Abstract

A 56-year-old female with a history of poor dental hygiene and aortic insufficiency status post aortic valve replacement in 2015 presented with chest pain and fevers. She was found to have portal vein thrombosis, colitis, and infective endocarditis with aortic valve thickening. Blood cultures were positive for Actinomyces odontolyticus and Gemella morbillorum. Transesophageal echocardiogram was positive for aortic root thickening. Patient was treated with ceftriaxone and apixaban with full recovery.

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiogram

Keywords: Case report, Infective endocarditis, Actinomyces odontolyticus, Gemella morbillorum, Oral pathogens, Echocardiogram

Introduction

Pathogenesis from oral flora involved surface adhesion components including adhesins, lipoteichoic acid, and complex polysaccharides [1]. Bacterial organisms adhere to mammalian platelets, proteins, and epithelial cells [1]. Most common valves that are affected are mitral (37 %) and aortic (41 %) valves [2].

Gemella morbillorum is a facultative anaerobic gram-positive bacterium [3]. The organism is a part of the normal flora of the oropharynx, gastrointestinal tract, upper respiratory tract, and genitourinary system [3]. Cardiac valves can be affected and has been implicated in cases of infective endocarditis [4,5].

Actinomyces species are facultative anerobic gram-positive bacilli [6]. The organism is found in similar locations as Gemella morbillorum [7]. Cases of bloodstream infection in immunocompromised hosts have been reported by Actinomyces odontolyticus [8]. Cases of pericardial effusions and endocarditis have been reported with Actinomyces species [7], however, there are no reports of infective endocarditis by Actinomyces odontolyticus. Co-infection with Gemella morbillorum and Actinomyces odontolyticus causing infective endocarditis presenting as colitis has not been reported previously in the literature.

Case report

Patient was a 56 y/o female with a past medical history of emphysematous bullae of lung post right upper lobectomy, aortic insufficiency with Bentall procedure for valve replacement in 2015 (no dental clearance before the procedure), hypertension, and poor dentition with multiple cavities and 5 remaining teeth (3 central incisors, and 2 molars). She presented to the emergency department with one week of fevers, chills, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, associated with epigastric pain that radiated towards her back and involved her chest. She had not been to a dentist in several years prior to this. She denied dizziness, lightheadedness, shortness of breath with exertion, lower extremity swelling, chest palpitations, or orthopnea.

Admission vitals included a fever to 103 degrees Fahrenheit, a heart rate of 102 beats per minute, blood pressure of 100/71 mmHg, respiratory rate of 18 breathes per minute, and oxygen saturation to 99 % on room air. Physical exam was notable for multiple missing teeth and cavities, a normal S1 and S2, a III/VI systolic murmur was appreciated at the left upper sternal border, and epigastric and left lower quadrant tenderness was palpated.

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast was notable for colitis involving the transverse and descending colon. The right portal vein had thrombosis present. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 104 mL/hr (ref range under or equal to 26 mm per hour). The c-reactive protein was 11.36 mg/dL (ref range 0 to 0.4 milligram per deciliter). White blood cell count was elevated at 18.5 k (ref range 3.8–10.5 K/microliter) with immature granulocyte of 4.4 % (ref range 0–1.5 %). Two sets of aerobic and anaerobic cultures were obtained 30 min apart at 2 different venipuncture sites. Chlorhexidine was used to obtain sterile collections. Patient was started on ceftriaxone and metronidazole for colitis and heparin drip for portal vein thrombosis. Gastrointestinal stool polymerase chain reaction of stool was negative on day 2 for gastrointestinal pathogens.

