Abstract

Objective

As COVID-19 spreads across the world, there are concerns that people with asthma are at a higher risk of acquiring the disease, or of poorer outcomes. This systematic review aimed to summarize evidence on the risk of infection, severe illness and death from COVID-19 in people with asthma.

Data sources and study selection

A comprehensive search of electronic databases including preprint repositories and WHO COVID-19 database was conducted (until 26 May 2020). Studies reporting COVID-19 in people with asthma were included. For binary outcomes, we performed Sidik-Jonkman random effects meta-analysis. We explored quantitative heterogeneity by subgroup analyses, meta regression and evaluating the I2 statistic.

Results

Fifty-seven studies with an overall sample size of 587 280 were included. The prevalence of asthma among those infected with COVID-19 was 7.46% (95% CI = 6.25–8.67). Non-severe asthma was more common than severe asthma (9.61% vs. 4.13%). Pooled analysis showed a 14% risk ratio reduction in acquiring COVID-19 (95% CI = 0.80–0.94; p < 0.0001) and 13% reduction in hospitalization with COVID-19 (95% CI = 0.77–0.99, p = 0.03) for people with asthma compared with those without. There was no significant difference in the combined risk of requiring admission to ICU and/or receiving mechanical ventilation for people with asthma (RR = 0.87 95% CI = 0.94–1.37; p = 0.19) and risk of death from COVID-19 (RR = 0.87; 95% CI = 0.68–1.10; p = 0.25).

Conclusion

The findings from this study suggest that the prevalence of people with asthma among COVID-19 patients is similar to the global prevalence of asthma. The overall findings suggest that people with asthma have a lower risk than those without asthma for acquiring COVID-19 and have similar clinical outcomes.

Abbreviations:

- ACE-2:

angiotensin-converting-enzyme-2;

- CDC:

United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention;

- COPD:

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease;

- COVID-19:

coronavirus disease 2019;

- ICU:

intensive care unit;

- ICS:

inhaled corticosteroids;

- MERS:

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome;

- RRR:

relative risk reduction;

- SARS-CoV-1:

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1;

- SARS-CoV-2:

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Keywords: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, novel coronavirus 2019, coronavirus, ventilator support, critical care medicine, meta-analysis, respiratory infections

Introduction

As COVID-19 continues to spread across the world with devastating impact, there are concerns that people with asthma are at a higher risk of acquiring the disease, or of poorer outcomes. This is based on three main factors. Firstly, people with chronic respiratory conditions such as asthma were historically reported to be at higher risk compared to their counterparts during the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), caused by a virus with close sequence homology to SARS-CoV-2 (1). Thus, it appeared likely that this is also the case with COVID-19. Secondly, viral respiratory infections such as coronaviruses are potent triggers of asthma exacerbations (2). Lastly, inhaled and oral corticosteroids, a mainstay treatment for persistent asthma, and for acute exacerbations respectively, may increase susceptibility to COVID-19 infection and its severity (2). While these theories seem plausible, there is limited evidence to support them.

Current evidence shows that asthma is not in the top 10 comorbidities associated with COVID-19 fatalities, with obesity, diabetes and chronic heart disease being most commonly reported (3). This is consistent with trends observed during the SARS-CoV-1 epidemic. Early reports from Wuhan in China suggest that asthma is underrepresented compared to the population prevalence (4). However, the United States Center for Disease Control (CDC) has reported that among younger patients hospitalized for COVID-19, obesity, asthma and diabetes were the most common comorbidities (3).

There have been recommendations from various government agencies (5,6) across the world advising people with asthma to be more cautious and self-isolate longer which affects their livelihood, mental health and quality of life. People with asthma were reported have a higher prevalence of anxiety and stress than non-asthma controls (7). A qualitative study in the United Kingdom among patients with respiratory disease including asthma reported that they were fearful of death if infected with COVID-19 and confused with the mixed messages on shielding they received (8). Additionally despite this advice, evidence for the longer duration of self-isolation for people with asthma is scant. The overall objective of this systematic review is to provide the best available evidence on the risk of infection, severe illness (requiring admission to ICU and/or mechanical ventilation) and death from COVID-19 in people with asthma.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

The protocol of this systematic review was pre-registered and published in PROSPERO (CRD42020185673). All studies on COVID-19 until the 26th of May 2020 were screened for inclusion. The details of the full search strategy and study selection procedures are outlined in Supplementary appendix 1.

Data analysis

Two main sets of meta analyses were performed. To pool the proportions of people with asthma among those with COVID-19, we used the binomial distribution to model the within-study variability and calculated Wilson score test-based confidence intervals.

For all the binary outcomes, we performed Sidik-Jonkman random effects meta-analysis. We assessed the quantitative heterogeneity by conducting a formal test of homogeneity and evaluating the proportion of variability due to heterogeneity (I2). We performed univariable random effects meta regressions including age and the proportion of current and former smokers as covariates, and conducted subgroup analyses by continent (America, Asia, Europe) and by the quality of the studies (low, medium, high).

We performed several sensitivity analyses. For hospitalization, we calculated the number of non-hospitalized patients from the total number of COVID-19 patients in each group subtracted from those hospitalized. As such, we were able to pool a larger number of studies for this outcome. For death, we performed a best-case (all patients not dead were taken as “alive”) and a worst-case analysis (all patients reported as not having yet recovered were taken as “dead”). Lastly, we removed one outlier study (9) from the base-case sensitivity analysis. The assessment of small-study effects were done by regression-based Egger test and eyeball evaluation of the contour-enhanced funnel plots.

