Abstract

The diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in children is commonly accompanied by a diagnosis of sensory processing disorders. Abnormalities are usually reported in multiple sensory processing domains, showing a higher prevalence of unusual responses, particularly to tactile, auditory and visual stimuli. This paper discusses a novel robot-based framework designed to target sensory difficulties faced by children with ASD in a controlled setting. The setup consists of a number of sensory stations, together with two different robotic agents that navigate the stations and interact with the stimuli. These stimuli are designed to resemble real world scenarios that form a common part of one’s everyday experiences. Given the strong interest of children with ASD in technology in general and robots in particular, we attempt to utilize our robotic platform to demonstrate socially acceptable responses to the stimuli in an interactive, pedagogical setting that encourages the child’s social, motor and vocal skills, while providing a diverse sensory experience. A preliminary user study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of the proposed framework, with a total of 18 participants (5 with ASD and 13 typically developing) between the ages of 4 and 12 years. We derive a measure of social engagement, based on which we evaluate the effectiveness of the robots and sensory stations in order to identify key design features that can improve social engagement in children.

Keywords: Human-robot interaction, sensory processing disorder, autism spectrum disorder, socially assistive robots, social engagement

1. INTRODUCTION

Sensory abnormalities are reported to be central to the autistic experience. Anecdotal accounts [1-2] and clinical research [3-6] both provide sufficient evidence to support this notion. One study found that, in a sample size of 200, over 90% of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) had sensory abnormalities and showed symptoms in multiple sensory processing domains [4]. The symptoms include hyposensitivity, hypersensitivity, multichannel receptivity, processing difficulties and sensory overload. A higher prevalence of unusual responses, particularly to tactile, auditory and visual stimuli, is seen in children with ASD, when compared to their typically developing (TD) and developmentally delayed counterparts. The distress caused by some sensory stimuli can cause self-injurious and aggressive behaviors in children who may be unable to communicate their anguish [7]. Families also report that difficulties with sensory processing and integration can restrict participation in everyday activities, resulting in social isolation for them and their child [8] and impact social engagement [9-11].

Recent research efforts of our team have focused on developing robot-based tools to provide socio-emotional engagement to children with ASD. In our previous work, we developed an interactive robotic framework that included emotion-based robotic gestures and facial expressions to encourage music-based socio-emotional engagement [12-13]. The current work is an extension of these efforts where we use this framework in a pedagogical setting in which the robots model appropriate social responses to salient sensory stimuli that are a part of the everyday experience. This is done in a manner that is interactive and inclusive of the child, such that the robot and the child engage in a shared sensory experience. These stimuli are designed to resemble real world scenarios that form a typical part of one’s everyday experiences, such as uncontrolled sounds and light in a public space (e.g. a mall or a park), or tactile contact with clothing made of fabrics with different textures. These are only some of the everyday sensory stimuli that are used as inspiration to design the sensory stations in our setup for this study. Given the strong interest of children with ASD in technology in general and robots in particular [14], we attempt to utilize these robotic platforms to demonstrate socially acceptable responses to such stimulation in an interactive setting that encourages the child to become more receptive to experiences involving sensory stimulation.

With long-term exposure to the robots in this setting, we hypothesize that children will also be able to learn to communicate their feelings about discomforting sensory stimulation as modeled by the robots, instead of allowing uncomfortable experiences to escalate into extreme negative reactions, such as tantrums or meltdowns. However, since the targeted pedagogical effects can only be evaluated through a long-term study comprising multiple sessions with the participants over a longer period of time, the current paper focuses only on our preliminary evaluation of this framework as a tool to effectively engage the participants as well as model behaviors in ways that are easily interpreted by the participants. Therefore, the analysis and results presented in this paper relate exclusively to the socioemotional engagement of the participants while interacting with the robots, in order to evaluate the capability of our setup to engage the children. In the future, as we invite the same participants for further sessions, the collected data will enable us to evaluate the pedagogical efficacy of our framework as well.

Section 2 of this paper discusses previous studies that have focused on the alleviation of sensory processing difficulties in children with ASD and Section 3 describes the framework and its components in detail. Section 4 describes the preliminary user study, Section 5 explains the various assessment methods employed for the study and Section 6 discusses the metrics derived from the data analysis. The results are discussed in Section 7, and a discussion on these findings is given in Section 8. Section 9 presents a conclusion for this study.

2. BACKGROUND

Interventions to address sensory processing difficulties are among the services most often requested by parents of children with ASD [15-16]. The most popular of these is the combination of occupational therapy and sensory integration (OT/SI) [17-18]. However, until recently, there was little support for evidence-based research to support the practice of sensory integration, with the evidence in its favor being largely anecdotal. One of the first rigorous studies in this domain was conducted only recently in 2013 by Schaaf et. al., which found that children who received OT/SI therapy showed a reduced need for caregiver assistance in self-care and socialization [19].

In addition to conventional therapy methods, technologically enhanced intervention methods have also been widely adopted in ASD therapy due to the inherent interest in technology that is commonly reported in children with ASD [20-25]. The range of solutions is diverse, including video-based instruction, computer-aided instruction, mobile and virtual reality applications, as well as socially assistive robots [13][26-27]. However, such methods mostly target the core impairments that characterize ASD, with applications that focus on improving educational performances, emotional recognition and expression, social behaviors, and/or language and communication skills [28-30]. Relatively fewer research efforts have targeted improvements in sensory processing capabilities.

The MEDIATE (Multisensory Environment Design for an Interface between Autistic and Typical Expressiveness) project uses a multi-sensory, responsive environment designed to stimulate interaction and expression through visual, aural and vibrotactile means [31-32]. It is an adaptive environment that generates real-time stimuli such that low functioning children with ASD, who have no verbal communication, can get a chance to play, explore, and be creative in a controllable and safe space [33].

Several haptic interfaces have also been designed to facilitate therapy and provide non-invasive treatment alternatives [34]. These use vibrotactile, pneumatic, and heat pump actuation devices, designed to be worn on the arm, wrist, leg and chest areas [35]. These devices simulate touch by compressing to provide distributed pressure and emphasize the importance of tactile interactions for mental and emotional health. A vibrotactile gamepad has also been designed that allowed users to receive vibration patterns on the gamepad as they play video games [36]. This vibrotactile feedback corresponds to the events in the videogame but rather than alleviating sensory difficulties, it is primarily meant to convey emotions through the combination of sounds and vibration patterns in attempt to enhance the emotional competence of children with ASD.

In addition, a popular humanoid robot, KASPAR, has also been equipped with tactile sensors on its cheeks, torso, both arms, palms and at the back of the hands and feet [37-38] to test whether appropriate physical social interactions can be taught to children with ASD. It was shown that the robot, by providing appropriate feedback to tactile contact from the children, such as exclaiming when pinched or grabbed by the children, was able to train them to modulate the force they used while touching others [39].

Given the lack of robot-based studies targeting sensory processing difficulties and the mounting evidence emphasizing the need for sensory integration, we have directed our efforts towards this domain. As already stated, our team previously developed an interactive robotic framework that includes emotion-based robotic gestures and facial expressions, which are used to generate appropriate emotional and social behaviors for multi-sensory therapy [12][40]. However, the current study is a step forward in evaluating this design through a preliminary user study that assesses the ability of the framework to maintain children’s engagement and to model appropriate responses to sensory stimulation that are easily understood by the children. The following sections will explain these in detail.

3. THE FRAMEWORK

3.1. Design Considerations

When designing the interaction between the robots and the children, we took under consideration several factors pertaining to the appeal of the interaction, the purpose of the activity and the limitations imposed by sensitivity of the children toward sensory stimulation and the capabilities of the robots. Table 1 summarizes these design considerations.

