Abstract

The crosstalk between tumor cells and the tumor microenvironment (TME), triggers a variety of critical signaling pathways and promotes the malignant progression of cancer. The success rate of cancer therapy through targeting single molecule of this crosstalk may be extremely low, whereas co-targeting multiple components could be complicated design and likely to have more side effects. The six members of cellular communication network (CCN) family proteins are scaffolding proteins that may govern the TME, and several studies have shown targeted therapy of CCN family proteins may be effective for the treatment of cancer. CCN protein family shares similar structures, and they mutually reinforce and neutralize each other to serve various roles that are tightly regulated in a spatiotemporal manner by the TME. Here, we review the current knowledge on the structures and roles of CCN proteins in different types of cancer. We also analyze CCN mRNA expression, and reasons for its diverse relationship to prognosis in different cancers. In this review, we conclude that the discrepant functions of CCN proteins in different types of cancer are attributed to diverse TME and CCN truncated isoforms, and speculate that targeting CCN proteins to rebalance the TME could be a potent anti-cancer strategy.

Keywords: CCN proteins, isoforms, targeted therapy, tumor microenvironment, pan-cancer

Introduction

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States and is becoming a major public health problem and central focus of modern medical research in China (Arbyn et al., 2020). Although early diagnosis and surgical resection are primary anti-tumor strategies, the prognosis of cancer patients remain generally dismal, with unfavorable outcomes attributed to the high frequency of tumor recurrence, metastasis and therapeutic resistance (Winkler et al., 2020). Therefore, continued identification of new molecules for the development of molecular targeted therapy is still urgently needed (Jiang et al., 2019). An increasing body of research suggests that crosstalk between tumor cells and the tumor microenvironment (TME), including revascularization, immune tolerance, fibrotic components and many cytokines, trigger a variety of critical signaling pathways and promotes the malignant progression of cancer in an integrated manner. Thus, the efficacy of targeting single molecule in cancer therapy may be low, whereas combination therapy could be more benefit for human cancers (Palmer and Sorger, 2017). Here, we present a scaffolding-like protein family that can bind with a variety of molecules and exhibit a multi-target regulatory effects through orchestrating the TME and intracellular signaling pathways.

Cellular communication network (CCN) family are scaffolding proteins that may govern and balance the interconnection among individual signaling pathways. CCN proteins, first described in 1993, are a six-member family of cysteine-rich regulatory proteins that exist only in vertebrates, including CCN1 (cysteine-rich 61, CYR61), CCN2 (connective tissue growth factor, CTGF), CCN3 (nephroblastoma overexpressed, NOV), CCN4 (Wnt1-inducible signaling pathway proteins, WISP-1), CCN5 (WISP-2), and CCN6 (WISP-3). CCN proteins do not behave like individual cytokines in that they do not perform a single function but instead coordinate in various functions of extracellular and intracellular proteins (Perbal, 2018). All CCN proteins serve as extracellular, cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins in their full-length and/or truncated forms and play key roles in regulating tumor cellular function and crosstalk with the TME (Brigstock, 2003). Thus, targeting CCN proteins expression hold promise for remodeling the TME and rebalancing intracellular signaling pathways (Jun and Lau, 2011; Jia et al., 2016).

Although CCN proteins were discovered three decades ago, they have not received widespread interest, and their roles and modes of action in human cancers are still ambiguous. CCN protein members always appear to have paradoxical effects across different types of cancer (Li et al., 2016) and even within the same cancer (Kleer, 2016), and which were often due to the diverse TME. Thus, summative work and further investigations are urgently needed to dissect the actions of CCN proteins considering the diverse TME and their multifunctional domains. Here, we review the current knowledge on the structures and roles of CCN proteins in different types of cancer. We also analyze CCN mRNA expression, its relationship to prognosis, and its isoforms in pan-cancer based on The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) using the bioinformatics tool GEPIA2 (Tang et al., 2019). We conclude that the contradictory nature of the biological properties of CCN proteins in cancer are attributed to their multiple functional domains, which allow them to act as multifunctional regulators in the TME and cancer signaling pathways, and speculate that targeting CCN proteins could be a potent anti-cancer strategy, and the efficacy of which is orchestrated by the different location and existence of diverse ligands.

Structures and Functions of Full-Length CCN Proteins in Cancer

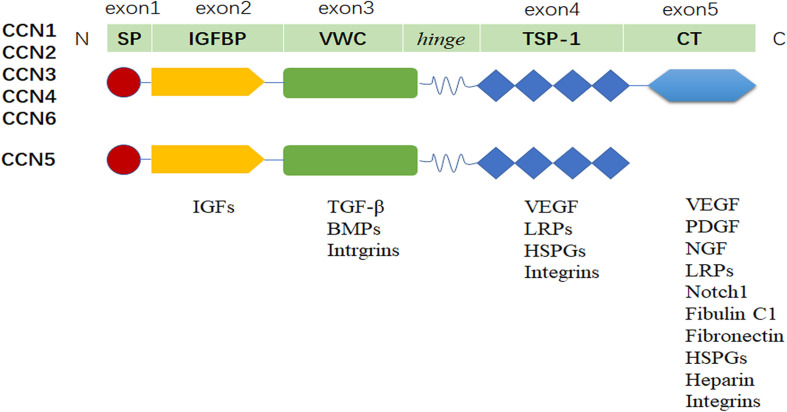

CCN proteins are secreted proteins, with full-length CCN proteins consisting of a signal peptide for extracellular release followed by four structural domains (with CCN5 lacking the CT domain): IGFBP, VWC, TSP-1, and CT (Perbal and Perbal, 2016). Prototypic CCN proteins are encoded by five exons. Exon 1 encodes a signal peptide, and exons 2– 5 encode IGFBP, VWC, TSP-1, and CT modules, respectively. CCN proteins exhibit similar structure with 60% amino acid homology, and share a series of 38 cysteine residues that are strictly conserved in position and number. Owing to the signal peptide, CCN proteins are characteristically expressed in the cytoplasm and accumulate in the external environment in the form of paracrine. Their four discrete functional domains determine the types of binding ligands with which they interact, including diverse integrins, HSPGs, IGFs, TGFβ, VEGF, and LRPs et al., resulting in a variety of biological functions of full-length CCN proteins (Perbal, 2004; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Structure of CCN proteins. Schematic of four conserved functional domains coded by associated exons. CCN proteins could serve different functions via interactions with a variety of cell surface receptors and extracellular ligands (e.g., integrins, HSPGs, LRPs, TGFβ, VEGF, and PDGF).

CCN proteins are multifunctional regulatory molecules in the TME that are involved in many vital biological functions, including angiogenesis, fibrosis, tissue regeneration and repair, and cancer (Yeger and Perbal, 2016). The diverse functions of CCN proteins in the TME are attributed to their modular structural features, which allow binding and interactions with well-known functional ligands (Holbourn et al., 2009). CCN proteins also serve as cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins in their truncated forms and play key roles in regulating tumor cellular function. Thereof, CCN proteins physically located at the center of communication network and exhibit diverse functionalities (Perbal, 2019).

Multi-Domain Structure of Full-Length CCN Proteins

IGFBP Domain in CCN Proteins

The insulin-like growth factor-binding protein (IGFBP) domain of CCN proteins is found in every CCN family members, and shares strong sequence homology to the N-terminal domain of traditional IGFBPs, which bind to and influence the actions of IGFs (Perbal, 2018). Although its IGF binding ability is lower than that of full-length IGFBPs, the IGFBP domain of CCN3 reduces activation of IGF1-IGF1R signaling in inflammatory breast cancer, and downregulation of CCN6 enhances the effects of IGF1 on growth, motility, and invasiveness (Kleer et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2005). Repudi et al. (2013) reported that CCN6 not only co-localizes with IGF1 but also blocks IGF1 secretion. Different CCN family members exhibit diverse IGF binding ability, in CCN3, the IGFBP domain cannot substitutes for the IGFBP3 amino-proximal sequence for IGF binding (Yan et al., 2006). Up to now, little information is available concerning the exact roles played by the IGFBP domain in CCN function, but the direct and indirect control of IGF function implicates CCN proteins could be a promising intervention strategy.

VWC Domain in CCN Proteins

The Von Willebrand factor type C (VWC) domain is also found in every CCN family member, and the VWC domain most commonly binds to bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs) (Canalis, 2007), TGF-β (Inkson et al., 2008), and diverse integrins (i.e., αMβ2, α2β1, αvβ5, α5β1, α6β1) (Kaur and Roberts, 2021). In CCN2, its interaction with TGF-β enhances TGF-β signaling, such that CCN2 might function as a chaperone for TGF-β, and less TGF-β is required to stimulate downstream signaling (Abreu et al., 2002). In CCN3, its interaction with BMP2 inhibits BMP2-induced osteoblast differentiation (Minamizato et al., 2007). Integrins, the primary signaling receptors of CCN proteins, consist of α- and β-subunits that are commonly transmembrane (Karimi et al., 2018). The VWC domain in CCN proteins binds with various integrin subtypes that differ across CCN family members, thereby mediating different forms of cell adhesion and activating signaling pathways in tumor and stromal cells (Li et al., 2015). The ability of the VWC domain to bind with functional ligands suggests that it plays a key role in some biological functions associated with CCN proteins. In considering the interactions between the VWC domain in CCN proteins and TGF-β, BMP-4 et al., the CCN proteins could also be a potential target for cancer therapy, while the specific roles are depended on the type and number of ligands in the TME.

