Key Points

Question

Is preterm birth associated with an increased risk of heart failure in adulthood?

Findings

In this population-based cohort study of 4.1 million persons, preterm birth (gestational age, <37 weeks) and extremely preterm birth (gestational age, 22-27 weeks) were associated with 1.4-fold and 4.7-fold risks of new-onset heart failure, respectively, at ages 18 to 43 years, compared with individuals born at full term (gestational age, 39-41 weeks), which were significant increases.

Meaning

Survivors of preterm birth may need long-term clinical follow-up into adulthood for risk reduction and monitoring for heart failure.

This population-based cohort study in Sweden aims to determine whether preterm birth is associated with increased risk of heart failure from childhood into mid-adulthood per national registry data collected from 1973 to 2015.

Abstract

Importance

Preterm birth has been associated with increased risk of heart failure (HF) early in life, but its association with new-onset HF in adulthood appears to be unknown.

Objective

To determine whether preterm birth is associated with increased risk of HF from childhood into mid-adulthood in a large population-based cohort.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This national cohort study was conducted in Sweden with data from 1973 through 2015. All singleton live births in Sweden during 1973 through 2014 were included.

Exposures

Gestational age at birth, identified from nationwide birth records.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Heart failure, as identified from inpatient and outpatient diagnoses through 2015. Cox regression was used to determine hazard ratios (HRs) for HF associated with gestational age at birth while adjusting for other perinatal and maternal factors. Cosibling analyses assessed for potential confounding by unmeasured shared familial (genetic and/or environmental) factors.

Results

A total of 4 193 069 individuals were included (maximum age, 43 years; median age, 22.5 years). In 85.0 million person-years of follow-up, 4158 persons (0.1%) were identified as having HF (median [interquartile range] age, 15.4 [28.0] years at diagnosis). Preterm birth (gestational age <37 weeks) was associated with increased risk of HF at ages younger than 1 year (adjusted HR [aHR], 4.49 [95% CI, 3.86-5.22]), 1 to 17 years (aHR, 3.42 [95% CI, 2.75-4.27]), and 18 to 43 years (aHR, 1.42 [95% CI, 1.19-1.71]) compared with full-term birth (gestational age, 39-41 weeks). At ages 18 through 43 years, the HRs further stratified by gestational age were 4.72 (95% CI, 2.11-10.52) for extremely preterm births (22-27 weeks), 1.93 (95% CI, 1.37-2.71) for moderately preterm births (28-33 weeks), 1.24 (95% CI, 1.00-1.54) for late preterm births (34-36 weeks), and 1.09 (95% CI, 0.97-1.24) for early term births (37-38 weeks). The corresponding HF incidence rates (per 100 000 person-years) at ages 18 through 43 years were 31.7, 13.8, 8.7, and 7.3, respectively, compared with 6.6 for full-term births. These associations persisted when excluding persons with structural congenital cardiac anomalies. The associations at ages 18 through 43 years (but not <18 years) appeared to be largely explained by shared determinants of preterm birth and HF within families. Preterm birth accounted for a similar number of HF cases among male and female individuals.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this large national cohort, preterm birth was associated with increased risk of new-onset HF into adulthood. Survivors of preterm birth may need long-term clinical follow-up into adulthood for risk reduction and monitoring for HF.

Introduction

Preterm birth has a worldwide prevalence of nearly 11%,1 and most preterm infants now survive into adulthood.2,3 Preterm birth is associated with cardiometabolic disorders,4,5 circulatory anomalies,6,7,8,9 and cardiac remodeling10,11,12,13,14,15 that may predispose individuals to the development of heart failure (HF). Adults who were born preterm have been reported to have increased risks of hypertension,16,17 diabetes,18 lipid disorders,19 ischemic heart disease (IHD),20 and sleep-disordered breathing,21 which are known risk factors for HF.22,23,24,25 However, the long-term risk of HF after preterm birth has rarely been examined. Given the high disease burden and mortality associated with HF,26 there is a pressing need to understand the long-term risks in survivors of preterm birth to help guide their follow-up care across the life course.

A Swedish cohort study27 previously reported that persons born at gestational ages younger than 32 weeks (but not 32-36 weeks) had significantly increased risks of developing HF at ages 1 to 27 years (median age at end of follow-up, 14 years). However, these risks were not examined separately in adulthood (age >18 years), likely because of the small number of persons who had reached those ages. To our knowledge, no studies to date have examined the association between preterm birth and HF risk specifically in adulthood. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether associations previously reported earlier in life27 might be due to familial (genetic and/or environmental) factors that are shared determinants of preterm birth and HF. The relative contributions of familial factors vs direct outcomes of preterm birth to HF risks are unknown.

We sought to address these knowledge gaps by conducting a national cohort study of more than 4 million persons in Sweden. Our goals were to (1) provide population-based estimates for HF risk from childhood into mid-adulthood associated with gestational age at birth, (2) assess for sex-specific differences, and (3) explore the potential influence of shared familial (genetic and/or environmental) factors using cosibling analyses. The results may help inform long-term monitoring and early detection and treatment of HF in the growing population of children and adults born preterm.

Methods

Study Population

The Swedish Birth Register contains prenatal and birth information for nearly all births in Sweden since 1973.28 Using this register, we identified all singleton live births during 1973 through 2014. Singleton births were chosen for the primary analyses to improve internal comparability, given the higher prevalence of preterm birth and its different underlying causes among multiple births.29 Offspring of multiple births were examined separately in a secondary analysis. We excluded births that had missing information for gestational age. This study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Lund, Sweden. Participant consent was not required because this study used only anonymized, registry-based secondary data.

Gestational Age at Birth Ascertainment

Gestational age at birth was identified from the Swedish Birth Register based on maternal report of last menstrual period in the 1970s and ultrasonographic estimation starting in the 1980s and later (>70% of the cohort). This was examined alternatively as a continuous variable or categorical variable with 6 groups: extremely preterm births (gestational age, 22-27 weeks), moderately preterm births (28-33 weeks), late preterm births (34-36 weeks), early term births (37-38 weeks), full-term births (39-41 weeks, used as the reference group), and postterm births (≥42 weeks). In addition, the first 3 groups were combined to provide summary estimates for preterm birth (gestational age, <37 weeks).

