Abstract

To clarify how smoking leads to heart attacks and stroke, we developed an endothelial cell model (iECs) generated from human induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSC) and evaluated its responses to tobacco smoke. These iECs exhibited a uniform endothelial morphology, expressed markers PECAM1/CD31, VWF/von Willebrand Factor, and CDH5/VE-Cadherin, and exhibited tube formation and Acetyl-LDL uptake comparable to primary endothelial cells (EC). RNA sequencing (RNAseq) revealed a robust correlation coefficient between iECs and EC (R = 0.76), whereas gene responses to smoke were qualitatively nearly identical between iECs and primary ECs (R=0.86). Further analysis of transcriptional responses implicated eighteen transcription factors in regulating responses to smoke treatment, and identified gene sets regulated by each transcription factor, including oxidative stress, DNA damage/repair, ER stress, apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest. Assays for 42 cytokines in HUVEC cells and iECs identified 23 cytokines that responded dynamically to cigarette smoke. These cytokines and cellular stress response pathways describe endothelial responses for lymphocyte attachment, activation of coagulation and complement, lymphocyte growth factors, and inflammation and fibrosis; EC-initiated events that collectively lead to atherosclerosis. Thus, these studies validate the iEC model and identify transcriptional response networks by which ECs respond to tobacco smoke. Our results systematically trace how ECs use these response networks to regulate genes and pathways, and finally cytokine signals to other cells, to initiate the diverse processes that lead to atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Tobacco use is a leading cause of preventable deaths. Cigarette smoking kills most commonly by acting on the vasculature to cause heart attacks and strokes, although cancers are also common and have received most attention1, 2. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has announced its intent to regulate various forms of nicotine delivery including cigarettes, water pipes, vaping, and others.3 With such variety among these products and practices, it would be useful to thoroughly understand the effects of the principal components of tobacco products, both the pathways impacted, and the critical concentration at which individual components act. Such quantitative and qualitative information would facilitate regulation of individual chemicals in these products. Such systematic studies demand a cell model for the endothelium that reacts to smoke like primary endothelium, is experimentally tractable, and can be prepared in large and reproducible lots.

Vascular endothelial cells are sentinels, responding to toxicants in smoke by regulating coagulation, vascular tone, and inflammatory signaling to lymphocytes and surrounding tissue.4 Tobacco alters the vascular wall, causing local leukocyte adhesion, inflammation and fibrin deposition, vascular mineralization, and ultimately atherosclerotic plaques within blood vessels that give rise to heart attacks and strokes. The difficulty in assessing the vascular toxicity that underlies heart attack and stroke is that measuring acute cell death does not reflect in vivo adverse events in the smoker. Instead, smoke causes cardiovascular toxicity5, 6 by attacking the vasculature chronically, causing hypoxia, oxidative and chemical damage to DNA, membranes, and proteins; and by provoking local and systemic inflammation that affects immune cells and the heart. Smoke causes this inflammation both directly, by exposing vasculature to volatile free radicals and nonvolatile toxic molecules and ‘PAMPS’ (Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns) such as bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS), and indirectly via inflammatory cytokine, and ‘DAMPS’ (Death-Associated Molecular Patterns) released by dying endothelial cells and lymphocytes4, 7, 8. Since tobacco insults to vascular endothelium lead to systemic inflammatory cytokine signaling, these inflammatory cytokines may be useful as biomarkers for assessing the chronic inflammation caused by tobacco in vivo.

Recently, we developed a new cellular screening platform utilizing induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC)-derived endothelial cells (iEC) that can form tubes in vitro and express classical markers that are characteristic of blood vessels. iPSC-derived cells are advantageous because they can be generated in large numbers repeatedly from iPSC; whereas primary cells represent a limited resource from a given donor. Additionally, iECs enable one to survey endothelial cells derived from multiple genetically-distinct patients. In this study we compare the iEC model to primary human endothelial cells from three vascular beds by genome-wide transcriptional profiling. iECs were also assessed and compared to HUVEC primary endothelial cells by treating each with tobacco smoke and assessing their complex elaboration of cytokine hormones. The similarity in genome-wide transcriptional responses as well as cytokine responses establishes iECs as a viable model for study of responses to tobacco smoke and smoke components.

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Generation of endothelial cells (iEC) from Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC)

Induced pluripotent stem cells (NC6) were generated from fibroblasts from a healthy normal donor as described9. iEC lines NC6–1 and NC6–2 were differentiated from iPSC lines that were derived independently from a single healthy patient. The iPSCs were maintained and propagated on Matrigel-coated plates in TeSR-E8 medium (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) as described previously9, including Recombinant Human (RH-) proteins. iPSCs reaching ~80% confluence were passaged and seeded at low density. After 24 hours culture, cells were induced for five days to become mesoderm progenitors in MDM (Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM, Invitrogen, Catalog#: 21056–023), Ham’s F-12 Nutrient Mix, GlutaMAX™ (Catalog#: Invitrogen, 31765–035) at 1:1 ratio supplemented with Albucult (RH-Albumin) (5 mg/mL/ml, Novozymes Delta), and a-Monothioglycerol (a-MTG; 3.9 ml per 100 ml; 350–450 μM, Sigma-Aldrich, Catalog#: M6145), Protein-free hybridoma mixture II (PFHMII) (5%) (Invitrogen, Catalog#:12040–077), Ascorbic acid 2 phosphate (50 μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, Catalog#: A 8960), Penicillin/streptomycin (50 U Pen G/50 mg streptomycin sulfate, Invitrogen, Catalog#: 15140122), Insulin Transferrin Selenium-X Supplement (Invitrogen, Catalog#: 515000560), RH-Vascular endothelial growth factor (RH-VEGF, 10 ng/ml, Invitrogen, Catalog#: PHC9394), and RH-Basic fibroblast growth factor (RH-bFGF, 10 ng/ml, Pepro Tech, Catalog#: 100–18B), and RH-Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4 (BMP4, 10 ng/ml R&D system, Catalog# 314-BP-050). The medium was replaced with Endothelial Cell Growth Medium-2 (EGM™-2, Lonza, Catalog# CC-3162) at day 6 to commit cells to the endothelial lineage. At seven days of induction, 50–70% PECAM1+ mesoderm progenitor cells were generated. PECAM1+ cells were selected using magnetic beads coated with anti-PECAM1 antibodies (Miltenyi Biotec, Catalog# 130–091-935) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The PECAM1+ cells were further cultured and expanded in Collagen I coated plates or dishes ( Corning, Catalog# 356240) with endothelial culture medium containing human endothelial-SFM (Invitrogen, Catalog#11111044) and EGM™-2 at 1:1 ratio for endothelial cells maturation and proliferation (Fig 1). As these iPSC-derived endothelial cells (iECs) became confluent, they were passaged into fresh Collagen I coated plates or dishes every 4–5 days.

Figure 1. Generation of endothelial cells from human iPS cells in fully defined conditions.

(A) iPSCs (1 × 105/well in 6-well microplate) were seeded onto Matrigel-coated plates with E8 Medium at day 0, and then the medium was changed to Modified Dulbecco’s Media (MDM) on the next day (day 1). Scale bars show 100 microns. After 7 days induction, PECAM1-positive cells were evaluated for endothelial marker proteins and phenotypes. (B) The “cobblestone” morphology of the iECs was maintained after multiple passages.

Primary endothelial cells (human aorta (HAEC), coronary artery (HCAEC), and umbilicus (HUVEC)) were purchased from Lonza and cultured in EGM™-2.

The karyotype of the iPSCs was analyzed by the WiCell Research Institute (Madison, Wisconsin, USA) using G-banding metaphase karyotype analysis. All cell lines demonstrated chromosomal stability and a normal karyotype. Cell line identities were verified by short tandem repeat profiling10 using genomic DNA extracted from iPSCs and their parental fibroblasts. This was performed by the WiCell Research Institute using the Promega Powerplex® 16 System for 15 loci plus amelogenin. The STR profiles indicated that all iPSC lines matched with their parental fibroblasts completely in 15 amplified STR loci. Cell lines were checked for mycoplasma contamination monthly using the MycoAlert™ Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza, Catalog# L07–318), and found to be free of mycoplasma.

