Abstract

Purpose:

Silicone oil (SO) is often used as an intraocular tamponade in repairs of retinal detachments. It may be associated with complications such as cataract, glaucoma, keratopathy, subretinal migration of oil, fibrous epiretinal and sub retinal proliferations, and oil emulsification. The purpose of this report is to describe a rare phenomenon of intraocular silicone oil migration into the cerebral ventricles, which may later be mistaken for intraventricular hemorrhages on neuroimaging.

Methods:

Case report with literature review.

Results:

A patient with a history of retinal detachment repair with intraocular SO presented with headaches. Neuroimaging revealed SO migration to the cerebral ventricles. The patient was treated conservatively with symptom management and headaches resolved.

Conclusions:

We present a case of intraocular SO migration to the cerebral ventricles and review the current literature. We also propose two mechanisms for this phenomenon.

Keywords: silicone oil, retinal detachment, complications of vitreoretinal surgery

Introduction

For decades, silicone oil (SO) has been used as an intraocular tamponade to repair retinal detachments. Known complications associated with this procedure include cataract, glaucoma, keratopathy, subretinal migration of the oil, fibrous epiretinal and subretinal proliferations, and emulsification of SO.1,2 Notably, reports of intravitreal SO migration into the cerebral ventricles have emerged. This rare complication was first described by Williams et al in a patient who developed a retinal detachment secondary to cytomegaloviral (CMV) retinitis.3 To our knowledge, 21 additional cases have since been reported in the literature.4-23 Additional studies have reported SO migration to the optic nerve. 22,24-30 Here we present a similar case of intravitreal SO migration into the lateral cerebral ventricles and propose potential mechanisms for how SO migrates upstream to this location via cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow from the optic nerves.

Case Report

A 77-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and end-stage renal disease presented to an outside hospital after developing headaches during hemodialysis. Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) imaging of the head revealed findings interpreted as intraventricular hemorrhage. The patient was subsequently transferred to the Keck Hospital of the University of Southern California. Upon arrival, the patient reported resolution of her headache. She vaguely recalled a distant history of retina surgery for retinal detachment in her left eye, complicated by glaucoma and resulting in blindness for many years. She denied any interventions for her right eye.

On examination, the patient’s visual acuity was no light perception bilaterally. Intraocular pressure (IOP) was 60 mm Hg in the right eye and 20 mm Hg in the left eye. Extraocular movements were intact, without focal neurological deficits. Slit-lamp examination revealed visually significant cataracts bilaterally, precluding an adequate view of the fundus on dilated fundoscopic exam; however, B-scan ultrasonography revealed no posterior segment pathology, although this was limited by SO.

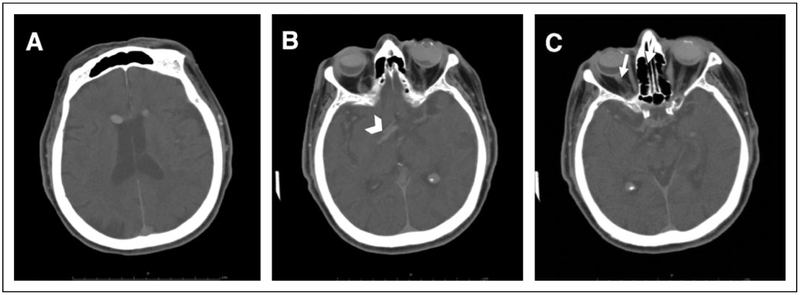

A noncontrast CT scan of the head was repeated at our institution, with the patient in the supine position, demonstrating 2 subcentimeter hyperattenuating lesions bilaterally within the frontal horns of the lateral ventricles (Figure 1A). Aradiologically similar lesion was identified in the left anterior aspect of the suprasellar cistern (Figure 1B). These substances were noted to be floating in non-dependent, or uppermost, region of the fluid-filled cavity. Relative hyperattenuation was also detected along the right optic sheath, leading the radiologist to speculate that this may be a possible conduit of SO migration (Figure 1C). The right eye was half full of SO and the left eye was 80% to 90% full (Figure 1C). There was no evidence of intracranial hemorrhage.

Figure 1.

The right eye is half full of silicone oil, while the left eye is 80% to 90% full. Axial noncontrast computed tomography of the head shows (A) bilateral hyperdense bodies in the frontal horns of the lateral ventricles, (B) a hyperattenuating body in the left anterior aspect of the suprasellar cistern (arrowhead), and (C) relative hyperlucency along the right optic sheath (arrow).

