Abstract

Resistance to anti-androgen therapy in prostate cancer (PCa) is often driven by genetic and epigenetic aberrations in the androgen receptor (AR) and coregulators that maintain androgen signaling activity. We show that specific small RNAs downregulate expression of multiple essential and androgen receptor-coregulatory genes, leading to potent androgen signaling inhibition and PCa cell death. Expression of different short hairpin/small interfering RNAs (sh-/siRNAs) designed to target TMEFF2 preferentially reduce viability of PCa but not benign cells, and growth of murine xenografts. Surprisingly, this effect is independent of TMEFF2 expression. Transcriptomic and sh/siRNA seed sequence studies indicate that expression of these toxic shRNAs lead to downregulation of androgen receptor-coregulatory and essential genes through mRNA 3′ UTR sequence complementarity to the seed sequence of the toxic shRNAs. These findings reveal a form of the “death induced by survival gene elimination” mechanism in PCa cells that mainly targets AR signaling, and that we have termed androgen network death induced by survival gene elimination (AN-DISE). Our data suggest that AN-DISE may be a novel therapeutic strategy for PCa.

Keywords: Prostate Cancer, DISE, RNA-interference, androgen signaling inhibition

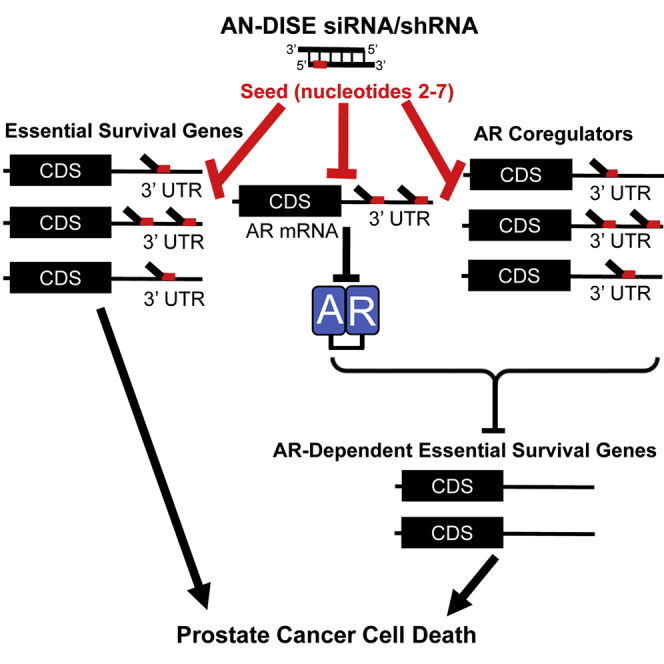

Graphical abstract

Development of effective therapies against advanced prostate cancer (PCa) remains a critical clinical need. We describe a mechanism, AN-DISE, that inhibits the essential androgen receptor signaling pathway, promoting PCa cell death. Through RNA interference of multiple targets simultaneously, AN-DISE could function as a therapeutic approach unlikely to develop resistance.

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most commonly diagnosed non-cutaneous malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in men in the United States.1 Androgen signaling is essential for normal prostate development and PCa cell growth and survival.2, 3, 4, 5 This dependency is exploited in PCa treatment with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and targeted androgen receptor (AR) inhibitors.2 While these therapeutic modalities are initially beneficial, the majority of patients eventually relapse with a resistant and lethal form of the disease called castration-resistant PCa (CRPC).6 In most cases, CRPC cells retain AR expression and remain dependent on its activity for growth and survival, and adaptations, such as increased AR coregulator expression, AR amplification, and/or mutation and constitutively active AR splice variants that lack the ligand binding domain, allow PCa cells to thrive in the androgen depleted environment.6,7 Second generation AR inhibitors and/or regimes that block adrenal androgen biosynthesis are often used to treat CRPC; however, the responses are short lived, leading to secondary resistance.8

A novel mechanism, death induced by survival gene elimination (DISE), has recently been described as a potential cancer therapy.9,10 DISE kills cancer cells through an RNA interference (RNAi) mechanism. In DISE, small interfering or short hairpin RNAs (si- or shRNAs) derived from CD95 (FAS) and FASLG or other human genes, function essentially as microRNAs (miRNAs) to simultaneously target the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) and silence the expression of numerous essential genes, leading to cell death.9 DISE results in activation of multiple cell death pathways, which thwarts the development of resistance and is preferentially toxic to transformed cells, including cancer stem cells.9,11,12 Experiments with ovarian cancer orthotopic mouse models showed that DISE can be induced in vivo to kill cancer cells without evidence of off-site toxicity.13

In this study, we demonstrate that expression of certain shRNAs/siRNAs developed to target TMEFF2, an androgen regulated tumor suppressor gene with restricted expression to brain and prostate, promotes cancer cell death similar to DISE, independently of TMEFF2 targeting/expression. In PCa cells, these toxic shRNAs/siRNAs downregulate the AR and AR coregulatory genes, an effect that correlates with the presence of short seed matches in their 3′ UTRs and which results in global androgen signaling inhibition and cell death. We have termed this mechanism in PCa cells androgen network DISE (AN-DISE). Both androgen-dependent (AD) and CRPC cells are sensitive to AN-DISE, but different shRNAs/siRNAs distinctly affect the viability of each of those types of cells, demonstrating a degree of specificity. In addition, cancer cells that do not depend on AR signaling for growth are less sensitive to the TMEFF2-derived toxic shRNAs than AR signaling-dependent cells further supporting that targeting of AR signaling is an important and distinct component of this mechanism. In vivo, these toxic shRNAs significantly inhibit growth of CRPC 22Rv1 xenografts. These results suggest that AN-DISE may provide a potential therapeutic strategy for advanced PCa by simultaneously targeting the AR, multiple AR coregulators and, in essence, multiple essential pathways, making the development of resistance unlikely.

Results

TMEFF2-targeted shRNAs reduce cell viability and growth of PCa cells

We have previously reported a tumor suppressor function for TMEFF2 in PCa, with low TMEFF2 levels correlating with reduced disease-free survival.14, 15, 16 To study the consequences of the loss of TMEFF2 expression in PCa, TMEFF2 was silenced in several PCa cell lines. Expression of five individual shRNAs to TMEFF2 (shTMEFF2-2, shTMEFF2-3, shTMEFF2-4, shTMEFF2-8, and shTMEFF2-9) spanning the length of the TMEFF2 transcript decreased TMEFF2 expression (Figure S1A). Surprisingly expression of these shRNAs reduced growth and viability of PCa-derived AD (LNCaP), castration-resistant (22Rv1), and AR– (DU145) cell lines when compared with the same cell lines expressing a shScramble control. shTMEFF2 also decreased growth and viability of other transformed cell lines, HEK293T-LX (Figures 1A and 1B) and Panc-1 (data not shown), and viability of melanoma SH-4 cells (Figure S1B). Importantly, these last three cell lines and DU145 do not express TMEFF2, indicating that the effect on cell growth/viability is independent of shRNA-mediated silencing of TMEFF2.

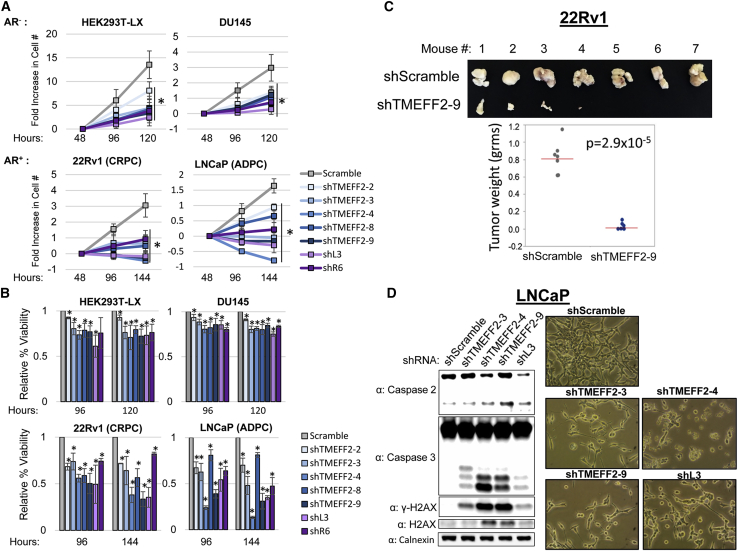

Figure 1.

TMEFF2-targeted and DISE-inducing shRNAs reduce the growth and viability of transformed cells

(A and B) Cell growth (A) and viability (B) of HEK293T-LX, DU145, 22Rv1, and LNCaP cells transduced with plasmids expressing TMEFF2-targeted shRNAs (shTMEFF2-2, -3, -4, -8, -9), FASLG and CD95 targeted shRNAs (shL3, shR6) or shScramble control. Cell growth is presented by fold increase in cell number relative to cell number at 48 h after transductions. Viability was determined by trypan blue and is presented as percent viability relative to shScramble. N = 4, error bars ± SD, ∗p < 0.05 determined by t test. (C) Pictures of tumors (top panel) and dehydrated tumor weight (bottom panel) of xenograft tumors formed by 22Rv1 cells expressing Dox-inducible shScramble and shTMEFF2-9 shRNAs. Mice were sacrificed and tumors were excised after 4 to 5 weeks of tumor growth. n= 7, significance was determined by t test for the means indicated by red bar. (D) Western blot analysis (left panel) showing caspase-2 cleavage, caspase-3 cleavage, γ-H2AX, and H2AX protein expression in lysates obtained from LNCaP cells expressing shTMEFF2-3, shTMEFF2-4, shTMEFF2-9, shL3, or shScramble control shRNA 96 h after transduction. Pictures of cells (right panel) were taken 96 h after transduction. Calnexin was used as a loading control.

In order to confirm that the effect on PCa cell viability is independent of TMEFF2 silencing, we used CRISPR-Cas9 with two independent doxycycline (Dox)-inducible single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs), to knock down TMEFF2 expression in LNCaP cells. CRISPR-Cas9 knockdown of TMEFF2 (LNCaP-Cas9/sgTMEFF2) had no effect on cell viability as compared to the sgGFP control-guide-expressing cells (LNCaP-Cas9/sgGFP; Figures S2A and S2B). However, expression of shTMEFF2-3, -4, or -9 in Dox-induced LNCaP-Cas9/sgGFP or /sgTMEFF2 cells resulted in comparable loss in viability and increase in caspase-3 cleavage when compared to the corresponding cell lines expressing the shScramble control (Figures S2C and S2D). This result confirmed that loss in PCa cell viability was not the result of TMEFF2 silencing, but of a mechanism dependent on expression of these TMEFF2-targeted shRNAs.

