Key Points

Question

How do clinical outcomes and costs associated with hospitalization for status epilepticus differ among patients with low, moderate, and highly refractory status epilepticus?

Findings

This cross-sectional study examined 43 988 hospitalizations related to status epilepticus from 2016 to 2018 in the US and found that patients with highly refractory status epilepticus account for more than 40% of hospitalizations in the US. Hospitalization has a mortality rate of 19% and median cost of $25 105, which is higher than hospitalization for both moderate and low refractory disease.

Meaning

Among patients with status epilepticus, increased refractoriness appears to be associated with worse outcomes and higher costs.

Abstract

Importance

Status epilepticus (SE) is associated with poor clinical outcomes and high cost. Increased levels of refractory SE require treatment with additional medications and carry increased morbidity and mortality, but the associations between SE refractoriness, clinical outcomes, and cost remain poorly characterized.

Objective

To examine differences in clinical outcomes and costs associated with hospitalization for SE of varying refractoriness.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A cross-sectional study of 43 988 US hospitalizations from January 1, 2016 to December 31, 2018, was conducted, including patients with primary or secondary International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, diagnosis specifying “with status epilepticus.”

Exposure

Patients were categorized by administration of antiseizure drugs given during hospitalization. Low refractoriness denoted treatment with none or 1 intravenous antiseizure drug. Moderate refractoriness denoted treatment with more than 1 intravenous antiseizure drug. High refractoriness denoted treatment with 1 or more intravenous antiseizure drug, more than 1 intravenous anesthetic, and intensive care unit admission.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Outcomes included discharge disposition, hospital length of stay, intensive care unit length of stay, hospital-acquired conditions, and cost (total and per diem).

Results

Among 43 988 hospitalizations for SE, 22 851 patients (51.9%) were male; mean age was 49.9 years (95% CI, 49.7-50.1 years). There were 14 694 admissions (33.4%) for low refractory, 10 140 (23.1%) for moderate refractory, and 19 154 (43.5%) for highly refractory SE. In-hospital mortality was 11.2% overall, with the highest rates among patients with highly (18.9%) compared with moderate (6.3%) and low (4.6%) refractory SE (P < .001 for all comparisons). Median hospital length of stay was 5 days (interquartile range [IQR], 2-10 days) with greater length of stay in highly (8 days; IQR, 4-15 days) compared with moderate (4 days; IQR, 2-8 days) and low (3 days; IQR, 2-5 days) refractory SE (P < .001 for all comparisons). Patients with highly refractory SE also had greater hospital costs, with median costs of $25 105 (mean [SD], $41 858 [$59 063]) in the high, $10 592 (mean [SD], $18 328 [$30 776]) in the moderate, and $6812 (mean [SD], $11 532 [$17 228]) in the low refractory cohorts (P < .001 for all comparisons).

Conclusions and Relevance

Status epilepticus apparently continues to be associated with a large burden on patients and the US health system, with high mortality and costs that increase with disease refractoriness. Interventions that prevent SE from progressing to a more refractory state may have the potential to improve outcomes and lower costs associated with this neurologic condition.

This cross-sectional study compares the outcomes and costs of treatments among patients with low, moderate, and highly refractive status epilepticus.

Introduction

Status epilepticus (SE) is a common and life-threatening disorder, with an estimated annual incidence between 12 and 61 cases per 100 000 person-years and annual.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 Despite the high frequency and associated mortality, there are limited data detailing health care use and inpatient costs associated with SE-related hospitalizations and characterizing the variance of clinical outcomes and costs as a function of disease severity and medication refractoriness.8

Patients with SE often require treatment with multiple antiseizure drugs (ASDs) in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting to terminate seizures, leading to high costs and likely associated morbidity.9 Studies examining outcomes after first- and second-line treatment with benzodiazepines and intravenous ASDs suggest that seizures continue in 15% to 30% of patients who are categorized as having refractory SE (RSE) and often require third-line therapy with anesthetic infusions of agents such as propofol and midazolam to achieve seizure control.10,11,12,13,14,15 Patients with super-refractory status epilepticus (SRSE) who have persistent or recurrent seizures after receiving at least 24 hours of an infused anesthetic typically require treatment with additional anesthetic medications.9 Therapies for RSE and SRSE, the underlying seizure etiologic factors, and the need for prolonged ICU studies and mechanical ventilation are often associated with medical complications, high costs, and high health care resource use.9,16,17,18 Mortality rates associated with RSE are as high as 35% and nearly half of the surviving patients have subsequent neurologic deficits.19 However, a systematic understanding of the clinical burden and costs of RSE on a population-based scale and how these variables change with more and less severe disease because of inconsistent definitions and difficulty identifying this patient population by specific diagnosis codes remains to be determined.9,20

Because more severe disease is associated with treatment refractoriness and higher need for ASDs, databases that track inpatient medication administration provide an opportunity to use medication data as an indication of refractoriness and potential disease severity. With this in mind, we used a large administrative database containing medication data to examine the clinical and economic burden of illness associated with SE of varying degrees of refractoriness.

