Abstract

Background and aim of the work:

Pain is one of the most common symptoms in children who access the Pediatric Emergency Room (PER). However, many studies show that it is poorly evaluated and treated during the triage phase and that in many cases algometric scales aren’t used for its evaluation. Faced with this, the Piacenza PER (Italy) implemented the Pain in Pediatric Emergency Room (PIPER) recommendations for the assessment and management of pain from the 1st July 2017. The aim of this study was to detect the possible differences in the trend of the outcomes for the detection and treatment of pain in July-October 2016, 2017, 2018.

Methods:

A retrospective observational study was chosen. 811 discharge letters of extremity traumatized children aged 0-9 years were analyzed, of which 309 referred to the 2016 quarter, 243 to the 2017 quarter and 259 to the 2018 quarter.

Results:

In 2016, the pain of 12 patients was assessed out of a total of 309, in 2017 of 227 out of 243 and in 2018 of 245 out of 259. The Chi Square test about assessed and not assessed pain, gave statistically significant value (p = 1.36E-98), comparing 2016vs2017 and gave not significant value comparing 2017vs2018 (p = 0.58). 4 patients were treated during the triage phase in 2016, 68 in 2017 and 70 in 2018.

Conclusions:

Recommendations introduction has increased the frequency of pain algometric measurements during the triage phase by leading to an improvement in the nursing care outcomes in terms of pediatric pain management. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: pain, Pediatric Emergency Room, triage, extremity trauma, nurses, children, PIPER

Background

Pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of damage (1). It is every patient’s right that pain is evaluated and managed (2).

In the pediatric field, pain is a frequent symptom: it is estimated that 80% of children hospitalized in pediatrics present pain and that 60-70% of visits to the Pediatric Emergency Room (PER) is due to this symptom (3-5).

In Italy, the State-Regions Agreement with the issue of guidelines to create a pain-free hospital, approved on 24 May 2001, which considers the analgesic needs of the newborn and the child, underlines the importance of using tools suitable for the different ages of patients (6). Furthermore, in the 2006-2008 National Health Plan, point 3.9 “The definition of national guidelines on the treatment of pain in children” is proposed in which the need for analgesia in the newborn /child is considered, considering the peculiarities and differences of the child with respect to adult (7). Regarding pediatric analgesia, since January 2009, the Commission on Pain Therapy and Palliative Care of the Ministry of Health has defined an organizational and assistance project for the pediatric patient. The child care proposal is divided into two levels: a specialist in pain management aimed at very complex situations, both at a diagnostic and therapeutic level, and a more general one based on medical and nursing training in the assessment and management of child pain (8).

Despite the indications given by international institutions for pain control, several studies show that the symptom is often poorly evaluated and treated in children who enter the Emergency and Acceptance Departments (EAD) (9-11). In particular, analgesia in pediatric patients continues to be used much less than in adults with the same pathology, especially with regard to fractures (11, 12). The analgesia of children with long bone fractures is often delayed and inadequate and the use of evaluation scales without the application of a drug protocol is not effective in increasing pain treatment (13).

In Italy, a study conducted by the “Pain in Pediatric Emergency Room (PIPER)” group, highlighted that: (i) only in 26% of hospitals, pain is regularly assessed both in triage and in the PER; (ii) about one third do not use algometric scales for pain assessment; (iii) in 21% the detection is not documented and (iv) in 47.4% of cases there are no protocols for symptom treatment in children. Furthermore, in 37% of the hospitals investigated, pain assessment is not carried out either in triage or in PER (14).

According to the study, the administration of painkillers in Emergency Department (ED) occurs only in 4% of cases in triage, in 24% of cases in ED, in 3% of cases in Brief Intensive Observation and in 0.4% of cases in a moment not known (14). These results improved significantly in the centers where the PIPER recommendations were applied (15).

For the PIPER group, the correct and early management of pain is fundamental, already in the triage phase, using measurement tools and validated protocols that make it possible for nurses to administer specific analgesic drugs (14).

The “Piper Weekend” study (16), conducted in 2015, showed that children and parents who have had access to EADs were satisfied with pain management and symptom attention given by professionals, but that relief was still inadequate. In fact, about half of the children with pain did not receive any type of painkiller. showing that pain management in the pediatric patient remains a goal not yet achieved (15, 16).

In view of what has just been described, the staff of the Simple Departmental Operating Unit (SDOU) of PER of Piacenza Hospital (Italy) felt the need to implement, starting from 1 July 2017, PIPER best practice recommendations, initially applying them only to children with traumatic extremity pathology. This choice is since musculoskeletal trauma is a very frequent occurrence in childhood and fractures and sprains are one of the most painful events that can affect the child (17, 18). It is estimated, in fact, that one third of children suffer one or more fractures by the age of 17 (19) and that 20% of ED accesses in patients aged 3 to 14 are due to musculoskeletal trauma (20).

