Abstract

Heterosis has been extensively utilized to increase productivity in crops, yet the underlying molecular mechanisms remain largely elusive. Here, we generated transcriptome-wide profiles of mRNA abundance, m6A methylation, and translational efficiency from the maize F1 hybrid B73×Mo17 and its two parental lines to ascertain the contribution of each regulatory layer to heterosis at the seedling stage. We documented that although the global abundance and distribution of m6A remained unchanged, a greater number of genes had gained an m6A modification in the hybrid. Superior variations were observed at the m6A modification and translational efficiency levels when compared with mRNA abundance between the hybrid and parents. In the hybrid, the vast majority of genes with m6A modification exhibited a non-additive expression pattern, the percentage of which was much higher than that at levels of mRNA abundance and translational efficiency. Non-additive genes involved in different biological processes were hierarchically coordinated by discrete combinations of three regulatory layers. These findings suggest that transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression make distinct contributions to heterosis in hybrid maize. Overall, this integrated multi-omics analysis provides a valuable portfolio for interpreting transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression in hybrid maize, and paves the way for exploring molecular mechanisms underlying hybrid vigor.

Keywords: Heterosis, maize, mRNA, post-transcriptional regulation, RNA m6A, translational efficiency

A maize F1 hybrid and its parental lines showed dissimilarities of regulatory and heterotic patterns of genes undergoing hierarchical regulation at the mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency.

Introduction

Hybrid vigor, or heterosis, refers to the superior performance of F1 hybrids over their parents. In plants, heterotic traits are mainly related to growth rate, biomass, stress tolerance, and seed yield. All these traits are crucial for increasing crop yield. The widespread application of heterosis is one of the landmark innovations of modern agriculture, and breeding hybrids has proved to be one of the most efficient ways to increase grain yield of various crops (Hochholdinger and Baldauf, 2018). Although heterosis has been successfully exploited in crop production, the molecular mechanisms underlying it remain largely elusive. Dominance, overdominance, and epistasis have been proposed as classical genetic explanations for heterosis, but these hypotheses have not been connected to molecular principles and do not provide a molecular basis for heterosis (Birchler et al., 2003, 2010).

The putative molecular mechanisms of heterosis are connected with genomic and epigenetic modifications in hybrids. These modifications, in turn, yield advantages in growth, stress resistance, and adaptability of F1 hybrids over their parents due to interactions between alleles of the parental genomes that alter regulatory networks of related genes (Alonso-Peral et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2017). Genetic variation is widely studied to understand the molecular basis of heterosis (Huang et al., 2015; Morris et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2020). It is assumed that a combination of different genetic principles might run together to explain hybrid vigor (Swanson-Wagner et al., 2006; Lippman and Zamir, 2007). To better decipher the processes underlying the manifestation of heterosis for various phenotypic traits, multifaceted molecular data have been collected at different regulatory levels including the genome (Huang et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020), epigenome (Groszmann et al., 2011; Shen et al., 2012; He et al., 2013; Kawanabe et al., 2016; Shen et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2017; Lauss et al., 2018; Sinha et al., 2020), transcriptome (Paschold et al., 2012; Baldauf et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2016; Alonso-Peral et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2017; Shao et al., 2019; Sinha et al., 2020), proteome (Hoecker et al., 2008), and metabolome (Romisch-Margl et al., 2010). However, to date we still lack, for any species, fundamental knowledge of how post-transcriptional activities are involved in heterosis.

Modification of the nucleotides of mRNA adds extra information that is not encoded in the mRNA or DNA sequence. The emerging field of epitranscriptomics studies where modified nucleotides are present in mRNA, how they are positioned, read and removed (by ‘writers’, ‘readers’, and ‘erasers’, respectively), and how they may regulate RNA metabolism (Meyer and Jaffrey, 2017; Roignant and Soller, 2017; Roundtree et al., 2017a; Yang et al., 2018; Shen et al., 2019; Yue et al., 2019). N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most prevalent covalent modification in mRNA and long non-coding RNA (Dominissini et al., 2012; Meyer et al., 2012). Dynamic m6A modification has been implicated in a wide range of RNA metabolic processes, including RNA stability (Wang et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2018), translation (Meyer et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017; Shi et al., 2017; Slobodin et al., 2017; Meyer, 2018), alternative splicing (Zhao et al., 2014; Haussmann et al., 2016; Lence et al., 2016; Xiao et al., 2016a; Bartosovic et al., 2017; Pendleton et al., 2017), secondary structure (Liu et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017), and nuclear export (Zheng et al., 2013; Roundtree et al., 2017b). In plants, many studies have recently shown that m6A modification plays important roles in regulating development (Zhong et al., 2008; Bodi et al., 2012; Shen et al., 2016; Ruzicka et al., 2017; Arribas-Hernandez et al., 2018; Scutenaire et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019; Luo et al., 2020; Du et al., 2020) and stress tolerance (Martinez-Perez et al., 2017; Anderson et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Miao et al., 2020).

Maize is one of the most important crops worldwide. As a cross-pollinating plant, it displays much stronger heterosis than most other crops. In addition, maize has a remarkable degree of structural intraspecific genomic diversity (Springer et al., 2009). These special characteristics have enabled maize to act as a model organism for studying heterosis over the past few decades. In this study, we integrated and compared the profiles of mRNA abundance, m6A methylation, and translational efficiency between the maize F1 hybrid B73×Mo17 and its two parental lines to study the association of post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression with heterosis. Our results revealed fairly unique heterotic patterns at different regulatory levels, highlighting that transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression make distinct contributions to heterosis in hybrid maize.

Materials and methods

Plant material phenotyping

The maize F1 hybrid B73×Mo17 and its parental inbred lines B73 and Mo17 were used in this study. All seeds were sterilized by 70% ethanol and 5% sodium hypochlorite solution and rinsed with sterile water. Then seeds were sown in pots with vermiculite and soil (1:1, v/v) in a growth chamber (16 h of light at 28 °C and 8 h dark at 25 °C). Positioning of the F1 hybrid and parental plants was randomized every day. After 14 d, aerial tissues were harvested, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent experiments. The other batch of plants (n=15) were used to investigate heterotic traits, including plant height and fresh weight. Statistical significance of differences of heterotic traits was determined using Student’s t-test.

Quantification of m6A by LC-MS/MS

Two hundred nanograms of mRNA was digested with 1 U Nuclease P1 (Wako) in buffer containing 10% (v/v) 0.1 M CH3COONH4 (pH 5.3) at 42 °C for 3 h, followed by the addition of 1 U shrimp alkaline phosphatase (NEB) and 10% (v/v) Cutsmart buffer and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. Then the sample was diluted to 50 μl and filtered through a 0.22 μm polyvinylidene difluoride filter (Millipore). Finally, 10 μl of the solution was used for LC-MS/MS. Nucleosides were separated using reverse-phase ultra-performance liquid chromatography on a C18 column coupled to online mass spectrometry detection using an Agilent 6410 QQQ triple-quadrupole LC mass spectrometer in positive ion mode. The nucleosides were quantified by comparison with the standard curve obtained from pure nucleoside standards run in the same batch as the samples. The ratio of m6A/A was calculated based on the calibration curves.

m6A methylated RNA immunoprecipitation

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and polyadenylated RNA was subsequently isolated with the GenElute mRNA Miniprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. m6A immunoprecipitation was performed using the Magna methylated RNA immunoprecipitation (MeRIP) m6A kit (Millipore) following the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, 27 μg mRNA was fragmented and ethanol precipitated and 0.5 μg RNA was removed as input control. Meanwhile, 30 μl magnetic A/G beads was incubated with 10 μg anti-m6A antibody (MABE1006) in 1× immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer for 30 min at room temperature. Then all remaining fragmented mRNA was incubated with the antibody–beads at 4 °C for 2 h with rotation. After being washed three times with 1× IP buffer, bound RNA was eluted from the beads with 100 μl elution buffer twice and then purified with the RNA Clean & Concentrator Kit (Zymo). Both purified sample and input control were used for library construction.

Polysome profiling

Polysome profiling was performed as previously described (Zhang et al., 2017). Briefly, 2 g tissue was ground and lysed by incubation for 15 min on ice in 5 ml of polysome extraction buffer (PEB; 200 mM Tris–HCl pH 9.0, 200 mM KCl, 35 mM MgCl2, 25 mM EGTA, 1% (v/v) Tween 20, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 2% (v/v) polyoxyethylene, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 500 μg ml−1 heparin, 100 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol, and 25 μg ml−1 cycloheximide). After centrifuging at 13 200 g for 15 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was loaded on top of a 1.7 M sucrose cushion and centrifuged at 246 078 g (SW55Ti rotor in a Beckman L-100XP ultracentrifuge) for 3 h at 4 °C. The pellet was washed with RNase-free water and resuspended with 200 μl resuspension buffer (200 mM Tris–HCl pH 9.0, 200 mM KCl, 35 mM MgCl2, 25 mM EGTA, 100 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol, and 25 μg ml−1 cycloheximide). Then the solution was loaded onto a 20–60% sucrose gradient and centrifuged at 204 275 g (SW55Ti rotor) for 2 h at 4 °C. The sucrose gradients were monitored and fractionated with a gradient fractionator (Biocomp, Canada). The polysomal RNA fractions were collected and extracted for library construction.