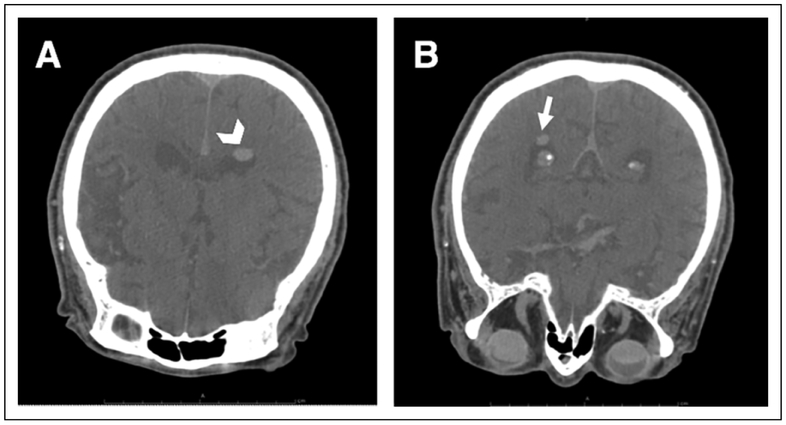

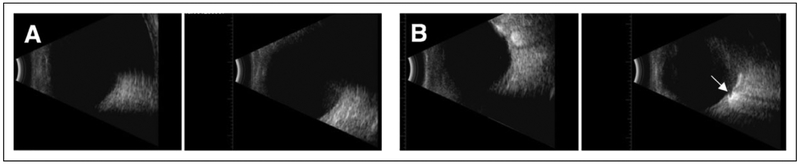

The following day, a CT head scan was performed with the patient in prone position, which showed shifting of the previously noted lesions to the atria of both lateral ventricles (Figures 2A and 2B). Findings were most consistent with intraventricular SO, presumably from an ocular source. Additional B-scan imaging with the patient in the upright position demonstrated the right eye filled halfway with material consistent with SO. The images also suggested profound optic disc cupping in the right eye. A B-scan of the left eye revealed a distorted image that was also consistent with SO (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Axial noncontrast head computed tomography scan with the patient in prone position. Hyperlucent bodies previously in the anterior horns have moved dorsally to (A) the left atrium of the lateral ventricle (arrowhead) as well as (B) the right atrium (arrow).

Figure 3.

B-scan ultrasonography. (A) The right eye with a half volume of silicone oil shows normal echogenicity of the lower half of the eye in the vertical axial scan, and delayed echogenicity with posteriorly displaced retinal image in the upper half of the eye. (B) B-scan of the left eye demonstrates profound optic nerve cupping (arrow).

Given that the patient’s headache had resolved and there were no acute changes in her vision or reported eye pain, we advised the patient to follow up with her existing outpatient ophthalmologist.

Discussion

Theories on Pathophysiologic Mechanism of Migration

The migration of intraocular SO into the ventricles is a rare but recognized complication of SO endotamponade for retinal detachment repair. To our knowledge, only 22 cases have been previously reported.3-23 Of these cases, 11 patients also had an ocular history of diabetic retinopathy, 2 had CMV retinitis, and 1 had a history of uveitis (Table 1). The others were presumed to have had retinal detachment uncomplicated by other intraocular disease. Nine cases reported an increase in IOP after SO endotamponade, and SO was found in the lateral ventricles in all 22 cases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reported Cases of Intraocular Silicone Oil Migration to the Ventricles.

| Author | Age/ Sex |

MH | Reason for Imaging |

↑IOP | Optic Atrophy |

Location of Migrated SO |

Time From RD Surgery to Presentation |

Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chang et al4 | 58/F | DR, RD | Headache, dizziness | NR | NR | L optic nerve, R lateral ventricle, R fourth ventricle | 10 y | Symptomatic, follow-up | NR |

| Jabbour et al5 | 72/M | DR, RD | Fall, headache | NR | NR | R suprasellar cistern, frontal horns of lateral ventricles | 15 y | Follow-up | Symptoms resolved spontaneously |

| Hruby et al6 | 51/M | DR, RD | Headache, neck stiffness | Yes | NR | Frontal horns of lateral ventricles, third ventricle | 5 y | Ventriculoperitoneal shunt | Symptoms resolved after shunt |

