Abstract

Vocal fold scar, characterized by alterations in the lamina propria extracellular matrix, disrupts normal voice quality and function. Due to a lack of satisfactory clinical treatments, there is a need for tissue engineering strategies to restore voice. Candidate biomaterials for vocal fold tissue engineering must match the unique biomechanical and viscoelastic properties of native tissue without provoking inflammation. We sought to introduce elastomeric properties to hyaluronic acid (HA)-based biomaterials by incorporating resilin-like polypeptide (RLP) into hybrid hydrogels. Physically crosslinked RLP/HA and chemically crosslinked RLP-acrylamide/thiolated HA (RLP-AM/HA-SH) hydrogels were fabricated using cytocompatible chemistries. Mechanical properties of hydrogels were assessed in vitro using oscillatory rheology. Hybrid hydrogels were injected into rabbit vocal folds and tissues were assessed using rheology and histology. A small number of animals underwent acute vocal fold injury followed by injection of RLP-AM/HA-SH hydrogel alone or as a carrier for human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs). Rheological testing confirmed that mechanical properties of materials in vitro resembled native vocal fold tissue and that viscoelasticity of vocal fold mucosa was preserved days 5 and 21 after injection. Histological analysis revealed that hybrid hydrogels provoked only mild inflammation in vocal fold lamina propria with demonstrated safety in the airway for up to 3 weeks, confirming acute biocompatibility of crosslinking chemistries. After acute injury, RLP-AM/HA-SH gel with and without BM-MSCs did not result in adverse effects or increased inflammation. Collectively, results indicate that RLP and HA-based hybrid hydrogels are highly promising for engineering the vocal fold lamina propria.

Keywords: Resilin, Injectable hydrogels, Viscoelastic properties, Biocompatibility, Vocal folds

Lay Summary

To date, there are no satisfactory treatments for vocal fold scar, which has significant negative impact on communication and quality of life. Tissue engineering holds promise for restoring stiff connective tissue in scarred vocal folds to normal pliability and flexibility. Here, we synthesized and characterized hybrid hydrogels that combine hyaluronic acid (HA), a component of native vocal fold tissue, with resilin-like polypeptide (RLP), a highly elastic and resilient biomaterial. Viscoelasticity and biocompatibility were assessed after injection in rabbit vocal folds. Hybrid hydrogels mimicked mechanical properties of normal vocal folds in vitro and in vivo with minimal inflammation in the airway. RLP/HA hybrid hydrogels thus represent a potential biomaterial to restore normal vocal fold vibration and improve voice quality and function.

Introduction

Vocal folds are paired, layered tissues within the larynx that contact each other during vibration to produce voice. Each vocal fold comprises stratified squamous epithelium, lamina propria, and striated muscle [1–3].Vocal fold lamina propria is rich in extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, proteoglycans, and glycosaminoglycans including collagen, elastin, and hyaluronic acid (HA) that are found in varying concentrations from superficial to deep layers and define the biomechanical properties of the lamina propria [1, 4]. Vocal fold scar is the most frequent cause of persistent dysphonia after vocal fold surgery [5]. Other etiologies for scar include cancer, trauma, chemical injury, and radiation [6]. Scarred vocal fold lamina propria is characterized by alterations in ECM proteins including decreased and disorganized elastic fibers, resulting in increased stiffness and viscosity [7–10]. In patients, reduced lamina propria pliability causes impaired vocal quality and function that could include roughness, breathiness, strain, fatigue, and loss of vocal control [6, 7]. Vocal fold scar represents a persistent problem in laryngology. To date, there are no medical or surgical strategies that can restore native lamina propria elasticity, and behavioral treatment such as voice therapy can provide symptomatic management but does not address underlying etiology [6, 10, 11]. Therefore, there is a need for tissue engineering strategies to restore function to this specialized tissue [12–15].

Vocal fold tissue has unique mechanical properties that serve important functions in voice production, such as vibration at frequencies of 100–1000 Hz and reversible recovery after transient stretch to high strain [3, 4, 16, 17]. Materials for vocal fold treatment therefore not only should have minimum foreign body and inflammatory reactions but also should match the biomechanical and viscoelastic properties of the vocal fold tissue. Vocal fold injection of biomaterials as a therapeutic option can minimize the degree of mucosal invasion and potential trauma to patients compared to surgical implantation and scar lysis procedures [18–20]. Current development of materials for injection into vocal fold tissue has focused on synthetic polymers or biomaterials in the form of solutions, microgels, and hydrogels. Synthetic polymer materials, such as poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)/Pluronic F127 [21], polyether-polyurethane (PEU) matrices [22], and PEG-based materials [23] have been used mainly as minimally inflammatory filler materials to restore vocal fold tissue properties; however, a lack of biological cues to guide cells and tissue regeneration has limited the ability of these materials to help regenerate vocal fold tissue. Native ECM-based biomaterials including HA and collagen have also been employed in vocal fold injection; the HA-based materials are likely the most promising materials in the field [24]. HA is a linear non-sulfated and negatively charged glycosaminoglycan, which contributes to the viscoelastic properties of vocal fold tissue [18, 25] and its chemical functionality permits modification with various chemical groups that have been employed for the crosslinking of HA-based hydrogels [19]. Hylan-B, an HA-based biomaterial [26], has shown improvements in glottal closure and phonation quality in clinical trials [24]. The possibility of introducing elastomeric properties to HA-based biomaterials would thus offer exciting opportunities to further improve the mechanical match of the biomaterial, maintain mechanical integrity during vibration under high frequencies, and exhibit dynamic mechanical response for vocal fold tissue engineering.

Of the elastomeric biomaterial options, the unique insect structural protein resilin exhibits rubber-like elasticity featuring low storage modulus, reversible extensibility with superior resilience, efficient energy storage and release [27–29], and life-long fatigue resistance which survives up to 400 million repeated contraction and extension cycles at high frequencies ranging from 200 to 4000 Hz [30–32]. Biosynthetic methods for producing resilin-like polypeptides (RLPs) offer advantages in engineering new elastomeric and highly mechanically active biomaterials that can be tailored for vocal fold tissue repair [15, 33–36]. Our group demonstrated that RLPs can be crosslinked to form hydrogels with tunable elastic shear and Young’s moduli via multiple different chemical crosslinking methods [37–39]. The mechanical properties of the RLP hydrogels are comparable to vocal fold tissues at elevated frequencies (1000–2000 Pa) [37, 40, 41], with excellent extensibility (up to 300%) and superior resilience (> 95%), and the ability to efficiently transmit dynamic mechanical forces [37, 38, 41, 42]. In addition, RLPs have been designed to include bioactive sequences for modulating biological functions, cellular interactions, and growth factor sequestration and release [38, 43–45]. Initial subcutaneous implantation of RLP hydrogels [43] and injection of RLP into subcutaneous mouse dorsum resulted in minimal chronic inflammation [46]. Our initial studies highlighted the fact that the phosphine-based crosslinker prompted both acute and chronic inflammatory responses, which has prompted the development of a different suite of crosslinking reactions for injection in vivo.

