Abstract

Background:

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is associated with poor health outcomes, including cervical cancer. Racial/ethnic minority populations experience poor health outcomes associated with HPV at higher rates. A vaccine is available to protect against HPV infections and prevent HPV-related sequelae; however, vaccination rates have remained low in the United States (U.S.) population. Thus, there is an urgent need to increase HPV vaccination rate. Moreover, little is known about barriers to HPV vaccination in racial/ethnic minority groups. This paper highlights the most recent findings on barriers experienced by these groups.

Methods:

The PubMed database was searched on July 30, 2020 for peer-reviewed articles and abstracts that had been published in English from July 2010 to July 2020 and covered racial/ethnic disparities in HPV vaccination.

Results:

Similar findings were observed among the articles reviewed. The low HPV vaccination initiation and completion rates among racial/ethnic minority populations were found to be associated with lack of provider recommendations, inadequate knowledge and awareness of HPV and HPV vaccination, medical mistrust, and safety concerns.

Conclusions:

Provider recommendations and accurate distribution of information must be increased and targeted to racial/ethnic minority populations in order to bolster the rate of vaccine uptake. To effectively target these communities, multi-level interventions need to be established. Further, research to understand the barriers that may affect unvaccinated adults in the catch-up age range, including males, may be beneficial, as majority of the previous studies focused on either parents of adolescents or women.

Keywords: HPV, human papillomavirus, health disparities, racial/ethnic minority

Background

Infecting nearly 80 million people in the United States (U.S.), Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is currently the most common sexually transmitted infection. [1] HPV infection can cause genital warts, anal cancer, and cervical cancer as well as many other sequelae. [1] In 2006, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Gardasil vaccination to protect against HPV infections. [2] The U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) currently recommends that all boys and girls aged 11 and 12 should be vaccinated, and persons who were not vaccinated in adolescence should be vaccinated anytime to age 26. [2] In 2018, the FDA approved an extension to the acceptable age for the catch-up vaccination to adults through the age of 45. [3] Despite CDC recommendations, less than 50% of females and 38% of males in the U.S. have completed the HPV vaccination. [4]

Racial/ethnic minority adult populations, specifically Black/African Americans and Latino/as, disproportionally carry the burden of poor HPV-related outcomes. Though studies have shown that racial/ethnic minority populations tend to have higher vaccine initiation than their White counterparts, there may be lower completion rates for additional vaccine doses. [5] Further, the barriers faced by racial/ethnic minority groups may differ significantly from White individuals. While health disparities regarding vaccine initiation and completion have been observed among Black/African Americans and Hispanics, specific barriers to explain these disparities have not been reviewed in racial/ethnic minority groups. Thus, this paper synthesizes available data collected over the past ten years to assess barriers faced by racial/ethnic minority populations on HPV vaccination. This information is critical because understanding these barriers will enable public health officials to target racial/ethnic minority populations with resources to increase HPV vaccination coverage, which would in turn decrease the burden of poor HPV-related outcomes in these vulnerable populations.

Methods

The PubMed database, which includes Ovid Medline, was used to identify peer-reviewed articles and abstracts that reported on health disparities related to HPV vaccination in racial/ethnic minority populations. The keyword search comprised a combination of terms “human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine barriers”. The search was conducted on July 30, 2020. Studies conducted in the U.S. and published in English language over the past ten years from 2010 to July 2020, and primarily focused on HPV and HPV vaccination were included. However, studies that were not conducted in the U.S. or focused solely on cervical cancer screening were excluded. Further, studies that did not examine racial/ethnic disparities were also excluded. To preserve the congruency of this review, systematic review articles and intervention studies were not included, but are referenced where applicable. Studies with qualitative outcome measures were included.

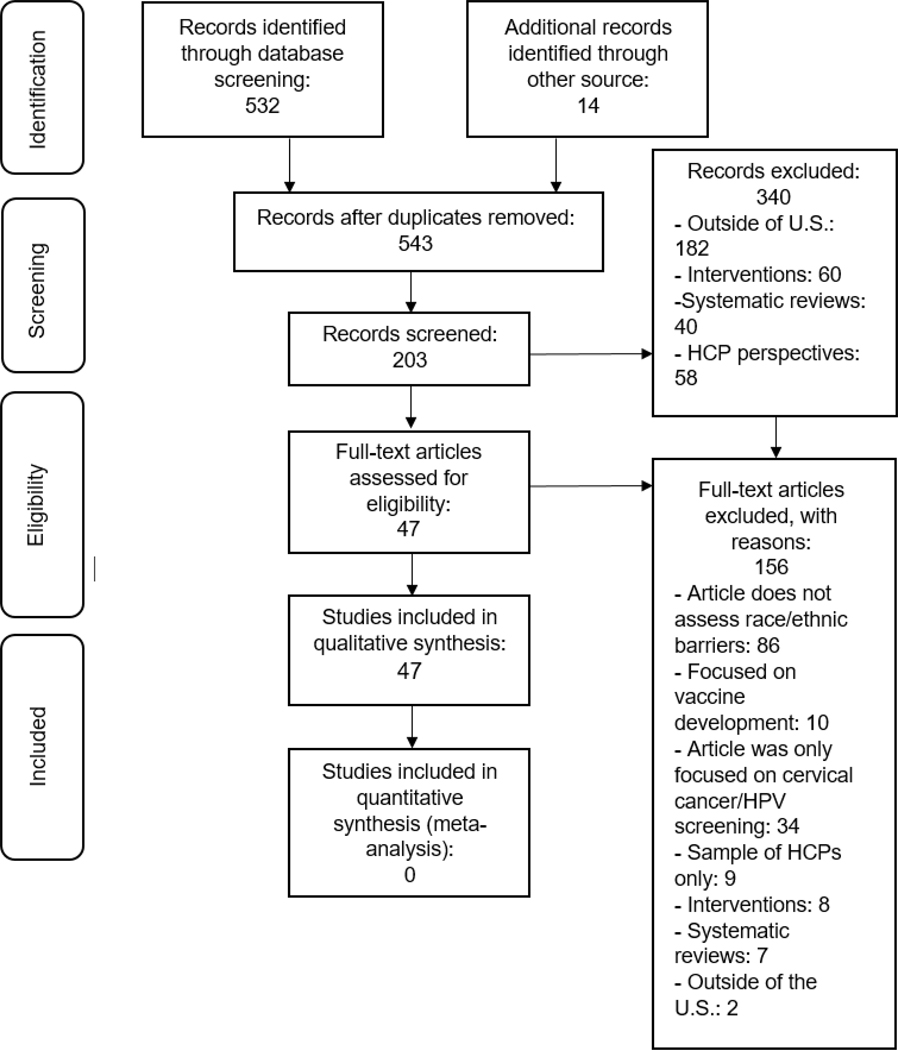

The study screening process was conducted independently and is presented in Figure 1. Initially, 532 articles were retrieved from the database and 14 articles were retrieved from keyword suggestions in PubMed. All studies were then transferred to Excel. Three duplicates and 496 other studies were eliminated due to the exclusion criteria, leaving 47 studies used in this systematic literature review. The selected articles utilized cross-sectional surveys and interviews, as well as focus groups, thus, each individual study may be at risk of inherent temporal bias. The populations covered in these articles were mostly female and consisted of racial/ethnic minority groups such as Hispanics/Latinos/as, Blacks/African Americans, Asians, and non-U.S.-born individuals, as well as Whites.

