ABSTRACT

Introduction

The COVID-19 global pandemic is a public health emergency due to its high virulence and mortality. Many vaccine development studies at clinical trials are currently conducted to combat SARS-CoV-2. Plants are a rich source of phytochemicals with different biological activities, including antiviral activities, which are the focus of many studies.

Areas covered

This review shows compounds of traditional plants listed on RENISUS list have therapeutic properties against SARS-CoV-2 targets.

Expert Opinion

The rise of new variants, more pathogenic and virulent, impacts in the increase of mortality from SARS-CoV-2 infection, and thus, the control of the outbreaks of disease remains a global challenge. Other’s drug and vaccines development is an essential element in controlling SARS-COV-2. Therefore, it is imperative that approach to tackle this pandemic has to be solidly evidence-informed. It should be noticed that the immune system does play critical roles in fighting viruses. Studies show that T cells levels decreased continuously as the disease progressed. T cell-mediated cellular immune response, probably by immunological memory, is essential for direct virus eradication after infection whilst B cells functions in producing antibodies that neutralize virus.But, have distinct patterns of T cell response exist in different patients, suggesting the possibility of distinct clinical approaches. Efforts are concentrated to elucidate the underlying immunological mechanisms in SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis and progression for better design of diagnostic, therapeutic and preventive strategies. We seek to identify biomolecules with the potential to act in biomarkers that predict how severe the disease can get. But it is important to warn that the plants that produce the compounds mentioned here should not be used without a physician prescription. Finally, we speculate that these compounds may eventually attract the attention of physicians and researchers to perform tests in specific contexts of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and if they show positive results, be tested in Clinical trials.

KEYWORDS: SARS-CoV-2, targets, medicinal plants, compounds, therapeutic effects

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is a delicate global challenge that is demanding a paradigm shift [1]. The outbreak of the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is extended to every continent, forcing us to adapt and live with this virus for perhaps a long time. Scientists quickly learned much about coronavirus disease and its pathogenesis [2]. SARS-CoV-2 has four main structural proteins: small envelope (E) glycoprotein, membrane (M) glycoprotein, nucleocapsid (N) protein, and spike (S) glycoprotein. S glycoprotein facilitates binding to host cells with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expressed in lower respiratory tract cells [3]. After the virus enters the host cell, SARS-CoV-2 binds to the ACE2 receiver, highly expressed in the lower respiratory tract. These include type II alveolar cells (AT2) of the lungs, esophagus, stratified epithelial cells, myocardial cells, and kidney proximal tubule cells. Therefore, patients who are infected with this virus experience not only respiratory problems such as pneumonia leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) but also heart, kidneys, and digestive tract disorders [4].

Much of the discussion about SARS-CoV-2 immunity has focused on antibodies. However, T cells target already infected cells and eradicate them, preventing viruses from spreading to other healthy cells. That is, while antibodies destroy viruses, T cells destroy cells in the body that have become ‘virus factories’ [5]. In this sense, researchers are testing interleukin 7, a cytokine known to increase T cells’ production. This will serve to detect if the cells can really help in the recovery of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 [6].

Even though vaccines have recently been approved, scientists keeping working to develop a treatment’s [7]. Researchers have found 27 essential proteins in the blood of people infected with SARS-CoV-2 that can act as biomarkers that predict how severe the disease can get. They include complement factors, the coagulation system, inflammation modulators, and pro-inflammatory factors upstream and downstream as interleukin 6 (IL-6). The study reveals that these proteins are present at different levels in SARS-CoV-2 patients, depending on severity of their symptoms [1], which may provide new goals for developing possible treatments for the disease.

In this sense, considering the huge metabolic potential, plants appear as an important alternative in the search for potential compounds to fight this disease [8]. Based on their antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects, some phytochemicals such isoflavones, curcumin and diallyl disulfide, have attracted particular attention to providing novel agents in combating coronaviruses and related complications [9]. These compounds exert antiviral activities against broad spectrum of viruses including adenovirus, Zika virus, herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), human papiloma virus (HPV), influenza virus, hepatitis virus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), besides MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV [10–12]. The Brazilian Ministry of Health, 12 herbal medicines derived from plants that are part of the National List of Medicinal Plants of Interest to the Unified Health System (RENISUS), are available for free in the public health network [13]. The list includes 71 species of plants, some native to Brazil, however, most are exotic species, that are easily grown and used in other countries, often in the form of food or spices, such as garlic, saffron, soybeans, and ginger, for example [14]. It is noteworthy that many plants of the RENISUS list have already been researched concerning therapeutic effects or as adjuvants for different pathologies [15–17]. In this sense, this review seeks to gather a summary of the information on compounds from RENISUS plants with properties to act in potential biomarkers related to SARS-CoV-2.

2. Methodology

2.1. Search strategy

This systematic review focused on compounds of RENISUS plants with therapeutic properties to combat some SARS-CoV-2 targets. The studies of interest are indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed database. Thus, the scientific names of the 71 plants on the RENISUS list were used as the main search terms, along with the 27 potential biomarkers expressed in SARS-CoV-2 patients [1]: (alpha-1B-glycoprotein (A1BG), beta and gamma-1 actin (ACTB, ACTG1), albumin (ALB), apolipoprotein A-I (APO A-I), complement C1r (C1R), complement C1s (C1S), complement C8 alpha chain (C8A), cluster of differentiation 14 (CD14), complement factor B (CFB), complement factor H (CFH), complement factor I (CFI), C-reactive protein (CRP), fibrinogen alpha chain (FGA), fibrinogen beta chain (FGB), fibrinogen gamma chain (FGG), inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain 3 (ITIH3), inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain 4 (ITIH4), lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP), galectin 3-binding protein (LGALS3BP), leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein (LRG1), serum amyloid A1 (SAA1), serum amyloid A2 (SAA2), haptoglobin (HP), apolipoprotein C1 (APOC1), gelsolin (GSN), transferrin (TF), protein Z-dependent protease inhibitor (SERPINA10), besides SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, coronavirus, spike protein; angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), interleukin 7, and T cells.

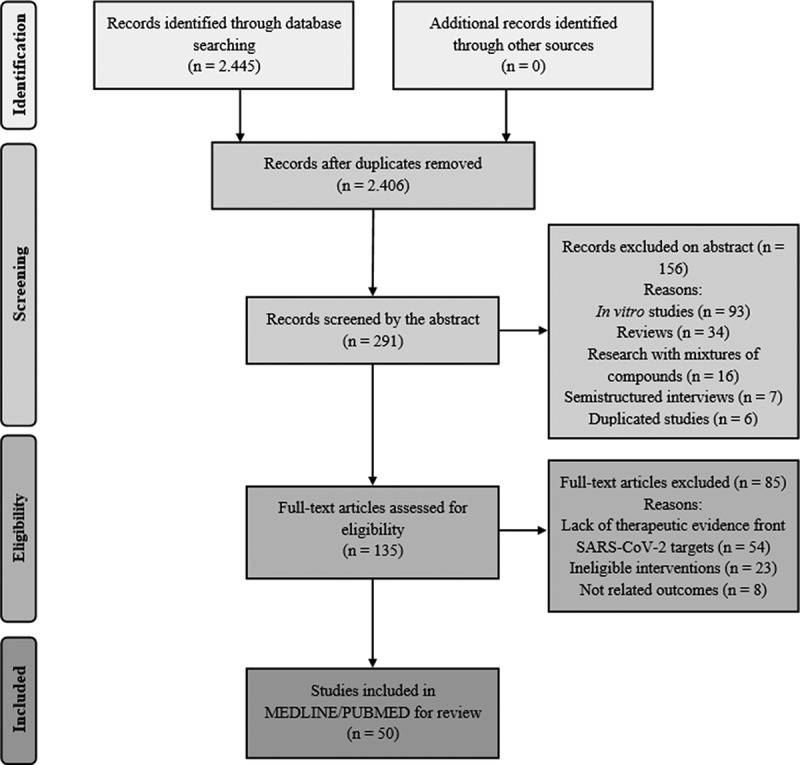

Two reviewers were responsible for searching for publications and analyzing and interpreting the data to carry out this systematic review. All texts with full and open access, regardless of language, published until June 2020, were considered in all stages of the research. The Guideline of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) was used to design this systematic review (Figure 1). The Plant List (TPL) was used to verify the names of species.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the literature search and study selection process

