Abstract

We examine the effects of global trade integration on firm-level adoption of CSR standards as measured by the United Nations’ Global Compact Initiative. Building on policy transfer and economic institutionalism, we propose that country-level participation in trade agreements, and higher levels of regulatory quality, encourages firm-level adoption of CSR standards. We also suggest that participation in these trade agreements stimulates greater adoption of CSR standards from state-owned firms than privately owned firms because those agreements increase the accountability of state firms to supranational institutions, whereas private firms are already accountable to their respective state and domestic institutions. Moreover, we argue that the positive effect of trade agreements on the adoption of CSR standards is higher in countries with higher levels of regulatory quality. These insights are important for research on how economic integration affects firm-level strategies, especially those related to CSR, and for policymakers facing choices as to whether to enter into trade agreements and what types of agreements to enter. Analyses from 152,267 firm-year observations from 11,992 firms in 133 countries spanning 2000–2014 provide robust support for the arguments.

Keywords: corporate social responsibility, state-owned firms, institutional theory, policy transfer theory, global trade integration, regression analysis

INTRODUCTION

I have paid heed to many and various opinions about this issue, which has split public opinion. I have reached the decision today after carefully examining those opinions. I wish to explain to all the people of Japan how I have come to the decision to participate… Now is our last chance. Losing this opportunity would simply leave Japan out from the rule-making in the world. Future historians will no doubt see that “the TPP was the opening of the Asia-Pacific Century.” Japan has to be at the heart of the Asia Pacific Century. I believe that participation in the negotiations for the TPP will be a provident masterstroke.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, March 15, 2013

The past six decades have been marked by advances in regional, transnational, and global (or supranational) integration in international trade, investment, and other economic agreements that provide enhanced access to global markets (Nye & Keohane, 1971). As part of the integration process, individual states relinquish portions of their sovereignty over national laws and regulations (Bohman, 1998; Singh, 2012). This integration, commonly monitored through the World Trade Organization (WTO), includes agreements such as the European Union and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Despite the economic benefits that these integration efforts have provided, recent waves of anti-globalization and anti-integration have forced policymakers to confront challenging questions regarding whether to enter into new trade agreements and whether, and how, to modify existing ones by, for example, adding additional provisions that deepen the level of integration (Dau, Moore, & Barreto, 2019).

Policymakers have clear choices as to whether to enter into trade agreements. The above quote reflects a difficult decision taken by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) to join the negotiation of the Transpacific Partnership 2 years after those negotiations began. Japan had initially declined to participate in the negotiations, but over time Abe and the LDP became convinced that taking part in those negotiations would allow Japan to influence the trading rules and obligations covering this large swath of 14 Asian and Asian-facing nations, despite considerable domestic opposition to Japan’s participation. As agents of their country’s national interests, it is critical that policymakers understand the implications these agreements have for domestic actors – especially firms that are one of the key beneficiaries of trade integration. Indeed, these implications can be sizeable, as seen in the mid-1990s when México joined NAFTA. Although the decision was contentious at the time in México, trade ministers and other officials believed that the agreement was in the best interests of the country, and exercised their authority in negotiating this comprehensive arrangement that had lasting implications on domestic industries and companies. In particular, the Mexican automobile industry had long been shielded from international competition through an array of tariffs and local content and trade balancing requirements (Brid, 1996). However, after joining NAFTA, the industry was forced to comply with newly liberalized standards, including labor, wage, and environmental standards, and has since become a major production hub for both automotive assembly and suppliers.

Simultaneously, a rise in the global expectations for greater corporate responsibility and accountability by multinational enterprises (MNEs) and other firms has resulted in the emergence of global initiatives, such as the United Nations Global Compact (UNGCI) and other private regulatory regimes designed to promote environmental responsibility, human rights, and other social concerns (Elkington, 1998; Hacking & Guthrie, 2008; Gimenez, Sierra, & Rodon, 2012; Dau, Moore, & Soto, 2016). In particular, the UNGCI’s mission is to advance ten universal principals (see Appendix 1) designed to incentivize companies to align their strategies and operations to achieve societal goals and advance the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs). At the core of the UNGCI is the process of upward harmonization in firm-level social and environmental practices through the exchange of knowledge and information, and pressure exerted on companies via the UNGCI and its public and private stakeholders. The concurrent progression of trade and investment integration and global corporate sustainability presents interesting research questions related to whether, and how, increased economic integration may influence firm-level decisions to participate in regimes designed to promote social and environmental responsibility.

For-profit companies are one of the key sets of actors that are the subject of international regulatory regimes designed to advance social and environmental responsibility (Rathert, 2016). As such, corporate social responsibility (CSR) is of increasing interest to scholars of international business (IB), especially the global and country-level factors that may prompt firms to voluntarily join and comply with CSR standards. Within this framework, scholars have sought to understand when and how firms choose to adopt CSR standards, for example, by investigating how market liberalization policies and domestic economic systems impact the adoption of CSR standards in different markets (e.g., Flammer, 2015; Lim & Tsutsui, 2012). However, there has been limited attention to the impacts of global trade and investment agreements on whether or not firms adopt CSR standards. This is surprising given that there has been a rise in integrating CSR-related provisions into trade agreements since 1990 (Van den Putte & Orbie, 2015).

We address this gap by studying the impact of country-level integration through trade and investment agreements on firm-level adoption of CSR standards. Further, we explore how this relationship varies depending on whether firms are private or state-owned, and how the home country’s level of regulatory quality may influence the rate of adoption. We argue that because increased trade integration indicates a willingness of a country to harmonize its policies upwards, increased policy transfer will occur that will result in heightened pressures for firms to adopt CSR standards. Additionally, we suggest that state-owned enterprises (SOEs) experience greater accountability pressures than privately owned enterprises (POEs) because of their relative position as a strategic agent of the state and their desire to gain global legitimacy for themselves and their home countries (Megginson & Netter, 2001; Musacchio & Lazzarini, 2014). Moreover, we argue that regulatory quality has a positive impact on the adoption of CSR standards, and that regulatory quality positively moderates the relationship between trade and investment integration and standards adoption. Analyses of 11,992 firms from 2000 to 2014 across 133 countries offer robust support for these claims.

We contribute to the global strategy and CSR literatures by explicating the interconnectedness of country-level participation in trade agreements and pressures on firms to adopt global CSR standards. Specifically, we combine insights from new institutional economics (North, 1990; Aguilera & Grogaard, 2019) and the policy transfer literature (Dolowitz & Marsh, 1996; Stone, 2012) to elucidate the impact that international trade agreement participation has on firm-level adoption of CSR standards. In addition, we add to the literature on the various impacts of state ownership on firm-level strategic decision-making (Lawson, 1994) by suggesting that international trade agreements can influence and promote voluntary self-regulation behavior by SOEs and also how regulatory quality may further contribute to these effects.

GLOBAL INTEGRATION AND THE ADOPTION OF CSR STANDARDS: A POLICY TRANSFER PERSPECTIVE

Policy Transfer, Economic Institutionalism, and Legitimacy

Policy transfer theory

One studied dimension of globalization and trade integration is the tendency of policies established in one institutional sphere, or geographic jurisdiction, to extend to others. This phenomenon is reflected in the policy transfer literature, which maintains that policy approaches “transfer” via international organizations and bodies, resulting in policy convergence between and among nations (Evans, 2006, 2009a, b; Fang & Stone, 2012). This process involves information and knowledge exchange among national governments, input and advocacy by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and assimilation through international organizations and trade agreements (Dolowitz & Marsh, 2000; Stone, 2000, 2001, 2012).

Scholars suggest that as problems become more globally dispersed, policy transfer occurs at higher frequencies and intensities as countries engage in more cross-border agreements and organizations aimed at collective problem solving (Hulme, 2005; Marsh & Sharman, 2009). For example, concern about disparities in gender equality, especially in developed countries, rose in the 1960s and 1970s. In response, countries in Europe first introduced initiatives that eventually prompted the United Nations (UN) to marshal member states to develop the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. Since its creation in 1979, 189 countries have ratified the agreement, which has in turn led to policy implementation supporting gender equality in the individual member states. This demonstrates a process of institutional convergence as member states align their domestic policies with the standards created by the international organizations and agreements. Thus, these international bodies serve as critical receptors and integrators of divergent national institutions and, in turn, sources of new policy initiatives that influence and constrain national regulations.