Figure. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Table 1 presents a summary of the studies included in this review. Forty-six articles utilized a cross-sectional study design and collected data with questionnaires and interviews measuring outcomes with quantitative and qualitative methods, and one article utilized a longitudinal study design. Twenty-five studies gathered data from parents of adolescents, while nine studies gathered information from college-aged young adults and fourteen were focused on adults. Overall, thirty-three studies had a relatively large sample size (N>100), and fourteen of the studies had smaller sample sizes (N<100). Specified data collection dates for these studies ranged from 2006 to 2017.

Table 1.

Summary of Included Studies Evaluating Barriers to HPV Vaccine Uptake among Racial/Ethnic Minorities (N=47)

| Source | Study Design | Data collection dates | Participants, n | Age Range (years) | Inclusion Criteria | Method of Data Collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blake et al, 2015 | Cross- sectional | September- December 2013 | 3185 participants (males=1197, females=1906) | 18+ | Men and women 18 years or older who were HINTS 4 cycle 3 participants in 2013 | HINTS survey |

| McBride et al, 2018 | Cross- sectional | August- November 2014 | 3185 participants (males=1197, females=1906) | 18+ | Men and women 18 years or older who were HINTS 4 cycle 4 participants in 2014 | HINTS survey |

| Boakye et al, 2017 | Cross- sectional | September- December 2013 and August-November 2014 | 6862 participants (males=2621, females=4090) | 18+ | Men and women 18 years or older who were HINTS 4 cycle 3 and cycle 4 participants in 2013 or 2014 | HINTS survey |

| Niccolai et al, 2016 | Cross- sectional | May 2013- January 2014 | 38 participants (parents=33, grandparents=4, step- parents=1) | Parents of children 10–18 years | English- and Spanish- speaking parents of children 10–18 years who were seen in an urban hospital-based outpatient clinic in Northeastern US | Semi-structured recorded qualitative survey |

| Kim et al, 2015 | Qualitative cross-sectional data from parent RCT | 2010–2012 | 26 women (community health workers=14, Korean American study participants=12) | 21–65 | Met inclusion criteria of parent RCT: aged 21–65, self- identified Korean female, no mammogram and/or Pap test within the last two years, able to read or write either Korean or English, willing to offer written consent AND were a participant in the control group of the RCT and willing to participate in focus group | Focus group qualitative data |

| Davlin et al, 2015 | Cross- sectional | September 2011- September 2012 | 638 women | Women who had at least one child between | Women who sought care at one of three regional maternal child health program clinics at UTMB between sept 2011- | Self-administered questionnaire |

| ages 9–17 years | 2012 who had at least one child between ages 9–17 years | |||||

| Glenn et al, 2015 | Cross- sectional | January 2009- January 2010 | 490 participants | Primary medical decision maker for a girl aged 9–18 years | Women who called the UCLA office of women’s health education hotline between ages 18–65 who spoke either English, Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, Korean, or Armenian, and were the primary medical decision maker for a girl 9–18 years of age | Telephone survey instrument |

| Ashing et al, 2017 | Secondary data analysis of cross-sectional data | 2009–2011 | 383 women (African born in US=129, African immigrants=53, Hispanic born in US=57, Hispanic immigrants=144) | 18+ | Women 18+ who self- identified as Black/African American or Hispanic/Latina, had no history of cancer, and had at least a 4th grade fluency in English and/or Spanish who signed informed consent | Mailed self- administered study questionnaire |

| Hernandez et al, 2017 | Cross- sectional | November- December 2011 | 187 women | 18+ | Women who attend a large public university in southeast US who self-reported as Hispanic/Latina and had not received at least one dose of HPV vaccine | Web-based self- administered survey |

| Romaguera et al, 2015 | Population- based cross- sectional | December 2010- April 2013 | 566 women | 16–64 | Women aged 16–64 who were residents of San Juan, Puerto Rico, sexually active, not pregnant, not HIV-positive, and not physically or cognitively impaired | Face-to-face interviews and computer-assisted interviews |

| Kolar et al, 2015 | Cross- sectional | November- December 2011 | 711 women | 18+ | Women who attend a public university in Southeast US who were on file at the university’s registrar’s office and responded to the web- based survey | Web-based survey |

| O’Leary et al, 2018 | Cross- sectional | August-October 2013 | 244 parents | Parents of girls aged 12–15 years | Parents of girls aged 12–15 years who were in the Denver Health immunization registry, spoke English or Spanish, and responded to the mailed survey | Qualitative mailed surveys |

| Kashani et al, 2019 | Retrospective data collection; Longitudinal analysis | 2006–2015 | 4722 American Indian/Alaskan Native and 679,787 non-Hispanic White adolescents | 9–18 years | American Indian and non- Hispanic White Michigan residents who were born in Michigan between 1 January 1997 and 5 July 2004 and were in Michigan’s immunization information system | Chart review |

| Dela Cruz et al, 2017 | Cross- sectional | October 2013- January 2014 | 20 parents | Parents of children 11–18 years | Parents of children between 11 to 18 years old who were the parent or guardian who takes their child(ren) to get vaccinated, and lived in Hawai’i. | Face-to-face interviews |

| Sledge, 2015 | Cross- sectional | September 2011- May 2012 | 68 African American male college students | 18–26 years | African American male students in St. Louis, Missouri between the ages of 18–26 | Web-based survey |

| Victory et al, 2019 | Cross- sectional | 2017 | 622 parents | Parents of children 4th–12th grade | Parents of children in 4th–12th grade in Rio Grande Independent School District | Survey |

| Galbraith-Gyan et al, 2018 | Cross- sectional | June 2014- October 2015 | 30 parents and 34 daughters | Parents of daughters aged 12–17 years; girls aged 12–17 years | African-American or Black parents of a 12–17-year-old girl; 12–17 year old girls | Face-to-face semi- structured interviews |

| Kepka et al, 2015 | Cross- sectional | August-October 2013 | 67 parents | Parents of children aged 11–17 years | Spanish-speaking Latino parents/guardians of children aged 11–17 years in Utah | Self-administered survey |

| Lechuga et al, 2016 | Cross- sectional | October 2010- February 2011 | 296 women | 18+ | Woman aged 18 years or older who self-identified as Hispanic and self-reported being a resident of Dane County | Telephone survey instrument |

| Guerry et al, 2011 | Cross- sectional | October 2007- June 2008 | 509 parents | Parents of children aged 11–18 years | Parents/guardians of children aged 11–18 years who attended public middle and high schools in economically disadvantaged populations in Los Angeles County. | Telephone survey instrument |

| Btoush et al, 2019 | Cross- sectional | January- December 2015 | 132 mothers | Mothers of children aged 11–18 years | Latinas aged 18 years or older who had at least one child aged 11–18 years who attended a multi-site community health center or a clinic of an urban community hospital in the Newark/Elizabeth area in New Jersey | Focus group qualitative data |

| Bastani et al, 2011 | Cross- sectional | January- November 2009 | 490 mothers | Mothers of daughters aged 9–18 years | Women 18 years of age or older who was the primary medical decision-maker for a girl 9 to 18 years old | Telephone survey instrument |