| Tatewaki et al7 | 66/F | DR, RD | Headache, lower extremity weakness | NR | NR | R frontal horn of lateral ventricle | NR | Symptomatic | Symptoms improved |

| Kuhn et al8 | 15/F | Cystoid macular edema, RD | Headache | Yes | +optic pits bilaterally | Optic chiasm, L optic tract, frontal horns of lateral ventricles | 6 y | Symptomatic | IOP controlled |

| Eller et al9 | 42/M | CMV retinitis, RD | Peripheral neuropathy | Yes | Yes | L optic nerve, frontal horns of lateral ventricles | 6.5 mo | Symptomatic, follow-up | No symptoms attributable to SO |

| Yu and Apte10 | 47/M | DR, RD | Altered mental status | Yes | Yes | Frontal horns of lateral ventricles | 1 y | Symptomatic, follow-up | NR; death secondary to cardiac arrest |

| Fangtian et al11 | 62/F | DR, RD | Dizziness | Yes | Yes | Suprasellar cistern, R frontal horn of lateral ventricle, third/fourth ventricles | 8 mo | Symptomatic, follow-up | NR |

| Cosgrove et al12 | 74/F | RD | Headache | NR | NR | L optic nerve, R frontal horn of lateral ventricle, suprasellar cistern | 20 y | Symptomatic, follow-up | Symptoms resolved spontaneously |

| Chen et al13 | 39/M | DR, RD | Fall, headache, nausea | NR | NR | L optic nerve, L optic chiasm, frontal horns of lateral ventricles | NR | NR | NR |

| Campbell et al14 | 40/M | NR | Seizures | NR | NR | L frontal horn of lateral ventricle | NR | NR | NR |

| Chiao et al15 | 80/F | NR | Fall, concussion | NR | NR | L optic nerve, optic chiasm, L optic radiation, frontal horns of lateral ventricles | NR | NR | NR |

| Williams et al3 | 42/M | CMV retinitis, RD | Peripheral neuropathy | Yes | Yes | Frontal horns of lateral ventricles, L optic nerve | 15 mo | NR | NR |

| Potts et al16 | 56/F | DR, RD | Headache, facial paresthesia, hypertension | NR | NR | Frontal horns of lateral ventricles, L optic nerve, optic chiasm | 9 y | Symptomatic, follow-up | Symptoms resolved with treatment of hypertension |

| Mathis et al17 | 82/F | RD, atrial fibrillation | Sudden L hemiparesia | Yes | NR | Frontal horns of lateral ventricles, L optic nerve | 38 mo | NR | NR |

| Dababneh et al18 | 73/F | DR, RD | Dizziness, headache, syncope | NR | NR | L temporal horn and R frontal horn of lateral ventricle, 4th ventricle | 25 y | NR | NR |

| Swami et al19 | 68/M | DR, RD | Fever, urinary incontinence, delusions | NR | NR | Third ventricle near foramen of Monro, frontal horns of lateral ventricles | 9-10 y | Treatment of urinary tract infection | Symptoms resolved with treatment of urinary tract infection |

| Filippidis et al20 | 67/F | RD | Headache | NR | NR | Frontal horns of lateral ventricles | 6 y | NR | NR |

| Boren et al21 Case 1 | 82/F | RD | Confusion | Yes | NR | Frontal horns of lateral ventricles, R temporal horn of lateral ventricle | 9 y | NR | NR |

| Boren et al21 Case 2 | 42/M | DR, RD | Painless vision loss, vitreous hemorrhage | Yes | NR | L optic nerve, chiasm, lateral ventricles | 16 mo | NR | NR |

| Cebula et al22 | NR | RD, uveitis | Headache | NR | NR | L optic nerve, chiasm, L frontal horn of lateral ventricle | NR | Symptomatic | Symptoms resolved |

| Gnanalingham et al23 | 84/F | RD, glaucoma | Head trauma after fall | NR | NR | Frontal horns of lateral ventricles, L optic nerve, chiasm | 1 y | Symptomatic | Patient died from unrelated complications |

Abbreviations: CMV, cytomegalovirus; DR, diabetic retinopathy; F, female; IOP, intraocular pressure; L, left; M, male; MH, medical history; NR, not reported; R, right; RD, retinal detachment; SO, silicone oil.