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be considered in this review, studies had to meet the following criteria: preclinical studies or clinical trials (stage one); therapeutic evidence of the compound (stage two); therapeutic effects of the compounds against determined SARS-CoV-2 targets in preclinical (except in vitro studies) or clinical trials (stage three). Reviews, ‘in vitro’ studies, semi structured interviews, commentaries, guideline articles, and research with mixtures of compounds were not computed. Duplicated studies were also excluded at the initial stage. After analyzing the abstract in stage two, the research that did not have therapeutic evidence of the compound was excluded. Studies that were not elected in stage three were excluded due to the lack of therapeutic evidence front SARS-CoV-2 targets analyzed in their entirety. As limitations, risk of bias was considered (e.g. publication bias, as duplicated papers, and ‘in vitro’ studies are not considered; limitation of results found are limited as they are restricted to one database, besides the presence or absence of the keywords used and by the addition of other targets).

3. Results

There are few results in the database using the plants’ scientific names together with the terms ‘SARS-CoV-2,’ ‘COVID-19,’ and ‘coronavirus,’ being that none with therapeutic results so far. In this sense, Table 1 presents the results found with compounds from RENISUS plants with properties to act in potential biomarkers related to SARS-CoV-2.

Table 1.

Selected scientific articles of compounds with therapeutic potential for SARS-CoV-2 targets

| Compound/concentration | Main results | Type of study |

|---|---|---|

| Flavonoid artemetin (0.75 and 1.5 mg/kg) (Achillea millefolium L. – Asteraceae) | Intravenous injection of artemetin in anesthetized rats significantly reduced the hypertensive response to angiotensin I. Artemetin (1.5 mg/kg) was also able to reduce plasma (37%) and vascular (63%) angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) activity. These effects may be associated of ability to decrease angiotensin II generation in vivo, by ACE inhibition | Preclinical in vivo [39] |

| Allyl disulfide and alyl trisulfide/concentration not informed (Allium sativum L. – Amaryllidaceae) | Organosulfur compounds found in garlic essential oil have inhibitory effect in amino acids of the ACE2 protein and the main protease PDB6LU7 of SARS-CoV-2 | Molecular docking [40] |

| Allicin (15, 30 and 45 mg · kg-1 · day-1) via daily intra-gastric gavage for 12 weeks (A. sativum) | In streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats, allicin reversed the albuminuria STZ-induced diabetic rats | Preclinical in vivo [44] |

| 1% high cholesterol diet (HCD) plus allicin (10 mg/kg/day) for 4 weeks (A. sativum) | In rabbits, allicin supplementation significantly decreased serum CRP and significantly protected against HCD-induced attenuation of rabbit aortic | Preclinical in vivo [51] |

| Diallyl sulfide (DAS) and diallyl disulfide (DADS) (200 µM was administrated twice orally with an interval of 12 h) for 5 consecutive days (A. sativum) | DAS or DADS given twice significantly decreased the plasma levels of IL-6 and significantly reduced the plasma levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) in diabetic mice | Preclinical in vivo [36] |

| DAS (100 mg/kg) was orally administered for 4 days (A. sativum) | DAS afforded renal and neuroprotection against cyclophosphamide (CP)-induced nephropathic encephalopathy in rats due to its capacity to significantly decrease CRP and IL-6 levels | Preclinical in vivo [52] |

| The intraperitoneally injected with 1 mL of CSE on days 1, 8, and 15 along with the daily injection of DADS (100 and 10 mg/kg/day) for 21 days (A. sativum) | In rat emphysema model by intraperitoneal injection of cigarette smoke extract (CSE), DADS exerted an anti-inflammation effect on emphysema rats through suppressing IL-6 cytokine production. Furthermore, the regulation effects of DADS on CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cells were observed | Preclinical in vivo [37] |

| 13 mL of rapeseed oil enriched with 0.23 mL DADS (100 mmol/L) intragastrically (A. sativum) | Stimulation of ferritin at the RNA and protein levels was found in rats administered a DADS-enriched oil solution. The expression of the transferrin receptor, an iron transporter, was also enhanced by DADS in rat liver | Preclinical in vivo [38] |

| S-allycysteine (SAC) was administered orally (150 mg/kg b.w/rat) for 45 days (A. sativum) | The levels of albumin were increased in SAC treated diabetic rats | Preclinical in vivo [45] |

| SAC (150 mg/kg b.w/rat) in aqueous solution orally for 45 days (A. sativum) | The levels of transferrin in tissues were increased in SAC-treated STZ-induced diabetic rats, suggest that SAC could have a protective effect against alterations in oxidative stress induced iron metabolism in the diabetic state | Preclinical in vivo [56] |

| Two intraperitoneally injections of aloe-emodin (50 mg/kg; CCl4+ aloe-emodin) (Aloe vera L. – Asphodelaceae) | In a rat model of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) intoxication six rats treated with aloe-emodin, albumin mRNA expression was significantly lower only in the liver of CCl4 rats | Preclinical in vivo [46] |

| Cytopiloyne at 25 µg/kg body weight three times per week (Bidens pilosa L. – Asteraceae) | Cytopiloyne promotes the differentiation of type 2 Th cells, which is consistent with it enhancing GATA-3 transcription. Also, does not compromise total antibodies (Ab) responses mediated by T cells in female NOD mice | Preclinical in vivo [57] |

| Centaurein (75 µg/ml) (B. pilosa) | Centaurein regulated IFN-gamma (IFN-γ) transcription, probably via Nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) and factor nuclear kappa B (NF-kB) in T cells | Preclinical in vivo [58] |

| C57BL/6 J mice were intraperitoneally injected with centaurein at 20 μg (B. pilosa) | Centaurein increased the IFN-γ expression in T and NK cells and the serum IFN-γ level in mice. Centaurein elevated the transcription of T-bet which is consistent with its effect on that of IFN-γ | Preclinical in vivo [59] |

| C1 (1E,6E)-1,2,6,7-tetrahydroxy-1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl) hepta-1,6-diene-3,5-dione) and C2 (4Z,6E)-1,5-dihydroxy-1,7-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl) hepta-4,6-dien-3-one (Curcuma longa L. – Zingiberaceae) | Compounds C1 and C2 showed minimum binding score (−9.08 and −8.07 kcal/mole) against Mpro protein (protease (Mpro) of the SARS-CoV2). These two compounds strongly bind to the catalytic core of the Mpro protein with higher efficacy than lopinavir, a standard antiretroviral of the protease inhibitor class | X-ray crystallographic structure [67] |

| Bioavailable curcumin diet (protein 34.2%, fat 16.5%, starch 28%, Bio-curcumin (BCM-95; Frutarom, Londerzeel, Belgium) 0.09% diet) (C. longa) | Eight obese cats were fed to diet for two 8-week periods (cross-over study design) while maintaining animals in an obese state. Curcumin resulted in lower plasma α1-acid glycoprotein (AGP) concentration but not changed haptoglobin levels | Clinical trial [30] |