Methods

Data Source and Study Design

We performed a descriptive cross-sectional analysis of SE admissions using data from the Premier Healthcare Database from January 1, 2016, to December 31, 2018. The Premier Healthcare Database is a publicly available, deidentified, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant, hospital-based, all-payer database capturing hospital- and patient-level data from approximately 25% of US hospitalizations and 231 million unique patients.1,21,22,23 Given the use of deidentified data exclusively, the study was deemed not to require ethics board review based on the policy of the Office of Human Subjects Research Protections, National Institutes of Health, under the revised Common Rule. We categorized SE according to ASD use and examined clinical outcomes, health care resource use, and costs across increasing refractoriness. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Study Population

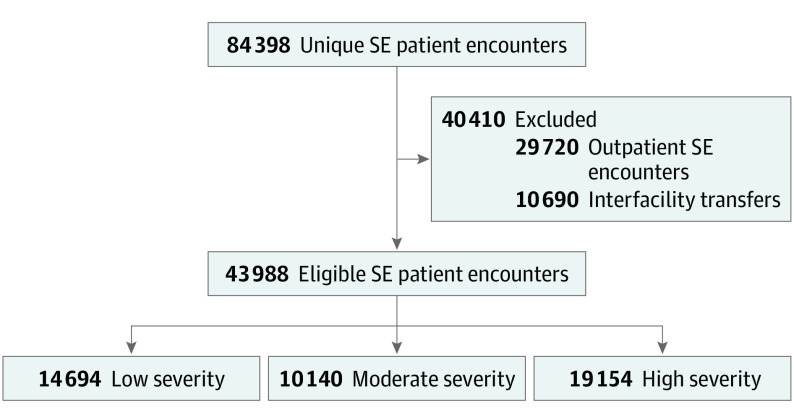

We included patients of any age who had a primary or secondary diagnosis of SE, specified by an International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code including “with status epilepticus,” which has been used and validated for SE and epilepsy in past studies (eTable 1 in the Supplement).1,21,22,23,24,25 We limited our cohort to patients with inpatient admissions, thus excluding encounters isolated to the emergency department and outpatient setting. We also excluded patients transferred to or from a different acute hospital because their hospitalization and costs would not be fully captured (Figure).

Figure. Patient Selection Flow Diagram.

All patient encounters with a primary or secondary International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision diagnosis code specifying status epilepticus (SE) were identified. Outpatient encounters, emergency department encounters that did not lead to hospital admission, and hospitalizations that involved transfer to or from a different acute care hospital were excluded (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Definitions of Disease Refractoriness

Three patient cohorts were defined according to the number and type of intravenous medication used for treatment. We labeled these cohorts low, moderate, and highly refractory SE under the assumption that patients with more refractory disease receive more intravenous ASDs and infusions. We did not have access to prehospital treatment data and thus did not include intramuscular or noninfusion intravenous benzodiazepine administration in our definition because this first-line therapy would not be completely captured.26,27 Intravenous ASDs included brivaracetam, fosphenytoin, lacosamide, levetiracetam, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and valproic acid. We labeled medications that are delivered as continuous infusions in the treatment of SE as intravenous anesthetics based on the common use of this term. These drugs included etomidate, ketamine, midazolam, methohexital, pentobarbital, propofol, and thiopental. We classified drugs as intravenous anesthetics used for third-line SE treatment if administered while the patient was admitted to an ICU to limit misclassifying drugs used for procedural sedation. Midazolam is used as first-line therapy as an injection or third-line therapy as a continuous infusion. We recorded midazolam as a third-line intravenous anesthetic if administered in the ICU on the same day as or following administration of an intravenous ASD. Low refractory SE was defined as treatment with none or 1 intravenous ASD and no third-line intravenous anesthetic. Moderate refractory SE was defined as treatment with more than 1 intravenous ASD and no third-line intravenous anesthetic. Highly refractory SE was defined as treatment with at least 1 intravenous ASD and at least 1 third-line intravenous anesthetic. The latter cohort is reflective of RSE and SRSE, but we did not have data about seizure recurrence to determine whether patients truly met criteria for RSE or SRSE.

Measurements

Patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, and payer type, as well as hospital location (rural vs urban), teaching status, and bed size were captured to describe the study population. Hospitals were designated urban if located in an urban geographic area of 50 000 or more people or an urban cluster of less than 50 000 but 2500 or more people. To infer the source of SE, we examined discharge diagnosis codes and abstracted common causes of SE, including ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, central nervous system tumor, traumatic brain injury, meningoencephalitis, hyponatremia, and alcohol withdrawal. We took previously published International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision codes for each of these diseases and created a cross-walk to ICD-10 codes that we used to examine hospitalizations in this cohort (eTable 2 in the Supplement).10,13,16

Outcomes

We examined clinical outcomes, hospital and ICU length of stay (LOS), and cost. Clinical outcomes included discharge disposition, need for mechanical ventilation, and hospital-acquired conditions, which included catheter-associated urinary tract infections, pressure ulcers (stage III/IV), vascular catheter–associated infections, and mechanical ventilation–associated complications (ventilator-associated pneumonia and mechanical complication of respirator) identified from ICD-10 codes based on the World Health Organization classification (eTable 3 in the Supplement).28,29 Hospitalization costs included total and per diem cost of the stay.