Heart Failure Ascertainment

The study cohort was followed up for the earliest diagnosis of HF from birth through December 31, 2015. Heart failure was identified using International Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision (ICD-8), Ninth Revision (ICD-9), and Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes for all primary and secondary diagnoses in the Swedish Hospital, Outpatient, or Cause of Death Registries (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The Hospital Register started in 1964 and included all hospital discharge diagnoses for nearly 80% of the national population by 1973 and greater than 99% starting in 198730; these diagnoses have been reported to have positive predictive values of 81% to 95% for HF.31,32 The Outpatient Register started in 2001 and contains outpatient diagnoses from all specialty clinics nationwide. Cause of death was identified using ICD-8, ICD-9, and ICD-10 codes in the Cause of Death Register, which includes all deaths since 1960 with compulsory reporting nationwide.

Covariates

Other perinatal and maternal characteristics that may be associated with gestational age at birth and HF were identified using the Swedish Birth Register and national census data, which were linked using an anonymous personal identification number. Adjustment variables included birth year (modeled simultaneously as continuous and categorical by decade), sex, birth order (1, 2, or ≥3), first-degree family history of HF (based on nationwide inpatient and outpatient diagnoses, not self-reports, thus enabling highly complete and unbiased ascertainment), first-degree family history of IHD, and the following maternal characteristics: age (continuous), education level (≤9, 10-12, or >12 years), birth country or region (Sweden; another European country, US, or Canada; Asia; Africa; Latin America; or other/unknown), body mass index (BMI [calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared]; continuous), smoking (0, 1-9, or ≥10 cigarettes/day), preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders, and diabetes mellitus prior to delivery (ie, pregestational type 1 or type 2 or gestational diabetes).

Maternal BMI and smoking were assessed at the beginning of prenatal care starting in 1982 and were available for 61.1% and 74.2% of births, respectively. Data were greater than 99% complete for all other variables. Missing data for each variable were multiply imputed using linear or logistic regression to produce 10 imputations using all other covariates and HF as independent variables.33 As alternatives to multiple imputation, sensitivity analyses were performed that (1) restricted to individuals with complete data or (2) coded missing data for each variable as a separate category using a missing data indicator.

Patent ductus arteriosus and other congenital anomalies are more common in preterm infants and are potential mediators of HF.6,7,8,9 In secondary analyses, the main analyses were repeated after either excluding individuals with congenital anomalies or adjusting for congenital anomalies. Congenital anomalies were classified as patent ductus arteriosus, other malformations of the circulatory system, or noncirculatory malformations (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Statistical Analysis

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to compute hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for associations between gestational age at birth and risk of HF. These associations were examined across the age range of 0 to 43 years and in narrower age intervals (<1, 1-17, and 18-43 years) among persons still living in Sweden without a prior diagnosis of HF at the beginning of the respective interval. Attained age was used as the Cox model time axis. Individuals were censored at emigration as determined by the absence of a Swedish residential address in census data, a diagnosis of IHD, or death as identified in the Swedish Death Register. Analyses were conducted both unadjusted and adjusted for covariates. Absolute risk differences and 95% CIs, attributable fraction in the exposed, and population-attributable fraction were computed for each gestational age group compared with the group with full-term births.34 Potential interactions between gestational age at birth and sex were examined in association with HF risk on both additive and multiplicative scales.35 The proportional hazards assumption was assessed by examining log-log plots,36 and no substantial departures were found.

Cosibling analyses were performed on all individuals with at least 1 sibling to assess the potential influence of unmeasured shared familial (genetic and/or early-life environmental) factors.2 These analyses used stratified Cox regression with a separate stratum for each set of siblings as identified by their mother’s anonymous identification number. In the stratified Cox model, each set of siblings had its own baseline hazard function that reflected their shared genetic and environmental factors, and thus associations between gestational age at birth and HF risk were examined within the family. In addition, these analyses were further adjusted for the same covariates as in the primary analyses.

In secondary analyses, we examined (1) spontaneous vs medically indicated preterm birth in association with HF risk, (2) potential interactions between gestational age at birth and fetal growth (small for gestational age [<10th percentile for gestational age] vs appropriate for gestational age [10th-90th percentile]), (3) prevalence of hypertension and other common comorbidities in persons who did vs did not develop HF, and (4) the association between preterm birth and HF risk among offspring of multiple births. Sensitivity analyses also were performed that (1) used competing risk models to account for death as a competing event, as an alternative to censoring at death, and (2) restricted the main analyses to persons born in 2001 or later when outpatient data were available throughout the duration of follow-up. All statistical tests were 2 sided and used an α level of .05. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp) from March 2020 to October 2020.

Results

We identified a total of 4 201 706 live singleton births. Of these, 8637 births (0.2%) were excluded because they were missing information for gestational age, leaving 4 193 069 births (99.8% of the original cohort) for inclusion in the study (maximum age, 43.0 years; median age, 22.5 years; mean [SD] age, 22.2 [12.2] years). A total of 259 922 individuals (6.2%) were censored at emigration, 1885 (<0.1%) for a diagnosis of IHD, and 41 579 (1.0%) for death.

Table 1 reports perinatal and maternal characteristics by gestational age at birth. Preterm infants were more likely than full-term infants to be male (preterm infants, 114 833 of 210 039 [54.7%]; full-term infants, 1 471 368 of 2 896 444 [50.8%]) or firstborn (preterm, 104 939 [50.0%] vs full-term, 1 219 056 [42.1%]) or have congenital anomalies (eg, patent ductus arteriosus: 236 [0.1%] vs 563 [0.02%]) or a family history of HF (9560 [4.6%] vs 102 454 [3.5%]) or IHD (19 145 [9.1%] vs 227 023 [7.8%]). Mothers of preterm infants vs full-term infants were more likely to be at the extremes of age (eg, <20 years: 8890 [4.2%] vs 84 019 [2.9%]; ≥40 years: 6738 [3.2%] vs 60 198 [2.1%]), be foreign born (eg, another European country, US, or Canada: 17 991 [8.6%] vs 236 119 [8.2%]), smoke (eg, ≥10 cigarettes/day: 12 234 [5.8%] vs 112 716 [3.9%]), or have a low education level (eg, ≤9 years: 33 128 [15.8%] vs 367 829 [12.7%]), high BMI (eg, ≥30.0: 12 974 [6.2%] vs 146 991 [5.1%]), preeclampsia (24 996 [11.9%] vs 94 720 [3.3%]), other hypertensive disorders (3142 [1.5%] vs 24 746 [0.9%]), or diabetes (8039 [3.8%] vs 31 304 [1.1%]).

