Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Esophageal cancer ranks eighth among the most prevalent cancers globally and is the sixth leading cause of mortality from malignancy worldwide; it is the 7th most prevalent malignancy in males and the 6th most prevalent malignancy in females. In Pakistan, the incidence is 4.1 per 100 000 with the province of Baluchistan having the greatest incidence.

OBJECTIVE:

Report trends and characteristics of esophageal cancer in Pakistan over the past 10 years.

DESIGN:

Cross-sectional, retrospective review of medical records.

SETTING:

Tertiary care hospital.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

The study included all patients admitted with a diagnosis of esophageal carcinoma with a mass lesion or luminal narrowing. The records were for the period from January 2011 to September 2020.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES:

Gender, histopathological types/differentiation along with clinical/laboratory findings.

SAMPLE SIZE:

1009 with a mean (standard deviation) age of 49.3 (14.2) and a median (interquartile range of 50 (22) years (443 males and 566 females with age of 51.0 [20] years and 47.9 [23.8] years, respectively). The male-to-female ratio was 1:1.2.

RESULTS:

Most patients (82.7%) had squamous cell carcinomas with a male-to-female ratio of 1:2; the remainder had adenocarcinomas with a male-to-female ratio of 4:1 (P<.001). Dysphagia, weight loss, and vomiting were the most prevalent symptoms. More adenocarcinoma masses were located distally compared with squamous cell carcinomas (P=.030), lesions were most likely to be ulcerated (P=.910). Luminal narrowing was slightly more frequent in squamous cell carcinoma (P=.215), thickening was more prominently circumferential in the adenocarcinomas. In squamous cell carcinoma, the most common variant was moderately differentiated while moderate to poorly differentiated variants were more common in adenocarcinoma. In the survival analysis, squamous cell carcinoma (P=.014 vs adenocarcinoma), particularly the well-differentiated type (P=.018 vs other variants), projected a better prognosis.

CONCLUSION:

Our study reports the most recent trends of esophageal carcinoma in this region.

LIMITATIONS:

Lack of metastatic workup, TNM staging, and mode of treatment, along with the overlapping pattern of histological variants.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST:

None.

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal cancer is the eighth most prevalent cancer globally and the sixth leading cause of mortality from malignancy worldwide.1–3 Esophageal cancer is solely responsible for 7% of gastrointestinal cancers.4 In 2012-2013, 442 000 to 455 800 cases were reported worldwide along with a mortality of 400 200 to 440 000 inhabitants.3,5,6 Esophageal carcinoma is reported as the 7th most prevalent malignancy in males while regarded as the 6th most prevalent malignancy in females.7 The maximum frequencies of esophageal cancer have been reported in China, northeastern Iran, the southeast of the United States, and South Africa.1 Esophageal carcinoma is categorized histologically into two variants, namely adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Adenocarcinoma is prevalent in highly developed regions of the globe, like North America and Europe. Barrett's esophagus, obesity, and chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease are prime causative factors, while the common site of occurrence is the distal esophagus. A common site of occurrence of squamous cell carcinoma is the upper and middle esophagus. Squamous cell carcinoma has an increased incidence in regions of Asia like northern China, Iran, Turkmenistan, northern Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Mongolia, collectively termed as “the esophageal Asian cancer belt” with 100 cases per 100 000 population in underdeveloped countries.1,2,6–8

Esophageal carcinoma primarily involves the elderly population ranging from 40–60 years.4 The mean age of patients suffering from esophageal cancer in Asia is in the range of 51–60 years.9–15 The age-standardized rate (ASR) for cases of esophageal carcinoma worldwide is reported as 7.7 per 100 000 cases for Asia with the maximum ASR of 12.5–12.7 per 100 000 cases in Bangladesh and China, while the ASR reported for Pakistan is 4.1 per 100 000 cases.1,3 Esophageal carcinoma has a predilection towards males, affecting males 2-4 times more frequently as compared to females worldwide.4 Etiological factors predisposing to esophageal cancer are multiple and differ according to subtypes. Barrett's esophagus, obesity, and chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease are the most prevalent etiological factors for esophageal adenocarcinoma in Western populations (United Kingdom, United States, Australia, and France). On the other hand, smoking, consumption of alcohol, opium, hot beverages, a diet with excessive salt or lacking salt, a nutritionally deficient diet, low socioeconomic lifestyles, betel nut chewing, viral agents (e.g., human papillomavirus), and a family history of cancer are factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in the Asian esophageal cancer belt.1,3,16,17 Low socioeconomic lifestyle and consumption of impure water are prominent risk factors in regions of China and Saudi Arabia, while Iran reported low socioeconomic lifestyle as the prominent risk factor.2,5,8,10 Risk factors predisposing inhabitants of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan are smoking, consumption of excessive alcohol, opium, and hot beverages while betel nut chewing, nutritional deficiency of fruits, vegetables and fat-soluble vitamins like vitamin A are also contributing factors in Saudi Arabia along with a diet of excessive salt.2,4,7–10,12,13,15,18

