Abstract

Context:

Low energy availability causes disruption of hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion leading to functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA) and hypoestrogenism, which in turn contributes to decreased bone mineral density (BMD) and increased bone marrow adipose tissue (MAT). Transdermal estradiol administration in physiologic doses increases BMD in adolescents and adults with FHA. However, the impact of estrogen replacement on MAT in relation to changes in BMD has not been studied in adolescents and young adults. We hypothesized that physiologic estrogen replacement would lead to decreases in MAT, associated with increases in BMD.

Methods and Materials

We studied 15 adolescent and young adult females with FHA (14–25 years). All participants received a17β- estradiol transdermal patch at a dose of 0.1 mg/day (applied twice weekly) for 12 months. Participants also received cyclic progestin for 10–12 days each month. We quantified MAT (lipid/water ratio) of the fourth lumbar (L4) vertebral body and femoral diaphysis by single proton (1H)-magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and compartmental volumetric BMD of the distal radius and tibia using high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography.

Results

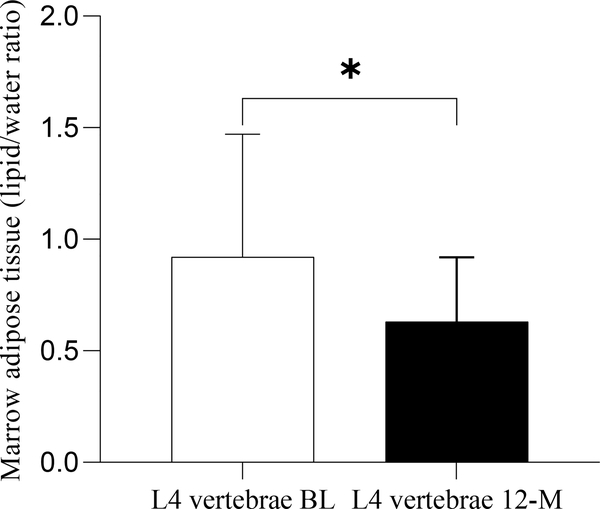

Transdermal estradiol therapy over 12 months resulted in a decrease in MAT at the lumbar (L4) vertebra from 0.92 ± 0.55 at baseline to 0.63 ± 0.29 at 12-months (p=0.008), and an increase in radial and tibial cortical vBMD (p=0.006, p=0.0003). Changes in L4 MAT trended to be inversely associated with changes in radial cortical vBMD (rho= −0.47, p=0.08).

Conclusion

We show that in adolescent and young adult girls with FHA, MAT decreases following transdermal estrogen therapy and these changes are associated with increased cortical vBMD.

Keywords: Marrow adipose tissue, unsaturated marrow adipose tissue, estrogen replacement, adolescents, bone mineral density

1. Introduction

Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA) is one of the most common causes of secondary amenorrhea in young women, and is associated with hypoestrogenemia and increased bone fragility.(1) FHA can result from psychological stress, intense exercise associated with inadequate caloric intake, and low weight eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa.(2) Any of these factors alone or in combination can result in suppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis and hypoestrogenemia.(3)

Hypoestrogenemia contributes to low bone mineral density (BMD) and increased fracture risk in adolescents with anorexia nervosa and in athletes.(4, 5) We have previously shown greater marrow adipose tissue (MAT) content in these hypoestrogenic states.(6, 7) Higher MAT is, in turn, associated with lower areal and volumetric BMD and bone strength estimates.(8) This inverse relationship between MAT and bone is also seen in other osteoporotic states such as in postmenopausal women.(9) Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can differentiate into osteoblasts or adipocytes based on the environmental milieu, which includes estrogen levels.(10) Estrogen promotes osteoblastogenesis and decreases the differentiation of MSCs to adipocytes in a dose dependent fashion.(11, 12) A recent study of older adult women with anorexia nervosa showed a decrease in MAT following estrogen administration.(13) However, there are no data evaluating the effect of estrogen treatment on MAT in adolescent and young adult women with FHA.

