Abstract

Background:

One of the most difficult problems faced by health care professionals is experiencing verbal and physical abuse from patients and their family members. Some studies have shown that health care workers, especially nurses, are up to 16 times more likely to be subject to violence than other workers.

Aims:

The aim of this study was to analyze the relationship between exposure to violence, work ability and burnout.

Methods:

Data were collected through a questionnaire to investigate health care workers’ exposure to violence (Violent Incident Form), burnout (Maslach Burnout Inventory) and work ability (Work Ability Index). A sample of 300 nurses was obtained for the study.

Results:

A total of 36% of nurses indicated that they had been a victim of violence in the past 12 months. The data analysis highlighted highly significant differences in work ability, emotional exhaustion and depersonalization between health care workers who had been victims of violence and those who had not experienced violence. Finally, work ability was shown to have a mediating effect on emotional exhaustion (indirect effect: b = 2.7, BCa CI: 1.37–4.33) and depersonalization (indirect effect: b = 1.1, BCa CI: 0.48–1.87).

Discussion:

This study is one of the first to consider the mediation effect of work ability between workplace violence experienced and burnout in the healthcare sector; it reports the complexity and severity of the consequences of workplace violence in this sector.

Keywords: Workplace Violence, health care workers, burnout, work ability

Introduction

Hospitals have some of the highest incidences of workplace violence (5, 24). The Joint Program on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector (53) defines workplace violence as ‘Incidents where staff are abused, threatened or assaulted in circumstances related to their work, including commuting to and from work, involving an explicit or implicit challenge to their safety, well-being or health’ (p 7, 2003). This definition considers two forms of violence: physical and non-physical abuse (27). Physical abuse refers to the use of physical force against another person or persons, resulting in physical, sexual or psychological injury. This includes hitting, kicking, slapping, stabbing, shooting, pushing, scratching, biting, etc. The second is psychological violence, which concerns threats of physical violence against another person or people and can cause physical, psychological, moral or social damage. It includes verbal abuse, uncivilized behaviour, disrespect, a dismissive attitude, intimidation, bullying, harassment and threats (8, 9).

The University of Iowa Injury Prevention Research Center ranks workplace violence into four categories based on the relationship between the attacker and the organization in order to improve understanding of the phenomenon and organize targeted interventions. These categories are criminal intent (type I), client/customer-on-employee (type II), worker-on-worker (type III) and personal relationship (type IV) violence (46). Although health workers can be exposed to all four types of violence in their jobs, type II (customer/client) is the most frequent, since most threats and assaults come from patients (or their family members and/or friends), who become violent while workers (primarily nurses or physicians) are assisting them.

Health care workers are 16 times more likely to experience workplace violence than workers in other occupations (15). Itzhaki et al (28) found that almost the 90% of the health care worker population was exposed to violence. Studies have shown that nurses tend to be exposed to violence more often than physicians due to their close proximity to patients and their families (40, 43, 51). Nurses working in emergency, psychiatric and geriatric departments are at a particularly higher risk of suffering from workplace violent behaviour from patients, their family members or friends (8, 19, 24, 34, 43). Albeit to a lesser extent, the attackers can also be colleagues and superiors. A study by INAIL (Italian Workers Compensation Authority) showed that 57% of violence on health care workers in Italy is perpetrated by patients or their family members, while 13% is committed by colleagues and/or superiors (41).

Being exposed to workplace violence can have several negative effects on workers’ health, safety and productivity (35, 53). It can impact job satisfaction (58); influence turnover intention (49, 58) and job insecurity; and lead to a lack of professional responsibility, aggressive behaviour and fear when dealing with patients (2).

Several studies have focused on the direct relationship between exposure to violence and job burnout (10, 11, 16, 30, 32, 48, 52, 55, 56, 57). In 2019, the World Health Organization recognized burnout as a significant problem among health care professionals and included this syndrome in the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases as an occupational hazard (54). It is therefore necessary to study the peculiar conditions, including exposure to third party violence, that can enhance this specific form of psychological suffering in the health care sector.

