Abstract

Agriculture is in crisis. Soil health is collapsing. Biodiversity faces the sixth mass extinction. Crop yields are plateauing. Against this crisis narrative swells a clarion call for Regenerative Agriculture. But what is Regenerative Agriculture, and why is it gaining such prominence? Which problems does it solve, and how? Here we address these questions from an agronomic perspective. The term Regenerative Agriculture has actually been in use for some time, but there has been a resurgence of interest over the past 5 years. It is supported from what are often considered opposite poles of the debate on agriculture and food. Regenerative Agriculture has been promoted strongly by civil society and NGOs as well as by many of the major multi-national food companies. Many practices promoted as regenerative, including crop residue retention, cover cropping and reduced tillage are central to the canon of ‘good agricultural practices’, while others are contested and at best niche (e.g. permaculture, holistic grazing). Worryingly, these practices are generally promoted with little regard to context. Practices most often encouraged (such as no tillage, no pesticides or no external nutrient inputs) are unlikely to lead to the benefits claimed in all places. We argue that the resurgence of interest in Regenerative Agriculture represents a re-framing of what have been considered to be two contrasting approaches to agricultural futures, namely agroecology and sustainable intensification, under the same banner. This is more likely to confuse than to clarify the public debate. More importantly, it draws attention away from more fundamental challenges. We conclude by providing guidance for research agronomists who want to engage with Regenerative Agriculture.

Keywords: Sustainable intensification, agroecology, soil health, biodiversity, organic agriculture

Introduction

Claims that the global food system is ‘in crisis’ or ‘broken’ are increasingly common.1,2 Such claims point to a wide variety of ills, from hunger, poverty and obesity; through industrial farming, over dependence on chemical fertilizer and pesticides, poor quality (if not unsafe) food, environmental degradation, biodiversity loss, exploitative labour relations and animal welfare; to corporate dominance and a lack of resilience. It is in this context, where every aspect of farming and food production, distribution and consumption is being questioned, that the current interest in ‘Regenerative Agriculture’ and ‘Regenerative Farming’3 has taken root.

While the use of the adjective regenerative is expanding among activists, civil society groups and corporations as they call for renewal, transformation and revitalization of the global food system (Duncan et al., 2021), in this paper we explore the calls for Regenerative Agriculture from an agronomic perspective. By this we mean a perspective steeped in the use of plant, soil, ecological and system sciences to support the production of food, feed and fibre in a sustainable manner. Specifically, we address two questions: 1) What is the agronomic problem analysis that motivates the Regenerative Agriculture movement and what is the evidence base for this analysis? 2) What agronomic solutions are proposed, and how well are these supported by evidence?

Our avowedly agronomic perspective on Regenerative Agriculture means that some important aspects of the ‘food system in crisis’ narrative are beyond the scope of this paper, such as food inequalities and labour relations. However, in addition to agronomic science, our analysis is rooted in historical and political economy perspectives. These suggest that the food system is best viewed as an integral part of the much broader network of economic, social and political relations. It follows that many of the faults ascribed to the food system – including hunger, food poverty, poor labour relations, corporate dominance – will not be successfully addressed by action within the food system, but only through higher level political and economic change.

The paper proceeds as follows. The next section explores the origins of Regenerative Agriculture, and the various ways it has been defined. Following this, the two crises that are central to the rationale for Regenerative Agriculture – soils and biodiversity – are interrogated. The subsequent section looks at the practices most commonly associated with Regenerative Agriculture and assesses their potential to solve the aforementioned crises. The final discussion section presents a series of questions that may be useful for research agronomists as they engage with the Regenerative Agriculture agenda.

The origins of regenerative agriculture

The adjective ‘regenerative’ has been associated with the nouns ‘agriculture’ and ‘farming’ since the late 1970s (Gabel, 1979), but the terms Regenerative Agriculture and Regenerative Farming came into wider circulation in the early 1980s when they were picked up by the US-based Rodale Institute. Through its research and publications (including the magazine Organic Gardening and Farming), the Rodale Institute has, over decades, been at the forefront of the organic farming movement.

Robert Rodale (1983) defined Regenerative Agriculture as ‘one that, at increasing levels of productivity, increases our land and soil biological production base. It has a high level of built-in economic and biological stability. It has minimal to no impact on the environment beyond the farm or field boundaries. It produces foodstuffs free from biocides. It provides for the productive contribution of increasingly large numbers of people during a transition to minimal reliance on non-renewable resources’.

Richard Harwood, an agronomist who made his name in the international farming systems research movement (Escobar et al., 2000), was Director of Rodale Research Centre when he published an ‘international overview’ of Regenerative Agriculture (Harwood, 1983). The review goes to great pains to contextualize Regenerative Agriculture in relation to the historical evolution of different schools of organic and biodynamic farming, but it also highlights Rodale’s suggestion that Regenerative Agriculture was beyond organic because it included changes in ‘macro structure’ and ‘social relevancy’, and seeks to increase rather than decrease productive resources (Rodale, 1983). Harwood summarizes the ‘Regenerative Agriculture Philosophy’ in 10 points (Box 1). He further states that this philosophy emphasizes: ‘1) the inter-relatedness of all parts of a farming system, including the farmer and his family; 2) the importance of the innumerable biological balances in the system; and 3) the need to maximise desired biological relationships in the system, and minimise use of materials and practices which disrupt those relationships’.

Box 1. Points summarizing the Regenerative Agriculture Philosophy as presented by Harwood (1983: 31).

Agriculture should produce highly nutritional food, free from biocides, at high yields.

Agriculture should increase rather than decrease soil productivity, by increasing the depth, fertility and physical characteristics of the upper soil layers.

Nutrient-flow systems which fully integrate soil flora and fauna into the pattern of are more efficient and less destructive of the environment, and ensure better crop nutrition. Such systems accomplish a new upward flow of nutrients in the soil profile, reducing or eliminating adverse environmental impact. Such a process is, by definition, a soil genesis process.

Crop production should be based on biological interactions for stability, eliminating the need for synthetic biocides.

Substances which disrupt biological structuring of the farming system (such as present-day synthetic fertilizers) should not be used.

Regenerative agriculture requires, in its biological structuring, an intimate relationship between manager/participants of the system and the system itself.

Integrated systems which are largely self-reliant in nitrogen through biological nitrogen fixation should be utilized.

Animals in agriculture should be fed and housed in such a manner as to preclude the use of hormones and the prophylactic use of antibiotics which are then present in human food.

Agricultural production should generate increased levels of employment.

A Regenerative Agriculture requires national-level planning but a high degree of local and regional self-reliance to close nutrient-flow loops.

