Abstract

Almost no research has examined factors that contribute to mortality risk among sexual minority women (SMW). This study capitalizes on a 21-year community-based longitudinal study of SMW to examine the association between sexual identity disclosure and mortality risk. Forty-nine SMW who were recruited in 2000–01 or 2010–12 (6.3% of the sample), were confirmed dead by 2019. The mean age at death was 56.5 years. We used Cox proportional hazard models to show that SMW who had disclosed their sexual identity to 100% of their immediate family members had a 70% reduction in the risk of mortality compared to SMW who disclosed to less than 33% of their immediate family, after adjusting for several sociodemographic and health variables. Our results suggest that facilitating acceptance of SMW and their ability to disclose their identity may be an important way to improve health and life expectancy among SMW.

Keywords: Sexual Minority, Women’s Health, Mortality, Minority Stress

Introduction

A large body of research has documented sexual orientation disparities in women across multiple health outcomes including mental health (Hughes et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2014; Marshal et al., 2011), health risk behaviors (Bowen et al., 2008; Hughes, 2011; McCabe et al., 2019), and physical health conditions (Caceres et al., 2019; Cochran et al., 2017; Veldhuis et al., 2019). Sexual orientation disparities in health are usually explained using minority stress theory, which argues that additional stressors specific to sexual minority populations are at the root of population-level health disparities (Meyer, 1995, 2003; Meyer & Frost, 2013). These additional stressors can include experiences of discrimination, at both the interpersonal and structural level, and may also include sexual-minority-specific individual-level mechanisms, such as identity disclosure, or the process of sharing a stigmatized identity with others.

To our knowledge, only three studies have examined sexual orientation disparities in mortality and just one has examined the link between identity disclosure and mortality risk. Cochran and colleagues (2016) used National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data and found that sexual minorities had greater all-cause mortality. Higher mortality was explained by health risk behaviors and health conditions; but the researchers did not examine sexual-minority-specific sources of stress. The second (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2020) used the General Social Survey and National Death Index to illustrate a dose-response relationship between structural stigma exposure and all-cause mortality for men and women who reported same-sex behavior in the past year. A final study examined mortality risk among HIV-infected men and found time to AIDS infection and mortality was more rapid among men who had not disclosed their gay identity (Cole et al. 1996) No research to date, however, has examined the relationship between sexual identity disclosure and mortality risk among sexual minority women (SMW).

Theories of sexual orientation development argue that identity disclosure is a key feature of developing a positive sense of self (Cass, 1979; Corrigan & Matthews, 2003; D’augelli et al., 1998; Mohr & Fassinger, 2003). Individuals who decide to disclose their minority identity to family members may do so for several reasons including the desire to reduce potential cognitive dissonance or stress related to concealing their identity, the desire to increase intimacy and trust with the person to whom they wish to disclose, and the desire for social support (Chaudoir and Fisher 2010). Identity disclosure has been linked to higher levels of self-esteem, sexual identity acceptance and integration (Bry et al., 2017; Floyd & Stein, 2002). Disclosure to family members may be particularly important for overall health, especially from a life course perspective. Studies have shown that facilitating healthy parent-child relationships and parent acceptance of their LGBTQ child is a powerful protective factor for LGBTQ youth; it is associated with greater self-esteem and social support, lower rates of substance abuse, and improved mental health (Ryan et al., 2010). Importantly, Disclosure Mediating Process theory posits that the disclosure process is a feedback loop through which a disclosure event can shape the likelihood of future disclosure to other individuals (Chaudoir and Fisher 2010). If the disclosure process yields social or psychological benefits, disclosure to other individuals is more likely. Alternatively, a negative reaction may hinder future disclosures and blunt the potential benefits of a disclosure event.

Indeed, the decision to disclose a stigmatized identity does not guarantee health benefits and, in fact, may increase exposure to stigma or discrimination and result in lower levels of social support (Huebner and Davis 2005; Ryan et al. 2009; Waldo 1999). Individuals who face challenges to identity disclosure and LGBTQ identity integration report more sexual risk taking and poorer psychological health (Rosario et al., 2006), as well as greater substance abuse, depression, and suicide attempts (Ryan et al. 2009). Studies of the workplace have shown that disclosure is positively associated with harassment (Waldo 1999). Gay and bisexual men who are “out” in their workplaces have elevated levels of cortisol (Huebner and Davis 2005), which may indicate increased cardiovascular risks. In countries with high levels of structural stigma, concealing one’s sexual minority identity is protective against lower levels of life satisfaction (Pachankis and Bränström 2018), insofar as it might serve to buffer discrimination. Thus, the decision to disclose a concealable stigmatized identity may in part be driven by external factors, such as whether a person feels that their social networks would be accepting and supportive of their sexual identity (Monk and Ogolsky 2019).

Increasingly, researchers have documented factors related to healthy aging among sexual minorities (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 2015; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 2019; Van Wagenen, Driskell, and Bradford 2013). No research to date, however, has examined the relationship between identity disclosure and mortality risk among SMW. This study uses data from the Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women Study to explore the relationship between sexual identity disclosure and all-cause mortality in a longitudinal, community-based sample of SMW.

Methods

Data.

The Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women (CHLEW) Study is a 21-year longitudinal study of 812 SMW (i.e., lesbian, bisexual, queer) who were recruited from the Chicagoland area in 2000–01 (original sample) or 2010–2012 (supplemental sample). Between 2018 and 2019, participants were re-contacted for either a second (supplemental sample) or a fourth (original sample) wave of data collection, at which point 50 participants were identified as having died. Forty-one deaths were confirmed using the national death registry and death certificates were obtained to confirm the respondent had died and their age at death. An additional nine deaths were confirmed by family members or spouses, including the date of death. Supplementary analyses show that results are robust to the exclusion of the self-reported deaths. The sample for this study excluded participants who identified as “mostly heterosexual” (n=31) as our primary independent variable was bisexual or gay/lesbian identity disclosure. An additional six participants were excluded who were missing data on key covariates, and therefore the analytic sample included 775 participants, 49 of whom died between recruitment and the follow-up in 2018–2019.

Measures.

Deaths were confirmed using the national death registry and death certificates, or spouse or other family when this information was unavailable. Age at the time of death or age in 2018–2019 for those still living was used as the time-to-event or censoring time, respectively, in survival models. Baseline race/ethnicity and sexual identity were used, but all other measures were taken from the last observed wave of data collection.

Identity disclosure was assessed using a composite score of the number of immediate family members that participants reported (i.e., mother, father, number of siblings), and the number to whom the participant has disclosed her sexual identity. The distribution of this score was skewed (see Supplemental Figure 1) with piling at percentages corresponding to fractions of family members (e.g. 33% [1/3], 50% [e.g. 2/4]). To facilitate interpretation, the variable was recoded as a categorical measure that captured whether participants had disclosed to <33% of their immediate family members (referent), between 33% and 99%, or 100% of their immediate family members. The score was also cut at alternative values and treated continuously to ensure robustness of the results.

We additionally adjusted for several other sociodemographic characteristics and health behaviors that have been associated with mortality in previous research including self-reported race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White [referent], non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Other); education (high school or less [referent], some college, college graduate); and income (<$20,000 [referent], ≥$20,000 & <$40,000, ≥$40,000 & <$75,000; ≥$75,000). We also included a measure of whether the participants were in a committed relationship (1=yes, 0=no) at their most recent interview. Because a supplemental sample was added in 2010–2012, and because these participants were more likely to be racial/ethnic minorities, bisexual-identified, and of lower-ES, we additionally included a binary variable that captured whether respondents were members of the new cohort (1=yes, 0=no).

Tobacco use was measured as a dichotomous variable that captured whether a participant said they currently smoked cigarettes (1=yes, 0=no) at their most recent interview. Hazardous drinking was derived from a composite index that captured four indicators of hazardous drinking: heavy episodic drinking; intoxication; adverse drinking consequences; and symptoms of potential alcohol dependence (Hughes et al., 2014; Riley et al., 2017). Hazardous drinking scores ranged from 0 to 4, with a score of four indicating affirmative responses to one or more questions related to each of the four hazardous drinking indicators.

Depressive symptoms were assessed using questions from the diagnostic criteria of the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (Robins et al., 1981). Questions asked respondents whether in the past year (Wave 1) or since last interview (follow-up surveys) there had been two or more weeks in which they had: felt sad or blue; lost their appetite; lost weight without trying; gained weight; had trouble sleeping; felt tired all the time; were moving all the time/couldn’t hold still; moved more slowly than usual; lost interest in sex; felt worthless; felt it was harder to think than usual. Responses were yes (1) or no (0). The scale ranged from 0 to 11 and had a Chronbach’s alpha of .83.

Statistical Approach.

We conducted bivariate tests to examine differences in sample characteristics by mortality status. Next, we used Cox proportional hazard models and multivariate model building to assess the relationship between identity disclosure and mortality. The dependent variable was a binary indicator of death prior to 2019 (1=death, 0=survival). Following Kom, Graubard, and Midthune (1997), we used age as the time-to-event rather than time-in-study in the hazard models (Allison, 2014), while specifying that participants contribute to the model beginning at the age at which they were first interviewed. Because there were no deaths in the “other” racial/ethnic group, models that included this variable utilized a Firth correction (Heinze and Schemper 2001). All p-values are derived from two-tailed tests. Lastly, we used life table information from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; 2017) to calculate the proportion of deaths expected in a general U.S. population of women with the same age distribution and length of follow-up as those in the CHLEW sample.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the total sample and by mortality status. Bivariate comparisons between participants who died and those still alive show that only 37% of deceased participants had disclosed their sexual identity to all (100%) of their immediate family members—compared to 54% of those still living. Bivariate comparisons also reveal differences in sexual identity by mortality status: among participants who had died, 82% identified as exclusively gay/lesbian, compared to 61% of those alive at follow-up. Not surprisingly, given that participants recruited as part of the supplemental sample were younger than the original cohort participants, they comprised just 18% of the sample that had died at follow-up compared to 45% of the sample that was still alive.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Total | Alive | Deceased | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=775 | N=726 | N=49 | ||

| %/M | %/M | %/M | ||

| Disclosure to Family (%) | ||||

| <33% | 8.77 | 7.99 | 20.41 | ** |

| ≥33% & <100% | 38.58 | 38.29 | 42.86 | |

| 100% | 52.65 | 53.72 | 36.73 | |

| Age/Age at Death (M) | 49.42 | 48.94 | 56.46 | ** |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White | 35.74 | 35.12 | 44.9 | |