We then examined the effect of shRNA targeting TMEFF2 on the growth of subcutaneous tumors in mice. To this end, we established a Dox responsive system using a lentiviral vector to express either shTMEFF2-9 or the shScramble in 22Rv1 (CRPC) cells. In cell culture, 5 days of Dox treatment was sufficient to knock down TMEFF2 protein and induce caspase-3 cleavage in shTMEFF2-9 expressing 22Rv1 cells compared to shScramble-expressing cells (Figure S3). For in vivo experiments, these two cell lines were grown in the absence of Dox to prevent cell death, mixed with 50% basement membrane extract, and inoculated subcutaneously into opposite flanks of NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid II2rgtm1 Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice that were pre-fed (2 days) and kept in a Dox-containing diet for the duration of the experiment. Tumors were palpable/measurable in 100% of the mice 3 weeks after the injection with shScramble control cells but not in those mice injected with shTMEFF2-9-expressing cells. Mice were sacrificed ≈5 weeks after injections, and tumors, if present, were dissected and weighted. Expression of shTMEFF2-9 reduced or blocked tumor growth in this murine model (Figure 1C). Of note, the tumors that formed from shTMEFF2-9 expressing cells did not exhibit lower TMEFF2 protein levels compared to mouse-matched shScramble expressing tumors, as determined by immunohistochemistry (IHC; data not shown), suggesting that shTMEFF2-9 shRNA expression and/or activity may have been lost in these tumors.

The above results are reminiscent of DISE, a small RNAi-mediated mechanism that preferentially kills cancer cells by targeting the 3′ UTRs of multiple survival genes through a mechanism similar to miRNAs. In fact, known DISE-inducing shRNAs (shL3-targeting FASLG or shR6-targeting CD95)9 also reduced growth and viability of all the tested cell lines similar to the effect of shRNAs to TMEFF2 (Figures 1A, 1B, and S1B). Moreover, similar to DISE, expression of shRNA to TMEFF2 (1) induced DNA damage and cell death, as measured by histone H2AX phosphorylation and caspase-2/3 cleavage (Figure 1D); (2) promoted a phenotypic change that resulted in elongated, senescence-like enlarged cells (Figure 1D); and (3) preferentially affect viability of cancer cells, as observed by the attenuated effect on RWPE1, a normal prostate epithelial cell line (Figure S4).

TMEFF2-targeted shRNAs reduce AR expression and inhibit androgen response independently of TMEFF2 levels

As most PCa cells are critically dependent on AR signaling for growth, we hypothesized that these shRNAs targeting TMEFF2 could also be targeting the AR and AR signaling in PCa cells. Using western blot analysis, we found that expression of nine independent shRNAs (shTMEFF2-1–shTMEFF2-9) in LNCaP cells decreased TMEFF2 protein expression and resulted in reductions of AR and androgen-responsive proteins prostate specific antigen (PSA) and FKBP5 particularly when grown in the presence of the AR ligand, dihydrotestosterone (DHT; Figure 2A). Dose-dependence experiments in LNCaP cells with shTMEFF2-3 demonstrated comparable reduction in TMEFF2 and PSA protein levels even at low concentrations of the shRNA, with respect to the cells expressing the shScramble control (Figure S5). These results demonstrate that reduction in PSA level is not due to stress response or a consequence of high shRNA expression. Reductions in the level of androgen-responsive proteins were also evident in C4-2B (CRPC) and 22Rv1 (CRPC) cells when TMEFF2-targeted shRNAs were expressed (Figures 2B and S6), suggesting that the inhibition of androgen signaling by TMEFF2-targeted shRNAs in PCa cells is not a cell-line-specific effect.

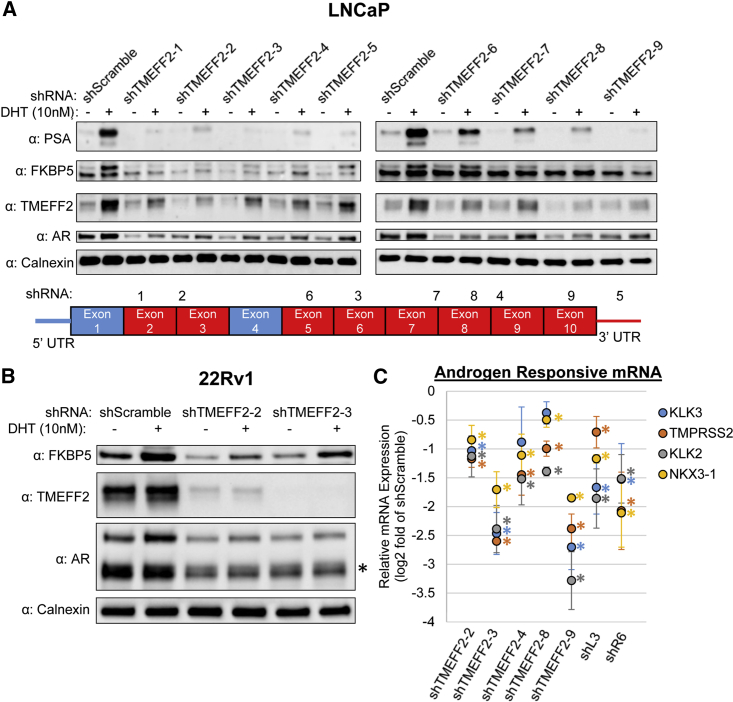

Figure 2.

TMEFF2-targeted and DISE-inducing shRNAs inhibit androgen signaling in prostate cancer cells

(A) Western blot analysis showing protein levels of TMEFF2 (target gene), AR, and two androgen-responsive proteins, PSA and FKBP5, in lysates from LNCaP cells expressing each of nine independent TMEFF2-targeted shRNAs or shScramble control and grown in the presence and absence of 10 nM DHT. Calnexin was used as a loading control. The schematics in the lower panel indicate the exons targeted (red) or not targeted (blue) by the shRNAs and the numbers corresponding to the shRNA names. (B) Western blot analyses showing TMEFF2, FKBP5, and AR (top band is full-length AR, bottom band is the constitutively active AR-V7 isoform, marked by an asterisk [∗]) protein levels in 22Rv1 cells expressing shTMEFF2-2, shTMEFF2-3, or shScramble control, and grown in the presence and absence of 10 nM DHT. Calnexin was used as loading control. (C) messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of androgen-responsive genes, KLK3, TMPRSS2, KLK2, and NKX3-1 in LNCaP cells expressing TMEFF2-targeted shRNAs, shL3, or shR6 relative to cells expressing shScramble control. RNA was extracted 72 h after transductions, and mRNA expression was determined by qRT-PCR. n = 3, error bars ± standard deviation (SD), ∗p < 0.05 determined by t test.

We confirmed that the effect of shTMEFF2 RNAs on the levels of AR and androgen-responsive proteins was independent of TMEFF2 levels by analyzing those proteins in lysates from Dox-induced LNCaP-Cas9/sgGFP or /sgTMEFF2-1 cells that were subsequently transduced with plasmids expressing shTMEFF2-3 or shScramble. Western blot analysis indicated that AR, FKBP5, and PSA levels were similar in knockdown TMEFF2 cells (CAS9-sgTMEFF2-1) and in control cells (Cas9 sgGFP) expressing shScramble. Expression of shTMEFF2-3 drastically reduced AR, FKBP5, and PSA protein levels in both cell lines to a similar degree (Figure S7A). Similarly, TMEFF2 knockdown in LNCaP cells using pooled antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) did not alter PSA or AR protein levels despite reducing TMEFF2 levels as compared to cells transfected with the non-target control ASO (Figure S7B). These data indicate that the effect of the TMEFF2-targeted shRNAs on androgen signaling was independent of their effect on TMEFF2 levels. In addition, deep RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) of the TMEFF2 locus indicated that no RNA originating from this locus could be a target of all nine TMEFF2 shRNAs, except for the main protein coding TMEFF2 isoform 1 mRNA (ENSEMBL ID ENST00000272771.9). Therefore, the TMEFF2 targeted shRNAs were not targeting a non-coding RNA that could be responsible for the phenotypes observed on androgen signaling and viability (Table S1).

Finally, we also demonstrated that expression of shTMEFF2 in LNCaP cells reduced the mRNA expression of AR target genes (KLK3, KLK2, TMPRSS2, and NKX3-1) to varying degrees and, in most cases, the AR mRNA levels (Figures 2C and S8A). Interestingly, while DISE-inducing shL3 also reduced the mRNA levels of some AR signaling targets, it did not affect AR mRNA or protein levels (Figures 2C, S8A, and S8B), suggesting that androgen signaling inhibition was unlikely to be a sole consequence of reducing AR levels. Dose-response experiments in which LNCaP cells were infected with increasing concentrations of lentivirus expressing shTMEFF2-3, -9, or shL3 allowed uncoupling the reduction of AR expression from AR-signaling inhibition. Infections at low titers with shTMEFF2-3, -9, or shL3 expressing viral particles, resulted in downregulation of AR-signaling targets with respect to the shScramble control-virus-infected cells, while the AR levels remained the same. At higher viral titers, AR levels were also reduced (Figure S9). This result further supports that AR-signaling inhibition by these shRNAs can be independent from their effect on AR expression levels.

TMEFF2 shRNAs reduce AR coregulatory and essential gene expression and inhibit global androgen response in LNCaP cells

The results above indicated that the effects on AR signaling and cell viability were completely independent of the presence or targeting of TMEFF2. To further understand the effect of shRNA to TMEFF2 on androgen signaling, we conducted RNA-seq with RNA from LNCaP cells transduced with shTMEFF2-3, -4, -9, or shScramble control shRNA and analyzed gene-expression changes. In addition, we used the toxic DISE-inducing shL3. For these experiments, RNA was extracted 55 h after transduction with the shRNAs to circumvent potential changes in AR target levels secondary to loss of viability, which we observed only 72 h after transduction (Figure S10). In fact, reductions in AR, KLK3, and TMPRSS2 mRNAs were evident at 48 h, indicating that inhibition of androgen signaling is not a consequence of shRNA toxicity.