Dysphagia is one of the most prominent clinical manifestations of esophageal carcinoma suffered by individuals in China, Iran, India Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan with weight loss being the second common manifestation, which is reported more often in studies from Saudi Arabia while other symptoms are odynophagia, hoarseness, retrosternal burning pain, anemia and blood in the vomitus.7,10,11,13,15,19 Modalities used in the detection of esophageal carcinoma are computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, double-contrast barium enema, fiberoptic endoscopy, chromoendoscopy, endoscopic ultrasound, endoscopy with Iodine, high-resolution magnification endoscopy, narrow-band imaging, and positron emission tomography.2,10–15

Staging criteria for determining advancement of esophageal cancer is the TNM staging approved by American Joint Committee on Cancer and treatment is based staging. T1 and T2 levels undergo surgical re-section, which include trans-hiatal esophagectomy and transthoracic esophagogastrostomy while patients with T3 and T4 stages are treated with a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy.19,20 The worldwide 5-year survival rate for esophageal carcinoma is reported as only 10% to 18%.1,3,16 China reported a 5-year survival rate lower than 10%, Bangladesh 13%, India 15%, Iran less than 10% while the rate in Pakistan is reported as 6%.2,7,15,21,22

The objective of this study was to demonstrate current trends and characteristics of esophageal cancer over the past 10 years, using data from a tertiary care hospital in Sindh province, which receives patients from almost all over Pakistan. There is scarce recent data on esophageal carcinoma in this population, hence we aimed to fill the gap and also compare the characteristics of current trends with reported data for this population, as well as with those of other regional studies.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study was conducted at the Department of Gastroenterology of Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Center, Karachi, Pakistan, which is a 1650-bed tertiary care hospital, receiving patients from all over the country. Ethical approval was waived by the institutional ethical review committee. We reviewed the medical records of all patients admitted to our hospital from 1st January 2011 to 30th September 2020, with a diagnosis of esophageal carcinoma having a mass lesion or luminal narrowing. Those patients who did not present with an esophageal mass, or were diagnosed with an in situ carcinoma on histopathology, or had any other malignancies were excluded. For patients who met the inclusion criteria, complete medical and diagnostic evaluations were documented through a well-designed proforma, comprising demographic data, clinical records, biochemical parameters, diagnostic modalities, and histopathological patterns. Data on the frequency of carcinoma and types of carcinoma were collected and compared. P values <.05 were deemed significant (two-tailed). Non-parametric tests were used for quantitative variables due to non-uniform distribution as determined by Shapiro-Wilk test, while the Fisher exact test and chi-square test were used for qualitative variables. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

The male-to-female ratio was 1:1.2 for the 1009 individuals included in the study (Table 1). The majority of the study population was from rural Sindh province, with most individuals involved in low socioeconomic occupations like laborers, farmers, and housewives (reflecting the female dominance). The majority of patients had no comorbidities, while one-half denied having any addictions. The most frequent addictions were betel nuts/leaf in 219 patients (21.7%), cigarette/hookah smoking in 173 (17.2%), followed by naswar and gutka in 172 (17.0%), while alcoholism was recorded in only 5 patients (0.5%). The most prevalent histotype was squamous cell carcinoma with a ratio of 4:1 compared to adenocarcinoma. The prominent clinical feature among the study population was dysphagia, presenting in one-third of the patients; 54.5% had dysphagia for both solids and liquids simultaneously, 28.1% developed dysphagia first to solids and then progressed to liquids, 12.6% had dysphagia only for solids and 4.8% had dysphagia only for liquids (Table 2). Retrosternal burning was associated with adenocarcinoma (P=.008), odynophagia with squamous cell carcinoma (P=.002), acid reflux with squamous cell carcinoma (P value=.022), while the rest of the signs and symptoms were equally distributed among the two types of esophageal carcinoma. The majority of biochemical markers did not differ by the type of carcinoma except for hemoglobin (P=.003), platelet counts (P=.001) and total bilirubin (P=.005) (Table 3).

Table 1.