In particular, the recommendations provide for the use of the algometric scales FLACC (21-23), WONG-BAKER (24) and NRS (25) based on the age of the child, as indicated by literature (26,27), and the administration of analgesics by the nurse, based on protocols shared by the team, if the score obtained is> 4.

Aims

Based on literature evidences, the main purpose of the study was to detect a possible increase in the frequency of pain assessment and management during the triage phase after the introduction of the PIPER recommendations on 1 July 2017 in the Piacenza Hospital, Emilia-Romagna Region, Italy.

The second purpose was to detect the progress of the application of these recommendations one year after their introduction to monitor any further improvement in health care outcomes in pain treatment.

Methods

A retrospective observational study was chosen.

The data used were extrapolated from the discharge letters of the SDOU of Piacenza Hospital PER relating to the four months July-August-September-October of the years 2016, 2017 and 2018.

The four-month period chosen is July-October as the ward data identify that period of the year as the one in which extremity traumatized children access the PER most frequently.

The reference population is made up of PER discharge letters from children between the ages of 0 and 9, who had access to the PER presenting a trauma to the upper or lower extremity without concomitant trauma in other body areas.

A convenience sampling was chosen. All discharge letters from children meeting the eligibility criteria who had access to the PER in the four months examined were included in the study.

Minors with traumatic pathology and age greater than or equal to 10 years were excluded from the study, given that in the analyzed context (Piacenza Hospital) these children have direct access to the General Emergency Room or the Orthopedic Emergency Room.

Thanks to the data made available by the Operational Unit of Management Control of the Piacenza Hospital all the letters of discharge from the PER referring to the four months in question have been identified that report “trauma” as a presentation symptom and/or the word “trauma” in the diagnosis of discharge and which refer to children aged between 0 and 9 years old.

Subsequently, all patients whose presentation symptoms and discharge diagnosis did not meet the eligibility criteria (other trauma and non-extremity trauma) were excluded.

Thanks to the history provided by the PER management software, it was possible to access the discharge letters of the sample identified in the report created and the data to be included in the Case Report Form (CRF) were extrapolated.

Then the CRF was constructed in which the progressive number with which the discharge letters were identified and the following data were entered: i) evaluation of pain in triage; ii) triage treatment; iii) treatment during medical examination; iv) no treatment for score <4; v) non-treatment score> 4; vi) treatment refused; vii) treatment at home; viii) failure to perform pain assessment and treatment.

According to the PIPER recommendations applied by the triage nurses, pain involves pharmacological treatment where the score is higher than 4, quantified by the FLACC (21-23), WONG-BAKER (24) or NRS (25) scale according to age of the subject, and in the absence of specific exclusion criteria, such as intake of a painkiller drug in the previous 4 hours, presence of nausea or vomiting, known allergy to paracetamol or ibuprofen or known gastropathies.

Data analysis

The descriptive statistics, concerning the pain assessment and management data extrapolated for each four-month period, with the calculation of frequencies and percentages, and the “Chi-Square” significance test for the comparison of the four-month periods were processed. The software was Microsoft Excel 2010. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The study was approved by the Local Area Ethics Committee on February 19, 2019 (Practice 1172/2018/OSS*/AUSLPC) and authorized by the Piacenza Hospital General Management on 26/02/2019.

Results

811 discharge letters were analyzed, of which 309 referred to 2016, 243 to 2017 and 259 to 2018. The data obtained from the analysis are shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Absolute frequencies of the variables considered in the analysis

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | ||

| Pain evaluation | Done at triage | 12 | 227 | 245 |

| Not done at triage | 297 | 16 | 14 | |

| Pain treatment | Only done at triage | 4 | 68 | 70 |

| Only done during medical visit | 21 | 11 | 11 | |

| Done at triage and during medical visit | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Refused | 0 | 3 | 6 | |

| Already done at home | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| Not done due to score <4 | 8 | 144 | 147 | |

| Not done despite score >4 | 1 | 4 | 8 | |

| Pain not evaluated nor treated | 275 | 13 | 11 | |

| Total | 309 | 243 | 259 | |

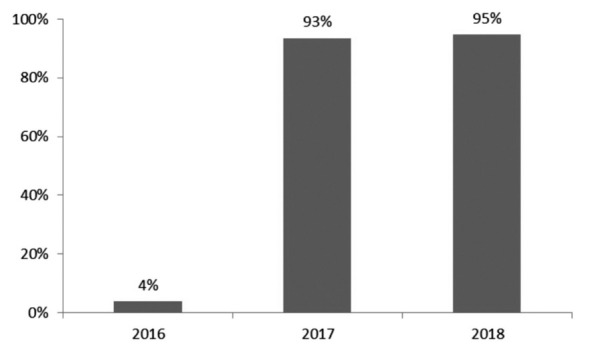

As can be seen from Figure 1, in 2016 pain was assessed in 12 patients out of a total of 309 (3.88%), in 2017 in 227 patients out of a total of 243 (93.42%) and in 2018 in 245 patients out of a total of 259 (94.59%).