TSP-1 Domain in CCN Proteins

The thrombospondin type 1 repeat (TSP-1) domain is another common domain in CCN proteins and plays strong roles in some biological functions of tumor, primarily through interactions with lipoprotein-related receptors (Gerritsen et al., 2016), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Tsai et al., 2017), diverse integrins (Alday-Parejo et al., 2019), and heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) (Neubauer et al., 2017). As the TSP-1 domain is conserved across CCN family members, this suggests that all CCN family members modulate cell adhesion, maintains ECM composition, and participates in regulating tumor signaling (Jayakumar et al., 2017). Indeed, some studies have linked CCN proteins with mutant or missing TSP-1 domains with colorectal and gastric carcinomas (Perbal, 2016) and Wilm’s tumors (Subramaniam et al., 2008). Therefore, the TSP-1 domain, like other CCN domains, could be a potential target of cancer therapy (Leask, 2020).

CT Domain in CCN Proteins

The carboxyterminal (CT) domain is thought to mediate key functions in several CCN proteins (except CCN5), because it also acts as a dimerization module in a manner analogous to domains in other molecules, such as nerve growth factor (NGF), TGF-β, VEGF, BMPs, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and diverse integrins. In addition, many biological functions of cytokines arise through their interactions with heparin (Crijns et al., 2020). Interestingly, many basic residues at the CT domain in N-terminus follow the heparin-binding pattern, suggesting heparin as a candidate for CCN protein-targeted therapy (Jia S. et al., 2017). Its interactions with Notch, lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6), and integrin α6β1 suggest that CCN proteins regulate cellular differentiation and proliferation (Thakur and Mishra, 2016). Furthermore, CT domain-mediated dimerization likely influences other domains in CCN proteins, such as VWC domain (Perbal, 2006b). Together, these reports indicate that the CT domain of CCN proteins plays a crucial role in regulating tumor biology.

Functions and Progress of Full-Length CCN Proteins in Tumor Progression

CCN Proteins Acting as Critical Modulators of the TME

One fascinating aspect of TME that adds to the complexity of tumor progression. CCN proteins can be potential therapeutic targets that can be manipulated to rebalance the TME. Recently, Tao et al. proved that CCN4 was preferentially secreted by glioma stem cells (GSCs), and which played critical roles in maintaining GSCs and tumor-supportive macrophage (Tao et al., 2020). Jia et al. also proved CCN4-induced type I collagen linearization facilitates tumor cell invasion and promotes spontaneous breast cancer metastasis, without significantly affecting gene expression (Jia et al., 2019). CCN2 and its fragments also have been implicated in the regulation of a multitude of biological phenomena in cancers, which was not only associated with fibrosis, but also with mesenchymal stem cells (Leguit et al., 2021). Different CCN proteins also enhance or suppress each other’s action in the TME (Peidl et al., 2019). The available evidence strongly supports that CCN proteins are related to the tumor progression, while the same CCN proteins play different roles in the same type of cancer, and the reason is related to the complexity of the TME (Li et al., 2015; Yeger and Perbal, 2016). Based on these, the final biological properties of the CCN proteins might be dependent on different combinations, and the cocktail containing CCN proteins in different combinations should be applied to rebalance the TME in tumor therapy.

CCN Proteins Acting as Direct Modulators of Tumor Progression

Recently, CCN members also play direct roles in tumor progression through diverse signaling pathways. CCN1 has been shown to promotes cell adhesion and migration as a mediator of Notch1 signaling in breast cancer (Ilhan et al., 2020). Overexpression of CCN2 also has been shown to induce the upregulation expression of Wnt/β-catenin transcriptional target genes, and our group also proved CCN2 was associated with the Wnt signaling activation in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (Jia S. et al., 2017). CCN3 has been proved to promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) via FAK/Akt/HIF-1α/twist signaling in prostate cancer (Chen et al., 2017). CCN4 also has been proved to stimulates melanoma invasion and metastasis by promoting EMT-like process (Deng et al., 2019). CCN5 is a tumor suppressor, which restored ER-α expression at the transcription level via integrins-α6β1/Akt/FOXO3a signaling activation in breast cancer (Sarkar et al., 2017). CCN6 is also acts as a tumor suppressor in HCC by negative regulation of β-catenin/TCF/LEF signaling (Gao et al., 2019). Because of the four functional domains of CCN proteins, CCNs mediate tumor progression primarily through binding and interacting with well-known receptors, including integrins, HSPGs, IGFs and LRPs relating the signaling pathways such as Wnts, TGF-β, and Notch signaling et al. (Li et al., 2015).

Functions and Progress of Truncated CCNs Associated With Cancer Progression

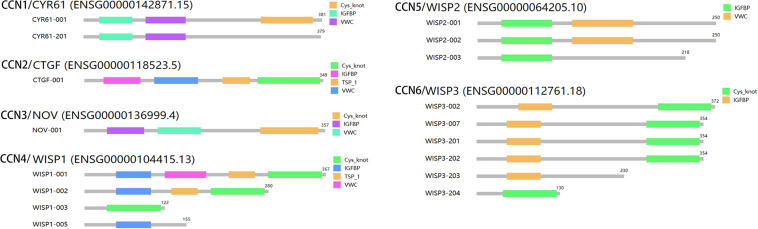

CCN proteins lacking one or more of the functional domains can be produced by alternative splicing (Perbal, 2009) or post-translational processing (Viloria and Hill, 2016). The existence of CCN isoforms may have different activities than full-length CCNs and may be regarded as a means of increasing the diversity of their biological roles in cancer (Kaasboll et al., 2018). Our GEPIA2 analysis provides the schematic organization of various CCN isoforms (Figure 2). Despite compelling evidence of the important biological activities of these CCN isoforms, their potential regulatory functions are still vague. Truncated CCN proteins deprived of a signal peptide commonly exist in cytoplasm and/or nucleus have been identified in several physiology and pathological situations (Perbal, 2006a; Planque et al., 2006). Nuclear localization of truncated CCN proteins could serve as a transcriptional factors. Also, their nuclear localization could be influenced by their CT domain (Bleau et al., 2007). Therefore, the existence of truncated CCN proteins could be an important means to discovering their diverse biological functions in different types of cancer. However, the intracellular localization and diverse function of truncated forms of CCN proteins are still unclear and has been a primary research focus of our group.

FIGURE 2.

Isoform structures of CCN family members were obtained from GEPIA2 based on the TCGA/GTEx data. Truncated isoforms of different CCN family members indicate diverse biological functions with based on their different functional domains.

Diverse Expression and Roles of CCN Family Members in Pan-Cancer

Although all CCN family members (except CCN5) have four highly conserved functional domains, they have different roles within particular types of cancer. Some CCN proteins have established associations with cancer malignancy progression and are considered as prognostic markers and therapeutic targets for certain types of cancer (Jun and Lau, 2011). However, CCN proteins always appear to have contradictory roles in different types of cancer, which may be due to differences in their TMEs and isoforms (Peidl et al., 2019; Figure 2 and Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Roles of CCN1-6 in pan-cancer.

The numbers in brackets are reference numbers. ↑ CCN acting as tumor promotor; ↓CCN acting as tumor suppressor.

Expression and Roles of CCN1 in Pan-Cancer

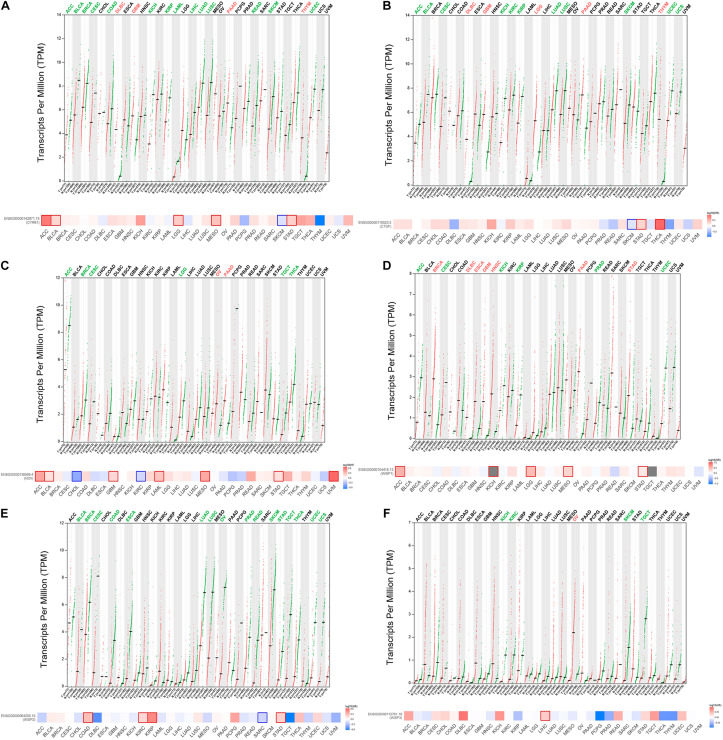

CCN1 exhibits varying mRNA levels and associations with prognosis across different types of cancer. Comparisons of CCN1 mRNA levels among 32 human cancer types and adjacent normal tissue using GEPIA2 revealed significantly upregulated CCN1 expression in four types of cancer [lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBC), glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD), and thymoma (THYM)] and significantly downregulated expression in 14 types of cancer [adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC), bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA), breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA), cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma (CESC), colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), kidney chromophobe (KICH), kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP), acute myeloid leukemia (LAML), liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), rectum adenocarcinoma (READ), skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM), and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC)]. To evaluate the association between CCN1 mRNA expression and prognosis, we also examined 32 human cancers using GEPIA2. The relationship between CCN1 expression and prognosis varied across different types of cancer. High expression of CCN1 was associated with shorter overall survival (OS) in five types of cancer [ACC, BLCA, brain lower grade glioma (LGG), mesothelioma (MESO), and stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD)] and longer OS only in SKCM, suggesting its role as a tumor suppressor. These bioinformatics results revealed the heterogeneous expression and functions of CCN1 in different types of cancer (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 3.