Library construction and sequencing

Libraries of RNA-seq, m6A-seq, and polysome profiling for the F1 hybrid were constructed using the NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit (E7770S, NEB) following the manufacturer’s protocol and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform using 150 bp paired-end sequencing.

m6A-seq data analysis

Sequencing reads were filtered to remove adapter sequences and low-quality reads using Trimmomatic (v0.35) (Bolger et al., 2014) with parameters ILLUMINACLIP:TruSeq3-PE.fa:2:30:10:1:true LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 MINLEN:30. To reduce mapping bias and for convenience in comparing the F1 hybrid and parents, filtered reads from B73 and F1 hybrid B73×Mo17 were mapped to the maize B73 reference genome (AGPv4.38) (Jiao et al., 2017), and filtered reads from Mo17 were mapped to the maize Mo17 pseudogenome constructed by substituting maize B73 reference genome (AGPv4.38) with single nucleotide polymorphisms from Mo17 (CAU-1.0) (Sun et al., 2018) using Hisat2 (v2.1.0) (Kim et al., 2015) with parameters −5 1 −3 1 −−dta. m6A peaks were identified by MACS2 peak calling software (v2.1.1) (Zhang et al., 2008) with q<0.01 and the overlapped peaks between two biological replicates were designated as high confidence m6A peaks and used for subsequent analyses. The m6A level was defined as fold change of m6A peaks from MACS2 output.

RNA-seq analysis and translational efficiency calculation

For RNA-seq and polysome profiling, sequencing reads were filtered and mapped as m6A-seq. The levels of transcription and translation were estimated by calculating fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments (FPKM) by the software StringTie v1.3.3 (Pertea et al., 2015) with default parameters. Only the genes with FPKM ≥1 were considered as expressed genes. The translational efficiency was calculated by ‘FPKM (translational level)/FPKM (transcriptional level)’ as reported previously (Lei et al., 2015). Differentially expressed genes were identified by the DESeq2 package (Love et al., 2014) with fold-change ≥1.5, P<0.01 between parents and between the hybrid and parents, and non-additive genes in the hybrid were defined with significantly differential expression levels against mid-parent value (MPV) at fold-change ≥1.5 and P<0.01. Similarly, differentially translated genes were identified by the Xtail package (v1.1.5) (Xiao et al., 2016b) with fold-change ≥1.5, P<0.01 between parents and between hybrid and parents, and non-additively translated genes in the hybrid were defined with significantly different translational efficiency against MPV at fold-change ≥1.5 and P<0.01.

Gene ontology analysis

GO analysis were performed using FuncAssociate 3.0 (http://llama.mshri.on.ca/funcassociate/) (Berriz et al., 2009) and GO terms with adjusted P<0.001 were defined as significant.

Definition of cis and trans regulatory divergence

Unique reads of the F1 hybrid were obtained by selecting the alignment records with the ‘NH:i:1’ tag. Single nucleotide polymorphisms between the B73 and Mo17 genomes were identified with Mummer v3.0 (Kurtz et al., 2004) as described previously (Sun et al., 2018). SNPsplit v0.3.4 (Krueger and Andrews, 2016) was used with default parameters to determine the parental origins, and all SNP-containing reads were used for allele-specific expression analyses. Cis and trans effects were explored as previously described (Bao et al., 2019). Parental gene expression and F1 allelic expression were combined to characterize cis and trans effects. Parental gene expression divergence was defined as A, and F1 allelic expression divergence as B. The genes exhibited F1 allelic divergence equivalent to parental gene expression divergence were considered to be caused by only cis effects ((i) A≠0, B≠0, A=B). If parents showed significant divergence but not F1 allelic expression, genes were considered to be caused by only trans effects ((ii) A≠0, B=0, A≠B). Genes exhibiting F1 allelic divergence that significantly diverged from parental gene expression divergence ((iii) A≠0, B≠0, A≠B) were considered to be enhancing or compensating, which was dependent on whether the cis and trans effects were in the same or opposite directions, respectively. When F1 allelic expression showed significant divergence but not between parents, genes were considered as fully compensatory ((iv) A=0, B≠0, A≠B). Genes belonging to category (iii) and (iv) were combined and defined as both cis and trans effect. Neither parental gene expression divergence nor F1 allelic expression divergence was detected, which was defined as conserved genes ((v) A=0, B=0, A=B).

RT-qPCR

RT-qPCR was performed as described in Duan et al. (2017) and Zhang et al. (2017). Briefly, RNA from m6A-IP, input, and polysome profiling was used for reverse transcription with the PrimeScriptTM RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa). RT-qPCR was performed with TB Green Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa) using a Bio-Rad CFX96 real-time PCR detection system. Zm00001d034600 and Zm00001d042939 were used as internal control genes due to their invariant expression among hybrid and two parental lines B73 and Mo17 for all the three levels of mRNA abundance, m6A methylation, and translational efficiency according to the sequencing data. All primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Results

Remarkable redistribution of m6A epitranscriptome in maize hybrid

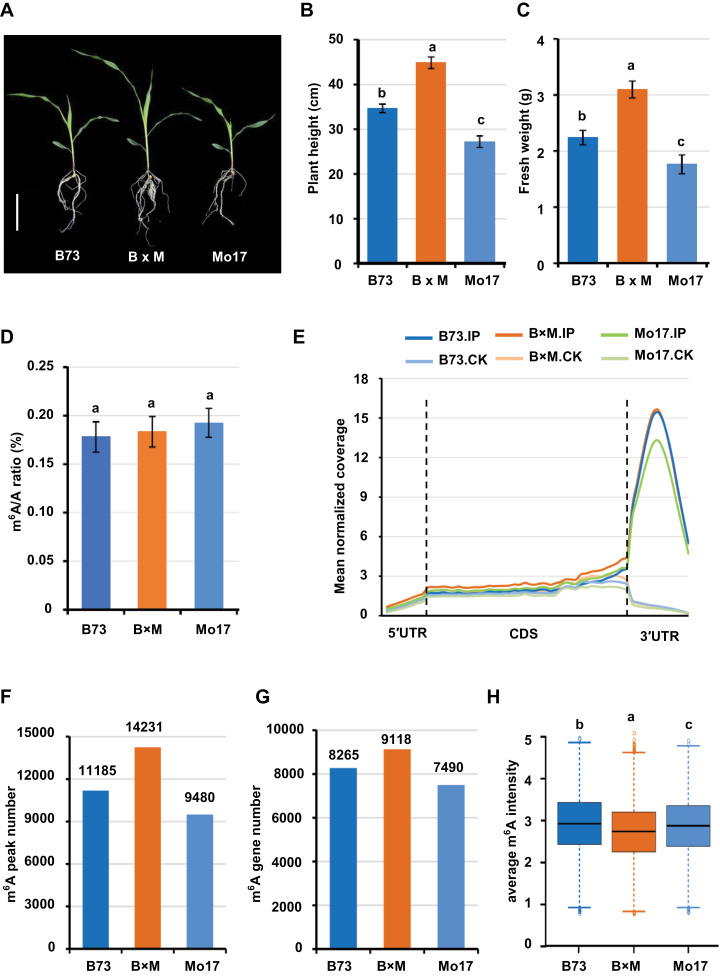

To better understand the molecular mechanisms underlying heterosis in maize, we used the maize inbred lines B73 and Mo17, and their F1 hybrid B73×Mo17 as research targets. Significant growth vigor in the F1 hybrid was observed at the early seedling stage 14 d after sowing (DAS) (Fig. 1A). We compared heterotic phenotypes for biomass, plant height, and fresh weight. The plant height of the F1 hybrid was 45.0% and 29.4% greater than the mid-parent value (MPV) and better parent value (BPV), respectively (Fig. 1B). The fresh weight of the F1 hybrid was 54.8% and 38.3% larger than the MPV and BPV, respectively (Fig. 1C). These results clearly indicate that the maize F1 hybrid B73×Mo17 plants at 14 DAS displayed vigorous heterosis, and therefore aerial tissues at 14 DAS were collected as research material for the subsequent analyses.

Fig. 1.