Another example can be found in the labor and environmental provisions established in NAFTA. Although each member state of NAFTA retains sovereignty over its domestic laws and regulations, the trade agreement requires that each party implement domestic regulatory policy changes to ensure that “high labor standards” and “high levels of environmental protection” are effectively enforced (Williams, 2018) and that, if one of the NAFTA countries does not observe these requirements, others can pursue a dispute settlement process, potentially resulting in fines or sanctions. These policy changes then influence domestic companies and foreign firms operating within North American borders as new labor and environmental expectations unfold to which firms must adhere (Lattanzaio & Fergusson, 2016). Consequently, worker’s rights protections have improved markedly in the automobile manufacturing industry in Mexico since the ratification of NAFTA (Cimino-Isaacs & Villarreal, 2016).

Although policy transfer ultimately results in greater convergence, the processes leading to it are often not symmetric among actors (Dussauge-Laguna, 2013; Petridou, 2014) in that individual policymakers have considerable influence on these decisions. Power, proximity, and timing all matter. States with higher levels of power have greater influence over the construction of global policies (Dolowitz, 1999; Dolowitz & Marsh, 2000) and powerful states often encourage the creation of global policies that already align with their own domestic policies (Stone, 2004). Conversely, less powerful countries do not have as much influence over the creation of global policies. However, policymakers and trade ministers from both types of countries have agency in influencing the terms of these agreements and deciding whether or not to enter into negotiations, sign, and ratify them.

Economic institutionalism and the adoption of CSR standards

As famously asserted by North (1990: 3), “institutions are the rules of the game in a society.” Traditionally, new institutional economics scholarship in IB has examined the construction of domestic institutions and sought to understand how institutional forces influence firm strategy (Dau, 2016; Peng, 2002; Peng et al., 2008). In particular, this stream of research focuses on domestic regulations and policies, and provides insights for how these policies pressure and guide firm strategy (Peng, 2002). While it is valuable to understand the implications of domestic regulations and policies, it is also important to understand how these domestic policies and actors are influenced by supranational forces (Moore, Brandl, & Dau, 2019; Moore, Dau, & Doh, 2020; Moore, Dau, & Mingo, 2021) and how the resulting national diplomatic initiatives influence the strategies and practices of domestic firms.

Integration in international trade agreements represents one such supranational force. When a country signs and ratifies a trade agreement through the WTO, it pledges to uphold the terms of that agreement. Thus, higher levels of integration indicate a willingness to engage in a degree of policy convergence. While these agreements promote economic liberalization and a reduction of entry barriers, they increasingly also incorporate non-trade, or “flank,” considerations related to social and environmental concerns and protections (Peels, Echeverria, Aissi, & Schneider, 2016). By linking social and environmental commitments to trade agreements, supranational institutions permeate domestic borders (Hepburn & Kuuya, 2011; Waleson, 2015) and influence the standards and regulations being created domestically through policy transfer.1

This type of policy transfer has important impacts for firms. As domestic policies become more closely aligned with supranational ones, firms will be subject to increased pressure to follow these new standards to obtain legitimacy from external stakeholders and safeguard their ‘license to operate’ as members of global society (Bansal & Song, 2017). Specifically, as global initiatives continue to incorporate more explicit CSR commitments, policies that are transferred between states through global organizations continue to both regulate and place a premium on CSR. This results in increased CSR expectations from a variety of stakeholders (both global and domestic) (Rodgers, Stokes, Tarba, & Khan, 2019). Although not all firms have to maintain the same level of legitimacy (see King, 2014 for a discussion on reputational dynamics of firms as it relates to ethical “grey areas”), we believe these cross-institutional pressures created via policy transfer constitute a potentially important driver of firm behavior.

However, not all types of firms respond to institutions in the same way. Indeed, one variant of research has explored how differing ownerships structures – for example state-owned (SOEs) versus privately owned firms (POEs) – influence firm strategy, operations, and approaches to internationalization, proposing that for profit SOEs have unique features that allow them to operate independently of domestic institutions and regulatory structures because they possess powers that insulate them from these pressures (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2017; Dewenter & Malatesta, 2001; Fan, Wong, & Zhang, 2013; Meyer, Ding, Li, & Zhang, 2014).2 Although there is variance in scholarly views of SOEs’ accountability across countries, this stream of literature argues that SOEs are less accountable to domestic institutions than are POEs because they are an active part of the political strategy of the country (Liang, Reng & Sun, 2015). In other words, because the major shareholder for SOEs is essentially the government, they can maintain internal legitimacy even while violating domestic regulations. However, while extant literature has examined the relationship between SOEs and domestic institutions, it has given limited attention to how SOEs interact with supranational institutions. This is surprising given the rise in international trade and investment agreements. Thus, we seek to build on prior literature to offer a more finely variegated understanding of how SOEs are influenced by these agreements.

Global Integration and the Adoption of CSR Standards: Theory and Hypotheses

Globalization has positive and negative externalities (Stallings, 2007). Positive effects include increased cooperation across borders, trade-led economic growth, greater labor mobility and opportunity, and positive knowledge and technological spillovers (Obstfeld & Taylor, 2004; Prakash-Mani, Thorpe, & Zollinger, 2003). Negative effects may include increased pollution, more frequent and intense financial crises, global health epidemics like COVID-19 and Ebola that spread rapidly through borders, industries “hollowing out” and employment dislocation, and increased income and wealth inequality (Baden et al., 2014; Dau & Moore, 2020a, b; Kennedy & Nisbett, 2015; Wheeler, 2001).

Partly as a consequence of these negative impacts, global regulations – both public (state-led) and private (firm and NGO-led) – have emerged to establish common social and environmental standards and codes of conduct (Donno, 2010; Gimenez et al., 2012; Hacking & Guthrie, 2008). Global regulations apply to the global population (e.g., states, firms, citizens, etc.) and are often created by, and enforced through, international organizations, governing bodies, and trade agreements. The Kyoto Protocol, for example, is a relevant global environmental regulation that sets rules for carbon emission levels. This regulation, and others, have emerged, in part, from pressures emanating from civil society actors to encourage social responsibility by both states and the firms they host (Nikolaeva & Bicho, 2011; Tashman & Rivera, 2010) as well as the rise in global society (Meyer, Pope, & Isaacson, 2015), which has restructured actors’ international roles and commitments to CSR. This is evidenced through the increased CSR commitments not only promoted by global regulations and organizations, but also those increasingly attached to trade and investment agreements between countries (Peels et al., 2016).

Global integration and the adoption of CSR standards

Policy transfer theory provides a framework for understanding how policies converge and are transmitted between nations (Benson & Jordan, 2011; Dolowitz & Marsh, 2000). One critical mechanism through which policy transfer occurs is international trade agreements, whose members are national governments (Stone, 1999, 2001, 2004). When states join trade agreements, particularly deeper types of agreements, such as common markets or economic unions, they willingly concede portions of their sovereignty in order to conform their external trade policies, monetary policies, and employment standards with other member countries. Thus, higher levels of integration (in both number and depth of agreements) indicate that a participant country attaches high value in cross-border integration and is willing to engage in upward convergence and harmonization of policies.

Therefore, international trade and investment agreements create supranational institutions based on the collective decisions of member nations. They promote collective action and trust through transparency and policy transferal (Frenk, Gómez-Dantés, & Moon, 2014; Stoddard, 2002). For example, if a state breaks an agreed-upon rule in a WTO trade agreement, a dispute settlement body will rule on the issue and permit aggrieved parties to collect monetary damages and/or impose trade sanctions (Guzman, 2004). Thus, as states join more agreements the transfer of policy unfolds that results in the increased alignment of domestic regulations among participating nations.

As a result, international organizations and trade agreements also influence actors within states, such as firms. Although firms do not directly join the majority of international trade and investment agreements, they are embedded and accountable within the policy networks created around those agreements in that the commitments governments actively make compel changes in the way firms are regulated and operate. For example, if a state joins an agreement that contains specific labor standards, those standards are typically then reflected in domestic law or regulation, and therefore firms within that state will have to adhere to these now harmonized standards. These enforcement mechanisms are coercive in the sense that they are reflected in laws and rules established by member states, but also support the development of a shared understanding about what is acceptable or legitimate both between and within states (Bitektine, 2011; Kölbel & Busch, 2019).