mRNA levels of CCN1-6 differ between human pan-cancer and normal tissue, suggesting their potential role as prognostic and therapeutic biomarkers. (A) CCN1 expression and association with OS. (B) CCN2 expression and association with OS. (C) CCN3 expression and association with OS. (D) CCN4 expression and association with OS. (E) CCN5 expression and association with OS. (F) CCN6 expression and association with OS. For gene expression profile dot plot, color-coded cancers’ abbreviation suggests significant results (p < 0.05) and red mean gene over expressed in cancer tissue compared with the normal tissue, while green have reversed meaning. For survival heat map, blocks with border suggest significant results (p < 0.05) and red blocks mean high expression of CCNs has a poor prognosis, while blue blocks have reversed meaning.

Several previous studies reported that CCN1 participates in cancer development and can serve as both a tumor suppressor and promoter (Barreto et al., 2016). In most types of cancer, CCN1 acts as an oncogene (Tan et al., 2009; Xie et al., 2011, 2019; Niu et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2015; Su et al., 2019; Khandelwal et al., 2020). By contrast, in esophageal (Dang et al., 2018), liver (Feng et al., 2008), prostate (D’Antonio et al., 2010), lung (Tong et al., 2001), and endometrial (Chien et al., 2004) cancer, CCN1 serves as a protective role. Mori et al. reported that CCN1 mRNA level is lower in lung cancer tissue than in normal lung tissue (Mori et al., 2007), consistent with our bioinformatics results. Also, Tong et al. (2001) showed that overexpression of CCN1 in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines reduces colony formation and proliferation, thus serving as a tumor suppressor. As summarized in Table 1, previous, mostly in vitro, studies showed that CCN1 serves as a tumor promoter in most cancers but can also acts as a tumor suppressor in some cancers. Thus, to resolve the discrepant roles of CCN1 in different types of cancer, future studies should take diverse TMEs and different isoforms into consideration.

Expression and Roles of CCN2 in Pan-Cancer

CCN2 mRNA levels and their association with prognosis also vary across different types of cancer. Comparison of CCN2 mRNA levels among different cancer tissues and their adjacent normal tissues revealed significantly higher CCN2 expression in five types of cancer (DLBC, GBM, LGG, PAAD, and THYM) and significantly lower expression in 11 types of cancer [ACC, BLCA, CESC, KICH, KIRC, KIRP, LUAD, LUSC, SKCM, esophageal carcinoma, and uterine carcinosarcoma (UCS)]. When we evaluated associations between CCN2 mRNA levels and prognosis, we found that high expression of CCN2 was associated with shorter OS in STAD and THCA and longer OS only in SKCM, suggesting that it acts as a tumor suppressor. Thus, these bioinformatics results further revealed the heterogeneous expression and function of CCN2 in different types of cancer (Figure 3B).

After reviewing the current studies on CCN proteins. In gastric cancer, high CCN2 expression correlates with more lymph node metastases, more peritoneal dissemination, and poorer 5-year survival (Cheng et al., 2014). After CCN2 downregulation, gastric cancer cells show attenuated migratory/invasive abilities and decreased protein expression of MMPs (Jiang et al., 2011). Recently, Pamrevlumab (FG-3019), a first-in-class antibody that inhibits the activity of CCN2, received fast-track designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer (Ramazani et al., 2018). CCN2 overexpression is related to poor prognosis in most types of cancer (Chien et al., 2004). Even so, there have been plenty of opposite reports in gastrointestinal cancer (Chen et al., 2015), liver cancer (Isbert et al., 2007), lung cancer (Chang et al., 2013), ovarian cancer (Barbolina et al., 2009), and melanoma (Chen J. et al., 2016). Table 1 summarizes the functional roles of CCN2 across different types of cancer.

Expression and Roles of CCN3 in Pan-Cancer

Comparison of CCN3 mRNA levels among different types of cancer tissues and their adjacent normal tissues revealed that CCN3 expression was significantly upregulated in two types of cancer [ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (OV) and PAAD] and significantly downregulated in six types of cancer [ACC, BRCA, CESC, LGG, testicular germ cell tumors (TGCT), and thyroid carcinoma (THCA)]. When we further evaluated the association between CCN3 expression and prognosis in pan-cancer, we found that high CCN3 expression was associated with shorter OS in seven types of cancer (ACC, BLCA, GBM, LAML, MESO, STAD, and uveal melanoma) and longer OS in two types of cancer (CHOL and KIRC, Figure 3C).

CCN3 was first discovered as an overexpressed gene in myeloblastosis-associated virus type-1-induced nephroblastoma (Joliot et al., 1992) and has since been implicated in many diverse biological processes, such as proliferation, differentiation, angiogenesis and fibrosis, all of which promote cancer development (Barreto et al., 2016). CCN3 has anti-tumor effects in breast cancer (Dobson et al., 2014), colorectal tumors (Li et al., 2017), kidney cancer (Liu et al., 2012), glioma (Gupta et al., 2001), and leukemia (McCallum et al., 2012). By contrast, CCN3 acts as a tumor promoter in liver (Jia Q. et al., 2017), pancreatic (Cui et al., 2014), and prostate (Chen et al., 2014) cancer. Laurent et al. (2003) reported that in glioma, CCN3 triggers a cascade of gene expression resulting in increased cell adhesion and migration. Our group showed that CCN3 is a hallmark in the development and chemoresistance of liver cancer (Holbourn et al., 2009; Perbal and Perbal, 2016) via regulation of cell stemness and the TME (Holbourn et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2019). Table 1 provides a summary of CCN3 expression and functional roles in different types of cancer, and the heterogeneous roles of CCN3 are also revealed in different types of cancer.

Expression and Roles of CCN4 in Pan-Cancer

Similar to other CCN family members, CCN4 mRNA levels and their association with prognosis vary across different types of cancer. Comparison of CCN4 mRNA levels among diverse cancer types and adjacent normal tissue revealed significantly higher CCN4 expression in seven types of cancer (BRCA, DLBC, ESCA, GBM, HNSC, PAAD, and STAD). When evaluating the association between CCN4 expression and prognosis in pan-cancer, we found that high CCN4 expression was associated with shorter OS in five types of cancer (ACC, KICH, LGG, MESO, STAD). The results of these bioinformatics analyses suggest that CCN4 mainly acts as a tumor promoter (Figure 3D).

The participation of CCN4 in cancer development has been reported by many previous studies, which showed that CCN4 serves as a tumor promoter in colorectal (Wu et al., 2016), breast (Xie et al., 2001b), pancreatic (Yang et al., 2015), and lung (Chen et al., 2007) cancer by enhancing cell migration and promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). However, in breast (Taghavi et al., 2016), lung (Soon et al., 2003), and liver (Zhang H. et al., 2015) cancer, CCN4 appears to play an opposing role. Davies et al. (2007) showed that CCN4 acts as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer based on examination of mRNA levels in human breast tumor tissues compared with normal tissues. Tao et al. (2020) showed that CCN4 plays dual roles in glioblastoma—both maintaining glioma stem cells and constructing a pro-TME via the infiltration of tumor-supportive macrophages. Zhang X. et al. (2015) found reduced CCN4 expression in liver tumors compared with normal liver tissue, suggesting that CCN4 serves as a tumor suppressor. CCN4 expression is regulated by various signaling pathways and is sensitive to different biochemical perturbations in the TME, which may explain its diverse roles in cancer progression. Table 1 provides a summary of CCN4 expression and its functional roles in different types of cancer.

Expression and Roles of CCN5 in Pan-Cancer

CCN5 mRNA levels also vary across different types of cancer. Comparison of CCN5 mRNA levels across different cancer types and adjacent normal tissue revealed significantly lower expression of CCN5 in 16 types of cancer (BLCA, BRCA, CESC, COAD, ESCA, LUAD, LUSC, OV, PRAD, READ, SKCM, SATD, TGCT, THCA, UCEC, and UCS). Increased expression of CCN5 was not observed in any type of cancer. High CCN5 expression was associated with shorter OS in four types of cancer (COAD, KIRC, KIRP, and STAD) and longer OS only in SARC, suggesting that CCN5 acts as an anti-oncogene. The results of these bioinformatics analyses suggest that CCN5 expression and function vary across different types of cancer, perhaps due to differences in its structure compared with other CCN family members (Figure 3E).