Statistical Analysis

We examined baseline characteristics in the total study population and across SE cohorts through a series of pairwise comparisons (low vs moderate refractoriness, moderate vs high refractoriness, and low vs high refractoriness) using a bootstrap-based analysis of variance for parametric data, Kruskal-Wallis tests for nonparametric data, and χ2 tests for categorical data. For multiple data comparisons, the Tukey test was applied. We calculated the proportion of patients who had a suspected source of SE according to the coding criteria described above. We examined our outcome measures (discharge disposition, need for mechanical ventilation, hospital-acquired conditions, hospital and ICU LOS, and cost) using the same pairwise comparisons as the baseline characteristics. In addition, because LOS is likely related to the presence of hospital-acquired conditions and the underlying cause of SE, we categorized hospitalizations according to whether there was a hospital-acquired condition (yes/no) and suspected source of SE (yes/no) and examined the LOS across these 2 dichotomous variables. We also performed each analysis for the subgroup of patients aged 18 years or younger (pediatric SE). We had complete LOS and cost data. Demographic, admission, and discharge information recorded as unknown, unable to determine, and information unavailable were combined as unknown. A small number of patients had sex recorded as unknown; thus, the data were censored to maintain deidentification standards. There was no imputation of data. Analyses were performed using SAS/STAT, version 14.3 (SAS Institute Inc). With 2-sided testing, findings were considered significant at P < .05.

Results

Patient Selection and Characteristics

We identified 84 398 patient encounters for SE. There were 29 720 outpatient and emergency department encounters and 10 690 transfers excluded from the main analysis (eTable 4 in the Supplement). Of the remaining 43 988 inpatient encounters, there were 14 694 patients (33.4%) with low, 10 140 (23.1%) with moderate, and 19 154 (43.5%) with highly refractory SE. Patients had a mean age of 49.9 years (95% CI, 49.7-50.1 years), with a median age of 55 years (interquartile range [IQR], 32-68 years), 5125 (11.7%) were younger than 18 years, and 21 137 (48.1%) were female (Figure; eTable 5 and eTable 6 in the Supplement). The largest proportion of patients had Medicare (19 874 [45.2%]) as their primary payer vs Medicaid (12 276 [27.9%]) and private/commercial plans (2087 [4.7%]). Patients with low refractory SE were younger and more likely to be White (Table 1). There were 12 236 patients (27.8%) classified as having a suspected source of SE, with the most common etiologic factors being hyponatremia (4585 [10.4%]), acute ischemic stroke (2644 [6.0%]), central nervous system tumor (1916 [4.4%]), and alcohol withdrawal (1356 [3.1%]) (Table 1). Further characteristics of the cohorts, including diagnostic codes, treatments received, and hospital characteristics, are included in eTables 7-10 in the Supplement.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized for Status Epilepticus.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P values | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refractory SE | All | Low vs moderate | Moderate vs highly | Low vs highly | Overall | ||||

| Low | Moderate | Highly | |||||||

| Unique SE patient encounters | 14 694 (33.4) | 10 140 (23.1) | 19 154 (43.5) | 43 988 (100) | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 7352 (50.0) | 5072 (50.0) | 10 427 (54.4) | 22 851 (51.9) | |||||

| Female | 7342 (50.0) | 5068 (50.0) | 8727 (45.6) | 21 137 (48.1) | >.99 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Age, y | |||||||||

| Mean | 45.5 | 52.2 | 52.0 | 49.9 | <.001 | .64 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Median (IQR) | 50 (25-66) | 57 (35-75) | 56 (37-68) | 55 (32-68) | <.001 | .04 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Bootstrap 95% CI | 45.1-46.0 | 51.7-52.7 | 51.7-52.3 | 49.7-50.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Race | |||||||||

| White | 9292 (63.2) | 5973 (58.9) | 11 670 (60.9) | 26 935 (61.2) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Black | 3204 (21.8) | 2758 (27.2) | 4760 (24.9) | 10 722 (24.4) | |||||

| Other | 1853 (12.6) | 1197 (11.8) | 2264 (11.8) | 5314 (12.1) | |||||

| Unknown | 345 (2.3) | 212 (2.1) | 460 (2.4) | 1017 (2.3) | |||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Hispanic | 1153 (7.8) | 793 (7.8) | 1510 (7.9) | 3456 (7.9) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Non-Hispanic | 10 084 (68.6) | 7240 (71.4) | 13 800 (72.0) | 31 124 (70.8) | |||||

| Unknown | 3457 (23.5) | 2107 (20.8) | 3844 (20.1) | 9408 (21.4) | |||||

| Payer | |||||||||

| Medicare | 5890 (40.1) | 5141 (50.7) | 8843 (46.2) | 19 874 (45.2) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Medicaid | 4460 (30.4) | 2678 (26.4) | 5138 (26.8) | 12 276 (27.9) | |||||

| Managed care | 267 (15.4) | 1152 (11.4) | 2635 (13.8) | 6054 (14.0) | |||||

| Private/commercial | 795 (5.4) | 430 (4.2) | 862 (4.5) | 2087 (4.7) | |||||

| Other governmenta | 375 (2.6) | 219 (2.2) | 506 (2.6) | 1100 (2.5) | |||||

| Otherb | 907 (6.2) | 520 (5.1) | 1170 (6.1) | 2597 (5.9) | |||||

| Location (% urban) | 13 447 (91.5) | 9236 (91.1) | 17 545 (91.6) | 40 228 (91.5) | .24 | .13 | .78 | .31 | |