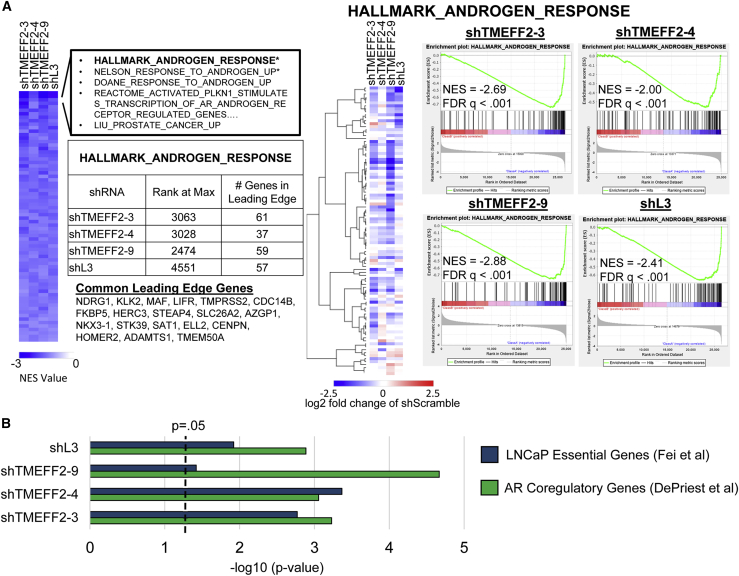

Genes that exhibited ±0.5 log2 fold change and q value < 0.05 in samples from target shRNA-expressing cells relative to shScramble control were considered to be significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Pairwise comparisons of DEGs for the four shRNAs indicated a highly significant overlap (Figures S11A and S11B), suggesting that the transcriptomic changes induced by the shRNAs were similar. Gene set enrichment analyses (GSEAs)17,18 identified 72, out of 19,695 tested Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) gene sets, that had significant differential expression (q value < 0.25) in response to all four shRNAs (Figure 3A; Table S2). All 72 of these common gene sets were downregulated by each of the shRNAs, and the most highly significant (q value < 0.05) were Hallmark Androgen Response and Nelson Response to Androgen Up (Figure 3A; Table S2). Importantly, 19 of the 100 Hallmark Androgen Response genes, including many prominent AR targets such as TMPRSS2, KLK2, NKX3-1, and FKBP5, were located in the leading edge of the GSEA enrichment plots for all four shRNAs, demonstrating a strong overlap among the most significantly downregulated androgen-responsive genes (Figure 3A). All together, these results indicate that all four shRNAs, including shL3, significantly affect global androgen signaling.

Figure 3.

TMEFF2-targeted shRNAs and shL3 inhibit androgen transcriptional response and downregulate AR coregulatory and essential genes

(A) Heatmap (left panel) shows normalized enrichment scores (NES) of common significantly enriched gene sets (q value < 0.25, for each shRNA) from gene set enrichment analyses (GSEAs) of RNA-seq data from LNCaP cells expressing designated shRNAs, compared to cells expressing the shScramble control. Negative NES indicates gene sets are enriched among downregulated genes relative to shScramble control cells. Heatmap (middle panel) shows relative gene expression of genes within the hallmark androgen response gene set. GSEA enrichment plots (right panel) show enrichment of the Hallmark Androgen Response gene set within gene lists rank ordered by gene expression (upregulated to downregulated) in cells expressing designated shRNAs relative to shScramble control cells. NES and p value are labeled on each plot. The number of Hallmark Androgen Response genes within the leading edge for each shRNA is indicated in the table, and the 19 genes located in the leading edge for all shRNAs are listed. (B) –log10 p value for enrichment of AR coregulatory genes19 and LNCaP essential genes20 among significantly downregulated genes by each shRNA, relative to shScramble expressing LNCaP cells. –log10 p values are based on hypergeometric distribution.

Our results demonstrating that DISE-inducing shL3 affects androgen signaling without reducing AR levels (Figures 2C and S8), and those from a dose-response experiment with shTMEFF2-3, -9 and shL3 demonstrating that downregulation of AR can be uncoupled from downregulation of its targets (Figure S9), indicate that androgen signaling inhibition by toxic shRNAs is not just the consequence of reducing AR levels. Critical to AR-mediated signaling is the recruitment of AR coregulators, which modulate its transcriptional response. We therefore examined the effect of the three TMEFF2 and the FASLG targeted shRNAs on AR-coregulatory gene expression and determined that an AR-coregulatory gene set (n = 274)19 was significantly enriched among genes downregulated by each of the 4 shRNAs (Figure 3B). Moreover, since cell viability was also affected in non-PCa cell lines (HEK293-LX and SH-4), which are not dependent on AR signaling, we analyzed the effect of these 4 shRNAs on expression of essential genes. An essential gene set published for LNCaP cells20 was significantly enriched among genes downregulated by each of the 4 shRNAs (Figure 3B). Finally, we observed that multiple histone genes were significantly downregulated by each shRNA (Figure S12), consistent with previous reports on the transcriptomic effects of DISE.9

To confirm the TMEFF2 shRNA-mediated influence on the androgen regulated transcriptome, RNA-seq was conducted with RNA extracted from shScramble and shTMEFF2-3 expressing LNCaP cells grown in the presence or absence of 10 nM DHT. RNA-seq analyses revealed that global androgen transcriptional response was nearly completely abolished in LNCaP cells by the expression of shTMEFF2-3 (13 DEGs in the presence versus absence of DHT) compared to the shScramble (1,423 DEGs in the presence versus absence of DHT; Figure S13A). GSEAs of MsigDB gene sets revealed that a large number of gene sets significantly modulated (up or down) by DHT in shScramble cells were regulated in the opposite direction by shTMEFF2-3 (Figure S14A; Tables S3 and S4). Strikingly, the normalized enrichment score (NES) values of these gene sets oppositely regulated by DHT and shTMEFF2-3 are significantly negatively correlated. The correlation was higher in the presence of DHT (R2 = 0.6477 and R2 = 0.1101 for and up- and downregulated sets) than in its absence (R2 = 0.2697 and R2 = 0.0045 for up- and downregulated sets; Figure S14B).

As expected, due to the AD nature of LNCaP cells, the essential gene set was significantly enriched among genes upregulated by DHT in shScramble-expressing cells (Figure S13B). However, essential and AR-coregulatory gene sets were significantly enriched among genes downregulated by shTMEFF2-3 in the presence and absence of DHT (Figure S13B). Together, these data suggest that inhibition of androgen response is a major contribution to the TMEFF2 shRNA-mediated transcriptomic alterations. We have termed this mechanism in which DISE is triggered by global inhibition of androgen signaling, AN-DISE.

Analysis of AN-DISE in LNCaP AR-knockout (KO) cells21 indicated that toxic shRNA expression (shTMEFF2-3, -4, -9 or shL3) decreased viability of these cells, although to a lesser extent than of parental LNCaP cells, and the effect on viability correlated with caspase-3 activation as observed by western blot analysis (Figures S15A and S15B). This suggests that cells that depend on AR-signaling for survival are more susceptible to AN-DISE than cells that are not (viability of LNCaP versus LNCaP AR-KO cells), a conclusion supported by results indicating that expression of toxic shRNAs have a greater effect on viability and growth of AR+ 22Rv1 and LNCaP cell lines than on the AR null HEK293T and DU145 cell lines (Figures 1A and 1B). These results reinforce the concept that AR-signaling inhibition is an essential component of AN-DISE.

Downregulation of AR coregulatory and essential genes is associated with 3′ UTR sequence complementarity to the toxic shRNA seed sequences

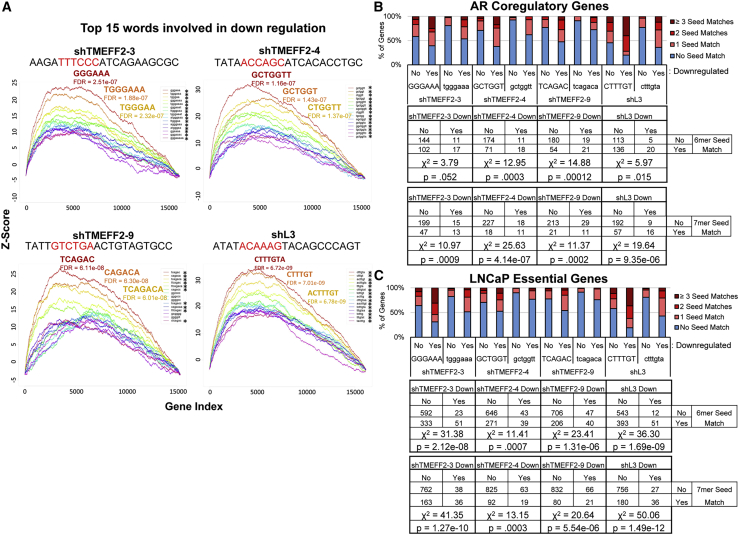

A key element of the DISE mechanism is RNAi seed-mediated targeting of RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to the 3′ UTR of essential genes, resulting in transcript downregulation. To begin understanding whether seed sequences are important in AN-DISE, we utilized the cWords software22 to identify sequences enriched in the 3′ UTRs of downregulated mRNAs (from RNA-seq data) in cells transduced with shTMEFF2-3, -4, -9, or shL3, and then determined whether the enriched sequences were complementary to the seed sequence from the mature guide strand of the different shRNAs. cWords assesses over-representation of nucleotide words in fold-change expression ranked ordered gene lists, correlating differential expression and motif occurrence.22 For each of the shRNAs, the most significantly enriched 6–8 nucleotide sequences in the 3′ UTR of downregulated genes were complementary to potential seeds and surrounding nucleotides on the guide strand (Figures 4A, S16, S17, S18 and S19). Sequences within coding regions complementary to shRNA seeds exhibited a weak association with gene downregulation (Figures S16, S17, andS19). Furthermore, in each case, the most significantly enriched 6-mer sequence was complementary to the seed sequence of the shRNA guide strand that would be produced with a Dicer cut after nucleotide +3 during shRNA processing. This corresponds with a highly predicted Dicer cut site.9 In silico data from a previously published seed sequence toxicity screen23 indicates the toxicity of these seeds. In fact, using this data, 7 out of 9 TMEFF2 targeted shRNAs were found to contain 6-mer seeds within the 50th percentile for reduced viability out of all 4,096 possible 6-mer seeds (Figure S20).

Figure 4.