Table 1.

Design considerations for child-robot interaction design.

| Design consideration | Description |

|---|---|

| Choice of robots | The robots must not be too large in size in order to prevent children from being intimidated by them. They must also be capable of expressing emotions through different modalities such as facial expressions, gestures and speech. The robots must also be friendly in order to form a rapport with the children. |

| Appeal of the interaction | The activity being conducted must also be able to maintain a child’s interest through the entire length of the interaction. This implies that the duration of the activity, as well as the content must be appealing to the children. |

| Choice of scenarios for sensory stimulation | The sensory station scenarios must be designed to be relatable to the children such that they are able to draw the connection between the stimulation presented to the robots and that experienced by them in their everyday lives. |

| Interpretability of robot actions | The robot actions must be simple and easy to understand for children in the target age range. The gestures, speech, facial expressions and body language must be combined to form meaningful and easily interpretable behaviors. |

| Choice of emotions expressed by robots | The emotion library of the robots must be large enough to effectively convey different reactions to the stimulation but also simple enough to be easily understood by the children. |

To address these concerns, we first chose two small robots: a humanoid robot and an iPod-based robot with a custom-designed penguin avatar. The humanoid robot was programmed to express emotions mostly through gestures and speech, while the iPod-based robot mainly used facial expressions, paired with sound effects and movements allowed by the treads on which it was mounted. Details on these two platforms are given in Section 3.2.

In general, the activity was designed to last between 8-10 minutes per robot, unless the children required or specifically asked for certain actions to be re-performed, in which case it could take longer. The interactions were also designed to be interactive, with the robot directly addressing the children and explicitly requesting their participation. In this manner, the activity was inclusive of the children and ensured that they shared this sensory experience with the robots instead of having to merely observe their behaviors.

The station scenarios used in this interaction were inspired by everyday experiences, in order to expose the child to common sensory stimuli, some indirectly (from observing the robots) and some directly (when robots explicitly ask for the child’s participation). The stimuli are designed to be appealing and not overwhelming for the children. However, it was ensured that immediate adjustments to modify the stimuli were possible in case a child had a lower threshold for sensory stimulation than estimated. For example, the volume of the music could be lowered, and the direction of the light beam could be changed in real-time as required.

The actions of the robots were also designed to depict simple but meaningful behaviors, combining all available modalities of emotional expression, such as movement, speech and facial expressions. The responses of the robots were designed to be expressive, clear and straightforward so as to facilitate interpretation in the context of the scenario being presented at the given sensory station.

The emotion library of the iPod-based robot spanned 20 different emotion states. This was a part of our previous work [41], the goal of which was to develop emotionally expressive robotic agents. These emotions were represented along a valence-arousal scale, as determined by Russell’s Circumplex model [42] shown in Fig. 1. These were chosen to incorporate the 6 basic emotions [43], along with other emotion states we deemed most relevant in the context of an interaction involving sensory stimulation. The above applied mainly to the iPod-based robot, which responded to the stimuli with combinations of these emotions through facial expressions and accompanying sound effects. For the humanoid robot, the reactions comprised mostly of gestures and speech, due to which explicit emotional expressions, though programmed into the robot, were not directly utilized. Additional details on the emotional capabilities of each robot are presented in Section 3.2.

Fig. 1.

Russell's Circumplex model of emotion [42].

3.2. Robotic Platforms

As mentioned, two different robots were employed for this study: the humanoid robot, Robotis Mini (from Robotis) and the iPod-based robot, Romo (from Romotive). The two robots and their heights in inches are shown in Fig. 2. Since Mini communicated through gestures and speech, its responses to the sensory stimulation resembled natural human-human communication more closely than those of Romo, which used relatively primitive means of communication, like facial expressions, sound effects and movements. Therefore, the reactions from Romo comprised of explicit emotional expressions joined one after another to form meaningful responses, whereas Mini could express its responses meaningfully without acting out explicit emotions. In addition to the routines that both the robots were programmed to perform at each of the 5 sensory stations, both robots were capable of expressing individual emotions as well.

Fig. 2.

Mini (L) and Romo (R).

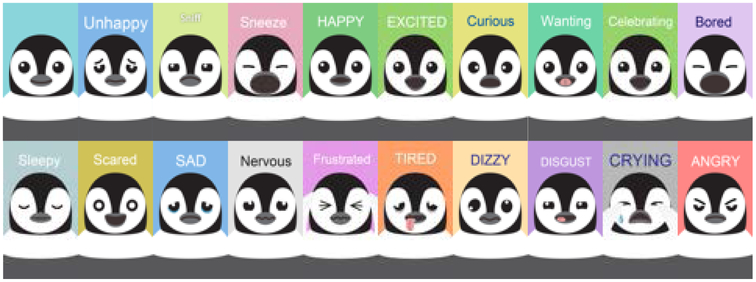

The 20 expressions that were programmed into Romo as animations are as follows (shown in Fig. 3): neutral, unhappy, sniff, sneeze, happy, excited, curious, wanting, celebrating, bored, sleepy, scared, sad, nervous, frustrated, tired, dizzy, disgust, crying and angry. It must be noted that although sneeze, wanting and sniff are not emotions, they were chosen for their utility in portraying certain physical states (such as sickness), as well as for aptly depicting responses to certain stimuli. The animation for each emotion was accompanied with a dedicated background color, as well as complementary changes in the tilt angle of the iPod, and circular or back-and-forth movements of the treads upon which it was mounted in order to further facilitate emotional expression [40][44]. It must be pointed out here that the penguin character and the emotion animations were custom-designed and developed by our team as a part of our previous work [41]. Mini was also programmed for the same emotional expressions, some of which are shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 3.

The 20 emotional expressions of Romo.

Fig. 4.

Emotional expressions of Mini (L-R): dizzy, happy, scared, and frustrated.

Both robots were controlled individually through their own interfaces. Mini was controlled via Bluetooth through a custom-designed user interface on an Android tablet. Romo was operated through a server, which triggered a custom-designed user interface once a connection was established with the robot [41]. Based on the selected action, a routine that included both the animations and physical movements was then autonomously executed by Romo. Both interfaces implemented the sensory station-based actions in additional to navigational features and other miscellaneous features. The actions of both robots could be manually selected by an instructor based on the children’s responses to these actions, in order to adapt to their needs. For example, the instructor could repeat a robot action if the child was distracted or interrupted by a pressing physical need (such as a runny nose).

3.3. Sensory Stations and Setup

The setup was composed of six different stations, presenting unique scenarios to stimulate each of the visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory and tactile senses. The stations were arranged in a fixed sequence: 1) Seeing Station, 2) Hearing Station, 3) Smelling Station, 4) Tasting Station, 5) Touching Station, and 6) Celebration Station. These stations were set on a tabletop, 30 inches wide and 60 inches long, placed in the middle of a room. The distances between the stations were as depicted in Fig. 5. The room had glass walls and some workstations set up along its perimeter.

Fig. 5.

Setup of the sensory stations.

The stimuli and station setup are described as follows:

Children with ASD often exhibit atypical visual behavior in attempt to either avoid visual input or to seek additional visual stimuli. Therefore, it is common to find them covering their eyes at bright lights or twisting fingers in front of their eyes [7]. At the Seeing Station, we emulated visual stimulus by placing a flashlight inside a lidded box constructed from a LEGO Mindstorm EV3 kit [45]. The front side of the box had an IR sensor that opened the lid when it detected movement in its proximity and the flashlight directed a bright beam of light in the direction of the approaching robot. This formed the visual stimulus at this station.

