Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The treatment of oligometastatic (≤5 metastases) spinal disease has trended toward ablative therapies, yet to the authors’ knowledge little is known regarding the prognosis of patients presenting with oligometastatic spinal disease and the value of this approach. The objective of the current study was to compare the survival and clinical outcomes of patients with cancer with oligometastatic spinal disease with those of patients with polymetastatic (>5 metastases) disease.

METHODS:

The current study was an international, multicenter, prospective study. Patients who were admitted to a participating spine center with a diagnosis of spinal metastases and who underwent surgical intervention and/or radiotherapy between August 2013 and May 2017 were included. Data collected included demographics, overall survival, local control, and treatment information including surgical, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy details. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) measures included the EuroQOL 5 dimensions 3-level questionnaire (EQ-5D-3L), the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36v2), and the Spine Oncology Study Group Outcomes Questionnaire (SOSGOQ).

RESULTS:

Of the 393 patients included in the current study, 215 presented with oligometastatic disease and 178 presented with polymetastatic disease. A significant survival advantage of 90.1% versus 77.3% at 3 months and 77.0% versus 65.1% at 6 months from the time of treatment was found for patients presenting with oligometastatic disease compared with those with polymetastatic disease. It is important to note that both groups experienced significant improvements in multiple HRQOL measures at 6 months after treatment, with no differences in these outcome measures noted between the 2 groups.

CONCLUSIONS:

The treatment of oligometastatic disease appears to offer a significant survival advantage compared with polymetastatic disease, regardless of treatment choice. HRQOL measures were found to improve in both groups, demonstrating a palliative benefit for all treated patients.

Keywords: health-related quality of life (HRQOL), oligometastases, polymetastases, spine, survival, tumor

INTRODUCTION

Treatment goals for patients with metastatic spinal disease primarily are palliative. These include the preservation of neurologic function, local tumor control, the restoration of spinal stability, and symptom palliation leading to improved quality of life (QOL). According to the American Cancer Society, in 2017, nearly 1.7 million new cancer cases were diagnosed.1 Up to 40% of these patients will develop metastatic disease to the spine, and of those, 10% to 20% are likely to develop spinal cord compression.2,3 Considering improved clinical diagnostics, the implementation of new targeted therapies, and technological advancements leading to prolonged survival, the scale of this problem is likely to grow. In patients with cancer, survival estimation plays an important role in treatment selection and numerous survival prediction instruments have been developed.4,5

First proposed in 1995, oligometastatic disease is believed to be an intermediate cancer state of limited metastatic capacity and is a characteristic of many tumors during their clinical evolution.6 To the best of our knowledge, no clear definition of oligometastatic disease currently is available, but previous reports have defined it as ≤5 metastases.7,8 Patients with oligometastatic disease have been shown to have better prognoses than those with multiple metastatic sites, with some patients attaining long-term survival.9 More specifically, patients with oligometastatic disease of the spine have been hypothesized to have a more favorable survival compared with patients with synchronous metastatic disease in other sites, and thus have been believed to benefit from more aggressive treatments, such as an ablative rather than a palliative dose of radiotherapy (RT).10 Data regarding the actual prognosis of patients presenting with oligometastatic spinal disease are scarce and the value of an ablative treatment approach remains unclear. The current study examined the effect of oligometastatic disease state on the survival and treatment outcomes of patients with spinal metastases to delineate clinical outcomes and optimize future treatment goals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The current study was part of an international, multicenter, prospective cohort study performed by the AOSpine Knowledge Forum Tumor and including 10 tertiary spine centers across North America and Europe (Epidemiology, Process and Outcomes of Spine Oncology [EPOSO]; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01825161). The study included patients aged 18 to 75 years who underwent surgery and/or RT for symptomatic spinal metastases. Patients were excluded if they were admitted for the treatment of a primary spinal tumor or were diagnosed with a primary spinal cord tumor. The research protocol was approved by the local ethics board of each of the participating spine centers and informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Patients were included in the analyses if they were admitted to a participating spine center with a diagnosis of spinal metastases, underwent surgical intervention and/or RT between August 2013 and May 2017, and reached a 3-month follow-up visit or died before then.

Prospectively collected data included demographic data, survival, local tumor control, tumor histology, number and location of spinal metastases, Epidural Spine Cord Compression (ESCC) as defined by the ESCC score,11 spinal instability as defined by the Spinal Instability Neoplastic Score (SINS),12 and systemic disease burden. Treatment information collected included surgical and RT details and the use of adjuvant therapies. Measures of health-related QOL (HRQOL) included a numeric rating scale (NRS) for pain. The EuroQOL 5 dimensions 3-level questionnaire (EQ-5D-3L), 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36v2), and the Spine Oncology Study Group Outcomes Questionnaire (SOSGOQ) were evaluated at baseline and during follow-up at fixed time points until 2 years after treatment or death. Data regarding functional status as defined by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) also were collected. Data were captured and stored in a secure Web-based application (REDCap; Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee).