AR coregulatory and essential gene downregulation is associated with 6-mer and 7-mer 3′ UTR sequences complementary to potential shRNA seed sequences

(A) cWords enrichment plots showing the top 15 enriched 6-mer, 7-mer, and 8-mer in the 3′ UTR of genes downregulated by designated shRNAs according to RNA-seq analyses. y axis shows Z score enrichment values. x axis contains rank ordered genes from the most downregulated to upregulated expression. The top 3 enriched 3′ UTR sequences and FDR values are labeled (red, most enriched; orange, second most enriched; yellow, third most enriched). Unprocessed shRNA guide strand sequences are above each plot, and the potential 6-mer seed sequence complementary to the most enriched 6-mer 3′ UTR sequence associated with gene downregulation is in red. An asterisk (∗) indicates enriched sequences that are complementary to potential shRNA seed motifs. (B and C) AR coregulatory19 (B) and LNCaP essential gene20 (C) sets stratified by downregulation (yes or no) and by the presence in their 3′ UTR of single, 2, or more, 6-mer (upper case) or 7-mer (lower case) sequences identified by cWords analyses. Contingency tables are located below each stacked bar graph. p values were calculated by chi square test of independence and are shown at the bottom of each contingency table.

Our analysis with cWords also identified endogenous miRNAs that share similar seed motifs with each shRNA, and miRNA Database (miRDB, http://mirdb.org/) predicted target gene sets for these miRNAs were also significantly downregulated by the TMEFF2 or L3 shRNAs containing the corresponding similar seed (Figure S21). Interestingly, the seed sequence identified for shTMEFF2-4 is identical to the seed sequence of miR-634, which has been shown to induce apoptosis in cell lines of multiple cancer types,24, 25, 26 including PCa cell lines, and to reduce AR protein levels and viability in PCa cells.27 These results suggest an association between shRNA seed complementarity and gene-expression downregulation.

We next tested the association between shRNA seed complementarity and downregulation of known AR coregulatory19 and essential genes20 in the RNA-seq data for each of the shRNAs (shTMEFF2-3, -4, -9 and L3). For all four shRNAs, 6-mer and 7-mer seed complementarity in the 3′ UTR was significantly associated with AR coregulatory and essential gene downregulation (Figures 4B and 4C). Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) experiments were also used to validate some of these results (Figure S22). A list of AR coregulators with seed matches to each of the shRNAs (shTMEFF2-3, -4, -9 or shL3) is presented in Table S5. A similar analysis was conducted for the list of essential genes using RNA-seq data from LNCaP cells expressing shTMEFF2-3 and shScramble grown in the presence and absence of DHT. Since a significant number of androgen-induced essential genes were downregulated by shTMEFF2-3, we stratified the essential genes based on whether they are androgen induced (n = 66) or not (n = 933). In this case, the association with 3′ UTR complementarity was significant only for the non-androgen-induced group (Figure S23) Moreover, no significant association was observed between AR signaling regulated genes (essential or no) downregulated by shTMEFF2-3 in the presence of DHT (n = 338) and 3′ UTR seed sequence complementarity (Figure S24). These results suggest that a large number of androgen-induced essential genes were downregulated indirectly by shTMEFF2-3 seed-mediated AR coregulatory gene downregulation and androgen signaling inhibition (of note, 21 out of the 274 known coregulators have 3′ UTR matches to the shTMEFF2-3 6-mer seed and are downregulated in the presence and/or absence of DHT). In support of this hypothesis, shTMEFF2-3 expression in LNCaP AR-KO cells promoted downregulation of seed containing targets (TMEFF2, AR-coregulators, essential genes), but not of essential AR-responsive genes that lack seed match sequences (Figure S25).

AN-DISE mediated effects on AR coregulatory gene downregulation, androgen signaling inhibition, and PCa cell viability are seed mediated

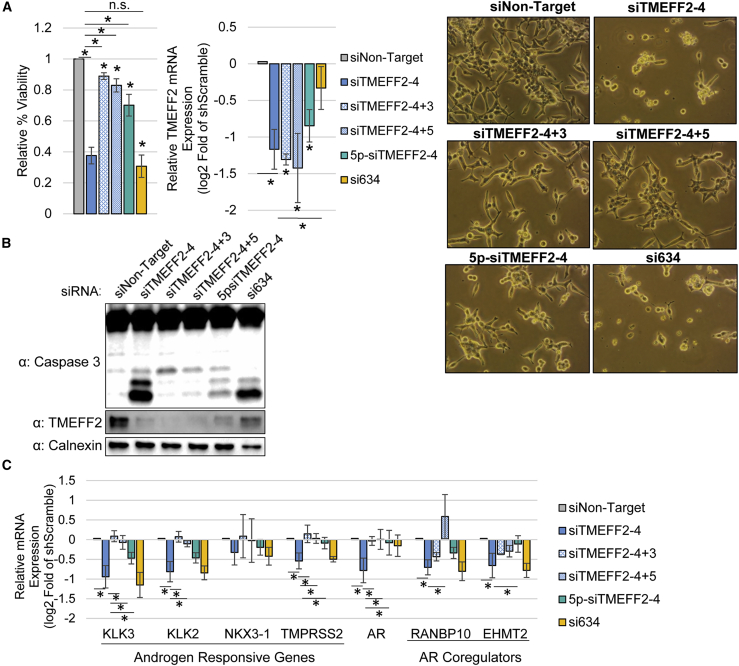

To further define the relevance of the seed sequence in the AN-DISE phenotype, we used toxic siRNAs (siTMEFF2-3, siTMEFF2-4, and siTMEFF2-9) that had matching mature guide strands, and therefore seed sequences, to shTMEFF2-3, shTMEFF2-4, and shTMEFF2-9, and measured their effect on androgen signaling and cell viability when transfected in LNCaP cells. In addition, we designed several controls as follows: (1) the same siRNAs carrying 5′ ON-TARGET-Plus modifications (Dharmacon, GE Healthcare), which block seed-mediated off-target effects (5p-siTMEFF2); (2) siTMEFF2-4+3 and siTMEFF2-4+5 siRNAs that have a shifted siTMEFF2-4 target sequence by 3 nucleotides and 5 nucleotides, respectively, and therefore, while still fully complementary to TMEFF2, they have a different seed sequence than siTMEFF2-4; and (3) a miR-634 siRNA mimic (si634), which contained the same seed sequence as siTMEFF2-4 independent of the full TMEFF2 target sequence. All three TMEFF2-targeted siRNAs (siTMEFF2-3, -4, -9) significantly reduced LNCaP viability when compared to the siNon-target control, while transfection of the ON-TARGET-Plus modified TMEFF2-targeted siRNAs had a much-reduced effect on viability (Figures 5A and S26). Shifting the siTMEFF2-4 target sequence (siTMEFF2-4+3 and shTMEFF2-4+5) had a weaker effect on viability (Figure 5A). Importantly, si634 exerted similar toxicity to its non-modified “seed homolog” siTMEFF2-4 without significantly reducing TMEFF2 expression (Figure 5A). The effect on viability of the different siRNAs correlated with caspase-3 cleavage, but not with their ability to silence TMEFF2 expression (Figures 5A, 5B, S26, and S27). These results indicate that AN-DISE toxicity in PCa cells is dependent on the seed-mediated targeting mechanism of the siRNAs, leading to cell death. These experiments also confirm that the observed toxicity is not due to an interferon-like mechanism or TMEFF2 silencing. qRT-PCR analysis of the AR, AR-responsive, and AR-coregulatory genes, in cells transfected with each of the siRNAs listed above showed that those siRNAs that more greatly affect viability, also more potently downregulate expression of those targets (Figures 5C and S28). These data indicate that AR coregulatory gene downregulation, androgen signaling inhibition, and loss in PCa cell viability are correlated and RNAi seed mediated.

Figure 5.

AR coregulatory gene downregulation and decrease in PCa cancer cell viability are shRNA seed mediated

(A) Relative percent viability and TMEFF2 mRNA expression in LNCaP cells transfected with siTMEFF2-4 and control siRNAs (siNon-target; negative seed controls: siTMEFF2-4+3, siTMEFF2-4+5, 5p-siTMEFF2-4; positive seed control: si634). 5p designates an ON-TARGET-Plus modification (Dharmacon) that reduces off-target effects by reducing miRNA-like gene downregulation. Cell viability was determined by trypan blue. mRNA expression was determined by qRT-PCR. Viability measurements, cell pictures, and RNA extractions were done 72 h after siRNA transfections N = 4, error bars ± SD, ∗p < 0.05 compared to siNon-target. Bars with an asterisk (∗) designate significant differences (p < 0.05) relative to siTMEFF2-4. Significance was determined by t test. (B) Western blot analysis showing caspase-3 cleavage and TMEFF2 protein expression in lysates from LNCaP cells transfected with the designated siRNAs. Lysates were obtained 72 h after siRNA transfections. Calnexin was used as loading control. (C) Relative androgen responsive, AR coregulator, and AR mRNA expression in LNCaP cells transfected with siTMEFF2-4 and control siRNAs. RNA was extracted 72 h after siRNA transfections. mRNA expression was determined by qRT-PCR. n= 4, error bars ± SD, ∗p < 0.05 determined by t test.

In agreement with previous reports that DISE11 is a mechanism that is preferentially active in cancer cells, transfection of Cyanine 5 (Cy5) labeled siTMEFF2-4 and siTMEFF2-9 in normal prostate epithelial cell lines did not affect viability when compared to the non-target control. However, these siRNAs significantly reduce viability of the LNCaP, C4-2B, and 22Rv1 PCa cell lines (Figure S29).

In summary, the data presented in this study suggest that certain RNAi seed sequences can induce AN-DISE, a form of DISE that primarily targets AR-signaling. In AN-DISE essential and AR coregulatory genes are downregulated through an RNAi seed-mediated mechanism, leading to potent androgen signaling inhibition, downregulation of androgen regulated survival pathways, and PCa cell death.

Discussion

Therapeutic resistance to ADT in PCa remains a major hurdle in treatment.6,7 Various molecular mechanisms underlie the persistent activity of the AR in CRPC cells growing in an androgen-depleted environment, including AR mutations and splice variants, and the overexpression of AR coregulators.6 Furthermore, the AR cistrome and transcriptional program undergoes changes that increase oncogenicity during the progression to CRPC,28,29 and multiple AR coregulators may play significant roles in this process.29, 30, 31 However, identifying individual essential coregulators that can be effectively targeted in the clinical setting has proved difficult.