Figure 1.

Percentage of Patients evaluated in triage (N=811)

The number of assessments in 2017 (227 out of 243) significantly increased compared to 2016 (12 out of 309); p = 1.36E-98. On the other hand, the number of evaluations does not change when comparing 2017vs2018 (245 out of 259), p = 0.58.

Regarding the treatment of pain, in 2016, 25 patients were treated: 4 patients during the triage phase, 21 during the medical examination, while 8 were not treated with a score lower than 4 and 1 despite the score higher than 4. None refused the treatment.

In 2017, 79 patients were treated: 68 during the triage phase and 11 during the medical examination. 8 of these patients were treated despite having a score lower than 4. Of these patients, 4 took the drug therapy during the triage phase and 4 during the medical examination. 3 patients refused treatment.

In 2018, 82 patients were treated: 70 during the triage phase, 11 during the medical examination and 1 both during the triage phase and during the medical examination. There are 11 patients treated with a score lower than 4 who have taken painkiller therapy, of which 3 during triage phase and 8 during the medical examination. Untreated patients with scores higher than 4 are 8. In total, 6 patients refused treatment, of which 3 with scores lower than 4 and 3 with scores higher than 4.

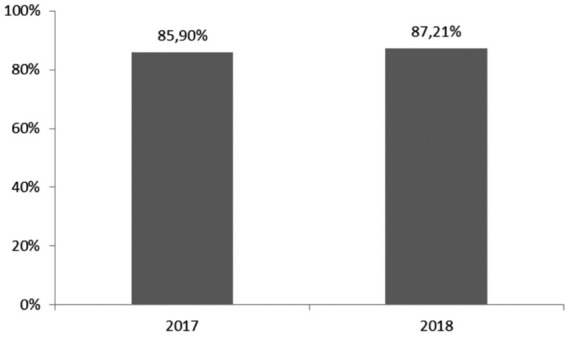

In 2017, 78 patients were evaluated, with scores higher than 4, and, also considering the treatments at home and the treatments refused, the drug was proposed during the triage phase in 85.90% of cases. In 2018, on the other hand, 86 were assessed with scores higher than 4 and the drug was proposed during the triage phase in 87.21% of cases, including refused treatments and patients who had been administered therapy at home (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients treated in triage versus evaluation > 4 (N =164)

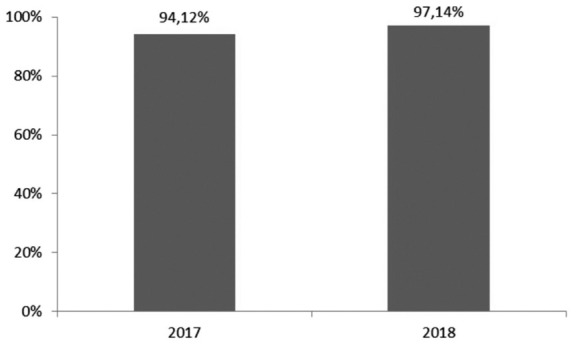

Furthermore, in 2017 out of a total of 68 patients treated during the triage phase, 64, (corresponding to 94.12%), presented a score> 4 and, in 2018, the treated patients with a score> 4 were 68 out of a total of 70. So, in the 2018 the % of patients treated with score> 4 was 97.14% (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage of patients treated with > 4 of the total treatments (N =138)

Discussion

The available literature concerning the percentages of children presenting with the pain symptom (3-5) and that concerning musculoskeletal trauma (17-20) are not recent. Therefore, it would be interesting, in the future, to analyze more updated data.

Regarding the 2016 data, it is difficult to draw unambiguous conclusions, because a lot of data is missing from the triage forms. Therefore, more patients could have been evaluated than the 12 indicated and the 4 patients treated in triage do not necessarily fall within the 12 evaluated. However, it can be said with certainty that pain assessment was lacking, in line with literature data (12, 14, 16, 28).

