Abstract

Purpose

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is an inexpensive antifibrinolytic agent that significantly reduces peri-operative blood loss and transfusion requirements after total hip and knee replacement. This meta-analysis demonstrates the effects of TXA on blood loss in total shoulder replacement (TSR) and total elbow replacement (TER).

Methods

We systematically searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL from inception to September 03, 2020 for randomised controlled trial (RCTs) and observational studies. Our primary outcome was blood loss. Secondary outcomes included the need for blood transfusion, and post-operative venous thromboembolic (VTE) complications. Mean differences (MD) and relative risks with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported.

Results

Four RCTs and five retrospective cohort studies (RCS) met eligibility criteria for TSRs, but none for TERs. RCT data determined that TXA administration significantly decreased estimated total blood loss (MD −358mL), post-operative blood loss (MD −113mL), change in haemoglobin (Hb) (MD −0.71 g/dL) and total Hb loss (MD −35.3g) when compared to placebo. RCS data demonstrated significant association between TXA administration and decreased in post-operative blood loss, change in Hb, change in Hct and length of stay. There was no significant difference in transfusion requirements or VTE complications.

Conclusion

TXA administration in safe and effective in patients undergoing primary TSR: it significantly decreases blood loss compared with placebo and is associated with shorter length of stay compared with no treatment. No significant increase in VTE complications was found. TXA administration should be routinely considered for patients undergoing TSR. Further research is needed to demonstrate the treatment effect in patients undergoing TER.

Keywords: Tranexamic acid; Arthroplasty, replacement, shoulder; Arthroplasty, replacement, elbow; Blood loss, surgical; Venous thromboembolism; Blood transfusion; Systematic review; Meta-analysis

Highlights

-

•

TXA effectively reduces perioperative blood loss in patients undergoing shoulder replacement.

-

•

TXA does not significantly increase VTE events in patients undergoing shoulder replacement.

-

•

Further research is required to demonstrate the efficacy of TXA for total elbow replacements.

1. Introduction

Total shoulder replacement (TSR) and total elbow replacement (TER) are effective treatments to relieve pain and improve function in patients. TSR is most commonly used to treat patients with osteoarthritis, cuff tear arthropathy and trauma, whereas TER is more commonly used to treat patients with trauma, inflammatory arthropathy and osteoarthritis.1,2 Both interventions have been performed in greater numbers year-on-year.3 It is well established that joint replacements are associated with significant intra-operative blood loss, which increases the likelihood for allogenic blood transfusion4,5 and an additional risk of morbidity and mortality.6, 7, 8, 9

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is an inexpensive and increasingly commonly-used antifibrinolytic agent that has been shown to significantly reduce peri-operative blood loss and transfusion requirements after total hip (THR) and knee replacement (TKR)10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 as well as other surgical procedures.18,19 Furthermore, TXA use has been associated with reduced surgical drain outputs, lower falls in haemoglobin (Hb) and haematocrit (Hct), lower incidence of periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) and shorter length of stay. A recent meta-analysis that evaluated venous thromboembolism (VTE) outcomes following primary TSR and TER demonstrated that the pooled incidence across studies was less than 1% in the first three months, but the incidence can range from 0.04 to 16%.20 Evidence also suggests that TXA administration does not increase the risk of VTE complications in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty but TSR and TER were not studied.21 Hence, it will be useful to establish whether the administration of TXA in patients undergoing TSR and TER procedures affects the risk of post-operative VTE events.

Previous meta-analyses, with the most recent in 2018, have demonstrated that TXA use in TSR can decrease total blood loss, Hb change, drain output and the need for blood transfusion.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 However, five of these studies combined interventional with observational data in their pooled analyses,23, 24, 25, 26, 27 which is methodologically incorrect, thus limiting the validity of their conclusions. Furthermore, these previous reviews were based on pooled analysis of very few trials, hence reducing the power to make effective head-to-head comparisons. The most recent meta-analysis pooled the results of only three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and three retrospective cohort studies (RCSs).22 Since the publication of the most recent review, new evidence has been published. Similar evidence for the benefits of TXA in TER is notably lacking, with only one case series found by preliminary search.28 There is a need to comprehensively summarise the evidence given that previous reviews are out of date or methodologically flawed, with persisting uncertainties about outcomes.

