Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the effect of sugar concentration and fermentation time on the antibacterial activity of kombucha beverages prepared with four herbal teas. Four types of herbal teas including, black and green tea, lemon verbena, and peppermint were prepared then sweetened with 2, 5, and 8% sugar. The herbal teas inoculated with actively kombucha culture and after 7, 14, and 21 days, the antibacterial activity of the supernatant of beverages was evaluated against four bacteria based on agar well diffusion method. RSM was used to investigate the effect of fermentation time, sugar concentration, and tea type on the antibacterial activity of beverages. Sugar concentration and fermentation time showed a significant effect on the antibacterial activity of beverages-against all tested bacteria and type of herbal tea affected the antibacterial activity of beverages-against E. coli and S. aureus. Kombucha prepared with black tea at sugar 8% and fermentation time of 21 days showed the most antibacterial activity against B. cereus. The most antibacterial activity against S. aureus was observed in kombucha beverages prepared with green tea and peppermint for fermentation time of 21 days, at 2% and 8% sugar, respectively. Prepared beverages with peppermint and lemon verbena at 8% sugar and 21 days of fermentation showed the most antibacterial activity against E. coli and S. dysenteriae respectively. Generally, to achieve the highest antibacterial activity against the tested bacteria recommended preparation of kombucha beverages at the sugar of 8% and fermentation time of 21 days.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13197-020-04699-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Antibacterial activity, Fermentation conditions, Kombucha beverage, RSM

Introduction

The food sciences industries trend toward minimally processed products, without additives, with high nutritional value, appropriate flavor, taste, and health benefits.

Due to the disadvantages of using carbonated beverages and the high sugary content, which pose a high risk for the health of communities, alternative products require extensive studies. Today, Kombucha beverage can be considered as a product with probiotic and functional properties. Kombucha is a fermented beverage, which is prepared from fermentation of the sweetened tea by a symbiosis of bacteria and yeasts (Villarreal Soto et al. 2018).

This sweet and sour beverage is composed of two phases: a floating biofilm and a sour liquid phase. Acetic acid, gluconic acid, and ethanol are the main components in the liquid. Other compounds in kombucha beverages include tartaric acid, malic acid, lactic acid, citric acid, 14 amino acids, Vitamins (B1, B2, B6, B12, and C) and some minerals and hydrolytic enzymes (Malbasa et al. 2011).

The composition and metabolic concentration of kombucha depend on the source of tea fungus, the time of fermentation, and the concentration of sugar (Haizhen et al. 2008).

The fermentation process leads to the formation of a floating biofilm on the surface of the liquid phase, which forms a large microbial consortium includes acetic acid bacteria (Komagataeibacter, Gluconobacter, and Acetobacter species), lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus, Lactococcus) and yeasts (Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Saccharomycodes ludwigii, Kloeckera apiculata, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Zygosaccharomyces bailii, Torulaspora delbrueckii, Brettanomyces bruxellensis) (Villarreal Soto et al. 2018).

Yeasts and bacteria in kombucha are involved in metabolic activities and the utilization of substrates. The sugar in the sweetened tea is hydrolyzed to glucose and fructose by yeasts, then glucose is converted into ethanol and carbon dioxide by yeasts. In the next step, ethanol is converted into acetic acid by acetic acid bacteria. The pH of kombucha beverage decreases due to the production of organic acids during the fermentation. The concentration of ethanol in kombucha beverage rarely exceeds 1%, while if the fermentation time is prolonged, the amount of acetic acid can reach 3%; however, the amount is typically less than 1% (Jayabalan et al. 2014; Sreeramulu et al. 2000).

Kombucha beverages have many potential beneficial effects on human health. Biological activities such as antimicrobial, antioxidant, hepatoprotective, and anticancer properties of kombucha tea have reported in nonhuman experimental studies (Jayabalan et al. 2014).

Antibacterial activity of kombucha beverage against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria have reported in numerous studies (Battikh et al. 2012; Greenwalt et al. 1998; Sreeramulu et al. 2000).

Many components such as organic acids (acetic acid, gluconic acid, glucuronic acid, etc.), bacteriocins, proteins, enzymes, tea polyphenols and their derivatives that produced during Kombucha fermentation contribute to its antibacterial activity (Battikh et al. 2013; Greenwalt et al. 1998; Jayabalan et al. 2014; Sreeramulu et al. 2000; Bhattacharya et al. 2016).

Nowadays, the tendency to consume foods with a natural nature and away from industrial processes has caused to be attention the consumption of this beverage. Black tea is typically used to make this beverage. The biological activities and compositions of this beverage depend on several factors, including different tea leaf varieties, amounts of sugar (sucrose), fermentation time, and composition of tea fungus (Jayabalan et al. 2014; Wolfe and Dutton 2015).

In this study, Kombucha beverages with four herbal teas including, black and green tea, lemon verbena, and peppermint at different concentrations of sugar and in different fermentation time were prepared. Antibacterial activity of the fermented beverages is evaluated against two gram-negative bacteria of E. coli and S. dysenteriae, and two gram-positive bacteria of S. aureus and B. cereus. Using by Response Surface Methodology (RSM), the effect of fermentation time, sugar concentration, and herbal tea type on the antibacterial activity of Kombucha beverages were analyzed.

Materials and methods

Preparation of kombucha beverages

Leaves of lemon verbena (Lippia citriodora) were prepared from Azadshahr Islamic Azad University (Iran) research farm, and black tea (Camellia sinensis) and green tea (Camellia sinensis) from tea gardens of the Lahijan City in northern Iran. peppermint (Mentha piperita) was purchased from the medicinal herbs store. 1 g of the dried leaf of each plant was mixed with sugar (sucrose) with weight (2, 5, and 8 g) and then added boiled water until the total volume reached to 100 ml. It was placed at 70 °C for 15–20 min for brewing. The mixture was filtrated. The filtrate was inoculated with 2.5 g/l of actively growing Kombucha culture and sealed for different fermentation times (7, 14, and 21 days) at room temperature (25 °C). The fermented liquids were centrifuged at 5000×g for 15 min and the supernatant was passed through 0.22 μm sterile syringes filter (Jet-Biofil). The filtrated liquids were used to evaluate the antibacterial activity (Battikh et al. 2012; Talawat et al. 2006).

