Abstract

Environmental health-related risks are becoming a primary concern in Nigeria, with diverse environmental problems such as air pollution, water pollution, oil spillage, deforestation, desertification, erosion, and flooding (due to inadequate drainage systems) caused mostly by anthropogenic activities. This paper reviews the pre-existing and current environmental health problems, proffer future research and needs, policy needs, and recommendations necessary to mitigate Nigeria's environmental health situation. Data from the Institute of Health Metric and Evaluation on Global Burden of Disease (GBD) was used to ascertain the causes of Death and Disability-adjusted Life Years (DALYs) in Nigeria from 2007-2017 and published literatures where reviewed. According to the world health data report, most of the highest-ranked causes of DALYs in Nigeria are related to environmental risk factors. The lower respiratory infection associated with air pollution has advanced from the 4th in 2007 to the highest ranked cause of death in 2017. Other predominant causes of death associated with environmental risk factors include chronic respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, enteric infections, diarrheal diseases, communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional disease, which has resulted in approximately 800 thousand deaths and 26 million people living with DALYs per annum in Nigeria. Major environmental risk factors include household air pollution, ambient air pollution, water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH), which shows a prolonged but progressive decline. In contrast, ambient particulate matter pollution, ambient ozone pollution, and lead exposure show a steady rise associated with death and DALYs in Nigeria, indicating a significant concern in an environmental health-related risk situation. Sustaining a healthy environment is critical in improving the quality of life and the span of a healthy life. Therefore, environmentally sustainable development policies and practices should be essential to the population and policymakers for a healthy life.

Keywords: Environment, Environmental health, Risk factors, Diseases, Pollution, Disability-adjusted life years

Environment, Environmental Health, Risk Factors, Diseases, Pollution, Disability-adjusted Life Years

1. Introduction

The environment is the total living and non-living surroundings of any organism needed for life and sustainability [1]. The state of the environment per time has a significant impact on the biotic and abiotic components of the environment, thus essential for health and human living. If the environment is not healthy, then everything in the environment is posed at risk [1]. Environmental health is the interconnection between people and their environment by which human health and a balanced, nonpolluted environment are sustained or degraded [2]. Individual, societal, national, and global activities relating to the environment have a complex and dynamic relationship operating simultaneously. Environmental health reciprocates in two ways, which include environmental factors affecting human health and human activities affecting environmental quality.

The environmental, physical, chemical, and biological factors and their related behaviors impact health in one way or another [3]. These could be a two-way interaction of environmental health as a human activity affecting the environment, likewise the conditions of the environment affecting human health [2]. Sustaining a healthy environment is critical in improving the quality of life and a healthy life span.

The World health report indicated that globally, 23 percent of death occurrences and 26 percent of children deaths ranging up to 4 million children under five every year are due to environmental factors [4, 5]. Also, 85 out of 102 categories of diseases and injuries are influenced by environmental factors [6]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the interactions between humans and the environment affect the quality of life, health disparities, and a healthy life span. Making the environment healthier can prevent about 13 million death yearly and avoid 13%–37% of the world's disease burden, such as 40% of deaths from malaria, 41% of deaths from lower respiratory infections, and 94% of deaths from diarrheal disease [2, 6]. Therefore, environmental health involves preventing or controlling disease, disability, and injury associated with interactions between the environment and humans [7] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the Environmental Heath situation in Nigeria.

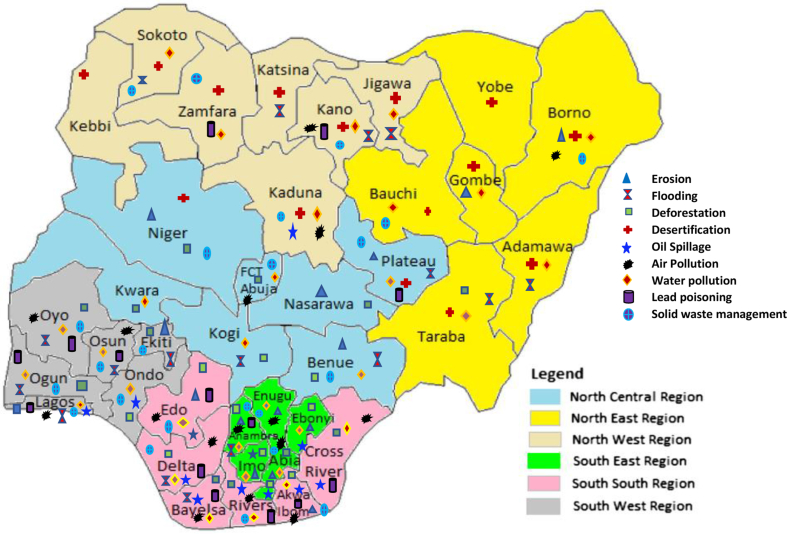

The state of Nigeria's environment recently has been undergoing drastic changes. Nigeria rapidly turning to oil exploration and industrialization has many manufacturing industries, oil refineries, and factories. Also, Nigeria's fast population growth has caused environmental-related problems [8]. Due to a lack of development in rural areas, there is high population migration to urban areas leading to more environmental-related problems [9]. Problems such as air pollution, water pollution, solid waste management, urban poverty, deforestation, desertification, wind erosion, and flooding increase, cause more risk to the environment and the population in highly industrialized cities in Nigeria. Climate change has been evident in almost all parts of Nigeria [10], such as excess flooding in the south-east and north-central region, a decline in rainfall in the Northeastern and southern region, and temperature increase in all regions of the country (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Map of Nigeria showing different locations and environmental problems.

Globally there has been a significant change in the state of the environment. Climate change and the greenhouse effect have been on the rise leading to so many natural disasters such as ice-melting, floods, tsunami, air pollution, the emergence of infectious and non-communicable diseases leading to various health risks humans [11, 12]. There are several health issues in Nigeria as a country, such as control of some disease vectors, maternal mortality, infectious diseases, poor hygiene and sanitation, disease surveillance, and road traffic injuries. Additionally, like many other countries, Nigeria faces environmental health-related problems, including environmental hazards and the insufficiency of basic human necessities. However, the designed programs for addressing health issues in the country have proven inadequate and resulted in a small health status improvement [13].

Therefore, in line with the above background, our main objective is to identify environmental health-related risks by discussing the current status and the future needs within Nigeria between 2007 and 2017. Specifically, we (i) assessed and relayed Nigeria's current environmental health situation. (ii) presented the causes of death and years lost to disability (DALYs), showing levels of contributions from environmental risks (iii) explained how environmental factors affect health, identifying specific diseases associated with environmental risks. (iv) reviewed literatures and discussed extensively environmental problems, their sources, and associated ill-health (v) propose future research and policy needs to mitigate the situation.

2. Study area, datasets, and methods

2.1. Study area

Nigeria is one of the West African countries that borders the Republic of Benin to the West, Cameroon and Chad to the East, and Niger to the North [14]. The coast of Nigeria lies on the Gulf of Guinea to the South, while it borders Lake Chad to the Northeast. The country covers a total of 923,768 km2 (356, 669 sq mi) [15]. The valleys of river Niger and Benue are the most extensive topographical area, with rugged highland to the southwest [16, 17]. It is also found in the tropics, where the climate is very humid and seasonally damp. The country is affected by four types of climates such as tropical monsoon, Sahel, tropical savanna, and Alpine climate. The temperatures can rise to 44 °C (111.2 °F) in some parts, especially at the coast, during dry seasons and ranges 16 °C–25 °C in highland areas with temperate conditions along the Cameroon border [18, 19]. The rainfall ranges between 4000 mm (157.5 in) to 2000 mm (118.1 in) per year in Southern parts and totals 1100 mm (43.3 in) in central Nigeria.