Demographic data (n=1009).

| Variable | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 443 (43.9) |

| Female | 566 (56.1) |

| Residence | |

| Sindh | 849 (84.1) |

| Balochistan | 62 (6.1) |

| Punjab | 18 (1.8) |

| Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | 43 (4.3) |

| Gilgit Baltistan | 18 (1.8) |

| Afghanistan migrants | 16 (1.6) |

| Others | 3 (.3) |

| Language | |

| Sindhi | 434 (43.0) |

| Balochi | 90 (8.9) |

| Punjabi | 55 (5.5) |

| Balti | 12 (1.2) |

| Pashtoon | 108 (10.7) |

| Urdu | 259 (25.7) |

| Others | 51 (5.1) |

| Occupation | |

| Housewife | 560 (55.5) |

| Labor | 208 (20.6) |

| Farmer | 74 (7.3) |

| Government employee | 18 (1.8) |

| Private business | 58 (5.8) |

| Shopkeeper | 14 (1.4) |

| Retired | 28 (2.8) |

| Others | 49 (4.9) |

| Comorbidities | |

| None | 834 (82.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 53 (5.3) |

| Hypertension | 88 (8.7) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 31 (3.1) |

| Tuberculosis | 5 (.5) |

| Hepatitis B | 9 (.9) |

| Hepatitis C | 26 (2.6) |

| Others | 18 (1.8) |

| Addictions | |

| None | 471 (46.7) |

| Smoking (tobacco cigarettes) | 150 (14.9) |

| Hookah (smoking) | 23 (2.3) |

| Betel leaf | 128 (12.7) |

| Betel nuts | 91 (9.0) |

| Betel quid (gutka) | 90 (8.9) |

| Naswar (dipping tobacco) | 82 (8.1) |

| Alcohol | 5 (.5) |

| Other illicit drugs | 5 (.5) |

| Histopathology | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 834 (82.7) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 175 (17.3) |

Data are number (%).

Table 2.

Frequency of symptomatology among the histopathological variants (n=1009).

| Clinical features | Squamous cell carcinoma (n=834) | Adenocarcinoma (n=175) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fever: n=25 (2.5%) | 19 (2.3%) | 6 (3.4%) | .419b |

| Weight loss: n=196 (19.4%) | 164 (19.7%) | 32 (18.3%) | .675a |

| Upper GI bleeding: n=47 (4.7%) | 41 (4.9%) | 6 (3.4%) | .396b |

| Retrosternal burning: n=60 (5.9%) | 42 (5.0%) | 18 (10.3%) | .008a |

| Acid reflux: n=22 (2.2%) | 22 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | .022b |

| Dysphagia: n=327 (32.4%) | 260 (31.2%) | 67 (38.3%) | .068a |

| Both solids/liquids: n=178 (17.6%) | 151 (18.1%) | 27 (15.4%) | |

| Only solids: n=41 (4.0%) | 33 (3.9%) | 8 (4.6%) | |

| Only liquids: n=16 (1.6%) | 12 (1.4%) | 4 (2.3%) | .217a |

| First solids then progressed to liquids: n=92 (9.1%) | 73 (8.7%) | 19 (10.8%) | |

| Odynophagia: n=45 (4.5%) | 45 (5.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | .002a |

| Anorexia: n=4 (0.4%) | 2 (0.2%) | 2 (1.1%) | .141b |

| Regurgitation of food: n=15 (1.5%) | 11 (1.3%) | 4 (2.3%) | .310b |

| Nocturnal cough: n=33 (3.3%) | 30 (3.6%) | 3 (1.7%) | .203a |

| Vomiting: n=230 (22.8%) | 189 (22.7%) | 41 (23.5%) | .826a |

| Projectile: (n=188) 18.6% | 155 (18.6%) | 33 (18.9%) | .933a |

| Non-projectile: (n=42) 4.2% | 34 (4.1%) | 8 (4.6%) | .766a |

| Dyspnea: n=2 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.6%) | .317b |

| Neck swelling: n=1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1.000b |

| Halitosis: n=1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1.000b |

| No symptoms: n=46 (4.6%) | 43 (5.2%) | 3 (1.7%) | .047a |

Indicates Fisher's exact test to compute the P value.

Indicates the chi-square test used to compute the P value.

Table 3.

Comparison of biochemical markers among the variants of esophageal carcinoma.

| Laboratory investigations | All patients (n=1009) | Squamous cell carcinoma (n=834) | Adenocarcinoma (n=175) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.0 (10.0–12.0) | 11.0 (10.0–12.0) | 12.0 (10.0–12.3) | .003 |

| Mean corpuscular volume (fL) | 80.0 (76.0–88.0) | 80.0 (76.0–88.0) | 82.0 (76.0–88.0) | .091 |

| Platelets (109 cells/liter) | 233.0 (187.0–302.0) | 237.0 (190.75–312.0) | 209.0 (167.0–267.0) | .001 |

| Total leucocyte count (109 cells/liter) | 6.3 (5.0–8.8) | 6.3 (5.0–9.0) | 6.3 (4.7–7.3) | .078 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 136.0 (133.0–141.0) | 136.0 (133.0–141.0) | 136.0 (134.0–141.0) | .175 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.0 (3.50–4.55) | 4.0 (3.5–4.5) | 4.0 (3.2–4.6) | .870 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 100.0 (98.0–102.0) | 100.0 (98.0–102.0) | 100.0 (98.0–102.0) | .143 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.45 (0.23–0.65) | 0.50 (0.30–0.66) | 0.43 (0.23–0.55) | .005 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.22 (0.12–0.40) | 0.21 (0.12–0.44) | 0.22 (0.12–0.36) | .333 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 19.0 (16.0–29.0) | 19.0 (15.75–29.0) | 20.0 (16.0–27.0) | .747 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 22.0 (16.0–28.0) | 22.0 (16.0–28.0) | 21.0 (15.0–29.0) | .844 |

| Gamma glutamyl transferase (IU/L) | 25.0 (18.0–41.0) | 25.0 (18.0–40.0) | 29.0 (19.0–44.0) | .089 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 208.0 (156.0–255.5) | 207.0 (157.0–255.0) | 222.0 (127.0–265.0) | .219 |