Table 1. Characteristics of Study Participants by Gestational Age at Birth, Sweden, 1973 Through 2014.

| Characteristic | Individuals, No. (%)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely preterm | Moderately preterm | Late preterm | Early term | Full term | Postterm | |

| Total | 8324 (0.2) | 44 373 (1.1) | 157 342 (3.7) | 740 391 (17.7) | 2 896 444 (69.1) | 346 195 (8.3) |

| Child characteristics | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 4529 (54.4) | 24 734 (55.7) | 85 570 (54.4) | 381 140 (51.5) | 1 471 368 (50.8) | 188 358 (54.4) |

| Female | 3795 (45.6) | 19 639 (44.3) | 71 772 (45.6) | 359 251 (48.5) | 1 425 076 (49.2) | 157 837 (45.6) |

| Fetal growthb | ||||||

| Small for gestational age | 73 (0.9) | 5630 (12.7) | 15 623 (9.9) | 54 405 (7.3) | 276 687 (9.6) | 66 724 (19.3) |

| Appropriate for gestational age | 8015 (96.3) | 37 019 (83.4) | 128 530 (81.7) | 601 039 (81.2) | 2 326 431 (80.3) | 253 586 (73.2) |

| Large for gestational age | 236 (2.8) | 1724 (3.9) | 13 189 (8.4) | 84 947 (11.5) | 293 326 (10.1) | 25 885 (7.5) |

| Birth order | ||||||

| 1 | 4140 (49.7) | 22 780 (51.3) | 78 019 (49.6) | 297 655 (40.2) | 1 219 056 (42.1) | 172 702 (49.9) |

| 2 | 2384 (28.6) | 12 525 (28.2) | 47 050 (29.9) | 271 130 (36.6) | 1 087 624 (37.5) | 111 055 (32.1) |

| ≥3 | 1800 (21.6) | 9068 (20.4) | 32 273 (20.5) | 171 606 (23.2) | 589 764 (20.4) | 62 438 (18.0) |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 75 (0.9) | 79 (0.2) | 82 (<0.1) | 196 (<0.1) | 563 (<0.1) | 77 (<0.1) |

| Other circulatory anomalies | 126 (1.5) | 617 (1.4) | 1179 (0.8) | 3430 (0.5) | 8557 (0.3) | 1100 (0.3) |

| Noncirculatory anomalies | 505 (6.1) | 2598 (5.9) | 7560 (4.8) | 32 759 (4.4) | 128 656 (4.4) | 15 081 (4.4) |

| Family history of heart failure | 244 (2.9) | 2089 (4.7) | 7227 (4.6) | 27 941 (3.8) | 102 454 (3.5) | 15 067 (4.4) |

| Family history of ischemic heart disease | 467 (5.6) | 4058 (9.2) | 14 620 (9.3) | 60 596 (8.2) | 227 023 (7.8) | 32 697 (9.4) |

| Maternal characteristics | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| <20 | 356 (4.3) | 2058 (4.6) | 6476 (4.1) | 22 069 (3.0) | 84 019 (2.9) | 12 962 (3.7) |

| 20-24 | 1575 (18.9) | 8957 (20.2) | 33 190 (21.1) | 139 115 (18.8) | 580 841 (20.0) | 76 287 (22.0) |

| 25-29 | 2436 (29.3) | 13 725 (30.9) | 51 191 (32.5) | 243 257 (32.9) | 1 018 871 (35.2) | 121 285 (35.0) |

| 30-34 | 2271 (27.3) | 11 831 (26.7) | 41 555 (26.4) | 211 859 (28.6) | 821 668 (28.4) | 92 813 (26.8) |

| 35-39 | 1314 (15.8) | 6199 (14.0) | 20 167 (12.8) | 100 963 (13.6) | 330 847 (11.4) | 36 883 (10.7) |

| ≥40 | 372 (4.5) | 1603 (3.6) | 4763 (3.0) | 23 128 (3.1) | 60 198 (2.1) | 5965 (1.7) |

| Education, y | ||||||

| ≤9 | 1401 (16.8) | 7322 (16.5) | 24 405 (15.5) | 104 171 (14.1) | 367 829 (12.7) | 48 594 (14.0) |

| 10-12 | 3920 (47.1) | 21 112 (47.6) | 74 269 (47.2) | 338 702 (45.7) | 1 304 778 (45.0) | 157 018 (45.4) |

| >12 | 3003 (36.1) | 15 939 (35.9) | 58 668 (37.3) | 297 518 (40.2) | 1 223 837 (42.3) | 140 583 (40.6) |

| Birth country or region | ||||||

| Sweden | 6379 (76.6) | 36 271 (81.7) | 130 227 (82.8) | 603 828 (81.6) | 2 424 626 (83.7) | 294 280 (85.0) |

| Another European country, US, or Canada | 873 (10.5) | 3879 (8.7) | 13 239 (8.4) | 62 313 (8.4) | 236 119 (8.2) | 27 999 (8.1) |

| Asia or Oceania | 618 (7.4) | 2548 (5.7) | 9108 (5.8) | 50 443 (6.8) | 150 854 (5.2) | 11 962 (3.5) |

| Africa | 251 (3.0) | 811 (1.8) | 2055 (1.3) | 10 868 (1.5) | 46 094 (1.6) | 8025 (2.3) |

| Latin America | 92 (1.1) | 389 (0.9) | 1522 (1.0) | 8476 (1.1) | 24 158 (0.8) | 2014 (0.6) |

| Other/unknown | 111 (1.3) | 475 (1.1) | 1191 (0.8) | 4463 (0.6) | 14 593 (0.5) | 1915 (0.5) |

| BMI | ||||||

| <18.5 | 140 (1.7) | 1146 (2.6) | 4808 (3.1) | 21 784 (2.9) | 65 600 (2.3) | 4649 (1.3) |

| 18.5-24.9 | 6111 (73.4) | 34 215 (77.1) | 121,37 (77.1) | 567 018 (76.6) | 2 279 549 (78.7) | 275 218 (79.5) |

| 25.0-29.9 | 1456 (17.5) | 6189 (13.9) | 21 663 (13.8) | 107 959 (14.6) | 404 340 (14.0) | 46 600 (13.5) |

| ≥30.0 | 617 (7.4) | 2823 (6.4) | 9534 (6.1) | 43 630 (5.9) | 146 991 (5.1) | 19 728 (5.7) |

| Smoking, cigarettes/d | ||||||

| 0 | 6091 (73.2) | 31 407 (70.8) | 114 671 (72.9) | 565 076 (76.3) | 2 216 387 (76.5) | 247 302 (71.4) |

| 1-9 | 1737 (20.9) | 10 211 (23.0) | 33 688 (21.4) | 138 352 (18.7) | 567 341 (19.6) | 87 934 (25.4) |

| ≥10 | 496 (6.0) | 2755 (6.2) | 8983 (5.7) | 36 963 (5.0) | 112 716 (3.9) | 10 959 (3.2) |

| Preeclampsia | 1032 (12.4) | 7869 (17.7) | 16 095 (10.2) | 39 382 (5.3) | 94 720 (3.3) | 11 833 (3.4) |

| Other hypertensive disorders | 111 (1.3) | 790 (1.8) | 2241 (1.4) | 8897 (1.2) | 24 746 (0.9) | 2347 (0.7) |

| Diabetes | 238 (2.9) | 1650 (3.7) | 6151 (3.9) | 19 121 (2.6) | 31 304 (1.1) | 2260 (0.7) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Preterm birth was defined as any at a gestational age less than 37 weeks; extremely preterm, at 22 to 27 weeks’ gestational age; moderately preterm, at 28 to 33 weeks’ gestational age; late preterm, at 34 to 36 weeks’ gestational age; early term, at 37 to 38 weeks’ gestational age; full term, at 39 to 41 weeks’ gestational age; and postterm, at 42 weeks’ gestational age or more.

