods have the potential benefit of finely tuned recruitment to individuals who may be at increased risk of acquiring HIV, including those who may not be online. Our study and others have found that reaching MSM to distribute HIV self-tests through online advertisements16,17 or applications18 is not only feasible but can allow for a wider distribution of HIV self-tests rapidly. Although almost half of eligible respondents in the Home Test Giveaway were either Black or Latino/a, a proportion similar to other HIV prevention programs in NYC,19,20 throughout the waves described here and ongoing we have worked with stakeholders to improve participation level of these priority populations. Additionally, although the Home Test Giveway program was able to recruit TGNC respondents, other recruitment strategies may be needed to increase participation, which could include respondent-driven sampling21 and greater collaboration with organizations that support TGNC.

The consistent proportion of respondents who reported never-testing has been considered a key indicator of the Home Test Giveaway’s success. At an average of 16%, the proportion never-testing exceeds estimates from the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS) 2017 surveys conducted among MSM across 23 US cities (range: 0.08–11.6%; 3.1% in NYC).22 The proportion never-tested in the Home Test Giveaway was also greater than what was reported by MSM and TGNC clients of NYC’s municipally-funded Sexual Health Clinics23 in 2017 (5.6%; personal communication K. Jamison) and of NYC-funded clinical and non-clinical HIV prevention programs24 in 2018 (3.5%; personal communication A. Merges). Although the Home Test Giveaway data were self-reported and therefore subject to recall error and social desirability bias, other programs that have distributed HIV self-tests online have also found relatively high proportions of never-testing (9%16; 12.8%17).

HIV self-test users reported their test results in follow-up survey responses across five waves. Although the rate of first-time positive results may not appear to be high, it is within the range of new diagnosis rates reported by US health-department-supported, CDC-funded testing programs in 2017: those in non-healthcare settings had a new diagnosis rate of 0.6% overall and 2% among MSM; in healthcare settings, it was 0.3% (rate among MSM unknown).25 The Home Test Giveaway data on HIV self-test results were from follow-up survey responses only and thus we do not know the results of all self-tests distributed or if the follow-up survey respondents were representative of all self-test users in the Home Test Giveaway, though the distribution of demographic characteristics were similar to those who were sent a self-test. Of those who reported reactive test results, rates of linkage to confirmatory testing and care were relatively high.

MSM and TGNC were encouraged to test for HIV through the Home Test Giveaway, a modality meant to complement the existing HIV testing programs in NYC. This method of free HIV self-tests can be adapted to other settings, with similar methods currently implemented in NYS10, Virginia26, and other jurisdictions. Cost of the self-test has been shown consistently to be a barrier for use and this intervention helps surmount this for participants and transfers the financial burden to the public health entity conducting the program. In the cases where additional modifications may be needed to minimize programmatic costs, this can include advertising through different means (e.g., through social media posts or community-based organizations), limiting self-test purchase by prioritizing those in greatest need, and reducing use of follow-up survey incentives (e.g., by holding a raffle). Modifications needed to reach different populations should be explored with input from community stakeholders. Interventions such as this one help address the HIV diagnosis pillar of the national Ending the HIV Epidemic plan27 and should be considered as additional funds become available for implementation of this plan.

Supplementary Material

Appendix, Figure 1. Example Paid Digital Advertisements from Five Waves of NYC Health Department Online Home Giveaway Program, 2015–2018

Appendix Figure 2. (1) HIV Testing and (2) PrEP/PEP Inserts from Five Waves of NYC Health Department Online Home Giveaway Program, 2015–2018 *

Appendix, Table 1. Report of HIV Self-Test results and care among follow-up survey responses who reported using the HIV Self-Test from NYC Health Department Online Home Test Giveaway Program, 2015–2018

Sources of Support:

This work was supported by the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention (NCHHSTP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (PS12-1201 and PS18-1802). Author D.K. received additional support from the University of Washington/Fred Hutch Center for AIDS Research (NIH P30 AI027757). For the research reported in this publication, author L.P. was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32AI114398. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Federal Drug Adminstration. July 3, 2012 Approval Letter, OraQuick In-Home HIV Test 2012; https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/approved-blood-products/july-3-2012-approval-letter-oraquick-home-hiv-test. Accessed Jan 5, 2020, 2020.