Data are median (25th-75th percentile) except for mean (SD) corpuscular volume. P value calculated by Mann-Whitney U test.

The male-to-female ratio between patients diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma was 1:2, while for adenocarcinoma, the male-to-female ratio was 4:1 (P<.001) (Table 4). The median (IQR) age of the study population was 50.0 (22) years with patients of adeno-carcinoma slightly older than patients with squamous cell carcinoma (P<.001). Females were younger with a median age of 47.9 years when compared to males with a median age of 51.0 years (P<.001). The most frequent site of masses was in the distal part of the esophagus for both types of carcinoma, with adenocarcinoma more often presenting as a distal mass (P=.030) and the squamous cell carcinoma more often presenting proximally (P<.001) as well as in the middle esophagus (P=.061). The most characteristic type of mass lesion in both types of carcinoma was ulcerated, followed by circumferential, irregular, stricture, fungating, polypoidal, with nodular being the least common. Luminal narrowing was a slightly more common feature of squamous cell carcinoma as compared to adenocarcinoma (P=.215).

Table 4.

Clinical data by histotype of esophageal carcinoma.

| Characteristics | All patients (n=1009) | Squamous cell carcinoma (n=834) | Adenocarcinoma (n=175) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age | 50.0 (38.0–60.0) | 48.5 (36.0–60.0) | 55.0 (45.0–62.0) | <.001a |

| Males (n=443) | 50.0 (42.0–62.0) | 50.0 (39.5–60.0) | 56.0 (46.0–62.0) | <.001a |

| Females (n=566) | 48.0 (35.0–59.0) | 46.0 (36.0–59.0) | 51.0 (35.0–60.0) | <.001a |

| Histopathology | ||||

| Males | 443 (43.90%) | 306 (36.69%) | 137 (78.28%) | <.001b |

| Females | 566 (56.09) | 528 (63.30%) | 38 (21.71%) | |

| The extent of mass on EGD | ||||

| Proximal | 151 (15.0%) | 140 (16.8%) | 11 (6.3%) | <.001b |

| Middle | 246 (24.4%) | 213 (25.5%) | 33 (18.9%) | .061b |

| Distal | 366 (36.3%) | 290 (34.8%) | 76 (43.4%) | .030b |

| Proximal to middle | 48 (4.8%) | 40 (4.8%) | 8 (4.6%) | .899b |

| Proximal to distal | 12 (1.2%) | 11 (1.3%) | 1 (0.6%) | .703c |

| Middle to distal | 163 (16.2%) | 124 (14.9%) | 39 (22.3%) | .015b |

| From GEJ, extending into fundus | 4 (0.4%) | 1 (0.1%) | 3 (1.7%) | .018c |

| Unidentified | 19 (1.9%) | – | ||

| Characteristic of mass on EGD | ||||

| Ulcerated | 325 (32.2%) | 268 (32.1%) | 57 (32.6%) | .910b |

| Circumferential | 258 (25.6%) | 212 (25.4%) | 46 (26.3%) | .811b |

| Ulcerated circumferential | 72 (7.1%) | 50 (6.0%) | 22 (12.6%) | .002b |

| Nodular | 42 (4.2%) | 31 (3.7%) | 11 (6.3%) | .122b |

| Irregular | 123 (12.2%) | 112 (13.4%) | 11 (6.3%) | .009b |

| Polypoidal | 46 (4.6%) | 42 (5.0%) | 4 (2.3%) | .113b |

| Fungating | 57 (5.6%) | 43 (5.2%) | 14 (8.0%) | .138b |

| Stricture | 59 (5.8%) | 52 (6.2%) | 7 (4.0%) | .252b |

| Nodular and fungating | 7 (0.7%) | 7 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | .612c |

| Unidentified | 20 (2.0%) | – | ||

| Luminal narrowing on EGD | ||||

| Present | 801 (79.4%) | 670 (80.3%) | 131 (74.9%) | .215c |

| Absent | 188 (18.6%) | 148 (17.7%) | 40 (22.9%) | |

| Unidentified | 20 (2.0%) | – | ||

Indicates Mann-Whitney U test used to compute the P value.

Indicates chi-square test to compute the P value.