| Pierce et al, 2013 | Cross- sectional | May 2008-April 2009 | 242 parents | Parents of girls aged 11–12 years | Parents of girls aged 11–12 years who had been since at a University of Virginia medical practice during the data collection timeframe | Telephone survey instrument |

| Cheruvu et al, 2017 | Cross- sectional | 2008–2012 | 23,722 parents | Parents of females aged 13–17 years | Parents of girls aged 13–17 years who had not received the HPV vaccine series and who completed the National Immunization Survey - Teen from 2008–2012 | Survey |

| Kepka et al, 2018 | Cross- sectional | May 2014- October 2014; October 2014- February 2015 | 228 parents | Parents of children aged 11–17 years | Adult parents of teens aged 11–17 years who were vaccination decision-makers for their children. | Self-administered survey |

| Sriram et al, 2019 | Cross- sectional | 2016 | 43,071 parents | Parents of children aged 13–17 years | Parents or guardians of teens 13–17 years old who completed the National Immunization Survey- Teen in 2016. | Survey |

| Dela Cruz et al, 2018 | Cross- sectional | 2014 | 799 parents | Parents of children aged 11–18 years | Parents or guardians of child aged 11–18 years who is the primary parent that takes the child(ren) to get vaccinated of Native Hawaiian, Filipino, Japanese, or Caucasian ancestry and a Hawai’i resident | Telephone survey instrument |

| Pierre-Victor et al, 2018 | Qualitative cross-sectional | June 2014- March 2015 | 30 females | 17–26 years | Females aged 17–26 years who self-identified as Haitian | Qualitative interviews |

| Ramirez et al, 2014 | Cross- sectional | Not specified | 17 guardians | Guardians of daughters aged 8–17 years | Hispanic mothers and grandmothers who were the primary caretakers of daughters aged 8–17 years | Qualitative interviews |

| Mehta et al, 2012 | Cross- sectional | January 2008- December 2010 | 269 women | 18–27 years | Women aged 18–27 years who were residents of New Haven County and had interviews and medical record reviews complete | Chart review |

| Reiter et al, 2014 | Cross- sectional | 2010–2011 | 2,786 parents | Parents of children aged 13–17 years | Hispanic parents of children aged 13–17 years who completed the National Immunization Survey-Teen in 2010 or 2011 | Secondary data analysis of surveys |

| Daley et al, 2011 | Cross- sectional | Not specified | 477 men | 18–70 years | Men aged 18–70 who participated in the Natural History Study of HPV Infection in Men study and completed the questionnaire | Computer assisted survey instrument |

| Liddon et al, 2012 | Cross- sectional | July 2007 to December 2008 | 1243 women | 15–24 years | Females aged 15–24 years who participated in the National Survey of Family Growth during the specified timeframe | Questionnaire |

| Taylor et al, 2014 | Cross- sectional | 2012–2013 | 86 mothers | Mothers of daughters aged 9–17 years | Cambodian mothers of daughters aged 9–17 years | Qualitative survey instrument |

| Miller et al, 2014 | Mixed methods | July-November 2012 | 50 adolescents | 14–18 years | Adolescents aged 14–18 years receiving services at participating CBOs who spoke English | Survey and focus group |

| Pierre Joseph et al, 2014 | Cross- sectional | December 2010- October 2011 | 89 men | 18–22 years | Men aged 18–22 who spoke English, Spanish, or Haitian Creole and attended a clinic for preventive care or a problem-related visit | Qualitative survey instrument |

| Cunningham- Erves et al, 2018 | Mixed methods | Not specified | 246 mothers | Mothers of daughters aged 9–12 | Black mothers of daughters aged 9–12 years who were Alabama residents | Survey and semi- structured qualitative |

| years | interviews | |||||

| Otanez et al, 2018 | Cross- sectional | 2007 | 5675 adults | 18+ | Men and women 18 years or older who were HINTS participants in 2007 | HINTS survey |

| Strohl et al, 2015 | Cross- sectional | Not specified | 215 women | 18–70 years | English-speaking women who self-identified as African American and were aged 18– 70 years | Self-administered paper survey |

| Kobetz et al, 2011 | Qualitative cross-sectional | 2010 | 41 women | 21–71 years | Women who self-identified as Haitian, currently lived in Little Haiti, and were between the ages of 21 and 75 years | Focus group qualitative data |

| Warner et al, 2015 | Cross- sectional | August-October 2013 | 52 parents | Parents of children aged 11–17 years | Parents/guardians of Latino male and female adolescents who were ages 11–17 years and could speak or read Spanish | Self-administered survey |

| JL Ford, 2011 | Cross- sectional | 2007–2008 | 1019 women | 18–24 years | Women aged 18–24 years who completed the National Survey of Family Growth in 2007 or 2008 | National Survey of Family Growth Survey |

| Allen et al, 2010 | Cross- sectional | September 2007- January 2008 | 563 parents | Parents of daughters aged 9–17 years | Parents of a daughter aged 9– 17 years and self-identified as Black, Hispanic, or White | Web-based survey |

| Sanders et al, 2012 | Qualitative cross-sectional | February-June 2009 | 30 parents | Parents of daughters aged 9–17 years | African American parents of a daughter aged 9–17 years with no history of HPV infection | Face-to-face interview |

| Hennebery et al, 2020 | Cross- sectional | June 2014- December 2017 | 102 parents; 149 young adult women | Parents of daughters aged 12–17 years; young adult women | Parents of daughters aged 12– 17 years or young adult women aged 18–26 years who attended Obstetrics & Gynecology and Pediatric | Survey |

| aged 18–26 years | clinics in urban and suburban New Orleans, Louisiana during the specified timeframe | |||||

| Chando et al, 2013 | Cross- sectional | 2007 | 1090 parents | Parents of daughters aged 11–17 years | Parents of daughters aged 11– 17 years who completed the 2007 California Health Interview Survey and reported their racial group as White | California Health Interview Survey |

| Jones et al, 2017 | Cross- sectional | Not specified | 840 students (male=317, females=523) | 18–64 | State university and community college students in South Florida who could read and write in English | Survey |

Note. HINTS = Health Information National Trends Survey; US = United States of America; RCT = randomized controlled trial; UTMB = University of Texas Medical Branch; UCLA = University of California, Los Angeles

Results

The data reviewed demonstrated various barriers to HPV vaccination among racial/ethnic minorities compared to the White counterparts. The major findings are presented in three major themes: (1) gaps in knowledge and provider recommendations, (2) medical mistrust and safety concerns, and (3) religious and cultural beliefs (Appendix Table 1). These barriers are discussed in detail below.

