Abstract

Thirty-three U.S. states and the District of Columbia (DC) have legalized the use of marijuana for medicinal purposes and 10 states and DC have legalized marijuana for adult recreational use. This mirrors an international trend toward relaxing restrictions on marijuana. This paper analyzes patterns in marijuana laws across U.S. states to shed light on the social and political forces behind the liberalization of marijuana policy following a long era of conservatism. Data on U.S. state-level demographics, economic conditions, and cultural and political characteristics are analyzed, as well as establishment of and levels of support for other drug and social policies, to determine whether there are patterns between states that have liberalized marijuana policy versus those that have not. Laws decriminalizing marijuana possession, as well as those authorizing its sale for medical and recreational use, follow the same pattern of diffusion. The analysis points to underlying patterns of demographic, cultural, economic, and political variation linked to marijuana policy liberalization in the U.S. context, which deserve further examination internationally.

Keywords: medical marijuana, marijuana policy, substance control policy

In 2018, Michigan joined eight U.S. states and the District of Columbia (DC) that have legalized the use and possession of marijuana for recreational purposes and Vermont’s legislature passed a bill allowing recreational marijuana possession (Marijuana Policy Project [MPP], 2018a). In addition, 33 states and the DC have legalized its use for medicinal purposes (ProCon.org, 2018a) and 13 additional U.S. states have decriminalized the possession of marijuana in small amounts, with penalties typically limited to fines or community service (MPP, 2018a). Thirteen of the 17 states that do not permit medical or recreational use of marijuana permit high-cannabidiol-low-THC products (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2018). Lawmakers in 23 states considered legislation in 2018 to legalize recreational marijuana for adults (MPP, 2018b).

After nearly 100 years of highly restrictive marijuana policies (Siff, 2014), these changes in U.S. marijuana policy over the past two decades are striking. The trend toward state legalization for medical and recreational use has led policy analysts and public health officials to ask whether the U.S. is on a path toward the nationwide legalization of marijuana (Caulkins, Coulson, Farber, & Vesely, 2012; Caulkins, Kilmer, & Kleiman, 2016). Patterns in the U.S. reflect a larger international trend toward the legalization and decriminalization of marijuana. Canada, Colombia, the Netherlands, Spain, and Uruguay have legalized marijuana for personal use, although many European countries have resisted liberal marijuana policies (Berke & Gould, 2018; Bretteville-Jensen, 2016; Hughes, Quigley, Ballotta, & Griffiths, 2017). Many more countries have decriminalized marijuana possession in small amounts for personal use and legalized medical use (Kilmer & Pacula, 2017). The diversity of U.S. states mirrors international diversity: U.S. states each have their own social and political cultures and have substantial effective scope for local decisions within the context of federal law in many domains including alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana control policies. This variation makes the U.S. an instructive case for studying the underlying social and political forces that may be driving nations toward more liberal marijuana policies.

This paper analyzes social and political variation across the U.S. states to investigate factors that could be linked to the rising trend toward dismantling long-standing drug control regimes prohibiting marijuana sales and use. We analyzed data on demographics, economic conditions, and social and political characteristics to determine whether there are patterns between states that have liberalized marijuana policy versus those that have not. We also examined levels of public support for other drug and social policies to learn whether marijuana liberalization is linked to trends in regulatory choices in other policy realms.

Method

Data Collection

We collected data about the passage of state laws that permit retail marijuana sales, authorize marijuana use for medical purposes, and reduce penalties for marijuana possession to an infraction or civil offense from 1973 through 2016. Data were gathered from websites such as Procon.org (2018a), National Conference of State Legislatures (2018), and the MPP (2018a); public records of state laws; and published papers. When secondary sources provided conflicting information, we contacted state government officials directly to verify information.

Additional data were compiled regarding demographic, economic, and political characteristics of each state in 2014, which was the most recent year for which nearly all variables of interest were available at the time the analysis was conducted. While some variables such as unemployment rates fluctuate over time, the relative levels of these variables across states tend to remain stable. State-level demographic measures included age distribution, racial/ethnic mix (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2016), immigrant status (Flood, King, Ruggles, & Warren, 2015), education (Flood et al., 2015), religious affiliation (Pew Research Center, 2015), and frequency of attendance at religious services (Gallup Daily Tracking Survey, 2014). Economic characteristics included the unemployment rate (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016), share of employment in professional and business services and goods-producing occupations (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014), and average household income (Flood et al., 2015).

Political characteristics included whether the state legislature was controlled by the Democratic Party (Ballotpedia, 2014; National Conference of State Legislatures, 2014), percentages of the population self-identifying as conservative or liberal (Gallup Daily Tracking Survey, 2014), and whether states allow citizens to place initiatives and referendums on the ballot (Ballotpedia, 2018). Twenty-four states offer initiative or referendum rights to their citizens, and two additional states allow voters to veto legislation by referendum. Initiative and referendum rights exist in 18 of the 24 states west of the Mississippi river, but in only 8 of the 26 states east of the Mississippi river.

We also collected data on whether states have enacted other alcohol and other drug policies: marijuana decriminalization, legal syringe exchange programs (Law Atlas, 2016), a ban on Sunday off-premises sale of alcohol, and alcohol sales tax controls, in which the state sets the price of and gains revenue directly (rather than solely from taxation) from the wholesale or retail system of distribution for the index beverage (Alcohol Policy Information System, 2018). We also tracked other social policies: percentage of population approving of gay marriage (Flores & Barclay, 2015); whether states allow nurse practitioners to practice without physician oversight (American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 2016); abortion restrictiveness (NARAL, 2018); stand-your-ground gun laws (from 2012; FindLaw, n.d.; ProPublica, 2012), which allow individuals to defend themselves with deadly force when threatened; and concealed carry gun laws, which regulate whether permits are required and under what circumstances they can be issued for a citizen to carry a concealed gun (ProCon.org, 2018b).