Identifying factors that mediate the effects of estrogen in the differentiation of MSCs into osteoblasts or adipocytes may help define novel targets for the treatment of low BMD in this population. Preadipocyte factor (Pref-1) is a protein expressed in marrow that suppresses the differentiation of MSCs along both the adipocyte and osteoblast pathways.(14) Previous studies have shown that Pref-1 levels are elevated in anorexia nervosa, and are associated positively with MAT and inversely with BMD.(15) Further, sclerostin (SOST), a protein secreted from osteocytes, inhibits the osteogenic pathway and induces adipogenesis.(16, 17)

In order to address existing knowledge gaps, we sought to evaluate (i) the effect of transdermal estrogen replacement in adolescent and young adult females with FHA on the quantity of MAT and (ii) how changes in MAT correlate with changes in bone parameters, and with changes in levels of estradiol, Pref-1 and sclerostin. We hypothesized in this preliminary study that physiologic estrogen replacement would decrease MAT and that decrease in MAT would be associated with an increase in BMD.

2. Methods and Materials

The study was performed at the Clinical Research Center of Massachusetts General Hospital. It was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Partners Health Care and is Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant. All subjects 18 years and older, and parents/guardians of subjects younger than 18 years provided written consent, while all subjects 14–17 years old provided signed assent.

2.1. Participants

We enrolled 15 adolescent/young adult girls between 14–25 years with FHA. Ten had a diagnosis of AN and five had FHA consequent to excessive exercise. All subjects with anorexia nervosa met DSM-V psychiatric criteria. Participants in the hyper exercising group were engaged in weight bearing activities for at least four hours each week or ran at least 20 miles every week. Participants were required to be oligo-amenorrheic for study inclusion, which was defined as less than three spontaneous menses in the preceding six months. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, diseases and medications known to affect bone metabolism and MAT, other causes of amenorrhea such as thyroid dysfunction, premature ovarian failure, hyperprolactinemia and polycystic ovary syndrome, evidence of suicidality, psychosis, or substance abuse, and any absolute contraindication to estrogen administration.

2.2. Study Protocol

All participants underwent a detailed history and physical examination, blood tests and a pregnancy test. Weight was obtained in a hospital gown on an electronic scale to the nearest 0.1 kg, and height was obtained in triplicate using a standard stadiometer. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the formula weight (kg)/height (meter)2. Participants also had a bone age radiograph to ensure that the bone age was more than 14 years, to prevent premature epiphyseal closure from estrogen replacement.

Participants received 17β- estradiol as the transdermal patch delivered at a dose of 0.1 mg/day [Vivelle-DotTM (Noven Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Miami, Florida)] twice weekly for a 12-month duration. They also received cyclic micronized progesterone for the first 10–12 days of every month to prevent endometrial hyperplasia from unopposed estrogen delivery. Study endpoints were assessed at baseline and 12 months. Study participants came in for safety checks at 3-, 6- and 9-months, which included a pregnancy test and a brief history and physical examination to assess for side effects.

2.3. High-resolution Peripheral Quantitative Computed Tomography (HR-pQCT)

HR-pQCT was used to measure volumetric BMD (vBMD) at the ultradistal radius and distal tibia (XtremeCT, Scanco Medical AG®, Bassersdorf, Switzerland). The outcome variables include cortical, trabecular and total vBMD (mg hydroxyapatite /cm3) of the tibia and radius.

2.4. Marrow Adipose Tissue (MAT) Assessment

MAT of the fourth lumbar (L4) vertebral body and mid femoral diaphysis was quantified using 1H-Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (H-MRS) as previously described, and expressed as lipid to water ratio.(6, 18) Briefly, lipid content was measured by a 3.0T MR imaging system (Siemens Trio, Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany). For lumbar 1H-MRS, a voxel measuring 15×15×15mm (3.4 ml) was placed within the L4 vertebral body and for femoral 1H-MRS, a voxel measuring 12×12×12mm (1.7 ml) was positioned within the mid-diaphysis. Single-voxel 1H-MRS data was acquired using a point-resolved spatially localized spectroscopy (PRESS) pulse sequence without water suppression with the following parameters: TE of 30 ms, TR of 3,000 ms, 8 acquisitions, 1024 data points, and receiver bandwidth of 2000 Hz. Fitting of all 1H MR spectroscopy data was performed by using LCModel (version 6.3–0 K; Stephen Provencher, Oakville, Ontario, Canada). Data were transferred from the imaging unit to a Linux workstation (Canonical, Lexington, Mass), and metabolite quantification was performed by using eddy current correction and water scaling. A customized fitting algorithm for bone marrow analysis provided estimates for all lipid signals combined (0.9, 1.3, and 2.3 ppm). LC Model bone marrow lipid estimates were automatically scaled to unsuppressed water peak (4.7 ppm) and expressed as lipid to water ratio (LWR).