| 500 mg curcumin capsules (total: 1,000 mg) twice daily for 12 weeks (C. longa) | In 34 β-thalassemia patients, curcumin treatment significantly reduced serum levels of nontransferrin bound iron (NTBI), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and not affected the transferrin saturation | Randomized controlled trial [31] |

| 1,500-mg curcumin daily for 10 weeks (C. longa) | In 22 patients with Type 2 diabetes, curcumin treatment the mean concentration of high-sensitivity CRP besides serum concentrations of triglyceride decreased | Randomized controlled trial [32] |

| Curcuminoids (500 mg TID per oral; n = 45) for a period of 4 weeks (C. longa) | Curcuminoids were significantly efficacious in modulating all assessed inflammatory mediators: IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), CRP, calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP), substance P and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) in 45 male subjects who were suffering from chronic sulfur mustard-induced pulmonary complications | Randomized controlled trial [53] |

| Curcumin thrice a week at a dose level of 50 mg/kg b.w were administered for 9 consecutive weeks (C. longa) | In 8 rats curcumin treatment effectively reduced the IL-6 and CRP levels in blood serum prevented the Benzo(a)pyrene-induced lung injury | Preclinical in vivo [33] |

| 500 mg (one capsule) of curcumin with each meal (three times/day after meal) for 16 weeks (C. longa) | During the trial (4 months) in 23 patients with T2DM, the curcumin treatment significantly reversed albuminuria | Randomized controlled trial [34] |

| 200 µg of curcumin was i.p. injected daily until day 6 (C. longa) | In mice, curcumin significantly increased CXCR5 + B-cell lymphoma 6+ TFH cells and CD95+ GL-7+ germinal center B cells in draining lymph nodes. Total Ab production as well as high affinity Immunoglobulin G (IgG1 and IgG2b) Ab production was induced | Preclinical in vivo [35] |

| Tetrahydrocurcumin (THC) 120 mg/kg per day, and 1 kg of the AIN 93 G diet contained 800 mg of THC, day 0 to day 25 (C. longa) | THC had beneficial effects on 13 asthmatic mice such pathological changes (eosinophils hyper-production), Th17 and T cell subsets and attenuating the Th2 response | Preclinical in vivo [60] |

| Diet containing 1% curcumin until the end of the study (C. longa) | In New Zealand Black/White F1 female mice starting at 18 weeks of age with lupus nephritis (LN), curcumin induced the protective effects at least in part by its interaction with regulatory T (Treg) cells | Preclinical in vivo [18] |

| Trans-anethole (FEO) (130 mg/kg FEO, thrice weekly for 1 week, by rubbing on shaved rat dorsal area) (Foeniculum vulgare Mill. – Apiaceae) | In six rats, hepatic dysfunction study indicates promising significant amelioration of liver function reflected in ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), bilirubin, albumin plasma levels by FEO treatment | Preclinical in vivo [47] |

| Trans-anethole (FEO) (36.4, 72.8 or 145.6 mg/kg) once per day for 7 consecutive days (F. vulgare) | In acute lung injury (ALI)-bearing mice, FEO treatment eliminated LPS‑induced histopathological changes, decreased the number of inflammatory cells, and reduced in IL-17 mRNA expression. In addition, trans‑anethole increased IL-10 mRNA expression in lung tissues and resulted in a marked elevation in Treg cells and reduction in Th17 cells in spleen tissues | Preclinical in vivo [61] |

| Pinitol (0.05%, P-I and 0.1% pinitol, P-II) for 10 weeks (Glycine max L. Merrill – Fabaceae) | Pinitol supplementation with a high cholesterol (HFHC) diet (10% coconut oil plus 0.2% cholesterol) in hamsters fed-high fat was very effective on the elevation of antiatherogenic factors, including plasma HDL-cholesterol, apolipoprotein A-I (APO A-I), adiponectin, and paraoxonase (PON) activity | Preclinical in vivo [66] |

| 56 mg isoflavones/day for 17 day each with a 25-day washout period between treatments (G. max) | In 22 young healthy, normolipidemic subjects (5 men and 17 women) soy protein with intact phytoestrogens (contained 0.9 mg (3.5 µM) daidzein and 1.0 mg (3.7 µM) genistein) increases HDL-cholesterol and APO A-I concentrations | Controlled trial [20] |

| Isoflavone (80 mg day-1, n = 100) for 24 weeks (G. max) | In patients with ischemic stroke isoflavone therapy caused a significant decrease in serum levels of CRP and IL-6 levels | Randomized controlled trial [21] |

| Isoflavone (80 mg/day, n = 50) for 12 weeks (G. max) | In patients with prior ischemic stroke, isoflavone treatment resulted in a significant decrease in serum CRP levels and improved brachial flow-mediated dilatation in patients with clinically manifest atherosclerosis, thus reversing their endothelial dysfunction status | Randomized controlled trial [22] |

| Soy isoflavones (genistein) 40 mg/day for 6 months (G. max) | Genistein does not interfere in high-sensitive serum CRP levels in 20 healthy postmenopausal women | Randomized controlled trial [23] |

| Genistein (0.5, 1.0, or 2.0 mg (kg body mass) (−1); by subcutaneous injection) for 8 weeks (G. max) | In the liver injury induced in rats by thioacetamide revealed that the treatment of genistein decreased the elevated serum levels of AST, ALT and total and direct bilirubin, and increased the serum level of albumin | Preclinical in vivo [24] |

| Genistein (300 mg/kg/day) was administered orally for 24 weeks (G. max) | In streptozotocin STZ-induced diabetic rats, administration of genistein resulted in a decrease in blood glucose, % glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), CRP and in augmentation of total antioxidant reserve of the hearts | Preclinical in vivo [25] |

| Genistein (20 mg/kg) administered 10 days before to 10 days after the tumor induction (G. max) | In adult female C57BL/6 mice, genistein significantly increased lymphocyte proliferation and LDH release. Furthermore, the treatment caused a significant increment in IFN-γ levels and achieved significant therapeutic effect in tumor model of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) associated-cervical cancer | Preclinical in vivo [26] |

| Active compound soybean ACE2 inhibitor (ACE2iSB) (G. max) | ACE2iSB strongly inhibited recombinant human (rh)ACE2 activity with an IC50 value of 84 nM. This is the first demonstration of an ACE2 inhibitor by HPLC-MS with fluorescence detection | HPLC-MS [41] |

| Daidzein (DAZ) at 10 mg/kg body weight dose by oral gavage daily for six weeks (G. max) | Adult Balb/c mice treated with DAZ increased the percentage of CD4⁺CD28⁺ T cells and DAZ also regulated B lymphopoesis | Preclinical in vivo [27] |

| Orally administered DAZ at various physiological doses (2–20 mg/kg body weight) during adulthood (G. max) | DAZ in female B6C3F1 mice, the T cell populations (CD3+ IgM-, CD4+ CD8- and CD4-CD8+) were increased. The activities cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells were not altered. In NOD mice, DAZ modulated the antibody production, as shown by increased levels of IgG2b and IgG1. DAZ increased CD8+ CD25+ splenocytes in NOD females | Preclinical in vivo [28] |