Data Analysis

We examined geographic patterns and time trends of adoption of medical marijuana and recreational marijuana laws. We then compared social, economic, and political characteristics, and drug and social policies, of states that have not passed medical marijuana laws with those that passed medical marijuana laws prior to 2010; states that passed medical marijuana between 2010 and 2018; and states that have legalized recreational marijuana using Mann–Whitney U or Pearson’s χ2 tests to identify significant differences. Comparisons are also made across these states regarding other drug and social policies.

Results

Geographic and Time Trends in U.S. Marijuana Policy

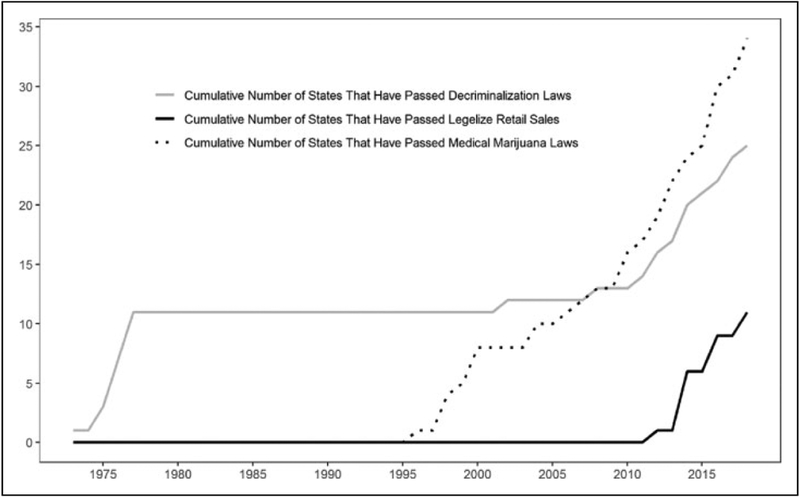

The advent of U.S. states legalizing marijuana for retail sale has roots in a longer wave of marijuana policy liberalization that began in 1973, when the first state law to decriminalize marijuana passed in Oregon (Figure 1). By 1977, 11 states had decriminalized marijuana possession in small amounts. Passage of California’s Proposition 215 in 1996, which legalized marijuana use for medical purposes, initiated a second wave of policy liberalization. By 2000, eight states had passed medical marijuana laws, all but one of which were located in the western U.S.

Figure 1.

Trends in U.S. state marijuana policy liberalization (1973–2018).

In 2004, the medical marijuana law trend “jumped coasts” when two states in the northeastern portion of the U.S. passed laws legalizing use for medicinal purposes. After 2004, the passage of new medical marijuana laws occurred in northern central, northeastern, and mid-Atlantic states. States in the south-eastern portions of the U.S., however, resisted medical marijuana laws until 2016, when Florida and Arkansas passed medical marijuana ballot propositions. In 2018, elected representatives in 14 of the remaining 17 states that do not permit medical marijuana considered legislation to establish medical marijuana programs. In only one of these states—Missouri—was there a floor vote on a medical marijuana bill (MPP, 2018b); Missouri passed a medical marijuana ballot initiative in November 2018.

In 1972, the first statewide ballot measure to legalize marijuana for adult recreational use was introduced and failed in California. Fourteen years later, Oregon tried with another ballot measure in 1986. Between 2000 and 2014, voters in primarily western states entertained 13 different legalization measures, with successes in Washington (2012), Colorado (2012), Oregon (2014), Alaska (2014), and Washington, DC (2014). In 2016, the legalization trend once again “jumped coasts” with two states in the northeastern U.S., in addition to the western states of California and Nevada. And, in 2018, a northern central state (Michigan) legalized recreational marijuana, along with another northeastern state (Vermont).

