Abstract

Background and Aims:

Various biomarkers are used for predicting outcome from sepsis and septic shock but single value doesn't give clear-cut picture. Changing trends of serum lactate and red cell distribution width (RDW) gives more accurate information of patient outcome. So, aim of this prospective observational study was to identify the correlation, for initial and changing trend of blood lactate level and RDW, with 28-day mortality in sepsis and septic shock.

Material and Methods:

Patient who fulfills the criteria of sepsis and septic shock, according to the consensus conference published in 2016, were included in this study. All patients were resuscitated and managed according to institutional protocol for sepsis and septic shock. Serum lactate and RDW was obtained from arterial blood gas and complete blood count, respectively. Serum lactate and RDW were recorded at 0 h, 6 h, 24 h, day 2, day 3, day 7, week 2, and week 3. Mean between two groups were compared with student t-test. Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficient was used for establishing correlation between two continuous data. P value < 0.05 indicates significant difference between two groups.

Results:

There is positive correlation between serum lactate and RDW at all-time point in non-survival group while negative correlation was found in survival group except on day1 and 2.

Conclusion:

Changing trends of serum lactate and RDW can be used as a prognostic marker in patient of sepsis and septic shock.

Keywords: Red cell distribution width, sepsis, serum lactate

Introduction

Sepsis is defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction initiated by a dysregulated host response to infection.[1,2] Septic shock is defined as a subgroup of sepsis with circulatory and cellular/metabolic dysfunction associated with a higher risk of mortality.[3] Both severe sepsis and septic shock are the foremost causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with mortality rates approaching 20–30% in the most recent clinical trials.[4,5,6]

In clinical practice, various biomarkers are used for diagnosing and predicting outcome from sepsis but none of them have very good specificity to differentiate sepsis from other inflammatory disorders. In clinical practice, they are widely used for monitoring of the severity of infectious process or for ruling out infections. These biomarkers have prognostic implications; increasing levels are associated with poor outcome and vice versa.

Since long time blood lactate levels are used as a surrogate of tissue hypoperfusion in critically ill patients admitted to intensive care unit (ICU).[7,8,9] Current guidelines for severe sepsis and septic shock recommended that patient with an initial blood lactate level above 4 mmol/L should be promptly resuscitated.[10] Many studies also suggest that lower elevation of blood lactate levels are also associated with increased risk of death.[9] Therefore, optimal lactate cutoff that should trigger resuscitation in critically ill patients still remain unclear.

Red blood cell distribution width (RDW) is a measure of red blood cell size heterogeneity. RDW is the well-established prognostic biomarker in various cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases such as heart failure, acute pulmonary embolism, acute coronary artery disease, stroke, etc.[11,12,13,14,15,16] Few studies also indicated that high RDW in patients with community-acquired pneumonia; severe sepsis and septic shock are associated with increased mortality.[17,18,19] These studies also suggested that high RDW level had a very close relationship with poor prognosis, indicating that patients with high RDW level need increased focus in clinical practice.

In this study, our objective was to identify the correlation, for initial and changing trend of blood lactate level and RDW, with 28-day mortality among medical patients with sepsis or septic shock admitted to the ICU from the emergency department.

Material and Methods

After institutional ethical committee approval and written informed consent from patient's relative, the present study was conducted from Feb 2017 to Feb 2018. Total 60 patients of age group of 18–70 years who fulfill the criteria of sepsis and septic shock according to the consensus conference published in 2016 were included in this study. Most common cause of sepsis was pneumonia, abdominal sepsis, urosepsis, and pancreatitis. Exclusion criteria include patient refusal, chronic condition which elevate RDW and serum lactate level (like chronic liver disease, tropical diseases), and readmission to ICU within a single hospital stay.