To date, no consensus has been reached on the precise mechanism of SO migration. There is no known anatomic communication between the vitreous space and the intracranial subarachnoid space, yet SO does travel to the lateral ventricle. Several hypotheses have been postulated.

The first theory was proposed in 1989 by Shields and Eagle30 when they identified oil globules forming cavernous spaces within the parenchyma of an optic nerve from an enucleated eye. This eye notably had increased IOP and a deeply cupped optic disc. That finding led them to hypothesize that the mechanism was similar to that of Schnabel cavernous degeneration, with SO rather than vitreous fluid migrating through the lamina cribrosa into the optic nerve secondary to prolonged IOP elevation.30 The SO is then thought to travel to the perioptic subarachnoid space before migrating to the ventricular system.

Two radiologic studies have provided direct support of this theory.4,7 In 2011, Tatewaki et al7 used a silicone-selective imaging technique to visualize SO in their patient’s left globe, lateral ventricle, and the entire length of the left optic nerve, suggesting that intraocular SO spreads via the perioptic subarachnoid space. In 2013, Chang et al4 demonstrated through serial imaging active migration of SO from the vitreous, to the perioptic subarachnoid space, and finally to the ventricles. Since then, other histopathological and imaging studies have corroborated Shields and Eagle’s theory.3,5,6,9,10,12,14,27-29

A less prominent but plausible theory suggests direct migration from the subretinal space to the subarachnoid space. Kuhn et al8 examined a patient with bilateral congenital optic pits and suggested that there was communication between the subarachnoid space and subretinal space. The notion of this communication is supported by a report summarizing 4 cases of patients with optic pit anomalies, such as colobomas or optic pit.31 The report theorized that defects in tissue overlying optic disc anomalies provide a connection between the vitreous cavity, subretinal space, and subarachnoid space.31 Each of these theories seeks to explain the migration of SO into the CSF compartment. The question remains as to how this material reaches the lateral ventricles, given that there is no direct anatomical connection between the optic nerve sheaths and the intraventricular space.

A third theory, proposed in 2004 by Papp et al,28 suggested that silicone-filled macrophages actively transport SO from the vitreous cavity to the subarachnoid space. Their histopathologic study identified CD68-positive macrophages at the border of vacuoles in the optic nerve, with these macrophages positive for SO. The findings partially support the idea that prolonged contact of SO with eye tissue leads to the mobilization of macrophages that phagocytose SO. This active phagocytosis hypothesis is supported by a study of 20 postmortem eyes without any known eye disease that were filled with SO for up to 16 weeks then examined under various methods of microscopy.32 The mean IOP in these eyes after they were filled with SO was 40 mm Hg. After 16 weeks, none of the eyes demonstrated SO in the retrolaminar portion of the optic nerve, which suggested that IOP alone seems unlikely to be the main pathophysiologic mechanism of SO transport, and either pre-existing glaucomatous disc damage or active transport mechanisms must be involved.

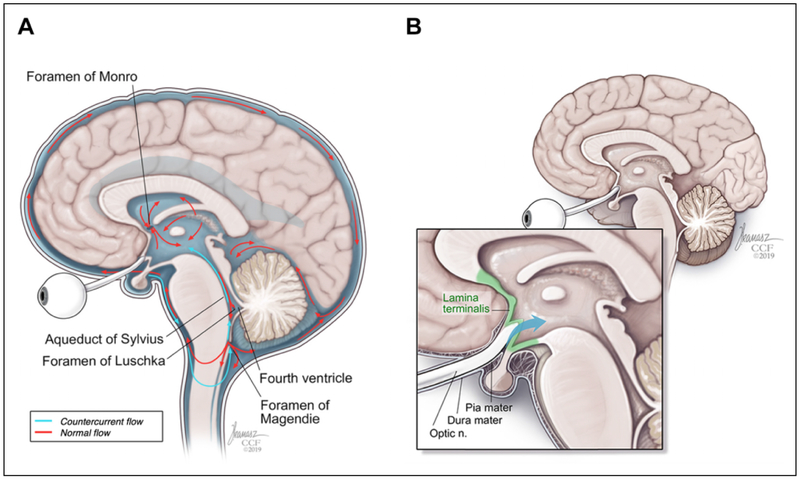

We propose a couple of potential mechanisms to explain how this migration may occur. First, a long indirect pathway for migration from the optic nerve to the lateral ventricles is proposed. The CSF contained within the sheath communicates freely with the subarachnoid space, making it plausible that particles such as SO contained within the perioptic CSF may gain access to the fourth ventricle via retrograde flow through the foramina of Magendie or Luschka (Figure 4A). This may provide the access point for communication between the subarachnoid space and ventricular system. As mentioned previously, there was relative hyperattenuation along the right optic sheath on our patient’s CT scan suggestive of perioptic SO that may have migrated to the lateral ventricles via this indirect pathway.

