Abstract

Biotribology is one of the key branches in the field of artificial joint development. Wear and corrosion are among fundamental processes which cause material loss in a joint biotribological system; the characteristics of wear and corrosion debris are central to determining the in vivo bioreactivity. Much effort has been made elucidating the debris-induced tissue responses. However, due to the complexity of the biological environment of the artificial joint, as well as a lack of effective imaging tools, there is still very little understanding of the size, composition, and concentration of the particles needed to trigger adverse local tissue reactions, including periprosthetic osteolysis. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic imaging (FTIR-I) provides fast biochemical composition analysis in the direct context of underlying physiological conditions with micron-level spatial resolution, and minimal additional sample preparation in conjunction with the standard histopathological analysis workflow. In this study, we have demonstrated that FTIR-I can be utilized to accurately identify fine polyethylene debris accumulation in macrophages that is not achievable using conventional or polarized light microscope with histological staining. Further, a major tribocorrosion product, chromium phosphate, can be characterized within its histological milieu, while simultaneously identifying the involved immune cell such as macrophages and lymphocytes. In addition, we have shown the different spectral features of particle-laden macrophages through image clustering analysis. The presence of particle composition variance inside macrophages could shed light on debris evolution after detachment from the implant surface. The success of applying FTIR-I in the characterization of prosthetic debris within their biological context may very well open a new avenue of research in the orthopedics community.

Keywords: Implant wear and corrosion, FTIR imaging, Adverse tissue response

Introduction

Wear of total joint replacements (TJR) has been a major topic in the biotribology research community since its beginning1–7. Initially the focus had been on the role of polyethylene wear in the initiation and progression of periprosthetic osteolysis. Specifically, polyethylene wear particles were associated with a severe macrophage-mediated response that could trigger a cascade of events leading to bone dissolution around the implant and implant loosening8–12. The focus of the research community has always been twofold: 1) A thorough understanding of the tribological system to identify targets to minimize the release of wear debris13–17, and 2) the periprosthetic tissue response to wear debris of different sizes and chemical structure18–21. Particles in the micrometer range and their association with macrophages can easily be identified using light microscopy of H&E stained periprosthetic tissue sections. Great progress has been made to reduce the polyethylene wear rate of total knee (TKR) and hip replacements (THR) by the introduction of highly crosslinked polyethylene (HXPE) and more recently vitamin-E doped HXPE22,23. Therefore, the wear rate of contemporary implants has significantly decreased and the prevalence of wear-related complications has been reduced24–27. However, it is unknown whether the onset of osteolysis has only been postponed, with failures occurring at a later time point28,29. Considering the decreasing age and increasing number of primary TJA patients, osteolysis is still a concern. Therefore, it remains important to monitor the propensity for the development of wear particle-induced osteolysis as retrieved implants of the new generation materials become available for analysis. However, wear particles from contemporary PE implant components are significantly smaller and are near or below the resolution of the light microscope30,31. Experienced histologists familiar with TJR-related pathologies can identify PE related macrophage responses within periprosthetic tissue, yet for most investigators it is difficult to identify a reaction to PE debris, especially at its early onset.

In recent years, another clinical problem related to implant debris has moved to the forefront which is known as adverse local tissue reactions (ALTRs)32–36. This type of tissue response was first associated with wear debris of high wearing metal-on-metal THRs and hip resurfacing implants. However, ALTRs have also been shown to prominently occur in the more common metal-on-polyethylene THRs due to the release of corrosion products generated under fretting-corrosion conditions within modular taper junctions33. ALTRs are known to cause pain and extensive joint tissue destruction to the patient, often leading to multiple revision surgeries and reoccurring complications. The histopathological pattern associated with ALTRs is dominated by the destruction of the synovial surface, widespread necrosis, and the presence of an extensive lymphocyte infiltrate. Macrophages laden with corrosion products are also present. The most prominent corrosion product in cases with ALTRs is chromium phosphate (CrPO4)37–39. Usually, large flakes can be observed within necrotic tissue and fibrin exudate, with finer particles within macrophages. Most studies report the presence of CrPO4 by the characteristic green color and glassy morphology under the light microscope, or by the presence of Cr, P, and O in energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDS) scans38,40–42.

Considering the clinical significance of osteolysis and ALTR, it is imperative to study retrieved periprosthetic tissues to gain a better understanding of the interaction between tissues and wear debris or tribocorrosion products. A new tool for this task is Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy imaging (FTIR-I), which enables rapid and simultaneous analysis of the chemical structure of biological tissue and implant debris with a high spatial resolution43–47. This technique can be conducted in parallel to histopathological analysis with minimal additional sample preparation. The molecular information encoded in the spectrum provides a unique ‘fingerprint’ of the tissue at each pixel and is directly correlated with morphological features of the sample. This label-free imaging approach is less labor-intensive compared to conventional histopathological practice, and has advantages over other vibrational spectroscopy techniques, e.g., Raman micro-spectroscopy. FTIR-I allows larger image acquisition with wider spectral range, and its entire process is non-perturbing to the sample itself enabling further downstream analysis. The FTIR-I datasets are typically presented in a univariate form (i.e. at one wavenumber, or integrated range) as a heat map to visualize a specific chemical species, but it provides the most information through data classification carried out by unsupervised multivariate methods such as hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) or Fuzzy C-means clustering (FCM)48,49. It is the goal of this study to demonstrate the beneficial use of both univariate and multivariate FTIR-I analysis in the chemical characterization of wear and tribocorrosion products within periprosthetic tissue as well as the associated cell responses.

Methods

Joint capsule tissue from 3 retrieved THRs with different bearing couples and different histopathological findings was studied. All tissue samples are from the IRB approved tissue retrieval repository at Department of Orthopedics Rush University Medical Center. Case 1 was a metal-on-polyethylene THR with a highly crosslinked PE cup that exhibited wear visible with the naked eye. Case 2 was a metal-on-polyethylene THR with CoCrMo stem that exhibited visible corrosion damage of the head-neck junction. Case 3 was a dual modular metal-on-metal THR with moderate bearing surface wear and tribocorrosion damage on the modular components made from CoCrMo alloy and Ti-alloy. The details of manufacturer and design of retrieved implants are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of retrieved implants corresponding to the analysis periprosthetic tissue samples

| Case No. | Implant Manufacturer | Implant Components and Design | Time in situ (years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DePuy | THA with 28mm CoCrMo head, Marathon highly crosslinked PE liner | 14 |

| 2 | Zimmer Biomet | Dual mobility THA with 36mm CoCrMo head, Continuum Cluster-holed, highly crosslinked PE liner | 8 |

| 3 | Wright Medical Technology | THA with Profemur Plasma Z with Ti6Al4V stem, CoCrMo neck, 55mm CoCrMo head with Ti6Al4V adapter sleeve, Conserve Spiked CoCrMo cup | 6 |

Note: Stem in Case 1 & 2 were not revised during surgery thus no information available.