- 2.Jamil MS, Prestage G, Fairley CK, et al. Effect of availability of HIV self-testing on HIV testing frequency in gay and bisexual men at high risk of infection (FORTH): a waiting-list randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV June 2017;4(6):e241–e250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz DA, Golden MR, Hughes JP, Farquhar C, Stekler JD. HIV Self-Testing Increases HIV Testing Frequency in High-Risk Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr August 15 2018;78(5):505–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson CC, Kennedy C, Fonner V, et al. Examining the effects of HIV self-testing compared to standard HIV testing services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc May 15 2017;20(1):21594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myers JE, Bodach S, Cutler BH, Shepard CW, Philippou C, Branson BM. Acceptability of home self-tests for HIV in New York City, 2006. Am J Public Health December 2014;104(12):e46–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myers JE, El-Sadr Davis OY, Weinstein ER, et al. Availability, Accessibility, and Price of Rapid HIV Self-Tests, New York City Pharmacies, Summer 2013. AIDS Behav February 2017;21(2):515–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nunn A, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Rose J, et al. Latent class analysis of acceptability and willingness to pay for self-HIV testing in a United States urban neighbourhood with high rates of HIV infection. J Int AIDS Soc January 17 2017;20(1):21290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lippman SA, Moran L, Sevelius J, et al. Acceptability and Feasibility of HIV Self-Testing Among Transgender Women in San Francisco: A Mixed Methods Pilot Study. AIDS Behav April 2016;20(4):928–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.HIV Epidemology and Field Services Program. HIV Surveillance Report, 2017 New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene: New York, NY. November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson MC, Chung R, Leung SY, et al. Combating Stigma Through HIV Self-Testing: New York State’s HIV Home Test Giveaway Program for Sexual Minorities. J Public Health Manag Pract February 4 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marlin RW, Young SD, Bristow CC, et al. Piloting an HIV self-test kit voucher program to raise serostatus awareness of high-risk African Americans, Los Angeles. BMC Public Health November 26 2014;14:1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stafylis C, Natoli LJ, Murkey JA, et al. Vending machines in commercial sex venues to increase HIV self-testing among men who have sex with men. Mhealth 2018;4:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods WJ, Lippman SA, Agnew E, Carroll S, Binson D. Bathhouse distribution of HIV self-testing kits reaches diverse, high-risk population. AIDS Care 2016;28 Suppl 1:111–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lightfoot MA, Campbell CK, Moss N, et al. Using a Social Network Strategy to Distribute HIV Self-Test Kits to African American and Latino MSM. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr September 1 2018;79(1):38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wesolowski L, Chavez P, Sullivan P, et al. Distribution of HIV Self-tests by HIV-Positive Men Who Have Sex with Men to Social and Sexual Contacts. AIDS Behav April 2019;23(4):893–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosengren AL, Huang E, Daniels J, Young SD, Marlin RW, Klausner JD. Feasibility of using Grindr(TM) to distribute HIV self-test kits to men who have sex with men in Los Angeles, California. Sex Health May 23 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Grov C, Westmoreland DA, Carneiro PB, et al. Recruiting vulnerable populations to participate in HIV prevention research: findings from the Together 5000 cohort study. Ann Epidemiol July 2019;35:4–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan PS, Driggers R, Stekler JD, et al. Usability and Acceptability of a Mobile Comprehensive HIV Prevention App for Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Pilot Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth March 9 2017;5(3):e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pathela P, Jamison K, Blank S, Daskalakis D, Hedberg T, Borges C. The HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) cascade at NYC Sexual Health Clinics: Navigation is the Key to Uptake. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr January 3 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myers J, Merges A, Saleh L, et al. Building a Citywide Network for Prevention Navigation: Year One of New York City’s PlaySure Network. National HIV Prevention Conference 2019. Atlanta, Georgia 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakelsky S, Moore L. Strategies to Engage Los Angeles County’s Trans-Identified Community in PrEP Social Marketing Campaign Evaluation. National HIV Prevention Conference 2019. Atlanta, Georgia 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control (CDC). HIV Infection Risk, Prevention, and Testing Behaviors Among Men Who Have Sex With Men—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 23 U.S. Cities, 2017. HIV Surveillance Special Report 22. 2019; https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Accessed 9/9/2019, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Sexual Health Clinics 2016; https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/services/sexual-health-clinics.page. Accessed 10/1/2019, 2019.

- 24.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. PlaySure Network for HIV Prevention 2017; https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/providers/resources/playsure-network.page. Accessed 10/1/2019, 2019.

- 25.Centers for Disease Control (CDC). CDC-Funded HIV Testing: United States, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, 2017 2018; https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/cdc-hiv-funded-hiv-testing-report-2017.pdf. Accessed Sept 20, 2019.

- 26.Collins B “Discreet”: characteristics of MSM in a Virginia home testing program and reasons for requesting a home test kit. National HIV Prevention Conference 2019. Atlanta, GA 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Health and Human Services. What is ‘Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America’? 2019; https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview. Accessed Jan 13, 2020, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix, Figure 1. Example Paid Digital Advertisements from Five Waves of NYC Health Department Online Home Giveaway Program, 2015–2018

Appendix Figure 2. (1) HIV Testing and (2) PrEP/PEP Inserts from Five Waves of NYC Health Department Online Home Giveaway Program, 2015–2018 *

Appendix, Table 1. Report of HIV Self-Test results and care among follow-up survey responses who reported using the HIV Self-Test from NYC Health Department Online Home Test Giveaway Program, 2015–2018