In the forest plots along with the pooled effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals, we also reported the prediction intervals (to show the range of true associations that can be expected in future studies) (10). All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 16 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

We identified 34 856 records, of which 34 845 were retrieved through database searching. The selection process is presented in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). Overall, 57 studies (54 references (3,9,11–62)) were included in the report. Of the 57 studies included totaling 587 280 people who were tested for COVID-19, there were 41 cohort studies (25 conducted retrospectively, 15 prospectively and 1 ambispective), 12 case series, 1 case control, 1 RCT, 1 quasi-experimental and 1 diagnostic study. Sample sizes ranged from 8 (34) to 119 528 (21) people. Most of the studies were hospital-based (45 studies) while 6 were studies in the community and 6 with mixed setting. Studies were from Asia (n = 19), Europe (n = 14), North America (n = 22) and South America (n = 2). The summary table of included studies are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA study selection flow chart.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies.

| COVID-19 Positive |

Age (years) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Country | City | Setting | Design | Total Sample Size | Asthma (n) | Overall (n) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Male (n, from overall sample) | Current smokers (n) |

| Peer-reviewed and published | |||||||||||

| Arentz et al. (11) | USA | Washington | Hospital | Prospective Cohort Study | 21 | 2 | 21 | 70b | 11 | ||

| Argenziano et al. (12) | USA | New York | Hospital | Case Series | 1000 | 113 | 1000 | 63 (50–75) | 596 | 49 | |

| Auld et al. (13) | USA | Georgia | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 217 | 19 | 217 | 64 (54–73) | 119 | ||

| Belhadjer et al. (14)c | France, Switzerland | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 35 | 3 | 35 | 10 (2–16) | 18 | |||

| Bhatraju et al. (15) | USA | Seattle | Hospital | Case Series | 24 | 3 | 24 | 64 (18) | 15 | 5 | |

| Borba et al. (16) | Brazil | Hospital | Randomized Controlled Trial | 81 | 4 | 81 | 51.1 (13.9) | 61 | 4 | ||

| Borobia et al. (17) | Spain | Madrid | Hospital | Prospective Cohort Study | 2226 | 115 | 2226 | 61 (46–78) | 1074 | 157 | |

| Docherty et al. (22) | UK | Hospital | Prospective Cohort Study | 20133 | 2540 | 20133 | 73 (58–82) | 12068 | 852 | ||

| Fadel et al. (23) | USA | Michigan | Hospital | Quasi Experimental Study | 213 | 33 | 213 | 62 (51–62) | 109 | 88 | |

| Goyal et al. (24) | USA | New York | Hospital | Case Series | 393 | 49 | 393 | 62.2 (48.6–73.7) | 238 | 20 | |

| Grasselli et al. (25)a | Italy | Lombardy | Hospital | Case Series | 1043 | 29 | 1043 | 63(11) | 838 | ||

| Jacobs et al. (26) | USA | Hospital | Prospective Cohort Study | 32 | 3 | 32 | 52.41 (12.49) | 22 | |||

| Ki et al. (28) | South Korea | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 28 | 1 | 28 | 42 (21–73) | 15 | |||

| Kim et al. (29) | South Korea | Hospital | Case Series | 13 | 1 | 13 | 31 (17.8–55.8) | 6 | |||

| Lechien et al. (30) | France, Italy, Spain, Belgium, Switzerland | Hospital | Prospective Cohort Study | 1420 | 93 | 1420 | 39.17 (12.09) | 458 | 203 | ||

| Li et al. (31) | China | Wuhan | Hospital | Ambispective cohort study | 548 | 5 | 548 | 60 (48–69) | 279 | 41 | |

| Lian et al. (32) | China | Zhejiang Province | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 788 | 6 | 788 | 48.5b | 407 | 54 | |

| Licari et al. (33)c | Italy | South Lombardy and Liguria | Hospital | Case Series | 40 | 1 | 40 | 5 (1–12.5) | 19 | ||

| Ling et al. (34) | Hong Kong | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 8 | 0 | 8 | 64.5 (42–70) | 4 | 1 | ||

| Lokken et al. (35) | USA | Washington | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 46 | 4 | 46 | 29 (26–34) | 0 | 0 | |

| Mahdavinia et al. (36) | USA | Community | Retrospective Cohort Study | 935 | 241 | 935 | 45.71b | 337 | |||

| Merza et al. (38) | Iraq | Hospital | Prospective Cohort Study | 15 | 2 | 15 | 28.06 (16.42) | 9 | |||

| National Committee on Covid-19 Epidemiology (9)a | Iran | Mixed | Retrospective Cohort Study | 14991 | 307 | 14991 | 54.7b | 8544 | |||

| OPEN Safely Collaborative(20) | UK | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 5683 | 911 | 5683 | 49.65b | 3585 | 393 | ||

| Peng et al. (40) | China | Wuhan | Hospital | Case Series | 11 | 1 | 11 | 61 (51–69) | 8 | 6 | |

| Pongpirul et al. (41) | Thailand | Bangkok | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 11 | 0 | 11 | 61 (28–74) | 6 | 0 | |

| Richardson et al. (45) | USA | New York | Hospital | Case Series | 5700 | 479 | 5700 | 63 (52–75) | 3437 | 2691 | |

| Sun et al. (50) | China | Beijing | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 63 | 2 | 63 | 47 (3–85) | 37 | ||

| Tomlins et al. (51) | UK | North Bristol | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 95 | 21 | 95 | 75 (59–82) | 60 | ||

| Wang et al. (52) | China | Shenzhen | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 55 | 1 | 55 | 49 (2–69) | 22 | ||

| Wei et al. (54) | China | Wuhan | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 14 | 1 | 14 | 36 (±6) | 4 | 0 | |

| Wichmann et al. (56) | Germany | Hamburg | Hospital | Prospective Cohort Study | 12 | 2 | 12 | 73 (52–87) | 9 | ||

| Wu et al. (57)a | China | Jiangsu Province | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 80 | 0 | 80 | 46.1 (15.42) | 39 | ||

| Yasukawa et al. (58) | USA | Washington | Hospital | Case Series | 10 | 2 | 10 | 53.2b | 7 | ||

| Zhang et al. (61) | China | Wuhan | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 290 | 1 | 290 | 57b | 155 | 10 | |

| Zhu et al. (62)a | China | Ningbo | Hospital | Case Series | 127 | 0 | 127 | 50.90 (15.26) | |||

| Pre-prints | |||||||||||

| Burn et al. (CUIMC) (18) | USA | Hospital | Prospective Cohort Study | 916 | 65 | 916 | 61.4b | 476 | |||

| Burn et al. (STARR =) (18) | USA | California | Hospital | Prospective Cohort Study | 141 | 19 | 141 | 60b | 80 | ||

| Burn et al. (VA) (18) | USA | Veterans Affair | Hospital | Prospective Cohort Study | 577 | 57 | 577 | 65.6b | 542 | ||

| Carr et al. (19) | UK | Southeast London | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 452 | 65 | 452 | 67 (28) | 248 | ||

| Directorate General of Epidemiology Mexico (21) | Mexico | Mixed | Prospective Cohort Study | 119528 | 3417 | 119528 | 42.62b | ||||

| HIRA (18,27)a | South Korea | Community | Case Control Study | 5172 | 1496 | 5172 | 42 (18–100) | 2289 | |||