Assessment of wear and corrosion damage

The implant components were visually examined for wear and corrosion using a digital microscope (VHX-6000, Keyence). Wear of articulating surfaces (Cases 1 and 3), and corrosion damage to taper surfaces (Cases 2 and 3) were quantified with an optical 3D profiler (OrthoLux, RedLux) with white light chromatic confocal sensor50,51. Articulating surfaces were measured with 1080 data points per rotation and 3 rotations per degree. Taper surfaces were measured with 2 data points per degree and 70 rotations per millimeter. The head taper surfaces were measured by first making a replica with high precision molding material ((Microset Blue, Microset)52. Surface damage features were further analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (JSM-IT500HR, JEOL), if needed.

Tissue Sample preparations

The retrieved pseudo-capsule tissue samples from all three cases were first formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded in a tissue cassette. Three serial, 5-μm sections from each tissue block were made. One section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological evaluation of the tissue response. The second section was placed on a carbon disc, deparaffinized with xylene, and analyzed in a SEM coupled with EDS (Ultim Max, Oxford Instruments). EDS maps illustrated the elemental distribution of different metals within debris-laden macrophages. The third section was placed on separate barium fluoride (BaF2) disc, which is transparent to mid-range IR. The sample was then deparaffinized with xylene and rinsed by 100% ethanol for further FTIR-I analysis.

FTIR-I analysis

FTIR-I hyperspectral data were collected with an Agilent Cary 670 spectrometer coupled with a Cary 620 FTIR microscope equipped with a 128×128 mercury-cadmium-telluride focal plane array (FPA) detector. Transmission mode was used with both standard configuration (×15, projected pixel size: ~5.5 μm) and a high-magnification configuration (×75, projected pixel size: ~1.1 μm). The motorized sample stage allowed us to probe a large sample domain through sequentially stitching individual frames together. For each frame, 64 averaged interferograms per pixel were collected at a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1, and ratioed against with a 128 co-added reference background spectra per pixel. All spectra ranged from 3750–900 cm−1 and were exported to CytoSpec V2.0.06 where data processing was performed. The datasets were denoised using principal component analysis (PCA) based noise reduction with the first 30 PCs included49. Finally, data were vector normalized within the spectral range. For cell identification, additional second derivative of the spectrum were required, and calculated with 11 smoothing points (i.e., Savitzky-Golay algorithm). Selected wavenumbers were chosen for univariate imaging in a heat map fashion. The agglomerative hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) was also performed with D-Values (based on Pearson’s correlation coefficient) and Ward’s clustering method in the “fingerprint region” (1800–900 cm−1). Hyperspectral data sets were then reconstructed into pseudo-color maps based on cluster assignments. The color annotations were compared and validated to corresponding tissue sections stained by H&E. Single spectra were extracted from corresponding classified pixels for comparison.

Results

Case 1.

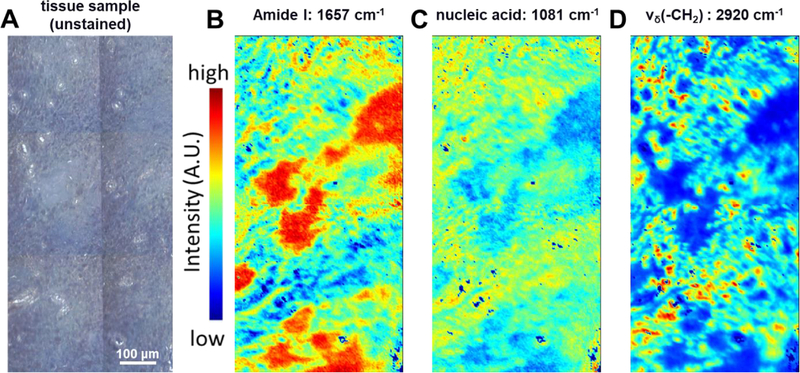

The patient was revised for pain, wear and periacetabular osteolysis identified by CT scan 14 years following a primary cementless total hip replacement performed with a 5 megarad highly crosslinked polyethylene liner and a 28mm ceramic head. The polyethylene liner exhibited a clear wear scar dominated by polishing within the articulating area. There also appeared to be rim contact at the inferior portion of the cup leading to local plastic deformation of the rim (Figure 1, Case 1). The wear volume was 313 mm3, corresponding to a wear rate of 22.01 mm3/year. There was no significant damage on either the metal head or the modular taper junction. The retrieved pseudocapsule sample consisted of dense fibro-connective tissue. Portions of the synovial lining were replaced by an organizing fibrin exudate containing macrophages. Other portions of the lining were largely intact. The dominant feature of the tissue was a marked macrophage response (Figure 2 A&B). The pseudocapsule was entirely infiltrated with large, slate-blue colored particle-laden macrophages (Figure 2 C&D). Macrophages were also seen infiltrating a portion of muscle that was attached to the pseudo-capsule. Foreign body giant cells were present in limited areas of the tissue. No obvious metallic particles were observed within macrophages. Collagenous tissue was highlighted through the univariate heat map showing intensity of amide I band (Figure 3 B). Further, FTIR-I analysis confirmed many of the macrophages contained an accumulation of fine polyethylene (PE) debris (Figure 3 C&D) that was clearly identifiable by characteristic PE peaks near the 2920 cm−1 (i.e., -CH2 asymmetric stretching) wavenumber53. The colocalization of PE signal with cell populated areas was clearly observed.

Figure 1.