The aims of this review are threefold: 1) to incorporate the latest evidence regarding the effects of TXA on blood loss in TSR into an updated meta-analysis that accounts for the shortcomings outlined above; 2) to synthesise evidence regarding TXA use in TER; and 3) to identify any gaps in the existing literature.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data sources and search strategy

The review was registered a priori in the PROSPERO prospective register of systematic reviews (ID: CRD42020207353) and conducted according to a predefined protocol and in line with the PRISMA guidelines. We searched for RCTs or observational study designs (prospective or retrospective case-control, prospective cohort, retrospective cohort, case-cohort and nested-case control) that compared TXA use with usual care/placebo/no treatment in adults undergoing primary TSR or TER. We systematically searched the databases of MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL from inception to September 03, 2020. There were no restrictions on language. The computer-based searches used a combination of free and MeSH search terms and keywords related to the population (e.g., “shoulder replacement,” “elbow replacement”), and intervention (e.g., “tranexamic acid”). We used a combined search strategy for both TSR and TER. The search was complemented by manually screening the reference lists of retrieved articles and utilising the “Cited Reference Search” function in Web of Science to obtain any additional studies that were missed by the search strategy. Any previously published systematic reviews and meta-analyses were also screened for studies that met our eligibility criteria. The detailed search strategy has been provided in Appendix 1.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

We included comparative RCTs or observational studies that compared TXA with usual care/placebo/no treatment in patient populations that underwent primary TSR (anatomic: “ATSR; ” or reverse: “RTSR”) or primary TER and reported on blood loss and/or other outcomes. The primary outcome was blood loss. Secondary outcomes included the need for blood transfusion, change in Hb or Hct levels, drain output and VTE complications. We excluded: revision arthroplasty; hemiarthroplasty; arthroscopic procedures; animal studies and cadaveric studies.

2.3. Study selection and data extraction

Once the searches were completed, the results were imported into Rayyan,29 an online bibliographic tool. One reviewer (RLD) initially screened the titles and abstracts and removed any duplicates to provide a list of potentially relevant articles. Full-text screening of these articles was then performed independently by two reviewers (RLD, JRV) against predefined eligibility criteria. Any discrepancies regarding the eligibility of an article were discussed, and consensus was achieved through a third reviewer (SKK). One reviewer (RLD) independently extracted data and conducted quality assessments using a standardised data collection form. A second reviewer (JRV) independently repeated the process to verify the data. Data were extracted on the lead author, year of publication, geographical location, study design, number of participants, mean age, percentage of males, type of surgery, intervention and comparator/control, duration of follow-up, outcome measures and degree of adjustment for potential confounders. We also extracted data on relevant study characteristics to permit the risk of bias assessments. Authors of eligible studies were contacted to provide further information if there were missing data for the extracted fields.

2.4. Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias within individual RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB 2) tool,30 a validated tool for assessing the quality of randomised studies. This tool assesses risk of bias for the randomisation process, deviations from the intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selective reporting. Each of these domains is assessed as low risk, some concerns or high risk, and then an overall judgement of the risk of bias is provided for each study. The risk of bias within individual observational studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias in Non-randomised Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool, a validated tool for assessing the quality of non-randomised studies.31 This tool assesses the risk of bias for confounding, participant selection, classification of interventions, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, outcome measurements and selective reporting. Risk is quantified in each domain as low risk, moderate risk, serious risk or critical risk, then an overall judgement of the risk of bias is provided for each study.

2.5. Statistical analysis

A meta-analysis was performed using RevMan 5.4 software (Cochrane Collaboration) and Stata version MP 16 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas). Outcome data from RCTs and observational studies were analysed separately. Summary measures were presented as mean differences (95% confidence intervals, CIs) for continuous outcomes and relative risks (RRs) (95% CIs) for binary outcomes. For continuous data, if the mean or standard deviation (SD) was not reported, we estimated the mean and variance from the reported median, range, and sample size as recommended by Hozo et al.,32 to facilitate a consistent approach to the meta-analysis. Relative risks were calculated from the extracted raw counts for the intervention and comparator. A narrative synthesis was performed for studies that could not be pooled.

Heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochrane χ2 statistic and the I2 statistic. The inverse variance (IV) weighted method was used to combine pooled summary measures using random-effects (RE) models to minimise the effect of inter-study heterogeneity. Two-sided statistical significance of 0.05 was used. We planned to evaluate publication bias using funnel plots and Egger's regression symmetry tests if a sufficient number of studies met our inclusion criteria. Subgroup analysis to explore the origins of heterogeneity using random-effects meta-regression was also planned.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

Our search strategy identified 455 potentially relevant citations, and this was reduced to 368 after duplicates were removed. After the initial screening of titles and abstracts, 19 full-text articles remained for further evaluation, and a further five were obtained by manually scanning the reference lists of the retrieved articles. Fifteen of these papers failed to meet the eligibility criteria. Therefore, nine studies were deemed eligible for inclusion in this systematic review and meta-analysis.33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 A PRISMA flow chart is provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