| Intraperitoneally (IP) injection with lunasin at 0.4 or 4 mg/kg body weight (G. max) | In BALB/c mice lunasin inhibited the growth of (OVA) ovalbumin-expressing A20 B-lymphomas, which was correlated with OVA-specific CD8 + T cells. In addition, lunasin was an effective adjuvant for immunization with OVA, which together improved animal survival against lethal challenge with influenza virus expressing the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I OVA peptide SIINFEKL (PR8-OTI) | Preclinical in vivo [62] |

| Equol 20 mg/kg for 3 days by gavage (G. max) | In BALB/c mice treated with equol showed a significantly higher level of OVA-specific IgE. IL-13 (produced mainly by CD4⁺ T cells) production level was significantly higher than that control | Preclinical in vivo [29] |

| 7S globulin (Momordica charantia L. – Cucurbitaceae) | Study revealed that a tripeptide (VFK) from 7S globulin possess a higher binding affinity for ACE than reported drug Lisinopril (LPR) | Not mentioned [42] |

| Lectin 100 µg/ml (M. charantia) | Lectin is a T cell-independent B cell activator and a polyclonal immunoglobulin (Ig) inducer in BALB/c mice. Additionally, lectin was shown to upregulate the cell activation marker CD86, in a B cell subpopulation | Preclinical in vivo [63] |

| MAP30 (anti-HIV protein) 1 µM (M. charantia) | MAP30 was capable of inhibiting infection of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) in T lymphocytes and monocytes as well as replication of the virus in already-infected cells. Integration of viral DNA into the host chromosome is a vital step in the replicative cycle of retroviruses, including the AIDS virus. The inhibition of HIV-1 integrase by MAP30 suggests that impediment of viral DNA integration may play a key role in the anti-HIV activity | Genomic studies [19] |

| 1-Deoxynojirimycin (DNJ) 10 mg daily for 4 weeks (Morus indica L. – Moraceae) | In 72 patients with with coronary heart disease (CHD) and blood stasis syndrome (BSS) DNJ significantly reduced the levels of CRP, IL-6, TNF-α, malondialdehyde (MDA), Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD) and BSS scores and increased superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels | Randomized controlled trial [54] |

| Phyllanthin and hypophyllanthin (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg) for next 28 day (Phyllanthus amarus Schumach. & Thonn. – Euphorbiaceae) | In Sprague Dawley rats by OVA-challenged, compounds significantly decreased the levels of albumin in serum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and lungs. OVA-induced increase in IgE, oxidative-stress (SOD, GSH, MDA, NO, Nrf2 and iNOs), inflammatory makers (HO-1, TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) levels were significantly decreased by compounds | Preclinical in vivo [48] |

| Geraniin 5 mg/kg was orally administered once (P. amarus) | Spontaneously hypertensive rats, the geraniin showed antihypertensive activity in lowering systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure. Geraniin also showed dose-dependent inhibitory activities against ACE (IC50 were 13.22 µM) | Preclinical in vivo [43] |

| (-)-Epicatechin 50 mg/kg body weight for 21 days (Phyllanthus niruri L. – Euphorbiaceae) | Albumin levels are depleted in hepatitic rats, (-)-epicatechin pretreatment increased albumin levels. Also, pretreatment decreased the tissue damage in hepatitis condition | Pre-clinical in vivo [49] |

| Punicalagin (10, 20, and 40 mg/kg/day, i.p.) for 11 days (Punica granatum L. – Lythraceae) | Acrylamide-induce toxicity in rat and decrease levels of serum protein and albumin concentration. Punicalagin recovered these levels | Preclinical in vivo [50] |

| 10-dehydrogingerdione (10 mg/kg body weight orally, see isolation and purification) (Zingiber officinale Roscoe – Zingiberaceae) | Six New Zealand male rabbits 10-dehydrogingerdione-treated daily during the 6 weeks showed a significant improvement in serum lipids and this effect was correlated to its ability to lower high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), homocysteine and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) levels | Preclinical in vivo [55] |

| Zerumbone (0.1, 1, and 10 mg/kg of body weight) orally fed from days 23 to 39 (Z. officinale) | In BALB/c mice asthmatic model compared to OVA-induced hallmarks of asthma, zerumbone induced higher IgG2a antibody production and promoted Th1 cytokine IFN-γ production | Preclinical in vivo [64] |

| 6-Gingerol (0.01%)-containing drinking water until the end of the experiments (100 days) (Z. officinale) | In female Balb/c and C57BL/6 (8–10 mice), 6-gingerol treatment caused massive infiltration of CD4 and CD8 T-cells and B220(+) B-cells, but reduced the number of CD4(+) Foxp3(+) regulatory T-cells | Preclinical in vivo [65] |

Source: Research data, 2021.

The research found studies of interest with 14 plants from RENISUS list, two of them (A. vera and G. max) are available for free as herbal medicines in the Brazilian Health System (SUS) [13]. As the search for new treatments is urgent, the evaluation focuses on compounds and not plants or their extracts. Through this, the search selected studies with results against SARS-CoV-2 targets with 34 different compounds (Table 1).

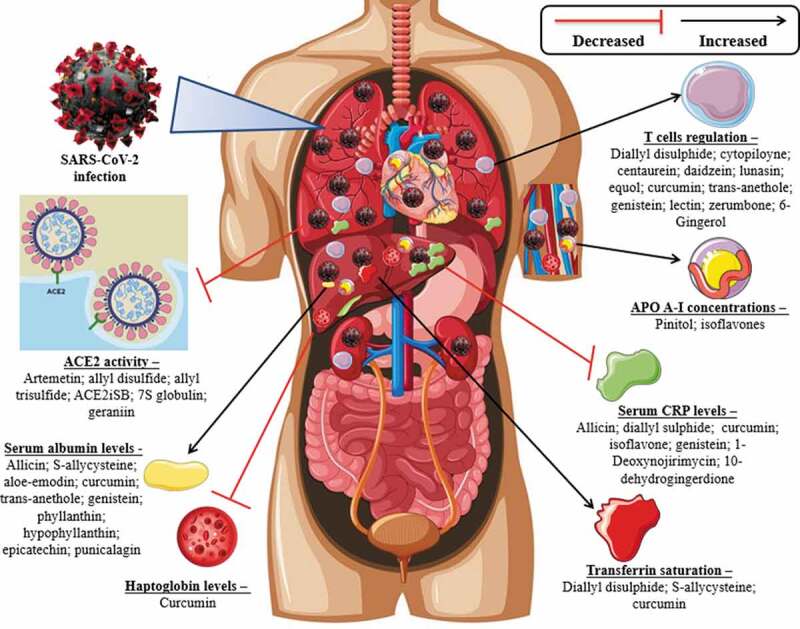

The compounds with the highest concentration of studies are soy isoflavones (genistein, daidzein and equol) [20–29], curcumin [30–35] and diallyl disulfide [36–38]. Among the 31 SARS-CoV-2 targets analyzed (Figure 2

Figure 2.

Main activities of compounds against SARS-CoV-2 targets

), studies were found for ACE activity [39–43], reverted serum albumin levels [24,34,44–50], decreased of the plasma levels of CRP [21–23,25,32,33,36,51–55], transferrin saturation [31,38,56], T cells regulation [25–29,35,37,57–65], haptoglobin levels decreased [30], APO A-I concentrations decreased [20,66]. Compounds of interest reversed these activities, but in contexts unrelated to SARS-CoV-2, except for two studies. One suggests the inhibitory effect of the compounds Allyl disulfide and Allyl trisulfide in amino acids of the ACE2 protein and the main protease PDB6LU7 of SARS-CoV-2 [40]. The other suggests a strong bind of two compounds of C. longa (C1 and C2) to the catalytic core of the Mpro protein (one of the main proteases of the SARS-CoV-2) [67]. In view of these results, Figure 3 presents a scheme that summarizes these results with the aim to better understand the action of compounds against SARS-CoV-2.