After the introduction of the PIPER best practice recommendations, starting from 2017, the percentage of patients who were administered an algometric assessment scale during the triage phase increased, exceeding 90% both in 2017 and in 2018, determining also the increase in patients treated pharmacologically for pain. These results confirm those reported by Thomas et al. (29) on the increase in pain treatment in the presence of triage protocols for nurses and by the Italian survey on hospitals that have joined the project PIPER (15).

We can also note that in the years 2017 and 2018 the majority of patients who received drug treatment, above 94% in both cases, had a score> 4. Therefore, it can be said that therapeutic appropriateness has also improved.

With regard to the statistical significance tests, 2016 and 2017 were compared only for the number of assessments, given the unreliability of the data on the treatment relating to 2016. The comparison however resulted in a highly significant increase in assessments after the introduction of the PIPER recommendations.

With regard to the evaluations of 2017 compared to that of 2018, the statistical significance has not been confirmed, even if the trend indicates a slight increase in the percentage of evaluations.

As for the years 2017 and 2018, we can state that the data confirm what the recent literature states (29, 30), namely that the implementation of the PIPER recommendations has improved pain management in PERs.

Therefore, if the introduction of the recommendations has led to a significant improvement, some small management errors have been made, however, which can certainly be improved with continuous training. In particular, 4 patients in 2017 and 8 in 2018 were not treated either in triage or during the medical examination despite having obtained a score > 4. In addition, 8 patients in 2017 and 11 in 2018 were proposed and administered the drug even with a score < 4. In addition to the latter, 3 additional patients were added to whom pain treatment was proposed but rejected.

Conclusion

The study has some limitations: it only takes into consideration extremity traumatized children; does not take into account non-pharmacological analgesic techniques; does not evaluate the effectiveness of the analgesic; it does not analyze the procedural pain detection in case of application of immobilization devices. These factors should therefore be evaluated in future research. Additionally, the study is retrospective and analyzes data collected from discharge letters in which some data may not have been reported.

Despite these limitations, the study highlighted that the introduction of the PIPER best practice recommendations has increased the frequency of algometric pain assessments during the triage phase, supporting the nurse in this phase and leading to an improvement in healthcare outcomes in terms of pain symptom management, in line with the study by Benini et al. (30). The results are also consistent with the study of Guiner et al. (31), that states that the introduction of a pain management protocol in the Emergency Department has improved pain management, with a significant increase in patients with severe pain receiving analgesic drugs.

The almost constant trend in the 2 years examined in which the recommendations were active, suggests that the project is reliable even after some time, even in the face of the high staff turnover that affected the PER under study.

The implementation of PIPER recommendations, or similar projects, and the continuous updating of professionals on the management of pain symptoms is therefore strongly recommended for all PERs.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Maurizio Beretta for the English translation.