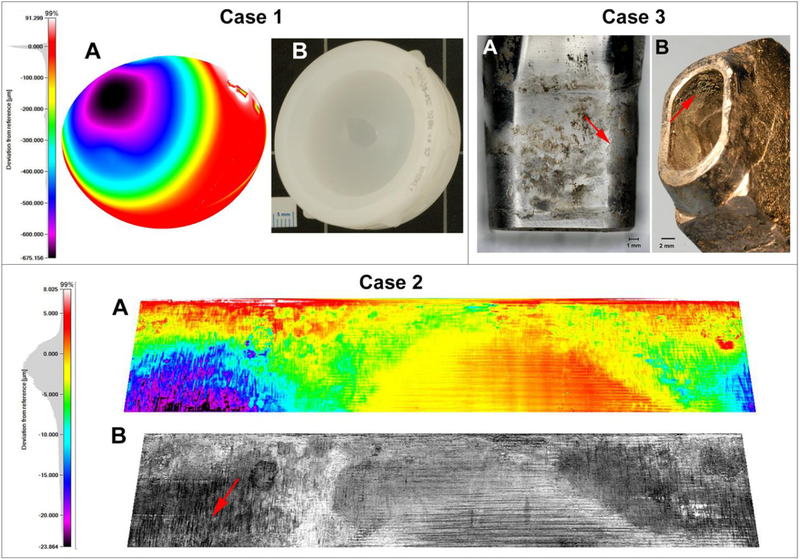

Implant damage characterization for three retrieved cases. Case 1: The surface of the polyethylene liner of Case 1 was measured with an optical CMM. A sphere was fitted to unworn regions to visualize and quantify polyethylene wear. A) Heat maps of the articulating surface in the side view illustrates a prominent wear scar with a maximum penetration of −675μm and that yielded a total material loss of 313 mm3. B) The light microscope image of the retrieved PE liner. Case 2: The head taper surface of the CoCrMo femoral head of Case 2 was reconstructed using CMM measurements of a high precision replica. A) The heat map illustrates areas with severe fretting and corrosion damage. The areas of largest material loss (purple and black) were characterized by severe column damage, which is best seen in the light intensity map (B, red arrow). Case 3: Photos of the severely worn and corroded A) male taper of the modular neck component and B) the female taper of the Ti6Al4V alloy stem component. In A) several areas of corrosion damage, deposits, and fretting marks (red arrow) can be seen. The female taper surface in B) mostly exhibited a damage pattern indicating surface fatigue caused by fretting and thick deposits (red arrow).

Figure 2.

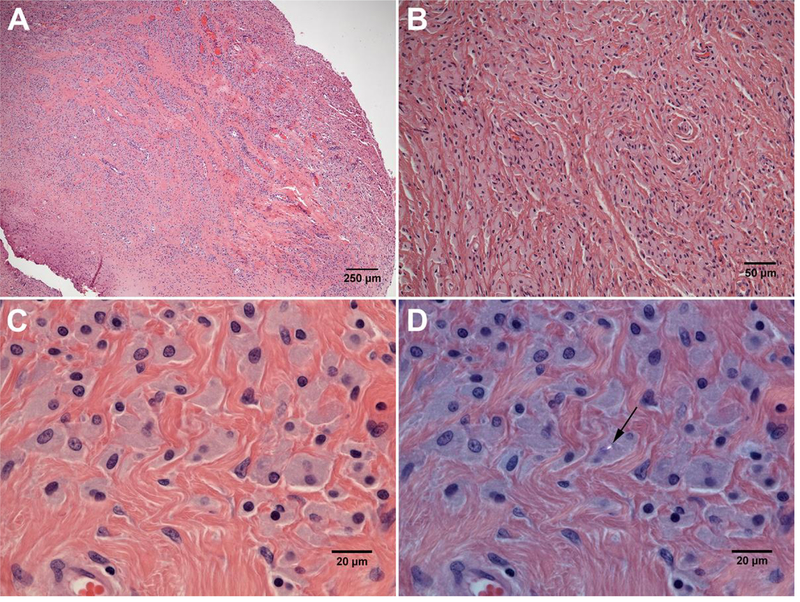

A&B: Low and high magnification of the joint pseudocapsule from Case 1 demonstrating the marked macrophage response dominating the tissue (H&E; A: ×40; B: × 200). C&D: Slate-blue colored particle-laden macrophages containing fine PE particles (×600, C: H&E; D: polarized light). It is worth mentioning that only one PE particle (black arrow) was visibly detected in this region under polarized light.

Figure 3.

Detection of fine polyethylene wear particles accumulated within macrophages of Case 1 using the univariate FTIR-I. A) Light micrograph of the unstained pseudo-capsule tissue sample adjacent to that shown in Fig. 2, B) The heat map of the sample imaged at 1657 cm−1 (i.e., Amide I group) presented a distribution of collagenous tissue, and C) The cell populated area can be highlighted using IR signal of phosphodiester linkage in nucleic acid at 1081 cm−1 wavenumber. D) Near 2920 cm−1 wavenumber, which νδ(-CH2) presents a strong stretching mode, fine polyethylene debris can be observed as an accumulation inside particle-laden macrophages. Colocalization of cell populated areas, as indicated by the presence of nucleic acid (Fig. 3C), and polyethylene debris, as shown by the strong polyethylene absorbance signal (Fig. 3D), is evident.

Case 2.