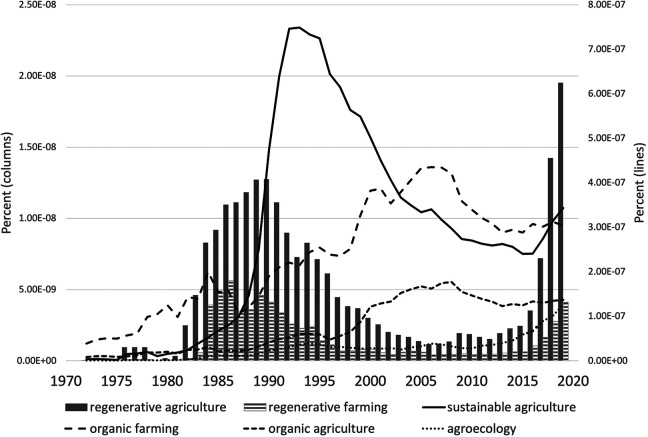

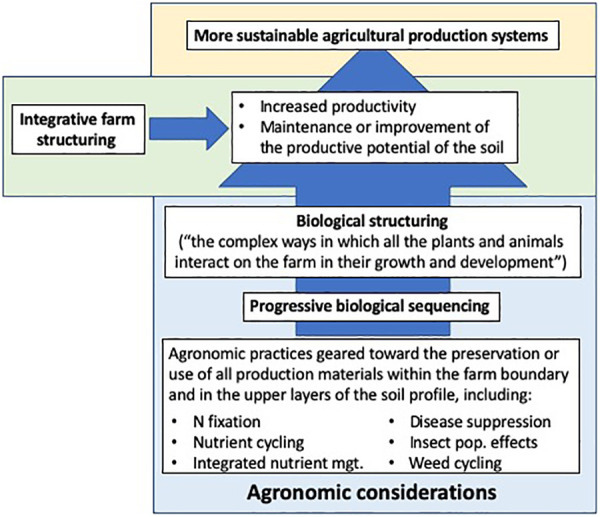

In what is probably the first journal article on Regenerative Agriculture, Francis et al. (1986) link it closely to organic and ‘low external input agriculture’, and highlight the importance of biological structuring, progressive biological sequencing and integrative farm structuring. They also associate it with a number of ‘specific technologies and systems’ including nitrogen fixation, nutrient cycling, integrated nutrient management, crop rotation, integrated pest management (IPM) and ‘weed cycling’. Figure 1 depicts the Regenerative Agriculture theory of change as articulated by Francis et al. (1986).

Figure 1.

Early theory of Regenerative Agriculture in developing countries. Source: Authors’ interpretation of Francis et al. (1986).

A shifting timeline of attention

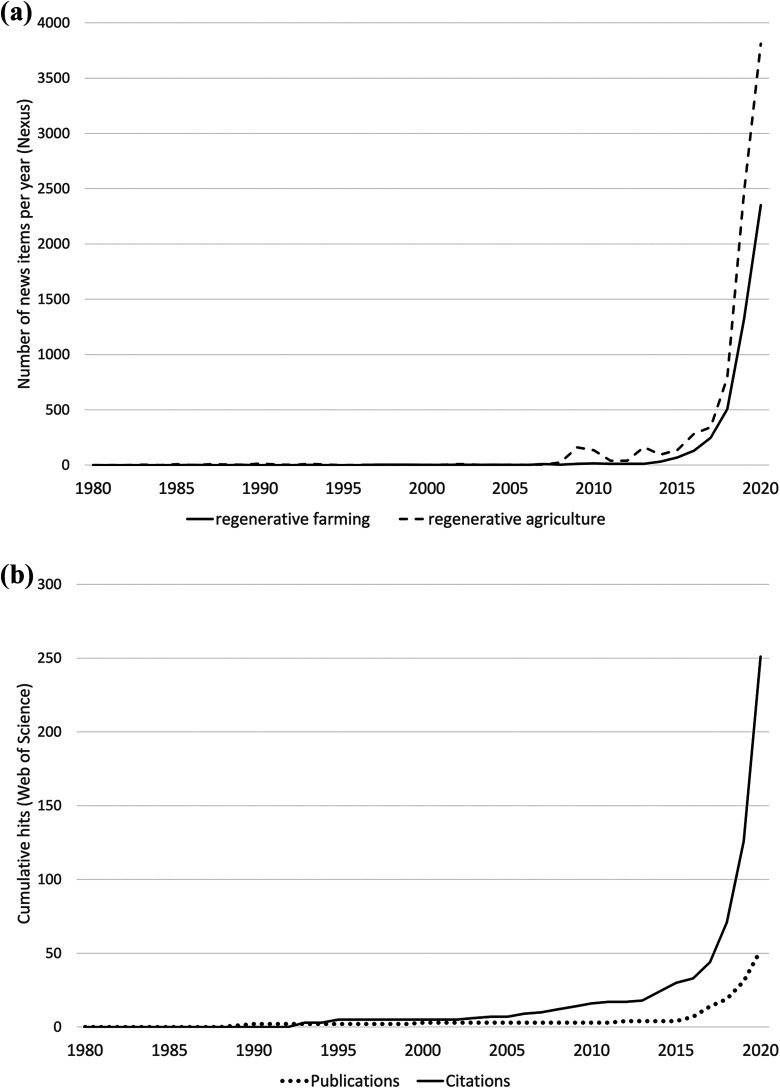

After an initial flurry of interest, Regenerative Agriculture left the scene for almost two decades before regaining momentum. To illustrate this, we look at the extent to which the terms Regenerative Agriculture and Regenerative Farming have been integrated into both the public and academic spheres. For the public sphere we draw from Google Books (Ngram Viewer) and the Nexis Uni database, which searches more than 17,000 news sources. As seen in Figure 2, the occurrence of these terms in books first peaked in the mid-late 1980s, but by the mid-2000s they had virtually disappeared. The occurrence of Regenerative Agriculture then increased dramatically after 2015. It is important to note that over the period 1972–2018, Regenerative Agriculture appears in books much less frequently than other terms such as sustainable agriculture, organic agriculture, organic farming and agroecology.

Figure 2.

The frequency of key terms in books (3-year rolling averages). Source: Google NGram Viewer, Corpus ‘English 2019’ which includes books predominantly in the English language published in any country.

Regenerative Agriculture and Regenerative Farming first appear in the Nexus Uni database of news stories in 1983 and 1986 respectively, both with reference to the Rodale Institute (Figure 3a), and neither term occurred in more than 15 news items each year until 2009. Their use increased dramatically after 2016, and since then the combined occurrence of these terms has doubled each year, reaching 6163 news items in 2020. To place this in perspective, in 2020 organic agriculture and organic farming appeared in 6,870 and 18,301 news items respectively.

Figure 3.

(a) Occurrence of Regenerative Agriculture or Regenerative Farming in news items and (b) Academic peer-reviewed publications on Regenerative Agriculture or Regenerative Farming. Sources: (a) Nexis Uni database, (b) Web of Science.

Turning to the more academic literature, in the first 30 years following the publication of Francis et al. (1986), only seven other papers are identified by Web of Science having the terms Regenerative Agriculture or Regenerative Farming in their title or abstract (Figure 3b). The year 2016 marked a clear turning point in academic interest, and by 2020 a total of 52 academic papers had been published, and together these have been cited some 250 times.