In this study, we show that RNAi can be used in PCa cells to target and downregulate multiple AR coregulatory and essential gene networks, through a miRNA-like mechanism, resulting in androgen signaling inhibition and PCa cell death. Since androgen signaling inhibition via the seed-mediated downregulation of AR coregulators plays a central role in the cell death mechanism, and RNAi-induced transcriptomic changes show profound effects on androgen regulated genes, we term this RNAi mechanism, which resembles DISE,9,10 AN-DISE. We independently demonstrate that certain shRNAs previously shown to induce DISE in other cancer cell types (i.e., shL3) can induce AN-DISE in PCa cells. Similarly, some toxic RNAi molecules described in this manuscript that trigger AN-DISE in AR+ PCa cells can also reduce cell growth/viability of cells that are not AR signaling dependent (DU145, HEK293T-LX, SH-4, and LNCaP-AR-KO). While this indicates that both mechanisms (DISE and AN-DISE) are essentially the same, it is worth noting the following distinctions specific to AN-DISE as it relates to affecting cancer cells that are dependent on AR-signaling for survival: (1) toxic RNAs in PCa cells preferentially target the AR signaling pathway; (2) many essential genes in PCa cells, while not necessarily specific for these cells, are AR signaling regulated in PCa cells and therefore downregulated by AN-DISE; and (3) most of the AR-signaling regulated essential genes shown to be downregulated by AN-DISE do not contain seed matches to the toxic shRNA, and therefore they are not direct targets of the toxic shRNA. However, AR-coregulators are enriched in AN-DISE downregulated genes and significantly associated with the presence of seed matches in the 3′ UTR. This suggests that it is the downregulation of the AR-coregulators that inhibits AR-signaling and leads to downregulation of AR-signaling targets. The centrality of androgen-regulated survival genes in PCa and their relationship to survival gene pathways in cells lacking the AR raise the possibility of an evolutionary relationship between the development of cell survival networks and hormonal signaling.

The interpretation of loss-of-function experiments using RNAi is often clouded by the miRNA-like seed-mediated targeting of RISC to the 3′ UTRs of multiple genes, resulting in transcript downregulation and off-target effects.32, 33, 34 In fact, considering potential off-target effects has aided in the interpretation of RNAi screen studies.35, 36, 37 Clinically, the majority of RNAi-based cancer therapies that have entered clinical trials have been designed to target individual genes.38, 39, 40 However, strategies based on the seed-mediated targeting of essential gene networks provide many theoretical advantages, including a reduction in evolutionary avenues for adaptive resistance in cancer cells. This is supported by a recently described DISE mechanism.9,10 DISE works through the RNAi seed-mediated downregulation of numerous essential genes leading to cancer cell death through activation of multiple death pathways9,11 making adaptive resistance much less likely when compared to strategies targeting individual genes. Importantly, preclinical studies have shown that DISE-inducing siRNAs can be delivered to ovarian tumors in mice via nanoparticles and can significantly reduce tumor growth.13

We propose that AN-DISE represents a potential therapeutic strategy that has important theoretical benefits over conventional androgen signaling targeted PCa therapies:

-

(1)

Ability to downregulate multiple AR coregulators. The simultaneous downregulation of multiple AR coregulators with a single therapeutic agent bypasses the necessity for identifying single targetable essential coregulators, which may vary according PCa subtype and tumor cell heterogeneity and may change during PCa progression. In addition, the consequences of functional redundancies of AR coregulators are likely overcome by targeting multiple AR coregulators simultaneously. Interestingly, our data show that different shRNAs display a certain level of specificity with respect to the targeting of distinct AR-coregulatory genes.

-

(2)

Ability to target constitutively active AR isoforms. AN-DISE induces CRPC cell death, and certain seed sequences downregulate AR mRNA and/or protein, including AR-V7, which is associated with increased resistance to ADT and AR inhibitors.41

Of note, since toxic shRNAs that trigger AN-DISE also downregulate multiple essential genes that are independent of the AR signaling axis, the risk of developing AR-independent resistance mechanisms, common to treatment with second generation anti-androgens, is likely reduced.

The presence of DISE-inducing RNAi targeting in certain genes, such as CD95 and FASLG ,9,42 and TMEFF2 (this study), that can have a tumor suppressor role, may point to an endogenous tumor suppressive mechanism in which small RNAs can be processed from certain mRNAs and loaded into RISC, resulting in essential gene downregulation. In support of this hypothesis, a previous report suggests that small RNAs derived from FASLG mRNA can be loaded into RISC and induce an endogenous DISE mechanism in cancer cells.43 Interestingly, secondary structure predictions indicate that FASLG mRNA forms a tightly folded structure with extensive regions of complementarity that could provide the endogenous double-stranded sequences to be processed and loaded into RISC.43 A similar prediction was obtained for the TMEFF2 mRNA (data not shown). This raises questions of whether DISE can be induced endogenously in cancer cells, and whether the endogenous mechanism could be exploited therapeutically without the exogenous delivery of RNAi. Furthermore, if TMEFF2 mRNA can function as a tumor suppressor through this mechanism, then it is possible that both TMEFF2 protein and mRNA function independently as tumor suppressors. We have previously published that low TMEFF2 mRNA expression correlates with decreased disease-free survival in PCa patients.16 Since TMEFF2 expression is induced by the AR,44,45 TMEFF2 mRNA may be part of a negative feedback loop with androgen signaling through AR coregulator downregulation via small TMEFF2-derived RNAs being loaded into RISC. This mechanism could exert pressure on PCa cells to lose TMEFF2 expression during PCa progression. The existence of endogenous DISE and AN-DISE mechanisms warrant further investigation.

In summary, in addition to supporting previous reports describing the DISE mechanism, we describe a form of DISE in PCa cells, AN-DISE. By downregulating multiple essential genes and AR coregulatory genes through an RNAi seed-based mechanism, we propose that AN-DISE represents a potential therapeutic strategy for inhibiting androgen signaling and inducing PCa cell death.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and plasmid constructs

LNCaP (CRL-1740), 22Rv1 (CRL-2505), DU145 (HTB-81), C4-2B (CRL-3315), and RWPE1 (CRL-11609) cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). LentiX-293T cells were obtained from Clontech/Takara Bio (Mountain View, CA, USA). Cells were cultured for no more than 20 passages (less than 15 passages for LNCaP cells) from the validated stocks. Melanoma SH-4 cells were obtained from Dr. R. Janknecht (OUHSC). LNCaP-KO (#4 and #16) cells were obtained from Dr. D. Tang (Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center). BHPre1 and NHPre1 cells were obtained from Dr. S. Hayward (NorthShore Research Institute). BHPre1 and NHPre1 cell lines were subjected to short tandem repeat (STR) DNA profiling by IDEXX BioAnalytics (Columbia, MO, USA) to use as reference database for subsequent analysis. None of these cell lines are on the list of contaminated and misidentified cell lines reported by ICLAC (https://iclac.org/databases/cross-contaminations/). Cells were tested negative for mycoplasma using the Mycosensor PCR assay kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) or the LookOut Mycoplasma PCR detection kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). LNCaP, 22Rv1, and C4-2B cells were maintained in RPMI Glutamax growth media (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). DU145, PC3, SH-4, and LentiX-293T cells were maintained in DMEM growth media (Gibco). Both RPMI and DMEM media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Corning, Corning, NY, USA), 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, Amphotericin B, and 2 mM L-glutamine. RWPE1 cells were maintained in KSF media (Gibco). BHPre1 and NHPre1 cells were maintained in HPrE-conditional medium, as previously described.46 For experiments measuring gene-expression response to DHT, cells grown after transduction with the shRNA were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and treated with 10% charcoal-stripped serum (CSS) containing growth media for 24 h for hormone depletion, followed by 24 h in the same media containing 10 nM DHT (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) or 0.0001% ethanol (EtOH) vehicle.

The plasmid pLKO.1 vector was used for shRNA expression, and plasmids were obtained from Open Biosystems or cloned using pLKO.1-TRC (a gift from Dr. David Root; Addgene #10878; http://addgene.org/10878; RRID: Addgene 10878). For Dox-inducible expression, shRNAs were cloned into Tet-pLKO-Puro (a gift from Dmitri Wiederschain; Addgene plasmid #21915; http://addgene.org/21915; RRID: Addgene_21915). pLKO.1-TRC cloning protocol was obtained from addgene. shTMEFF2-6 and shTMEFF2-9 sequences were generated using the siRNA Wizard online tool by Invitrogen: https://www.invivogen.com/sirnawizard/. All other shRNAs used in this study come from the RNAi consortium shRNA library (https://www.broadinstitute.org/rnai-consortium/rnai-consortium-shrna-library), and The RNAi consortium (TRC) numbers are provided.

shScramble (5′-CCTAAGGTTAAGTCGCCCTCG-3′)

shTMEFF2-1 (5′-CTGGTTATGATGACAGAGAAA-3′) TRCN0000073522

shTMEFF2-2 (5′-CGTCTGTCAGTTCAAGTGCAA-3′) TRCN0000222559

shTMEFF2-3 (5′-GCGCTTCTGATGGGAAATCTT-3′) TRCN0000073521

shTMEFF2-4 (5′-GCAGGTGTGATGCTGGTTATA-3′) TRCN0000073520

shTMEFF2-5 (5′-CCTTGCATTTGTGGTAATCTA-3′) TRCN0000073518

shTMEFF2-6 (5′-GGCTCTGGAGAAACTAGTCAA-3′)

shTMEFF2-7 (5′-ATGCAGAGAATGCTAACAAAT-3′) TRCN0000373776

shTMEFF2-8 (5′-CATACCTTGTCCGGAACATTA-3′) TRCN0000373700

shTMEFF2-9 (5′-GGCACTACAGTTCAGACAATA-3′)

shL3 (5′-ACTGGGCTGTACTTTGTATAT-3′) TRCN0000059000

shR6 (5′-CCTGAAACAGTGGCAATAAAT-3′) TRCN0000038696

CRISPR-Cas9 (pRCCH-CMV-Cas9-2A-Hygro) and Dox-inducible sgRNA (pRSGT16-U6Tet-(sg)-CMV-TetRep-2A-TagRFP-2A-Puro) plasmids were obtained from Cellecta. LentiX 293T cells and CalPhos transfection reagents (Takara Bio) were used for viral particle packaging. psPAX2 and VSV-G plasmids were used for lentiviral packaging. psPAX2 was a gift from Dr. Didier Trono (Addgene plasmid #12260; http://addgene.org/12260; RRID: Addgene_12260), and pCMV-VSV-G was a gift from Dr. Robert Weinberg (Addgene plasmid #8454; http://addgene.org/8454; RRID: Addgene_8454). Viral concentrations necessary for approximately 90% or greater survival (for non-toxic constructs) in selection antibiotic were used for transductions. For lentiviral transductions, cells were seeded in 6 cm plates at 50% confluency, and viral particle containing supernatant was diluted in 1.5 mL 8 μg/mL polybrene serum-free media and added to cells. After 5 h, 1.5 mL of 10% FBS growth media was added to transduction media. Growth media was refreshed 24 h after initial viral particle exposure. When cell lines were stably selected, transduced cells were grown for an average of 10 days using the following selection antibiotic concentrations: Puromycin 1 μg/mL, hygromycin 750 μg/mL.

