Abstract

The present study investigates the mediating role of sense of control in the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing. A cross-sectional study design was employed and a total of 368 international students studying in Turkey consented to voluntarily take part in the study. The participants who were identified using convenience sampling completed the Fear of COVID-19 Scale, Flourishing Scale, and Sense of Control Scale after providing written informed consent. Results indicated that sense of control was positively correlated with fear of COVID-19 and flourishing. It was also observed that a negative correlation was found between the fear of COVID-19 and flourishing. Mediation analysis revealed that sense of control partially mediates the association between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing. The study encourages mental health professionals to consider the role of sense of control in their psychological interventions to reduce fear of COVID-19 and enhance flourishing among international students.

Keywords: Fear of COVID-19, Sense of control, Flourishing, International students, Turkey

The novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has claimed the lives of over 1.3 million and had infected over 53 million people globally by mid-November 2020 (WHO, 2020). Ever since it was declared a pandemic, this outbreak has resulted in various disruptions to different aspects of human life, including education, business life, tourism, the practice of religion, and certain civil and political rights. As an effort to curb the spread of the virus, countries have taken several measures, including enforcing wearing of facemasks and reduction of social contact, mandatory quarantine, closure of schools and travel restrictions, following the declaration of the pandemic. As a result, the normal operations of universities have been halted in 185 countries (Marinoni et al., 2020). As the COVID-19 cases continue to increase, the fear of contracting the virus and dying is more likely to increase. Moreover, the measures introduced to contain the spread of the virus demand changes in behavioral patterns and unintendedly impact on the mental health of individuals (Mamun & Griffiths, 2020). Therefore, cumulative changes have the potential to affect under-represented vulnerable groups, especially students who are pursuing higher education overseas, far away from their families.

Though the life-threatening health crisis during the pandemic has been a common experience for almost everyone, the vulnerability of international students to intense worries regarding their health and the safety of their loved ones could be high. As the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, international students, one of the countries’ major tools of soft diplomacy (Pomerantz, 2020) were confronted with such bold challenges as cancelation of visa appointments, sudden abrupt closure of classes, uncertainty about the future of educational trips, and a disappointing level of attention paid to them (Cheng, 2020). Moreover, there has been the postponement of programs, suspension of examinations, and even discrimination that has escalated already existing stereotypes and prejudices (Mugambi, 2020). Therefore, the vulnerability of international students could be amplified, if they are paid little attention, and deprived of clear guidance and support during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is inevitable that the international students in Turkey also experience unique hardships as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. As in most countries, the Turkish authorities decided to close all schools and universities to avert the spread of the virus as of 16 March 2020 (Sarac, 2020). While international students were left with difficult decisions as to whether to return home or to stay in their study countries (Dickerson, 2020; Pomerantz, 2020; Tran, 2020), those in Turkey were relatively in a better advantage. The Turkish authorities informed the university students either to postpone or suspend their registrations in the spring semester of the 2019–2020 academic year (Anadolu Agency, 2020). Accordingly, during the early stages of the outbreak, while the Turkish students left their dormitories and headed to their hometowns, the international students were allowed to remain in their dormitories.

In Turkey, the coronavirus pandemic had caused the deaths of more than 11,145 individuals by mid-November 2020 (WHO, 2020). The virus had also posed a threat to a total of 7.5 million students studying in the country (Sarac, 2020) including 150,000 international students pursuing their higher education in Turkey (Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities, 2019). With the increase of COVID-19 cases, the chances of being susceptible to the COVID-19 health threat also increases. Given these conditions, it is expected that fear, worry, and stress increase as a normal response to the health threat. However, added to the fear of contracting the coronavirus, the inability to exercise daily routines and forced changes in behavioral patterns may lead individuals to perceive less control over their lives.

When facing a crisis, people tend to look for support from their families. However, international students’ families are often miles away and in different time zones. Coupled with adjustment challenges, such as homesickness, nostalgia, and culture shock (Wu et al., 2015), international students are more likely to experience fear of losing control and worries about their health and the health of their relatives. The fear of loss of control during the pandemic may also affect their sleeping and/or eating patterns (Center for Disease Control & Prevention, 2020). The measures introduced to curb the spread of the virus (such as social distancing, isolation, and quarantine) may disrupt daily life activities and pave the way to isolation, and financial insecurities. Emerging studies have also indicated psychological reactions of individuals to the pandemic, for example, fear, anger, frustration, helplessness, loneliness, and intense uncertainty (Galea et al., 2020; Mamun & Griffiths, 2020; Satici et al., 2020).