Given the above, the current manuscript describes RLP/HA-based hydrogels that were fabricated with cytocompatible chemistries to enhance biocompatibility of materials in in vivo vocal fold injections. We combine the advantage of RLP and HA materials to design physically crosslinked RLP/HA and chemically crosslinked RLP-AM/HA-SH hybrid hydrogels with and without human BM-MSCs, and evaluate the biocompatibility and feasibility of vocal fold injection of those hydrogels in an in vivo rabbit model. Oscillatory rheology was used to confirm the mechanical properties of the materials prior to injection, as well as to characterize the mechanical properties of the vocal fold tissue after injection. Histological analyses were used to assess inflammatory response and to evaluate the biocompatibility of the materials in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was purchased from Mediatect (Manassas, VA). Deuterium oxide and NMR solvents were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Tewksbury, MA). Sodium hyaluronan (520 kDa) was donated by Sanofi Genzyme (Cambridge, MA). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA) and were used as received unless otherwise noted.

RLP Synthesis and Characterization

RLP protein expression and purification via Ni-NTA affinity chromatography was conducted as previously reported by our laboratories [37, 38, 42, 47], with protein yields after purification of approximately 30–50 mg per liter of cell culture. The RLP proteins were further functionalized with acrylamide groups via modification of regularly positioned lysine residues on the polypeptide chain as previously reported [48]. The functionality of the RLP-AM was characterized via 1H NMR spectrometry. Purified RLP-AM (~ 2 mg) was dissolved in (600 μl) D2O (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Tewksbury, MA) and analyzed using an AVIII 600 MHz NMR spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA). RLP and RLP-AM were further purified via preparative-scale reverse-phase HPLC on a Waters Symmetry C18 column under a linear gradient from 95:5 to 5:95 of water/acetonitrile (containing 0.1% of trifluoroacetic acid) at 5 mL/min over 65 min. Collected elution fractions containing RLP were dissolved in water and lyophilized three times; the final RLP (or RLP-AM) was dissolved in deionized water and sterile-filtered before use in injection experiments in vivo. All materials/solutions employed in the in vivo studies were tested for endotoxin content with ToxinSensor Chromogenic LAL Endotoxin Assay Kit (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ); the levels of endotoxin detected for the RLP was 0.01 EU/ml (0.0002 EU/mg) and for the RLP-AM was 0.06 EU/ml (0.0011 EU/mg), both of which are well below the recommended limit for use in animal studies (5 EU/kg).

HA Synthesis and Characterization

HA-SH was synthesized according to a previously reported method [49, 50]. Briefly, HA (500 kDa) was dissolved in deionized water at pH 4.75 and EDC coupling was performed using 3,3′-dithiobispropanoic dihydrazide. DTT was used for disulfide reduction, and the product was purified with 48 h of dialysis against pH 3.5 and 0.1 M NaCl followed by 24 h of dialysis against pH 3.5 deionized water, with 3 dialysis changes per day against 8 l of solution at ambient temperature. After lyophilization, 1H-NMR was used to characterize the degree of substitution, via integration of the acetamido peak of the HA (δ = 1.92 ppm) and comparison to the DTPH side chain methylenes (δ = 2.61 and 2.76 ppm), which indicated 26% thiol modification. HA and HA-SH were sterile-filtered and lyophilized prior using for injection experiments in vivo. HA and HASH were tested for endotoxin content with the ToxinSensor Chromogenic LAL Endotoxin Assay Kit (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ); endotoxin concentration were 1.20 EU/ml (0.067 EU/mg) and 0.56 EU/ml (0.031 EU/mg), respectively, which are both below the recommended limit (5 EU/kg).

Hydrogel Formation

RLP/HA-based materials are employed in these studies to capture both the high-frequency robustness of the RLP and anti-inflammatory properties of HA. Three compositions of materials for in vivo injection into rabbit vocal fold included a physical hydrogel (RLP/HA gel), a chemically crosslinked hydrogel (RLP-AM/HA-SH gel) and an RLP solution to evaluate the biocompatibility of the RLP-based materials in vivo. Schematics of the physically crosslinked RLP/HA gel and the chemically crosslinked RLP-AM/HA-SH gel are shown in Fig. 1. The physical RLP/HA gel was formed via electrostatic interactions between the positively charged lysine residues of the RLP and the negatively charged HA backbone. The chemically crosslinked RLP-AM/HA-SH gel was crosslinked via Michael-type addition chemistry, which is a highly efficient reaction with no by-products, which has been employed widely for in situ reaction in biological systems [51]. All solutions were clear, suggesting the solubility of the macromolecules, and both types of hydrogels yielded transparent, homogeneous networks.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of hydrogel formation. Physically crosslinked RLP/HA gel and chemically crosslinked RLP-AM/HA-SH gel crosslinking reactions

All stock solutions were chilled on ice before mixing in order to slow the reaction speed and prevent crosslinking during handling. For experiments testing the simple injection of RLP-based hydrogels and solutions to evaluate inflammatory responses and rheology of vocal fold tissue, the physically crosslinked RLP/HA hydrogel (RLP/HA gel), RLP and HA were dissolved into PBS separately at concentrations of 20 wt% (w/v) and 2.5 wt% (w/v), respectively; a small volume (24 μl) of 2 M NaOH was added per ml of the RLP solution to adjust the pH to 8. The RLP was then mixed with 714 μl of HA stock solutions to obtain hydrogels at a final concentration of 7.5 wt% (5.7 wt% RLP and 1.8 wt% HA). For chemically crosslinked RLP-AM/HA-SH hydrogels (RLP-AM/HA-SH gel), the RLP-AM and HA-SH were also dissolved into PBS separately at concentrations of 20 wt% (w/v) and 2.5 wt% (w/v). Again, a small volume (28.4 μl in this case) of 2 M NaOH was added to 286 μl of RLP-AM. The RLP-AM was then mixed with 714 μl of HA-SH stock solutions to yield 7.5 wt% hydrogels (5.7 wt% RLP and 1.8 wt% HA, SH/AM ratio 1.10). The solutions were injected immediately after mixing to prevent gelation in the syringe. For the RLP solution, the RLP was dissolved into PBS at 5.7 wt% (w/v) and the pH of the solution was adjusted to pH 8 by addition of 24 μl of 2 M NaOH per ml.

For use in the acute injury experiments in vivo, the RLP-AM and HA-SH were dissolved into PBS separately at concentrations of 23.5 wt% (w/v) and 3 wt% (w/v), respectively. A volume of 30 μl of 2 M NaOH was added to 291 μl of RLP-AM to adjust the pH of the solution to 8, and the RLP-AM was then mixed with 729 μl of HA-SH stock solutions and 7 μl of 2 M NaOH to adjust the final pH of the RLP-AM/HA-SH solution to 8. Finally, 180 μl of PBS or human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) were added to obtain hydrogels at a final concentration of 7.5 wt% (5.7 wt% RLP-AM and 1.8 wt% HA-SH), identical to concentrations used for injections without injury. One hundred microliters (7.5 mg solids for RLP/HA and RLP-AM/HA-SH hydrogels (0.121 EU and 0.062 EU, respectively); 5.7 mg for RLP solution (0.001 EU)) of hydrogel precursor solutions were injected in vivo immediately after preparation to prevent gelation in the syringe.

Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Human BM-MSCs used for in vitro viability experiments were obtained from Lonza, Walkersville, MD. Cells were initially isolated from adult bone marrow of bilateral iliac crests of normal, non-diabetic volunteers and cryopreserved after passage 2. Passage 9 cells were encapsulated in RLP-AM/HA-SH hydrogels at a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL.

In vivo experiments were completed using BM-MSCs with demonstrated success in rabbit vocal fold scar [52]. Human BM-MSCs were obtained from Waisman Biomanufacturing, Madison, WI. As previously described [52, 53], cells were derived from the iliac crest of a healthy 22-year-old female and expanded and tested using procedures that met Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMPs) for human clinical trials. Cells were suspended in cold freezing medium containing PlasmaLyte, 10% rabbit serum albumin, and 2.5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 2 × 107 cells/mL and cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen. Passage 6 cells were used in this study. Cells were thawed just before injection, when they were gently mixed with RLP-AM/HA-SH gel via pipetting at a final concentration of 3 × 105 cells in 100 μL injection volume.

Oscillatory Rheology

Oscillatory rheology experiments were conducted on an ARG2 rheometer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE) with a 20-mm-diameter stainless steel parallel-plate geometry. Precursor solutions were prepared as described above. A 30 μl hydrogel precursor solution was deposited on the rheometer stage, and the geometry was set at a 100-μm gap. Mineral oil was used to seal the geometry and prevent dehydration of the hydrogel. Mechanical properties of the hydrogels were measured in the linear viscoelastic regime where the modulus is independent of the level of applied stress or strain. Gelation of hydrogels was monitored using a time sweep conducted in the linear viscoelastic regime at 1% strain and an angular frequency of 1 Hz. This experiment was followed with a frequency sweep from 0.1 to 100 rad/s conducted at 1% strain and an amplitude sweep from 0.1 to 1000% strain. Experiments were repeated on three samples for each condition and the shear modulus reported as the simple mean. The error is reported as the standard deviation of the samples tested.

Cell Encapsulation and Viability

In vitro assays of cell viability were completed as previously described [48]. BM-MSCs were encapsulated in RLP-AM/HA-SH gel hydrogels at a cell density of 1 × 106 cells/mL. Precursors were vortex mixed and then pipette mixed with cells before being deposited onto 35-mm MatTek dish, and incubated in a 37 °C incubator for 1 h. Hydrogels were then placed into cell growth media from the MSCGM Mesenchymal Stem Cell Growth BulletKit for BM-MSCs (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) and placed in a cell culture incubator at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Live/Dead staining (LifeTechnologies, Eugene, OR) was utilized to determine viability of BM-MSCs. Hydrogels were washed in PBS and placed in PBS containing 2 mM calcein AM and 4 mM ethidium homodimer-1 for 20 min at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and imaged while alive. Cell-laden hydrogels were then imaged via laser scanning confocal microscopy on a Zeiss LSM 710 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY). Excitation (λex) and emission (λem) wavelengths of calcein AM are λex 488 nm/λ490–552 nm, while those of the ethidium homodimer-1 are λex 561 nm/λem 560–735 nm. Z-stack images were acquired from the cell-laden hydrogels on days 1, 3, 7, and 14 and representative images in maximum intensity projections are reported.

Animal Procedures

A total of 54 New Zealand White rabbits (Charles River, Wilmington, MA), each weighing 2.5–3.5 kg, were used in this study. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Rabbits were allowed to adapt to the local environment for 1 week minimum before being used in experiments, at which point they were between 4 and 5 months old.

Injection

Unilateral vocal fold injection (100 μL per injection) of three RLP formulations was performed in 50 male rabbits. Twenty rabbits were injected with RLP/HA gel (7.5 mg total solids, 0.121 EU per injection), 20 with RLP-AM/HA-SH gel (7.5 mg total solids, 0.062 EU per injection), and 10 with RLP solution (5.7 mg total solids, 0.001 EU per injection). Contralateral vocal folds served as naïve control tissue. Rabbits were sedated with ketamine (10 mg/kg) and dexmedetomidine (0.09 mg/kg) and administered 2–5% isoflurane as needed to reduce vocal fold movement, along with supplemental O2. Animals underwent direct laryngoscopy with a Pilling infant Hollinger laryngoscope (Pilling, Horsham, PA) followed by injection of 100 μL injectate into the membranous vocal fold using a 25-gauge needle (Instrumentarium, Terrebonne, QC, Canada). Anesthesia was reversed with atipamezole (0.09 mg/kg).

Acute Injury and Injection

Four female rabbits underwent unilateral vocal fold injury followed by immediate injection of RLP hydrogel as described in previous studies of injectable biomaterials in early vocal fold wound healing [54–61]. Two rabbits were injected with 100 μL RLP-AM/HA-SH gel (total solids 7.5 mg, 0.062 EU per injection). Two were injected with RLP-AM/HA-SH gel + cell formulation consisting of 15 μL human BM-MSCs suspended in 85 μL RLP-AM/HA-SH gel. Contralateral vocal folds served as uninjured, uninjected controls. After sedation, anesthesia, and direct laryngoscopy, rabbits underwent indirect laryngoscopy with a 0° rigid endoscope (Karl Storz, El Segundo, CA) connected to a video camera and monitor. A 2-mm cup forceps (MicroFrance, Terrebonne, QC, Canada) was used to remove a portion of the membranous vocal fold mucosa, followed immediately by injection of RLP hydrogel into the injury site. Injection was confirmed by indirect laryngoscopy. After anesthesia reversal, pain was controlled with buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg).

Euthanasia

Injected rabbits were euthanized on days 5 and 21 after injection, with 25 sacrificed at each timepoint. Rabbits who underwent injury and injection were sacrificed on day 5. Rabbits were sedated with ketamine (10 mg/kg) and dexmedetomidine (0.09 mg/kg) and euthanized with Beuthanasia-D (0.05 mg/kg). Larynges were harvested and placed in PBS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Rheology of Vocal Folds

To assess viscoelasticity of injected versus naïve vocal folds, a total of 46 vocal folds were designated for rheological testing, completed as previously described [52, 62]. Larynges were hemisected along the posterior aspect and vocal folds were dissected out of the thyroid cartilage. Vocal folds were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C prior to testing, then thawed and hydrated in a 1% PBS solution at room temperature. Rheological testing was performed with a Bohlin Gemini-150 controlled stress rotational rheometer (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Worcestershire, UK) using an 8-mm parallel plate system. Temperature at the bottom plate was maintained at 37 °C using a water jacket attached to a F25-ME external heating and circulation unit (Julabo USA Inc., Allentown, PA). To prevent tissue slippage at the plates, 220 grit sandpaper (Norton Abrasives, Worcester, MA) was attached to both plates with Permabond 105 (Permabond LLC, Pottstown, PA). Sandpaper was replaced every three samples. Tissue samples were placed between the plates, and the upper plate was lowered in increments of approximately 100 μm until the normal force applied to the tissue remained above 25 g for approximately 5 s. Gap size was then decreased by an additional 20%, and the plates left in place for 5 min prior to testing to allow the forces to equilibrate. Tissue hydration was maintained by applying 1% PBS around the samples as needed. Frequency sweeps were performed using a controlled stress paradigm from 0.01 to 10 Hz, taking 7 sample points every decade. Elastic shear moduli (G′) and viscous moduli (G″) were computed from the results. All rheological measurements were taken without knowledge of the treatment condition.