Preparation of bacterial strains

The strains of the tested bacteria were two gram-negative bacteria of Escherichia coli (PTCC 1338) and Shigella dysenteriae (PTCC 1188), and two gram-positive bacteria of Staphylococcus aureus (PTCC 112) and Bacillus cereus (PTCC 1154). They were purchased from the Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology (IROST) in a lyophilized form. Then, they were recovered in BHI (Brain Heart Infusion) medium (Merck) for 24 h at 37 °C in the microbiology laboratory of the Azadshahr Branch, Islamic Azad University. The 24-h culture of each bacterium was inoculated into Nutrient Broth culture medium (Merck) and it was incubated at 37 °C to obtain turbidity equal to 0.5 McFarland = 1.5 × 108 CFU/ml (Weinstein et al. 2018; Greenwalt et al. 1998; Sreeramulu et al. 2000).

Evaluation of antibacterial activity by well method

Antibacterial activity was evaluated based on the agar well diffusion method. For this purpose, a bacterial suspension equivalent to 0.5 McFarland (1.5 × 108 CFU/ml) was prepared from all bacterial strains, and a uniform culture was prepared from this suspension on the surface of the Mueller Hinton Agar medium (Merck). Then, wells with a diameter of 8 mm were created by using a cork borer. The supernatants obtained from each beverage were poured into the wells, and plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 to 48 h. Subsequently, the sensitivity and resistance of the bacteria were determined by measuring the inhibition zone diameter around the wells (Weinstein et al. 2018; Sreeamulu et al. 2000).

Measuring pH

The pH of the fermented beverages was measured from the inoculation start of the active culture of Kombucha until the end of the fermentation time, at 48-h intervals by PH meter was calibrated with KCl solution at 10, 7 and 4 pH (Jacobson 2006).

Experimental design and statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of the data was performed using the Design-Expert software (Version 10.0.0, Stat-ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). The experimental design of CCD containing 3-level-2-numeric factors and a 4-level-1-categoric factor with 3 replicates in factorial, axial, and center points with alpha equal to one were used.

The 3-level-2-numeric factors of sugar concentration (2, 5, and 8%) and fermentation time (7, 14, and 21 days) were chosen as main variables and designated as X1, X2, and X3, respectively, which are represented in Supplementary material 1. The variables were coded according to Eq. (1):

| 1 |

where xi = (dimensionless) coded value of the variable Xi,, X0 = the value of Xi at the center point, and = the step change. The behavior of the system was explained by the following second-degree polynomial equation:

| 2 |

where Y is the response, 0, i, ii, and ij are constant coefficients and xi represents the coded independent variables.

The 4-level-1-categoric factor of "type of herbal tea" was chosen as another main variable which contains black and green tea, lemon verbena, and peppermint (Supplementary material 1).

Additionally, the regression analysis and the coefficients were calculated. The fit of the regression model was checked by the adjusted coefficient of determination (R2Adj). The two-dimensional graphical representation of the system behavior called the response surface was used to describe the individual and cumulative effects of the variables as well as the mutual interactions between the variables on the dependent variable. a statistically significant and the suitable polynomial response surface models of each tested bacteria inhibition zone response variable for each tea were detected.

Results

The experiments contain 36 treatments that considering three replicates for each treatment, the number of experimental runs are 108. The treatments related to the effect of fermentation conditions on pH variations and antibacterial activity of four kombucha beverages against four tested bacteria. The results of antibacterial activity are based on the diameter of the inhibition zone and the mean of three replications that are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Central composite design arrangement of process variable and actual values and predicted values of responses

| Treatment | Sugar con. (%) | Fermentation time (day) | Inhibition zone of bacteria*(mm) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH* | E. coli | S. dysenteriae | S. aureus | B. cereus | ||||||||

| Actual values | Predicted values | Actual values | Predicted values | Actual values | Predicted values | Actual values | Predicted values | Actual values | Predicted values | |||

| 1 | 2 | 7 | 3.80 ± 0.10 | 3.95 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 2.88 | 14.00 ± 0.00 | 14.92 | 3.33 ± 1.15 | 5.04 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 4.07 |

| 2 | 2 | 7 | 4.17 ± 0.15 | 3.96 | 10.67 ± 0.57 | 9.73 | 18.33 ± 0.57 | 17.97 | 16.33 ± 2.51 | 15.75 | 9.33 ± 0.57 | 9.83 |

| 3 | 2 | 7 | 3.40 ± 0.20 | 3.58 | 11.00 ± 1.00 | 7.30 | 15.00 ± 1.00 | 13.73 | 3.33 ± 1.15 | 4.60 | 11.00 ± 1.00 | 7.50 |

| 4 | 2 | 7 | 3.73 ± 0.15 | 3.89 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 2.68 | 16.00 ± 2.00 | 14.47 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.45 | 11.00 ± 1.00 | 6.83 |

| 5 | 2 | 14 | 4.23 ± 0.15 | 3.85 | 9.00 ± 0.00 | 6.38 | 14.00 ± 2.00 | 13.35 | 13.00 ± 1.00 | 10.10 | 7.33 ± 2.00 | 6.60 |

| 6 | 2 | 14 | 3.90 ± 0.10 | 3.95 | 9.00 ± 0.00 | 12.56 | 15.00 ± 1.00 | 17.07 | 17.00 ± 1.00 | 19.47 | 11.33 ± 1.52 | 12.75 |

| 7 | 2 | 14 | 3.53 ± 0.15 | 3.74 | 10.00 ± 2.00 | 7.30 | 12.00 ± 0.00 | 11.83 | 9.33 ± 0.57 | 10.15 | 9.00 ± 1.00 | 8.31 |

| 8 | 2 | 14 | 4.10 ± 0.10 | 4.02 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 3.88 | 10.00 ± 0.00 | 14.01 | 10.00 ± 0.00 | 9.17 | 3.00 ± 0.57 | 7.42 |

| 9 | 2 | 21 | 3.60 ± 0.10 | 3.93 | 10.00 ± 0.00 | 7.88 | 14.00 ± 0.00 | 13.17 | 14.67 ± 2.51 | 17.07 | 19.00 ± 5.00 | 14.32 |

| 10 | 2 | 21 | 3.80 ± 0.10 | 4.13 | 16.00 ± 2.00 | 13.39 | 19.67 ± 2.51 | 17.56 | 25.00 ± 2.00 | 25.11 | 22.67 ± 2.51 | 20.86 |

| 11 | 2 | 21 | 4.70 ± 0.1 | 4.07 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 5.30 | 9.00 ± 0.00 | 11.31 | 19.00 ± 2.64 | 17.63 | 11.00 ± 1.00 | 14.31 |

| 12 | 2 | 21 | 4.43 ± 0.15 | 4.33 | 9.33 ± 0.57 | 8.43 | 17.33 ± 3.51 | 14.94 | 23.33 ± 6.50 | 19.81 | 14.00 ± 4.00 | 13.19 |