Thus, while the terms Regenerative Agriculture and Regenerative Farming have been in use since the early 1980s, to date they have not been as widely used as other related terms such as sustainable agriculture or organic agriculture. Since 2016 their occurrence in books, news stories and on the internet has increased dramatically, which reflects the fact that they have now been adopted by a wide range of NGOs (e.g. The Nature Conservancy,4 the World Wildlife Fund,5 GreenPeace,6 Friends of the Earth7), multi-national companies (e.g. Danone,8 General Mills,9 Kellogg’s,10 Patagonia,11 the World Council for Sustainable Business Development12) and charitable foundations (e.g. IKEA Foundation13). In relation to this newfound popularity, Diana Martin, the Director of Communications of the Rodale Institute, cautioned ‘It’s [Regenerative Agriculture] the new buzzword. There is a danger of it getting greenwashed’.14

While the academic literature referring to Regenerative Agriculture is growing, the published corpus remains very limited, and only a fraction of this corpus addresses what might be considered agronomic questions. It is likely that additional funding for agronomic research will accompany the public commitments to Regenerative Agriculture being made by NGOs, corporations and foundations. Navigating the rhetoric and potential for greenwash will be a major challenge for research agronomists who seek to work in this area.

Evolving definitions

Within the recent resurgence of interest in Regenerative Agriculture, there is a lack of consensus around any particular definition (Merfield, 2019; Soloviev and Landua, 2016). Early (and continuing) efforts have struggled to draw a clear distinction between regenerative, organic and other ‘alternative’ agricultures (for example, Whyte, 1987: 244): indeed the Rodale Institute continues to refer to ‘regenerative organic agriculture’ (Rodale Institute, 2014).

Since the 1980s, both more broad and more narrow definitions of Regenerative Agriculture have been proposed, with most highlighting or developing one or more of the elements originally identified by Rodale (1983). For example, some authors have emphasized the idea that regenerative systems are ‘semi-closed’, i.e. ‘those designed to minimize external inputs or external impacts of agronomy outside the farm’ (Pearson, 2007) or ‘those in which inputs of energy, in the form of fertilisers and fuels, are minimised because these key agricultural elements are recycled as far as possible’ (Rhodes, 2012). Regenerative Agriculture as ‘a system of principles and practices’ is central to some definitions, but not all. For Burgess et al. (2019) Regenerative Agriculture ‘generates agricultural products, sequesters carbon, and enhances biodiversity at the farm scale’, and for Terra Genesis International it ‘increases biodiversity, enriches soils, improves watersheds, and enhances ecosystem services’.15

This raises the question whether Regenerative Agriculture is an end, or a means to an end. As noted by Burgess et al. (2019) a number of definitions of Regenerative Agriculture focus on the notion of ‘enhancement’, e.g. of soil organic matter (SOM) and soil biodiversity (California State University, 201716); of biodiversity, soils, watersheds, and ecosystem services (Terra Genesis, 201717); of biodiversity and the quantity of biomass (Rhodes, 2017); and of soil health (Sherwood and Uphoff, 2000). Carbon Underground argues that Regenerative Agriculture should be defined around the outcome, claiming that ‘Consensus is mounting for a single, standardized definition for food grown in a regenerative manner that restores and maintains natural systems, like water and carbon cycles, to enable land to continue to produce food in a manner that is healthier for people and the long-term health of the planet and its climate’.18 Finally, the Rodale Institute comes back to the idea of a ‘holistic systems approach’, but now with an explicit nod to both innovation and wellbeing, suggesting that ‘regenerative organic agriculture […] encourages continual on-farm innovation for environmental, social, economic and spiritual wellbeing’ (Rodale Institute, 2014). A specific certification scheme, Regenerative Organic Certified was established in 2017 in the USA under the auspices of the Regenerative Organic Alliance within which the Rodale Institute is a key player.19 Certification is based on three pillars of Soil Health, Animal Welfare and Social Fairness – each of which, it is suggested, can be verified using existing certification standards. A perceived need to move beyond the standards of the USDA Organic Certification scheme has driven the establishment of this new standard.20

In a review of peer-reviewed articles, the most commonly occurring themes associated with Regenerative Agriculture are improvements to soil health, the broader environment, human health and economic prosperity (Schreefel et al., 2020). The authors go on to define Regenerative Agriculture as ‘an approach to farming that uses soil conservation as the entry point to regenerate and contribute to multiple provisioning, regulating and supporting ecosystem services, with the objective that this will enhance not only the environmental, but also the social and economic dimensions of sustainable food production’.

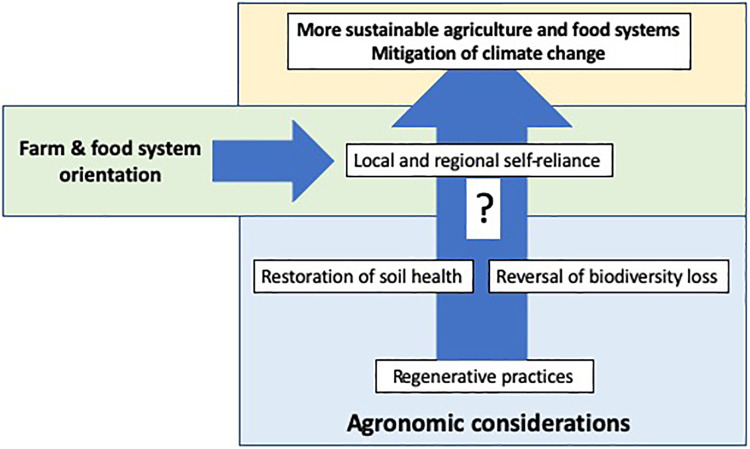

While for some organizations Regenerative Agriculture is unequivocally a form of organic agriculture, others are open to the judicious use of agrochemicals. Nevertheless, from an agronomic perspective the two challenges most frequently linked to Regenerative Agriculture are:

Restoration of soil health, including, the capture of carbon (C) to mitigate climate change

Reversal of biodiversity loss

Figure 4 shows what we understand to be the most common current articulation of the Regenerative Agriculture theory of change. For the purposes of this agronomically oriented paper, the critical question is: How far and in what contexts do the proposed regenerative practices restore soil health and/or reverse biodiversity loss? Given the diversity of understandings of Regenerative Agriculture, and the different contexts within which it is promoted, it should not be surprising that a wide variety of agronomic practices are promoted under the Regenerative Agriculture rubric. We return to these practices later, but first take a closer look at the two crises that Regenerative Agriculture aims to address.

Figure 4.

Regenerative Agriculture: Authors’ interpretation of the commonly used theory of change in 2021. Our analysis focuses on the lower blue box: ‘agronomic considerations’.

The crises addressed by Regenerative Agriculture

In this section we briefly review the purported crises of (1) soil health (including C sequestration) and (2) biodiversity, which are central to most articulations of Regenerative Agriculture. In each case we discuss how the crisis is framed and the strength of the evidence to support this framing.

A crisis of soil health

Soil health receives particularly strong attention in narratives surrounding Regenerative Agriculture (Schreefel et al., 2020; Sherwood and Uphoff, 2000). Indeed, the idea that soil, and soil life in particular, is under threat underpins most, if not all, calls for Regenerative Agriculture. Nonetheless, the term soil health is inherently problematic (Powlson, 2020). Just like soil quality, soil health is a container concept, which requires disaggregation to be meaningful. While it can be understood as something positive to strive for, underlying soil functions need meaningful indicators which can be measured and monitored over long periods of time. Moreover, agronomic practices which benefit one aspect of soil health (such as soil life) often have negative effects on other functions (such as nitrate leaching, primary production or GHG emissions, ten Berge et al., 2019); there is usually not one direction in soil health, but multiple trade-offs.