| Teaching status (% teaching) | 8393 (57.1) | 5516 (54.4) | 10 767 (56.2) | 24 676 (56.1) | <.001 | .003 | .10 | .001 | |

| Bed size | |||||||||

| 0-99 | 401 (2.7) | 276 (2.7) | 273 (1.4) | 950 (2.2) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| 100-199 | 1353 (9.2) | 981 (9.7) | 1468 (7.7) | 3802 (8.6) | |||||

| 200-299 | 2289 (15.6) | 1473 (14.5) | 2509 (13.1) | 6271 (14.3) | |||||

| 300-399 | 2314 (15.7) | 1824 (18.0) | 2901 (15.1) | 7039 (16.0) | |||||

| 400-499 | 1833 (12.5) | 1202 (11.9) | 2336 (12.2) | 5371 (12.2) | |||||

| ≥500 | 6504 (44.3) | 4384 (43.2) | 9667 (50.5) | 20 555 (46.7) | |||||

| Seizure etiologic factors | |||||||||

| Any suspected cause | 3031 (20.6) | 2597 (25.6) | 6608 (34.5) | 12 236 (27.8) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Ischemic stroke | 483 (3.3) | 545 (5.4) | 1616 (8.4) | 2644 (6.0) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 119 (0.8) | 116 (1.1) | 524 (2.7) | 759 (1.7) | .0075 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| CNS tumor | 487 (3.3) | 556 (5.5) | 873 (4.6) | 1916 (4.4) | <.001 | .006 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Traumatic brain injury | 55 (0.4) | 69 (0.7) | 216 (1.1) | 340 (0.8) | .009 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Meningoencephalitis | 119 (0.8) | 116 (1.1) | 524 (2.7) | 759 (1.7) | .008 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Hyponatremia | 1186 (8.1) | 958 (9.4) | 2441 (12.7) | 4585 (10.4) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Alcohol withdrawal | 469 (3.2) | 188 (1.9) | 699 (3.6) | 1356 (3.1) | <.001 | <.001 | .02 | <.001 | |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable; SE, status epilepticus.

Other government includes charity care, indigent care, and other government payers.

Other includes self-pay, workers compensation, and other.

Clinical Outcomes

Patients with SE had an overall in-hospital mortality rate of 11.2%, with the highest in-hospital mortality rate in patients with highly refractory SE (18.9%) compared with moderate (6.3%) and low (4.6%) refractory SE (P < .001 for all comparisons) (Table 2). A composite of in-hospital mortality and discharge to hospice increased these rates to 25.3% for highly refractory, 13.6% for moderate refractory, and 7.9% low refractory SE (P < .001 for all comparisons; eTable 11 in the Supplement). The proportion of patients discharged home decreased from 8919 patients (60.7%) with low refractory SE to 4504 patients (44.4%) with moderate refractory SE to 6598 patients (34.4%) with highly refractory SE (Table 2). When pediatric and adult patients were examined independently, these findings were similar in both groups, although pediatric patients showed lower mortality rates and higher rates of discharge home overall (eTable 12 and eTable 13 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Clinical Outcomes Among Patients With SE, Including Discharge Disposition and Hospital-Acquired Conditions.

| Outcome | No. (%) | P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refractory SE | All | Low vs moderate | Moderate vs highly | Low vs highly | Overall | |||

| Low | Moderate | Highly | ||||||

| Unique SE patient encounter | 14 694 (33.4) | 10 140 (23.1) | 19 154 (43.5) | 43 988 (100) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Discharge disposition | ||||||||

| Died | 674 (4.6) | 643 (6.3) | 3622 (18.9) | 4939 (11.2) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Hospice | 492 (3.3) | 738 (7.3) | 1226 (6.4) | 2456 (5.6) | <.001 | .004 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Long-term care | 119 (0.8) | 159 (1.6) | 733 (3.8) | 1011 (2.3) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Rehabilitationa | 3512 (23.9) | 3398 (33.5) | 5838 (30.5) | 12 748 (29.0) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Home | 8919 (60.7) | 4504 (44.4) | 6598 (34.4) | 20 021 (45.5) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Otherb | 978 (6.7) | 698 (6.9)3 | 1137 (5.9)2 | 2813 (6.4) | .48 | .002 | .007 | .002 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1954 (13.3) | 1206 (11.9) | 17 336 (90.5) | 20 496 (46.6) | .001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Hospital-acquired conditionc | 2052 (14.0) | 1972 (19.4) | 4418 (23.1) | 8442 (19.2) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Catheter-associated UTI | 1770 (12.0) | 1763 (17.4) | 3497 (18.3) | 7030 (16.0) | <.001 | .06 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Pressure ulcers, stage III/IV | 154 (1.0) | 185 (1.8) | 320 (1.7) | 659 (1.5) | <.001 | .34 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Vascular catheter–associated infection | 27 (0.2) | 19 (0.2) | 79 (0.4) | 125 (0.3) | .95 | .002 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation–associated complicationd | 34 (0.2) | 18 (0.2) | 308 (1.6) | 360 (0.8) | .36 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Other infection | 240 (1.6) | 171 (1.7) | 825 (4.3) | 1236 (2.8) | .75 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: MV, mechanical ventilation; NA, not applicable; SE, status epilepticus; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Rehabilitation includes skilled nursing facility, home health agency, and rehab facility.