Atypical processing of audio stimuli is seen to manifest in the form of unusual behavioral responses commonly observed in children on the autism spectrum [4]. These behaviors include covering of the ears to seemingly benign sounds such as from the vacuum cleaner and the blender. Furthermore, if affected individuals learn to avoid the auditory input that they perceive as unpleasant, it could curtail the learning that comes from listening to the sounds from one’s environment [7]. To circumvent this problem, a Hearing Station was designed to provide an auditory stimulus in the form of music played by a Bluetooth speaker. For this study, we played “Llena de Plena” [46], as cheerful dance music to make up the auditory stimulus.

Though olfactory sensitivity in ASD has not been as widely researched, substantial anecdotal evidence supports heightened olfactory perception in individuals with ASD. An example includes accounts of individuals with ASD refusing to walk on grass because they found the smell overpowering [2]. Experimental reports also suggest heightened olfaction in ASD individuals [47]. In attempt to enable such individuals to become accustomed to smells they are likely to encounter regularly but find overwhelming, a Smelling Station was designed to provide olfactory stimulus in the form of scented artificial flowers inside a flowerpot. The scent could be modified on a case-by-case basis.

A widely reported attribute of ASD behavior is selective dietary habits [48-49], which can directly impact the nutritional intake in growing children. Factors such as smell, texture, color, and temperature can all contribute to food selectivity. The Tasting Station was designed to encourage diversity in food preferences by presenting a variety of food options. It had two small plastic plates with two different food items that could be modified to match every child’s likes and dislikes. These items formed the gustatory stimulus at this station.

Tactile sensitivity is also commonly reported as a symptom of ASD. Intolerance of certain textures and aversion to certain fabrics is commonly found [50][6], in addition to overreactions to cold, heat, itches or even being touched by other people [51-52]. Therefore, to encourage tolerance of various textures, a soft red blanket and a bowl of sand (with golden stars hidden inside it) were used as the tactile stimuli at the Touching Station.

3.4. Sensory Station Activity

The sensory scenarios used in this study were designed to closely resemble situations that children would encounter frequently in their everyday lives, hence making them relatable and easy to interpret. Given their strong interest in technology, we attempted to leverage the ability of our robots to elicit a higher level of socio-emotional engagement from these children. The robots are used in this sensory setting to demonstrate socially acceptable responses to stimulation to encourage children to become more receptive to a variety of sensory experiences, as well as to effectively communicate their feelings if the experiences cause them discomfort. As will become clear from the description of the actions of the robots at each sensory station in Table 2, the activity was designed to be interactive, with the robots sharing the sensory experience with the children in order to sustain their engagement. The stations were arranged in the fixed sequence described in Section 3.3 for every session.

Table 2.

Robot behaviors in the sensory station activity.

| Romo | Mini |

|---|---|

| Greeting/Introduction | |

| [No introduction] |

|

| Seeing Station | |

|

[walks to the lidded box]

|

| Hearing Station | |

|

[walks to the speaker]

|

| Smelling Station | |

| 1. Slowly approaches the flower pot Tilts the display in the direction of the flowers [Plays the sneeze animation and retreats to convey displeasure] |

[walks to the flower pot]

|

| Tasting Station | |

| 1. Approaches the first plate of food [Plays the nervous/disgust routine, tilts away and retreats from the plate quickly] Approaches the second plate of food [Plays the curious/wanting/happy routine with brisk to-and-fro movements to convey pleasure] |

[walks to the two plates of food]

I think I like this food the best. |

| Touching Station | |

| 1. Approaches the blanket Moves on top of it Pauses and plays the curious/sleepy routine to convey that the blanket is comfortable and that it is taking a nap in it [sand bowl not used] |

[walks to the blanket] Wow, we’ve walked over to a blanket. This blanket looks very soft. I think I want to feel it. Can you help feel it with me? [waits for child to respond] Great! Let’s walk over and touch the blanket. [moves closer] [bends down to touch the blanket and then rubs it] It feels very soft and fluffy, like a kitten! What soft animal does it remind you of? [stands back up and waits for child to respond] [walks over to the bowl of sand] [points to the bowl] Hey, I think I lost my toys in the sand. Can you help me find them? [waits for child to retrieve the golden stars] Thank you! |

| Celebration | |

| 1. Moves to the middle of the table Plays the happy/excited/celebration routine, changes tilt angles rapidly and spins around in circles to convey excitement | 1. Yay! We’re all done! Let’s celebrate by rolling around! [performs somersault] [gets up on its feet, takes a few steps forward and then balances itself on one foot] |

The robots show both positive and negative responses at some of the sensory stations with the aim of demonstrating to the children how to communicate their feelings even when experiencing discomforting or unfavorable sensory stimulation, instead of allowing the negative experience to escalate into a tantrum or meltdown. These negative reactions were designed not to be too extreme, so as to focus on the communication of one’s feelings rather than encouraging intolerance of the stimulation.

As listed in Table 2, the instructor made sure to pause between each dialog delivered by Mini so as to allow the child to respond before proceeding with the activity. The questions from Mini were meant to promote active participation from the children and keep them interested in the interaction.

It is also important to point out the intended purposes of demonstrated actions of the robots at each station:

Seeing Station: To effectively handle uncomfortable visual stimuli and to communicate discomfort instead of allowing it to manifest as extreme negative reactions (tantrums/meltdowns). This can be especially useful in controlled environments like cinemas and malls where light intensity cannot be fully regulated.

Hearing Station: To improve tolerance for sounds louder than those to which one is accustomed, to learn to not be overwhelmed by music, and to promote gross motor movements by encouraging dancing along to it.

This can be especially useful in uncontrolled environments like cinemas and malls where sounds cannot be fully regulated.

Smelling Station: To not react with extreme aversion to odors that may be disliked and to communicate the dislike instead. This can be useful for parents of children with ASD who are very particular about the smell of their food, clothes, and/or environments etc.

Tasting Station: To diversify food preferences instead of adhering strictly to the same ones. It must be pointed out that this goal is a long-term target that can only be achieved after the children have already interacted with the robots over several sessions. We anticipate that once the robots have formed a rapport with the child by liking and disliking the same foods as the child, it could start to deviate from those responses, hopefully encouraging the children to be more receptive to the foods their robot “friends” prefer. We plan to change to different food items in the future sessions to achieve this goal. While this remains our eventual target, this claim can only be validated through a long-term study; its mention here is meant only to provide the readers with an insight into the purpose of the station design.

Touching Station: To acclimate oneself to different textures by engaging in tactile interactions with different materials. This is especially useful for those children with ASD who may be sensitive to the texture of their clothing fabrics [50][6] and/or those who experience significant discomfort with wearables like hats and wrist watches etc.

Celebration Station: The celebration at the end was meant to convey a sense of shared achievement, while also encouraging the children to practice their motor and vestibular skills by imitating the celebration routines of the robots. Both robots are shown at the sensory stations in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

The robots at sensory stations.

Apart from the actions performed at the stations, the robots were also programmed with navigational capabilities, including the ability to move forward, backward, left and right for both robots. Mini had an additional feature of “getting up”, which was used if it took a fall while walking or if it met with an unexpected interaction initiated by the participant that required it to get back to a standing position. Romo was also programmed for the additional capability of spinning in a circle, which was useful for navigation purposes as well as to attract the attention of a distracted participant. The greeting/introduction was also not a part of a station action. These non-station actions were also meant to be engaging for the children, with either an interactive, social component (greeting) or a motion component (navigation/getting back up on the feet), without a focus on the modeling of responses to sensory stimulation.