Heterosis of vegetative growth and m6A modification in maize F1 hybrid seedlings at 14 DAS. (A) Heterotic phenotype of the maize hybrid B73×Mo17 relative to the parental lines B73 and Mo17. Bar: 20 cm. (B–H) Comparison between hybrid and parental lines of plant height (B), fresh weight (C), total m6A abundance (D), m6A peak configuration (E), total number of m6A peaks (F), total number of m6A-modified genes (G), and average m6A intensity (H). IP, m6A peaks; CK, negative peaks. Duncan’s analysis was employed to test statistical significance between hybrid and parental lines. Different letters on the graphs indicate significant differences at P<0.05. Error bars indicate the standard deviation with 15 biological replicates in (B, C) and three biological replicates in (D). B×M, the hybrid B73×Mo17; CDS, coding sequence.

To explore whether epitranscriptomic regulation of gene expression is associated with heterosis, we firstly measured the m6A/A ratio of purified mRNA by using LC-MS/MS to show the global abundance of m6A modification in planta. As shown in Fig. 1D, no significant difference was observed for the m6A/A ratio between the F1 hybrid and the two parental lines, suggesting that the global m6A methylation abundance remains relatively stable in the hybrid.

To gain more insight into the regulation of m6A methylation in gene expression in the hybrid, we generated transcriptome-wide integrated maps of mRNA abundance, m6A methylation, and translational efficiency by conducting input RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), m6A RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (m6A-seq) (Dominissini et al., 2012; Meyer et al., 2012), and polysome profiling (Juntawong et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2017) in the F1 hybrid for two independent biological replicates. Critically, all plant material used to produce these datasets from hybrid and parental lines was grown at the exact same time and under the same conditions. It should be noted that the same datasets including RNA-seq, m6A-seq, and polysome profiling from the two parental lines, B73 and Mo17, have been published in our recent study to interpret natural variation in m6A modification (Luo et al., 2020). Two biological replicates showed a high degree of correlation for RNA-seq, m6A-seq, and polysome profiling data in the hybrid (see Supplementary Fig. S1) and in the parental lines (Luo et al., 2020). Moreover, for another two independent biological replicates the levels of mRNA abundance, m6A methylation, and translational efficiency for eight randomly selected genes were examined by RT-qPCR analysis, and were largely consistent with the sequencing data (Supplementary Figs S2–S4). These results corroborated the reliability of our data and allowed us to conduct further statistical analyses.

Similar to B73 and Mo17, m6A peaks in the hybrid were primarily enriched in the 3′-untranslated region (UTR; ~69.9%) and in the vicinity of the stop codon (~21.1%; defined as a 200-nt window centered on the stop codon), but were less present in coding sequences (CDS; ~3.2%), near start codons (~0.2%; defined as a 200-nt window centered on the start codon), in the 5′UTR (~0.6%), and in the spliced intronic regions (~5.1%; Fig. 1E; Supplementary Fig. S5), indicating that the overall configuration of m6A is unchanged in the hybrid. Interestingly, a much greater number of m6A peaks (n=14 231) were identified in the hybrid in comparison with the parental line B73 (n=11 185) and Mo17 (n=9480) (Fig. 1F), although the number of genes containing multiple m6A peaks was comparable between the hybrid and parental lines (Supplementary Fig. S6). Accordingly, the number of genes containing m6A peaks (n=9118; Supplementary Table S2) was greater in the hybrid than in the parental B73 (n=8265) and Mo17 (n=7490) lines (Fig. 1G). Interestingly, the average intensity of m6A peaks was less in the hybrid (Fig. 1H). These results suggest that m6A modification exhibits both common and unique features in the F1 hybrid in comparison with its parents.

Distinct regulatory patterns at the levels of mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency between hybrid and parents

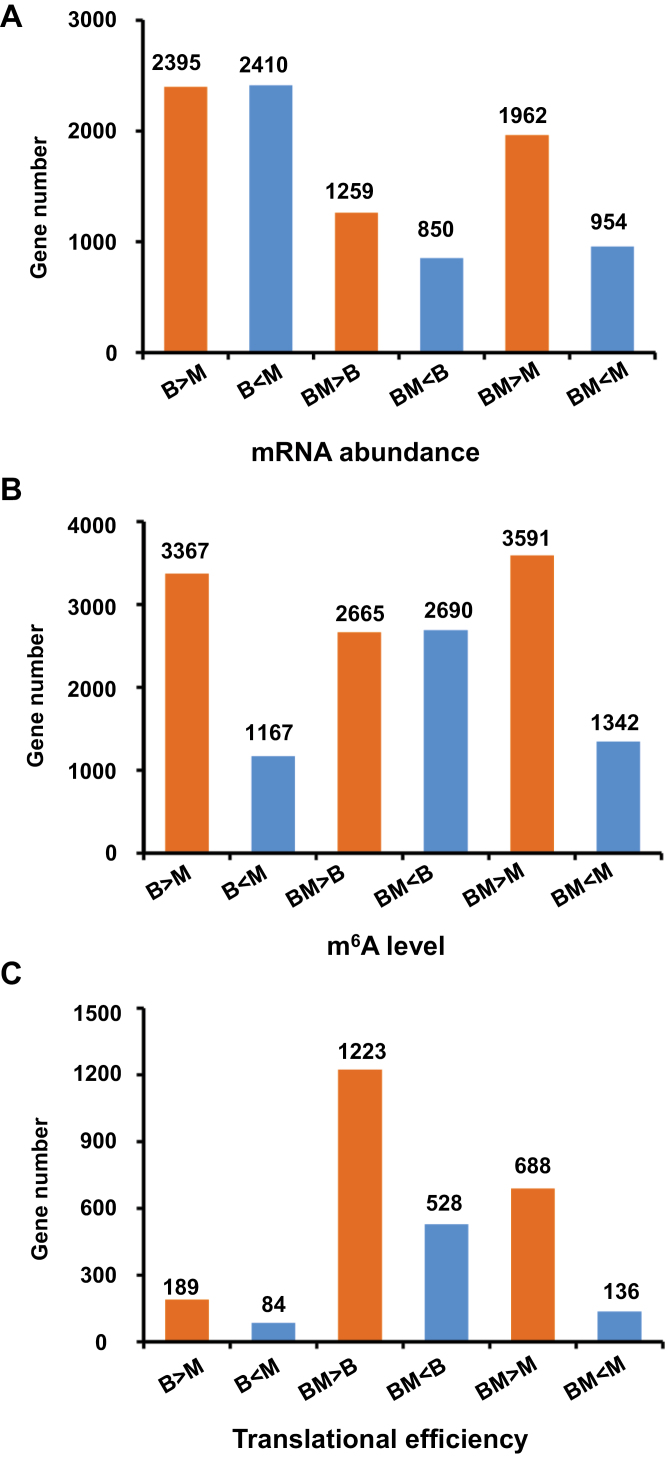

To ascertain conservation and divergence of mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency in the hybrid relative to the parental lines, six pairwise comparisons were performed per regulatory layer. Intriguingly, fairly distinct patterns in the pairwise comparisons between hybrid and parents and between parents were observed among the three regulatory layers. At the mRNA abundance level, the number of differentially expressed genes in parent–hybrid comparisons was substantially less than in parent–parent comparisons, with 4805 genes between parents in comparison with 2109 and 2916 genes in the hybrid relative to B73 and Mo17, respectively (Fig. 2A). At the m6A level, the number of genes with differential degrees of modification in parent–hybrid comparisons was approximately equal to that in parent–parent comparisons, with 4534 genes between parents in comparison with 5355 and 4933 genes in the hybrid relative to B73 and Mo17, respectively (Fig. 2B). At the translational efficiency level, the number of genes with differential translational efficiency in parent–hybrid comparisons was much greater than in parent–parent comparisons, where there were only 273 genes differing between parents in comparison with 1751 and 824 genes in the hybrid relative to B73 and Mo17, respectively (Fig. 2C). Together, these results indicate that transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression show distinct modes between the parents and hybrid.

Fig. 2.

Differential genes among hybrid and parents at the levels of mRNA abundance, m6A modification and translational efficiency. (A–C) Differential genes at the mRNA abundance level (A), m6A modification (B), and translational efficiency (C) were identified on the basis of six pairwise comparisons among the hybrid and parents. The number of differential genes, which were designated with false discovery rate (FDR) <0.01 and fold change ≥1.5, are shown above each bar. B, B73; M, Mo17; BM, B73×Mo17.