Gaps in Knowledge and Provider Recommendations

Differences in knowledge and awareness were demonstrated in various ways. Gender differences was shown to be a predictor of disparate knowledge and awareness of HPV and the HPV vaccine. In general, women and mothers of adolescent girls were more aware of HPV and the HPV vaccine as well as association between cervical cancer and HPV infection, while men and parents of adolescent boys were typically less aware of both HPV and HPV vaccine, and had little-to-no intention of vaccinating their sons. [6–9]

In some studies, racial/ethnic minority groups had significantly lower knowledge of HPV, the HPV vaccine, and the association between HPV and other cancers when compared to Whites (i.e. oral, anal, and penile cancers). [10–20] Not only were the parents of adolescents lacking knowledge, but adult individuals who were still in the catch-up age range lacked knowledge of HPV and the HPV vaccine. [7, 22–23] However, in other studies, women reported higher levels of awareness (i.e., having heard of HPV and the HPV vaccine), but exhibited low levels of specific knowledge about HPV and the HPV vaccine. Specifically, in regards to the number of doses required for vaccination completion and the potential severity of HPV infection. [10, 24–26]

Table 2 summarizes the main quantitative findings on relative measures of association (i.e., odds ratios) regarding knowledge of HPV and the HPV vaccine, as well as vaccination willingness and intentions. When quantified, Hispanic adult individuals tended to have lower odds of having heard of the HPV vaccine when compared to non-Hispanics. [23, 27–28] Black and Asian adult individuals tended to have lower odds of having heard of HPV when compared to Whites. Also, Asian adult individuals had lower odds of having heard of the HPV vaccine compared to Whites. [23, 27–29]

Table 2.

Summary of Main Quantitative Findings For Studies That Reported Relative Measures of Association

| Source | Racial/ethnic group | Comparison Group | Knowledge and awareness, aOR (95% CI) | HPV Vaccination, aOR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heard of HPV | Heard of HPV Vaccine | Intent-to-initiate | Vaccine Initiation | Vaccine Completion | Safety Concerns | |||

| Blake et al, 2015 | Black | White | 0.74 (0.41 – 1.34) | 0.70 (0.38 – 1.30) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | 0.74 (0.43 – 1.27) | 0.50 (0.30 – 0.82) | |||||

| Other | White | 0.19 (0.08 – 0.46) | 0.36 (0.17 – 0.75) | |||||

| McBride et al, 2018* | Black | White | 0.67 (0.50 – 0.90) | 0.82 (0.60 – 1.12) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | 0.86 (0.67 – 1.11) | 1.00 (0.91 – 1.10) | |||||

| Asian | White | 0.44 (0.28 – 0.71) | 0.61 (0.44 – 0.85) | |||||

| Other | White | 0.70 (0.42 – 1.16) | 0.90 (0.57 – 1.45) | |||||

| Boakye et al, 2017 | Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Hispanic White | 0.68 (0.47 – 0.98) | 0.57 (0.40 – 0.84) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Hispanic | Non-Hispanic White | 0.73 (0.52 – 1.02) | 0.49 (0.35 – 0.67) | |||||

| Other | Non-Hispanic White | 0.29 (0.19 – 0.46) | 0.42 (0.27 – 0.66) | |||||

| Glenn et al, 2015 | Non-Korean | Korean | 1.68 (0.86 – 3.28) | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Kashani et al, 2019 | American Indian/Alaska Native | Non-Hispanic White | NA | NA | NA | 1.55 (1.46 – 1.64) | 1.05 (0.95 – 1.15) | NA |

| Guerry et al, 2011 | English- speaking Latino | Spanish- speaking Latino | NA | NA | NA | 1.2 (0.3 – 1.45) | NA | NA |

| Black | Spanish- | 0.6 (0.8 - | ||||||

| speaking Latino | 2.1) | |||||||

| Other | Spanish- speaking Latino | 0.1 (0.96 – 1.1) | ||||||

| Bastani et al, 2011 | Latina | Non-Latina | NA | NA | NA | 0.84 (0.41 – 1.71) | NA | NA |

| Pierce et al, 2013 | Black | Non-Hispanic White | NA | NA | NA | 4.9 (1.8 – 13.6) | NA | NA |

| Other | Non-Hispanic White | 4.2 (1.1 – 16.6) | ||||||

| Cheruvu et al, 2017 | Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Hispanic White | NA | NA | 0.96 (0.81 – 1.12) | NA | NA | 0.75 (0.57 – 0.98) |

| Hispanic | Non-Hispanic White | 0.79 (0.66 – 0.95) | 0.80 (0.59 – 1.10) | |||||

| Other | Non-Other White | 0.96 (0.76 – 1.22) | 0.70 (0.52 – 0.94) | |||||

| Sriram et al, 2019 | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic White | NA | NA | NA | 1.47 (1.24 – 1.74) | NA | NA |

| Other | Non-Hispanic White | 1.75 (1.48 – 2.07) | ||||||

| Dela Cruz et al, 2018 | Native Hawaiian daughters | Japanese daughters | NA | NA | NA | 1.38 (0.71 – 2.67) | NA | NA |

| Native Hawaiian sons | Japanese sons | 0.89 (0.48 – 1.65) | ||||||

| Filipino daughters | Japanese daughters | 0.94 (0.48 – 1.84) | ||||||

| Filipino sons | Japanese sons | 0.64 (0.32 – 1.27) | ||||||

| Caucasian daughters | Japanese daughters | 0.56 (0.31 – 1.04) | ||||||

| Caucasian sons | Japanese sons | 0.47 (0.26 – 0.85) | ||||||

| Reiter et al, | Black | White | NA | NA | NA | 1.14 (0.67 - | 1.20 (0.70 - | NA |

| 2014 | 1.96) | 2.06) | ||||||

| Other | White | 1.03 (0.60 – 1.77) | 1.05 (0.62 – 1.79) | |||||

| Daley et al, 2011 | Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Hispanic White | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.72 (0.41 – 1.26) |

| Hispanic | Non-Hispanic White | 0.75 (0.45 – 1.23) | ||||||

| Otanez et al, 2018 | Hispanic | White | NA | NA | 1.30, p<.01 | NA | NA | NA |

| Black | White | 0.82, p<0.05 | ||||||

| Ford, 2011 | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic White | 0.10 (0.05 – 0.19) | 0.13 (0.07 – 0.27) | NA | 0.44 (0.21 – 0.90) | NA | NA |

| Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Hispanic White | 0.23 (0.13 – 0.40) | 0.27 (0.14 – 0.52) | 0.16 (0.07 – 0.35) | ||||

| Allen et al, 2010 | Black | White | NA | NA | 0.69 (0.30 – 1.58) | NA | NA | NA |

| Hispanic | White | 1.08 (0.47 – 2.48) | ||||||

| Hennebery et al, 2020 | Non-Hispanic White young adults | Other | NA | NA | NA | 1.77 (0.60 – 5.22) | NA | NA |

| Non-Hispanic White guardians | Other | 0.66 (0.24 – 1.82) | ||||||

| Chando et al, 2013 | Spanish- speaking Hispanics | English- speaking Hispanics | NA | NA | NA | 0.55 (0.31 – 0.98) | NA | NA |

Note. aOR = adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; HPV = Human Papillomavirus; NA = not assessed

Note. Provider recommendations and medical mistrust, religious and cultural beliefs, and safety and efficacy concerns were not assessed using relative measures of association in these studies.

This study reported measures of association as regression coefficients and standard errors. For uniformity, these estimates have been converted to odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Equation used for converting regression coefficient to OR: êβ𝛽; Equation used for converting standard error into 95% CI: ê(β±1.96(SE(β))).