| Black | 36 | 35.95 | 36.73 | |

| Latina | 24.65 | 25.07 | 18.37 | |

| Other | 3.61 | 3.86 | 0 | |

| Education (%) | ||||

| High School or Less | 22.06 | 22.04 | 22.45 | |

| Some College | 34.19 | 34.57 | 28.57 | |

| College Graduate | 43.74 | 43.39 | 48.98 | |

| Sexual Identity (%) | ||||

| Exclusively Lesbian/Gay | 62.19 | 60.88 | 81.63 | * |

| Mostly Lesbian/Gay | 21.29 | 22.04 | 10.2 | |

| Bisexual | 16.52 | 17.08 | 8.16 | |

| Income (%) | ||||

| <$20,000 | 28.3 | 27.86 | 34.78 | |

| ≥$20,000 & <$40,000 | 20.19 | 19.65 | 28.26 | |

| ≥$40,000 & <$75,000 | 26.24 | 26.69 | 19.57 | |

| ≥$75,000 | 25.27 | 25.81 | 17.39 | |

| New Cohort (%) | 43.1 | 44.77 | 18.37 | *** |

| In a relationship (%) | 61.94 | 62.67 | 51.02 | |

| Depressive symptoms (M) | 5.13 | 5.06 | 6.18 | * |

| Hazardous drinking (M) | 1.6 | 1.64 | 1.11 | * |

| Current Smoker (%) | 30.49 | 29.79 | 40.82 | |

Source: Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women Study Notes:

p<0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05

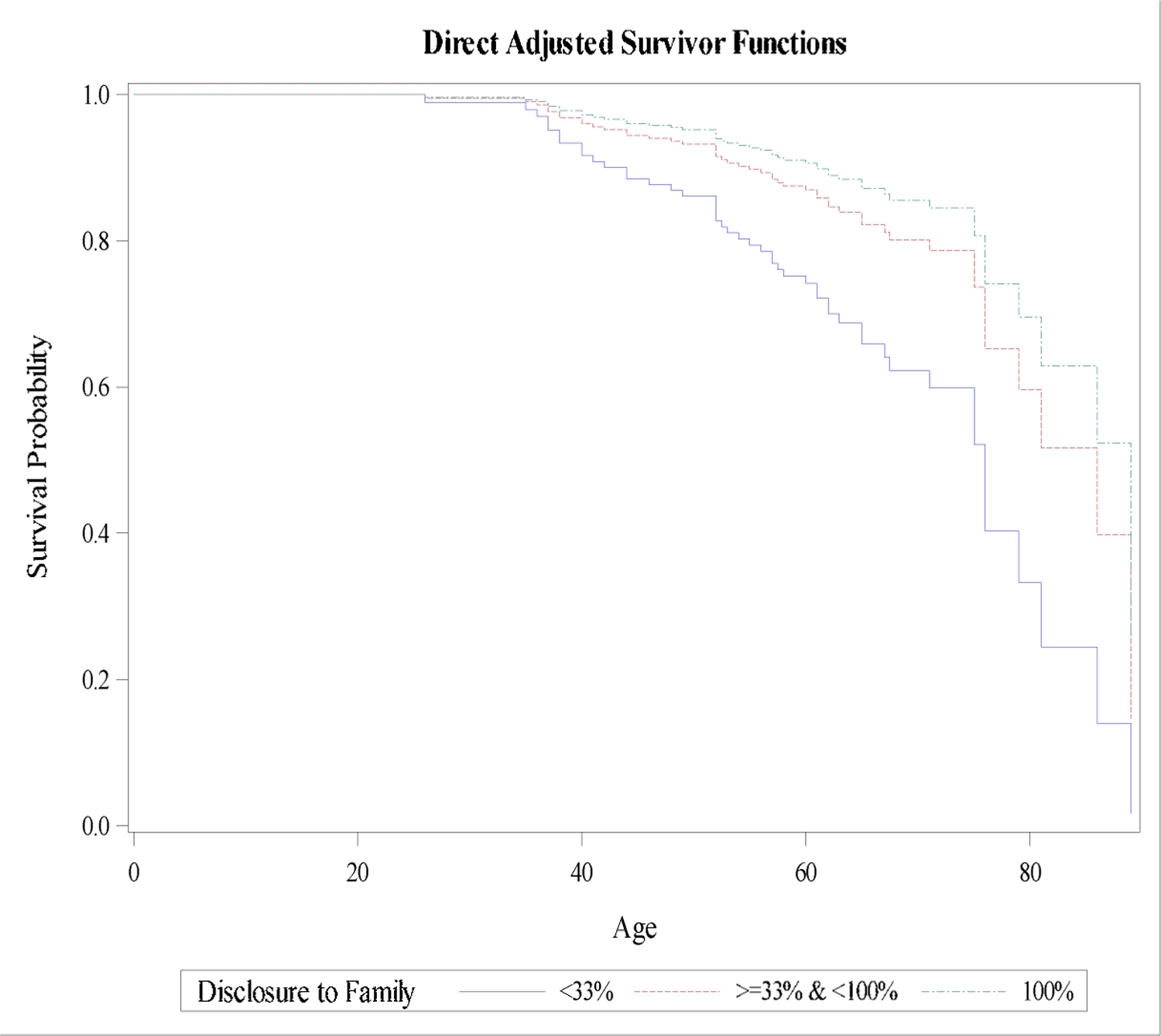

Table 2 presents results of the survival analyses. The proportional hazards assumption was checked for the full model, and the assumption held for all variables. Model 1 shows that compared to participants who had disclosed to less than 33% of their immediate family members, those who had disclosed to 100% of their family members had a lower risk of death at follow-up (HR = 0.33, p<.05). This relationship between identity disclosure and mortality remained statistically significant after adding sociodemographic characteristics in Model 2, and remained significant following the further addition of variables in Models 3–5. In the final model, including all covariates, SMW who had disclosed their sexual identity to all immediate family members had a 70% lower risk of death at follow-up than those who had disclosed to less than 33% of their immediate family members (p<.05). There also was a non-significant but notable difference across all models between those who had disclosed to ≥33% and <100% and those who had disclosed to <33% (all p<.10). Figure 1 presents the Kaplan-Meier survival curves stratified by disclosure categories.

Table 2.

Results from Hazard Models Predicting Mortality (n=775)

| Model 1 | Model 2a | Model 3a | Model 4a | Model 5a | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||||||

| Disclosure to Family (<33%) | |||||||||||||||

| ≥33% & <100% | 0.47 | (0.21, 1.03) | + | 0.48 | (0.21, 1.08) | + | 0.43 | (0.19, 1.01) | + | 0.46 | (0.20, 1.08) | + | 0.44 | (0.19, 1.06) | + |

| 100% | 0.33 | (0.14, 0.75) | * | 0.33 | (0.14, 0.80) | * | 0.31 | (0.13, 0.75) | * | 0.31 | (0.13, 0.75) | * | 0.30 | (0.12, 0.76) | * |

| Race/Ethnicity (White) | |||||||||||||||

| Black | 1.31 | (0.57, 3.01) | 1.40 | (0.63, 3.15) | 1.18 | (0.51, 2.76) | 1.35 | (0.59, 3.06) | |||||||

| Latina | 1.23 | (0.45, 3.32) | 1.16 | (0.44, 3.07) | 1.30 | (0.48, 3.50) | 1.25 | (0.47, 3.30) | |||||||

| Other | 0.38 | (0.02, 7.19) | 0.33 | (0.02, 6.32) | 0.36 | (0.02, 6.88) | 0.34 | (0.02, 6.48) | |||||||

| Education (High School or Less) | |||||||||||||||

| Some College | 0.83 | (0.35, 1.99) | 0.91 | (0.38, 2.18) | 1.08 | (0.44, 2.67) | 1.18 | (0.47, 2.93) | |||||||

| College Graduate | 0.86 | (0.35, 2.09) | 1.06 | (0.43, 2.57) | 1.18 | (0.46, 3.07) | 1.43 | (0.55, 3.72) | |||||||

| Sexual Identity (Exclusively Lesbian/Gay) | |||||||||||||||

| Mostly Lesbian/Gay | 0.34 | (0.12, 0.95) | * | 0.33 | (0.12, 0.92) | * | 0.37 | (0.13, 1.01) | + | 0.35 | (0.13, 0.98) | * | |||

| Bisexual | 0.69 | (0.17, 2.70) | 0.64 | (0.16, 2.56) | 0.92 | (0.23, 3.70) | 0.79 | (0.19, 3.27) | |||||||

| Income (<$20,000) | |||||||||||||||

| $20,000 – $39,999 | 0.94 | (0.43, 2.05) | 0.95 | (0.44, 2.07) | 1.12 | (0.51, 2.47) | 1.18 | (0.53, 2.61) | |||||||

| $40,000 – $74,999 | 0.43 | (0.18, 1.06) | + | 0.43 | (0.17, 1.07) | + | 0.46 | (0.18, 1.16) | + | 0.48 | (0.19, 1.22) | ||||

| $75,000 and up | 0.39 | (0.14, 1.07) | + | 0.46 | (0.16, 1.29) | 0.45 | (0.16, 1.24) | 0.60 | (0.20, 1.75) | ||||||

| New Cohort | 0.74 | (0.27, 2.05) | 0.75 | (0.27, 2.06) | 0.62 | (0.21, 1.85) | 0.64 | (0.22, 1.91) | |||||||

| In a relationship | 0.99 | (0.51, 1.89) | 0.83 | (0.43, 1.61) | |||||||||||

| Depressive symptoms | 1.14 | (1.03, 1.26) | * | 1.13 | (1.02, 1.25) | * | |||||||||

| Hazardous drinking | 0.99 | (0.78, 1.26) | 0.99 | (0.78, 1.25) | |||||||||||

| Current Smoker | 2.39 | (1.20, 4.76) | * | 2.29 | (1.14, 4.57) | * | |||||||||

Source: Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women Study

Notes: HR=Hazard Ratio; CI= Confidence Interval;

p<0.05

p<0.10

Models that include Race/Ethnicity use a Firth correction

Figure 1.