2.5. Laboratory Measures

Serum samples were collected at baseline and the 12-month visit. An immunochemiluminometric assay was used to measure 17β-estradiol (LabCorp Esoteric Testing, Burlington, NC, sensitivity 25.0 pg/mL; intra-assay coefficient of variation 1.2% to 6.7%). Serum Pref-1 concentrations were measured by a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assay (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN; intra-assay coefficient of variation 3.7%, inter-assay coefficient of variation 6.2%; sensitivity 0.012 ng/ml). An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was used to measure sclerostin (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; sensitivity 1.74 pg/mL; intra-assay CV 2%).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was completed using JMP (version 15, SAS Institute). Values are shown as means ± SD or median ± IQR based on parametric or non-parametric distribution of the variables. P- values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The comparison between the baseline and 12-month parameters was assessed using the paired t-test for parametric variables or Wilcoxon signed rank test for non-parametric variables. Univariate analysis was performed to explore associations of changes in MAT with changes in vBMD, estradiol, Pref-1 and sclerostin. Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients are reported depending on the distribution of the variables.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Clinical characteristics of participants at baseline and 12-months are listed in Table 1. The study included 15 adolescent girls and young adult women with FHA, whose mean age was 19.6 ± 3.2 years and BMI 18.8 ± 1.6 kg/m2. Mean age of menarche was 12.9 ± 1.3 years. Participants had normal mean serum calcium and vitamin D levels (Table 1). The baseline values of lumbar and femoral diaphysis MAT in this group of FHA is higher than that seen in similar aged women with normal weight and menstrual status (data published before- L4 MAT – 0.62 ± 0.28 and femoral diaphysis – 6.34 ± 2.58). (6).

Table 1.

Characteristic of participants in baseline and 12-month follow-up visit

| Base line | 12 months | Pvalue | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 19.55 ± 3.26 | 20.57 ± 3.27 | - |

| Weight (kg) | 49.44 ± 6.17 | 51.18 ± 5.88 | 0.05 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.76 ± 1.62 | 19.39 ± 1.81 | 0.05 |

| %Ideal BMI for age | 87.7 ± 7.6 | 90.75 ± 8.94 | 0.06 |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 9.49 ± 0.24 | 9.30 ± 0.31 | 0.18 |

| 25(OH) vitamin D (ng/ml) | 39.3 ± 11.6 | 34.9 ± 11.7 | 0.40 |

| Estradiol* (pg/ml) | 20 (12.6 – 116.06) | 107 (56.05 – 253.59) | 0.01 |

| Sclerostin (pg/ml) | 83.7 ± 46.1 | 68.6 ± 25.1 | 0.05 |

| Pref-1* (pg/ml) | 71.7 (37.1 – 171.1) | 104.4 (43.2 – 185.0) | 0.69 |

| Radius Cortical vBMD (mg HA/cm3) | 796.0 ± 86.3 | 815.0 ± 67.8 | 0.006 |

| Radius Trabecular vBMD (mg HA/cm3) | 150.6 ± 34.6 | 154.4 ± 33.2 | 0.67 |

| Radius Total vBMD (mg HA/cm3) | 281.2 ± 63.3 | 291.1 ± 73.0 | 0.06 |

| Tibia Cortical vBMD (mg HA/cm3) | 862.3 ± 37.3 | 873.0 ± 32.4 | 0.0003 |

| Tibia Trabecular vBMD (mg HA/cm3) | 178.3 ± 30.3 | 178.2 ± 30.9 | 0.85 |

| Tibia Total vBMD (mg HA/cm3) | 297.9 ± 43.3 | 299.7 ± 42.5 | 0.06 |

| L4 MAT (Lipid/Water) | 0.92 ± 0.55 | 0.63 ± 0.29 | 0.008 |

| Femur Diaphyseal MAT (Lipid/Water) | 8.57 ± 3.13 | 7.86 ± 3.34 | 0.27 |

Mean ± SD or * median (interquartile range) when data were not normally distributed

Wilcoxon signed rank test used for comparison as non-parametric distribution of the variable

3.2. Changes in Clinical Characteristics and Volumetric BMD

Changes in clinical characteristics and vBMD over 12 months are shown in Table 1. Participants trended to have an increase in weight and BMI over the study duration (p=0.05 for both- paired t-test). Cortical vBMD at the radius and tibia increased significantly over the study duration (p=0.006 and 0.0003 respectively- paired t-test). No significant change was noted in trabecular vBMD at the radius and tibia.