Figure 4.

(A) An indirect pathway shows how cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) may flow from perioptic space to the fourth ventricle via retrograde flow through the foramina of Magendie or Luschka. (B) A direct pathway postulates that CSF flows transmembranously from perioptic subarachnoid space to the lamina terminalis.

A second pathway is a shorter direct pathway with transmembrane migration of SO from the optic nerve parenchyma, across thin membranous nervous tissue, and into the ventricles. In our patient, we observed SO within the suprasellar cistern, which contains both the optic chiasm and pituitary infundibulum and lies outside the ventricular system. The suprasellar cistern is separated from the lateral ventricle by a thin membrane known as the lamina terminalis (Figure 4B).

Although SO is a hydrophobic substance, studies have shown that intravitreal SO gradually extracts lipophilic compounds such as fatty acids, cholesterol, and methyl esters.33 This results in a hydrophobic-lipophilic mixture that may render it sufficiently amphipathic to migrate across cell membranes and tissues. To date, no studies have directly sampled and evaluated the intraventricular SO, which may provide clues to the mechanism of migration.

It may be worth noting that after SO placement, retrograde leakage of SO into the subconjunctival space may occur. While complications such as subconjunctival fibrosis, subconjunctival granulomas, and orbital SO granulomas have been reported, there are no current reports that postulate possible subconjunctival SO migration to the perioptic space.34-36

Most case reports in which SO migration has occurred (Table 1) demonstrate a variable period of time between SO injection and clinical presentation, ranging from 6.5 months to several years. In many of these cases, however, it is unclear whether the patient returned to the operating room for SO removal. It is possible that in several of these patients, SO was left in the vitreous cavity for a prolonged duration, predisposing them to a higher chance of SO migration. A correlation between SO endotamponade time and intracranial migration of SO is difficult to elucidate without further details from these case reports.

Management

There are no specific published guidelines for the management of patients with intraventricular SO, necessitating a case-by-case approach for the care of these patients.

The frequency of complications from intraocular SO is low.37 Kiilgaard et al37 imaged patients without glaucoma, optic pit, or IOP elevations who had undergone SO endotamponade. After a mean tamponade time of 115 days, none of these patients had detectable SO within the optic nerve or intracranially. These findings suggest that SO migration may be a very rare complication that occurs only in patients with optic disc abnormalities. Similarly, Grzybowski et al38 concluded that the risk of SO migration is so low in the absence of pre-existing glaucoma or optic nerve abnormalities that the use of SO endotamponade should not be modified. However, they suggested imaging in specific cases in which glaucoma or optic nerve abnormalities do exist. Since this complication is rare and most patients are relatively asymptomatic on presentation, surgeons have found no reason to intervene in patients with SO migration beyond conservative management and observation.4,5,13,15,37

In most cases, patients with intraventricular SO who presented with symptoms were successfully treated with conservative management. In these cases, patients initially underwent neuroimaging as part of the workup of symptoms such as headache or dizziness (Table 1). Four patients received neuroimaging after sustaining a fall, 3 after presenting with altered mental status, and another after suffering seizures. Two patients with a medical history of CMV retinitis received imaging after presenting with peripheral neuropathy. There is no evidence to link these symptoms with the presence of intraventricular SO, suggesting incidental discovery of the latter. In our case and 2 others, the patients’ headaches resolved spontaneously without intervention.5,12 Moreover, patients presented with their symptoms as early as 6.5 months and as late as 25 years, with no consistent temporal relationship between SO endotamponade and development of symptoms.

