Key Points

Question

What is the prevalence, continuity, and comorbidity of psychiatric disorders among youths during the 15 years after detention in a juvenile justice facility, and do outcomes vary by sex and race/ethnicity?

Findings

In this cohort study of 1829 youths who were detained in a juvenile justice facility, 64% of males and 35% of females with a psychiatric disorder during detention had a disorder 15 years later. Substance use and behavioral disorders were more common among non-Hispanic White youths than Hispanic and Black youths.

Meaning

This study’s findings suggest that persistent psychiatric disorders may complicate the transition from adolescence to adulthood among youths who have been detained in a juvenile justice facility; the pediatric health community should advocate for early identification and treatment of disorders among this population.

Abstract

Importance

Previous studies have found that one-half to three-quarters of youths detained in juvenile justice facilities have 1 or more psychiatric disorders. Little is known about the course of their disorders as they age.

Objective

To examine the prevalence, comorbidity, and continuity of 13 psychiatric disorders among youths detained in a juvenile justice facility during the 15 years after detention up to a median age of 31 years, with a focus on sex and racial/ethnic differences.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The Northwestern Juvenile Project is a longitudinal cohort study of health needs and outcomes of 1829 randomly selected youths in a temporary juvenile detention center in Cook County, Illinois. Youths aged 10 to 18 years were interviewed in detention from November 20, 1995, through June 14, 1998. Participants were reinterviewed up to 12 times during the 15-year study period through February 2015, for a total of 16 372 interviews. The sample was stratified by sex, race/ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic White), age (10-13 years or 14-18 years), and legal status (processed in juvenile or adult court). Data analysis was conducted from February 2014, when data preparation began, to March 2020.

Exposures

Detention in a juvenile justice facility.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Psychiatric disorders, assessed by the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, version 2.3 at the baseline interviews. Follow-up interviews were conducted using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, version IV; the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, version IV; and the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (beginning at the 6-year follow-up interview).

Results

The study included 1829 youths sampled at baseline (1172 males and 657 females; mean [SD] age, 14.9 [1.4] years). Although prevalence and comorbidity of psychiatric disorders decreased as the 1829 participants aged, 52.3% of males and 30.9% of females had at least 1 or more psychiatric disorders 15 years postdetention. Among participants with a disorder at baseline, 64.3% of males and 34.8% of females had a disorder 15 years later. Compared with females, males had 3.37 times the odds of persisting with a psychiatric disorder 15 years after baseline (95% CI, 1.79-6.35). Compared with Black participants and Hispanic participants, non-Hispanic White participants had 1.6 times the odds of behavioral disorders (odds ratio, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.27-1.91 and odds ratio, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.23-2.05, respectively) and greater than 1.3 times the odds of substance use disorders (odds ratio, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.55-2.33 and odds ratio, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.11-1.73, respectively) throughout the follow-up period. Behavioral disorders and substance use disorders were the most prevalent 15 years after detention.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study’s findings suggest that persistent psychiatric disorders may complicate the transition from adolescence to adulthood, which is already challenging for youths involved in the juvenile justice system, many of whom are from racial/ethnic minority groups and low-income backgrounds. The pediatric health community should advocate for early identification and treatment of disorders among youths in the justice system.

This cohort study examines the prevalence, comorbidity, and continuity of psychiatric disorders among youths detained in a juvenile justice facility during the 15 years after detention, with a focus on sex and racial/ethnic differences.

Introduction

Youths involved in the juvenile justice system have a substantially higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders compared with those in the general population,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 with 45% to 66% of males and 45% to 73% of females in the system meeting the criteria for 1 or more psychiatric disorders.2,10,11,12 Anxiety, mood, and behavioral disorders are prevalent.1,2,3,4,6,10,11,13,14 Substance use disorders (SUDs), which are the most common, affect up to 50% of males and 22% to 46% of females.1,2,6,10,11,12,13 Comorbid psychiatric disorders are also common5,8,13,15; 34% of males and 60% of females in juvenile detention facilities have 3 or more disorders.16

Less is known about the course of psychiatric disorders after youths leave detention facilities. Findings have been inconsistent. A 2015 study of 75 first-time juvenile offenders found that the prevalence of disorders had decreased 2 years later from more than 70% to approximately 46%.9 A longitudinal study of 97 males found that 2 years after juvenile detention, mental health problems had persisted; 88%, 73%, and 51% of the sample met criteria for conduct disorder, drug use disorder, and alcohol use disorder, respectively.17 These studies have limitations, including small sample sizes, brief follow-up periods, the inclusion of few females, and the inability to study the Hispanic population, which is now the largest minority group in the US.18 Moreover, the study by Harrington et al17 was conducted in the UK, limiting the generalizability of its findings to populations in the US, which has greater income inequality19 and racial/ethnic diversity.20,21

To date, the largest investigation of youths detained in juvenile justice facilities is the Northwestern Juvenile Project, a study of 1829 youths aged 10 to 18 years.10 This study found that at the time of detention, two-thirds of males and almost three-quarters of females had 1 or more psychiatric disorders.10 Approximately one-half of the youths had comorbid psychiatric disorders.15 Five years later, at a median age of 20 years, more than 50% of males and 40% of females had 1 or more psychiatric disorders.22 Comorbidity remained common, occurring in 27% of males and 14% of females.23

Many psychiatric disorders, such as substance use24,25,26,27 and mood disorders,24,25,28 may begin during young adulthood. However, to our knowledge, no large longitudinal study has explored the prevalence, comorbidity, and continuity of psychiatric disorders among youths detained in a juvenile justice facility as they age into adulthood. This omission is critical. Involvement with the juvenile justice system may impede developmental trajectories by limiting youths’ opportunities to attain normative adult milestones,29,30,31 such as establishing careers, gaining economic and residential independence, and starting families. For youths involved in the juvenile justice system, many of whom are from racial/ethnic minority groups and low-income backgrounds,32,33,34 transitioning from adolescence to young adulthood may be further complicated by psychiatric disorders, which are associated with negative psychosocial outcomes, especially if untreated.35,36,37

The current investigation presents new epidemiologic data from participants in the Northwestern Juvenile Project who were followed up to a median age of 31 years. The study examined 13 psychiatric disorders: major depression, mania, dysthymia, hypomania, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct disorder (CD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), alcohol use disorder, and drug use disorder. Focusing on sex and racial/ethnic differences, we examined the prevalence of psychiatric disorders, including patterns of comorbidity, and the continuity of psychiatric disorders over time.

Methods

For this cohort study, the institutional review boards of Northwestern University, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Illinois Department of Child and Family Services, Cermak Health Services, the Illinois Department of Corrections, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons approved relevant study procedures. Participants signed either an assent form (if younger than 18 years) or a consent form (if 18 years or older). The Northwestern University institutional review board, Cermak Health Services, and the Illinois Department of Corrections also waived parental consent when participants were younger than 18 years, consistent with federal regulations regarding research with minimal risk.38 This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies as applicable.

Sample, Procedures, and Measures

We recruited and interviewed a stratified random sample of 1829 youths at the time of intake to the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center in Chicago, Illinois, between November 20, 1995, and June 14, 1998. The Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center is used for pretrial detention and detention of juvenile offenders sentenced to less than 30 days. To ensure adequate representation of important subgroups, we stratified the sample by sex, race/ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, and other), age (10-13 years or 14-18 years), and legal status (processed in juvenile court or adult court). Face-to-face structured interviews were conducted at the detention center, with most interviews occurring within 2 days of intake. The stratified random sample included 1172 males and 657 females; 1005 were Black (55%), 524 were Hispanic (29%), 296 were non-Hispanic White (16%), and 4 identified as other race/ethnicity (0%). The median age was 15 years (mean [SD], 14.9 [1.4] years).

All participants were reinterviewed up to 12 times during the 15-year study period through February 2015 at approximately 3, 5, 6, 8, 12, 14, and 15 years after the baseline interviews. A random subsample of 997 participants received additional interviews at 3.5 years and 4.0 years after baseline. We received funding to interview the last 800 participants who were enrolled at baseline at 10, 11, and 13 years after baseline. Participants were interviewed regardless of whether they lived in the community or a correctional facility. We conducted 16 372 interviews overall. Additional details are available in eMethods 1 in the Supplement and are published elsewhere.10,15,22,39 For each follow-up interview, we chose the most reliable and valid diagnostic measures that were available in English and Spanish at the time.