3.3. Changes in Marrow Adipose Tissue (MAT)

Treatment with transdermal estradiol over 12 months was associated with a decrease in lumbar MAT (p=0.008- paired t-test) (Table 1 and Figure 1). No changes were observed in MAT content at the femoral diaphysis.

Figure 1:

Marrow adipose tissue in the lumbar vertebrae at baseline and 12-months. Marrow adipose tissue decreased over 12 months of transdermal estradiol administration. * p<0.05

3.4. Changes in Biochemical Parameters

As expected, there was an increase in the serum concentration of estradiol with the transdermal patch (p=0.01). While there was no significant change in Pref-1 levels, we did observe a decrease in sclerostin levels over 12 months (p=0.05- paired t-test ) (Table 1).

3.5. Correlation between Changes in MAT and Changes in vBMD

Changes in total MAT at the L4 vertebra were negatively associated with changes in cortical vBMD at the radius at a trend level (rho= −0.47, p=0.08). No correlations were noted of changes in MAT at the femoral diaphysis with changes in vBMD.

3.6. Correlation between Changes in MAT and Changes in serum Biomarkers and Clinical Features

We did not find any associations of changes in BMI with changes in MAT, vBMD or changes in estradiol levels. There were no significant correlations between changes in MAT with changes in estradiol, Pref-1 or sclerostin levels.

4. Discussion

The effects of estrogen on bone metabolism have long been recognized. More recently, there has been an increasing recognition of MAT as an active endocrine organ with effects on bone metabolism.(19) FHA is a state of hypoestrogenemia, low BMD and increased MAT.(3, 20). The baseline levels of marrow fat are higher in women with FHA as compared to normal weight controls of similar age and the effect of estrogen replacement on these levels is not evaluated. In this preliminary study in adolescents and young adult women with FHA evaluating the effects of exogenous estrogen on MAT, we demonstrate that 12 months of treatment with transdermal estradiol decreases total MAT at the L4 vertebra, similar to reports in postmenopausal women with estrogen deficiency.(21)

Adolescence is uniquely different from adulthood in that both MAT and bone mineral content experience physiologic increases during this period in healthy youth.(22, 23) This in contrast to the typical inverse association between marrow fat and bone mineral content reported in adult life.(24) Despite this basic difference between adolescents and adults, we found that estradiol administration in physiologic replacement doses led to decreases in marrow fat associated with increases in bone density, similar to that observed in an adult population. This has relevance with respect to studies of future therapeutic agents that may target this bone-fat pathway in that similar effects should be expected regardless of age.

Our findings are consistent with the knowledge that estrogen stimulates mesenchymal stem cell differentiation towards osteoblastogenesis and away from adipogenesis.(21, 25) In our study, bone MAT at axial skeleton represented by the L4 vertebra decreased after transdermal estradiol therapy. However, this effect was not seen at the appendicular skeleton (femoral diaphysis). Of note, MAT regulation varies by the location of MAT (appendicular versus axial) as these sites are regulated differently.(26) Studies in mice have shown that MAT in the distal skeleton (femoral diaphysis) has more constitutive MAT, which is stable and less dynamic compared to the regulated proximal (lumbar) MAT, which responds more rapidly to changes in the hormonal and nutritional milieu.(26) The decrease in axial MAT after estrogen replacement in adolescents and young adult females suggests a significant role of estrogen in MAT regulation at the axial skeleton as it is able to overcome the expected physiological increase in MAT seen at this age.(27)

As reported previously (13, 28) we noted an increase in cortical vBMD at both the radius and the tibia following administration of transdermal estradiol but no differences in the trabecular vBMD. The lack of significant differences in trabecular vBMD may be a result of the high variability (as indicated by the high SD) in trabecular bone assessments compared to those of cortical bone, which may have limited our ability to observe significant changes in trabecular vBMD in this preliminary study. Nonetheless, consistent with the fact that estradiol increases differentiation of the MSC along the osteoblastic lineage while decreasing differentiation along the adipocyte lineage, decreases in total MAT at the axial skeleton (L4 vertebra) were associated with increases in cortical vBMD at the radius. This supports data from previous studies that have reported a negative association between MAT and BMD.(8) This is the first human study to suggest an increase in cortical vBMD with a simultaneous decrease in axial MAT after transdermal estradiol administration.