While the effects of type II violence on workers’ health, safety, productivity and even burnout have been studied quite extensively, only a small number of studies have considered the relationship between exposure to violence and work ability (WA) (22, 47, 58), and the relationship between exposure to violence WA and burnout. In the 1980s, researchers at the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health developed the construct of WA and developed a generic tool to assess WA: the “Work Ability Index” (WAI). It considers the workers’ self-assessed work ability in relation to work requirements, health status and the worker resources (25). WA indicates the balance between work demands and personal resources that could decline with aging (13, 44). The study of work ability has become more relevant in light of demographic changes and the extension of the working life (26), especially in the healthcare sector, where workers are exposed to high physical and emotional job demands (7, 13, 21, 37, 42) and where the workforce is—especially in Italy—‘greying’ significantly (6, 12).

Few studies have considered the relationship between exposure to violence, WA and burnout. However, some recent studies have shown that burnout is a consequence of impaired WA (44, 50). In this direction, workers that do not perceive themselves as adequately skilled for their job (perhaps in consequence of aging), can develop burnout. More specifically, a study of Sottimano et al (44) showed a mediation effect of work ability between age and psychological exhaustion, and a study of Viotti et al (50) that WA positively predicts enthusiasm toward the job and negatively predicts exhaustion, clarifying the directionality of the relationship between work ability and burnout.

In light of the previous literature, the present study has the following objectives:

(a) analyse the impact of violence on (a1) burnout and (a2) work ability;

(b) analyse the relationship between experienced violence, work ability, and burnout among healthcare workers.

Methods

Data collection

The data were collected using a self-reported questionnaire distributed in two large hospitals in northern Italy that commissioned the project. The questionnaire was distributed to the whole nursing staff of the hospital. The participation of the workers was completely voluntary, and anonymity of the data collection was ensured by the research group at the Department of Psychology of University of Turin. The research conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki. No treatment, including medical treatment, invasive diagnostics or procedures causing psychological or social discomfort, was administered to the participants. Moreover, the contents of the questionnaires were previously approved by the public administration committee at the two hospitals.

Measures

The questionnaire contained scales aimed at evaluating exposure to violence, work ability and burnout. The Violent Incident Form (VIF) created by Arnetz (3) contains four items to identify the type and frequency of the violence experienced. The items are the following: ‘have you been exposed to violence’ (yes/no), ‘who showed aggression or violence toward you’ (patient/patient’s relatives/staff/others...), ‘type of violent incident’ (verbal aggression/threats/physical aggression), ‘results of violence’ (no consequences/mild consequences/severe consequences).

The Work Ability Index (WAI) by Tuomi et al (45) includes seven sections: (1) current work ability compared with lifetime best (score range: 1–10), (2) work ability in relation to mental and physical demands (score range: 2–10), (3) number of current diseases diagnosed by a physician (score range: 1–7), (4) estimated work impairment due to diseases (score range: 1–6), (5) sick leave during the past 12 months (score range: 1–5), (6) self-prognosis of work ability for the next two years (score range: 1–4 or 7) and (7) mental resources (score range: 1–4). The total score ranges from 7 to 49. Overall, Cronbach’s alpha for this inventory is α =.67.

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) (33, 36) contains 22 items divided into three subscales. The first subscale, emotional exhaustion, contains nine items. The score ranges from 0 to 54. An example of an item is ‘I feel emotionally exhausted from my job’. The second subscale, depersonalization, contains five items. The score ranges from 0 to 30. An example of an item is ‘I seem to be treating my patients as if they were objects’. The third subscale, personal accomplishment, contains eight items. The score ranges from 0 to 48. An example of an item is ‘I feel full of energy’. Each item is graded using a seven-point Likert scale of how often the participant experiences the specified attitudes and feelings in relation to aspects of their work (0 = never; 6 = every day). The Cronbach’s alpha for emotional exhaustion is α =.88; depersonalization α =.78; personal accomplishment α =.79.