As a result, the more integrated a country becomes in global trade networks, the greater likelihood firms in that country will experience institutional pressures to accede to higher CSR standards, and the more extensive the scope of the agreement, the more intense will be those pressures because the greater likelihood that those more comprehensive agreements include social and environmental provisions. Put differently, the increasing upward harmonization of trade and economic practices that are a function of accession to, and compliance with, trade and investment obligations also spills over to indirect pressures to adhere to higher social and environmental practices that are becoming increasingly expected at the global level. Indeed, we find evidence within our sample indicating that as countries integrate into both more and deeper trade agreements, there is a rise in the number of companies adopting CSR standards. For example, from 2000 to 2004 Australia entered into 12 new trade agreements and in the 5 years that followed 31 Australian companies joined the UNGCI. Austria, Bangladesh, the Netherlands, and Portugal all too experienced increases of at least 15 companies joining the UNGCI in the years following an increase of at least six agreements. As a result, we expect that firms within countries that actively participate in global trade and investment arrangements are incentivized to adopt social responsibility practices.

Hypothesis 1:

Global integration has a positive effect on firm adoption of CSR standards, ceteris paribus.

Firm ownership and the effects of global integration on the adoption of CSR standards

However, not all firms respond the same to global integration. The basic ownership structure of firms – private or state owned – varies in relation to a range of economic and institutional pressures. Although the literature is unsettled regarding the overall accountability of SOEs to governments (see Cuervo-Cazurra, Inkpen, Musacchio, 2014 for a discussion on the current debate), in terms of CSR, research shows that POEs and SOEs face different pressures when deciding whether, and how, to participate in social initiatives (Heath & Norman, 2004; Hofman, Moon, & Wu, 2015).

One stream of literature suggests that SOEs reflect ideological and political priorities of government motivations and are held accountable and derive legitimacy primarily from their political benefactors (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2017). Thus, they are protected to a greater degree from national-level regulatory pressures because they are part of the state’s agenda and strategy, and as such deeply interwoven with the state’s plans (Boardman & Vining, 1989; Claessens, Djankov, & Lang, 2000). Indeed, extant literature has shown that even when SOEs violate national regulations like anti-corruption policies, they do not suffer in terms of profitability (Nguyen & Van Dijk, 2012). Conversely, POEs are more likely to comply with standards and rules established by national governments because they face consequences that SOEs may not (Dewenter & Malatesta, 2001; Megginson & Netter, 2001). Moreover, because members of the boards of SOEs often also serve in political offices, they contribute to the creation of national-level regulations. This is not to suggest that all SOEs influence policies that work in their favor, but it is unlikely that a board member of an SOE would promote a national regulation that directly conflicts with, or penalizes, the SOE.

However, while scholarship has examined the relationship between SOEs and domestic institutions, less attention has been given to the relationship between SOEs and supranational institutions. As SOEs become more globally visible and expand to other jurisdictions, they are often viewed as inefficient, poorly managed, unresponsive to shareholders, and producing poor quality goods and services (Dewenter & Malatesta, 2001). While this reflects poorly on the SOE itself, it also has negative implications for the SOE’s home country, given that the SOE is a direct representation of the state itself.

Thus, we suggest that when states integrate into more trade agreements, SOEs face pressure from their home-country governments to engage in the adoption of CSR standards to overcome criticisms described above because they are often seen by other countries and actors as vestiges of the state themselves. In other words, SOE engagement in the adoption of CSR standards will demonstrate to the global community that the country is interested and actively working towards the collective global agenda – in this case holding firms accountable to promote the protection of people and the planet.

An anecdotal example (directly from our sample) of this behavior can be seen through Petrobras, the large Brazilian state-owned petrochemical company. Despite Petrobras’ involvement in domestic corruption and other scandals, the company is an advanced participant in the United Nation’s Global Compact Initiative and has been for over a decade. Further, it is actively engaged in several other global initiatives that advance CSR, including the Global Reporting Index, the Pro-Gender and Race Equality Program, and the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative. From a Brazilian perspective, Petrobras is an essential part of the country’s domestic and global energy strategy. It is in Brazil’s strategic political interest that external and global stakeholders look favorably on the company. Indeed, this interest is evidenced by Petrobras’ apparent heightened CSR initiatives that followed environmental scandals in 1997 and 2000 (Gabrielli de Azevedo, 2009) that were described as “harmful to the bottom line” and “demoralizing for all employees and Brazilians” (ibid). Thus, for Brazil to remain as an active participant in the international community more broadly, it was essential that Petrobras, which has always been part of the government’s development strategy, better adhere to CSR standards.

Thus, we argue that when countries are more economically integrated they face increased pressure to adopt global CSR standards and that the country’s officials then transfer this pressure to SOEs as they are viewed as operating on behalf of the country itself.

Hypothesis 2:

The effect of global integration on the adoption of CSR standards by firms is positively moderated by state ownership, ceteris paribus.

Regulatory quality and the effects of global integration on the adoption of CSR standards

Although global integration and ownership structures can have a critical impacts on a firm’s adoption of CSR standards, we maintain that the quality of a country’s formal regulatory institutional environment also matters (Dau, Moore, & Kostova, 2020a, b; Dau, Moore, & Newburry, 2020a, b; North, 1990). Regulatory quality refers to the strength of the formal institutional environment of a country (Busenitz, Gómez, & Spencer, 2000; Laffont & Tirole, 1990). It includes the quality of laws and regulations to facilitate business activities, governance systems to encourage stability and trust in the business environment, and enforcement mechanisms to curb malfeasance and corruption (North, 1990; Dau, Moore, & Bradley, 2015). Higher levels of regulatory quality reduce corruption and provide stable business environments (Dau, 2013), facilitating and promoting private sector development and business growth. Countries that have stronger and clearer regulatory frameworks have more capacity to monitor and influence firm behavior (Dau, Moore, & Kostova, 2020a, b).

There is a growing debate on the motivations behind the adoption of CSR standards and the role that institutional and governance may play in that process. Some scholarship has focused on the impact of host-country institutions (Rathert, 2016); the impact of institutions across different types of market economies such as liberal market economies, coordinated market economies, and state-led economies (Jackson & Apostolakou, 2010; Jackson & Rathert, 2016); and the impacts of actors that influence an institutional environment, such as NGOs, external stakeholders, and other public and private actors (Campbell, 2007). We build on this discussion by proposing that as global governance mechanisms are enforced through trade agreements, there is pressure for national governments to transfer these global institutions domestically. Additionally, however, we argue that in countries with high levels of regulatory quality, firm-specific transaction costs to adopt these obligations are reduced in that the overall strong regulatory environment provides a higher baseline from which to make these changes. This, in turn, allows firms more capacity to adopt CSR standards, and they are incentivized to do so to augment market legitimacy (Bansal & Song, 2017). Thus, in countries with higher regulatory quality, governments have more capacity to monitor firms’ adoption of CSR standards and firms are more incentivized to adopt them to remain legitimate.

Hypothesis 3:

Regulatory quality has a positive effect on firm adoption of CSR standards, ceteris paribus.

The interaction between norms and standards at the national and supranational levels jointly influences firm behavior (Kang & Moon, 2012). In our model, global trade integration reflects the supranational-level and a nation’s regulatory profile represents the country-level. Within the framework of economic integration and policy transfer, increased global trade agreements encourage accountability and policy transferal between states (Dolowitz & Marsh, 2012; Marsh & Evans, 2012), prompting states to adhere to the supranational institutions and transfer policies cultivated within the trade agreements. This, in turn, promotes increased domestic regulatory quality to reduce conflict between domestic and global actors (Ford, 2002; Ossa, 2014; Van Hoa, 2010). However, this process is not equal across all countries, as some countries experience additional obstacles to implementing supranational standards based on their domestic capabilities (Nye & Keohane, 1971; Park, 2005). Countries with more power have higher influence over agenda setting and policy creation within the trade agreements (Bohman, 1998; Fang & Stone, 2012). Consequently, these constructed policies are often based on the domestic policies and agendas of the most powerful and influential countries (Dolowitz & Marsh, 1996; Stone, 2008).