Cell growth and viability assays

For growth and viability analyses in response to shRNA expression, LNCaP, 22Rv1, DU145, and HEK293T-LX (LentiX-293T, HEK293T subclone) cell lines were transduced with pLKO.1 shRNA constructs. Cells were trypsinized and seeded in 6-well plates 24 h post-transduction at the following concentrations: 1 × 105 cells/well (HEK293T-LX, DU145), 2 × 105 cells/well (LNCaP, 22Rv1). Trypan blue was used to stain the cells to selectively count live cells and assess viability using a Nexcelom Auto T4 Cellometer. Cells were trypsinized and counted using the same method 24, 48, 72 (for DU145, HEK293T-LX), or 96 (for LNCaP, 22Rv1) h after seeding the for initial cell count (48 h). Of note, LNCaP and 22Rv1 have a slower growth rate. Viability was assessed at each time point via trypan blue. Viability of RWPE1, and SH-4 and LNCaP AR-KO, cells transduced with shRNAs was determined 120 and 96 h after transductions, respectively. Relative percent viability was then calculated by dividing percent viability of knockdown cell lines by percent viability in cells expressing the shScramble control.

For viability analyses in response to siRNA, transfections were carried out as described in the siRNA transfections section of the Materials and methods. Cells were trypsinized and split 24 h after transfections, and viability was determined by trypan blue 72 h after transfections.

Statistics: two-tailed t tests were used to calculate significant differences in viability and growth. p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

ASOs transfections

2'-deoxy-2'-fluoro-beta-D-arabinonucleic acid (FANA) ASOs were obtained from AUM Biotech (Philadelphia, PA, USA). LNCaP cells were transfected with 250 nM ASO (non-target or pool of 4 targeting TMEFF2) using 0.19% Dharmafect #3 transfection reagent. 48 h after transfection, cells were treated with 10% CSS RPMI for 24 h, followed by 24 h in 10 nM DHT or 0.0001% EtOH.

siRNA transfections

Custom siRNAs with and without the ON-TARGET-Plus modification to block seed mediated off-target effects were obtained through Dharmacon (Horizon Discovery, Waterbeach, UK). When indicated, custom siRNAs were also ordered with a Cy5 label on the 3′ end of the passenger strand. siRNA guide strand sequences were as follows:

siTMEFF2-3: 5′-AUUUCCCAUCAGAAGCGCAUU-3′

siTMEFF2-4: 5′-AACCAGCAUCACACCUGCAUU-3′

siTMEFF2-4+3: 5′-UAUAACCAGCAUCACACCUUU-3′

siTMEFF2-4+5: 5′-AGUAUAACCAGCAUCACACUU-3′

siTMEFF2-9: 5′-UGUCUGAACUGUAGUGCCCUU-3′

si634: 5′-AACCAGCACCCCAACUUUGUU-3′

Non-target siRNA pool (Dharmacon D-001810-10-05) and Cy5 labeled non-target siRNA (same sequence as D-001810-01-05) were used as negative controls.

Dharmafect siRNA transfection protocol was used for transfections (https://horizondiscovery.com/-/media/Files/Horizon/resources/Protocols/basic-dharmafect-protocol.pdf). Dharmafect reagent #1 (0.2%) was used for RWPE1, BHPre1, and NHPre1 cell lines, and 0.2% Dharmafect reagent #3 was used for LNCaP, C4-2B, and 22Rv1 cell lines. 30 nM siRNA was used for each transfection.

RNA extractions and lysate preparations

RNeasy with on-column DNase treatment (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) was used for RNA extractions. Cell Signaling lysis buffer 9803 was used for whole cell lysates. Cells were maintained in complete media containing 10% FBS for all experiments not using DHT. For experiments measuring gene-expression response to DHT, cells were treated as described in cell culture and plasmid constructs section.

Western blot analysis and antibodies

Proteins were separated via 10% SDS-PAGE using mini-PROTEAN TGX stain free gels (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA), and transferred onto 0.2 μm nitrocellulose membranes using the semi-dry turbo transfer system (Biorad). 1 h incubation in 5% nonfat dry milk (NFDM) in tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) was used for blocking, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with primary antibody diluted in 5% NFDM TBST. Primary antibodies and dilutions used in this study were as follow: anti-TMEFF2 (HPA015587, Sigma Aldrich) 1:1,000, anti-PSA (76113, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), 1:1,000, anti-FKBP5 (2901, Abcam), 1:1,000, anti-AR (D6F11, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), 1:1,000, anti-caspase-3 (9662S, Cell Signaling Technology), 1:1,000, anti-H2AX (2595S, Cell Signaling Technology), 1:1,000, anti-phospho-H2AX Ser139 (9718S, Cell Signaling Technology), 1:1,000, anti-Calnexin (22595, Abcam), 1:4,000. Goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (31460, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) or goat anti-mouse HRP conjugated secondary antibody (sc-2005, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) were diluted in 5% NFDM at a concentration of 80 ng/mL. Clarity Western ECL (Biorad) or SuperSignal West Femto (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for chemiluminescent detection.

qRT-PCR

RNA samples were reverse transcribed using iScript reverse transcription supermix (500 ng/rxn; Biorad). qRT-PCR reactions were carried out in 96-well plates (25 ng cDNA/well and 200 nM per primer/well) using Sso Advanced Universal SYBR Green supermix (Biorad) and the Biorad CFX96 touch RT-PCR detection system. Each reaction (sample/primer set combination) was run in duplicate to ensure accurate loading. Relative gene expression was calculated via ΔΔCT method.47 Four housekeeping genes (RPL8, RPL38, PSMA1, and PPP2CA) were used for normalization per run, with the geometric mean of CT values being used for normalization of gene expression.48 The following primers were used:

TMEFF2: For (5′-AGTGCAACAATGACTATGTGCC-3′), Rev (5′-GATCCTGATCCTGCATCTGTG-3′)

KLK3: For (5′-CTTACCACCTGCACCCGGAG-3′), Rev (5′-TGCAGCACCAATCCACGTCA-3′)

KLK2: For (5′-AGAGGAGTTCTTGCGCCCC-3′), Rev (5′-CCCAGCACACAACATGAACTCT-3′)

TMPRSS2: For (5′-CCTCTGACTTTCAACGACCTAGTG-3′), Rev (5′-TCTTCCCTTTCTCCTCGGTGG-3′)

NKX3-1: For (5′-CAGAGACCGAGCCAGAAAGG-3′), Rev (5′-ACTCGATCACCTGAGTGTGGG-3′)

AR: For (5′-CCAGGGACCATGTTTTGCC-3′), Rev (5′-CGAAGACGACAAGATGGACAA-3′)

EHMT2: For (5′-GGAGCCACCGAGAGAGTTCATG-3′), Rev (5′-ACCAACAGTGACAGTGACAGAGG-3′)

MED1: For (vGGAGAATCCTGTGAGCTGTCCG-3′), Rev (5′-ATCTTGTTCTAAGGATTGGAGAGCC-3′)

MED21: For (5′-GCTAACCCTACAGAAGAGTATGCC-3′), Rev (5′-CCTCGATAAACAACATCCTCCAGAC-3′)

PIAS1: For (5′-GGGTTTCTCTACTATGTCCACTTGG-3′), Rev (5′-TATGGAGCCTTCTTATCACAGACAG-3′)

RANBP9: For (5′-GGGTGCACTACAAAGGTCATGG-3′), Rev (5′-ACCTGGTAGTCTATTCATGTTCACAC-3′)

RANBP10: For (5′-GTAACCAGGAGACCAGCGACAG-3′), Rev (5′-GGACTCATCCGTCTGCAGGTC-3′)

SMARCD1: For (5′-TGCTACTCTAGACAACAAGATCCATG-3′), Rev (5′-GGTTACCCACCACATCAGTCATTG-3′)

TAF1: For (5′-CAGAAAAGCAGGTAACACAGGAAGG-3′), Rev (5′-TCACTTCCACTTTCACTCAGCTGG-3′)

USP12: For (5′-CAAACAGGAAGCACACAAACGGATG-3′), Rev (5′-CAACAAGGTCGTACATTCTGTCTGG-3′)

ZMIZ1: For (5′-CCAGACGCTGATGTGGAGGTC-3′), Rev (5′-GGCTTGTGGGAGGTCTTGTTGTC-3′)

PSMA1: For (5′-CTGCCTGTGTCTCGTCTTGTATC-3′), Rev (5′-GGCCCATATCATCATAACCAGCA-3′)

CDC45: For (5′-CATGACAGCCTGTGCAACAC-3′), Rev (5′-GGGAAGACCCATGTCTGCAA-3′)

TONSL: For (5′-CTGCGTGGTTATTGCACAGGTC-3′), Rev (5′-CAGCACATGCTGGAGGTTCTGAC-3′)

ATAD2: For (5′-CTGTTGACCCTGATGAGGTTCCTG-3′), Rev (5′-GCACAGGCTCTATGCCTAATAAGACG-3′)

RPL8: For (5′-CACCGTTATCTCCCACAACCCT-3′), Rev (5′-AGCCACCACACCAACCACAG-3′)

RPL38: For (5′-ACTTCCTGCTCACAGCCCGA-3′), Rev (5′-TCAGTTCCTTCACTGCCAAACCG-3′)

PPP2CA: For (5′-TTGATCGCCTACAAGAAAGTTCCC-3′), Rev (5′-CATGGCACCAGTTATATCCCTCC-3′)

Statistics: two-tailed t tests were used to calculate significant differential gene expression. n= 3 or 4. p <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RNA-seq

Deep paired-end RNA-seq analysis targeted to the TMEFF2 locus for de novo isoform detection was carried out by Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation’s Sequencing Facility. One sample of LNCaP RNA was used for analysis, and over 317 million reads were obtained after decontamination. The genomic region of focus was the TMEFF2 locus –/+ 1Mbp upstream and downstream (chr2: 190949046–193194933). StringTie (v.1.2.3) was used for transcript reconstruction.