Many websites and testimonials concerning Regenerative Agriculture highlight the importance of soil biodiversity, and in particular the macro- and micro-organisms which are responsible for the biological cycling of nutrients. Reports of declining soil biodiversity under intensive agriculture and the simplification of soil food webs (de Vries et al., 2013; Tsiafouli et al., 2014) have led to widespread alarm concerning soil health. For example, a recent report of an advisory body to the Dutch government was entitled ‘De Bodem Bereikt’21 – literally, ‘The bottom has been reached’ – a double entendre based on the word ‘bodem’ that means both bottom and soil. The report argues that soil quality has declined to a critical point – at least partly due to loss of soil biodiversity. Whilst studies clearly reveal differences in soil food webs between cultivated fields, grasslands and (semi-) natural vegetation, the links with soil function are largely established through correlation – there is little evidence for any direct causal link between soil biodiversity and any loss in function (see Kuyper and Giller, 2011).

The mantra to ‘feed the soil, not the crop’ has long been central to organic agriculture while the importance of building soil organic matter was highlighted by the proponents of organic or biodynamic agriculture, and in more conventional agricultural discourses in the USA (e.g. USDA, 1938, 1957, 1987) and elsewhere. Soil takes centuries to form and significant soil loss through erosion is unsustainable. The Dust Bowl in the 1930s in the USA was a foundational experience for both the scientific and public appreciation of soil. It is commonly claimed that a quarter or more of the earth’s soils are degraded, although the precise numbers are contested (Gibbs and Salmon, 2015). Commonly quoted estimates of soil loss through erosion are made using run-off plots which tend to overestimate the rates of loss as they do not account for deposition and transfer of soil across the landscape. Nonetheless, Evans et al. (2020) suggest that the rates of soil loss exceed those of soil formation by an order of magnitude, suggesting a lifespan less than 200 years for a third of the soils for which data were available.

A related long-term trend that draws attention to soils, is the reduction in the global soil C pool and its contribution to global warming. Recent modelling estimates the historic soil C loss due to human land use to be around 116 Pg C (Sanderman et al., 2017, 2018), comparable to roughly one-fifth of cumulative GHG emissions from industry. Most of these losses are due to changes in land use. Conversion from natural vegetation, especially forests, almost always results in a decrease in SOM content (Poeplau and Don, 2015) due to non-permanent vegetation, export of biomass and consequently, reduced amounts of organic matter inputs. The loss of soil C through land use conversion is however a different matter than the losses or gains which can be made by altering management practices on existing agricultural land. We discuss the impacts of changing management practices below.

A crisis of biodiversity

Those who promote Regenerative Agriculture frame the crisis of biodiversity around the widespread use of monocultures along with strong dependence on external inputs and a lack of ‘biological cycling’ (Francis et al., 1986). No doubt, large areas of genetically uniform crops can be susceptible to rapid spread of pests and diseases and add little value to the quality of rural landscapes.

If we consider biodiversity more broadly, there is little doubt that the earth has entered a sixth mass extinction (Ceballos et al., 2020). The increase in the human population, the clearance of native habitats and the expansion of agriculture over the past century are clearly root causes. How best to arrest this loss of biodiversity is less clear. Optimistic projections suggest that the world’s population will peak at around 9.8 billion in 2060 (Vollset et al., 2020), whereas the United Nations Population Programme projects a population of 11.4 billion by the end of the century. In either case, the increase in population will without doubt require the production of additional nutritious food. Moderating consumption patterns and changing diets can reduce the extent of this demand, as can reducing food loss and waste, but conservative estimates suggest that overall, global food production must increase by at least 25% (Hunter et al., 2017).

In simple terms, there are two ways to meet this future food demand. The first is to increase production from the existing area of agricultural land: here, what is commonly termed a ‘land sparing’ strategy, involves closing yield gaps by increasing land productivity. The second is to increase the area of land under cultivation. But converting land use to agriculture has direct impacts in terms of habitat loss, as well as multiple indirect effects through altering biogeochemical and hydrological cycles (Baudron and Giller, 2014). In many areas an expansion of agricultural lands to increase food production will mean that inherently less productive soils are brought under cultivation, requiring disproportionate land use conversion. Against this backdrop, calls for, and commitments to Zero (Net) Deforestation are changing to calls for Zero (Net) Land Conversion.22 Both aim specifically to protect areas of high conservation value for biodiversity, with the latter focused on the use of degraded lands for any future expansion of agriculture, while restoring ecosystems with high value for biodiversity conservation.

Another major concern for impacts on biodiversity relates to the effects of the chemicals used for plant protection, and in particular insecticides. Despite increasingly stringent controls since Rachel Carson published ‘Silent Spring’ in 1962, concerns remain. Attention has been focused on impacts on non-target organisms, with considerable alarm at the loss of bees and other pollinators (Hall and Martins, 2020). A recent report that attracted considerable attention in the media indicated a 75% decline in flying insect biomass in Germany in only 27 years (Hallmann et al., 2017). A global meta-analysis painted a more complex picture, suggesting (still alarming) average declines of ∼9% per decade in terrestrial insect abundance, but ∼11% per decade increases in freshwater insect abundance, and strong regional differences (van Klink et al., 2020). Echoing the concerns about DDT raised by Carson, declines in populations of insectivorous birds were found to be associated with higher concentrations of neonicotinoids in the environment (Hallmann et al., 2014). Further, neonicotinoids have been implicated in a new pesticide treadmill, where pesticide resistance and reduced populations of natural enemies lead to increased dependence on chemical control (Bakker et al., 2020b). With respect to weed control, the introduction of glyphosate was widely lauded as it was seen as environmentally benign compared with alternative herbicides. However, its widespread use combined with ‘Round-up Ready’ varieties of maize, oilseed rape and soybean, and reduced tillage, has led to the proliferation of herbicide-resistant weeds (Mortensen et al., 2012). With increasing concerns over human toxicity, glyphosate use has become highly controversial, leading to an earlier re-assessment of its license in the EU.23

Regenerative Agriculture practices

The practices

McGuire (2018), Burgess et al. (2019) and Merfield (2019) provide lists of practices associated with different variants of Regenerative Agriculture which we order in Table 1 around agronomic principles. It should be noted, that to qualify as Regenerative Organic Agriculture, no chemical fertilizers or synthetic pesticides can be used and ‘soil-less’ cultivation methods are prohibited.

Table 1.

Agronomic principles and practices considered to be part of Regenerative Agriculture and their potential impacts on restoration of soil health and reversal of biodiversity loss.

| Principles | Practices | Restoration of soil health | Reversal of biodiversity loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimize tillage | Zero-till, reduced tillage, conservation agriculture, controlled traffic | *** | – |

| Maintain soil cover | Mulch, cover crops, permaculture | *** | * |

| Build soil C | Biochar, compost, green manures, animal manures | *** | – |

| Sequester carbon | Agroforestry, silvopasture, tree crops | *** | ** |

| Relying more on biological nutrient cycles | Animal manures, compost, compost tea, green manures and cover crops, maintain living roots in soil, inoculation of soils and composts, reduce reliance on mineral fertilizers, organic agriculture, permaculture | *** | – |

| Foster plant diversity | Diverse crop rotations, multi-species cover crops, agroforestry | ** | *** |

| Integrate livestock | Rotational grazing, holistic [Savory] grazing, pasture cropping, silvopasture | ** | ? |

| Avoid pesticides | Diverse crop rotations, multi-species cover crops, agroforestry | * | *** |

| Encouraging water percolation | Biochar, compost, green manures, animal manures, holistic [Savory] grazing | *** | – |

Based on McGuire (2018), Burgess et al. (2019) and Merfield (2019).