The extent of systemic disease was assessed by the treating physician at each individual participating site. At the time of the initial presentation, aside from the treated index spinal lesion, other known sites of disease involvement were specified as none, visceral, brain, axial skeletal (spine/pelvis), appendicular skeletal, or other. The number of metastases likewise was specified as ≤5 or >5.

Patients were classified as having oligometastatic disease or polymetastatic disease based on the following definitions. Patients were considered to have oligometastatic disease when they demonstrated 1 to 5 spinal metastases with no other systemic metastases or 1 spinal metastasis and ≤5 systemic metastases. Patients were defined as having polymetastatic disease when they demonstrated >5 systemic metastases, >1 spinal metastases and ≤5 systemic metastases, or >5 spinal metastases with no other systemic metastases.

It is interesting to note that, as previously mentioned, to the best of our knowledge no clear definition of oligometastatic disease currently is available, and because 5 metastases was a commonly used number in previous reports,7,8 it was selected for the current analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to represent demographic data (mean and the standard deviation or median for continuous variables and the absolute number and frequency distribution for categorical variables). Student t tests and chi-square tests were used to compare differences in continuous variables and proportions between patients who underwent surgery and/or RT. The Cochran-Armitage test for trend was applied to detect linear differences in ordinal baseline parameters (ECOG, American Spinal Injury Association, and ESCC). Mixed effect models were used to model differences in clinical outcomes (NRS pain, SOSGOQ, SF-36v2, and EQ-5D-3L) over time between the surgery and/or RT group. The mixed effect models were adjusted for treatment; baseline ECOG, American Spinal Injury Association, and SINS scores; and the duration of symptoms. The log-rank test was used to compare overall survival up to 2 years after treatment between both analysis groups. Patients who did not reach the final study visit were censored at the time of their last visit. Significance was defined as P<.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

A total of 393 patients were included in the current analysis, 215 of whom presented with oligometastatic disease and 178 of whom presented with polymetastatic disease. The oligometastatic group was comprised of 110 patients with 1 to 5 spinal metastases and no other systemic metastases and 105 patients with 1 spinal metastasis and ≤5 systemic metastases. The polymetastatic group was comprised of 98 patients with >5 systemic metastases, 79 patients with >1 spinal metastases and ≤5 systemic metastases, and 1 patient with >5 spinal metastases and no other systemic metastases. Approximately 54% of the patients were female and the mean age of the patients at the time of spine treatment was 58.7 years (standard deviation, 10.5 years). Patient demographics and treatment characteristics are outlined in Table 1. Baseline functional status is shown in Table 2. Radiologic evidence of spinal cord compression as described using the ESCC score and evidence of spinal instability using the SINS score were found to be more favorable in the oligometastatic group (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Oligometastatic Disease N=215 |

Polymetastatic Disease N=178 |

Total N=393 |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, no. (%) | .836a | |||

| Female | 117 (54.4) | 95 (53.4) | 212 (53.9) | |

| Male | 98 (45.6) | 83 (46.6) | 181 (46.1) | |

| Age at surgery/RT, y | .013b | |||

| Median (Q1; Q3) | 63.0 (53.0; 68.0) | 59.0 (52.0; 65.0) | 60.0 (53.0; 66.0) | |

| Treatment group, no. (%) | .716a | |||

| Surgery (±RT) | 129 (60.0) | 110 (61.8) | 239 (60.8) | |

| Anterior approach | 6 (5.4) | 7 (6.9) | 13 (6.1) | |

| Posterior approach | 104 (92.9) | 88 (87.1) | 192 (90.1) | |

| Combined approach | 2 (1.8) | 6 (5.9) | 8 (3.8) | |

| RT alone | 86 (40.0) | 68 (38.2) | 154 (39.2) | |

| cEBRT | 23 (26.7) | 43 (63.2) | 66 (42.9) | |

| Stereotactic radiosurgery | 63 (73.3) | 25 (36.8) | 88 (57.1) | |

| Group classification, no. (%) | ||||

| No other site(s) of metastases and 1–5 spinal mets | 105 (48.8) | - | 105 (26.7) | |

| 1–5 systemic mets and 1 spinal met | 110 (51.2) | - | 110 (28.0) | |

| >5 systemic mets and >0 spinal mets | - | 98 (55.1) | 98 (24.9) | |

| 1–5 systemic mets and >1 spinal met | - | 79 (44.4) | 79 (20.1) | |

| No other site(s) of mets and >5 spinal mets | - | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | |

Abbreviations: cEBRT, conventional external-beam radiotherapy; mets, metastases; Q, quartile; RT, radiotherapy.