| Mallat et al. (37) | UAE | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 34 | 3 | 34 | 37 (31–48) | 25 | 3 | ||

| Paranjpe et al. (39) | USA | New York | Hospital | Case Series | 2199 | 180 | 2199 | 65 (54–76) | 1293 | ||

| Prats-Uribe et al. (42)a | UK | Community | Prospective Cohort Study | 1039 | 118 | 1039 | 68.22b | 113 | |||

| Prieto-Alhambra et al. (43) | Spain | Catalonia | Community | Retrospective Cohort Study | 121263 | 8260 | 121263 | 51.6b | |||

| Rentsch et al. (44) | USA | Veterans Affair | Hospital | Prospective Cohort Study | 585 | 45 | 585 | 66.1 (60.4–71) | 558 | 159 | |

| Sapey et al. (46) | UK | Birmingham | Community | Retrospective Cohort Study | 2217 | 439 | 2217 | 69 (63–81) | 1290 | ||

| Shah et al. (47) | USA | California | Hospital | Prospective Cohort Study | 33 | 4 | 33 | 63 (50–75) | 22 | 0 | |

| SIDIAP (48) | Spain | Catalonia | Mixed | Retrospective Cohort Study | 10771 | 765 | 10771 | 65.5b | 6236 | ||

| Singh et al. (49) | USA | Community | Retrospective Cohort Study | 13710 | 1480 | 13710 | 52.64b | 5980 | |||

| US CDC (Adults) (3) | USA | Mixed | Retrospective Cohort Study | 5952 | 738 | 5952 | 54.6b | ||||

| US CDC(Pediatrics) (3)c | USA | Mixed | Retrospective Cohort Study | 102 | 19 | 102 | 7.12b | ||||

| Wang et al. (53)a | USA | New York | Hospital | Prospective Cohort Study | 3273 | 160 | 3273 | 65.16 (2–69) | |||

| Whitman et al. (55) | USA | San Francisco; Boston | Hospital | Diagnostic Study | 80 | 4 | 80 | 52.7(15.1) | 55 | ||

| Zhang et al. (59)c | China | West China | Hospital | Case Series | 34 | 1 | 34 | 2.75 (0.8–7.85) | 14 | ||

| Zhang et al. (60) | China | Chongqing | Hospital | Retrospective Cohort Study | 43 | 0 | 43 | 49.9b | 22 | ||

CoRR = espondence with authors.

Calculated based on available data.

Pediatrics.

A total of 349 592 tested positive for COVID-19. Four studies (3,14,33,59) only included children (n = 211). The remaining studies consisted of adults or a mixed population (21). Mean age of the participants was 52.07 (SD 16.81 years), 52.5% were males (n = 51 746), 11.75% were current smokers (n = 4 849) and 16.2% were former smokers (n = 8 715). 54% had any comorbidities (n = 33 171) and 21% had diabetes (n = 15 207) and 8.04% had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (n = 48 491).

Thirty-six studies were peer-reviewed publications while another 17 were preprints, 3 were government reports and 1 an open dataset. Two reviewers independently assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale which consists of 3 domains (63). One star is allocated in the domains of selection and outcome or exposure and up to 2 stars are allocated to the comparability domain. A total of 9 stars are allocated across all three domains. An overall score of 1–3 stars is categorized as low quality, 4–6 as medium quality and 7–9 as high quality. Based on this scale, 11 studies were rated as high quality, 44 studies as medium quality and 2 studies as low quality, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Quality of studies assessment.

The prevalence of asthma among those infected with COVID-19 was 7.46% (49 studies, 95% CI 6.25–8.67; test of homogeneity p < 0.001) as shown in Figure S1. In the six studies where asthma was described by severity (n = 3313), non-severe asthma among people with COVID-19 was more common than severe asthma (9.61%, 95% CI = 6.09–13.13 vs. 4.13%, 95% CI = 1.35–6.91), see Figure S2.

The pooled analysis of 6 studies (n = 369 405) showed a Risk Ratio Reduction (RRR) in acquiring COVID-19 of 14% for people with asthma compared to those without asthma (RR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.80–0.94; p < 0.0001; Figure 3). There was moderate heterogeneity (I2= 62.19%) across the studies.

Figure 3.

Risk of acquiring COVID-19 in people with asthma compared to no asthma.

We observed a significant RRR in hospitalization from COVID-19 of 13% for people with asthma compared to no asthma (RR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.77–0.99, p = 0.03), in the 4 studies (n = 121 127) included in this analysis. There was moderate heterogeneity observed (I2= 62.76%) across the studies. See Figure 4(A).

Figure 4.

Risk of severe illness from COVID-19 among those with asthma compared to no asthma.

There was a non-significantly different risk of developing severe illness from COVID-19 requiring admission to ICU for people with asthma compared to those without asthma (RR = 1.19, 95% CI = 0.93–1.53, p = 0.16), in a pooled analysis of 6 studies (n = 4325). Low heterogeneity is observed (I2= 0.10%) across the studies. See Figure 4(B).

In relation to probability of mechanical ventilation, of the 6 studies (n = 47 245) pooled for this analysis, there was a non-significantly different risk of developing severe illness from COVID-19 requiring mechanical ventilation for people with asthma compared to those without asthma (RR = 1.16, 95% 0.83 to 1.63, p = 0.39). Substantial heterogeneity is observed (I2= 88%) across the studies. See Figure 4(C).

We also observed a non-significantly different risk of developing severe illness requiring admission to ICU and/or mechanical ventilation once hospitalized for people with asthma compared to those without asthma among the 12 studies pooled (n = 52 172, RR = 1.13, 95% CI = 0.94–1.37, p = 0.19). Heterogeneity was substantial (I2= 59.53%) across the included studies. See Figure 4(D).

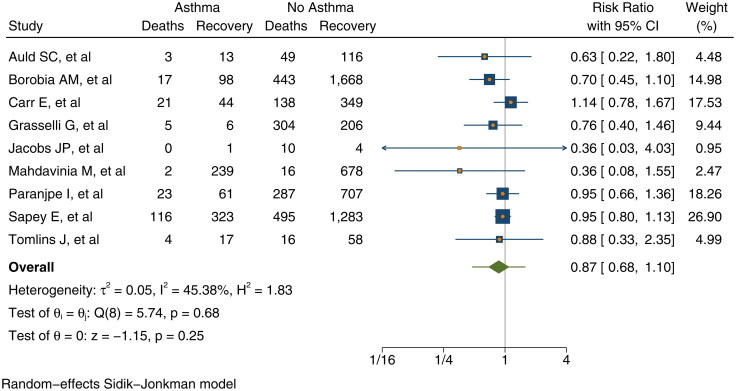

There was a non-significantly different risk of death from COVID-19 for people with asthma compared to those without asthma (RR = 0.87, 95% 0.68–1.10; p = 0.25) in the 9 studies (n = 7 820) pooled for this analysis. Moderate heterogeneity is observed (I2= 45%) across the studies. See Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Risk of death against recovered from COVID-19 among those with asthma compared to no asthma.