Nigeria's population is about 202 million, and the population density is 221 per km2 (571 people per m2), with about 51.2 percent of the population urbanized, while the median age is 17.9 years [15, 20]. The population growth rate of Nigeria is about 2.62 percent, growing faster compared to other similar-sized countries. However, this growth rate is projected to decrease up to 2.04 percent by the year 2050. Nigeria's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2018 was about $444,92 million, which presents a growth of about 1.9 percent compared to the one of 2017(International Monetary Fund, 2018) [21]. Nigeria agriculture has four components, including crop, livestock, fishing, and forestry [15]. Estimates from reports show that 22.86% of Nigeria's GDP was contributed by agriculture in 2018. The report also estimated that industries contributed 23.18% of the Nigeria GDP, while services contributed to 53.97% in 2018 [18], [22]. However, the Nigerian economy is currently shifting from agriculture to industries such as gas and oil. The primary manufacturing industries include wood, rubber, cement, and textiles among others [23, 24].

2.2. Datasets

The data used was acquired from Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). This study's data range is from 2007 to 2017 of the Global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factor studies (GBD, 2017); the data contains variables of interest, causes of death, and DALYs. Data sources are available online and can be explored in detail at GBD 2017 from the IHME http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool. Data were extracted for Nigeria on all age groups, both sex, environmental risks, and health-related-risk clusters of environmental-risk factors. This study concentrated mainly on related risk clusters diseases and injuries categorized under environmental risk factors such as cardiovascular diseases, diarrheal diseases, mental disorder, enteric infections, respiratory infections, tuberculosis, lower respiratory infections, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic respiratory diseases ischemic heart disease, stroke, communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases.

2.3. Methods

IHME uses three major risk categories to attribute DALYs, Years living with disability (YLDs), and causes of deaths, which are; (i) environmental and occupational risks, (ii) behavioral risks, and (iii) metabolic risks. The different related risks are clustered into these three significant categories. Details of criteria used in assessing risk factors and how it is calculated are explained in details elsewhere [25, 26, 27, 28, 29]. DALYs are calculated as the sum of Years of Life Lost (YLLs) and Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) [30]. GBD calculates these impacts for a country using epidemiological studies, mathematical functions, country's exposure estimates, and data of underlying rates of diseases and deaths that are adjusted to the database of Gridded population of the world (GPW); more details of the methodology can be found in https://www.stateofglobalair.org/resources.

After the acquisition of the data, we performed statistical analysis using excel and python statistical tools similar to previous studies [26, 30, 31] because of python's ability to analyze a large volume of data and create interactive plots, charts, and graphics at a rapid pace [32]. With these tools, we represented environmental risk factors graphically; air pollution, household air pollution from solid fuels, ambient particulate matter pollution, ambient ozone pollution, lead exposure and unsafe water, sanitation, and handwashing versus all causes of death and DALYs. Lastly, we justified our results by reviewing published papers to ascertain the environmental problems, their sources, and the status of environmental health situations in Nigeria.

3. Health patterns in Nigeria

In this section, Nigeria's health pattern will be discussed while presenting the causes of death and DALYs and showing the contribution levels from environmental risk. Environmental health has proven to be a dynamic and continually evolving situation globally. Nigeria, the same as other countries in the world, is experiencing emerging challenges in environmental health. Some of the common emerging environmental health issues in Nigeria include climate change, which influences infectious disease patterns, air quality, and the severity of natural hazards such as droughts, storms, and floods (WHO). Hazardous wastes and toxic substances are yet to be fully recognized, and research to appreciate how these risk factors impact health is underway [33]; however, reducing such risk factors continues in Nigeria and other parts of the world [13]. The majority of Nigeria's populations spend the most time at work, school, or home environments. Some of these environments expose them to indoor pollution, structural issues, electric and fire hazards, lead-based paint hazards, and inadequate sanitation and heating [21]. These environmental hazards have impacted the health and safety of the population. Therefore, there is a need for maintaining excellent healthy homes and societies to achieve a sustainable environmental health system [34].

In the scope of Nigeria's demography, this study seeks to analyze and take an overarching analysis of the factors affecting the quality of health; the quality health as mention anchors on environmental activities that causes death and DALYs. Graphical representation of the top 10 risk factors contributing to most death and disability combined in Nigeria is shown in Figure 3, and Table 1 shows the top 10 causes of death. Figure 4 shows the cause of deaths due to different air pollution, and Figure 5 shows the cause of DALYs due to various air pollution. Causes of death and DALYs due to WaSH and lead exposure is shown in Figure 6, and Figure 7 shows the number of death due to other environmental risks from 2007-2017.

Figure 3.

Top 10 risk factors contributing to most death and disability combined in Nigeria 2007–2017(IHME, 2018) (Note: Red box indicating environmental risk factors).

Table 1.

Top 10 causes of most deaths in Nigeria from 2007-2017 (IHME, 2020) (Note: Arrow shows lower respiratory infection moving from the 4th rank to 1st rank).

| Causes of most death | IHME Rank (2007) | IHME Rank (2017) | Percentage change % (2007–2017) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malaria | 1 | 4 | -35.8 |

| Diarrheal disease | 2 | 5 | -39.5 |

| HIV/AIDs | 3 | 3 | -25.7 |

| Lower respiratory infection | 4

|

1 | -10.7 |

| Neonatal Disorders | 5 | 2 | -1.5 |

| Tuberculosis | 6 | 6 | -15.2 |

| Meningitis | 7 | 7 | -2.0 |

| Cirrhosis | 8 | 10 | 1.3 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 9 | 8 | 24.5 |

| Stroke | 10 | 9 | 15.0 |

Figure 4.

(a) Causes of deaths due to household air pollution from solid fuels in Nigeria from 2007-2017, (b) Causes of deaths due to air pollution in Nigeria 2007–2017, (c) Causes of deaths due to ambient particulate matter pollution in Nigeria 2007–2017, (d) Causes of death due to ambient ozone pollution in Nigeria 2007–2017 (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2017).

Figure 5.

(a) Causes of DALYs due to air pollution in Nigeria from 2007-2017, (b) Causes of DALYs due to air ambient particulate matter pollution in Nigeria 2007–2017, (c) Causes of DALYs due to ambient ozone pollution in Nigeria 2007–2017, (d) Causes of DALYs due household air pollution from solid fuels in Nigeria 2007–2017 (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2017).

Figure 6.

(a) Causes of Disability Adjusted life years (DALYs) due to Unsafe Water, Sanitation, and Handwashing in Nigeria 2007–2017, (b) Causes of death due to Unsafe Water, Sanitation, and Handwashing in Nigeria 2007–2017, (c) Causes of Disability Adjusted life years (DALYs) due to Lead Exposure in Nigeria 2007–2017, (d) Causes of death due to Lead Exposure in Nigeria 2007–2017 (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2017).