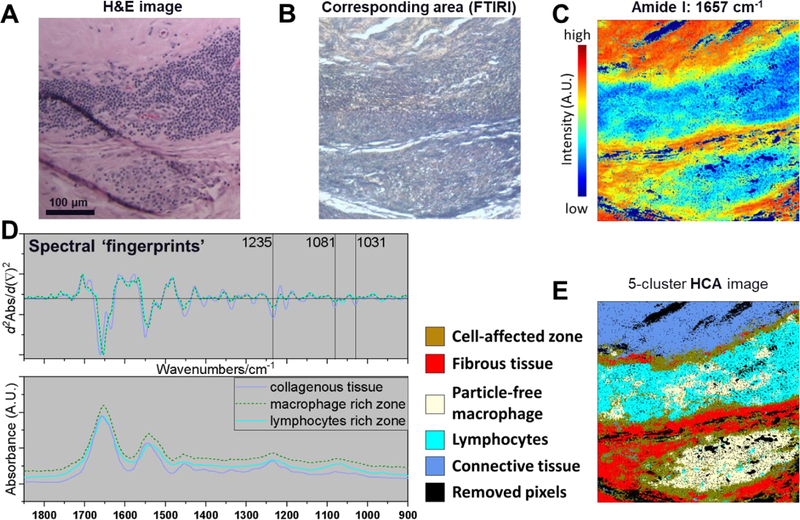

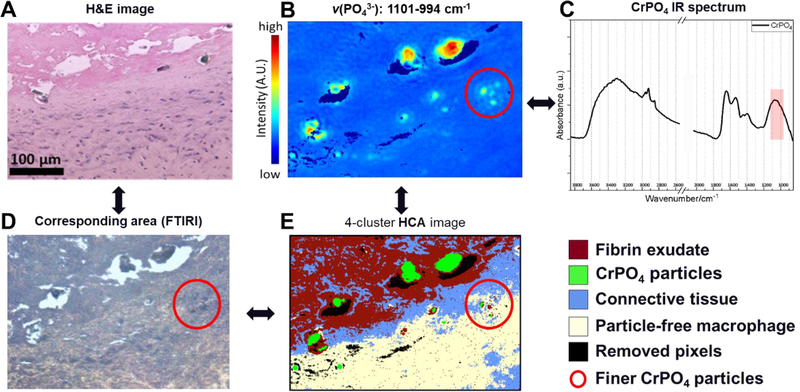

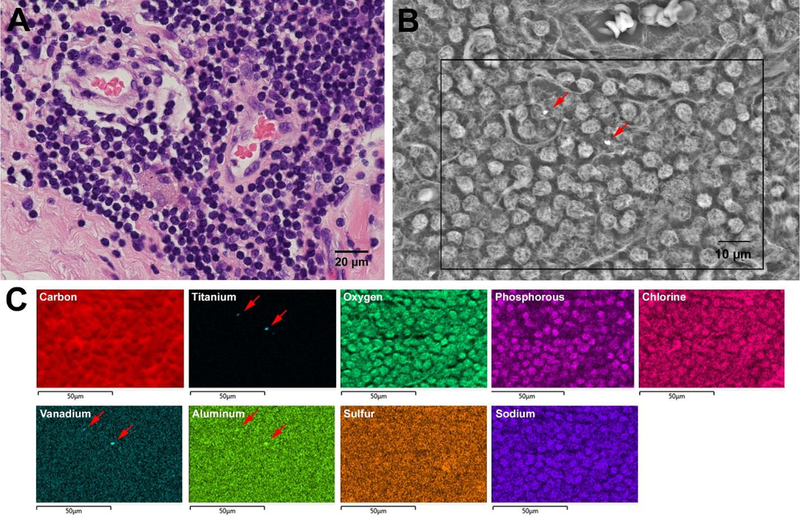

This was a patient revised for a loose acetabular component six years following a cementless total hip arthroplasty that included a modular dual mobility bearing. The dual mobility bearing surface exhibited no quantifiable damage. However severe corrosion of the taper surface of the CoCrMo femoral head was observed and CrPO4 debris was identified by SEM/EDS around the distal end of the taper. The material loss from the head taper was 1.35 mm3 (Figure 1, Case 2). The femoral stem was not available for analysis. The pseudocapsule tissue exhibited a strong presence of lymphocytes and macrophages (Figure 4 A&B). Univariate FTIR-I at an integrated intensity ranges from 1680–1620 cm−1 illustrated the distribution of amide I (mainly C=O stretching) which is indicative of collagenous tissue and is directly related to protein backbone conformation (Figure 4 C). Areas low in amide I corresponded to areas populated by cells. Second derivatives spectra at the “fingerprint region” (1750–900 cm−1) were plotted in comparison with their original spectra to show subtle spectral features of lymphocyte, macrophage, and collagenous tissue (Figure 4 D). The resulted derivative dataset was then used to conduct unsupervised multivariate HCA. The reconstructed image provided 5-color coded clusters representing different cell types or tissue structures (Figure 4 E). Here, HCA was able to distinguish the marked presence of macrophages and lymphocytes based on the infrared response, even in areas where both occurred intermixed. The tissue in direct proximity to areas dominated by a dense cell presence had a mixed spectrum owing to the absorbance of some isolated cells and the surrounding collagenous structure. Case 2 also exhibited multiple glassy, green particles which can typically be observed around THRs that underwent taper corrosion (Figure 5 A&D)38. FTIR-I data were acquired using the high-magnification scanning mode. Univariate image in the phosphate region (ν(PO43−): 1101–994 cm−1) revealed the particle location and the extracted spectrum confirmed its chemical structure as CrPO4 (Figure 5 B&C). The HCA image illustrated large CrPO4 particles, embedded within fibrin exudate rich areas, collagenous tissue without inflammatory cells, and a nearby area with a strong macrophage presence and even some finer CrPO4 (Figure 5 E). Neither SEM/EDS nor FTIR-I analysis showed a significant implant alloy particle presence of any kind within macrophages (Figure 6).

Figure 4.

A) H&E and B) light microscopic image showing strong presence of lymphocytes and macrophages in Case 2. C) an integrated intensity near 1657 cm−1 illustrates the distribution of amide I. D) The subtle difference in infrared spectra were better presented using their corresponding 2nd derivative plots as spectral fingerprints. Here, macrophages, lymphocytes, and collagenous tissue could be distinguished based on the infrared response using corresponding 2nd derivative spectrum. E) 5-color coded HCA image provides clusters representing different cell types or differences in the chemical structure of tissue, which can be validated through H&E image.

Figure 5.

Capsule tissue from Case 2 with severe taper corrosion. Multiple large, glassy, green particles are observed within the fibrin exudate and at the tissue surface (A: H&E image, and D: light microscopic image on corresponding sample area). B) Univariate FTIR-I showed a strong absorbance in the phosphate region (ν(PO43−): 1101–994 cm−1), and C) extracted spectrum confirmed the chemical structure as CrPO4. E) HCA reconstructed image with classified composition was able to visualize large CrPO4 particles, embedded within fibrin exudate-rich areas adjacent to collagenous tissue without inflammatory cells, and a nearby area with a strong macrophage presence. Some finer CrPO4 particles (red-circle) have also been detected due to the high spatial resolution (~1.1 micron) using the high-magnification scanning mode.

Figure 6.

A) Accumulation of lymphocytes and macrophages observed within the pseudocapsule tissue of Case 2 (H&E). B) Two particles are highlighted (red arrows) within this backscatter electron SEM image of an adjacent section from A). C) EDS mapping of a subsection of B) shows that that those two particles (red arrows) consisted of TiAlV alloy. However, overall, there were no other implant alloy metals found confirming a very low particle burden, despite severe corrosion of the modular junction.

Case 3.