The meta-regression by age demonstrates that older age is associated with an increased risk of acquiring COVID-19 in people with asthma (Meta-regression coefficient 0.0064, 95% CI = 0.0003 to 0.012; p = 0.038). The R-squared test showed that about 70% of the variance between studies in risk of acquiring COVID-19 can be explained by age. Hence, low heterogeneity (I2= 35.1%) was observed after including age as a moderator. The meta-regression by age of the other outcomes did not show statistically significant associations.

The subgroup analysis by continent revealed a higher risk of requiring admission to ICU once hospitalized in Asia (RR = 1.21, 95% CI = 0.61–2.43) and America (RR = 1.21, 95% CI = 0.92–1.59) compared to Europe (RR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.38–2.78), however the difference between the groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.96). In contrast, a borderline statistically significant test group difference (p = 0.052) was observed between risk of being ventilated in Europe (RR = 1.66, 95% CI = 0.52–5.25) compared to Asia (RR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.12–1.78) and America (RR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.75–1.20).

The sensitivity analysis including more studies (n = 37) showed a borderline statistically significant lower risk of hospitalization from COVID-19 of 5% for people with asthma compared to no asthma (RR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.93–0.99, p = 0.02). See Figure S4.

Sensitivity analysis (all patients not dead taken as alive) did not demonstrate a significant increase risk of death from COVID-19 in people with asthma compared to no asthma (RR = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.59–1.72), (p = 0.97). The National Committee on COVID-19 Epidemiology Iran study (9) contributed a weight of 10.0% to this result with a very high RR = of 12.70 compared to the rest of the studies. When this study was removed from the analysis, the 3% increase in death changed to a 13% reduction in death in people with asthma compared to no asthma (RR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.72–1.04, p = 0.13; Figure S4). In comparison, the worst-case sensitivity (all patients who have not yet recovered were taken as ‘dead’) analysis also showed 3% increase in the odds of recovery in people with asthma compared to no asthma (RR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.84–1.13, p = 0.72; Figure S4).

Discussion

This systematic review aims to assess the vulnerability of people with asthma during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results revealed a 7.46% prevalence of asthma among those who tested positive for COVID-19. Although these studies come from countries with differing asthma prevalence, overall this pooled prevalence is similar to the prevalence of self-reported asthma symptoms of 8.6% (64). In the studies that reported on the severity of asthma, we found that non-severe asthma among people with COVID-19 was more common than severe asthma (9.6% vs 4.13%) as in most populations (65,66).

We found a 14% (95% CI = 0.80–0.94) lower risk of acquiring COVID-19 in people with asthma, which is an absolute reduction of 50 cases per 1 000 people. This is consistent with the trend observed during the SARS pandemic (67). There are several possible explanations for this risk reduction which include the observation that people with T2-high asthma have down regulated angiotensin-converting-enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptors that may reduce their risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2 (68). Early evidence from the Severe Asthma Research Program-3 has shown that inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) therapy, the main treatment modality in asthmatics is associated with lower ACE-2 (one of the binding sites for SARS-CoV-2) expression (69). This may confer a reduction in vulnerability to COVID-19 and development of less severe disease.

Subsequent to our analysis, two studies were published which we would have included if they had been available prior to our cutoff date. In a study of electronic medical records of patients aged 65 years or younger with severe COVID-19, admitted to hospital in New York City, asthma diagnosis was not associated with worse outcomes, regardless of age, obesity, or other high-risk comorbidities (70). Mahdavinia (36) showed that duration of hospitalization showed a trend to be longer among patients with a history of asthma compared to those without in the 50–64 years age group but this was not associated with a higher rate of death nor with ARDS. These findings are in keeping with the results of our review. Finally, in a review of papers in English published prior to 7 May 2020, compared to population prevalence, asthma prevalence among patients hospitalized for COVID-19 infection was similar and significantly lower than asthma prevalence among patients hospitalized for influenza (71).

Although it was initially considered likely that SARS-CoV-2 infection would increase exacerbation risk for people with asthma, there are several reasons why this may not be the case. Lower interferon levels in people with asthma are also hypothesized to be protective against cytokine storm which occurs in severe COVID-19 patients (72). Behavioral aspects may have also played a role in reducing the vulnerability of asthmatics to COVID-19 (73). Early in the pandemic, the uncertainty on the impact of asthma on COVID-19 and previous experience of viral infections triggering asthma exacerbations caused anxiety among patients and caregivers (74,75). This followed government advice during the peak of the pandemic in countries like the United Kingdom, which classified severe asthmatics as a vulnerable group and advised them to shield for 12 weeks at home (5). A study in USA showed that during the pandemic, there was a 14.5% relative increase in daily controller adherence in asthmatics and COPD patients which supports this posit (76). All these factors may have worked together in reducing the risk of acquiring COVID-19 in people with asthma.

Increasing age is strongly associated with an increased risk of acquiring COVID-19 among asthmatics and explained 70% of the in-between study variance in our analysis. This is an expected finding and in line with other COVID-19 studies showing age as one of the most important predictors for vulnerability to COVID-19 and prognosis (22,77,78).

A statistically significant risk reduction in hospitalization from COVID-19 of 13% (95% CI = 0.77–0.99, p = 0.03) in people with asthma was observed, validated by the results of the sensitivity analysis. This is consistent with the findings of several more recent studies which showed that having asthma is not associated with an increased risk of hospitalization 0.96 (95% CI = 0.77–1.19) (79) and that people with asthma are underrepresented among hospitalized patients with severe pneumonia from COVID-19 (80). In the majority of studies included in our review treatment was not recorded. However, some in vitro studies suggest that inhaled corticosteroids may have a protective effect in which case the use of ICS may be a contributing factor in reducing the risk of acquiring COVID-19 as well as the risk of severe illness warranting hospitalization. Further, the RECOVERY trial showed that dexamethasone lowered the incidence of death in severe COVID-19 patients receiving respiratory support compared to their counterparts (81). As systemic corticosteroids are also given to treat acute exacerbations of asthma, it is possible that this is one mechanism by which people with asthma who are hospitalized with COVID-19 do not have worse outcomes.