3.2. Study characteristics

Table 1 provides a summary of the characteristics of the included studies. Four included studies were RCTs (three in the USA, one in Austria) and five were RCSs (four in the USA, one in South Korea). All studies compared TXA (intravenous in eight studies, topical in one RCT) to either no treatment or placebo (normal saline). Six studies assessed blood loss in patients undergoing both ATSR and RTSR (three RCTs, 3 RCSs), two studies assessed RTSR only (one RCT, one RCS) and one study assessed ATSR only (one RCS). Most studies were not explicit regarding the duration of their follow up periods beyond the time the patients were discharged from the hospital. All four RCTs compared TXA (n = 188) against placebo (n = 187), and all five RCSs compared TXA (n = 370) against no treatment (n = 288). Additional comparators within individual studies (e.g., topical thrombin) were not included in our analysis. Across the nine included studies, 1033 procedures were performed: 522 ATSR and 511 RTSR. No studies that compared TXA administration to usual care/placebo/no treatment for patients undergoing TER were identified. Missing outcome data and/or clarifications were sought from authors where required, but no responses were returned.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Author Year Location |

Study Type | Participants (n) | Age (years) Mean ± SD (range) |

Gender | Surgery | Intervention | Comparator 1 | Comparator 2 | Outcomes Primary Secondary |

Length of Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abildgaard 2016 USA |

RCS | 171 | ATSR: 70 (53–87) RTSR: 71.1 (53–90) |

100 M 71 F |

77 ATSR 94 RSTR |

IV TXA n = 77 35 ATSR/42 RTSR |

No treatment n = 94 42 ATSR/52 RTSR |

N/a |

Total blood loss Change in Hb; Change in Hct; Drain output; Transfusion rate |

Not stated |

|

Belay 2020 USA |

RCS | 283 | IV TXA: 65.7 ± 10.1 Topical thrombin: 68.2 ± 8.2 No treatment: 68.8 ± 9.1 |

138 M 146 F |

283 ATSR | IV TXA n = 135 135 ATSR |

No treatment n = 58 58 ATSR |

Topical thrombin n = 90 90 ATSR |

Post-op Hb Operative time; Total blood loss; Transfusion rate; Length of stay; Readmission rate |

Not stated |

|

Budge 2019 USA |

RCS | 80 | IV TXA: 69 Topical TXA: 68 No treatment: 71 |

41 M 39 F |

51 ATSR 29 RSTR |

IV TXA n = 28 17 ATSR/11 RTSR |

Topical TXA n = 28 15 ATSR/13 RTSR |

No treatment n = 24 19 ATSR/5 RTSR |

Change in Hb Transfusion rate; Length of stay; Wound complications; VTE complications; Discharge destination |

Not stated |

|

Cvetanovich 2018 USA |

RCT | 108 | 66.4 ± 10.1 | 51 M 57 F |

49 ATSR 59 RSTR |

IV TXA n = 52 23 ATSR/29 RTSR |

Placebo n = 56 26 ATSR/30 RTSR |

N/a |

Total blood loss Transfusion rate; Hb loss (weight); Estimated blood loss; Length of stay; VTE complications; Readmission rate; Infection; Return to theatre |

90 days |

|

Friedman 2016 USA |

RCS | 194 | Not stated | 79 M 115 F |

97 ATSR 97 RTSR |

IV TXA n = 106 54 ATSR/52 RTSR |

No treatment n = 88 43 ATSR/45 RTSR |

N/a |

Change in Hb Change in Hct; Transfusion rate; Length of surgery; Duration in recovery; Length of stay |

Not stated |

|

Gillespie 2015 USA |

RCT | 111 | 67 (41–86) | 49 M 62 F |

44 ATSR 67 ATSR |

Topical TXA n = 56 22 ATSR/34 RTSR |

Placebo n = 55 22 ATSR/33 RTSR |

N/a |

Drain output Change in Hb; Transfusion rates Complications |

Not stated |

|

Kim 2017 South Korea |

RCS | 48 | IV TXA: 73.2 ± 4.4 No treatment: 74.2 ± 4.4 |

9 M 39 F |

48 RTSR | IV TXA n = 24 24 RTSR |

No treatment n = 24 24 RTSR |

N/a |

Hb change Hct change; Drain output; Complications |

12 months |

|

Pauzenberger 2017 Austria |

RCT | 54 | IV TXA: 70.3 ± 9.3 (46.3–87.8) Placebo: 71.3 ± 7.9 (53.7–84.3) |

38 M 16 F |

26 RTSR 28 RTSR |

IV TXA n = 27 15 ATSR/12 RTSR |

Placebo n = 27 11 ATSR/16 RTSR |

N/a |

Drain output Change in Hb; Change in Hct; Total blood loss; Transfusion rate; Haematoma rate; Pain score (VAS); Complications |