Baseline

At baseline, we administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, version 2.3 (DISC-2.3),40,41 which is based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Third Edition Revised) (DSM-III-R), to assess all disorders excluding PTSD. Thirteen months after the study began, we added the PTSD module from the DISC, version IV (DISC-IV), which is based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) (DSM-IV), when available.39 Additional details on baseline diagnostic decisions can be found elsewhere.10,15,39

Follow-up Interviews

At follow-up interviews, we administered the DISC-IV42,43 (child and young adult versions) to assess past-year prevalence for all disorders excluding SUDs; the DISC-IV was used until the 6-year follow-up interview, when most participants had reached age 18 years. Beginning with the 6-year follow-up interview, we administered the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview,44,45 which is based on the DSM-IV, to assess mood and anxiety disorders during the previous year. For ASPD (age ≥18 years only) and SUDs, we administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, version IV (DIS-IV),46,47 which is based on the DSM-IV. Sensitivity analyses indicated that changes in prevalence over time were not associated with changes in measurements (eMethods 1 and eMethods 2 in the Supplement).

Statistical Analysis

We used Stata software, version 12 (StataCorp LLC)48 and StatTag, version 549 for reproducibility. Data analysis was conducted from February 2014, when data preparation began, to March 2020. To generate prevalence estimates and inferential statistics that reflect the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center population, participants were assigned sampling weights, augmented with nonresponse adjustments to account for missing data.50 We used Taylor series linearization to estimate standard errors.51,52 We used α = .05 to assess statistical significance with 2-sided tests as applicable.

Because some participants were, by design, interviewed more frequently, we summarize prevalence at 8 time points: baseline and follow-up interviews corresponding to approximately 3, 5, 6, 8, and 12, 14, and 15 years after baseline. eTable 1 in the Supplement summarizes demographic and retention data; 77% of participants had a 15-year interview. Race/ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, and other) was self-identified; analyses exclude 4 participants who identified as other. eMethods 1 in the Supplement details management of missing data, including multiple imputations for item nonresponse and assessing effects of attrition.

Changes in Prevalence as Youths Age

As in previous analyses of the Northwestern Juvenile Project data,22,53 we used generalized estimating equations54 to fit marginal models examining differences in prevalence of psychiatric disorders by sex and race/ethnicity and changes in prevalence of disorders as youths aged. Models used all available interviews, an average of 9 interviews per person (range, 1-13 interviews per person). Unless otherwise noted, odds ratios (ORs) indicate sex and racial/ethnic differences over time.

Generalized estimating equations models included covariates for sex, race/ethnicity, aging (time since baseline), age at baseline (10–18 years), and legal status at detention. Details of model formulation are in eMethods 1 in the Supplement. For models with significant interactions between sex and aging (Wald P values), we report model-based ORs for sex differences at 3, 5, 6, 8, and 12, 14, and 15 years postdetention. There were no significant interactions between sex and race/ethnicity. We estimated generalized estimating equations models with sampling weights to account for study design.

Models for Continuity of Disorders Over Time

As in previous analyses of the Northwestern Juvenile Project data,23 we examined continuity of disorders over time: did youths with a disorder at baseline have greater odds of having the same (or different) disorders 15 years later compared with youths without the disorder? We used logistic regression: disorder at baseline was the independent variable, and disorder at the 15-year interview was the dependent variable. We estimated separate models for males and females. All models assessing SUDs at follow-up were adjusted for time in corrections because access to substances is restricted in correctional settings.