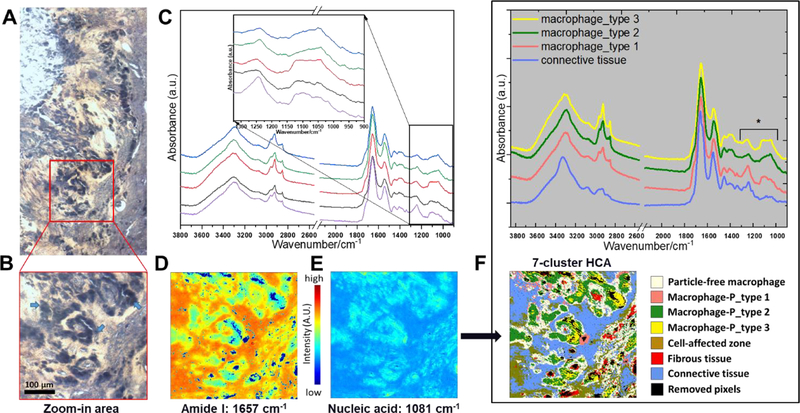

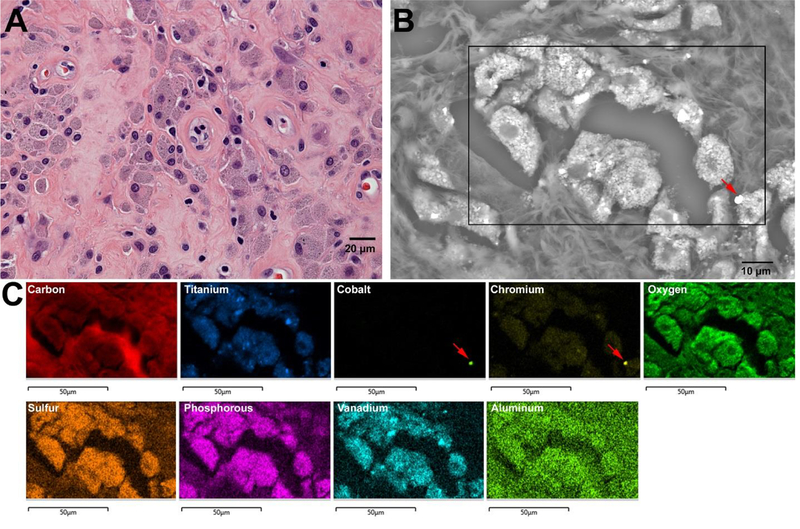

This patient was revised for pain secondary to an adverse local tissue reaction. The patient had a metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty performed 10 years earlier with a monoblock metal-on-metal acetabular component and a modular neck cementless stem. The bearing surface exhibited moderate wear of the articulating surfaces with a wear volume of 17 and 9.5 mm3 for the head and cup, respectively. The CoCrMo femoral head was attached via a Ti6Al4V alloy sleeve to a CoCrMo modular neck taper. Damage on the head taper and the outer sleeve taper was minimal (not quantifiable). The inner sleeve exhibited mild fretting damage with a material loss of 0.26 mm3. The neck taper exhibited minimal material loss of 0.07mm3. Damage of the oblong male taper of the modular neck component and the corresponding female component of the Ti6Al4V stem could not be accurately quantified with the CMM. However, severe damage was observed on both taper surfaces which exhibited damage features consistent with fretting wear (surface fatigue), fretting corrosion, plastic deformation, and wear/corrosion debris deposits (Figure 1, Case 3). The retrieved capsule tissue from Case 3 had a severe macrophage presence indicative of a strong foreign body reaction (Figure 7 A&B, Figure 8 A&B). Univariate FTIR-I showed both collagenous tissue and cell populated areas (Figure 7 D&E). Interestingly, initial exploring on the spectra features related to the location of macrophages using single point scan revealed subtle differences in the 1300–985 cm−1 spectral range, and five randomly chosen macrophage spectra were presented (Figure 7 C). Three distinctively different macrophage signal types averaged from each cluster were further distinguished by a 7-cluster HCA. Qualitatively, type 1 showed a sharp peak at 1300–1180 cm−1, which is often associated with amide III. This feature was not observed in type 2 or 3 macrophages. Additionally, a down trend slope at 1150–985 cm−1 for type 1, an upward trend slope for type 2, and a horizontal plateau at the peak for type 3 can be easily appreciated (Figure 7F, top). This region is often related to nucleic acid, phosphate, and some carbohydrates vibrations54,55. All three signal types differed from the infrared spectra of PE particle laden macrophages observed in Case 1, and non-particle laden macrophages seen in Case 2. The resulted spectra of each type of particle-laden macrophages together with connective tissue were extracted and plotted (Figure 7 F, bottom). Analysis of the corresponding SEM sample revealed that macrophages were laden with a broad mixture of particles indicative of CoCrMo alloy, Cr-oxide, Cr-phosphates, Ti-oxide, and TiAlV alloy (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

A) Light microscope image of the unstained tissue retrieved from Case 3. A marked macrophage presence (dark areas) is indicative of the foreign body reaction to wear debris. B) The zoom-in light microscope image from area A) was selected for FTIR-I analysis (arrows indicate macrophages). C) Using single point scan to probe randomly selected individual macrophages yielded five spectra with subtle spectral variance in in the 1300–985 cm−1 spectral range (inset). D) and E) Univariate images can provide a heat map for collagenous tissue and cell populated areas. F) The clustering results from HCA showed 3 different clusters of particle-laden macrophages. The averaged spectrum of individual clusters is plotted. The highlighted spectral features (asterisk) could potentially depend on the composition of foreign body or mixtures of foreign bodies that were internalized by the cells.

Figure 8.

A) Accumulation of particle-laden macrophages within pseudocapsule tissue of Case 3. B) Numerous metal particles can be seen within the macrophages, due to bright contrast in the backscatter electron SEM image of a tissue section adjacent to A). C) EDS mapping reveals that macrophages are packed with titanium and chromium, as well as several TiAlV alloy particles, and one CoCr alloy particle (red arrow). Two possible explanations for the strong presence of chromium, and overall low presence of cobalt could be either that CoCrMo particle are digested during phagocytosis and only chromium oxides remain, or that particles generated at the articulation or during fretting of the modular junction are already primarily consisting of chromium oxide.

Discussion

It was the purpose of this study to apply univariate and multivariate FTIR-I analysis for the characterization of wear and tribocorrosion debris from total hip replacements. The results demonstrated the advantages of both approaches in the direct detection of fine polyethylene wear debris and corrosion products, but also the ability of a simultaneous assessment of chemical alterations within the surrounding tissue and cell types.

Case 1 demonstrated that the univariate approach is able to identify PE wear debris and to localize it relative to macrophages or other tissue features. In general, FTIR-I is an ideal tool for the characterization of different polymers due to distinct IR signals associated with specific functional groups. We previously demonstrated that IR can, for example, distinguish different types of suture from PE debris within periprosthetic tissue39. Here, we have shown that the univariate approach even allows for the detection of an accumulation of PE particles that are too small to be detected by polarized light microscopy. The vast majority of contemporary THR acetabular liners are made from highly cross-linked UHMWPE. In general, these components are undergoing lower wear rates and producing finer wear debris than those made from conventional UHMWPE and its former versions (e.g. sterilized in air), making PE debris within the tissues much more difficult to track with common methods56,57. The improvement in wear performance appears to have resulted in the reduction of osteolysis-related failures. At this point in time, the clinical performance of these components is satisfactory, beyond twenty years in vivo, but it remains unclear if osteolysis is only delayed, occurring at a later point. Even though the case reported here was revised due to osteolysis among other reasons, the observed macrophage response was not yet comparable to that usually associated with osteolysis—even after 14 years in vivo. The relatively high PE wear rate of this component is consistent with the severe macrophage response, but it remains unclear if and when other histopathological features—such as the abundance of foreign body giant cells and granulomas—would have occurred had this implant been in situ for an even longer period of time. However, the univariate FTIR-I approach was proven to be a valuable tool—complimentary to common histopathological methods—that will help to monitor the tissue response to highly crosslinked PE debris over time in larger retrieval cohorts, as more cases of failed contemporary implants with liners made from cross-linked PE (or even its vitamin-E doped version) become available. It should be noted that gross wear of cross-linked PE liners as observed here is to our knowledge a rare observation and may be related to the early generation of cross-linked PE used in this implant.