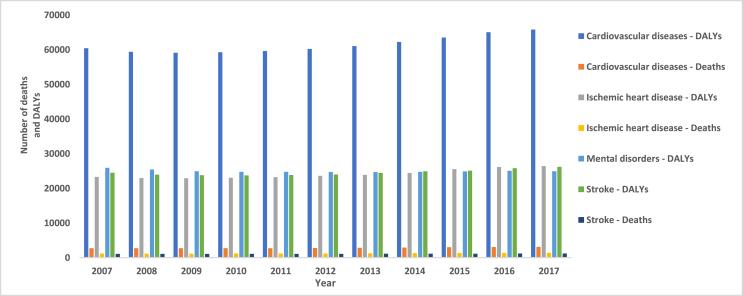

Figure 7.

Number of Deaths and DALYS due to other Environmental Risks from 2007-2017 in Nigeria (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2017).

The analysis shows that ambient ozone pollution and lead exposure negatively affect health quality, especially heart conditions; a further look at the pattern shows a gradual and upward trend. Our analytical representation shows that household air pollution from solid fuels, air pollution, ambient particulate matter pollution, ambient ozone pollution, lead exposure, and WaSH affects health quality more. The proportion of deaths for a particular cause relative to deaths from all environmental-related risks is similar to DALYs' ratio for a particular cause relative to DALYs for all environmental-related risks. Most of the high-ranked causes of death and DALYs in Nigeria are associated with environmental risked factors [35, 36]. Figure 3 shows malnutrition, unsafe sex, alcohol use, and high blood pressure as attributes of death and DALYs combined in Nigeria. These are mostly behavioral or metabolic risks (IHME, 2020). However, the environmental-related risk WaSH and air pollution spread widely and affect virtually the entire population, especially the vulnerable group in which children, elderly, pregnant women, chronic disease, and poor people.

The most common causes of most premature deaths in Nigeria were malaria, diarrheal diseases, HIV/AIDs, and lower respiratory infection by 2007. However, in 2017, the lower respiratory infection took the lead, followed by neonatal disorder, all associated with environmental interactions. The cause of most death in 2017 was attributed first to lower respiratory infection, ranked 4th in 2007, as shown in Table 1 [20]. The lower respiratory infections had a change of about -10.7%, followed by neonatal disorders, -1.5%, while malaria had -35.8% between the years 2007–2017, according to Organization health data- Nigeria in Table 1 [20]. The environmental risk factors that cause DALYs and death in Nigeria are WaSH, followed by air pollution in 2017 with changes between 2007 to 2017 of WaSH -38.5% and air pollution -14.4%; showing low air quality is one of the most causes of death in Nigeria (Figure 3). This indicates a concern in Nigeria's current environmental health situation [1, 37], depicting a healthy environment is vital for increasing a healthy life span [38], which calls for immediate action from the public and policymakers for healthy lives and the environment's sustainability.

4. Health effects of environmental risk factors in Nigeria

In line with section 3, we will explain how environmental factors affect health and identify specific diseases associated with environmental risks. Nigeria's environmental problems and sources will also be reviewed to justify our findings on the status of environmental health situations. The deterioration of the environment has led to vectors' breeding [39], thereby reducing human health quality. The WHO identified some environmental factors affecting human health, including polluted air, poor sanitation, polluted water, unhealthy housing, and global environmental change. These factors are associated with acute respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases, malaria, and other vector-borne diseases, injuries and poisoning, mental health conditions, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and other infections [40, 41, 42]. This made it abundantly clear that improving environmental conditions is very imperative [43]. The paramount environmental risk factors associated with Nigeria's health patterns from our results are discussed as follows:

4.1. Air pollution

Air pollution is the discharge of any harmful substance into the air, which can cause minor health problems, including burning eyes and nose, itchy irritated throat, and breathing problems to significant health problems including chronic respiratory diseases or mortality [44]. Air pollution includes household air pollution, particulate matter pollution, ozone pollution, etc. It is mainly categorized into two based on exposure: ambient pollution in outdoor exposure and indoor pollution in an enclosed air pollution exposure [45].

In Nigeria, air pollution is associated with different health risks such as cardiovascular diseases, respiratory infections, tuberculosis, lower respiratory infections, COPD, chronic respiratory diseases, ischemic heart disease, stroke, communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases [20]. Nigeria is ranked amongst the world's first five and the largest country in Africa, with the top-most level of premature death associated with air pollution [20, 46, 47]. Globally, air pollution is estimated to cause about 29% of lung cancer deaths, 43% of COPD deaths, 25% of ischemic heart disease deaths, and 24% of stroke deaths [48].

4.1.1. Ambient air pollution

Ambient air pollutants, including particulate matter, ozone, SO2, and NO2, are related to several respiratory problems, such as bronchitis, emphysema asthma [49], heart failure hospitalizations, and mortality [13, 50]. Figure 4(a, b, c, and d) show different classifications of air pollution and health risk leading to most causes of death in Nigeria. Respiratory infections, tuberculosis, lower respiratory infections, and communicable diseases are estimated to have caused over 350 thousand deaths and 10 million people living with DALYs yearly, related to air pollution (Figures 4b, 5a), and ambient particulate matter air pollution (Figures 4c,5b) compared to other health risk associated to air pollution from 2007-2017. Ambient ozone air pollution at ground level is associated with almost two thousand deaths and over 35 thousand DALYs per annum caused by COPD and chronic respiratory disease, which has been steadily increasing since 2007–2017 in Nigeria (Figures 4d, 5c). This result indicates a significant concern [51, 52] observing ambient particulate matter pollution had a sharp shoot of associated deaths in 2012 (Figure 4d) and DALYs in 2015 (Figure 5c), both with minimal changes till 2017. Ambient air pollution is a top risk factor responsible for reducing longevity in global GBD ranking [20, 53], likewise in Nigeria. Studies showed an increase in the outdoor air pollution level in Nigeria, mainly from anthropogenic sources in the urban cities, summing up to more exposure to the population in such urban areas [53, 54]. Global average life expectancy is between 60-70years; however, in Nigeria, it is reported to be 54.4yers according to WHO [55].

The primary sources of outdoor gaseous emissions in Nigeria are from industries, automobile exhaust, electrical generating plant exhaust at homes and business centers due to an irregular power supply, emissions from the incineration of wastes, and gaseous emissions from dumpsites [33, 56, 57]. Nigerian industries' high emissions include exhausts from internal combustion engines and particulates from milling activities, cement production, and quarrying sites. Peculiar to Nigeria is the mass importation of second-hand motor vehicles, which can be used for a prolonged period, usually exceeding 30 years. Some old vehicles are still found on the road presently, usually tagged 'smoking' vehicles due to the thick exhaust emissions visible. Second-hand used cars usually have high gaseous emissions due to incomplete combustion of oil and fuel impurities that could be hazardous to public health. Motorcycles and tricycles are classified into these categories [56, 58, 59, 60]. Illegal importation of e-waste to dumpsites in the south-western part of Nigeria has been a significant problem to air pollution because scavengers go to the dumpsites and burn down the e-waste to get some vital part of it to sell. The incomplete burning of this e-waste leads to air pollution and soothes in the atmosphere [1].