After the admission in ICU, patients were attached with standard monitors, baseline parameters recorded and treatment was started according to ICU protocol. Arterial and central venous line was inserted and blood samples were obtained for lactate and RDW, respectively. Serum lactate was obtained through the arterial gas analysis (analysis by cobas b 221 blood gas system) and RDW was obtained from complete blood count (analysis by Beckmann coulter). Further sampling for lactate and RDW was done at 6 h, 24 h, and days 2, 3, 7 and at the end of week 2 and 3. Other relevant investigations were sent according to patient's condition. Twenty-eight days mortality was considered as a primary outcome.

Data analysis

The statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 16. Chi-square test used for categorical variable and student's t-test was used for comparing means of the two groups. To correlate two continuous data Pearson and Spearman Correlation coefficient was used. P value <0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

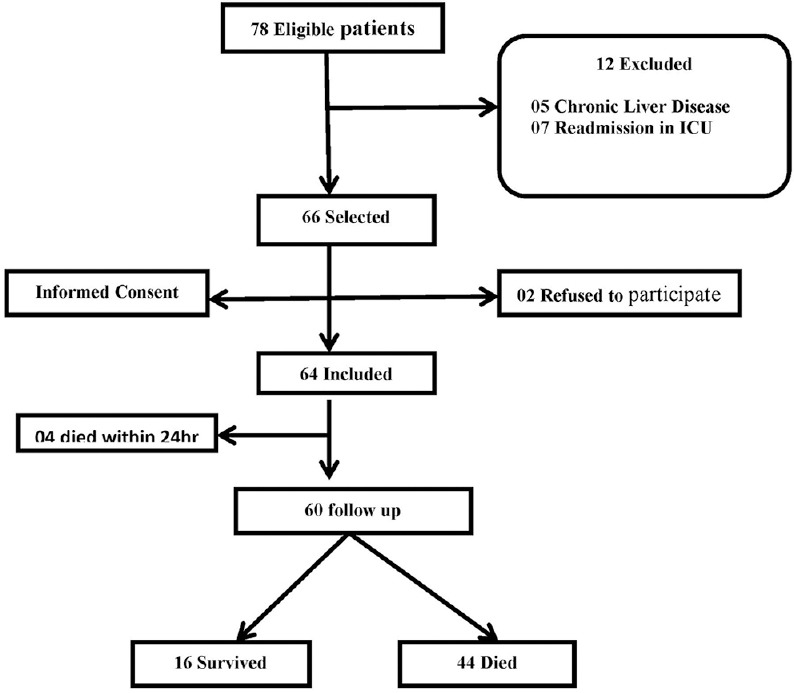

Out of 78, 60 patients completed the study [Figure 1]. Baseline parameters including age, sex, and hemodynamic parameters were comparable between survival and non-survival groups except acute physiologic assessment and chronic health evaluation-II (APACHE II) score which was statically significant between two groups [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient studied

Table 1.

Demographic profile and baseline parameters between survival and non-survival group

| Parameters | Survival (n=16) | Non-survival (n=44) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 37.25±16.91 | 35.07±14.41 | 0.622 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 43.8% | 47.7% | |

| Female | 56.2% | 52.3% | |

| APACHE II | 18.56±3.55 | 26.77±8.50 | <0.001 |

| SBP | 106.19±13.18 | 106.23±24.30 | 0.995 |

| DBP | 63.25±14.09 | 59.23±14.58 | 0.344 |

Data presented as mean±SD or number (%). P<0.05 considered as significant. SD=Standard Deviation. APACHE: acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; SBP: Systolic blood pressure; DBP: Diastolic blood pressure

Serum lactate was significantly higher in non-survival group comparing to survival group at 24 h and thereafter (P < 0.05) [Table 2]. Comparison of RDW between survival and non-survival was statically significant at all-time intervals except at 3 weeks [Table 3].

Table 2.

