Abstract

Microencapsulated phage as dry powder provides a protection to the phage particles from the harsh conditions while improving efficacy for controlling Salmonella. In this study, wall materials for phage encapsulation were optimized by altering the ratios of whey protein isolate (WPI) and trehalose prior to freeze-drying. Combination of WPI/trehalose at ratio of 3:1 (w/w) represented the optimal formulation with the highest encapsulation efficiency (91.9%). Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy analysis showed H-bonding in the mixture system and glass transition temperature presented at 63.43 °C. Encapsulated form showed the phage survivability of > 90% after 5 h of exposure to pH 1.5, 3.5, 5.5, 7.5 and 9.5. Phages in the non-encapsulated form could not survive at pH 1.5. In addition, microencapsulated phage showed high effectiveness in decreasing the numbers of S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium by approximately 1 log CFU/ml at 10 °C and 30 °C for both serovars. Phage powder newly developed in this study provides a convenient form for Salmonella control application and this form exhibits high stability over a wide range of temperatures and pH. This encapsulated phage thus can be used in various food applications without being interfered by physiological acidic or alkaline pH of foods or environments where phages are applied.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13197-020-04705-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Salmonella, Salmonella phage, Microencapsulation, Whey protein isolate (WPI), Trehalose

Introduction

The use of bacteriophage (phage) which is a bacterial virus has been gaining an increased interest as biocontrol agent in the food industry lately. Phage shows high specificity to bacterial host and no effect on the sensory characteristics when applied to food (Petsong et al. 2019). Salmonella is a leading cause of hospitalization and considered the top pathogen responsible for the most foodborne-related deaths worldwide. The current use of Salmonella phages is mostly in a suspension (liquid) form for eliminating Salmonella in several food products (Guenther et al. 2012). Microencapsulated phage has been reported as the form which provides the high rate of phage survivability through the harsh conditions. The efficiency of microencapsulated phage formed by chitosan-alginate (alginate bead) has been previously suggested as the desirable form to control Salmonella population in gastro-intestinal tract of animal. However, the diameter of microencapsulated phage in alginate bead, reported size of approximately 800 µm (Ma et al. 2008), might show some effect on consumer’s acceptability in food application. The appearance of this phage-encoded alginate bead in food products may be detected. Preparation of microcapsule prepared with food grade materials while exhibiting nanoscale size is of interest for several reasons, for example, its high stability, ease of use, handling, storage of cultures, and limited effects on sensorial properties of the final food product, especially texture (Amin et al. 2013). Therefore, microencapsulated phage as dry powder is an interesting alternative form while scaling up the production will still require simple instruments such as a homogenizer and freeze dryer.

Among several methods of microencapsulation, freeze-drying has been reported as an effective method which can improve the stability of bacteriophages up to 21 years (Ackermann et al. 2004). In this study, the free-phage suspension was immobilized using whey protein and trehalose as wall material to protect phage particles throughout the transforming process to be dry powder by lyophilization (freeze-drying). Whey protein and trehalose were found as the suitable wall materials for stabilizing and protecting phage particles from encapsulation process and storage conditions (Vonasek et al. 2014). A previous study showed that bacteriophage encapsulated in edible whey protein films could be stabilized at both ambient (22 °C) and refrigerated (4 °C) temperatures without significant loss in phage infectivity more than 1 month (Vonasek et al. 2014). A previous study reported the ability of trehalose in protecting phages from freeze-drying as indicated by a slight decrease of the titer of freeze dried phage with trehalose after storage for 37 months at 4 °C (Puapermpoonsiri et al. 2010).

The aim of this study was to develop the optimal formulation of encapsulated phage as dry powder by altering the ratios of whey protein isolate (WPI) and trehalose used as wall material, followed by transforming to be dry powder via freeze drying. Dry phage powder was characterized for encapsulation efficiency (EE), morphology, and stability in the harsh conditions (temperature and pH) compared to free-phage suspension (non-encapsulated phage). Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis were performed. Antimicrobial efficacy of dry phage powder against S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium at different multiplicity of infections (MOIs) was also investigated.