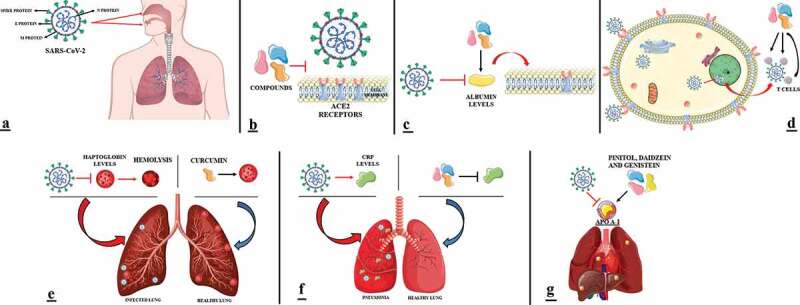

Figure 3.

Scheme of phytoconstituents action in SARS-CoV-2. (A) SARS-CoV-2 enters through oral and respiratory mucosal cells. (B) Inhibitor compounds block the binding of the spike protein to the ACE2 surface. (C) SARS-CoV-2 downregulates albumin levels. Compounds induce serum albumin levels regulation. Albumin induce the decreased expression of the ACE2 receptors. (D) Through the spike protein, SARS-CoV-2 binds to the ACE2 surface and enters the cell epithelium, where it will fuse with the vesicle and release its RNA in the nucleus to reproduce. The new copies of the virus will be detected by T cells induced by compounds that bind to the spike protein to fight the virus’s action. (E) SARS-CoV-2 downregulates haptoglobin levels that induce thus, the presence of hemolysis. Compounds did not change haptoglobin levels. (F) SARS-CoV-2 induces increased CRP levels. Compounds decreased the plasma levels of CRP. (G) SARS-CoV-2 downregulates APO A-I levels. Compounds induce an increase in APO A-I concentrations

4. Discussion

The update by Newman and Cragg (2020) reports that, from the total number of new chemical entities (NCEs) released between 1981–2019 (1,881), 53% are either a natural product or derived from one. From the 186 molecules discovered in this period about antiviral agents, 19% come from natural products and their derivatives. Many approved agents are vaccines, often directed against various influenza serotypes, as expected from the many flu outbreaks [68].

In a previous research, it was reported that traditional herbal remedies could help to improve symptoms, life‐quality, absorptions of pulmonary infiltrations, and decrease corticosteroids uses in SARS patients [69]. Some of the compounds suggested in this review with activity against SARS-CoV-2 targets are already described with antiviral properties. Garlic is known for its antiviral properties due to the activity of its compounds. For example, allyl disulfide strongly decreased cell proliferation of HIV-infected cells [70]. In vivo experiment with allicin, compound exhibited the antiviral activity against influenza viruses by improving the production of neutralizing antibodies when given to mice [71]. Moreover, DADS was effective against the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) replication and viral immediate-early gene expression. It acts by enhancing NK-cells activity that destroys virus-infected cells [72]. Preclinical data show that all these antiviral activities of garlic and its active organosulfur compounds are related to cell signaling process, such, downregulating the extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, block of viral entry into host cells, inhibition viral RNA polymerase, reverse transcriptase, as well as through DNA synthesis and immediate-early gene 1 (IEG1) transcription. Also, clinical trials further demonstrated a prophylactic effect of garlic in the prevention of viral infections through enhancing the immune response [73]. In this review, we found a study that indicates the regulation effects of DADS on CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cells [37]. Another compound with well-established antiviral properties is curcumin. An in vivo study on a mouse model with intravaginal HSV-2 showed significant protection against HSV-2 infection due to curcumin administration [74]. Curcumin exerts its antiviral effects through signaling pathways, such as actin filament organization by replication inhibition in dengue virus and viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus; anti-inflammation and antioxidation activity inhibiting HIV replication; conformation of viral/cellular surface proteins through viral attachment in Zika virus, chikungunya virus, vesicular stomatitis virus, and human respiratory syncytial virus; HSC71 expression induces viral entry block in viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus; NF-κB signaling induce inhibition the replication and viral egress in Influenza A virus and HSV-2 [75]. We found nine surveys showing curcumin activity against SARS-CoV-2 targets. According to this review, curcumin did not affect the transferrin saturation [31], induced an increase in the regulation of T cells [25,35,60], decreased the mean concentration of CRP protein [32,33,53], and reverted albuminuria levels [34], and did not change haptoglobin levels [30]. Haptoglobin, an acute-phase protein, is produced by hepatocytes and, also by lung epithelial cells. Its levels decrease in patients with SARS-CoV-2 and indicate the presence of hemolysis within the body (Figure 3E). Haptoglobin reduces bronchial hyperreactivity [76]. In parallel, as both the host and pathogen require iron, the innate immune response seeks to control iron metabolism to limit its availability during infection. In patients with SARS-CoV-2, low transferrin saturation is observed because many viruses use the transferrin receptor to enter cells [77].

The different isoflavones exert antiviral properties against a wide range of viruses. The mechanisms of antiviral action of isoflavones have not been fully elucidated, but current results suggest a combination of effects on both the virus and the host cell. It is described that isoflavones to affect virus binding, entry, replication, viral protein translation and formation of certain virus envelope glycoprotein complexes. Also tamper in a variety of host cell signaling processes, including induction of gene transcription factors and secretion of cytokines [11]. Genistein is the most studied soy isoflavone in this regard. It has been shown to inhibit the infectivity of various viruses affecting humans and animals, including adenovirus, herpes simplex virus, HIV, respiratory syndrome virus, and rotavirus [11], besides against a previous coronavirus strain (SARS-CoV). In this review, in vivo studies indicate that administration of genistein resulted in a decrease in CRP levels [25], modulated an increase in T cells (lymphocyte proliferation) and a significant increment in IFN-γ levels that showed a significant therapeutic effect in a tumor model of HPV [22]. Besides, it increased APO A-I concentrations in young, healthy people [20], and induces an increase in serum level of albumin [24]. Researchers who studied the clinical characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 patients have reported that lower serum albumin levels were associated with an increased risk of death [78]. Also, albumin downregulates the expression of the ACE2 receptors and has been shown to improve the ratio of the partial pressure arterial oxygen and fraction of inspired oxygen in patients (Figure 3C) [79]. In this review was found one research that suggests serum albumin levels regulation by aloe-emodin action [46], which is a biologically active component of A. vera, and this compound has previously shown potential for SARS-CoV-2. Phenolics such as aloe-emodin, hesperetin, quercetin, naringenin, emodin, and chrysophanol were examined for their capacity against cleavage of the SARS-CoV 3 CLpro. Study showed that aloe-emodin and hesperetin were able to block cleavage of SARS-CoV 3CLpro dose-dependently manner [80]. Another important factor is that the increased level of plasma CRP was positively correlated to the severity of COVID-19 pneumonia (Figure 3F). Clinically, increased CRP levels might be early indicators of infections in SARS-CoV-2 patients who had a slow recovery and might aid physicians to administer antibiotics treatment early [81]. It is also known that APO A-I is the largest component of the HDL particle, considered as a marker of cardiovascular risk. In this sense, a low serum level of apolipoprotein A1 is an indicator of severity in SARS-CoV-2 patients (Figure 3G) [82]. Many patients have underlying cardiovascular disease (CVD) or develop acute cardiac injury during the infection. Acute cardiac injury, defined as a significant elevation of cardiac troponins, is the most reported cardiac abnormality in SARS-CoV-2 [83].