Results

Prevalence of Disorder as Youths Age

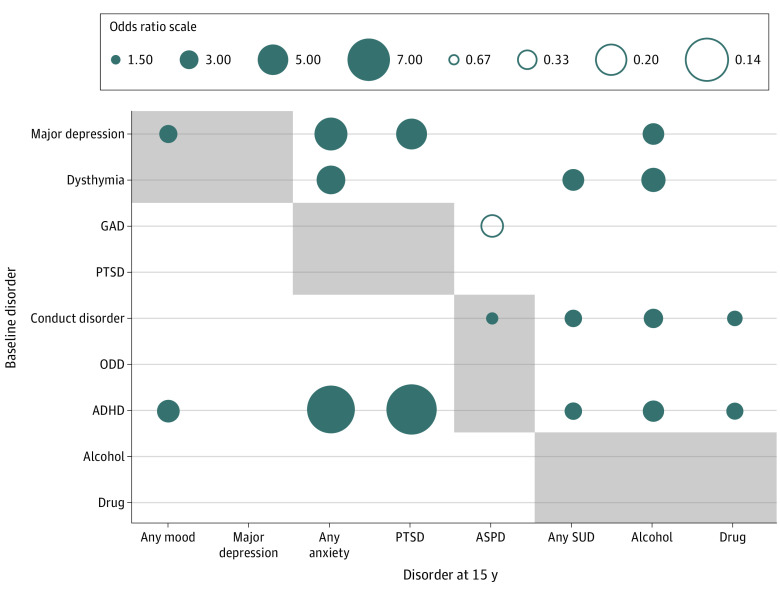

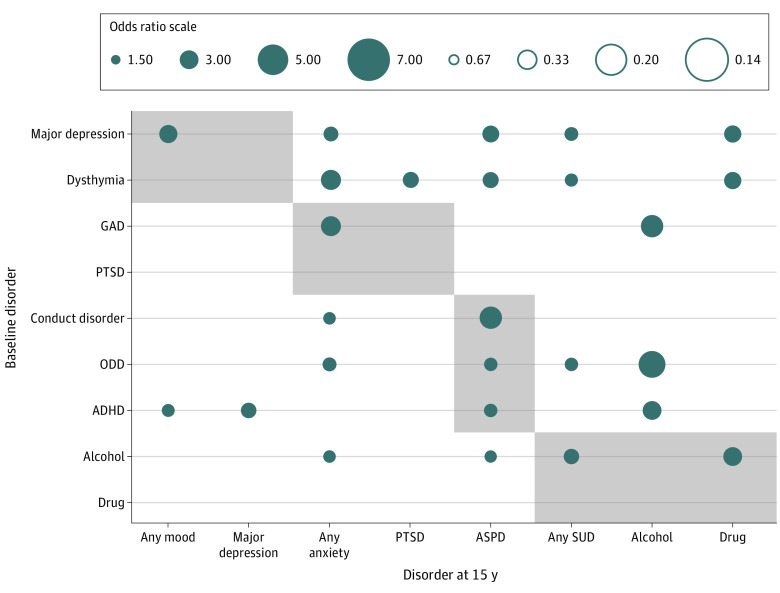

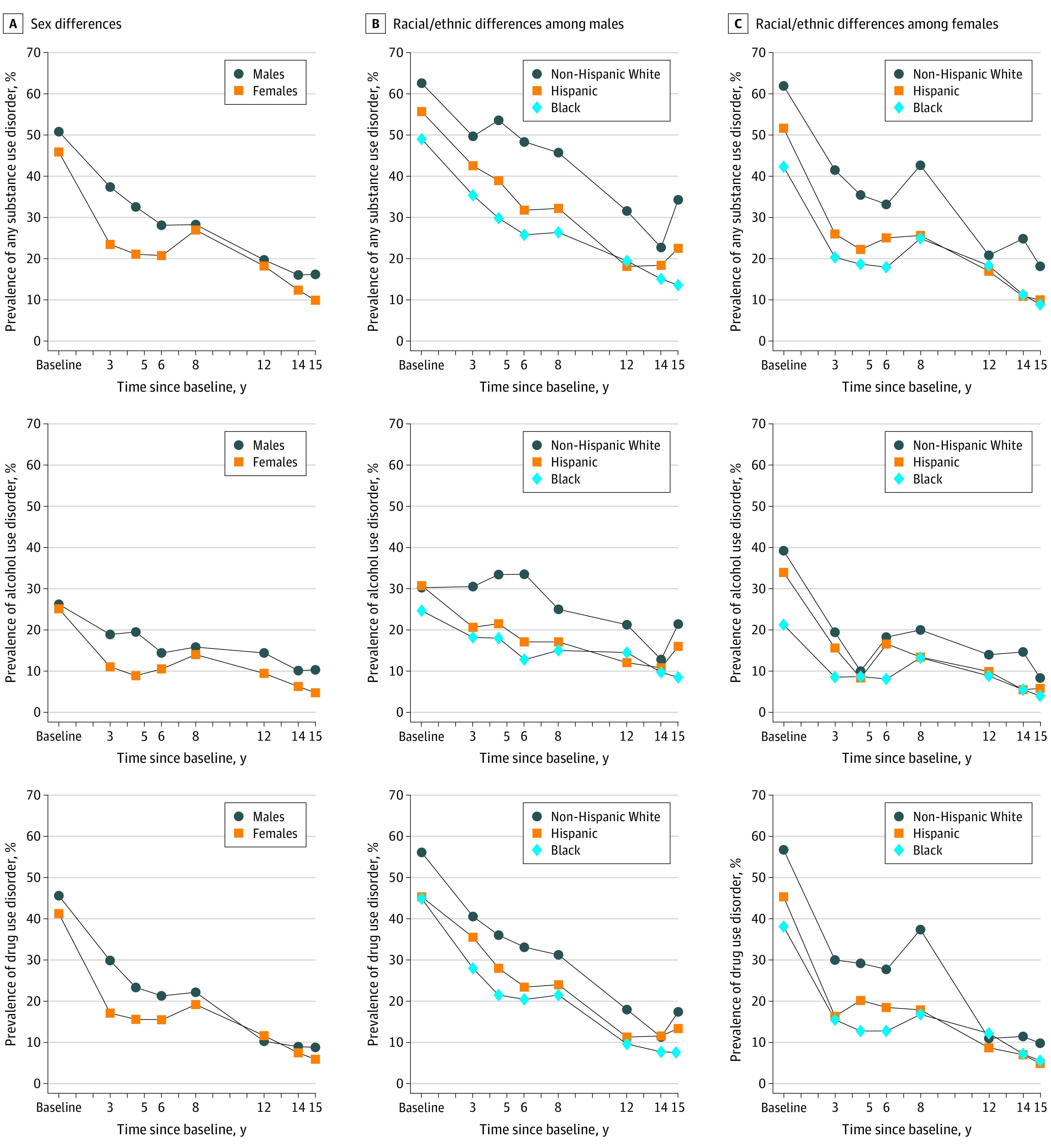

Sex and racial/ethnic differences in prevalence over time are shown in Figure 1 (any disorder), eFigure 1 in the Supplement (comorbid disorder), Figure 2 (mood, anxiety, and behavioral disorders), and Figure 3 (any substance, alcohol, and drug disorders). eTables 2-4 in the Supplement provide specific prevalence estimates. eTables 5-9 in the Supplement show adjusted ORs examining changes in prevalence and sex and racial/ethnic differences as youths age.

Figure 1. Sex and Racial/Ethnic Differences in Prevalence of Any Disorder From Detention (Baseline) to 15 Years After Baseline.

A, A total of 1167 males and 655 females were included. B, A total of 207 non-Hispanic White males, 386 Hispanic males, and 574 Black males were included. C, A total of 89 non-Hispanic White females, 136 Hispanic females, and 430 Black females were included.

Figure 2. Sex and Racial/Ethnic Differences in Prevalence of Mood, Anxiety, and Behavioral Disorders From Detention (Baseline) to 15 Years After Baseline.

A, A total of 1167 males and 655 females were included. B, A total of 207 non-Hispanic White males, 386 Hispanic males, and 574 Black males were included. C, A total of 89 non-Hispanic White females, 136 Hispanic females, and 430 Black females were included.

Figure 3. Sex and Racial/Ethnic Differences in Prevalence of Any Substance, Alcohol, and Drug Use Disorders From Detention (Baseline) to 15 Years After Baseline.

A, A total of 1167 males and 655 females were included. B, A total of 207 non-Hispanic White males, 386 Hispanic males, and 574 Black males were included. C, A total of 89 non-Hispanic White females, 136 Hispanic females, and 430 Black females were included.

Any Disorder

Sex differences

Prevalence decreased as participants aged (Figure 1), although only modestly for males: nearly two-thirds of males (64.5%) had any disorder at baseline, and more than half of males (52.3%) had any disorder 15 years later. In contrast, prevalence among females decreased from 68.4% to 30.9%. At most time points, males had greater odds of disorder than females (eg, 3 years after baseline: adjusted OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.13-1.76; 12 years after baseline: adjusted OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.24-1.97; and 15 years after baseline: adjusted OR, 2.66; 95% CI, 2.08-3.40) (eTable 5 in the Supplement). However, excluding behavioral disorders, patterns over time for males and females were similar (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Racial/ethnic differences

Throughout the follow-up period, non-Hispanic White participants had nearly twice the odds of any disorder compared with Black participants (adjusted OR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.56-2.34) and 1.69 times the odds of Hispanic participants (95% CI, 1.28-2.22). Differences remained even after excluding behavioral disorders (non-Hispanic White vs Black participants: adjusted OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.60-2.40; non-Hispanic White vs Hispanic participants: adjusted OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.11-1.81; and Hispanic vs Black participants: adjusted OR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.09-1.75) (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Comorbid Disorders

Sex differences

Although prevalence decreased as participants aged (eFigure 1 in the Supplement), 15 years after baseline, nearly 1 in 6 males (16.0%) and 1 in 9 females (11.6%) still had comorbid disorders. The rate of decrease was associated with sex (eTable 5 in the Supplement). At 3, 5, and 6 years postdetention, males had greater odds of comorbid disorders than females (respectively, adjusted OR, 1.77, 95% CI, 1.40-2.24; adjusted OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.47-2.22; and adjusted OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.24-1.94).

Racial/ethnic differences

Prevalence of comorbid disorders was highest among non-Hispanic White participants, followed by Hispanic participants and then Black participants (non-Hispanic White vs Black participants: adjusted OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.44-2.17; non-Hispanic White vs Hispanic participants: adjusted OR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.12-1.74; and Hispanic vs Black participants: adjusted OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.02-1.58).

Mood Disorders

Sex differences

Mood disorders generally decreased from baseline to 15 years: among males, from 15.8% to 9.9%; among females, from 21.4% to 7.9% (Figure 2). Overall, females had 1.30 times the odds of any mood disorder (95% CI, 1.06-1.59) and 1.54 times the odds of major depression (95% CI, 1.24-1.92) compared with males (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

Anxiety Disorders

Sex differences

Compared with males, females had 1.66 times the odds of any anxiety disorder (95% CI, 1.33-2.06) and 1.75 times the odds of panic disorder (95% CI, 1.16-2.64) over time. Throughout most follow-up interviews, females also had greater odds of PTSD (the most prevalent anxiety disorder) compared with males (eg, 8 years after baseline, adjusted OR, 3.21; 95% CI, 1.87-5.53) (eTable 7 in the Supplement). PTSD decreased over time, but the rate of decrease was associated with sex.

Racial/ethnic differences

Non-Hispanic White participants were more likely than Black participants to have panic disorder (adjusted OR, 3.00; 95% CI, 1.71-5.27) but less likely to have GAD (adjusted OR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.31-0.93). Hispanic participants were more likely than Black participants and non-Hispanic White participants to have PTSD (respectively, adjusted OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.07-2.19 and adjusted OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.32-2.90). Compared with Black participants, Hispanic participants were also more likely to have any anxiety disorder and panic disorder (respectively, adjusted OR, 1.44: 95% CI, 1.06-1.95 and adjusted OR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.18-3.55).

Behavioral Disorders

Sex differences

Behavioral disorders (including ASPD after age 18 years) were among the most common. For example, 15 years after baseline, 38.6% of males and 14.8% of females had a behavioral disorder. Compared with females, males had more than twice the odds of ASPD (adjusted OR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.89-2.78) (eTable 8 in the Supplement). Approximately 40% of males had ASPD both 5 and 15 years postdetention. For females, prevalence decreased from 26.8% to 14.8% during this period.