As a result, policy transfer is easier and faces fewer obstacles for countries with more power because these countries have fewer policies to adapt and change domestically (Clifton & Díaz-Fuentes, 2014; Mossberger & Wolman, 2003). Conversely, countries with less power and influence have more transfer obstacles resulting in difficulties of actual policy transfer since they will have more regulations to change domestically. These countries may not have the agency or capabilities to enact all of these policy transferals, but they will experience pressure to do so to remain active members in the WTO and their trade agreements. Increased difficulties of policy transfer and adaptation means that the effects of global integration on firm adoption of CSR standards is lower within countries with lower initial regulatory quality levels. More practically, domestic reforms are often stimulated by international treaties, and in turn, influence the pace and degree of domestic reforms, but only where domestic regulatory quality is able to execute those regulatory changes. Thus, as global pressures mandate stronger harmonization of CSR standards, states that want to engage in the global community and international trade and investment must increase their domestic CSR standards, but this process is less challenging for countries with stronger existing regulatory quality.

Hypothesis 4:

The effect of global integration on firm adoption of CSR standards is higher in countries with stronger regulatory quality, ceteris paribus.

METHODS

Sources and Sampling of Data

To test our hypotheses, we use a panel of all for profit firms registered in the UN Global Compact Initiative (UNGCI) (11,992 firms across 133 countries) and all years of data available (2000–2014). The UNGCI, compiled annually since 2000, serves as one of the most complete sources of firm-level adoption of CSR standards for countries across the globe. Firms registered with the UNGCI commit to 10 principles within four broad areas: human rights, labor, the environment, and anti-corruption (see Appendix 1). Other scholars have used the database in different ways, such as to understand: why firms engage in CSR adoption (Runhaar & Lafferty, 2009; Voegtlin & Pless, 2014), the pressures firms experience when making the decision to implement CSR adoption (Cetindamar, 2007; Fritsch, 2008), and the operation and implementation of CSR by the UN itself (UNGCI, 2016). The database lists any firm in the world that has, at one point, signed the UNGCI. The joining date is listed first, followed by the level of CSR adoption, ownership, firm type, number of employees, country of origin, due date for CSR reporting, and industry. Further, if a firm is expelled from the initiative, expulsion date, reason, and petition (if any) to re-join is listed. Within the complete set there are over 5000 expulsions. Unlike some other CSR-related databases, the UNGCI has a truly global reach, allowing for a larger breadth of analysis, and captures adoption of standards data from the firm’s perspective rather than from the host-country perspective. Moreover, since we are specifically interested in the adoption of CSR standards, the UNGCI is appropriate since it is hosted by the United Nations – one of the most central and visible actors in global society.

Additionally, we also collected country-level panel data from the WTO RTA Database. The source, collected annually since 1957, represents the most comprehensive data on country-level trade alliances. Other research has validated the RTA database to examine areas of studies such as the impact of alliances (Powers, 2004), multilateralism on world trade (Goldstein, Tomz, & Rivers, 2007), and the impact of trade networks on governance (O’Brien, Goetz, Scholte, & Williams, 2000). The database registers the name of the RTA and the alliance’s member countries (including signatory and ratification date per member), type, and status. Further, the database records if and when a country leaves or returns to an RTA. We also include country-level controls from World Bank Group’s Development Indicators (WBGDI) dataset. Moreover, it is important to note that the final dataset covers the 2008 financial crisis, thus eliminating the crisis as a potential exogenous shock.

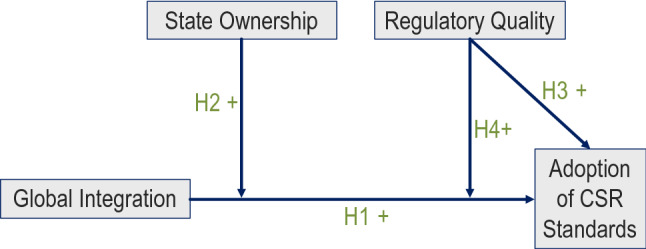

There are 11,992 firms, 133 countries, 15 years (2000–2014), and 152,267 firm-year observations in the final sample (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

Variables and Measures

Table 1 provides a summary of data sources and indicators.

Table 1.

Measures and data sources (including measures used in robustness tests).

| Measure | Description | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firm | Unique indicator of the firm | 1 to 11,992 | WBGDI |

| Country | Categorical indicator of the country (see Table 2) | 1 to 133 | WBGDI |

| Region | Categorical indicator of the geographic region (see Table 2) | 1 to 7 | WBGDI |

| Year | Categorical indicator of the year of analysis | 2000 to 2014 | WBGDI |

| Industry | Categorical indicator of the industry of a firm using the primary SIC classification code | 1 to 11 | UNGCI, SIC |

| Global Compact Member | Dummy indicator for whether or not the firm is a member of the UNGCI | 0 or 1 | UNGCI |

| Global Compact Level | Categorical indicator of the level of membership of a firm within the UNGCI (used in robustness test section) | 0 to 4 | UNGCI |

| Firm Size | Indicator of the firm's number of employees | Continuous | UNGCI |

| Firm Type | Categorical indicator of the firm size with three categories: SME, Company, and FT500 (used in robustness test section) | 1 to 3 | UNGCI |

| Publicly Traded | Dummy indicator for whether or not the firm is publicly traded | 0 or 1 | UNGCI |

| State Firm | Dummy indicator for whether or not the firm's majority owner is the state | 0 or 1 | UNGCI |

| Trade Network Weight | Valued centrality measure for how integrated a country is in global trade networks, aggregated by volume and measured to account for type of network (see text for detailed description) | Continuous | WTO RTA |

| Trade Network Ties | Binary centrality measure of the number of countries (nodes) a particular nation has trade networks with. Each agreement represents one tie. (used in robustness test section) | Continuous | WTO RTA |

| Economic Development | Gross domestic product in thousands of U.S. dollars divided by the total population | Positive | WBGDI |

| Business Cycle | Difference in gross domestic product for the year and the previous year divided by gross domestic product in the previous year | Continuous | WBGDI |

| Regulatory Quality | Regulatory Quality captures perceptions of the ability of the government to formulate and implement sound policies and regulations that permit and promote private sector development. Estimate gives the country's score on the aggregate indicator | Continuous | WBGDI |

| Business Environment | Categorical indicator of the business regulatory environment that assesses the extent to which the legal, regulatory, and policy environments help or hinder private businesses in investing, creating jobs, and becoming more productive (used in robustness test section) | 1 to 6 | WBGDI |

| Government Effectiveness | Government Effectiveness captures perceptions of the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government's commitment to such policies. Estimate gives the country's score on the aggregate indicator, in units of a standard normal distribution (used in robustness test section) | Continuous | WBGDI |

Dependent variable

We measure the adoption of CSR standards using the UNGCI global compact level, which is a categorical measure. Global compact level records the level of CSR adoption that a firm reports and pledges to maintain each year as part of its participation in the UNGCI. The categories for this variable are: 0 = Non-member, 1 = GC General Member, 2 = GC Learner, 3 = GC Active, 4 = GC Advanced. Each level indicates a sequentially increasing degree of adoption of the UNGCI principles. This measures also accounts for firms’ expulsion and subsequent rejoining. Prior work has outlined the measure as a representation of self-reporting of CSR standards at the firm-level (Abrahms, Dau, & Moore, 2019; Dau, Moore, & Newburry, 2020a, b).