There are several vaccines under study, and some have already been approved by regulatory agencies. Two vaccines published the results of phase III of the study with more 90% of effectiveness. Both studies showed that the vaccines are safe and induced the immune response by T cell activity [84,85]. In our review, the compounds DADS [37], cytopiloyne [57], centaurein [58,59], curcumin [25,35,60], trans-anethole [61], daidzein isoflavone [27,28], genistein [26], equol isoflavone [29], zerumbone [64], 6-Gingerol [65], lectin [63], and lunasin [62] stimulate T cell responses (Figure 3D). Lectin has previously show effective against influenza virus [86], and peptide lunasin, for example, in BALB/c mice, improved survival in infected animals with the influenza virus, which suggests that lunasin can promote dendritic cells (DCs) maturation, increasing the development of protective immune responses to the vaccine antigens [62]. U.S. researchers demonstrated that both CD4 + and CD8 + T lymphocytes were able to recognize proteins not only Spike protein but also other proteins from SARS-CoV-2. When found these peptides, T cells were activated and produced cytokines, a sign that recognition was functional [87]. Swedish researchers analyzed frozen T cells from blood donors who donated in 2019 (before the pandemic) and after the start in 2020. Assessing the frequency of T cells capable of activating by recognizing the viral peptide megapool, the researchers demonstrated that this recognition was rare in blood donor cells in 2019, but relatively frequent in individuals who donated in 2020, suggesting prior contact with the virus that may have resulted in specific T cells. But the curious fact was that most of the individuals who lived with infected patients had a relatively high frequency of T cells recognizing megapool peptides, suggesting that these exposed individuals had generated T responses against the virus (potentially protective) even though they were asymptomatic [88]. These individuals are presumed to have T cells capable of recognizing SARS-CoV-2 even before encountering the virus. This hypothesis is based on the concept that similar pathogens (SARS-CoV or other influenza viruses such as influenza) often have equal portions of proteins, and a T response against a peptide derived from a protein with identical sequence in different pathogens can lead to a cross recognition [89]. This cross-recognition with other coronaviruses was exactly what other recent papers have shown. The data from these studies indicate that the S, N, NSP3, NSP4, ORF3a, ORF8, NSP7, NSP13 and probably other proteins from SARS-CoV-2 are recognized when peptides are used to stimulate T cells of individuals never exposed to SARS- CoV-2 [90,91]. In this sense, it is imagined that preexisting T cells could limit the intensity of the infection or even prevent the patient from becoming seriously ill when exposed to the new coronavirus. There is also the possibility that having a previous T response may be harmful and that preexisting anti-SARS-CoV-2 cells may cause further inflammation and increase the severity of the disease. However, there is no evidence to pinpoint this T-cell pre-response as potentially harmful. The most likely hypothesis, therefore, is that of protection, even if partial [92].

This cross recognition is a hope now that COVID-19 has entered perilous phase, because after initially containing SARS-CoV-2 infection, many countries had a resurgence of COVID-19 levels consistent with a large proportion of the population remaining susceptible to the virus after the first epidemic wave. This is due to new variants of the virus, such as the strain of Brazil, first discovered in Manaus, and which spread rapidly with rates up to 10 times higher in virulence, impacting on greater contagion and consequently higher mortality rate, also due to the low vaccination rate so far in countries like Brazil [93]. Finally, it should be noted that each study of interest in this review points out the compounds’ activity generally for a selected target. However, it is important to emphasize that the therapeutic approach for SARS-CoV-2 is broader and more complex. Our approach focused on a specific group of compounds and SARS-CoV-2 targets that may be the product of reactions caused by infection, but there are hundreds of other compounds with potential besides genes related to COVID-19 being analyzed [94].

5. Conclusion

Even though vaccines are being developed, new therapeutic alternatives for SARS-CoV-2 are essential, since compounds extracted from plants present a diverse range of therapeutic activities, including antiviral properties that may be beneficial to act on SARS-CoV-2 targets. The direct benefit of most of these compounds is that their effects on the human body and their safety are already established through clinical trials for another diseases. However, as most of the studies selected in this review did not evaluate the direct compounds’ behavior against SARS-CoV-2, the compounds need to be tested under specific SARS-CoV-2 conditions. Thus, utmost care is required while prescribing the phytocompounds as their uncontrolled use can have long-term side effects on the patient’s body. In this sense, the search for new substances makes it possible to find ‘old compounds’ with new mechanisms of action or reveal new functional groups. We hope this compilation will help researchers and clinicians to identify the appropriate antiviral compounds for combating COVID-19 and contribute to save millions of human lives.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the University of Taquari Valley, Brazil.

Funding Statement

This study was financed in part by the Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - Brazil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001 and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Article Highlights

Researchers have found essential proteins in the blood of people infected with SARS-CoV-2 that can act as biomarkers that predict how severe the disease can get.

Most of the studies selected in this review did not evaluate the direct compounds’ behavior against SARS-CoV-2.

Care is required while prescribing phytocompounds as their uncontrolled use can have long-term side effects.

The immune-modulatory effect makes T cells a potential tool for the antiviral drug-discovery.

The compounds offer therapeutic options to fight the SARS-CoV-2 infection.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Messner CB, Demichev V, Wendisch D, et al. Ultra-high-throughput clinical proteomics reveals classifiers of COVID-19 infection. Cell Syst . 2020;11(1):11–24. e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This paper guides the conduct of this review because it shows proteins (targets) that are present at different levels in SARS-CoV-2 patients, depending on severity of their symptoms.

- 2.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang S, Hillyer C, Du L.. Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and other human coronaviruses. Trends Immunol. 2020;41(6):545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu H, Zhong L, Deng J, et al. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12(1):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vardhana SA, Wolchok JD. The many faces of the anti-COVID immune response. J Exp Med. 2020;217(6):e20200678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamilloux Y, Henry T, Belot A, et al. Should we stimulate or suppress immune responses in COVID-19? Cytokine and anti-cytokine interventions. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19(7):102567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li H, Zhou Y, Zhang M, et al. Updated approaches against SARS-CoV-2. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64(6):e00483–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vellingiria B, Jayaramayya K, Iyer M, et al. COVID-19: a promising cure for the global panic. Sci Total Environ. 2020;725:138277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majnooni MB, Fakhri S, Shokoohinia Y, et al. Phytochemicals: potential therapeutic interventions against coronavirus-associated lung injury. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:588467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel A, Rajendran M, Shah A, et al. Virtual screening of curcumin and its analogs against the spike surface glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;1–9. DOI: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1868338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andres A, Donovan SM, Kuhlenschmidt MS. Soy isoflavones and virus infections. J Nutr Biochem. 2009;20(8):563–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao PSS, Midde NM, Miller DD, et al. Diallyl sulfide: potential use in novel therapeutic interventions in alcohol, drugs, and disease mediated cellular toxicity by targeting cytochrome P450 2E1. Curr Drug Metab. 2015;16(6):486–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brazil . Ministério da Saúde. Portal da Saúde: relação Nacional de Medicamentos Essenciais (RENAME). 2020. [cited 2020 Dec]. Available in: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/relacao_medicamentos_rename_2020.pdf

- 14.Marmitt DJ, Bitencourt S, Silva GR, et al. Scientific production of plant species included in the Brazilian national list of medicinalplants of interest to the unified health system (RENISUS) from 2010 to 2013. J Chem Pharm Res. 2016; 8: 123–132 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marmitt DJ, Bitencourt S, Silva ADCE, et al. The healing properties of medicinal plants used in the Brazilian public health system: a systematic review. J Wound Care. 2018a;27(Sup6):S4–S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • References 14 nd 15 present the plants on the RENISUS list, used as keywords in the search for this systematic review.