Small for gestational age was defined as a weight less than the 10th percentile; appropriate for gestational age, between the 10th and 90th percentiles; and large for gestational age, greater than the 99th percentile.

In 85.0 million person-years of follow-up, 4158 persons (0.1%) were identified as having HF, yielding an overall incidence rate of 4.8 per 100 000 person-years across ages 0 to 43 years. The corresponding incidence rates per 100 000 person-years were 11.5 among those born preterm, 5.8 among those born at early term, and 4.1 among those born at full term (Table 2). The median age for the entire cohort at the end of follow-up was 22.5 years (mean [SD] age, 22.2 [12.2] years), and the median age at diagnosis of HF was 15.4 years (mean [SD] age, 15.5 [14.7] years).

Table 2. Associations Between Gestational Age at Birth and Risk of Heart Failure, Sweden, 1973 Through 2015.

| Characteristica | Cases | Rateb | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Unadjusted risk difference (95% CI)d | Weighted % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjustedc | P value | AFee | PAFf | ||||

| Attained ages 0-43 y | ||||||||

| Preterm | 460 | 11.5 | 2.85 (2.58 to 3.15) | 2.69 (2.43 to 2.97) | <.001 | 7.4 (6.3 to 8.5) | 64.5 | 10.4 |

| Extremely preterm | 45 | 56.0 | 13.96 (10.39 to 18.75) | 12.83 (9.55 to 17.25) | <.001 | 51.9 (35.6 to 68.3) | 92.7 | 1.7 |

| Moderately preterm | 125 | 15.8 | 3.93 (3.28 to 4.70) | 3.65 (3.04 to 4.37) | <.001 | 11.7 (8.9 to 14.5) | 74.2 | 3.7 |

| Late preterm | 290 | 9.2 | 2.30 (2.03 to 2.59) | 2.18 (1.93 to 2.46) | <.001 | 5.2 (4.1 to 6.2) | 55.9 | 6.0 |

| Early term | 829 | 5.8 | 1.45 (1.34 to 1.57) | 1.40 (1.29 to 1.51) | <.001 | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.1) | 29.2 | 7.5 |

| Full term | 2395 | 4.1 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | 0 [Reference] | NA | NA |

| Postterm | 375 | 4.8 | 1.10 (0.99 to 1.23) | 1.13 (1.02 to 1.26) | .03 | 0.7 (0.2 to 1.2) | 14.9 | 2.0 |

| Per additional week (trend) | NA | NA | 0.86 (0.85 to 0.87) | 0.87 (0.86 to 0.88) | <.001 | NA | NA | NA |

| Attained ages <1 y | ||||||||

| Preterm | 233 | 119.6 | 4.69 (4.04 to 5.43) | 4.49 (3.86 to 5.22) | <.001 | 94.1 (78.7 to 109.6) | 78.7 | 19.4 |

| Extremely preterm | 31 | 601.6 | 22.91 (15.99 to 32.83) | 21.03 (14.64 to 30.20) | <.001 | 576.2 (364.4 to 787.9) | 95.8 | 4.0 |

| Moderately preterm | 65 | 164.1 | 6.42 (4.98 to 8.27) | 6.08 (4.70 to 7.86) | <.001 | 138.7 (98.7 to 178.6) | 84.5 | 7.1 |

| Late preterm | 137 | 91.3 | 3.58 (2.98 to 4.30) | 3.47 (2.88 to 4.17) | <.001 | 65.8 (50.4 to 81.2) | 72.1 | 11.6 |

| Early term | 334 | 46.8 | 1.84 (1.61 to 2.09) | 1.76 (1.54 to 2.00) | <.001 | 21.3 (16.0 to 26.7) | 45.6 | 14.5 |

| Full term | 713 | 25.4 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | 0 [Reference] | NA | NA |

| Postterm | 91 | 27.2 | 1.07 (0.86 to 1.33) | 1.11 (0.89 to 1.38) | .35 | 1.7 (−4.2 to 7.6) | 6.3 | 0.7 |

| Per additional week (trend) | NA | NA | 0.81 (0.80 to 0.82) | 0.82 (0.80 to 0.83) | <.001 | NA | NA | NA |

| Attained ages 1-17 y | ||||||||

| Preterm | 99 | 3.9 | 3.41 (2.74 to 4.25) | 3.42 (2.75 to 4.27) | <.001 | 2.8 (2.0 to 3.5) | 70.7 | 13.5 |

| Extremely preterm | 8 | 14.2 | 12.09 (6.00 to 24.33) | 12.81 (6.35 to 25.83) | <.001 | 13.1 (3.2 to 22.9) | 92.0 | 1.7 |

| Moderately preterm | 26 | 5.1 | 4.48 (3.01 to 6.66) | 4.59 (3.08 to 6.84) | <.001 | 4.0 (2.0 to 6.0) | 77.7 | 4.5 |

| Late preterm | 65 | 3.3 | 2.88 (2.22 to 3.74) | 2.88 (2.21 to 3.74) | <.001 | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.0) | 65.3 | 8.7 |

| Early term | 171 | 1.8 | 1.61 (1.35 to 1.93) | 1.60 (1.34 to 1.91) | <.001 | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.0) | 38.2 | 11.0 |

| Full term | 421 | 1.1 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | 0 [Reference] | NA | NA |

| Postterm | 46 | 1.0 | 0.88 (0.65 to 1.20) | 0.87 (0.64 to 1.18) | .36 | −0.1 (−0.5 to 0.2) | 12.5g | 1.4h |

| Per additional week (trend) | NA | NA | 0.84 (0.81 to 0.86) | 0.83 (0.81 to 0.86) | <.001 | NA | NA | NA |