4. USER STUDY

4.1. Participants

We invited a total of 13 TD and 9 ASD children to participate in this study. Of the 9 ASD participants, we were unable to collect data from 2 participants due to the severity of their conditions: both were non-vocal and had severe attentional difficulties due to which they were unable to remain inside the experiment room with the robots. Considering the design of the framework and robotic interactions, we expected that children within the elementary and middle school ages could benefit from this interaction and/or find it appealing, especially given the fact that the cognitive skills of children with ASD may be considerably different from their age-matched TD counterparts. One of the purposes of this study was to validate this proposition by measuring and comparing the social engagement of the participants through the course of their interaction with the robots. Our recruitment strategy involved recruiting from the general public through flyers and word-of-mouth in the metropolitan Washington, DC area. From this recruitment process, our inclusion criteria only required that participants were diagnosed with ASD, as such, we didn’t require parents to disclosure in-depth medical details.

Therefore, the target age range was set to 4-12 years. Data collected from 2 additional ASD participants, 3 and 15 years of age, was excluded from this paper since they fell outside this range. Hence, the TD group consisted of 13 participants, 7 male and 6 females, with a mean age of 7.08 years (SD = 2.565) and the ASD group consisted of 5 participants, all males, with a mean age of 8.2 years (SD = 1.095). The demographic details of the participants are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Demographic details of the participants.

| ID | Age | Gender | Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | M | TD |

| 2 | 4 | F | TD |

| 3 | 5 | F | TD |

| 4 | 11 | F | TD |

| 5 | 9 | M | TD |

| 6 | 10 | F | TD |

| 7 | 9 | M | TD |

| 8 | 5 | M | TD |

| 9 | 5 | M | TD |

| 10 | 5 | F | TD |

| 11 | 5 | M | TD |

| 12 | 5 | M | TD |

| 13 | 9 | M | TD |

| 14 | 7 | M | ASD |

| 15 | 8 | M | ASD |

| 16 | 10 | M | ASD |

| 17 | 8 | M | ASD |

| 18 | 8 | M | ASD |

4.2. Procedure

We recruited the two groups of participants for multiple sessions of child-robot interactions over a period of a few months, where each child would be allowed to visit maximum of 8 times in total. However, even though we have conducted multiple sessions with some of the participants, this paper presents only the single-session data collected from all participants.

All sessions were conducted individually, not in pairs or groups. The children were accompanied by their parent(s) who remained with them in the room throughout the session. They were given 5-7 minutes to explore the new environment and settle down. The parents were asked to sign the required consent forms and fill out the questionnaires (discussed in Section 5). The sessions were not strictly structured, in that the participants were only briefly instructed about play time with the robots. They were given no explicit directions about how to interact with the robots. They could sit in a chair or remain standing during the session, as they pleased. This method of providing minimal instructions was intentional since it facilitated a naturalistic interaction between the children and the robots. The size of the table and its placement in the room allowed the children to move around freely in order to ensure that they could view the robot from the front at every station (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

The setting used to conduct sessions with the participants.

In every session, the activity was first conducted with Romo, followed by Mini, and the stations were placed in the same fixed order as described in the previous section. The experiment design did not explicitly include a break between the 2 activities, but the participants were allowed to stop at any point if needed. Removing Romo from the setup and restarting the activity with Mini never took more than a minute. The control mechanisms of the robots and the stimuli design allowed for flexibility, such that an action could be repeated if the interaction was interrupted (for example, if a child had a runny nose or needed to use the restroom) or a stimulus could be adjusted if necessary (for example, the volume of the music could be lowered or increased at the Hearing Station).

A camcorder, mounted on a tripod, was placed at the end of the table, at an angle that ensured that the child and the robots always remained in its view. The footage was used for post-experimental analysis. The analysis presented in this paper was based only on the video data collected during the intervals of active participation.

5. ASSESSMENT METHODS

5.1. Video Coding

A behavioral coding software, Behavioral Observation Research Interactive Software (BORIS)[53] was used to annotate the behaviors of interest in the video data, as described in Section 5.2. Coding generated from the software were also used to derive evaluation metrics described in Section 6.

5.2. A Measure of Engagement

In order to derive a meaningful quantitative measure of engagement, we utilized several key behavioral traits of social interactions, including gaze focus, vocalizations and verbalizations, smile, triadic interactions, self-initiated interactions and imitation, as described in Table 4. These behaviors were selected because they have proven to be useful measures of social attention and social responsiveness from previous studies [54-65]. By coding the video data for these target behaviors, we were able to derive an engagement index as the indicator of every child’s varying social engagement throughout the interaction with the robots. The engagement index was computed as a sum of these factors, each with the same weight, such that the maximum value of the engagement index was 1.

Table 4.

Behaviors comprising the engagement index.

| Behavior | Description |

|---|---|

| Eye gaze focus | Deficits in social attention and establishing eye contact are two of the most commonly reported deficits in children with ASD. We therefore used the children’s gaze focus on the robots and/or the setup to mark the presence of this behavior. |

| Vocalizations/ verbalizations |

The volubility of utterances produced by children with ASD is low compared to their TD counterparts. Since communication is a core aspect of social responsiveness, the frequency and duration of the vocalizations and verbalizations produced by the children during the interaction is also important in computing the engagement index. |

| Smile | Smiling has also been established as an aspect of social responsiveness. We recorded the frequency and duration of smiles displayed by the children while interacting with the robots, as a contributing factor to the engagement index. |

| Triadic interactions | A triadic relationship involves three agents, including the child, the robot and a third person that may be the parent or the instructor. In this study, the robot acts as tool to elicit interactions between the child and other humans. An example of such interactions is the child sharing her excitement about the dancing robot by directing the parent’s attention to it. |

| Self-initiated interactions | Children with ASD prefer to play alone and make fewer social initiations compared to their peers. Therefore, we recorded the frequency and duration of the interactions with the robot initiated by the children as factors contributing to the engagement index. Examples of self-initiated interactions can include talking to the robots, attempting to feed the robots, guiding the robots to the next station etc. without any prompts from the instructors. |

| Imitation | Infants have been found to produce and recognize imitation from the early stages of development, and both these skills have been linked to the development of socio-communicative abilities. In this study, we monitored a child’s unprompted imitation of the robot behaviors as a measure of their engagement in the interaction. |

Each behavior contributed a factor of 1/6 to the engagement index. For example, for a participant observed to have a smile and gaze focus while interacting with Mini during the Tasting Station but only gaze focus following the end of the station, the engagement function was assigned a constant value of 1/6 + 1/6 = 1/3 for the entire duration of the station, and reduced to 1/6 immediately after its end. Any changes in engagement within an intervalof 1 second were detected and reflected in the engagement index function, as shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

A plot showing the changes in a participant’s engagement during the interaction with robots.

5.3. Questionnaires

As a tool to monitor long-term behavioral changes in the children participating in multiple sessions though the course of the study, we also designed 4 different questionnaires to gather parental reports of their progress. These mostly consisted of close-ended questions with response options on a seven-point Likert scale. The questions were related to the child’s general sensory processing abilities, in addition to the parent’s report on their interactions with the robots at specific sensory stations. Excerpts from these questionnaires are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Excerpts from questionnaires used to extract parental feedback.

| Questionnaire | Sample questions |

|---|---|

| Baseline |

|

| Pre-session |

|

| Post-session |

|

| Post-study |

|

A baseline assessment questionnaire evaluated the child’s sensory perception, as well as language, emotional, social and play skills prior to their participation in this study. This was completed by the parent only once before the participation began. The pre-session questionnaire had more focused questions about the same skills as in the baseline questionnaire and was filled out prior to every session that the child participated in through the course of this study. A post-session questionnaire was filled out upon completion of every individual session. This questionnaire contained questions specifically intended to elicit the parents’ feedback on the child’s interaction with the robots in that particular session. A post-study questionnaire contained questions related to the child’s overall experience through the course of the study. This was required to be filled out only once after all the child’s sessions had been completed.