Derived using the chi-square test.

Derived using the Student t test.

TABLE 2.

Baseline Neurooncological Characteristics

| Characteristic | Oligometastatic Disease | Polymetastatic Disease | Total | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOG classification, no. (%) | 213 | 174 | 387 | .113 |

| 0 | 48 (22.5) | 20 (11.5) | 68 (17.6) | |

| 1 | 94 (44.1) | 86 (49.4) | 180 (46.5) | |

| 2 | 34 (16.0) | 34 (19.5) | 68 (17.6) | |

| 3 | 26 (12.2) | 28 (16.1) | 54 (14.0) | |

| 4 | 11 (5.2) | 6 (3.4) | 17 (4.4) | |

| 5 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| ASIA Impairment Scale, no. (%) | 213 | 176 | 389 | .273 |

| A | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | |

| B | 4 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) | 5 (1.3) | |

| C | 8 (3.8) | 6 (3.4) | 14 (3.6) | |

| D | 24 (11.3) | 40 (22.7) | 64 (16.5) | |

| E | 176 (82.6) | 128 (72.7) | 304 (78.1) | |

| ESCC, no. (%) | 204 | 161 | 365 | .003 |

| 0 | 63 (30.9) | 32 (19.9) | 95 (26.0) | |

| 1a | 33 (16.2) | 17 (10.6) | 50 (13.7) | |

| 1b | 26 (12.7) | 23 (14.3) | 49 (13.4) | |

| 1c | 14 (6.9) | 20 (12.4) | 34 (9.3) | |

| 2 | 43 (21.1) | 39 (24.2) | 82 (22.5) | |

| 3 | 25 (12.3) | 30 (18.6) | 55 (15.1) | |

| Total SINS score, no. (%) | 213 | 173 | 386 | <.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 8.8 (3.5) | 10.1 (3.5) | 9.4 (3.6) | |

| Median (Q1;Q3) | 8.0 (7.0;12.0) | 10.0 (8.0;12.0) | 9.0 (7.0;12.0) | |

Abbreviations: ASIA, American Spinal Injury Association; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ESCC, Epidural Spinal Compression Score; Q, quartile; SD, standard deviation; SINS, Spinal Instability Neoplastic Score.

Baseline functional status at the time of presentation is shown in the ECOG and ASIA scores. Baseline radiologic data demonstrated significantly worse SINS scores and higher grades of ESCC in those patients with polymetastatic disease.

The most prevalent histologies were breast and lung carcinomas. The mean follow-up period was 238.5 days and the mean time from the initial cancer diagnosis to the diagnosis of spinal metastases was 1470 days. There was a borderline significant trend (P=.067) toward better control of the primary tumor site observed for those patients with oligometastatic disease at the time of presentation with spinal metastases (Table 3). There were no significant differences noted with regard to the number of levels decompressed or instrumented or the surgical approach used (posterior, anterior, or combined between the groups), with the majority of cases having surgery performed in a posterior-only approach in both groups. Patients with oligometastatic disease experienced shorter lengths of hospitalization (mean, 11.0 days vs 14.9 days; median, 9 days vs 11 days, respectively [P=.030]).

TABLE 3.

Overview of Tumor Characteristics

| Characteristic | Oligometastatic Disease N=215 |

Polymetastatic Disease N=178 |

Total N=393 |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site of the primary cancer (grouped), no. (%) | 215 | 178 | 393 | .855 |

| Breast | 55 (25.6) | 49 (27.5) | 104 (26.5) | |

| Lungs | 38 (17.7) | 30 (16.9) | 68 (17.3) | |

| Prostate | 24 (11.2) | 13 (7.3) | 37 (9.4) | |

| Kidney | 29 (13.5) | 27 (15.2) | 56 (14.2) | |

| Myeloma | 10 (4.7) | 9 (5.1) | 19 (4.8) | |

| Other | 59 (27.4) | 50 (28.1) | 109 (27.7) | |

| Time since primary tumor diagnosis, moa | .773 | |||

| No. | 215 | 178 | 393 | |

| Mean (SD) | 46.1 (56.1) | 50.9 (67.0) | 48.3 (61.2) | |

| Median (Q1; Q3) | 24.0 (5.0; 70.0) | 25.5 (4.0; 70.0) | 25.0 (5.0; 70.0) | |

| Primary cancer site controlled, no. (%)b | 214 | 173 | 387 | .067 |

| No | 57 (26.6) | 61 (35.3) | 118 (30.5) | |

| Yes | 157 (73.4) | 112 (64.7) | 269 (69.5) |

Abbreviations: Q, quartile; SD, standard deviation.