Case 2 demonstrated the ability of both univariate and multivariate FTIR-I to detect CrPO4 particles—a prominent tribocorrosion product stemming from THA taper corrosion38,40–42. The occurrence of CrPO4 particles aligned with the observed severe corrosion damage of the modular head/stem junction; specifically, the notable material loss from the CoCrMo head taper. An elevated number of macrophages did occur along with a strong lymphocyte presence; however, the histiocytes did not appear to be particle-laden as detectable with polarized light microscopy, SEM or FTIR-I. The absence of notable PE debris or metal alloy wear debris corresponded well to the mild damage observed on the articulating surfaces. It is therefore possible that the strong lymphocyte response is triggered by metal ion release from the modular junction and not due to particulate debris. The multivariate FTIR-I approach provided valuable information on the chemical alterations within pseudocapsule tissue, specifically its localized inflammatory response to foreign bodies. The infrared spectrum of any cell is dominated by protein signals, but also contains information on nucleic acids (mostly RNA), lipids, and carbohydrates54. The process of taking second derivatives reduces the half width of the spectral peaks, and thus increases the sensitivity towards detecting shoulders or secondary peaks that may not be apparent in the raw spectra. Thus, areas occupied by lymphocytes and macrophages can be easily distinguished providing a fast tissue screening method. Additionally, characteristic histopathological patterns—such as fibrin exudate or necrotic tissue—can be identified and even quantified.

Additional strengths of FTIR-I with multivariate approach were on display in the analysis of Case 3. Unlike the previous two cases, this implant exhibited multiple sources and different types of implant debris, including metal ion generation. Our analysis confirmed bearing surface wear (fine Cr-oxide particles, cobalt -rich particles)20,58, corrosion of the CoCrMo taper junctions (Cr-oxides and -phosphate flakes)38,59 and fretting of Ti-alloy dual modular tapers (Ti-oxides, Ti alloy particles)51. However, with the exception of CrPO4, none of these types of debris can be directly detected by FTIR-I. Metal alloys are entirely composed of metallic bonds and therefore do not yield any IR response, and prominent IR peaks associated with Ti oxides and Cr oxides lie at lower wavenumbers (<850 cm−1), outside of the detectable range of the FPA, owing to the intrinsic band gap, of the spectrometer used in this study. Yet, a 7-cluster HCA yielded three distinctively different IR signatures of macrophages within the IR wavenumber range associated with amide III and nucleic acid. These distinct spectral features were also confirmed by single point measurements on randomly chosen macrophages. The difference in peak shape and relative intensity can be associated with specific alterations of the macrophages’ chemical structure related to the type and amount of wear debris taken up by the cell. It is also possible that corrosion of intracellular alloy particles leads to metal ion release, especially Co2+, and gradual changes of the cell’s organelles and nucleus60, yielding IR spectral changes. Furthermore, the chemical degradation process of CoCrMo alloy may also leave behind CrPO4 which has an IR signature that partially overlaps with the signature peak of nucleic acid. A recent study has shown that macrophages challenged with CoCrMo alloy debris in the sub-micrometer range can cause a change in its cytokine and gene expression, indicating a change of phenotype61; potentially yielding a different chemical structure reflected in the IR signature. Lastly, changes in the cell’s chemical structure may also simply occur due to the gradual transition of the cell to the necrotic state; however, this process was also shown to be correlated with a red-shift of the amide I and II bands39 that was not observed here and is therefore less likely. The exact meaning of the observed spectral changes of macrophages in response to mixed metallic wear debris and corrosion products needs further investigation. Yet, these distinct spectral features linked to the macrophage response can likely be utilized as an indirect measure of the type and quantity of the implant debris that was generated in vivo. This will be particularly important for the numerous cases where routine sampling of periprosthetic tissue samples are sent for pathological examination during revision surgery, but implants are not retrieved.

Conclusions

From its beginning, one of the fundamental problems addressed by the research field of biotribology has been the generation of wear particles from orthopedic implants and their adverse effect on the periprosthetic tissue, and therefore the patient. As a result of biotribology research, the wear resistance of implant materials has improved greatly. However, new problems emerge, such as fretting corrosion at modular junctions. Even more importantly, the need for total joint replacements has increased, as have expectations of implant longevity and performance. Therefore, debris generated by wear and tribocorrosion processes will remain an important topic in biotribology for the foreseeable future. Here, we introduce a new tool, FTIR-I, for the localization and chemical characterization of implant debris within periprosthetic tissue. Univariate and multivariate FTIR-I can help by either detecting implant debris directly within tissue due to distinct peaks within the IR spectrum (e.g., polyethylene, suture, CrPO4) or indirectly (metal alloy debris and metal oxides), based on alterations of the chemical structure of the tissue and its present inflammatory cells. This approach allows for the simultaneous analysis of the chemical nature of implant debris and the corresponding tissue response. The authors acknowledge the limitation that FTIR-I by itself is not sufficient to study the cellular effects within periprosthetic tissue, but it provides additional valuable chemical information which fits well into the clinical diagnostic workflow. Besides the cases demonstrated here, these techniques will also prove valuable for the analysis of implant debris from newly emerging materials such as PEEK or hydrogels.

Highlights:

Use of FTIR-I for the direct identification of fine XLPE debris accumulation within macrophages.

Detection of chromium phosphate debris with periprosthetic tissue in case with modular junction fretting corrosion

Chemical characterization of histopathological patterns with FTIR-I through cell identification and biochemical alteration of periprosthetic tissue.

Assessment of the complex nature of implant debris generated from multiple sources through the characterization of particle-laden macrophages within periprosthetic tissue.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by NIH grant R01 AR070181. The authors would like to thank Stephanie M. McCarthy for her support in preparing tissue sections for this study.