Distinct heterotic patterns at the levels of mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency in hybrid

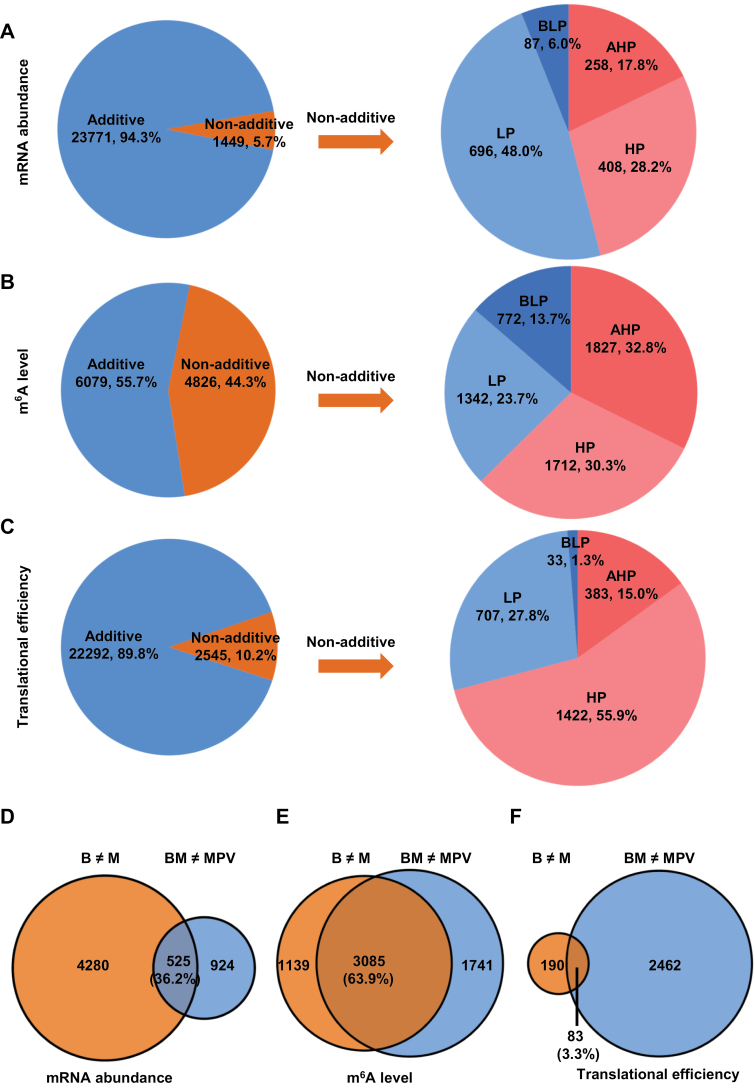

Non-additive gene action has been regarded as a specific expression pattern in hybrids and could potentially be responsible for generating heterotic phenotypes (Li et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2019). We designated genes in the F1 hybrid with a significant difference from MPV (P<0.01; false discovery rate (FDR)<0.01) as non-additive genes at each of the mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency levels. Strikingly, we observed that the percentage and number of non-additive genes were extraordinarily different at each of the three regulatory layers in the hybrid. In particular, 44.3% of m6A-modified genes (n=4826) were non-additive (Fig. 3B; Supplementary Table S3), and this percentage was far more than for non-additive genes at the mRNA abundance (5.7%, n=1449; Fig. 3A; Supplementary Table S4) and translational efficiency level (10.2%, n=2545; Fig. 3C; Supplementary Table S5). The large percentage of non-additive m6A modification implies its likely active involvement in heterosis.

Fig. 3.

Heterotic patterns at the levels of mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency in the hybrid. (A–C) Additive and non-additive variation and subdivided patterns of non-additive variation (AHP, above higher parent; HP, high parent; LP, low parent; BLP, below lower parent) at the levels of mRNA abundance (A), m6A modification (B), and translational efficiency (C) in the hybrid. The numbers and percentages of genes exhibiting additive and non-additive variation as well as subdivided patterns of non-additive variation are displayed. (D–F) Contribution to non-additive variation in the hybrid by the divergence of parents at the levels of mRNA abundance (D), m6A modification (E), and translational efficiency (F). B≠M, significant difference between parents; BM≠MPV, significant difference between hybrid and MPV. B, B73; BM, B73×Mo17; M, Mo17.

To better visualize non-additive genes in the hybrid, we divided the non-additive genes into four categories, including above higher parent (AHP; the value in the hybrid is above the higher parent), high parent (HP; the value in the hybrid is similar to the higher parent), low parent (LP; the value in the hybrid is similar to the lower parent), and below lower parent (BLP; the value in the hybrid is below the lower parent) (Birchler et al., 2003; Springer and Stupar, 2007). Again, we observed fairly distinct patterns of non-additive genes at each of the three regulatory layers. Different from the mRNA abundance level, at which the number and proportion of up-regulated genes (n=666, 46.0%) were moderately lower than those of down-regulated genes (n=783, 54.0%), the numbers and proportions of up-regulated genes at both the m6A modification (n=3539, 63.1%) and translational efficiency level (n=1805, 70.9%) were much greater than those of down-regulated genes (n=2114, 36.9%, and n=740, 29.1% for m6A modification and translational efficiency, respectively) (Fig. 3A–C), suggesting that increased m6A modification and translational efficiency may be critically involved in heterosis.

To characterize parent-of-origin effects on gene activity, we compared parental and heterotic variances at the levels of mRNA abundance, m6A methylation, and translational efficiency. Interestingly, we found that parental variances in m6A methylation contributed more to heterotic variances relative to mRNA abundance and translational efficiency. In detail, 63.9% of non-additive m6A-modified genes (Fig. 3E, n=3085) could be explained from parental variances, whereas only 36.2% (Fig. 3D, n=525) and 3.3% (Fig. 3F, n=83) could be explained at the mRNA and translational efficiency levels, respectively. Together, these results clearly indicate that transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression participate differently in the formation of heterosis in the maize hybrid.

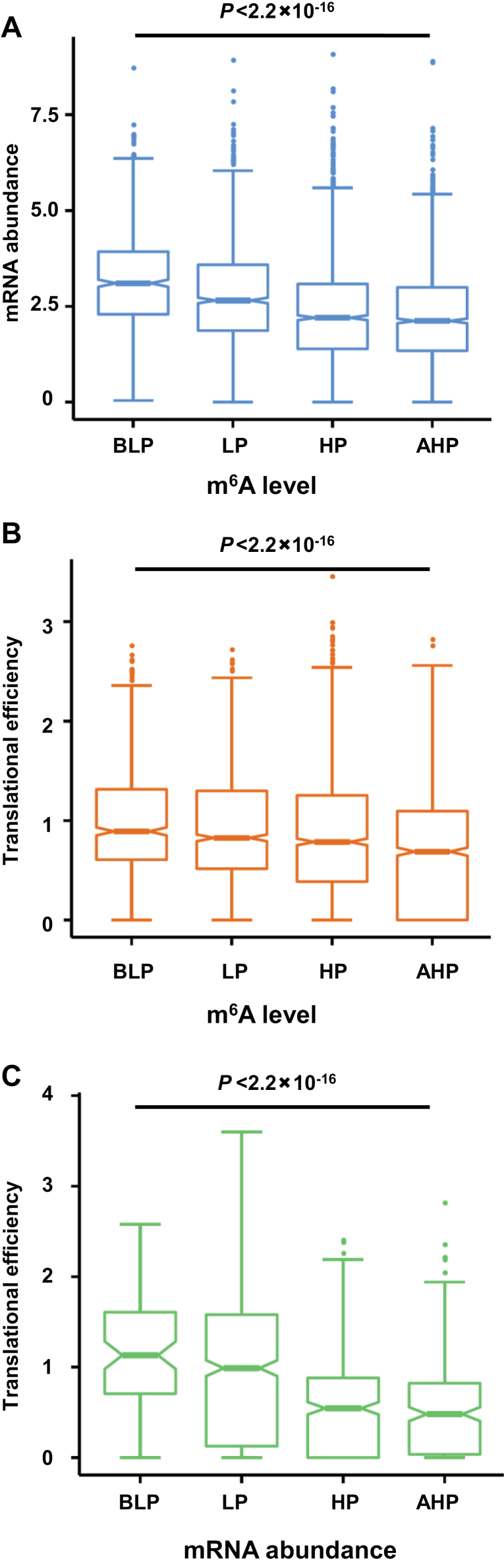

Cooperative regulation of mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency in hybrid

The key roles of m6A in epitranscriptomic regulation of gene expression prompted us to investigate its effects on mRNA abundance and translational efficiency. As shown in Fig. 4A, genes in the groups HP and AHP categorized by m6A level showed a decreased level of mRNA abundance compared with genes in the LP and BLP groups, suggesting that m6A modification may be actively involved in mRNA decay in the hybrid. Likewise, genes in the HP and AHP groups categorized by m6A level exhibited a tendency for decreased level of translational efficiency compared with genes in the LP and BLP groups (Fig. 4B), suggesting that the high degree of m6A modification may also attenuate translational efficiency in the hybrid. Moreover, genes in the HP and AHP groups categorized by mRNA abundance displayed a much lower level of translational efficiency than gene in the LP and BLP groups (Fig. 4C), suggesting that gene transcription and translation activity are negatively correlated in the hybrid. Together, these results suggest that mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency may cooperatively maintain the homeostasis status of non-additive gene expression in the hybrid.