2.2. Tube formation assay

Tube formation assay was performed as described by the manufacturer. Briefly, 3 × 103 iECs at passage five were plated per well of a 96-well microplate coated with 65 μl Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix (Corning Biosciences, Corning NY, USA), and cultured for 6 hrs. Following removal of medium, the cells were labeled by adding 100μl/well of 8 μl/ml BD calcein AM (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes NJ, USA, Catalog# 564061). Cells were incubated for 30–40 minutes, then photographed with a Zeiss fluorescent microscope. The number of branch points and tubule lengths were quantified using imageJ software11.

2.3. Immunofluorescent imaging

Cells for immunostaining were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained using antibodies for PECAM1/ PECAM1 and CDH5. Nuclei were visualized with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham MA, USA). Stained cells were photographed with a fluorescent microscopic system (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany)

2.4. Flow cytometry analysis (FACS)

Cultures for Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) analysis were dissociated into single cells using TrypLE TM Express Enzyme (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA, Catalog# 12605010) and stained using antibodies for the cell surface markers PECAM1 and CDH5 (Biolegend, San Diego CA, USA, Catalog#:303116 and 348515 respectively). Stained cells were collected and analyzed on MACSQuant flow cytometer (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany).

2.5. LDL uptake

Assay of Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) uptake was performed as described previously.12 Briefly, the iECs were incubated with 10 μg/ml acetylated LDL (Ac-LDL) labeled with 1,1’-dioctadecyl-3,3,3’,3’-tetramethylindo-carbocyanine perchlorate (DiI-Ac-LDL, Invitrogen, Catalog# L3484) for 4 h at 37°C. DiI-Ac-LDL uptake by cells was assessed and quantified by fluorescent microscopy. Subsequently, cultures were dissociated into single cells with TrypLE TM Express Enzyme for FACS analysis.

2.6. Tobacco Smoke extract

Tobacco smoke extract was prepared by bubbling air from burning cigarettes through cell growth medium containing 10% DMSO using a vacuum manifold apparatus, then filtering to remove insoluble tar. Eight University of Kentucky 3R4F reference cigarettes13 were burned in succession and the smoke was pulled by vacuum through a glass frit submerged in 50 mL of growth medium plus 10% DMSO at a flow rate of ~20 cm3 per minute. Each cigarette yields approximately 30.6 mg tar per cigarette13, so this smoke extract stock contains approximately 245mg tar/50 mL. Insoluble tar was removed by filtration through a 0.45 μm filter and the resulting (4.96 mg/mL tar equivalents) smoke extract stock solution was used to treat cells approximately 2 hours after preparation. This smoke extract stock solution was diluted 1:10 into 100 microliters per well of a 96-well microplate for cytotoxicity or cytokine assays, or into 1 mL per well of a 12-well microplate for gene expression studies resulting in treatments using 0.5 mg/mL tar equivalents.

2.7. RNAseq gene expression profiling

EC cultures were grown in three biological replicates for each experiment. iECs were prepared from two independently derived stem cell lines derived from a healthy subject, yielding cell lines NC6–1 and NC6–2. Three replicates were grown from each primary EC line, NC6–1 and NC6–2, and results were averaged for each gene. For each of the five cell lines, 3 replicate cultures were treated with smoke and 3 replicates were treated with vehicle. Following total RNA isolation, selection of mRNAs, and depletion of rRNAs, 93.4–95.2% of sequences mapped uniquely to the genome including 38.8–103 million mapped reads among the three replicates for each cell line and treatment. Total RNA samples were prepared from cultured cells using Qiaquick kit (Qiagen, Hilden Germany) and selected for polyA+ transcripts using the Qiagen Oligotex midi kit. Resulting samples were depleted of ribosomal sequences using two rounds of RiboZero Gold™, Illumina Inc. RNAseq sequencing was performed using the TruSeq® kit and Illumina HiSeq 2000 instrument by the NHLBI-NIH DNA Sequencing and Genomics Core.

2.8. Gene expression data analyses

RNAseq data were mapped to human genes according to Genome Reference Consortium Human genome build 38 (GRCh38) of the human genome using the STAR Aligner software. HTSeq-count was used to count the aligned reads in genomic features to produce count data for each annotated gene. Gene expression data are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus accession # GSE141136, and sample information are summarized in supplementary Table S1. The three replicates for each cell line-treatment group yielded between 34–91 million uniquely mapped reads. Gene count data were normalized between samples and statistical analysis was performed using DESeq. Two group statistical tests were performed in DESeq using the nbinomTest method which applies a Benjamini-Hochberg correction to provide an estimate of False Discovery Rate (FDR). Significant gene responses were defined as genes that showed ≥ 25 counts in at least one treatment group, exceeding 2-fold change, and < 0.1 FDR. According to these criteria, 10,804 genes responded to smoke in one or more endothelial cell lines and were included in the heat map in Figure 5. The threshold cutoff was increased to ≥ 3-fold when selecting genes for pathway analyses in order to favor quantitatively significant changes. PCA was performed from normalized read counts using the prcomp package in R with parameters set to center and scale the data. Each sample was represented by three biological replicates. 15,526 Genes that were represented by ≥25 counts in at least 3 samples were included for Principal Components Analysis (PCA) to explore variance of the control samples. A second PCA plot was derived from 13,201 smoke-responsive genes using the same gene filtering criteria to explore the variation associated with smoke treatment on primary cells and iECs.

Analyses to identify functional pathways and transcription factor s was performed using the Enrichr tool 14, 15. For TF analysis, 762 genes that responded to smoke in both iEC cell lines, or all three primary cell lines, by the criteria above were used to query Enrichr March 14, 2019. Gene sets that overlapped with the query set were compiled if the p < .05 and a maximum of 25 from each of seven data sources. Eighteen transcription factors were represented among two or more data sources, and the union of genes regulated in these gene lists were compiled for each TF. Functional enrichments for GO Biological Process terms were obtained by analysis of differentially expressed gene sets using the String DB web interface (https://string-db.org). The String DB Analysis page result file downloads include the data given in supplemental file S5, including GO Term ID, GO Term description, observed and background gene counts, false discovery rate and the list of matching proteins and corresponding gene symbols.

2.9. Cytokine Assays and Data Analysis

HUVEC primary endothelial cells and iECs were treated with smoke for 24 hours, then the growth medium was assayed for 42 cytokines relevant to vascular endothelium. Calf serum for these experiments was adsorbed to charcoal to lower the background levels of bovine cytokines. 42 cytokines were assayed on beads using the Human ProcartaPlex™ Panel1 Platinum kit (Thermo-Fisher Inc.) and quantified using a Luminex XMAP 3D instrument. A mix of the 42 cytokine standards was serially diluted and assayed to generate standard curves for each cytokine. Standard curves were plotted as Log2 [cytokine] vs. Log2 median fluorescence/bead and fit to a regression line for each cytokine assay for each experiment. The following cytokines were assayed: BDNF, Eotaxin, GM-CSF, GROα, HGF, IFNα, IFNγ, IL1a, IL1β, IL1RA, IL2, IL4, IL5, IL6, IL7, IL8, IL9, IL10, IL12p70, IL13, IL15, IL16, IL17A, IL20, IL21, IP-10, LIF, MCP2/CCL8, MIP1α, MIP1β, OPG, P-selectin, PDGF-BB, PECAM1, RANTES, SCF, TNFα, TNF-RII, tPA, TSLP, VEGF-A, and VEGF-D. HUVEC or iEC cells for cytokine assays were plated in EGM™−2 medium containing 2.5% fetal bovine serum depleted of bovine cytokines by dialysis (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #A3382001). The medium from triplicate samples were assayed and quantified by comparison to standards analyzed on the same day.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Differentiation of iPSCs toward endothelial cells (iECs)

We developed a stepwise protocol to differentiate human iPSCs into mesoderm precursors in feeder free and chemically defined conditions, followed by endothelial cell lineage commitment and maturation for seven days. Cellular morphology at each step is illustrated in Figure 1. Once the iECs became confluent, they were passaged every 4–5 days. At passage 3–5, the cells were used for further evaluation and characterization whereupon they maintained EC morphology and characteristics (Figure 1B).