Indicates Fisher's exact test to compute the p-value.

For radiological findings, Involvement was more frequently distal for both types of carcinomas, but adenocarcinomas were usually identified in the lower region (P=.008), while squamous cell carcinomas were in the middle (P<.001) as well as in the upper esophagus (P=.001) (Table 5). The characteristic thickness of mass on CT scan was seemingly circumferential, followed by the mural, eccentric, and diffuse thickness (least likely).

Table 5.

Radiological findings (n=1009).

| Characteristics | Squamous cell carcinoma (n=834) | Adenocarcinoma (n=175) | P value | All patients (n=1009) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involvement of region on CT scan | ||||

| Upper | 143 (17.1) | 13 (7.4) | .001a | 156 (15.5) |

| Middle | 207 (24.8) | 20 (11.4) | <.001a | 227 (22.5) |

| Lower | 288 (34.5) | 79 (45.1) | .008a | 367 (36.4) |

| Upper mid | 53 (6.4) | 15 (8.6) | .288a | 68 (6.7) |

| Upper lower | 8 (1.0) | 5 (2.9) | .058b | 13 (1.3) |

| Mid lower | 122 (14.6) | 39 (22.3) | .120a | 161 (16.0) |

| Unidentified | – | 17 (1.7) | ||

| Characteristic thickening of mass on CT scan | ||||

| Circumferential | 331 (39.7) | 100 (57.1) | <.001a | 431 (42.7) |

| Mural | 103 (12.4) | 16 (9.1) | .232a | 119 (11.8) |

| Both circumferential and mural | 317 (38.0) | 41 (23.4) | <.001a | 358 (35.5) |

| Eccentric | 60 (7.2) | 11 (6.3) | .669a | 71 (7.0) |

| Diffuse | 7 (0.8) | 2 (1.1) | .659b | 9 (0.9) |

| Unidentified | – | 21 (2.1) | ||

Data are number (%)

Chi-square test,

Fisher exact test

Adenocarcinomas were plausibly circumferential in our study population (P<.001) with squamous cell carcinomas potentially having both circumferential and mural thickening (P<.001). The histopathological variants of squamous cell carcinomas were moderately differentiated in 559 patients (67.0%), either keratinized/nonkeratinized/infiltrating or unidentified, followed by well-differentiated in 121 (14.5%) and poorly differentiated in 83 (9.9%) (Table 6). Dysplasia of squamous cells was present in 7 patients (0.8%) while high-grade sarcoma was present in 4 patients (0.5%) and was the least common variant. Among the adenocarcinomas, poorly differentiated variants were most prevalent followed by moderately differentiated and well-differentiated carcinomas, either keratinized/non-keratinized/infiltrating/or unidentified. Small cell carcinoma was present in 2 patients (1.1%), being the least common variant.

Table 6.

Histopathological variants (n=1009).

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma (n=834) | Adenocarcinoma (n=175) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variant | Frequency | Variant | Frequency |

| Poorly differentiated SQC | 52 (6.2) | Poorly differentiated ADC | 41 (23.4) |

| Moderately differentiated SQC | 375 (45.0) | Moderately differentiated ADC | 38 (21.7) |

| Well differentiated SQC | 89 (10.7) | Well differentiated ADC | 27 (15.4) |

| Poorly differentiated and keratinized SQC | 6 (0.7) | Moderate to poorly differentiated ADC | 40 (22.8) |

| Moderately differentiated and keratinized SQC | 117 (14.0) | Moderate to well differentiated ADC | 8 (4.6) |

Data are number (%). SQC: Squamous cell carcinoma, ADC: Adenocarcinoma

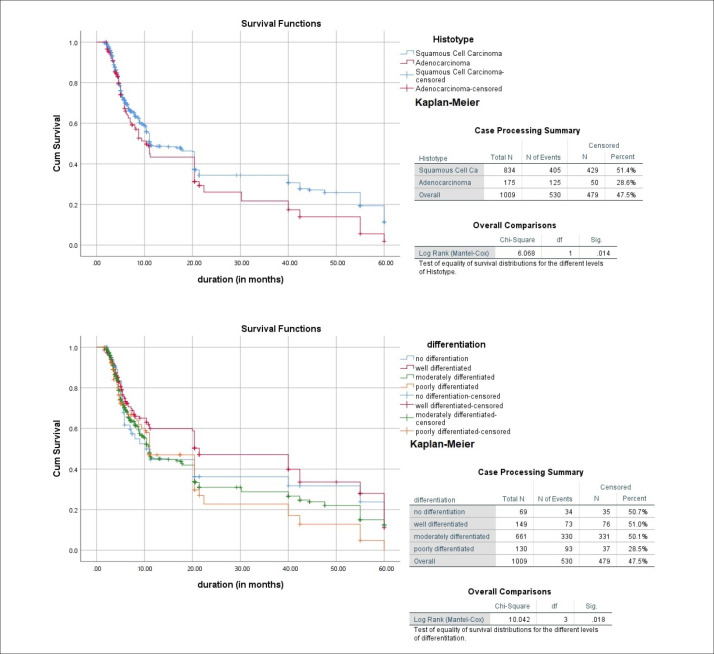

The 5-year survival data for the tumor behavior with respect to histotype and mode of differentiation are presented as Kaplan-Meier curves, which show that squamous cell carcinoma (P=.014), and particularly the well-differentiated type (P=.018), having better prognosis compared to others, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for histotype and differentiation of esophageal carcinoma.