Materials and methods

Bacteriophage and phage lysate preparation

Salmonella phage SPT 015, previously isolated from a dairy farm in Thailand and characterized as a broad host range phage (Wongsuntornpoj et al. 2014) was used as a core material in this study. Phage was grown to increase the titer following the procedure described by Moreno Switt et al. (2013). Briefly, Salmonella host representing 108 CFU/ml was mixed with phage lysate and 0.7% Tryptone Soya Agar (TSA; Oxoid, Hampshire, UK). The mixture was poured onto a bottom layer (1.5% TSA). For phage enumeration, appropriate dilutions of phage suspension in Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4) were mixed with Salmonella Typhimurium (FSL S5-370).

Salmonella strains

Salmonella Typhimurium (FSL S5-370) was used as a propagating host for Salmonella phage SPT 015. Salmonella Typhimurium (FSL S5-370) and Salmonella Enteritidis (FSL S5-371) isolated from human were obtained from Food Safety Laboratory, Cornell University for our study. Salmonella strains were kept at − 80 °C with 15% glycerol. A single colony from the plate was inoculated in 5 ml Tryptone Soya Broth (TSB; Oxoid, Hampshire, UK) followed by incubation for 16–18 h at 37 °C for preparing overnight culture for the study.

Encapsulation of Salmonella phage and freeze drying

Whey Protein Isolate (WPI) containing > 90% (w/w) protein (Davisco Foods International, USA) was rehydrated in sterilized distilled water. To unfold protein structure, prepared mixture was kept overnight at 4 °C, followed by heating at 80 °C for 30 min under agitation and subsequently cooled to room temperature following a previously described procedures by Picot and Lacroix 2004. The heated mixture showed no precipitation at the bottom of the bottle. Trehalose dihydrate (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd, Japan) was added directly to each prepared whey protein solution to achieve 10% (w/v) total solid for various proportions as shown in Table S1. Phage lysate (109 PFU/ml) was added into the mixture to achieve 10% (v/v). Preparation of the mixture for each formulation to achieve 10% (v/v) was prepared in three separated batches prior to freeze drying. Mixture was kept at − 40 °C for 12 h. Frozen mixture was tempered at − 50 °C using a laboratory scale freeze-dryer (CoolSafe 55, ScanLaf A/S, Lynge, Denmark) under vacuum approximately 30 psi (Welch, 8912 Vacuum pump, Gardner Denver Thomas, Inc, Welch Vacuum Technology Niles, IL, USA) for 48 h. Freeze drying of each prepared mixture was performed in three separated batches to obtain phage powder for further analysis. Dry powder was obtained at 10 ± 0.05 g from each batch and used for the estimation of phage titer per gram.

Characterization of dry phage powder and stability assays

Bacteriophage survivability assay (plaque forming unit counting)

Dry phage powder (1 g) was mixed with 10 ml of PBS and left in a shaking incubator (ThermoStableTM IS-30model, DAIHAN Scientific, Korea) at room temperature, 220 rpm for 1 h. Suspension of the dry phage powder was used for determination of phage survivability by plaque forming unit counting as mentioned above. Using the known total phage titer initially added for phage encapsulation (TP) and the phage titer recovered from the powder (RP), the encapsulation efficiency (EE) was calculated, following the formula: EE (%) = RP/TP × 100. Optimized formulation batches were prepared in duplicate. For each batch, EE was evaluated in triplicate.