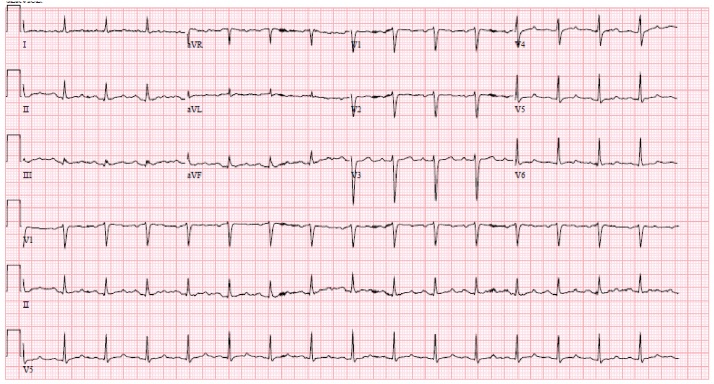

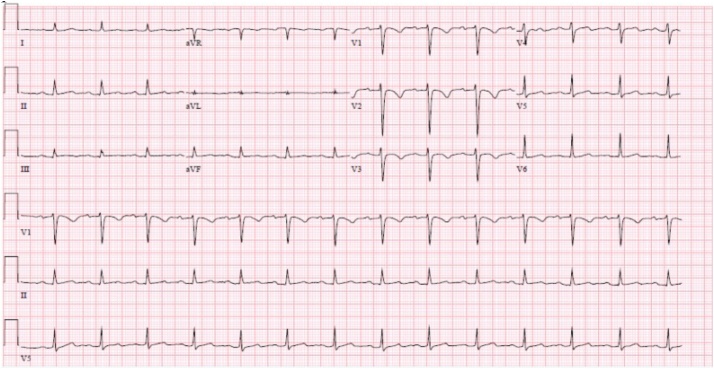

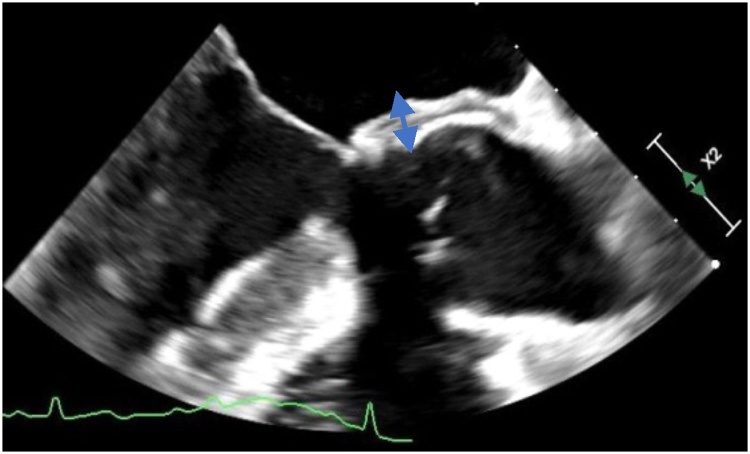

On day 3, anaerobic blood cultures were positive for Actinomyces odontolyticus and Gemella morbillorum. Both pathogens were sensitive to ceftriaxone. Two grams intravenous every 24 h was initiated. Electrocardiogram was notable for PR interval of 208 on day 3, from a baseline of 184 on day 1 (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). Inverted t waves were noted in leads v1, v2, and v3 (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). Aortic root wall thickening of 6.4 mm was noted as well (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Initial ECG on admission, showing PR interval 184 and no inverted deep T waves present.

Fig. 2.

ECG 3 days into admission, showing PR interval 208, and t wave inversions in leads v1-v3.

Fig. 3.

Transesophageal echocardiogram showing aortic root wall thickening of 6.4 mm.

Patient met 2 major Duke’s criteria with aortic root wall thickening, and positive blood cultures. Dental and cardiothoracic surgery evaluation were requested at the time; however, the patient refused as she only wanted antibiotic treatment. Peripheral inserted central catheter was placed. Ceftriaxone 2 g every 24 h was initiated for a 6-week duration. Heparin drip was transitioned to apixaban 5 mg twice a day on discharge. Patient was scheduled for follow-up with dental outpatient for teeth extraction. Patient had resolution of abdominal and chest pain, fevers, and leukocytosis after treatment.

Discussion

Modified Duke’s criteria aid in helping diagnose infective endocarditis. Two major, 1 major and 3 minor, or 5 minor criteria are needed [9]. Major criteria include needing positive blood cultures of organisms that cause infective endocarditis, or echocardiographic findings suggestive of endocarditis [9]. Minor criteria include fever >100.4 degrees Fahrenheit, predisposing cardiac conditions or intravenous drug use, vascular phenomena, immunologic phenomena, or microbiologic evidence of positive blood cultures that does not meet major criteria or serologic evidence of infective endocarditis [9].