Comparison of serum lactate between survival and non-survival patient at different time interval

| Parameter | Survival (n=16) | Non-survival (n=44) | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactate 0 h | 6.68±2.62 | 7.63±3.27 | −1.036 | 0.305 |

| Lactate 6 h | 4.90±2.23 | 6.08±2.47 | −1.665 | 0.101 |

| Lactate 24 h | 1.83±0.74 | 3.13±1.43 | −3.359 | 0.001 |

| Lactate 2nd day | 1.35±0.61 | 3.76±1.51 | −5.996 | <0.001 |

| Lactate 3rd day | 1.23±0.59 | 3.81±1.68 | −5.182 | <0.001 |

| Lactate 7th day | 0.87±0.07 | 3.64±1.05 | −7.382 | <0.001 |

| Lactate 2nd week | 1.30±0.17 | 3.69±0.92 | −4.340 | 0.001 |

| Lactate 3rd week | 0.90±0.01 | 3.87±1.10 | −3.613 | 0.036 |

Data presented as mean±SD. P<0.05 considered as significant. SD: Standard deviation

Table 3.

Comparison of red cell distribution width between survival and non-survival patient at different time interval

| Parameter | Survival (n=16) | Non-survival (n=44) | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDW 0 h | 14.86±0.43 | 16.49±1.56 | −4.118 | <0.001 |

| RDW 6 h | 14.90±0.46 | 16.55±1.52 | −4.240 | <0.001 |

| RDW 24 h | 15.06±0.36 | 16.88±1.32 | −5.244 | <0.001 |

| RDW 2nd day | 15.31 0.65 | 17.24±1.25 | −5.495 | <0.001 |

| RDW 3rd day | 15.28±0.65 | 17.36±1.25 | −5.927 | <0.001 |

| RDW 7th day | 15.34±0.45 | 17.67±1.10 | −5.410 | <0.001 |

| RDW 2nd week | 15.30±0.17 | 18.25±1.55 | −3.193 | 0.007 |

| RDW 3rd week | 15.00±0.00 | 18.57±2.51 | −1.896 | 0.131 |

Data presented as mean±SD. P<0.05 considered as significant. RDW: Red cell distribution width

There was negative correlation between serum lactate and RDW at 0 h, 6 h, 24 h, day 7, weeks 2 and 3 while positive correlation on days 2 and 3 but statically not significant in survival group [Tables 4 and 5]. In non-survival group, positive correlation was found at all-time intervals and it was statically significant at 24 h, day 2 and 3 [Tables 4 and 5].

Table 4.

Correlation between serum lactate and RDW in survival and non-survival patient at different time interval

| Parameters | Survival | Non-survival | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | r | P | |

| Lactate vs. RDW | ||||

| Lactate vs. RDW 0 h | −0.347 | 0.188 | 0.087 | 0.574 |

| Lactate vs. RDW 6 h | −0.351 | 0.183 | 0.126 | 0.416 |

| Lactate vs. RDW 24 h | −0.311 | 0.259 | 0.464 | 0.002 |

| Lactate vs. RDW 2nd day | 0.290 | 0.315 | 0.584 | 0.000 |

| Lactate vs. RDW 3rd day | 0.452 | 0.105 | 0.672 | 0.000 |

| Lactate vs. RDW 7th day | −0.715 | 0.071 | 0.097 | 0.629 |

| Lactate vs. RDW 2nd week | −1.000 | 0.000 | 0.386 | 0.215 |

| Lactate vs. RDW 3rd week | - | -- | 0.720 | 0.280 |

Data presented as a Spearman correlation coefficient (r) and Pearson correlation coefficient (P). Correlation coefficient value ranges from −1 to+1.

Table 5.

Cutoff value of serum lactate and RDW at different time interval from receiver operating characteristics curve

| Test result variable | Area | P | Cutoff value | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactate 0 h | 0.548 | 0.570 | 6.85 | 54.5 | 50.0 |