Participants

A total of 300 nurses participated in the study (table 1), the response rate was 60%. The participants were 85.7% female (n = 251) and 14.3% male (n = 42). This proportion reflects the real data of the Italian context, where nursing jobs are mainly done by women (38). The average age was 44.4 years old. Most of the participants were nurses (n = 247; 82.3%), 38 were HSC (health social care) workers (12.7%) and 15 were obstetricians (5.0%).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

| Gender | N | % |

| Male Female |

42 251 |

14.3 85.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single Married Divorced Widow |

66 195 36 3 |

22.0 65.0 12.0 1.0 |

| Offspring | ||

| Yes No |

208 92 |

69.3 30.7 |

| Job | ||

| Nurses HSC workers Obstetrician |

247 38 15 |

82.3 12.7 5.0 |

| Night shifts | ||

| Yes No |

149 150 |

49.8 50.2 |

| Availability | ||

| Yes No |

154 144 |

51.7 48.3 |

Statistical Analysis

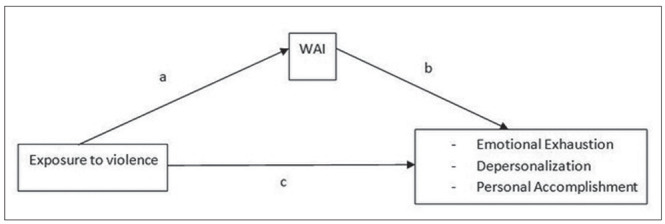

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 26 (Armonk, New York, USA). Preliminary analyses included descriptive statistics. We then tested the prevalence of episodes of violence in the two hospitals in northern Italy and the relationships between this exposure to violence, burnout and work ability. For this purpose, we used the t test and ANOVA. Then, we tested the mediating role of work ability between exposure to violence and (1) emotional exhaustion, (2) depersonalization and (3) personal accomplishment, controlling for age and gender (Figure 1) on the basis of PROCESS (SPSS 26) (23). The mediation analysis fit model 4, which is when the relationship between a predictor variable and an outcome variable can be explained by their relation to a third variable, the mediator variable (20).

Figure 1.

Schematic model of WAI as a mediator between exposure to violence and three dimensions of burnout (Andrew Hayes’s mediation model, Model 4)

Results

Exposure to violence

While 63.9% of participants declared that they had never been a victim of workplace violence, 23.8% had been a victim of workplace violence once or twice in the past 12 months, and 12.2% three or more times in the past 12 months. In 62.1% of cases, the violence was perpetrated by relatives or visitors of a patient, 37.9% by patients, 23.3% by colleagues and 14.6% by superiors. The sum of the percentages exceeded 100% because some workers had been victims of several attackers: 62.7% of the workers had suffered attacks perpetrated by a single type of attacker, while 32.4% by two different attackers and 4.9% by three attackers.

Verbal aggression represented 89.2% of the episodes of workplace violence, while threats accounted for 22.3% and physical aggression for 6.8%. Also in this case, the sum of the percentages exceeded 100% because some workers had been victims of several type of violence: 80.8% of workers had suffered a single type of violence (mainly verbal aggression), while 16.2% from two types of violence and 3% from three types of violence.

Fortunately, most of the participants (80.4%) said they experienced no repercussions following the incidence of violence, while 19.6% had mild health consequences (Table 2).

Table 2.

Data about exposure to violence

| Experiencing workplace violence | N | % |

| Yes No |

106 188 |

36.1 63.9 |

| Source of workplace violence incidence | ||

| Patients Families/Friends of patients Coworkers Superiors |

39 64 24 15 |

37.9 62.1 23.3 14.6 |

| Type of violence | ||

| Verbal aggression Threats Physical aggression |

91 23 7 |

89.2 22.3 6.8 |

| Consequences of violence | ||

| No consequence Mild consequences |

86 19 |

81.9 18.1 |

Considering the socio-demographic characteristics, women and men were equally exposed to violence (35.9% of women and 35.9% of men were exposed to violence). The average age of the participants did not differ significantly between those who had (mean = 44.6 years) and had not (mean = 44.4 years) experienced violence.