While the pre- and post-session questionnaires monitored the child’s interaction with the robots in every individual session, the baseline and post-study questionnaires extracted a more comprehensive picture of the child’s overall progress with long-term interactions with our robots. Since we have only conducted single sessions with the participants so far, the analysis presented in this study does not include the data collected from these questionnaires but will be used in the future work that studies the long-term impact of interactions with this framework.

6. DATA ANALYSIS

6.1. Engagement Index and Evaluation criteria

The video coding results generated by BORIS contained timing and behavioral change information for every participant throughout the duration of their respective sessions. These results were run through a MATLAB script to compute the changing engagement index value as the normalized sum of target behaviors observed at one-second time intervals throughout the interaction. The plot shown in Fig. 8 depicts the engagement index value for one of the participants. The red plot marks the general engagement trend for this participant. In the station labels marked in red, “R” indicates Romo and “M” indicates Mini. Such plots were generated for all the participants in the study.

Additional layers of analysis were also generated. The same script also extracted information pertaining to the timing of the robot actions in response to which these engagement index values were generated. The yellow areas in Fig. 8 are the periods marking the sensory station actions of the robots. This allowed us to compare the effectiveness of each station in eliciting social engagement from the participants. In addition to the consolidated engagement index value, a breakdown in terms of the target behavior comprising this engagement was also derived. This allowed for a comparison of the frequency of observation of the different target behaviors and the stations responsible for eliciting them. A visualization of this is shown in Fig. 9. Station labels are omitted for legibility but are the same as in Fig. 8. As indicated, this particular participant initiated no interactions with the robot and showed no imitative behaviors. Finally, the engagement generated by each robot was also assessed individually and compared to study the social engagement potential of each robot in this sensory setting.

Fig. 9.

Plots depicting the changes in a participant’s engagement from each target behavior engagement during an interaction with robots.

6.2. Framework Evaluation Metrics

Using the method to derive continuous engagement index values as described above, several other metrics were also generated to evaluate various aspects of the design. First, the session comprising interactions with both robots was analyzed as a whole, resulting in consolidated engagement metrics. In addition, engagement resulting from each target behavior was also computed to study the contribution of each target behavior toward the engagement index. As an example, an engagement metric resulting from the vocalizations of participant X was computed as:

The next layer of analysis was obtained by isolating the engagement resulting from each robot and comparing the two metrics to evaluate their impact. Once again, an overall engagement index was obtained for each robot as an indicator of its performance throughout its interaction, in addition to a breakdown in terms of the target behaviors that comprise the engagement. The engagement metric for the interaction of participant X with Romo was calculated as:

Similarly, the engagement metric resulting from the vocalizations of participant X while interacting with Romo was calculated as:

Next, an analysis was performed to study the differences in engagement at each sensory station. This was analyzed separately for each robot so as to derive an understanding of the engagement potential of each station per robot. The engagement metric resulting from the Hearing station while participant X interacted with Mini was calculated as:

In addition, a breakdown of engagement at each station was obtained in terms of the elicited target behaviors and analyzed separately for each robot as well. This allowed for a finer-grain assessment of the capability of each station for eliciting the individual target behaviors. For example, the engagement metric resulting from the gaze of participant X at the Smelling station while interacting with Mini was calculated as:

These metrics enabled us to study different aspects of our framework and effectively evaluate the various design factors to achieve a comprehensive understanding of its potential, in addition to identifying areas requiring further improvement.

6.3. Individual and Group Analysis

All the afore-mentioned metrics were obtained for each individual participant. Data from participants was also consolidated to derive metrics to compare group performances as well. The following sections will present these metrics in detail.

6.4. Intercoder Reliability Assessment

To improve the reliability of the obtained results, the video coding was completed by three different coders, with the same analysis methods performed on the three sets of generated data. This included both individual and group analysis. The quality of the coding was assessed using intraclass correlation (ICC) of type (3,1), which is a popular method of determining coder’s agreement in behavioral sciences [66]. This value ranges between 0 and 1, and according to a guideline provided by Koo and Li [67], values between 0.7-0.9 are considered good, and those above 0.9 are considered excellent. The agreement score and the standard deviation of the engagement data provided by the three coders in this study was 0.8752 ± 0.145. ICC values obtained for each participant are obtained from the 3 coders are shown in Fig. 10. All the scores except one (participant 15) achieved a high agreement value of above 0.7. Participant 15 was a hyperactive child who was fascinated with robots, but more focused on exploring their abilities than observing the activity in a controlled setting. Multiple times, he attempted to get a hold of the robot control devices, removed the robot from the table to observe its parts and asked many questions along the lines of “What else can it do?” The low agreement level of the ratings may be attributed to the haphazard nature of his interaction with the robots, where raters may have had different opinions regarding his interest in the robot itself qualifying as engagement in the activity.

Fig. 10.

ICC values obtained per participant from the 3 coders.

7. RESULTS

The following sections detail the findings from the analysis methods described above. We first present the results with respect to the consolidated engagement index, and then continue with a breakdown in terms of each target behavior, robots, and station, respectively. The Discussion section then elaborates on the trends identified in this Results section and presents explanations and implications for the findings.

7.1. Consolidated engagement index

An overall engagement index value was computed based on the behavioral metrics for every participant’s complete interaction session including both robots, as described in Section 5.2. Average engagement index values for each individual participant in both groups are shown in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Average engagement index values for all participants obtained over the lengths of complete sessions.

To determine the statistical significance of the differences in the average engagement index values for the two groups, we then conducted a T-test (∝ = 0.05) assuming equal means but unknown variances. No statistically significant different in the overall engagement of the two groups was found with p = 0.5048.

7.2. Target behaviors

Each participant’s overall engagement index was broken down in terms of the target behaviors comprising this consolidated value. These results were compiled for the two groups and are shown in Fig. 12. The ASD group was found to perform slightly better on all accounts other than gaze. However, a T-test (∝ = 0.05) was performed once again and found that these differences were not statistically significant. The performance of the ASD group, therefore, is comparable to that of the TD group in terms of each social behavior considered in this study. Details of the T-test are shown in Table 6.

Fig. 12.

A breakdown of overall engagement index in terms of the target behaviors.

Table 6.

Results of the T-test to determine differences in engagement from each target behavior for the 2 groups.

| Target behavior | p-value |

|---|---|

| Gaze | 0.3024 |

| Vocalization | 0.536 |

| Smile | 0.3804 |

| Triadic Interaction | 0.9049 |

| Self-initiated interaction | 0.9669 |

| Imitation | 0.7144 |

7.3. Romo versus Mini

To study the individual performances of the two robots as tools to encourage social engagement in children, an engagement index was derived for each group with respect to the participants’ interactions with each robot. As expected, Romo was found to have an overall lower engagement potential as compared to Mini, with engagement index values significantly lower than those of Mini for both groups (Fig. 13). However, Mini appeared to be more effective with the TD group than ASD, whereas Romo appeared to perform slightly better for the ASD group than TD. A T-test (∝ = 0.05) was conducted and a statistically significant difference was found with Mini outperforming Romo for the TD group (h = 1, p = 0.0000010802). However, no statistically significant difference was identified in the performance of the two robots for the ASD group. Details of the T-test are shown in Table 7.

Fig. 13.

Overall engagement index per group obtained from interactions with each robot.

Table 7.