As CCN5 lacks a CT domain, this striking difference in structure compared with other CCN family members may allow it to have unique functional roles. Like its family members, however, previous studies reported inconsistent roles of CCN5 in carcinogenesis. CCN5 is downregulated in human leiomyoma (Mason et al., 2004), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (Dhar et al., 2007), salivary gland cancer (Dhar et al., 2007), colorectal tumors (Pennica et al., 1998; Davies et al., 2010), and gallbladder cancer (Yang et al., 2014), suggesting that it acts as a tumor suppressor. Chai et al. (2019) showed that CCN5 overexpression inhibits cell growth, induces apoptosis, and suppresses cell migration and invasion in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Banerjee et al. (2008) showed that the expression of CCN5 is undetectable in normal breast tissues but increased in non-invasive breast cancer lesions, suggesting that it acts as a negative regulator of migration and invasion. By contrast, in glioma (Minchenko et al., 2015), liver cancer (Chen Z. et al., 2016), and pancreatic cancer (Wang et al., 2013), CCN5 acts as a tumor promoter. Whereas CCN5 mainly localizes in the nucleus in human cancer tissue (Wiesman et al., 2010), we found that CCN5 is expressed in both the cytoplasm and nucleus in malignant kidney tumors, with predominate cytoplasmic expression (unpublished data). Table 1 summarizes the expression and diverse roles of CCN5 across different types of cancer.

Expression and Roles of CCN6 in Pan-Cancer

CCN6 mRNA levels and prognostic value also vary depending on the type of cancer. Comparison of CCN6 mRNA levels among diverse cancer types and adjacent normal tissue revealed that CCN6 expression was significantly downregulated in four types of cancer (KICH, KIRC, SKCM, and TGCT) and significantly upregulated only in OV. When evaluating the association between CCN6 expression and prognosis, we found that high CCN6 expression was associated with shorter OS only in LIHC. These bioinformatics analyses further suggest that the expression and functions of CCN6 are inconsistent across cancer types (Figure 3F).

CCN6 has received much attention in the last few years due to its involvement in many cancer-related processes, including EMT, cell death, invasion, and metastasis, and its function as a tumor suppressor (Tran and Kleer, 2018). However, many studies reported that CCN6 can serve as both a tumor suppressor and promoter (Lee et al., 2016). CCN6 is expressed in normal breast epithelium but is reduced or lost in 60% of invasive breast carcinomas (Huang et al., 2008). CCN6 limits breast cancer invasion and metastasis by modulating the BMP signaling pathway (Pal et al., 2012). By contrast, CCN6 is overexpressed in 63% of human colon tumors and appears to be associated with colon tumorigenesis (Pennica et al., 1998). In addition, CCN6 is related to microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer (Thorstensen et al., 2001). As summarized in Table 1, the studies showed expression and functional roles of CCN6 are also inconsistent among different types of cancer.

Conclusion and Perspectives

The six members of CCN proteins have established associations with cancer malignancy progression and are considered as prognostic markers and therapeutic targets for several types of cancer. However, CCN proteins always appear to have contradictory roles in different types of cancer. After a retrospective analysis of the literature, we come to the conclusions (Arbyn et al., 2020). Cellular locations, tissue specificity of CCN proteins expression and the diverse TME provide some explanation for their apparently conflicting functions (Winkler et al., 2020). The presence of multiple functional domains of CCN proteins and the altered biological activity of truncated CCN proteins increasing the diversity of CCNs biological roles in cancer (Jiang et al., 2019). CCN protein functions could be orchestrated by other CCN members, and the final biological properties of a specific CCN protein might be dependent on the combinations of CCN members.

Targeting CCN protein expression or signaling pathways holds promise in the development of diagnostics and therapeutics for cancers, and the cocktail containing CCN proteins in different combinations should be a potential antitumor approach. Since the current literature has certain limitations in clarifying the exact role of CCN proteins, continued studies are still needed to reveal the exact roles of CCN proteins in cancer.

Author Contributions

QJ contributed to the conceptualization, literature search, writing, review, and editing. BX contributed to the literature search and editing. YZ contributed to the methodology and visualization. AA contributed to language proofreading. XL contributed to the critical review and editing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- Cancer types: ACC

adrenocortical carcinoma

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- BLCA

bladder urothelial carcinoma

- BRCA

breast invasive carcinoma

- CESC

cervical and endocervical cancers

- CHOL

cholangiocarcinoma

- COAD

colon adenocarcinoma

- DLBC

lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- ESCA

esophageal carcinoma

- GBM

Glioblastoma multiforme

- HNSC

head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- KICH

kidney chromophobe

- KIRC

kidney renal clear cell carcinoma

- KIRP

Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma

- AML

Acute Myeloid Leukemia

- LGG

brain lower grade glioma

- LIHC

liver hepatocellular carcinoma

- LUAD

lung adenocarcinoma

- MESO

mesothelioma

- OV

ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma

- PAAD

pancreatic adenocarcinoma

- PCPG

pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma

- PRAD

prostate adenocarcinoma

- SARC

sarcoma

- SKCM

skin cutaneous melanoma

- STAD

stomach adenocarcinoma

- TGCT

testicular germ cell tumors

- THCA

thyroid carcinoma

- THYM

thymoma

- UCEC

uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma

- UVM

uveal melanoma

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- CCN

cellular communication network

- CCN1/CYR61

cysteine-rich 61

- CCN2/CTGF

connective tissue growth factor

- CCN3/NOV

nephroblastoma overexpressed

- CCN4/WISP-1

Wnt1-inducible signaling pathway proteins 1

- CCN4/WISP-2

Wnt1-inducible signaling pathway proteins 2

- CCN4/WISP-3

Wnt1-inducible signaling pathway proteins 3

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- IGFBP

insulin-like growth factor-binding protein

- VWC

Von Willebrand factor type C

- BMPs

bone morphogenic proteins

- TSP-1

The thrombospondin type 1 repeat

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- HSPGs

heparan sulfate proteoglycans

- CT

carboxyterminal

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

Footnotes

Funding. This research project was mainly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81502694) and partially supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (1191329835).