Histopathology

Vocal folds were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for at least 2 days and processed and embedded in paraffin for histological analysis following standard procedures. Coronal sections of 5 μm were cut with a microtome (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Slides were imaged with an Eclipse Ti-S light microscope at × 4, × 10, and × 20 magnification and photographed with a DS Ri2 cooled color digital camera and NIS Elements imaging software (all Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Midmembranous vocal fold sections were assessed for inflammation, fibrosis, and other tissue abnormalities by an experienced pathologist who was blinded to the conditions.

Statistical Analysis

Rheological data of vocal fold tissues were analyzed using mixed models of the relationship between frequency and either elastic or viscous modulus at each timepoint (day 5 or 21). Due to non-linearity, frequency and elastic and viscous moduli were log-transformed for analysis. Fixed effects were defined as treatment group (RLP/HA gel, RLP-AM/HA-SH gel, RLP solution, or control), frequency, and their interactions. Intercepts for each vocal fold were included as repeated measures with autoregressive covariance. The α level was set at 0.05. Results were obtained using SAS software procedure PROC MIXED (Version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Mechanical Properties

Mechanical properties of these hydrogels in vitro, prior to their use in vivo, were evaluated via oscillatory rheology to confirm that the solutions would form hydrogels as expected. RLP/HA gel solutions were expected to form viscoelastic networks as a result of electrostatic interactions between the lysine-rich RLP and the negatively charged HA. RLP/HA immediately formed a hydrogel at 37 °C with a storage modulus of 632 ± 35 Pa (Fig. 2a, b). The chemically crosslinked RLP-AM/HA-SH gel formed a stiffer hydrogel via Michael-type addition reaction between the RLP and the HA; given the functionalization of the biopolymers, no additional crosslinker was added and no side products were produced. The functionalization of the biopolymers reduces their net charge, and thus, the immediate formation of a physical network was not observed; the gel point was observed 40 min after mixing at 37 °C and the hydrogel reached a stable modulus of 1570 ± 500 Pa (Fig. 2c, d), similar to those reported for human vocal fold tissue (shear modulus G′ = 400–2000 Pa) [63, 64]. All of the solutions and hydrogels employed in these experiments were homogeneous and transparent, suggesting the solubility of both the HA and the RLP and the formation of uniform networks. The formation of a robustly crosslinked network incorporating both biopolymers is also suggested by the frequency independence of the shear storage moduli.

Fig. 2.

Oscillatory rheology of physical and chemically crosslinked hydrogels. a Time sweep data for RLP/HA physically crosslinked hydrogels, which formed immediately at 37 °C. b Frequency sweep measurements of RLP/HA physical shows the formation of a physical gel at 37 °C. c Time sweep data for RLP-AM/HA-SH chemically crosslinked hydrogels showing a gel point of approximately 40 min. d Frequency sweep data for RLP-AM/HA-SH gel indicating that stable hydrogels with solid-like properties are formed

Cytocompatibility

The ability to encapsulate BM-MSCs with high cell viability in the chemically crosslinked RLP-AM/HA-SH was evaluated via 3D encapsulation of BM-MSCs. Cell viability was evaluated via staining with calcein (live) in green and ethidium homodimer (dead) in red; confocal images of the cell-laden hydrogels at days 1, 3, 7, and 14 are presented in Fig. 3. Human BM-MSCs maintained high cell viability (93 ± 5% viability) within the hydrogels over a period of at least 14 days.

Fig. 3.

Cytocompatibility of RLP-AM/HA-SH hydrogels. Confocal z-stack maximum intensity projections images for 3D cultures of encapsulated human BM-MSCs in RLP-AM/HA-SH hydrogels at a day 1, b day 3, c day 7, and d day 14. Colors indicate live cells (calcein, green) and dead cells (ethidium homodimer, red)

In Vivo Studies

In vivo biocompatibility and viscoelasticity of RLP/HA hydrogels were assessed in rabbit vocal folds via injection of hydrogels alone or after acute injury. All animals tolerated vocal fold procedures and presence of biomaterials throughout the study period, up to 21 days postinjection. There were no adverse events, no signs of respiratory compromise such as stridor or cyanosis, and no attrition before study endpoints. Larynges were harvested and vocal fold tissues dissected out for further rheological and histopathological analyses.

Rheology of Vocal Folds

Elastic (G′) and viscous (G″) moduli of rabbit vocal folds injected with RLP/HA gels, RLP-AM/HA-SH gels, or RLP solution were assessed days 5 and 21 postinjection. Naïve rabbit vocal folds were used as controls. One vocal fold from the RLP/HA gel day 5 group was excluded from analysis due to equipment malfunction resulting in repeated testing of the tissue, which could invalidate rheological measures. One vocal fold from the control day 5 group was excluded due to inconsistent results suggestive of procedural errors in dissection or testing. Analyses were completed with and without this vocal fold without differing results.

Type 3 tests of fixed effects in the mixed models demonstrated that elastic modulus increased as an effect of frequency at day 5 (F(1,416) = 352.28; p < .0001; Fig. 4a) and 21 (F(1,456) = 389.25; p < .0001; Fig. 4b). Viscous modulus increased as an effect of frequency at day 5 (F(1,416) = 62.78; p < .0001; Fig. 4c) and 21 (F(1,456) = 110.10; p < .0001; Fig. 4d). There was no evidence for main (p = 0.783–0.894) or interaction effect (p = 0.508–0.957) of treatment group on elastic or viscous moduli at any time point. Thus, at 5 and 21 days after injection, vocal fold viscoelasticity did not differ among vocal folds injected with RLP/HA gel, RLP-AM/HA-SH gel, RLP solution, and naïve controls.

Fig. 4.

Viscoelasticity of rabbit vocal folds days 5 and 21 after injection with RLP hydrogels. Data are shown in log–log plots with mean elastic (G′) or viscous modulus (G″) as a function of frequency at day 5 and 21 postinjection of RLP/HA gel (n = 4–5 vocal folds per timepoint), RLP-AM/HA-SH gel (n = 5 per timepoint) or RLP solution (n = 3 per timepoint). Naïve rabbit vocal folds were used as controls (n = 9–10 per timepoint). Due to the logarithmic scale, group variances are not included

Histopathology

To determine biocompatibility of RLP-based hydrogels in vivo in vocal fold tissue, rabbit vocal folds were injected with RLP/HA gel, RLP-AM/HA-SH gel, and RLP solution and harvested at days 5 and 21. A small number of vocal folds were injured, immediately injected with RLP-AM/HA-SH gel or RLP-AM/HA-SH gel + human BM-MSCs, and harvested at day 5.