Results of the T-test to determine differences in engagement from the two robots for each participant group.

| Group | p-value |

|---|---|

| TD | 0.0000010802 |

| ASD | 0.1437 |

This was further analyzed in terms of the target behaviors that comprise the overall engagement metric as a means to assess any difference in the capabilities of each robot to elicit the 6 key social behaviors in children. Gaze was clearly the easiest to evoke, followed by smile. This applied to both robots and both participant groups. Self-initiated interactions and vocalizations had similar elicitation levels followed by triadic interactions and imitation. These findings are shown in Fig. 14.

Fig. 14.

Overall engagement index per group obtained from interactions with each robot.

7.4. Sensory Stations

This part of the data analysis was performed in order to evaluate the potential of every station in the sensory station activity to elicit social engagement. To this end, engagement index values were obtained separately for each station within individual interactions with the two robots, as described in section 6.2. This allowed for an assessment of the sensory station design through a comparison of the engagement contributions of each sensory station. It also facilitated a comparison of robot abilities at each given station, as a means to identify the features of a robot action that may be more effective in engaging children than others, and possibly incorporating changes based on these findings in a future framework design. The results are shown in Fig. 15. Touching, Hearing and Tasting stations were the most engaging for both robots and both participant groups. The Seeing station was at the least engaging end of the spectrum, while Smelling and Celebration stations remained in the middle.

Fig. 15.

Engagement contributions at each sensory station for the two robots and two participant groups.

In addition, the scatter plots in Fig. 16 were generated to take a deeper look at the capacity of each station to elicit certain target behaviors. For Romo, gaze and smile behaviors were generally observed at all stations. More interestingly, almost no instances of imitation were observed for either participant group while interacting with Romo. In addition, the Touching station generated the highest number of self-initiated interactions for both groups (Fig. 16a).

Fig. 16.

A breakdown of engagement from each target behavior at each station for both participant groups during interactions with a) Romo and b) Mini.

As with Romo, gaze and smile behaviors were consistently higher than others at almost all stations during the interactions with Mini. Imitation was observed more frequently with Mini than with Romo for both participant groups, particularly at the Hearing and Celebration stations. For both groups, self-initiated interactions were most common at the Touching station. In general, a larger number of vocalizations were observed at all stations with the ASD group than with the TD group, and triadic interactions were most commonly displayed at the Touching station for both groups.

8. DISCUSSION

In this work, we designed and implemented a framework for children with comorbid ASD and sensory processing disorders. Though the aim of the overall study is to use it as a pedagogical framework to model and teach socially acceptable responses to a variety of sensory stimuli, the current study focuses only on the evaluation of this framework as a tool for social engagement for children with ASD. This is an essential step toward the evaluation of any robot-based behavioral intervention tool for ASD, since it must be able to sustain the interest of a child and maintain his/her engagement in the interaction for the intervention to have success. To this end, we derived a measure of social engagement based on the behavioral data collected from the experiments. We also derived several evaluation metrics to assess the engagement elicitation potential of the framework with respect to the behaviors comprising the engagement metric, the robotic platforms and the station design. This section presents an interpretation of the results from section 7 and its implications on the framework design in the future.

In the sensory station activity, the average consolidated engagement index for participants ranged between 0.15 to 0.35 for the TD group and between 0.17 to 0.37 in the ASD group (Fig. 11). The social engagement of the children in the ASD group was found to be similar to that of the TD group. This implies that the ASD and TD groups showed similar levels of overall social engagement during their interactions with the robots. This finding was reinforced with the results from the target behavior analysis for the two participant groups, which confirmed that there was no difference in the social engagement of the two groups with respect to all 6 of the key social behaviors comprising gaze, vocalization, imitation, smiling, and triadic and self-initiated interactions. This is a promising result that shows that this framework enables children with ASD to match the performance of their TD peers with respect to these key behavioral features of social interactions.

The target behavior analysis also showed that a large portion of the engagement was contributed by the gaze focus metric. All other behavior metrics, though comparable for both groups, offered far lower. Though gaze focus was found to be the easiest social behavior to elicit from the participants, a clear deficit is seen in terms of the contributions from other behavioral metrics. This points to a need for the framework to improve its ability to elicit the other behaviors, which, may arguably have superior distinguishability for social engagement levels.

As expected, Romo, with its relatively primitive emotional expression capacity involving facial expressions, sound effects and movements was unable to match the more advanced vocal communication capabilities of Mini, which allowed it to more effectively elicit social engagement in the participants, as depicted by the results in section 7.3. The superior performance of Mini with TD participants may be attributed to their enhanced abilities to interpret vocal and gestural communication compared to their ASD counterparts. The communication methods of Romo may also have been relatively trivial and hence, less appealing for the TD participants. Both robots were found to elicit similar levels of engagement from the ASD group. It would be interesting to investigate if this outcome changes in the future as data is collected from additional ASD participants.

Findings from the breakdown of engagement index in terms of target behaviors for each robot were consistent with the overall engagement index trends identified in section 7.2. For each robot, gaze focus remained the easiest behavior to elicit in both groups followed by smile, confirming with the findings from the combined data collected from both robots. Here, it is evident that any enhancements in the contributions from behaviors other than gaze focus and smile will necessitate improvements in the actions of both robots.

The Touching, Hearing and Tasting were found to elicit the highest engagement levels for both robots. For Romo, its reaction at the Touch station comprised of a “cute” sleepy expression as it “napped” with the blanket. At the Taste station, it distinctly shows a positive response to one food item but a negative one to another. The high engagement at these stations can be attributed to the easily interpretable scenarios (inspired by everyday experiences of children) and the simple but expressive emotional expressions that can be easily understood. For Mini, in addition to the factor of simple scenario design, there was also the explicit request for help by the Mini at the Touch station (to find lost toys from the sand bowl) that prompted an immediate response from most children, often without waiting for the instructor’s permission to follow the robot’s instruction (Fig. 17a). In addition, the relatability of the disgusted reaction at the Tasting station may also have contributed significantly to the engagement here since the dialog here typically evoked a laugh from most children. For both Romo and Mini, the engagement at the Hearing station may be attributed to the use of music to facilitate an expression of joy, and for Mini in particular, the combination of music with dance moves that were easy to replicate by the children (Fig. 17b).

Fig. 17.

Participants a) following instructions from the robot), b) dancing with the robot, c) guiding the robot and d) waving at the robot.

The lack of imitative behaviors resulting from interactions with Romo was not surprising, given that Romo is a non-humanoid robot with no capacity for human-like gestures. Imitation of its facial expressions was not expected to be common, where engaging emotional expressions typically resulted in smiles instead of actual imitation of the expression. Expectedly, imitation was more common during interactions with the humanoid Mini, both at the Hearing and Celebration stations where the actions performed by the robots were “fun” to replicate.

The Touching station was engaging with both robots given both the soft blanket and the sand available at this station that allowed children to feel the textures with their own hands. Additionally, the presence of a direct request for help from Mini and the simplicity of the instruction, as previously described, meant that children felt comfortable initiating interactions with Mini without needing to be prompted by an instructor. Often times, at this point, the children also turned to look in the direction of their parents in attempt to share their excitement about helping the robot, which explains the large number of self-initiated interactions at this station.

TD children, particularly the older ones were sometimes found to be hesitant to touch the robots or initiate any other interaction with them on their own. We surmise that these participants had assumed that they could not interrupt the activity or that they needed the instructor’s permission to play with the robots, even though no such explicit instruction was given to the participants from either group. This could also have contributed to the relatively low number of vocalizations in the TD group as compared to the ASD group.