References

- Abreu J. G., Ketpura N. I., Reversade B., De Robertis E. M. (2002). Connective-tissue growth factor (CTGF) modulates cell signalling by BMP and TGF-beta. Nat. Cell Biol. 4 599–604. 10.1038/ncb826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alday-Parejo B., Stupp R., Ruegg C. (2019). Are integrins still practicable targets for anti-cancer therapy? Cancers (Basel) 11:978. 10.3390/cancers11070978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbyn M., Weiderpass E., Bruni L., de Sanjose S., Saraiya M., Ferlay J., et al. (2020). Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 8 e191–e203. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30482-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Dhar G., Haque I., Kambhampati S., Mehta S., Sengupta K., et al. (2008). CCN5/WISP-2 expression in breast adenocarcinoma is associated with less frequent progression of the disease and suppresses the invasive phenotypes of tumor cells. Cancer Res. 68 7606–7612. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Saxena N., Sengupta K., Tawfik O., Mayo M. S., Banerjee S. K. (2003). WISP-2 gene in human breast cancer: estrogen and progesterone inducible expression and regulation of tumor cell proliferation. Neoplasia 5 63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbolina M. V., Adley B. P., Kelly D. L., Shepard J., Fought A. J., Scholtens D., et al. (2009). Downregulation of connective tissue growth factor by three-dimensional matrix enhances ovarian carcinoma cell invasion. Int. J. Cancer 125 816–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto S. C., Ray A., Ag Edgar P. (2016). Biological characteristics of CCN proteins in tumor development. J. BUON 21 1359–1367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennewith K. L., Huang X., Ham C. M., Graves E. E., Erler J. T., Kambham N., et al. (2009). The role of tumor cell-derived connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) in pancreatic tumor growth. Cancer Res. 69 775–784. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-098769/3/775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleau A. M., Planque N., Lazar N., Zambelli D., Ori A., Quan T., et al. (2007). Antiproliferative activity of CCN3: involvement of the C-terminal module and post-translational regulation. J. Cell Biochem. 101 1475–1491. 10.1002/jcb.21262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigstock D. R. (2003). The CCN family: a new stimulus package. J. Endocrinol. 178 169–175. 10.1677/joe.0.1780169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canalis E. (2007). Nephroblastoma overexpressed (Nov) is a novel bone morphogenetic protein antagonist. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1116 50–58. 10.1196/annals.1402.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai D.-M., Qin Y.-Z., Wu S.-W., Ma L., Tan Y.-Y., Yong X., et al. (2019). WISP2 exhibits its potential antitumor activity via targeting ERK and E-cadherin pathways in esophageal cancer cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 38:102. 10.1186/s13046-019-1108-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A.-C., Lien M.-Y., Tsai M.-H., Hua C.-H., Tang C.-H. (2019). WISP-1 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells via the miR-153-3p/Snail Axis. Cancers (Basel) 11:1903. 10.3390/cancers11121903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. C., Shih J. Y., Jeng Y. M., Su J. L., Lin B. Z., Chen S. T., et al. (2004). Connective tissue growth factor and its role in lung adenocarcinoma invasion and metastasis. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 96 364–375. 10.1093/jnci/djh059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. C., Yang M. H., Lin B. R., Chen S. T., Pan S. H., Hsiao M., et al. (2013). CCN2 inhibits lung cancer metastasis through promoting DAPK-dependent anoikis and inducing EGFR degradation. Cell Death Differ. 20 443–455. 10.1038/cdd.2012.136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. N., Chang C. C., Lai H. S., Jeng Y. M., Chen C. I., Chang K. J., et al. (2015). Connective tissue growth factor inhibits gastric cancer peritoneal metastasis by blocking integrin α3β1-dependent adhesion. Gastric cancer 18 504–515. 10.1007/s10120-014-0400-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. T., Lee H. L., Chiou H. L., Chou C. H., Wang P. H., Yang S. F., et al. (2018). Impacts of WNT1-inducible signaling pathway protein 1 polymorphism on hepatocellular carcinoma development. PLoS one 13:e0198967. 10.1371/journal.pone.0198967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Liu Y., Sun Q., Wang B., Li N., Chen X. (2016). CYR61 suppresses growth of human malignant melanoma. Oncol. Rep. 36 2697–2704. 10.3892/or.2016.5124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P. C., Cheng H. C., Wang J., Wang S. W., Tai H. C., Lin C. W., et al. (2014). Prostate cancer-derived CCN3 induces M2 macrophage infiltration and contributes to angiogenesis in prostate cancer microenvironment. Oncotarget 5 1595–1608. 10.18632/oncotarget.1570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P. C., Tai H. C., Lin T. H., Wang S. W., Lin C. Y., Chao C. C., et al. (2017). CCN3 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in prostate cancer via FAK/Akt/HIF-1alpha-induced twist expression. Oncotarget 8 74506–74518. 10.18632/oncotarget.20171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P. P., Li W. J., Wang Y., Zhao S., Li D. Y., Feng L. Y., et al. (2007). Expression of Cyr61, CTGF, and WISP-1 correlates with clinical features of lung cancer. PLoS One 2:e534. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Tang J., Cai X., Huang Y., Gao Q., Liang L., et al. (2016). HBx mutations promote hepatoma cell migration through the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Cancer Sci 107 1380–1389. 10.1111/cas.13014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T. Y., Wu M. S., Hua K. T., Kuo M. L., Lin M. T. (2014). Cyr61/CTGF/Nov family proteins in gastric carcinogenesis. World J. Gastroenterol. 20 1694–1700. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i7.1694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang K.-C., Yeh C.-N., Chung L.-C., Feng T.-H., Sun C.-C., Chen M.-F., et al. (2015). WNT-1 inducible signaling pathway protein-1 enhances growth and tumorigenesis in human breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 5:8686. 10.1038/srep08686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien W., Kumagai T., Miller C. W., Desmond J. C., Frank J. M., Said J. W., et al. (2004). Cyr61 suppresses growth of human endometrial cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279 53087–53096. 10.1074/jbc.M410254200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang J. Y., Yang W. Y., Lai C. H., Lin C. D., Tsai M. H., Tang C. H. (2011). CTGF inhibits cell motility and COX-2 expression in oral cancer cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 11 948–954. 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crijns H., Vanheule V., Proost P. (2020). Targeting chemokine-glycosaminoglycan interactions to inhibit inflammation. Front. Immunol. 11:483. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L., Xie R., Dang S., Zhang Q., Mao S., Chen J., et al. (2014). NOV promoted the growth and migration of pancreatic cancer cells. Tumour. Biol. 35 3195–3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang T., Modak C., Meng X., Wu J., Narvaez R., Chai J. (2017). CCN1 sensitizes esophageal cancer cells to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. Exp. Cell Res. 361 163–169. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang T., Modak C., Meng X., Wu J., Narvaez R., Chai J. (2018). CCN1 induces apoptosis in esophageal adenocarcinoma through p53-dependent downregulation of survivin. J. Cell Biochem. 120 2070–2077. 10.1002/jcb.27515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Antonio K. B., Schultz L., Albadine R., Mondul A. M., Platz E. A., Netto G. J., et al. (2010). Decreased expression of Cyr61 is associated with prostate cancer recurrence after surgical treatment. Clin. Cancer Res. 16 5908–5913. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S. R., Davies M. L., Sanders A., Parr C., Torkington J., Jiang W. G. (2010). Differential expression of the CCN family member WISP-1, WISP-2 and WISP-3 in human colorectal cancer and the prognostic implications. Int. J. Oncol. 36 1129–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S. R., Watkins G., Mansel R. E., Jiang W. G. (2007). Differential expression and prognostic implications of the CCN family members WISP-1, WISP-2, and WISP-3 in human breast cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 14 1909–1918. 10.1245/s10434-007-9376-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W., Fernandez A., McLaughlin S. L., Klinke D. J., II (2019). WNT1-inducible signaling pathway protein 1 (WISP1/CCN4) stimulates melanoma invasion and metastasis by promoting the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Biol. Chem. 294 5261–5280. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.006122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y. Z., Chen P. P., Wang Y., Yin D., Koeffler H. P., Li B., et al. (2007). Connective tissue growth factor is overexpressed in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and promotes tumorigenicity through beta-catenin-T-cell factor/Lef signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 282 36571–36581. 10.1074/jbc.M704141200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar G., Mehta S., Banerjee S., Gardner A., McCarty B. M., Mathur S. C., et al. (2007). Loss of WISP-2/CCN5 signaling in human pancreatic cancer: a potential mechanism for epithelial-mesenchymal-transition. Cancer Lett. 254 63–70. 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson J. R., Taipaleenmaki H., Hu Y. J., Hong D., van Wijnen A. J., Stein J. L., et al. (2014). hsa-mir-30c promotes the invasive phenotype of metastatic breast cancer cells by targeting NOV/CCN3. Cancer Cell Int. 14:73. 10.1186/s12935-014-0073-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang F., Zhao W.-Y., Li R.-K., Yang X.-M., Li J., Ao J.-P., et al. (2014). Silencing of WISP3 suppresses gastric cancer cell proliferation and metastasis and inhibits Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 7 6447–6461. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng P., Wang B., Ren E. C. (2008). Cyr61/CCN1 is a tumor suppressor in human hepatocellular carcinoma and involved in DNA damage response. Int. J Biochem Cell Biol 40 98–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H., Salahshor S., Stenling R., Björk J., Lindmark G., Iselius L., et al. (2001). COL11A1 in FAP polyps and in sporadic colorectal tumors. BMC Cancer 1:17. 10.1186/1471-2407-1-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong Y.-C., Lin C.-Y., Su Y.-C., Chen W.-C., Tsai F.-J., Tsai C.-H., et al. (2012). CCN6 enhances ICAM-1 expression and cell motility in human chondrosarcoma cells. J. Cell Physiol. 227 223–232. 10.1002/jcp.22720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Yin F.-F., Guan D.