Despite these disparities, racial/ethnic minority parents tended to be more likely to initiate the HPV vaccination in their children when compared to their White counterparts. [30–35] Notably, an inverse association between knowledge of HPV and willingness to vaccinate may exist among Black parents. [36] This may imply that having any knowledge of HPV may decrease willingness of Black parents to vaccinate their children when compared to having no knowledge of HPV. Conversely, in other individual adult racial/ethnic minorities, willingness to vaccinate was associated with higher levels of HPV knowledge. [36–37]

In addition to these findings, foreign-born Black and Latino/a individuals were less likely to know where they could obtain an HPV vaccine compared to their U.S.-born counterparts. [13] Studies were conflicting in their findings about the role that language preference may have in Hispanics with regards to willingness to vaccinate. Some studies suggest that Spanish-speaking parents were more willing to vaccinate their children when compared to English-speaking parents, while other findings suggest the opposite. [38–39]

The literature suggests that low knowledge may be tied to a lack of recommendations for HPV vaccination from healthcare providers. Receipt of a provider recommendation was found to be the strongest predictor of HPV vaccination and intent/willingness of racial/ethnic minority parents to vaccinate their children. [12, 15, 17, 25, 34, 40–42] In parents who had initiated vaccination in their children, provider recommendation was found to be the main reason. [12, 17, 32–33, 38, 40, 42] Similarly, racial/ethnic minority adult individuals reported that having discussed the vaccine with their healthcare provider was associated with increased likelihood of vaccination. [19, 37]

Further, lack of a strong recommendation from healthcare providers was also associated with decreased vaccine initiation and completion in racial/ethnic minority populations. [9, 16, 30, 38, 40, 41, 43–44] Results showed that some providers offered the vaccine as optional or of low importance. [30, 45] Lower perceived risk for HPV infection was also reported among these populations. [14, 17] Furthermore, some parents of racial/ethnic minority adolescents who had initiated vaccination but did not complete the vaccine series reported receiving no information from their healthcare providers about follow-up to receive subsequent, necessary doses of the vaccine at a later date. [17, 24, 45]

Medical Mistrust and Safety Concerns

The level of importance of medical mistrust and safety concerns regarding HPV vaccination among racial/ethnic minorities varies. In general, racial/ethnic minorities who had not initiated vaccination in their children were more likely to exhibit some level of mistrust with healthcare professionals and pharmaceuticals. [14, 24–25, 31–32, 44, 46–47] In adult individuals who reported medical mistrust as a barrier to vaccination, it was suggested that Hispanics and Blacks preferred a healthcare provider of the same-sex, and/or same race/ethnicity. [48–49] Further, Black and Asian women who had not been vaccinated demonstrated higher medical mistrust when compared to those who had been vaccinated, which was associated with preference to receive the HPV vaccine recommendation from a healthcare provider of the same race/ethnicity. [48–49]

In addition, racial/ethnic minority parents who were knowledgeable about HPV and the HPV vaccine tended to have concerns with the vaccine’s safety and side effects. Those who reported safety and efficacy concerns noted that this was a very important factor in deciding whether or not to vaccinate their children against HPV. [24–25, 31, 46] Some parents believed vaccination may cause infertility in their daughters and were unsure of other potential side effects that might be associated with the vaccine. [24–25, 31, 46, 51] They were also concerned that other long-term health problems may be associated with vaccinating their children. [24–25, 31, 46]

In studies examining racial/ethnic minority adult individuals in the catch-up age range, some reported that they would be willing to vaccinate if they could be sure that side effects were not severe. [6–7, 50] Conversely, it was suggested that non-Hispanic White men may be more wary of potential side effects than their Black and Hispanic counterparts, leading to no intention of vaccination. [50]

Religious and Cultural Beliefs

Religious and cultural beliefs were mostly assessed in qualitative studies and non-U.S.-born populations. Asian-American parents and foreign-born Hispanic parents were found to demonstrate a belief that the HPV vaccine was unacceptable for their children, especially their daughters, due to fear of promoting promiscuous behavior. [25] With fathers acting as the ultimate decision-makers in these familial paradigms, most children are not vaccinated. [18] Further, cultural perceptions were reported to serve as the main source of knowledge in some non-U.S.-born parents’ decisions about HPV and willingness to vaccinate their children. [18, 32]

Conclusions

Our findings suggest a considerable lack of accurate knowledge and awareness of HPV and the HPV vaccine within racial/ethnic minority communities. However, educational interventions have not been shown to be an effective strategy in increasing vaccine uptake. Further, with Black parents possibly showing an inverse correlation between knowledge and intent to vaccinate, targeting education towards increasing HPV knowledge may not have the intended effects across racial/ethnic minority communities. Thus, increasing strong provider recommendations may be the most effective strategy in combatting low vaccine coverage among these populations. Specifically, an approach used by the American Academy of Pediatrics called “same day, same way” approach may be useful in heightening healthcare providers’ ability to introduce the HPV vaccine and to address the concerns of parents who have hesitance about the HPV vaccine. [54] This may be especially important in curtailing misinformation about HPV vaccination and easing concerns of safety and adverse vaccine reactions. Being that provider recommendations were shown to be the most important factor in parents’ willingness to vaccinate their children, this area should be targeted effectively.

Further, because some racial/ethnic minority adult individuals reported being more trusting of educators and healthcare providers who look like them, diversity among health educators and healthcare providers, and presenting information in a way that is tailored to each community may be beneficial in the effort to increase HPV vaccination rates. Though the role of patient-physician racial/ethnic concordance has not been thoroughly studied in HPV vaccination, it is an idea to be considered.

Moreover, an increase in awareness and vaccination recommendations for boys is needed and parents of both girls and boys must equally be educated. Also, awareness and recommendations must increase for adult individuals in the age range for catch-up vaccination. Gender differences should be addressed if vaccine uptake is to increase.

Over half of the literature covered in this review involved parents of adolescent children. There is low representation of adults who are in the catch-up age range for vaccination as well as males. Though the priority population for HPV vaccination remains 11–12 year olds, there may be benefit in understanding the disparities faced by persons in the catch-up age range. This is due to the fact that even if someone has already been exposed to HPV, catch-up vaccination through age 45 has been shown to be efficacious in protecting against persistent infection and other strains of HPV. [55–56] Both children and adults in the vaccine-appropriate age range should be vaccinated, since recommendations for HPV vaccination have now been expanded through age of 45.

It is critical to identify and address barriers to vaccination, in order to increase vaccine initiation and completion and decrease the disparate burden of poor HPV-related health outcomes experienced by racial/ethnic minority groups. Low provider recommendations as well as lack of accurate knowledge and awareness among racial/ethnic minority populations is associated with a decrease in HPV vaccine initiation and completion. The most common barriers to HPV vaccination were lack of healthcare provider recommendations, low knowledge and awareness of HPV and the HPV vaccine, as well as safety concerns. To effectively target these communities, multi-level interventions need to be established. An increase in provider recommendations along with distribution of accurate information to these communities is necessary to combat the lack of HPV vaccination initiation and completion. As the recommended interventions are completed, prospective studies will be needed to assess the effectiveness of such intervention programs on HPV vaccination.