Survival Curves Stratiied by Disclosure Categories

Table 3 presents the percentage of actual (i.e., observed) deaths compared to the percentage of expected deaths in a U.S. female referent population, calculated using the most recently available life table information. In the CHLEW analytic sample 6.32% of participants died during the study period, but in a general U.S. population of women with the same age distribution and length of follow-up only 5.27% would be expected to die. Table 3 further stratifies the sample by original and supplemental/new cohort (i.e., recruited in 2000–01 or 2010–12), since the original sample was on average older and had a longer follow-up period than the supplemental sample, and original participants were therefore more likely to experience death during follow-up. Among all participants and among both enrollment cohorts, actual death proportions exceeded expected death proportions, although no differences were statistically significant.

Table 3.

Summary of Actual versus Expected Deaths

| Sample Size | Actual Deaths | Expected Deaths | Test of Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | % | p-value | ||

| All Subjects | 775 | 49 | 6.32 | 5.27 | 0.22 |

| Original Cohort | 441 | 40 | 9.07 | 8.04 | 0.48 |

| New Cohort | 333 | 9 | 2.69 | 1.62 | 0.18 |

Sources: Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women Study;

“Life Table for females: United States, 2017”(CDC)

Supplementary analyses (results available upon request) were conducted using disclosure as a continuous variable, as well as with other categorical cutoffs. The results are robust to different specifications. For example, the hazard ratio when disclosure was treated continuously as the proportion of family to which an individual disclosed was 0.31 (95% CI: 0.12, 0.80), indicating an association between greater proportion of immediate family members disclosed to and decreased mortality risk. In models where the reference category was zero family members, women who disclosed to 100% had a hazard ratio of 0.34 (95% CI 0.12, 0.98), providing further support for the robustness of our findings.

Discussion

This study used a novel, longitudinal data set to provide the first evidence of a relationship between sexual identity disclosure and mortality among SMW. This finding is in line with studies that have documented the benefits to sexual minority health of identity disclosure (Corrigan & Matthews, 2003; Rothman et al., 2012; Watson et al., 2019) and similar to findings of Cole and colleagues who found that identity disclosure among HIV positive men was protective (Cole et al., 1996). Our results show that even after controlling for mental health and health behaviors, among a population of SMW, disclosure to all immediate family members was associated with a 70% reduction in risk of mortality compared to disclosure to less than a third of family members.

Why would an individual disclose to one family member versus all others? It is important to remember that disclosure is a process that individuals engage in throughout the lifecourse; it is not a one-time event. Disclosure Mediating Process theory, which highlights that disclosure processes are a feedback loop through which past experiences inform future decisions (Chaudoir and Fisher 2010), can help understand the decision to disclose a stigmatized identity at different points to different family members. A negative disclosure event may mean that an individual does not go forward with disclosing to additional family members. Indeed, disclosing a stigmatized identity can be risky (Kosciw et al., 2015). However, many sexual minority individuals who disclose their identity to their families are met with acceptance (D’augelli et al., 1998; Rothman et al., 2012) and those in supportive environments are, in turn, more willing to disclose their identities to the people around them (Legate et al., 2012). Not disclosing one’s minority sexual identity, however, also carries risks (Pachankis 2007). Concealing a stigmatized identity may tax psychological resources via preoccupation with concealing the identity, as well as increase worry about discovery,and potential consequences of being “outed” (Pachankis 2007). The results presented here suggest that at least in terms of mortality, the benefits of disclosure may outweigh the risks.

Individuals who have positive experiences disclosing their identity to family members may accrue health benefits of disclosure through family acceptance, increased trust, and social support (Chaudoir and Fisher 2010). Social support is critical for healthy aging (Seeman et al. 2001) and lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) adults face unique challenges in the aging process (Van Wagenen et al. 2013). Other research has found that larger social network size and social support reduce the risk of poor health among older LGB adults (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 2013, 2015) and that identity disclosure is associated with larger social networks in older age (Erosheva et al. 2016) and better mental health among SMW (Pachankis et al., 2015). Close relationships with family members are associated with improvements in mental health, as well as lower likelihood of health-risk behaviors such as tobacco and alcohol use and unsafe sex (Armstrong et al., 2016; Kuper et al., 2018; McConnell et al., 2016; Watson et al., 2016). Moreover, sexual identity disclosure is associated with lower levels of internalized homophobia (Bry et al., 2017) and greater comfort with minority sexual orientation (Floyd & Stein, 2002), which may have long-term health benefits that translate into lower mortality risk. For example, older SMW are more likely than heterosexual women to report chronic conditions such as arthritis, asthma, heart attack, stroke, chronic pain (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 2017), as well as cognitive impairments (Hsieh, Liu, and Lai 2020). Identity disclosure may be important to healthy aging because as individuals get older the support of family members becomes even more important given that family members often facilitate medical care and health care decisions. Although older LGB adults often form kinship networks outside of their biological family, the results presented here suggest that disclosure to family members remains important and may be associated with long-term health benefits.