Morphology and surface characterization of dry phage powder

Morphology and surface characterization of dry phage powder were examined using a Quanta 250 Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) (Quanta 250, Netherland). Dry phage powder was fixed on aluminum stubs with double adhesive tape and vacuum coated with a fine layer of gold before viewing under magnification of 500×. Observations were carried out with voltage acceleration of 20 kV.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR technique employed the infrared spectroscopy (IR) analysis as described by previous studies (Malferrari et al. 2014; Van der Ven et al. 2002) with modifications. FTIR spectra in the absorbance mode were obtained using an FTIR spectrometer (EQUINOX 55, Bruker, Germany), with method of the mid-infrared spectroscopy. Spectroscopic measurements were performed using 1:10 dilution of dry phage powder to potassium bromide (KBr). Diffusive reflectance of the IR was recorded with average of 32 scans at a resolution of 4 cm−1 for dry phage powder from a formula using trehalose alone and an optimal formulation, and with average of 64 scans at a resolution of 8 cm−1 for dry phage powder from a formula using WPI alone. Background noise was corrected with pure KBr data.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

Glass transition temperatures (Tg) and was determined using a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC-7, Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, CT, USA) as described by Schuck et al. (2005) with modifications. Temperature calibration was performed using the Indium thermogram. Approximately 5 mg of samples were accurately weighed into aluminum pans, hermetically sealed, and twice scanned over the temperature range of 0–250 °C with a heating rate of 5 °C/min and cooled rate 10 °C/min. Liquid nitrogen was used as the cooling medium. The empty aluminum pan was used as a reference.

Stability of dry phage powder compared to non-encapsulated phage (lysate) at various temperatures

Comparison of the stability of dry phage powder (1 g) and the non-encapsulated phage (1 ml of phage lysate) was performed. Each form was separately mixed with 10 ml of PBS, followed by incubation individually at different temperatures: 4 °C, room temperature (25 °C) and 50 °C. Suspension from each temperature was taken after 1, 8, 16 and 24 h, followed by determination of phage survivability by plaque forming unit counting in duplicates as mentioned above. The study was performed over a period of 24 h to evaluate if encapsulated phages in the powder form will survive at different temperatures and show enough numbers for the next cycle for infections on the bacterium host cells.

Stability of dry phage powder compared to non-encapsulated phage (lysate) at various pH

Dry phage powder and the non-encapsulated phage (lysate) were evaluated for phage survivability with five pH levels: 1.5, 3.5, 5.5, 7.5, and 9.5. To prepare a solution, 0.5–1 M HCl or NaOH were used to adjust to lower/higher pH. Dry phage powder 1 g or non-encapsulated phage (1 ml of phage lysate) was transferred individually to 10 ml of each prepared solution, followed by incubation at room temperature for 5 h. Suspension from each pH was taken after 1, 3 and 5 h, followed determination of phage survivability by plaque forming unit counting as mentioned above in duplicates.

Antimicrobial efficacy of dry phage powder in vitro

Overnight culture of S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium were prepared and diluted in TSB to achieve the level of 104 CFU/ml in 5 ml of culture. Each overnight culture was mixed with 5 ml of phage suspension that was prepared by mixing 1 g of phage powder (titer 106 PFU/g or 104 PFU/g) in 5 ml of TSB to obtain the phage titers of 106 PFU/ml and 104 PFU/ml to achieve the MOI of 100 and 1, respectively. By using known %EE, the dry phage powder was previously prepared to contain phage titer of 106 PFU/g and 104 PFU/g for the MOI of 100 and 1, respectively. Controls for each MOI of a given serovar were prepared by mixing 5 ml of a given overnight culture with a phage-free powder suspension (1 g of the combined wall materials without phages) to rule-out any sugar or protein-driven inhibition phenomena. All phage co-culture and control samples were incubated at 10 °C and 30 °C with shaking at 220 rpm. Each sample was taken after 1, 8, 16, and 24 h of incubation and tenfold serial dilution was performed in PBS. Appropriate dilutions were used for enumeration of surviving Salmonella cells by TSA.