| 13 | 5 | 7 | 3.33 ± 0.15 | 3.21 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 5.25 | 12.00 ± 0.00 | 14.22 | 10.33 ± 0.57 | 7.90 | 13.00 ± 2.00 | 11.09 |

| 14 | 5 | 7 | 3.33 ± 0.05 | 3.31 | 10.67 ± 0.57 | 9.32 | 15.00 ± 1.00 | 14.67 | 14.00 ± 1.00 | 13.05 | 11.00 ± 1.00 | 11.07 |

| 15 | 5 | 7 | 2.83 ± 0.15 | 2.71 | 11.67 ± 2.51 | 12.34 | 16.33 ± 2.51 | 15.59 | 11.00 ± 1.00 | 7.63 | 13.33 ± 1.52 | 13.85 |

| 16 | 5 | 7 | 3.13 ± 0.15 | 3.05 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 2.64 | 14.67 ± 1.52 | 13.44 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 2.87 | 11.00 ± 1.00 | 12.07 |

| 17 | 5 | 14 | 3.00 ± 0.10 | 2.96 | 14.00 ± 2.00 | 9.58 | 15.33 ± 4.16 | 14.36 | 14.00 ± 1.00 | 12.00 | 13.00 ± 1.00 | 13.49 |

| 18 | 5 | 14 | 3.37 ± 0.05 | 3.15 | 11.00 ± 1.00 | 12.99 | 16.00 ± 2.00 | 15.47 | 15.33 ± 0.57 | 15.81 | 13.33 ± 1.52 | 13.86 |

| 19 | 5 | 14 | 2.50 ± 0.10 | 2.71 | 15.00 ± 3.00 | 13.18 | 15.00 ± 1.00 | 15.40 | 13.00 ± 1.00 | 12.22 | 15.00 ± 1.00 | 14.53 |

| 20 | 5 | 14 | 3.00 ± 0.10 | 3.03 | 12.00 ± 1.00 | 10.03 | 15.00 ± 1.00 | 14.69 | 11.00 ± 1.00 | 10.63 | 14.33 ± 1.52 | 12.53 |

| 21 | 5 | 21 | 2.90 ± 0.10 | 2.88 | 9.00 ± 0.00 | 11.92 | 16.00 ± 1.00 | 15.89 | 16.00 ± 2.00 | 18.01 | 17.00 ± 1.00 | 21.09 |

| 22 | 5 | 21 | 3.30 ± 0.10 | 3.18 | 15.33 ± 3.51 | 14.66 | 16.00 ± 1.00 | 17.67 | 24.00 ± 3.00 | 20.50 | 22.67 ± 2.51 | 21.85 |

| 23 | 5 | 21 | 2.50 ± 0.10 | 2.89 | 14.00 ± 2.00 | 12.01 | 18.00 ± 1.00 | 16.59 | 16.00 ± 2.64 | 18.74 | 24.00 ± 1.00 | 20.40 |

| 24 | 5 | 21 | 3.07 ± 0.05 | 3.18 | 16.67 ± 3.05 | 15.42 | 16.00 ± 2.00 | 17.33 | 15.00 ± 1.00 | 20.31 | 16.33 ± 2.51 | 18.18 |

| 25 | 8 | 7 | 3.00 ± 0.10 | 3.16 | 12.00 ± 1.00 | 7.88 | 15.00 ± 1.00 | 14.50 | 12.00 ± 0.00 | 14.85 | 19.00 ± 1.00 | 17.21 |

| 26 | 8 | 7 | 3.10 ± 0.20 | 3.34 | 10.00 ± 1.00 | 9.17 | 11.33 ± 0.57 | 12.33 | 15.00 ± 2.00 | 14.44 | 12.00 ± 0.00 | 11.42 |

| 27 | 8 | 7 | 2.73 ± 0.15 | 2.53 | 13.33 ± 2.51 | 17.63 | 17.00 ± 3.00 | 18.43 | 13.33 ± 1.52 | 14.74 | 16.00 ± 1.00 | 19.31 |

| 28 | 8 | 7 | 3.03 ± 0.15 | 2.90 | 10.33 ± 0.57 | 8.21 | 13.00 ± 1.00 | 13.39 | 12.00 ± 0.00 | 9.37 | 14.00 ± 0.00 | 16.42 |

| 29 | 8 | 14 | 2.70 ± 0.10 | 2.75 | 14.00 ± 2.00 | 13.04 | 20.00 ± 0.00 | 16.35 | 17.33 ± 1.52 | 17.99 | 20.00 ± 2.00 | 19.49 |

| 30 | 8 | 14 | 2.90 ± 0.00 | 3.03 | 13.00 ± 1.00 | 13.67 | 17.00 ± 3.00 | 14.85 | 15.00 ± 1.00 | 16.25 | 16.00 ± 1.00 | 14.08 |

| 31 | 8 | 14 | 2.50 ± 0.10 | 2.37 | 20.00 ± 0.00 | 19.30 | 19.00 ± 1.00 | 19.94 | 17.00 ± 1.00 | 18.38 | 22.00 ± 2.00 | 19.86 |

| 32 | 8 | 14 | 2.53 ± 0.15 | 2.72 | 14.00 ± 0.00 | 16.43 | 15.33 ± 1.52 | 16.35 | 16.33 ± 1.52 | 16.17 | 18.00 ± 2.00 | 16.75 |

| 33 | 8 | 21 | 2.63 ± 0.05 | 2.52 | 13.00 ± 1.00 | 16.21 | 16.00 ± 2.00 | 19.58 | 25.33 ± 3.05 | 23.04 | 26.00 ± 1.00 | 26.96 |

| 34 | 8 | 21 | 3.10 ± 0.10 | 2.90 | 16.00 ± 2.00 | 16.17 | 18.00 ± 2.00 | 18.75 | 18.67 ± 1.52 | 19.97 | 19.33 ± 0.57 | 21.94 |

| 35 | 8 | 21 | 2.30 ± 0.10 | 2.40 | 21.00 ± 1.00 | 18.97 | 24.33 ± 3.51 | 22.84 | 26.00 ± 4.00 | 23.93 | 25.00 ± 5.00 | 25.61 |

| 36 | 8 | 21 | 2.80 ± 0.10 | 2.72 | 22.67 ± 2.51 | 22.65 | 22.00 ± 2.00 | 20.69 | 26.00 ± 4.00 | 24.89 | 24.00 ± 3.60 | 22.28 |