Other includes intermediate care facility, psychiatric hospital, court/law enforcement, and cancer hospital.

Hospital-acquired conditions included specific International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Revision 10 diagnoses identified by the US Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Mechanical ventilation–associated complications included ventilator-associated pneumonia and mechanical complication of respirator.

There were 8442 admissions (19.2%) during which the patient developed a hospital-acquired condition. The 4418 patients (23.1%) with highly refractory SE represented the highest proportion across each cohort and urinary tract infection was the most common hospital-acquired infection, occurring in 7030 (16.0%) hospitalizations overall (Table 2). Because hospital-acquired conditions are likely more frequent among patients with particular underlying sources of SE, we also examined the proportion of patients who had a suspected cause and developed a hospital-acquired condition. Across the SE study population, meningoencephalitis (31%), hyponatremia (29%), ischemic stroke (29%), and intracerebral hemorrhage (26%) were the suspected causes with the greatest rates of hospital-acquired conditions (eTable 14 in the Supplement).

Health Care Use and Costs

Overall, median hospital LOS was 5 days (IQR, 2-10 days) and LOS increased with more refractory disease, with median LOS of 3 days (IQR, 2-5 days) for patients with low, 4 days (IQR, 2-8 days) for patients with moderate, and 8 days (IQR, 4-15 days) for patients with highly refractory SE (Table 3). There were 4375 patients (29.8%) with low refractory SE and 4025 patients (39.7%) with moderate refractory SE who were admitted to the ICU, as opposed to all patients with highly refractory SE who were admitted to the ICU by definition.

Table 3. Health Care Use and Cost Outcomes.

| Variable | No. (%) | P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refractory SE | All | Low vs moderate | Moderate vs highly | Low vs highly | Overall | |||

| Low | Moderate | Highly | ||||||

| Unique SE patient encounter | 14 694 (33.4) | 10 140 (23.1) | 19 154 (43.5) | 43 988 (100) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Hospital length of stay, d | ||||||||

| Mean | 4.7 | 7.2 | 12.0 | 8.4 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 3 (2-5) | 4 (2-8) | 8 (4-15) | 5 (2-10) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Bootstrap 95% CI | 4.6-4.9 | 6.9-7.6 | 11.7-12.2 | 8.3-8.6 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| ICU admission, No. (% yes) | 4375 (29.8) | 4025 (39.7) | 19 154 (100) | 27 554 (62.6) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| ICU length of stay (for ICU patients only) | ||||||||

| Mean | 2.7 | 3.1 | 6.6 | 5.4 | .0204 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-4) | 4 (2-8) | 3 (2-6) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Bootstrap 95% CI | 2.6-2.8 | 3.0-3.3 | 6.4-6.7 | 5.4-5.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Total hospital cost, $a | ||||||||

| Mean | 11 532 | 18 328 | 41 858 | 26 304 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 6812 (3902-12 707) | 10 592 (5724-20 863) | 25 105 (13 275-48 765) | 13 201 (6429-29 199) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Bootstrap 95% CI | 11 269-11 826 | 17 750-18 983 | 41 017-42 701 | 25 942-26 746 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Cost per day, $ | ||||||||

| Mean | 2862 | 2825 | 3868 | 3291 | .4540 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 2366 (1732-3307) | 2460 (1856-3287) | 3359 (2565-4531) | 2806 (2046-3902) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Bootstrap 95% CI | 2823-2905 | 2785-2866 | 3831-3904 | 3271-3313 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; SE, status epilepticus.

Defined as the total cost (variable and fixed) to treat the patient during the hospital encounter; includes all supplies, labor, and depreciation of equipment, and is adjusted for inflation to 2019 dollars.

Because LOS is likely influenced by the presence of hospital-acquired conditions and cause of SE, we also examined how LOS differed among those with vs without a hospital-acquired condition and suspected cause of SE. Patients who developed a hospital-acquired condition and who had a suspected cause SE both had longer hospital and ICU LOS (Table 4).

Table 4. Hospital and ICU Length of Stay in Patients With a Suspected Cause of SE or a Hospital-Acquired Infection.

| Metric | Hospital-acquired condition | P value | Suspected SE factor | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

| Hospital length of stay, median (IQR), d | ||||||

| Refractory SE | ||||||

| Low | 5 (3-9) | 3 (1-5) | <.001 | 3 (2-6) | 3 (1-5) | <.001 |

| Moderate | 8 (4-13) | 4 (2-7) | <.001 | 5 (3-11) | 4 (2-7) | <.001 |

| Highly | 13 (7-23) | 6 (3-12) | <.001 | 9 (5-17) | 6 (3-11) | <.001 |

| ICU length of stay, median (IQR), d | ||||||

| Refractory SE | ||||||

| Low | 2 (1-5) | 1 (1-3) | <.001 | 2 (1-3) | 1 (1-2) | <.001 |

| Moderate | 3 (2-5) | 2 (1-3) | <.001 | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-3) | <.001 |

| Highly | 7 (3-13) | 3 (2-7) | <.001 | 5 (2-10) | 3 (2-6) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; SE, status epilepticus.