Not stated |

|

Vara 2017 USA |

RCT | 102 | IV TXA: 67 ± 9 Placebo: 66 ± 9 |

42 M 60 F |

102 RTSR | IV TXA n = 53 53 RTSR |

Placebo n = 49 49 RTSR |

N/a |

Total blood loss Operative time; Change in Hb; Change in Hct; Drain output; Complications (any); VTE complications; Infections |

6 weeks |

ATSR = anatomic total shoulder replacement; Hb = haemoglobin; Hct = haematocrit; HSD = honest significant difference; IV = intravenous; NSAIDs = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; RCS = retrospective cohort study; RCT = randomised controlled trial; RTSR = reverse total shoulder replacement; TXA = tranexamic acid; VAS = Visual Analogue Score; VTE = venous thromboembolism.

3.3. Risk of bias

According to the RoB 2 risk of bias tool, three RCTs were deemed to be of low risk of bias, and one was deemed to have some concerns. The ROBINS-I tool indicated that all five RCSs were assessed to be of moderate risk of bias. The risk of bias and quality assessments for individual articles are included in Appendices 2 (RCTs) and 3 (RCSs).

3.4. Estimated total blood loss

Total blood loss was reported in four TSR studies.33,34,40,41 RCT data showed total blood loss to be significantly lower in the TXA group than the placebo group (MD −357.92 mL; 95% CI 504.27, −211.58; p<0.00001; Fig. 2 top). RCS data showed total blood loss to be lower in the TXA group compared with no treatment, but the difference was not statistically significant (MD −132.78 mL; 95% CI 275.12, 9.56; p=0.07; Fig. 2 bottom).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot for estimated total blood loss (top = RCT data only; bottom = RCS data only).

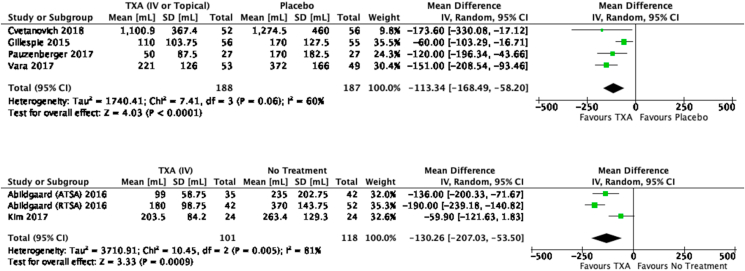

3.5. Drain output (post-operative blood loss)

Drain output was used as a surrogate marker of post-operative blood loss, and this was reported in six TSR studies.33,36,38, 39, 40, 41 RCT data showed drain output to be significantly lower in the TXA group than the placebo group (MD −113.34 mL; 95% CI 168.49, −58.20; p<0.0001; Fig. 3 top). RCS data also showed post-operative blood loss to be significantly lower in the TXA group compared with no treatment (MD −130.26 mL; 95% CI 207.03, −53.50; p=0.0009; Fig. 3 bottom).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for drain output (post-operative blood loss) (top = RCT data only; bottom = RCS data only).

3.6. Change in Hb

Change in Hb was reported in four TSR studies.33,38,39,41 RCT data showed the change in Hb to be significantly lower in the TXA group than the placebo group (MD −0.71 g/dL; 95% CI 1.07, −0.36; p<0.0001; Fig. 4 top). RCS data also showed the change in Hb to be significantly lower in the TXA group compared with no treatment (MD −0.70 mg/dL; 95% CI 0.93, −0.48; p<0.00001; Fig. 4 bottom).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot for change in Hb (top = RCT data only; bottom = RCS data only).

3.7. Change in Hct

Change in Hct was reported in two TSR RCSs,33,39 but no RCTs. The data showed the change in Hct to be significantly lower in the TXA group compared with no treatment (MD −1.86%; 95% CI 2.47, −1.25; p<0.00001).

3.8. Total Hb loss

Total Hb loss was reported in two TSR RCTs,36,41 but no RCSs. The data showed the total Hb loss to be significantly lower in the TXA group compared with the placebo group (MD −35.25g; 95% CI 54.54, −15.96; p=0.0003).

3.9. Length of stay

Length of stay was reported in four TSR studies.34,36,37,41 RCT data showed a slight increase in length of stay in the TXA group compared with the placebo group (MD 0.11 days; 95% CI 0.16, 0.39; p=0.43), which was not significant. RCS data also showed a decrease in length of stay in the TXA group compared with no treatment (MD −0.19 days; 95% CI 0.35, −0.03; p=0.02), which was significant.

3.10. Operative time

Operative time was reported in two TSR RCSs,34,37 but no RCTs. The data demonstrated a slight decrease in operative time in the TXA group compared with no treatment, which was not significant (SMD −0.19 min; 95% CI 0.79, 0.41; p=0.53). This finding was echoed in one RCT,41 which also found no significant difference in operative time (p=0.527).