Exploring crude oil, refining, and gas flaring are predominant in the southern part of Nigeria (Figure 2) [61].Residents in most states across the country burn most household wastes due to a lack of central dumpsites. The use of petrol or diesel generator as a source of electricity for both residents and industries due to lack of stable electric power is high. This has led to emissions of carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulphur dioxide (SO2), and particulate matter in the atmosphere thereby increasing air pollution and lower air quality [62]. Many of Nigeria's population suffer from cardiovascular diseases, physiological and mental health problems, respiratory system-related issues, acid rain, and destruction of vegetation resulting from air pollution.

These anthropogenic activities and occupational exposures have led to air pollution-related risk health problems [1, 63]. There is also a high potential exposure to unknown hazards due to increasing industrialization in the country. For example, the increasing number of industries, especially in Nigeria's urban areas, has introduced new chemicals into the atmosphere [64, 65]. The presumption is that some of such chemicals have or will present unexpected problems to public health and need to be treated before their release [66, 67].

4.1.2. Household air pollution

More than 50% of domestic energy used in developing countries is generated through biomass burning [68]. Studies have shown that 76% of the global particulate matter air pollution emissions in the developing world are indoor with a peak concentration often exceeding 2000 μg/m3 [69]. For instance, in Nigeria, over 70% of the population are still using biomass for fuel woods with a poorly ventilated kitchen [70, 71]. Examples of sources in small settlements and villages are fuelwood, charcoal, and agro-waste (e.g., palm fruit fiber, palm kernel shell); in bigger towns; fuelwood, charcoal, and kerosene in some instances, plastic wastes; in cities; sources are fuelwood (usually at restaurants), charcoal, and gas [57, 72]. These fuel sources usually undergo incomplete combustion, leading to hazardous gases and particulate matter, which causes harm to human health.

Indoor air pollution from household fuel use has been ranked the second high-risk factor responsible for adverse human health, with the potential of resulting in respiratory and cardiovascular mortality [73]. It may also lead to low birthweights and neurodevelopmental impairment [74]. Household air pollution from the use of solid fuels in Nigeria causes lower respiratory infections, respiratory infections, and communicable diseases resulting in over 180 thousand deaths (Fig 4a) and 12 million people with DALYs (Figure 5d) per annum in Nigeria from 2007-2017 showing a steady decline with yearly progression This studies in line with previous studies have shown that increasing air pollution levels are associated with adverse health effects, hospitalization, and early death among the exposed groups.

4.2. Water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH)

Unsafe water, poor sanitation, and hygiene have led to an annual death of about 1.7 million people [6], including over 70 thousand children under the age of 5 [75], [76] due to high vulnerability to water-borne diseases. Unsafe water, sanitation, and handwashing have been associated with enteric infections, diarrheal diseases, respiratory infections, tuberculosis, lower respiratory infections, communicable, neonatal, and nutritional diseases in humans [20]. Figure 6(a,b) shows a high number of deaths greater than 300 thousand and more than 3 million DALYs lost in Nigeria yearly associated with unsafe water and sanitation with enteric infections, diarrheal diseases, communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional disease as the leading causes from 2007-2017 with yearly progressive steady decline.

Population growth has led to an increase in demand for high-quality water and sanitation facilities. As domestic and economic activities increase, the value of water increases, making water pollution more detrimental to human health. Domestic water pollution, industrial water pollution, agriculturally based water pollution, and oil spill water pollution are the primary sources of water contamination in Nigeria. The World Bank report on Nigeria also indicates a deficit of 43 healthy years of life per 1000 due to diarrhea [77, 78]. Studies also reported that Nigeria had progressed in access to water and improved sanitation from 1990. However, the pace of progress slowed down, resulting in 56 million without water access and another 130 million without access to improved sanitation as of 2015 [79], with over 45 million people in Nigeria practicing open defecation [77].

Unhygienic disposal of waste in waterways blocks the waterways resulting in flooding during the rainy season, increasing water contamination, breeding of mosquitoes, emergence, and fast spread of water-borne disease; accumulated waste is usually a breeding ground for various diseases and disease vectors [1]. Many states in Nigeria do not have a central sewage collection center or central dumpsites and have poor sanitary infrastructural management [80]. Studies show that untreated sewage at Lagos' and Abuja's open solid-waste dumpsites [81, 82] have contaminated water systems, leading to health risks caused by poor hygiene such as diarrhea-related disorders, bilharzia among others [71]. People living close to these waste sites, especially in urban areas, end up eating food or drinking water with high nitrate and other harmful chemicals. During the rainy season in Nigeria, rain mixed with waste can contaminate clean surface water and percolate through the soil into underground water.

Health issues have been increasing due to oil spills and illegal industrial waste in the Niger Delta regions because many industries in oil exploration, transportation, import, and export have little consideration of environmental issues. Within 1976–2009 there has been a report of about 9583 accidents and disasters resulting from oil exploration activities, including oil spills on either rivers and or coastal waters posing the communities' health at risk [83, 84]. UN study in 2011 on the effect of oil spillage in the Niger Delta reported that the majority of the people living in oil-producing areas suffer from chronic diseases all their lives due to drinking water contaminated with high levels of hydrocarbon [37]. Also, the benzene level in the Niger Delta is 900 times higher than the WHO standard, and at a depth of 5 m, oil was found [37]. Industrial waste, which contains chemicals and heavy metals usually deposited in water, has resulted in most aquatic animals' death due to oxygen depletion and ingestion of heavy metals [85]; thus, affecting the health of people who consume aquatic animals.

Arsenic and heavy metals deposited in water from industrial waste usually infiltrate into underground water and wells, resulting in physical, muscular, neurological degenerative processes that cause brain disorder and nervous system diseases [86] to people. Polluted water from the mining site can affect the population's health who use it as a drinking water source. Waste from textile industries, sugar industries, pulp and paper industries, petroleum, and many other industries in Nigeria are usually improperly disposed of on land or waterways, becoming an urban environmental problem. Improper disposition of toxic and non-toxic waste degrades land also makes surface and underground water unhygienic and unsafe for humans or agricultural use [9].

4.3. Lead exposure

Blood lead levels are another concern of the currently rapid industrializing countries [87]. This blood lead exposure affects children's cognitive function. Since there is no safe blood lead level identified for a child, any exposure must be handled remarkably [35]. Besides, lead exposure generally occurs without common symptoms or signs; hence it is rarely recognized [4, 87, 88]. GBD health data has associated lead exposure with having a causative effect on various diseases such as cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, mental disorder, and stroke [20]. Figure 6 (c and d) shows the cause of over 2,500 deaths and about 600 thousand DALYs lost yearly due to lead exposure in Nigeria between 2007-2017, with cardiovascular disease and ischemic heart disease on a steady rise. There is a need for concerned organizations and institutions to eliminate childhood exposures to lead to reduce the risk of lead exposure and promote public health in general.