| Attained ages 18-43 y | ||||||||

| Preterm | 128 | 10.0 | 1.56 (1.30 to 1.87) | 1.42 (1.19 to 1.71) | <.001 | 3.4 (1.6 to 5.2) | 34.2 | 3.1 |

| Extremely preterm | 6 | 31.7 | 5.40 (2.42 to 12.05) | 4.72 (2.11 to 10.52) | <.001 | 25.2 (−0.2 to 50.6) | 79.3 | 0.4 |

| Moderately preterm | 34 | 13.8 | 2.16 (1.54 to 3.04) | 1.93 (1.37 to 2.71) | <.001 | 7.2 (2.6 to 11.8) | 52.3 | 1.4 |

| Late preterm | 88 | 8.7 | 1.35 (1.09 to 1.67) | 1.24 (1.00 to 1.54) | .05 | 2.1 (0.2 to 3.9) | 24.1 | 1.6 |

| Early term | 324 | 7.3 | 1.16 (1.02 to 1.31) | 1.09 (0.97 to 1.24) | .15 | 0.7 (−0.2 to 1.6) | 9.6 | 2.0 |

| Full term | 1261 | 6.6 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | 0 [Reference] | NA | NA |

| Postterm | 238 | 8.2 | 1.15 (1.00 to 1.33) | 1.19 (1.04 to 1.37) | .01 | 1.6 (0.5 to 2.7) | 19.9 | 3.2 |

| Per additional week (trend) | NA | NA | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.98) | 0.97 (0.95 to 0.99) | .01 | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: AFe, attributable fraction in the exposed; NA, not applicable; PAF, population-attributable fraction.

Preterm birth was defined as any at a gestational age less than 37 weeks; extremely preterm, at 22 to 27 weeks’ gestational age; moderately preterm, at 28 to 33 weeks’ gestational age; late preterm, at 34 to 36 weeks’ gestational age; early term, at 37 to 38 weeks’ gestational age; full term, at 39 to 41 weeks’ gestational age; and postterm, at 42 weeks’ gestational age or more.

Incidence rate per 100 000 person-years.

Adjusted for child characteristics (birth year, sex, birth order, and family history of heart failure or ischemic heart disease) and maternal characteristics (age, education, birth country, body mass index, smoking, preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders, and diabetes).

Incidence rate difference per 100 000 person-years.

Attributable fraction among the exposed.

Population-attributable fraction.

Prevented fraction among the exposed.

Population-prevented fraction.

Gestational Age at Birth and Risk of HF

Across all attained ages (0-43 years), gestational age at birth was inversely associated with HF risk (Table 2). Each additional week of gestation was associated with a mean 13% lower risk (adjusted HR per additional week, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.86-0.88]). Preterm and early term birth were associated with a nearly 2.7-fold and 1.4-fold risks of HF, respectively, relative to full term (adjusted HRs, 2.69 [95% CI, 2.43-2.97] and 1.40 [95% CI, 1.29-1.51]). Persons born extremely preterm had a nearly 13-fold risk increase (adjusted HR, 12.83 [95% CI, 9.55-17.25]).

Preterm and extremely preterm birth accounted for 7.4 (95% CI, 6.3-8.5) and 51.9 (95% CI, 35.6-68.3) excess HF cases per 100 000 person-years, respectively, in unadjusted risk differences, compared with full-term birth (Table 2). Estimated weighted percentages of 64.5% and 92.7% of HF cases among those born preterm or extremely preterm (the attributable fraction in the exposed) and 10.4% and 1.7% cases in the entire population (the population-attributable fraction) were associated with preterm or extremely preterm birth, respectively (Table 2).

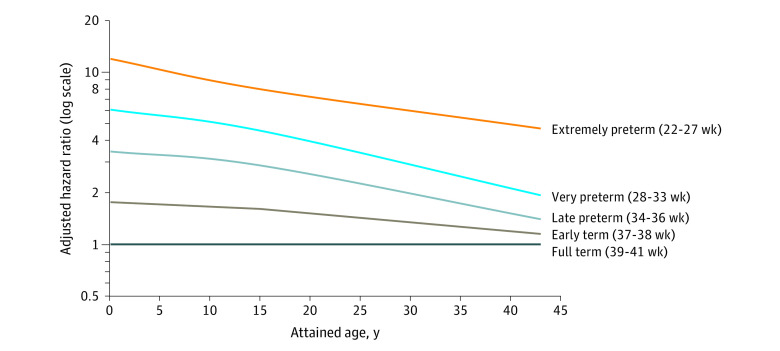

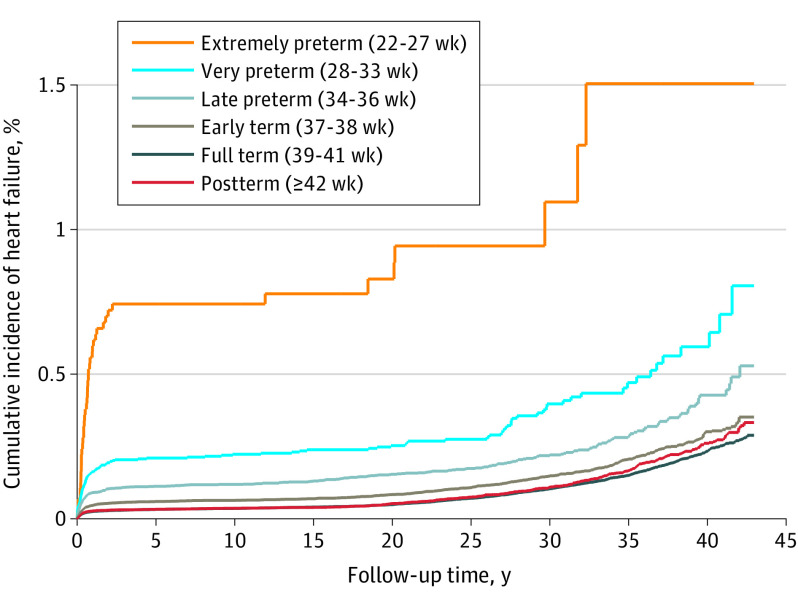

In analyses of narrower age intervals at diagnosis, preterm birth was associated with significantly increased risks of HF at ages younger than 1 year (adjusted HR, 4.49 [95% CI, 3.86-5.22]), 1 to 17 years (3.42 [95% CI, 2.75-4.27]), and 18 to 43 years (1.42 [95% CI, 1.19-1.71]). At ages 18 through 43 years, the HRs further stratified by gestational age were 4.72 (95% CI, 2.11-10.52) for extremely preterm births (22-27 weeks), 1.93 (95% CI, 1.37-2.71) for moderately preterm births (28-33 weeks), 1.24 (95% CI, 1.00-1.54) for late preterm births (34-36 weeks), and 1.09 (95% CI, 0.97-1.24) for early term births (37-38 weeks). The corresponding HF incidence rates (per 100 000 person-years) at ages 18 through 43 years were 31.7, 13.8, 8.7, and 7.3, respectively, compared with 6.6 for full-term births. Figure 1 shows adjusted HRs for HF by attained age for different gestational age groups compared with individuals born at full term. Figure 2 shows the cumulative incidence of HF by attained age for different gestational age groups.