Considering professional qualifications, the workers most exposed to violence were nurses (37.4%), followed by HSC workers (33.3%) and midwives (20.0%).

Exposure to violence and differences in work ability and burnout

Considering exposure to violence as a dichotomous variable, 63.9% of participants had never been a victim of violence, and 36.1% had been in the past 12 months. Considering these two groups, we tested the differences in their work ability and burnout, with the latter defined by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and personal accomplishment.

The results of the t-test showed significant differences in terms of work ability, emotional exhaustion and depersonalization between health care workers who had been victims of workplace violence and those who had not (Table 3). More specifically, the WAI score was higher among workers who had not experienced workplace violence compared to those who had.

Table 3.

Work ability, emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment in relation to exposure to the violence

| No episodes of violence | 1 or more episodes of violence in the last 12 months | T test | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | p | |

| Work Ability Index | 39.5 | 4.9 | 35.8 | 6.0 | 5.28 | .000 |

| Emotional Exhaustion | 15.6 | 10.0 | 21.6 | 11.9 | -4.22 | .000 |

| Depersonalization | 4.7 | 4.9 | 7.2 | 7.0 | -3.12 | .002 |

| Personal accomplishment | 33.5 | 8.5 | 32.7 | 7.6 | 0.75 | .455 |

Similarly, workers who had experienced workplace violence showed higher levels of emotional exhaustion) and depersonalization. However, the two groups did not differ significantly with respect to personal accomplishment. Levels of personal accomplishment were higher among those who had not been victims of violence, but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 3).

Relationship between exposure to violence, work ability, and burnout among health workers

To evaluate the relationship between exposure to violence, work ability and burnout, we conducted the mediation analysis assuming the existence of a mediating effect of work ability between exposure to violence (dichotomized variable, where 1 = has been a victim of violence and 0 = has not been victim of violence) and burnout. Models (Figure 1) were controlled for age.

Scores for work ability and depersonalization can vary between age groups. Younger workers showed significantly higher WAI scores (F = 10.02, p = .000) and depersonalization (F = 3.41, p = .018) than older workers. Thus, age was correlated with work ability and depersonalization (Table 4), indicating that age could act as a confound in the mediation analyses.

Table 4.

Bivariate correlations among age, work ability and burnout

| Age | Work ability | Emotional exhaustion | Depersonalization | |

| Work ability | -.362** | |||

| Emotional exhaustion | .006 | -,.384** | ||

| Depersonalization | -.141* | -.250** | .557** | |

| Personal accomplishment | .029 | .141* | -.228** | -.326** |

The first model tested (Figure 1) presents exposure to violence as the independent variable (X), work ability as the mediator variable (M) and depersonalization as the dependent variable (Y). The results of the mediation analysis for work ability as a mediator between exposure to violence and emotional exhaustion showed that the total effect of exposure to violence on emotional exhaustion was significant. The significant coefficients of path a and path b indicated negative associations between the exposure to violence and work ability (path a) and between work ability and emotional exhaustion (path b). Also, the direct effect of exposure to violence on emotional exhaustion was significant (path c). Finally, the indirect relationship between exposure to violence and emotional exhaustion through WAI was statistically significant (Table 5).

Table 5.

Mediation analyses: WAI mediates the relationship between exposition to violence and burnout

| Variable | Total effect | Path c and b | Path a | Indirect effect | ||||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Outcome: Emotional exhaustion | ||||||||||