An interesting observation from this study was the usefulness of incorporating music in child-robot interactions to encourage increased motor and imitative functions, as supported by the design of the Hearing station. Though not explicitly evaluated in this study, in general, the children were found to show a good understanding of the actions and intentions of the robots as evident by their eagerness to fulfill the request for help from Mini at the Touch station, without requiring any permissions or additional prompts from the instructors. In addition, there were several instances where the children were found to treat the robots as real social entities; the participants were observed to guide the robot to the next station (Fig. 17c) and wave at it as it turned to face them (Fig. 17d) respectively. These observations point to the potential of socially assistive robots as effective intervention tools for ASD due to their ability to engage children in social interactions.

In addition, it must also be pointed out that the heterogeneity with each of the two participant groups limits the generalizability of the findings from this study. The participant age range used in this study was defined as such for convenience sampling and enabled us to derive meaningful insights about the feasibility of our framework. However, the high variability in the participant ages and abilities within each group also curtailed our ability to compare the framework effectiveness for a given cognitive age.

Overall, the results were encouraging and gave us an insight into the effectiveness of the different features of the framework. As a next step, we plan to test the pedagogical capabilities of this framework within the same sensory setup to evaluate its effectiveness as an intervention tool for ASD and sensory processing disorders. This will utilize the data collected through the questionnaires to monitor the participant’s long-term progress over the course of the study. Additional data may also be collected from the participants to explicitly evaluate the interpretability of the robot actions as well as preference for one of the two robotic platforms. In addition, we are also working on the automated assessment of a child’s social engagement during an interaction with the robots by using a multimodal sensing and perception system that utilizes body movement, speech, facial expression, and physiological signal analyses using unobtrusive sensors in order to estimate the internal state of a child. This will allow us to expand the capabilities of the current framework by modulating the robot behaviors in real-time based on the multimodal behavioral and physiological data collected from the child, and in doing so, take one step closer to the simulation of naturalistic social interactions through robots.

9. CONCLUSION

Sensory processing difficulties are commonly experienced by children with ASD and have been found to limit their social experiences, often resulting in social isolation for both the children and their families. While socially assistive robots are being used extensively to target core ASD deficits, very few research efforts have targeted sensory processing disorders. In this study, we designed a novel framework that uses two different robotic platforms to socially engage children with ASD while modeling appropriate responses to common sensory stimuli.

Though children with ASD are typically known to lack social engagement, while interacting with our robots in the current framework, we found them to show either similar social engagement to their TD counterparts. We, therefore, conclude that this framework is indeed a suitable tool to provide social engagement to children with ASD, and that the robot actions and station design contribute to the achievement of this goal. This also validates that the framework can potentially be useful as an intervention tool for sensory processing disorders. Achieving this, however, is the goal of our next study.

With the preliminary user study presented in this paper, we have established the capabilities of this framework as an effective tool for social engagement and hence, a potential tool for designing behavioral interventions for ASD. As our next step, we will be conducting a large-scale, longitudinal user study to evaluate this framework as an intervention tool for sensory processing difficulties that are comorbid with ASD.

CCS Concepts: • Computer systems organization → Robotics;

Contributor Information

HIFZA JAVED, George Washington University.

RACHAEL BURNS, George Washington University.

MYOUNGHOON JEON, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

AYANNA M. HOWARD, Georgia Institute of Technology

CHUNG HYUK PARK, George Washington University.

10. REFERENCES

- [1].Dickie Virginia A., Baranek Grace T., Schultz Beth, Watson Linda R., and McComish Cara S.. "Parent reports of sensory experiences of preschool children with and without autism: a qualitative study." American Journal of Occupational Therapy 63, no. 2 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Grandin Temple. Thinking in pictures: And other reports from my life with autism. Vintage, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tomchek Scott D., and Dunn Winnie. "Sensory processing in children with and without autism: a comparative study using the short sensory profile." American Journal of occupational therapy 61, no. 2 (2007): 190–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Leekam Susan R., Nieto Carmen, Libby Sarah J., Wing Lorna, and Gould Judith. "Describing the sensory abnormalities of children and adults with autism." Journal of autism and developmental disorders 37, no. 5 (2007): 894–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kern Janet K., Trivedi Madhukar H., Garver Carolyn R., Grannemann Bruce D., Andrews Alonzo A., Savla Jayshree S., Johnson Danny G., Mehta Jyutika A., and Schroeder Jennifer L.. "The pattern of sensory processing abnormalities in autism." Autism 10, no. 5 (2006): 480–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kientz Mary Alhage, and Dunn Winnie. "A comparison of the performance of children with and without autism on the Sensory Profile." American Journal of Occupational Therapy 51, no. 7 (1997): 530–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Marco Elysa J., Hinkley Leighton BN, Hill Susanna S, and Nagarajan Srikantan S.. "Sensory processing in autism: a review of neurophysiologic findings." Pediatr Res 69, no. 5 Pt 2 (2011): 48R–54R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Schaaf Roseann C., Toth-Cohen Susan, Johnson Stephanie L., Outten Gina, and Benevides Teal W.. "The everyday routines of families of children with autism: Examining the impact of sensory processing difficulties on the family." Autism 15, no. 3 (2011): 373–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Reynolds Stacey, Bendixen Roxanna M., Lawrence Tami, and Lane Shelly J.. "A pilot study examining activity participation, sensory responsiveness, and competence in children with high functioning autism spectrum disorder." Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 41, no. 11 (2011): 1496–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hilton Claudia, Graver Kathleen, and LaVesser Patricia. "Relationship between social competence and sensory processing in children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders." Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 1, no. 2 (2007): 164–173. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Watson Linda R., Patten Elena, Baranek Grace T., Poe Michele, Boyd Brian A., Freuler Ashley, and Lorenzi Jill. "Differential associations between sensory response patterns and language, social, and communication measures in children with autism or other developmental disabilities." Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 54, no. 6 (2011): 1562–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Park Chung Hyuk, Pai Neetha, Bakthachalam Jayahasan, Li Yaojie, Jeon Myounghoon, and Howard Ayanna M.. "Robotic Framework for Music-Based Emotional and Social Engagement with Children with Autism." In AAAI Workshop: Artificial Intelligence Applied to Assistive Technologies and Smart Environments. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Park Chung Hyuk, Jeon Myounghoon, and Howard Ayanna M.. "Robotic framework with multi-modal perception for physio-musical interactive therapy for children with autism." In Development and Learning and Epigenetic Robotics (ICDL-EpiRob), 2015 Joint IEEE International Conference on, pp. 150–151. IEEE, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Howard Ayanna, Chen Yu-Ping, Park Chung Hyuk, and Desai JP. "From autism spectrum disorder to cerebral palsy: State-of-the-art in pediatric therapy robots." Encyclopedia of medical robotics. World Scientific Publishing Company; (2017). [Google Scholar]