-X., Feng Y.-X., Zheng Q.-W., Wang X., et al. (2019). Liver cancer: WISP3 suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma progression by negative regulation of β-catenin/TCF/LEF signalling. Cell Prolif. 52:e12583. 10.1111/cpr.12583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen K. G., Bovenschen N., Nguyen T. Q., Sprengers D., Koeners M. P., van Koppen A. N., et al. (2016). Rapid hepatic clearance of full length CCN-2/CTGF: a putative role for LRP1-mediated endocytosis. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 10 295–303. 10.1007/s12079-016-0354-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gery S., Xie D., Yin D., Gabra H., Miller C., Wang H., et al. (2005). Ovarian carcinomas: CCN genes are aberrantly expressed and CCN1 promotes proliferation of these cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 11 7243–7254. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-05-0231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graumann J., Finkernagel F., Reinartz S., Stief T., Brödje D., Renz H., et al. (2019). Multi-platform affinity proteomics identify proteins linked to metastasis and immune suppression in ovarian cancer plasma. Front. Oncol. 9:1150. 10.3389/fonc.2019.01150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N., Wang H., McLeod T. L., Naus C. C., Kyurkchiev S., Advani S., et al. (2001). Inhibition of glioma cell growth and tumorigenic potential by CCN3 (NOV). Mol. Pathol. 54 293–299. 10.1136/mp.54.5.293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque I., Banerjee S., De A., Maity G., Sarkar S., Majumdar M., et al. (2015). CCN5/WISP-2 promotes growth arrest of triple-negative breast cancer cells through accumulation and trafficking of p27(Kip1) via Skp2 and FOXO3a regulation. Oncogene 34 3152–3163. 10.1038/onc.2014.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque I., Mehta S., Majumder M., Dhar K., De A., McGregor D., et al. (2011). Cyr61/CCN1 signaling is critical for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stemness and promotes pancreatic carcinogenesis. Mol. Cancer 10:8. 10.1186/1476-4598-10-81476-4598-10-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbourn K. P., Perbal B., Ravi Acharya K. (2009). Proteins on the catwalk: modelling the structural domains of the CCN family of proteins. J. Cell. Commun. Signal. 3 25–41. 10.1007/s12079-009-0048-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou C. H., Chiang Y. C., Fong Y. C., Tang C. H. (2011). WISP-1 increases MMP-2 expression and cell motility in human chondrosarcoma cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 81 1286–1295. Epub 2011/04/02. 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Zhang Y., Varambally S., Chinnaiyan A. M., Banerjee M., Merajver S. D., et al. (2008). Inhibition of CCN6 (Wnt-1-induced signaling protein 3) down-regulates E-cadherin in the breast epithelium through induction of snail and ZEB1. Am. J. Pathol. 172 893–904. 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilhan M., Kucukkose C., Efe E., Gunyuz Z. E., Firatligil B., Dogan H., et al. (2020). Pro-metastatic functions of Notch signaling is mediated by CYR61 in breast cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 99:151070. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2020.151070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inkson C. A., Ono M., Kuznetsov S. A., Fisher L. W., Robey P. G., Young M. F. (2008). TGF-beta1 and WISP-1/CCN-4 can regulate each other’s activity to cooperatively control osteoblast function. J. Cell Biochem. 104 1865–1878. 10.1002/jcb.21754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isbert C., Ritz J. P., Roggan A., Schuppan D., Ajubi N., Buhr H. J., et al. (2007). Laser-induced thermotherapy (LITT) elevates mRNA expression of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) associated with reduced tumor growth of liver metastases compared to hepatic resection. Lasers Surg. Med. 39 42–50. 10.1002/lsm.20448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar A. R., Apeksha A., Norenberg M. D. (2017). Role of matricellular proteins in disorders of the central nervous system. Neurochem. Res. 42 858–875. 10.1007/s11064-016-2088-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong D., Heo S., Sung Ahn T., Lee S., Park S., Kim H., et al. (2014). Cyr61 expression is associated with prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. BMC cancer 14:164. 10.1186/1471-2407-14-164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J., Jia S., Jia Y., Ji K., Hargest R., Jiang W. G. (2015). WISP-2 in human gastric cancer and its potential metastatic suppressor role in gastric cancer cells mediated by JNK and PLC-γ pathways. Br. J. Cancer 113 921–933. 10.1038/bjc.2015.285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H., Janjanam J., Wu S. C., Wang R., Pano G., Celestine M., et al. (2019). The tumor cell-secreted matricellular protein WISP1 drives pro-metastatic collagen linearization. EMBO J. 38:e101302. 10.15252/embj.2018101302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Q., Bu Y., Wang Z., Chen B., Zhang Q., Yu S., et al. (2017a). Maintenance of stemness is associated with the interation of LRP6 and heparin-binding protein CCN2 autocrined by hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 36:117. 10.1186/s13046-017-0576-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Q., Dong Q., Qin L. (2016). CCN: core regulatory proteins in the microenvironment that affect the metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma? Oncotarget 7 1203–1214. 10.18632/oncotarget.6209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Q., Xue T., Zhang Q., Cheng W., Zhang C., Ma J., et al. (2017). CCN3 is a therapeutic target relating enhanced stemness and coagulation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 7:13846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia S., Qu T., Feng M., Ji K., Li Z., Jiang W., et al. (2017). Association of Wnt1-inducible signaling pathway protein-1 with the proliferation, migration and invasion in gastric cancer cells. Tumour. Biol. 39 10.1177/1010428317699755 ∗∗∗Q, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C. G., Lv L., Liu F. R., Wang Z. N., Liu F. N., Li Y. S., et al. (2011). Downregulation of connective tissue growth factor inhibits the growth and invasion of gastric cancer cells and attenuates peritoneal dissemination. Mol. Cancer 10:122. 10.1186/1476-4598-10-122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Sun A., Zhao Y., Ying W., Sun H., Yang X., et al. (2019). Proteomics identifies new therapeutic targets of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature 567 257–261. 10.1038/s41586-019-0987-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joliot V., Martinerie C., Dambrine G., Plassiart G., Brisac M., Crochet J., et al. (1992). Proviral rearrangements and overexpression of a new cellular gene (nov) in myeloblastosis-associated virus type 1-induced nephroblastomas. Mol. Cell Biol. 12 10–21. 10.1128/mcb.12.1.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun J. I., Lau L. F. (2011). Taking aim at the extracellular matrix: CCN proteins as emerging therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10 945–963. 10.1038/nrd3599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung E. K., Kim S.-A., Yoon T. M., Lee K.-H., Kim H. K., Lee D. H., et al. (2017). WNT1-inducible signaling pathway protein-1 contributes to tumor progression and treatment failure in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 14 1719–1724. 10.3892/ol.2017.6313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaasboll O. J., Gadicherla A. K., Wang J. H., Monsen V. T., Hagelin E. M. V., Dong M. Q., et al. (2018). Connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) is a matricellular preproprotein controlled by proteolytic activation. J. Biol. Chem. 293 17953–17970. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi F., O’Connor A. J., Qiao G. G., Heath D. E. (2018). Integrin clustering matters: a review of biomaterials functionalized with multivalent integrin-binding ligands to improve cell adhesion, migration, differentiation, angiogenesis, and biomedical device integration. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 7:e1701324. 10.1002/adhm.201701324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S., Roberts D. D. (2021). Differential intolerance to loss of function and missense mutations in genes that encode human matricellular proteins. J. Cell Commun. Signal 15 93–105. 10.1007/s12079-020-00598-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandelwal M., Anand V., Appunni S., Seth A., Singh P., Mathur S., et al. (2020). RASSF1A-Hippo pathway link in patients with urothelial carcinoma of bladder: plausible therapeutic target. Mol. Cell Biochem. 464 51–63. 10.1007/s11010-019-03648-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd M., Modlin I. M., Eick G. N., Camp R. L., Mane S. M. (2007). Role of CCN2/CTGF in the proliferation of Mastomys enterochromaffin-like cells and gastric carcinoid development. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 292 G191–G200. 10.1152/ajpgi.00131.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleer C. G. (2016). Dual roles of CCN proteins in breast cancer progression. J. Cell Commun. Signal 10 217–222. 10.1007/s12079-016-0345-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleer C. G., Zhang Y., Pan Q., Merajver S. D. (2004). WISP3 (CCN6) is a secreted tumor-suppressor protein that modulates IGF signaling in inflammatory breast cancer. Neoplasia 6 179–185. 10.1593/neo.03316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok S.-H., Chang H.-H., Tsai J.-Y., Hung H.-C., Lin C.-Y., Chiang C.-P., et al. (2010). Expression of Cyr61 (CCN1) in human oral squamous cell carcinoma: an independent marker for poor prognosis. Head Neck 32 1665–1673. 10.1002/hed.21381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzu Y., Uzawa K., Kato M., Higo M., Nimura Y., Harada K., et al. (2006). WISP-2 expression in human salivary gland tumors. Int. J. Mol. Med. 17 567–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C.-F., Lin S.-L., Chiang W.-C., Chen Y.-M., Wu V.-C., Young G.-H., et al. (2014). Blockade of cysteine-rich protein 61 attenuates renal inflammation and fibrosis after ischemic kidney injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 307 F581–F592. 10.1152/ajprenal.00670.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent M., Martinerie C., Thibout H., Hoffman M. P., Verrecchia F., Le Bouc Y., et al. (2003). NOVH increases MMP3 expression and cell migration in glioblastoma cells via a PDGFR-alpha-dependent mechanism. FASEB J. 17 1919–1921. 10.1096/fj.02-1023fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A. (2020). Conjunction junction, what’s the function? CCN proteins as targets in fibrosis and cancers. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 318 C1046–C1054. 10.1152/ajpcell.00028.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.-L., Chiou H.-L., Wang S.-S., Hung S.-C., Chou M.-C., Yang S.