The lead dust is usually dispersed into the environment during the extraction of gold, thus exposing the public to health defects when the lead is inhaled through the air or ingested in unsafe water [4, 88]. Studies reported that most lead in Nigeria had been exposed to the environment through unsafe mining practices by the community [34, 89, 90]. Most miners do not wear protective equipment while mining, hence returning home with lead dust on their clothes and rocks containing gold with high lead levels [88, 91]. Investigations in Zamfara reveal widespread lead-poison, with thousands of children living with dangerous levels of blood lead and hundreds of death and animals due to this lead risk [92]. Some environmental health reports for surveys and research conducted in Nigeria over the previous years show lead metal at unsafe levels has gotten in homes, especially in Northern Nigeria [13, 93]. The water from the village's wells in Zamfara shows high levels of this heavy metal, and children in this community have blood lead in dangerous levels [4, 64, 82].

4.4. Other environmental risks

Nigeria faces a wide array of other environmental problems, including deforestation, desertification, wind erosion, flooding, and climate change. Some have seemingly minor risks at an individual level, while in synergy, they contribute significantly to more deaths and DALYs combined. Figure 7 shows the number of deaths and DALYs due to other environmental risks from 2007-2017 in Nigeria; the number of DALYs caused by the cardiovascular disease has been steadily rising as the year progresses, with an estimate of 60 thousand population affected each year. This can contribute to the rise of respiratory disease from 4th rank to 1st rank (Table 1) between 2007-2017. Stroke, ischemic heart disease, and mental disorder show little changes maintaining a range between 22,000 to 26,000 DALYs yearly from 2007-2017 in Nigeria. Approximately 1000 deaths are attributed to ischemic heart disease and stroke respectively per annum, while an estimated 2000 deaths are attributed to cardiovascular diseases per annum. An estimate of 140 thousand deaths is attributed to other environmental risks yearly.

More than 70% of Nigeria's forest land has been cut down due to settlements, increase in urbanization [94], construction of roads, use of biomass as a significant source of cooking fuel, and wood as raw material for different constructions and much industrial use [60, 95]. All these results in deforestation, loss of wildlife, and change in the micro-climate. Deforestation in the Northern part of Nigeria (Figure 2), especially the Sahel-savannah region, has led to more desert encroachment and sand storm, another source of air pollution and respiratory health problem.

Climate change, desert encroachment, and deforestation have led to the blowing away of the land surface in Nigeria's Northern part [9], while heavy rainfalls often flood and wash away a large portion of plain lands. This is usually due to low topography, lack of proper drainage, and disposition of waste in waterways by people [96, 97]. This has resulted in the loss of cultivations, fertile soils, homes are washed away by floods, and disease outbreaks carried by dirty water. Diarrhea and breading of disease vectors are paramount in flooded areas causing various health effects [98].

5. Summary, research needs, and recommendation

Environmental health has become a significant concern in Nigeria. This paper reviews the current status and existing environmental health situations in Nigeria. Leading studies have been reviewed in this paper, and the key findings are as follows:

-

•

Nigeria is faced with environmental problems such as air pollution, water pollution, lead exposures, poor waste management, deforestation, desertification, wind erosion, and flooding, which has harmed the population.

-

•

In Nigeria, lower respiratory infection associated with the environmental risk factor is the highest-ranked cause of death in 2017.

-

•

Environmental factors such as ambient air pollution, household air pollution, unsafe water, sanitation, hand washing, and lead poisoning are associated with most health-related causes of death in Nigeria from 2007-2017

-

•

Air pollution, household air pollution, and WaSH showed a prolonged but progressive decline while ambient particulate matter pollution, ambient ozone pollution. Lead exposure shows a steady rise in association to death and DALYs in Nigeria, proving a significant concern in an environmental health-related risk situation.

-

•

Other high causes of death associated with environmental risk factors include COPD, chronic respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, enteric infections, diarrheal diseases, communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional disease, which has led to approximately over 800 thousand deaths and 26 million people living with DALYs yearly in Nigeria

In Nigeria, there is a need to appropriately implement environmental health policies and enact other pertinent policies to mitigate the environmental health situation. Also, there is a need to have a directorate of environmental health to ensure all concerned activities are well-coordinated [93, 99].

5.1. Research needs

There is a need to create a framework for coordinating research activities with considerable inputs from the Health, Policy, Systems, Research, and Analysis (HPSR + A). Need for incorporating HPSR + A training and research at students' early training stage [100, 101]. Capacity building of all departments offers environmental health research in terms of human resources to identify unknown environmental hazards from chemicals in the environment. Policymakers need to take advantage of pre-existing financial and administrative governance approaches [102] to establish organizational, staff, and course advancement in environmental health research and training. The future environmental health practitioners and policymaker's engagement should consider building capacity researchers in HPSR + A, especially in advocacy skills to determine the community's needs effectively.

There is also a need for prior determined, pre-existing communication channels of research findings on dissemination workshops, briefing notes, and technical meetings, harnessed with advocacy as an approach to strengthening engagements and linkages between practitioners and policymakers. There is an urgent need to establish further and develop frameworks to facilitate networking and research activities in academic institutions and significantly in policy institutions, emphasizing socio-cultural similarities such as information management and bureaucracy. Most importantly, forming systems to coordinate government, research organizations, and donors in environmental health policy research structures.

5.2. Recommendations

The state of Nigeria's environment is at a critical stage, which can have more health risks that can affect an extended period beyond the present condition if not mitigated. Thus, the need to implement immediate actions for a healthy environment and increase life expectancy in Nigeria. Below are some recommendations;

-

•

Second-hand vehicle exhaust is a significant source of air pollution [103]; likewise demonstrates the improper disposition and burning of e-waste [104]. The incomplete combustion of hydrocarbons produces soot into the atmosphere. The Nigerian customs service should put more crackdowns and severe punishment for the illegal importation of second-hand vehicles and e-waste. There should be more vehicle inspections to ensure vehicle owners service their cars regularly and old vehicles are flagged off the roads to reduce air pollutants' emissions. Through such, only good condition vehicles can move on the road.

-

•

Inadequate infrastructure such as uninterrupted electric power supply had been a significant challenge in Nigeria for a while [33]. The population keeps using generators associated with air pollution and respiratory-related health risk [59]. Constant electric power supply will reduce the use of diesel generators by residents, offices, and organizations, which will lead to cleaner air.

-

•

The percentage of families using biomass fuelwood is high. This has led to respiratory health effects on vulnerable groups, mostly women and children [70, 105, 106]. Clean energy improved stoves at an affordable price can reduce over 70% of Nigerian homes' dependence on biomass as cooking fuel. Biogas and other renewable energies such as solar power and wind energy can be used as alternative energy sources to reduce petroleum products' dependency.

-

•

Increased industrialization has led to high potential exposure to air pollution, and most industries do not adhere to the federal government's air quality emission standard. The gas flaring policy for the complete halting of gas flaring in Nigeria has not been adhered to by industries [83]. This has led to thick soothe covering over cities, respiratory problems to the population, and acid rain. Policymakers and inspectors should make industries adhere strictly to the sets standard of treatments and proper discharge of industrial waste, either liquid, solid, or gaseous.

-

•

The rate of illegal mining has been on the rise in the north-central region [107]. Improper mining carried out, such as non-use of protective equipment and abandonment of mining sites without proper closure after mining, has led to water contamination during the rainy season [89, 107]. Poor drainage aids the flooding of contaminated water to water bodies used by the nearby communities. This has resulted in increasing lead poisoning and many heavy metal-related diseases. There is a need for a crackdown on illegal mining and constant surveillance of mining or potential mining sites by the environmental protection agencies and law enforcement agencies. This will ensure legal mining sites adhere strictly to mining regulations on proper disposal of mining waste, landfilling, and appropriate closure of mined areas when mining is over. This will reduce hazards caused by flooding and contamination of land and water to communities around mining sites.