Experimental design and statistical analysis

Matrix of experiments was designed based on two materials, resulting in seven combinations (9 formulations) as listed in Table S1. Design was generated by using Design-Expert®7 trial version software (Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, USA). The simplex lattice mixture design (SLMD) was used to evaluate the effect of the ratio of wall material (WPI) and trehalose on the highest phage recovery in the dry powder form. A percentage of EE was considered as a response in this design. Mean comparison of EE from each dry phage powder formulation and phage survivability in the study of phage stability in various pH and temperatures were carried out by Duncan’s multiple range tests (DMRT). Significance was declared at p < 0.05 using the statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS 10.0 for windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results and discussion

Effects of WPI and trehalose on phage survival upon freeze-drying

Structure of phages is known to have phage genome surrounded by the protective coating (capsid) which is the encoded protein (Drulis-Kawa et al. 2015). Freeze-drying condition can cause stress leading to irreversible structural changes, protein aggregation and phage destabilization (Merabishvili et al. 2013). Cryo- and lyo-protectant is necessary to increase phage survivability from harsh conditions (Merabishvili et al. 2013). The encapsulation efficiency (EE) based on phage survivability after freeze-drying was compared among the 9 formulations and presented the range from 57.1 and 91.9% (Table S1). Phages encapsulated with only a protectant (trehalose) showed the lowest EE, whereas the highest EE was observed in a formulation with a ratio of 3:1 for WPI to trehalose. This ratio indicates an optimal formulation as indicated by the highest survival rate for encapsulated phages after freeze-drying. Overall, this study reported for the optimal formulation using a combination of WPI and trehalose to maintain the phage survivability in a dry phage powder form. As low temperatures from freeze-drying condition can cause the denaturation of protein (Wang 2000). Trehalose could play an important role in anhydrobiotic protection, avoiding water crystallization during dehydration–rehydration cycles that could damage phage particles (Malferrari et al. 2014). Trehalose has been shown the ability to protect other living cells, including probiotics or mammalian cells through spray-drying or freeze-drying conditions (Zhang et al. 2017). Phages exhibit the amphipathic structural protein, consisting of a negatively charged of the phage head (capsid) and a positively charged of the tail fiber (Anany et al. 2011). The networks of H-bonds under a simultaneous H-bonding can connect surface protein groups and disaccharide molecules of trehalose and thus forming the protein–matrix interface (Malferrari et al. 2014).

Component analysis by ANOVA revealed the final equation in terms of EE as: + 88.7610* A + 57.51162 * B + 35.69431 * A * B, where A is WPI and B is trehalose. This equation suggests that the EE was influenced by all factors (WPI, trehalose and the interaction between WPI and trehalose). However, WPI represented the most influence factor as indicated by its higher co-efficient factor which can positively affect the EE. This can be hypothesized that WPI plays more important role to protect phage from freeze-drying as compared to trehalose. Protein possess the ability to interact, protect, and reverse binding with a wide range of active compounds through their functional groups. In addition, denatured whey protein can enhance living cells survivability through microencapsulation technique compared to using of nature whey protein (Doherty et al. 2011).

Structure, size and surface characteristics of dry phage powder

Phage powder sample from WPI alone (Fig. 1a) showed rough surface with pores and cracks of various sizes. For trehalose alone (Fig. 1b), phage powder showed smooth crystal surface as present in a normal form of saccharides. Dry phage powder from a combination of WPI and trehalose showed smaller pore size and less cracks (Fig. 1c) as compared to powder from only WPI. Surface of the powder was smooth and more compact as WPI and trehalose are soluble and can form a thin layer after the water evaporates. Our dry phage powder formulation showed the similar morphology though SEM with spray-freeze dried WPI/fructooligosaccharide (FOS) (Rajam et al. 2015). Indicating the compacted structure of protein and saccharide.

Fig. 1.

SEM images of dry phage powder samples: a WPI alone, b trehalose alone and c optimal formulation. Magnification of × 500