Conflict of interest disclosure

Two authors have conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Craig Della Valle has the following disclosures: American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons (board or committee member), Arthritis foundation (board or committee member), DePuy (paid consultant), Knee Society (board or committee member), Orthopedics Today (Editorial or governing board), Orthophor and Surgiphor (stock or stock options), Parvizi Surgical Innovations (stock or stock options), SLACK incorporated (editorial or governing board, publishing royalties, financial or material support), Smith & Nephew (IP royalties, paid consultant, research support), Stryker (research support), Wolters Kluwer Health ‐ Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (publishing royalties, financial or material support), Zimmer (IP royalties, paid consultant, research support). Dr. Jacobs has the following disclosures: American Board of Orthopedic Surgery, Inc. (board or committee member), Hip Society (board or committee member), Hyalex (stock or stock options), Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery – American (Editorial or governing board, publishing royalties, financial or material support), Medtronic Sofamor Danek (research support), Nuvasive (research support), Orthopedic Research and Education Foundation (board or committee member, Zimmer (paid consultant, research support).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- 1.Dowson D Review Paper 2: Whither Tribology? Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Conf. Proc (1969). doi: 10.1243/PIME_CONF_1969_184_384_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dowson D Priorities for research on internal prosthesis. Biomaterials 1, 123–124 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dumbleton JH Tribology of Natural and Artificial Joints. (Elsevier, 1981). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher J & Dowson D Tribology of Total Artificial Joints. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. [H] 205, 73–79 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanbhag A, Jacobs J, Glant T, Gilbert J, Black J & Galante J Composition and morphology of wear debris in failed uncemented total hip replacement. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br 76-B, 60–67 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin ZM, Stone M, Ingham E & Fisher J (v) Biotribology. Curr. Orthop 20, 32–40 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Puccio F & Mattei L Biotribology of artificial hip joints. World J. Orthop 6, 77–94 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris WH The problem is osteolysis. Clin. Orthop 46–53 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kabo J, Gebhard J, Loren G & Amstutz H In vivo wear of polyethylene acetabular components. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br 75-B, 254–258 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs JJ, Roebuck KA, Archibeck M, Hallab NJ & Glant TT Osteolysis: basic science. Clin. Orthop 71–77 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaddick C, Catelas I, Pennekamp PH & Wimmer MA Implant wear and aseptic loosening. An overview. Orthop 38, 690–697 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallo J, Goodman SB, Konttinen YT, Wimmer MA & Holinka M Osteolysis around total knee arthroplasty: a review of pathogenetic mechanisms. Acta Biomater 9, 8046–8058 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bobyn JD, Jacobs JJ, Tanzer M, Urban RM, Aribindi R, Sumner DR, Turner TM & Brooks CE The Susceptibility of Smooth Implant Surfaces to Periimplant Fibrosis and Migration of Polyethylene Wear Debris. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res 311, 21–39 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.OONISHI H, KUNO M, TSUJI E & FUJISAWA A The optimum dose of gamma radiation–heavy doses to low wear polyethylene in total hip prostheses. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med 8, 11–18 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher J, Hu XQ, Tipper JL, Stewart TD, Williams S, Stone MH, Davies C, Hatto P, Bolton J, Riley M, Hardaker C, Isaac GH, Berry G & Ingham E An in vitro study of the reduction in wear of metal-on-metal hip prostheses using surface-engineered femoral heads. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. [H] 216, 219–230 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muratoglu OK, Mark A, Vittetoe DA, Harris WH & Rubash HE Polyethylene Damage in Total Knees and Use of Highly Crosslinked Polyethylene. JBJS 85, S7 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dennis DA & Komistek RD Mobile-bearing Total Knee Arthroplasty: Design Factors in Minimizing Wear. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res 452, 70–77 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmalzried TP, Jasty M, Rosenberg A & Harris WH Polyethylene wear debris and tissue reactions in knee as compared to hip replacement prostheses. J. Appl. Biomater 5, 185–190 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doorn PF, Campbell PA, Worrall J, Benya PD, McKellop HA & Amstutz HC Metal wear particle characterization from metal on metal total hip replacements: Transmission electron microscopy study of periprosthetic tissues and isolated particles. J. Biomed. Mater. Res 42, 103–111 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Catelas I, Campbell PA, Bobyn JD, Medley JB & Huk OL Wear particles from metal-on-metal total hip replacements: Effects of implant design and implantation time. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. [H] 220, 195–208 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galvin AL, Tipper JL, Jennings LM, Stone MH, Jin ZM, Ingham E & Fisher J Wear and biological activity of highly crosslinked polyethylene in the hip under low serum protein concentrations. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. [H] 221, 1–10 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edidin AA, Rimnac CM, Goldberg VM & Kurtz SM Mechanical behavior, wear surface morphology, and clinical performance of UHMWPE acetabular components after 10 years of implantation. Wear 250, 152–158 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bracco P & Oral E Vitamin E-stabilized UHMWPE for Total Joint Implants: A Review. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res 469, 2286–2293 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurtz SM, Gawel HA & Patel JD History and Systematic Review of Wear and Osteolysis Outcomes for First-generation Highly Crosslinked Polyethylene. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res 469, 2262–2277 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lachiewicz PF, Soileau ES & Martell JM Wear and Osteolysis of Highly Crosslinked Polyethylene at 10 to 14 Years: The Effect of Femoral Head Size. Clin. Orthop 474, 365–371 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown TS, Van Citters DW, Berry DJ & Abdel MP The use of highly crosslinked polyethylene in total knee arthroplasty. Bone Jt. J 99-B, 996–1002 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teeter MG, Yuan X, Somerville LE, MacDonald SJ, McCalden RW & Naudie DD Thirteen-year wear rate comparison of highly crosslinked and conventional polyethylene in total hip arthroplasty: long-term follow-up of a prospective randomized controlled trial. Can. J. Surg. J. Can. Chir 60, 212–216 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baxter RM, Ianuzzi A, Freeman TA, Kurtz SM & Steinbeck MJ Distinct immunohistomorphologic changes in periprosthetic hip tissues from historical and highly crosslinked UHMWPE implant retrievals. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 95A, 68–78 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kandahari AM, Yang X, Laroche KA, Dighe AS, Pan D & Cui Q A review of UHMWPE wear-induced osteolysis: the role for early detection of the immune response. Bone Res 4, 1–13 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farrar DF & Brain AA The microstructure of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene used in total joint replacements. Biomaterials 18, 1677–1685 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jillavenkatesa A, Lum L-SH & Dapkunas S NIST Recommended Practice Guide: Particle Size Characterization. (2001). at <https://www.nist.gov/publications/nist-recommended-practice-guide-particle-size-characterization>