-

•

Most houses in Nigeria were built without proper town planning or allocation for sewage and other waste disposal capacity [104], thus; becoming a peril to adequate waste management. A central sewage system, government-built dumpsites, and garbage sorting as part of proper waste management will help keep a sanitary environment, reduce water contamination, recycle and reuse some recyclable waste. Waste management legislation, adequate policy, and a planning framework for waste management are needed.

-

•

Basic sanitation infrastructural amenities such as public toilets are inadequate or completely lacking in various regions of Nigeria [108], resulting in open defecation practices by the population. Nigeria's adopted Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) in 2008 had made progress in portable water availability [77]. However, there is a need to build more public toilets in communities, major cities, and market places. This will reduce open defecation, which has resulted in the emergence and transfer of infectious diseases such as cholera.

6. Conclusion

The situation of the state of the environment in Nigeria is rapidly degenerating. The environment affected by humans' activities shows the negative environmental health issues being on the rise. The environmental health situation is usually an interconnection between human activities and the environment. Nigeria faces emerging challenges in environmental health, such as climate change, low air quality, water contamination, and natural hazards like floods, storms, and drought. All of these negatively affect human health. Nigeria being a significant oil producer, has problems associated with exploration, such as oil spillage on water and land and gas flaring leading to air pollution. Most of the highest-ranked risk factors causing the most death and disability combine in Nigeria are environmental-related.

Environmental health policy is necessary to contain the surging rise of environmental problems. The need for environmental health legislation and inspection to ensure the public and industries adhere to regulations set is vital. This will reduce environmental health risks and more gain in healthy life span in Nigeria. A healthy environment will lead to a healthy life.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the investigation, development and writing of this article.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Orisakwe O.E. second ed. Elsevier Inc.; 2019. Nigeria: Environmental Health Concerns. October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knowlton K. Encyclopedia of Environmental Health. Elsevier Inc.; 2011. Globalization and environmental health; pp. 995–1001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen S. Behavior, Health, and Environmental Stress. Springer US; 1986. Environmental stress and health; pp. 103–142. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thurtle N. “Description of 3,180 courses of chelation with dimercaptosuccinic acid in children ≤5 y with severe lead poisoning in zamfara, northern Nigeria: a retrospective analysis of programme data. PLoS Med. 2014;11(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . WHO; 2017. WHO | 10 Facts on the State of Global Health.https://www.who.int/features/factfiles/global_burden/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO 9 out of 10 people worldwide breathe polluted air, but more countries are taking action. Saudi Med. J. 2018;39(6):641–643. Accessed: Mar. 14, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/02-05-2018-9-out-of-10-people-worldwide-breathe-polluted-air-but-more-countries-are-taking-action. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uzochukwu B. “Health policy and systems research and analysis in Nigeria: examining health policymakers’ and researchers’ capacity assets, needs and perspectives in south-east Nigeria. Health Res. Pol. Syst. 2016;14(1) doi: 10.1186/s12961-016-0083-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amegah A.K., Agyei-Mensah S. Urban air pollution in sub-saharan Africa: time for action. Environ. Pollut. 2017;220:738–743. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babanyara Y.Y., Usman H.A., Saleh U.F. An overview of urban poverty and environmental problems in Nigeria. J. Hum. Ecol. Aug. 2010;31(2):135–143. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akpodiogaga-a P., Odjugo O. General overview of climate change impacts in Nigeria. J. Hum. Ecol. Jan. 2010;29(1):47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarraud M., Chung Y.S. Air quality, atmosphere, and health. Air Qual. Atmos. Heal. 2008;1(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farooq M., Meraj G., Sensing R. J & K # BeatAirPollution,” J K Envis Newsl. 2019. State of environment & its related issues. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdulraheem I.S. Primary health care services in Nigeria: critical issues and strategies for enhancing the use by the rural communities. J. Public Heal. Epidemiol. 2012;4(1):5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dooyema C.A. Outbreak of fatal childhood lead poisoning related to artisanal gold mining in northwestern Nigeria, 2010. Environ. Health Perspect. Apr. 2012;120(4):601–607. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Idowu O.O. Challenges of urbanization and urban growth in Nigeria. Am. J. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2013;1(2):79–95. [Online]. Available: http://www.rspublication.com/ajscs/ajsas.html. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Acaps . 2018. NIGERIA Floods. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bissadu K.D., Koglo Y.S., Johnson D.B., Akpoti K. Coarse scale remote sensing and GIS evaluation of rainfall and anthropogenic land use changes on soil erosion in nasarawa state , Nigeria , West Africa. J. Geosci. Geomat. 2017;5(6):259–266. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Idowu A.P., Adagunodo E.R., Esimai O.A., Idowu P.A. Development of a web based environmental health tracking system for Nigeria. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Comput. Sci. Jul. 2012;4(7):61–71. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okafor G.C., Ogbu K.N. Assessment of the impact of climate change on the freshwater availability of Kaduna River basin, Nigeria. J. Water Land Dev. 2018;38(1):105–114. [Google Scholar]

- 20.IHME . Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; 2020. Nigeria.http://www.healthdata.org/nigeria accessed Mar. 04, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ezebilo E.E., Animasaun E.D. Public-private sector partnership in household waste management as perceived by residents in southwest Nigeria. Waste Manag. Res. Aug. 2012;30(8):781–788. doi: 10.1177/0734242X11433531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Monetary Fund Nigeria: 2019 article IV consultation- press release; staff report; and statement by the executive director for Nigeria. IMF Staff Ctry. Reports. 2019;16(101):1. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amade A. Vanguard Newspapers; 2013. Industrial Hub: Why More Companies Are Moving to Ogun? [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eneh O.C. “Managing Nigeria’s environment: the unresolved issues. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;4(3) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen A.J. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30505-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roth G.A. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naghavi M. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balakrishnan K. 2019. The Impact of Air Pollution on Deaths, Disease burden, and Life Expectancy across the States of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang H. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kyu H.H. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. Nov. 2018;392(10159):1859–1922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32335-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray C.J.L. “Population and fertility by age and sex for 195 countries and territories, 1950–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. Nov. 2018;392(10159):1995–2051. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32278-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewandowski C.M., Co-investigator N., Lewandowski C.M. Python for data Analysis. Eff. Br. Mindfulness Interv. Acute Pain Exp. An Exam. Individ. Differ. 2015;1:1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mbamali I., Stanley A., Zubairu I. “Environmental, health and social hazards of fossil fuel electricity generators: a users’ assessment in kaduna, Nigeria. Am. Int. J. Contemp. Res. 2012;2(9) www.aijcrnet.com Accessed: Mar. 13, 2020. [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson R.J., Dannenberg A.L., Frumkin H. Health and the built environment: 10 years after. Am. J. Publ. Health. 2013;103(9):1542–1544. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301482. American Public Health Association. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Godson M.C., Nnamdi M.J. Environmental determinants of child mortality in Nigeria. J. Sustain. Dev. Dec. 2011;5(1):p65. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Health . 2020. Effects Institute and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation's Global Burden of Disease Project, “State of Global Air 2020.https://www.stateofglobalair.org/sites/default/files/documents/2021-01/soga-country-profile-nigeria-c.pdf Accessed: Jan. 18, 2021. [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unep . 2011. Environmental Assessment of Ogoniland; pp. 39–205. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Obaje S.O. Electronic waste scenario in Nigeria: issues, problems and solutions. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Invent. ISSN. 2013;2(11) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bradley D., Stephens C., Harpham T., Cairncross S. 1992. A Review of Environmental Health Impacts in Developing Country Cities. [Google Scholar]