Many practices associated with Regenerative Agriculture, such as crop rotations, cover crops, livestock integration, are (or in some contexts were) generally considered to be ‘Good Agricultural Practice’ and remain integral to conventional farming. Some are more problematic: conservation agriculture, for example, can be practiced within an organic framework or as GMO-based, herbicide and fertilizer intensive (Giller et al., 2015). Others, such as permaculture, have rather limited applicability for the production of many agricultural commodities. Still others, such as holistic grazing are highly contentious in terms of the claims made for their broad applicability and ecological benefits in terms of soil C accumulation and reduction of greenhouse gas emissions (Briske et al., 2014; Garnett et al., 2017). The potential of perennial grains has aroused substantial interest in relation to Regenerative Agriculture. Deep rooting perennial grasses such as intermediate wheatgrass (Thinopyrum intermedium), cereals (e.g. sorghum) or legumes (e.g. pigeonpea) have the advantage of supplying multiple products such as fodder as well as grain, and provide continuous soil cover that can arrest soil erosion and reduce nitrate leaching (Glover et al., 2010). On the down side, perennial grains tend to yield less than annual varieties and share constraints with monocultures in terms of pest and disease build up. They may also encounter difficulties with weed control. Snapp et al. (2019) provide a nuanced analysis of the potential of perennial grains.

Regenerative Agriculture practices, the soil crisis and climate change

A majority of the Regenerative Agriculture practices focus on soil management, with a particular emphasis on increasing soil C, under the premise that it will increase crop yields and mitigate climate change. SOM is an important indicator of soil fertility (Reeves, 1997) as it serves many functions within the soil, for example in the supply of nutrients, soil structure, water holding capacity, and supporting soil life (Johnston et al., 2009; Watts and Dexter, 1997).

The amount of C stored in soil is largely a function of the amount of organic matter added to the soil and soil texture: clay soils can store much more C than sandy soils (Chivenge et al., 2007). Soil tillage has only a minor effect (Giller et al., 2009). The degree to which the amount of C stored in the soil can be increased depends on the starting conditions. A continuously cultivated, degraded clay soil, heavily depleted of soil C, can store much more extra C than a degraded sandy soil. A fertile soil may already be close to what is called its C ‘saturation potential’ (Six et al., 2002). Thus under continuous cultivation, soil C can only be increased marginally by changing management practices, such as the use of animal manure, cultivation of green manures or return of crop residues (Poulton et al., 2018). The greatest opportunities to increase soil C are found in low yielding regions, where increasing crop yields increase the available biomass stock and inputs of organic matter to the soil (van der Esch et al., 2017). But even if SOM increases due to improved management, the rate of annual increase in soil C is temporary. As a new equilibrium is reached the rate of C accumulation attenuates (Baveye et al., 2018) and this new equilibrium is reached at a lower level under cultivation than under natural vegetation cover. Limiting the conversion of forest and natural grasslands to agriculture is therefore essential to protect soil C stocks. Among the practices associated with Regenerative Agriculture, agroforestry in its many shapes and forms perhaps has the greatest potential to contribute to climate change mitigation through C capture both above- and below-ground (Feliciano et al., 2018; Rosenstock et al., 2019).

A synthesis of 14 meta-analyses across the globe indicates that crop yields mainly benefit from increased SOM due to the nutrients, in particular N, which it supplies (Hijbeek et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the global N budget over the last 50 years, suggests that half of the N taken up by cereals came from mineral fertilizers (Ladha et al., 2016), indicating that global food production would collapse without external nutrients. If a field is used for crop production without any external source of nutrients, as espoused by some proponents of Regenerative Agriculture, this will degrade the soil resource base and lead to a decline in yields. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation through legumes can provide a truly renewable source of some N, but to sustain production in the long term, external sources of other nutrients are required to compensate for the nutrient offtake through harvested crops.

As with the external nutrient supply, other technical options can mimic, supplement or substitute for some of the contributions that SOM makes to soil fertility. Irrigation and tillage, for example, can have positive effects on soil water availability and soil structure respectively (van Noordwijk et al., 1997). This is one of the reasons why increasing SOM does not always directly benefit soil fertility or crop yields (Hijbeek, 2017). Additional SOM only increases crop yields in the short term if it alleviates an immediate constraint to crop growth. In the longer term it would be expected that increased SOM leads to crop yields that are more resilient to abiotic stresses due to improved soil physical structure, but evidence on this is scarce.

With current trends in greenhouse gas emissions, most IPCC scenarios include net negative emission technologies to limit global warming to a maximum of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels (Rogelj et al., 2018). These technologies include carbon capture and storage, but also reforestation and soil C sequestration (Rogelj et al., 2018). In this light, Regenerative Agriculture is said to hold a promise of ‘zero carbon farming’ or even offsetting GHG emissions from other sectors (Hawken, 2017). The most recent offering from the Rodale Institute ‘confidently declares that global adoption of regenerative practices across both grasslands and arable acreage could sequester more than 100% of current anthropogenic emissions of CO2’ (Moyer et al., 2020). The confidence in this claim was rapidly dented by other protagonists of Regenerative Agriculture, who concluded the figure was probably closer to 10–15%.24

A recent study in China investigated potential soil C sequestration across a range of different cropping systems. The results show that – for a wide range of crop rotations and management practices – soil C sequestration compensated on average for 10% of the total GHG emissions (N2O, CH4, CO2), with a maximum of 30% (Gao et al., 2018). Although there were many examples of soil C increasing in response to increased crop yields, the climate change benefits (expressed as CO2-equivalent) were considerably outweighed by the greenhouse gas emissions associated with the practices themselves, especially N fertilizer and irrigation. In the UK, Powlson et al. (2011) reported similar outcomes using data from the Broadbalk experiment: associated GHG emissions of crop management (tillage, fertilizers, irrigation, crop protection, etc.) were four-fold greater than the carbon sequestered. Of course, in Regenerative Agriculture the use of some of these GHG emitting crop management practices and external nutrient inputs, such as mineral fertilizers are abandoned. But while organic fertilizers such as manure can increase SOM and have additional yield benefits beyond nutrient supply, they are also more prone to nutrient losses. A recent global meta-analysis showed that manure application significantly increased N2O emissions by an average 32.7% (95% confidence interval: 5.1–58.2%) compared with mineral fertilizers (Zhou et al., 2017), thereby offsetting the mitigation gains of soil C sequestration.