Figure 1. Adjusted Hazard Ratios for Heart Failure by Gestational Age at Birth Compared with Full-term Birth, Sweden, 1973 Through 2015.

Figure 2. Cumulative Incidence of Heart Failure by Gestational Age at Birth, Sweden, 1973 Through 2015.

After excluding all individuals with congenital anomalies (n = 201 302 [4.8% of the total cohort]), the risk estimates were only slightly lower and remained significantly elevated (eTable 2 in the Supplement). For example, among persons born preterm compared with full term, the adjusted HR for HF in individuals younger than 1 year was 4.94 (95% CI, 4.06-6.02); 1 to 17 years, 3.07 (95% CI, 2.34-4.04); and 18 to 43 years, 1.38 (95% CI, 1.14-1.68). Alternatively, adjusting for congenital anomalies also resulted in negligible change in risk estimates.

Interactions between gestational age at birth and sex are shown in eTable 3 of the Supplement. Among persons born full term, HF incidence per 100 000 person-years across ages 0 to 43 years was higher in male participants (4.4) than female participants (3.7). However, the opposite pattern was seen among those born preterm (12.1 per 100 000 person-years in female participants vs 10.9 per 100 000 person-years in male participants). The greater adverse outcome among female participants resulted in a positive multiplicative interaction (ie, the combined outcome of preterm birth and female sex on risk of HF exceeded the product of their separate effects) but with no significant additive interaction. The absence of additive interaction suggests that preterm birth accounted for a similar number of HF cases among male and female individuals.

Cosibling Analyses

A total of 3 530 215 individuals (84.2% of the cohort) had at least 1 sibling and were included in cosibling analyses to control for unmeasured shared familial factors. Compared with the primary analyses, cosibling analyses resulted in similar HRs at ages younger than 18 years but substantially lower HRs that were no longer statistically significant at ages 18 to 43 years (Table 3). For example, comparing preterm with full-term births, the adjusted HRs for HF at ages younger than 1 year were 4.49 (95% CI, 3.86-5.22) in the primary analysis vs 4.41 (95% CI, 3.24-5.99) in the cosibling analysis; at ages 1 to 17 years, 3.42 (95% CI, 2.75-4.27) vs 3.50 (95% CI, 2.25-5.46); and at ages 18 to 43 years, 1.42 (95% CI, 1.19-1.71) vs 1.14 (95% CI, 0.75-1.73). These findings suggest that the observed associations between preterm birth and HF in adulthood (but not childhood or adolescence) might be largely explained by familial factors that are shared determinants of preterm birth and later development of HF. Results of other secondary and sensitivity analyses are reported in eResults and eTables 4 and 5 in the Supplement.

Table 3. Cosibling Analyses of Gestational Age at Birth and Risk of Heart Failure, Sweden, 1973 Through 2015.

| Characteristica | Cases | Hazard ratio (95% CI)b | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attained ages 0-43 y | |||

| Preterm | 362 | 2.92 (2.37-3.60) | <.001 |

| Early term | 674 | 1.36 (1.18-1.55) | <.001 |

| Full term | 1934 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Per additional week | NA | 0.86 (0.83-0.88) | <.001 |

| Attained ages <1 y | |||

| Preterm | 190 | 4.41 (3.24-5.99) | <.001 |

| Early term | 294 | 1.76 (1.42-2.18) | <.001 |

| Full term | 623 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Per additional week | NA | 0.81 (0.78-0.85) | <.001 |

| Attained ages 1-17 y | |||

| Preterm | 82 | 3.50 (2.25-5.46) | <.001 |

| Early term | 145 | 1.56 (1.17-2.09) | <.001 |

| Full term | 360 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Per additional week | NA | 0.80 (0.75-0.86) | <.001 |

| Attained ages 18-43 y | |||

| Preterm | 90 | 1.14 (0.75-1.73) | .54 |

| Early term | 235 | 0.90 (0.71-1.13) | .37 |

| Full term | 951 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Per additional week | NA | 0.99 (0.94-1.05) | .80 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Preterm birth was defined as any at gestational age less than 37 weeks; early term, at 37 to 38 weeks’ gestational age; and full term, 39 to 41 weeks’ gestational age.

Adjusted for shared familial (genetic and/or environmental) factors and additionally for specific child characteristics (birth year, sex, birth order, and family history of heart failure or ischemic heart disease) and maternal characteristics (age, education, birth country, body mass index, smoking, preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders, and diabetes).

Discussion

In this large national cohort study, low gestational age at birth was associated with increased risk of HF from childhood into adulthood. After adjusting for other perinatal and maternal factors, persons born preterm or extremely preterm had more than 2-fold and 12-fold risks of HF, respectively. These risks declined with longer follow-up but remained significantly elevated into early adulthood and mid-adulthood. However, the absolute risks of HF associated with preterm birth were overall low across these ages. At ages 18 to 43 years (but not <18 years), the associations appeared to be largely explained by shared familial determinants of preterm birth and HF.

To our knowledge, this is the largest population-based study of preterm birth in association with HF risks and the first to examine such risks into mid-adulthood or include cosibling analyses. A prior Swedish cohort study27 examined HF risks in 2.6 million persons born in 1987 to 2012, who overlapped with the present cohort, in whom 501 HF cases were identified after follow-up through 2013 (ages 1 to 27 years; median age, 14 years). That study reported strong associations with HF among those born extremely preterm (<28 weeks: adjusted incidence rate ratio, 17.0 [95% CI, 7.96-36.3]) or moderately preterm (28-31 weeks: 3.58 [95% CI, 1.57-8.14]) but not late preterm (32-36 weeks: 1.36 [95% CI, 0.87-2.13]), compared with those born at 37 weeks or later.27 However, HF risks were not examined specifically in adulthood (>18 years), likely because of an insufficient number of cases and statistical power.