The relationship between sexual identity disclosure and mortality risk reduction may be especially meaningful if sexual minority populations experience greater all-cause mortality as reported by Cochran and colleagues (2016). Although we did not find statistically significant differences between actual and expected death proportions in the current study, more research is needed to examine whether all-cause mortality is higher among SMW relative to the general population, and if so whether sexual identity disclosure is protective. Findings by Hatzenbuehler and colleagues (2020) suggest that sexual minorities (operationalized as having a same-sex sexual partner in the past year) living in communities with high levels of anti-gay prejudice (i.e., high levels of structural stigma) have higher risk of mortality than those living in communities with low levels of prejudice. This highlights the importance of considering sociopolitical risk factors when addressing mortality risk. This concern holds true outside the realm of sexual minority research; for example, African American mortality rates have been shown to be significantly correlated with a state-level measure of political culture (Kunitz et al., 2010).

Sociopolitical factors that affect mortality in SMW are likely to be both geographically-varying (e.g., by community, by state) as we see in the examples above, and time-varying. Prior to federal marriage equality, research findings indicated that same-sex couples living in states with legal recognition of same-sex relationships reported higher levels of self-rated health relative to those in states with anti-gay constitutional amendments (Kail et al., 2015). Federal marriage equality largely buoyed the LGBTQ community; however, the subsequent 2016 election raised concerns about progress reversal that manifested through psychological and emotional distress (Veldhuis et al., 2018). In particular, many African American and Latina/x SMW perceived increased support (or at least not active opposition) of their relationships and sexual identity within their communities after marriage equality, while the political environment during and after the election was perceived as actively hostile (Riggle et al., 2020).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, data are from a non-probability sample, originally recruited from the Chicago Metropolitan area; thus, findings may not be generalizable to all SMW. Second, the relatively small number of deaths made it impossible to include cause of death in the analyses. Understanding cause of death would provide greater insights into the benefits of family disclosure. Third, for eight deaths in our analytic sample, we were unable to confirm the age at death through death certificates and instead relied on reports from family and/or spouses. Sensitivity analyses excluding these additional deaths, however, yielded similar results; in the equivalent of Model 5, the hazard ratio for those who disclosed to all family members was 0.43 (p=0.10). It is also possible that some of the respondents that study staff have been unable to locate may have died. Fourth, there may be several unmeasured confounding variables that influence mortality risk. Understanding the underlying causes of variation in mortality is useful for health policy and intervention design; however, risk factors can be difficult to measure directly, as observed measures are often products of traits or circumstances that are unobserved, partially observed, or complex and multidimensional. This sample was also restricted to participants who identified as cisgender women at recruitment. Understanding how mortality risk varies by gender identity is also important. Finally, we were unable to examine health care utilization. Mortality amenable to health care is a specifically defined composite measure of deaths before age 75 from complications of conditions that might be avoided by timely effective care and prevention (Nolte & McKee, 2004). Assessing this could be useful in future research as multiple studies have shown that SMW use preventive health care services at lower rates than heterosexual women (Cochran et al., 2001; Everett & Mollborn, 2014). Thus, a measure of health care utilization and —perhaps as importantly—a measure of disclosure in health care settings should be included in future studies that examine causes of mortality among SMW.

Implications

Despite growing calls for research on aging among SMW, few studies have focused on the relationship between minority stress and mortality risk, particularly among women. These data are the first to demonstrate an association between an important minority-stress specific measure—identity disclosure—and mortality risk among SMW. A new wave of research has begun to document the aging process and the unique challenges, as well as sources of resilience, that impact aging in LGBT populations (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2015; Ki et al. 2019). The results presented here tap into an understudied mechanism and outcome and suggest that among individuals who disclose their identity to their entire family, such disclosure may be protective against mortality risk. However, given the unique barriers SMW face, health care professionals should receive additional education on how social support during the aging process may differ among SMW, including the importance of incorporating “chosen family” members into caregiving plans (Erosheva et al. 2016; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 2018; Molinari and McSweeney-Feld 2017). Developing close and loving relationships with family members is critical for the healthy development of all people, including sexual minorities (Ryan et al., 2010; Snapp et al., 2015). Understanding in which contexts individuals are more likely to disclose their identity to all family members versus some or none, and the pathways through which disclosure improves as opposed to harms health, is an important next step in this work.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Greater identity disclosure to immediate family was associated with lower mortality risk.

LGBT acceptance in families may improve the health of sexual minority women.

Benefits of disclosure were highest among women who disclosed to all family members.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA013328-13, PI Hughes). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allison PD 2014. Event history and survival analysis: Regression for longitudinal event data (Vol. 46). SAGE publications. [Google Scholar]

- Arias E, Xu JQ, 2017. United States life tables. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 68 no 7. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_07-508.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong HL, Steiner RJ, Jayne PE, & Beltran O, 2016. Individual-level protective factors for sexual health outcomes among sexual minority youth: A systematic review of the literature. Sexual Health, 13(4), 311–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen DJ, Balsam KF, & Ender SR, 2008. A review of obesity issues in sexual minority women. Obesity, 16(2), 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bry LJ, Mustanski B, Garofalo R, & Burns MN (2017). Management of a concealable stigmatized identity: A qualitative study of concealment, disclosure, and role flexing among young, resilient sexual and gender minority individuals. J Homosexuality, 64(6), 745–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceres BA, Makarem N, Hickey KT, & Hughes TL, 2019. Cardiovascular disease disparities in sexual minority adults: An examination of the behavioral risk factor surveillance system (2014–2016). Am J Public Health, 33(4), 576–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass VC, 1979. Homosexuality identity formation: A theoretical model. J of Homosexuality, 4(3), 219–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control. Life Tables. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/life_tables.htm