†BT black tea, GT green tea, LT lemon verbena tea, PT peppermint tea

*Data are means of 3 replicates

pH variations in kombucha beverages

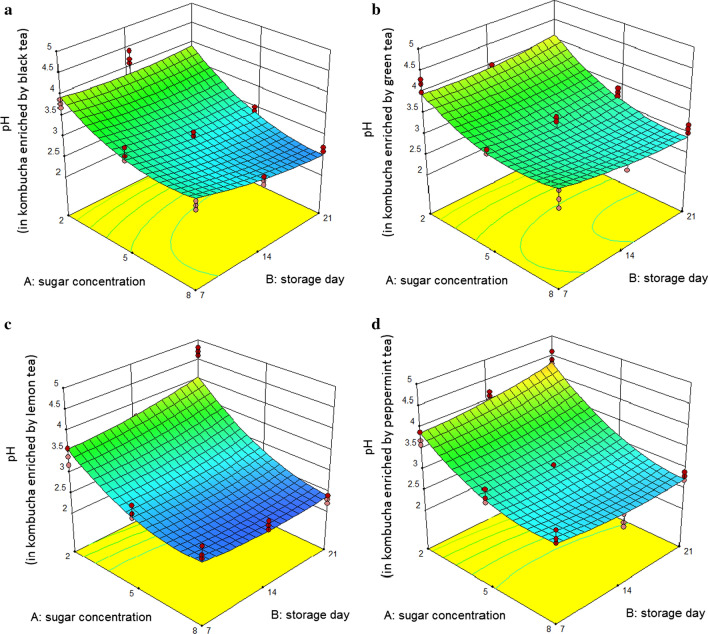

The pH data are in the range of 2.30 to 4.7 that are listed in Table 1. The minimum value is related to the kombucha sample prepared with lemon verbena at 8% sugar and fermentation time of 21 days. As shown in Table 2, the independent variables of sugar concentration and type of herbal tea have significant effects on the pH of beverages (P < 0.001). In all beverages, with increasing sugar concentration, pH decreased (Fig. 1a–d). Unlike sugar concentration, fermentation time did not affect pH variations significantly during the fermentation process. The initial pH of the Kombucha prepared with lemon verbena, was higher than the other samples, however during fermentation, the final pH of this sample more decreased than others. The interaction effects of independent variables on pH variations are also shown in Table 2 (Table 2). In the case of response analysis for the pH, lack of fit was significant, less than 0.2 difference between predicted R-sq (0.85) and Adjusted R-sq (0.83), and Adeq Precision was 21.25 (greater than 4), indicating the desirability and their navigation of these models. The prediction quadratic model for each tea was selected to describe the response surface, which was shown in Table 3 (Eq. 1–4).

Table 2.

P value and other parameters extracted from Analysis of Variance Table

| Source | pH | Escherichia coli | Shigella dysenteriae | Staphylococcus aureus | Bacillus cereus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | |||||

| Model | 1.72E−32*** | 3.72E−22*** | 1.01E−11*** | 3.94E−28*** | 8.3E−23*** |

| A: Sugar concentration | 1.33E−35*** | 1.70E−17*** | 2.7E−06*** | 1.30E−09*** | 1.11E−18*** |

| B: Fermentation time | 0.506 | 4.36E−12*** | 4.95E−05*** | 9.39E−28*** | 1.41E−17*** |

| C: Type of herbal tea | 4.19E−08*** | 2.20E−05*** | 0.24 | 2.17E−07*** | 0.18 |

| AB | 3.97E−05*** | 0.080 | 3.03E−06*** | 0.0365* | 0.79 |

| AC | 0.035* | 9.19E−07*** | 1.07E−07*** | 1.56E−07*** | 4.34E−06*** |

| BC | 0.0076** | 8.01E−07*** | 0.26 | 6.35E−05*** | 0.089 |

| A^2 | 1.18E−09*** | 0.85 | 0.319 | 0.0019** | 0.51 |

| B^2 | 0.072 | 0.136 | 0.156 | 0.136 | 0.0002*** |

| Lack of fit | 1.47E−18*** | 1.15E−14*** | 1.81E−06*** | 1.60E−05*** | 2.41E−06*** |

| R-Sq | 0.852 | 0.75 | 0.566 | 0.816 | 0.75 |

| Adj R-Sq | 0.830 | 0.71 | 0.501 | 0.78 | 0.72 |

| Pred R-Sq | 0.794 | 0.66 | 0.41 | 0.74 | 0.66 |

| Adeq Precision | 21.25 | 20.83 | 12.99 | 21.13 | 18.26 |

***P 0.001, **P 0.01, *P 0.05

Fig. 1.

Changes in pH values of Kombucha beverages (Prepared by black tea (a), green tea (b), lemon tea (c) and peppermint tea (d))

Table 3.

Final Equation of each Dependent Variable in terms of actual factors

| Dependent Variable | Type of herbal tea | Final Equation | Eq. No |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Black tea | = 5.0074–0.46018* A − 0.03948*B − 0.00734*A * B + 0.0379* A^2 + 0.0018707 * B^2 | (Eq. 1) |

| Green tea | = 4.8555 − 0.4305* A − 0.0251 *B − 0.00734* A * B + 0.0379 * A^2 + 0.0018707 * B^2 | (Eq. 2) | |

| Lemon verbena | = 4.474 − 0.5046* A − 0.00297*B − 0.00734* A*B + 0.0379* A^2 + 0.0018707 * B^2 | (Eq. 3) | |

| Peppermint | = 4.777 − 0.4935* A − 0.00615*B − 0.00734* A*B + 0.0379* A^2 + 0.0018707 * B^2 | (Eq. 4) | |

| Escherichia coli | Black tea | = − 3.5138 + 0.416* A + 0.8492*B + 0.0396*A* B + 0.013888* A^2 − 0.020408 * B^2 | (Eq. 5) |

| Green tea | = 5.85648–0.50925* A + 0.7539*B + 0.0396*A*B + 0.01388* A^2 − 0.020408 * B^2 | (Eq. 6) | |

| Lemon verbena | = 2.6342 + 1.30555* A + 0.3492 *B + 0.0396* A*B + 0.01388* A^2 − 0.020408 * B^2 | (Eq. 7) | |

| Peppermint | = − 14.088 + 1.3981* A + 1.2857*B + 0.0396* A*B + 0.01388* A^2 − 0.020408 * B^2 | (Eq. 8) | |

| Shigella dysenteriae | Black tea | = + 20.017 − 1.179 * A − 0.684 *B + 0.08134 * A*B + 0.05401* A^2 + 0.014172 * B^2 | (Eq. 9) |

| Green tea | = 24.146 − 2.0493* A − 0.5892 *B + 0.08134* A*B + 0.05401* A^2 + 0.014172 * B^2 | (Eq. 10) | |