The present study extends this evidence by providing population-based risk estimates longitudinally from childhood into mid-adulthood in a cohort of more than 4 million persons with 8-fold as many HF cases. The findings showed that those born preterm or early term had substantially increased risks of HF (>3-fold and 1.6-fold, respectively) at ages 1 to 17 years, compared with those born full term. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report HF risks associated with early term birth (37-38 weeks). The increased risks we found in this subgroup are consistent with previously reported long-term risks of hypertension,16,17 diabetes,18 lipid disorders,19 IHD,20 sleep-disordered breathing,21 chronic kidney disease,37 and premature mortality2,38 associated with early term birth.

In addition, we found that persons born preterm (but not early term) had significantly increased risk of new-onset HF in early adulthood to mid-adulthood (ie, among all persons without an HF diagnosis before adulthood). Preterm and extremely preterm birth were associated with 1.4-fold and 4.7-fold risks, respectively, at ages 18 to 43 years. These risks persisted after excluding individuals with congenital anomalies. However, unlike at ages younger than 18 years, these associations in adulthood appeared to be associated with shared genetic or early-life environmental factors in families.

This study’s findings may be partially mediated by hypertension, diabetes, lipid disorders, IHD, and sleep-disordered breathing, which are known to be associated with preterm birth16,17,18,19,20,21 and are established risk factors for HF.22,23,24,25 Hypertension is one of the strongest known risk factors39 and may contribute to the development of left ventricular hypertrophy even in childhood.40 However, we found relatively low prevalence of hypertension and other associated comorbidities in persons born preterm who later developed HF (eResults in the Supplement), suggesting the presence of other mechanisms. Cardiac remodeling as immature cardiomyocytes adapt to extrauterine conditions may also contribute to dilated cardiomyopathy at early ages.10 Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown that increased myocardial mass following preterm birth occurs in the newborn period.11 A clinical echocardiographic study reported evidence of delayed maturation of the myocardium, left ventricular dysfunction, and greater dependence on atrial contraction in preterm infants.12 Bronchopulmonary dysplasia, a major complication of preterm birth, may also lead to right-sided HF through its effects on pulmonary hypertension.41

The median age of onset for HF in a general population has been reported to be 74 years, but this is recently decreasing.42 Our cosibling analyses suggest that the mechanisms linking preterm birth with HF may differ for early-life HF compared with adult-onset HF. Cardiac imaging studies in young adults have found evidence of cardiac remodeling in those who were born preterm, including increased left ventricular mass13; reduced diastolic myocardial relaxation, right ventricular function, and stroke volume14; and decreased myocardial functional reserve during physiologic stress.15 Additional clinical and genetic studies are needed to identify shared determinants of preterm birth and later development of HF and explore whether they also may be linked with elevated HF risks in family members of persons born preterm. Such studies may eventually reveal new targets for early intervention to prevent both preterm birth and HF.

The findings of the present study may have several clinical implications. Heart failure frequently has a large burden of disease and is associated with high hospitalization rates, health care expenditures, and premature mortality.26 Our findings suggest that individuals born preterm may need long-term clinical follow-up into adulthood for preventive evaluation and monitoring, even among those without known cardiac abnormalities. Preventive actions should include aggressive reduction of modifiable risk factors, including obesity, physical inactivity, smoking, and excessive alcohol use, as well as effective control of blood pressure, glucose, and lipid levels.43,44,45 In patients of all ages, medical records and history-taking should include gestational age at birth to facilitate preventive counseling and monitoring for HF and other long-term sequelae in those born preterm.46,47,48

A key strength of the present study is its large national cohort design with follow-up into adulthood. Availability of highly complete nationwide birth and medical registry data helped minimize potential selection or ascertainment biases. The large sample size also enabled high statistical power and assessment of narrowly defined gestational age groups, including those born at early term, in association with HF risks into adulthood. We were able to control for multiple perinatal and maternal factors and assess the potential influence of unmeasured shared familial factors using cosibling analyses.

Limitations

This study also had several limitations. First, echocardiographic data were unavailable to verify diagnoses or distinguish specific types of HF. However, high positive predictive values for HF (approximately 81%-95%) as well as other major cardiovascular disorders have been reported in Swedish registries.30,31,32 Second, outpatient diagnoses were available only starting in 2001, resulting in underreporting, although a sensitivity analysis suggested that this was unlikely to have resulted in a major change in the risk estimates. Third, information was unavailable during follow-up on lifestyle factors, such as physical activity, diet, obesity, smoking, or alcohol use. These factors may be important modifiers of the association between preterm birth and HF and should be investigated in future studies with access to such data. Lastly, despite up to 43 years of follow-up, this was still a relatively young cohort. Additional follow-up will be needed to examine these associations in older adulthood when HF is more likely to manifest.

Conclusions

In summary, in this large national cohort, we found that persons born preterm had increased risks of new-onset HF from childhood into adulthood. Children and adults born prematurely may need long-term clinical follow-up for risk reduction and monitoring for HF, especially those born at the earliest gestational ages.

eResults. Secondary and sensitivity analyses.

eTable 1. ICD codes used in the analyses.

eTable 2. Associations between gestational age at birth and risk of heart failure after excluding individuals with congenital anomalies, Sweden, 1973-2015.

eTable 3. Interactions between gestational age at birth and sex in relation to risk of heart failure at ages 0-43 years.

eTable 4. Interactions between gestational age at birth and fetal growth in relation to risk of heart failure at ages 0-43 years.

eTable 5. Associations between gestational age at birth and risk of heart failure, accounting for death as a competing event, Sweden, 1973-2015.