Racial/ethnic differences

Compared with Hispanic participants and Black participants, non-Hispanic White participants had 1.6 times the odds of behavioral disorders (respectively, adjusted OR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.23-2.05 and adjusted OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.27-1.91).

Substance Use Disorders

Sex differences

Although prevalence decreased over time, 15 years after baseline, 16.1% of males and 9.9% of females had an SUD. Among males, prevalence of alcohol use and drug use disorders were each approximately 10%; among females, prevalence of each was approximately 5% (Figure 3). After baseline, males had higher prevalence of SUDs than females. For example, 15 years after baseline, males had 2.69 times the odds of alcohol use disorder compared with females (95% CI, 1.71-4.22).

Racial/ethnic differences

Compared with Black participants and Hispanic participants, non-Hispanic White participants had greater than 1.3 times the odds of any SUD (respectively, adjusted OR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.55-2.33 and adjusted OR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.11-1.73), alcohol use disorder (respectively, adjusted OR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.35-2.18 and adjusted OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.12-1.79), and any drug use disorder (respectively, adjusted OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.39-2.10 and adjusted OR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.01-1.57) (eTable 9 in the Supplement). Hispanic participants also had higher prevalence of any SUD and any drug use disorder compared with Black participants (respectively, adjusted OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.11-1.70 and adjusted OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.10-1.69).

Continuity of Disorders Over Time

Among participants who had a disorder at baseline, 64.3% of males and 34.8% of females had a disorder 15 years later. Compared with females, males had 3.37 times the odds of persisting with disorders 15 years after baseline (95% CI, 1.79-6.35). Even after excluding behavioral disorders, males had more than twice the odds of persisting with a disorder (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.06-3.83).

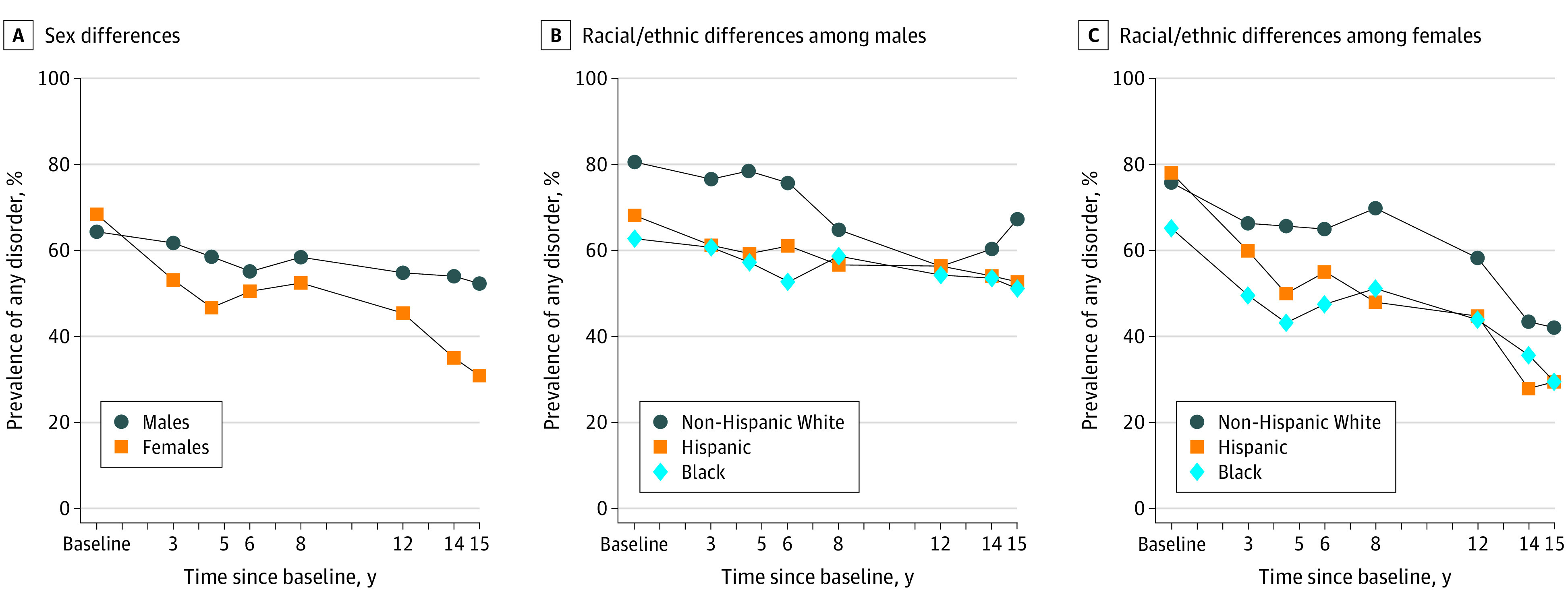

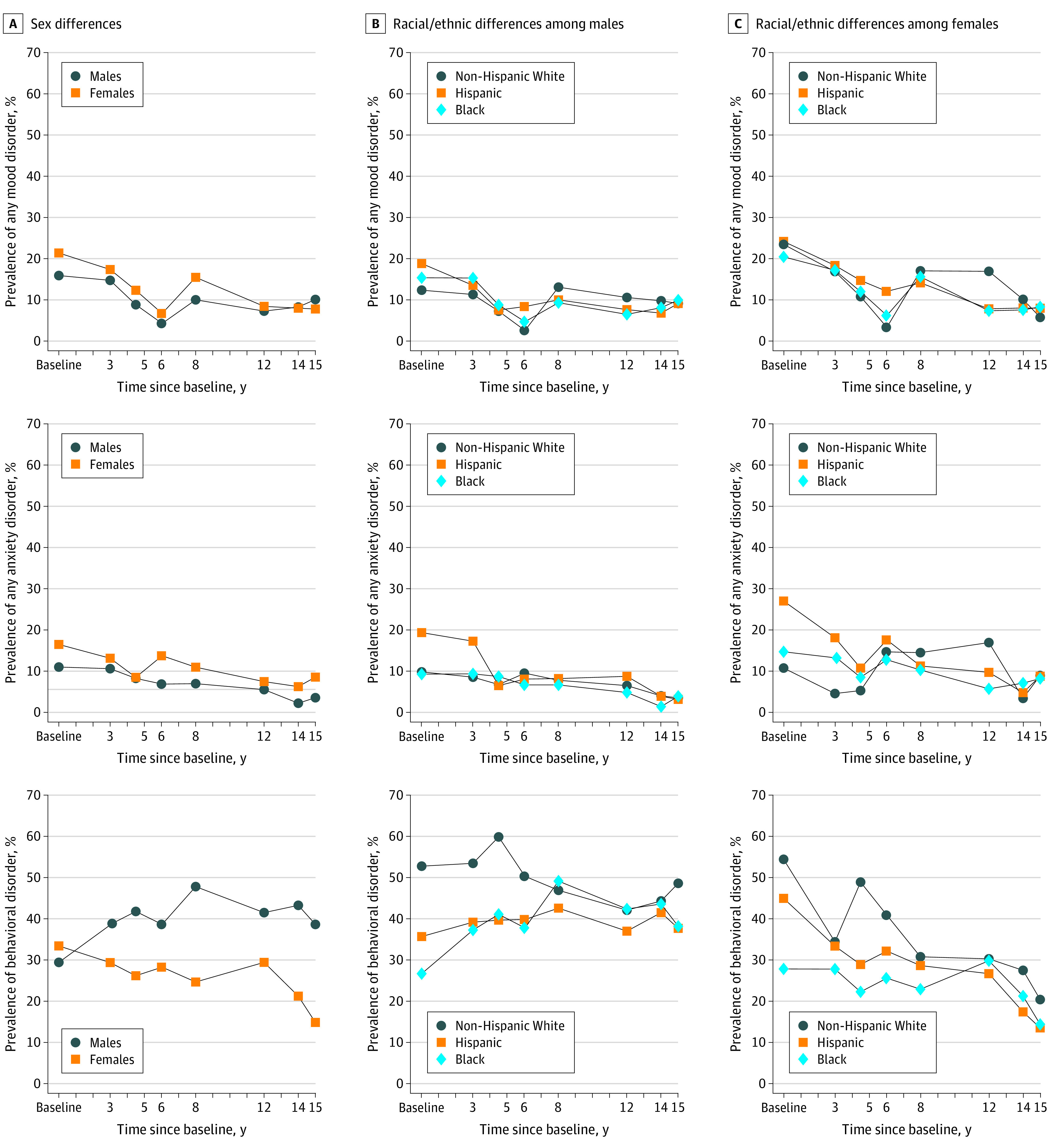

For males and females respectively, Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate associations between having a disorder at detention and 15 years later (either the same or different disorders). eTables 10 and 11 in the Supplement provide specific prevalence estimates and ORs, with and without adjusting for comorbidity at baseline.