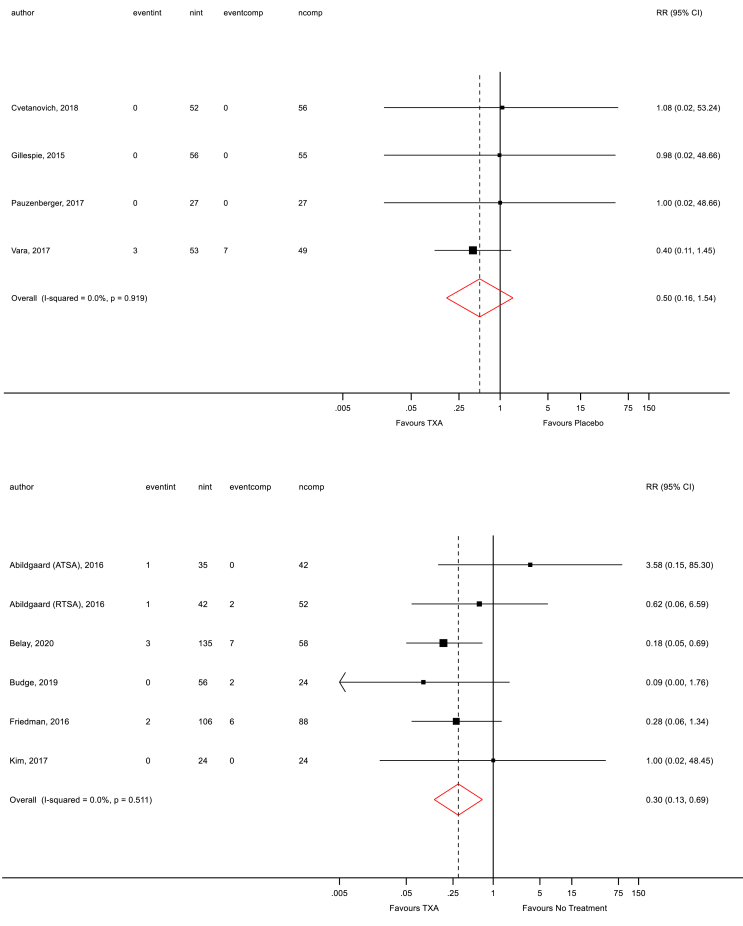

3.11. Transfusion requirements

The overall proportion of patients requiring transfusions in each treatment arm was low. Transfusion requirements were reported in all nine TSR studies.33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 RCT data showed a decrease in the number of blood transfusions in the TXA group compared with the placebo group (RR 0.50; 95% CI 0.16, 1.54; p=0.919; Fig. 5 top), but this was not significant. Similarly, RCS data also showed a non-significant decrease in the number of blood transfusions in the TXA group compared with no treatment (RR 0.30; 95% CI 0.13, 0.69; p=0.511; Fig. 5 bottom).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot for transfusion rates (top = RCT data only; bottom = RCS data only).

3.12. VTE complications

VTE complications were only reported in two RCTs,36,41 but no RCSs. The data showed VTE complications to be lower in the TXA group compared with the placebo group (RR 0.52; 95% CI 0.05, 5.62; p=0.705), but this was not significant.

3.13. Publication bias and subgroup analysis

It was not possible to assess publication bias due to the low number of included studies. Subgroup analysis to explore the origins of heterogeneity was not possible due to limited data.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest, most comprehensive and up to date systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of TXA compared with usual care/placebo/no treatment in patients undergoing primary TSR (anatomic or reverse) to date. The search strategy did not yield any relevant studies to investigate the intervention effect in patients undergoing TER, and we have identified this as an area that requires research in the future. Four RCTs and five RCSs of TSRs were eligible for inclusion in this review, and all were deemed to be of low-to-moderate risk of bias.

Interventional data in this meta-analysis demonstrates that the administration of peri-operative TXA significantly decreases estimated total blood loss, post-operative blood loss (drain output), change in Hb and total Hb loss when compared to placebo. Observational data also demonstrated a significant association between peri-operative TXA administration and decreases in post-operative blood loss (drain output), change in Hb, change in Hct and length of stay. Whilst a decrease in transfusion requirements and VTE complications were noted, these were not significantly different.