References

- 1.Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller AB, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(1):e37-e46. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30451-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crump C, Sundquist J, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K. Gestational age at birth and mortality from infancy into mid-adulthood: a national cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3(6):408-417. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30108-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crump C, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Prevalence of survival without major comorbidities among adults born prematurely. JAMA. 2019;322(16):1580-1588. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.15040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison KM, Ramsingh L, Gunn E, et al. Cardiometabolic health in adults born premature with extremely low birth weight. Pediatrics. 2016;138(4):e20160515. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sipola-Leppänen M, Vääräsmäki M, Tikanmäki M, et al. Cardiometabolic risk factors in young adults who were born preterm. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(11):861-873. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Philip R, Towbin JA, Sathanandam S, et al. Effect of patent ductus arteriosus on the heart in preterm infants. Congenit Heart Dis. 2019;14(1):33-36. doi: 10.1111/chd.12701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benitz WE; Committee on Fetus and Newborn, American Academy of Pediatrics . Patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):e20153730. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanner K, Sabrine N, Wren C. Cardiovascular malformations among preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):e833-e838. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Purisch SE, DeFranco EA, Muglia LJ, Odibo AO, Stamilio DM. Preterm birth in pregnancies complicated by major congenital malformations: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):287.e1-287.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burchert H, Lewandowski AJ. Preterm birth is a novel, independent risk factor for altered cardiac remodeling and early heart failure: is it time for a new cardiomyopathy? Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2019;21(2):8. doi: 10.1007/s11936-019-0712-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox DJ, Bai W, Price AN, Edwards AD, Rueckert D, Groves AM. Ventricular remodeling in preterm infants: computational cardiac magnetic resonance atlasing shows significant early remodeling of the left ventricle. Pediatr Res. 2019;85(6):807-815. doi: 10.1038/s41390-018-0171-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirose A, Khoo NS, Aziz K, et al. Evolution of left ventricular function in the preterm infant. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28(3):302-308. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewandowski AJ, Augustine D, Lamata P, et al. Preterm heart in adult life: cardiovascular magnetic resonance reveals distinct differences in left ventricular mass, geometry, and function. Circulation. 2013;127(2):197-206. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.126920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewandowski AJ, Bradlow WM, Augustine D, et al. Right ventricular systolic dysfunction in young adults born preterm. Circulation. 2013;128(7):713-720. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huckstep OJ, Williamson W, Telles F, et al. Physiological stress elicits impaired left ventricular function in preterm-born adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(12):1347-1356. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.01.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crump C, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Risk of hypertension into adulthood in persons born prematurely: a national cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(16):1542-1550. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Jong F, Monuteaux MC, van Elburg RM, Gillman MW, Belfort MB. Systematic review and meta-analysis of preterm birth and later systolic blood pressure. Hypertension. 2012;59(2):226-234. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.181784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crump C, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Preterm birth and risk of type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a national cohort study. Diabetologia. 2020;63(3):508-518. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-05044-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crump C, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Association of preterm birth with lipid disorders in early adulthood: a Swedish cohort study. PLoS Med. 2019;16(10):e1002947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crump C, Howell EA, Stroustrup A, McLaughlin MA, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Association of preterm birth with risk of ischemic heart disease in adulthood. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(8):736-743. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crump C, Friberg D, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Preterm birth and risk of sleep-disordered breathing from childhood into mid-adulthood. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(6):2039-2049. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunlay SM, Weston SA, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL. Risk factors for heart failure: a population-based case-control study. Am J Med. 2009;122(11):1023-1028. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He J, Ogden LG, Bazzano LA, Vupputuri S, Loria C, Whelton PK. Risk factors for congestive heart failure in US men and women: NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(7):996-1002. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.7.996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folsom AR, Yamagishi K, Hozawa A, Chambless LE; Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study Investigators . Absolute and attributable risks of heart failure incidence in relation to optimal risk factors. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2(1):11-17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.794933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holt A, Bjerre J, Zareini B, et al. Sleep apnea, the risk of developing heart failure, and potential benefits of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(13):e008684. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.008684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ziaeian B, Fonarow GC. Epidemiology and aetiology of heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016;13(6):368-378. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carr H, Cnattingius S, Granath F, Ludvigsson JF, Edstedt Bonamy AK. Preterm birth and risk of heart failure up to early adulthood. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(21):2634-2642. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Statistics Sweden . The Swedish Medical Birth Register. Published April 15, 2020. Accessed June 4, 2020. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/en/statistics-and-data/registers/register-information/the-swedish-medical-birth-register/

- 29.Stock S, Norman J. Preterm and term labour in multiple pregnancies. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;15(6):336-341. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2010.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nilsson AC, Spetz CL, Carsjö K, Nightingale R, Smedby B. [Reliability of the hospital registry. The diagnostic data are better than their reputation]. Lakartidningen. 1994;91(7):598, 603-605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ingelsson E, Arnlöv J, Sundström J, Lind L. The validity of a diagnosis of heart failure in a hospital discharge register. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7(5):787-791. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Wiley; 1987. doi: 10.1002/9780470316696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions (3rd ed.). Wiley; 2003. doi: 10.1002/0471445428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.VanderWeele TJ. Causal interactions in the proportional hazards model. Epidemiology. 2011;22(5):713-717. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31821db503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grambsch PM. Goodness-of-fit and diagnostics for proportional hazards regression models. Cancer Treat Res. 1995;75:95-112. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2009-2_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crump C, Sundquist J, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K. Preterm birth and risk of chronic kidney disease from childhood into mid-adulthood: national cohort study. BMJ. 2019;365:l1346. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crump C, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Winkleby MA. Gestational age at birth and mortality in young adulthood. JAMA. 2011;306(11):1233-1240. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haider AW, Larson MG, Franklin SS, Levy D; Framingham Heart Study . Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and pulse pressure as predictors of risk for congestive heart failure in the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(1):10-16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents . The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2)(Suppl 4th Report):555-576. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.S2.555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansmann G, Sallmon H, Roehr CC, Kourembanas S, Austin ED, Koestenberger M; European Pediatric Pulmonary Vascular Disease Network (EPPVDN) . Pulmonary hypertension in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Res. Published online June 6, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-0993-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Christiansen MN, Køber L, Weeke P, et al. Age-specific trends in incidence, mortality, and comorbidities of heart failure in Denmark, 1995 to 2012. Circulation. 2017;135(13):1214-1223. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aggarwal M, Bozkurt B, Panjrath G, et al. ; American College of Cardiology’s Nutrition and Lifestyle Committee of the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Council . Lifestyle modifications for preventing and treating heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(19):2391-2405. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.2160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Djoussé L, Driver JA, Gaziano JM. Relation between modifiable lifestyle factors and lifetime risk of heart failure. JAMA. 2009;302(4):394-400. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crump C, Sundquist J, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K. Aerobic fitness, muscular strength and obesity in relation to risk of heart failure. Heart. 2017;103(22):1780-1787. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crump C. Medical history taking in adults should include questions about preterm birth. BMJ. 2014;349:g4860. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crump C. Birth history is forever: implications for family medicine. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(1):121-123. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.01.130317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crump C, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Adult outcomes of preterm birth. Prev Med. 2016;91:400-401. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eResults. Secondary and sensitivity analyses.

eTable 1. ICD codes used in the analyses.

eTable 2. Associations between gestational age at birth and risk of heart failure after excluding individuals with congenital anomalies, Sweden, 1973-2015.

eTable 3. Interactions between gestational age at birth and sex in relation to risk of heart failure at ages 0-43 years.

eTable 4. Interactions between gestational age at birth and fetal growth in relation to risk of heart failure at ages 0-43 years.

eTable 5. Associations between gestational age at birth and risk of heart failure, accounting for death as a competing event, Sweden, 1973-2015.