Vocal Fold Injections

Gel was not visible in the vast majority of vocal folds at 5 or 21 days. Epithelium and thyroarytenoid muscle were intact in injected vocal folds in all treatment groups and all time points (Fig. 5). Lamina propria was normal in all treatment groups at day 5 postinjection (Fig. 5a, c, e cf. g). Lamina propria in Fig. 5c appears thin due to posterior location and angle of tissue during sectioning. At day 21, vocal folds injected with RLP/HA gel and RLP-AM/HA-SH gel demonstrated increased edema and number of fibroblasts, neutrophils, and lymphocytes (Fig. 5b, d). Vocal folds injected with RLP solution were normal (Fig. 5e, f). Gel was found dispersed within the thyroarytenoid muscle of one vocal fold injected with RLP-AM/HA-SH gel at day 21, with a significant increase in inflammatory cells consistent with a foreign body giant cell response (Fig. 6). The presence of gel in muscle was likely due to excessively deep injection. Epithelium was intact and lamina propria was mildly inflamed and edematous.

Fig. 5.

Rabbit vocal folds days 5 and 21 after injection with RLP hydrogels. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. All demonstrate intact epithelium without inflammation and normal muscularis. a RLP/HA gel at day 5. The lamina propria is essentially unremarkable, with no significant edema or inflammation. b RLP/HA gel at day 21. The lamina propria is more edematous compared to day 5 and has relatively more small spindled fibroblasts and scattered neutrophils and lymphocytes. c RLP-AM/HA-SH gel at day 5. The lamina propria is essentially unremarkable, with no significant edema or inflammation. Lamina propria appears thin due to posterior location and angle of tissue during sectioning. d RLP-AM/HA-SH gel at day 21. The lamina propria is more edematous compared to day 5 and has relatively more small spindled fibroblasts and scattered neutrophils and lymphocytes. e RLP solution at day 5. The lamina propria is essentially unremarkable, with no significant edema or inflammation. f RLP solution at day 21. The lamina propria is essentially unremarkable, with no significant edema or inflammation. g Control naïve vocal fold. Arrows: lymphocytes. Black arrowheads: neutrophils. White arrowheads: fibroblasts. All × 20 magnification; scale bars 100 μm

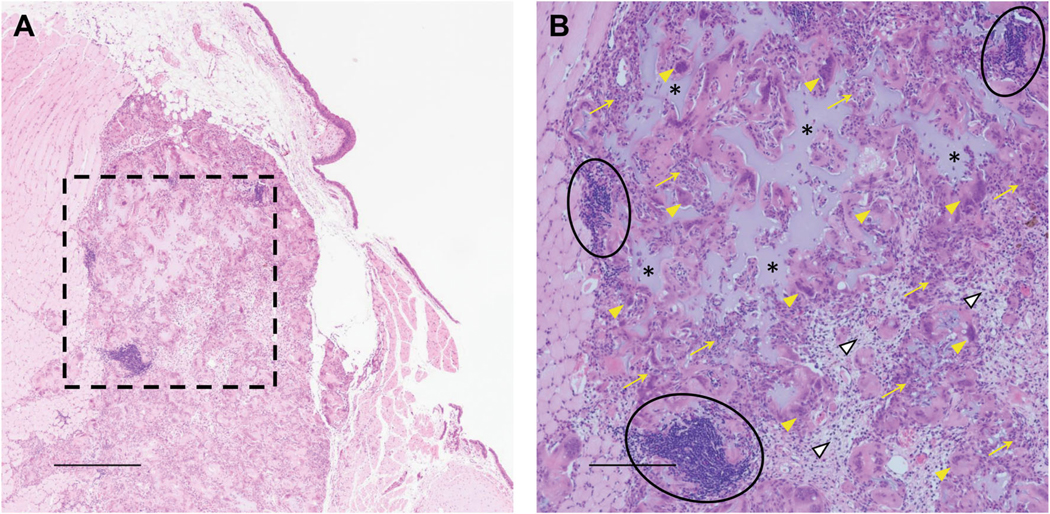

Fig. 6.

Rabbit vocal fold 21 days after deep RLP-AM/HA-SH gel injection. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. a Low magnification shows intact epithelium and a mild degree of inflammation and edema in the lamina propria. Most evident is a well-demarcated inflammatory mass in the muscularis that contains extracellular amorphous amphophilic material; × 4. Scale bar 500 μm. b High magnification of box in a shows the inflammatory mass comprises amphophilic amorphous extracellular material (asterisks) surrounded by epithelioid histiocytes (yellow arrows), giant cells (yellow arrowheads), plump fibroblasts (white arrowheads), and clusters of lymphocytes (circles) consistent with a foreign body giant cell response; × 10. Scale bar 200 μm

Acute Injury

By day 5, all injured and injected vocal folds developed ulcerated polypoid or nodular masses with dense inflammatory cellular infiltrates throughout the lamina propria (Fig. 7). In one RLP-AM/HA-SH gel and one RLP-AM/HASH gel + cell vocal fold, granulation tissue extended to but not through the muscle (Fig. 7a–c, g–i). In one RLP-AM/HA-SH gel + cell vocal fold, inflammatory infiltrate extended through the muscle to thyroarytenoid cartilage (Fig. 7d–f). The other developed more mature granulation tissue and relatively less inflammation (Fig. 7g–i).

Fig. 7.

Rabbit vocal folds 5 days after injury and immediate injection of RLP-AM/HA-SH gel with and without human BM-MSCs. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. a–c RLP-AM/HA-SH gel. Low magnification shows a nodular mass expanding the lamina propria, covered by focally ulcerated epithelium. The expanded area of the lamina propria comprises cellular granulation tissue with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate, plump fibroblasts, scattered histiocytes, rare giant cells, and increased vascularity. The granulation tissue pushes up against the muscularis. d–f RLP-AM/HA-SH gel + cell, rabbit 3588. Low magnification shows a mass expanding the lamina propria forming a small polyp that is covered by a markedly ulcerated epithelium. The ulcer is demarcated by denuded epithelium with fibrin forming the ulcer base. Numerous neutrophils are entrapped within the fibrin. Deep to the ulcer is a dense inflammatory infiltrate comprising predominantly lymphocytes and neutrophils, with associated fibroblasts and scattered histiocytes, including a few giant cells. This mixed inflammatory infiltrate extends through the entire muscularis layer down to cartilage. g–i RLP-AM/HA-SH gel + cell, rabbit 3589. Low magnification shows a mass expanding the lamina propria forming an ulcerated polyp. The ulcer base is largely comprised of fibroblasts and is beginning to be re-epithelialized. Deep to the ulcer is more mature granulation tissue compared to 3588. The granulation tissue predominantly comprises fibroblasts with relatively fewer inflammatory cells. A few giant cells are present. The muscularis is relatively intact and free from involvement. a, d, g × 4. Scale bar 500 μm. b, e, h × 10 magnification of dashed boxes in a, d, g. Scale bar 200 μm. e Extends slightly superior to box in d. c, f, i × 20 magnification of solid boxes in a, d, g. Scale bar 100 μm. White arrowheads: fibroblasts. Black arrows: lymphocytes. Black arrowheads: neutrophils. Yellow arrows: histiocytes. Yellow arrowheads: giant cells