Amid the worldwide health crisis, it is more likely that people’s thoughts become preoccupied with the fear concerning COVID-19. This could take an emotional toll, given that people may perceive a reduced sense of control over their lives. Uncertainty surrounding the pandemic and the rapid increase in the COVID-19 cases are among the factors that most likely exacerbate the fear of losing control. The sustained fear of a health threat is more likely to impair logical thinking. Moral judgments may become harsher, and people may become less accepting of foreigners. These situations increase the vulnerability of international students to psychosocial challenges, such as prejudice, rude or cruel comments, strange looks, xenophobia, and discrimination (Hardinges, 2020; Mugambi, 2020). Therefore, international students may not only experience the threat of coronavirus, but they can also be potentially vulnerable to stigma and discrimination.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, international students may experience difficulties including increased fear and worries. However, their tendency to manage their fear from spiraling out of control may depend on how they assess resources and respond to the COVID-19 threat. While some may choose to ground themselves in the present moment and engage in their daily life activities, others may choose to ruminate about the pandemic. One way of remaining resilient during the pandemic is through developing a sense of personal control (Williams, 2007). Sense of control is a belief about the extent to which a person can shape his/her course of social outcomes (Lachman & Weaver, 1998). Therefore, the tendency of international students to feel in control of their fear during the coronavirus pandemic may contribute to their wellbeing positively.

Being resilient during the COVID-19 pandemic may vary depending on the sense of control individuals possess and/or how they manage their fear and anxiety. As Keeton et al. (2008) demonstrate, sense of control is inversely associated with depression and anxiety. In other words, a higher sense of enduring control may predict lower levels of psychological distress, and higher levels of possibilities in managing fear related to COVID-19. It was also found that a higher level of perceived control is associated with more positive effects and life satisfaction (Baumeister, 2005; Lachman & Weaver, 1998). Lack of control is associated with the severity of anxiety and mood disorders (Rosenbaum et al., 2012). Therefore, it is hypothesized that sense of control helps to regulate the fear of COVID-19 and enhance engagement in daily life.

Though the coronavirus pandemic has continued to be life-threatening and caused changes to daily lives, it is possible that people can adjust to the outbreak and thrive. Among the strategies people use to adapt are volunteerism, strengthening relationships, facing hardships, and reflecting on their life meaningfully (Vanderweele, 2020). Irrespective of the coronavirus threat, it is possible that people can rapidly change their normal behavior to adapt to the COVID-19 challenge and continue to live in the optimal range of human functioning. Such adaptive tendencies and choices of remaining positive despite the afflictions can be associated with flourishing. To flourish, an individual must have such core features as positive emotions, engagement, meaning, achievement, and positive relationships (Huppert & So, 2013; Seligman, 2013).

A number of studies posit the association between sense of control and certain positive psychological outcomes. To mention a few, sense of control was found to have a positive relationship with positive health (Will Crescioni et al., 2011), positive outcomes (Tangney et al., 2004), and happiness (Ramezani & Gholtash, 2015). Sense of control is positively associated with subjective well-being (Chen et al., 2020). Overall, self-control emerges as an important factor for an individual to thrive and flourish. On the other hand, a low level of self-control is associated with several negative life outcomes (Thakur & Shashwati, 2019). Therefore, it is hypothesized that a sense of control can enhance flourishing and mediate the association between the fear of COVID-19 and flourishing.

Though there are several studies (e.g., Ahorsu et al., 2020; Galea et al., 2020; Mamun & Griffiths, 2020; Satici et al., 2020) conducted on COVID-19 and its impact on the mental health of the public, there is a paucity of research work on the role of sense of control in the international students’ population. Therefore, the objective of this study is to examine the role of sense of control in the association between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing in the international students’ sample in Turkey. Therefore, the present study proposes the following hypotheses (Hs):

H1. Fear of COVID-19 would be negatively related to flourishing.

H2. The association between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing would be mediated by sense of control.