- [15].Goin-Kochel Robin P., Mackintosh Virginia H., and Myers Barbara J.. "Parental reports on the efficacy of treatments and therapies for their children with autism spectrum disorders." Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 3, no. 2 (2009): 528–537. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Green Vanessa A., Pituch Keenan A., Itchon Jonathan, Choi Aram, O’Reilly Mark, and Sigafoos Jeff. "Internet survey of treatments used by parents of children with autism." Research in developmental disabilities 27, no. 1 (2006): 70–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ayres A. Jean. Sensory integration and learning disorders. Western Psychological Services, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ayres A. Jean. Sensory integration and praxis tests (SIPT). Western Psychological Services (WPS), 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Schaaf Roseann C., Benevides Teal, Mailloux Zoe, Faller Patricia, Hunt Joanne, Elke van Hooydonk Regina Freeman, Leiby Benjamin, Sendecki Jocelyn, and Kelly Donna. "An intervention for sensory difficulties in children with autism: A randomized trial." Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 44, no. 7 (2014): 1493–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Moore Monique, and Calvert Sandra. "Brief report: Vocabulary acquisition for children with autism: Teacher or computer instruction." Journal of autism and developmental disorders 30, no. 4 (2000): 359–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Stromer Robert, Kimball Jonathan W., Kinney Elisabeth M., and Taylor Bridget A.. "Activity schedules, computer technology, and teaching children with autism spectrum disorders." Focus on autism and other developmental disabilities 21, no. 1 (2006): 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- [22].DiGennaro Reed Florence D., Hyman Sarah R., and Hirst Jason M.. "Applications of technology to teach social skills to children with autism." Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 5, no. 3 (2011): 1003–1010. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Stahmer Aubyn C., Schreibman Laura, and Cunningham Allison B.. "Toward a technology of treatment individualization for young children with autism spectrum disorders." Brain research 1380 (2011): 229–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nikopoulos Christos K., and Keenan Michael. "Effects of video modeling on social initiations by children with autism." Journal of applied behavior analysis 37, no. 1 (2004): 93–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cabibihan John-John, Javed Hifza, Ang Marcelo, and Aljunied Sharifah Mariam. "Why robots? A survey on the roles and benefits of social robots in the therapy of children with autism." International journal of social robotics 5, no. 4 (2013): 593–618. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Goldsmith Tina R., and LeBlanc Linda A.. "Use of technology in interventions for children with autism." Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention 1, no. 2 (2004): 166. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jeon Myounghoon, Zhang Ruimin, Lehman William, Fakhrhosseini Seyedeh, Barnes Jaclyn, and Park Chung Hyuk. "Development and Evaluation of Emotional Robots for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders." In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, pp. 372–376. Springer, Cham, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wainer Joshua, Robins Ben, Amirabdollahian Farshid, and Dautenhahn Kerstin. "Using the humanoid robot KASPAR to autonomously play triadic games and facilitate collaborative play among children with autism." IEEE Transactions on Autonomous Mental Development 6, no. 3 (2014): 183–199. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Colton Mark B., Ricks Daniel J., Goodrich Michael A., Dariush Behzad, Fujimura Kikuo, and Fujiki Martin. "Toward therapist-in-the-loop assistive robotics for children with autism and specific language impairment." In AISB new frontiers in human-robot interaction symposium, vol. 24, p. 25. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Huijnen Claire AGJ, Lexis Monique AS, and de Witte Luc P.. "Matching robot KASPAR to autism spectrum disorder (ASD) therapy and educational goals." International Journal of Social Robotics 8, no. 4 (2016): 445–455. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gumtau Simone, Newland Paul, and Creed Chris. "MEDIATE–a responsive environment designed for children with autism." In Accessible Design in a Digital World. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Timmermans Hans, Gerard van Wolferen Paul Newland, and Kunath Simon. "MEDIATE: Key Sonic Developments in an Interactive Installation for Children with Autism." In ICMC. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pares Narcis, Masri Paul, Van Wolferen Gerard, and Creed Chris. "Achieving dialogue with children with severe autism in an adaptive multisensory interaction: the" MEDIATE" project." IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 11, no. 6 (2005): 734–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kaliouby El, Rana Rosalind Picard, and Baron-Cohen Simon. "Affective computing and autism." Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1093, no. 1 (2006): 228–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Vaucelle Cati, Bonanni Leonardo, and Ishii Hiroshi. "Design of haptic interfaces for therapy." In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 467–470. ACM, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Changeon Gwénaël, Graeff Delphine, Anastassova Margarita, and Lozada José. "Tactile emotions: A vibrotactile tactile gamepad for transmitting emotional messages to children with autism." In International conference on human haptic sensing and touch enabled computer applications, pp. 79–90. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Amirabdollahian Farshid, Robins Ben, Dautenhahn Kerstin, and Ji Ze. "Investigating tactile event recognition in child-robot interaction for use in autism therapy." In Engineering in medicine and biology society, EMBC, 2011 annual international conference of the IEEE, pp. 5347–5351. IEEE, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Schmitz Alexander, Maggiali Marco, Natale Lorenzo, and Metta Giorgio. "Touch sensors for humanoid hands." In RO-MAN, 2010 IEEE, pp. 691–697. IEEE, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Costa Sandra, Lehmann Hagen, Dautenhahn Kerstin, Robins Ben, and Soares Filomena. "Using a humanoid robot to elicit body awareness and appropriate physical interaction in children with autism." International journal of social robotics 7, no. 2 (2015): 265–278. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bevill Rachael, Azzi Paul, Spadafora Matthew, Chung Hyuk Park Hyung Jung Kim, Lee JongWon, Raihan Kazi, Jeon Myounghoon, and Howard Ayanna M.. "Multisensory robotic therapy to promote natural emotional interaction for children with ASD." In The Eleventh ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human Robot Interaction, pp. 571–571. IEEE Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Javed Hifza and Park Chung Hyuk. "Can Interactions with an Empathetic Agent Regulate Emotions and Improve Engagement in Autism?” IEEE Robotics and Automation Magazine. Special Issue on Socially Assistive Robotics (Accepted) (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Russell James A. "A circumplex model of affect." Journal of personality and social psychology 39, no. 6 (1980): 1161. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ekman Paul. "An argument for basic emotions." Cognition & emotion 6, no. 3-4 (1992): 169–200. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bevill Rachael, Chung Hyuk Park Hyung Jung Kim, Lee JongWon, Rennie Ariena, Jeon Myounghoon, and Howard Ayanna M.. "Interactive robotic framework for multi-sensory therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder." In The Eleventh ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human Robot Interaction, pp. 421–422. IEEE Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [45].LEGO, “LEGO® MINDSTORMS® Education EV3 Software,” 2016. Available: https://education.lego.com/en-us/products/lego-mindstorms-education-ev3-core-set-/5003400. [Accessed: 14-Dec-2017].

- [46].YouTube Audio Library, “Llena de Plena - YouTube Audio Library,” YouTube, 2015. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HP4Y7AsoaoA.

- [47].Ashwin Chris, Chapman Emma, Howells Jessica, Rhydderch Danielle, Walker Ian, and Baron-Cohen Simon. "Enhanced olfactory sensitivity in autism spectrum conditions." Molecular autism 5, no. 1 (2014): 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Legge Brenda. Can't eat, won't eat: Dietary difficulties and autistic spectrum disorders. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Twachtman-Reilly Jennifer, Amaral Sheryl C., and Zebrowski Patrecia P.. "Addressing feeding disorders in children on the autism spectrum in school-based settings: Physiological and behavioral issues." Language, speech, and hearing services in schools 39, no. 2 (2008): 261–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Nadel Jacqueline. "LH Willey, Pretending to be normal: living with Asperger's syndrome, London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 1999." Enfance 52, no. 4 (1999): 416–416. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Dunn Winnie. "The sensations of everyday life: Empirical, theoretical, and pragmatic considerations." American Journal of Occupational Therapy 55, no. 6 (2001): 608–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Ornitz Edward M., and Ritvo Edward R.. "The syndrome of autism: a critical review." The American Journal of Psychiatry (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Friard Olivier, and Gamba Marco. "BORIS: a free, versatile open-source event-logging software for video/audio coding and live observations." Methods in Ecology and Evolution 7, no. 11 (2016): 1325–1330. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Dubey Indu, Ropar Danielle, and de C Hamilton Antonia F.. "Measuring the value of social engagement in adults with and without autism." Molecular autism 6, no. 1 (2015): 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]