| Lemon verbena | = 17.4614 − 0.3271* A − 0.732*B + 0.08134 * A*B + 0.05401* A^2 + 0.014172 * B^2 | (Eq. 11) | |

| Peppermint | = 18.683 − 1.2901* A − 0.525 *B + 0.081349* A*B + 0.05401* A^2 + 0.014172 * B^2 | (Eq. 12) | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Black tea | = 1.625 − 0.3148* A + 0.4027 *B − 0.04563* A*B + 0.2268* A^2 + 0.019558 * B^2 | (Eq. 13) |

| Green tea | = 17.3657 − 2.166* A + 0.2123*B − 0.04563* A*B + 0.22685* A^2 + 0.019558* B^2 | (Eq. 14) | |

| Lemon verbena | = 0.56944 − 0.259* A + 0.4742 *B − 0.04563* A*B 0.2268 * A^2 + 0.019558 * B^2 | (Eq. 15) | |

| Peppermint | = − 6.33796 − 0.462* A + 0.9265 *B − 0.04563* A*B + 0.2268* A^2 + 0.019558 * B^2 | (Eq. 16) | |

| Bacillus cereus | Black tea | = + 1.4876 + 2.725 * A − 0.7401 *B − 0.00595 * A*B − 0.04939* A^2 + 0.053005 * B^2 | (Eq. 17) |

| Green tea | = 10.7098 + 0.7993* A − 0.6845 *B − 0.00595 * A*B − 0.04939* A^2 + 0.053005* B^2 | (Eq. 18) | |

| Lemon verbena | = 7.08024 + 2.503* A − 0.98611*B − 0.00595 * A*B − 0.04938* A^2 + 0.053005 * B^2 | (Eq. 19) | |

| Peppermint | = 7.3765 + 2.1327*A − 1.01786* B − 0.00595* A * B − 0.04938* A^2 + 0.053005* B^2 | (Eq. 20) |

Effect of independent variables on the antibacterial activity of kombucha beverages against E. coli

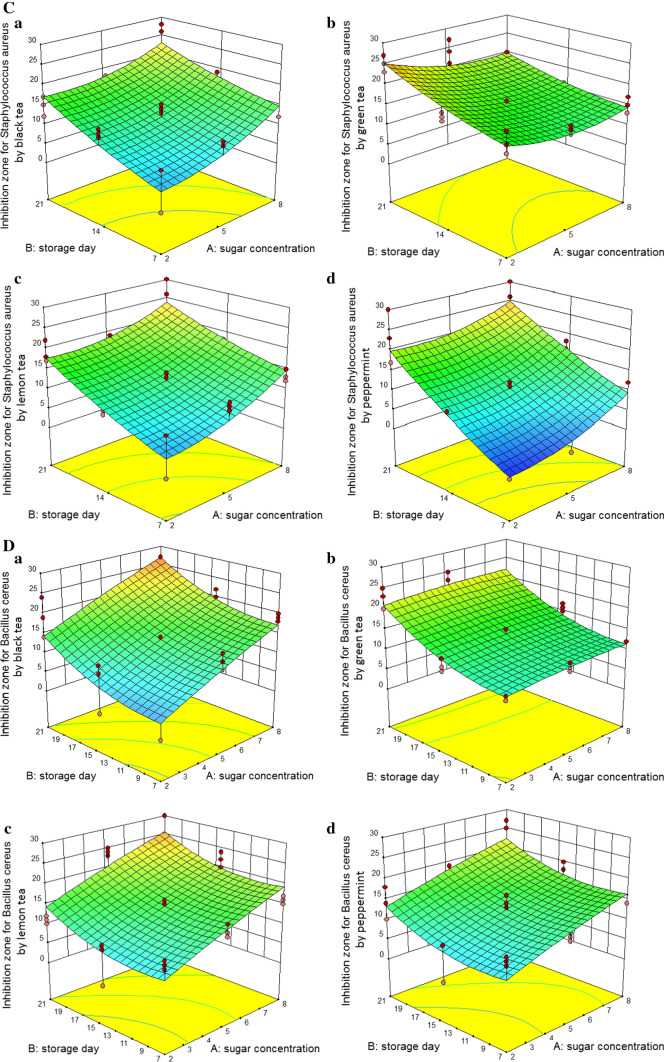

The actual data in Table 1 shows that the maximum inhibition zone diameter about E. coli is related to the kombucha prepared with peppermint at 8% sugar concentration and fermentation of 21 days. The analysis of variance (Table 2) showed that the changes in sugar concentration, fermentation time, and type of herbal tea had significant effects on the inhibition zone of E. coli (P < 0.001). In other words, an increasing in sugar concentration and fermentation time led to more antibacterial activity against E. coli (Fig. 2A; a–d). The antibacterial activity in Kombucha prepared with peppermint was more than the other herbal teas (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Inhibition zone of bacteria tested (A: E. coli B: S. dysenteriae C: S. aureus D: B. cereus) in Kombucha beverages (Prepared by black tea (a), green tea (b), lemon tea (c) and peppermint tea (d))

The interactions of sugar concentration with type of herbal tea and fermentation time with type of herbal tea had also significant effects (P < 0.001) (Table 2).

In the case of response analysis for the inhibition zone for E. coli, lack of fit is significant, due to the difference between predicted R-sq (0.75) and Adjusted R-sq (0.71) is less than 0.2 and Adeq Precision equals 20.83 (greater than 4), indicates the model's desirability and navigation (Table 2). The prediction quadratic model for each tea was selected to describe the response surface, which was shown in Table 3 (Eqs. 5–8).

Effect of independent variables on the antibacterial activity of Kombucha beverages against S. dysenteriae

The maximum inhibition zone diameter S. dysenteriae with 24.33 mm belongs to the kombucha beverage with the basis of lemon verbena at 8% sugar and fermentation time of 21 days (Table 1). As shown in Table 2, variables of sugar concentration and fermentation time had significant effects on the antibacterial activity of kombucha beverages against S. dysenteriae (P < 0.001). Furthermore, the interaction effect of sugar concentration with fermentation time and sugar concentration with type of herbal tea had significant effects on the antibacterial activity of fermented beverages against S. dysenteriae (P < 0.001). In all beverages, an increasing inhibition zone was observed with increasing sugar concentration, (Fig. 2B; a–d). The Kombucha beverage prepared with lemon verbena has shown more antibacterial activity against S. dysenteriae compared to other fermented beverages (Fig. 2B).