Previous meta-analyses in this field have been published between 2017 and 2018, with the number of included studies in each ranging from four to six. TXA was demonstrated to be beneficial in terms of total blood loss by five studies,22,24, 25, 26, 27 drain output by five studies,22, 23, 24, 25,27 change in Hb by six studies,22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 and transfusion requirements by two studies.22,26 However, these earlier meta-analyses inappropriately pooled the results of RCTs and observational studies, which is methodologically incorrect. This approach has a detrimental influence on the levels of heterogeneity, bias, confounding and the accuracy of assessment of the treatment effect size, hence results may be misleading. We avoided this approach in our review and additionally incorporated studies that had not been included in previous reviews. Previous meta-analyses also acknowledged that their small numbers of patients limited their analysis of the effects of TXA administration on the risk of VTE complications. With the addition of new evidence, we have increased power to demonstrate that TXA administration does not increase the risk of VTE events, and this is in keeping with the results of a recent meta-analysis which showed that TXA administration did not increase the risk of VTE complications in patients undergoing total hip and knee arthroplasty.21

As the incidence of TSR continues to increase, it is important to utilise cost-effective treatments such as TXA as part of wider blood management and outcome optimisation strategies. This should, in turn, reduce the need for allogenic blood transfusion, and therefore reduce the risk of associated peri-operative morbidity and mortality6, 7, 8, 9 to patients undergoing this procedure, albeit this association is yet to be investigated in the literature for patients undergoing TSR. This need to control blood loss and minimise blood transfusions is of particular importance in procedures such as TSR where alternative strategies, such as the application of a tourniquet proximal to the operation site, cannot be used.

The current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines in the United Kingdom (UK) in June 2020 advocate utilising intravenous TXA in adults undergoing primary THR and TKR, but only that it should be “considered” in patients undergoing primary TSR.42 They also recommend that all patients undergoing THR, TKR and TSR receive topical TXA diluted in saline after the final wound washout before wound closure (assuming the patient does not suffer from renal impairment), and that the total combined intravenous and topical dose should not exceed three grams. The rationale provided explains that there is good evidence for combined TXA treatments in patients undergoing TKR and THR, but not in patients undergoing TSR.

Of note, our literature search did yield one small RCT which compared intravenous TXA versus topical TXA versus combined intravenous and topical TXA administration in patients undergoing reverse TSR, which was published in June 2020.43 We excluded this paper from the meta-analysis on the basis that there was no comparison against a placebo/no treatment group. Nevertheless, this RCT demonstrates no significant differences between all treatment arms in terms of change in Hb, post-operative blood loss (drain output) and transfusion rate, albeit the combined TXA group had the fewest blood transfusions.

Due to the small number of included papers (4 RCTs and 5 RCSs) in our meta-analysis, publication bias could not be adequately assessed. For similar reasons, and because heterogeneity was not substantial in the majority of the pooled comparisons, sub-group analysis was not performed.

This study has several limitations that must be taken into account. First, there was variation in the route of TXA administered (intravenous and topical), the doses of TXA and placebo administered (fixed-dose and weight-based dose) and also the frequency of administration of the doses; therefore, whilst this study can report an overall treatment effect in favour of utilising TXA, we are unable to suggest whether a particular route of administration or dosage is optimal. Second, five out of the nine included studies were observational, which provided us with estimates of associations but not causality. In particular, the observational data increases the risk of confounding and selection bias. However, data from the RCTs generally matched the findings of the RCSs. Third, whilst the overall sample size was large (1151 TSRs), the sample sizes for individual outcome analyses were much smaller due to variation in the reported outcomes and available data in individual studies. Other variables that were not controlled for included variation in post-operative VTE prophylaxis, variation in the duration of participant follow-up and heterogeneity amongst transfusion protocols – all of which may exert influence on the outcomes considered. It is also worth commenting on the absence of published data comparing the administration of TXA in patient undergoing TER to usual care/placebo/no treatment. Our literature search only yielded one small case series28 of ten patients who underwent TER and all were administered TXA. Despite the differences when compared to THR, TKR and TSR, patients undergoing TER remain at risk of bleeding that would be amenable to mitigation through an appropriate dose of TXA – but the effect and safety of this intervention should be adequately researched. If the benefits of TXA in TER are similar to that of THR, TKR and TSR, then it would reduce post-operative bleeding, reduce transfusion requirements and may reduce the need for a tourniquet. Finally, many studies excluded patients with a history of VTE events, therefore the safety profile and efficacy of TXA in these populations remain unclear.

We suggest that future research should focus on the optimal dose, frequency and route of administration of TXA in TSR, given that most of the studies to date have shown variation in practices. Homogenisation of transfusion protocols and follow-up periods would improve our ability to compare complications rates (e.g., VTE events, surgical site infections, periprosthetic joint infections, etc.) and transfusion rates. Further assessment of the treatment effect of TXA in patients undergoing TER is warranted, as outlined above.