-F., et al. (2018). WISP1 genetic variants as predictors of tumor development with urothelial cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol 36 .e15–.e160. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.11.023 160.e15-160.e21, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Choi Y. J., Je E. M., Kim H. S., Yoo N. J., Lee S. H. (2016). Frameshift mutation of WISP3 gene and its regional heterogeneity in gastric and colorectal cancers. Hum. Pathol. 50 146–152. 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leguit R. J., Raymakers R. A. P., Hebeda K. M., Goldschmeding R. (2021). CCN2 (Cellular Communication Network factor 2) in the bone marrow microenvironment, normal and malignant hematopoiesis. J. Cell Commun. Signal 15 25–56. 10.1007/s12079-020-00602-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lencioni R., de Baere T., Soulen M. C., Rilling W. S., Geschwind J. F. (2016). Lipiodol transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of efficacy and safety data. Hepatology 64 106–116. 10.1002/hep.28453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Gao X., Ji K., Sanders A. J., Zhang Z., Jiang W. G., et al. (2016). Differential expression of CCN family members CYR611, CTGF and NOV in gastric cancer and their association with disease progression. Oncol. Rep. 36 2517–2525. 10.3892/or.2016.5074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Ye L., Owen S., Weeks H. P., Zhang Z., Jiang W. G. (2015). Emerging role of CCN family proteins in tumorigenesis and cancer metastasis (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 36 1451–1463. 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Ye L., Sun P. H., Zheng F., Ruge F., Satherley L. K., et al. (2017). Reduced NOV expression correlates with disease progression in colorectal cancer and is associated with survival, invasion and chemoresistance of cancer cells. Oncotarget 8 26231–26244. 10.18632/oncotarget.15439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. Q., Wu W. R., Zhao C., Zhao C., Zhang X. L., Yang Z., et al. (2018). CCN1/Cyr61 enhances the function of hepatic stellate cells in promoting the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Med. 41 1518–1528. 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Liu Z., Bi D., Yuan X., Liu X., Ding S., et al. (2012). CCN3 (NOV) regulates proliferation, adhesion, migration and invasion in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 3 1099–1104. 10.3892/ol.2012.607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Zhou Y. D., Xiao Y. L., Li M. H., Wang Y., Kan X., et al. (2015). Cyr61/CCN1 overexpression induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition leading to laryngeal tumor invasion and metastasis and poor prognosis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 16 2659–2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Wang X., Sun X., Feng W., Guo H., Tang C., et al. (2016). WISP3 is highly expressed in a subset of colorectal carcinomas with a better prognosis. Onco. Targets Ther. 9 287–293. 10.2147/OTT.S97025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maity G., Mehta S., Haque I., Dhar K., Sarkar S., Banerjee S. K., et al. (2014). Pancreatic tumor cell secreted CCN1/Cyr61 promotes endothelial cell migration and aberrant neovascularization. Sci. Rep. 4:4995. 10.1038/srep04995srep04995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino Y., Hikita H., Kodama T., Shigekawa M., Yamada R., Sakamori R., et al. (2018). CTGF mediates tumor-stroma interactions between hepatoma cells and hepatic stellate cells to accelerate HCC progression. Cancer Res. 78 4902–4914. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-17-3844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Z., Ma X., Rong Y., Cui L., Wang X., Wu W., et al. (2011). Connective tissue growth factor enhances the migration of gastric cancer through downregulation of E-cadherin via the NF-κB pathway. Cancer Sci. 102 104–110. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01746.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin E. E., Huang W., Anwar T., Arellano-Garcia C., Burman B., Guan J. L., et al. (2017). MMTV-cre;Ccn6 knockout mice develop tumors recapitulating human metaplastic breast carcinomas. Oncogene 36 2275–2285. 10.1038/onc.2016.381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason H. R., Lake A. C., Wubben J. E., Nowak R. A., Castellot J. J., Jr. (2004). The growth arrest-specific gene CCN5 is deficient in human leiomyomas and inhibits the proliferation and motility of cultured human uterine smooth muscle cells. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 10 181–187. 10.1093/molehr/gah028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara D., Niki T., Ishikawa S., Goto A., Ohara E., Yokomizo T., et al. (2005). Differential expression of S100A2 and S100A4 in lung adenocarcinomas: clinicopathological significance, relationship to p53 and identification of their target genes. Cancer Sci. 96 844–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum L., Lu W., Price S., Lazar N., Perbal B., Irvine A. E. (2012). CCN3 suppresses mitogenic signalling and reinstates growth control mechanisms in Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia. J. Cell. Commun. Signal. 6 27–35. 10.1007/s12079-011-0142-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minamizato T., Sakamoto K., Liu T., Kokubo H., Katsube K., Perbal B., et al. (2007). CCN3/NOV inhibits BMP-2-induced osteoblast differentiation by interacting with BMP and Notch signaling pathways. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 354 567–573. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minchenko D. O., Kharkova A. P., Tsymbal D. O., Karbovskyi L. L., Minchenko O. H. (2015). IRE1 inhibition affects the expression of insulin-like growth factor binding protein genes and modifies its sensitivity to glucose deprivation in U87 glioma cells. Endocr. Regul. 49 185–197. 10.4149/endo_2015_04_185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori A., Desmond J. C., Komatsu N., O’Kelly J., Miller C. W., Legaspi R., et al. (2007). CYR61: a new measure of lung cancer outcome. Cancer Invest. 25 738–741. 10.1080/02770900701512597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai Y., Watanabe M., Ishikawa S., Karashima R., Kurashige J., Iwagami S., et al. (2011). Clinical significance of Wnt-induced secreted protein-1 (WISP-1/CCN4) in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 31 991–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer E. F., Poole A. Z., Neubauer P., Detournay O., Tan K., Davy S. K., et al. (2017). A diverse host thrombospondin-type-1 repeat protein repertoire promotes symbiont colonization during establishment of cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis. Elife 6:e24494. 10.7554/eLife.24494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu C. C., Zhao C., Yang Z., Zhang X. L., Pan J., Zhao C., et al. (2014). Inhibiting CCN1 blocks AML cell growth by disrupting the MEK/ERK pathway. Cancer Cell Int. 14:74. 10.1186/s12935-014-0074-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M., Inkson C. A., Sonn R., Kilts T. M., de Castro L. F., Maeda A., et al. (2013). WISP1/CCN4: a potential target for inhibiting prostate cancer growth and spread to bone. PLoS One 8:e71709. 10.1371/journal.pone.0071709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal A., Huang W., Li X., Toy K. A., Nikolovska-Coleska Z., Kleer C. G. (2012). CCN6 modulates BMP signaling via the Smad-independent TAK1/p38 pathway, acting to suppress metastasis of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 72 4818–4828. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer A. C., Sorger P. K. (2017). Combination cancer therapy can confer benefit via patient-to-patient variability without drug additivity or synergy. Cell 171 1678–1691.e13. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.009 1678-91 e13, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peidl A., Perbal B., Leask A. (2019). Yin/Yang expression of CCN family members: Transforming growth factor beta 1, via ALK5/FAK/MEK, induces CCN1 and CCN2, yet suppresses CCN3, expression in human dermal fibroblasts. PLoS One 14:e0218178. 10.1371/journal.pone.0218178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennica D., Swanson T. A., Welsh J. W., Roy M. A., Lawrence D. A., Lee J., et al. (1998). WISP genes are members of the connective tissue growth factor family that are up-regulated in wnt-1-transformed cells and aberrantly expressed in human colon tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 14717–14722. 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal A., Perbal B. (2016). The CCN family of proteins: a 25th anniversary picture. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 10 177–190. 10.1007/s12079-016-0340-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B. (2004). CCN proteins: multifunctional signalling regulators. Lancet 363 62–64. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15172-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B. (2006a). New insight into CCN3 interactions–nuclear CCN3 : fact or fantasy? Cell Commun. Signal 4 6. 10.1186/1478-811X-4-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B. (2006b). NOV story: the way to CCN3. Cell Commun. Signal 4 3. 10.1186/1478-811X-4-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B. (2009). Alternative splicing of CCN mRNAs. it has been upon us. J. Cell Commun. Signal 3 153–157. 10.1007/s12079-009-0051-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B. (2016). A special issue on CCN proteins and cancer. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 10 171–172. 10.1007/s12079-016-0344-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B. (2018). The concept of the CCN protein family revisited: a centralized coordination network. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 12 3–12. 10.1007/s12079-018-0455-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B. (2019). CCN proteins are part of a multilayer complex system: a working model. J. Cell Commun. Signal 13 437–439. 10.1007/s12079-019-00543-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planque N., Long Li C, Saule S., Bleau A. M., Perbal B. (2006). Nuclear addressing provides a clue for the transforming activity of amino-truncated CCN3 proteins. J. Cell Biochem. 99 105–116. 10.1002/jcb.20887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramazani Y., Knops N., Elmonem M. A., Nguyen T. Q., Arcolino F. O., van den Heuvel L., et al. (2018). Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) from basics to clinics. Matrix Biol. 6 44–66. 10.1016/j.matbio.2018.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repudi S. R., Patra M., Sen M. (2013). WISP3-IGF1 interaction regulates chondrocyte hypertrophy. J. Cell Sci. 126(Pt 7) 1650–1658. 10.1242/jcs.119859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S., Ghosh A., Banerjee S., Maity G., Das A., Larson M. A., et al. (2017). CCN5/WISP-2 restores ER- proportional, variant in normal and neoplastic breast cells and sensitizes triple negative breast cancer cells to tamoxifen. Oncogenesis 6:e340. 10.1038/oncsis.2017.