Discussion

Vocal fold scarring is characterized by fibrotic changes in lamina propria ECM, which results in increased tissue viscosity and stiffness and impaired vocal fold vibration [7, 12, 65]. Biomaterials for vocal fold tissue engineering must improve viscoelastic properties of the impaired tissue to normal levels. Viscoelasticity of HA-based injectable biomaterials for vocal fold tissue engineering closely resembles that of human vocal fold mucosa [66, 67]. In a rabbit model, HA-based biomaterials preserved vocal fold elastic and viscous moduli 2 months after injection [66] and dynamic viscosity for up to 6 months [68–70]. Non-HA-based biomaterials used for voice augmentation procedures including polytetrafluoroethylene, calcium hydroxylapatite, crosslinked collagen, and micronized, decellularized human dermis are stiffer than human vocal fold mucosa [66, 67, 71], which persists after injection into rabbit vocal folds [66, 68, 69]. Here, mechanical properties of physically crosslinked RLP/HA (~ 600 Pa) and chemically crosslinked RLP-AM/HA-SH hybrid hydrogels (~ 1500 Pa) were similar to those reported for human vocal fold tissue (400–2000 Pa) [63, 64]. In vivo, rabbit vocal folds injected with RLP-based biomaterials retained normal viscoelastic properties days 5 and 21 postinjection. These findings demonstrate that, like other HA-based hydrogels, RLP/HA and RLP-AM/HA-SH gels replicate mechanical properties of vocal fold mucosa in vitro and in vivo.

Previously, we found minimal to no inflammation induced by RLP solutions in murine subdermal dorsum days 5 and 21 after injection [46]. Here, rabbit vocal fold tissues were histologically normal after injection of RLP solution, demonstrating acute biocompatibility of RLP in vocal fold lamina propria. In our prior work, inflammation in murine dorsum induced by RLP hydrogels was associated with THP crosslinker [46]. In the present work, chemically crosslinked RLP-AM/HA-SH was crosslinked via Michael-type addition chemistry, which is a highly efficient reaction with no crosslinker needed nor by-products produced and which has been shown to be suitable for in situ reaction in biological systems [51]. RLP/HA and RLP-AM/HA-SH hydrogel injections into lamina propria resulted in no inflammation at day 5 but mild inflammatory changes at day 21. Significant inflammatory reaction to intramuscular RLP-AM/HA-SH gel at day 21 in one rabbit in our study emphasizes the need to control depth of injection in vocal fold procedures to deliver biomaterials to the target tissue layer. It is noteworthy that epithelium was normal and lamina propria was only mildly inflamed, and that this rabbit, like the others in this study, did not suffer adverse health effects after injection. Given that injections to the lamina propria in our study induced only mild, non-fibrotic histopathological changes by day 21 and preserved vocal fold viscoelasticity, both RLP/HA and RLP-AM/HASH hydrogels appear favorable for vocal fold tissue engineering.

We used human BM-MSCs in a preliminary investigation of the effect of RLP and HA hybrid hydrogel delivery of stem cells on acute vocal fold injury. Previous studies demonstrated that BM-MSCs retain high viability after injection through needles of various gauges and lengths used in vocal fold procedures [53], and that their gene expression resembles that of vocal fold fibroblasts under vibratory strain [65]. In the present work, chemically crosslinked RLP-AM/HA-SH gel had greater mechanical stability than physically crosslinked RLP/HA gel in vitro and was thus selected for further study of cytocompatibility for potential cell delivery. We confirmed high viability (> 90%) of BM-MSCs up to 14 days in a 3D encapsulation study. We thus used RLP-AM/HA-SH hydrogel to deliver 3 × 105 human BM-MSCs to acutely injured rabbit vocal folds. In prior work, this high cell dose resulted in persistence of human cells 2 weeks after injection and attenuated established scar in rabbit vocal folds 10 weeks after treatment, with favorable outcomes in viscoelasticity and gene expression related to inflammation and ECM remodeling [52].

Rabbit vocal fold wound healing is well-documented in the literature, providing ample comparison to our studies. On days 3–5 after cup forceps injury, vocal fold mucosa is characterized by inflammatory cellular infiltrate in the lamina propria and ulceration tissue that gives way to hypertrophic cuboidal epithelium with loss of polarity [72–74]. We found similar inflammation and ulceration day 5 after injury and immediate injection of RLP-AM/HA-SH hydrogel, with and without human BM-MSCs. Depth of inflammatory infiltrate and maturity of granulation tissue was not linked to presence of cells. Rabbits in our study did not receive immunosuppressive therapy, and our results are consistent with prior rabbit vocal fold xenograft studies without immunosuppression. Inflammation persisted up to 10 weeks after injection of human BM-MSCs in established scar, with increased severity when cells were delivered in HyStem-VF (thiolated carboxymethyl HA/thiolated gelatin/PEG diacrylate hydrogel) [52]. Injection of human adipose-derived MSCs alone or in HA-alginate gel immediately after injury resulted in inflammation at 3 months [58, 61]. However, these studies also demonstrated that human stem cells and injected biomaterials improved viscoelasticity and reduced signs of fibrosis such as collagen I deposition and elastic fiber disorganization in scarred vocal folds [52, 58, 61]. Therefore, our finding of inflammation during early wound healing in injured vocal folds injected with RLP-AM/HA-SH with and without human BM-MSCs does not preclude later improvements in lamina propria ECM organization and biomechanical properties during remodeling.

One limitation of this study is that we did not assess in vivo degradation of hydrogels. Despite intraoperative confirmation of injection, histology did not reveal gel in lamina propria at day 5 or 21, alone or after injury. Gel inadvertently injected into muscle was broadly dispersed throughout tissue at day 21 rather than aggregated, suggesting quick degradation or migration of these materials. Degradation should be assessed in future work. We did not include previously studied HA-based materials such as Hylan-B [68, 69] or HyStem-VF [52] for direct comparison. Each of our in vivo experiments included animals of one sex only, with different sexes used for injections alone versus after injury. Sex differences are understudied in basic and translational otolaryngology and animal vocal fold research [75, 76]. Our results regarding acute vocal fold wound healing are preliminary due to low animal numbers and descriptive analysis of various cells in the wound bed. Our 5- and 21-day timepoints for simple injection demonstrate acute biocompatibility of RLP and HA hybrid hydrogels, but more work is needed to assess long-term effects. Tissue remodeling is not expected to begin until 3 weeks postinjury [77], and a 6-month timeframe has been recommended for assessment of chronic vocal fold scarring in the rabbit model [78]. Future work with RLP and HA hybrid hydrogels should extend through the remodeling phase of wound healing to assess the ability of these materials to deliver cells and mitigate vocal fold scar.