3.2. Evaluation of iPSC-derived endothelial cells (iECs)

The iECs were expanded and propagated on collagen I- or fibronectin-coated plates and maintained typical “cobblestone” morphology like HUVECs (Fig 2A). iECs expressed characteristic endothelial markers PECAM1, vWF, and VE-cadherin at levels comparable to HUVEC as characterized by immunohistochemistry and FACS (Fig 2A). Notably, the iECs could be maintained in the culture condition that sustained the typical cobblestone morphology and maintained expression of endothelial cell protein markers PECAM1 and CDH5 until passage 15.

Figure 2. Evaluation of iPSC- derived endothelial cells (iECs) morphology and phenotypes.

(A) iECs derived from iPSC through mesoderm precursors showed typical endothelial cell morphology, and expressed characteristic EC markers (CD31/PECAM1, vWF/von Willebrand Factor, and CDH5, red) defined by immunofluorescent staining and FACS. Immunostaining used phycoerythrin or allophycocyanin (PE or APC). Nuclei were visualized with DAPI (Blue). Image bar: 100 μm. (B) In vitro angiogenesis, or tube formation functional assay for iPSC-derived iECs. iECs cultured on Matrigel formed vascular tube-like structures. Image bar: 200 μm. The total number of junctions and branch lengths of networks is shown (N=5). (C) The capacities of iEC or HUVEC for acetyl-LDL (Dil-Ac-LDL) uptake was determined by quantifying fluorescence in images captured by a microscope (image bar: 100 μm) and FACS (plots; N=5).

To further characterize iECs, we first performed a tube formation assay to test the function of iECs in vitro. The iECs successfully formed tube-like structures on Matrigel; exhibiting numbers of junctions and branch lengths resembling HUVECs (Fig 2B). The iECs were then tested for additional functional features of endothelial cells such as uptake of acetylated low-density lipoproteins (LDLs). The capacity of fluorescence-labelled acetyl-LDL uptake was almost comparable with those of HUVECs as determined by photographs of fluorescence expression and FACS analyses. (Fig 2C). Taken together, the results of morphology, phenotype, and function assays in vitro indicated that iPSC-derived ECs (iECs) resulting from our differentiation method behaved as functional ECs.

3.3. Comparison of primary endothelial cells from 3 blood vessels by RNAseq

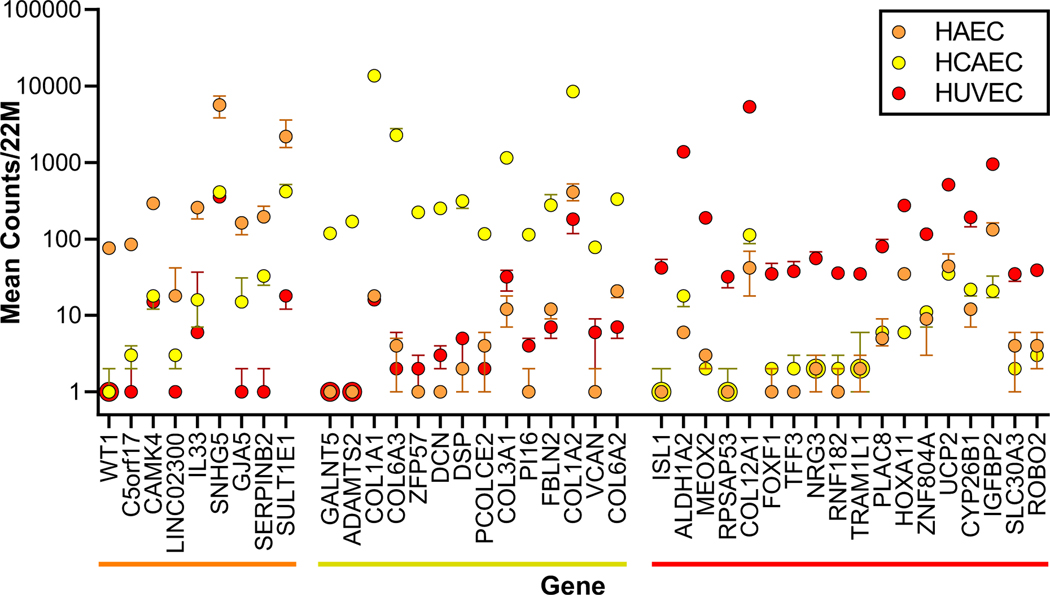

RNAseq gene expression profiling data were used to compare the transcriptional programs of endothelial cells from human aorta (HAEC), coronary artery (HCAEC), and umbilicus (HUVEC). These three cell types were cultured for 3–5 passages, treated with 0.5% DMSO vehicle for six hours, and analyzed by RNAseq. HCAEC, and HUVEC cells were derived from different donors, hence considerable variation is expected due to differences between patients for a given endothelial bed (e.g. see 16). Nevertheless, RNAseq data from these three EC beds were compared to look for marked differences in expression of genes and pathways markers and insights relevant to atherosclerosis, stroke or cardiac arrest. Figure 3 shows forty-one genes that were selectively expressed in HAEC, HCAEC, or HUVEC, hence may serve as useful markers or indicators of specialized functions of these vessels.

Figure 3. Genes expressed selectively in EC from human aorta, coronary artery, or umbilicus.

RNAseq data are shown for genes expressed at ten-fold higher counts in HAEC (orange) or HUVEC (red), or twenty-fold higher in HCAEC (yellow) relative to the average of the other two EC beds. For each gene the median number of transcripts per 22 million is plotted +/− the standard error for each EC bed. Zero transcript counts were plotted as 1 transcript to fit the logarithmic scale.

Marked differences among vehicle-treated primary EC types according to RNAseq results were plotted in Figure 3 and overall relationships were summarized using Principal Components Analysis (PCA) in Fig 4A. Despite overall similarities indicated by the PCA, some genes were expressed at characteristically higher levels in each of the three primary endothelium cultures that may be useful as cellular markers. The most selectively expressed genes included WT1, CAMK4, and GJA5 in HAEC, GALNT5 and ADAMTS2 in HCAEC, and GAA and NR1H3/LXRA in HUVEC (Figure 3). Ho et al.17 identified genes selectively expressed in HAEC or HCAEC, however they surveyed fewer than 672 genes using cDNA microarrays, and their results did not overlap with the selectively expressed genes from our analysis. Nolan et al. 18noted that GJA5 and DCN were differentially expressed in mouse heart relative to brain, and in iECs that express markers for heart EC (CXCR4) vs. brain EC (CD133), consistent with the selective expression in HAEC relative to HCAEC in our study. Looking beyond the forty-one genes shown in Figure 3, quantitative differences among these three vehicle-treated primary EC types were analyzed using the larger sets of significantly differentially expressed genes by pathway analysis(supplementary Table S2 and Table S3). The pathways identified showed prominent differences between EC beds in genes encoding extracellular matrix proteins or cell-surface proteins. For example, HCAEC-characteristic transcripts included robust expression of collagen genes COL1A1 and COL1A2, COL3A1, COL6A1, COL6A2, and COL6A3, as well as laminin genes LAMA3 and LAMB3. The COL6A genes are interesting since COL6A contributes to a vascular fibrotic response. The HAEC transcript profile was characteristic in abundant expression of transcripts encoding cell surface proteins LAMC2, KRT10, EFNA1, EFNB2, and PCDH17. Similarly, HUVEC cells expressed characteristic transcripts encoding COL12A1, COL13A1, CHD7, and EPHA5(supplementary Table S2 and Table S3). The large number of genes that were expressed at similar levels among the three primary endothelial cell beds were also assessed in iECs to compare primary ECs to iECs.

Figure 4. Gene expression comparison of iECs to primary endothelial cells.