In a few reported cases, symptoms failed to resolve with conservative management. One patient received a ventriculoperitoneal shunt due to persistent headaches despite medical management.6 Intraventricular SO was the assumed cause of this patient’s elevated intracranial pressure and headaches. The headaches resolved following shunt placement, leading Hruby et al6 to support close monitoring of these patients. Their group, among others, has also emphasized control of IOP in patients with intraocular SO to protect against potential SO migration.9,11 Similarly, Eckle et al25 reported a patient who presented with temporal hemianopia in the right eye also had elevated IOP in the left eye. Following aspiration and irrigation of the left optic nerve and removal of SO in the left eye, the patient’s visual defect regressed and IOP normalized. Others have also supported removal of SO, if necessary.27,28

There is no clear evidence to support specific management protocols for patients with intravitreal SO, even when they are found to have glaucoma or abnormalities in the optic nerve. However, clinicians who perform SO endotamponade should be aware that patients with optic nerve abnormalities may be at risk for intracerebral migration, and therefore, sensitive to patients who become symptomatic. In particular, we recommend greater sensitivity to elevated intracranial pressure with headache in patients with pronounced optic nerve atrophy who may not demonstrate papilledema, given the limited funduscopic knowledge about an eye filled with SO or significant optic atrophy. Modifying recommendations for use of SO endotamponade does not seem justified at this time because documented SO migration is rare and the predisposing circumstances remain ambiguous.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Joseph Kanasz, BFA, for contributing the medical illustrations.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant UL1 TR001414.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent was not sought for the present study because of lack of patient identifier and minimal risk to patient safety or privacy.