The information provided in the software indicates that Adeq Precision values greater than 4 is desirable, since the results of ANOVA show the Adeq Precision 12.99, also the predicted R-sq is close to the Adjusted R-sq (the difference is less than 0.2), that indicates the model's desirability and navigation (Table 2). The prediction quadratic model for each tea was selected to describe the response surface, which was shown in Table 3 (Eqs. 9–12).

Effect of independent variables on the antibacterial activity of Kombucha beverages against S. aureus

The highest diameter of inhibition zone of S. aureus, at 26 mm, is related to kombucha beverages prepared with peppermint and lemon verbena at sugar concentration of 8% and fermentation of 21 days (Table 1). The analysis of variance (Table 2) showed that all independent variables including sugar concentration, fermentation time, and type of tea have significant effects on the antibacterial activity of Kombucha beverages against S. aureus (P < 0.001).

Additionally, the interaction effects of independent variables on the inhibition zone diameter of S. aureus are shown in Table 2. Figure 2C (a–d) shows the positive effect of sugar concentration, fermentation time, and their interaction on the antibacterial activity of beverages prepared against S. aureus (except for green tea).

Due to the difference between predicted R-sq (0.81) and Adjusted R-sq (0.78) is less than 0.2 and Adeq Precision equals 21.13 (greater than 4), indicates the model's desirability and them navigation (Table 2). The quadratic prediction model for each tea was selected to describe the response surface, which was shown in Table 3 (Eqs. 13–16).

Effect of independent variables on the antibacterial activity of Kombucha beverages against B. cereus

The actual data in Table 1 shows that the highest diameter of inhibition zone of B. cereus belongs to kombucha prepared with black tea at sugar concentration of 8% and fermentation time of 21 days (Table 1). The results of the analysis of variance showed that sugar concentration and fermentation time had significant effects on the antibacterial activity of kombucha beverages against B. cereus (P < 0.001), unlike, type of herbal tea had not significant effect on the antibacterial activity of beverages (Table 2).

The predicted R-sq is close to the Adjusted R-sq (The difference is less than 0.2) which indicates a high degree of correlation between the observed and predicted values. Also, Adeq Precision equals greater than 4, indicates the desirability and navigation of models (Table 2). The quadratic prediction model for each tea was selected to describe the response surface, which was shown in Table 3 (Eqs. 17–20).

Prediction of fermentation conditions to achieve the best antibacterial activity of Kombucha beverages

Several optimum fermentation conditions for preparing Kombucha beverages were determined to satisfy the criteria. In this study, second order polynomial models were used for each response to determine the specified optimum condition. In this study, the optimization was applied for selected ranges of sugar concentration, fermentation time, and type of herbal tea as 2–8%, 7–21 day, and green tea, black tea, lemon verbena, and peppermint tea, respectively. By desirability function method, the best solution for detecting suitable fermentation conditions was obtained for the optimum covering criteria with the maximum desirability value (Table 4).

Table 4.

Individual preparation (fermentation conditions) for Kombucha beverages in order to achieve the maximum inhibition zone of each bacteria

| Bacteria | Sugar concentration (%) | Fermentation time | Type of herbal tea | pH | Inhibition zone (mm) | Desirability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shigella dysenteriae | 8.0 | 21 | Lemon verbena | 2.40 | 23.00 | 0.729 |

| Escherichia coli | 8.0 | 21 | Peppermint | 2.72 | 23.00 | 0.906 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 2.0 | 21 | Green tea | 4.13 | 25.00 | 0.837 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 8.0 | 21 | Peppermint | 2.72 | 25.00 | 0.835 |

| Bacillus cereus | 8.0 | 21 | Black tea | 2.52 | 27.00 | 0.899 |

The highest antibacterial activity against B. cereus with the inhibition zone diameter of 27 mm was observed in fermented beverage prepared with black tea at the sugar concentration of 8% and fermentation time of 21 days. The most antibacterial activity against S. aureus (inhibition zone of 25 mm) was observed in kombucha beverages prepared with green tea and peppermint for fermentation time of 21 days, at 2% and 8% sugar, respectively.

The most antibacterial activity against E. coli (diameter of the inhibition zone of 23 mm), was seen in the kombucha beverage prepared with peppermint, the sugar concentration of 8% and the fermentation time of 21 days.

Finally, the most antibacterial activity against the S. dysenteriae, are seen in kombucha beverage prepared with lemon verbena, sugar concentration of 8%, and fermentation time of 21 days.

Discussion

The results of this study showed significant antibacterial activity of kombucha beverages. Fermentation time and sugar concentration had a significant effect on the antibacterial activity of kombucha beverages. The type of herbal tea had a significant effect on the antibacterial activity of kombucha beverages against E. coli and S. aureus (Table 2).

There are many reports about the compounds responsible for antimicrobial activity.

Numerous studies have suggested the role of acetic acid in the antibacterial activity of kombucha fermented beverages (Greenwalt et al. 1998; Blanc 1996; Velicanski et al. 2014; Steinkraus et al. 1996; Cetojevic Simin et al. 2008; Sreeramulu et al. 2001).

The antimicrobial effect of acetic acid has been attributed to its ability to decrease pH both in intra- and extracellular conditions and therefore to altering the cell membrane's transportation and integrity, as well as enzymatic activity, and even precipitating cytoplasmic proteins (Ryssel et al. 2009). An increase in the hydrogen-ions resulted in decreasing the thermal death points of the bacteria. The toxicity of acetic acid for various microorganisms is not confined to the hydrogen-ion concentration alone, because its lethal activity is seen at comparatively high pH values also, therefore it seems to be a function of the undissociated acetic acid molecule (Leon et al. 1993).

Sreeramulu et al. (2000) and Battikh et al. (2013) have demonstrated that apart from acetic acid or other organic acids, other biologically active compounds such as polyphenols, proteins, bacteriocins, enzymes may also contribute to the antimicrobial activity of Kombucha.

Catechin is one of the predominant polyphenols found in tea which has a high antibacterial potential (Dufresne and Farnworth 2000). Polyphenols of catechin and isorhamnetin have been detected as the major antibacterial compounds of Kombucha which belong to the flavan-3-ol and flavonol classes of flavonoids, respectively (Bhattacharya et al. 2016).

The presence of hydroxylation at positions 5 and 7 of the A ring and position 3 of the C ring contribute to the antibacterial activity of these polyphenolic compounds. The free hydroxyl group(s) in the B ring of the flavonoids are also thought to be responsible for their antibacterial activity (Cushnie and Lamb 2011; Rojas et al. 1992).