(A) PCA relating gene expression profiles of vehicle-treated fibroblasts, blue squares; iPSCs, black triangles; HAEC, orange circles; HCAEC, yellow circles; HUVEC, red circles; and two iEC lines, green diamonds. Three biological replicates represent each cell line. (B) Scatter plot comparing baseline gene expression profiles of the mean expression level for the three primary cell beds and iEC lines. Squares represent genes that deviate by 3 standard deviations from the least squares regression line (gray).

3.4. Comparison of primary endothelial cells to iECs, without smoke treatment

Vehicle control samples were compared first, to understand the relatedness among the 3 primary endothelial cell beds, two iEC preparations from iPSC lines, as well as the iPSC lines, and fibroblasts that gave rise to the iECs (Figure 4A). To examine whether iECs resemble arterial or venous EC, we surveyed expression in our RNAseq data of arterial and venous EC marker genes in iECs and in HUVEC in comparison to HAEC and HCAECs. Marker genes defined in the mouse included, for arterial ECs: EPHB2, NRP1, HEY2, BMX, NOTCH1, and JAG1; and for venous ECs: EPHB4, NRP2, TEK, NR2F2, EMCN, and FLT4.19 Cultured HUVEC cells expressed all these genes robustly, at levels similar to expression in HAEC and HCAEC, except for HEY2, which was expressed at a lower level in HUVEC. iECs also expressed these twelve marker genes at similar levels to HAEC and HCAEC, except that HEY2 and BMX were expressed at markedly lower levels in iECs (see supplementary Table S4). Additionally, HAEC and HCAEC expressed venous markers as well as the arterial markers; both at robust levels. Thus, we conclude that since none of the four cultured cell lines shows a clear arterial or venous signature, arterial and venous ECs likely express these markers in response to different contextual signals in vivo, rather than as part of a hard-wired genomic program. Note that for pragmatic reasons, ECs were cultured without shear flow, a condition which is known to change the phenotype of ECs in vivo.20 Note also that the source of HUVEC, the umbilical vein, physiologically resembles an artery, in that it carries oxygenated blood, and is reinforced by vascular smooth muscle. These gene expression profile comparisons to venous and arterial EC markers collectively suggest that iECs derived in vitro have not been conditioned to in vivo contextual endothelial signals; hence are indeterminate in expressing both arterial and venous marker genes.

An unsupervised PCA overview of the relationships between the gene expression profiles of these seven cell lines is shown in Figure 4A. Principal component 1 separated fibroblasts and iPSC cell lines from primary endothelial cell-types and iECs. Principal component 2 additionally separated fibroblasts from iPSCs, but differences between primary endothelial cells and iECs were relatively small as described by the first two principal components. Figure 4B illustrates both the overall similarity in gene expression comparing iECs to the primary ECs (filled circles along diagonal), and some genes that were expressed selectively in iECs or in primary ECs (open squares along vertical and horizontal axes, respectively). We then further compared iECs to primary endothelial cells according to their responses to tobacco smoke.

3.5. Comparison of three primary endothelial cell beds’ responses to tobacco smoke

iECs and primary endothelial cells’ responses to treatment with tobacco smoke were assessed next using RNAseq whole-genome transcriptional profiling. HAECs, HCAECs, HUVECs and iECs were treated with tobacco smoke extract or vehicle (medium containing 10% DMSO) for six hours and subjected to RNAseq analysis to characterize their relatively short-term responses to favor direct effects. This experiment enabled identification of gene expression responses that were shared among all primary endothelial cell beds, and then responses that were either shared with iECs or unique to primary cell beds. iEC cell lines NC6–1 and NC6–2 were differentiated from iPSC lines that were derived separately from the dermal fibroblasts of a single healthy subject.

Gene expression responses to smoke were sought that were unique to individual primary cell beds; markers that may reveal differences in responses to smoke among between coronary artery, aorta and umbilical cord. Responses of various endothelial cell types to smoke treatment were summarized by a second PCA in Figure 5A. Figure 5A shows that primary EC cells are clustered closely in PC1, which accounts for 33.4% of the variation in the data set, but that upon smoke treatment all of the cell lines move upward similarly in PC2 accounting for 22.0% of the variation in the data set. Figure 5B is a heatmap illustrating the 8840 total gene responses to smoke by any cell line, including a detail that includes only the 2,285 genes that passed the significance criteria in more than one cell line. By our statistical criteria, genes that responded to smoke significantly in only one primary endothelial cell line comprised: 265 genes unique to HAEC, 175 genes unique to HCAEC, and 76 genes unique to HUVEC. Thus there were 516 gene responses to smoke that were statistically significant in only one of the three primary cell lines. Remarkably, however, nearly all of these 516 genes showed the same qualitative trend, increasing or decreasing in response to smoke in all three primary cell lines. Thus, nearly all of the differences between the three primary endothelial lines appear to be the result of arbitrary statistical boundaries with the exception of five genes that showed qualitative differences between the primary cell lines. These exceptions included GJA5 which was robustly expressed only in HAECs, and down-regulated sharply in all cell lines by smoke. Similarly, for HCAECs: ZFP57, HAND2 and HAND2 antisense RNA 1 were expressed only in HCAEC and down-regulated by smoke. In HUVEC cells, there were no genes that responded to smoke that did not respond with the same up- or downward trend in HAEC and HCAEC. In summary, primary endothelial cells from three different vessels reacted to smoke with many gene expression changes, but qualitatively, reacted very similarly.

Figure 5. Gene expression responses to tobacco smoke, comparing iECs to primary endothelial cells.

(A) PCA relating gene expression responses of the EC cell lines depicted in Figure 3 to tobacco smoke for six hours. Circles represent vehicle-treated cells, and triangles represent smoke-treated cells. (B) Heat maps comparing 8,840 genes that responded significantly to tobacco smoke in any of the five cell lines (left side). The right-side heat map shows only the 2,285 genes that responded significantly to smoke in both iECs or in all three primary EC types. Genes that increased or decreased in response to smoke are shown in red or green, respectively, with color saturation at 4-fold. Genes that did not change in response to smoke are shown in black, and genes with <25 normalized counts per sample are shown in grey. (C) Scatter plot showing gene expression responses to smoke, comparing iECs to mean values for the three primary EC types. Axes show Log2 fold-change values for smoke/vehicle-treatments. This scatterplot shows a spot for each of the 10,804 genes that yielded at least 25 counts from each cell type for either vehicle or smoke treatment. Black spots represent genes that responded significantly to smoke in three or more cell lines. The coefficient of correlation for the regression line R = 0.86.

3.6. Comparison of iECs’ vs. primary endothelial cell beds’ responses to tobacco smoke

The primary goal of these RNAseq studies was to evaluate iECs as a model for tobacco vascular toxicity by comparing how iECs and primary endothelial cells responded to tobacco smoke. In the Figure 5A PCA, principal component 1 separated the two iEC cell lines slightly from each other, but cleanly separated the two iEC cell lines from the three primary endothelial cell beds. Note that excluding fibroblasts and stem cells from Figure 5A enabled a greater separation between EC lines in this PCA. The second principal component for Figure 5A revealed a dramatic upward shift by all the smoke treated cell lines relative to the vehicle-treated cell lines. The upward shift of each of the primary endothelial cells and iECs while maintaining the same positions in PC1 indicated that smoke evoked similar responses from all five endothelial cell lines. Detailed responses of individual genes were examined in order to determine how iECs compared to primary ECs in individual gene- responses to smoke.