Limitations

There is limited literature available that specifically examines barriers in racial/ethnic health disparities related to HPV vaccination, thus, this review was limited to the few available literature. The decision to use PubMed was because it is believed that this database provides good coverage of the available English-language literature; however, it is possible that additional relevant articles not represented in PubMed were missed. Further, the data included in this review were cross-sectional in nature and so there is a risk of temporal ambiguity. The survey data collection used by most of the studies leaves room for self-report bias. Specifically, self-reported vaccination has been shown to be racially biased thus linking barriers to self-reported vaccination may be inherently biased. [5, 57] Additionally, the classifications of race in these studies may be a limitation as not all studies used the same classifications, thus making it difficult to compare across studies.

Table 3.

Summary of Main Quantitative Findings For Studies That Reported Frequency Measures

| Source | Racial/ethnic group | Category | Knowledge and awareness and provider recommendations | Religious and cultural beliefs | Safety concerns and medical mistrust | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | ||||||

| Heard of HPV | Heard of HPV Vaccine | Received provider recommendation | Lack of provider recommendation | |||||

| Davlin et al, 2015 | Total sample | 312/468 (66.8) | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| White | 83/96 (86.5) | |||||||

| Black | 141/191 (73.8) | |||||||

| Hispanic | 239/409 (58.4) | |||||||

| Other | 5/5 (100.0) | |||||||

| Glenn et al, 2015 | Total sample | 306/489 (62.6) | 294/490 (60.0) | 193/294 (65.6) | NA | NA | 32/59 (54.2) | |

| Korean | 30/66 (45.4) | |||||||

| Non-Korean | 276/423 (65.2) | |||||||

| Ashing et al, 2017 | US-born African | 70/129 (54.3) | 91/129 (70.6) | NA | NA | NA | 40/129 (31.0) | |

| African Immigrant | 36/53 (67.9) | 30/53 (57.7) | 22/53 (42.3) | |||||

| US-born Latina | 29/57 (50.9) | 44/57 (76.8) | 25/57 (44.6) | |||||

| Latina Immigrant | 84/144 (58.7) | 73/144 (50.7) | 78/144 (54.3) | |||||

| Hernandez et al, 2017 | Total sample | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Romaguera et al, 2015 | Total sample | 463/566 (81.8) | 366/566 (64.8) | NA | 6/54 (12.2) | NA | 17/54 (32.7) | |

| Kolar et al, 2015 | Total sample | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7/105 (6.7) | 59/105 (56.2) | |

| Hispanic | ** | ** | ||||||

| Black | 7/31 (22.6) | 20/31 (64.5) | ||||||

| O’Leary et al, 2018*** | Total sample | Very Important | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 93/131 (74.4) |

| Somewhat Important | 123/131 (18.4) | |||||||

| Unimportant | 9/131 (7.2) | |||||||

| Dela Cruz et al, 2017 | Total sample | 10/20 (50) | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Sledge, 2015 | Total sample | 58/68 (85) | 9/68 (13.2) | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Victory et al, 2019 | Total sample | 539/622 (86.7) | 520 (83.6) | NA | NA | NA | 34/622 (5.5) | |

| Kepka et al, 2015 | Total sample | 52/67 (77.6) | 52/67 (77.6) | NA | NA | NA | 19/67 (30.7) | |

| Lechuga et al, 2016 | Total sample | 218/296 (73.6) | 164/296 (55.4) | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Guerry et al, 2011 | Total sample | 365/509 (72.4) | 267/509 (53.1) | 149/509 (29.6) | NA | NA | 66/509 (13.0) | |

| Btoush et al, 2019 | Total sample | NA | 73/132 (55.3) | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Bastani et al, 2011 | Latina | 163/255 (64) | 158/255 (62) | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Chinese | 65/98 (66) | 63/98 (64) | ||||||

| Korean | 30/66 (46) | 27/62 (44) | ||||||

| Black | 26/38 (68) | 25/38 (65) | ||||||

| Other | 22/32 (69) | 21/32 (66) | ||||||

| Kepka et al, 2018 | Total sample | Parents of daughters | NA | 21/99 (21.21) | NA | 69/99 (69.70) | NA | 14/99 (14.14) |

| Total sample | Parents of sons | 30/100 (30.00) | 76/100 (76.00) | 18/100 (18.00) | ||||

| Sriram et al, 2019 | Total sample | NA | NA | NA | 2393/16900 (14.16) | 70/17073 (0.41) | 2420/16900 (14.32) | |

| Dela Cruz et al, 2018 | Native Hawaiian daughters | NA | 14/48 (29.2) | NA | 20/48 (41.7) | NA | 32/48 (66.7) | |

| Native Hawaiian sons | 38/74 (51.4) | 34/74 (45.9) | 42/74 (56.8) | |||||

| Filipino daughters | 30/67 (44.8) | 32/67 (47.8) | 42/67 (62.7) | |||||

| Filipino sons | 35/66 (53.0) | 38/66 (57.6) | 33/66 (50.0) | |||||

| Caucasian daughters | 9/62 (14.5) | 13/62 (21.0) | 41/62 (66.1) | |||||

| Caucasian sons | 19/80 (23.8) | 42/80 (52.5) | 43/80 (53.8) | |||||

| Japanese daughters | 21/45 (46.7) | 22/45 (48.9) | 24/45 (53.3) | |||||

| Japanese sons | 24/55 (43.6) | 33/55 (60.0) | 27/55 (49.1) | |||||

| Mehta et al, 2012 | White | NA | 90/99 (90.9) | 143/183 (78.1) | NA | NA | NA | |

| Black | 19/25 (76.0) | 26/36 (72.2) | ||||||

| Other | 9/15 (60.0) | 13/22 (59.1) | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 105/120 (87.5) | 165/214 (77.1) | ||||||

| Hispanic | 20/29 (69.0) | 28/44 (63.6) | ||||||

| Reiter et al, 2014 | Hispanic | 2319/2856 (81.2) | 2446/2936 (83.3) | 1467/2946 (49.8) | 54/529 (10.2) | NA | 156/739 (21.1) | |

| Daley et al, 2011 | Non-Hispanic White | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 205/306 (67.0) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 40/80 (50.0) | |||||||

| Hispanic | 53/90 (59.0) | |||||||

| Liddon et al, 2012 | Total sample | NA | NA | NA | 89/144 (14.6) | NA | 57/104 (11.8) | |

| Taylor et al, 2014 | Cambodian American | NA | NA | 10/24 (42.0) | 12/49 (24.0) | NA | 40/86 (47.0) | |

| Miller et al, 2015 | Total sample | NA | 24/50 (48.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Otanez et al, 2018 | Total sample | 63% | 65% | NA | NA | NA | 31% | |

| Strohl et al, 2015 | Black | NA | NA | NA | 27/164 (16.5) | NA | 8/163 (4.9) | |

| Hennebery et al, 2020 | Total sample | Young adults | 86/146 (59.0) | NA | 52/133 (39) | 8/24 (33.0) | 10/96 (10) | 5/97 (5) |

| Total sample | Guardians | 67/103 (65) | 73/99 (74) | 2/6 (33.0) | 10/94 (10) | 7/93 (8) | ||

Note: HPV = Human Papillomavirus; NA = not assessed

Upon review of the findings, an error was found in the reporting of this specific category thus the numbers were not included in this table.