- Chaudoir SR, & Fisher JD 2010. The disclosure processes model: Understanding disclosure decision making and postdisclosure outcomes among people living with a concealable stigmatized identity.” Psychological Bulletin 136(2):236–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Mays VM, Bowen D, Gage S, Bybee D, Roberts SJ, Goldstein RS, Robison A, Rankow EJ, & White J, 2001. Cancer-related risk indicators and preventive screening behaviors among lesbians and bisexual women. Am J Public Health 91(4), 591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Björkenstam C, & Mays VM, 2016. Sexual orientation and all-cause mortality among US adults aged 18 to 59 Years, 2001–2011. Am J Public Health, 106(5), 918–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Björkenstam C, & Mays VM, 2017. Sexual orientation differences in functional limitations, disability, and mental health services use: Results from the 2013–2014 National Health Interview Survey. J Consult Clin Psych, 85(12), 1111–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Kemeny ME, Taylor SE, Visscher BR, & Fahey JL 1996. Accelerated Course of human immunodeficiency virus infection in gay men who conceal their homosexual identity. Psychosomatic Med, 58(3), 219–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P, & Matthews A, 2003. Stigma and disclosure: Implications for coming out of the closet. J Mental Health 12(3), 235–248. [Google Scholar]

- D’augelli AR, Hershberger SL, & Pilkington NW, 1998. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: Disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. Am J Orthopsychiatry, 68(3), 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erosheva EA, Kim H-J, Emlet C, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI 2016. Social networks of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. Res Aging, 38(1), 98–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett BG, & Mollborn S, 2014. Examining sexual orientation disparities in unmet medical needs among men and women. Pop Res Policy Rev, (4), 553–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, & Stein TS, 2002. Sexual orientation identity formation among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Multiple patterns of milestone experiences. J Res Adolesc 12(2), 167–191. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Emlet CA, Kim H-J, Muraco A, Erosheva EA, Goldsen J, & Hoy-Ellis C,P 2013. The physical and mental health of lesbian, gay male, and bisexual (LGB) older adults: The role of key health indicators and risk and protective factors. Gerontologist, 53(4), 664–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Hyun-Jun K, Shiu C, Goldsen J, & Emlet CA 2015. Successful aging among LGBT older adults: Physical and mental health-related quality of life by age group. Gerontologist, 55(1), 154–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Hyun-Jun K, Chengshi S, & Bryan AE 2017. Chronic health conditions and key health indicators among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older US adults, 2013–2014.” Am J Pub Health, 107(8), 1332–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Jen S, Bryan AE & Goldsen J 2018. Cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and other dementias in the lives of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) older adults and their caregivers: Needs and competencies. J Appl Gerontol, 37(5), 545–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Jen S & Muraco A 2019. Iridescent life course: LGBTQ aging research and blueprint for the future: A systematic review.” Gerontology, 65(3), 253–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J, Jung H, & Goldsen J 2019. The evolution of aging with pride—National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study: Illuminating the iridescent life course of LGBTQ adults aged 80 years and older in the United States. Int J Aging Hum Dev, 88(4), 380–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Rutherford C, McKetta S, Prins SJ, & Keyes KM, 2020. Structural stigma and all-cause mortality among sexual minorities: Differences by sexual behavior? Soc Sci Med 244, 112463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinze G & Schemper M 2001. A solution to the problem of monotone likelihood in Cox regression. Biometrics, 57(1), 114–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner DM, & Davis MC 2005. Gay and bisexual men who disclose their sexual orientations in the workplace have higher workday levels of salivary cortisol and negative affect. Annals Behav Med, 30(3), 260–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh N, Hui L, & Wen-Hua L 2020. Elevated risk of cognitive impairment among older sexual minorities: Do health conditions, health behaviors, and social connections matter?” Gerontologist, 10.1093/geront/gnaa136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hughes T, 2011. Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among sexual minority women. Alc Treatment Quarterly 29(4), 403–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, Johnson TP, Steffen AD, Wilsnack SC, & Everett B, 2014, Lifetime victimization, hazardous drinking, and depression among heterosexual and sexual minority women. LGBT Health, 1(3), 192–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, Szalacha LA, & McNair R, 2010. Substance abuse and mental health disparities: Comparisons across sexual identity groups in a national sample of young Australian women. Soc Sci Med 71(4), 824–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kail BL, Acosta KL, & Wright ER, 2015. State-level marriage equality and the health of same-sex couples. Am J Pub Health 105(6), 1101–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kom EL, Graubard BI, & Midthune D 1997. Time-to-Event Analysis of Longitudinal Follow-Up of a Survey: Choice of the Time-Scale. Am J Epi, 145(1), 72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Palmer NA, & Kull RM, 2015. Reflecting Resiliency: Openness About Sexual Orientation and/or Gender Identity and Its Relationship to Well-Being and Educational Outcomes for LGBT Students. Am J Com Health, 55(1), 167–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunitz SJ, McKee M, & Nolte E, 2010. State political cultures and the mortality of African Americans and American Indians. Health Place 16(3), 558–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuper LE, Wright L, & Mustanski B, 2018. Gender identity development among transgender and gender nonconforming emerging adults: An intersectional approach. Int J Transgenderism, 19(4), 436–455. [Google Scholar]