- 32.Clayton RAE, Beggs I, Salter DM, Grant MH, Patton JT & Porter DE Inflammatory Pseudotumor Associated with Femoral Nerve Palsy Following Metal-on-Metal Resurfacing of the Hip. A Case Report. J. Bone Jt. Surg 90, 1988–1993 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper HJ, Della Valle CJ, Berger RA, Tetreault M, Paprosky WG, Sporer SM & Jacobs JJ Corrosion at the head-neck taper as a cause for adverse local tissue reactions after total hip arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am 94, 1655–1661 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper HJ, Urban RM, Wixson RI, Meneghini RM & Jacobs JJ Adverse Local Tissue Reactions Arising from Corrosion at the Neck-Body Junction in a Dual Taper Stem with a CoCr Modular Neck. J. Bone Jt. Surg. AM 95, 865–872 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hussey DK & McGrory BJ Ten-Year Cross-Sectional Study of Mechanically Assisted Crevice Corrosion in 1352 Consecutive Patients With Metal-on-Polyethylene Total Hip Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty 32, 2546–2551 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell P, Ebramzadeh E, Nelson S, Takamura K, Smet K & Amstutz HC Histological Features of Pseudotumor-like Tissues From Metal-on-Metal Hips. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res 468, 2321–2327 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huber M, Reinisch G, Trettenhahn G, Zweymuller K & Lintner F Presence of corrosion products and hypersensitivity-associated reactions in periprosthetic tissue after aseptic loosening of total hip replacements with metal bearing surfaces. Acta Biomater 5, 172–180 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hall DJ, Pourzal R, Della Valle CJ, Galante JO, Jacobs JJ & Urban RM in STP1591 ASTM Int 410–427 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu S, Hall DJ, McCarthy SM, Jacobs JJ, Urban RM & Pourzal R Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic imaging of wear and corrosion products within joint capsule tissue from total hip replacements patients. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater jbm.b.34408 (2019). doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.34408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Urban RM, Jacobs JJ, Gilbert JL & Galante JO Migration of corrosion products from modular hip prostheses. Particle microanalysis and histopathological findings. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am 76, 1345–1359 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Esposito CI, Wright TM, Goodman SB & Berry DJ What is the Trouble With Trunnions? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res 472, 3652–3658 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gibon E, Amanatullah DF, Loi F, Pajarinen J, Nabeshima A, Yao Z, Hamadouche M & Goodman SB The Biological Response to Orthopaedic Implants for Joint Replacement: Part I: Metals. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater 105, 2162–2173 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bird B, Miljković M, Remiszewski S, Akalin A, Kon M & Diem M Infrared spectral histopathology (SHP): a novel diagnostic tool for the accurate classification of lung cancer. Lab. Invest 92, 1358–1373 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bassan P, Sachdeva A, Shanks JH, Brown MD, Clarke NW & Gardner P Whole organ cross-section chemical imaging using label-free mega-mosaic FTIR microscopy. Analyst 138, 7066–7069 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leslie LS, Wrobel TP, Mayerich D, Bindra S, Emmadi R & Bhargava R High Definition Infrared Spectroscopic Imaging for Lymph Node Histopathology. PLOS ONE 10, e0127238 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Varma VK, Kajdacsy-Balla A, Akkina SK, Setty S & Walsh MJ A label-free approach by infrared spectroscopic imaging for interrogating the biochemistry of diabetic nephropathy progression. Kidney Int 89, 1153–1159 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martinez-Marin D, Sreedhar H, Walsh MJ & Picken MM Infrared spectroscopic imaging: a label free approach for the detection of amyloidosis in human tissue biopsies. Amyloid 24, 163–164 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lasch P Spectral pre-processing for biomedical vibrational spectroscopy and microspectroscopic imaging. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst 117, 100–114 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diem M Modern Vibrational Spectroscopy and Micro-Spectroscopy: Theory, Instrumentation and Biomedical Applications. (John Wiley & Sons, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Optical CMM | Accurate, 3D, Non-contact, Precision Metrology. RedLux at <https://www.redlux.net/opticalcmm>

- 51.Hall DJ, Pourzal R, Lundberg HJ, Mathew MT, Jacobs JJ & Urban RM Mechanical, chemical and biological damage modes within head-neck tapers of CoCrMo and Ti6Al4V contemporary hip replacements: DAMAGE MODES IN THR MODULAR JUNCTIONS. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater 106, 1672–1685 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cook RB, Maul C & Strickland AM in Modul. Tapers Total Jt. Replace. Devices (Greenwald AS, Lemons JE, Kurtz SM & Mihalko WH) 362–378 (ASTM International, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gulmine JV, Janissek PR, Heise HM & Akcelrud L Polyethylene characterization by FTIR. Polym. Test 21, 557–563 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Movasaghi Z, Rehman S & Rehman D. I. ur. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy of Biological Tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev 43, 134–179 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baker MJ, Trevisan J, Bassan P, Bhargava R, Butler HJ, Dorling KM, Fielden PR, Fogarty SW, Fullwood NJ, Heys KA, Hughes C, Lasch P, Martin-Hirsch PL, Obinaju B, Sockalingum GD, Sulé-Suso J, Strong RJ, Walsh MJ, Wood BR, Gardner P & Martin FL Using Fourier transform IR spectroscopy to analyze biological materials. Nat. Protoc 9, 1771–1791 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Illgen RL, Forsythe TM, Pike JW, Laurent MP & Blanchard CR Highly Crosslinked vs Conventional Polyethylene Particles—An In Vitro Comparison of Biologic Activities. J. Arthroplasty 23, 721–731 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iwakiri K, Minoda Y, Kobayashi A, Sugama R, Iwaki H, Inori F, Hashimoto Y, Ohashi H, Ohta Y, Fukunaga K & Takaoka K In vivo comparison of wear particles between highly crosslinked polyethylene and conventional polyethylene in the same design of total knee arthroplasties. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater 91, 799–804 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pourzal R, Catelas I, Theissmann R, Kaddick C & Fischer A Characterization of Wear Particles Generated from CoCrMo Alloy under Sliding Wear Conditions. Wear 271, 1658–1666 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.admin. Investigation of nano-sized debris released from CoCrMo secondary interfaces in total hip replacements: digestion of the flakes. GMC (2018). at <http://gmc.network/2018/06/14/investigation-of-nano-sized-debris-released-from-cocrmo-secondary-interfaces-in-total-hip-replacements-digestion-of-the-flakes/> [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gill HS, Grammatopoulos G, Adshead S, Tsialogiannis E & Tsiridis E Molecular and immune toxicity of CoCr nanoparticles in MoM hip arthroplasty. Trends Mol. Med 18, 145–155 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bijukumar DR, Salunkhe S, Zheng G, Barba M, Hall DJ, Pourzal R & Mathew MT Wear particles induce a new macrophage phenotype with the potential to accelerate material corrosion within total hip replacement interfaces. Acta Biomater 101, 586–597 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]