Independent variable of interest

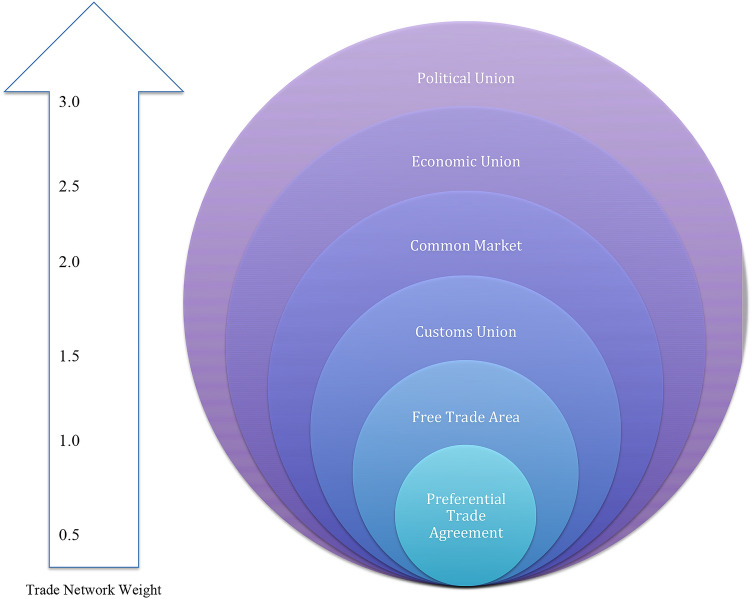

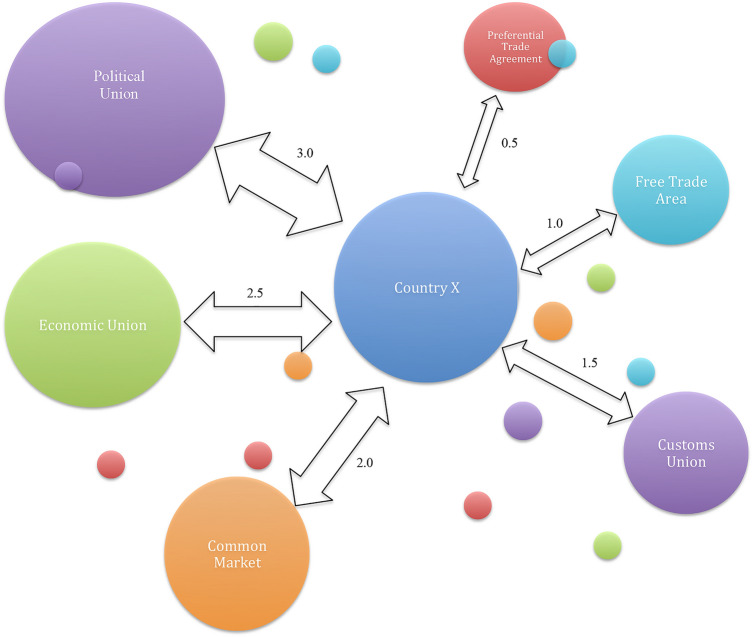

The main independent variable is the degree of global integration. We construct the variable global integration which is a valued centrality measure that captures the number of trade networks and the weight of those ties and therefore how deeply integrated the country is to other countries with which it has agreements. For the purpose of this study, global integration is based and aggregated on the levels of economic integration (see Figure 2): Preferential Trade Agreement, Free Trade Area, Customs Union, Common Market, Economic Union, and Political Union (Hill & Hernández-Requejo, 2013: 452–453; WTO, 2016). Each level of integration is defined as follows based on the definitions from Hill and Hernández-Requejo (2013) and the WTO (2016): preferential trade agreements, such as NAFTA, are trading blocs that allow preferential access of certain products between countries through the reduction, not removal, of trade barriers (WTO, 2016). Customs unions like Mercosur abolish trade barriers and members adopt common external trade policies. Common markets build upon customs unions by allowing for the free movement of the factors of production – labor and capital – among member countries, as with CARICOM. Building on common markets, economic unions, like the European Union, mandate a common currency, standardized tax rates, and common monetary and fiscal policies. Political unions, the deepest integration level, combine all these features and include central political apparatuses and coordinated economic, social, and foreign policy (Hill & Hernández-Requejo, 2013; WTO, 2016). Each level builds upon the prior, and therefore represents a deeper trade network weight (see Figure 2). In order to capture this weight, we assign each a point value from 0.5 to 3.0, building in increments of 0.5, starting at preferential trade agreement and building to political union. These weights are then aggregated per agreement, per country, and per year, and account for whether a country removes itself from an agreement or if an agreement has expired in a given year. For this variable, the higher the score of global integration, the higher the level of global integration in trade agreements. For example, if country X in year XXXX is involved in three Free Trade Agreements and one Political Union, the global integration rating would be 7 (see Figure 3). This measure is captured at the country-level and recorded annually based on data from the WTO’s RTA database.

Figure 2.

Levels of economic integration (based on Hill, 2013; WTO, 2016).

Figure 3.

Example network showing ties and weights (i.e., values) of those ties for each level of global integration.

Unlike existing measures of global trade integration that proxy economic integration through other measures (Capannelli, Lee, & Petri, 2009; Moore et al., 2021), our measure accounts for both the number and depth of trade agreements. See Appendix 2 for more details on the construction of this measure.

Moderating variables

Additionally, given our interest in how SOEs and POEs impact the relationship between global integration and firm adoption of CSR standards across different regulatory environments, we incorporate two moderating variables. First, state ownership identifies whether a firm is privately held or state owned. In order to measure ownership, we use the self-reported classification each firm provides to the UNGCI for whether or not it is state-owned (i.e., state ownership dummy), based on majority ownership. Second, given our interest in the influence of domestic regulatory institutions on the global compact level and the relationship between global integration and global compact level, we include the variable regulatory quality that captures the ability of the government to implement and enforce regulations. We use the continuous measure from the World Bank Group’s Governance Indicators Dataset.

Control variables

To eliminate alternate explanations that affect the adoption of CSR standards, we employ a variety of control variables at multiple levels. First, we control for the country to reduce the different country contexts that may affect firms’ CSR practices. Second, we control for the geographic region to further lessen potential factors associated with regional variation [see Table 2 for a list of countries (133) by region (7)]. We control for region and country separately, since regional factors influence firm behavior, but not all countries within a region are homogenous. Third, we control for the year to address temporal events that could influence CSR standard adoption. Fourth, we control for industry by using the primary SIC classifications because different types of sectors may be more or less prone to adopting CSR standards.3 Fifth, we control for firm size using the number of employees because larger firms may have an advantage at implementing CSR policies. Sixth, we control for whether a firm was publicly traded or not because such firms may experience uneven levels of pressure to adopt CSR standards. Although data is not available to control for firm-level internationalization, several of our controls serve as partial proxies for this variable, as these variables are typically correlated with internationalization. Seventh, we control for the business cycle as represented by gross domestic product growth (GDPG), as this growth may influence a firm’s ability and capacity to adopt CSR practices (Martin & Parker, 1995). Eighth, we control for the economic development in each country using gross domestic product per capita (GDPC) because the wealth levels may have a tendency to promote the adoption of CSR standards. Finally, we use a 1-year lag to let the impacts of global trade integration influence firm-level adoption of CSR standards.

Table 2.

List of countries by geographic region.

(Source WBGDI)

| North America | Europe and Central Asia | Middle East and North Africa |

| Bermuda | Albania | Algeria |

| Canada | Andorra | Kingdom of Bahrain |

| Mexico | Armenia | Egypt |

| United States of America | Austria | Iran |

| Azerbaijan | Iraq | |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | Belarus | Israel |

| Antigua and Barbuda | Belgium | Jordan |

| Argentina | Bosnia and Herzegovina | The State of Kuwait |

| Barbados | Bulgaria | Lebanese Republic |

| Plurinational State of Bolivia | Croatia | Libya |

| Brazil | Cyprus | Morocco |

| Chile | Czech Republic | Oman |

| Costa Rica | Denmark | Qatar |

| Dominica | Estonia | Kingdom of Saudi Arabia |

| Dominican Republic | Finland | Syrian Arab Republic |

| Ecuador | France | Tunisia |

| El Salvador | Georgia | United Arab Emirates |

| Guatemala | Germany | Yemen |

| Guyana | Greece | |

| Haiti | Hungary | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| Honduras | Iceland | Angola |