The exclusion of external inputs is even more problematic, considering that nutrients are needed to build SOM and sequester soil C (Kirkby et al., 2011; Richardson et al., 2014). This phenomenon can be explained by stoichiometric arguments and has been coined ‘the nitrogen dilemma’ of soil C sequestration (van Groenigen et al., 2017). As shown by Rice and MacCarthy (1991), the elemental composition of SOM (ratios of C, H, O, N and S) has a narrow range. If C is added to a soil in which there is no surplus N, P or S, there will be no increase in SOM and the carbon will be lost to the atmosphere as CO2. Besides the associated energy requirements to build SOM, this also raises the question whether those nutrients are most useful to human society when stored in the soil, or when available for plant growth (Janzen, 2006).

Regenerative Agriculture practices and the biodiversity crisis

Although reversing loss of biodiversity is a central tenet of Regenerative Agriculture, it receives surprisingly little attention in discussions of recommended practices. The principle ‘foster plant diversity’ is of course central, and is one means to address the principle to ‘avoid pesticides’. Yet little attention is paid to approaches such as integrated pest and disease management (IPM). The principles of IPM – to minimize chemical use and maximize the efficiency when used – are well established. Genetic resistance is key, and regular crop scouting is used to trigger responsive spraying when a particular threshold of the pest and disease is observed, rather than preventative spraying at particular times in the cropping calendar. Recommended practices such as rotations and (multi-species) cover crops fit within IPM, as do approaches such as intercropping and strip cropping which are largely ignored in discussions of Regenerative Agriculture. IPM is knowledge intensive, requires regular crop monitoring and the skill to identify early signs of outbreaks of multiple pests and diseases. The reasons for the lack of uptake of IPM approaches are complex, but include the perceived risk of crop damage (Bakker et al., 2020a). Alongside IPM, integrated weed control (IWM) combines the use of mechanical weeding through tillage and cover cropping with a much more strategic use of herbicides (Mortensen et al., 2012). IWM is promoted as an environmentally friendly approach that can harness diversity to manage deleterious effects of weeds (Adeux et al., 2019), but again, is highly knowledge intensive.

Whether it is possible to continue intensive forms of agriculture which will meet global demands for agricultural produce without the use of chemicals for plant protection is the subject of much debate. There is a danger that bans on the use of some products could lead to wider use of even more toxic ones, at least for a period before environmental controls catch up. Few could disagree with the aspiration to limit the use of chemicals in agriculture: in addition to biodiversity concerns, the misuse of pesticides in developing countries has serious negative effects on human health (Boedeker et al., 2020; Jepson et al., 2014).

Finally, much of the discussion of Regenerative Agriculture, pesticides and biodiversity concerns biodiversity on-farm, rather than biodiversity across landscapes, or enhancing yields to spare land for biodiversity conservation and prevent the need for further land conversion to agriculture. This is a theme we return to when considering the broader implications of Regenerative Agriculture below.

Discussion

Agriculture all over the world faces serious challenges, as governments, corporations, research agronomists, farmers and consumers seek to negotiate a critical but dynamic balance between human welfare (or the ‘right to food’), productivity, profitability, and environmental sustainability. However, given the high degree of diversity of agro-ecosystems, farm systems and policy contexts, the nature of these challenges can vary dramatically over time and space. This fact undermines any proposition that it is possible to identify one meaningful and widely relevant problem definition, or specific agronomic practices which could alleviate pressures on the food system everywhere.

Neither the ‘soil crisis’ nor the ‘biodiversity crisis’, both of which are central to the rationale for Regenerative Agriculture, is universal; and across those contexts where one, the other or both can be observed, their root causes and manifestations are not necessarily the same. This tension between, on the one hand, a compelling, high-level narrative that identifies a problem, its causes and how it should be addressed, and on the other, the complexity of divergent local realities, arises with all universalist schemes to ‘fix’ agriculture and the ‘failing’ food system. In this sense, Regenerative Agriculture, while using new language, is no different than sustainable agriculture, sustainable intensification, climate-smart agriculture, organic farming, agroecology and so on.

To date the discussion around Regenerative Agriculture has taken little account of the wide variety of initial starting points defined by the variation in local contexts and farming systems and the scales at which they operate. For example, the problems caused by over-use of fertilizer or manure in parts of North America, Europe and China may well allow for reductions in input use and result in significant environmental benefits, without necessarily compromising crop yields or farmer incomes. In contrast, in many developing countries, and especially in Africa, crop productivity, and thus the food security and/or incomes of farming households, is tightly constrained by nutrient availability (i.e. because of highly weathered soils, and the limited availability of fertilizer, manure and compostable organic matter) (e.g. Rufino et al., 2011). Under such circumstances continued cultivation inevitably leads to soil degradation, and the use of external inputs, including fertilizer, is essential to increase crop yields, sustain soils and build soil C (Vanlauwe et al., 2014, 2015).

Although not all interpretations of Regenerative Agriculture preclude the use of agrochemicals, all argue to reduce and minimize their use. In writings on Regenerative Agriculture, surprising little attention is paid to alternative methods of pest and disease control, although this appears to be one of the major challenges that farmers will face in order to reduce or phase out chemical control methods. Some interpretations of Regenerative Agriculture are uncompromisingly anti-GMO, despite the potential genetic engineering has to confer plant resistance and reduce the need for chemical sprays (Giller et al., 2017; Lotz et al., 2020). Further, all types of agrochemicals are lumped into the same basket, whereas the concerns for both human and environmental health associated with pesticides and fertilizers are vastly different.

As academic and other research agronomists now seek to engage constructively with the individuals, organizations and corporations championing Regenerative Agriculture, we argue that for any given context there are five questions that must be addressed:

What is the problem to which Regenerative Agriculture is meant to be the solution?

What is to be regenerated?

What agronomic mechanism will enable or facilitate this regeneration?

Can this mechanism be integrated into an agronomic practice that is likely to be economically and socially viable in the specific context?

What political, social and/or economic forces will drive use of the new agronomic practice?

These questions are meant to stimulate critical reflection on the agronomic aspects of the mechanisms and dynamics of regeneration, given that it is the conceptual core of Regenerative Agriculture. Without reflection along these lines, Regenerative Agriculture will continue to struggle to differentiate itself from other forms of ‘alternative’ agriculture, while the practices with which it is associated will (continue to) vary little if at all from those in the established canon of ‘Good Agricultural Practices’. The questions will also help to separate the philosophical baggage and some of the extraordinary claims that are linked to Regenerative Agriculture, from the areas and problems where agronomic research might make a significant contribution.

The growing enthusiasm for Regenerative Agriculture highlights the need for agronomists to be more explicit about the fact that many of the categories and dichotomies that frame public, and to some degree the scientific debates about agriculture, have little if any analytical purchase. These include e.g. alternative/conventional; family/industrial; regenerative/degenerative; and sustainable/unsustainable. Regardless of their currency in public discourse, these categories are far too broad and undefinable to have any place in guiding agronomic research (although the politics behind their use and abuse in discourse remains of considerable interest).