Fig. 4.

Relationship of gene expression at the levels of mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency in the hybrid. (A) Correlation between mRNA abundance and different patterns of non-additively m6A-modified genes. (B) Correlation between translational efficiency and different patterns of non-additively m6A-modified genes. (C) Correlation between translational efficiency and different patterns of non-additively transcribed genes. The P-value was calculated using the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Distinct enrichment of biological pathways coordinated at the levels of mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency in hybrid

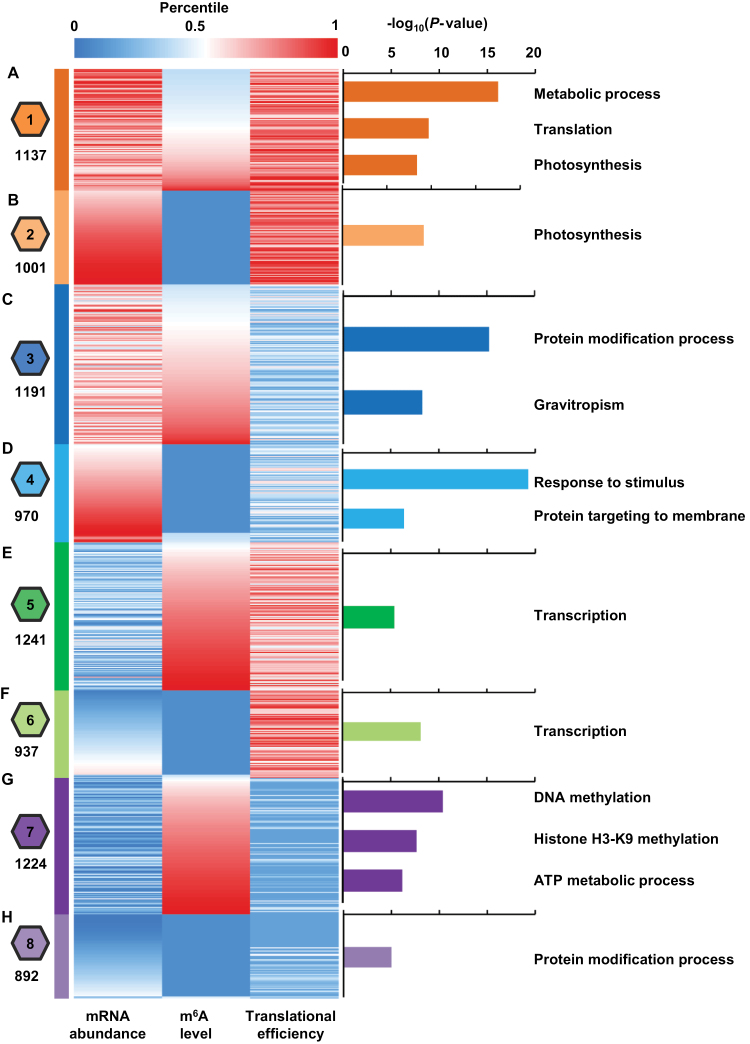

To investigate enrichment of biological pathways coordinated by the three different regulatory layers, we performed a k-means clustering analysis to group all the non-additive genes defined from all three regulatory layers into eight classes based on levels of mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency (Fig. 5A–H; see ‘Materials and methods’). We then conducted a Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis across all the different clusters (see Supplementary Table S6). Interestingly, we observed some common but mostly unique biological pathways enriched in each individual cluster (Fig. 5A–H).

Fig. 5.

Distinct enrichment of biological pathways coordinated at the levels of mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency in the hybrid. (A–H) Non-additive genes characterized by mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency were compiled together and subject to k-means clustering analysis. Each level of mRNA abundance, m6A intensity, and translational efficiency was converted to percentiles using the empirical cumulative distribution function. The color indicates the relative level of mRNA abundance, m6A intensity, and translational efficiency. A total of eight clusters were identified and the number of genes in each cluster is shown at the left. Significantly enriched gene ontology (GO) terms were identified by FuncAssociate 3.0 (permutation-based corrected P<0.001) and shown at the right. The details of all significantly enriched GO terms are listed in Supplementary Table S6.

In cluster 1, which was signified by a high level of mRNA abundance, median to high level of m6A modification, and high level of translational efficiency, the three most significantly enriched groups were metabolic process, translation, and photosynthesis (Fig. 5A). Similar with a high level of mRNA abundance and translational efficiency, but differing by a low level of m6A modification, cluster 2 only contained one group, photosynthesis (Fig. 5B). The shared group of photosynthesis between cluster 1 and cluster 2 suggests that high activity of transcription and translation for genes involved in the photosynthesis pathway is not affected by m6A modification.

In cluster 3, which was signified by a high level of mRNA abundance and m6A modification, but low level of translational efficiency, the two most significantly enriched groups were protein modification process and gravitropism (Fig. 5C). The opposite patterns of transcription and translation suggests that the high transcriptional activity of genes involved in these biological processes may be attenuated by decreased translational activity via a high degree of m6A modification. Cluster 4 was signified by a high level of mRNA abundance, but low levels of m6A modification and translational efficiency (Fig. 5D). The enriched groups included response to stimulus and protein targeting to membrane (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, the response to stimulus pathway represented the most significant group (P<5.4×10–20) and contained the maximum number of genes (n=278) identified in all the clusters. The opposite patterns of transcription and translation indicates that a high level of mRNA of genes involved in response to stimulus pathway may be substantially attenuated by decreased translational activity, and this attenuation is likely not dependent on m6A modification.

Cluster 5 and cluster 6 were signified by a low level of mRNA abundance and high level of translational efficiency, but differed in the level of m6A modification (Fig. 5E, F). The same but only pathway enriched in these two clusters was transcription (Fig. 5E, F), suggesting that the reduced transcription of genes involved in the transcription pathway may be compensated by increased translational activity in the hybrid, whereas this increase is not likely dependent on m6A modification. Cluster 7 was signified by a high level of m6A modification, and contained three groups, DNA methylation, histone H3–K9 methylation, and ATP metabolic pathways (Fig. 5G). Cluster 8 exhibited low levels at all three regulatory layers (Fig. 5H). Together, the specific enrichments identified in all eight clusters suggest that genes involved in various biological pathways may be subject to hierarchical coordination in terms of three regulatory layers.

Distinct cis and trans regulatory patterns at the levels of mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency in hybrid

Previous studies have reported that parental alleles show biased expression in maize hybrids (Stupar and Springer, 2006; Guo et al., 2008). To understand how parental alleles contribute to differential gene expression in three different regulatory layers, we performed allelic bias analysis in the hybrid using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between parental lines B73 and Mo17. Allele-specific sequencing reads discriminated by SNPs were utilized to evaluate allelic bias in the hybrid. To ensure accuracy and reliability, only SNPs identified with a significant allele-specific bias at a P-value cutoff below 0.01 in the hybrid were used in further analyses. Using this criterion, 973, 41, and 30 genes were identified with allelic bias for mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency, respectively (Table 1). Discrimination of the differential allelic effects based on the direction of allelic bias in the hybrid exhibited no obvious bias toward either B73 or Mo17 (Table 1), indicating that two parental genomes may contribute equally to the mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency in the maize hybrid.

Table 1.

Genes with allelic bias at the levels of mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency in the hybrid

| Total | Total Ba:Ma>1 | Ba:Ma<1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA abundance | 973 | 462 | 511 |

| m6A modification | 41 | 19 | 22 |

| Translational efficiency | 30 | 16 | 14 |

Only genes identified with a significant allelic bias at a P-value cutoff of 0.01 were included. Ba, B73 allele; Ma, Mo17 allele.

Gene expression is regulated through the interactions of cis and trans regulatory elements. Cis regulatory elements are short DNA sequences containing specific binding sites for trans factors to control expression of their associated genes (Bao et al., 2019). Based on the statistical tests of parental and F1 alleles, genes were assigned to one of four regulatory categories, namely cis only, trans only, cis and trans, and conserved genes (Table 2). Although the category of conserved genes represented the majority in all three regulatory layers, the percentage of genes in the other three categories displayed substantial differences (Table 2). In particular, a large number of trans-only genes (n=988, 25.7%) were observed at the level of m6A modification (Table 2), suggesting that the trans effect may play a greater role than cis or cis and trans effects in defining differentially m6A-modified genes in the F1 hybrid.