DISCUSSION

Overall, squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus accounts for 90% of cases of the total tumor burden worldwide.23 Although both varieties of carcinomas have distinct etiologies, geographic trends, patterns, and risk factors, the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma is slightly greater in elderly postmenopausal women.23 In Pakistan, the province of Baluchistan reported the greatest number of cases of esophageal carcinoma.7,24 Squamous cell carcinoma is dominant within inhabitants of Pakistan while cases of adenocarcinoma are less prevalent.14 Esophageal carcinoma has gender affinity towards males as compared to females as reported by several research studies conducted worldwide, but in our study female gender had a slight dominance over males with a ratio of 1.2:1. A unique finding of our study was that squamous cell carcinoma occurred more within females in contrast to the findings of several other studies, while esophageal adenocarcinoma was suffered predominantly by males.14 Low socioeconomic status prevailed within the sample size evaluated in our study as the majority of inhabitants were farmers, laborers, and housewives, as reported in some other studies.2,10 Smoking was a widely prominent addiction within sufferers of esophageal carcinoma; betel leaf (paan), betel nut, betel quid were second, third, and fourth common addictive factors, respectively, while alcohol was least prevalent, which is consistent with several studies.4,7,8,12–15,17,18 Squamous cell carcinoma was the most common histologically variant within our study population while adenocarcinoma of the esophagus was encountered less frequently in our findings, corresponding with studies conducted in regions belonging to the Asian cancer belt. As squamous cell carcinoma is frequently encountered in Pakistan, the site of the esophagus was commonly involved was the lower end in our study population contrasting with numerous studies reporting the middle esophagus as commonly involved.4,7,8,14,17,18 For adenocarcinoma, the highest frequency in the lower esophagus paralleled with the findings of several other studies.4,7,8,14,17,18 Clinical manifestations frequently suffered by patients included in our study were dysphagia, followed by weight loss and vomiting, which was synchronous with multiple studies,2,4,7,8,12–15,17,18 while an orexia and halitosis were least suffered.

Biopsy findings within the sample size evaluated in our study indicated that moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma was frequently detected, consistent with the findings of Ali et al24 while contrasting with the findings of Hafeez et al.14 Poorly differentiated carcinoma was the least detected for squamous cell carcinoma. In the case of esophageal adenocarcinoma, the biopsy finding most frequently encountered in our study was poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma contravening few studies,25 followed by moderate to poorly differentiated types, while the least encountered finding was well-differentiated adenocarcinoma.

The mean age in our study was similar to a study conducted in Afghanistan in 2014,15 documenting a mean age of 47.3 (17.8) with an age range of 17–88 years, while our study found a mean age of 49.3 (14.2) with an age range of 15–92 years. The previous data available for Karachi reported a mean age of 53.3–55.8 years in males and 53.3–54.3 years in females,18 which was slightly higher as compared to our study. The male-to-female ratio was 1.4:1 in the same study, while the ratio in our study was 1:1.2 with a female predominance. However, a gender disparity was observed in adenocarcinoma, with a male predominant ratio of 4:1, similar to other studies,26 while squamous cell carcinoma was reported with a female predominance of 2:1 in our study, contrasting other studies showing a male predominance.14 A study conducted in Karachi in 2010,27 found a 60% occurrence of esophageal carcinoma in males, unlike our data. The histopathological pattern of adenocarcinoma was exactly opposite to the study conducted in Punjab in 2019,14 displaying well-differentiated carcinoma as more frequent than the moderate and poorly differentiated, while our study reported an increased prevalence of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, followed by moderately differentiated and well-differentiated carcinomas. Our finding was also dissimilar to another study conducted at Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital, Lahore in 2015.25 Similarly, squamous cell carcinomas had moderately differentiated variants as the most common histopathological finding in correlation with other studies,24,25 while differing from the results of a few other studies that reported well-differentiated more frequently than moderately differentiated carcinoma.14