- 40.WHO Health aspects of air pollution with particulate matter, ozone and nitrogen dioxide report on a WHO working group OZONE-adverse effects NITROGEN DIOXIDE-adverse effects AIR POLLUTANTS. Environ. Adv. Eff. Meta Anal. Air-Stand. Guidel. 2003;(January):30. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/112199/E79097.pdf Accessed: Oct. 21, 2020. [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organization . WHO; 2018. Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data | Concentrations of fine Particulate Matter (PM2.5)http://www.who.int/gho/phe/air_pollution_pm25_concentrations/en/ Accessed: Oct. 22, 2020. [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oyedepo S.O. Dataset on noise level measurement in Ota metropolis, Nigeria. Data Br. 2019;22:762–770. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2018.12.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalu N.N., Zakirova Y.L. A review in Southeastern Nigeria: environmental problems and management solutions. Rudn J. Ecol. Life Saf. 2019;27(3) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cerbu G., Codoceo F., De C., Kasal T., De Kuppler A. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2019. Air Pollution • Air Pollution. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Troeger C. “Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory infections in 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30310-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and OECD OECD regions at a glance. Choice Rev. Online. 2008;45(5) 45-2390-45–2390. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bae S., Hong Y.C. Health effects of particulate matter. J. Korean Med. Assoc. 2018;61(12):749–755. [Google Scholar]

- 48.WHO . 2018. Sustainable Cities Health at the Heart of Urban Development; pp. 2–3.http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs266/en/ [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mabahwi N.A.B., Leh O.L.H., Omar D. Human health and wellbeing: human health effect of air pollution. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. Oct. 2014;153:221–229. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shah A.S.V. Global association of air pollution and heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9897):1039–1048. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60898-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marais E.A. Anthropogenic emissions in Nigeria and implications for atmospheric ozone pollution: a view from space. Atmos. Environ. 2014;99:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ipeaiyeda A.R., Adegboyega D.A. Assessment of air pollutant concentrations near major roads in residential, commercial and industrial areas in Ibadan City, Nigeria. J. Heal. Pollut. Mar. 2017;7(13):11–21. doi: 10.5696/2156-9614-7-13.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aliyu Y.A., Botai J.O. Reviewing the local and global implications of air pollution trends in Zaria, northern Nigeria. Urban Clim. Dec. 2018;26(October 2017):51–59. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aliyu Y.A., Musa I.J., Jeb D.N. Geostatistics of pollutant gases along high traffic points in Urban Zaria. Int. J. Geomatics Geosci. 2014;5(2):19–31. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Etchie T.O. The gains in life expectancy by ambient PM2.5 pollution reductions in localities in Nigeria. Environ. Pollut. May 2018;236:146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akinlo A.E. Electricity consumption and economic growth in Nigeria: evidence from cointegration and co-feature analysis. J. Pol. Model. Sep. 2009;31(5):681–693. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Babayemi J.O., Ogundiran M.B., Osibanjo O. Overview of environmental hazards and health effects of pollution in developing countries: a case study of Nigeria. Environ. Qual. Manag. Sep. 2016;26(1):51–71. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anago Ifeanyi. The Nigerian ExperienceFIG XXII International Congress; ” Usa, DC: 2002. Environmental Impact Assessment as a Tool for Sustainable Development. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ladan S.I. 2013. Examining Air Pollution and Control Measures in Urban Centers of Nigeria.https://www.ripublication.com/ijeem_spl/ijeemv4n6_16.pdf Accessed: Mar. 13, 2020. [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 60.Omofonmwan S.I., Osa-Edoh G.I. The challenges of environmental problems in Nigeria. J. Hum. Ecol. Jan. 2008;23(1):53–57. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fayiga A.O., Ipinmoroti M.O., Chirenje T. Environmental pollution in Africa. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018;20(1):41–73. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mbamali I., Stanley A., Zubairu I. Environmental, health and social hazards of fossil fuel electricity generators: a users’ assessment in kaduna, Nigeria. Am. Int. J. Contemp. Res. 2012;2(9):237–245. http://www.aijcrnet.com/journals/Vol_2_No_9_September_2012/28.pdf Accessed: Mar. 13, 2020. [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anyanwu B.O., Ezejiofor A.N., Igweze Z.N., Orisakwe O.E. Heavy metal mixture exposure and effects in developing nations: an update. Toxics. Nov. 02, 2018;6(4) doi: 10.3390/toxics6040065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Greig J. Association of blood lead level with neurological features in 972 children affected by an acute severe lead poisoning outbreak in zamfara state, Northern Nigeria. PloS One. Apr. 2014;9(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Welford R. Vol. 3. Earthscan from Routledge; 2016. (Corporate Environmental Management 3: towards Sustainable Development). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tirima S. Environmental remediation to address childhood lead poisoning epidemic due to artisanal gold mining in Zamfara, Nigeria. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016;124(9):1471–1478. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1510145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nwachukwu I., Mbachu I.C. The socio-cultural implications of crude oil exploration in Nigeria - ScienceDirect. Polit. Ecol. Oil Gas Act. Niger. Aquat. Ecosyst. Jan. 2018:177–190. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ezzati M., Kammen D.M. The health impacts of exposure to indoor air pollution from solid fuels in developing countries: knowledge, gaps, and data needs. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002;110(11):1057–1068. doi: 10.1289/ehp.021101057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pinault L. Risk estimates of mortality attributed to low concentrations of ambient fine particulate matter in the Canadian community health survey cohort. Environ. Heal. A Glob. Access Sci. Source. 2016;15(1) doi: 10.1186/s12940-016-0111-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oluwole O. Effect of stove intervention on household air pollution and the respiratory health of women and children in rural Nigeria. Air Qual. Atmos. Heal. Mar. 2013;6(3):553–561. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ana G., Adeniji B., Ige O., Oluwole O., Olopade C. Exposure to emissions from firewood cooking stove and the pulmonary health of women in Olorunda community, Ibadan, Nigeria. Air Qual. Atmos. Heal. Jun. 2013;6(2):465–471. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fagbeja M., Olumide O., Rabiu B. 2017. An Overview of AQ Monitoring and Prediction in Nigeria.https://docplayer.net/amp/88477418-An-overview-of-aq-monitoring-and-prediction-in-nigeria.html Accessed: Mar. 12, 2020. [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alam D.S. Adult cardiopulmonary mortality and indoor air pollution: a 10-year retrospective cohort study in a low-income rural setting. Glob. Heart. Sep. 2012;7(3):215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thompson L.M. Does household air pollution from cooking fires affect infant neurodevelopment? Developing methods in the NACER pilot study in rural Guatemala. Lancet Glob. Heal. 2014;2:S18. [Google Scholar]