Table 2.

Number and percentage of genes with a cis- or trans-effects only, with both cis- and trans-effects, or conserved genes at the levels of mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency

| mRNA abundance (n (%)) | m6A modification (n (%)) | Translational efficiency (n (%)) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cis only | 487 (4.1) | 16 (0.4) | 1 (0.0) |

| Trans only | 446 (3.7) | 988 (25.7) | 153 (1.1) |

| Cis and trans | 377 (3.2) | 13 (0.3) | 29 (0.2) |

| Conserved | 10 654 (89.1) | 2826 (73.5) | 13 382 (98.7) |

Discussion

Many previous studies in maize have provided interesting insights into heterotic patterns at epigenomic fields, including DNA methylation (Shen et al., 2012; Kawanabe et al., 2016; Lauss et al., 2018; Sinha et al., 2020), histone modification (He et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2017), and sRNA abundance (Groszmann et al., 2011; Greaves et al., 2016; Crisp et al., 2020). However, the recognized regulation by the epigenome of gene expression primarily occurs at the level of transcription. Therefore, we basically know nothing about whether post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression contributes to heterosis. If it does, what is the regulatory manner and how is it different from transcription? Meanwhile, it is well known that gene transcription cannot entirely determine protein abundance due to several post-transcriptional events such as alternative splicing, mRNA modification, translational efficiency, proper protein folding, and post-translational modification (de Sousa Abreu et al., 2009; Vogel and Marcotte, 2012; Wang et al., 2015; Vitrinel et al., 2019). In the present work, we conducted the integrated measurement of mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency in a maize F1 hybrid and its parental lines, and aimed to reveal the first genome-wide pattern of post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression underlying heterosis. Our results revealed remarkable dissimilarities of regulatory and heterotic patterns among mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency. Moreover, we discovered that genes participating in different biological pathways may undergo hierarchical regulation, which was coordinated by discrete combinations of three regulatory layers.

Serving as an epitranscriptomic layer of gene regulation, dynamic m6A modification has been demonstrated to play vital roles in a wide range of RNA metabolic processes (Roignant and Soller, 2017; Yang et al., 2018; Shen et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2020). We found that although the global abundance and configuration of m6A were comparable between hybrid and parents, the number of genes harboring m6A sites was increased in the hybrid (Fig. 1). However, an equivalent global abundance but increased number of m6A-modified genes seems controversial. This concern is well reconciled by the fact that the average intensity of m6A peaks was reduced in the F1 hybrid compared with the two parental lines, suggesting that m6A modification may post-transcriptionally fine-tune expression of a greater number of genes in the hybrid (Fig. 1). This provides the first hint of the prospective importance of m6A modification in the formation of heterosis. Secondly, the percentage of non-additive m6A-modified genes is extraordinarily higher than that of mRNA abundance and translational efficiency (Fig. 3). It has been recognized that non-additive gene activity can be the major force driving the formation of heterosis (Li et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2019). Therefore, although the exact biological effect of m6A sites on each individual gene must vary gene-by-gene, the active involvement of m6A modification in heterosis is hypothetically conceivable.

Numerous previous studies have shown that the transcription of a series of stimulus-responsive genes was up-regulated in hybrids (Groszmann et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2015). Consistently, we found that the pathway of response to stimulus was strikingly enriched in the group exhibiting an increased level of mRNA. However, surprisingly, this group of genes also displayed reduced translational efficiency, indicating that although up-regulated for mRNA abundance, the cellular activity of these stress-responsive genes might be substantially attenuated at the translation level (Fig. 5). This raises two intriguing questions of how this antagonistic pattern of up-regulated transcription but down-regulated translation is fulfilled and to what extent it contributes to heterosis. Our previous study has indicated that the excessive extent of m6A modification may inhibit the translational status in maize (Luo et al., 2020), and therefore we originally speculated that m6A modification may play a role in this process. However, this assumption was principally ruled out because the level of m6A modification in this group was fairly low, meaning that the other alternative post-transcriptional process must operate specifically to reduce translational efficiency of these stress-responsive genes. In addition, many previous studies have suggested that the increased transcription of stress-responsive genes may be attributed to enhanced stress tolerant in the hybrid (Groszmann et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2015). If this is true, why does it exhibit the suppression of translational efficiency? We hypothesize one likelihood is that decreased translational efficiency may constrain the production of proteins encoded by these stress-responsive genes, consequently maintaining the homeostasis of gene activity to fulfil the biological balance between plant growth and stress tolerance. This trade-off phenomenon has been well documented in many important early works (Chapin, 1991; Skirycz et al., 2010; Skirycz and Inze, 2010). In this scenario, the increased transcription of stress-responsive genes may be beneficial in the resilience of plants to environmental stress. However, the attenuated translation would likely optimize fitness costs associated with defense to promote plant growth.

Unlike the stress-responsive pathway, genes linked with photosynthesis, metabolic, translation, and nucleosome assembly pathways showed constitutively high levels of mRNA abundance and translational efficiency (Fig. 5). Apparently, these pathways have housekeeping functions, and the superior activity is critically needed for the rapid growth and development of the hybrid plant. In contrast, genes involved in the transcription pathway showed contrasted patterns with a low level of mRNA abundance but a high level of translational efficiency (Fig. 5). Interestingly, genes related to the establishment and maintenance of the epigenome, i.e. DNA methylation and histone modification, displayed a high level of m6A modification, but low levels of both mRNA abundance and translational efficiency, implying that there may exist some types of crosstalk between the epigenome and the epitranscriptome, which has been recently suggested in human cells (Huang et al., 2019) and Arabidopsis (Shim et al., 2020) (Fig. 5). Therefore, if and how this crosstalk contributes to the formation of heterosis deserves further investigation.

In sum, we describe the first parallel analysis of mRNA abundance, m6A modification, and translational efficiency profiles in a hybrid and its parental lines. We found many unique features of m6A modification and translational efficiency in the hybrid when compared with mRNA abundance, and demonstrated that post-transcriptional controls on gene expression may actively contribute to heterosis in maize. We further identified that gene expression of different biological pathways was under hierarchical control, which was coordinated by three regulatory layers, highlighting that transcriptional and post-transcriptional controls on gene action run together to establish the molecular basis of heterosis. Therefore, our study adds a new dimension to the exploration of core mechanisms underlying heterosis.

Supplementary data

The following supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Fig. S1. The repeatability between two biological replicates for RNA-seq data, m6A-seq data, and polysome profiling data in the hybrid.

Fig. S2. RT-qPCR validation of eight genes at the mRNA level in F1 hybrid B73×Mo17 and its two parental lines, B73 and Mo17.

Fig. S3. RT-qPCR validation of eight genes at the m6A level in F1 hybrid B73×Mo17 and its two parental lines, B73 and Mo17.

Fig. S4. RT-qPCR validation of selected eight genes at the level of translational efficiency in F1 hybrid B73×Mo17 and its two parental lines, B73 and Mo17.

Fig. S5. Pie-chart depicting the percentage of m6A peaks within six transcript segments in the hybrid.

Fig. S6. Comparison of gene numbers containing multiple m6A peaks between hybrid and parents.

Table S1. The list of primers used in the study.

Table S2. The list of m6A-modified genes showing peak summit locations, mRNA abundance, m6A level, and translational efficiency in the maize F1 hybrid B73×Mo17.

Table S3. The heterotic types of non-additive genes at the level of m6A modification in the maize F1 hybrid B73×Mo17.

Table S4. The heterotic types of non-additive genes at the level of mRNA abundance in the maize F1 hybrid B73×Mo17.

Table S5. The heterotic types of non-additive genes at the level of translational efficiency in the maize F1 hybrid B73×Mo17.

Table S6. Significantly enriched Gene Ontology (GO) terms for all eight clusters identified in Fig. 5.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the members of our laboratories for helpful discussions and assistance during this project. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0101201 and 2017YFD0101104 to Y.H.).

Author contributions

GFJ and YH conceived and supervised the project; JHL and MW conducted experiments and performed bioinformatics and statistical analyses; manuscript was prepared by JHL and YH. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

All the raw data for F1 hybrid B73×Mo17 have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under accession number GSE155947. The raw data for parental lines B73 and Mo17 have been published and under accession number GSE124543.