Our aggregated-data meta-regression and previous studies have shown that older age and presence of other comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes in people with asthma are strongly associated with the severity of COVID-19 (82) and that asthma is not a major risk factor (83). However, many of the included studies did not report comorbidities, individual patient data and more studies are needed before firm conclusions can be drawn.

In contrast, our pooled analysis showed a 19% (95% CI = 0.93–1.53; p = 0.16) increase in the risk of developing severe illness from COVID-19 requiring admission to ICU once people with asthma are hospitalized. Although not statistically significant in our review, this finding is similar to a recent UK Biobank study which reported a 39% increase risk for severe COVID-19 among those with asthma (adjOR 1.39; 95%CI 1.13–1.71; p = 0.002) (84). Airflow limitation due to bronchospasm and mucus plugging would be expected to compound the hypoxemia characteristic of diffuse alveolar damage in COVID-19 patients with underlying asthma, requiring more intensive respiratory support (85).

Similarly, people with asthma have a 16% (95% CI = 0.83–1.63; p = 0.39) increased risk of requiring mechanical ventilation, albeit not statistically significant with quite a wide confidence interval. Those in Europe have a higher risk of being ventilated compared to Asia and America, which was statistically significant and possibly due to differences in criteria for mechanical ventilation between continents especially early in the pandemic.

Increasing age is not statistically associated with a increased risk of mechanical ventilation in people with asthma. One study reported that asthma prolonged the intubation time in patients <65 years (36) which suggests that asthma has a greater impact on COVID-19 course in younger people. On the other hand, a recent study in Spain (86) among asthmatics reported that those who acquire COVID-19 were older with a greater prevalence of comorbidities compared to those who were COVID-19 negative. Those older and with comorbidities were also reported to be more likely hospitalized. Of note, there was a low rate of hospitalization reported in this study among those with COVID-19 of 0.23%.

There is a no evidence of a difference in the risk of death from COVID-19 for people with asthma (RR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.68–1.10; p = 0.19). A study in New York also reported that asthma was not associated with mortality (87). We note that the mean age of the pooled studies was 52 years. As, previous studies have shown that case fatality rate increases substantially above 50 years of age, our findings might present a conservative estimate of the potential reduction in risk of death (22,77,78).

This review has rigorously adhered to the guidelines of performing systematic reviews. We undertook extensive searches of the databases and additional resources including preprint repositories, agency reports and open datasets. We acknowledge that the findings were partly based on unpublished preprints at the time of analysis, however, we also utilized open routinely collected datasets from national government databases when available and find this to be a strength of this study. While we note that reporting quality does not always relate to study quality, a recent study has reported small absolute differences in quality of reporting of reporting between peer-reviewed and pre-print articles (88). Hence, we expect their inclusion to not substantially impact the pooled findings.

Based on the result of the regression-based Egger’s test (Table S2), there was no evidence of small-study effects. From the eyeball assessment of the contour-enhanced funnel plots we considered that the risk of severe illness requiring mechanical ventilation and the risk of death as showing potential publication bias as they look quite asymmetric (see Figure S3).

A limitation of this review is the synthesis of primarily observational studies, short duration of follow-up, mainly self-reported asthma and variable reporting of outcomes which may introduce bias in the pooled effect. To mitigate this risk, we performed sensitivity analyses to explore the robustness of the findings under different assumptions and meta-regression to examine the impact of age on the study effect size. Another limitation is the varying case definition and quality of the studies. However, in the context of a pandemic situation, achieving uniformity and high-quality diagnostic data is challenging. This has resulted in some comparisons being based on only four to five studies and informed by one to two large studies which may limit generalizability.

Asthma and COPD are also often misdiagnosed in practice (89,90), we have mitigated this risk through including studies which only explicitly mention asthma, corresponding with authors for clarification when ambiguous and a comprehensive search of literature including studies from various centers. Even so, error may have occurred in the original diagnosis or in the “label” the patient chose to convey. Noting that patients with COPD would likely have more severe preexisting lung damage and be at greater risk of poor outcomes from COVID-19, this misclassification may confound the results to show greater severity when infected with COVID-19 among asthmatics (91).

Although we had hoped to include treatment with inhaled corticosteroid or systemic corticosteroid, and subgroups of pediatrics and the elderly, as well as the different asthma phenotypes in the analysis, this was precluded by the limited data available on these clinical variables.

Finally, a proportion of patients with COVID-19 experience prolonged effects following the acute illness, now termed “Long COVID” (92). The most common symptoms of fatigue, breathlessness and cough may be more likely or prominent in people with background airways disease. Although beyond the scope of this analysis it will be crucial to examine these risks in further studies of people with asthma and COVID-19.

In summary, the findings from this study suggest that the prevalence of people with asthma among COVID-19 patients is similar to the global prevalence of asthma. The overall findings based on available evidence suggest that people with asthma are not at increased risk for acquiring COVID-19 compared to those without asthma and have similar clinical outcomes. Further high-quality primary studies and data sharing on asthma and COVID-19 globally is needed to improve our understanding of how SARS-CoV-2 impacts those with asthma.

Funding Statement

This study is funded by Asthma Australia. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest. AS is in receipt of a UNSW Scientia PhD scholarship.

References

- 1.Maria DVK, Sadoof A, Abdullah A, Ranawaka APMP, Malik P, Hassan EEB, Abdulaziz AB.. Transmissibility of MERS-CoV infection in closed setting, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis J. 2019;25(10):1802. doi: 10.3201/eid2510.190130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oliver BG, Robinson P, Peters M, Black J.. Viral infections and asthma: an inflammatory interface? Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1666–1681. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00047714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US CDC . COVID-NET Preliminary Data 30 May 2020. Available from: https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/COVIDNet/COVID19_5.html [last accessed 6 June 2020].

- 4.Li X, Xu S, Yu M, Wang K, Tao Y, Zhou Y, Shi J, Zhou M, Wu B, Yang Z, et al. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(1):110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NICE UK . COVID-19 rapid guideline: Severe asthma; 2020. [PubMed]

- 6.Centre of Excellence in Severe Asthma . Clinical Recommendations for COVID-19 in Severe Asthma 2020. Available from: https://www.severeasthma.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/COVID-19-CRE-Recommendations-Version-1.1.pdf.