Post aortic valve replacement, some aortic wall thickening is expected. However, this should decrease in 3 months. Our patient had valve surgery 5 years prior to arriving at the hospital. A study by Fagman et al. analyzed 303 patients with prosthetic aortic valve replacement. 43 of these patients had prosthetic valve endocarditis, with wall thickness greater than 5 mm 3 months post replacement being highly specific [10]. Poor dentition can be a predisposing risk factor for endocarditis, especially in this population [11]. The decision to discharge based on apixaban for portal vein thrombosis was based on recent studies that direct oral anticoagulants are efficacious for treatment of portal vein thrombosis by Priyanka et al. [12].

Our case report highlights the importance of recognizing oral health in diagnosing and treating endocarditis. Our case is the first to describe endocarditis by Actinomyces odontolyticus, and with co-infection by Gemella morbillorum. By recognizing endocarditis earlier on in its course, mortality can be reduced.

Funding

No sources of funding were obtained for this report.

Ethical approval

Written and verbal consent was obtained from the patient. All information is anonymous.

Consent

Written and verbal consent was obtained by the patient for this report.

Author contribution

K.P. DO: Was part of the primary internal medicine team to help care for the patient. Drafting of the manuscript-Helped with initial draft of the manuscript. Did an extensive literature search regarding the topic.

M.M. MD: Was part of the infectious disease team to help care for the patient. Drafting of the manuscript-Helped with analyzing images used in this manuscript. Also helped to make edits to the paper.

H.H. MD: Was part of the internal medicine team to care for the patient. Drafting of the manuscript-Helped with literature review on the topic and making edits to the paper.

E.C. MD: Was involved with the internal medicine team to help care for the patient. Critical revision of the manuscript-Helped make grammatical corrections. Helped with analyzing the echocardiogram images. Helped review EKG imaging as well.

P.F. MD Was involved in patient care through the cardiology department. Drafting of the manuscript-Helped with extensive analysis of the images and in obtaining and interpreting them. He had a large contribution to this case report.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Department of Medicine at Lenox Hill Hospital.

References

- 1.Knox K.W. The role of oral bacteria in the pathogenesis of infective endocarditis. J Aust Dent. 1991;2:38–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1991.tb00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baddour L.M., Wilson W.R., Bayer A.S., Fowler V.G., Jr, Tleyjeh, Rybak M.J. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132:1435–1486. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kofteridis D., Anastasopoulos T., Panagiotakis S., Kontopodis E., Samonis G. Endocarditis caused by Gemella morbillorum resistant to beta-lactams and aminoglycosides. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38:1125–1127. doi: 10.1080/00365540600740538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Hujailan G., Lagacé-Wiens P. Mechanical valve endocarditis caused by Gemella morbillorum. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:1689–1691. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolhari V., Kumar V., Agrawal N., Prakash S. Gemella morbillorum endocarditis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a rare organism causing a large vegetation and abscess in an uncommon setting. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014(bcr2014203951) doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-203951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valour F., Sénéchal A., Dupieux C., Karsenty J., Lustig S., Breton Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:183–197. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S39601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Litwin K., Jadbabaie F., Villanueva M. Case of pleuropericardial disease caused by Actinomyces odontolyticus that resulted in cardiac tamponade. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;29:219–220. doi: 10.1086/520169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiand D., Barlow G. The rising tide of bloodstream infections with Actinomyces species: bimicrobial infection with Actinomyces odontolyticus and Escherichia coli in an intravenous drug user. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2014;(9):156–158. doi: 10.1093/omcr/omu059. 2014, Published 2014 Dec 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Topan A., Carstina D., Slavcovici A., Rancea R., Capalneanu R., Lupse M. Assesment of the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis after twenty-years. An analysis of 241 cases. Clujul Med. 2015;88:321. doi: 10.15386/cjmed-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fagman E., Bech-H, Flinck A., Lamm C., Svensson G. Increased aortic wall thickness on CT as a sign of prosthetic valve endocarditis. Acta radiol. 2016;57(12):1476–1482. doi: 10.1177/0284185116628336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parahitiyawa N., Jin L., Leung W.k., Yam W., Samaranayake L. Microbiology of odontogenic bacteremia: beyond endocarditis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:46–64. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00028-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Priyanka P., Kupec J., Krafft M., Shah N., Reynolds G. Newer oral anticoagulants in the treatment of acute portal vein thrombosis in patients with and without cirrhosis. Int J Hepatol. 2018;2018(8432781) doi: 10.1155/2018/8432781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]