References

- Alonso-Peral MM, Trigueros M, Sherman B, Ying H, Taylor JM, Peacock WJ, Dennis ES. 2017. Patterns of gene expression in developing embryos of Arabidopsis hybrids. The Plant Journal 89, 927–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SJ, Kramer MC, Gosai SJ, et al. . 2018. N6-methyladenosine inhibits local ribonucleolytic cleavage to stabilize mRNAs in Arabidopsis. Cell Reports 25, 1146–1157.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arribas-Hernandez L, Bressendorff S, Hansen MH, Poulsen C, Erdmann S, Brodersen P. 2018. An m6A-YTH module controls developmental timing and morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 30, 952–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldauf JA, Marcon C, Paschold A, Hochholdinger F. 2016. Nonsyntenic genes drive tissue-specific dynamics of differential, nonadditive, and allelic expression patterns in maize hybrids. Plant Physiology 171, 1144–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y, Hu G, Grover CE, Conover J, Yuan D, Wendel JF. 2019. Unraveling cis and trans regulatory evolution during cotton domestication. Nature Communications 10, 5399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartosovic M, Molares HC, Gregorova P, Hrossova D, Kudla G, Vanacova S. 2017. N6-methyladenosine demethylase FTO targets pre-mRNAs and regulates alternative splicing and 3′ -end processing. Nucleic Acids Research 45, 11356–11370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berriz GF, Beaver JE, Cenik C, Tasan M, Roth FP. 2009. Next generation software for functional trend analysis. Bioinformatics 25, 3043–3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchler JA, Auger DL, Riddle NC. 2003. In search of the molecular basis of heterosis. The Plant Cell 15, 2236–2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchler JA, Yao H, Chudalayandi S, Vaiman D, Veitia RA. 2010. Heterosis. The Plant Cell 22, 2105–2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodi Z, Zhong S, Mehra S, Song J, Graham N, Li H, May S, Fray RG. 2012. Adenosine methylation in Arabidopsis mRNA is associated with the 3′ end and reduced levels cause developmental defects. Frontiers in Plant Science 3, 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin FS, III. 1991. Integrated responses of plants to stress: a centralized system of physiological responses. BioScience 41, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Crisp PA, Hammond R, Zhou P, et al. . 2020. Variation and inheritance of small RNAs in maize inbreds and F1 hybrids. Plant Physiology 182, 318–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa Abreu R, Penalva LO, Marcotte EM, Vogel C. 2009. Global signatures of protein and mRNA expression levels. Molecular Biosystems 5, 1512–1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, et al. . 2012. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 485, 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X, Fang T, Liu Y, et al. . 2020. Global profiling of N6-methyladenosine methylation in maize callus induction. The Plant Genome 13, e20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan HC, Wei LH, Zhang C, Wang Y, Chen L, Lu Z, Chen PR, He C, Jia G. 2017. ALKBH10B is an RNA N6-methyladenosine demethylase affecting Arabidopsis floral transition. The Plant Cell 29, 2995–3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves IK, Eichten SR, Groszmann M, Wang A, Ying H, Peacock WJ, Dennis ES. 2016. Twenty-four-nucleotide siRNAs produce heritable trans-chromosomal methylation in F1 Arabidopsis hybrids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 113, E6895–E6902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groszmann M, Gonzalez-Bayon R, Lyons RL, Greaves IK, Kazan K, Peacock WJ, Dennis ES. 2015. Hormone-regulated defense and stress response networks contribute to heterosis in Arabidopsis F1 hybrids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 112, E6397–E6406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groszmann M, Greaves IK, Albertyn ZI, Scofield GN, Peacock WJ, Dennis ES. 2011. Changes in 24-nt siRNA levels in Arabidopsis hybrids suggest an epigenetic contribution to hybrid vigor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 108, 2617–2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Yang S, Rupe M, Hu B, Bickel DR, Arthur L, Smith O. 2008. Genome-wide allele-specific expression analysis using Massively Parallel Signature Sequencing (MPSSTM) reveals cis- and trans-effects on gene expression in maize hybrid meristem tissue. Plant Molecular Biology 66, 551–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haussmann IU, Bodi Z, Sanchez-Moran E, Mongan NP, Archer N, Fray RG, Soller M. 2016. m6A potentiates Sxl alternative pre-mRNA splicing for robust Drosophila sex determination. Nature 540, 301–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G, Chen B, Wang X, et al. . 2013. Conservation and divergence of transcriptomic and epigenomic variation in maize hybrids. Genome Biology 14, R57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochholdinger F, Baldauf JA. 2018. Heterosis in plants. Current Biology 28, R1089–R1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoecker N, Lamkemeyer T, Sarholz B, et al. . 2008. Analysis of nonadditive protein accumulation in young primary roots of a maize (Zea mays L.) F1-hybrid compared to its parental inbred lines. Proteomics 8, 3882–3894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang AZ, Delaidelli A, Sorensen PH. 2020. RNA modifications in brain tumorigenesis. Acta Neuropathologica Communications 8, 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Weng H, Sun W, et al. . 2018. Recognition of RNA N6-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nature Cell Biology 20, 285–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Weng H, Zhou K, et al. . 2019. Histone H3 trimethylation at lysine 36 guides m6A RNA modification co-transcriptionally. Nature 567, 414–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Yang S, Gong J, et al. . 2015. Genomic analysis of hybrid rice varieties reveals numerous superior alleles that contribute to heterosis. Nature Communications 6, 6258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Schmidt RH, Zhao Y, Reif JC. 2017. A quantitative genetic framework highlights the role of epistatic effects for grain-yield heterosis in bread wheat. Nature Genetics 49, 1741–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Peluso P, Shi J, et al. . 2017. Improved maize reference genome with single-molecule technologies. Nature 546, 524–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juntawong P, Girke T, Bazin J, Bailey-Serres J. 2014. Translational dynamics revealed by genome-wide profiling of ribosome footprints in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 111, E203–E212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawanabe T, Ishikura S, Miyaji N, et al. . 2016. Role of DNA methylation in hybrid vigor in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 113, E6704–E6711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2015. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nature Methods 12, 357–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger F, Andrews SR. 2016. SNPsplit: allele-specific splitting of alignments between genomes with known SNP genotypes. F1000Research 5, 1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S, Phillippy A, Delcher AL, Smoot M, Shumway M, Antonescu C, Salzberg SL. 2004. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biology 5, R12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauss K, Wardenaar R, Oka R, van Hulten MHA, Guryev V, Keurentjes JJB, Stam M, Johannes F. 2018. Parental DNA methylation states are associated with heterosis in epigenetic hybrids. Plant Physiology 176, 1627–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei L, Shi J, Chen J, et al. . 2015. Ribosome profiling reveals dynamic translational landscape in maize seedlings under drought stress. The Plant Journal 84, 1206–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lence T, Akhtar J, Bayer M, et al. . 2016. m6A modulates neuronal functions and sex determination in Drosophila. Nature 540, 242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Chen YS, Ping XL, et al. . 2017. Cytoplasmic m6A reader YTHDF3 promotes mRNA translation. Cell Research 27, 444–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Li Y, Moose SP, Hudson ME. 2015. Transposable elements, mRNA expression level and strand-specificity of small RNAs are associated with non-additive inheritance of gene expression in hybrid plants. BMC Plant Biology 15, 168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Shi J, Yu L, Zhao X, Ran L, Hu D, Song B. 2018. N6-methyl-adenosine level in Nicotiana tabacum is associated with tobacco mosaic virus. Virology Journal 15, 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Qin P, Zhang X, et al. . 2020. Divergent selection and genetic introgression shape the genome landscape of heterosis in hybrid rice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 117, 4623–4631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippman ZB, Zamir D. 2007. Heterosis: revisiting the magic. Trends in Genetics 23, 60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Wang Q, Chen M, et al. . 2020. Genome-wide identification and analysis of heterotic loci in three maize hybrids. Plant Biotechnology Journal 18, 185–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Dai Q, Zheng G, He C, Parisien M, Pan T. 2015. N6-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature 518, 560–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Zhou KI, Parisien M, Dai Q, Diatchenko L, Pan T. 2017. N6-methyladenosine alters RNA structure to regulate binding of a low-complexity protein. Nucleic Acids Research 45, 6051–6063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biology 15, 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo JH, Wang Y, Wang M, Zhang LY, Peng HR, Zhou YY, Jia GF, He Y. 2020. Natural variation in RNA m6A methylation and its relationship with translational status. Plant Physiology 182, 332–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Perez M, Aparicio F, López-Gresa MP, Bellés JM, Sánchez-Navarro JA, Pallás V. 2017. Arabidopsis m6A demethylase activity modulates viral infection of a plant virus and the m6A abundance in its genomic RNAs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 114, 10755–10760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer KD. 2018. m6A-mediated translation regulation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 1862, 301–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer KD, Jaffrey SR. 2017. Rethinking m6A readers, writers, and erasers. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 33, 319–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer KD, Patil DP, Zhou J, Zinoviev A, Skabkin MA, Elemento O, Pestova TV, Qian SB, Jaffrey SR. 2015. 