- 7.Sayeed A, Kundu S, Al Banna MH, Christopher E, Hasan MT, Begum MR, Chowdhury S, Khan MSI.. Mental health outcomes of adults with comorbidity and chronic diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic: a matched case-control study. Psychiatr Danub. 2020;32(3–4):491–498. doi: 10.24869/psyd.2020.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Philip KEJ, Lonergan B, Cumella A, Farrington-Douglas J, Laffan M, Hopkinson NS.. COVID-19 related concerns of people with long-term respiratory conditions: a qualitative study. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20(1):319. doi: 10.1186/s12890-020-01363-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Committee on COVID-19 Epidemiology, Ministry of Health and Medical Education, IR Iran . Daily Situation Report on Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Iran. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8(1):e26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.IntHout J, Ioannidis JPA, Rovers MM, Goeman JJ.. Plea for routinely presenting prediction intervals in meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e010247. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, Lokhandwala S, Riedo FX, Chong M, Lee M.. Characteristics and Outcomes of 21 Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1612–1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Argenziano MG, Bruce SL, Slater CL, Tiao JR, Baldwin MR, Barr RG, Chang BP, Chau KH, Choi JJ, Gavin N, et al. Characterization and clinical course of 1000 Patients with COVID-19 in New York: retrospective case series. medRxiv. 2020;369:m1996. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.20.20072116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Auld SC, Caridi-Scheible M, Blum JM, Robichaux C, Kraft C, Jacob JT, Jabaley CS, Carpenter D, Kaplow R, Hernandez-Romieu AC, et al. Emory COVID-19 quality and clinical research collaborative. ICU and ventilator mortality among critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(9):e799–e804. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belhadjer Z, Meot M, Bajolle F, Khraiche D, Legendre A, Abakka S, Auriau J, Grimaud M, Oualha M, Beghetti M, et al. Acute heart failure in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) in the context of global SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Circulation. 2020;142(5):429–436. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, Kim R, Jerome KR, Nalla AK, Greninger AL, Pipavath S, Wurfel MM, Evans L, et al. Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the seattle region - case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2012–2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borba MGS, Val FFA, Vanderson Souza Sampaio P, Alexandre MAA, Melo GC, Brito M, Mourão MPG, Brito-Sousa JD, Baía-da-Silva D, Guerra MVF, Team C, et al. Effect of High vs low doses of chloroquine diphosphate as adjunctive therapy for patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4):e208857. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borobia AM, Carcas AJ, Arnalich F, Alvarez-Sala R, Monserrat-Villatoro J, Quintana M, Figueira JC, Torres Santos-Olmo RM, Garcia-Rodriguez J, Martin-Vega A, Buno A, on behalf of the COVID@HULP Working Group, et al. A cohort of patients with COVID-19 in a major teaching hospital in Europe. JCM. 2020;9(6):1733. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burn E, You SC, Sena AG, Kostka K, Abedtash H, Abrahão MTF, Alberga A, Alghoul H, Alser O, Alshammari TM, et al. An international characterisation of patients hospitalised with COVID-19 and a comparison with those previously hospitalised with influenza. medRxiv. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carr E, Bendayan R, Bean D, O’Gallagher K, Pickles A, Stahl D, Zakeri R, Searle T, Shek A, Kraljevic Z, et al. Supplementing the National Early Warning Score (NEWS2) for anticipating early deterioration among patients with COVID-19 infection. medRxiv. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, Curtis HJ, Mehrkar A, Evans D, Inglesby P, et al. OpenSAFELY: factors associated with COVID-19 death in 17 million patients. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Directorate General of Epidemiology Mexico . Open COVID-19 Dataset 7 June 2020. Available from: https://www.gob.mx/salud/documentos/datos-abiertos-bases-historicas-direccion-general-de-epidemiologia [last accessed 7 June2020].