| Violence | 7.11** | 1.39 | 4.31* | 1.40 | - | - | 2.80 | 0.75 | 1.52 | 4.45 |

| WAI | - | - | -0.73** | 0.13 | -3.84** | 0.66 | ||||

| R2 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.23 | |||||||

| F | 13.07 | 20.83 | 37.87 | |||||||

| Outcome: Depersonalization | ||||||||||

| Violence | 3.01** | 0.75 | 1.865* | 0.77 | - | - | 1.15 | 0.37 | 0.50 | 1.95 |

| WAI | - | - | -0.29** | 0.07 | -3.91** | 0.64 | ||||

| R2 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.25 | |||||||

| F | 10.74 | 13.17 | 42.09 | |||||||

| Outcome: Personal Accomplishment | ||||||||||

| Violence | -1.11 | 1.13 | -0.18 | 1.19 | - | - | -0.92 | 0.42 | -1.77 | 0.11 |

| WAI | - | - | 0.24* | 0.11 | -3.81** | 0.66 | ||||

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.23 | |||||||

| F | 0.67 | 2.10 | 36.88 | |||||||

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001

The second model tested (Figure 1) presents exposure to violence as the independent variable (X), work ability as the mediator variable (M) and depersonalization as the dependent variable (Y). The results of the mediation analysis for WA as a mediator between exposure to violence and depersonalization showed that the total effect of exposure to violence on depersonalization was significant. The significant coefficients of path a and path b indicated negative associations of exposure to violence with WA (path a) and negative associations of WA with depersonalization (path b). Further, the direct effect of exposure to violence on depersonalization was significant (path c). Finally, the indirect effect between exposure to violence and depersonalization through WA was statistically significant (Table 5).

The third model tested (Figure 1) considered exposure to violence as an independent variable (X), WAI as a mediator variable (M), and personal accomplishment as a dependent variable (Y). However, the results of the mediation analysis for work ability as a mediator between exposure to violence and personal accomplishment were not significant (Table 5).

Discussion

The prevalence of episodes of violence perpetrated within the two hospital settings was quite high, exceeding 30% of the health care workers surveyed. Data regarding the prevalence and type of violence were in line with previous studies: the main type of violence experienced by our sample was type II (perpetrated by patients and their relatives) (1, 18, 19, 29, 34, 43). Moreover, verbal attacks prevailed over other forms of violence, similar to other recent studies conducted in Italy (39, 43) and abroad (1, 17, 18, 28, 29, 31).

Burnout (particularly the two sub-dimensions of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization) was significantly and positively associated with workplace violence, in line with previous studies (10, 11, 16, 30, 32, 52, 56, 57).

As expected, we found also a correlation between workplace violence and work ability, as previously indicated in the few studies that investigated this relationship (22, 47, 51).

Moreover, the mediating effect of work ability between exposure to violence and burnout emerged, specifically in relation to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. While levels of personal accomplishment were higher among those who were not victims of violence, the difference was not statistically significant and thus not mediated by work ability. Our data confirm a role of mediator of WAI, in line with the study of Sottimano et al (44) that showed a mediation effect of work ability between age and emotional exhaustion. Furthermore, our data confirm the results emerged in study of Viotti et al (50) that indicated that work ability positively predicts enthusiasm toward the job and negatively predicts emotional exhaustion, clarifying the directionality of the association between work ability and burnout. In this perspective, exposure to the violence could undermine the perception of work ability of hospital staff and consequently expose to burnout. Being exposed to workplace violence can be interpreted, coherently with other studies (48), as an increase in job demands that primarily affects the reduction of perceived work ability and, subsequently, enhances emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, which are the two core dimensions of burnout that are mainly related to the contextual factors of the job.

This study was not without limitations. First, the study used a cross-sectional design and self-reported measures. Future studies should consider objective data related to experienced violence (such as formal complaints registered by hospital management) and possibly other health assessments as conducted by occupational physicians. Moreover, a wider sample should be considered so as to deepen the age–work ability–burnout relationship and to identify burnout protection factors that may be linked to the sustainability of work of older nurses. Finally, future research should study the differences between nurses from wards with different levels of expected violence. As underlined by Arnetz et al (4), effective interventions aimed at preventing violence need to be data driven and unit based.

Despite these limitations, this study is the first (to our knowledge) to examine the mediating effect of work ability between workplace violence and burnout. We reported on the complexity and severity of the consequences of verbal and physical assault. Measures need to be introduced to support the performance of health workers (14), to increase both the security and safety of health care professionals and to preserve their work ability throughout their working lives.