Method

Participants and Procedures

This study is a cross-sectional descriptive study that aims to investigate the association among fear of COVID-19, sense of control, and flourishing in the international students’ sample. A total of 368 international students studying in Turkey during the 2019–2020 academic year were included in the study. Convenience sampling method was used to recruit the study participants who consented to complete an online survey voluntarily. Participants were informed that the survey was confidential, and they were free to withdraw from the study at any time. The Google Form included self-report measures such as Fear of COVID-19 Scale, Sense of Control Scale, and Flourishing Scale. The survey link was shared with study participants through Facebook and WhatsApp groups of international students’ associations in different cities in Turkey. The study procedures were performed under the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Among the 368 participants, 19.02% were doctoral students, 28.80% were master’s degree students, and 52.18% were undergraduate students. The participants were originally from 64 countries, of which 72.83% were from Africa, 21.2% from Asia, 4.89% from Europe, and 0.2% from South America. Over 30% of these participants were self/family sponsored. Their ages ranged from 18 to 41 years, with an average of 25.41 years (SD = 5.07) and only 25.8% were females. One out of five participants were married. Detailed information about the participants is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (N = 368)

| Demographics | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 273 | 74.2 |

| Female | 95 | 25.8 | |

| Region | Africa | 268 | 72.83 |

| Asia | 78 | 21.20 | |

| Europe | 18 | 4.89 | |

| America | 2 | 0.2 | |

| Relationship status | Single | 296 | 80.4 |

| Married | 72 | 19.6 | |

| Sources of income | Scholarships | 254 | 69 |

| Self/family sponsored | 114 | 31 | |

| Knowledge of someone infected with COVID-19 | Yes | 47 | 12.8 |

| No | 321 | 87.2 | |

| Length of stay in Turkey | Less than 1 year | 116 | 31.5 |

| 1–3 years | 142 | 38.6 | |

| 4–6 years | 73 | 20.9 | |

| More than 6 years | 36 | 9.5 | |

Measures

This survey consists of three measures: Fear of COVID-19 Scale, Flourishing Scale, and Sense of Control Scale.

Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S)

The FCV-19S is a unidimensional scale that assesses the fear of COVID-19 and was developed by Ahorsu et al. (2020). The instrument comprises seven items (e.g., ‘My heart races when I think about getting coronavirus-19’) which are responded to on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scores that can be obtained from the FCVS-19 vary between 7 and 35, and higher scores indicate a greater fear of COVID 19. The internal consistency of the FCV-19S in the current study is .87.

Flourishing Scale (FS)

The FS is a unidimensional scale that includes eight items that describe important aspects of human functioning, ranging from positive relationships to feelings of competence, to having meaning and purpose in life (Diener et al., 2009). Each item of the FS is answered on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). All of the items are phrased in a positive direction. The scores obtained vary between 8 and 56, with higher scores signifying that respondents view themselves in positive terms. The internal consistency of the FS in the current study is 96.

Sense of Control Scale (SCS)

The SCS has twelve items that assess the extent to which participants generally feel in control of their lives. It was developed by Lachman and Weaver (1998). The scale has two dimensions: personal mastery and perceived constraints. Personal mastery refers to one’s sense of efficacy; for example, ‘When I really want to do something, I usually find a way to succeed at it’. Perceived constraints indicate to what extent one believes there are obstacles or factors beyond one’s control that interfere with reaching goals; for example, ‘I have little control over the things that happen to me’. Responses were given on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree). The perceived constraint items were reverse coded such that high scores on the total scale correspond to a higher sense of control. Therefore, the average score can range from 12 to 84, with higher scores indicating a higher sense of control. The internal consistency of the SCS in the current study is .76.

Demographic Questionnaire

This was prepared by researchers and included questions regarding the participants’ gender, age, class levels, region, and knowledge of someone infected by the virus.

Data Analysis

This study aims to investigate whether sense of control mediates the association between the fear of COVID-19 and flourishing in the international students’ sample. Firstly, the descriptive statistics and the correlation between the variables are presented. After this, a mediation analysis is conducted to test the mediation effects. The data screening and the mediation analysis are both conducted using IBM SPSS-26 and PROCESS Macro 3.3 add on (Hayes, 2018). Five thousand bootstrap replicates are drawn and coefficients for both direct and indirect effects are created in a 95% confidence interval. Significance is determined when the confidence interval does not include zero.