Significant gene responses to tobacco smoke are depicted by a detailed heat map in Figure 5B. Estimation of the False Discovery Rate revealed that < 10% of such significant changes are likely to be false positives. Overall, Figure 5B shows that the 3 primary endothelial cell lines were very similar in responses to smoke; whereas the two iEC cell lines were highly similar to one-another in responses to smoke, but moderately different from the primary lines. Figure 5C represents the 2,285 genes that responded to smoke in more than one cell line as a scatter plot in which iECs are compared to an average response among the three primary EC lines. The points in Figure 5C represent genes, describing a diagonal line with a correlation coefficient R = 0.86. Thus, there is a high degree of concordance between primary ECs and iECs in smoke responsive genes. In primary HCAEC, HAEC, and HUVEC cells, 894, 798, and 466 genes were significantly upregulated by smoke, respectively, including 288 genes that were significantly up- or down-regulated by smoke in all three primary cell types (Figure 5C). 221 of these 288 genes (76.7%) were also significantly upregulated in one or both iEC lines, and an additional 54 genes showed the same up- or down- trend. Indeed, of 288 gene responses to smoke in all three primary cell types, the iEC model exhibited the same increase or decrease trend in 275 (95.5%). Thus, the iEC model was approximately 95% concordant with the three primary endothelial cell types in qualitative gene responses to smoke. Close examination revealed five genes that did show marked differences between smoke responses in the iECs and primary cell types. PTGS2 and MIR31HG were up-regulated by smoke in the 3 primary cell lines but expressed at very low levels in iECs even upon treatment with smoke. PTGS2 encoding Cyclooxygenase 2 is known to be expressed in endothelial cells including aorta; however prior studies disagree as to whether it plays a pro- or anti-atherogenic role.21, 22 FAM101A, HOXA2 and RGS7BP were down-regulated by smoke in the 3 primary cell lines but expressed at very low levels in iECs. Among hundreds of genes that responded concordantly among primary and iECs, five genes reflected real differences between iECs and primary ECs, in each case based on low basal expression of these genes by control iECs.

3.7. Pathways that responded to smoke in iECs and HUVECs

Genes that were upregulated or downregulated in each cell type were used to identify biological processes triggered by smoke via searching the Biocarta pathways and Gene Ontology biological processes23, using the Enrichr tool14, 15 and the StringDB tool24. Table 1 summarizes the most significant biological process pathways identified by overlap with smoke-regulated genes. Since the smoke responses were highly similar among iECs and the three primary EC beds, we summarized the top-ranked pathways that were over-represented in HUVEC to represent primary ECs and compared to their representation in iECs (Table 1). It was striking that although many of these pathways were compiled from experiments in cell types unrelated to ECs, nevertheless, each of the pathways were similarly enriched in smoke-treated iECs and in HUVECs (Table 1). A more extensive list of pathways enriched in EC responses to smoke is presented in supplementary Table S5.

Table 1.

Biological Process Pathways Identified by Gene Sets Intersecting with EC Responses to Smoke.

| HUVEC rank | Pathway Accession | Regulated Genes | Pathway | HUVEC genes | iEC genes | Total Genes | HUVEC adj p-val |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BioCarta | |||||||

| 1 | h_arenrf2 | Up | Oxidative Stress Induced Gene Expression via Nrf2 | 4 | 6 | 18 | 0.001 |

| 2 | h_p53hypoxia | Up | Hypoxia and p53 in the Cardiovascular system | 3 | 3 | 21 | 0.024 |

| 1 | h_alk | Down | ALK in cardiac myocytes | 4 | 2 | 27 | 0.054 |

| GO Biological Process | |||||||

| 1 | GO:0036499 | Up | PERK-mediated unfolded protein response | 6 | 6 | 12 | 1.6 × 10−6 |

| 2 | GO:0043524 | Up | Negative regulation of neuron apoptotic process | 13 | 14 | 399 | 0.0061 |

| 3 | GO:0070059 | Up | Intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway in response to ER stress | 9 | 8 | 92 | 0.00015 |

| 1 | GO:0045944 | Down | Positive regulation of transcription from RNA pol. II promoter | 33 | 34 | 1175 | 0.067 |

| 2 | GO:0060331 | Down | Negative regulation of response to interferongamma | 5 | 3 | 15 | 0.0053 |

Table 1 lists “Total Genes” in each pathway, and the number of genes intersecting with the responses to smoke among “HUVEC Genes” or “iEC Genes”. Statistical Significance adjusted for multiplicity is shown for the intersection of the HUVEC smoke-responsive set and each pathway set as “HUVEC Adj p-val”.

Three BioCarta molecular pathways were enriched among smoke-responsive genes in HUVEC. Genes up-regulated by smoke were enriched for the oxidative stress response pathway driven by NRF2 binding to the Antioxidant Response Element, including HMOX1 encoding Heme Oxygenase. The hypoxia-driven p53 response pathway was also enriched in smoke-responsive genes, consisting of a set of genes regulated through p53, but distinct from those regulated by p53 following ionizing radiation. The 312 genes down-regulated by smoke in HUVEC were enriched for the ALK pathway (Activin receptor-Like Kinase pathway), a group of genes that responded to ALK3 expression. ALK3 is a gene that plays a central role in cardiac differentiation. This suggests that smoke down-regulated genes may interfere in differentiation of cardiac myocytes or ECs.

Genes enriched by smoke treatment were also compared to the hierarchical Gene Ontology biological process pathways. The ER Stress Pathway” and the near-synonymous Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) were implicated (Table 1; “PERK-mediated unfolded protein response”), including upregulation of canonical UPR genes XBP1, ATF3, HSPA5, and DDIT3. This event may reflect the chemical modification and denaturation of serum proteins in the growth medium, as well as proteins within the ECs. Smoke also up-regulated genes responsive to much-studied transcription factors (Figure 6) such as TP53 (response to DNA damage and oxidative stress), NRF2/NFE2L2 (oxidative stress), ATF3 (up-regulated by UPR, may suppress inflammation), NFkB subunit RELA (responds to a variety of stresses to regulate inflammation and survival), AP-1/FOS/JUN (responds to a variety of stresses), and ESR2/Estrogen Receptor β. Smoke down-regulated some genes that were enriched for the innate immunity pathway6, NOTCH pathway, as well as responses to inflammatory cytokines: IFNα/IFNγ, TNF, and IL1. Smoke also downregulated genes responsive to transcription factors GATA2, and ESR1/Estrogen Receptor a. Tobacco smoke is known to contain a variety of chemicals that are agonists or antagonists on the estrogen receptors25; but interestingly, our data indicate an overall up-regulation of ESR2-responsive genes, and downregulation of ESR1-responsive genes. Collectively, these seven pathways signify well-documented responses to oxidative stressors and to DNA damage caused by chemicals in cigarette smoke.

Figure 6. Eighteen TFs implicated in responses to smoke by primary ECs and iECs.

The heat map shows TF-regulated gene sets from Enrichr that overlapped with the 762 smoke responsive genes that responded to all three primary ECs or both iEC lines. These eighteen TF-associated gene sets showed significant overlap in two or more experimental sources in Enrichr. Light blue lines mark genes with direct cis-regulation of the gene by the TF (response element, ChIP-seq, or ChIP-chip). Black lines mark genes that were empirically observed to be regulated by the indicated TF, possibly indirectly in trans, in two datasets. Dark blue lines indicate both direct and empirical evidence. A dendrogram indicates intersecting gene sets among TFs. Among the TFs, the NFE2L2 gene encodes NRF2, ESR1 encodes the Estrogen Receptor α, and RELA and RELB encode NFκB family TFs.

3.8. Transcription Factors governing smoke responses

Comparison to published gene expression response datasets enabled the identification of eighteen transcription factors (TFs) that governed the responses to smoke observed in the RNAseq data in Figure 6. We required gene lists from two disparate data sources to match the query gene list in order to infer reliable TF-gene set associations. Briefly, 762 genes were identified that responded reliably to smoke in either all three primary cell beds, or both iEC cell lines. These 762 genes were used to query seven data sources compiled by the Enrichr tool that list gene sets that were associated with a single TF. The Enrichr TF datasets include microarray or RNAseq data, identification of significant response elements in gene promoters via TRANSFAC or JASPAR, and experimental treatments that agonize or antagonize a TF, introduce or knockdown a TF, or mapped TFs binding to gene promoters by ChIP-seq or ChIP-ChIP experiments14, 15. These data sources included datasets that are published, extracted from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) or derived from the ENCODE project14, 15. By identifying TF-regulated gene sets from Enrichr that overlapped with the 762 smoke responsive genes, eighteen TFs were identified that were significant in gene lists derived from two or more experimental sources.