| RDW 0 h | 0.874 | 0.000 | 15.0 | 86.0 | 81.2 |

| Lactate 6 h | 0.631 | 0.083 | 2.2 | 84.6 | 73.3 |

| RDW 6 h | 0.884 | 0.042 | 15.35 | 90.9 | 88.7 |

| Lactate day 1 | 0.848 | 0.053 | 3.0 | 84.6 | 73.3 |

| RDW day 1 | 0.947 | 0.027 | 15.4 | 90.9 | 88.7 |

| Lactate day 2 | 0.967 | <0.001 | 1.95 | 97.7 | 85.5 |

| RDW day 2 | 0.944 | <0.001 | 15.5 | 97.5 | 85.7 |

| Lactate day 3 | 0.983 | <0.001 | 1.78 | 95 | 85.7 |

| RDW day 3 | 0.954 | <0.001 | 16.0 | 92.7 | 92.9 |

P value of <0.05 considered as significant

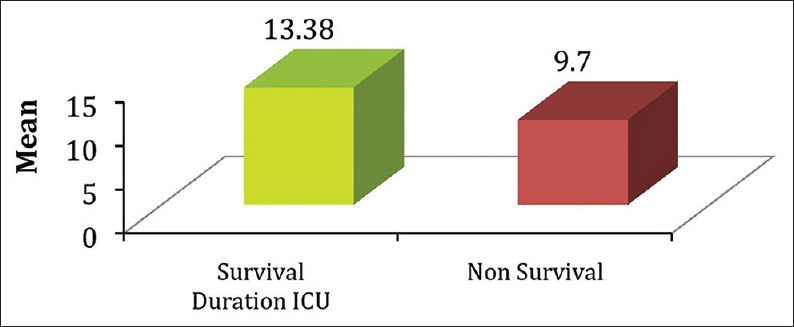

Mean duration of ICU stay was significantly higher in survival group compared to non-survival (13.38 ± 6.73 vs. 9.70 ± 5.28 days) (P < 0.05) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Comparison of mean duration of ICU stay between survivor and non-surviersurvivors

Discussion

In non-survival group, positive correlation was found between serum lactate and RDW at all-time intervals might be because of higher baseline and persistent rise in RDW and serum lactate. This is supported in previous study by Kim et al. which states that the ascending trend of RDW in the first 72 h of admission is associated with an unfavorable prognosis.[20] Previous study by Jo et al. reported that RDW was significantly higher in non-survival group in patients with sepsis and septic shock.[21] Serum lactate and RDW at 0 h and 6 h were statistically non-significant maybe because of no rise in the RDW level before 24 h. On days 1, 2, and 3 statistically significant positive correlation was found, which can be explained by rise in RDW and persistent hyperlactemia.

In survival group, negative correlation was found most of the time which can be explained by augmented lactate clearance. Puskarich et al.'s study showed that early lactate normalization (within 6 h) was a predictor of survival in patients being treated for sepsis and septic shock.[22] Another previous study of Bakker et al. showed that lactate clearance measured 24 h after admission was a significant predictor of in-hospital mortality.[23] In survival group, serum lactate decreasing trend towards normal value in comparison to non-survival group where serum lactate level was decreasing from initial level but hyperlactemia persisted for longer duration (6 h, 24 h). This shows lactate clearance was more in survival group as compared to non-survival group.

In our study, there was no significant increase in RDW in initial 24 h, but after 24 h, significant increase was found in RDW in both the groups and more increase in non-survival group than survival group. Most of the studies showed that high RDW level was associated with the likelihood of poor outcome. Lorente et al.[24] demonstrated that RDW levels on days 1, 2, 3, and 7 were associated with prognosis in septic patients. This meant that dynamic observation of RDW levels seemed more valuable in clinical practice.

Limitation of study

Our setup is tertiary care center; hence, patients rarely come from direct community; most of the patients were referred from other hospitals so they were more seriously ill and had received some form of treatment. Also, we did not use a definite antibiotic protocol common to all patients for treatment, so the bias due to treatment heterogeneity cannot be ruled out.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all our ICU staff, without whom the study could not have been completed.