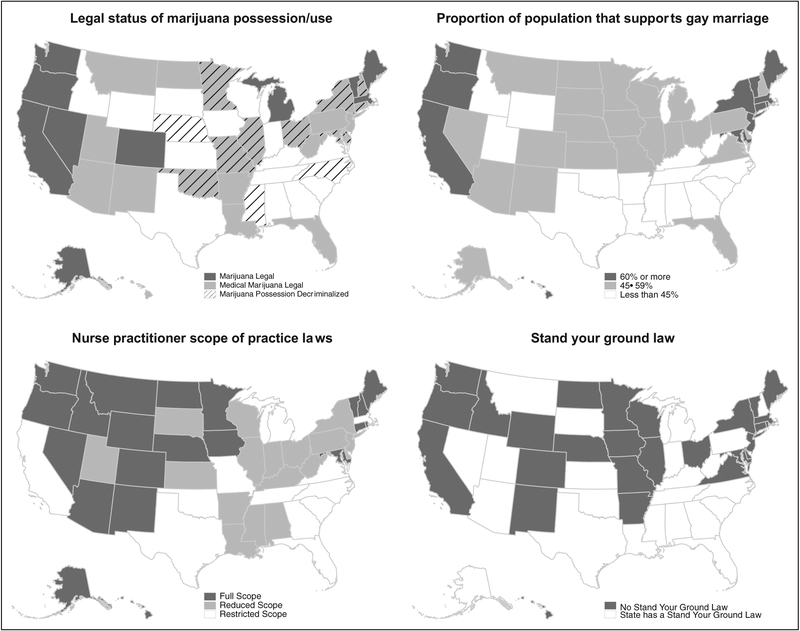

The first quadrant of Figure 2 shows the distinct geographic patterns among states that have liberalized marijuana policies. It shows states in which marijuana possession has been decriminalized (diagonal lines), medical marijuana is legal (gray), and where the sale of marijuana for recreational purposes is permitted (black). States in the northeastern U.S. and on the Pacific coast have more liberal marijuana policies than states in the central and southeastern parts of the country. This map also shows that states that have relaxed marijuana controls in one way tend to do so in others. Those that have legalized medical marijuana are more likely to have decriminalized possession (65% vs. 18%, p < .01) and to have established legal syringe exchange programs (47% vs. 0%, p < .001; Table 1). All states in the western and northeastern U.S. have legalized medical marijuana except for Idaho and Wyoming. The northern central states appear to be the next frontier for these laws, with four states having legalized medicinal use since 2008 and one legalizing recreational use in 2018. In contrast, no states in the southeast or southern central regions had adopted a medical marijuana law until 2016, when Arkansas and Florida passed propositions; three additional states in these regions have since passed medical marijuana laws, even though few states have decriminalized marijuana possession and none permit recreational marijuana use or sales.

Figure 2.

Maps of marijuana policies, gay marriage support, nurse practitioner independence, and “stand-your-ground” gun laws (2018).

Table 1.

Demographic, Economic, and Political Characteristics of U.S. States, and Other Social and Drug Policies by Marijuana Legalization Status (Percentages and Medians).

| State-level Characteristics | Medical Marijuana Not Legal (n = 17), % or Median | Medical Marijuana Legal Before 2010 (n = 13), % or Median | p Valuea | Medical Marijuana Legal 2010–2018 (n = 21), % or Median | p Valuea | Recreational Marijuana Legal (n = 11), % or Median | p Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||||||

| % Black/African American | 9.2 | 3.6 | .013 | 11.6 | .988 | 3.9 | .165 |

| % Asian | 2.0 | 3.4 | .057 | 3.0 | .036 | 4.1 | .008 |

| % Hispanic/Latino | 6.6 | 12.2 | .187 | 9.3 | .371 | 10.8 | .180 |

| % Adult population foreign-born | 6.8 | 12.3 | .038 | 12.1 | .036 | 12.3 | .015 |

| % Population 18–24 years | 9.7 | 9.5 | .325 | 9.5 | .146 | 9.8 | .832 |

| % Population 25–44 years | 25.4 | 27.0 | .630 | 25.8 | .692 | 27.9 | .086 |

| % Population 45–64 years | 25.7 | 26.0 | .346 | 26.6 | .146 | 26.0 | .495 |

| % Population 65+ years | 15.1 | 16.3 | .217 | 15.8 | .325 | 15.0 | .796 |

| % Population less than 12 years education | 11.4 | 9.0 | .098 | 10.6 | .234 | 9.0 | .078 |

| % Catholic | 12.0 | 20.0 | .018 | 22.0 | .019 | 20.0 | .028 |

| % Evangelical Protestant | 31.0 | 23.0 | .001 | 19.0 | .001 | 21.0 | <.001 |

| % Mainline Protestant | 16.0 | 14.0 | .058 | 16.0 | .882 | 13.0 | .027 |

| % No religious affiliation | 20.0 | 29.0 | <.001 | 22.0 | .147 | 31.0 | <.001 |

| % Attends religious services at least 1 ×/week | 35.0 | 26.0 | <.001 | 32.0 | .035 | 24.0 | <.001 |

| % Attends religious services seldom or never | 40.0 | 55.0 | <.001 | 46.0 | .013 | 57.0 | <.001 |

| % Marijuana use last monthb | 6.5 | 11.5 | <.001 | 7.8 | .009 | 11.8 | <.001 |

| Economic characteristics | |||||||

| Unemployment rate | 5.4 | 6.7 | .143 | 6.1 | .518 | 6.8 | .074 |

| % Employed in professional occupations | 11.6 | 12.7 | .691 | 13.3 | .081 | 12.9 | .213 |

| % Employed in goods-producing occupations | 16.2 | 12.7 | .001 | 13.5 | .003 | 13.0 | .003 |

| % Households with income ≥$75K | 17.2 | 21.7 | .016 | 21.6 | .025 | 24.8 | .003 |

| Political characteristics | |||||||

| % Democrats control state legislature | 0 | 77 | <.001 | 43 | .002 | 82 | <.001 |

| % Population identifies as conservative | 39.9 | 33.8 | <.001 | 36.1 | .009 | 33.7 | <.001 |

| % States that allow initiatives/referenda | 18 | 69 | .008 | 33 | .460 | 82 | .001 |

Mann–Whitney U test (continuous variables), Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher exact test (counts).

National Survey on Drug Use and Health (2014–2015) Restricted-use Data Analysis System; respondents 12+.

Demographic and Social Characteristics

States participating in the trend toward liberalizing marijuana policy are demographically, economically, and politically distinct. The first five columns of Table 1 describe states that legalized medical marijuana prior to 2010 (early adopters) and between 2010 and 2018 (late adopters) compared to those that have not. The last two columns describe states that have legalized recreational marijuana and compare them to states that have not legalized medical marijuana.

Early adopters of medical marijuana had, on average, smaller proportions of Black/African American residents (3.6% vs. 9.2%, p = .013) and larger immigrant populations (12.3% vs. 6.8%, p = .038). Late adopters of medical marijuana also had a larger immigrant population (12.1% vs. 6.8%, p = .036) and a larger Asian population (3% vs. 2%, p = .036). States that have legalized recreational marijuana also had a larger Asian (4.1% vs. 2%, p = .008) and immigrant population (12.3% vs. 6.8%, p = .015). There were no statistically significant differences in the age distribution of the population across states in different marijuana legalization categories. There were also no significant differences in the share of the population with less than 12 years of education.