Bacteriocins, enzymes, and other protein compounds produced by bacteria have role in the antimicrobial activity of this beverage. Bacteriocins are proteinaceous compounds that exhibit bactericidal activity against species closely related to the producer strain. Bacteriocins alter the membrane potential by corrupting the potassium ion and ATP and cause cell failure to balance intracellular pH (Sezer and Guven 2009).

Differences in pH values can be due to the difference in the chemical compounds of black tea, green tea, peppermint, and lemon verbena (Battikh et al. 2012). It was also reported that the reduction in pH can be attributed to the formation of organic acids by acetic acid bacteria and the interactions of minerals and herbal compounds of tea and fungus (Battikh et al. 2012; Malbasa et al. 2011; Talawat et al. 2006).

Generally, sugar concentration had a significant effect on antibacterial activity of kombucha beverages (Table 2) and the most antibacterial activity was observed in beverages prepared with a concentration of 8% sugar (Table 4). Generally, the increase of sugar concentration causes elevated organics acids production and consequently, more antimicrobial activity (Santos et al. 2009).

The sugar in tea is metabolized to glucose and fructose by the microorganisms in Kombucha. At first, Glucose was converted by yeasts into ethanol and carbon dioxide and then ethanol was changed into acetic acid, and other organic acids by acetic acid bacteria (the antibacterial activity of these beverages are attributed to the organic acids). Considering the need of microorganisms in Kombucha for a nutrition source (sugar), it is concluded that increasing antibacterial activity was associated with increasing sugar concentration (Haizhen et al. 2008; Jayabalan et al. 2014; Sreeramulu et al. 2000).

Fermentation time had a significant effect on the antibacterial activity of kombucha beverages (Table 2) and all tested fermented beverages showed the most antibacterial activity during the 21 days fermentation time (Table 4). Increased antibacterial activity of kombucha beverages along with increased fermentation time has been reported in several studies (Battikh et al. 2012; Vohra et al. 2019).

The fermentation time affects compounds of kombucha beverage and its biological activities including antibacterial activity (Wolfe and Dutton 2015; Villarreal Soto et al. 2018; Chu and Chen 2006). Of course, antibacterial activity may occur depending on the type of bacteria at different fermentation times (Villarreal Soto et al. 2018).

One of the most important mechanisms for the antibacterial activity of kombucha beverage is the production of organic acids, especially acetic acid during fermentation. Numerous studies have suggested the role of acetic acid in the antibacterial activity of kombucha fermented beverages (Greenwalt et al. 1998; Blanc 1996; Velicanski et al. 2014; Steinkraus et al. 1996; Cetojevic Simin et al. 2008; Sreeramulu et al. 2001). Also, an increase of antibacterial activity has been reported along with the production of acetic acid and other organic acids in higher fermentation times (Sreeramulu et al. 2001; Talawat et al. 2006). This is confirmed by the decreasing trend pH in Kombucha samples of the present study with increasing fermentation time. Therefore, the antibacterial activity of Kombucha samples can be attributed to the production of organic acids, especially acetic acid that its levels increases in beverages with increasing of fermentation time.

The Kombucha prepared with the basis of lemon verbena showed the most antibacterial activity against S. dysenteriae. Antimicrobial activity of the Kombucha prepared with lemon verbena has also been reported (Batikh et al. 2012). In addition to the role of acetic acid and organic acids, the presence of antibacterial compounds such as phenylpropanoid with verbascoside (the most abundant compounds) and iridoid, verbenalin, along with flavonoids, luteolin, and aryenine, in the plant of lemon verbena can be considered as an effective determinant (Bilia et al. 2008).

Regarding the remarkable antibacterial activity of the Kombucha beverage prepared with green tea against S. aureus, this effect may be due to natural compounds in green tea such as catechins including epigallocatechin galate, epigallocatechin, epicatechin gallate, epicatechin and galocatechin and other compounds (An et al. 2004; Noormandi and Dabaghzadeh, 2015).

In a study by Yadegarnia et al. (2006), while proving the antibacterial activity of the essential oil of peppermint leaves against S. aureus and E. coli, that the most important compounds of essential oil of peppermint leaves were introduced such as alphaterpinen, isomenton, trans-caroeol, beta-cariophylline, and piprerttitinone oxide.

The more sensitivity of Gram-positive bacteria, B. cereus, and S. aureus in comparison with gram-negative bacteria, E. coli, and S. dysenteriae, to Kombucha beverages, is demonstrated in Table 4 and Fig. 2. These results were similar to the findings of Battikh et al. (2012). Additionally, Arakawa et al. (2004) reported more sensitivity of gram-positive bacteria in comparison with gram-negative bacteria, to catechins (polyphenols).

The resistance of the cell walls of the gram-negative bacteria to inhibitors such as antimicrobial chemicals, herbal compounds, extracts, essential oils, and antibiotics is proportional to the lower permeability of the outer membrane and the presence of the cell wall lipopolysaccharide layer, and to the periplasmic space of these bacteria that limits the entry of antimicrobial agents into the bacterial cell (Burt, 2004; Hayouni et al. 2007; Russel, 1991).

Conclusion

Fermentation time and sugar concentration showed a significant effect on antibacterial activity of kombucha beverages. To achieve the most antibacterial activity of kombucha beverage against B. cereus, preparation of the beverage with black tea at sugar concentration of 8%, and fermentation time of 21 days was recommended. The most antibacterial activity against S. aureus was obtained by the preparation of beverages with green tea and peppermint with fermentation time of 21 days and at the levels of 2% and 8%, of sugar concentrations, respectively. Also, the preparation of kombucha with peppermint and lemon verbena at 8% sugar and 21 days of fermentation were recommended to achieve the most antibacterial activity against E. coli and S. dysenteriae, respectively.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they had no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Fateme Valiyan, Email: s.valiyan@yahoo.com.

Hadi Koohsari, Email: hadikoohsari@yahoo.com.

Abolfazl Fadavi, Email: fadavi2000@yahoo.com.