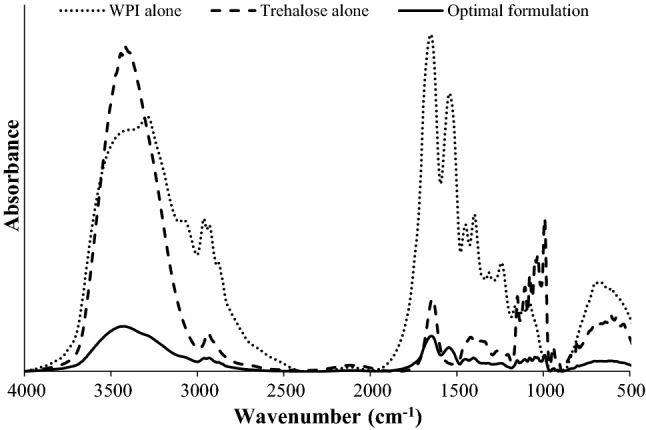

Infrared spectra of dry phage powder

Dry phage powder made of WPI alone showed typical bands of amide A (3300 cm−1), amide B (3100 cm−1), amide I (1650 cm−1), amide II (1550 cm−1), amide III (1200–1300 cm−1) and amide VI (620–700 cm−1) (Fig. 2). Distinct bands at 980 cm−1, and 900 cm−1 were observed in phage powder from trehalose alone. Bands at 983 cm−1 and 931 cm−1 may correspond to the two vibrational modes (antisymmetric and symmetric stretching) of α-(1↔1)-glycosidic bond or C–O–C vibration (Akao et al. 2001). Moreover, this formulation showed a specific band at 3400 cm−1 which is associated with the H–O–H bending motion. Phage powder from an optimal formulation using a combination of WPI and trehalose showed unexpected bands at 3300–3500 cm−1 and 1750–1800 cm−1. The stretching might be representative of interaction between WPI and trehalose (Akao et al. 2001) and H-bonding between sugar–protein. In a previous study, H-bond interaction between the carboxylate group of sugar and the amide group of protein after freeze-drying was observed in dried lysozyme with sugar (Carpenter and John 1989). Results from the FTIR analysis indicated that the materials (phage, WPI, and trehalose) mixed as dry phage powder developed in this study correlated as the matrix microcapsule (a type of microcapsule morphology) by various bonding (Raybaudi-Massilia and Mosqueda-Melgar 2012).

Fig. 2.

Fourier transform infrared spectra of dry phage powder with different formulations

Glass transition temperatures of dry phage powder

Glass transition temperature (Tg) is generally referred to the temperature at which the material in amorphous system changes from the glassy to the rubbery state. Food industry uses this parameter to indicate the stability of food ingredient (Abbas and Sahar 2010). The Tg of dry phage powder of three formulations was evaluated by DSC analysis. In this study, Tg values of dry phage powder from WPI alone and trehalose alone were found at 54.08 °C and 95.39 °C, respectively (Fig. 3). Phage powder made of the optimal formulation with WPI and trehalose showed Tg value of 63.43 °C. Non-crystallized whey powder showed Tg at 51 ± 1 °C, while crystallized whey powder has showed Tg at 44 ± 1 °C when tested at 11% of relative humidity (Schuck et al. 2005). The Tg of pure dry trehalose was found to be 106 °C (Roe and Labuza 2005). Overall, WPI/traholose combination for phage powder suggests an improved Tg as compared to the control formulation of WPI alone. This can prevent the changed form of materials to be the undesirable characteristic, thus providing a high stability of the phage powder during storage at the temperature under Tg. Results indicated that the formulation should exist in the glassy state in order to avoid the aggregation of formulation during the shelf-life. The physical property of formulation of dry phage powder developed in this study is in agreement with a previous report that indicated that increasing of protein/sugar ratio could increase the Tg of the formulation containing sucrose and trehalose (Duddu and Dal Monte 1997). Overall, the combination of protein- and saccharide-based provided the remarkable physical property of food material that can be useful for further food application.

Fig. 3.

Differential scanning calorimetry of dry phage powder from different formulations

Stability of dry phage powder at various temperatures and pH levels

At 4 °C and 25 °C, wall materials made of the optimal formulation, WPI alone and trehalose alone could protect phage particles in the solutions up to 95–100% for 24 h (Fig. 4). Similarly, lysate in the non-encapsulated form showed survivability up to 100% at 4 °C and 98% at 25 °C during 24 h. At 50 °C, the phage survivability was maintained at 100% during 24 h by the wall materials formulated with the optimal formulation, WPI alone and trehalose alone. However, phage in the non-encapsulated form could survive at 63% for 1 h. Similar to our result, encapsulated Salmonella phages Felix O1 in the system of chitosan-alginate showed high survival rate after exposure to simulated gastric fluid (pH 2.4) for 90 min of incubation at 37 °C (Ma et al. 2008). Overall, titer of phages encapsulated by the optimal formulation was remained in a system over a wide range of pH.