Results

A preliminary analysis indicates that above one-tenth of the participants knew someone who had been infected with COVID-19. Normality was checked using skewness, and kurtosis values. When the skewness coefficients were examined, flourishing, sense of control, and fear of COVID-19 were − 1.64, .10, and .23, respectively. The kurtosis values were also 2, − .57, and − .71, respectively. The skewness and kurtosis values of the variables vary between − 2 and + 2, indicating that the data of all the measures comply with normal distribution (George & Mallery, 2010).

The latent variables in the present study are fear of COVID-19, sense of control, and flourishing. A correlation analysis reveals that flourishing has a significantly negative correlation with the fear of COVID-19 (r = − .16, p < .01), but a positive relationship with sense of control (r = .19, p < .01). In addition, fear of COVID-19 has a positive correlation (r = .32, p = .01) with sense of control (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation between variables and descriptive statistics (n = 368)

| Variables | Possible range | Mean (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Flourishing | 8–56 | 44.06 (11.03) | − 1.64 | 2 | – | ||

| 2. Fear of COVID | 7–35 | 19.99 (6.60) | 0.10 | − 0.57 | − .16** | – | |

| 3. Sense of control | 12–84 | 53.86 (10.84) | 0.23 | − 0.71 | .19** | .32** | – |

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level

Before mediation analysis, lack of multicollinearity, multivariate normality, and linearity were checked. The data was checked for outliers and no outlying values was determined. VIF values were > 10, and the tolerance value was < 10. A Durbin-Watson test r was 1.9, indicating no autocorrelation (Field, 2013).

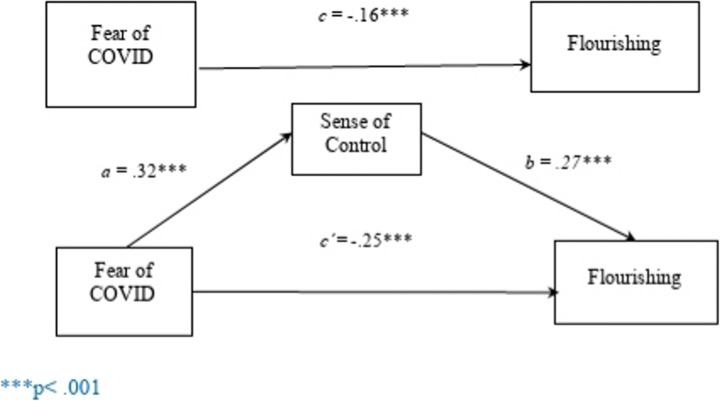

The basic mediation analysis, which allows a sense of control (M) in the analysis of the direct and indirect effects of the Fear of COVID-19 (X) on Flourishing (Y) was calculated by an SPSS PROCESS macro (Model 4). A bootstrap estimation program was used to explore the stability of the mediating effects. The significance of the indirect effect was determined on the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval with 5000 bootstrap samples. A statistical diagram of the basic mediation model is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The statistical diagram of basic mediation model

Results show that the direct effects are significant. The direct effect from the fear of COVID-19 to a sense of control (a path) is significant, β = .32, t (366) = 6.54, p = .001. An increase in the level of fear of COVID-19 could help a person increase their sense of control. The direct effect from sense of control to flourishing (b path) is also significant β = .27, t (365) = 5.17, p = .001. Path c indicates that fear of COVID-19 predicts flourishing, β = − .25, t (365) = − 4.76, p = .001. The total effect of fear of COVID-19 on flourishing is significant β = − .16, t (366) = − 3.16, p = .001, and when sense of control, which is the mediation variable, is included in the model, this effect (β = − .16) decreases to (β = − .25). Sense of control acts as a mediator between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing. According to the bootstrapping results, the indirect effect of fear of COVID-19 and flourishing confidence interval does not include zero 0.15, 95% CI (.0774–.2354). Research findings indicate that a sense of control mediates between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing.

Discussion

The purpose of this study is to explore the mediating role of sense of control in the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing. The findings of this study may advance our understanding of how sense of control is related to the fear of COVID-19 pandemic in international students’ samples. Moreover, it may help mental health professionals to design interventional programs that could enhance the sense of control to boost the well-being of international students.

Consistent with the first hypothesis (fear of COVID-19 would be negatively related to flourishing), the result of the study reveals an inverse relationship between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing. The result demonstrates that fear of COVID-19 predicts flourishing negatively. This is in parallel with the findings of previous research (Bakioğlu et al., 2020) that report a negative relationship between fear of coronavirus and positivity (an attitude that includes thoughts, words, and images that help growth, development, and success). The more the fear of COVID-19 increases, the less individuals tend to make use of their inner strengths (potentials) to remain productive and to flourish.