Residents of early-adopter medical marijuana states were more likely to report that they are Catholic than residents of nonlegal states (20% vs. 12%, p = .018), as were residents of late-adopter (22% vs. 12%, p = .019) and recreational marijuana states (20% vs. 12%, p < .028). Evangelical Protestantism was much less often reported by residents of all categories of legal marijuana states than in nonlegal states (19–23% vs. 31%, p ≤ .001). Residents in states with recreational marijuana were less likely to report they are Mainline Protestant than residents of nonlegal states (13% vs. 16%, p = .027). Early-adopter medical and recreational marijuana states had a larger share of residents who reported no religious affiliation (29–31% vs. 20%, p < .001), but late-adopter medical marijuana states were not significantly different from nonlegal states (22% vs. 20%, p = .147). Residents in all categories of legal marijuana states were less likely to report weekly religious service attendance; the difference was notably larger among early-adopter and recreational states versus nonlegal states (24–26% vs. 35%, p < .001) than for late-adopter states (32% vs. 35%, p = .013). Conversely, residents of all categories of legal marijuana states were more likely to report they seldom or never attended religious services (46–57% vs. 40%, p < .01).

Residents of all categories of legal marijuana states were more likely to have used marijuana in the past month than those in nonlegal states, with the highest rates among early-adopter medical and recreational states (11.5–11.8% vs. 6.5%, p < .001). Late-adopter medical marijuana states also had a higher share of residents who used marijuana in the past month than nonlegal states, but the difference was not as large (7.8% vs. 6.5%, p = .009). These differences could reflect increased marijuana use that resulted from liberal marijuana policies as well as increased likelihood of liberalizing marijuana laws if a larger share of residents already use marijuana; it is not possible to determine a causal relationship.

Economic Characteristics

States with medical and recreational marijuana laws had a smaller share of the workforce employed in goods-producing occupations than nonlegal states (12.7–13.5% vs. 16.2%, p ≤ .003). These states also had a greater share of households with incomes over US$75,000 (21.6%–24.8 % vs. 17.2%, p ≤ .025). There were no significant differences across states in unemployment rates or the share of workers in professional occupations.

Political Characteristics

Among early-adopter medical marijuana states, 77% had legislatures controlled by Democrats in 2014 compared with none among nonlegal states (p < .001). The difference was even larger among recreational marijuana states (82%, p < .001). Among late-adopter medical marijuana states, less than half had Democrat-controlled legislatures in 2014 (43%, p = .002). A smaller share of the population identified as ideologically “conservative” in all categories of legal marijuana states versus nonlegal states (34–36% vs. 40%, p ≤ .009). A closer look at the time trend reveals that 9 of the 10 states that passed medical marijuana laws between 2010 and 2014 had Democrat-controlled legislatures in 2014; the one Republican-controlled state passed medical marijuana by ballot initiative. Conversely, 9 of the 10 states that passed medical marijuana laws after 2014 had Republican-controlled legislatures in 2014 and three of these had legislatively passed laws.

States that were early adopters of medical marijuana are more likely to allow ballot initiatives and referenda than are nonlegal states (69% vs. 18%, p = .008), as are states with recreational marijuana (82% vs. 18%, p = .001). There was no statistically significant difference in the share of late-adopter medical marijuana states that allow ballot initiatives versus nonlegal states (33% vs. 18%, p = .46). Seven of the first 10 states to establish medical marijuana provisions did so by initiative or referenda. However, the trend has shifted toward legislative approval of medical marijuana, with only 9 of the 21 states passing medical marijuana laws since 2010 doing so by ballot initiative. Recreational marijuana laws have passed by ballot initiative in all but one state (Vermont), which permits possession/use only, while the other states permit both sales and use.

Drug and Social Policies

Table 2 compares drug and social policies among nonlegal, early-adopter medical, late-adopter medical, and recreational marijuana states. States with legal medical and recreational marijuana are also more likely to have decriminalized marijuana compared with nonlegal states (57–100% vs. 18%, p ≤ .02). States in all categories of marijuana legalization also are less likely to have a ban on off-premises sales of alcohol on Sundays compared with nonlegal states (0–10% vs. 41%, p ≤ .051). However, there was no significant difference in the shares of states with alcohol sales tax controls.

Table 2.

State Social and Drug Policies by Marijuana Legalization Status (Percentages and Medians).

| State-level Characteristics | Medical Marijuana Not Legal (n = 17), % or Median | Medical Marijuana Legal Before 2010 (n = 13), % or Median | p Valuea | Medical Marijuana Legal 2010–2018 (n = 21), % or Median | p Valuea | Recreational Marijuana Legal (n = 11), % or Median | p Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other drug-related policies | |||||||

| % Marijuana possession decriminalized | 18 | 77 | 0.002 | 57 | .020 | 100 | <0.001 |

| Legal syringe exchange program | 0 | 69 | <0.001 | 33 | .011 | 73 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol sales tax control (%)b | 41 | 38 | 1.000 | 25 | .482 | 40 | 1.000 |

| Alcohol Sunday ban (%)c | 41 | 0 | 0.010 | 10 | .051 | 0 | 0.023 |

| Other state-level policies | |||||||

| % Approves of gay marriage | 43.8 | 60.2 | <0.001 | 54.6 | .015 | 61.3 | <0.001 |

