The mammalian liver contains numerous polyploid hepatocytes, and polyploidization is significantly enhanced during aging.1 In some tissues, such as bone marrow, diploid stem cells constitutively proliferate for tissue renewal and regeneration, whereas polyploidization leads to cell cycle arrest and differentiation enhancing cellular functions.2 In contrast, notably, polyploid hepatocytes are an important source of liver regeneration under the stress conditions.3 Polyploidy in hepatocytes has also been hypothesized to contribute to enhancing metabolic functions, and could influence functional properties of the liver.4 However, it has been unknown how polyploid hepatocytes play roles in physiological cellular renewal and impact on liver (dys)functions during the aging process.

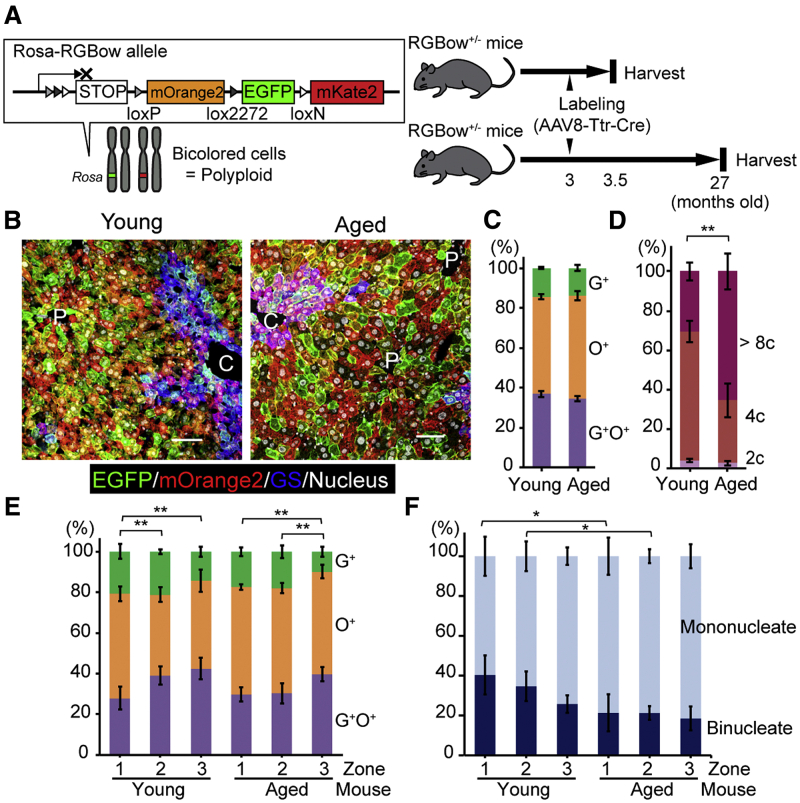

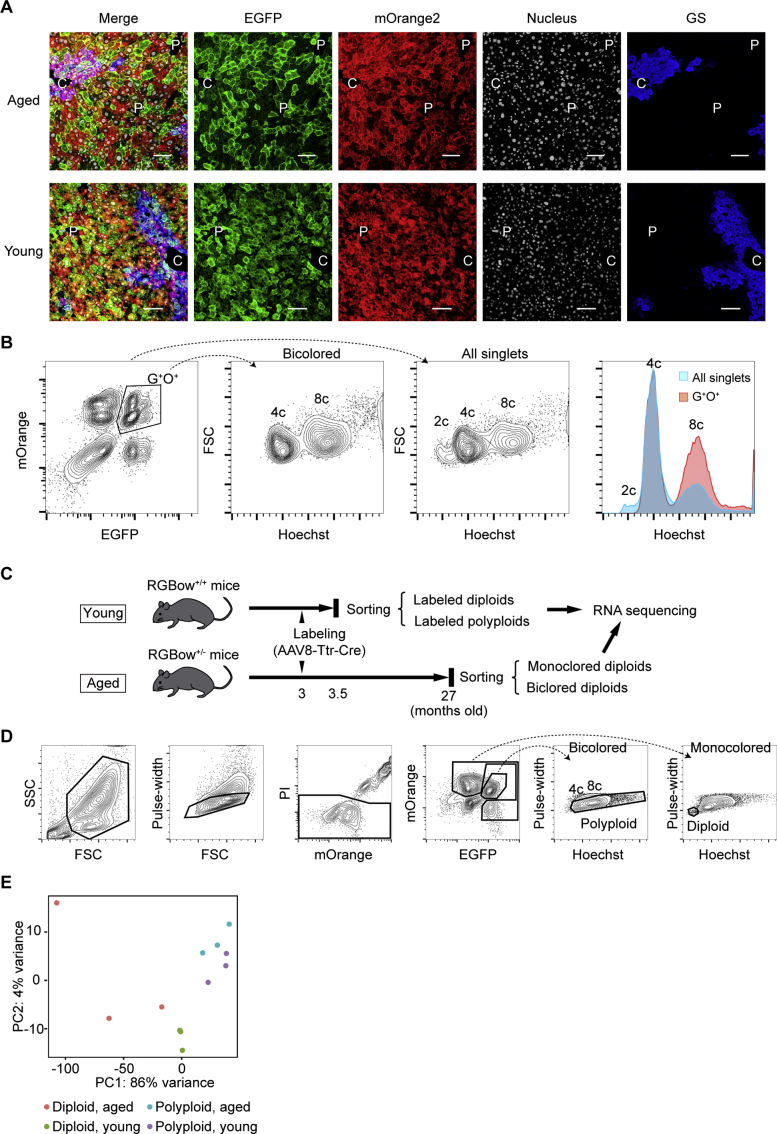

To examine whether polyploid hepatocytes contribute to cellular renewal during normal aging, livers of aged Rosa-RGBow+/- mice5 (27 months old) were compared with their young 3-month-old counterparts (Figure 1A). The Rosa-RGBow allele consists of multiple fluorescent reporter genes, and a subset of polyploid cells are labeled as bicolored cells after Cre recombination in heterozygous Rosa-RGBow mice (Figure 1A).3 As we previously showed,3 rAAV8-Ttr-Cre (6 × 1010 vector genomes) efficiently (about 75%) and specifically labeled hepatocytes in adult Rosa-RGBow+/- mice (Figure 1B, Supplementary Figure 1A), and all bicolored hepatocytes were polyploid (Supplementary Figure 1B). Interestingly, aged livers at >700 days after rAAV8-Ttr-Cre administration contained a substantial number of bicolored hepatocytes at a frequency similar to young livers (Figure 1C). Because murine hepatocytes divide every 200–300 days during normal homeostasis, this result suggests that abundant polyploid hepatocytes, which account for >90% of hepatocytes in the liver, repeatedly divide to maintain normal turnover of hepatocytes during aging. Indeed, young hepatocytes underwent further polyploidization during aging by going through additional cell cycles (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Polyploid hepatocytes serve as the source of cellular turnover during aging. (A) Experimental overview. (B) Microscopic images of young and aged Rosa-RGBow+/- mouse livers. Rosa-RGBow reporters are expressed in a membrane-bound manner, and mKate2 is not shown because its expression is quite rare (<2% of labeled cells). Single color images are shown in Supplementary Figure 1A. Scale bars, 100 μm. C, central veins; P, portal veins. (C) Frequencies of labeled hepatocytes. (D) Ploidy distribution of hepatocytes. C and D were analyzed by flow cytometry. (E) Frequencies of labeled hepatocytes in each liver zone. (F) Frequencies of mononucleated and binucleated cells among bicolored hepatocytes. E and F were analyzed by microscopy. Error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 4). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01. G+, EGFP+; O+, mOrange+.