Fig. 4.

Stability and solubility of dry phage powder at 4 °C, room temperature (25 °C) and 50 °C, for 1, 8, 16, and 24 h. Different formulations: a WPI alone, b trehalose alone, c optimal formulation and d non-encapsulated phage. Bars represent the mean standard deviation (n = 3). Different uppercase letters on the bars within the same temperature indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between periods of time. Different lowercase letters on the bars within the same time period indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between temperature. Non-significant differences between temperature and time period of b, c (p > 0.05)

Wall materials formulated with the optimal formulation and WPI alone could protect the phage particles up to 90% after 5 h of exposure to pH 1.5 (Fig. 5). However, no phage titer was remained in the phage powder from trehalose alone or phage lysate in the non-encapsulated form after 1 h of exposure. At pH 3.5 and 5.5, wall materials formulated with the optimal formulation, WPI alone and trehalose alone could protect the phage particles up to 90% and 95%, respectively after 5 h of exposure. The phage titer in the non-encapsulated form was reduced to approximately 85% and 73%, respectively after 3 h of exposure. At higher pH (9.5), wall materials formulated with the optimal formulation, WPI alone and trehalose alone could protect the phage particles up to 90% after 5 h of exposure. The phage titer in the non-encapsulated form was reduced to approximately 86% after 3 h and no phage particles could be determined after 5 h of exposure. Our finding is in agreement with several previous studies which suggested the use of encapsulation technique to protect and improve phage stability in the harsh conditions (Ma et al. 2008). Encapsulation of phage by whey protein as edible films could be stabilized at both ambient (22 °C) and refrigerated (4 °C) temperatures for more than 1 month (Vonasek et al. 2014).

Fig. 5.

Stability of dry phage powder at pH 1.5, 3.5, 5.5, 7.5, and 9.5 for 1, 3, and 5 h. Different formulations: a WPI alone, b trehalose alone, c optimal formulation and d non-encapsulated phage. Bars represent the mean standard deviation (n = 3). Different uppercase letters on the bars within the same pH indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between periods of time. Different lowercase letters on the bars within the same time period indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between levels of pH

Efficacy of dry phage powder against S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium in vitro

At 10 °C, the cell numbers of S. Enteritidis were decreased by approximately 1 log CFU/ml for the MOI 100 within 24 h (Fig. 6). Similarly, the cell numbers of S. Typhimurium were decreased by approximately 1 log CFU/ml within 24 h for both MOIs (100 and 1). At 30 °C, the cell numbers of both S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium were decreased by approximately 1 log CFU/ml within 24 h for both MOIs. This study is the first study that introduces a new form of phage-based bio-control as a powder (lysate-free form) for use to control a bacterial pathogen. The MOIs included in this study that were lower as compared to those used in previous studies may have limited the overall cell reductions. Previous studies have been investigated the efficacy of Salmonella phage lysate in the reduction of S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium at various temperatures. The decrease of S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium in processed food (packaged lettuce) by 2.2 and 3.9 log CFU/g, respectively was reported from phage cocktail treatment at the MOI of 104 at room temperature. On chicken breast treated with a phage cocktail at MOI of 1000 at 4 °C, up to 2.2 log CFU/g reduction was observed (Spricigo et al. 2013). Overall, results indicated that microencapsulated phage powder made from the optimal formulation using WPI/trehalose combination could reduce S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium. Using a phage cocktail with the optimal formulation reported in this study prior to freeze-drying condition and application of higher MOI can further improve the overall reduction of S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium in food products.

Fig. 6.