No significant differences were found between tumor histologies or time from initial diagnosis to time of spinal metastases treatment between the groups.

Calculated as the date of surgery/radiotherapy (after study enrollment) minus the date of the primary tumor diagnosis.

At the time of treatment of the spinal tumor, was the primary tumor site controlled?

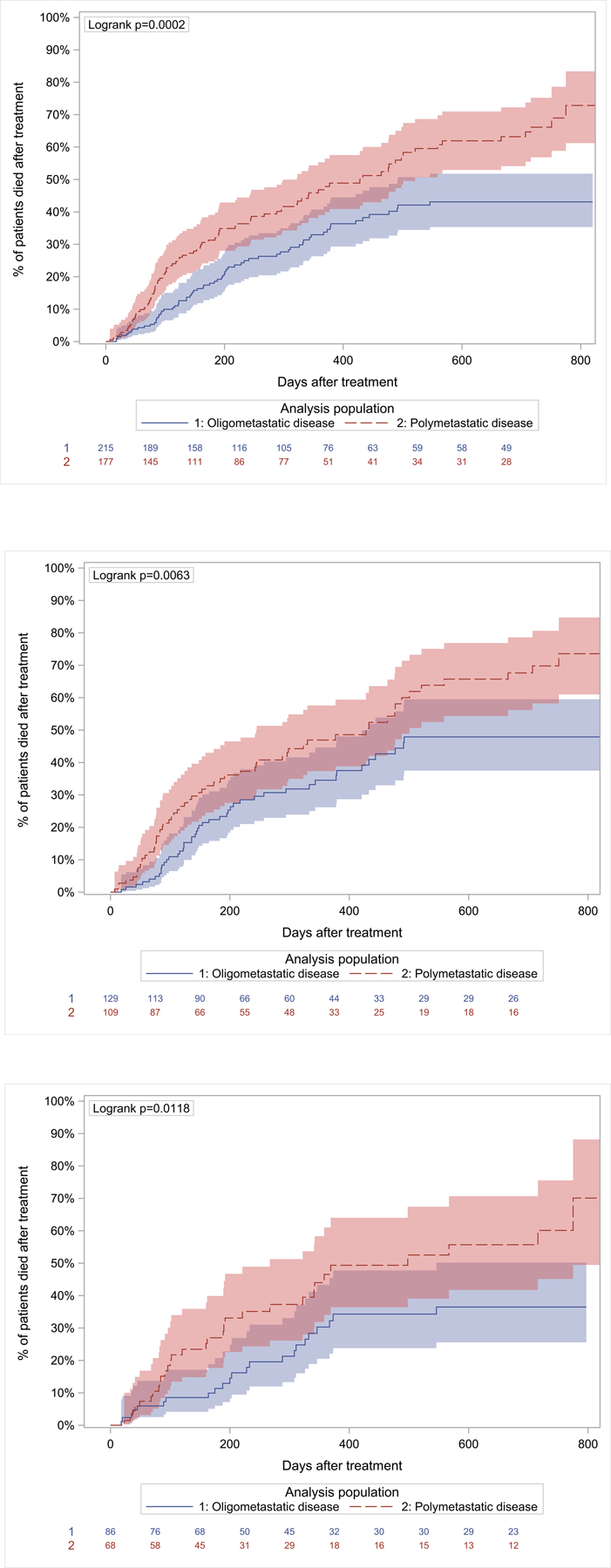

A significant overall survival advantage was noted for patients with oligometastatic disease compared with those with polymetastatic disease: 95.7% versus 90.1% at 6 weeks, 90.1% versus 77.3% at 3 months, and 77.0% versus 65.1% at 6 months from the time of treatment. This difference remained statistically significant for those treated with RT alone as well as for those treated surgically (Fig. 1). Moreover, a significant survival advantage was found in a subgroup analysis of the oligometastatic group comparing patients with a single spinal metastasis with those with 2 to 5 metastases, including other sites (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier plots demonstrating 2-year overall mortality differences for patients with oligometastatic (in blue) and polymetastatic (in red) disease, including 95% confidence limits and patients at risk. (Top) Entire patient cohort. (Center) Patients treated with surgery with or without radiotherapy. (Bottom) Patients treated with radiotherapy alone.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plot demonstrating 2-year overall mortality differences for patients with solitary spine metastases (in blue) and the rest of the oligometastatic cohort (in red), including 95% confidence limits and patients at risk. Mets indicates metastases.