Finally, the current pandemic situation must be taken into consideration. The data for this study were collected before the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of this study are rather worrying because they highlight and confirm an alarming situation. The relationship between work ability, burnout and health are not fully known. Until a few months ago, the health care workers being lauded as ‘heroes’ were victims of uncivilized aggression, including real physical violence, in the workplace. It is possible to imagine that in the coming months, burnout levels may increase while work ability is compromised due to the quality and quantity of the pandemic workload. It is unclear if the current situation will lead to a reduction in the instances of violence against health care workers due to their greater perceived social value.

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported by the authors

References

- 1.Al-Azzam M, AL-Sagarat AY, Tawalbeh L, Poedel RJ. Mental health nurses’ perspective of workplace violence in Jordanian mental health hospitals. Perspect Psychiatr C. 2017;54:477–487. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12250. DOI: 10.1111/ppc.12250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Shiyab AA, Ababneh RI. Consequences of workplace violence behaviors in Jordanian public hospitals. Empl Relat. 2018;40(3):515–528. DOI: 10.1108/ER-02-2017-0043. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnetz JE. The Violent Incident Form (VIF): A practical instrument for the registration of violent incidents in the health care workplace. Work and Stress. 1998;12:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnetz JE, Hamblin L, Russel J, et al. Preventing Patient-to-Worker Violence in Hospitals: Outcome of a Randomized Controlled Intervention. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59:18–27. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000909. DOI: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azami M, Moslemirad M, MektaKooshali MH, et al. Workplace Violence Against Iranian Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Violence Vict. 2018;33(6):1148–1175. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.33.6.1148. DOI: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-17-00079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balducci C, Fraccaroli F. Stress lavoro-correlato: Questioni aperte e direzioni future (Work-related stress: Open issues and future directions) G Ital di Psicol. 2019;46:39–65. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camerino D, Conway PM, Van der Heijden BIJM, et al. Low-perceived work ability, ageing and intention to leave nursing: a comparison among 10 European countries. JAN 2006;56:542–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04046.x. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannavò M, Fusaro N, Colaiuda F, et al. Studio preliminare sulla presenza e la rilevanza della violenza nei confronti del personale sanitario dell’emergenza. Clin ter. 2017;168:99–112. DOI: 107417/CT.2017.1990. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cashmore AW, Indig D, Hampton SE, et al. Workplace violence in a large correctional health service in New South Wales, Australia: a retrospective review of incident management records. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen S, Lin S, Ruan Q, et al. Workplace violence and its effect on burnout and turnover attempt among Chinese medical staff. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2016;71:330–337. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2015.1128874. DOI: 10.1080/19338244.2015.1128874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi SH, Lee H. Workplace violence against nurses in Korea and its impact on professional quality of life and turnover intention. Nurs Manag. 2017;25:508–518. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12488. DOI:10.1111/jonm.12488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. CIIP, Consulta interassociativa italiana per la prevenzione (2017). Libro d’argento Ciip sull’invecchiamento al lavoro. Disponibile online all’indirizzo: https://www.ciip-consulta.it/index.php?option=com_phocadownload&view=file&id=1:aging-ebook&Itemid=609. (ultimo accesso 20/05/2020) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costa G, Sartori S, Bertoldo B, et al. Work ability in health care workers. Int. Congr. Ser. 2005;1280:264–269. [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Alterio N, Fantinelli S, Galanti T, Cortini M. The mediator role of the job related stress in the relation between learning climate and job performance. Evidences from the health sector. Recenti Prog Med. 2019;110:251–254. doi: 10.1701/3163.31448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott P. Violence in health care: What nurse managers need to know. Nurs Manage. 1997;28:38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erdur B, Ergin A, Yuksel A, et al. Assessment of the relation of violence and burnout among physicians working in the emergency departments in Turkey. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2015;21:175–181. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2015.91298. DOI: 10.5505/tjtes.2015.91298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esmaeilpour M, Salsali M, Ahmadi F. Workplace violence against Iranian nurses working in emergency departments. Int Nurs Rev. 2011;58:130–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2010.00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fafliora E, Bampalis VG, Zarlas G, et al. Workplace violence against nurses in three different Greek healthcare settings. Work. 2016;53:551–560. doi: 10.3233/WOR-152225. DOI: 10.3233/WOR-152225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferri P, Reggiani F, Di Lorenzo R. I comportamenti aggressivi nei confronti dello staff infermieristico in tre differenti aree sanitarie. Professioni Infermieristiche. 2011;64:143–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics. 4th edition. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer FM, Da Silva Borges FN, Rotenberg L, et al. Work Ability of Health Care Shift Workers: What Matters? Chronobiol Int. 2006;23:1165–79. doi: 10.1080/07420520601065083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer FM, Martinez MC. Individual features, working conditions and work injuries are associated with work ability among nursing professionals. Work. 2013;45:509–517. doi: 10.3233/WOR-131637. DOI: 10.3233/WOR-131637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. A regression based approach (2nd edition) London: The Guilford Press NY; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hegney D, Tuckett A, Parker D, Eley RM. Workplace violence: Differences in perceptions of nursing work between those exposed and those not exposed: A cross-sector analysis. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16:188–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01829.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ilmarinen J, Tuomi K, Seitsamo J. New dimensions of work ability. Int.Congr Ser. 2005;1280:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ilmarinen V, Ilmarinen J, Huuhtanen P, et al. Examining the factorial structure, measurement invariance and convergent and discriminant validity of a novel self-report measure of work ability: work ability – personal radar. Ergonomics. 2015;58:1445–1460. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2015.1005167. DOI: 10.1080/00140139.2015.1005167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geneva: International Labour Office; 2002. International Labour Office: International Council of Nurses, World Health Organization, Public Services International: Framework Guidelines for Addressing Workplace Violence in the Health Sector. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Itzhaki M, Bluvstein I, Bortz AP, et al. Mental health nurse’s exposure to Workplace Violence leads to Job stress, Which leads to reduced Professional Quality of life. Front Psychol. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00059. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeong IY, Kim JS. The relationship between intention to leave the hospital and coping methods of emergency nurses after workplace violence. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27:1692–1701. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14228. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.14228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim H, Kim JS, Choe K, et al. Mediating effects of workplace violence on the relationships between emotional labour and burnout among clinical nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:2331–2339. doi: 10.1111/jan.13731. DOI: 10.1111/jan.13731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kvas A, Seljak J. Sources of workplace violence against nurses. Work. 2015;52:177–184. doi: 10.3233/WOR-152040. DOI: 10.3233/WOR-152040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laeeque SH, Bilal A, Babar S, et al. How Patient-Perpetrated Workplace Violence Leads to Turnover Intention Among Nurses: The Mediating Mechanism of Occupational Stress and Burnout. J Aggress Maltreatment Trauma. 2018;27(1):96–118. DOI: 10.1080/10926771.2017.1410751. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loera B, Converso D, Viotti S. Evaluating the Psychometric Properties of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) Among Italian Nurses: How Many Factors Must a Researcher Consider? PLoS One. 2014; 12;9(12):e114987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114987. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu L, Lok KI, Zhang L, et al. A Prevalence of verbal and physical workplace violence against nurses in psychiatric hospitals in China. Arch Psychiat Nurs. 2019;33:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2019.07.002. DOI: 10.1016/j.apnu.2019.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magnavita N. Workplace violence and occupational stress in healthcare workers: A chicken-and-egg situation-results of a 6-year follow-up study. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2014;46:366–376. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maslach J, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory. 3th edition. Consulting Psychology Press: Palo Alto CA; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monteiro I, de Santana P, Chillidab M, Contrera L. Work ability among nursing personnel in public hospitals and health centers in Campinas – Brazil. Work. 2012;41:316–319. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-0176-316. DOI: 10.3233/WOR-2012-0176-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. OMS, https://www.nurse24.it/images/allegati/rapporto-oms-infermieri.pdf. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramacciati N, Ceccagnoli A, Addey B. Violence towards nurses in the Triage Area. Scenario. 2013;30:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramacciati N, Ceccagnoli A, Addey B, Rasero L. Violence towards Emergency Nurses. The Italian National Survey 2016: A qualitative study. Int J Nurs. 2018;81:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.01.017. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salvati A. Dati INAIL. 2018:11. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soric M, Golubic R, Milosevic M, et al. Shift work, quality of life and work ability among Croatian hospital nurses. Coll. Antropol. 2013;37(2):379–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sossai D, Molina FS, Amore M, et al. Analisi degli episodi di violenza in un grande ospedale Italiano. Med Lav. 2017;108(5):377–387. doi: 10.23749/mdl.v108i5.6005. DOI: 10.23749/mdl.v108i5.6005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sottimano I, Guidetti G, Converso D, Viotti S. We cannot be “forever young,” but our children are: A multilevel intervention to sustain nursery school teachers’ resources and well-being during their long work life cycle. Plos One. 2018;13(11):e0206627. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206627. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0206627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tuomi K, Ilmarinen J, Jahkola A, et al. Work Ability Index. 2nd revised edn. Helsinki: Finnish Institute of Occupational Health; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 46.UIIPRC Workplace violence. A report to the nation. University of Iowa: Iowa City, IA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uronen L, Heimonen J, Puukka P, et al. Health check documentation of psychosocial factors using the WA. Occup Med. 2017;67:151–154. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqw117. DOI: 10.1093/occmed/kqw117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Viotti S, Gilardi S, Guglielmetti C, Converso D. Verbal Aggression From Care Recipients as a Risk Factor Among Nursing Staff: A Study on Burnout in the JD-R Model Perspective. Biomed Res Int. 2015:215–267. doi: 10.1155/2015/215267. DOI: 10.1155/2015/215267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Viotti S, Guidetti G, Converso D. Nurses Between the Hammer and the Anvil: Analyzing the Role of the Workplace Prevention Climate in Reducing Internal and External Violence. Violence Vic. 2019;1(34):363–375. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-17-00035. DOI: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-17-00035.i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Viotti S, Guidetti G, Sottimano I, Martini M, Converso D. Work ability and burnout: What comes first? A two-wave, cross-lagged study among early childhood educators. Safety Science. 2019;118:898–906. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang PX, Wang MZ, Hu GX, Wang ZM. Study on the relationship between workplace violence and work ability among health care professionals in Shangqiu City. Journal of Hygiene Research. 2006;35:472–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waschgler K, Ruiz-Hernànde JA, Llor-Esteban B, Garcìa-Izquierdo M. Patient’s aggressive behaviors towards nurses: Development and psychometric properties of the hospital aggressive behavior scale-users. J Adv Nurs. 2012;69:1418–1427. doi: 10.1111/jan.12016. DOI:10.1111/jan.12016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.WHO (2003) Joint Programme on workplace violence in the health sector. Geneva: Workplace violence in the health sector country case studies research instruments. Survey questionnaire (ultimo accesso 20/05/2020) [Google Scholar]

- 54.WHO (2019) Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. Disponibile on line all’indirizzo https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/burn-out/en. /, (ultimo accesso 20/05/2020) [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang BX, Stone TE, Petrini MA, Morris DL. Incidence, Type, Related Factors, and Effect of Workplace Violence on Mental Health Nurses: A Cross-sectional Survey. Arch Psychiat Nurs. 2018;32:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.09.013. DOI: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoon HS, Sok S. Experiences of violence, burnout and job satisfaction in Korean nurses in the emergency medical centre setting. Int J Nurs Pract. 2016;22:596–604. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12479. DOI: 10.1111/ijn.12479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zafar W, Khan UR, Siddiqui SA, et al. Workplace violence and self-reported psychological health: Coping with post-traumatic stress, mental distress and burn out among physicians working in the emergency departments compared to other specialties in Pakistan. Int. J. Emerg Med. 2015;50:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.02.049. DOI: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao SH, Shi Y, Sun ZN, et al. Impact of workplace violence against nurses’ thriving at work, job satisfaction and turnover intention: A cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27:2620–2632. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14311. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.14311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]