- 22.Docherty A, Harrison E, Green C, Hardwick H, Pius R, Norman L, Holden K, Read J, Dondelinger F, Carson G, Merson L, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO clinical characterisation protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fadel R, Morrison AR, Vahia A, Smith ZR, Chaudhry Z, Bhargava P, Miller J, Kenney RM, Alangaden G, Ramesh MS, Henry Ford C-M.. Early short course corticosteroids in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, Schenck EJ, Chen R, Jabri A, Satlin MJ, Campion TR, Jr., Nahid M, Ringel JB, et al. Clinical characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):2372–2374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, Castelli A, Cereda D, Coluccello A, Foti G, Fumagalli R, for the COVID-19 Lombardy ICU Network, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs JP, Stammers AH, St Louis J, Hayanga JWA, Firstenberg MS, Mongero LB, Tesdahl EA, Rajagopal K, Cheema FH, Coley T, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the treatment of severe pulmonary and cardiac compromise in coronavirus disease 2019: experience with 32 patients. Asaio J. 2020;66(7):722–730. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ji W, Huh K, Kang M, Hong J, Bae GH, Lee R, Na Y, Choi H, Gong S, Choi Y-H, et al. Effect of underlying comorbidities on the infection and severity of COVID-19 in South Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(25):e237. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.08.20095174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ki M, Task Force for 2019-nCoV. Epidemiologic characteristics of early cases with 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) disease in Korea. Epidemiol Health. 2020;42:e2020007. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2020007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim SE, Jeong HS, Yu Y, Shin SU, Kim S, Oh TH, Kim UJ, Kang SJ, Jang HC, Jung SI, et al. Viral kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 in asymptomatic carriers and presymptomatic patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:441–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, Place S, Van Laethem Y, Cabaraux P, Mat Q, Huet K, Plzak J, Horoi M, Hans S, COVID‐19 Task Force of YO‐IFOS, et al. Clinical and Epidemiological Characteristics of 1,420 European Patients with mild-to-moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019. J Intern Med. 2020;288(3):335–344. doi: 10.1111/joim.13089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Xu S, Yu M, Wang K, Tao Y, Zhou Y, Shi J, Zhou M, Wu B, Yang Z, et al. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(1):110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lian J-s, Cai H, Hao S-r, Jin X, Zhang X-l, Zheng L, Jia H-y, Hu J-h, Zhang S-y, Yu G-d, et al. Comparison of epidemiological and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients with and without Wuhan exposure history in Zhejiang Province, China. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2020;21(5):369–377. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B2000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Licari A, Votto M, Brambilla I, Castagnoli R, Piccotti E, Olcese R, Tosca MA, Ciprandi G, Marseglia GL.. Allergy and asthma in children and adolescents during the COVID outbreak: What we know and how we could prevent allergy and asthma flares. Allergy. 2020;75(9):2402–2405. doi: 10.1111/all.14369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ling L, So C, Shum HP, Chan PKS, Lai CKC, Kandamby DH, Ho E, So D, Yan WW, Lui G, et al. Critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Hong Kong: a multicentre retrospective observational cohort study. Crit Care Resusc. 2020;22(2):119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lokken EM, Walker CL, Delaney S, Kachikis A, Kretzer NM, Erickson A, Resnick R, Vanderhoeven J, Hwang JK, Barnhart N, et al. K. Clinical characteristics of 46 pregnant women with a SARS-CoV-2 infection in Washington State. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(6):911.e1–911.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.031.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahdavinia M, Foster KJ, Jauregui E, Moore D, Adnan D, Andy-Nweye AB, Khan S, Bishehsari F.. Asthma prolongs intubation in COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(7):2388–2391. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mallat J, Hamed F, Balkis M, Mohamed MA, Mooty M, Malik A, Nusair A, Maria-Fernanda B.. Hydroxychloroquine is associated with slower viral clearance in clinical COVID-19 patients with mild to moderate disease: A retrospective study. medRxiv. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.27.20082180.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merza MA, Haleem Al Mezori AA, Mohammed HM, Abdulah DM.. COVID-19 outbreak in Iraqi Kurdistan: The first report characterizing epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, and radiological findings of the disease. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(4):547–554. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paranjpe I, Russak A, De Freitas JK, Lala A, Miotto R, Vaid A, Johnson KW, Danieletto M, Golden E, Meyer D, et al. Clinical characteristics of hospitalized covid-19 patients in New York City. medRxiv. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.19.20062117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng S, Huang L, Zhao B, Zhou S, Braithwaite I, Zhang N, Fu X.. Clinical course of coronavirus disease 2019 in 11 patients after thoracic surgery and challenges in diagnosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;160(2):585–592.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pongpirul WA, Mott JA, Woodring JV, Uyeki TM, MacArthur JR, Vachiraphan A, Suwanvattana P, Uttayamakul S, Chunsuttiwat S, Chotpitayasunondh T, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease, Thailand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7):1580–1585. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prats-Uribe A, Paredes R, Prieto-Alhambra D.. Ethnicity, comorbidity, socioeconomic status, and their associations with COVID-19 infection in England: a cohort analysis of UK Biobank data. medRxiv. 2020; doi: 10.1101/2020.05.06.20092676.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prieto-Alhambra D, Balló E, Coma E, Mora N, Aragón M, Prats-Uribe A, Fina F, Benítez M, Guiriguet C, Fàbregas M, et al. Hospitalization and 30-day fatality in 121,263 COVID-19 outpatient cases. medRxiv. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.04.20090050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rentsch CT, Kidwai-Khan F, Tate JP, Park LS, King JT, Skanderson M Jr., Hauser RG, Schultze A, Jarvis CI, Holodniy M, et al. Covid-19 testing, hospital admission, and intensive care among 2,026,227 United States veterans aged 54–75 years. medRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, The Northwell C-RC, Barnaby DP, Becker LB, Chelico JD, and the Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sapey E, Gallier S, Mainey C, Nightingale P, McNulty D, Crothers H, Evison F, Reeves K, Pagano D, Denniston AK, et al. Ethnicity and risk of death in patients hospitalised for COVID-19 infection: an observational cohort study in an urban catchment area. medRxiv. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.05.20092296.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shah S, Barish PN, Prasad PA, Kistler A, Neff N, Kamm J, Li LM, Chiu CY, Babik JM, Fang MC, Kangelaris KN, et al. Clinical features, diagnostics, and outcomes of patients presenting with acute respiratory illness: a comparison of patients with and without COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020; doi: 10.1101/2020.05.02.20082461.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.SIDIAP . OHDSI Dataset 2020. Available from: http://evidence.ohdsi.org:3838/Covid19CharacterizationHospitalization/#shiny-tab-cohortCounts [last accessed 6 June 2020].

- 49.Singh S, Chowdhry M, Chatterjee A.. Gender-based disparities in COVID-19: clinical characteristics and propensity-matched analysis of outcomes. medRxiv. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.24.20079046.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun Y, Dong Y, Wang L, Xie H, Li B, Chang C, Wang FS.. Characteristics and prognostic factors of disease severity in patients with COVID-19: the Beijing experience. J Autoimmun. 2020;112:102473. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tomlins J, Hamilton F, Gunning S, Sheehy C, Moran E, MacGowan A.. Clinical features of 95 sequential hospitalised patients with novel coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19), the first UK cohort. J Infect. 2020;81(2):e59–e61. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Y, Liu Y, Liu L, Wang X, Luo N, Li L.. Clinical outcomes in 55 patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 who were asymptomatic at hospital admission in Shenzhen, China. J Infect Dis. 2020;221(11):1770–1774. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Z, Zheutlin AB, Kao Y-H, Ayers KL, Gross SJ, Kovatch P, Nirenberg S, Charney AW, Nadkarni GN, O’Reilly PF, et al. Analysis of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in the Mount Sinai Health System using electronic medical records (EMR) reveals important prognostic factors for improved clinical outcomes. medRxiv. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.28.20075788.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wei XS, Wang XR, Zhang JC, Yang WB, Ma WL, Yang BH, Jiang NC, Gao ZC, Shi HZ, Zhou Q.. A cluster of health care workers with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2021;54(1):54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whitman JD, Hiatt J, Mowery CT, Shy BR, Yu R, Yamamoto TN, Rathore U, Goldgof GM, Whitty C, Woo JM, et al. Test performance evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 serological assays. medRxiv. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.25.20074856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wichmann D, Sperhake JP, Lutgehetmann M, Steurer S, Edler C, Heinemann A, Heinrich F, Mushumba H, Kniep I, Schroder AS, et al. Autopsy findings and venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(4):268–277. doi: 10.7326/M20-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu J, Liu J, Zhao X, Liu C, Wang W, Wang D, Xu W, Zhang C, Yu J, Jiang B, et al. Clinical characteristics of imported cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Jiangsu province: a multicenter descriptive study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):706–712. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yasukawa K, Minami T.. Point-of-care lung ultrasound findings in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102(6):1198–1202. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang C, Gu J, Chen Q, Deng N, Li J, Huang L, Zhou X.. Clinical characteristics of 34 children with coronavirus disease-2019 in the west of China: a multiple-center case series. medRxiv. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.12.20034686.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang H, Wang X, Fu Z, Luo M, Zhang Z, Zhang K, He Y, Wan D, Zhang L, Wang J, et al. Potential factors for prediction of disease severity of COVID-19 patients. medRxiv. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.20.20039818.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang JJ, Cao YY, Dong X, Wang BC, Liao MY, Lin J, Yan YQ, Akdis CA, Gao YD.. Distinct characteristics of COVID-19 patients with initial rRT-PCR-positive and rRT-PCR-negative results for SARS-CoV-2. Allergy. 2020;75(7):1809–1812.14316. doi: 10.1111/all. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu Z, Cai T, Fan L, Lou K, Hua X, Huang Z, Gao G.. Clinical value of immune-inflammatory parameters to assess the severity of coronavirus disease 2019. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses 2020. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp [last accessed 9 June 2020].