Prior work has demonstrated activation of these transcription factor-driven pathways in endothelial cells, including TP53, NRF2, ATF3, NFkB, NOTCH, and ESR1. Thus, our data agree with and extend prior studies. For example, our data confirm the NRF2 response to oxidative stress, which protects endothelial cells through transcriptional induction of detoxifying genes such as HMOX1, and NQO1, and glutathione synthetic genes GCLC, GCLM, and SLC7A11 (Table S1,26,20,27). Tobacco smoke activation of transcription factor ATF3 has previously been shown to suppress inflammation in endothelium, likely by antagonizing NRF2 input to the NFkB pathway that regulates inflammatory cytokine genes .28 Our data are in agreement with activation of ATF3-regulated genes such as XBP1, TNFAIP3, ATF4, PTGS2, and heat shock genes HSPA8, HSPA5, HSPA1A, and HSPA1B. (Figure S1 and 28). Indeed, ATF3 activation in concert with NRF2 activation (clustered in Figure 6) may underlie the observed suppression of inflammation by antagonizing Toll-like suppressor 4 activity.28, 29

Figure 6 illustrates mapping of many of the 762 smoke-responsive genes to one or more of these eighteen TFs. These eighteen TFs include direct cis-responses to smoke components that imply TF binding to TF-response elements in the gene promoters by nuclear receptors. These cis-acting nuclear receptors included ESR1/Estrogen Receptor α, PPARγ metabolic regulator, and the VDR/Vitamin D Receptor. Relatively direct cis-responses were also identified to oxidative stress via the NFE2L2/NRF2 antioxidant response, to DNA damage via TP53, to protein denaturation via the ATF3 component of the ER Stress response and the Heat Shock Factor 1 (HSF1), and to inflammatory pathways via NFκB and two components of the NFκB:IFκB complex, RELA and RELB. Whereas activation of NFkB1 and RELA are generally pro-inflammatory, RELB expression may suppress inflammation e.g. in lungs of mice exposed to tobacco smoke 30,31. Several TFs that are known to respond to smoke components did not pass the stringent identification process, notably the ATF4 transcriptional response to ER stress that is nevertheless implicated by pathway analysis “PERK-mediated unfolded protein response” (Table 1), and the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AHR) response. The AHR response may have been missed due to the small number of responding genes, however classical AHR-induced genes CYP1A1, CYP1B1, and NQO1 mRNAs32 were increased by smoke in all five cell lines.

Other TFs responded indirectly, including STAT3 that responds to inflammatory cytokines, and JUN that forms part of the AP1 transcription factor that activates a common cell stress pathway in response to a variety of cell stresses. Still other TFs likely function as coregulators several steps downstream from cell stress stimuli, including NCOA1, FOXA1, CEBPB, HDAC2, TCF3, and ZBTB7A. NCOA1 encodes the Nuclear Receptor CoActivator 1 TF. NCOA1 forms complexes with STAT-family TFs and with nuclear receptors, so may cooperate in ECs with STAT3, or with other nuclear receptors such as VDR, PPARγ or ESR1/ERα33. NCOA1 and VDR regulation of genes-in-common in these ECs (Figure 6), suggests that NCOA1 may be part of the transcriptional regulatory complex with VDR. FOXA1, also called HNF3A, is thought to serve a “pioneer” function, by interacting with histones to open chromatin, translating DNA methylation signatures into cell type-specific enhancer-driven transcriptional programs34. In this way, FOXA1 facilitates cell differentiation, and modulates activity of nuclear receptors including Estrogen Receptor a and Androgen Receptor. TCF3 similarly regulates cellular differentiation, including lymphopoiesis and neuronal specification35. CEBPB encodes the CCAAT Enhancer Binding Protein β, a TF that plays roles in adipocyte differentiation and inflammatory reactions. CEBPB binds to other CEBPs or to ATF4, a regulator of the UPR, and can stimulate transcription of PPARγ36, 37. HDAC2 is a member of a family of histone deacetylase genes that remove acetyl groups from histones to “close” active chromatin. HDAC proteins act downstream of many transcription factors as effector proteins. ZBTB7A cooperates with RELA, Androgen Receptor and other TFs to close chromatin and repress transcription of genes necessary for cell growth or differentiation, including a response to DNA damage38. The NFκB-family transcription factors NFκB1, RELA, and RELB formed a cluster in Figure 6 reflecting regulation of intersecting gene sets. Along with c-REL and NFκB2, these five NFκB family members cooperate as homo- and hetero-dimers to regulate survival and apoptotic decisions, as well as inflammatory pathways including production of cytokines. These NFκB pathways mediate inputs from many other pathways, including NRF239, TP5340, HSF141, VDR42 as well as ATF3, JUN and STAT3.43 Thus, by identifying the TFs that regulate smoke-responsive genes, we can group coordinately regulated genes, and infer stimuli that regulate these gene clusters.

Among the eighteen TFs described in Figure 6, mRNAs were detected by RNAseq encoding all eighteen in all five EC cell lines. The mRNAs encoding fifteen TFs were robustly expressed in all five EC lines, whereas ESR1 was expressed weakly by all five EC lines, PPARγ was expressed robustly by HCAEC and HAEC and weakly by HUVEC and iECs, and FOXA1, which was expressed robustly by HCAEC but weakly by the other four EC lines. The mRNAs for the TFs: ATF3, CEBPB, and NFE2L2 were induced several -fold by smoke in all five EC lines. By mapping gene regulation events to TFs, these results revealed the complexity of transcriptional programs in ECs, and identified several TFs not previously associated with responses to smoke, such as FOXA1, ZBTB7A, and NCOA1 likely in cooperation with VDR.

3.9. Killing of iECs by smoke

In repeated experiments iECs were more easily killed by smoke than HUVEC primary cells. For example, after treating with smoke extract using 0.5 mg/mL tar equivalents, viability at 24 hours of iECs was 87.8% with a confidence interval of 85.6% to 90.1% (mean +/− 2SD), whereas viability of HUVECs was consistently 100%. Examination of the RNAseq data in control cells showed that genes that regulate the apoptotic balance, such as the BCL-family, were comparable in expression levels between the two cell types. On the other hand, genes encoding complement factor genes CFP and CFD, and contact system genes encoding Kallikreins KLK10, KLK13, and KLK14, were expressed at dramatically higher levels in iECs than in primary ECs. Conversely, CFH was expressed at a markedly lower level in iECs compared to a higher level in primary ECs. None of these six genes responded significantly to smoke treatment. Collectively, these differences suggest the possibility that iECs participate in the Contact Pathway (Kallikreins) and the Alternative Complement Pathway (CFD and CFP), whereas in primary ECs these pathways were transcriptionally suppressed. These observations suggest that HUVEC cells express proteins to protect them from complement and the contact/coagulation system, whereas iEC may be naïve due to lack of exposure to the human circulatory system. An experiment was performed to compare the cytotoxicity of smoke to HUVEC and iEC comparing non-heat treated vs. heat-treated calf serum to inactivate complement, however this did not show any difference in sensitivity to smoke (not shown). In summary, iECs were more sensitive to smoke than HUVECs, however complement did not seem to affect sensitivity to smoke in vitro.

3.10. Cytokine responses to smoke in iECs and HUVECs

Among 42 cytokines relevant to vascular endothelium, statistical analysis showed that 23 cytokines responded significantly to smoke in HUVECs or iECs. These 23 smoke-responsive cytokines included inflammatory cytokines: IFNa, TNFa, IL1a, IL1b, IL2, IL4, IL5, IL6, IL8, IL9, IL16, IL12(p70), IL13, IL15, IL16, IL17a, IL20, IL21 and PECAM1; anti-inflammatory cytokines: OPG, IL1RA, and TNFRII; chemokines: RANTES, MCP2, MIP1A, MIP1B, Eotaxin, GROa, and IP10; growth factors: SCF, LIF, VEGF-D, GMCSF, PDGF-BB, HGF, and BDNF; and clotting regulators: tPA and P-Selectin.