| Jamaica | Ireland | Benin |

| Nicaragua | Italy | Cabo Verde |

| Panama | Kazakhstan | Cameroon |

| Paraguay | Latvia | Democratic Rep. of the Congo |

| Peru | Liechtenstein | Côte d'Ivoire |

| Trinidad and Tobago | Lithuania | Ethiopia |

| Uruguay | Luxembourg | Gabon |

| Bolivarian Rep. of Venezuela | The FYR of Macedonia | Guinea |

| Republic of Moldova | Kenya | |

| East Asia and the Pacific | Monaco | Republic of Liberia |

| Australia | Montenegro | Madagascar |

| Cambodia | Netherlands | Malawi |

| China | Norway | Mali |

| Indonesia | Poland | Mauritius |

| Japan | Portugal | Mozambique |

| Republic of Korea | Romania | Namibia |

| Malaysia | Russian Federation | Nigeria |

| Mongolia | Serbia | Rwanda |

| Myanmar | Slovak Republic | Sao Tome and Principe |

| New Zealand | Slovenia | Senegal |

| Philippines | Spain | Republic of Seychelles |

| Singapore | Sweden | Sierra Leone |

| Thailand | Switzerland | Somalia |

| Viet Nam | Turkey | South Africa |

| Ukraine | South Sudan | |

| South Asia | United Kingdom | Sudan |

| Afghanistan | UNMIK/Kosovo | Tanzania |

| Bangladesh | Uzbekistan | Togo |

| India | Uganda | |

| Maldives | Zambia | |

| Nepal | Zimbabwe | |

| Pakistan | ||

| Sri Lanka |

RESEARCH DESIGN

To ensure the reliability of our results, we employ a time series ordinal logistic regression model with correction for panel-specific autocorrelation. This method is appropriate for both the panel structure of the data and the characteristics of the dependent and independent variables (Baum, 2006; Zeger, Liang, & Albert, 1988). The data is structured hierarchically as follows: firm-year, firm, countries. As a result of this structure, the random effects model helps to control for unobserved heterogeneity (Lee, 2002).

Additionally, we followed Bliese and Ployhart’s (2002) testing sequence to construct four levels of models that each build on the prior level. Sequential modeling helps to confirm that the results are not impacted by missing data and mitigates the effects of violations of sphericity among the errors (Ployhart, Holtz, & Bliese, 2002). Finally, we standardize all continuous variables to mitigate the potential effects multicollinearity and facilitate the interpretation of the results (Frazier, Tix, & Barron, 2004; Lee, 2002). The following is the specific model used:

When testing Hypothesis 1 and 3, the interaction terms (i.e., β4, and β5), are excluded to allow for the examination of the general impacts of global integration and regulatory quality, independently, on firm adoption of CSR standards. In these models, if β1 and β3 are positive and significant, it suggests that global integration and regulatory quality have positive effects on a firm’s adoption of CSR standards, without distinction between SOEs and POEs.

When testing Hypothesis 2, we add the first interaction term (i.e., β4), state ownership, to highlight its effect on the relationship between global integration and the adoption of CSR standards. These results need to be analyzed to account for the categorical moderation (Frazier et al., 2004; Woolridge, 2002). In this model, β1 captures the impact of global integration on the adoption of CSR standards for the omitted baseline category, POE. If β1 is positive and significant, that indicates that the effect of global integration on the adoption of CSR standards is positive for POEs. β4 captures the differential effect of global integration on the adoption of CSR standards between POEs (the baseline category) and SOEs. If β4 is positive and significant, that indicates that the effect of global integration on the adoption of CSR standards is significantly greater for SOEs than for POEs.

When testing Hypothesis 4, the second interaction term is added (i.e., β5) to examine the moderating effect of regulatory quality on the relationship between global integration and the adoption of CSR standards. These models employ a continuous moderator. If β1 is positive and significant, the effect of global integration on the adoption of CSR standards is positive. β5 Captures the differential effect of global integration on the adoption of CSR standards within divergent regulatory contexts. If β4 is positive and significant, the effect of global integration on the adoption of CSR standards is higher in countries with higher regulatory quality.

RESULTS

Table 3 provides summary statistics and correlations. Global integration values (mean = 41.33) range from 0 to 106. The average number of employees of the firms in our dataset is 5347. The average regulatory quality of each country is 0.67. There is limited potential correlation between variables, aside from the last three variables in Table 3. To address this, we took two steps. First, we reran the analyses without these variables and obtained the same original results. Second, we employed a variance inflation factor (VIF) test. Because of the country and region dummies, as well as the high number of controls, it is unsurprising that our initial VIF exceeded the suggested cutoff of 10 (Kutner, Nachtsheim, Neter, & Li, 2004). However, after removing these controls our results are upheld and the VIF score (mean = 2.32) indicates the reduced potential for multicollinearity. Additionally, we ran the full models with controls but without the region dummy, while maintaining the country dummy, to ensure that the interactions were not inflating our results. The results remained consistent, reducing the potential impacts of multicollinearity, but we retain the control variables because of their theoretical importance.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Global Compact Level | 0.64 | 1.17 | ||||||||

| 2. | Integration Score | 41.33 | 28.92 | 0.23 | |||||||

| 3. | State Firm | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.01 | – 0.02 | ||||||

| 4. | Publicly Traded | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.19 | – 0.01 | – 0.05 | |||||

| 5. | Firm Size | 5347.27 | 31,331.13 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.27 | ||||

| 6. | Economic Development | 22,212.94 | 18,721.55 | 0.13 | 0.65 | – 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.06 | |||

| 7. | Economic Growth | 3.24 | 3.85 | – 0.10 | – 0.47 | 0.03 | – 0.02 | 0.00 | – 0.43 | ||

| 8. | Regulatory Quality | 0.67 | 0.82 | 0.04 | 0.64 | – 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.80 | – 0.43 |

Correlations with an absolute value greater than or equal to 0.01 are significant at 0.05 level (two-tailed)

Descriptives for the 133 countries, 7 regions, 11 sectors, and 15 years are not included for the sake of parsimony

Main Test Results

Table 4 shows the results of the time series ordinal logistic regression models for the impact of global integration on the adoption of CSR standards and how this varies for POEs and SOEs. In the table the following indicators demonstrate p-value thresholds: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (Meyer, Van Witteloostuijin, & Beugelsdijk, 2017). The models are organized sequentially as variables are added (Frazier et al., 2004). Model 1 includes only control variables. Model 2 adds the variable state ownership and regulatory quality. Model 3 adds global integration, testing Hypothesis 1. Model 4 adds the interaction effect between state ownership and global integration, testing Hypothesis 2. Model 5 adds the interaction effect between regulatory quality and global integration, testing Hypotheses 3 and 4.

Table 4.

Results of the analyses of the time series ordinal logistic models for the effect of global integration on the adoption of CSR standards.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publicly Traded | 1.60*** (0.06) | 1.60*** (0.06) | 1.61*** (0.06) | 1.61*** (0.06) | 1.63*** (0.06) |

| Firm Size | 0.37*** (0.02) | 0.37*** (0.02) | 0.37*** (0.02) | 0.38*** (0.02) | 0.38*** (0.02) |

| Economic Development | 0.50*** (0.04) | 0.50*** (0.04) | 0.37*** (0.04) | 0.36*** (0.04) | – 0.21*** (0.05) |

| Economic Growth | 0.09 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Country Control | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Region Control | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Year Control | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Industry Control | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| State Firm | 0.15 (0.12) | 0.16 (0.12) | – 0.16 (0.12) | 0.15 (0.14) | |

| Integration Score | 0.52*** (0.03) | 0.50*** (0.03) | 0.16*** (0.03) | ||

| Regulatory Quality | 0.31*** (0.06) | 0.31*** (0.06) | 0.46*** (0.06) | 0.44*** (0.06) | 0.87*** (0.06) |

| Integration Score × State Firm | 1.10*** (0.09) | 1.42*** (0.11) | |||

| Integration Score × Regulatory Quality | 0.74*** (0.03) | ||||

| Wald χ2 | 28,638.31*** | 28,639.37*** | 28,657.29*** | 28,654.79*** | 28,732.23*** |

| Log Likelihood | − 111,063.54 | − 111,062.75 | − 110,893.13 | − 110,813.91 | − 110,384.65 |

| Firms | 11,992 | 11,992 | 11,992 | 11,992 | 11,992 |

| Observations (n) | 152,267 | 152,267 | 152,267 | 152,267 | 152,267 |

Indicators for each country (133), region (7), industry (11), and year (15) are included in the models, but their coefficients are not reported for the sake of brevity

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Model 3 shows a positive and statistically significant result for the coefficient of global integration (β1), suggesting that firms in countries that are more globally integrated are more likely to engage in the adoption of higher-level CSR standards. Because our global integration measure is standardized, the magnitude of the coefficient indicates that an increase in one standard deviation of global integration increases the adoption of CSR standards by 5.2 percentage points (Model 3). The results of this model provide support for Hypothesis 1.