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- 1.Part III: Pain Terms, “A Current List with Definitions and Notes on Usage” (pp 209-214) Classification of Chronic Pain, Second Edition, IASP Task Force on Taxonomy, edited by H. Merskey and N. Bogduk. Seattle: IASP Press,1994 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare. Organizations, Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals. Oakbrook Terrace, II: Joint Commission Resources. 2001 Avaiable at https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/pain-management/2001_pain_standardspdf.pdf?db=web&hash=C11475CEAF841C3117874C83193FE8B6 . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benini F. Il dolore nel bambino: Il gruppo terapeutico con i genitori, esperienza di sostegno alla genitorialità. [Pain in children: The therapeutic group with parents, experience of parenting support] Quad Acp. 2010;17(2):70–3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krauss BS, Calligaris L, Green SM, Barbi E. Current concepts in management of pain in children in the emergency department. The Lancet. 2016;387(10013):83–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61686-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pretorius A, Searle J, Marshall B. Barriers and Enablers to Emergency Department Nurses’ Management of Patients’ Pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(3):372–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Accordo tra il Ministro della Sanità, le Regioni e le Province autonome, 24 maggio 2001. LINEE GUIDA PER LA REALIZZAZIONE DELL’” OSPEDALE SENZA DOLORE”. [Agreement of the Minister of Health, the Regions and the Autonomous Provinces, 24 May 2001. GUIDELINES FOR THE REALIZATION OF THE “HOSPITAL WITHOUT PAIN”] 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Approvazione del «Piano sanitario nazionale» 2006-2008. (GU Serie Generale n.139 del 17-06-2006 - suppl. Ordinario n.149). Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica 7 aprile 2006. [Approval of the “National health plan” 2006-2008. (GU General Series n.139 of 17-06-2006 - Suppl. Ordinary n.149). Decree of the President of the Republic April 7, 2006] Available at: www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2006/06/17/06A05518/sg . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministero della Salute. Il dolore nel bambino. Strumenti Pratici di Valutazione e Terapia. Value Relations International s.r.l. [Ministry of Health. Pain in the child. Practical Assessment and Therapy Tools. Value Relations International s.r.l.]; 2010 Available at: http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_1256_allegato.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Probst BD, Lyons E, Leonard D, Esposito TJ. Factors affecting emergency department assessment and management of pain in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21(5):298–305. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000159074.85808.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrack EM, Christopher NC, Kriwinsky J. Pain management in the emergency department: patterns of analgesic utilization. Pediatrics. 1997;99(5):711–714. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown JC, Klein EJ, Lewis CW, Johnston BD, Cummings P. Emergency department analgesia for fracture pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(2):197–205. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kircher J, Drendel AL, Newton AS, Dulai S, Vandermeer B, Ali S. Pediatric musculoskeletal pain in the emergency department: a medical record review of practice variation. Can J Emerg Med. 2014;16(6):449–457. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500003468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weng Y-M, Chang Y-C, Lin Y-J. Triage pain scales cannot predict analgesia provision to pediatric patients with long-bone fracture. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(4):412–417. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrante P, Cuttini M, Zangardi T, Tomasello C, Messi G, Pirozzi N, et al. Pain management policies and practices in pediatric emergency care: a nationwide survey of Italian hospitals. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13(1):139. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benini F, Castagno E, Milani GP. La gestione del dolore nel bambino in pronto soccorso: Survey negli ospedali Italiani. [Pain management in the child in the emergency room survey in Italian hospitals] Quad ACP. 2019;26(3):110–112. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Congedi S, Benini F, Rossin S, Pennella A. THE PIPER WEEKEND STUDY. Children’s and adults satisfaction regarding pediatric pain in Italian Emergency Department. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2018;54(1):12–19. doi: 10.4415/ANN_18_01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Downing A, Rudge G. A study of childhood attendance at emergency departments in the West Midlands region. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(5):391–393. doi: 10.1136/emj.2005.025411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy RM, Luhmann JD, Luhmann SJ. Emergency department management of pain and anxiety related to orthopedic fracture care. Pediatr Drugs. 2004;6(1):11–31. doi: 10.2165/00148581-200406010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper C, Dennison EM, Leufkens HG, Bishop N, van Staa TP. Epidemiology of childhood fractures in Britain: a study using the general practice research database. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(12):1976–1981. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Inocencio J, Carro MÁ, Flores M, Carpio C, Mesa S, Marín M. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal pain in a pediatric emergency department. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36(1):83–89. doi: 10.1007/s00296-015-3335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merkel S, Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S. Pain Assessment in Infants and Young Children: The FLACC Scale: A behavioral tool to measure pain in young children. AJN Am J Nurs. 2002;102(10):55–58. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200210000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manworren RC, Hynan LS. Clinical validation of FLACC: preverbal patient pain scale. Pediatr Nurs. 2003;29(2):140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kochman A, Howell J, Sheridan M, Kou M, Ryan EES, Lee S, et al. Reliability of the faces, legs, activity, cry, and consolability scale in assessing acute pain in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017;33(1):14–17. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong-Baker FACES foundation. Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale. Avaiable at https://wongbakerfaces.org/ . Accessed in August 27, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCaffery M, Beebe A. others. Pain: Clinical manual for nursing practice, Mosby St. Louis Mo. 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drendel AL, Kelly BT, Ali S. Pain assessment for children: overcoming challenges and optimizing care. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(8):773–781. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31822877f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freund D, Bolick BN. CE: Assessing a Child’s Pain. AJN Am J Nurs. 2019;119(5):34–41. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000557888.65961.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abouzida S, Bourgault P, Lafrenaye S. Observation of Emergency Room Nurses Managing Pediatric Pain: Care to Be Given… Care Given…. Pain Manag Nurs. 2020; Volume publish ahead of print. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2020.03.002. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1524904220301077 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas D, Kircher J, Plint AC, Fitzpatrick E, Newton AS, Rosychuk RJ, et al. Pediatric pain management in the emergency department: the triage nurses’ perspective. J Emerg Nurs. 2015;41(5):407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benini F, Castagno E, Urbino A, Fossali E, Mancusi R, Milani G. Pain management in children has significantly improved in the Italian emergency departments. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(7):1445–1449. doi: 10.1111/apa.15137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guiner A, Street MH, Oke O, Young VB, Hennes H. Pain Reduction Emergency Protocol: A Prospective Study Evaluating Impact of a Nurse-initiated Protocol on Pain Management and Parental Satisfaction. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020 doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002193. Volume Publish Ahead of Print-Issue-doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]