Progression-free survival rates based on local control were 90.1% and 85.1%, respectively, at 3 months; 81.5% and 74.4%, respectively, at 6 months; and 71.4% and 61.3%, respectively, at 1 year after treatment in the oligometastatic group compared with the polymetastatic group. These differences did not achieve statistical significance.

Local control rates for patients treated with surgery with or without RT (239 patients) were 89.2% and 88.5%, respectively, at 3 months; 76.6% and 73.1%, respectively, at 6 months; and 65.5% and 62.5%, respectively, at 1 year after treatment in the oligometastatic group compared with the polymetastatic group. Of the patients treated surgically, 29 patients in the oligometastatic group received postoperative stereotactic body RT (SBRT) (median total dose, <zaq;3>24 grays [Gy]; median number of fractions, 2), as did 24 patients in the polymetastatic group (median total dose, 24 Gy; median number of fractions, 3). A total of 28 patients in the oligometastatic group received postoperative conventional external-beam RT (cEBRT) (median total dose, 22 Gy; median number of fractions, 5), and 23 patients in the polymetastatic group did so (median total dose, 30 Gy; median number of fractions, 5).

Of the patients treated with RT only, 63 patients in the oligometastatic group received SBRT (median dose total dose, 24 Gy; median number of fractions, 2), and 25 in the polymetastatic group (median total dose, 24 Gy; median number of fractions, 2). Of the patients in the oligometastatic group, 23 received cEBRT (median total dose, 20 Gy; median number of fractions, 5) and 43 patients did in the polymetastatic group (median total dose, 20 Gy; median number of fractions, 4). Thus, of the patients with oligometastatic disease who were treated with RT alone, approximately 73.3% were treated with SBRT compared with 36.8% in the polymetastatic group. Local control rates of patients with oligometastatic disease who were treated with SBRT were 92.3% at 3 months, 88.6% at 6 months, and 84.8% at 1 year compared with 87.5% at 3 months, 81.3% at 6 months, and 57.1% at 1 year after treatment in those treated with conventional RT, although these differences did not reach statistical significance. Differences in overall survival and HRQOL did not achieve statistical significance.

In a subgroup analysis of patients with a solitary spinal metastasis (70 patients) compared with the rest of the patients in the oligometastatic disease group (145 patients), local control rates were 94.2% versus 87.8% at 3 months, 91.8% versus 74.4% at 6 months (P=.016), and 86.4% versus 59.3% at 1 year after treatment (P=.003).

At 6 months after treatment, there were significant improvements noted with regard to measures of HRQOL for both the oligometastatic and polymetastatic groups. Significant (P<.001) improvements compared with baseline were demonstrated in the SOSGOQ (version 2.0), EQ-5D-3L, and NRS pain scores for both groups. Patients with oligometastatic disease also demonstrated improvements in the mental component score of the SF-36v2 (P=.011) and those with polymetastatic disease were found to demonstrate improvements in the physical component score of the SF-36v2 (P=.011) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Outcomes regarding health-related quality of life. Differences in the mean scores of outcome endpoints were calculated at 6 months for each group. EQ 5D indicates EuroQOL 5 dimensions questionnaire; Pain NRS, numeric rating scale for pain; SF-36v2 MCS, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey mental component score; SF-36v2 PCS, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey physical component score; SOSGOQ2.0, Spine Oncology Study Group Outcomes Questionnaire 2. *P<.001.

DISCUSSION

The results of the current international, multicenter, collaborative study demonstrated a survival advantage for patients presenting with oligometastatic disease compared with those with polymetastatic disease at the time of treatment of spinal metastases. This survival advantage was apparent regardless of the method of spine treatment. It is interesting to note that the data presented herein demonstrated that both groups experienced significant improvements in HRQOL measures, with no differences observed with regard to the evaluated outcome measures between the 2 groups (ie, neither group improved significantly more from baseline compared with the other).

Oligometastatic disease, first proposed by Hellman and Weichselbaum,6 is believed to be an intermediate cancer state of limited metastatic capacity. This is compared with the Halsted theory,13 which proposed that cancer spread is orderly, extending in a contiguous fashion from the primary tumor through the lymphatics to distant sites, and with the systemic hypothesis,14 which hypothesized that clinically apparent cancer is a systemic disease. Whereas in the Halsted theory radical tumor resections were believed to be curative, the systemic theory relies on systemic treatment, with a limited role noted for the local treatment of metastases. Prolonged survival previously has been linked with oligometastatic cancer.9,15–17 The proponents of oligometastatic theory favor ablative local therapy for the treatment of metastases because the theory suggests that the oligometastatic tumors have limited propensity for dissemination and growth and that the local control of metastases may result in prolonged survival or even cure.