5. Conclusions

This contemporary systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of TXA in primary TSR has demonstrated that it is effective at significantly decreasing blood loss and change in Hb when compared to placebo, and that it is associated with lower blood loss and shorter length of stay when compared to no treatment. No significant variation in transfusion requirements or VTE complications were determined by our analysis. Hence, our review demonstrates that TXA is an effective intervention to reduce surgical blood loss without increasing the risk of VTE events in patients undergoing TSR. TXA is an inexpensive and commonly-used medication which has been demonstrated to reduce blood loss in TSR in a similar fashion to that seen in hip and knee replacement. We advocate the administration of TXA in patients undergoing TSR as part of a wider blood management strategy to minimise peri-operative blood loss and blood transfusion requirements. Further research is needed to demonstrate if a similar treatment benefit exists in patients undergoing TER.

Funding

This study was supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Availability of data and material

Data extracted from individual papers are available from the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

RLD, SKK and MRW designed the study. RLD and JRV contributed to data collection analysis, and interpretation. RLD wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors interpreted data, drafted, and reviewed the final manuscript. All authors approved the submitted manuscript.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of competing interest

AWB and MRW disclose financial activities, all outside the submitted work. All authors have completed uniform disclosure forms.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2021.03.003.

Contributor Information

Richard L. Donovan, Email: richard.donovan@bristol.ac.uk.

Jonny R. Varma, Email: jonny.varma@doctors.org.uk.

Michael R. Whitehouse, Email: michael.whitehouse@bristol.ac.uk.

Ashley W. Blom, Email: ashley.blom@bristol.ac.uk.

Setor K. Kunutsor, Email: setor.kunutsor@bristol.ac.uk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.National Joint Registry (NJR) NJR Reports: details for primary shoulder procedures. 2020. https://reports.njrcentre.org.uk/shoulders-primary-procedures-activity/S03v1NJR?reportid=8D575389-18D0-4FD8-A73B-A8900E393481&defaults=DC__Reporting_Period__Date_Range=%22MAX%22,J__Filter__Calendar_Year=%22MAX%22 H__Filter__Joint=%22Shoulder%22.

- 2.National Joint Registry (NJR) NJR Reports: details for primary elbow procedures. 2020. https://reports.njrcentre.org.uk/elbows-primary-procedures-activity/E03v1NJR?reportid=8D575389-18D0-4FD8-A73B-A8900E393481&defaults=DC__Reporting_Period__Date_Range=%22MAX%22,J__Filter__Calendar_Year=%22MAX%22 H__Filter__Joint=%22Elbow%22.

- 3.National joint registry (NJR). 17th annual report 2020 (report No.: 2054-183x) 2020. https://reports.njrcentre.org.uk/Portals/0/PDFdownloads/NJR%2017th%20Annual%20Report%202020.pdf [PubMed]