For differential gene expression analyses, two RNA-seq experiments were conducted as follows:

RNA-seq #1: LNCaP cells expressing shScramble, shTMEFF2-3, shTMEFF2-4, shTMEFF2-9 or shL3. RNA was extracted 55 h after transductions.

RNA-seq #2: LNCaP cells expressing shScramble or shTMEFF2-3. Cells were grown in RPMI containing 10% charcoal-stripped FBS (hormone-depleted media) for 24 h beginning at 24 h after transductions. Cells were then grown in RPMI containing 10% charcoal-stripped FBS with the addition of 10 nM DHT or 0.0001% EtOH for 24 h prior to RNA extraction.

In both cases, RNA samples were prepared as described in the RNA extractions and lysate preparations section of the Materials and methods. Three repeats were analyzed for each RNA-seq analysis. RNA-seq and initial statistical analyses were carried out by Novogene. Briefly, RNA integrity was analyzed by Agilent 2100 to ensure sample quality. mRNAs were isolated using polyT magnetic beads, which was followed by fragmentation. Two cDNA libraries were synthesized using random hexamer primers; one with deoxythymidine triphosphate (dTTP) to deoxyuridine triphosphate (dUTP) substitutions in the second strand to allow for strand specificity, and one library without substitution. cDNA fragments from both libraries were ligated to NEBNext Adaptor and purified using AMPure XP beads after PCR amplification. 20 million reads were conducted for each sample using an Illumina Next-Generation sequencer. For quality control purposes, error rate distributions and G/C content were analyzed in reads, and low-quality reads containing adaptor sequences, >10% unknown nucleotides or low Q-score values were eliminated by FastQC (Novogene). STAR was used for mapping clean reads to the human transcriptome and genome, and differential gene expression was determined using the DESeq2 R package. p values were adjusted using the Benjamini and Hochberg method. Transcripts with average log2 fold change >0.5 (n = 3) and adjusted p value <±0.05 were considered significantly differentially expressed. All the data has been deposited in NCBI GEO: GSE165249.

RNA-seq enrichment analyses

For RNA-seq #1, GSEA software version 4.0.1 was used for GSEAs.17,18 The following Molecular Signature Database (MSigDB) collections were used for gene sets: Hallmark (50 gene sets), Curated (5,529 gene sets), Regulatory target (3,735 gene sets), Gene Ontology (GO) (10,192 gene sets), and Oncogenic (189 gene sets; http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp). For each comparison, genes were rank ordered according to fold change, from the most upregulated to most downregulated, relative to shScramble expressing cells, and duplicate genes were eliminated. 1,000 gene permutations were used during enrichment analyses, and false discovery rate (FDR) q values less than 0.25 were considered significant and less than 0.05 were considered highly significant.

For RNA-seq #2, significantly DEGs (log2 fold change > 0.5, adjusted p value < 0.05) were determined in response to DHT for shScramble and shTMEFF2-3-expressing cells (shScramble + DHT versus shScramble – DHT; shTMEFF2-3 + DHT versus shTMEFF2-3 – DHT), and in shTMEFF2-3 relative to shScramble-expressing cells in the presence and absence of DHT (shTMEFF2-3 + DHT versus shScramble + DHT; shTMEFF2-3 – DHT versus shScramble – DHT). GSEAs were conducted as described for RNA-seq #1.

Essential gene list was obtained from Fei et al.20 All of the top 999 essential genes identified in LNCaP cells were used for the essential gene list. In addition, all 274 AR corregulators from DePriest et al.19 were used for AR coregulatory gene list.

p values for enrichment analyses were calculated by hypergeometric distribution:

Where p, p value; N, number of total genes; M, number of genes in pathway/gene list; n, number of differentially expressed genes; and i, number of overlapped genes of M and n.

cWords analyses

The cWords webserver (http://servers.binf.ku.dk/cwords/22) was used to identify 3′ UTR and coding sequence (CDS) gene sequences of 6, 7, and 8 nucleotides in length associated with gene downregulation in RNA-seq analyses. Genes were rank ordered from the most downregulated to upregulated for each comparison, and ensembl release 99 3′ UTR and CDS gene sequences were used.

shRNA seed match analyses

Essential and AR coregulatory gene lists were stratified by downregulation (yes or no), and by the presence of single, two or three, or more 6 and 7 nucleotide 3′ UTR sequences found to be most enriched in downregulated genes according to cWords analyses. Ensembl 99 MANE Select transcript 3′ UTR and/or APPRIS annotated 3′ UTR sequences were used. 3′ UTR sequences were uploaded into R Studio using the seankross/warppipe R package (https://rdrr.io/github/seankross/warppipe/), and 3′ UTR sequence length and sequences with specified 6-mer and 7-mer sequences were identified.

Statistics

Pearson’s Chi-square test of independence was used to identify significant associations between 6-mer and 7-mer 3′ UTR sequences and gene downregulation. p <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Mouse xenografts

Animal studies were approved and conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Oklahoma Health Science Center IACUC (animal protocol #17-053-SSHCILA). Mice were housed in groups of 2 or 3 animals per cage. NSG mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were used for this study. 1.8 × 106 22Rv1 cells stably transduced with Dox-inducible shScramble or shTMEFF2-9 shRNAs and mixed with Basement membrane extract (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) at a 1:1 ratio were injected subcutaneously into the flanks of mice pre-fed for 2 days with chow containing Dox (Bio-Serv, Flemington, NJ, USA). Mice were maintained on the Dox chow diet, and tumor growth was monitored using the Biopticon TumorImager. Mice were sacrificed approximately 5 weeks after injections, tumors were excised and dehydrated, and tumor weights were determined. Differences in shScramble and shTMEFF2-9 tumor weight were analyzed statistically by t test. n= 7.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. D. Tang (Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center), Dr. R. Janknecht (OUHSC), and Dr. S. Hayward (NorthShore Research Institute) for sharing of cell lines. The authors acknowledge Cody Bullock’s help with mycoplasma detection and Dr. R. Pelikan (OMRF) with isoform analysis. This work was supported by the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology (OCAST HR18-037; M.J.R.-E.); the Oklahoma IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence (OK-INBRE; P20 GM103447); and the National Institutes of Health (NIH 5U54GM104938; J.D.W.). Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA225520, COBRE P20GM103639, and the Oklahoma Tobacco Settlement Endowment Trust contract awarded to the University of Oklahoma Stephenson Cancer Center, and used the Tissue Pathology and the Molecular Biology and Cytometry Research Shared Resources. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Oklahoma Tobacco Settlement Endowment Trust.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.C. and M.J.R.-E.; methodology, J.M.C., A.S.A., and M.J.R.-E., validation, J.M.C. and M.J.R.-E.; formal analysis, J.M.C., C.G., J.D.W., C.X., and M.J.R.-E.; investigation, J.M.C., M.J.R.-E., resources, C.G., J.D.W., and C.X.; writing – original draft, J.M.C. and M.J.R.-E.; writing – review & editing, J.M.C., C.G., J.D.W., C.X., A.S.A., and M.J.R.-E. supervision, J.D.W, C.X., and A.S.A.; funding acquisition, J.D.W. and M.J.R.-E.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2021.03.002.

Supplemental information

NESs and q values for GSEA (q value <0.25, for each shRNA) common to LNCaP cells expressing the designated shRNAs compared to cells expressing the shScramble control. q value = 0 : <0.001.

Table showing the top 100 gene sets (based on GSEA NES value) upregulated by DHT treatment in shScramble LNCaP cells. NES and q values are shown for gene set regulation by DHT (shScramble + DHT versus shScramble –DHT) and by shTMEFF2-3 in the presence of DHT (shTMEFF2-3 + DHT versus shScramble + DHT). Positive NES values indicate gene set upregulation. Negative NES values indicate gene set downregulation. q value < 0.25 indicates significantly enriched gene set. q value = 0 : <0.001.

Table showing the top 100 gene sets (based on GSEA NES value) downregulated by DHT treatment in shScramble LNCaP cells. NES and q-values are shown for gene set regulation by DHT (shScramble + DHT versus shScramble –DHT) and by shTMEFF2-3 in the presence of DHT (shTMEFF2-3 + DHT versus shScramble + DHT). Positive NES values indicate gene set upregulation. Negative NES values indicate gene set downregulation. q value < 0.25 indicates significantly enriched gene set.