The data demonstrated in the current analysis provide evidence of a survival advantage from the time of treatment of spinal metastases for patients with oligometastatic disease. This supports the theory of an intermediate cancer state with a better prognosis. A subgroup analysis demonstrated a survival advantage and better local control rates at 6 months and 12 months within the oligometastatic group for those patients treated for a single/solitary spinal metastasis. This likely demonstrates the current practice of more aggressive treatment, both surgical and radiosurgical, for patients with a solitary spinal metastasis.18 The data from the current study also demonstrated that patients with oligometastatic disease who were treated with RT alone were more likely to be treated with radiosurgery than conventional RT, reflecting the existing trend to treat patients with oligometastatic disease with ablative goals. Ho et al recently reported their experience with SBRT for the treatment of patients with oligometastatic spinal disease.10 They demonstrated that patients with oligometastatic disease of the spine who are treated with SBRT can achieve long-term survival and experience a long duration before requiring a modification in systemic therapy, with excellent local control and minimal late toxicity. Thibault et al demonstrated improved overall survival and local control in patients with oligometastatic renal cell cancer spinal metastases who were treated with SBRT, suggesting that this subpopulation is likely to benefit the most from ablative treatment.19 Furthermore, in the current analysis, those patients treated with radiosurgery demonstrated a trend toward better local control over time compared with those treated with conventional RT. Although the local control rate at 1 year suggested a gain of 27.7% in local control with SBRT versus cEBRT, the limited sample size likely explains the nonsignificance observed. Dedicated and appropriately powered randomized trials for spinal SBRT currently are ongoing that will clarify its potential benefits.

Outcome analysis is a major focus of current cancer research. Accumulated data have demonstrated improvements in HRQOL after spinal SBRT.20,21 This also has been shown prospectively in a phase 1/2 study in which SBRT was demonstrated to be an effective treatment among patients with mechanically stable spinal metastases with a significant and durable reduction in pain and other symptoms noted at the 6-month follow-up.22 Similarly, prospective data demonstrated that surgery, as an adjunct to RT and chemotherapy, provides durable improvements in measures of HRQOL with limited risks.23,24 The data presented herein demonstrated no significant difference in HRQOL between patients with oligometastatic and polymetastatic disease at baseline and a significant benefit of treatment at 6 months after treatment for both groups. This improvement was noted in various HRQOL tools for both groups, and was not significantly different between the groups, thus validating a palliative treatment benefit for all patients in the current analysis. These data are based on the metastatic site treated and therefore highlight the importance of and benefit from the treatment of spinal metastases.

Patient selection is an important determinant in spinal oncology. The proposed treatments (ie, surgery or RT) are predicated on whether or not the patient can tolerate the proposed treatment and, furthermore, will they outlive the benefit of these interventions. Historical scoring systems such as the Tokuhashi et al5 and Tomita et al4 systems and modified Bauer and Weden25 and Leithner et al26 scores have been used to estimate expected survival in patients with spinal metastases. Treatment options were based largely on these predictions alone. With modern cancer care, the value and reliability of these predictions are uncertain.27,28 New prediction models29 have attempted to overcome the shortcomings of these older models, yet to the best of our knowledge their usefulness also remains unknown. A recent study critically reviewed the current literature in an attempt to identify key preoperative prognostic factors of clinical outcomes in patients with symptomatic spinal metastases who were treated surgically.30 The authors concluded that the quality of evidence for predictors of survival is, at best, low. Furthermore, no studies that evaluated preoperative prognostic factors for neurological, functional, or HRQOL outcomes in surgical patients with symptomatic spinal metastases were identified.

The classification of oligometastatic disease in the literature is arbitrary and, as previously mentioned, to our knowledge no strict definition currently is available. Five metastases is a commonly used number in previous reports,7,8 and therefore was selected for the current analysis. The lack of a clear definition of oligometastatic disease is a limitation of this study. Furthermore, accurate data collection of the exact numbers of metastases is challenging and reflects the complexity in uniform reporting in multicenter trials, limiting data granularity. For the current analysis, to avoid selection bias, patients with >1 spinal metastases and <5 systemic metastases were included in the polymetastatic disease group. The focus of the current study was spinal disease and treatment, and we believe that the multiplicity of metastatic sites in this subgroup reflects a more disseminated disease. Therefore, these patients were defined as having polymetastastic disease, albeit the possibility exists that some patient who was included in this group could have had ≤5 metastases.