Figure 4. Odds Ratios for the Association Between Baseline and 15-Year Diagnoses Among Males.

A total of 837 males were assessed for a disorder at both baseline and at the 15-year follow-up. The disorder diagnosed at baseline could be the same as or different than the disorder diagnosed 15 years later. Only odds ratios with a significance of P < .05 are shown. Filled circles illustrate that participants with the disorder at baseline had higher odds of being diagnosed with the disorder 15 years later. Open circles illustrate that participants with the disorder at baseline had lower odds of being diagnosed with the disorder 15 years later. Shaded boxes represent disorders in the same diagnostic category. ADHD indicates attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASPD, antisocial personality disorder; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; and SUD, substance use disorder.

Figure 5. Odds Ratios for the Association Between Baseline and 15-Year Diagnoses Among Females.

A total of 530 females were assessed for a disorder at both baseline and at the 15-year follow-up. The disorder diagnosed at baseline could be the same as or different than the disorder diagnosed 15 years later. Only odds ratios with a significance of P < .05 are shown. Filled circles illustrate that participants with the disorder at baseline had higher odds of being diagnosed with the disorder 15 years later. Open circles illustrate that participants with the disorder at baseline had lower odds of being diagnosed with the disorder 15 years later. Shaded boxes represent disorders in the same diagnostic category. ADHD indicates attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASPD, antisocial personality disorder; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; and SUD, substance use disorder.

Males

Males with major depression at baseline were more likely to have any mood (OR, 2.88; 95% CI, 1.02-8.16), any anxiety (OR, 5.41; 95% CI, 1.32-22.21), PTSD (OR, 5.07; 95% CI, 1.01-25.46), and alcohol use disorder (OR, 3.49; 95% CI, 1.30-9.37) 15 years later. Males with dysthymia at baseline were more likely to have any anxiety (OR, 4.71; 95% CI, 1.01-21.97), any SUD (OR, 3.36; 95% CI, 1.29-8.71), and alcohol use disorder (OR, 3.98; 95% CI, 1.43-11.06). Baseline ADHD was associated with all disorders 15 years later except for major depression and ASPD. For example, males with ADHD at baseline had 2.78 times the odds of any SUD 15 years later (95% CI, 1.23-6.27). Baseline CD was associated with all externalizing disorders (ASPD and SUDs). For example, males with CD at baseline had 1.96 (95% CI, 1.12-3.42) times the odds of ASPD and 2.44 (95% CI, 1.09-5.45) times the odds of drug use disorder compared with males without CD at baseline. GAD at baseline was associated with lower prevalence of ASPD 15 years later (OR, 0.27 95% CI, 0.09-0.82).

Females

Major depression and dysthymia were associated with many disorders 15 years later (eg, major depression with any anxiety: OR, 2.39; 95% CI, 1.20-4.74; major depression with any SUD: OR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.18-4.23). Females with GAD at baseline were more likely to have any anxiety and alcohol use disorders 15 years later (respectively, OR, 3.17; 95% CI, 1.22-8.25 and OR, 3.62; 95% CI, 1.12-11.75). Conduct disorder, ODD, and ADHD at baseline were associated with ASPD 15 years later (respectively, OR, 3.58; 95% CI, 2,14-6.00; OR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.14-3.62; and OR, 2.11, 95% CI, 1.19-3.74) but were inconsistently associated with other disorders. Alcohol use disorder at baseline was associated with several disorders at follow-up (eg, with ASPD: OR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.17-3.36); drug use disorder was not.

Discussion

Many psychiatric disorders extend well past adolescence. Among participants who had a disorder at baseline, nearly two-thirds of males and more than one-third of females had a disorder 15 years later. As was true for youths in detention10 and 5 years later,22 behavioral disorders and SUDs were the most prevalent, followed by mood and anxiety disorders. Prevalence of several disorders, such as PTSD,55 drug use disorders,55 and ASPD,55,56,57 was notably higher than the general population. Comorbidity was less prevalent 15 years after detention than at baseline and 5 years23 but nevertheless problematic.

There were significant sex and racial/ethnic differences. At detention, approximately two-thirds of males and females had psychiatric disorders. As they aged, males fared worse than females: 15 years after detention, more than half of males had a disorder compared with less than one-third of females. Males had more than 3 times the odds of persisting with disorders 15 years after detention. In addition, males had higher prevalence of ASPD and SUDs as they aged. Females may fare better than males because they are more likely to have adolescent-limited trajectories of offending.58,59,60 Moreover, as they age, females are more likely to engage in prosocial activities and relationships61 and to seek62 and receive63 mental health services.

Racial/ethnic differences persisted as youths aged. Significantly more non-Hispanic White participants had substance use and behavioral disorders than Hispanic participants and Black participants at baseline and in adulthood, similar to the general population.64,65,66,67 Because individuals who are from racial/ethnic minority groups are disproportionately incarcerated,68,69,70 we had anticipated finding differences in the opposite direction, that is, greater prevalence in racial/ethnic minority groups. Our findings may indicate the selective enforcement of laws in minority communities.71,72,73

We found substantial continuity of disorders over time. We also found multiple pathways to addiction: several disorders at baseline (median age, 15 years), including depressive and behavioral disorders, were associated with SUD 15 years later. In addition, depression during childhood was a powerful predictor linked to many disorders in adulthood. Males with depressive disorder at baseline were more likely than those without to have mood, anxiety, and alcohol use disorders 15 years later. Females with depressive disorders at baseline were more likely than those without to have nearly all disorders.

Limitations

This study has limitations. We changed some diagnostic measures as participants aged and as the DSM was updated. Our data are subject to the limitations of self-reporting. Generalizability may be limited to detained youths in urban centers with similar demographic characteristics. Participants may have denied symptoms to hasten the interview; actual prevalence rates may be higher. Although retention rates were high, participants who missed interviews may have been more likely to have disorders. Findings do not take into account mental health services that have been provided.

Implications

First, educate pediatricians that disruptive behavior disorders (such as oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder) are serious but treatable. Up to 25% of children and adolescents seen in primary care have a significant behavioral or emotional health problem.8,74,75,76,77 By facilitating early detection and referral, pediatricians can play a critical role in reducing the likelihood of youths entering the juvenile justice system. Several promising evidence-based interventions are available. For young children, treatments include Parent Management Training and Parent–Child Interaction Therapy.78 For older children, including those in the juvenile justice system, the Coping Power Program79 and Multisystemic Therapy80 can reduce aggressive behaviors. Treatments are most effective when they include youth, parents or caregivers, and other key stakeholders (eg, schools). The most effective pediatric integrated mental health care models include population-based care (identifying, treating, and tracking outcomes of all patients), measurement-based care (validated assessment tools to identify patients and evaluate outcomes), and evidence-based mental health services.81 Juvenile justice is the system of last resort.

Second, researchers should investigate variables that predict the desistance of psychiatric disorders, focusing on high-risk populations. Most of the participants in this study were at risk for continued psychiatric disorders. Yet, risk does not convey certainty. Why do some high-risk youths improve despite limited access to quality care,82 meager social networks,61 and few environmental resources?83 Which characteristics of mental health services, family systems, schools, and communities increase resilience? Studies of the highest-risk populations (eg, youths in the juvenile justice and child welfare systems) will inform intervention for those most in need.