Median total hospital cost was $13 201 (mean [SD], $26 304 [$45 048]) and per diem cost was $2806 (mean [SD], $3291 [$2434]). The greatest costs were observed in patients with highly refractory SE who had a median total cost of $25 105 (mean [SD], $41 858 [$59 063]) compared with patients with low (median, $6812; mean [SD], $11 532 [$17 228]) and moderate (median, $10 592; mean [SD], $18 328 [$30 776]) refractory SE. These findings were seen in both the pediatric and adult subgroups when examined independently (eTable 15 and eTable 16 in the Supplement).

Discussion

This study found that hospitalizations for SE continue to have significant associated morbidity, mortality, and costs nationally, but this burden varied considerably across patients with differing degrees of refractoriness. Patients who required more antiseizure and anesthetic medications, presumably due to highly refractory disease, comprised nearly half of all inpatients with SE and bore disproportionately high clinical and financial costs, with an in-hospital mortality rate of 18.9%—more than 10 percentage points higher than those with low and moderate refractory disease. Patients with highly refractory SE also displayed significantly greater hospital and ICU LOS, which was reflected in significantly increased financial costs in the more refractory cohort. These outcomes reflect the heterogeneity of SE and the importance of understanding the burden of illness across the spectrum of disease.

By using medication treatment as opposed to detailed clinical information to characterize SE, the cohorts approximated but did not directly correspond to clinically defined early SE, RSE, and SRSE. The highly refractory cohort best resembled patients with RSE and SRSE, who require third-line intravenous anesthetics, and our observed mortality in this cohort was consistent with previous studies of RSE and SRSE, in which mortality rates ranged from 17% to 39%.12,30,31,32 The observed mortality rate remained consistent when we included patients who were discharged to hospice, who represented an additional 6% of this cohort. In addition, this population of patients had the lowest rates of discharge home, with approximately 30% returning home immediately at discharge, similar to previously studied populations with SRSE.1,21,22,23,33,34

Across all cohorts, nearly 20% of the admissions were associated with a hospital-acquired condition. The highest rates were again seen in the highly refractory population; however, the rates in those with moderate and highly refractory SE were qualitatively much closer than those with low refractory SE, potentially owing to the role of increased LOS, the ICU setting, and additional medications associated with the increased rates of infection seen in our population and those previously reported.21 Across all cohorts, longer hospital and ICU LOS were seen among those who developed hospital-acquired conditions, highlighting the association of these outcomes, although without explaining the exact degree to which LOS, the ICU setting, and additional medications contribute to medical complications and the degree to which these hospital-acquired conditions conversely increase LOS.

We found a total hospitalization cost of $13 201, which is similar to costs previously reported using national data.35 Costs increased substantially with increasing SE refractoriness, with total hospital cost of $25 105 and per diem cost of $2806 among those with highly refractory SE. The cost of highly refractory SE is likely associated with longer hospital LOS, longer ICU LOS, and hospital-acquired complications, as well as medications required for SE treatment. The costs associated with treatment of patients with SE likely do not comprehensively address the total cost of SE care. For example, the costs associated with subsequent care in rehabilitation and skilled nursing facilities were not captured for the nearly half of patients who were not discharged home in the present analysis, and these costs, as well as longer-term care costs, are likely to be considerable.23

Limitations

There are multiple limitations of this study. First, we did not have data about long-term outcomes, including recurrent SE, cognitive change, functional dependence, quality of life, long-term mortality, outpatient health care use, and outpatient costs36; therefore, the results of this study are likely to underestimate the cost of SE for the patients and health system. Second, there is the potential for misclassification. Our study population may have been misclassified through the use of ICD coding. Although the use of ICD-10 coding to examine SE is well established by previous studies,36 ICD-10 coding for specification of SE is imperfectly sensitive and specific. The ICD-10 codes used for this analysis did not differentiate generalized convulsive SE from other forms of SE. The ICD-10 coding also does not support definitive assessment of etiologic factors, limiting the present assessment to suspected causes based on concurrent diagnosis codes. Refractoriness of SE may have been misclassified by our decision to use the number and type of antiseizure drug as a proxy for refractory seizures. Third-line therapy was defined based on the use of drugs commonly referred to as intravenous anesthetics and an ICU stay, but we were unable to confirm that the patient received the intravenous anesthetic medication for seizure control as opposed to a different clinical indication. For instance, etomidate and methohexital are not typically used as third-line SE therapy and may reflect procedural sedation (eg, for intubation). However, of the 7610 patients receiving etomidate or methohexital, 7349 patients received an additional drug classified as an intravenous anesthetic, suggesting these patients required third-line anesthetic therapy for SE control. Misclassification may have also influenced our assessment of clinical outcomes. We relied on procedure codes to identify mechanical ventilation, which is likely insensitive because we found that only 90.5% of patients receiving intravenous anesthetics in the ICU were coded as receiving mechanical ventilation. Etomidate and methohexital are not typically used as a third-line SE therapy, and the high number of patients receiving etomidate may reflect procedural sedation (eg, potentially for intubation in the most refractory cohort). Of the 7610 patients receiving etomidate or methohexital, 7349 patients received an additional drug classified as an intravenous anesthetic. Third, we excluded patients whose hospitalization involved transfer to or from another acute care hospital and who were seen in the emergency department. The conditions of patients treated and released in the emergency department are likely less complex and expensive. However, a large proportion of transfers involved patients with highly refractory disease. The facilities treating patients with SE in this study were mostly mid to large hospitals (>300 beds), suggesting that patients with SE may be transferred to large hospitals and that these patients may reflect an increased-acuity patient population. The factor may be associated with poor clinical and economic outcomes.

Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that SE is associated with substantial mortality and hospitalization-related costs, and outcomes associated with this neurologic condition worsen with increasing disease refractoriness. More effective delivery of existing SE treatments and the development of new therapies may have the potential to prevent SE from progressing to a more refractory state, which could substantially decrease the need for ICU care, lower LOS, and reduce the high clinical and economic burden of SE for patients and our health system.

eTable 1. List of ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes Used for the Analysis

eTable 2. ICD-9 and ICD-10 Codes for Inferring Causes of Status Epilepticus

eTable 3. Hospital-Acquired Conditions

eTable 4. Care Setting for Patients Excluded for Outpatient Visits or Transfers

eTable 5. Pediatric Patient Characteristics

eTable 6. Adult Patient Characteristics

eTable 7. Top 15 Conditions by SE. Cohort and ICD-10 Code

eTable 8. Use of Benzodiazepines, Intravenous Anti-Seizure Drugs, and Drugs Considered Intravenous Anesthetics in the SE. Cohorts

eTable 9. Intravenous Anti-Seizure Drug and Drugs Considered Anesthetics in the SE. Cohorts

eTable 10. Hospital Characteristics of SE. Patient Encounters

eTable 11. Discharge Disposition Using a Composite of In-hospital Mortality and Discharge to Hospice for Mortality

eTable 12. Pediatric Clinical Outcomes

eTable 13. Adult Clinical Outcomes

eTable 14. Development of a Hospital-Acquired Condition by Suspected Cause

eTable 15. Pediatric Utilization and Cost Outcomes

eTable 16. Adult Utilization and Cost Outcomes

References

- 1.Beg JM, Anderson TD, Francis K, et al. Burden of illness for super-refractory status epilepticus patients. J Med Econ. 2017;20(1):45-53. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2016.1223680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betjemann JP, Josephson SA, Lowenstein DH, Burke JF. Trends in status epilepticus—related hospitalizations and mortality: redefined in US practice over time. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(6):650-655. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.0188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeLorenzo RJ, Hauser WA, Towne AR, et al. A prospective, population-based epidemiologic study of status epilepticus in Richmond, Virginia. Neurology. 1996;46(4):1029-1035. doi: 10.1212/WNL.46.4.1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dham BS, Hunter K, Rincon F. The epidemiology of status epilepticus in the United States. Neurocrit Care. 2014;20(3):476-483. doi: 10.1007/s12028-013-9935-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hesdorffer DC, Logroscino G, Cascino G, Annegers JF, Hauser WA. Incidence of status epilepticus in Rochester, Minnesota, 1965-1984. Neurology. 1998;50(3):735-741. doi: 10.1212/WNL.50.3.735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Logroscino G, Hesdorffer DC, Cascino G, Annegers JF, Hauser WA. Time trends in incidence, mortality, and case-fatality after first episode of status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2001;42(8):1031-1035. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.0420081031.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neligan A, Shorvon SD. Frequency and prognosis of convulsive status epilepticus of different causes: a systematic review. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(8):931-940. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kortland LM, Knake S, Rosenow F, Strzelczyk A. Cost of status epilepticus: a systematic review. Seizure. 2015;24:17-20. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shorvon S, Ferlisi M. The treatment of super-refractory status epilepticus: a critical review of available therapies and a clinical treatment protocol. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 10):2802-2818. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brophy GM, Bell R, Claassen J, et al. ; Neurocritical Care Society Status Epilepticus Guideline Writing Committee . Guidelines for the evaluation and management of status epilepticus. Neurocrit Care. 2012;17(1):3-23. doi: 10.1007/s12028-012-9695-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shorvon S. Super-refractory status epilepticus: an approach to therapy in this difficult clinical situation. Epilepsia. 2011;52(suppl 8):53-56. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03238.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayer SA, Claassen J, Lokin J, Mendelsohn F, Dennis LJ, Fitzsimmons B-F. Refractory status epilepticus: frequency, risk factors, and impact on outcome. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(2):205-210. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.2.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alldredge BK, Gelb AM, Isaacs SM, et al. A comparison of lorazepam, diazepam, and placebo for the treatment of out-of-hospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):631-637. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa002141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapur J, Elm J, Chamberlain JM, et al. ; NETT and PECARN Investigators . Randomized trial of three anticonvulsant medications for status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(22):2103-2113. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1905795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silbergleit R, Lowenstein D, Durkalski V, Conwit R; Neurological Emergency Treatment Trials (NETT) Investigators . RAMPART (Rapid Anticonvulsant Medication Prior to Arrival Trial): a double-blind randomized clinical trial of the efficacy of intramuscular midazolam versus intravenous lorazepam in the prehospital treatment of status epilepticus by paramedics. Epilepsia. 2011;52(suppl 8):45-47. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03235.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cherian A, Thomas SV. Status epilepticus. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2009;12(3):140-153. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.56312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alvarez V, Lee JW, Westover MB, et al. Therapeutic coma for status epilepticus: differing practices in a prospective multicenter study. Neurology. 2016;87(16):1650-1659. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutter R, Marsch S, Fuhr P, Kaplan PW, Rüegg S. Anesthetic drugs in status epilepticus: risk or rescue? a 6-year cohort study. Neurology. 2014;82(8):656-664. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kortland LM, Alfter A, Bähr O, et al. Costs and cost-driving factors for acute treatment of adults with status epilepticus: a multicenter cohort study from Germany. Epilepsia. 2016;57(12):2056-2066. doi: 10.1111/epi.13584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, et al. A definition and classification of status epilepticus—report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2015;56(10):1515-1523. doi: 10.1111/epi.13121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strzelczyk A, Ansorge S, Hapfelmeier J, Bonthapally V, Erder MH, Rosenow F. Costs, length of stay, and mortality of super-refractory status epilepticus: a population-based study from Germany. Epilepsia. 2017;58(9):1533-1541. doi: 10.1111/epi.13837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schubert-Bast S, Zöllner JP, Ansorge S, et al. Burden and epidemiology of status epilepticus in infants, children, and adolescents: a population-based study on German health insurance data. Epilepsia. 2019;60(5):911-920. doi: 10.1111/epi.14729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sánchez Fernández I, Amengual-Gual M, Barcia Aguilar C, Loddenkemper T. Estimating the cost of status epilepticus admissions in the United States of America using ICD-10 codes. Seizure. 2019;71:295-303. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2019.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Premier Applied Sciences. Premier Healthcare Database: data that informs and performs. Published March 2, 2020. Accessed December 21, 2020. https://learn.premierinc.com/white-papers/premier-healthcare