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimo T., Kubota S., Yoshioka N., Ibaragi S., Isowa S., Eguchi T., et al. (2006). Pathogenic role of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) in osteolytic metastasis of breast cancer. J. Bone Miner. Res 21 1045–1059. 10.1359/jbmr.060416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soon L. L., Yie T. A., Shvarts A., Levine A. J., Su F., Tchou-Wong K. M. (2003). Overexpression of WISP-1 down-regulated motility and invasion of lung cancer cells through inhibition of Rac activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278 11465–11470. 10.1074/jbc.M210945200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su R. L., Qiao Y., Guo R. F., Lv Y. Y. (2019). Cyr61 overexpression induced by interleukin 8 via NF-kB signaling pathway and its role in tumorigenesis of gastric carcinoma in vitro. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 12 3197–3207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam M. M., Lazar N., Navarro S., Perbal B., Llombart-Bosch A. (2008). Expression of CCN3 protein in human Wilms’ tumors: immunohistochemical detection of CCN3 variants using domain-specific antibodies. Virchows Arch. 452 33–39. 10.1007/s00428-007-0523-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z. J., Wang Y., Cai Z., Chen P. P., Tong X. J., Xie D. (2008). Involvement of Cyr61 in growth, migration, and metastasis of prostate cancer cells. Br. J. Cancer 99 1656–1667. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghavi A., Akbari M. E., Hashemi-Bahremani M., Nafissi N., Khalilnezhad A., Poorhosseini S. M., et al. (2016). Gene expression profiling of the 8q22-24 position in human breast cancer:,, and genes are implicated in oncogenesis, while and genes may predict a risk of metastasis. Oncol. Lett. 12 3845– 3855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai H.-C., Chang A.-C., Yu H.-J., Huang C.-Y., Tsai Y.-C., Lai Y.-W., et al. (2014). Osteoblast-derived WNT-induced secreted protein 1 increases VCAM-1 expression and enhances prostate cancer metastasis by down-regulating miR-126. Oncotarget 5 7589–7598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan T. W., Yang W. H., Lin Y. T., Hsu S. F., Li T. M., Kao S. T., et al. (2009). Cyr61 increases migration and MMP-13 expression via alphavbeta3 integrin, FAK, ERK and AP-1-dependent pathway in human chondrosarcoma cells. Carcinogenesis 30 258–268. 10.1093/carcin/bgn284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z., Kang B., Li C., Chen T., Zhang Z. (2019). GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 W556–W560. 10.1093/nar/gkz430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao W., Chu C., Zhou W., Huang Z., Zhai K., Fang X., et al. (2020). Dual Role of WISP1 in maintaining glioma stem cells and tumor-supportive macrophages in glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 11:3015. 10.1038/s41467-020-16827-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur R., Mishra D. P. (2016). Matrix reloaded: CCN, tenascin and SIBLING group of matricellular proteins in orchestrating cancer hallmark capabilities. Pharmacol Therapeut 168 61–74. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorstensen L., Diep C. B., Meling G. I., Aagesen T. H., Ahrens C. H., Rognum T. O., et al. (2001). WNT1 inducible signaling pathway protein 3, WISP-3, a novel target gene in colorectal carcinomas with microsatellite instability. Gastroenterology 121 1275–1280. 10.1053/gast.2001.29570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong X., Xie D., O’Kelly J., Miller C. W., Muller-Tidow C., Koeffler H. P. (2001). Cyr61, a member of CCN family, is a tumor suppressor in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 276 47709–47714. 10.1074/jbc.M107878200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran M. N., Kleer C. G. (2018). Matricellular CCN6 (WISP3) protein: a tumor suppressor for mammary metaplastic carcinomas. J. Cell. Commun. Signal 12 13–19. 10.1007/s12079-018-0451-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H. C., Tzeng H. E., Huang C. Y., Huang Y. L., Tsai C. H., Wang S. W., et al. (2017). WISP-1 positively regulates angiogenesis by controlling VEGF-A expression in human osteosarcoma. Cell Death Dis. 8:e2750. 10.1038/cddis.2016.421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubink I., Verhaar E. R., Kranenburg O., Goldschmeding R. (2016). A potential role for CCN2/CTGF in aggressive colorectal cancer. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 10 223–227. 10.1007/s12079-016-0347-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viloria K., Hill N. J. (2016). Embracing the complexity of matricellular proteins: the functional and clinical significance of splice variation. Biomol. Concepts 7 117–132. 10.1515/bmc-2016-0004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Sun J., Cao H. (2019). MicroRNA-384 regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis through directly targeting WISP1 in laryngeal cancer. J. Cell. Biochem. 120 3018–3026. 10.1002/jcb.27323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Liu H., Liu T., Shu S., Jiang H., Cheng S., et al. (2013). BRCA2 dysfunction promotes malignant transformation of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 13 261–269. 10.2174/1871520611313020012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Xu T., Gao F., He H., Zhu Y., Shen Z. (2017). Targeting of CCN2 suppresses tumor progression and improves chemo-sensitivity in urothelial bladder cancer. Oncotarget 8 66316–66327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells J. E., Howlett M., Halse H. M., Heng J., Ford J., Cheung L. C., et al. (2016). High expression of connective tissue growth factor accelerates dissemination of leukaemia. Oncogene 35 4591–4600. 10.1038/onc.2015.525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesman K. C., Wei L., Baughman C., Russo J., Gray M. R., Castellot J. J. (2010). CCN5, a secreted protein, localizes to the nucleus. J. Cell Commun. Signal 4 91–98. 10.1007/s12079-010-0087-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler J., Abisoye-Ogunniyan A., Metcalf K. J., Werb Z. (2020). Concepts of extracellular matrix remodelling in tumour progression and metastasis. Nat. Commun. 11:5120. 10.1038/s41467-020-18794-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Long Z., Cai H., Du C., Liu X., Yu S., et al. (2016). High expression of WISP1 in colon cancer is associated with apoptosis, invasion and poor prognosis. Oncotarget 7 49834–49847. 10.18632/oncotarget.10486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. L., Li H. Y., Zhao X. P., Jiao J. Y., Tang D. X., Yan L. J., et al. (2017). Mesenchymal stem cell-derived CCN2 promotes the proliferation, migration and invasion of human tongue squamous cell carcinoma cells. Cancer Sci. 108 897–909. 10.1111/cas.13202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie D., Miller C. W., O’Kelly J., Nakachi K., Sakashita A., Said J. W., et al. (2001a). Breast cancer. Cyr61 is overexpressed, estrogen-inducible, and associated with more advanced disease. J. Biol. Chem. 276 14187–14194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie D., Nakachi K., Wang H., Elashoff R., Koeffler H. P. (2001b). Elevated levels of connective tissue growth factor, WISP-1, and CYR61 in primary breast cancers associated with more advanced features. Cancer Res. 61 8917–8923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie D., Yin D., Tong X., O’Kelly J., Mori A., Miller C., et al. (2004a). Cyr61 is overexpressed in gliomas and involved in integrin-linked kinase-mediated Akt and beta-catenin-TCF/Lef signaling pathways. Cancer Res. 64 1987–1996. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-0666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie D., Yin D., Wang H. J., Liu G. T., Elashoff R., Black K., et al. (2004b). Levels of expression of CYR61 and CTGF are prognostic for tumor progression and survival of individuals with gliomas. Clin Cancer Res 10 2072–2081. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0659-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J. J., Xu L. Y., Xie Y. M., Du Z. P., Feng C. H., Dong H., et al. (2011). Involvement of Cyr61 in the growth, invasiveness and adhesion of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 27 429–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L., Song X., Lin H., Chen Z., Li Q., Guo T., et al. (2019). Aberrant activation of CYR61 enhancers in colorectal cancer development. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 38:213. 10.1186/s13046-019-1217-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Corcoran R. B., Welsh J. W., Pennica D., Levine A. J. (2000). WISP-1 is a Wnt-1- and beta-catenin-responsive oncogene. Genes Dev. 14 585–595. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X., Baxter R. C., Perbal B., Firth S. M. (2006). The aminoterminal insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding domain of IGF binding protein-3 cannot be functionally substituted by the structurally homologous domain of CCN3. Endocrinology 147 5268–5274. 10.1210/en.2005-1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Tuxhorn J. A., Ressler S. J., McAlhany S. J., Dang T. D., Rowley D. R. (2005). Stromal expression of connective tissue growth factor promotes angiogenesis and prostate cancer tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 65 8887–8895. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-05-1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. Y., Yang M. W., Huo Y. M., Liu W., Liu D. J., Li J., et al. (2015). High expression of WISP-1 correlates with poor prognosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Transl. Res. 7 1621–1628. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Yang Z., Zou Q., Yuan Y., Li J., Li D., et al. (2014). A comparative study of clinicopathological significance, FGFBP1, and WISP-2 expression between squamous cell/adenosquamous carcinomas and adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 19 325–335. 10.1007/s10147-013-0550-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeger H., Perbal B. (2016). CCN family of proteins: critical modulators of the tumor cell microenvironment. J. Cell Commun. Signal 10 229–240. 10.1007/s12079-016-0346-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J., Liao Y., Zhou J., Yang G., Ding K., Zhang X. (2015). Role of WISP3 siRNA in proliferation, apoptosis and invasion of bladder cancer cells. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 8 12792–12800. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Li W., Huang P., Lin L., Ye H., Lin D., et al. (2015). Expression of CCN family members correlates with the clinical features of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 33 1481–1492. 10.3892/or.2015.3709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Chen X., Liu J., Dong X., Jin Y., Tian Y., et al. (2015). Knockdown of WISP1 inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in ALL Jurkat cells. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 8 15489–15496. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]