Third, the public health system must expand mental health services for youths while they are involved in the juvenile justice system and when they return to the community. Trauma, loss, and maltreatment, which are common precipitants of depression and other disorders, are prevalent in juvenile justice youth: more than 90% report experiencing at least 1 traumatic event,39,84 including loss of intimates,85 childhood maltreatment,84,86 and witnessing violence.39,84 Treating disorders during childhood may reduce psychiatric morbidity as youths age. Yet, despite decades of research documenting the prevalence of psychiatric disorders,2,10,22,87,88 only approximately one-third of youths are referred for or receive any mental health service during or after detention.9,89,90,91 Logistic challenges abound: short stays,92 insufficient resources93,94 and time to provide evidence-based assessments and treatments,95 lack of coordination among service agencies,96,97 and engagement of families.98,99

Federal law prohibits Medicaid from funding services in public institutions, such as correctional facilities, except for off-site hospitalizations of more than 24 hours.100,101 Quality of services thus vary by an institution’s budget. Moreover, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, which insures nearly 10 million of the 45 million children who receive medical coverage through public programs,102 terminates benefits for incarcerated youth,100,103 as do qualified health plans through the health insurance marketplaces.104 Consequently, families must endure the bureaucratic delay of re-enrollment when youths return home.105 The SUPPORT Act (Public Law No. 115-271), passed in 2018, may improve this situation. It prohibits termination of Medicaid eligibility for juveniles “who are inmates of public institutions.”106 We must continue to advocate for the positions set forth by the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics that state and county medical societies help provide necessary medical services to incarcerated youth107; that Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and private insurance be available for all incarcerated youths without suspension or termination108; and that youths without insurance coverage before incarceration be automatically eligible for Medicaid if incarcerated.109

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (still in force as of this writing) mandates that mental health and substance abuse services be included in insurance plans and considered central components of medical intervention.110,111,112 Nevertheless, the most significant barrier remains: access to high-quality treatment and health care professionals at all stages of the juvenile justice system. The challenge for the pediatric health community is to implement needed changes. We must increase the number of pediatric health care professionals who can implement evidence-based treatments and are willing to provide services to low-income families. Integrated mental health care models are among the most promising, especially if they include the components now known to be most effective.81 We must continue to expand the availability of innovative treatments (eg, telehealth options) useful for patients who are unable to access services because of illness, lack of mobility, or distance from available care.113,114 In addition, we must increase funding to expand services that are accessible to at-risk youth, thereby reducing the likelihood that children will fall between the cracks of inadequate mental health service systems into the juvenile justice net.

Conclusions

Persistent psychiatric disorders may complicate the transition from adolescence to adulthood, which is already challenging for youths in the juvenile justice system, many of whom are from racial/ethnic minority groups and low-income backgrounds. The pediatric health community must advocate for early identification and treatment of disorders among youths involved in the juvenile justice system.

eMethods 1. Expanded Notes on Study Methods

eMethods 2. Maximizing Comparability Among Measures: Changes to Scoring Algorithms for Testing Results

eTable 1. Demographic Characteristics and Retention of the Sample Recruited from the Cook County Juvenile Detention Center Between 1995 and 1998

eTable 2. Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders Over Time: Sex Differences

eTable 3. Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders Over Time: Racial/Ethnic Differences Among Males

eTable 4. Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders Over Time: Racial/Ethnic Differences Among Females

eTable 5. Odds Ratios Describing Demographic Differences in the Prevalence of Selected Psychiatric Disorders From Detention (Baseline) Through the 15-Year Time Point

eTable 6. Odds Ratios Describing Demographic Differences in the Prevalence of Selected Psychiatric Disorders from Detention (Baseline) Through the 15-Year Time Point

eTable 7. Odds Ratios Describing Demographic Differences in the Prevalence of Selected Psychiatric Disorders From Detention (Baseline) Through the 15-Year Time Point

eTable 8. Odds Ratios Describing Demographic Differences in the Prevalence of Selected Psychiatric Disorders From Detention (Baseline) Through the 15-Year Time Point

eTable 9. Odds Ratios Describing Demographic Differences in the Prevalence of Selected Psychiatric Disorders From Detention (Baseline) Through the 15-Year Time Point

eTable 10. 15-Year DSM-IV Diagnoses Predicted From Baseline Diagnoses Among Males

eTable 11. 15-Year DSM-IV Diagnoses Predicted From Baseline Diagnoses Among Females

eFigure 1. Prevalence of Comorbid Disorder in Delinquent Youth From Detention (Baseline) to 15 Years Postbaseline: Sex and Racial/Ethnic Differences

eFigure 2. Prevalence of Any Disorder (Excluding Behavioral Disorders) in Delinquent Youth From Detention (Baseline) to 15 Years Postbaseline: Sex and Racial/Ethnic Differences

eReferences

References

- 1.Domalanta DD, Risser WL, Roberts RE, Risser JM. Prevalence of depression and other psychiatric disorders among incarcerated youths. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(4):477-484. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046819.95464.0B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duclos CW, Beals J, Novins DK, Martin C, Jewett CS, Manson SM. Prevalence of common psychiatric disorders among American Indian adolescent detainees. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(8):866-873. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199808000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eppright TD, Kashani JH, Robison BD, Reid JC. Comorbidity of conduct disorder and personality disorders in an incarcerated juvenile population. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(8):1233-1236. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.8.1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fazel S, Doll H, Långström N. Mental disorders among adolescents in juvenile detention and correctional facilities: a systematic review and metaregression analysis of 25 surveys. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(9):1010-1019. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31817eecf3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karnik NS, Soller M, Redlich A, et al. Prevalence of and gender differences in psychiatric disorders among juvenile delinquents incarcerated for nine months. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(6):838-841. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.6.838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wasserman GA, McReynolds LS, Lucas CP, Fisher P, Santos L. The voice DISC-IV with incarcerated male youths: prevalence of disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(3):314-321. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200203000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mallett CA. Disparate juvenile court outcomes for disabled delinquent youth: a social work call to action. Child Adolesc Social Work J. 2009;26(3):197-207. doi: 10.1007/s10560-009-0168-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson KC, Morris RJ. Mental health disorders. In: Juvenile Delinquency and Disability: Advancing Responsible Adolescent Development. Springer; 2016:153-161. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-29343-1_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burke JD, Mulvey EP, Schubert CA. Prevalence of mental health problems and service use among first-time juvenile offenders. J Child Fam Stud. 2015;24(12):3774-3781. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0185-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK, Mericle AA. Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(12):1133-1143. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wasserman GA, McReynolds LS, Ko SJ, Katz LM, Carpenter JR. Gender differences in psychiatric disorders at juvenile probation intake. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(1):131-137. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.024737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shufelt JL, Cocozza JJ. Youth With Mental Health Disorders in the Juvenile Justice System: Results From a Multi-State Prevalence Study. National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wasserman GA, McReynolds LS, Craig SS, Keating JM, Jones SA. Psychiatric disorder, comorbidity, and suicidal behavior in juvenile justice youth. Crim Justice Behav. 2010;37(12):1361-1376. doi: 10.1177/0093854810382751 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakefield SM, Baronia R, Brennan S. Depression in justice-involved youth. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2019;28(3):327-336. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2019.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abram KM, Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(11):1097-1108. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drerup LC, Croysdale A, Hoffmann NG. Patterns of behavioral health conditions among adolescents in a juvenile justice system. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2008;39(2):122. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.2.122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrington RC, Kroll L, Rothwell J, McCarthy K, Bradley D, Bailey S. Psychosocial needs of boys in secure care for serious or persistent offending. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(8):859-866. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00388.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Census Bureau . American Community Survey 2019. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=HISPANIC%20OR%20LATINO%20ORIGIN%20BY%20RACE&t=Hispanic%20or%20Latino&tid=ACSDT1Y2019.B03002&hidePreview=false

- 19.Dorling D. Income inequality in the UK: comparisons with five large Western European countries and the USA. Appl Geogr. 2015;61:24-34. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2015.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Office for National Statistics . 2011 Census: Population Estimates for the United Kingdom. Updated December 17, 2012. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/2011censuspopulationestimatesfortheunitedkingdom/2012-12-17

- 21.US Census Bureau . Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex, Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States and States: April 1, 2010. to July 1, 2015 2016. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2018/estimates-characteristics.html