Efficiency of dry phage powder from the optimal formulation against S. Enteritidis at 10 °C (a) and 30 °C (b) and S. Typhimurium at 10 °C (c) and 30 °C (d). MOIs include:  (MOI 100) and

(MOI 100) and  (MOI 10). Controls include:

(MOI 10). Controls include:  (control of MOI 100) and

(control of MOI 100) and  (control of MOI 10). Bars represent the mean standard deviation (n = 3). Different uppercase letters on the time point within the same periods of time indicated significant differences (p < 0.05) between each MOI and control

(control of MOI 10). Bars represent the mean standard deviation (n = 3). Different uppercase letters on the time point within the same periods of time indicated significant differences (p < 0.05) between each MOI and control

Conclusion

The combination of WPI/trehalose at 3:1 (w/w) was the optimal formulation which provided the highest phage survivability in the powder form upon freeze-drying in this study. Microstructure showed the complex particles of both wall materials (WPI and trehalose), which binding with H-bond presented by FTIR analysis. The result from DSC analysis showed that microencapsulated phage powder presented Tg at 63.43 °C which is the indication of phage stability as a dry powder over room temperature. Moreover, this newly developed dry phage powder form could protect phage particles from various temperatures and wide range of pH conditions. Encapsulated phage with the optimal formulation also showed the efficiency in reduction of S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium by approximately 1 log unit. Finding suggests that dry phage powder can be used to prepare as a suspension with water as the aqueous carrier before spraying on surfaces of various food products or environments that represent various temperatures and pH levels in order to control Salmonella contamination. These results highlight the newly developed formulation of dry phage powder as bio-control against Salmonella contamination in food production chain.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This project is funded by Prince of Songkla University (AGR570552S to KV) and TRF Distinguished Research Professor Grant (to SB). The Ph.D. scholarship from the Graduate School of Prince of Songkla University (to KP) is also acknowledged.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: KP, KV. Data curation: KP, KV. Formal analysis: KP. Funding acquisition: KV. Investigation: KP, KV. Methodology: KP, SB, KV. Project administration: KV. Resources: SB, KV. Supervision: SB, KV. Validation: KP, KV. Visualization: KP, SB, KV. Writing—original draft: KP. Writing—review and editing: KP, SB, KV.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abbas KA, Sahar K. The significance of glass transition temperature in processing of selected fried food products. Mod Appl Sci. 2010 doi: 10.5539/mas.v4n5p3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann H, Tremblay D, Moineau S. Long-term bacteriophage preservation. WFCC Newsl. 2004;38:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Akao K, Okubo Y, Asakawa N, Inoue Y, Sakurai M. Infrared spectroscopic study on the properties of the anhydrous form II of trehalose. Implications for the functional mechanism of trehalose as a biostabilizer. Carbohydr Res. 2001;334:233–241. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(01)00182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin T, Thakur M, Jain SC. Microencapsulation the future of probiotic cultures. J Microbiol Biotechnol Food Sci. 2013;3:35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Anany H, Chen W, Pelton R, Griffiths MW. Biocontrol of Listeria monocytogenes and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in meat by using phages immobilized on modified cellulose membranes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(18):6379–6387. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05493-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter HJ, John CF. An infrared spectroscopic study of the interactions of carbohydrates with dried proteins. Biochemistry. 1989;28(9):3916–3922. doi: 10.1021/bi00435a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty SB, Gee VL, Ross RP, Stanton C, Fitzgerald GF, Brodkorb A. Development and characterisation of whey protein micro-beads as potential matrices for probiotic protection. Food Hydrocolloid. 2011;25(6):1604–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2010.12.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drulis-Kawa Z, Majkowska-Skrobek G, Maciejewska B. Bacteriophages and phage-derived proteins—application approaches. Curr Med Chem. 2015;22(14):1757–1773. doi: 10.2174/0929867322666150209152851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duddu SP, Dal Monte PR. Effect of glass transition temperature on the stability of lyophilized formulations containing a chimeric theraeutic monoclonal antibody. Pharm Res. 1997;14(5):591–595. doi: 10.1023/A:1012144810067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther S, Herzig O, Fieseler L, Klumpp J, Loessner MJ. Biocontrol of Salmonella typhimurium in RTE foods with the virulent bacteriophage FO1-E2. Int J Food Microbiol. 2012;154(1–2):66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Pacan JC, Wang Q, Xu Y, Huang X, Korenevsky A, Sabour PM. Microencapsulation of bacteriophage Felix O1 into chitosan-alginate microspheres for oral delivery. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(15):4799–4805. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00246-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malferrari M, Nalepa A, Venturoli G, Francia F, Lubitz W, Möbius K, Savitsky A. Structural and dynamical characteristics of trehalose and sucrose matrices at different hydration levels as probed by FTIR and high-field EPR. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014;16(21):9831–9848. doi: 10.1039/c3cp54043j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merabishvili M, Vervaet C, Pirnay JP, de Vos D, Verbeken G, Mast J, Chanishvili N, Vaneechoutte M. Stability of Staphylococcus aureus Phage ISP after freeze-drying (lyophilization) PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Switt AI, den Bakker HC, Vongkamjan K, Hoelzer K, Warnick LD, Cummings KJ, Wiedmann M. Salmonella bacteriophage diversity reflects host diversity on dairy farms. Food Microbiol. 2013;36(2):275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petsong K, Benjakul S, Vongkamjan K. Evaluation of storage conditions and efficiency of a novel microencapsulated Salmonella phage cocktail for controlling S. enteritidis and S. typhimurium in vitro and in fresh foods. Food Microbiol. 2019;83:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picot A, Lacroix C. Encapsulation of bifidobacteria in whey protein-based microcapsules and survival in simulated gastrointestinal conditions and in yoghurt. Int Dairy J. 2004;14:505–515. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2003.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puapermpoonsiri U, Ford SJ, Van Der Walle CF. Stabilization of bacteriophage during freeze drying. Int J Pharm. 2010;389(1–2):168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajam R, Kumar SB, Prabhasankar P, Anandharamakrishnan C. Microencapsulation of Lactobacillus plantarum MTCC 5422 in fructooligosaccharide and whey protein wall systems and its impact on noodle quality. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52(7):4029–4041. doi: 10.1007/s13197-014-1506-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raybaudi-Massilia RM, Mosqueda-Melgar J. Polysaccharides as carriers and protectors of additives and bioactive compounds in foods. In: Desiree NK, editor. The complex word of polysaccharides. Rijeka: InTech; 2012. pp. 429–453. [Google Scholar]