References

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, Seymour CW, Liu VX, Deutschman CS, et al. Sepsis definitions task force: Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: For the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:775–87. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ, Brunkhorst FM, Rea TD, Scherag A, et al. Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis: For the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:762–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yealy DM, Kellum JA, Huang DT, Barnato AE, Weissfeld LA, Pike F, et al. A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1683–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peake SL, Delaney A, Bailey M, Bellomo R, Cameron PA, Cooper DJ, et al. Goal-directed resuscitation for patients with early septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1496–506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mouncey PR, Osborn TM, Power GS, Harrison DA, Sadique MZ, Grieve RD, et al. Trial of early, goal-directed resuscitation for septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1301–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nichol AD, Egi M, Pettila V, Bellomo R, French C, Hart G, et al. Relative hyperlactatemia and hospital mortality in critically ill patients: A retrospective multi-centre study. Crit Care. 2010;14:R25. doi: 10.1186/cc8888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang YR, Um SW, Koh WJ, Suh GY, Chung MP, Kim H, et al. Lactate level and mortality in septic shock patients with hepatic dysfunction. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011;39:862–7. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1103900510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wacharasint P, Nakada TA, Boyd JH, Russell JA, Walley KR. Normal-range blood lactate concentration in septic shock is prognostic and predictive. Shock. 2012;38:4–10. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318254d41a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:165–228. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2769-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muhlestein JB, Lappe DL, Anderson JL, Muhlestein JB, Budge D, May HT, et al. Both initial red cell distribution width (RDW) and change in RDW during heart failure hospitalization are associated with length of hospital stay and 30-day outcomes. Int J Lab Hematol. 2016;38:328–37. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zorlu A, Bektasoglu G, Guven FM, Dogan OT, Gucuk E, Ege MR, et al. Usefulness of admission red cell distribution width as a predictor of early mortality in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:128–34. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turcato G, Serafini V, Dilda A, Bovo C, Caruso B, Ricci G, et al. Red blood cell distribution width independently predicts medium-term mortality and major adverse cardiac events after an acute coronary syndrome. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:254. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.06.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bekler A, Tenekecioglu E, Erbag G, Temiz A, Altun B, Barutçu A, et al. Relationship between red cell distribution width and long-term mortality in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome. Anatol J Cardiol. 2015;15:634–9. doi: 10.5152/akd.2014.5645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demir R, Saritemur M, Atis O, Ozel L, Kocaturk I, Emet M, et al. Can we distinguish stroke and stroke mimics via red cell distribution width in young patients? Arch Med Sci. 2015;11:958–63. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2014.40995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J, Kim K, Lee JH, Jo YH, Rhee JE, Kim TY, et al. Red blood cell distribution width as an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in out of hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2012;83:1248–52. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bello S, Fandos S, Lasierra AB, Mincholé E, Panadero C, Simon AL, et al. Red blood cell distribution width [RDW] and long-term mortality after community-acquired pneumonia. A comparison with proadrenomedullin. Respir Med. 2015;109:1193–206. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JH, Chung HJ, Kim K, Jo YH, Rhee JE, Kim YJ, et al. Red cell distribution width as a prognostic marker in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:72–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Özdogan HK, Karateke F, Özyazici S, Özdogan M, Özaltun P, Kuvvetli A, et al. The predictive value of red cell distribution width levels on mortality in intensive care patients with community-acquired intra-abdominal sepsis. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2015:21–35. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2015.26737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim CH, Park JT, Kim EJ, Han JH, Han JS, Choi JY, et al. An increase in red blood cell distribution width from baseline predicts mortality in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock.Crit. Care. 2013;17:R282. doi: 10.1186/cc13145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jo YH, Kim K, Lee JH, Kang C, Kim T, Park HM, et al. Red cell distribution width is a prognostic factor in severe sepsis and septic shock. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:545–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puskarich MA, Trzeciak S, Shapiro NI, Albers AB, Heffner AC, Kline JA, et al. Whole blood lactate kinetics in patients undergoing quantitative resuscitation for severe sepsis and septic shock. Chest. 2013;143:1548–53. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishna U, Joshi SP, Modh M. An evaluation of serial blood lactate measurement as an early predictor of shock and its outcome in patients of trauma or sepsis. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2009;13:66–73. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.56051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorente L, Martin MM, Abreu-González P, Solé-Violán J, Ferreres J, 'Labarta L, et al. Red blood cell distribution width during the first week is associated with severity and mortality in septic patients. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]