| % Law allowing nurse practitioners to practice independently | 24 | 85 | 0.003 | 33 | .721 | 73 | 0.019 |

| Abortion restrictiveness (%) | <0.001 | .005 | <0.001 | ||||

| Strongly protected access | 0 | 38 | 5 | 27 | |||

| Protected access | 0 | 38 | 24 | 45 | |||

| Some access | 0 | 8 | 19 | 18 | |||

| Restricted access | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Severely restricted | 94 | 15 | 52 | 9 | |||

| Stand your ground gun law | 65 | 31 | 0.139 | 38 | .191 | 27 | 0.120 |

| Concealed carry gun law (%) | 0.143 | .076 | 0.194 | ||||

| No permit required | 24 | 23 | 24 | 27 | |||

| Discretionary/reasonable issue | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | |||

| Rights restricted-very limited issue | 0 | 23 | 24 | 18 | |||

| Shall issue | 76 | 54 | 48 | 55 |

Mann–Whitney U test (continuous variables), Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher exact test (counts).

State sets the price of and gains profit/revenue directly (rather than solely from taxation) from the wholesale or retail system of distribution for the index beverage.

Bans on Off-Premises Sunday Sales—States are classified as having local option if at least some local governments have the authority to permit Sunday sales as an exception to a State ban.

Residents of states in which medical or recreational marijuana is legal were more likely to approve of gay marriage than residents in nonlegal states (55–61% vs. 44%, p ≤ .015). Early-adopter medical and legal marijuana states are more likely than nonlegal states to allow nurse practitioners to practice without physician oversight (73–85% vs. 24%, p ≤ .019), but this difference is not apparent for late-adopter medical states (33%, p = .721).

There are notable differences in abortion policy between early-adopter medical and recreational marijuana states as compared with late-adopter medical and nonlegal states. Approximately three quarters of early adopter medical and recreational states protect or strongly protect abortion access, while less than one third of late-adopter medical states and no nonlegal states protect abortion access (p ≤ .005). Abortion access is severely restricted in 94% of nonlegal marijuana states and 52% of late-adopter medical marijuana states. In contrast, there are no significant differences across state categories regarding stand-your-ground or concealed-carry gun laws, although a lower share of all categories of legal marijuana states have stand-your-ground gun laws (27–38%) as compared with nonlegal marijuana states (65%, p ≥ .12). Legal marijuana states also have a higher share of states with limited issue of concealed-carry permits (18–24% vs. 0%), but the overall differences are not statistically significant (p ≥ .076).

Figure 2 shows geographic patterns regarding marijuana legalization, support for gay marriage, laws allowing nurse practitioners to practice without physician oversight, and “stand-your-ground” gun laws. The associations described in Table 2 are apparent in these maps. The same geographic regions that have been resistant to liberalized marijuana policies—southeastern and south central states—also are less likely to support gay marriage or allow nurse practitioners to practice without physician oversight. More complex relationships are apparent between states with stand-your-ground gun laws and those that have liberalized marijuana policy. All western states with stand-your-ground laws permit medical marijuana (Arizona, Montana, Utah) or recreational marijuana (Nevada). Among the five south central and southeastern states with medical marijuana laws (Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Oklahoma, West Virginia), all but one (Arkansas) have stand-your-ground gun laws; most other states in these regions have stand-your-ground gun laws but have resisted medical marijuana and none have legalized recreational marijuana. Michigan and New Hampshire are the only two other states with both stand-your-ground and medical marijuana laws.

Discussion

In the U.S., passage of restrictive marijuana control policies commenced in the early 20th century with a movement across states that culminated in a federal policy prohibiting all cultivation, sales, and use (Siff, 2014). Over the past 20 years, we have witnessed a dismantling of marijuana control policies in a similar movement across states. This study investigated the underlying social and political factors that may influence marijuana policy liberalization.

We observed that the passage of more permissive marijuana policies follows a clear geographic pattern. In all cases—decriminalization, medical marijuana, and recreational use laws—the pattern began in western states. Once western states initiated adoption of a less restrictive marijuana policy, the pattern of diffusion “jumped coasts” to the northeast, reaching states that share similar (but less pronounced) social and political characteristics. After a critical mass of these states passed the given marijuana policy, the trend moved toward states in the northern central and mid-Atlantic regions. There has been little movement toward liberal marijuana policy in the Southeastern and Central regions. This geo-temporal pattern has been observed in the diffusion of decriminalization and medical marijuana laws and appears to be in its early stages for laws permitting adult recreational use.

We found clear patterns in the social and political characteristics of states participating in the recent wave of marijuana policy liberalization, characterized by large immigrant populations and low rates of goods production, Evangelical Protestantism, religious observance, and political conservatism. States that have resisted liberalization, which are generally located in the Southeastern and Central regions, tend toward Evangelical Protestantism and strong religious observance, disproportionately low representations of Asians and immigrants, and high shares of workers in goods-producing occupations. The associations measured in our analysis do not demonstrate causal relationships and, for some variables such as goods production, may reflect other geographically correlated social patterns. Other associations, such as religiosity, are more likely to directly explain marijuana policy trends. Religion has had an important influence in American alcohol and other drug policy, with Evangelicalism playing a large role in the U.S. temperance and prohibition movements (Schmidt, 1995).

The political environment, including whether citizens can place initiatives and referenda on the ballot, is also associated with the establishment of liberal marijuana policies. The states that first allowed medical marijuana often did so by initiative or referendum, which likely reflected the difference between established policy and public perceptions of marijuana. The option for citizens to propose initiatives and referenda also aligns with libertarian views of government regulation and policy change, which may extend to drug policy.