- 22.Teplin LA, Welty LJ, Abram KM, Dulcan MK, Washburn JJ. Prevalence and persistence of psychiatric disorders in youth after detention: a prospective longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(10):1031-1043. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abram KM, Zwecker NA, Welty LJ, Hershfield JA, Dulcan MK, Teplin LA. Comorbidity and continuity of psychiatric disorders in youth after detention: a prospective longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(1):84-93. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustün TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(4):359-364. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King KM, Chassin L. A prospective study of the effects of age of initiation of alcohol and drug use on young adult substance dependence. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68(2):256-265. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winters KC, Lee C-YS. Likelihood of developing an alcohol and cannabis use disorder during youth: association with recent use and age. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92(1-3):239-247. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellivier F, Etain B, Malafosse A, et al. Age at onset in bipolar I affective disorder in the USA and Europe. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2014;15(5):369-376. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.639801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dmitrieva J, Monahan KC, Cauffman E, Steinberg L. Arrested development: the effects of incarceration on the development of psychosocial maturity. Dev Psychopathol. 2012;24(3):1073-1090. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Massoglia M, Uggen C. Settling down and aging out: toward an interactionist theory of desistance and the transition to adulthood. AJS. 2010;116(2):543-582. doi: 10.1086/653835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abram KM, Azores-Gococo NM, Emanuel KM, et al. Sex and racial/ethnic differences in positive outcomes in delinquent youth after detention: a 12-year longitudinal study. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(2):123-132. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sedlak AJ, Bruce C. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Youth's Characteristics and Backgrounds: Findings From the Survey of Youth in Residential Placement. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armour J, Hammond S. Minority youth in the juvenile justice system: disproportionate minority contact. Paper presented at: National Conference of State Legislatures; July 2009; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rovner J. Policy brief: racial disparities in youth commitments and arrests. The Sentencing Project. Published April 1, 2016. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://www.sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Racial-Disparities-in-Youth-Commitments-and-Arrests.pdf

- 35.Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Hiripi E, et al. The prevalence of treated and untreated mental disorders in five countries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;22(3):122-133. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessler RC, Foster CL, Saunders WB, Stang PE. Social consequences of psychiatric disorders, I: educational attainment. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(7):1026-1032. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kessler RC, Walters EE, Forthofer MS. The social consequences of psychiatric disorders, III: probability of marital stability. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(8):1092-1096. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Federal policy for the protection of human subjects. Fed Regist. 1991;56(117):28001-28032. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sites/default/files/ohrp/policy/frcomrul.pdf [PubMed]

- 39.Abram KM, Teplin LA, Charles DR, Longworth SL, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK. Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(4):403-410. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK, et al. The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(7):865-877. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwab-Stone ME, Shaffer D, Dulcan MK, et al. Criterion validity of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(7):878-888. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas C. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC). In: Hilsenroth MJ, Segal DL, eds. Comprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment. Vol 2. John Wiley & Sons; 2003:256-270. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):28-38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, et al. ; WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium . Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291(21):2581-2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wittchen HU. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO–Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28(1):57-84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Compton WM, Cottler LB. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS). In: Hilsenroth M, Segal DL, eds. Comprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment. Vol 2. John Wiley & Sons; 2004:153-162. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robins LN, Cottler LB, Bucholz KK, Compton WM. Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (DIS-IV). Washington University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stata Statistical Software. Release 12. StataCorp LP; 2011.

- 49.Welty LJ, Rasmussen LV, Baldridge AS, Whitley EW. Facilitating reproducible research through direct connection of data analysis with manuscript preparation: StatTag for connecting statistical software to Microsoft Word. JAMIA Open. 2020;3(3):342-358. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooaa043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Korn E, Graubard B. Analysis of Health Surveys. John Wiley & Sons; 1999. doi: 10.1002/9781118032619 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cochran WG. Sampling Techniques. John Wiley & Sons; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levy PS, Lemeshow S. Sampling of Populations: Methods and Applications. John Wiley & Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Welty LJ, Harrison AJ, Abram KM, et al. Health disparities in drug- and alcohol-use disorders: a 12-year longitudinal study of youths after detention. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(5):872-880. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.303032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121-130. doi: 10.2307/2531248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karg RS, Bose J, Batts KR, et al. Past Year Mental Disorders Among Adults in the United States: Results From the 2008–2012 Mental Health Surveillance Study. CBHSQ Data Review. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(6):553-564. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trull TJ, Jahng S, Tomko RL, Wood PK, Sher KJ. Revised NESARC personality disorder diagnoses: gender, prevalence, and comorbidity with substance dependence disorders. J Pers Disord. 2010;24(4):412-426. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2010.24.4.412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Male and female offending trajectories. Dev Psychopathol. 2002;14(1):159-177. doi: 10.1017/S0954579402001098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miller S, Malone PS, Dodge KA; Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group . Developmental trajectories of boys’ and girls’ delinquency: sex differences and links to later adolescent outcomes. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38(7):1021-1032. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9430-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Odgers CL, Moffitt TE, Broadbent JM, et al. Female and male antisocial trajectories: from childhood origins to adult outcomes. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20(2):673-716. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zwecker NA, Harrison AJ, Welty LJ, Teplin LA, Abram KM. Social support networks among delinquent youth: an 8-year follow-up study. J Offender Rehabil. 2018;57(7):459-480. doi: 10.1080/10509674.2018.1523821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fields D, Abrams LS. Gender differences in the perceived needs and barriers of youth offenders preparing for community reentry. Child Youth Care Forum. 2010;39(4):253-269. doi: 10.1007/s10566-010-9102-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lopez-Williams A, Stoep AV, Kuo E, Stewart DG. Predictors of mental health service enrollment among juvenile offenders. Youth Violence Juv Justice. 2006;4(3):266-280. doi: 10.1177/1541204006290159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, et al. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(4):372-380. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980-989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vilsaint CL, NeMoyer A, Fillbrunn M, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in 12-month prevalence and persistence of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders: variation by nativity and socioeconomic status. Compr Psychiatry. 2019;89:52-60. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Kendler KS, Su M, Williams D, Kessler RC. Specifying race-ethnic differences in risk for psychiatric disorder in a USA national sample. Psychol Med. 2006;36(1):57-68. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carson EA. Prisoners in 2019. US Dept of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Publication NCJ 255115. Published October 2020. Accessed December 1, 2020. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p19.pdf

- 69.US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics . Jail inmates in 2018. NCJ 253044. Published March 2020. Accessed December 1, 2020. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ji18.pdf

- 70.Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention . OJJDP Statistical briefing book. US Dept of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Published April 23, 2019. Accessed December 1, 2020. https://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/special_topics/qa11802.asp?qaDate=2017