- 64.Global Asthma Network. The Global Asthma Report; 2018.

- 65.Varsano S, Segev D, Shitrit D.. Severe and non-severe asthma in the community: a large electronic database analysis. Respir Med. 2017;123:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dharmage SC, Perret JL, Custovic A.. Epidemiology of asthma in children and adults. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:246. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Halpin DMG, Faner R, Sibila O, Badia JR, Agusti A.. Do chronic respiratory diseases or their treatment affect the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):436–438. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30167-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jackson DJ, Busse WW, Bacharier LB, Kattan M, O’Connor GT, Wood RA, Visness CM, Durham SR, Larson D, Esnault S, et al. Association of respiratory allergy, asthma, and expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Peters MC, Sajuthi S, Deford P, Christenson S, Rios CL, Montgomery MT, Woodruff PG, Mauger DT, Erzurum SC, Johansson MW, et al. COVID-19 related genes in sputum cells in asthma: relationship to demographic features and corticosteroids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(1):83–90. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0821OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lovinsky-Desir S, Deshpande DR, De A, Murray L, Stingone JA, Chan A, Patel N, Rai N, DiMango E, Milner J, et al. Asthma among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and related outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.07.026.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Broadhurst R, Peterson R, Wisnivesky JP, Federman A, Zimmer SM, Sharma S, Wechsler M, Holguin F.. Asthma in COVID-19 hospitalizations: an overestimated risk factor? Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(12):1645–1648. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202006-613RL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carli G, Cecchi L, Stebbing J, Parronchi P, Farsi A.. Is asthma protective against COVID-19? Allergy. 2020. doi: 10.1111/all.14426.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Butler MW, O’Reilly A, Dunican EM, Mallon P, Feeney ER, Keane MP, McCarthy C.. Prevalence of comorbid asthma in COVID-19 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Akenroye AT, Wood R, Keet C.. Asthma, biologics, corticosteroids, and coronavirus disease 2019. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Krivec U, Kofol Seliger A, Tursic J.. COVID-19 lockdown dropped the rate of paediatric asthma admissions. Arch Dis Child. 2020;105(8):809–810. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaye L, Theye B, Smeenk I, Gondalia R, Barrett MA, Stempel DA.. Changes in medication adherence among patients with asthma and COPD during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu Z, McGoogan JM.. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2648%J JAMA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S.. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chhiba KD, Patel GB, Vu THT, Chen MM, Guo A, Kudlaty E, Mai Q, Yeh C, Muhammad LN, Harris KE, et al. Prevalence and characterization of asthma in hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(2):307–314.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Beurnier A, Jutant E-M, Jevnikar M, Boucly A, Pichon J, Preda M, Frank M, Laurent J, Richard C, Monnet X, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of asthmatic patients with COVID-19 pneumonia who require hospitalisation. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(5):2001875. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01875-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.The Recovery Collaborative Group . Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19—preliminary report. New Eng J Med. 2020;384(8):693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, Pu K, Chen Z, Guo Q, Ji R, Wang H, Wang Y, Zhou Y.. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Haberman R, Axelrad J, Chen A, Castillo R, Yan D, Izmirly P, Neimann A, Adhikari S, Hudesman D, Scher JU.. Covid-19 in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases—case series from New York. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(1):85–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhu Z, Hasegawa K, Ma B, Fujiogi M, Camargo CA, Jr., Liang L.. Association of asthma and its genetic predisposition with the risk of severe COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(2):327–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Konopka KE, Wilson A, Myers JL.. Postmortem lung findings in an asthmatic patient with coronavirus disease 2019. Chest. 2020;158(3):e99–e101. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Izquierdo JL, Almonacid C, Gonzalez Y, Del Rio-Bermudez C, Ancochea J, Cardenas R, Lumbreras S, Soriano JB.. The impact of COVID-19 on patients with asthma. Eur Respir J. 2020. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03142-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lieberman-Cribbin W, Rapp J, Alpert N, Tuminello S, Taioli E.. The impact of asthma on mortality in patients with COVID-19. Chest. 2020;158(6):2290–2291. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Carneiro CFD, Queiroz VGS, Moulin TC, Carvalho CAM, Haas CB, Rayee D, Henshall DE, De-Souza EA, Amorim FE, Boos FZ, et al. Comparing quality of reporting between preprints and peer-reviewed articles in the biomedical literature. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2020;5(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s41073-020-00101-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tinkelman DG, Price DB, Nordyke RJ, Halbert RJ.. Misdiagnosis of COPD and asthma in primary care patients 40 years of age and over. J Asthma. 2006;43(1):75–80. doi: 10.1080/02770900500448738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jenkins C, FitzGerald JM, Martinez FJ, Postma DS, Rennard S, van der Molen T, Gardev A, Genofre E, Calverley P.. Diagnosis and management of asthma, COPD and asthma-COPD overlap among primary care physicians and respiratory/allergy specialists: A global survey. Clin Respir J. 2019;13(6):355–367. doi: 10.1111/crj.13016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Leung JM, Niikura M, Yang CWT, Sin DD.. COVID-19 and COPD. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(2):2002108. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02108-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mandal S, Barnett J, Brill SE, Brown JS, Denneny EK, Hare SS, Heightman M, Hillman TE, Jacob J, Jarvis HC, Group ARCS, et al. ‘Long-COVID’: a cross-sectional study of persisting symptoms, biomarker and imaging abnormalities following hospitalisation for COVID-19. Thorax. 2020;76:396–398. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]