This study reported proportions of parents who thought safety and efficacy was very important, somewhat important, or unimportant in deciding whether or not to vaccinate their children.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported in part by NIH R01 Grant number R01AI116914 from the NIH Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Funding

This work was supported in part by NIH R01 Grant number R01AI116914 from the NIH Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

APPENDICES

APPENDIX A: Table 1

Appendix Table 1.

Summary of main qualitative findings related to barriers to HPV vaccine uptake among racial/ethnic minorities

| Themes | Major findings |

|---|---|

| Gaps in knowledge and provider recommendations | • Provider recommendation was found to be the most important factor in deciding to initiate and complete the HPV vaccine in racial/ethnic minority populations. • Some HCPs present the vaccine as optional or of low importance, therefore many racial/ethnic minorities reported a lower perceived risk of HPV infection. • Some Black, Latino/a, and Asian women who were not vaccinated report increased medical mistrust and preferred recommendations from HCP that was of the same race/ethnicity. • Racial/ethnic minority adolescents who had initiated the vaccine did not complete it because they reported receiving no knowledge from HCP about follow-up vaccination schedules. • Overall, knowledge and acceptability of the HPV vaccine was found to be low in racial/ethnic minority groups when compared to non-Hispanic Whites. • Gender differences showed disparate knowledge and awareness as racial/ethnic minority women typically knew more about HPV than men. • Foreign-born Black and Latino/a individuals were much less likely to know about HPV vaccine when compared to their US-born counterparts. • Women reported receiving recommendations for HPV vaccination from their HCP at higher rates than men. |

| Medical mistrust and safety concerns | • Some racial/ethnic minority parents who were knowledgeable about the HPV vaccine believed that it was unsafe and ineffective. Some parents believed it could cause infertility and other long-term health effects. • Some non-U.S.-born non-Hispanic parents reported mistrust of medical professionals and preferred an HCP that was of the same race/ethnicity. • Some racial/ethnic minority parents reported mistrust of pharmaceuticals. • Young adult White men tended to be more concerned with safety and side effects than young adult men of other races. |

| Religious and cultural beliefs | • Non-U.S.-born parents tended to believe that vaccinating their children would promote promiscuous behavior. • In non-U.S.-born non-Hispanic parents, cultural perceptions tended to serve as a source of knowledge for decisions to not vaccinate rather than HCP recommendations. |

Note. US = United States; HCP = Health Care Provider; HPV = Human papillomavirus.

APPENDIX B: Search Strategy (PubMed) – MeSH Terms

(((“papillomaviridae”[MeSH Terms] OR “papillomaviridae”[All Fields]) OR ((“human”[All Fields] AND “papillomavirus”[All Fields]) AND “hpv”[All Fields])) OR “human papillomavirus hpv”[All Fields]) AND (((((((((((((((((((“vaccin”[Supplementary Concept] OR “vaccin”[All Fields]) OR “vaccination”[MeSH Terms]) OR “vaccination”[All Fields]) OR “vaccinable”[All Fields]) OR “vaccinal”[All Fields]) OR “vaccinate”[All Fields]) OR “vaccinated”[All Fields]) OR “vaccinates”[All Fields]) OR “vaccinating”[All Fields]) OR “vaccinations”[All Fields]) OR “vaccination s”[All Fields]) OR “vaccinator”[All Fields]) OR “vaccinators”[All Fields]) OR “vaccine s”[All Fields]) OR “vaccined”[All Fields]) OR “vaccines”[MeSH Terms]) OR “vaccines”[All Fields]) OR “vaccine”[All Fields]) OR “vaccins”[All Fields]) AND ((“barrier”[All Fields] OR “barrier s”[All Fields]) OR “barriers”[All Fields])

Footnotes

Conflict of interest/Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.CDC. Genital HPV Infection – Fact Sheet. Division of STD Prevention, Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. Accessed 26 Nov 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. Human Papillomavirus. National Center of Immunization and Respiration Diseases. 2018. Accessed 26 Nov 2018. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/vaccine.html. [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA approves expanded use of Gardasil 9 to include individuals 27 through 45 years old. FDA News Release, October5, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-expanded-use-gardasil-9-include-individuals-27-through-45-years-old. [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017. Division of STD Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018. Accessed 26 Nov 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/other.htm#hpv.