In recent years, legislative passage of medical marijuana has become more common than ballot initiatives. There also has been a notable shift in toward medical marijuana passage in states in which Republicans controlled the state legislature in 2014. National advocacy organizations, including the Marijuana Policy Project (MPP), National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), and Drug Policy Alliance, have provided financial and logistical support to campaigns for liberal marijuana policies through both legislation and initiatives/referenda. Through 2014, political donations by MPP were directed primarily at Democrats. However, since 2016, a greater share of their donations has gone to Republican candidates (OpenSecrets.org, 2018). These organizations and new advocacy groups, such as the New Federalism Fund and the National Cannabis Industry Association, are increasingly funded by the marijuana industry (Hughes, 2018; Wallace, 2017). In early 2018, the value of the marijuana industry was estimated at $8 billion, generating at least $2 billion in taxes (Hughes, 2018), increasing the financial incentive to lawmakers to adopt permissive policies.

Comparisons of marijuana laws and other drug and social policies found positive correlations: The divide between states on marijuana policy is mirrored in political divisions over widening the scope of nurse practitioner practice, gun control, and gay marriage. However, we observed some notable exceptions. Some western states that have legalized recreational use depart from the pattern by opposing gun control. This could be accounted for by the different political configurations in more libertarian western states, where personal freedoms are highly valued, including both freedoms to own guns and use marijuana. At the same time, traditionally conservative southeastern states have higher shares of Evangelical Protestants who attend religious services regularly, and these states are also prone to restrict nurse practitioner practice and disapprove of gay marriage.

Galston and Dionne (2013) examined a number of social policies in relation to support for marijuana legalization and highlighted key factors that are apparent in our analysis. First, although Democrats are more likely to support legalization of marijuana than Republicans, a growing share of Republicans also support legalization or at least do not actively support criminalization. This appears to be associated with skepticism about whether enforcing marijuana laws produces a net social benefit, as well as libertarian leanings among some Republicans. Galston and Dionne also note that divisions in views of social policies across age groups may be predictive of long-term changes. For example, views of gay marriage are correlated with age, with younger people strongly in support, portending a trend toward widespread support of gay marriage. In contrast, views of abortion are not associated with age, suggesting ongoing conflict, and states with restrictive abortion policies also strongly lean toward restrictive marijuana policies. However, public option of marijuana legalization is more positive among younger people than older people, which increases the potential for national liberalization of marijuana policy over time.

Each state’s medical marijuana law is different, with variation in provisions such as whether patients must register with the state, whether caregivers can purchase marijuana for patients, how much marijuana a patient can possess, and whether patients can grow their own plants. Previous research has categorized state laws through 2014 according to how easy it is to become an approved medical marijuana user, the quantity of marijuana that can be possessed, and the degree of state control over marijuana distribution (Chapman, Spetz, Lin, Chan, & Schmidt, 2016). States that passed medical marijuana laws prior to 2010 permit possession of larger quantities, make it easier to be approved as a medical marijuana user, and have less-controlled distribution systems than states that passed laws from 2010 through 2014. In other words, late adopters of medical marijuana have established more conservative and controlled programs than early adopters.

In the past three years, five southeastern states passed medical marijuana laws, suggesting a shift toward approval of medical marijuana even in states that have historically resisted it. President Trump won the vote by wide margins in these states and his administration has indicated support for medical marijuana (Halper, 2018). National polls show increasingly widespread support for the use of marijuana if prescribed by a physician (Bogdanoski, 2010) and, in 2016, 57% of adults favored recreational legalization (Anderson & Olmstead, 2016). National policy also is shifting; the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a marijuana-derived pharmaceutical for the treatment of epilepsy in 2018 (Joseph, 2018) and bipartisan federal legislation would remove marijuana from the Drug Enforcement Agency Schedule 1 category, which is for drugs that have no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse (Halper, 2018). MPP has spent more than $1 million in federal lobbying since 2002, and the Drug Policy Alliance, which seeks reform of all drug laws, has spent almost $4.2 million in federal lobbying since 2001. Nonetheless, medical marijuana legislation proposed in most states that do not yet permit it did not fare well in 2018, demonstrating ongoing resistance to marijuana legalization.

Limitations

This study has two important limitations. First, the analysis is correlational and is not designed to precisely define the complex processes that underlie marijuana policy change. The demographic, economic, political, and social characteristics and policies examined were measured at only one point in time, even though many of the characteristics are time-varying. Thus, the variables were not measured for the years when most states passed their medical or recreational marijuana laws. We examined whether the patterns described in this paper changed if different years of data were used for a few variables, such as unemployment rates in 2004 and 2016, and obtained similar results. However, because the relationships described are asynchronous, the analysis cannot be viewed as predictive or causal with respect to marijuana policies.

Second, patterns in marijuana policy adoption are almost certainly driven by more complex factors than those discussed here. The interplay of social norms, political structure, legislative and ballot initiative strategy, and advocacy cannot be readily disentangled. Nonetheless, we found some patterns both across states and over time that suggest that some demographic, economic, and political characteristics may be more important than others.

Conclusion

This study was an initial effort to understand patterns of marijuana liberalization across diverse U.S. states. Future research should examine international variation in geo-temporal patterns, as well as in the underlying social and political configurations observed here, which may be applicable to other societies. There is a further need for systematic studies on the characteristics of new marijuana policies (Chapman et al., 2016), which may reflect subtle differences in social, demographic, and economic characteristics (Gass, 2016; Kilmer & Pacula, 2017). Differences in the ways liberalization policies regulate marijuana may be critical for mitigating public health harms, such as youth marijuana use and secondhand smoke exposure.