The second hypothesis of the study tests the mediating role of sense of control in the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing. As anticipated, sense of control partially mediates the association between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing. This suggests that sense of control may function as an important factor that accounts for the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing in international students’ context. This finding is partially in line with a study that demonstrates a mediating role of sense of control in the association between study participants’ perceived knowledge regarding coronavirus infection and emotional well-being (Yang & Ma, 2020). This indicates that perceived knowledge of coronavirus infection can boost individuals’ sense of control that can reduce the fear of the COVID-19 pandemic and foster a tendency to better cope mentally and emotionally.

Our findings reveal that international students are able to sustain their sense of control, even during the coronavirus outbreak. Surprisingly, the increased fear of COVID-19 in international students in Turkey did not adversely affect their sense of control. This could be partially justified by the care and attention of the Turkish Council of Higher Education authorities, and Turkish Scholarship given to international students (Toprak, 2020). While international students in a number of countries are experiencing frightening conditions due to the COVID-19 threat and uncertainty concerning their study plans (Dickerson, 2020; Pomerantz, 2020; Tran, 2020), their fellow students in Turkey are comforted by the clear guidance of the Turkish Council of Higher Education Authorities and support of International Student Associations across the country. They are allowed to stay in dormitories (Toprak, 2020), provided with online awareness creation programs concerning the pandemic and given the opportunity to make their own decisions on whether to continue their studies online or to withdraw (Sarac, 2020).

Apart from the discussed external factors, international students’ tendencies to choose to focus their minds on things they can control might help them boost their sense of control. Instead of focusing on their fear and allowing uncertainty to dominate their minds, they may choose to shift their focus towards their internal strengths and resources. Altogether, these internal and external factors may support international students in perceiving themselves as being in control of possible adversities during the pandemic.

This study is not free of limitations. First, the cross-sectional design of the study cannot determine the cause and effect association between the variables investigated. Moreover, the use of self-report measures to collect data may create a response bias. Therefore, research studies that involve experimental design are needed to broaden the awareness of how sense of control interacts with fear of COVID-19 and flourishing. In this study, an attempt is made to explore the mediating role of sense of control in the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing. Therefore, it is important to further investigate how fear of COVID-19 positively explains sense of control. Finally, the findings in this study are based on international students’ samples in Turkey. As a result, generalizing the study results needs to be considered with caution.

In conclusion, despite the limitations, this study reveals important contributions regarding the role of sense of control. The results suggest that the fear of COVID-19 is a risk factor for flourishing. Moreover, sense of control is a mediating mechanism through which fear of COVID-19 is associated with flourishing among the international student population in Turkey. In brief, this study findings may provide directions towards tailoring intervention for enhancing sense of control in the maintenance of international students’ psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of University’s Research Ethics Board and with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Aman Sado Elemo, Email: aselemo@gelisim.edu.tr.

Abdulatif Hajjismael Ahmed, Email: abdulatifha@anadolu.edu.tr.

Ergün Kara, Email: ergunpdr@hotmail.com.

Mufti Kasim Zerkeshi, Email: muftikasimz@ogr.iu.edu.tr.

References

- Ahorsu, D. K., Lin, C. Y., Imani, V., Saffari, M., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2020). The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–9. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Anadolu Agency (2020). Higher Education council allows students to defer studies, World University News, Accessed on July 12, 2020 from https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20200404090539581.

- Bakioğlu, F., Korkmaz, O., & Ercan, H. (2020). Fear of COVID-19 and positivity: Mediating role of intolerance of uncertainty, depression, anxiety, and stress. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10.1007/s11469-020-00331-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Baumeister RF. The cultural animal: Human nature, meaning, and social life. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/managing-stress-anxiety.html.

- Chen B, Luo L, Wu X, Chen Y, Zhao Y. Are the lower class really unhappy? Social class and subjective well-being in Chinese adolescents: moderating role of sense of control and mediating role of self esteem. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2020;22:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00253-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, R. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis and international students. Retrieved on July 13, 2020 from https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2020/03/19/higher-ed-institutions-arent-supporting-international-students-enough-during-covid.