It is clear from many farmer’s testimonials on the Internet that their moves towards Regenerative Agriculture are underpinned by a philosophy that seeks to protect and enhance the environment. The core argument is most often around soil health, and in particular soil biological health, which is seen as being under threat and is attributed somewhat mythical properties. In much of the promotional material available in the public domain, exaggerated claims are made for the potency and functioning of soil microorganisms in particular. By contrast, for many campaigning NGOs, the locking up or sequestration of carbon in the soil is paramount, with a vision of an agriculture free of external inputs or GMOs, that mimics nature and contributes to solving the climate crisis. Not surprisingly the claimed potential of Regenerative Agriculture has attracted considerable critique – as McGuire (2018) aptly captures in his blog entitled ‘Regenerative Agriculture: Solid Principles, Extraordinary Claims’. It seems unlikely that Regenerative Agriculture can deliver all of the positive environmental benefits as well as the increase in global food production that is required. Reflective engagement by research agronomists is now critically important.

Acknowledgement

We thank David Powlson and Matthew Kessler for their critical reviews of an earlier version of this manuscript. All errors or omissions remain our responsibility.

Notes

Hereon we use the term Regenerative Agriculture to encompass Regenerative Farming.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The NWO-WOTRO Strategic Partnership NL-CGIAR and the CGIAR Research Program on Maize through the CIMMYT grant ‘Rural livelihood-oriented research methodologies for social impact analyses of Sustainable Intensification interventions’.

ORCID iD: Ken E Giller  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5998-4652

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5998-4652

James Sumberg  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4626-5237

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4626-5237

References

- Adeux G, Vieren E, Carlesi S, et al. (2019) Mitigating crop yield losses through weed diversity. Nature Sustainability 2:1018–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker L, Sok J, van der Werf W, et al. (2020. a) Kicking the habit: What makes and breaks farmers’ intentions to reduce pesticide use? Ecological Economics 180:106868. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker L, van der Werf W, Tittonell P, et al. (2020. b) Neonicotinoids in global agriculture: Evidence for a new pesticide treadmill? Ecology and Society 25:26. [Google Scholar]

- Baudron F, Giller KE. (2014) Agriculture and nature: Trouble and Strife? Biological Conservation 170:232–245. [Google Scholar]

- Baveye PC, Berthelin J, Tessier D, et al. (2018) The “4 per 1000” initiative: a credibility issue for the soil science community? Geoderma 309:118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Boedeker W, Watts M, Clausing P, et al. (2020) The global distribution of acute unintentional pesticide poisoning: estimations based on a systematic review. BMC Public Health 20:1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Briske DD, Ash AJ, Derner JD, et al. (2014) Commentary: a critical assessment of the policy endorsement for holistic management. Agricultural Systems 125:50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess PJ, Harris J, Graves AR, et al. (2019) Regenerative Agriculture: Identifying the Impact; Enabling the Potential. Report for SYSTEMIQ. Cranfield: Cranfield University. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos G, Ehrlich PR, Raven PH. (2020) Vertebrates on the brink as indicators of biological annihilation and the sixth mass extinction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117:13596–13602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivenge PP, Murwira HK, Giller KE, et al. (2007) Long-term impact of reduced tillage and residue management on soil carbon stabilization: implications for conservation agriculture on contrasting soils. Soil & Tillage Research 94:328–337. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries FT, Thebault E, Liiri M, et al. (2013) Soil food web properties explain ecosystem services across European land use systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110:14296–14301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan J, Carolan M, Wiskerke JS. (2021) Routledge Handbook of Sustainable and Regenerative Food Systems. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar G, Hilderbrand P, Harwood RR, et al. (2000) FSR-origins and perspectives. In: Collinson M. (ed) A History of Farming Systems Research. Rome and Wallingford: FAO & CABI Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Evans DL, Quinton JN, Davies JAC, et al. (2020) Soil lifespans and how they can be extended by land use and management change. Environmental Research Letters 15:0940b0942. [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano D, Ledo A, Hillier J, et al. (2018) Which agroforestry options give the greatest soil and above ground carbon benefits in different world regions? Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 254:117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Francis CA, Harwood RR, Parr JF. (1986) The potential for regenerative agriculture in the developing world. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture 1:65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gabel M. (1979) Ho-Ping: A World Scenario for Food Production, Philadelphia, PA: World Game Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Gao B, Huang T, Ju X, et al. (2018) Chinese cropping systems are a net source of greenhouse gases despite soil carbon sequestration. Global Change Biology 24:5590–5606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett T, Godde C, Muller A, et al. (2017) Grazed and Confused? Ruminating on Cattle, Grazing Systems, Methane, Nitrous Oxide, the Soil Carbon Sequestration Question – and What it all Means for Greenhouse gas Emissions. Oxford: Food Climate Research Network, University of Oxford, p. 127. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs HK, Salmon JM. (2015) Mapping the world’s degraded lands. Applied Geography 57:12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Giller KE, Andersson JA, Corbeels M, et al. (2015) Beyond conservation agriculture. Frontiers in Plant Science 6. Article 870.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giller KE, Andersson JA, Sumberg J, et al. (2017) A golden age for agronomy? In: Sumberg J. (ed) Agronomy for Development. London: Earthscan, pp. 150–160. [Google Scholar]

- Giller KE, Witter E, Corbeels M, et al. (2009) Conservation agriculture and smallholder farming in Africa: the heretics’ view. Field Crops Research 114:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Glover JD, Reganold JP, Bell LW, et al. (2010) Increased food and ecosystem security via perennial grains. Science 328:1638–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DM, Martins DJ. (2020) Human dimensions of insect pollinator conservation. Current Opinion in Insect Science 38:107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallmann CA, Foppen RPB, van Turnhout CAM, et al. (2014) Declines in insectivorous birds are associated with high neonicotinoid concentrations. Nature 511:341–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallmann CA, Sorg M, Jongejans E, et al. (2017) More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. PLoS One 12:e0185809–0185821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood RR. (1983. ) International overview of regenerative agriculture. In: Proceedings of Workshop on Resource-efficient Farming Methods for Tanzania, Morogoro, Tanzania, 16–20 May 1983, Faculty of Agriculture, Forestry, and Veterinary Science, University of Dares Salaam, . Morogoro, TZ: Rodale Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hawken P. (2017) Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming, New York, NY: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Hijbeek R. (2017) On the Role of Soil Organic Matter for Crop Production in European Arable Farming, Wageningen: Wageningen University. [Google Scholar]

- Hijbeek R, Ittersum MK, ten Berge H, et al. (2018) Evidence Review Indicates a Re-Think on the Impact of Organic Inputs and Soil Organic Matter on Crop Yield. Cambridge, MA: International Fertiliser Society. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter MC, Smith RG, Schipanski ME, et al. (2017) Agriculture in 2050: recalibrating targets for sustainable intensification. BioScience 67:386–391. [Google Scholar]

- Janzen HH. (2006) The soil carbon dilemma: Shall we hoard it or use it? Soil Biology and Biochemistry 38:419–424. [Google Scholar]

- Jepson PC, Guzy M, Blaustein K, et al. (2014) Measuring pesticide ecological and health risks in West African agriculture to establish an enabling environment for sustainable intensification. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 369:20130491–20130491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston AE, Poulton PR, Coleman K. (2009) Chapter 1 soil organic matter: its importance in sustainable agriculture and carbon dioxide fluxes. In: Sparks DL. (ed) Advances in Agronomy. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkby CA, Kirkegaard JA, Richardson AE, et al. (2011) Stable soil organic matter: a comparison of C:N:P:S ratios in Australian and other world soils. Geoderma 163:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Kuyper TW, Giller KE. (2011) Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning below-ground. In: Lenne JM, Wood D. (eds) Agrobiodiversity Management for Food Security. Wallingford: CABI, pp. 134–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ladha JK, Tirol-Padre A, Reddy CK, et al. (2016) Global nitrogen budgets in cereals: a 50-year assessment for maize, rice and wheat production systems. Scientific Reports 6:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotz LA, van de Wiel CC, Smulders MJ. (2020) Genetic engineering at the heart of agroecology. Outlook on Agriculture 49:21–28. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire A. (2018) Regenerative Agriculture: Solid Principles, Extraordinary Claims. Available at: http://csanr.wsu.edu/regen-ag-solid-principles-extraordinary-claims/ (accessed 01 February 2021).