- 25.American Hospital Association. Fast facts on US hospitals. Published 2020. Accessed December 13, 2020. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/01/2020-aha-hospital-fast-facts-new-Jan-2020.pdf

- 26.Jette N, Beghi E, Hesdorffer D, et al. ICD coding for epilepsy: past, present, and future—a report by the International League Against Epilepsy Task Force on ICD codes in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2015;56(3):348-355. doi: 10.1111/epi.12895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mbizvo GK, Bennett KH, Schnier C, Simpson CR, Duncan SE, Chin RFM. The accuracy of using administrative healthcare data to identify epilepsy cases: a systematic review of validation studies. Epilepsia. 2020;61(7):1319-1335. doi: 10.1111/epi.16547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guterman EL, Burke JF, Josephson SA, Betjemann JP. Institutional factors contribute to variation in intubation rates in status epilepticus. Neurohospitalist. 2019;9(3):133-139. doi: 10.1177/1941874418819349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Li Y, Yan J. Tools of utilization and cost in healthcare. Published 2019. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/touch/index.html

- 30.Rossetti AO, Logroscino G, Bromfield EB. Refractory status epilepticus: effect of treatment aggressiveness on prognosis. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(11):1698-1702. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.11.1698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Novy J, Logroscino G, Rossetti AO. Refractory status epilepticus: a prospective observational study. Epilepsia. 2010;51(2):251-256. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02323.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holtkamp M, Othman J, Buchheim K, Meierkord H. Predictors and prognosis of refractory status epilepticus treated in a neurological intensive care unit. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(4):534-539. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.041947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferlisi M, Shorvon S. The outcome of therapies in refractory and super-refractory convulsive status epilepticus and recommendations for therapy. Brain. 2012;135(pt 8):2314-2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kortland L-M, Knake S, von Podewils F, Rosenow F, Strzelczyk A. Socioeconomic outcome and quality of life in adults after status epilepticus: a multicenter, longitudinal, matched case–control analysis from Germany. Front Neurol. 2017;8:507. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ala-Kokko TI, Säynäjäkangas P, Laurila P, Ohtonen P, Laurila JJ, Syrjälä H. Incidence of infections in patients with status epilepticus requiring intensive care and effect on resource utilization. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2006;34(5):639-644. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0603400509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sculier C, Gaínza-Lein M, Sánchez Fernández I, Loddenkemper T. Long-term outcomes of status epilepticus: a critical assessment. Epilepsia. 2018;59(suppl 2):155-169. doi: 10.1111/epi.14515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. List of ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes Used for the Analysis

eTable 2. ICD-9 and ICD-10 Codes for Inferring Causes of Status Epilepticus

eTable 3. Hospital-Acquired Conditions

eTable 4. Care Setting for Patients Excluded for Outpatient Visits or Transfers

eTable 5. Pediatric Patient Characteristics

eTable 6. Adult Patient Characteristics

eTable 7. Top 15 Conditions by SE. Cohort and ICD-10 Code

eTable 8. Use of Benzodiazepines, Intravenous Anti-Seizure Drugs, and Drugs Considered Intravenous Anesthetics in the SE. Cohorts

eTable 9. Intravenous Anti-Seizure Drug and Drugs Considered Anesthetics in the SE. Cohorts

eTable 10. Hospital Characteristics of SE. Patient Encounters

eTable 11. Discharge Disposition Using a Composite of In-hospital Mortality and Discharge to Hospice for Mortality

eTable 12. Pediatric Clinical Outcomes

eTable 13. Adult Clinical Outcomes

eTable 14. Development of a Hospital-Acquired Condition by Suspected Cause

eTable 15. Pediatric Utilization and Cost Outcomes

eTable 16. Adult Utilization and Cost Outcomes