- Dickerson, T. (2020). ‘My world is shattering’: Foreign students stranded by coronavirus. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/25/us/coronavirus-international-foreign-students-universities.html.

- Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi D, Oishi S, Biswas-Diener R. New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research. 2009;39:247–266. doi: 10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. P. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics: And sex and drugs and rock ‘n’ (4th ed.). Sage.

- Galea, S., Merchant, R. M., & Lurie, N. (2020). The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Internal Medicine. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562. [DOI] [PubMed]

- George, D., & Mallery, M. (2010). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. 17.0 update (10a ed.). Pearson.

- Hardinges, N. (2020). British-Chinese people tell of ‘discrimination’ and hate as fears rise over coronavirus. https://www.lbc.co.uk/news/british-chinese-people-discrimination-coronavirus/.

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Huppert FA, So TTC. Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Social Indicators Research. 2013;110:837–861. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeton CP, Perry-Jenkins M, Sayer AG. Sense of control predicts depressive and anxious symptoms across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(2):212–221. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Weaver SL. The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74(3):763–773. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun MA, Griffiths MD. First COVID-19 suicide case in Bangladesh due to fear of COVID-19 and xenophobia: Possible suicide prevention strategies. Asian journal of psychiatry. 2020;51:102073. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinoni, G., Land, H. & Jensen, T. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on higher education around the world: AIU global survey report. International Association of Universities. https://www.iau-aiu.net/IMG/pdf/iau_covid19_and_he_survey_report_final_may_2020.pdf.

- Mugambi, M. M. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and international students abroad. https://uonresearch.org/blog/covid-19-pandemic-and-international-students-abroad/.

- Pomerantz, P. (2020). Another COVID-19 Victim: International Education. The Hill, https://thehill.com/opinion/education/503954-another-covid-19-victim-international-education.

- Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities (2019). “17 thousands of 150,000 international students in Turkey are recipients of YTB scholarships” (Accessed 12 Nov 2020) https://www.ytb.gov.tr/en/news/17-thousands-of-150-000-international-students-in-turkey-are-recipients-of-ytb-scholarships.

- Ramezani SG, Gholtash A. The relationship between happiness, self-control and locus of control. International Journal of Educational and Psychological Researches. 2015;1(2):100–104. doi: 10.4103/2395-2296.152222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum DL, White KS, Gervino EV. The impact of perceived stress and perceived control on anxiety and mood disorders in noncardiac chest pain. Journal of Health Psychology. 2012;17(8):1183–1192. doi: 10.1177/1359105311433906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarac, Y. (2020). Opinion -Turkish higher education in days of pandemic. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/analysis/opinion-turkish-higher-education-in-days-of-pandemic/1813314.

- Satici, B., Gocet-Tekin, E., Deniz, M. E., & Satici, S. A. (2020). Adaptation of the fear of COVID-19 scale: Its association with psychological distress and life satisfaction in Turkey. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction.10.1007/s11469-020-00294-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2013). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. In First atria paperback edition March 2013. Atria Paperback.

- Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality. 2004;72(2):271–324. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, D., & Shashwati, S. (2019). Doing well & feeling well: Do self-control and flourishing go hand-in-hand? International Journal of Basic and Applied Research, 9(3), 826–839.

- Toprak, I. (2020). International students choose to stay in Turkey. Anadolu Agency. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/turkey/-international-students-choose-to-stay-in-turkey/1784922.

- Tran, L. Y. (2020). Understanding the full value of international students, University World News, The Global Window on Higher Education. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20200820103708349.

- Vanderweele, T. (2020). How to flourish during the coronavirus pandemic: Research from the human flourishing program at Harvard. https://www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2020/03/61677/.

- Will Crescioni A, Ehrlinger J, Alquist JL, Conlon KE, Baumeister RF, Schatschneider C, Dutton GR. High trait self-control predicts positive health behaviors and success in weight loss. Journal of Health Psychology. 2011;16(5):750–759. doi: 10.1177/1359105310390247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD. Ostracism. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58(1):425–452. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2020). WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/.

- Wu H, Garza E, Guzman N. International students’ challenges and adjustment to college. Education Research International. 2015;2015:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2015/202753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Ma J. How an epidemic outbreak impacts happiness: Factors that worsen (vs. protect) emotional well-being during the coronavirus pandemic. Psychiatry Research. 2020;289:113045. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]