References

- An BJ, Kwak JH, Son JH. Biological and anti-microbial activity of irradiated green tea polyphenols. Food Chem. 2004;88:549–555. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.01.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Battikh H, Bakhrouf A, Ammarb E. Antimicrobial effect of Kombucha analogues. Food Sci Technol. 2012;47:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2011.12.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Battikh H, Chaieb K, Bakhrouf A, Ammar E. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of black and green Kombucha teas. J Food Biochem. 2013;27:231–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4514.2011.00629.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya D, Bhattacharya S, Manti Patra M, Chakravorty S, Sarkar S, Chakraborty W, Koley H, Gachhui R. Antibacterial activity of polyphenolic fraction of Kombucha against enteric bacterial pathogens. Curr Microbiol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00284-016-1136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilia AR, Giomi M, Innocenti M, Gallori S, Vincieri FF. HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS analysis the constituents of aqueous preparations of verbena and lemon verbena and evaluation of the antioxidant activity. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2008;13:463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc PJ. Characterization of the tea fungus metabolites. Biotechnol Lett. 1996;18:139–142. doi: 10.1007/BF00128667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burt S. Essential oils: their antibacterial properties and potential application in foods-a review. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;94:223–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetojevic Simin DD, Bogdanovic GM, Cvetkovic DD, Velicanski AS. Antiproliferative and antimicrobial activity of traditional Kombucha and Satureja montana L. Kombucha J BUON. 2008;13:395–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu SC, Chen C. Effects of origins and fermentation time on the antioxidant activities of Kombucha. Food Chem. 2006;98:502–507. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.05.080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cushnie TPT, Lamb AJ. Recent advances in understanding the antibacterial properties of flavonoids. Int J Antimicrob Ag. 2011;38:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufresne C, Farnworth E. Tea, Kombucha, and health: a review. Food Res Int. 2000;33:409–421. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00067-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwalt CJ, Ledford RA, Steinkraus KH. Determination and characterization of the antimicrobial activity of the fermented tea Kombucha. Lebensm Wiss Technol. 1998;31:291–296. doi: 10.1006/fstl.1997.0354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haizhen M, Yang Z, Zongmao C. Microbial fermented tea- e potential source of natural food preservatives. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2008;19:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2007.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayouni EA, Abedrabba M, Bouix M, Hamdi M. The effects of solvents and extraction method on the phenolic contents and biological activities in vitro of Tunisian Quercus coccifera L. and Juniperus phoenicea L. fruit extracts. Food Chem. 2007;105:1126–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson JL. Introduction to wine laboratory practices and procedures. New York: Springer; 2006. pp. 257–277. [Google Scholar]

- Jayabalan R, Malbasa RV, Loncar ES, Vitas JS, Sathishkumar M. A Review on Kombucha tea—microbiology, composition, fermentation, beneficial effects, toxicity, and tea fungus. Compr Rev Food Sci F. 2014;10:538–550. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayabalan R, Marimuthu S, Swaminathan K. Changes in content of organic acids and tea polyphenols during kombucha tea fermentation. Food Chem. 2007;102:392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.05.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leon SP, Inove N, Shinano H. Effect of acetic and citric acids on the growth and activity (VB-N) of Pseudomonas sp. and Moraxella sp. Bull Fac Fish Hokkaido Univ. 1993;44:80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Malbasa RV, Loncar ES, Vitas JS, Canadanovic-Brunet JM. Influence of starter cultures on the antioxidant activity of kombucha beverage. Food Chem. 2011;127:1727–1731. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.02.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noormandi A, Dabaghzadeh F. Effects of green tea on Escherichia coli as a uropathogen. J Tradit Compl Med. 2015;5:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic SE, Loncar ES, Malbasa RV, Verac RM. Biosynthesis of glucuronic acid by means of tea fungus. Nahrung. 2000;44:138–139. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3803(20000301)44:2<138::AID-FOOD138>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas A, Hernandez L, Pereda-Miranda R, Mata R. Screening for antimicrobial activity of crude drug extracts and pure natural products from Mexican medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 1992;35:275–283. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(92)90025-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russel AD. Mechanisms of bacterial resistance to non-antibiotics: food additives and food pharmaceutical preservatives. J Appl Bacteriol. 1991;71:191–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1991.tb04447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryssel H, Kloeters O, Germann G, Shafer TH, Wiedemann G, Oehlbauer M. The antimicrobial effect of acetic acid-an alternative to common local antiseptics. Burns. 2009;35:695–700. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos RJ, Jr, Batista RA, Rodrigues SA, Filho LX, Lima AS. Antimicrobial activity of broth fermented with kombucha colonies. J Microb Biochem Technol. 2009;1:072–078. doi: 10.4172/1948-5948.1000014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sezer C, Guven A. Investigation of bacteriocin production capability of lactic acid bacteria ısolated from foods. Kafkas Univ Vet Fak Derg. 2009;15:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sreeramulu G, Zhu Y, Knol W. Characterization of antimicrobial activity in Kombucha fermentation. Acta Biotechnol. 2001;21:49–56. doi: 10.1002/1521-3846(200102)21:13.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sreeramulu G, Zhu Y, Knol W. Kombucha fermentation and its antimicrobial activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:2589–2594. doi: 10.1021/jf991333m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinkraus KH, Shapiro KB, Hotchkiss JH, Mortlock RP. Investigations into the antibiotic activity of tea fungus/kombucha beverage. Acta Biotechnol. 1996;16:199–205. doi: 10.1002/abio.370160219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talawat S, Ahantharik P, Laohawiwattanakul S, Premsuk A, Ratanapo S. Efficacy of fermented teas in antibacterial activity. Kasetsart J (Nat Sci) 2006;40:925–933. [Google Scholar]

- Velicanski AS, Cvetkovic DD, Markov SL, Tumbas Saponjac VT, Vulic JJ. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of the beverage obtained by fermentation of sweetened lemon balm (Melissa offi cinalis L.) tea with symbiotic consortium of bacteria and yeasts. Food Technol Biotechnol. 2014;52:420–429. doi: 10.17113/b.52.04.14.3611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal Soto SD, Beaufort S, Bouajila J, Souchard JP, Taillandier P. Understanding kombucha tea fermentation: a review. J Food Sci. 2018;83:580–588. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohra BM, Fazry S, Sairi F, Babul-Airianah O. Effects of medium variation and fermentation time on the antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of Kombucha. Mal J Fund Appl Sci. 2019;2019:298–302. doi: 10.11113/mjfas.v15n2-1.1536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein MP, Patel JB, Burnham CA, Campeau S, Conville PS, Doern C, Eliopoulos GM, Galas MF, Humphries RM, Jenkins SG, Kircher SM, Lewis JS, Limbago B, Mathers AJ, Mazzulli T, Munro SD, Smith de Danies MO, Patel R, Richter SS, Satlin M, Swenson JM, Wong A, Wang WF, Zimmer BL (2018) Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. In: Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute, M07, 11 ed, Wayne, 19087, USA Pennsylvania, pp 15–35

- Wolfe BE, Dutton RJ. Fermented foods as experimentally tractable microbial ecosystems. Cell. 2015;161:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadegarinia D, Gachkar L, Rezaei MB, Taghizadeh M, Astaneh SA, Rasooli I. Biochemical activities of Iranian Mentha piperita L. and Myrtus communis L. essential oils. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:1249–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.