- 4.Ryan D.J., Yoshihara H., Yoneoka D., Zuckerman J.D. Blood transfusion in primary total shoulder arthroplasty: incidence, trends, and risk factors in the United States from 2000 to 2009. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(5):760–765. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardy J.C., Hung M., Snow B.J. Blood transfusion associated with shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(2):233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hart A., Khalil J.A., Carli A., Huk O., Zukor D., Antoniou J. Blood transfusion in primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. Incidence, risk factors, and thirty-day complication rates. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):1945–1951. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frisch N.B., Wessell N.M., Charters M.A., Yu S., Jeffries J.J., Silverton C.D. Predictors and complications of blood transfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(9 Suppl):189–192. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman R., Homering M., Holberg G., Berkowitz S.D. Allogeneic blood transfusions and postoperative infections after total hip or knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(4):272–278. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bierbaum B.E., Callaghan J.J., Galante J.O., Rubash H.E., Tooms R.E., Welch R.B. An analysis of blood management in patients having a total hip or knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(1):2–10. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yue C., Kang P., Yang P., Xie J., Pei F. Topical application of tranexamic acid in primary total hip arthroplasty: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(12):2452–2456. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poeran J., Rasul R., Suzuki S. Tranexamic acid use and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty in the United States: retrospective analysis of effectiveness and safety. BMJ. 2014;349 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panteli M., Papakostidis C., Dahabreh Z., Giannoudis P.V. Topical tranexamic acid in total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee. 2013;20(5):300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin J.G., Cassatt K.B., Kincaid-Cinnamon K.A., Westendorf D.S., Garton A.S., Lemke J.H. Topical administration of tranexamic acid in primary total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):889–894. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karam J.A., Bloomfield M.R., DiIorio T.M., Irizarry A.M., Sharkey P.F. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid for reducing blood loss in bilateral total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(3):501–503. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang F., Wu D., Ma G., Yin Z., Wang Q. The use of tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss and transfusion in major orthopedic surgery: a meta-analysis. J Surg Res. 2014;186(1):318–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Georgiadis A.G., Muh S.J., Silverton C.D., Weir R.M., Laker M.W. A prospective double-blind placebo controlled trial of topical tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 Suppl):78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang C.H., Chang Y., Chen D.W., Ueng S.W., Lee M.S. Topical tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and transfusion rates associated with primary total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(5):1552–1557. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3446-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCormack P.L. Tranexamic acid: a review of its use in the treatment of hyperfibrinolysis. Drugs. 2012;72(5):585–617. doi: 10.2165/11209070-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunn C.J., Goa K.L. Tranexamic acid: a review of its use in surgery and other indications. Drugs. 1999;57(6):1005–1032. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199957060-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunutsor S.K., Barrett M.C., Whitehouse M.R., Blom A.W. Venous thromboembolism following 672,495 primary total shoulder and elbow replacements: meta-analyses of incidence, temporal trends and potential risk factors. Thromb Res. 2020;189:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fillingham Y.A., Ramkumar D.B., Jevsevar D.S. The safety of tranexamic acid in total joint arthroplasty: a direct meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(10):3070–30782 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuo L.T., Hsu W.H., Chi C.C., Yoo J.C. Tranexamic acid in total shoulder arthroplasty and reverse shoulder arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2018;19(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-1972-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirsch J.M., Bedi A., Horner N. Tranexamic acid in shoulder arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JBJS Rev. 2017;5(9):e3. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.17.00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu B.F., Yang G.J., Li Q., Liu L.L. Tranexamic acid decreases blood loss in shoulder arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltim) 2017;96(33) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007762. e7762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Box H.N., Tisano B.S., Khazzam M. Tranexamic acid administration for anatomic and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JSES Open Access. 2018;2(1):28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jses.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun C.X., Zhang L., Mi L.D., Du G.Y., Sun X.G., He S.W. Efficiency and safety of tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss in total shoulder arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltim) 2017;96(22) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007015. e7015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He J., Wang X.E., Yuan G.H., Zhang L.H. The efficacy of tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss in total shoulder arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltim) 2017;96(37) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007880. e7880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mannan S., Ali M., Mazur L., Chin M., Fadulelmola A. The use of tranexamic acid in total elbow replacement to reduce post-operative wound infection. J Bone Jt Infect. 2018;3(2):104–107. doi: 10.7150/jbji.25610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z., Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterne J.A.C., Savovic J., Page M.J. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sterne J.A., Hernan M.A., Reeves B.C. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hozo S.P., Djulbegovic B., Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abildgaard J.T., McLemore R., Hattrup S.J. Tranexamic acid decreases blood loss in total shoulder arthroplasty and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(10):1643–1648. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belay E.S., O'Donnell J., Flamant E., Hinton Z., Klifto C.S., Anakwenze O. Intravenous tranexamic acid versus topical thrombin in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;30(2):312–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Budge M. Topical and intravenous tranexamic acid are equivalent in decreasing blood loss in total shoulder arthroplasty. JSEA. 2019;3:1–5. doi: 10.1177/2471549218821181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cvetanovich G.L., Fillingham Y.A., O'Brien M. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss after primary shoulder arthroplasty: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective, randomized controlled trial. JSES Open Access. 2018;2(1):23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jses.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedman R.J., Gordon E., Butler R.B., Mock L., Dumas B. Tranexamic acid decreases blood loss after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(4):614–618. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gillespie R., Shishani Y., Joseph S., Streit J.J., Gobezie R. Neer Award 2015: a randomized, prospective evaluation on the effectiveness of tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(11):1679–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim S.H., Jung W.I., Kim Y.J., Hwang D.H., Choi Y.E. Effect of tranexamic acid on hematologic values and blood loss in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. BioMed Res Int. 2017;9590803 doi: 10.1155/2017/9590803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pauzenberger L., Domej M.A., Heuberer P.R. The effect of intravenous tranexamic acid on blood loss and early post-operative pain in total shoulder arthroplasty. Bone Joint Lett J. 2017;99-B(8):1073–1079. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.99B8.BJJ-2016-1205.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vara A.D., Koueiter D.M., Pinkas D.E., Gowda A., Wiater B.P., Wiater J.M. Intravenous tranexamic acid reduces total blood loss in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a prospective, double-blinded, randomized, controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(8):1383–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Joint replacement (primary): hip, knee and shoulder. 2020. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng157 [PubMed]

- 43.Yoon J.Y., Park J.H., Kim Y.S., Shin S.J., Yoo J.C., Oh J.H. Effect of tranexamic acid on blood loss after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty according to the administration method: a prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29(6):1087–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data extracted from individual papers are available from the corresponding author.