- 5.Spencer et al. Disparities and reverse disparities in HPV vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2019June;123:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.03.037. Epub 2019 Mar 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sledge JA. The Male Factor: Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV4 Vaccine Acceptance Among African American Young Men. J Community Health. 2015August;40(4):834–42. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-0007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller et al. Views on human papillomavirus vaccination: a mixed-methods study of urban youth. J Community Health. 2014October;39(5):835–41. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9858-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joseph Pierre et al. Ethnic differences in perceived benefits and barriers to HPV vaccine acceptance: a qualitative analysis of young African American, Haitian, Caucasian, and Latino men. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014February;53(2):177–85. doi: 10.1177/0009922813515944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warner et al. Latino Parents’ Perceptions of the HPV Vaccine for Sons and Daughters. J Community Health. 2015June;40(3):387–94. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9949-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davlin et al. Correlates of HPV knowledge among low-income minority mothers with a child 9–17 years of age. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015February;28(1):19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.01.109. Epub 2014 Nov 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kepka et al. Low human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine knowledge among Latino parents in Utah. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015February;17(1):125–31. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0003-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Btoush et al. Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Human Papillomavirus Vaccination AmongLatina Mothers of South American and Caribbean Descent in the Eastern US. Health Equity. 2019May30;3(1):219–230. doi: 10.1089/heq.2018.0058.eCollection 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bastani et al. Understanding suboptimal human papillomavirus vaccine uptake among ethnicminority girls. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011July;20(7):1463–72. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0267. Epub 2011 May 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kepka et al. Factors Associated with Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Among DiverseAdolescents in a Region with Low Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Rates. Health Equity. 2018September1;2(1):223–232. doi: 10.1089/heq.2018.0028.eCollection 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cruz Dela et al. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination Motivators, Barriers, andBrochure Preferences Among Parents in Multicultural Hawai’i: a Qualitative Study. J Cancer Educ. 2017September;32(3):613–621. doi: 10.1007/s13187-016-1009-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination history among women with precancerouscervical lesions: disparities and barriers. Obstet Gynecol. 2012March;119(3):575–81. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182460d9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor et al. Understanding HPV vaccine uptake among Cambodian American girls. J Community Health. 2014October;39(5):857–62. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9844-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim et al. Knowledge, perceptions, and decision-making about human papillomavirus vaccination among Korean American women: A focus group study. Womens Health Issues. 2015March-April; 25(2): 112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobetz et al. Perceptions of HPV and cervical cancer among Haitian immigrant women: implications for vaccine acceptability. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2011December;24(3):479. Epub 2011 Dec 7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen et al. Parental decision making about the HPV vaccine. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010September;19(9):2187–98. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallagher et al. Factors influencing completion of multi-dose vaccine schedules inadolescents: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2016February19;16:172. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2845-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strohl et al. Barriers to prevention: knowledge of HPV, cervical cancer, and HPV vaccinations among African American women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015January;212(1):65.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.06.059. Epub 2014 Jun 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ford JL. Racial and ethnic disparities in human papillomavirus awareness and vaccination among young adult women. Public Health Nurs. 2011November-December;28(6):485–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2011.00958.x. Epub 2011 Jun 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Leary et al. Exploring Facilitators and Barriers to Initiation and Completion of the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Series among Parents of Girls in a Safety Net System. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018January23;15(2). pii: E185. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15020185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lechuga et al. HPV Vaccine Awareness, Barriers, Intentions, and Uptake in Latina Women. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016February;18(1):173–8. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0139-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romaguera et al. Factors Associated with HPV Vaccine Awareness in a Population-Based Sample of Hispanic Women in Puerto Rico. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016June;3(2):281–90. doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0144-5. Epub 2015 Jul 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blake et al. 2015. Predictors of Human Papillomavirus Awareness and Knowledge in 2013: Gaps and Opportunities for Targeted Communication Strategies. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2015April: 48(4): 402–410. doi 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boakye et al. Approaching a decade since HPV vaccine licensure: Racial and gender disparities in knowledge and awareness of HPV and HPV vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017November2;13(11):2713–2722. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1363133. Epub 2017 Aug 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McBride K, Singh S. Predictors of Adults’ Knowledge and Awareness of HPV, HPV-Associated Cancers, and the HPV Vaccine: Implications for Health Education. Health Educ Behav. 2018February;45(1):68–77. doi: 10.1177/1090198117709318. Epub 2017 Jun 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kashani et al. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Trends, Barriers, and Promotion Methods Among American Indian/Alaska Native and Non-Hispanic White Adolescents in Michigan 2006–2015. J Community Health. 2019June;44(3):436–443. doi: 10.1007/s10900-018-00615-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierce et al. Post Approval Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Uptake Is Higher in Minorities Compared to Whites in Girls Presenting for Well-Child Care . Vaccines (Basel). 2013July17;1(3):250–61. doi: 10.3390/vaccines1030250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sriram S and Ranganathan R. Why human papilloma virus vaccination coverage is low among adolescents in the US? A study of barriers for vaccination uptake. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019. March;8(3):866–870. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_107_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheruvu et al. Factors associated with parental reasons for “no-intent” to vaccinate female dolescents with human papillomavirus vaccine: National Immunization Survey - Teen 2008–2012. BMC Pediatr. 2017February13;17(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s12887-017-0804-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cruz Dela et al. HPV vaccination prevalence, parental barriers and motivators to vaccinating children in Hawai’i. Ethn Health. 2018May10:1–13. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2018.1473556. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liddon et al. Intent to receive HPV vaccine and reasons for not vaccinating among unvaccinated adolescent and young women: findings from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. Vaccine. 2012March30;30(16):2676–82. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.007. Epub 2012 Feb 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Otanez S and Torr BM. Ethnic and Racial Disparities in HPV Vaccination Attitudes. J Immigr Minor Health. 2018. December;20(6):1476–1482. doi: 10.1007/s10903-017-0685-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hennebery et al. Factors Associated with Initiation of HPV Vaccination Among Young Women and Girls in Urban and Suburban New Orleans. J Community Health. 2020August;45(4):775–784. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00793-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reiter et al. Provider-verified HPV vaccine coverage among a national sample of Hispanic adolescent females. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014. May;23(5):742–54. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0979. Epub 2014 Mar 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chando et al. Effects of socioeconomic status and health care access on low levels of human papillomavirus vaccination among Spanish-speaking Hispanics in California. Am J Public Health. 2013February;103(2):270–2. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300920. Epub 2012 Dec 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guerry et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine initiation among adolescent girls in high-risk communities. Vaccine. 2011March9;29(12):2235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.052. Epub 2011 Feb 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cunningham-Erves et al. Black mother’s intention to vaccinate daughters against HPV: A mixed methods approach to identify opportunities for targeted communication. Gynecol Oncol. 2018June;149(3):506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.03.047. Epub 2018 Mar 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanders et al. African American parents’ HPV vaccination intent and concerns. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012February;23(1):290–301. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Victory et al. Parental knowledge gaps and barriers for children receiving human papillomavirus vaccine in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1678–1687. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1628551. Epub 2019 Jun 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pierre-Victor et al. Barriers to HPV Vaccination Among Unvaccinated, Haitian American College Women. Health Equity. 2018June1;2(1):90–97. doi: 10.1089/heq.2017.0028.eCollection 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Niccolai et al. Parents’ Recall and Reflections on Experiences Related to HPV Vaccination for Their Children. Qual Health Res. 2016May;26(6):842–50. doi: 10.1177/1049732315575712. Epub 2015 Mar 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galbraith et al. African-American parents’ and daughters’ beliefs about HPV infection and the HPV vaccine. Public Health Nurs. 2019March;36(2):134–143. doi: 10.1111/phn.12565. Epub 2018 Dec 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramirez et al. Acceptability of the human papillomavirus vaccine among diverse Hispanic mothers and grandmothers. Hisp Health Care Int. 2014;12(1):24–33. doi: 10.1891/1540-4153.12.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hernandez et al. HPV Vaccine recommendations: does a health care provider’s gender and ethnicity matter to Unvaccinated Latina college women? Ethn Health. 2019August;24(6):645–661. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2017.1367761. Epub 2017 Aug 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kolar et al. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Knowledge and Attitudes, Preventative Health Behaviors, and Medical Mistrust Among a Racially and Ethnically Diverse Sample of College Women. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015March;2(1):77–85. doi: 10.1007/s40615-014-0050-2. Epub 2014 Sep 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Daley et al. Ethnic and racial differences in HPV knowledge and vaccine intentions among men receiving HPV test results. Vaccine. 2011. May 23;29(23):4013–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.060. Epub 2011 Apr 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ashing et al. Examining HPV- and HPV vaccine-related cognitions and acceptability among US-born and immigrant hispanics and US-born and immigrant non-Hispanic Blacks: a preliminary catchment area study. Cancer Causes Control. 2017November;28(11):1341–1347. doi: 10.1007/s10552-017-0973-0. Epub 2017 Nov 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glenn et al. Factors associated with HPV awareness among mothers of low-income ethnic minority adolescent girls in Los Angeles. Vaccine. 2015January3;33(2):289–93. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.11.032. Epub 2014 Nov 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jones et al. Minority College Students’ HPV Knowledge, Awareness, and Vaccination History. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2017September - October;28(5):675–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2017.04.008. Epub 2017 Apr 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.American Academy of Pediatrics. HPV Vaccine is Cancer Prevention: Teaching Tools. 2020. Accessed on 10 Aug 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/immunizations/HPV-Champion-Toolkit/Pages/Grand-Rounds.aspx

- 55.Castellsague et al. End-of-study safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of quadrivalent HPV (types 6, 11, 16, 18) recombinant vaccine in adult women 24–45 years of age. British Journal of Cancer (2011) 105, 28–37 & 2011 Cancer Research UK All rights reserved 0007–0920/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luna et al. Long-term Follow-Up Observation of the Safety, Immunogenicity, and Effectiveness of Gardasil in Adult Women. PLoS ONE (2013) 8(12): e83431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vu et al. A multilevel analysis of factors influencing the inaccuracy of parental reports of adolescent HPV vaccination status. Vaccine. 2019February4;37(6):869–876. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.12.032. Epub 2019 Jan 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]