Furthermore, microscopic analysis revealed that both young and aged livers exhibited a similar bias of distribution of bicolored hepatocytes among liver zones. More bicolored hepatocytes were consistently located in pericentral zone 3 than in periportal zone 1 in both young and aged mice (Figure 1B and E). This is consistent with a biased distribution of diploid hepatocytes to the periportal area,6 and argues against dynamic migration of hepatocytes from zone 1 to zone 3 or vice versa during aging. Importantly, despite the constant frequencies of bicolored hepatocytes during aging, binucleated cells among bicolored hepatocytes were significantly fewer in the aged liver than in the young liver (Figure 1F). Given that hepatocyte polyploidization occurs via cytokinesis failure and generates binucleated cells at first,7 these findings indicate that bicolored binucleated polyploidized cells underwent mitoses with complete cytokinesis, and generated mononucleated cells over time. Taken together, these findings suggest that polyploid hepatocytes proliferate and are an important contributor to maintenance of the liver during normal aging.

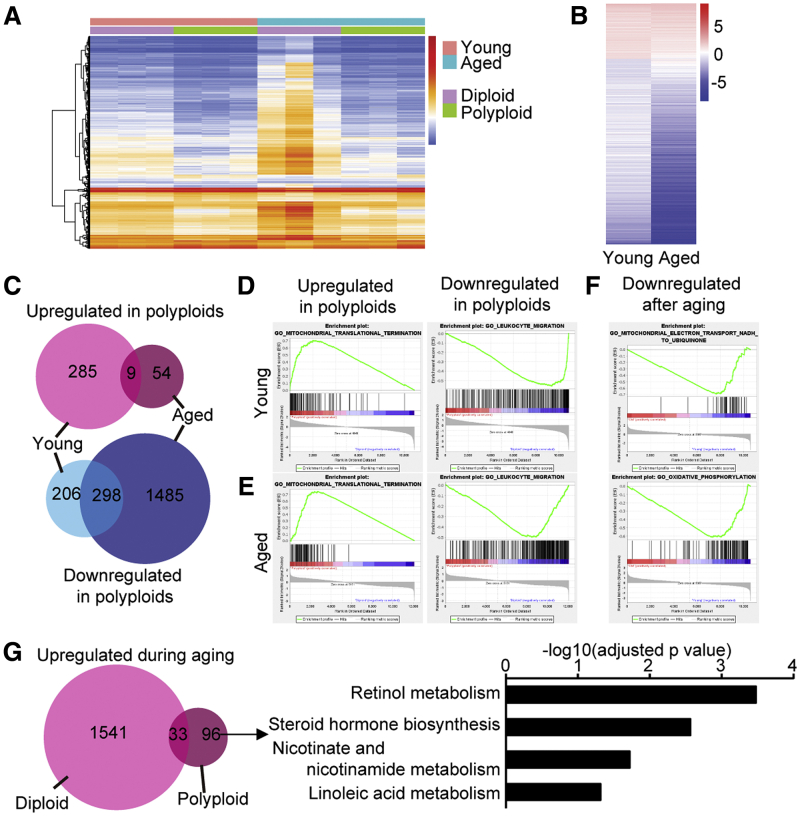

Next, the impact of polyploidization on aging-related functional changes of hepatocytes was analyzed by RNA sequencing using diploid and polyploid hepatocytes sorted from young and aged livers (Supplementary Figure 2C and D). Heatmap and principal component analysis showed that each sample exhibited similar gene expression patterns among the 4 groups analyzed (Figure 2A, Supplementary Figure 1E).

Figure 2.

Impacts of aging on gene expressions of polyploid hepatocytes. (A) Heatmap of RNA sequencing data. (B) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes between diploid and/or polyploid hepatocytes. (C) Venn diagrams of differentially expressed genes that were upregulated or downregulated in polyploid hepatocytes compared with diploid counterparts. (D, E) Examples of gene sets enriched in polyploid and diploid hepatocytes. D and E are derived from young and aged liver, respectively. (F) Examples of gene sets enriched in aged polyploid hepatocytes compared with young counterparts. (G) Pathways upregulated in 96 differentially expressed genes that were uniquely upregulated in polyploids after aging.