- Roe KD, Labuza TP. Glass transition and crystallization of amorphous trehalose-sucrose mixtures. Int J Food Prop. 2005;8(3):559–574. doi: 10.1080/10942910500269824. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck P, Blanchard E, Dolivet A, Méjean S, Onilion E, Jeantet R. Water activity and glass transition in dairy ingredients Pierre. Lait. 2005;85:295–304. doi: 10.1051/lait. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spricigo DA, Bardina C, Cortés P, Llagostera M. Use of a bacteriophage cocktail to control Salmonella in food and the food industry. Int J Food Microbiol. 2013;165(2):169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ven C, Muresan S, Gruppen H, De Bont DBA, Merck KB, Voragen AGJ. FTIR spectra of whey and casein hydrolysates in relation to their functional properties. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50(24):6943–6950. doi: 10.1021/jf020387k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonasek E, Le Ph, Nitin N. Encapsulation of bacteriophages in whey protein films for extended storage and release. Food Hydrocolloid. 2014;37:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2013.09.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. Lyophilization and development of solid protein pharmaceuticals. Int J Pharm. 2000;203:1–60. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(00)00423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongsuntornpoj S, Moreno Switt AI, Bergholz P, Wiedmann M, Chaturongakul S. Salmonella phages isolated from dairy farms in Thailand show wider host range than a comparable set of phages isolated from U.S. dairy farms. Vet Microbiol. 2014;172(1–2):345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Oldenhof H, Sydykov B, Bigalk J, Sieme H, Wolkers WF. Freeze-drying of mammalian cells using trehalose: preservation of DNA integrity. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s100169900234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.