The results of the current analysis demonstrate a benefit from the treatment of spinal metastases with regard to both local tumor control and measures of HRQOL for all patients regardless of disease state. The survival advantage demonstrated in the population of patients with oligometastatic disease supports the oligometastatic theory and further supports the current trend of aggressive local treatment in this population. It is interesting to note that there were several limitations to the current study, the majority of which reflect the complexity of data collection in multi-institutional cohorts. Furthermore, for some subgroup analyses, the numbers of patients in each group were not large enough to draw significant conclusions.

Conclusions

At time of diagnosis of spinal metastatic disease, patients with oligometastatic disease have a significant survival advantage when compared with those with polymetastatic infiltration, regardless of treatment choice. Local control can be achieved with the proper treatment of spinal metastases in both groups. Measures of HRQOL are found to improve in both groups after treatment, thus demonstrating a palliative treatment benefit. The current results, with a focus on patients with spinal metastatic tumors, support the oligometastatic theory of an intermediate cancer state of limited metastatic capacity.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our gratitude to Mr. Christian Knoll for statistical analysis. We are grateful to the collaborating centers’ local clinical support staff and research assistants for their contributions.

FUNDING SUPPORT

This study was organized and funded by AOSpine International through the AOSpine Knowledge Forum Tumor, a focused group of international spine oncology experts acting on behalf of AOSpine. Study support was provided directly through the AOSpine Research Department and the AO Clinical Investigation and Documentation units. A research grant for the current study was received from the Orthopedic Research and Education Foundation.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Ori Barzilai has received fellowship support to his institution from Globus for work performed outside of the current study. Anne L. Versteeg has received consulting and travel accommodations from AOSpine International for work performed outside of the current study. Arjun Sahgal has acted as a paid advisor for AbbVie; has taken part in past educational seminars with Elekta AB, Accuray Inc, Varian Medical Systems, and Brainlab; has received a research grant from Elekta AB; has received travel accommodations and expenses from Elekta AB, Varian Medical Systems, and Brainlab; and is a member of the Elekta MR Linac Research Consortium for work performed outside of the current study. Laurence D. Rhines has educational commitments with Stryker for work performed outside of the current study. Mark H. Bilsky has acted as a member of the Speaker’s Bureau for Varian Medical Systems and Brainlab, has received royalties from DePuy Synthes, and has received royalties/fellowship support from Globus Spine for work performed outside of the current study. Daniel M. Sciubba has acted as a paid consultant for Medtronic, DePuy Synthes, Stryker, NuVasive, K2M, Baxter, and Misonix for work performed outside of the current study. Chetan Bettegowda has acted as a paid consultant for DePuy Synthes for work performed outside of the current study. Yoshiya Yamada has acted as a member of the Speakers’ Bureau for Varian Medical Systems, Brainlab, Vision RT, and the Institute for Medical Education for work performed as part of the current study and has acted as a member of the Medical Advisory Board for the Chordoma Foundation for work performed outside of the current study. Paul M. Arnold has received travel accommodations and expenses from AOSpine North America; has intellectual property rights and interests, equity, and a position of responsibility as part of Evoke Medical; has equity from Z-Plasty; has received consulting fees from Stryker Orthopaedics, Ulrich, SpineGuard, In Vivo Therapeutics, and In Vivo; and has received consulting fees, travel accommodations, and expenses from Stryker Spine, Spine Wave, and Medtronic for work performed outside of the current study. Ziya L. Gokaslan has received research support from AOSpine North America and has stock ownership in Spinal Kinetics for work performed outside of the current study. Charles G. Fisher has received consulting and royalty fees from Medtronic, has received research grants from the Orthopedic Research and Education Foundation, and has received fellowship support paid to his institution from AOSpine and Medtronic for work performed outside of the current study. Ilya Laufer has received personal fees from Globus, Medtronic, DePuy Synthes, Spine Wave, and Brainlab for work performed outside of the current study.