Conclusions

Herein, we describe synthesis and characterization of injectable hydrogels that combine favorable properties of RLP and HA for vocal fold tissue engineering. Physically crosslinked RLP/HA and chemically crosslinked RLP-AM/HA-SH formed gels with mechanical properties that resembled human vocal fold mucosa and maintained these properties after injection into rabbit vocal folds. Both hydrogels provoked only mild inflammation in vocal fold lamina propria with demonstrated safety in the airway for up to 3 weeks. Chemically crosslinked gel was used as a carrier for human BM-MSCs in acute injury, without adverse effects or increased inflammation beyond typical wound healing. Taken together, these results demonstrate that RLP and HA-based biomaterials are highly promising for engineering the vocal fold lamina propria.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge instrument resources from the Delaware COBRE program, supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS, 1-P30-GM110758–01, 1P30-GM103519, and 1-P20-GM104316), and funding support from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (R01 DC011377 and T32 DC009401), and the National Science Foundation (DMR-1609544). The views represented do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank Professor April Kloxin for the generous use of the HPLC, Jeanna Stiadle, MS for assistance with animal procedures, Drew Roenneberg, MS and Sierra Raglin, BS for assistance with histology, Glen Leverson, PhD and Yue Ma, PhD for assistance with statistical analysis, and David Yang, MD for histopathology interpretation. Microscopy access was supported by grants from the NIH-NIGMS (P20 GM103446), the NSF (IIA-1301765) and the State of Delaware.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s40883-019-00094-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hirano M Morphological structure of the vocal cord as a vibrator and its variations. Folia Phoniatr. 1974;26:89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirano M, Kurita S, Nakashima T. The structure of the vocal folds. In: Stevens KN, Hirano M, editors. Vocal fold physiology. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press; 1981. p. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray SD. Cellular physiology of the vocal folds. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2000;33:679–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray SD, Alipour F, Titze IR, Hammond TH. Biomechanical and histologic observations of vocal fold fibrous proteins. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woo P, Casper J, Colton R, Brewer D. Diagnosis and treatment of persistent dysphonia after laryngeal surgery: a retrospective analysis of 62 patients. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:1084–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benninger M, Alessi D, Archer S, Bastian R, Ford C, Koufman J, et al. Vocal fold scarring: current concepts and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;115:474–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thibeault SL, Gray SD, Bless DM, Chan RW, Ford CN. Histologic and rheologic characterization of vocal fold scarring. J Voice. 2002;16:96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirano S, Minamiguchi S, Yamashita M, Ohno T, Kanemaru S, Kitamura M. Histologic characterization of human scarred vocal folds. J Voice. 2009;23:399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bless DM, Welham NV. Characterization of vocal fold scar formation, prophylaxis, and treatment using animal models. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;18:481–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen JK, Thibeault SL. Current understanding and review of the literature: vocal fold scarring. J Voice. 2006;20:110–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedrich G, Dikkers FG, Arens C, Remacle M, Hess M, Giovanni A, et al. Vocal fold scars: current concepts and future directions. Consensus report of the phonosurgery committee of the european laryngological society. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270: 2491–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graupp M, Bachna-Rotter S, Gerstenberger C, Friedrich G, Fröhlich-Sorger E, Kiesler K, et al. The unsolved chapter of vocal fold scars and how tissue engineering could help us solve the problem. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273: 2279–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Long JL. Tissue engineering for treatment of vocal fold scar. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;18:521–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford CN, Baker DC. Paradigms and progress in vocal fold restoration. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1709–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L, Stiadle JM, Lau HK, Zerdoum AB, Jia X, Thibeault SL, et al. Tissue engineering-based therapeutic strategies for vocal fold repair and regeneration. Biomaterials. 2016;108:91–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sato K, Hirano M, Nakashima T. Fine structure of the human newborn and infant vocal fold mucosae. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:417–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang J, Lin E, Hanson DG. Vocal fold physiology. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2000;33:699–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaston J, Thibeault SL. Hyaluronic acid hydrogels for vocal fold wound healing. Biomatter. 2013;3:e23799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burdick JA, Prestwich GD. Hyaluronic acid hydrogels for biomedical applications. Adv Mater. 2011;23:H41–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Highley CB, Prestwich GD, Burdick JA. Recent advances in hyaluronic acid hydrogels for biomedical applications. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016;40:35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JH, Kim DW, Kim EN, Park S-W, Kim H- B, Oh SH, et al. Evaluation of the poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)/pluronic F127 for injection laryngoplasty in rabbits. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151:830–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaston J, Bartlett RS, Klemuk SA, Thibeault SL. Formulation and characterization of a porous, elastomeric biomaterial for vocal fold tissue engineering research. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2014;123: 866–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karajanagi SS, Lopez-Guerra G, Park H, Kobler JB, Galindo M, Aanestad J, et al. Assessment of canine vocal fold function after injection of a new biomaterial designed to treat phonatory mucosal scarring. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120:175–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hertegård S, Hallén L, Laurent C, Lindström E, Olofsson K, Testad P, et al. Cross-linked hyaluronan versus collagen for injection treatment of glottal insufficiency: 2-year follow-up. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124:1208–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartlett RS, Thibeault SL, Prestwich GD. Therapeutic potential of gel-based injectables for vocal fold regeneration. Biomed Mater. 2012;7:024103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hallén L, Johansson C, Laurent C. Cross-linked hyaluronan (Hylan B gel): a new injectable remedy for treatment of vocal fold insufficiency - an animal study. Acta Otolaryngol. 1999;119:107–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haas F, Gorb S, Wootton RJ. Elastic joints in dermapteran hind wings: materials and wing folding. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2000;29:137–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burrows M, Shaw SR, Sutton GP. Resilin and chitinous cuticle form a composite structure for energy storage in jumping by froghopper insects. BMC Biol. 2008;6:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vincent JFV, Wegst UGK. Design and mechanical properties of insect cuticle. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2004;33:187–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young D, Bennet-Clark H. The role of the tymbal in cicada sound production. J Exp Biol. 1995;198:1001–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennet-Clark H Tymbal mechanics and the control of song frequency in the cicada Cyclochila australasiae. J Exp Biol. 1997;200:1681–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fonseca PJ, Clark H-CB. Asymmetry of tymbal action and structure in a cicada: a possible role in the production of complex songs. J Exp Biol. 1998;201:717–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weis-Fogh T A rubber-like protein in insect cuticle. J Exp Biol. 1960;37:889–907. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elvin CM, Carr AG, Huson MG, Maxwell JM, Pearson RD, Vuocolo T, et al. Synthesis and properties of crosslinked recombinant pro-resilin. Nature. 2005;437:999–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qin G, Hu X, Cebe P, Kaplan DL. Mechanism of resilin elasticity. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li L, Kiick KL. Resilin-based materials for biomedical applications. ACS Macro Lett. 2013;2:635–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li L, Teller S, Clifton RJ, Jia X, Kiick KL. Tunable mechanical stability and deformation response of a resilin-based elastomer. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:2302–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li L, Tong Z, Jia X, Kiick KL. Resilin-like polypeptide hydrogels engineered for versatile biological function. Soft Matter. 