The trend toward marijuana policy liberalization, in the U.S. and worldwide, raises concerns about the current scarcity of research on the medical value of marijuana and its public health impacts (Hajizadeh, 2016; Lake & Kerr, 2017). Research to date suggests that marijuana use is accompanied by a range of harms (Feeney & Kampman, 2016; Volkow et al., 2014), although advocates for legalization argue that marijuana is already widely available through illicit markets, leaving governments unable to regulate its potency and distribution (Nathan, Clark, & Elders, 2017; Williams, 2016), prevent youth exposure (Spithoff & Kahan, 2014; Ubelacker, 2014), and consider the benefits of making marijuana available as an alternative to riskier substances (Lau et al., 2015; Lucas et al., 2013, 2015; Vyas, LeBaron, & Gilson, 2017). Evidence presented here suggests that, because the liberalization of marijuana policy is likely to continue, there is a global need to build up the evidence base on marijuana and health, the public health consequences of rolling back marijuana controls, and strategies for regulating access in a legalization context.

Acknowledgments

The assistance of Jessica Lin and Krista Chan in collecting state-level data is appreciated. Juliana Fung helped to develop graphics for the figures.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA034091–01).

Author Biographies

Joanne Spetz, PhD, is a professor at the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies and the Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California, San Francisco. She also is Associate Director for Research at Healthforce Center at University of California, San Francisco.

Susan A. Chapman, PhD, RN, is a professor in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, UCSF School of Nursing, Healthforce Center and the Institute for Health Policy Studies. She is Co-Director of the Masters and Doctoral programs in Health Policy at the School of Nursing.

Timothy Bates, MPP, is a senior research analyst at the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies and Healthforce Center at UCSF.

Matthew Jura is a doctoral candidate at the Institute of Biomedical Informatics, National Yang-Ming University. He also is a Research Data Analyst at the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies and Healthforce Center at UCSF.

Laura A. Schmidt, PhD, is a professor of Health Policy in the School of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco. She holds a joint appointment in the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies and the Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine. Dr. Schmidt is also Co-Director of the Community Engagement and Health Policy Program for UCSF’s Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Alcohol Policy Information System. (2018). Retail distribution systems for beer. Retrieved October 28, 2018, from https://alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/apis-policy-topics/retail-distribution-systems-for-beer/5

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners. (2016). State practice environment. Washington, DC: American Association of Nurse Practitioners. Retrieved December 3, 2017, from https://www.aanp.org/legislation-regulation/state-legislation/state-practice-environment [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M, & Olmstead K (2016, October 12). Support for marijuana legalization continues to rise. Pew Research Center. Retrieved December 3, 2017, from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/10/12/support-for-marijuana-legalization-continues-to-rise/

- Ballotpedia. (2014). United States Congressional delegations by state. Washington, DC: District of Columbia Board of Ethics & Elections, Historical Elected Officials. [Google Scholar]

- Ballotpedia. (2018). States with initiative or referendum. Retrieved November 4, 2018, from https://ballotpedia.org/States_with_initiative_or_referendum

- Berke J, & Gould S (2018). Michigan is the 10th state to legalize recreational marijuana. This map shows every US state where pot is legal. Business Insider, November 7. Retrieved November 15, 2018, from https://www.businessinsider.com/legal-marijuana-states-2018-1

- Bogdanoski T (2010). Accommodating the medical use of marijuana: Surveying the differing legal approaches in Australia, the United States and Canada. Sydney Law School Legal Studies Research Paper No. 10/63, Sydney, Australia. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretteville-Jensen A (2016). Expected lessons from the US experience with alternative cannabis policy regimes. Addiction, 111, 2090–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulkins JP, Coulson CC, Farber C, & Vesely JV (2012). Marijuana legalization: Certainty, impossibility, both, or neither? Journal of Drug Policy Analysis, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Caulkins JP, Kilmer B, & Kleiman MAR (2016). Marijuana legalization: What everyone needs to know? Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman S, Spetz J, Lin J, Chan K, & Schmidt L (2016). Capturing heterogeneity in medical marijuana policies: A taxonomy of regulatory regimes across the United States. Substance Use and Misuse, 51, 1174–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney KE, & Kampman KM (2016). Adverse effects of marijuana use. The Linacre Quarterly, 83, 174–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FindLaw. (n.d.). States that have stand your ground laws. Retrieved September 15, 2017, from http://criminal.findlaw.com/criminal-law-basics/states-that-have-stand-your-ground-laws.html

- Flood S, King M, Ruggles S, & Warren JR (2015). Integrated public use microdata series, current population survey: Version 4.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Flores AR, & Barclay S (2015). Trends in public support for marriage for same-sex couples by state, 2004–2014. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup Daily Tracking Survey. (2014). Religious service attendance by state. Annual State of the States series, Gallup Daily Tracking Survey. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/181601/frequent-church-attendance-highest-utah-lowest-vermont.aspx

- Galston WA, & Dionne EJ Jr. (2013). The new politics of marijuana legalization: Why opinion is changing. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Gass N (2016). National poll: Majority supports legalizing marijuana. Politico, June 6. Retrieved December 3, 2017, from http://www.politico.com/story/2016/06/do-people-support-legalizing-marijuana-223928

- Hajizadeh M (2016). Legalizing and regulating marijuana in Canada: Review of potential economic, social, and health impacts. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 5, 453–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halper E (2018). Trump says he is likely to support ending blanket federal ban on marijuana. Los Angeles Times, June 8. Retrieved July 8, 2018, from http://www.latimes.com/politics/la-na-pol-trump-marijuana-20180608-story.html