Model 4 provides the effects of the moderating relationship. As mentioned above, the coefficient of global integration (β1) indicates the effect on the baseline category, POEs, while the effect of the interaction term (β3) indicates the differential effect between POEs (the baseline category) and SOEs. The coefficient of global integration (β1) is positive and statistically significant, suggesting that the effect of global integration on the adoption of higher-level CSR standards is especially positive for POEs. Moreover, the coefficient of the interaction term (β3) is also positive and highly statistically significant, suggesting that the effect of global integration on the adoption of CSR standards is significantly higher for SOEs than POEs. To estimate the effect of global integration on the adoption of higher-level CSR standards of SOEs, we calculate the linear combination between these variables, 1.10, which is positive and highly statistically significant. Together, these findings provide further support for Hypothesis 1 and also support for Hypothesis 2, suggesting that the effect of global integration on the adoption of CSR standards is positive for both POEs and SOEs, while the effect is greater for SOEs.

Model 5 provides the effects of the regulatory quality as both an independent variable and as a moderator. The coefficient of the interaction term (β3) is positive and highly statistically significant. This suggests that the direct impact of regulatory quality on the adoption of CSR standards is positive, finding support for Hypothesis 3. The coefficient of the interaction term (β5) is positive and highly statistically significant. This suggests that the impact of integration on the adoption of CSR standards is higher in countries with higher starting levels of regulatory quality, finding support for Hypothesis 4.

Robustness Tests

We conducted several additional analyses to corroborate our findings and ensure their consistency under alternative models, measures, and assumptions.

Alternate test designs

To supplement our main model, we employed three additional approaches: (1) a time series ordinal probit model with correction for panel-specific autocorrelation; (2) a mixed-effects logit regression model with correction for panel-specific autocorrelation; and (3) a time series probit regression using our alternate dependent variable measure (described below) to ensure reliability. The results of these tests provide consistent support for the hypotheses.

SOE accountability variation

Extant literature suggests different countries have different levels of SOE accountability. China mandates that SOEs join the UNGCI. Therefore, we ran the main analyses without Chinese firms to ensure that our results were not being driven by China. Our results remained consistent.

Regional variation

Research has also indicated that regional variation could also impact how integration impacts the adoption of CSR standards. Thus, we re-ran the models while systematically removing one region each time. All of the results remained consistent.

Endogeneity

We employed a two-stage Heckman Test to lessen the possibility of self-selection bias. Stage one predicts the probability of a company joining the UNGCI based on the following metrics: firm size, GDPC, GDPG, whether the firm is a state firm, and whether the firm is publicly listed. Stage two includes these probabilities as additional predictors. The results yield consistent findings.

Alternate moderating variable

We employ government effectiveness, a continuous measure collected by the WB to assess how effective government institutions are. This serves as an alternate continuous moderating variable. The results were upheld.

Alternate dependent variable

As an alternate measure of our dependent variable (global compact level) used in the main analysis, we employed global compact member, a dichotomous measure of whether or not a firm adopts CSR standards. To account for this dichotomous variable, we ran a time-series logit model. Our original findings are corroborated.

Alternate independent variables

First, as an alternate measure to global integration, we used trade network ties. Compiled from the WTO RTA database, trade network ties is a binary centrality measure that indicates the number of trade network ties a country has in a given year. It counts how many trade ties to other countries (i.e., nodes) the focal country has in any given year.4 Crucially, this measure accounts for whether, and when, a country exits an agreement. As a second alternative measure, we used total agreements. This continuous measure captures the total number of formally registered trade and investment agreements at the country level per year. This measure accounts for a country’s exit from an agreement. These models support our original results.

Alternate control variables

We employ firm type as an alternative categorical variable to firm size as reported on the annual UNGCI membership reports. We used a categorical variable, firm type, as an alternative indicator of the size of a firm. This variable includes three types of firms: 1 = SME (Small or Medium Enterprise); 2 = Company; and 3 = FT (Financial Times) 500 Company. Results support our initial findings.

Given the large number of controls, we also ran the tests after removing them all. Our results were upheld.

Post Hoc Analysis

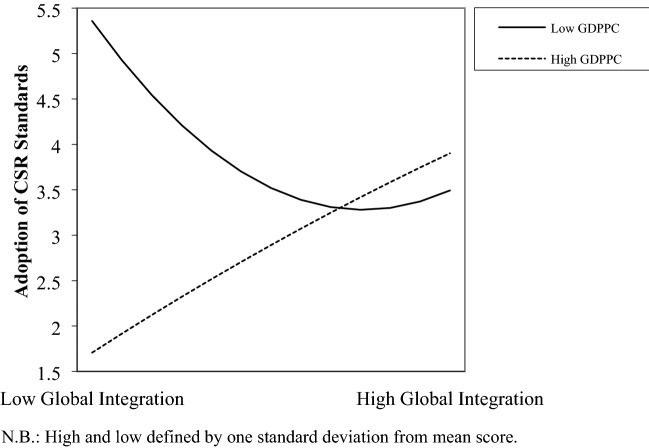

Although beyond the scope of our main research question, we also recognize the importance of a country’s level of economic development as it relates to the adoption of CSR standards.5 This may be especially relevant in terms of the relationship between our global integration measure and the potential for increasing adoption of CSR standards; in other words, countries that have higher or lower levels of development may experience a stronger or weaker effect of increasing levels of integration on the adoption of CSR standards. Thus, as a post hoc analysis we ran our analyses using a continuous moderating variable: economic development (as measured by a country’s Gross Domestic Product per Capita (GDPPC) captured annually from the World Bank Development Indicators Dataset). Our results yield interesting results for countries with both high and low GDPPC. Specifically, we find that for countries with higher GDPPC there is a linear and positive relationship between integration and the adoption of CSR standards. However, for countries with low GDPPC, the relationship is somewhat U-shaped. At low levels of integration (e.g., when a country is just beginning to sign and ratify its first trade agreements) countries reflect lower levels of firm-level CSR standards adoption but as they continue to join more trade agreements and/or accede to agreements featuring deeper levels of economic integration, they demonstrate greater firm-level propensity to adopt CSR standards. This may be because as less developed countries first enter into trade agreements, they don’t yet have the institutional infrastructure and capacity to support firm-level CSR standards adoption; as they join more and more integrative agreements, knowledge transfer among their counterparts facilitates this capacity building. In some ways, this finding is consistent with the environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) that has hypothesized that the relationship between environmental quality and economic development follows a similar pattern such that environmental degradation worsens as poor economies grow somewhat more wealthy, until average income reaches a certain point over the course of development when environmental quality improves (see Yasin, Ahmas, & Chadhary, 2020). Figure 4 shows the interactions between economic integration and CSR standards adoption at high and low levels of GDP per capita.

Figure 4.

Interaction among global integration and the adoption of CSR standards at high and low levels of GDP per capita. N.B.: high and low are defined by one standard deviation from mean score.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In this paper we explore the impact of global integration on the adoption of CSR standards. Two contemporary global trends highlight the importance of our research. First, there is a rise in global initiatives (such as the UNGCI) that represent public and private stakeholders’ increased expectation for greater firm-level attention to corporate responsibility and sustainability. These initiatives promote upward harmonization and global coordination of firms and stakeholders, including countries and their policy makers. Second, recent waves of anti-globalization have forced these same policy makers to make difficult decisions regarding the future of their trade and investment agreements. These decisions could have lasting impacts on the harmonization efforts promoted by global initiatives and our research is thus timely as it examines the nexus of these two trends. More specifically, we integrate perspectives from economic institutionalism with an allied perspective from political science, policy transfer theory, to explore how supranational pressures in one domain may influences a firm’s decision to adopt CSR standards in another. We suggest that international agreements create indirect pressures through the process of policy transfer for firms to engage in upward harmonization of CSR standards. Further, we propose that these supranational institutions have a differential impact on SOEs’ responses to these stimuli, and that regulatory quality also plays a role in whether firms in a given country are inclined to commit to a global CSR standards. The results of the analyses, using different methods and measures, provide robust support for the arguments. Thus, through this examination we gain a deeper understanding of how SOEs and POEs operate and add a new dimension to the accountability structure that different categorizations of firms from different regulatory environments navigate.