The global pattern of gene expression changes between diploid and polyploid hepatocytes was similar in young and aged livers (Figure 2B). Defining differentially expressed genes as those with P < .05 and absolute value of log2 fold change >1 identified hundreds of common differentially expressed genes especially in downregulated genes in polyploids (Figure 2C, Supplementary Table 1). Gene set enrichment analysis revealed that genes related to immune responses were commonly downregulated in polyploids compared with diploids both in young and aged livers, whereas genes associated with mitochondrial functions were commonly upregulated in polyploids (Figure 2D and E, Supplementary Table 2). Interestingly, downregulation of immune-related genes and upregulation of genes activating mitochondrial functions were previously reported in decidual polyploids in the uterus,8 suggesting that polyploid cells exhibit somewhat similar expressional characteristics regardless of cell types and animal age.

Influence of aging on polyploid hepatocytes was further examined by comparing bicolored polyploid hepatocytes in aged livers with polyploid counterparts in young livers. Because aged livers were labeled about 2 years before harvest, bicolored cells in aged livers had been polyploid for a long time. Interestingly, gene set enrichment analysis found that mitochondrial function genes were significantly downregulated in polyploids after aging, whereas there was no significant gene ontology upregulated in aged polyploids (Figure 2F, Supplementary Table 3). Mitochondrial dysfunction is one of the features of aging,9 and given that mitochondrial function genes are upregulated in polyploids at baseline, polyploid cells may be predisposed to mitochondrial dysfunction during aging. However, 96 differentially expressed genes that were uniquely upregulated in polyploids after aging were significantly enriched with genes annotated to lipid and fatty acid metabolism by pathway analysis, which was consistent with a previous report that compared unsorted young and aged liver tissues (Figure 2G, Supplementary Table 3).10 Aging-related metabolic changes of the liver may be mainly attributed to that of polyploid hepatocytes.

In summary, we showed here that the abundantly present polyploid hepatocytes in the mouse liver are the source of physiological hepatocyte turnover during aging. No evidence for a dominant contribution of a diploid liver stem cell during aging was found. Similar processes may occur in the polyploids of other organs with slow cellular turnover, such as acinar cells in the pancreas. In addition, polyploids exhibited characteristic gene expressions compared with diploids, which may be predetermined irrespective of cell types. Moreover, polyploidy-related upregulation of mitochondrial function genes was especially impaired during aging, and polyploid hepatocytes showed higher expressions of lipid and fatty acid metabolic genes than young cells. Although the mechanisms that link polyploidy and age-related liver dysfunction need further investigation, findings here underscore the importance of polyploid hepatocytes in aging-related metabolic liver diseases.

Acknowledgements

The rAAV-Ttr-Cre construct was kindly provided by Dr Holger Willenbring of University of California San Francisco. RNA sequencing FASTQ data were submitted to the NCBI GEO: Accession number GSE161171.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest This author discloses the following: Oregon Health and Science University and Markus Grompe have a significant financial interest in Yecuris, Corp, Tigard, Oregon a company that may have a commercial interest in the results of this research and technology. This potential conflict of interest has been reviewed and managed by Oregon Health and Science University. The other authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant CA190144 and the research grant of Astellas Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure.

References

- 1.Kudryavtsev B.N. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1993;64:387–393. doi: 10.1007/BF02915139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ravid K. J Cell Physiol. 2002;190:7–20. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsumoto T. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;26:34–47. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gentric G. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He M. Neuron. 2016;91:1228–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanami S. Cell Tissue Res. 2017;368:405–410. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guidotti J.E. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19095–19101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300982200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma X. PLoS One. 2011;6 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez-Otin C. Cell. 2013;153:1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bochkis I.M. Cell Rep. 2014;9:996–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.