Comparing our results with regional data, a study conducted in Bangladesh quoted the same risk factors mentioned in our study,27 with smoking, betel nut/leaf, tobacco chewing, and alcohol ranking the list in that order. Dysphagia and weight loss were the most predominant symptoms among the Bangladesh population suffering from esophageal carcinoma,12 followed by vomiting—another common symptom in our study. Another study conducted in northwest Pakistan was consistent with our outcomes for gender and age distribution for both types of esophageal carcinomas.28 That study also reported a predominately clinical presentation and endoscopic findings parallel to our study. Further, a study in Uganda reported a middle-third involvement of most of the esophageal carcinomas in their population, contrasting with our study involving the lower-third usually in both types of esophageal carcinomas.29 A comparative analysis among the Afghanistan population and Pakistan, conducted in 2018,30 indicated that the Afghan population was more prone to squamous cell carcinoma as compared to adenocarcinoma. The same study also showed that Afghani patients were younger compared to Pakistan. In our study, only 16 Afghan migrants were included, among which 10 suffered from adenocarcinoma and the six remaining were diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma. The mean age of 57 years was greater than other study participants, but these findings probably do not reflect the Asian belt of esophageal carcinomas. Both types of cancers were more prevalent in the lower third of the esophagus, similar to the study discussed earlier.30

Previously, survival data and prognostics factors for esophageal carcinoma in Pakistan were studied in 2003 with a favorable prognosis observed with squamous cell carcinoma, while other factors such as luminal narrowing and thrombocytopenia were among bad prognostic markers.31 With respect to tumor differentiation, a study in Iran demonstrated moderately differentiated carcinomas having better survival than well-differentiated and poorly differentiated tumors.32 In contrast, our results suggested that well-differentiated tumors and the squamous cell variety had better survival than others. The latter outcome was similar to that in the Iranian study, along with the location of the tumor (lower one-third). Increased age was another factor associated with decreased survival.32 Another study conducted in Brazil showed no difference between squamous cell carcinoma and esophageal adenocarcinoma in terms of prognosis, while poor differentiation histology and tumor size were associated with a worse oncological stage and subsequently decreased survival.33 A nationwide survey in Korea comprising of 6354 patients also reported decreased survival with a worsening staging of the tumor.34

There are a few limitations to our study, most notably the lack of metastatic workup, mode of treatment, and tumor staging data, that would have further enhanced the characteristic patterns in our population. Furthermore, histological variants which were categorized into degrees of differentiation found an overlapping pattern among the keratinized, non-keratinized, infiltrating, or unidentified. For instance, most of the dysplasias were also categorized as unidentified carcinomas.

In conclusion, most of our findings were consistent with the characteristics of previous studies, while many distinct patterns were discovered which were in contrast to regional studies as previously published local data associated esophageal carcinomas with increased consumption of betel nuts and gutka in certain parts of the country.