We did not find any changes in preadipocyte factor (Pref)-1 over 12 months in this cohort, but sclerostin levels decreased after 12 months of transdermal estradiol treatment. Studies with a larger number of participants are necessary to determine whether changes in sclerostin mediate the effects of estradiol on bone via changes in MAT.(13, 29, 30)

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a preliminary study with a small sample size and limited power, which decreases our ability to detect significant MAT associations and delineate physiological interactions. However, even with this small sample size we observed changes in MAT content at the axial skeleton following estrogen administration in young women with FHA. We did not have a control group without estradiol treatment to compare the changes over time. Also, although we did not find any correlations of changes in BMI with changes in MAT, the small sample size may limit the power to detect those associations. Also, emerging data suggests that marrow fat assessments with PRESS MRS (using TE of 30 ms) as used in the study may have limitations (31). However, we believe that the results are still valid as the study assesses longitudinal trends and hence the results should be interpretable. Despite its limitations, this study paves the way for future research with a larger sample size to clarify the mechanisms of the effect of estrogen on MAT.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that transdermal estradiol therapy in physiologic replacement doses is effective in reducing lumbar MAT in adolescent girls and young adult women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea.

Highlights.

Marrow adipose tissue (MAT) increases in functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA)

Young women with FHA had decreases in MAT after getting transdermal estrogen

Decreases in MAT were positively associated with increases in some bone parameters

Acknowledgments

We thank the MGH Musculoskeletal Imaging Research Core for the QCT and 1H-MRS measurements, the Brigham Research Assay Core and Main Medical Center Research Institute for batch laboratory testing, and the nurses and stuff of the MGH Clinical Research Center for their dedicated care of the study participants.

This work was supported by Global Foundation of Eating Disorder (VS), K23DK110419-01(VS), K24HD07184 (MM), K24 DK109940 (MB) R0I HD060827 (MM), R01DK062249-09 (AK, MM).