- Merfield CN. (2019) An analysis and overview of regenerative agriculture. Report number 2-2019. Lincoln, NZ: The BHU Future Farming Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen DA, Egan JF, Maxwell BD, et al. (2012) Navigating a critical juncture for sustainable weed management. BioScience 62:75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Moyer J, Smith A, Rui Y, et al. (2020) Regenerative Agriculture and the Soil Carbon Solution. Kutztown, PA: Rodale Institute. Available at: https://rodaleinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/Rodale-Soil-Carbon-White-Paper_v11-compressed.pdf.(accessed 1 February 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CJ. (2007) Regenerative, semiclosed systems: a priority for twenty-first-century agriculture. BioScience 57:409–418. [Google Scholar]

- Poeplau C, Don A. (2015) Carbon sequestration in agricultural soils via cultivation of cover crops – a meta-analysis. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 200:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Poulton P, Johnston J, Macdonald A, et al. (2018) Major limitations to achieving “4 per 1000” increases in soil organic carbon stock in temperate regions: evidence from long-term experiments at Rothamsted Research, United Kingdom. Global Change Biology 24:2563–2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powlson DS. (2020) Soil health - useful terminology for communication or meaningless concept? Or both? Frontiers of Agricultural Science and Engineering 7(3):246–250. DOI: 10.15302/J-FASE-2020326.

- Powlson DS, Whitmore AP, Goulding KWT. (2011) Soil carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change: a critical re-examination to identify the true and the false. European Journal of Soil Science 62:42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves D. (1997) The role of soil organic matter in maintaining soil quality in continuous cropping systems. Soil and Tillage Research 43:131–167. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes CJ. (2012) Feeding and healing the world: through regenerative agriculture and permaculture. Science Progress 95:345–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes CJ. (2017) The imperative for regenerative agriculture. Science Progress 100:80–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice JA, MacCarthy P. (1991) Statistical evaluation of the elemental composition of humic substances. Organic Geochemistry 17:635–648. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson AE, Kirkby CA, Banerjee S, et al. (2014) The inorganic nutrient cost of building soil carbon. Carbon Management 5:265–268. [Google Scholar]

- Rodale Institute (2014) Regenerative Organic Agriculture and Climate Change: A Down-to-Earth Solution to Global Warming. Kutztown, PA: Rodale Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Rodale R. (1983) Breaking new ground: the search for a sustainable agriculture. The Futurist 1:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rogelj J, Shindell D, Jiang K, et al. (2018) Mitigation pathways compatible with 1.5 C in the context of sustainable development. In: Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pörtner H-O, et al. (eds) Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/05/SR15_Chapter2_Low_Res.pdf (accessed 19 February 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock TS, Wilkes A, Jallo C, et al. (2019) Making trees count: Measurement and reporting of agroforestry in UNFCCC national communications of non-Annex I countries. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 284:106569. [Google Scholar]

- Rufino MC, Dury J, Tittonell P, et al. (2011) Competing use of organic resources, village-level interactions between farm types and climate variability in a communal area of NE Zimbabwe. Agricultural Systems 104:175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderman J, Hengl T, Fiske GJ. (2017) Soil carbon debt of 12,000 years of human land use. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114:9575–9580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderman J, Hengl T, Fiske GJ. (2018) Correction for Sanderman et al., Soil carbon debt of 12,000 years of human land use. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115:E1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreefel L, Schulte RPO, de Boer IJM, et al. (2020) Regenerative agriculture – the soil is the base. Global Food Security 26:100404. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood S, Uphoff N. (2000) Soil health: research, practice and policy for a more regenerative agriculture. Applied Soil Ecology 15:85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Six J, Conant RT, Paul EA, et al. (2002) Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: implications for C-saturation of soils. Plant and Soil 241:155–176. [Google Scholar]

- Snapp S, Roge P, Okori P, et al. (2019) Perennial grains for Africa: Possibility or pipedream? Experimental Agriculture 55:251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Soloviev ER, Landua G. (2016) Levels of Regenerative Agriculture. Driggs, ID: Terra Genesis International. [Google Scholar]

- ten Berge H, Schröder J, Olesen JE, et al. (2019) Soil quality: a confusing beacon for sustainability. In: International Fertiliser Society Conference Cambridge, 12–13 December 2019. International Fertiliser Society Proceedings. Colchester, UK: International Fertiliser Society. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiafouli MA, Thébault E, Sgardelis SP, et al. (2014) Intensive agriculture reduces soil biodiversity across Europe. Global Change Biology 21:973–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA (1938) Soils and Men: The Yearbook of Agriculture 1938, Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- USDA (1957) Soil: The Yearbook of Agriculture 1957, Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- USDA (1987) Our American Land: The Yearbook of Agriculture 1987, Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- van der Esch S, ten Brink B, Stehfest E, et al. (2017) Exploring Future Changes in Land use and Land Condition and the Impacts on Food, Water, Climate Change and Biodiversity: Scenarios for the UNCCD Global Land Outlook. The Hague: PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. [Google Scholar]

- van Groenigen JW, van Kessel C, Hungate BA, et al. (2017) Sequestering soil organic carbon: a nitrogen dilemma. Environmental Science and Technology 51:4738–4739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Klink R, Bowler DE, Gongalsky KB, et al. (2020) Meta-analysis reveals declines in terrestrial but increases in freshwater insect abundances. Science 368:417–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Noordwijk M, Cerri C, Woomer PL, et al. (1997) Soil carbon dynamics in the humid tropical forest zone. Geoderma 79:187–225. [Google Scholar]

- Vanlauwe B, Descheemaeker K, Giller KE, et al. (2015) Integrated soil fertility management in sub-Saharan Africa: unravelling local adaptation. Soil 1:491–508. [Google Scholar]

- Vanlauwe B, Wendt J, Giller KE, et al. (2014) A fourth principle is required to define Conservation Agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa: the appropriate use of fertilizer to enhance crop productivity. Field Crops Research 155:10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Vollset SE, Goren E, Yuan C-W, et al. (2020) Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet 396:1285–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts CW, Dexter AR. (1997) The influence of organic matter in reducing the destabilization of soil by simulated tillage. Soil and Tillage Research 42:253–275. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte W. (1987) Our American Land: 1987 Yearbook of Agriculture. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Zhu B, Wang S, et al. (2017) Stimulation of N2O emission by manure application to agricultural soils may largely offset carbon benefits: a global meta-analysis. Global Change Biology 23:4068–4083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]