Main Contributions and Implications for Policy

Contributions to theory

We contribute to two main literatures within IB. First, we add to the global strategy and CSR literatures by identifying and modeling how international trade and investment agreements, through policy transferal, encourage the adoption and upward harmonization of CSR standards by firms. Scholars have suggested that CSR is a “cross-sectional” phenomenon that requires concurrent examination of why firms engage in CSR and why countries and global stakeholders promote it (Bitektine, 2011; Kölbel & Busch, 2019; Sahlin-Andersson, 2006). This literature focuses on the importance of global civil society and private regulatory frameworks such as those established by the United Nations and other intergovernmental organizations (Sahlin-Andersson, 2006). We extend this literature by demonstrating that trade agreements, which accelerate policy transfer, represent additional mechanisms through which CSR standards are harmonized upwards. Extant literature on policy transfer and transnational institutional pressures has examined how global organizations and their initiatives have influenced domestic-level regulatory changes (Malets & Quack, 2017). Some scholars argue that transnational institutions can construct a global community through “mutual interactions across national boundaries” (Djelic & Quack, 2011). However, this literature has largely focused on either policy changes, institutional shifts, and economic outcomes, or sociological outcomes. Our results indicate that these mechanisms and pressures can be observed at the firm-level.

Second, we add two contributions to the literature on state ownership. The IB literature on SOEs versus POEs has focused on how these different ownerships structures create variation in the accountability pressures that firms face. POEs are held accountable to national-level governments and institutions. SOEs, however, often make strategic decisions for political gains and are more protected than POEs from following domestic regulatory institutions because they also have the ability to shape those regulations (Bruton, Peng, & Xu, 2015; Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2014; Megginson & Netter, 2001). While extant literature on state ownership has examined the profitability of SOEs (Dau, 2013) and the internationalization strategies of SOEs (Meyer et al., 2014), the literature has yet to examine the way SOEs interact with global institutions and regulations. Specifically, we argue that as global problems continue to increase inter-state accountability, domestic governments are pressured to transfer global (private) regulations domestically. We extend this logic to the firm-level to propose that because SOEs are in effect vestiges of the state itself, they also experience this increased pressure to follow global regulations in order to augment their legitimacy and the global reputation of their home country.

Finally, we make a methodological contribution to IB by offering a more nuanced operationalization of trade integration. Unlike previous measures, our approach incorporates the underlying social and political facets of trade integration that influence national-level policymaking, and transitively, firm behavior. This measure can be applied and potentially further refined in future scholarship.

Implications for policymakers and practitioners

Our findings are important for policymakers facing decisions regarding whether and how to engage in global integration, as well as for managers and shareholders responsible for making CSR strategic decisions. In response to the backlash again globalization, some governments are exiting trade agreements, as President Trump did with the Trans-Pacific Partnership, or restructuring them to better reflect concerns about job loss, trade, and the environment, as with NAFTA’s renegotiation as the U.S.–Mexico–Canada Agreement. The latter example suggests that revising trade agreements and institutions may be one strategy for allowing continued integration and higher commitment on the part of multinationals to CSR and broader societal concerns.

Our findings also have implications for policymakers as they face depleted resources and the emergence of competing private regulation. If global agreements and CSR commitments provide a broad basis for firm-level CSR practices, to what extent should national and sub-national regulation build on or complement them? We believe these policy spheres are complementary and mutually reinforcing. We see policy transfer as a consequence of increased trade integration between countries, leading to upgraded CSR practices. As such, increased integration can accelerate adoption of CSR-like practices.

Additionally, our insights on the difference between SOEs and POEs are critical for politicians serving as decision makers for both states and SOEs. Many jurisdictions have and continue to privatize SOEs and this may have implications for their likelihood to engage in global CSR agreements. Further, policymakers and politicians involved with SOEs would benefit from monitoring how integrated their home country is in trade agreements to better understand the SOEs adoption of CSR standards especially if those SOEs may be subject to privatization.

Limitations

Despite these contributions, we encourage future scholars to address the limitations of our research. First, we study the adoption of CSR standards through the UNGCI, but there are several different mechanisms within this adoption. Although our study uses different measures to provide robustness, future studies may include more measures and other data to assess the unique dimensions involved with the adoption of CSR standards. Second, we examine the adoption of CSR standards and not CSR compliance. Future work could tease out this distinction by examining whether firms respond to global integration via legitimate “substantive” versus “symbolic” CSR (Mahoney, Thorne, Cecil, & LaGore, 2013). Third, our study examines developing and developed countries without direct differentiation for their idiosyncrasies nor the differential effects on the relationship we explore. The literature suggests that emerging markets face different pressures than advanced markets; future studies could examine either emerging markets or advanced markets specifically. Fourth, in our analysis we explore the differential effects on SOEs vs POEs; future research might examine other firm-level ownership and governance differences, including pre-existing CSR performance. Additionally, future research may pay increased attention to the variation of accountability that SOEs and POEs face in different contexts. Although we provide a robustness check for this variance, there is room for future scholarship to examine it more closely, potentially through a comparative case study between firms in China versus firms in Sweden. Fifth, although we included a large number of control variables, there are other factors we would like to include, like firm-level internationalization and firm-level integration in global value chains, but at present that data is not easily available. In addition, integration may have effects that go beyond adoption of CSR standards to affect other relevant aspects of firms social and political strategies. Further, we use a sample of firms that are self-identified and does not include the full universe of firms. Future studies may extend this research by selecting a particular country or region and carrying out comparative analyses on firms that elect to self-identify and those that do not. Once again, while we provide a robustness check for regional variation and level of economic development, future research may be able to expand on these findings by comparing two or more regions directly in one study or by examining the importance of economic development level and relative power status of a country.

Conclusion

Two concurrent global trends that have emerged in recent years are the growth of global governance mechanisms promoting the responsibility of firms and governments in social and environmental affairs, and a rise in anti-globalization and economic de-integration. Each of these trends challenge established global governance structures and the efficacy of trade agreements and the international organizations that oversee them. Recent criticism of the WTO’s dispute settlement mechanism reflects a frustration and disillusion with global institutions and a retreat toward nationalism and even some more established economists have called for a step back from the deep integration that has characterized recent waves of integration (see for example Rodrik, 2019). These pressures pose difficult policy choices for governments and policymakers regarding economic integration, or de-integration, as well as CSR policies aimed at holding firms responsible.

Our basic finding that economic integration encourages increased the adoption of CSR standards amongst firms sheds some light on how these forces comingle and interact. It suggests that policymakers should consider and factor this effect into the trade and economic arrangements they negotiate. Indeed, increasingly trade and investment arrangements do contain labor and environmental regulations, a development that seemingly recognizes that trade can be used as a lever to advance other social and environmental goals. Firms that are advocating for those agreements must also be prepared to at least adopt the CSR standards, as this is increasingly part of the expectation that with trade and integration must come greater (upward) harmonization of social and environmental responsibilities. In this context, our research yields important insights for policymakers deciding the future of their commitment to trade agreements and what these decisions might mean for firm-level strategic choices, for firms positioning themselves to take advance of those agreements, and for a civil society that is increasingly voicing its expectation that companies will work with governments and other stakeholders to improve their overall social as well as economic impact.

NOTES

1While not all trade agreements have these non-trade considerations, they have become far more common place since the early 1990s which is directly relevant for our sample which begins in 2000.

2We focus on for profit SOEs, not internal government branches or not for profits. Indeed, these SOEs are perhaps held more accountable to domestic institutions than POEs. However, we encourage future scholars to examine how these SOEs may be influenced by supranational institutions.

3Based on the primary SIC classification, the 11 sectors covered in the database are: Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing; Mining; Construction; Manufacturing; Transportation, Communications, Electric, Gas, Oil and Services; Wholesale Trade; Retail Trade; Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate; Services; Public Administration; and Non-Classifiable.