Cytokines that changed significantly in response to smoke treatment in the medium of HUVEC, iEC, or both, are shown in Figure 7. Among inflammatory cytokines many were increased by smoke in both HUVEC and iEC, including: IL12p70, IL1b, IFNg, RANTES, IL2, SCF, IL15, IL13, IL4, and IL16; as well as chemokines: MIP1a, and MCP2. Also increased by smoke in both HUVEC and iECs were anti-inflammatory cytokine IL1RA, and growth factor GMCSF. Thus, many of the 42 cytokines measured demonstrated a concerted increase reflecting a pro-inflammatory response to smoke, and most cytokine responses qualitatively coincided between HUVEC and iECs. Conversely, several cytokines were decreased significantly by smoke in both cell lines including IL1a, MIP1b, IL8, and IL9. Interestingly, IL6, HGF, PDGFBB, and anti-fibrotic factor tPA were decreased in the medium of HUVEC, but present at very low levels in iEC. Only IP10 was regulated divergently, increased by smoke in HUVEC but decreased by smoke in iEC, whereas BDNF and TNFRII were measurable only in HUVEC. TNFa, VEGFD, and TSLP did not change significantly in either cell line, whereas TSLP showed a trend toward an increase only in iECs. The differential production of IP10, BDNF, and TNFRII by smoke in HUVECs and iECs was surprising in light of the near-identical transcriptional responses in these two cell types. These differences in cytokine responses may reflect divergent translational or post-translational regulation. The cytokine responses by HUVECs and iECs was complex, including changes in 23 of 42 cytokines. Preliminary experiments show that cytokine responses are markedly dose-dependent; previous work shows that it is time-dependent as well.

Figure 7. Cytokines secreted by HUVECs and iECs in response to tobacco smoke.

Bar graphs show 29 cytokines in control conditions (white bars) and their responses to smoke (black bars) in HUVECs or iECs. Cytokines are grouped into three charts according to protein concentrations in the medium, below 50 pg/mL, 50–600 pg/mL, and above 600 pg/mL. An asterisk indicates a significant response to smoke p < 0.05.

Intriguingly, several inflammatory cytokines were suppressed by smoke, such as IL1a and IL8 in both HUVEC and iEC, and IL6 in HUVEC. Others have also noted suppression of inflammatory responses by smoke8, and attributed immunosuppression to acrolein and crotonaldehyde acting on human T-cells44, acrolein acting via the NRF2 and NFκB /RELA pathway on TH2 cells in mouse lung45, or nicotine acting on dendritic cells46. Perhaps the most compelling studies show NFκB/RELB-dependent suppression of inflammatory activity in mouse lung31. Future work should be done to clarify which smoke components stimulate and suppress inflammatory responses at high and low exposures to smoke, including clarification of whether the suppression of this sterile immune response by tobacco smoke components serves to worsen or improve outcomes.

4. Conclusions

We developed a protocol to efficiently differentiate human iPSCs into vascular ECs that produced a uniform and stable cobblestone morphology, near-complete staining with EC markers CDH5 and PECAM1, tube-formation, and Ac-LDL uptake, resembling primary ECs. Using RNAseq global gene expression analysis, these iECs generally resembled primary human ECs. Genes characteristically expressed by HAEC, HCAEC, or HUVEC were identified in Figure 3 and Table S2. Additional RNA sequencing analyses found that iECs and ECs reacted almost identically to smoke. By mapping groups of genes to transcription factors that likely regulate those genes, we identified eighteen TFs that governed responses to smoke in both primary ECs and iECs. These TFs include information about cell stress pathways invoked by smoke including oxidative stress (NRF2), ER stress (ATF3), heat shock (HSF1), DNA Damage (TP53), estrogenic response (ESR1) and inflammation (NFkB1, RELA, RELB). Gene responses by ECs and iECs were also informatically mapped to biological processes or pathways including UPR/ER stress, and regulation of the apoptotic balance.

Finally, EC responses to smoke were traced to secretion of 23 cytokines that regulate lymphocyte attachment and proliferation, coagulation and complement, and inflammation and fibrosis; EC-initiated events that collectively lead to atherosclerosis. Cytokines in the medium were similar between HUVEC and iECs, although several cytokines showed differences in expression, either baseline, or in response to tobacco smoke extract. Intriguingly, several inflammatory cytokines were suppressed by smoke, such as IL1a and IL8 in both HUVEC and iEC, and IL6 in HUVEC. In summary, these studies validate the iEC model and identify transcriptional response networks by which ECs respond to tobacco smoke. Our results systematically trace how ECs use these response networks to regulate genes and pathways, and to ultimately increase and suppress cytokine signals that initiate the diverse processes that lead to atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Samples for RNA sequencing

Table S2. Genes expressed selectively by primary endothelial cell beds

Table S3. Pathways enriched among genes expressed selectively by primary endothelial cell beds or iECs

Table S5. Pathways enriched among genes responsive to tobacco smoke

Table S4. Gene expression by endothelial cell types treated with vehicle or smoke

Acknowledgements

We thank the DNA Sequencing and Genomics core at NHLBI, NIH for supporting RNA library preparation and sequencing. We also thank the Flow Cytometry Core Facility at NHLBI, NIH for cytokine assays. The authors thank Dr. John Lambris, University of Pennsylvania, for guidance in complement experiments.

Funding Information

This study was funded by a grant to M.B. and D.G. from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Tobacco Products. This research was also supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, including the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and the National Toxicology Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