- Hughes B, Quigley E, Ballotta D, & Griffiths P (2017). European observations on cannabis legalization. Addiction, 112, 1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T (2018). Marijuana money increasingly flowing to Republican lawmakers. USA Today, January 21. Retrieved January 3, 2019, from https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2018/01/21/marijuana-money-increasingly-flowing-republican-lawmakers/1042239001/

- Joseph A (2018). FDA approves country’s first medicine made from marijuana. STAT News, June 25. Retrieved July 8, 2018, from https://www.statnews.com/2018/06/25/fda-approves-countrys-first-medicine-made-from-marijuana/

- Kilmer B, & Pacula RL (2017). Understanding and learning from the diversification of cannabis supply laws. Addiction, 112, 1128–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake S, & Kerr T (2017). The challenges of projecting the public health impacts of marijuana legalization in Canada: Comment on “Legalizing and regulating marijuana in Canada: Review of potential economic, social, and health impacts.” International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 6, 285–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau N, Sales P, Averill S, Murphy F, Sato SO, & Murphy S (2015). A safer alternative: Cannabis substitution as harm reduction. Drug and Alcohol Review, 34, 654–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law Atlas. (2016). Policy surveillance portal: Syringe distribution laws map, 2012–2015. Retrieved March 15, 2017, from http://lawatlas.org/data

- Lucas P, Reiman A, Earleywine M, McGowan SK, Oleson M, Coward MP, & Thomas B (2013). Cannabis as a substitute for alcohol and other drugs: A dispensary-based survey of substitution effect in Canadian medical cannabis patients. Addiction Research and Theory, 21, 435–442. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas P, Walsh Z, Crosby K, Callaway R, Belle-Isle L, Kay R,… Holtzman S (2015). Substituting cannabis for prescription drugs, alcohol and other substances among medical cannabis patients: The impact of contextual factors. Drug and Alcohol Review, 35, 326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marijuana Policy Project. (2018a). State policy map detailing current status of marijuana-related laws. Retrieved November 15, 2018, from https://www.mpp.org/states/

- Marijuana Policy Project. (2018b). 2018 Marijuana policy reform legislation. Retrieved November 15, 2018, from https://www.mpp.org/states/key-marijuana-policy-reform/

- NARAL. (2018). What anti-choice measures are in place in your state? Retrieved October 28, 2018, from https://www.prochoiceamerica.org/laws-policy/state-government/

- Nathan DL, Clark HW, & Elders J (2017). The physicians’ case for marijuana legalization. American Journal of Public Health, 107, 1746–1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Conference of State Legislatures. (2014). 2014 State and legislative partisan composition. Retrieved November 15, 2018, from http://www.ncsl.org/documents/statevote/legiscontrol_2014.pdf

- National Conference of State Legislatures. (2018). State medical marijuana laws. Retrieved November 15, 2018, from http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx

- OpenSecrets.org. (2018). Marijuana. Retrieved November 4, 2018, from https://www.opensecrets.org/news/issues/marijuana/

- Pew Research Center. (2015). America’s changing religious landscape. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- ProCon.org. (2018a). 33 Legal medical marijuana states and DC: Laws, fees, and possession limits. Retrieved November 15, 2018, from http://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/view.resource.php?resourceID=000881

- ProCon.org. (2018b). Concealed carry permit laws by state. Retrieved October 28, 2018, from https://concealedguns.procon.org/view.resource.php?resourceID=005541

- ProPublica. (2012). The 24 states that have sweeping self-defense laws just like Florida’s. Retrieved December 15, 2017, from http://www.propublica.org/article/the-23-states-that-have-sweeping-self-defense-laws-just-like-floridas

- Schmidt LA (1995). “A battle not man’s but God’s”: Origins of the American temperance crusade in the struggle for religious authority. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 56, 110–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siff S (2014). The illegalization of marijuana: A brief history. Origins, 7. Retrieved June 17, 2017, from http://origins.osu.edu/article/illegalization-marijuana-brief-history

- Spithoff S, & Kahan M (2014). Cannabis and Canadian youth: Evidence, not ideology. Canadian Family Physician, 60, 785–787. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubelacker S (2014). Pot should be legalized, regulated and sold like alcohol: Addiction centre. The Globe and Mail, October 9. Retrieved December 3, 2017, from http://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/health-and-fitness/health/pot-should-be-legalized-regulated-and-sold-like-alcohol-addiction-centre/article20995728/

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2014). State and area employment, hours, and earnings by industry (not seasonally adjusted). Current Employment Statistics, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved March 3, 2017, from https://www.bls.gov/sae/home.htm

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2016). Employment status of the civilian noninstitutional population (annual averages). Local Area Unemployment Statistics, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved March 3, 2017, from http://www.bls.gov/lau/rdscnp16.htm

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. (2016). Annual state resident population estimates for 6 race groups (5 race alone groups and two or more races) by age, sex, and Hispanic origin: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, & Weiss SRB (2014). Adverse health effects of marijuana use. New England Journal of Medicine, 370, 2219–2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas MB, LeBaron VT, & Gilson AM (2017, September 1). The use of cannabis in response to the opioid crisis: A review of the literature. Nursing Outlook, 66, 56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace A (2017). Powerhouse cannabis firms form lobby group to protect state-based weed laws. The Cannabist, March 23. Retrieved January 3, 2019, from https://www.thecannabist.co/2017/03/23/new-federalism-fund-marijuana-lobbying-congress/75988/

- Williams J (2016). Economic insights on market structure and competition. Addiction, 111, 2094–2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]