Funding Statement

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pakzad R, Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, Khosravi B, Soltani S, Pakzad I, Mohammadian M, et al. The incidence and mortality of esophageal cancer and their relationship to development in Asia. Ann Transl Med. 2016; 4(2): 1-11. DOI: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2016.01.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang H, Fan JH, Qiao YL. Epidemiology, etiology, and prevention of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in China. Cancer Biol Med. 2017; 14(1): 33-41. DOI: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2016.0093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yousefi MS, Esfahani MS, Amiji NP, Afshar M, Gandomani HS, Otroshi O, et al. Esophageal cancer in the world: Incidence, mortality and risk factors. Biomed Res Ther. 2018; 5(7): 2504-17. DOI: 10.15419/bmrat.v5i7.460 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Din R, Mahsud I, Khan N, Iqbal K, Khan H. Study of carcinoma esophagus in Dera Ismail Khan. Gomal J Med Sci. 2010;8(2):229-231. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salehiniyah H, Hassanipour S, Mansour-Ghanaei F, Mohseni S, Joukar F, Abdzadeh E, et al. The incidence of esophageal cancer in Iran: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Ther. 2018; 5(7): 2493-2503. DOI: 10.15419/bmrat.v5i7.459 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klingelhofer D, Zhu Y, Braun M, Brugg-mann D, Schoffel N, Groneberg DA. A world map of esophageal cancer research: a critical accounting. J Transl Med. 2019; 17 (150): 1-14. DOI: 10.1186/s12967-019-1902-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alidina A, Siddiqu T, Jafri W, Hussain F, Ahmed M. Esophageal Cancer- a review. J Pak Med Assoc. 2004;54(3):136-141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jamal BS, Sharif MMA. Esophageal cancer in Pakistan. Is it really extension of Asian cancer belt? Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2010;60(2):158-60. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hou H, Meng Z, Zhao X, Ding G, Sun M, Wang W, et al. Survival of esophageal cancer in China: A pooled analysis on hospital-based studies from 2000-2018. Front Oncol. 2019; 9(548): 1-9. DOI: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amer MH. Epidemiologic Aspects of Esophageal Cancer in Saudi Arabian Patients. 1985;5(2):69-77. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aledavood A, Anvari K, Sabouri G. Esophageal cancer in Northeast of Iran. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2011;4(3):125-29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shil BC, Islam MA, Nath NC, Ahmed F. Oesophageal carcinoma: Trends and risk factors in Rural Bangladesh. J Dhaka Med Coll. 2010; 19(1): 29-32. DOI: 10.3329/jdmc.v19i1.6248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samarasam I. Esophageal cancer in India: Current status and future perspectives. Int J Adv Med Health Res. 2017;4:5-10. DOI: 10.4103/IJAMR.IJAMR_19_17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hafeez M, Majeed FA, Tariq M, Khan TS, Ateeque S, Khattak AL. Demographic variance of primary esophageal cancer, based on location and histopathology in Punjab Pakistan. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2019;69(6):1346-50. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamrah MS, Hamrah MH, Rabi M, Wu HX, Hao CN, Harun-or-Rashid M, et al. Prevalence of esophageal cancer in Northern part of Afghanistan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:10981-84. DOI: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.24.10981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang HZ, Jin GF, Shen HB. Epidemio-logic differences in esophageal cancer between Asian and Western populations. Chin J Cancer. 2012;31(6):281-86. DOI: 10.5732/cjc.011.10390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roohullah, Khursheed MA, Shah MA, Khan Z, Haider SW, Brudy GM, et al. An alarming occurrence of esophageal cancer in Balochistan. Pak J Med Res. 2005;44(2):101-4. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhurgri Y, Faridi N, Kazi LAG, Ali SK, Bhurgri H, Usman A, et al. Cancer Esophagus Karachi 1995-2002: Epidemiology, risk factors and trends. J Pak Med Assoc. 2004;54(7):345-348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of esophageal carcinoma 2018 (English version). Chin J Cancer Res. 2019;31(2):223-58. DOI: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2019.02.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Napier KJ, Scheerer M, Misra S. Esophageal cancer: A Review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, staging workup and treatment modalities. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;6(5):112-120. DOI: 10.4251/wjgo.v6.i5.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joseph D, Irukulla MM, Ahmed SF, Valiyaveeti D. Survival in Advanced Esophageal Cancer–Experience from a Tertiary Cancer Center. Int J Contemporary Med Res. 2017;4(2):350-53. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadjadi A, Marjani H, Semnani S, Moghaddarrr SN. Esophageal cancer in Iran: A review. Middle East J Cancer. 2010;1(1):5-14. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gadour MO, Ayoola EA. The frequency of upper gastrointestinal malignancy in Gizan. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(1):16-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ali A, Naseem M, Khan TM. Oesophageal cancer in Northern areas of Pakistan. J Ayub Med Coll. 2009;21(2):148-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hassan A, Majeed Y, Bashir H, Nawaz MK. Correlation between standardized up-take value and histopathology of oesophageal carcinoma: a single center analysis. J Cancer Allied Spec. 2015;1(1):1-3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathieu LN, Norma F, Kanarek, Tsai HL, Charles M, Rudin, et al. Age and Sex Differences in the Incidence of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma: Results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Registry. Dis Esophagus. 2014;27(8):757-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fatima I, Yasmin R, Kamal M, Harani M. Occurrence of esophageal carcinoma in different age group in Karachi. Pak J Pathol. 2013;24(2):1-3. Available from: https://www.pakjpath.com/index.php/Pak-J-Pathol/article/view/69 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ullah H, Imranullah M, Aslam M, Iltaf M, Adnan-ur-Rehman, Waqas M. Changing pattern of esophageal carcinoma in northwest region of Pakistan. Khyber J Med Sci. 2018;11(3):390-3. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alema ON, Iva B. Cancer of the esophagus: histopathological sub-types in northern Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2014;14(1):17-21. DOI: 10.4314/ahs.v14i1.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sultana N, Basharat S, Hanif M, Khan I, Ullah S, Shah W. Geodemographic Variations in Subtypes of Esophageal Carcinoma among Afghanis and Pakistanis Patients in Northwest Pakistan. Int J Pathol. 2018;16(4):148-153. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alidina A, Gaffar A, Hussain F, Islam M, Vaziri I, Burney A, et al. Survival data and prognostic factors seen in Pakistani patients with esophageal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:118-22. DOI: 10.1093/annonc/mdh014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delpisheh A, Veisani Y, Sayehmiri K, Rahimi E. Esophageal carcinoma: long-term survival in consecutive series of patients through a retrospective cohort study. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2014;7(2):101-7. PMID: 24834301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tustumi F, Kimura CM, Takeda FR, Uema RH, Salum RA, Ribeiro-Junior U, et al. Prognostic factors and survival analysis in esophageal carcinoma. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2016;29(3):138-41. DOI: 10.1590/0102-6720201600030003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jung H-K, Tae CH, Lee H-A, Lee H, Don Choi K, Park JC, et al. Treatment pattern and overall survival in esophageal cancer during a 13-year period: A nationwide cohort study of 6,354 Korean patients. PLoS ONE. 2020; 15(4): e0231456. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]