- 16.Marmitt DJ, Bitencourt S, Silva AC, et al. Medicinal plants used in Brazil public health system with neuroprotective potential – a systematic review. Bol. Latinoam. Caribe Plantas Med. Aromát. 2018b;17:84–103. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marmitt DJ, Bitencourt S, Da Silva GR, et al. RENISUS plants and their potential antitumor effects in clinical trials and registered patents. Nutrit Cancer. 2020;72(7):1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee H, Kim H, Lee G, et al. Curcumin attenuates lupus nephritis upon interaction with regulatory T cells in New Zealand black/white mice. Br J Nut. 2013;110(1):69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee-Huang S, Huang PL, Huang PL, et al. Inhibition of the integrase of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 by anti-HIV plant proteins MAP30 and GAP31. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(19):8818–8822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanders TA, Dean TS, Grainger D, et al. Moderate intakes of intact soy protein rich in isoflavones compared with ethanol-extracted soy protein increase HDL but do not influence transforming growth factor beta (1) concentrations and hemostatic risk factors for coronary heart disease in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76(2):373–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Zhang H. Soybean isoflavones ameliorate ischemic cardiomyopathy by activating Nrf2-mediated antioxidant responses. Food & Funct. 2017;8(8):2935–2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan YH, Lau KK, Yiu KH, et al. Reduction of C-reactive protein with isoflavone supplement reverses endothelial dysfunction in patients with ischaemic stroke. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(22):2800–2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yildiz MF, Kumru S, Godekmerdan A, et al. Effects of raloxifene, hormone therapy, and soy isoflavone on serum high-sensitive C-reactive protein in postmenopausal women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;90(2):128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saleh DO, Abdel Jaleel GA, El-Awdan SA, et al. Thioacetamide-induced liver injury: protective role of genistein. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;92(11):965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta SK, Dongare S, Mathur R, et al. Genistein ameliorates cardiac inflammation and oxidative stress in streptozotocin-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy in rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 2015;408(1–2):63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghaemi A, Soleimanjahi H, Razeghi S, et al. Genistein induces a protective immunomodulatory effect in a mouse model of cervical cancer. Iran J Immunol. 2012;9(2):119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tyagi AM, Srivastava K, Sharan K, et al. Daidzein prevents the increase in CD4+CD28 null T cells and B lymphopoesis in ovariectomized mice: a key mechanism for anti-osteoclastogenic effect. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang G, Xu J, Guo TL. Isoflavone daidzein regulates immune responses in the B6C3F1 and non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice. Int Immunopharmacoly. 2019;71:277–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakai T, Furoku S, Nakamoto M, et al. The soy isoflavone equol enhances antigen-specific IgE production in ovalbumin-immunized BALB/c mice. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2010;56(1):72–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leray V, Freuchet B, Le Bloc’h J, et al. Effect of citrus polyphenol- and curcumin-supplemented diet on inflammatory state in obese cats. Br J Nutr. 2011;106(Suppl 1):S198–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohammadi E, Tamaddoni A, Qujeq D, et al. An investigation of the effects of curcumin on iron overload, hepcidin level, and liver function in β-thalassemia major patients: a double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. Phytother Res. 2018;32(9):1828–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adibian M, Hodaei H, Nikpayam O, et al. The effects of curcumin supplementation on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, serum adiponectin, and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phytother Res. 2019;33(5):1374–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Almatroodi SA, Alrumaihi F, Alsahli MA, et al. (Curcumin, an active constituent of turmeric spice: implication in the prevention of lung injury induced by benzo(a) pyrene (bap) in rats. Molecules. 2020;25(3):724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanaie A, Shahidi S, Iraj B, et al. Curcumin as a major active component of turmeric attenuates proteinuria in patients with overt diabetic nephropathy. J Res Med Sci. 2019;24(1):77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim DH, Lee HG, Choi JM. Curcumin Elevates T(FH) Cells and germinal center B cell response for antibody production in mice. Immune Net. 2019;19(5):e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsao S-M, Liu W-H, Yin M-C. Two diallyl sulphides derived from garlic inhibit meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in diabetic mice. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56(6):803–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Y, Li A, Feng X, et al. Pharmacological investigation of the anti-inflammation and anti-oxidation activities of diallyl disulfide in a rat emphysema model induced by cigarette smoke extract. Nutrients. 2018;10(1):79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas M, Zhang P, Noordine M-L, et al. Diallyl disulfide increases rat H-ferritin, L-ferritin and transferrin receptor genes in vitro in hepatic cells and in vivo in liver. J Nutrit. 2002;132(12):3638–3641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Souza P, Gasparotto JA, Crestani S, et al. Hypotensive mechanism of the extracts and artemetin isolated from Achillea millefolium L. (Asteraceae) in rats. Phytomedicine. 2011;18(10):819–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thuy BTP, My TTA, Hai NTT, et al. Investigation into SARS-CoV-2 resistance of compounds in garlic essential oil. ACS Omega. 2020;5(14):8312–8320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi S, Yoshiya T, Yoshizawa-Kumagaye K, et al. Nicotianamine is a novel angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 inhibitor in soybean. Biomed Res. 2015;36(3):219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kesari P, Pratap S, Dhankhar P, et al. Structural characterization and in-silico analysis of momordica charantia 7S globulin for stability and ACE inhibition. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin S-Y, Wang -C-C, Lu Y-L, et al. Antioxidant, anti-semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase, and anti-hypertensive activities of geraniin isolated from Phyllanthus urinaria. Food and ChemToxicol. 2008;46(7):2485–2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang H, Jiang Y, Mao G, et al. Protective effects of allicin on streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy in rats. J. Sci. Food Agric.. 2017;97(4):1359–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saravanan G, Ponmurugan P. Antidiabetic effect of S-allylcysteine: effect on thyroid hormone and circulatory antioxidant system in experimental diabetic rats. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2012;26(4):280–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arosio B, Gagliano N, Fusaro LM, et al. Aloe-emodin quinone pretreatment reduces acute liver injury induced by carbon tetrachloride. Toxicol Pharmacol. 2000;87(5):229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mostafa DM, Abd El-Alim SH, Asfour MH, et al. Transdermal fennel essential oil nanoemulsions with promising hepatic dysfunction healing effect: in vitro and in vivo study. Pharm Dev Technol. 2019;24(6):729–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu W, Li Y, Jiao Z, et al. Phyllanthin and hypophyllanthin from Phyllanthus amarus ameliorates immune-inflammatory response in ovalbumin-induced asthma: role of IgE, Nrf2, iNOs, TNF-α, and IL’s. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2019;41(1):55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shanmugam B, Shanmugam KR, Ravi S, et al. Exploratory Studies of (-)-epicatechin, a bioactive compound of phyllanthus niruri, on the antioxidant enzymes and oxidative stress markers in d-galactosamine-induced hepatitis in rats: a Study with reference to clinical prospective. PharmacognMagaz. 2017;13(Suppl1):S56–S62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foroutanfar A, Mehri S, Kamyar M, et al. Protective effect of punicalagin, the main polyphenol compound of pomegranate, against acrylamide-induced neurotoxicity and hepatotoxicity in rats. Phytother Res. 2020;34(12):3262–3272. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.El-Sheakh AR, Ghoneim HA, Suddek GM, et al. Attenuation of oxidative stress, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction in hypercholesterolemic rabbits by allicin. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;94(2):216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Galal SM, Mansour HH, Elkhoely AA. Diallyl sulfide alleviates cyclophosphamide-induced nephropathic encephalopathy in rats. Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods. 2020;30(3):208–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Panahi Y, Ghanei M, Bashiri S, et al. Short-term curcuminoid supplementation for chronic pulmonary complications due to sulfur mustard intoxication: positive results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Drug Res. 2015;65(11):567–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma Y, Lv W, Gu Y, et al. 1-Deoxynojirimycin in Mulberry (Morus indica L.) leaves ameliorates stable angina pectoris in patients with coronary heart disease by improving antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capacities. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elseweidy MM, Abdallah FR, Younis NN, et al. 10-Dehydrogingerdione raises HDL-cholesterol through a CETP inhibition and wards off oxidation and inflammation in dyslipidemic rabbits. Atherosclerosis. 2013;231(2):334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saravanan G, Ponmurugan P, Begum MS. Effect of S-allylcysteine, a sulphur containing amino acid on iron metabolism in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2013;27(2):143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chang CL-T, Chang S-L, Lee Y-M, et al. Cytopiloyne, a polyacetylenic glucoside, prevents type 1 diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2007a;178(11):6984–6993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang S-L, Chiang Y-M, Chang CL-T, et al. Flavonoids, centaurein and centaureidin, from Bidens pilosa, stimulate IFN-gamma expression. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007b;112(2):232–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang S-L, Yeh -H-H, Lin Y-S, et al. The effect of centaurein on interferon-gamma expression and Listeria infection in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007c;219(1):54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen BL, Chen YQ, Ma BH, et al. Tetrahydrocurcumin, a major metabolite of curcumin, ameliorates allergic airway inflammation by attenuating Th2 response and suppressing the IL-4Rα-Jak1-STAT6 and Jagged1/Jagged2 -Notch1/Notch2 pathways in asthmatic mice. Clin Exp Allergy. 2018;48(11):1494–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang S, Chen X, Devshilt I, et al. Fennel main constituent, trans‑anethole treatment against LPS‑induced acute lung injury by regulation of Th17/Treg function. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18(2):1369–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tung CY, Lewis DE, Han L, et al. Activation of dendritic cell function by soypeptide lunasin as a novel vaccine adjuvant. Vaccine. 2014;32(42):5411–5419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang L, Adachi T, Shimizu Y, et al. Characterization of lectin isolated from momordica charantia seed as a B cell activator. Immunol Lett. 2008;121(2):148–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shieh Y-H, Huang H-M, Wang -C-C, et al. Zerumbone enhances the Th1 response and ameliorates ovalbumin-induced Th2 responses and airway inflammation in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;24(2):383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ju SA, Park SM, Lee YS, et al. Administration of 6-gingerol greatly enhances the number of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in murine tumors. Int J Cancer. 2012;130(11):2618–2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choi MS, Lee MK, Jung UJ, et al. Metabolic response of soy pinitol on lipid-lowering, antioxidant and hepatoprotective action in hamsters fed-high fat and high cholesterol diet. Mol Nut Food Res. 2009;53(6):751–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gupta S, Singh AK, Kushwaha PP, et al. Identification of potential natural inhibitors of SARS-CoV2 main protease by molecular docking and simulation studies. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020;1-12. DOI: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1776157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J Nat Prod. 2020;83(3):770–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu X, Zhang M, He L, et al. Chinese herbs combined with Western medicine for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(10):CD004882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shoji S, Furuishi K, Yanase R, et al. Allyl compounds selectively killed human immunodeficiency virus (type 1)-infected cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;194(2):610–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sawai T, Itoh Y, Ozaki H, et al. Induction of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte and antibody responses against highly pathogenic avian influenza virus infection in mice by inoculation of apathogenic H5N1 influenza virus particles inactivated with formalin. Immunology. 2008;124(2):155–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhen H, Fang F, Ye D-Y, et al. Experimental study on the action of allitridin against human cytomegalovirus in vitro: inhibitory effects on immediate-early genes. Antiviral Res. 2006;72(1):68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rouf R, Uddin SJ, Sarker DK, et al. Antiviral potential of garlic (Allium sativum) and its organosulfur compounds: a systematic update of pre-clinical and clinical data. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2020;104:219–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bourne KZ, Bourne N, Reising SF, et al. Plant products as topical microbicide candidates: assessment of in vitro and in vivo activity against herpes simplex virus type 2. Antivir Res. 1999;42(3):219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jennings MR, Parks RJ. Curcumin as an antiviral agent. Viruses. 2020;12(11):1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huscenot T, Galland J, Ouvrat M, et al. SARS-CoV-2-associated cold agglutinin disease: a report of two cases. Ann Hematol. 2020;11:1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wessling-Resnick M. Crossing the iron gate: why and how transferrin receptors mediate viral entry. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2018;38(1):431–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu Y, Yang Y, Zhang C, et al. Clinical and biochemical indexes from 2019-nCoV infected patients linked to viral loads and lung injury. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63(3):364–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Uhlig C, Silva PL, Deckert S, et al. Albumin versus crystalloid solutions in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2014;18(1):R10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Orhan IE, Deniz FSS. Natural products as potential leads against coronaviruses: could they be encouraging structural models against SARS CoV‑2? Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2020;10(4):171–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen W, Zheng KI, Liu S, et al. Plasma CRP level is positively associated with the severity of COVID-19. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2020;19(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang Y, Zhu Z, Fan L, et al. Low serum level of apolipoprotein A1 is an indicator of severity in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Europe PMC. 2020; in press. DOI: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-33301/v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bansal M. Cardiovascular disease and COVID-19. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2020;14(3):247–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ramasamy MN, Minassian AM, Ewer KJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine administered in a prime-boost regimen in young and old adults (COV002): a single-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10267):1979–1993. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang Y, Zeng G, Pan H, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in healthy adults aged 18–59 years: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet. 2020. in press. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30843-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • References 84 and 85 show two vaccines already approved for use, that induced the immune response by T cell activity. In this review, 16 studies show that compounds induce the stimulate T cell responses.