2013;9: 665–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGann CL, Akins RE, Kiick KL. Resilin-PEG hybrid hydrogels yield degradable elastomeric scaffolds with heterogeneous microstructure. Biomacromolecules. 2016;17:128–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiao T, Farran A, Jia X, Clifton RJ. High frequency measurements of viscoelastic properties of hydrogels for vocal fold regeneration. Exp Mech. 2009;49:235–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teller SS, Farran AJE, Xiao L, Jiao T, Duncan RL, Clifton RJ, et al. High-frequency viscoelastic shear properties of vocal fold tissues: implications for vocal fold tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:2008–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li L, Kiick KL. Transient dynamic mechanical properties of resilin-based elastomeric hydrogels. Front Chem. 2014;2:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li L, Mahara A, Tong Z, Levenson EA, McGann CL, Jia X, et al. Recombinant resilin-based bioelastomers for regenerative medicine applications. Adv Healthc Mater. 2016;5:266–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim Y, Liu JC. Protein-engineered microenvironments can promote endothelial differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in the absence of exogenous growth factors. Biomater Sci. 2016;4:1761–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lv S, Bu T, Kayser J, Bausch A, Li H. Towards constructing extracellular matrix-mimetic hydrogels: an elastic hydrogel constructed from tandem modular proteins containing tenascin FnIII domains. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:6481–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li L, Stiadle JM, Levendoski EE, Lau HK, Thibeault SL, Kiick KL. Biocompatibility of injectable resilin-based hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2018;106:2229–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Charati MB, Ifkovits JL, Burdick JA, Linhardt JG, Kiick KL. Hydrophilic elastomeric biomaterials based on resilin-like polypeptides. Soft Matter. 2009;5:3412–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lau HK, Paul A, Sidhu I, Li L, Sabanayagam CR, Parekh SH, et al. Microstructured elastomer-PEG hydrogels via kinetic capture of aqueous liquid–liquid phase separation. Adv Sci. 2018;5:1701010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shu XZ, Liu Y, Luo Y, Roberts MC, Prestwich GD. Disulfide crosslinked hyaluronan hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3:1304–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ozdemir T, Fowler EW, Liu S, Harrington DA, Witt RL, Farach-Carson MC, et al. Tuning hydrogel properties to promote the assembly of salivary gland spheroids in 3D. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2016;2:2217–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nair DP, Podgórski M, Chatani S, Gong T, Xi W, Fenoli CR, et al. The thiol-Michael addition click reaction: a powerful and widely used tool in materials chemistry. Chem Mater. 2014;26:724–44. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bartlett RS, Guille JT, Chen X, Christensen MB, Wang SF, Thibeault S. Mesenchymal stromal cell injection promotes vocal fold scar repair without long-term engraftment. Cytotherapy. 2016;18:1284–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen X, Foote AG, Thibeault SL. Cell density, dimethylsulfoxide concentration and needle gauge affect hydrogel-induced bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cell viability. Cytotherapy. 2017;19: 1522–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hirano S, Bless DM, Rousseau B, Welham N, Montequin D, Chan RW, et al. Prevention of vocal fold scarring by topical injection of hepatocyte growth factor in a rabbit model. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:548–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hansen JK, Thibeault SL, Walsh JF, Shu XZ, Prestwich GD. In vivo engineering of the vocal fold extracellular matrix with injectable hyaluronic acid hydrogels: early effects on tissue repair and biomechanics in a rabbit model. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2005;114:662–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cedervall J, Ährlund-Richter L, Svensson B, Forsgren K, Maurer FHJ, Vidovska D, et al. Injection of embryonic stem cells into scarred rabbit vocal folds enhances healing and improves viscoelasticity: short-term results. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:2075–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hertegård S, Cedervall J, Svensson B, Forsberg K, Maurer FHJ, Vidovska D, et al. Viscoelastic and histologic properties in scarred rabbit vocal folds after mesenchymal stem cell injection. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim Y-M, Oh SH, Choi J- S, Lee S, Ra JC, Lee JH, et al. Adipose-derived stem cell-containing hyaluronic acid/alginate hydrogel improves vocal fold wound healing. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:E64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Svensson B, Nagubothu RS, Cedervall J, Le Blanc K, Ährlund-Richter L, Tolf A, et al. Injection of human mesenchymal stem cells improves healing of scarred vocal folds: analysis using a xenograft model. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:1370–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thibeault SL, Klemuk SA, Chen X, Quinchia Johnson BH. In vivo engineering of the vocal fold ECM with injectable HA hydrogels—late effects on tissue repair and biomechanics in a rabbit model. J Voice. 2011;25:249–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hong SJ, Lee SH, Jin SM, Kwon SY, Jung KY, Kim MK, et al. Vocal fold wound healing after injection of human adipose-derived stem cells in a rabbit model. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011;131:1198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Woo JH, King SN, Hoffman H, Dailey S, Wang S, Christensen MB, et al. MERS versus standard surgical approaches for porcine vocal fold scarring with adipose stem cell constructs. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;155:612–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chan RW, Rodriguez ML. A simple-shear rheometer for linear viscoelastic characterization of vocal fold tissues at phonatory frequencies. J Acoust Soc Am. 2008;124:1207–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kazemirad S, Bakhshaee H, Mongeau L, Kost K. Non-invasive in vivo measurement of the shear modulus of human vocal fold tissue. J Biomech. 2014;47:1173–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bartlett RS, Gaston JD, Yen TY, Ye S, Kendziorski C, Thibeault SL. Biomechanical screening of cell therapies for vocal fold scar. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21:2437–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choi J-S, Kim NJ, Klemuk S, Jang YH, Park IS, Ahn KH, et al. Preservation of viscoelastic properties of rabbit vocal folds after implantation of hyaluronic acid-based biomaterials. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147:515–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Caton T, Thibeault SL, Klemuk S, Smith ME. Viscoelasticity of hyaluronan and nonhyaluronan based vocal fold injectables: implications for mucosal versus muscle use. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:516–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hertegård S, Dahlqvist Å, Laurent C, Borzacchiello A, Ambrosio L. Viscoelastic properties of rabbit vocal folds after augmentation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128:401–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dahlqvist Å, Gärskog O, Laurent C, Hertegård S, Ambrosio L, Borzacchiello A. Viscoelasticity of rabbit vocal folds after injection augmentation. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:138–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Borzacchiello A, Mayol L, Gärskog O, Dahlqvist Å, Ambrosio L. Evaluation of injection augmentation treatment of hyaluronic acid based materials on rabbit vocal folds viscoelasticity. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2005;16:553–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chan RW, Titze IR. Viscosities of implantable biomaterials in vocal fold augmentation surgery. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:725–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hirano S, Thibeault S, Bless DM, Ford CN, Kanemaru S. Hepatocyte growth factor and its receptor c-met in rat and rabbit vocal folds. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111:661–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thibeault SL, Rousseau B, Welham NV, Hirano S, Bless DM. Hyaluronan levels in acute vocal fold scar. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:760–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Branski RC, Verdolini K, Rosen CA, Hebda PA. Acute vocal fold wound healing in a rabbit model. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2005;114:19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Long JL. Repairing the vibratory vocal fold. Laryngoscope. 2018;128:153–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stephenson ED, Farzal Z, Kilpatrick LA, Senior BA, Zanation AM. Sex bias in basic science and translational otolaryngology research. Laryngoscope. 2019;129:613–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, Longaker MT. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rousseau B, Hirano S, Chan RW, Welham NV, Thibeault SL, Ford CN, et al. Characterization of chronic vocal fold scarring in a rabbit model. J Voice. 2004;18:116–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.