- Legate N, Ryan RM, & Weinstein N, 2012. Is coming out always a “good thing”? Exploring the relations of autonomy support, outness, and wellness for lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Soc Psych Pers Sci 3(2), 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA, McGinley J, Thoma BC, Murray PJ, D’Augelli AR, & Brent DA, 2011. Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. J Adolesc Health, 49(2), 115–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Matthews AK, Lee JGL, West BT, Boyd CJ, & Arslanian-Engoren C, 2019. Sexual orientation discrimination and tobacco use disparities in the United States. Nic Tobac Res, 21(4), 523–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell EA, Birkett M, & Mustanski B, 2016. Families matter: Social support and mental health trajectories among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. J Adolesc Health 59(6), 674–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, 1995. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J Health Soc Behav, 36(1), 38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, 2003. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psych Bul 129(5), 674–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, & Frost DM, 2013. Minority stress and the health of sexual minorities. In Patterson CJ & D’Augelli AR (Eds.), Handbook of psychology and sexual orientation (p. 252–266). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr JJ & Fassinger RE, 2003. Self-acceptance and self-disclosure of sexual orientation in lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: An attachment perspective. J Couns Psych 50(4), 482–495. [Google Scholar]

- Molinari CA, & McSweeney-Feld MH 2017. At the intersection of ageism and heterosexism: Making the case to deliver culturally competent health care for LGTB older adults. J Health Admin Educ 34(3), 473–88. [Google Scholar]

- Monk JK, & Ogolsky BG 2019. Contextual relational uncertainty model: Understanding ambiguity in a changing sociopolitical context of marriage. J Fam Theory Rev, 11(2), 243–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nolte E, & McKee M, 2004. Measuring the health of nations: Analysis of mortality amenable to health care. J Epi Com Health, 58(4), 326–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Cochran SD, & Mays VM, 2015. The mental health of sexual minority adults in and out of the closet: A population-based study. J Consult Clin Psych 83(5), 890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE 2007. The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: A cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychol Bull, 133(2), 328–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE & Bränström R 2018. Hidden from happiness: Structural stigma, sexual orientation concealment, and life satisfaction across 28 countries. J Cons Clinic Psych, 86(5), 403–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggle EDB, Drabble LA, Matthews AK, Veldhuis CB, Nisi RA, & Hughes TL, 2020. First comes marriage, then comes the election: Macro-level event impacts on African American, Latina/x, and white sexual minority women. Sex Res Soc Policy 10.1007/s13178-020-00435-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Riley BB, Hughes TL, Wilsnack SC, Johnson TP, Benson P, & Aranda F, 2017. Validating a hazardous drinking index in a sample of sexual minority women: Reliability, validity, and predictive accuracy. Sub Use Misuse 52(1), 43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS. National Institute of Mental Health diagnostic interview schedule: Its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(4):381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, & Braun L, 2006. Sexual identity development among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: Consistency and change over time. J Sex Res 43(1), 46–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Sullivan M, Keyes S, & Boehmer U, 2012. Parents’ supportive reactions to sexual orientation disclosure associated with better health: Results from a population-based survey of LGB adults in Massachusetts. J Homosexuality 59(2), 186–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Toomey RB, Ryan C, & Diaz RM, 2014. Being out at school: The implications for school victimization and young adult adjustment. A J Orthopsychiatry, 84(6), 635–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Russell ST, Huebner D, Diaz R, & Sanchez J, 2010. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. J Child Adolesc Pysch Nursing 23(4), 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, & Sanchez J 2009. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics, 123(1), 346–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Lusignolo TM, Albert M & Berkman L 2001. Social relationships, social support, and patterns of cognitive aging in healthy, high-functioning older adults: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Health Psychol, 20(4), 243–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snapp SD, Watson RJ, Russell ST, Diaz RM, & Ryan C, 2015. Social support networks for LGBT young adults: Low cost strategies for positive adjustment. Fam Rel, 64(3), 420–430. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagenen A, Driskell J, & Bradford J 2013. “I’m still raring to go”: Successful aging among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. J Aging Studies, 27(1),1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis CB, Bruzzese J-M, Hughes TL, & George M (2019). Asthma status and risks among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States: A scoping review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immun 122(5), 535–536.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis CB, Drabble L, Riggle EDB, Wootton AR, & Hughes TL, 2018. “We won’t go back into the closet now without one hell of a fight”: Effects of the 2016 presidential election on sexual minority women’s and gender minorities’ stigma-related concerns. Sex Res Soc Policy, 15(1), 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Waldo CR 1999. Working in a majority context: A structural model of heterosexism as minority stress in the workplace. J Couns Psych, 46(2), 218–232. [Google Scholar]

- Watson RJ, Allen A, Pollitt AM, & Eaton LA, 2019. Risk and protective factors for sexual health outcomes among black bisexual men in the U.S.: Internalized heterosexism, sexual orientation disclosure, and religiosity. Arch Sex Behav, 48(1), 243–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson RJ, Grossman AH, & Russell ST, 2016. Sources of social support and mental health among LGB youth. Youth Society 51(1), 30–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Medlock MM, 2017. Health effects of dramatic societal events— ramifications of the recent presidential election. N England J Med, 376(23), 2295–2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1.