Footnotes

Disclosure summary: All authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shufelt CL, Torbati T, Dutra E. Hypothalamic Amenorrhea and the Long-Term Health Consequences. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35(3):256–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon CM, Ackerman KE, Berga SL, Kaplan JR, Mastorakos G, Misra M, et al. Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(5):1413–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meczekalski B, Podfigurna-Stopa A, Warenik-Szymankiewicz A, Genazzani AR. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: current view on neuroendocrine aberrations. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008;24(1):4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faje AT, Fazeli PK, Miller KK, Katzman DK, Ebrahimi S, Lee H, et al. Fracture risk and areal bone mineral density in adolescent females with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(5):458–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cano Sokoloff N, Eguiguren ML, Wargo K, Ackerman KE, Baskaran C, Singhal V, et al. Bone parameters in relation to attitudes and feelings associated with disordered eating in oligo-amenorrheic athletes, eumenorrheic athletes, and nonathletes. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(5):522–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singhal V, Maffazioli GD, Cano Sokoloff N, Ackerman KE, Lee H, Gupta N, et al. Regional fat depots and their relationship to bone density and microarchitecture in young oligo-amenorrheic athletes. Bone. 2015;77:83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singhal V, Sanchita S, Malhotra S, Bose A, Flores LPT, Valera R, et al. Suboptimal bone microarchitecure in adolescent girls with obesity compared to normal-weight controls and girls with anorexia nervosa. Bone. 2019;122:246–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz AV, Sigurdsson S, Hue TF, Lang TF, Harris TB, Rosen CJ, et al. Vertebral bone marrow fat associated with lower trabecular BMD and prevalent vertebral fracture in older adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(6):2294–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheu Y, Cauley JA. The role of bone marrow and visceral fat on bone metabolism. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2011;9(2):67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Iorgi N, Rosol M, Mittelman SD, Gilsanz V. Reciprocal relation between marrow adiposity and the amount of bone in the axial and appendicular skeleton of young adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(6):2281–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao JW, Gao ZL, Mei H, Li YL, Wang Y. Differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells: the potential mechanism for estrogen-induced preferential osteoblast versus adipocyte differentiation. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341(6):460–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao B, Huang Q, Lin YS, Wei BY, Guo YS, Sun Z, et al. Dose-dependent effect of estrogen suppresses the osteo-adipogenic transdifferentiation of osteoblasts via canonical Wnt signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Resulaj M, Polineni S, Meenaghan E, Eddy K, Lee H, Fazeli PK. Transdermal Estrogen in Women With Anorexia Nervosa: An Exploratory Pilot Study. JBMR Plus. 2020;4(1):e10251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sul HS. Minireview: Pref-1: role in adipogenesis and mesenchymal cell fate. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23(11):1717–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fazeli PK, Bredella MA, Misra M, Meenaghan E, Rosen CJ, Clemmons DR, et al. Preadipocyte factor-1 is associated with marrow adiposity and bone mineral density in women with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(1):407–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fairfield H, Rosen CJ, Reagan MR. Connecting Bone and Fat: The Potential Role for Sclerostin. Curr Mol Biol Rep. 2017;3(2):114–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fairfield H, Falank C, Harris E, Demambro V, McDonald M, Pettitt JA, et al. The skeletal cell-derived molecule sclerostin drives bone marrow adipogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(2):1156–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singhal V, Bredella MA. Marrow adipose tissue imaging in humans. Bone. 2019;118:69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suchacki KJ, Cawthorn WP, Rosen CJ. Bone marrow adipose tissue: formation, function and regulation. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2016;28:50–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ecklund K, Vajapeyam S, Mulkern RV, Feldman HA, O’Donnell JM, DiVasta AD, et al. Bone marrow fat content in 70 adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa: Magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance spectroscopy assessment. Pediatr Radiol. 2017;47(8):952–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Syed FA, Oursler MJ, Hefferanm TE, Peterson JM, Riggs BL, Khosla S. Effects of estrogen therapy on bone marrow adipocytes in postmenopausal osteoporotic women. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(9):1323–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan BY, Gill KG, Rebsamen SL, Nguyen JC. MR Imaging of Pediatric Bone Marrow. Radiographics. 2016;36(6):1911–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalkwarf HJ, Zemel BS, Gilsanz V, Lappe JM, Horlick M, Oberfield S, et al. The bone mineral density in childhood study: bone mineral content and density according to age, sex, and race. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(6):2087–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fazeli PK, Horowitz MC, MacDougald OA, Scheller EL, Rodeheffer MS, Rosen CJ, et al. Marrow fat and bone--new perspectives. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(3):935–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elbaz A, Rivas D, Duque G. Effect of estrogens on bone marrow adipogenesis and Sirt1 in aging C57BL/6J mice. Biogerontology. 2009;10(6):747–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheller EL, Doucette CR, Learman BS, Cawthorn WP, Khandaker S, Schell B, et al. Region-specific variation in the properties of skeletal adipocytes reveals regulated and constitutive marrow adipose tissues. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singhal V, Bose A, Liang Y, Srivastava G, Goode S, Stanford FC, et al. Marrow adipose tissue in adolescent girls with obesity. Bone. 2019;129:115103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ackerman KE, Singhal V, Slattery M, Eddy KT, Bouxsein ML, Lee H, et al. Effects of Estrogen Replacement on Bone Geometry and Microarchitecture in Adolescent and Young Adult Oligoamenorrheic Athletes: A Randomized Trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2020;35(2):248–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khosla S, Oursler MJ, Monroe DG. Estrogen and the skeleton. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23(11):576–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faje AT, Fazeli PK, Katzman DK, Miller KK, Breggia A, Rosen CJ, et al. Sclerostin levels and bone turnover markers in adolescents with anorexia nervosa and healthy adolescent girls. Bone. 2012;51(3):474–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karampinos DC, Ruschke S, Dieckmeyer M, Diefenbach M, Franz D, Gersing AS, et al. Quantitative MRI and spectroscopy of bone marrow. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2018;47(2):332–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]