- 71.Weatherspoon F. Ending racial profiling of African-Americans in the selective enforcement of laws: in search of viable remedies. Univ Pittsbg Law Rev. 2004;65(4):721-761. doi: 10.5195/LAWREVIEW.2004.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nowacki JS. Race, ethnicity, and judicial discretion: the influence of the United States v. Booker decision. Crime Delinq. 2013;61(10):1360-1385. doi: 10.1177/0011128712470990 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baradaran S. Race, prediction, and discretion. George Washington Law Rev. 2013;81(1):157-222. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Williams J, Klinepeter K, Palmes G, Pulley A, Foy JM. Diagnosis and treatment of behavioral health disorders in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):601-606. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Costello EJ, Edelbrock C, Costello AJ, Dulcan MK, Burns BJ, Brent D. Psychopathology in pediatric primary care: the new hidden morbidity. Pediatrics. 1988;82(3, pt 2):415-424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cassidy LJ, Jellinek MS. Approaches to recognition and management of childhood psychiatric disorders in pediatric primary care. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1998;45(5):1037-1052. doi: 10.1016/S0031-3955(05)70061-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cooper S, Valleley RJ, Polaha J, Begeny J, Evans JH. Running out of time: physician management of behavioral health concerns in rural pediatric primary care. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):e132-e138. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zisser-Nathenson AR, Herschell AD, Eyberg SM. Parent–child interaction therapy and the treatment of disruptive behavior disorders. In: Weisz JR, Kazdin AE, eds. Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; 2017:103. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Powell NP, Lochman JE, Boxmeyer CL, Barry TD, Pardini DA. The coping power program for aggressive behavior in children. In: Weisz JR, Kazdin AE, eds. Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; 2017:159-176. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Henggeler SW, Schaeffer CM. Treating serious antisocial behavior using multisystemic therapy. In: Weisz JR, Kazdin AE, eds. Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; 2017:197-214. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yonek J, Lee CM, Harrison A, Mangurian C, Tolou-Shams M. Key components of effective pediatric integrated mental health care models: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(5):487-498. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.O’Neill SC, Strnadová I, Cumming T. Systems barriers to community re-entry for incarcerated youths: a review. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2017;79(C):29-36. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.05.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Abrams LS, Freisthler B. A spatial analysis of risks and resources for reentry youth in Los Angeles county. J Soc Social Work Res. 2010;1(1):41-55. doi: 10.5243/jsswr.2010.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dierkhising CB, Ko SJ, Woods-Jaeger B, Briggs EC, Lee R, Pynoos RS. Trauma histories among justice-involved youth: findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2013;4(1):20274. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.20274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Harnisher JL, Abram K, Washburn J, Stokes M, Azores-Gococo N, Teplin L. Loss due to death and its association with mental disorders in juvenile detainees. Juv Fam Court J. 2015;66(3):1-18. doi: 10.1111/jfcj.12029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.King DC, Abram KM, Romero EG, Washburn JJ, Welty LJ, Teplin LA. Childhood maltreatment and psychiatric disorders among detained youths. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(12):1430-1438. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.004412010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wasserman GA, Ko SJ, McReynolds LS. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Assessing the Mental Health Status of Youth in Juvenile Justice Settings. US Dept of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Published August 2004. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/202713.pdf

- 88.McManus M, Alessi NE, Grapentine WL, Brickman A. Psychiatric disturbance in serious delinquents. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1984;23(5):602-615. doi: 10.1016/S0002-7138(09)60354-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.White LM, Aalsma MC, Salyers MP, et al. Behavioral health service utilization among detained adolescents: a meta-analysis of prevalence and potential moderators. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(6):700-708. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yonek JC, Dauria EF, Kemp K, Koinis-Mitchell D, Marshall BDL, Tolou-Shams M. Factors associated with use of mental health and substance use treatment services by justice-involved youths. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(7):586-595. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, Washburn JJ, Pikus AK. Detecting mental disorder in juvenile detainees: who receives services. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(10):1773-1780. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.067819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kumm S, Maggin D, Brown C, Talbott E. A meta-analytic review of mental health interventions targeting youth with internalizing disorders in juvenile justice facilities. Residential Treat Child Youth. 2019;36(3):235-256. doi: 10.1080/0886571X.2018.1560716 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Underwood LA, Washington A. Mental illness and juvenile offenders. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(2):228. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13020228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Skowyra KR, Cocozza JJ. Blueprint for Change: A Comprehensive Model for the Identification and Treatment of Youth With Mental Health Needs in Contact With the Juvenile Justice System. National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Erickson CD. Using systems of care to reduce incarceration of youth with serious mental illness. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;49(3-4):404-416. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9484-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Scott CK, Dennis ML, Grella CE, Funk RR, Lurigio AJ. Juvenile justice systems of care: results of a national survey of community supervision agencies and behavioral health providers on services provision and cross-system interactions. Health Justice. 2019;7(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s40352-019-0093-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Belenko S, Knight D, Wasserman GA, et al. The Juvenile Justice Behavioral Health Services Cascade: a new framework for measuring unmet substance use treatment services needs among adolescent offenders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;74:80-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Elkington KS, Lee J, Brooks C, Watkins J, Wasserman GA. Falling between two systems of care: engaging families, behavioral health and the justice systems to increase uptake of substance use treatment in youth on probation. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;112:49-59. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Robertson AA, Hiller M, Dembo R, et al. National survey of juvenile community supervision agency practices and caregiver involvement in behavioral health treatment. J Child Fam Stud. 2019;28(11):3110-3120. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01488-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) . Medicaid and the Criminal Justice System. MACPAC; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 101.State Plans for Medicaid Assistance, 42 USC §1393d(a)(29)(A) (2018).

- 102.US Department of Health and Human Services . Federal Fiscal Year (FFY) 2018 Statistical Enrollment Data System (SEDS) Reporting. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2019.

- 103.The Public Health and Welfare: State Children’s Health Insurance Program. Program, 42 USC §1397jj (2015).

- 104.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Serving special populations: incarcerated and recently released consumers facts for agents and brokers. Published 2019. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Health-Insurance-Marketplaces/Downloads/AB_Incarcerated-Consumers_Final.pdf

- 105.Anderson VR, Ouyang F, Tu W, Rosenman MB, Wiehe SE, Aalsma MC. Medicaid coverage and continuity for juvenile justice-involved youth. J Correct Health Care. 2019;25(1):45-54. doi: 10.1177/1078345818820043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Substance Use-Disorder Prevention That Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act or the Support for Patients and Communities Act . Public Law. 2018;115-271. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/115/plaws/publ271/PLAW-115publ271.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 107.American Medical Association . Health status of detained and incarcerated youth H-60.986. Published 2016.Accessed January 21, 2020. https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/Juvenile%20justice?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-5080.xml

- 108.Braverman PK, Murray PJ, Adelman WP, et al. ; Committee on Adolescence . Health care for youth in the juvenile justice system. Pediatrics. 2011;128(6):1219-1235. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.American Academy of Pediatrics . AAP publications reaffirmed or retired. Pediatrics. 2018;141(2):e20173629. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3629 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Abraham AJ, Andrews CM, Grogan CM, et al. The Affordable Care Act transformation of substance use disorder treatment. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(1):31-32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Thomas KC, Shartzer A, Kurth NK, Hall JP. Impact of ACA health reforms for people with mental health conditions. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(2):231-234. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Institute of Medicine . Health Insurance Is a Family Matter. National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Novotney A. A new emphasis on telehealth: how can psychologists stay ahead of the curve—and keep patients safe. Monit Psychol. 2011;42(6):40-44. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Glueckauf RL, Pickett TC, Ketterson TU, Loomis JS, Rozensky RH. Preparation for the delivery of telehealth services: a self-study framework for expansion of practice. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2003;34(2):159. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.34.2.159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. Expanded Notes on Study Methods

eMethods 2. Maximizing Comparability Among Measures: Changes to Scoring Algorithms for Testing Results

eTable 1. Demographic Characteristics and Retention of the Sample Recruited from the Cook County Juvenile Detention Center Between 1995 and 1998

eTable 2. Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders Over Time: Sex Differences

eTable 3. Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders Over Time: Racial/Ethnic Differences Among Males

eTable 4. Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders Over Time: Racial/Ethnic Differences Among Females

eTable 5. Odds Ratios Describing Demographic Differences in the Prevalence of Selected Psychiatric Disorders From Detention (Baseline) Through the 15-Year Time Point

eTable 6. Odds Ratios Describing Demographic Differences in the Prevalence of Selected Psychiatric Disorders from Detention (Baseline) Through the 15-Year Time Point

eTable 7. Odds Ratios Describing Demographic Differences in the Prevalence of Selected Psychiatric Disorders From Detention (Baseline) Through the 15-Year Time Point

eTable 8. Odds Ratios Describing Demographic Differences in the Prevalence of Selected Psychiatric Disorders From Detention (Baseline) Through the 15-Year Time Point

eTable 9. Odds Ratios Describing Demographic Differences in the Prevalence of Selected Psychiatric Disorders From Detention (Baseline) Through the 15-Year Time Point

eTable 10. 15-Year DSM-IV Diagnoses Predicted From Baseline Diagnoses Among Males

eTable 11. 15-Year DSM-IV Diagnoses Predicted From Baseline Diagnoses Among Females

eFigure 1. Prevalence of Comorbid Disorder in Delinquent Youth From Detention (Baseline) to 15 Years Postbaseline: Sex and Racial/Ethnic Differences

eFigure 2. Prevalence of Any Disorder (Excluding Behavioral Disorders) in Delinquent Youth From Detention (Baseline) to 15 Years Postbaseline: Sex and Racial/Ethnic Differences

eReferences