There appears to be a significant survival advantage for patients presenting with oligometastatic disease compared with those with polymetastatic disease at the time of the initial treatment of spinal metastases regardless of the treatment method used. In the current study, both groups are reported to experience significant improvements in multiple measures of health-related quality of life at 6 months.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinson GP, Zager EL. Metastases and spinal cord compression. N Engl J Med 1992;327:1953–1954; author reply 1954–1955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong DA, Fornasier VL, MacNab I. Spinal metastases: the obvious, the occult, and the impostors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990;15:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomita K, Kawahara N, Kobayashi T, Yoshida A, Murakami H, Akamaru T. Surgical strategy for spinal metastases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;6:298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tokuhashi Y, Matsuzaki H, Oda H, Oshima M, Ryu J. A revised scoring system for preoperative evaluation of metastatic spine tumor prognosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:2186–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hellman S, Weichselbaum RR. Oligometastases. J Clin Oncol 1995;13:8–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milano MT, Katz AW, Muhs AG, et al. A prospective pilot study of curative-intent stereotactic body radiation therapy in patients with 5 or fewer oligometastatic lesions. Cancer. 2008;112:650–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salama JK, Hasselle MD, Chmura SJ, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for multisite extracranial oligometastases: final report of a dose escalation trial in patients with 1 to 5 sites of metastatic disease. Cancer. 2012;118:2962–2970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salama JK, Milano MT. Radical irradiation of extracranial oligometastases. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2902–2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho JC, Tang C, Deegan BJ, et al. The use of spine stereotactic radiosurgery for oligometastatic disease. J Neurosurg Spine. 2016;25:239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilsky MH, Laufer I, Fourney DR, et al. Reliability analysis of the epidural spinal cord compression scale. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13:324–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher CG, DiPaola CP, Ryken TC, et al. A novel classification system for spinal instability in neoplastic disease: an evidence-based approach and expert consensus from the Spine Oncology Study Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:E1221–E1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halsted WSI The Results of Operations for the Cure of Cancer of the Breast Performed at the Johns Hopkins Hospital from June, 1889, to January, 1894. Ann Surg 1894;20:497–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher B Laboratory and clinical research in breast cancer-a personal adventure: the David A. Karnofsky memorial lecture. Cancer Res 1980;40:3863–3874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh D, Yi WS, Brasacchio RA, et al. Is there a favorable subset of patients with prostate cancer who develop oligometastases? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004;58:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fode MM, Hoyer M. Survival and prognostic factors in 321 patients treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy for oligo-metastases. Radiother Oncol 2015;114:155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong AC, Watson SP, Pitroda SP, et al. Clinical and molecular markers of long-term survival after oligometastasis-directed stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT). Cancer. 2016;122:2242–2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sciubba DM, Nguyen T, Gokaslan ZL. Solitary vertebral metastasis. Orthop Clin North Am 2009;40:145–154, viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thibault I, Al-Omair A, Masucci GL, et al. Spine stereotactic body radiotherapy for renal cell cancer spinal metastases: analysis of outcomes and risk of vertebral compression fracture. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;21:711–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng L, Chow E, Zhang L, et al. Comparison of pain response and functional interference outcomes between spinal and non-spinal bone metastases treated with palliative radiotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:633–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu JS, Monk G, Clark T, Robinson J, Eigl BJ, Hagen N. Palliative radiotherapy improves pain and reduces functional interference in patients with painful bone metastases: a quality assurance study. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2006;18:539–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang XS, Rhines LD, Shiu AS, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for management of spinal metastases in patients without spinal cord compression: a phase 1–2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:395–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi D, Fox Z, Albert T, et al. Rapid improvements in pain and quality of life are sustained after surgery for spinal metastases in a large prospective cohort. Br J Neurosurg 2016;30:337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fehlings MG, Nater A, Tetreault L, et al. Survival and clinical outcomes in surgically treated patients with metastatic epidural spinal cord compression: results of the prospective multicenter AOSpine Study. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:268–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bauer HC, Wedin R. Survival after surgery for spinal and extremity metastases. Prognostication in 241 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 1995;66:143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leithner A, Radl R, Gruber G, et al. Predictive value of seven preoperative prognostic scoring systems for spinal metastases. Eur Spine J 2008;17:1488–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zoccali C, Skoch J, Walter CM, Torabi M, Borgstrom M, Baaj AA. The Tokuhashi score: effectiveness and pitfalls. Eur Spine J 2016;25:673–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dardic M, Wibmer C, Berghold A, Stadlmueller L, Froehlich EV, Leithner A. Evaluation of prognostic scoring systems for spinal metastases in 196 patients treated during 2005–2010. Eur Spine J 2015;24:2133–2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paulino Pereira NR, Janssen SJ, van Dijk E, et al. Development of a prognostic survival algorithm for patients with metastatic spine disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2016;98:1767–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nater A, Martin AR, Sahgal A, Choi D, Fehlings MG. Symptomatic spinal metastasis: a systematic literature review of the preoperative prognostic factors for survival, neurological, functional and quality of life in surgically treated patients and methodological recommendations for prognostic studies. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]