- 86.Din M, Ali F, Waris A, et al. Retracted: phytotherapeutic options for the treatment of COVID-19: a concise viewpoint. Phytotherapy Research. 2020;34(10):2431–2437. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 87.Grifoni A, Weiskopf D, Ramirez SI, et al. Targets of T Cell Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus in Humans with COVID-19 Disease and Unexposed Individuals. Cell. 2020;181(7):1489–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sekine T, Perez-Potti A, Rivera-Ballesteros O, et al. Robust T cell immunity in convalescent individuals with asymptomatic or mild COVID-19. Cell. 2020;183(1):158–168.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cui J, Li F, Shi ZL. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(3):181–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Le Bert N, Tan AT, Kunasegaran K, et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell immunity in cases of COVID-19 and SARS, and uninfected controls. Nature. 2020;584(7821):457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mateus J, Grifoni A, Tarke A, et al. Selective and cross-reactive SARS-CoV-2 T cell epitopes in unexposed humans. Science. 2020;370(6512):89–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Long QX, Liu BZ, Deng HJ, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(6):845–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sabino EC, Buss LF, Carvalho MPS, et al. Resurgence of COVID-19 in Manaus, Brazil, despite high seroprevalence. Lancet. 2021;397(10273):P.452–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ruan X, Du P, Zhao K, et al. Mechanism of dayuanyin in the treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. Chinese Med. 2020;15(1):62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]