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davey R.A., Grossmann M. Androgen Receptor Structure, Function and Biology: From Bench to Bedside. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2016;37:3–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang F., Koul H.K. Androgen receptor (AR) cistrome in prostate differentiation and cancer progression. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Urol. 2017;5:18–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie Q., Liu Y., Cai T., Horton C., Stefanson J., Wang Z.A. Dissecting cell-type-specific roles of androgen receptor in prostate homeostasis and regeneration through lineage tracing. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14284. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powers G.L., Marker P.C. Recent advances in prostate development and links to prostatic diseases. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2013;5:243–256. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan X., Cai C., Chen S., Chen S., Yu Z., Balk S.P. Androgen receptor functions in castration-resistant prostate cancer and mechanisms of resistance to new agents targeting the androgen axis. Oncogene. 2014;33:2815–2825. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang Y., Jiang X., Liang X., Jiang G. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of castration resistant prostate cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018;15:6063–6076. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharp A., Welti J., Blagg J., de Bono J.S. Targeting Androgen Receptor Aberrations in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;22:4280–4282. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Putzbach W., Gao Q.Q., Patel M., van Dongen S., Haluck-Kangas A., Sarshad A.A., Bartom E.T., Kim K.A., Scholtens D.M., Hafner M. Many si/shRNAs can kill cancer cells by targeting multiple survival genes through an off-target mechanism. eLife. 2017;6:e29702. doi: 10.7554/eLife.29702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Putzbach W., Gao Q.Q., Patel M., Haluck-Kangas A., Murmann A.E., Peter M.E. DISE: A Seed-Dependent RNAi Off-Target Effect That Kills Cancer Cells. Trends Cancer. 2018;4:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hadji A., Ceppi P., Murmann A.E., Brockway S., Pattanayak A., Bhinder B., Hau A., De Chant S., Parimi V., Kolesza P. Death induced by CD95 or CD95 ligand elimination. Cell Rep. 2014;7:208–222. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ceppi P., Hadji A., Kohlhapp F.J., Pattanayak A., Hau A., Liu X., Liu H., Murmann A.E., Peter M.E. CD95 and CD95L promote and protect cancer stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5238. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murmann A.E., McMahon K.M., Haluck-Kangas A., Ravindran N., Patel M., Law C.Y., Brockway S., Wei J.J., Thaxton C.S., Peter M.E. Induction of DISE in ovarian cancer cells in vivo. Oncotarget. 2017;8:84643–84658. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X., Overcash R., Green T., Hoffman D., Asch A.S., Ruiz-Echevarría M.J. The tumor suppressor activity of the transmembrane protein with epidermal growth factor and two follistatin motifs 2 (TMEFF2) correlates with its ability to modulate sarcosine levels. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:16091–16100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.193805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corbin J.M., Overcash R.F., Wren J.D., Coburn A., Tipton G.J., Ezzell J.A., McNaughton K.K., Fung K.M., Kosanke S.D., Ruiz-Echevarria M.J. Analysis of TMEFF2 allografts and transgenic mouse models reveals roles in prostate regeneration and cancer. Prostate. 2016;76:97–113. doi: 10.1002/pros.23103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Georgescu C., Corbin J.M., Thibivilliers S., Webb Z.D., Zhao Y.D., Koster J., Fung K.M., Asch A.S., Wren J.D., Ruiz-Echevarría M.J.A. A TMEFF2-regulated cell cycle derived gene signature is prognostic of recurrence risk in prostate cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:423. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5592-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mootha V.K., Lindgren C.M., Eriksson K.F., Subramanian A., Sihag S., Lehar J., Puigserver P., Carlsson E., Ridderstråle M., Laurila E. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V.K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B.L., Gillette M.A., Paulovich A., Pomeroy S.L., Golub T.R., Lander E.S., Mesirov J.P. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DePriest A.D., Fiandalo M.V., Schlanger S., Heemers F., Mohler J.L., Liu S., Heemers H.V. Regulators of Androgen Action Resource: a one-stop shop for the comprehensive study of androgen receptor action. Database (Oxford) 2016;2016:bav125. doi: 10.1093/database/bav125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fei T., Chen Y., Xiao T., Li W., Cato L., Zhang P., Cotter M.B., Bowden M., Lis R.T., Zhao S.G. Genome-wide CRISPR screen identifies HNRNPL as a prostate cancer dependency regulating RNA splicing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E5207–E5215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1617467114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Q., Deng Q., Chao H.P., Liu X., Lu Y., Lin K., Liu B., Tang G.W., Zhang D., Tracz A. Linking prostate cancer cell AR heterogeneity to distinct castration and enzalutamide responses. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3600. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06067-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasmussen S.H., Jacobsen A., Krogh A. cWords - systematic microRNA regulatory motif discovery from mRNA expression data. Silence. 2013;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1758-907X-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao Q.Q., Putzbach W.E., Murmann A.E., Chen S., Sarshad A.A., Peter J.M., Bartom E.T., Hafner M., Peter M.E. 6mer seed toxicity in tumor suppressive microRNAs. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4504. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06526-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang C.Z., Cao Y., Fu J., Yun J.P., Zhang M.F. miR-634 exhibits anti-tumor activities toward hepatocellular carcinoma via Rab1A and DHX33. Mol. Oncol. 2016;10:1532–1541. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gokita K., Inoue J., Ishihara H., Kojima K., Inazawa J. Therapeutic Potential of LNP-Mediated Delivery of miR-634 for Cancer Therapy. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2020;19:330–338. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujiwara N., Inoue J., Kawano T., Tanimoto K., Kozaki K., Inazawa J. miR-634 Activates the Mitochondrial Apoptosis Pathway and Enhances Chemotherapy-Induced Cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3890–3901. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Östling P., Leivonen S.K., Aakula A., Kohonen P., Mäkelä R., Hagman Z., Edsjö A., Kangaspeska S., Edgren H., Nicorici D. Systematic analysis of microRNAs targeting the androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1956–1967. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Decker K.F., Zheng D., He Y., Bowman T., Edwards J.R., Jia L. Persistent androgen receptor-mediated transcription in castration-resistant prostate cancer under androgen-deprived conditions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:10765–10779. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Z., Wu D., Thomas-Ahner J.M., Lu C., Zhao P., Zhang Q., Geraghty C., Yan P.S., Hankey W., Sunkel B. Diverse AR-V7 cistromes in castration-resistant prostate cancer are governed by HoxB13. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:6810–6815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718811115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu K., Wu Z.J., Groner A.C., He H.H., Cai C., Lis R.T., Wu X., Stack E.C., Loda M., Liu T. EZH2 oncogenic activity in castration-resistant prostate cancer cells is Polycomb-independent. Science. 2012;338:1465–1469. doi: 10.1126/science.1227604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groner A.C., Cato L., de Tribolet-Hardy J., Bernasocchi T., Janouskova H., Melchers D., Houtman R., Cato A.C.B., Tschopp P., Gu L. TRIM24 Is an Oncogenic Transcriptional Activator in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:846–858. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson A.L., Burchard J., Leake D., Reynolds A., Schelter J., Guo J., Johnson J.M., Lim L., Karpilow J., Nichols K. Position-specific chemical modification of siRNAs reduces “off-target” transcript silencing. RNA. 2006;12:1197–1205. doi: 10.1261/rna.30706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson A.L., Linsley P.S. Recognizing and avoiding siRNA off-target effects for target identification and therapeutic application. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:57–67. doi: 10.1038/nrd3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamola P.J., Nakano Y., Takahashi T., Wilson P.A., Ui-Tei K. The siRNA Non-seed Region and Its Target Sequences Are Auxiliary Determinants of Off-Target Effects. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015;11:e1004656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buehler E., Khan A.A., Marine S., Rajaram M., Bahl A., Burchard J., Ferrer M. siRNA off-target effects in genome-wide screens identify signaling pathway members. Sci. Rep. 2012;2:428. doi: 10.1038/srep00428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sudbery I., Enright A.J., Fraser A.G., Dunham I. Systematic analysis of off-target effects in an RNAi screen reveals microRNAs affecting sensitivity to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:175. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riba A., Emmenlauer M., Chen A., Sigoillot F., Cong F., Dehio C., Jenkins J., Zavolan M. Explicit Modeling of siRNA-Dependent On- and Off-Target Repression Improves the Interpretation of Screening Results. Cell Syst. 2017;4:182–193.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2017.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tabernero J., Shapiro G.I., LoRusso P.M., Cervantes A., Schwartz G.K., Weiss G.J., Paz-Ares L., Cho D.C., Infante J.R., Alsina M. First-in-humans trial of an RNA interference therapeutic targeting VEGF and KSP in cancer patients with liver involvement. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:406–417. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schultheis B., Strumberg D., Santel A., Vank C., Gebhardt F., Keil O., Lange C., Giese K., Kaufmann J., Khan M., Drevs J. First-in-human phase I study of the liposomal RNA interference therapeutic Atu027 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32:4141–4148. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.55.0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis M.E., Zuckerman J.E., Choi C.H., Seligson D., Tolcher A., Alabi C.A., Yen Y., Heidel J.D., Ribas A. Evidence of RNAi in humans from systemically administered siRNA via targeted nanoparticles. Nature. 2010;464:1067–1070. doi: 10.1038/nature08956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antonarakis E.S., Lu C., Wang H., Luber B., Nakazawa M., Roeser J.C., Chen Y., Mohammad T.A., Chen Y., Fedor H.L. AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1028–1038. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel M., Peter M.E. Identification of DISE-inducing shRNAs by monitoring cellular responses. Cell Cycle. 2018;17:506–514. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2017.1383576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Putzbach W., Haluck-Kangas A., Gao Q.Q., Sarshad A.A., Bartom E.T., Stults A., Qadir A.S., Hafner M., Peter M.E. CD95/Fas ligand mRNA is toxic to cells. eLife. 2018;7:e38621. doi: 10.7554/eLife.38621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Overcash R.F., Chappell V.A., Green T., Geyer C.B., Asch A.S., Ruiz-Echevarría M.J. Androgen signaling promotes translation of TMEFF2 in prostate cancer cells via phosphorylation of the α subunit of the translation initiation factor 2. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e55257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gery S., Sawyers C.L., Agus D.B., Said J.W., Koeffler H.P. TMEFF2 is an androgen-regulated gene exhibiting antiproliferative effects in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:4739–4746. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang M., Strand D.W., Fernandez S., He Y., Yi Y., Birbach A., Qiu Q., Schmid J., Tang D.G., Hayward S.W. Functional remodeling of benign human prostatic tissues in vivo by spontaneously immortalized progenitor and intermediate cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:344–356. doi: 10.1002/stem.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vandesompele J., De Preter K., Pattyn F., Poppe B., Van Roy N., De Paepe A., Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. research0034.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

NESs and q values for GSEA (q value <0.25, for each shRNA) common to LNCaP cells expressing the designated shRNAs compared to cells expressing the shScramble control. q value = 0 : <0.001.

Table showing the top 100 gene sets (based on GSEA NES value) upregulated by DHT treatment in shScramble LNCaP cells. NES and q values are shown for gene set regulation by DHT (shScramble + DHT versus shScramble –DHT) and by shTMEFF2-3 in the presence of DHT (shTMEFF2-3 + DHT versus shScramble + DHT). Positive NES values indicate gene set upregulation. Negative NES values indicate gene set downregulation. q value < 0.25 indicates significantly enriched gene set. q value = 0 : <0.001.

Table showing the top 100 gene sets (based on GSEA NES value) downregulated by DHT treatment in shScramble LNCaP cells. NES and q-values are shown for gene set regulation by DHT (shScramble + DHT versus shScramble –DHT) and by shTMEFF2-3 in the presence of DHT (shTMEFF2-3 + DHT versus shScramble + DHT). Positive NES values indicate gene set upregulation. Negative NES values indicate gene set downregulation. q value < 0.25 indicates significantly enriched gene set.