- 75.UNICEF . 2017. Promising practices in WASH - case studies of Nigeria; pp. 1–79. [Google Scholar]

- 76.UNICEF & WHO . Unicef/Who; 2019. Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation and hygiene 2000-2017; p. 140.https://data.unicef.org/resources/progress-drinking-water-sanitation-hygiene-2019/ Accessed: Mar. 14, 2020. [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abramovsky L., Augsburg B., Lührmann M., Oteiza F., Rud J.P. Jan. 2019. Community Matters: Heterogeneous Impacts of a Sanitation Intervention.http://arxiv.org/abs/1901.03544 Accessed: Mar. 12, 2020. [Online]. Available: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.UNICEF . Unicef; 2019. UNICEF Somalia - Water, Sanitation and Hygiene - Priority Issues.https://data.unicef.org/topic/water-and-sanitation/overview/ (accessed Mar. 14, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oleribe O.O., Taylor-Robinson S.D. Before sustainable development goals (SDG): why Nigeria failed to achieve the millennium development goals (MDGs) Pan Afr. Med. J. Jun 22 2016;24:156. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.24.156.8447. African Field Epidemiology Network. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oyeniyi A.B. “Waste management in contemporary Nigeria : the Abuja example. Int. J. Polit. Good Gov. 2011;2(2):1–18. http://onlineresearchjournals.com/ijopagg/art/73.pdf Accessed: Mar. 14, 2020. [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 81.Endsjö P.C. Urbanization in Nigeria. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. 1973;27(3):207–219. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lawanson T.O., Fadare S. Neighbourhood differentials and environmental health interface in Lagos metropolis, Nigeria. Habitat Int. Jul. 2013;39:240–245. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kadafa A.A. Environmental impacts of oil exploration and exploitation in the Niger Delta of Nigeria. Glob. J. Sci. Front. Res. Environ. Earth Sci. 2012;12(3):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dami A., Ayuba H.K., Amukali O. Effects of gas flaring and oil spillage on rainwater collected for Drinking in okpai and beneku, delta state, Nigeria. Socialscienceresearch.Org. 2012;12(13) http://socialscienceresearch.org/index.php/GJHSS/article/view/450 [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ipingbemi O. Socio-economic implications and environmental effects of oil spillage in some communities in the Niger delta, J. Integr. Environ. Sci. Mar. 2009;6(1):7–23. [Google Scholar]

- 86.V Mohod C., Dhote J. Review of heavy metals in drinking water and their effect on human health. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2013;2(7):2992–2996. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Plumlee G.S. Linking geological and health sciences to assess childhood lead poisoning from artisanal gold mining in Nigeria. Environ. Health Perspect. Jun. 2013;121(6):744–750. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1206051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lo Y.C. Childhood lead poisoning associated with gold ore processing: a village-level Investigation-Zamfara State, Nigeria, October-November 2010. Environ. Health Perspect. Oct. 2012;120(10):1450–1455. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Orisakwe O.E., Oladipo O.O., Ajaezi G.C., Udowelle N.A. Horizontal and vertical distribution of heavy metals in farm produce and livestock around lead-contaminated goldmine in dareta and abare, zamfara state, northern Nigeria. J. Environ. Public Health. 2017;2017:3506949. doi: 10.1155/2017/3506949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Orisakwe O.E., Nduka J.K., Amadi C.N., Dike D.O., Bede O. Heavy metals health risk assessment for population via consumption of food crops and fruits in Owerri, South Eastern, Nigeria. Chem. Cent. J. 2012;6(1):77. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-6-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.UNDP . 2018. National Human Development Report 2018 - Timor-Leste. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lo Y.C. Childhood lead poisoning associated with gold ore processing: a village-level Investigation-Zamfara State, Nigeria, October-November 2010. Environ. Health Perspect. Oct. 2012;120(10):1450–1455. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Obinaju B.E., Alaoma A., Martin F.L. Novel sensor technologies towards environmental health monitoring in urban environments: a case study in the Niger Delta (Nigeria) Environ. Pollut. Sep. 2014;192:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Crespo Cuaresma J. Economic development and forest cover: evidence from satellite data. Sci. Rep. Jan. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/srep40678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Matemilola S., Adedeji O.H., Enoguanbhor E.C. The Political Ecology of Oil and Gas Activities in the Nigerian Aquatic Ecosystem. Elsevier Inc.; 2018. Land use/land cover change in petroleum-producing regions of Nigeria; pp. 257–276. [Google Scholar]

- 96.O.K I., V.U. O., A.I. C., A.O. U., C.F. E., C.E O. Evaluation of geotechnical properties of gully erosion materials in ORLU and its environs, IMO state, Nigeria. Int. J. Adv. Geosci. Apr. 2016;4(1):8. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Valentina A.N., Lekwot V.E., Yakubu A.A., Chukuma E.A., Danjuma A., Kwesaba A. Perception and response to gully erosion in jos south local government area of plateau state, Nigeria. J. Multidiscip. Sci. Res. 2015;3(1):14–18. http://jmsr.rstpublishers.com/ Accessed: Aug. 19, 2020. [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 98.N. P. C. NPC Federal Ministry of Health (Nigeria), ICF International . Fairfax, United States of America; 2020. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018.http://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/nigeria-demographic-and-health-survey-2018 Accessed: Mar. 04, 2020. [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 99.Maantay J.A., McLafferty S. Geospatial Analysis of Environmental Health. Springer Netherlands; 2011. Environmental health and geospatial analysis: an overview; pp. 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gonzalez Block M.A., Mills A. Assessing capacity for health policy and systems research in low and middle income countries. Health Res. Pol. Syst. Jan. 2003;1:1. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bruce N., Perez-Padilla R., Albalak R. Indoor air pollution in developing countries: a major environmental and public health challenge. Bull. World Health Organ. 2000;78(9):1078–1092. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lê G. A new methodology for assessing health policy and systems research and analysis capacity in African universities. Health Res. Pol. Syst. Dec. 2014;12(1):59. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-12-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ndoke P.N., Jimoh O.D. Impact of traffic emission on air quality in A developing city of Nigeria. AU J. Technol. 2005;8(4):222–227. http://www.journal.au.edu/au_techno/2005/apr05/vol8no4_abstract10.pdf [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 104.Imam A., Mohammed B., Wilson D.C., Cheeseman C.R. Solid waste management in Abuja, Nigeria. Waste Manag. 2008;28(2):468–472. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gordon S.B. Respiratory risks from household air pollution in low and middle income countries. Lancet Resp. Med. 2014;2(10):823–860. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70168-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dutta A. Household air pollution and angiogenic factors in pregnant Nigerian women: a randomized controlled ethanol cookstove intervention. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;599–600(May):2175–2181. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gutti B., Aji M.M., Magaji G. Environmental impact of natural resources exploitation in Nigeria and the way forward. J. Appl. Technol. Environ. Sanit. 2012;2(2):95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Odipe O.E. Assessment of environmental sanitation, food safety knowledge, handling practice among food handlers of bukateria complexes in iju town, akure north of ondo-state, Nigeria. SSRN Electron. J. 2019 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.