References

- (1).Hoffmann D, Djordjevic MV, and Hoffmann I. (1997) The changing cigarette. Prev Med 26, 427–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Alberg AJ, Shopland DR, and Cummings KM (2014) The 2014 Surgeon General’s report: commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the 1964 Report of the Advisory Committee to the US Surgeon General and updating the evidence on the health consequences of cigarette smoking. Am J Epidemiol 179, 403–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Backinger CL, Meissner HI, and Ashley DL (2016) The FDA “Deeming Rule” and Tobacco Regulatory Research. Tob Regul Sci 2, 290–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Messner B, and Bernhard D. (2014) Smoking and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction and early atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34, 509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Leone A. (2015) Toxics of Tobacco Smoke and Cardiovascular System: From Functional to Cellular Damage. Curr Pharm Des 21, 4370–4379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Csordas A, and Bernhard D. (2013) The biology behind the atherothrombotic effects of cigarette smoke. Nat Rev Cardiol 10, 219–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Mai J, Virtue A, Shen J, Wang H, and Yang XF (2013) An evolving new paradigm: endothelial cells--conditional innate immune cells. J Hematol Oncol 6, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Shiels MS, Katki HA, Freedman ND, Purdue MP, Wentzensen N, Trabert B, Kitahara CM, Furr M, Li Y, Kemp TJ, Goedert JJ, Chang CM, Engels EA, Caporaso NE, Pinto LA, Hildesheim A, and Chaturvedi AK (2014) Cigarette smoking and variations in systemic immune and inflammation markers. J Natl Cancer Inst 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Jin H, St Hilaire C, Huang Y, Yang D, Dmitrieva NI, Negro A, Schwartzbeck R, Liu Y, Yu Z, Walts A, Davaine JM, Lee DY, Donahue D, Hsu KS, Chen J, Cheng T, Gahl W, Chen G, and Boehm M. (2016) Increased activity of TNAP compensates for reduced adenosine production and promotes ectopic calcification in the genetic disease ACDC. Sci Signal 9, ra121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Lamb J, Crawford ED, Peck D, Modell JW, Blat IC, Wrobel MJ, Lerner J, Brunet JP, Subramanian A, Ross KN, Reich M, Hieronymus H, Wei G, Armstrong SA, Haggarty SJ, Clemons PA, Wei R, Carr SA, Lander ES, and Golub TR (2006) The Connectivity Map: using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science 313, 1929–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez JY, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, and Cardona A. (2012) Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9, 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Mao Q, Huang X, He J, Liang W, Peng Y, Su J, Huang Y, Hu Z, Lu X, and Zhao Y. (2016) A novel method for endothelial cell isolation. Oncol Rep 35, 1652–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Bodnar JA, Morgan WT, Murphy PA, and Ogden MW (2012) Mainstream smoke chemistry analysis of samples from the 2009 US cigarette market. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 64, 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y, Duan Q, Wang Z, Meirelles GV, Clark NR, and Ma’ayan A. (2013) Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics 14, 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, Fernandez NF, Duan Q, Wang Z, Koplev S, Jenkins SL, Jagodnik KM, Lachmann A, McDermott MG, Monteiro CD, Gundersen GW, and Ma’ayan A. (2016) Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res 44, W90–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Toshner M, Dunmore BJ, McKinney EF, Southwood M, Caruso P, Upton PD, Waters JP, Ormiston ML, Skepper JN, Nash G, Rana AA, and Morrell NW (2014) Transcript analysis reveals a specific HOX signature associated with positional identity of human endothelial cells. PLoS One 9, e91334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ho M, Yang E, Matcuk G, Deng D, Sampas N, Tsalenko A, Tabibiazar R, Zhang Y, Chen M, Talbi S, Ho YD, Wang J, Tsao PS, Ben-Dor A, Yakhini Z, Bruhn L, and Quertermous T. (2003) Identification of endothelial cell genes by combined database mining and microarray analysis. Physiol Genomics 13, 249–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Nolan DJ, Ginsberg M, Israely E, Palikuqi B, Poulos MG, James D, Ding BS, Schachterle W, Liu Y, Rosenwaks Z, Butler JM, Xiang J, Rafii A, Shido K, Rabbany SY, Elemento O, and Rafii S. (2013) Molecular signatures of tissue-specific microvascular endothelial cell heterogeneity in organ maintenance and regeneration. Dev Cell 26, 204–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).dela Paz NG, and D’Amore PA (2009) Arterial versus venous endothelial cells. Cell Tissue Res 335, 5–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hahn C, and Schwartz MA (2009) Mechanotransduction in vascular physiology and atherogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10, 53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Jacob S, Laury-Kleintop L, and Lanza-Jacoby S. (2008) The select cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib reduced the extent of atherosclerosis in apo E−/− mice. J Surg Res 146, 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Tang SY, Monslow J, Todd L, Lawson J, Pure E, and FitzGerald GA (2014) Cyclooxygenase-2 in endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells restrains atherogenesis in hyperlipidemic mice. Circulation 129, 1761–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Gene Ontology C. (2015) Gene Ontology Consortium: going forward. Nucleic Acids Res 43, D1049–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Roth A, Santos A, Tsafou KP, Kuhn M, Bork P, Jensen LJ, and von Mering C. (2015) STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res 43, D447–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Kamiya M, Toriba A, Onoda Y, Kizu R, and Hayakawa K. (2005) Evaluation of estrogenic activities of hydroxylated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in cigarette smoke condensate. Food Chem Toxicol 43, 1017–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Satta S, Mahmoud AM, Wilkinson FL, Yvonne Alexander M, and White SJ (2017) The Role of Nrf2 in Cardiovascular Function and Disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 9237263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Naik P, Sajja RK, Prasad S, and Cucullo L. (2015) Effect of full flavor and denicotinized cigarettes exposure on the brain microvascular endothelium: a microarray-based gene expression study using a human immortalized BBB endothelial cell line. BMC Neurosci 16, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Teasdale JE, Hazell GG, Peachey AM, Sala-Newby GB, Hindmarch CC, McKay TR, Bond M, Newby AC, and White SJ (2017) Cigarette smoke extract profoundly suppresses TNFalpha-mediated proinflammatory gene expression through upregulation of ATF3 in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Sci Rep 7, 39945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Gilchrist M, Thorsson V, Li B, Rust AG, Korb M, Roach JC, Kennedy K, Hai T, Bolouri H, and Aderem A. (2006) Systems biology approaches identify ATF3 as a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor 4. Nature 441, 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).McMillan DH, Baglole CJ, Thatcher TH, Maggirwar S, Sime PJ, and Phipps RP (2011) Lung-targeted overexpression of the NF-kappaB member RelB inhibits cigarette smoke-induced inflammation. Am J Pathol 179, 125–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Labonte L, Coulombe P, Zago M, Bourbeau J, and Baglole CJ (2014) Alterations in the expression of the NF-kappaB family member RelB as a novel marker of cardiovascular outcomes during acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One 9, e112965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Korashy HM, and El-Kadi AO (2006) The role of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases. Drug Metab Rev 38, 411–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Rollins DA, Coppo M, and Rogatsky I. (2015) Minireview: nuclear receptor coregulators of the p160 family: insights into inflammation and metabolism. Mol Endocrinol 29, 502–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Motallebipour M, Ameur A, Reddy Bysani MS, Patra K, Wallerman O, Mangion J, Barker MA, McKernan KJ, Komorowski J, and Wadelius C. (2009) Differential binding and co-binding pattern of FOXA1 and FOXA3 and their relation to H3K4me3 in HepG2 cells revealed by ChIP-seq. Genome Biol 10, R129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Pan F, Yang TL, Chen XD, Chen Y, Gao G, Liu YZ, Pei YF, Sha BY, Jiang Y, Xu C, Recker RR, and Deng HW (2010) Impact of female cigarette smoking on circulating B cells in vivo: the suppressed ICOSLG, TCF3, and VCAM1 gene functional network may inhibit normal cell function. Immunogenetics 62, 237–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Podust LM, Krezel AM, and Kim Y. (2001) Crystal structure of the CCAAT box/enhancer-binding protein beta activating transcription factor-4 basic leucine zipper heterodimer in the absence of DNA. J Biol Chem 276, 505–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Tsukada J, Yoshida Y, Kominato Y, and Auron PE (2011) The CCAAT/enhancer (C/EBP) family of basic-leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors is a multifaceted highly-regulated system for gene regulation. Cytokine 54, 6–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Cui J, Yang Y, Zhang C, Hu P, Kan W, Bai X, Liu X, and Song H. (2011) FBI-1 functions as a novel AR co-repressor in prostate cancer cells. Cell Mol Life Sci 68, 1091–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Pastore A, and Piemonte F. (2012) S-Glutathionylation signaling in cell biology: progress and prospects. Eur J Pharm Sci 46, 279–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Huang Q, Zhan L, Cao H, Li J, Lyu Y, Guo X, Zhang J, Ji L, Ren T, An J, Liu B, Nie Y, and Xing J. (2016) Increased mitochondrial fission promotes autophagy and hepatocellular carcinoma cell survival through the ROS-modulated coordinated regulation of the NFKB and TP53 pathways. Autophagy 12, 999–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Prodromou C. (2017) Regulatory Mechanisms of Hsp90. Biochem Mol Biol J 3, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Won S, Sayeed I, Peterson BL, Wali B, Kahn JS, and Stein DG (2015) Vitamin D prevents hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced blood-brain barrier disruption via vitamin D receptor-mediated NF-kB signaling pathways. PLoS One 10, e0122821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Mantovani A. (2010) Molecular pathways linking inflammation and cancer. Curr Mol Med 10, 369–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Lambert C, McCue J, Portas M, Ouyang Y, Li J, Rosano TG, Lazis A, and Freed BM (2005) Acrolein in cigarette smoke inhibits T-cell responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol 116, 916–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Spiess PC, Kasahara D, Habibovic A, Hristova M, Randall MJ, Poynter ME, and van der Vliet A. (2013) Acrolein exposure suppresses antigen-induced pulmonary inflammation. Respir Res 14, 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Alkhattabi N, Todd I, Negm O, Tighe PJ, and Fairclough LC (2018) Tobacco smoke and nicotine suppress expression of activating signaling molecules in human dendritic cells. Toxicol Lett 299, 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Samples for RNA sequencing

Table S2. Genes expressed selectively by primary endothelial cell beds

Table S3. Pathways enriched among genes expressed selectively by primary endothelial cell beds or iECs

Table S5. Pathways enriched among genes responsive to tobacco smoke

Table S4. Gene expression by endothelial cell types treated with vehicle or smoke