5′ UTR m6A promotes cap-independent translation. Cell 163, 999–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer KD, Saletore Y, Zumbo P, Elemento O, Mason CE, Jaffrey SR. 2012. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell 149, 1635–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Z, Zhang T, Qi Y, Song J, Han Z, Ma C. 2020. Evolution of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methylome mediated by genomic duplication. Plant Physiology 182, 345–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris K, Barker GC, Walley PG, Lynn JR, Finch-Savage WE. 2016. Trait to gene analysis reveals that allelic variation in three genes determines seed vigour. New Phytologist 212, 964–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschold A, Jia Y, Marcon C, et al. . 2012. Complementation contributes to transcriptome complexity in maize (Zea mays L.) hybrids relative to their inbred parents. Genome Research 22, 2445–2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendleton KE, Chen B, Liu K, Hunter OV, Xie Y, Tu BP, Conrad NK. 2017. The U6 snRNA m6A methyltransferase METTL16 regulates SAM synthetase intron retention. Cell 169, 824–835.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertea M, Pertea GM, Antonescu CM, Chang TC, Mendell JT, Salzberg SL. 2015. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nature Biotechnology 33, 290–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roignant JY, Soller M. 2017. m6A in mRNA: an ancient mechanism for fine-tuning gene expression. Trends in Genetics 33, 380–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romisch-Margl L, Spielbauer G, Schützenmeister A, Schwab W, Piepho HP, Genschel U, Gierl A. 2010. Heterotic patterns of sugar and amino acid components in developing maize kernels. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 120, 369–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T, He C. 2017a. Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell 169, 1187–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roundtree IA, Luo GZ, Zhang Z, et al. . 2017. b. YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N6-methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. eLife 6, e31311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzicka K, Zhang M, Campilho A, et al. . 2017. Identification of factors required for m6A mRNA methylation in Arabidopsis reveals a role for the conserved E3 ubiquitin ligase HAKAI. New Phytologist 215, 157–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scutenaire J, Deragon JM, Jean V, Benhamed M, Raynaud C, Favory JJ, Merret R, Bousquet-Antonelli C. 2018. The YTH domain protein ECT2 is an m6A reader required for normal trichome branching in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 30, 986–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao L, Xing F, Xu C, et al. . 2019. Patterns of genome-wide allele-specific expression in hybrid rice and the implications on the genetic basis of heterosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 116, 5653–5658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, He H, Li J, et al. . 2012. Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression changes in two Arabidopsis ecotypes and their reciprocal hybrids. The Plant Cell 24, 875–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Liang Z, Gu X, Chen Y, Teo ZW, Hou X, Cai WM, Dedon PC, Liu L, Yu H. 2016. N6-methyladenosine RNA modification regulates shoot stem cell fate in Arabidopsis. Developmental Cell 38, 186–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Liang Z, Wong CE, Yu H. 2019. Messenger RNA modifications in plants. Trends in Plant Science 24, 328–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Sun S, Hua S, Shen E, Ye CY, Cai D, Timko MP, Zhu QH, Fan L. 2017. Analysis of transcriptional and epigenetic changes in hybrid vigor of allopolyploid Brassica napus uncovers key roles for small RNAs. The Plant Journal 91, 874–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Wang X, Lu Z, Zhao BS, Ma H, Hsu PJ, Liu C, He C. 2017. YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N6-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Research 27, 315–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim S, Lee HG, Lee H, Seo PJ. 2020. H3K36me2 is highly correlated with m6A modifications in plants. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 62, 1455–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha P, Singh VK, Saxena RK, et al. . 2020. Genome-wide analysis of epigenetic and transcriptional changes associated with heterosis in pigeonpea. Plant Biotechnology Journal 18, 1697–1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skirycz A, De Bodt S, Obata T, et al. . 2010. Developmental stage specificity and the role of mitochondrial metabolism in the response of Arabidopsis leaves to prolonged mild osmotic stress. Plant Physiology 152, 226–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skirycz A, Inze D. 2010. More from less: plant growth under limited water. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 21, 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slobodin B, Han R, Calderone V, Vrielink JAFO, Loayza-Puch F, Elkon R, Agami R. 2017. Transcription impacts the efficiency of mRNA translation via co-transcriptional N6-adenosine methylation. Cell 169, 326–337.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer NM, Stupar RM. 2007. Allelic variation and heterosis in maize: how do two halves make more than a whole? Genome Research 17, 264–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer NM, Ying K, Fu Y, et al. . 2009. Maize inbreds exhibit high levels of copy number variation (CNV) and presence/absence variation (PAV) in genome content. PLoS Genetics 5, e1000734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupar RM, Springer NM. 2006. Cis-transcriptional variation in maize inbred lines B73 and Mo17 leads to additive expression patterns in the F1 hybrid. Genetics 173, 2199–2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Zhou Y, Chen J, et al. . 2018. Extensive intraspecific gene order and gene structural variations between Mo17 and other maize genomes. Nature Genetics 50, 1289–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson-Wagner RA, Jia Y, DeCook R, Borsuk LA, Nettleton D, Schnable PS. 2006. All possible modes of gene action are observed in a global comparison of gene expression in a maize F1 hybrid and its inbred parents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 103, 6805–6810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitrinel B, Koh HWL, Mujgan Kar F, Maity S, Rendleman J, Choi H, Vogel C. 2019. Exploiting interdata relationships in next-generation proteomics analysis. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 18, S5–S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel C, Marcotte EM. 2012. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nature Reviews. Genetics 13, 227–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Lu Z, Gomez A, et al. . 2014. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 505, 117–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, Lu Z, Han D, Ma H, Weng X, Chen K, Shi H, He C. 2015. N6-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell 161, 1388–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei LH, Song P, Wang Y, Lu Z, Tang Q, Yu Q, Xiao Y, Zhang X, Duan HC, Jia G. 2018. The m6A reader ECT2 controls trichome morphology by affecting mRNA stability in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 30, 968–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao W, Adhikari S, Dahal U, et al. . 2016. a. Nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Molecular Cell 61, 507–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Z, Zou Q, Liu Y, Yang X. 2016b. Genome-wide assessment of differential translations with ribosome profiling data. Nature Communications 7, 11194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Li B, Zheng XY, Li J, Yang M, Dong X, He G, An C, Deng XW. 2015. Salicylic acid biosynthesis is enhanced and contributes to increased biotrophic pathogen resistance in Arabidopsis hybrids. Nature Communications 6, 7309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Hsu PJ, Chen YS, Yang YG. 2018. Dynamic transcriptomic m6A decoration: writers, erasers, readers and functions in RNA metabolism. Cell Research 28, 616–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue H, Nie X, Yan Z, Weining S. 2019. N6-methyladenosine regulatory machinery in plants: composition, function and evolution. Plant Biotechnology Journal 17, 1194–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Zhang YC, Liao JY, et al. . 2019. The subunit of RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase OsFIP regulates early degeneration of microspores in rice. PLoS Genetics 15, e1008120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Liu X, Gaikwad K, et al. . 2017. Mutations in eIF5B confer thermosensitive and pleiotropic phenotypes via translation defects in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Cell 29, 1952–1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, et al. . 2008. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biology 9, R137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Hu F, Zhang X, Wei Q, Dong J, Bo C, Cheng B, Ma Q. 2019. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals important roles of nonadditive genes in maize hybrid An’nong 591 under heat stress. BMC Plant Biology 19, 273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Yang Y, Sun BF, et al. . 2014. FTO-dependent demethylation of N6-methyladenosine regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipogenesis. Cell Research 24, 1403–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, et al. . 2013. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Molecular Cell 49, 18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S, Li H, Bodi Z, Button J, Vespa L, Herzog M, Fray RG. 2008. MTA is an Arabidopsis messenger RNA adenosine methylase and interacts with a homolog of a sex-specific splicing factor. The Plant Cell 20, 1278–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Tian S, Qin G. 2019. RNA methylomes reveal the m6A-mediated regulation of DNA demethylase gene SlDML2 in tomato fruit ripening. Genome Biology 20, 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu A, Greaves IK, Liu PC, Wu L, Dennis ES, Peacock WJ. 2016. Early changes of gene activity in developing seedlings of Arabidopsis hybrids relative to parents may contribute to hybrid vigour. The Plant Journal 88, 597–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Hu B, Becker C, Doğan ES, Berendzen KW, Weigel D, Liu C. 2017. Altered chromatin compaction and histone methylation drive non-additive gene expression in an interspecific Arabidopsis hybrid. Genome Biology 18, 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the raw data for F1 hybrid B73×Mo17 have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under accession number GSE155947. The raw data for parental lines B73 and Mo17 have been published and under accession number GSE124543.