References

- 1.Federman JL, Schubert HD. Complications associated with the use of silicone oil in 150 eyes after retina-vitreous surgery. Ophthalmology. 1988;95(7):870–876. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33080-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riedel KG, Gabel VP, Neubauer L, Kampik A, Lund OE. Intravitreal silicone oil injection: complications and treatment of 415 consecutive patients. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1990;228(1):19–23. doi: 10.1007/bf02764284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams RL, Beatty RL, Kanal E, Weissman JL. MR imaging of intraventricular silicone: case report. Radiology. 1999;212(1): 151–154. doi: 10.1148/radiology.212.1.r99jl27151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang CC, Chang HS, Toh CH. Intraventricular silicone oil. J Neurosurg. 2013;118(5):1127–1129. doi: 10.3171/2013.1.JNS121570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jabbour P, Hanna A, Rosenwasser R. Migration of silicone oil in the cerebral intraventricular system. Neurologist. 2011;17(2): 109–110. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e31820a9dc3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hruby PM, Poley PR, Terp PA, Thorell WE, Margalit E. Headaches secondary to intraventricular silicone oil successfully managed with ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2013;7(3):288–290. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e31828eeffe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tatewaki Y, Kurihara N, Sato A, Suzuki I, Ezura M, Takahashi S. Silicone oil migrating from intraocular tamponade into the ventricles: case report with magnetic resonance image findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2011;35(1):43–45. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3181fc938d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhn F, Kover F, Szabo I, Mester V. Intracranial migration of silicone oil from an eye with optic pit. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244(10):1360–1362. doi: 10.1007/s00417-006-0267-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eller AW, Friberg TR, Mah F. Migration of silicone oil into the brain: a complication of intraocular silicone oil for retinal tamponade. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129(5):685–688. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00368-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu JT, Apte RS. A case of intravitreal silicone oil migration to the central nervous system. Retina. 2005;25(6):791–793. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200509000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fangtian D, Rongping D, Lin Z, Weihong Y. Migration of intraocular silicone into the cerebral ventricles. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(1):156–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cosgrove J, Djoukhadar I, Warren D, Jamieson S. Migration of intraocular silicone oil into the brain. Pract Neurol. 2013;13(6): 418–419. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2013-000715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen JX, Nidecker AE, Aygun N, Gujar SK, Gandhi D. Intravitreal silicone oil migration into the subarachnoid space and ventricles: a case report and review of literature. Eur J Radiol Extra. 2011;78(2):e81–e83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrex.2011.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell G, Milbourne S, Salman UA, Khan MA. Ocular silicone oil in the lateral cerebral ventricle. J Clin Neurosci Off J Neurosurg Soc Australas. 2013;20(9): 1312–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiao D, Ksendzovsky A, Buell T, Sheehan J, Newman S, Wintermark M. Intraventricular migration of silicone oil: a mimic of traumatic and neoplastic pathology. J Clin Neurosci Off J Neurosurg Soc Australas. 2015;22(7):1205–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potts MB, Wu AC, Rusinak DJ, Kesavabhotla K, Jahromi BS. Seeing floaters: a case report and literature review of intraventricular migration of silicone oil tamponade material for retinal detachment. World Neurosurg. 2018;115:201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.04.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathis S, Boissonnot M, Tasu JP, Simonet C, Ciron J, Neau JP. Intraventricular silicone oil: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(1):e2359. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dababneh H, Hussain M, Bashir A. Mystery case: a case of oil in ventricles: deception for intraventricular hemorrhage. Neurology. 2015;85(4):e30–e31. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swami MP, Bhootra K, Shah C, Mevada B. Intraventricular silicone oil mimicking a colloid cyst. Neurol India. 2015;63(4): 564–566. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.162051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Filippidis AS, Conroy TJ, Maragkos GA, Holsapple JW, Davies KG. Intraocular silicone oil migration into the ventricles resembling intraventricular hemorrhage: case report and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2017;102:695.e7–695.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.03.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boren RA, Cloy CD, Gupta AS, Dewan VN, Hogan RN. Retrolaminar migration of intraocular silicone oil. J Neuro Ophthalmol Off J North Am Neuro-Ophthalmol Soc. 2016;36(4):439–447. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cebula H, Kremer S, Chibbaro S, Proust F, Bierry G. Subarachnoidal migration of intraocular silicone oil. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2017;159(2):347–348. doi: 10.1007/s00701-016-3011-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gnanalingham J, Mcreary R, Charles S, Gnanalingham KK. Migration of intraocular silicone oil into brain. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-220555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim H, Hong HS, Park J, Lee AL. Intracranial migration of intravitreal silicone oil: a case report. Clin Neuroradiol. 2016;26(1): 93–95. doi: 10.1007/s00062-015-0379-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eckle D, Kampik A, Hintschich C, et al. Visual field defect in association with chiasmal migration of intraocular silicone oil. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(7):918–920. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.062893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ni C, Wang WJ, Albert DM, Schepens CL. Intravitreous silicone injection. Histopathologic findings in a human eye after 12 years. Arch Ophthalmol Chic Ill 1960. 1983;101(9):1399–1401. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1983.01040020401013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Budde M, Cursiefen C, Holbach LM, Naumann GO. Silicone oil-associated optic nerve degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001; 131(3):392–394. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00800-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papp A, Tóth J, Kerényi T, Jäckel M, Süveges I. Silicone oil in the subarachnoidal space–a possible route to the brain? Pathol Res Pract. 2004;200(3):247–252. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2004.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biswas J, Verma A, Davda MD, Ahuja S, Pushparaj V. Intraocular tissue migration of silicone oil after silicone oil tamponade: a histopathological study of enucleated silicone oil-filled eyes. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56(5):425–428. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.42425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shields CL, Eagle RC. Pseudo-Schnabel’s cavernous degeneration of the optic nerve secondary to intraocular silicone oil. Arch Ophthalmol Chic Ill 1960. 1989;107(5):714–717. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070010732036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson TM, Johnson MW. Pathogenic implications of subretinal gas migration through pits and atypical colobomas of the optic nerve. Arch Ophthalmol Chic Ill 1960. 2004;122(12):1793–1800. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.12.1793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knecht P, Groscurth P, Ziegler U, Laeng HR, Jaggi GP, Killer HE. Is silicone oil optic neuropathy caused by high intraocular pressure alone? A semi-biological model. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007; 91(10):1293–1295. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.117390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pastor Jimeno JC, de la Rúa ER, Fernández Martínez I, del Nozal Nalda MJ, Jonas JB. Lipophilic substances in intraocular silicone oil. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(4):707–709. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JH, Kim YD, Woo KI, Kong M. Subconjunctival and orbital silicone oil granuloma (siliconoma) complicating intravitreal silicone oil tamponade. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2014;2014: 686973. doi: 10.1155/2014/686973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silverman N, Shore JW, Shinder R. Subconjunctival granulomas from extrascleral silicon oil leak. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(5): 618. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gorovoy IR, Stewart JM. 360° subconjunctival silicone oil after unsutured 23-gauge vitrectomy. Eye Lond Engl. 2013;27(7): 894–895. doi: 10.1038/eye.2013.69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiilgaard JF, Milea D, Lögager V, la Cour M. Cerebral migration of intraocular silicone oil: an MRI study. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 2011;89(6):522–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01793.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grzybowski A, Pieczynski J, Ascaso FJ. Neuronal complications of intravitreal silicone oil: an updated review. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 2014;92(3):201–204. doi: 10.1111/aos.12212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]